Abstract

This article explores the status and role of Venus within the Italia: Open to meraviglia campaign, with a focus on a dataset of visual texts extracted from the venereitalia23 Instagram profile over the initial year of its publication. The adopted integrated framework encompasses the grammar of visual design by Kress and van Leeuwen, the interdiscursivity model developed by Bhatia and a scale for measuring sexism in tourism representations by Pritchard. The questions that guide the research are the following: How is venereitalia23 visually represented across the Instagram profile? How do art and gender discourses intersect with one another within the campaign? Italia: Open to meraviglia employs an originally aesthetic icon by Sandro Botticelli. The creative solution may be seen as paying a tribute to Italian heritage. Similarly, the choice, coding and use of Venus as the ambassador and influencer may be read as challenging stereotyped gender representation in tourism discourse. However, the results show that the graphic configuration venereitalia23 achieves in the virtual dimension (through gestures, actions, clothing, gaze, size of frame, information value) makes it resemble a doll-influencer. Ultimately, the campaign fails in both celebrating the artistic heritage and emancipating the female role, as both are exploited and objectified.

1 Introduction

This article presents a socio-semiotic analysis of Venus within the Italia: Open to meraviglia tourism marketing campaign through the lens of the grammar of visual design, and with a focus on the interdiscursivity process between art, gender, and tourism discourses. Launched by ENIT (the Italian national tourism board) in the post-pandemic international tourist market of 2023, the institutional project targeted international airports and railway hubs and had a cost of 9-million euros. Developed by the acclaimed Turin-based Armando Testa Group, the campaign used Venus as its female ambassador and virtual influencer and the claim: “Italia: Open to meraviglia” (open to wonder).

The launch on April 30th 2023 was followed by an unusual media response (Koprivica Lelićanin 2024: 203; Bassi, Polezzi, and Riccò 2023: 281). Social networks, TV programmes, magazine pages were flooded with critical comments on the poor quality of tourist material, on the superficial marketing strategies and on procedural oversights. The use of low-resolution images and of Shutterstock photos was systematically mocked, epitomized by a screenshot showing a Slovenian wine cellar (and a bottle of the Slovenian Cotar wine on the table) being used in a video promoting the Italian heritage (Bassi, Polezzi, and Riccò 2023). The German version of the campaign website became very popular, due to the literal mistranslation of place names like Rasen (meadow) for Prato or Garderobe (wardrobe) for Camerino. It is also worth noting that the opentomeraviglia.it domain was not registered, but bought by a marketing agency for 4.99 euros. Similarly, the venereitalia23 official handle was not registered on Twitter. This media attention was, paradoxically, appreciated by the Armando Testa Group: a public letter sent to the newspapers expressed satisfaction at the popularity of the campaign (Koprivica Lelićanin 2024: 103–104).

However, what attracted impressive attention, received mixed feedback, and generated an unprecedented number of memes, is Venus, or, rather, venereitalia23. The launch of the campaign was accompanied by a video on the Italian Ministry of Tourism’s website (2024), with an enthusiastic male voice-over explaining:

avevamo bisogno di un[a] testimonial all’altezza, qualcuno di molto moderno ma con una grande storia alle spalle. Magari una virtual influencer contemporanea, ma […] anche un’icona dell’Italia nel mondo, riconoscibile da tutti attraverso un semplice sguardo e il segno inconfondibile dei suoi capelli.[1]

Instead of a real ambassador, the campaign uses a virtual image of Sandro Botticelli’s Venus. Throughout the campaign materials, the ‘contemporary virtual influencer’ visits unmissable attractions, tastes traditional food, takes selfies and rides on cycle paths. The choice of Venus is of interest for a number of reasons, in addition to the visibility and reputation mentioned by the institutional video. From a symbolic point of view, Venus coming from water embodies individual and social rebirth in the post-pandemic era. On a discursive level, this form of contact between Botticelli’s Venus and the tourist domain seems innovative. From a marketing point of view, the choice of Venus as ambassador and virtual influencer is attention-grabbing, and the sole female ambassador is of interest from the standpoint of gender studies.

In this article, attention will be devoted to a dataset of visual texts extracted from the venereitalia23 Instagram profile over the initial year of its publication (20.04.2023–20.04.2024). The exploration of the choice, coding and use of Venus as the female ambassador and influencer within the Italia: Open to meraviglia campaign relies on an integrated framework. It encompasses the grammar of visual design by Kress and van Leeuwen (2021), the interdiscursivity model developed by Bhatia (2004, 2006, 2017) and a scale for measuring sexism in tourism representations by Pritchard (2001). The questions that guide the research are the following: How is venereitalia23 visually represented across the Instagram profile? How do art and gender discourses intersect with one another within the tourism campaign?

Results show that the choice, coding and use of Venus only apparently question and challenge stereotyped modes and forms of gender representation in tourism discourse. Across the posts, Venus is clearly given salience and priority through her pervasiveness, size, framing and compositional dynamics, which appear to align with her status and role within the campaign. However, her posture, gestures and the predominantly conceptual representational structures deprive venereitalia23 of agency and confirm her as the object of the tourist perception. Similarly, the campaign does not pay a tribute to Botticelli’s work. The formal bending visible in the adaptation of gestures, actions, gaze, size of frame, information value, is entwined with a functional bending, whereby an aesthetic discourse is exploited and manipulated with an ideological repurposing. This article argues that even the tourism promotion effect is weak: the campaign is ultimately unsuccessful in celebrating the Italian natural and cultural heritage. If venereitalia23 seems to experience the Italian lifestyle and heritage she is promoting, she is actually objectifying the Italian heritage she generally covers, hides and neglects. While objectifying both art and women, she is offering that object to the tourist perception, for tourist consumption.

The paper is organised as follows: Section 1 provides an introduction to the ENIT campaign, while Section 2 reviews previous literature on institutional tourism discourse. Section 3 outlines the analysed materials, namely the dataset of visual texts retrieved from the venereitalia23 Instagram profile. If Section 4 illustrates the employed methodology, Section 5 presents the results and Section 6 discusses the choice, coding and use of Venus as the female ambassador and influencer within the campaign. Section 7 draws some concluding remarks.

2 Literature review

If magazines, social media, radio and TV programmes have been disseminated with opinions, references, memes related to the ENIT 2023 campaign, limited critical attention in scientific publications can be observed. Exceptions are Bassi, Polezzi, and Riccò (2023), who specifically addressed the campaign video through the lens of the transnational paradigm and Koprivica Lelićanin (2024), who explored 3,401 audience comments on the most popular posts of the venereitalia23 Instagram profile. To the best of my knowledge, no scholarly publications exist on the Instagram profile posts themselves, and this work aims to address that gap.

Drawing on previous pilot work (Francesconi 2024) on the institutional campaign Italia: Open to meraviglia, originally written in Italian, the present article expands the dataset, redesigns the methodological framework, and hones the critical discussion. It benefits from research on tourism discourse that has been conducted over the last three decades, starting from the seminal study by Graham Dann (Dann 1996). Subsequent research in the field has addressed a range of contexts, examining the production, negotiation, and dissemination of tourism discourse in diverse and distinct situations. These include institutional, editorial, informal contexts, and consider the discourse of public and private stakeholders in the tourism industry, as well as that of tourists and tourees.

The present work examines the institutional situation, where official bodies communicate with the public. This vertical discourse entwines dynamics of power and hegemony (Cappelli 2023; Denti and Fodde 2017; Maci 2020). Critical studies of official tourism discourse address a wide range of text genres, including, without being limited to, brochures (e.g., Francesconi 2011; Hiippala 2015), or websites (e.g., Hallett and Kaplan-Weigner 2010; Maci 2020; Malamatidou 2024; Manca 2016). In addition to traditional formats, more innovative digital genres are being critically explored, including digital videos (e.g., De Marco 2017), digital video diaries (Francesconi 2018), Instagram (e.g., Mattei 2024) or Facebook profiles (e.g., Kumar et al. 2021). The focus of these works is the destination branding process of a number of sites, such as Italy (e.g., Manca 2016), Finland (e.g., Hiippala 2015), Australia (e.g., Manca 2016), India (e.g., Kumar et al. 2021), Malta (e.g., Francesconi 2011), the UK (e.g., Maci 2020; Manca 2016), and New Zealand (e.g., De Marco 2017). The linguistic, textual and discursive phenomena addressed in institutional tourism discourse include, among others, multimodal meaning-making (e.g., Hiippala 2015), multimodal hypertextuality (Francesconi 2014), genre integrity and innovation (e.g., De Marco 2017), cross-cultural communication (e.g., Manca 2016), translation (e.g., Malamatidou 2024), linguistic contact (e.g., Cappelli 2023), metaphorical patterns (Denti and Fodde 2017) and destination image performance (e.g., Maci 2020).

3 Materials

This article devotes particular attention to a dataset of visual texts retrieved from the venereitalia23 Instagram profile during its first year of publication (20.04.2023–20.04.2024). The choice of Instagram, among other social networks, is due to its relevance in tourism discourse, in shaping and perpetuating ‘the tourist gaze’ (Cilkin and Cizel 2022; Urry 2002). By this, Urry describes the perceptual model that tourists adopt while on holiday, acting as a lens that (de)codifies new images by working with carefully planned visual filters. Widely used by holidaymakers to provide and display visual evidence of their holidays, Instagram is also being adopted by private and public tourism stakeholders with promotional aims, as a tool for destination image-making (Mattei 2024; Smith 2021).

On their Instagram accounts, private or public users can freely upload static and dynamic images and add verbal texts. Such content can be commented on, appreciated or shared by followers, who, through their engagement, increase the visibility and circulation of the materials (Arsenyan and Mirowska 2021; Zappavigna 2016). Institutional boards such as ENIT exploit not only the affordances of the platform in terms of potentially limitless and instantaneous reach, but also the horizontal and co-participatory dimension of the 2.0 communication.

Although the Italia: Open to meraviglia campaign and the venereitalia23 Instagram profile employ a range of multimodal resources (Francesconi 2014; Hiippala 2015) to make meaning (i.e., the verbal claim in the overall campaign and the verbal comments made by the followers in the Instagram profile), this article focuses on the visual semiotic resource for a number of reasons. Firstly, due to the predominantly visual component of the tourist semiosis (Cilkin and Cizel 2022; Robinson and Picard 2016; Urry 2002). Secondly, because the Instagram network is mainly based on visual content and on visual semiosis (Arsenyan and Mirowska 2021; Mattei 2024; Zappavigna 2016). Thirdly, since venereitalia23 icon represents arguably the most innovative strategy adopted by the campaign. Fourthly, because of the impact of Venus’ visual codification (Koprivica Lelićanin 2024).

As aforementioned, the campaign relies on a virtual representation of Sandro Botticelli’s image of Venus. Painted in 1,485 for the Castello Medici villa and displayed at the Firenze Galleria degli Uffizi, the painting by the Renaissance artist Sandro Botticelli is entitled Nascita di Venere, which translates as Venus’ birth. The Goddess is naked, at the center of the composition, standing on a shell in the sea. Her right arm covers her breasts, while her left hand and her hair cover her pubis. In her posture, gesture and gaze the protagonist evokes the traditional iconographic model of Venus pudica (Elan and Debenedetti 2019; Poletti 2007). On her right is Zephyrus, the god of winds, carrying the gentle breeze Aura. On her left is one of the Horae, the goddesses of the Seasons, who awaits Venus with a flower-covered robe. An emblem of ideal and spiritual beauty, Venus conveys values of purity, simplicity and harmony: her traits are elegant and delicate, her hair is floating in the breeze, her gaze is serene but melancholic.

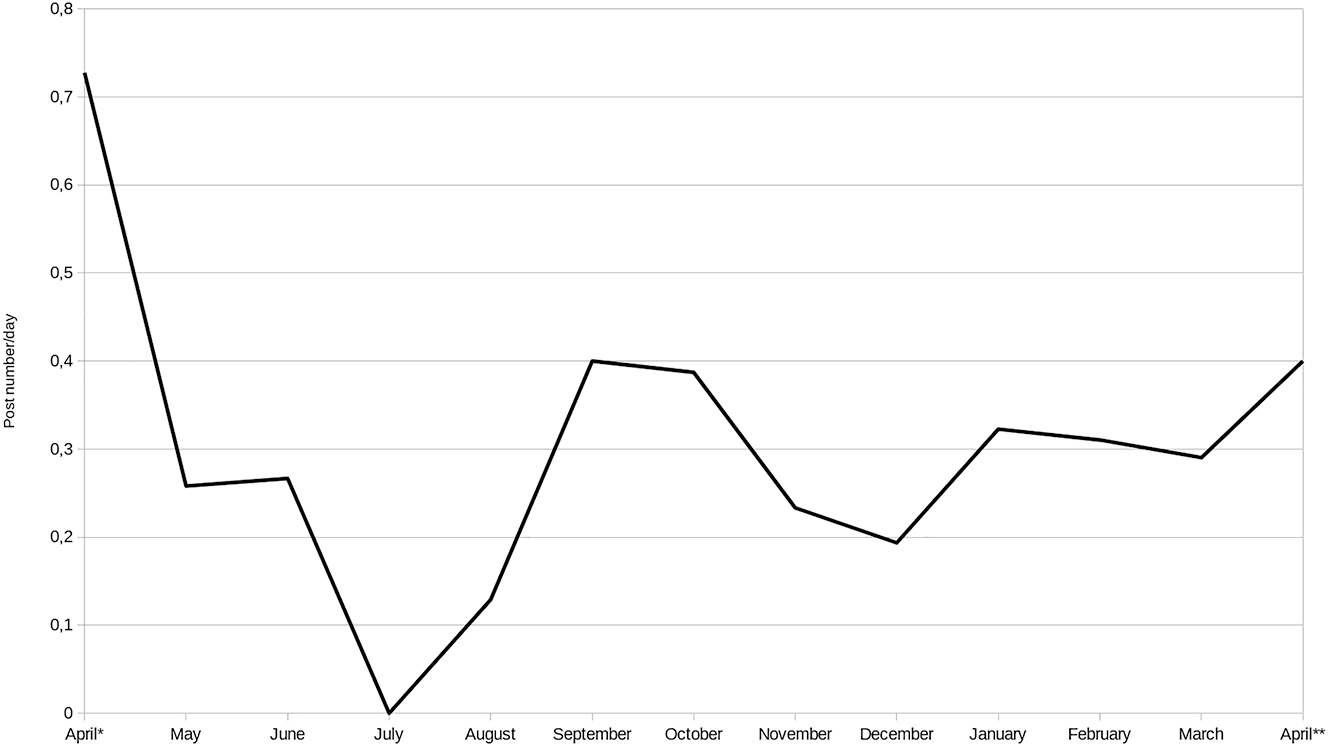

Before focusing on the visual analysis, the context of the venereitalia23 Instagram profile needs to be illustrated. In the initial year of the venereitalia23 Instagram profile, a total of 103 posts were published. In addition to the relatively low number of occurrences, the posts show lack of consistency in terms of frequency, content, style and composition. The number of posts published per month varies considerably: eight posts in the ten days in April, eight in May, eight in June, four in August, twelve in September, twelve in October, seven in November, six in December, ten in January, nine in February, nine in March, eight in the first 20 days of April, with a break in-between June 28th and August 28th, coinciding with the summer season peak. Figure 1 illustrates post publication across the twelve months. The irregularity in publication frequency and the extended summer break have been noticed and denounced by journalists and by the profile followers alike (Koprivica Lelićanin 2024).

Frequency in the venereitalia23 instagram profile.

The profile aims to promote the main tourist destinations, including art cities like Florence, Venice, Rome, or seaside resorts, such as Taormina, Lerici and Vietri. In the video used to open the Instagram profile on April 20th, Venus announces: “vi porterò in giro per l’Italia per mostrarvi i suoi luoghi meravigliosi e le sue eccellenze. Vi racconterò di bellezza, cultura, cucina, ospitalità, musica, e arte, ovviamente.”[2] The following paragraphs will check whether these themes are covered across the posts, whether post content is in line with the campaign aim and whether post content is consistently covered across the posts.

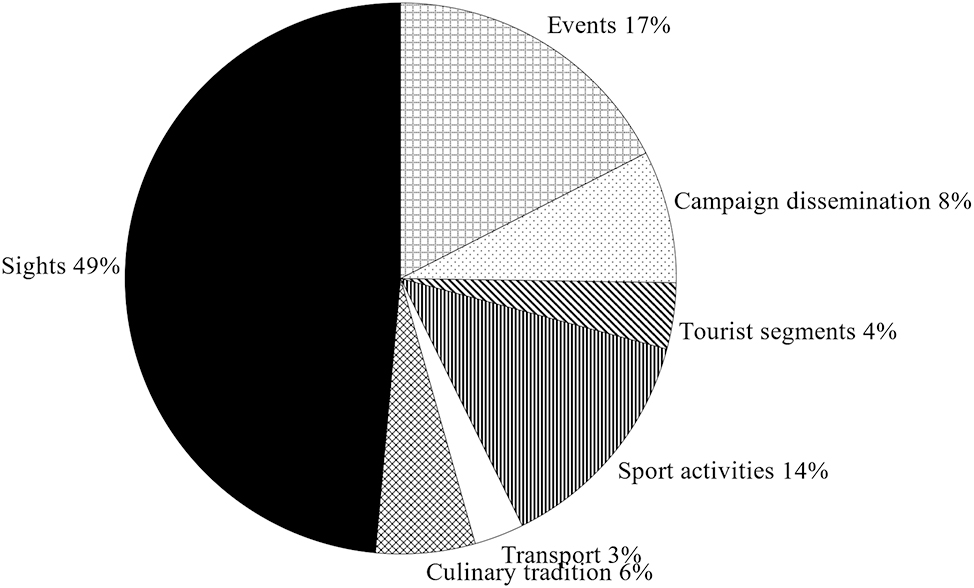

In terms of content selection and distribution, some contributions promote, generally and vaguely, tourism segments, related to spas, cultural heritage, or mountains (4 %), while others celebrate means of transport (3 %). If only a limited number of posts describe the Italian culinary tradition (6 %), more attention is paid to sporting activities and events (14 %), such as the Italian cycling tour, the European volley, the Rome golf cup. A similar number of entries focus on events, celebrations, occasions (17 %), like Women’s day, Valentine’s day, the Carnival. While such cases may be of interest to potential international visitors, others are less clear in their target and purposes. Several posts (8 %), indeed, deal with the campaign itself, showing how it is disseminated at international tourism fairs (e.g., in London, Berlin, Lisbon and New York) and through icons or gadgets. Unsurprisingly, the majority of posts promote sights to be visited while on holiday (49 %).

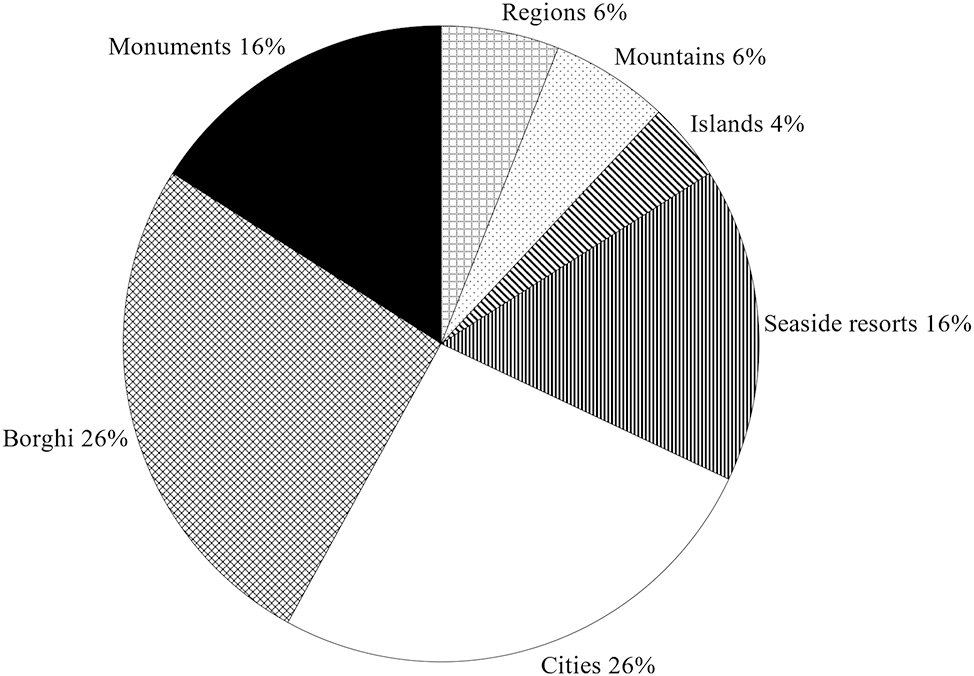

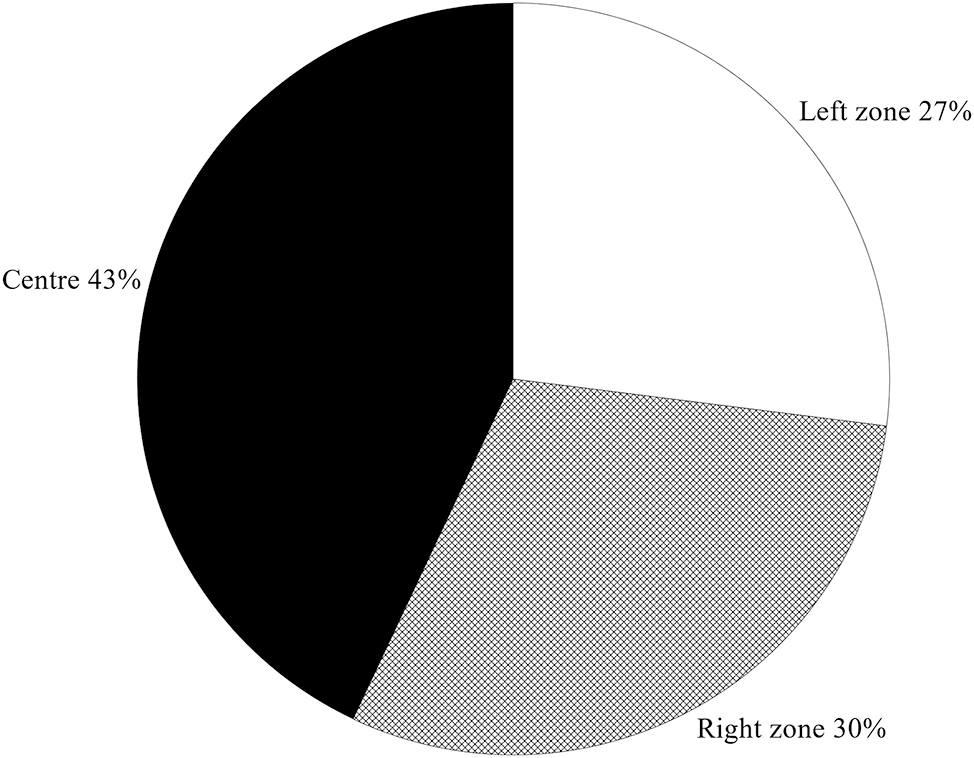

A closer look at the specific sub-field of sights reveals that some contributions are devoted to Italian regions (6 %). However, out of twenty Italian regions, only Emilia Romagna, Marche and Basilicata are mentioned. A higher number of texts refer to seaside resorts (16 %); a significant number to art cities (26 %) and traditional villages, called borghi (26 %). More specifically, 16 % of the instances celebrate Italian monuments, such as Sismondo Castle, La Fenice Theatre, and Apulian churches. Only 4 % of sight-specific posts celebrate Italian islands and only 6 % represent Italian mountains. In summary, the following figures illustrate topic distribution across the profile. While Figure 2 addresses general corpus content, Figure 3 shows further segmentation of the attraction-devoted posts.

Content in the venereitalia23 Instagram profile.

Sight categories in the venereitalia23 Instagram profile.

The content analysis reveals a weak consistency between topic, aim, and target of the Instagram profile. While categories like food are underrepresented in relation to the Italian identity, others, like campaign dissemination, are not functional to the promotion of the Italian heritage and lifestyle to prospective tourists.

Similarly, the style is not graphically homogeneous across the profile, with a post displaying a monochromatic image, another showing an abstract image, others evoking postcard-like pictures and still others featuring a slideshow or a video. In terms of composition, each post comprises static or dynamic images ranging from one to ten items, accompanied by a written text in both Italian and in English and several hashtags. Regardless of the subject matter, length, or structure, venereitalia23 is generally on the first image. This article addresses only the first image depicting Venus, thus excluding video-based posts.

4 Methods

The investigation of venereitalia23 within the dataset relies on an integrated methodological framework. It considers the interdiscursivity model developed by Bhatia (2004, 2006, 2017), the grammar of visual design by Kress and van Leeuwen (2021), and a scale for measuring sexism in tourism representations by Pritchard (2001). The integration of the three models responds to the fact that the phenomenon of interdiscursivity is visually configured through specific parameters of the grammar of visual design, thereby generating a gendered representation of venereitalia23.

The most innovative strategy adopted by the campaign seems to be the discursive hybridity between Botticelli’s heritage the artistic and tourist domains, whereby an official tourist campaign relies on an art icon. In order to explore this phenomenon, the interdiscursivity model developed by Bhatia (2004: 89; 2017) has been deemed an appropriate framework. Bhatia identifies three main forms of hybridity among domains (a process which he terms interdiscursivity): ‘mixing’, ‘embedding’ and ‘bending’. Mixing entails the combination of two genres in a way that makes them undistinguishable in the final text, like in the case of an advertorial, or an infomercial (Bhatia 2004: 89). Embedding occurs when a text is integrated within another one, resulting in a text with a different function. An example is a magazine article incorporated within a textbook or an urban map included on a gift bag. Bending implies the adaptation of a genre, through phenomena including conversationalisation, marketization or technicalization of the adopted language. Bhatia (2006: 17) provides the example of corporate disclosure documents (e.g. corporate annual reports) which, over time, have shifted from a mere informative function to one that is promotional in nature.

Since interdiscursivity in the profile is visually configured, Kress and van Leeuwen’s toolkit for the analysis of visual texts and their meaning-making is a valuable resource (2021). A range of selected parameters from their framework will be used in this article: represented participants, representational structures, contact, size of frame and information value. Represented participants are the people, places and things depicted in an image (Kress and van Leeuwen 2021: 45). Representational structures indicate the way participants are organized and may be narrative, if they display the unfolding of actions or events, or conceptual, if they represent stable class, structure or meaning (Kress and van Leeuwen 2021: 55). Contact refers to whether human participants either look directly at the viewer (i.e. enacting a function of demand) or not (i.e. enacting a function of offer) (Kress and van Leeuwen 2021: 116). Size of frame is defined in relation to specific sections of the human body: in close-ups only the head and the subject’s shoulders are depicted, in medium shots the subject is cut off at the knees, and in long shots the figure is fully represented. As a consequence of size of frame, different social relations between the gazer and the gazee can be distinguished, ranging from intimacy to distance (Kress and van Leeuwen 2021: 123). Information value implies the meaningful location of elements: on the left side already given information, on the right side a new message, at the centre the most significant and salient part and at the margins the subservient and ancillary information (Kress and van Leeuwen 2021: 181).

The visual configuration of interdiscursivity in the dataset gives rise to a gendered image of Venus. This scenario reflects a more pervasive phenomenon. “Since tourism is a product of gendered societies”, as Prichard asserts (2001: 91), “tourism processes are gendered in their construction, presentation and consumption”. In Pritchard’s model for addressing gendered tourism imagery (2001: 91), representation encompasses four levels: Level I images depict women as a one dimensional sexual object or decoration; Level II images show women in traditional role, either passive or engaged in childcare); Level III images portray active women in non-traditional roles and activities, such as sports practice; Level IV images depict women as individuals. Pritchard’s frame addresses both female and male participants, explores brochures and considers different forms of holiday (short and long-haul holidays for seniors, singles, couples). The focus of this paper is on the representation of women in the Instagram profile and with no distinction between holiday forms.

This research is guided by the following research questions: How is venereitalia23 visually represented across the Instagram profile? How do art and gender discourses intersect with tourism campaign?

5 Results

The visual analysis of venereitalia23 across the Instagram profile needs to acknowledge the relationship between continuity and discontinuity established with the original Venus by Botticelli.

Across the posts, venereitalia23 maintains the face, as well as the unmistakably melancholic expression. Her long, wavy blonde hair flowing in the soft wind is faithfully preserved. The hair bond is identical, but has the colours of the Italian flag: green, white and red. The body is slimmer and is clothed in “a rotating collection of trendy outfits” (Bassi et al. 2023: 282). Indeed, clothing keeps changing across the posts, being appropriate for the different occasions Venus is involved in. When she practices sport, for example, she wears the suitable uniform for each specific activity. It seems that the clothing items are the campaign aspect that has been given most attention within the profile. However, following an initial period of creativity, variety, attention and innovation, many cases of clothes recycling were observed in subsequent posts (e.g., on October 26th and December 14th venereitalia23 wears the same blue dress in Genova and Lerici).

In contrast to Botticelli’s Venus pudica in a state of arrested movement and with her hands covering her naked body (Elan and Debenedetti 2019; Poletti 2007), posture and gestures are diverse in the Instagram profile. Across the Italian regions, cities, towns, she may be situated on the floor or on a rock, or she may be standing and leaning against a wall, a column, a wall. With her hands, she may be pointing, mimicking a heart, expressing sympathy with both hands on her heart. In general, she appears to be engaged in some sort of physical activity. Very frequently, she is captured in posts promoting sporting activities, as mentioned before. Actually, she is never practicing sports, but posing, in a static posture, with the perfect clothes and equipment. The only activity she is actually engaged in is the taking of selfies (Zappavigna 2016: 278): sometimes, the smartphone and hand are outside the frame and the image is distorted due to the close focal range (e.g., during international tourism fairs); sometimes, the whole body and the smartphone-holding hand are visible, the image being about the taking of a selfie (e.g., in Venice or in Sirmione). In a post devoted to the Marche region, venereitalia23 is posing with a camera in her hands. The static image is not representing the unfolding of a picture-taking action, and the whole camera-holding figure becomes a timeless, decorative object to be admired. Similarly, in the majority of images (86 %), Venere is the object of the tourist gaze, waiting to be captured and fixed by the camera. If the representational structures (Kress and van Leeuwen 2021: Chapters 2, 3) in the dataset seem to be narrative, they ultimately tend to be conceptual. This predominant conceptualization phenomenon leads to objectification. If Venere seems to experience the Italian lifestyle and heritage she is promoting, she is actually objectifying the Italian heritage she represents. Hence, she is offering that object to the tourist gaze, for tourist consumption.

Unlike Botticelli’s Venus, who avoids eye-contact with the viewer (Elan and Debenedetti 2019; Poletti 2007), venereitalia23 establishes a direct contact with the audience. Corresponding to the ‘you’ verbal pronoun within the linguistic system (Biber, Leech, and Johansson 1999: 330–331), the direct gaze encodes a form of direct engagement. This formal change in the visual configuration is in line with the social network environment and with the promotional function. Accordingly, venereitalia23 first visually involves the audience through eye-contact, then she calls for action (i.e., choosing Italy as a holiday destination). This engagement is in line with the “coquettish” tone (Bassi, Polezzi, and Riccò 2023: 281) that venereitalia23 adopts in her speech, in the video used to open the Instagram profile on April 20th:

Ciao a tutti, il mio nome è Venere, ma probabilmente questo lo sapete già. Ho 30 anni. Ok, qualcosina di più a dire il vero. E sono una virtual influencer. Che significa? Beh, vi porterò in giro per l’Italia per mostrarvi i suoi luoghi meravigliosi e le sue eccellenze. […] Proprio come i vostri influencer preferiti. Io non vedo l’ora, e voi? Seguitemi, sarà un viaggio entusiasmante. Promesso![3]

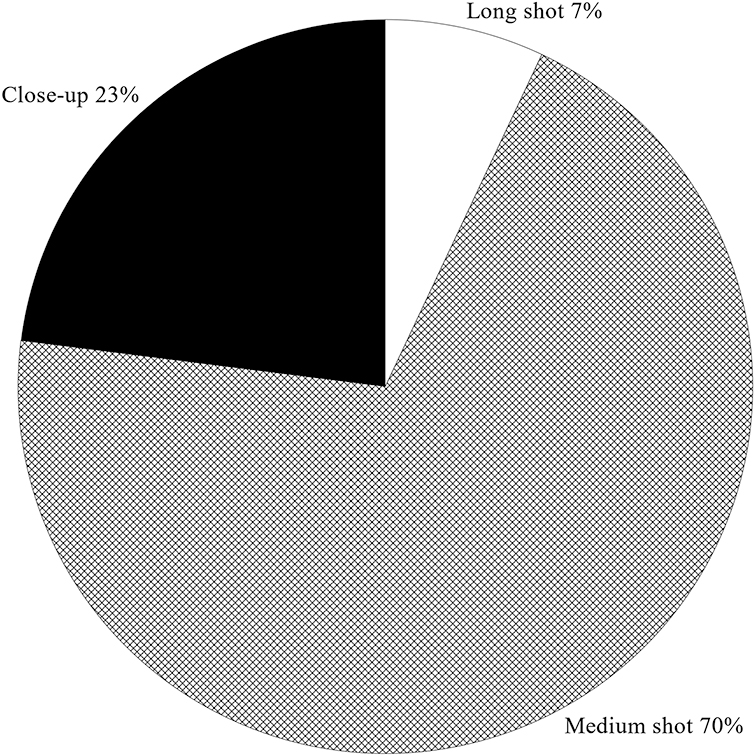

Engagement is enacted through other semiotic systems. If the original Venus is represented in full length, in a long shot, the predominant size of frame technique in the dataset is the medium shot (70 %), in which the body is cut off at the knees. This is followed by the close-up technique (23 %), where only the head and shoulders are visible. A limited number of visuals depict the full body (7 %), following the iconographic model (Figure 4). The adaptation of the system of size of frame reduces social distance between the virtual influencer and the users. In line with the semiotic system of gaze contact and with the promotional engagement strategy, this solution establishes a familiar relation with the users, and overcomes the interpersonal distance established in the Renaissance artwork.

Size of frame in the venereitalia23 Instagram profile.

Information value in the venereitalia23 instagram profile.

In terms of framing, in continuity with Botticelli’s painting, Venus is positioned predominantly at the centre of the visual composition (43 %), literally obscuring the sights she is supposed to depict. The effect of covering is further enhanced by the size of her body. A considerable number of posts (30 %) show her body in the right zone of the visual composition, which serves as the focal point. In this configuration, her body size is limited, but her position is still salient and grabs the viewer’s attention, according to the grammar of visual design. In a certain number of posts (27 %), Venus occupies the left side of the visual space, indirectly and appropriately guiding the viewing trajectory towards the right zone, where the destination is visible. However, in this latest compositional typology, the figure of Venus achieves salience though size, thereby capturing the viewer’s attention. Therefore, it can be concluded that size of frame and composition are not functional to the promotion of the Italian cultural heritage, which is, instead, covered, backgrounded, or marginalised. Instead, the effect appears to be the foregrounding and celebration of Venus herself. Is this emphasizing strategy a tribute to Botticelli’s work? Is this solution functional to providing agency to the female human participant? These two questions will be asked in the next section. Figure 5 illustrates the information value of the dataset.

6 Discussion

The previous section has addressed how the tourist marketing campaign Italia: Open to Meraviglia relies on a virtual representation of Sandro Botticelli’s Venus. Given the pivotal role that the cultural heritage plays for Italy, this form of contact between Botticelli’s Venus and the tourist domain in the whole project and, specifically, within the venereitalia23 profile is arguably convincing. In order to establish the connection, it would appear that the campaign enacts a form of embedding, whereby the artistic icon is appropriated by the tourism domain. Such solution is also of interest, insofar as it exploits Venus’ visibility and reputation. However, the results demonstrate that the appropriation of Venus is not conducted as a neutral form of tribute to the original. The formal bending evident in the adaptation of gestures, actions, gaze, size of frame, information value, is entwined with a functional bending, whereby the aesthetic discourse is exploited and manipulated with an ideological repurposing. Far from being celebrated, art undergoes a process of commodification.

The discursive hybridity between Botticelli’s work and the tourism domain finds a correlative in the linguistic hybridity of the claim Italia: Open to Meraviglia (Bassi et al. 2023: 282). In theory, the strategy may be perceived as convincing, given the pervasiveness of linguistic contact and code switching among young people, apparently the campaign target. Another argument in favour of this position is that it is coherent with the intercultural and interlinguistic nature of the tourism phenomenon (Dann 1996). The ‘languaging’ technique (1996: 183) had indeed been adopted by previous official campaigns, such as the ‘Very bello’ campaign run by the Cultural Heritage Ministry for the 2015 Milano Expo. However, the claim Italia: Open to Meraviglia has been the subject of criticism, with the term ‘open’ being deemed vague (is Italia open or should visitors be open?). Additionally, the term ‘meraviglia’ has been criticized for its complex phonetic structure and morphological extension.

A further aspect of hybridity in the campaign is the role of the virtual influencer assigned to Venus. As previously stated, the strategy appears to be innovative, given the pervasiveness of influencers and of influencer marketing in contemporary society and among young people (Yesiloglu and Joyce 2021). The persuasive potential of social media influencers is shaped by a range of factors, such as personal attributes, attitude homophily, physical attractiveness, and social attractiveness, as well as characterization elements, e.g., trustworthiness, perceived expertise and pseudo-social relationships (Masuda et al. 2022: 4). The latter refers to the fact that followers develop feelings of intimacy toward media personalities after repeated exposure (Masuda et al. 2022). In contrast to the more traditional role of the social media influencer, the virtual one is not physically but virtually embodied in the campaign, as a computer-generated imagery, created by digital artists (Arsenyan and Mirowska 2021). The virtual dimension provides a more stable and reliable stance, allowing the influencer to be deprived of the “downsides of real life or personal flaws” (Arsenyan and Mirowska 2021).

Nevertheless, Arsenyan and Mirowska (2021: 13) argue that the virtual influencer operates within the realm of fake authenticity, given their overt virtual nature. In the ENIT campaign, the concept of fake authenticity is further enhanced by the fact that Venus is situated at the center of a complex network of plural, entangled, and mutually contradictory references. Originally an aesthetic image, Venus has been “modelled on a Barbie doll” that “resembles Italy’s most famous influencer Chiara Ferragni” (Bassi et al. 2023: 281). The potentially valid process of becoming virtual implies the shaping of a confused and confusing image that intertwines elements of cosmetics, marketing and objectification and fails to realise its promotional function. In their comprehensive literature review on the subject, Arsenyan and Mirowska (2021) observe mixes and contradictory conclusions as to how users “react socially, emotionally, cognitively, and behaviourally to virtual agents” in relation to how “they do to other humans”. Across the posts, venereitalia23 constantly engages with her followers through verbal and visual strategies (Koprivica Lelićanin 2024). It appears that the followers use pervasive irony in their comments, with a twofold target. On the one hand, they ridicule the ontological traits of her virtual dimension, pretending to embody Italian heritage, while in fact staging a doll-influencer. On the other hand, they mock the “cheap aesthetics” (Bassi, Polezzi, and Riccò 2023: 282), as well as the inaccuracies of the campaign (being campaign feedback beyond the scope of this paper, see Koprivica Lelićanin 2024 on this subject matter).

Thus, the contradictions and limits identified in the ENIT campaign on the discursive, linguistic and marketing levels can be also envisaged from a gender perspective, in form and content. Once more, the initial idea is convincing: a single woman is given agency as local guide. In contrast to conventional tourism marketing, Venus is not apparently at the service of tourists, to be consumed as part of the tourist product (Cappelli 2023). She is neither used as a pleasant background, asked to provide local colour to the campaign. In the posts, Venere independently lives the Italian environmental and cultural heritage, thereby challenging the traditional tourists versus non-tourists dichotomy in tourist materials. She is not subject to the power dynamics which are typical of tourist exchanges, generally regulated by patriarchal and colonial forms of exploitation (Banaszkiewicz 2014; Pritchard and Morgan 2000; Sirakaya and Sonmez 2000). Furthermore, she is not depicted in the company of men, within a socially accepted and marketable patriarchal image (Pritchard 2001: 88). If we adopt Pritchard’s scale for measuring sexism in tourism representations, we may consider the Venere posts as representing gendered tourism imagery. On initial observation, the profile aims at promoting Level III images portraying women in non-traditional roles, with Venus travelling alone, being engaged in sporting activities and representing and promoting Italy. This is in line with what was announced in the video launch, in which Venus was defined as the female ambassador and influencer.

However, the data indicate that only rarely is Venus the author of the pictures, while she is generally the object. In the first case (e.g., at international tourism fairs), Venus shows herself while she is taking the photograph, having selected and positioned the frame. In the second case (e.g., in sport-related posts), Venus is the subject of an image captured by another individual, which adheres to a more traditional and conventional tourism imagery. Although the subject appears to be engaged in some athletic activity, her posture is static and her movement constrained, suggesting a lack of agency. In most images the female represented participant is offering her image to the tourist gaze, simply posing in front of the camera and perpetuating her image as a one-dimensional sexual object or decoration of Level I. This is consistent with the definition provided by Bassi, Polezzi, and Riccò (2023: 281) of venereitalia23 as a “blonde, coquettish digitalization of Botticelli’s idealized female body”. In conclusion, the campaign can be seen to align with the traditional tourism sexism discourse based on “the use of women as sexualized product adornments” (Pritchard 2001: 79). The findings corroborate Pritchard’s assertion (2001: 86) that, in tourist imagery, “non-traditional images for (…) women do not extend to a reversal of submissive and authoritative roles.” The results show that the choice, coding and use of Venus as a female ambassador and influencer within the campaign only apparently question and challenge traditional modes and forms of gender representation in tourism discourse. The deployment of strategies that may provide agency serves, ultimately, to confirm venereitalia23 as the object of the tourist gaze. The agency is only ascribed to Venus in order to depict her as the agent of her own objectification: she is not the victim but the perpetrator of the patriarchal/tourist gaze.

In her 2001 article, Pritchard noticed “[w]hereas ten years ago, tourism marketers routinely posed a bikini-clad young woman by swimming pools, now they may also photograph an athletic, swimsuited young woman posing on water-skis – but her sexual attractiveness remains paramount” (Pritchard 2001: 91). After more than two decades, gendered representation strategies appear to remain at a similar point. The stylistic fact that Venus is not naked seems to be motivated by the need to celebrate Italian fashion, on the one hand, and to protect the campaign from criticism of political incorrectness on the other hand, also in relation to its international and intercultural reach. The only change that has occurred meanwhile is that the female subject being represented is aesthetic in its origin (i.e., the appropriation of Botticelli’s figure) and virtual in its representation (i.e., the use of a virtual influencer). However, the aesthetic/virtual image is manipulated to resemble a doll-influencer. The campaign, ultimately, fails to celebrate the artistic heritage or to emancipate the female role, as both the artistic heritage and the female body are exploited and objectified.

7 Conclusions

This article has presented a socio-semiotic analysis of Venus within the Italia: Open to meraviglia tourism marketing campaign, focusing on a dataset of 103 visual texts retrieved from the venereitalia23 Instagram profile across the first year of its publication. For the inspection of the status and role of Venus, an integrated framework has been adopted, drawing on tools from the grammar of visual design by Kress and van Leeuwen, the interdiscursivity model developed by Bhatia, and the scale for measuring sexism in tourism representations by Pritchard.

The results demonstrate that the choice, coding and use of Venus as the female ambassador and influencer within the campaign only apparently question and challenge conventional modes and forms of gender representation in tourism discourse. Across the posts, Venus is clearly given salience and priority through pervasiveness, size, framing and compositional dynamics that seem consistent with her status and role within the campaign. However, her posture, gestures and the predominantly conceptual representational structures deprive venereitalia23 of agency and confirm her image as the object of the tourist/patriarchal gaze.

In the same vein, the campaign does not pay a tribute to Botticelli’s work. The formal bending evident in the adaptation of gestures, actions, gaze, size of frame, information value, is entwined with a functional bending, whereby an aesthetic discourse is exploited and manipulated with an ideological repurposing. If venereitalia23 seems to experience the Italian lifestyle and heritage she is promoting, she is actually objectifying the Italian heritage she represents. She is offering that object to the tourist gaze, for tourist consumption. While objectifying both art and women, she covers, hides and neglects Italy across the posts. Ultimately, the Italia: Open to meraviglia campaign fails in celebrating the Italian natural and cultural heritage as well.

The limitations of the conclusions are clear and primarily related to the research design. Firstly, the research has focused on a single social network, thereby excluding other platforms and other genres the campaign encompasses. Secondly, a limited time-span of one year has been considered for the inspection of the profile. Thirdly, primary attention has been given to the visual mode, leaving to the verbal one an ancillary role: written posts have only been considered to offer a panoramic view. These three aforementioned lines of enquiry will be the scope of future research.

References

Arsenyan, Jbid & Agata Mirowska. 2021. Almost human? A comparative case study on the social media presence of virtual influencers. International Journal of Human-Computer Studies 155. 102694. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhcs.2021.102694.Suche in Google Scholar

Banaszkiewicz, Magdalena. 2014. Images of women in tourist catalogues in semiotic perspective. Turystyka Kulturowa 2. 55–69.Suche in Google Scholar

Bassi, Serena, Lorena Polezzi & Giulia Riccò. 2023. Introduction: Critical issues in transnational Italian studies. Forum Italicum 57(2). 273–288. https://doi.org/10.1177/00145858231185833.Suche in Google Scholar

Bhatia, Vijay Kumar. 2004. World of written discourse: A genre-based view. London: Continuum.Suche in Google Scholar

Bhatia, Vijay Kumar. 2006. Discursive practices in disciplinary and professional contexts. Linguistics and the Human Sciences 2(1). 5–28. https://doi.org/10.1558/lhs.v2i1.5.Suche in Google Scholar

Bhatia, Vijay Kumar. 2017. Critical genre analysis: Investigating interdiscursive performance in professional practice. London: Routledge.Suche in Google Scholar

Biber, Douglas, Geoffrey Leech & Stig Johansson. 1999. Longman grammar of spoken and written English. Harlow: Pearson Education.Suche in Google Scholar

Cappelli, Gloria. 2023. Sun, sea, sex and the unspoilt countryside: How the English language makes tourists out of readers, 2nd edn. Pari: Pari Publishing.Suche in Google Scholar

Cilkin, Remziye Erici & Beycan Cizel. 2022. Tourist gazes through photographs. Journal of Vacatation Marketing 28. 188–210. https://doi.org/10.1177/13567667211038955.Suche in Google Scholar

Dann, Graham. 1996. The language of tourism. A sociolinguistic perspective. Oxford: CAB International.Suche in Google Scholar

De Marco, Alessandra. 2017. Destination brand New Zealand. A social-semiotic multimodal analysis. Perugia: Morlacchi.Suche in Google Scholar

Denti, Olga & Luisanna Fodde. 2017. What is Sardinia’s destiny? Cultural heritage and cross–cultural tourist marketing constraints in institutional communication. Letterature straniere & 17. 101–119.Suche in Google Scholar

Elan, Caroline & Ana Debenedetti. 2019. Botticelli past and present. London: UCL Press.10.2307/j.ctv550cgjSuche in Google Scholar

Francesconi, Sabrina. 2011. Images and writing in tourist brochures. Journal of Tourism and Cultural Change 9(4). 341–356. https://doi.org/10.1080/14766825.2011.634914.Suche in Google Scholar

Francesconi, Sabrina. 2014. Reading tourism texts: A multimodal analysis. Bristol: Channel View.10.21832/9781845414283Suche in Google Scholar

Francesconi, Sabrina. 2018. Heritage discourse in digital travel video diaries. Trento: Tangram.Suche in Google Scholar

Francesconi, Sabrina. 2024. #venereitalia23 come ambasciatrice e influencer virtuale: un’analisi socio-semiotica. In Barbara Antonucci & Eleonora Gallittelli (eds.), Beyond the Last ‘Post-’. Il turismo e le sfide della contemporaneità, 71–90. Roma: Roma TrE-Press.Suche in Google Scholar

Hallett, Richard W. & Judith Kaplan-Weinger. 2010. Official tourism websites: A discourse analysis perspective. Clevedon: Channel View.10.21832/9781845411381Suche in Google Scholar

Hiippala, Tuomo. 2015. The structure of multimodal documents: An empirical approach. London: Routledge.10.4324/9781315740454Suche in Google Scholar

Italia . Open to Meraviglia ENIT campaign video. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=toGef597MG0 (Accessed 10 June 2024).Suche in Google Scholar

Koprivica Lelićanin, Marija. 2024. Italianicity is in the eye of a beholder: Analysis of audience reception to the Italian tourist campaign Italia: Open to meraviglia. Bulletin of the Institute of Ethnography SASA, [S.l.] 72(1). 201–227.10.2298/GEI2401201KSuche in Google Scholar

Kress, Gunther & Theo Van Leeuwen. 2021. Reading images: The grammar of visual design, 3rd edn. London: Routledge.10.4324/9781003099857Suche in Google Scholar

Kumar, Prem, Mohan Jitendra Mishra & Venkata Yedla Rao. 2021. Analysing tourism destination promotion through Facebook by destination marketing organizations of India. Current Issues in Tourism 25(9). 1416–1431. https://doi.org/10.1080/13683500.2021.1921713.Suche in Google Scholar

Maci, Stefania. 2020. English tourism discourse: Insights into the professional, promotional and digital language of tourism. Milano: Hoepli.Suche in Google Scholar

Malamatidou, Sofia. 2024. Translating tourism: Cross-linguistic differences of alternative worldviews. London: Palgrave.10.1007/978-3-031-49349-2Suche in Google Scholar

Manca, Elena. 2016. Persuasion in tourism discourse: Methodologies and models. Newcastle upon Tyne: Cambridge Scholars.Suche in Google Scholar

Masuda, Hisashi, Spring Han & Jungwoo Lee. 2022. Impacts of influencer attributes on purchase intentions in social media influencer marketing: Mediating roles of characterizations. Technological Forecasting and Social Change 174(ID). 121246. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techfore.2021.121246.Suche in Google Scholar

Mattei, Elena. 2024. Approaching tourism communication with empirical modality: Exploratory analysis of Instagram and website photography through data-driven labeling. Frontiers communication 9. 1355406. https://doi.org/10.3389/fcomm.2024.1355406.Suche in Google Scholar

Poletti, Federico. 2007. Botticelli. Milano: Mondadori.Suche in Google Scholar

Pritchard, Annette & Nigel J. Morgan. 2000. Privileging the male gaze: Gendered tourism landscapes. Annals of Tourism Research 27(4). 884–905. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0160-7383(99)00113-9.Suche in Google Scholar

Pritchard, Annette. 2001. Tourism and representation: A scale for measuring gendered portrayals. Leisure Studies 20(2). 79–94. https://doi.org/10.1080/02614360110068651.Suche in Google Scholar

Robinson, Mike & David Picard. 2016. Moments, magic and memories: Photographing tourists, tourist photographs and making worlds. In Robinson Mike & David Picard (eds.), The framed world: Tourism, tourists and photography, 1–38. London: Routledge.Suche in Google Scholar

Sirakaya, Ercan & Sevil Sonmez. 2000. Gender images in state tourism brochures: An overlooked area in socially responsible tourism marketing. Journal of Travel Research 30. 353–362. https://doi.org/10.1177/004728750003800403.Suche in Google Scholar

Smith, Sean P. 2021. Landscapes for “likes”: Capitalizing on travel with Instagram. Social Semiotics 31. 604–624. https://doi.org/10.1080/10350330.2019.1664579.Suche in Google Scholar

Urry, Jonathan. 2002. The tourist gaze: Leisure and travel in contemporary societies, 2nd edn. London: Sage.Suche in Google Scholar

Venereitalia23 Instagram page. https://www.instagram.com/venereitalia23/ (Accessed 10 June 2024).Suche in Google Scholar

Yesiloglu, Sevil & Costello Joyce. 2021. Influencer marketing: Building brand communities and engagement. Abingdon, Oxon: Routledge.10.4324/9780429322501Suche in Google Scholar

Zappavigna, Michele. 2016. Social media photography: Construing subjectivity in Instagram images. Visual Communication 15(3). 271–292. https://doi.org/10.1177/1470357216643220.Suche in Google Scholar

© 2025 the author(s), published by De Gruyter, Berlin/Boston

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Frontmatter

- Research Articles

- The role of gestures in logic

- A multimodal discourse analysis of the music video ‘IBA’

- Discourses of division during the cost-of-living crisis: digital popular culture responds to governmental actions

- Italia: Open to meraviglia at the intersection of art, gender and tourism discourses

- ‘Why do they not want to play with me?’: a multimodal critical discourse analysis of the construction of colourism in cartoon films

- Essay

- Multimodal (inter)action analysis in sociolinguistics: an essay analysing a digital video conversation illustrating emotion and heritage language maintenance

- Research Articles

- ‘Title gone’: a multimodal appraisal of Nigerian internet users’ visual representation of Arsenal football club

- Beyond bonding icons: memes in interactional sequences in digital communities of practice

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Frontmatter

- Research Articles

- The role of gestures in logic

- A multimodal discourse analysis of the music video ‘IBA’

- Discourses of division during the cost-of-living crisis: digital popular culture responds to governmental actions

- Italia: Open to meraviglia at the intersection of art, gender and tourism discourses

- ‘Why do they not want to play with me?’: a multimodal critical discourse analysis of the construction of colourism in cartoon films

- Essay

- Multimodal (inter)action analysis in sociolinguistics: an essay analysing a digital video conversation illustrating emotion and heritage language maintenance

- Research Articles

- ‘Title gone’: a multimodal appraisal of Nigerian internet users’ visual representation of Arsenal football club

- Beyond bonding icons: memes in interactional sequences in digital communities of practice