Abstract

In this article we explore various properties of direct objects in Russian that may condition the preference for a preverbal versus postverbal position of the object, against the general trend towards VO constituent order in Russian. First, we show that a preference for OV over VO order is associated with (in order of increasing effect size) animacy and definiteness of the object, personal pronouns in object function and pronominal object clitics. We argue that the main determining factor is accessibility of the referent. Russian follows the general trend of languages to place constituents conveying more accessible information sentence-initially, regardless of their distance to the verb. This is hypothesized to be efficient from the perspective of incremental speech processing. Likewise, we show that the bias towards a postverbal position of the object phrase is a function of the length of that phrase. This tendency is conditioned by Hawkins’ Minimize Domain Principle, which is assumed to optimize sentence processing. Finally, we report an effect of negation on the preference for OV order, and we provide evidence against the claim that in Russian, word order is employed for the discrimination of subjects from objects if case fails to disambiguate. More generally, we suggest that Russian has no grammatical conventions for word order and is therefore a truly free-word-order language in which the ordering of elements is constrained by cognitive and discourse related factors, not conventionalized in the form of grammatical rules.

1 Introduction

Slavic languages only have a few hard constraints on the linear position of words or constituents in a clause, such as the position of the relative pronoun in the relative clause, the position of clitics (e.g. Franks and King 2000; Migdalski 2016: Ch. 3–4) and the head-dependent order in converbial clauses (Isačenko 1966). Otherwise, Slavic word order is free, allowing all six logically possible orders of the three elements (S)ubject, (V)erb and (O)bject (Bailyn 2012: Ch. 6; Biskup 2011: Chs. 2–3; Błaszczak 2005; Dyakonova 2009: Ch. 3; Kosta and Schürcks 2009; Krylova and Khavronina 1986; Kučerová 2007: Ch. 1; Slioussar 2007: Ch. 1; Witkoś 1993: 291ff.). Russian, the language under study in this article, has free word order on the level of the clause constituents (e.g. Yokoyama 1986: 171).[1] In this study, we adopt a bottom-up, usage-based, corpus-based approach and treat various word order combinations as forming a set of alternatives none of which is syntactically more basic or (more) derived than another (for similar work on Polish, see Czardybon et al. 2014; Jacennik and Dryer 1992).

Like the other Slavic languages — with the exception of Sorbian — Russian is a default SVO language (Siewierska and Uhliřová 1998; the canonical/neutral order in the generative tradition, see Babyonyshev 1996: Ch. 2; Bailyn 2003, 2012: Ch. 6; Dyakonova 2009: Ch. 3; Titov 2017; but see Haider and Szucsich 2022). SVO is the most frequent word order pattern found in Russian (Bivon 1971). It is also the most flexible one in terms of information structure (see Dryer 1995 on the notion). Needless to say, classifying a language as SVO is just a coarse typological approximation (Downing 1995: 19; Mithun 1987; see also Levshina et al. 2023 for the quantitative evidence) and SVO languages of course considerably vary in terms of the frequencies of the various word order patterns, the degrees of conventionalization of the basic or canonical word order, and the specific syntactic, semantic, pragmatic, discourse-related, and sociolinguistic properties associated with the selection of a specific word order.

We argue that the clausal word order of Russian should be treated as being truly free, in the sense that Russian speakers do not have any grammar-based – i.e., conventionalized – constraints on ordering the elements in the sentence, as opposed to the languages in which grammatical conventions may require a certain order, e.g., the initial position indicating the syntactic role of subject in English.

In a free-word-order language like Russian, the only factors that affect the arrangement of words in the sentence can be roughly grouped into two domains: (i) the cognitive domain and (ii) the discourse domain.

(i) The cognitive domain involves factors that derive from human sentence production and comprehension mechanisms. It is these factors whose indirect effects on sentence production we explore in this study. We suggest that Russian word order variation is rooted in the ways speech is produced and processed. An important set of factors heavily constraining word order pertain to the efficien cy of processing (Downing 1995: 12). For example, we argue that the length of the object heavily affects word order so as to minimize production and comprehension costs. The underlying reasoning is that speakers tend to economize on production costs as long as they achieve communicative success (Gibson et al. 2019). Our evidence is twofold.

First, we show that expressions encoding ready-made and/or easily accessible referents from previous mentions or from the common ground are articulated early in the sentence; these are primarily animate and/or definite referents (Kempen and Harbusch 2004; Tanaka et al. 2011). We provide evidence for this effect in Russian in Sections 4, 5 and 6 below. The motivation for the early placement of accessible referents in the sentence (by hypothesis) is the inherently incremental nature of speech production and comprehension. Incremental speech production entails that as soon as a piece of information is planned in working memory it is articulated in order to reduce working-memory demands and planning costs (see Bresnan et al. 2007; Ferreira and Yoshita 2003 and many others on availability-based production).

Second, efficient processing affects word order in another way. Comprehension can proceed efficiently if the head signaling the type of the upcoming phrase is recognized early by the comprehender. They therefore show a tendency to be articulated early (audience design). Hawkins’ principles Minimize Domains and Early Immediate Constituents predict exactly this (Hawkins 2004, 2014; see also Futrell et al. 2015; Liu 2020). We argue that the word order of direct objects in Russian is crucially dependent on the length of object phrases (in word tokens) in Section 7. Longer object phrases inhibit early head recognition (i.e., of the verbal phrase) if preceding the verb. By contrast, early head recognition is not inhibited if long object phrases follow the verb. Short objects do not have this effect.

Another aspect of efficiency in processing concerns the recognition of semantic roles, e.g., in terms of Dowty’s (1991) proto-agent versus proto-patient, because proto-agents and proto-patients are naturally biased towards the syntactic roles of subject and object, and towards the information-packaging roles of topic and focus, respectively. The discriminatory function is the need to distinguish between the main participants (inter alia, Aissen 2003; Comrie 1978, 1981; Dixon 1994; Malchukov 2008; Seržant 2019; Silverstein 1976; see, however, Levshina 2019; for Slavic, see “grammatical function” in Sirotinina 1965 [2003]: 5; Junghanns and Zybatow 1997: 313; Jasinskaja and Šimík subm.). However, we do not find any support for the discriminatory function of word order in Russian, despite earlier claims to that effect (Section 8).

(ii) The discourse domain is inhabited by various sets of discourse and situation-related factors that have been claimed to constrain word order, for example, information packaging (also called information structure). Much of the previous research primarily focused on the information-packaging function as the main factor behind different word order patterns (inter alia, Adamec 1966; Daneš 1974; Junghanns and Zybatow 1997; King 1995; Paducheva 1985; Rodionova 2001; Sirotinina 1965 [2003]). For example, information packaging favors the topic-before-comment placement of constituents as well as the postverbal placement of focus (e.g., Dyakonova 2009: 55; Junghanns 2001: 331). The following examples illustrate this.

| Kto | ponjal | moj | vopros? |

| who | understand.pst.sg | my | question.acc |

| ‘Who understood my question?’ | |||

| Vaš | vopros | ne | ponjal | nikto. |

| your | question.acc | neg | understand.pst.sg | nobody.nom |

| ‘No one understood your question.’ | ||||

In (1b), the topic vaš vopros ‘your question’ is placed sentence-initially and preverbally, and the focus nikto ‘none’ is placed postverbally and sentence-finally, as expected. This is the default, i.e., unmarked, linear alignment of information-packaging roles in Russian and other Slavic languages (Adamec 1966: 20ff.; Dyakonova 2009: 55; Kovtunova 1976; Sgall et al. 1986; Veselovská 1995: Ch. 10).

Below (Section 4), however, we argue that information-packaging roles might represent just proxies for other sorts of effects, and we follow the literature that argues against topic and focus as universal linguistic categories that apply to any language. We argue that effects previously explained via positional biases of topics and foci may in fact be the result of (i) cognitive factors, foremost, accessibility and efficiency in speech production and comprehension.

Topic-comment and/or the focus-background roles are certainly not the only discourse factors. Discourse is a multifactorial phenomenon (cf. Kibrik 1996: 256) and there are many more discourse factors that may have an effect on word order beyond the topic and focus roles, e.g., different discourse registers (Sirotinina 1965 [2003]; Zemskaja 2011: 149). Thus, OV was found to be favored in colloquial language (52 % of OV vs. 48 % VO in Sirotinina’s 1965 [2003]: 48–49 data), whereas in scientific language and prose language OV is much rarer: 7–9% and 10–12 %, respectively (Sirotinina 1965 [2003]: 40–41; Slioussar 2009: 289). Levshina et al. (2023: 33) likewise find that Russian conversation has a much lower probability for VO than fiction and news. High variability of word order is particularly prominent in spontaneous and colloquial speech (e.g., Slioussar 2007: Ch. 5; Zemskaja 2011: 149).

There is another set of discourse and situation factors deriving from the interaction of the interlocutors that is known to affect word order, that is, interactional factors (overview in Downing 1995; “dialogic syntax” in Du Bois 2014; “intersubjective coordination” in Verhagen 2005). Here, factors such as turn-taking projectability have been shown to have an effect on word order, for example, for signaling the end of the turn (Selting and Couper-Kuhlen 2000: 86–89; Tanaka 2005) or the speaker’s affect (Downing 1995: 9).

Finally, there are factors generally affecting word order that are difficult to attribute to only the cognitive, or only the interactional factors of the discourse domain, since they involve cooperation during discourse (Du Bois 2014: 364) as well as enhancement in production and comprehension. Such is the effect of priming (cf. van Gompel et al. 2012), which is likely to play a role in the ordering of constituents. For example, response (2b) (SOV) may sound slightly more natural in the discourse situation in (2a) (SVO), whereas (2c) (SVO) is slightly less straightforward and may be an effect of priming the structure and word order of the question (2a) in the answer (e.g., for a specific social move such as respect). This is an aspect of analysis that remains to be explored.

| Kto | vidit | Sergeja? |

| who | see.prs.3sg | Sergej.acc |

| ‘Who is seeing Sergej?’ | ||

| Ja | jego | vižu. |

| 1sg.nom | 3sg.acc | see.1sg |

| ‘I see him.’ | ||

| Ja | vižu | jego. |

| 1sg.nom | see.1sg | 3sg.acc |

| ‘I see him.’ | ||

Suprasegmental effects have been claimed to affect word order, for example, in order to avoid particular sequences of stressed syllables (cf. Anttila et al. 2010; Jaeger et al. 2012 for English).

Bearing in mind that there are discourse and discourse-cognitive factors at play as well, below we explore only the effects of some cognitive factors on the ordering of the object constituents in Russian, arguing that the efficiency of sentence processing heavily influences the word order of Russian. In doing so, we proceed as follows: Section 2 describes our data.. Section 3 provides the basis for the detailed discussion in Sections 4–9 with statistical modeling. In Section 4, we show that accessibility of object input types (proxied here as the referential prominence of the input) has a strong probabilistic impact on word order – a phenomenon that aligns with the same cross-linguistic preference, and which is assumed to be causally rooted in processing efficiency. Section 5 discusses the effects of lexical verbs on word order, which are not independent but mostly derive from the accessibility biases of their objects (cf. Section 4). Section 6 details the effects of adjacency to the verb on the selection of OV versus VO word orders; these effects are also argued to follow from efficiency effects on sentence processing. Section 7 explores the effects of the length of the object phrase (measured in words) for the OV/VO choice. We show that longer object phrases are ordered in such a way as to achieve more efficient sentence processing. In Section 8, we report the effect of negation on the OV ordering. Finally, Section 9 provides evidence against the claim that the discriminatory function tends to exploit word order for its purposes in those instances where case-marking fails to do so. Section 10 summarizes the results and presents our conclusions.

2 Data and coding conventions

We generated two independent datasets for our study, Sample1 and Sample2, which we describe in brief below. All datasets, R and Python scripts used for this study are stored at zenodo.org and are freely downloadable (Seržant et al. 2024).

Sample1 is an excerpt from the syntactically annotated subcorpus of the Russian National Corpus (RNC).[2] This is a corpus of primarily written language. It contains papers from science and popular science journals, political discussions from 1980 onwards as well as fictional prose from the second half of the 20th to the beginning of the 21st century.

We selected 1572 tokens of transitive clauses. Verbs assigning the lexical genitive (alongside accusative) such as xotet’ ‘want’ (ACC or GEN) were excluded from the sample.[3] We annotated each clause with respect to the following criteria: negation (AFFIRM/NEGAT), aspect (PFV/IPFV/secondary IPFV), tense and mood, finiteness of the lexical verb, the order of object and the lexical verb (OV/VO), distance between the object and the verb (number of word tokens separating the two elements, including numbers), object type (NP, personal pronoun, demonstrative pronoun, proper name, etc.), object definiteness (definite/indefinite/generic), animacy, number, and the object case (accusative or genitive under the negation).

Since definiteness is not regularly marked in Russian, we annotated the definiteness of an object NP according to the following criteria: inherently definite expressions (such as personal pronouns or demonstratives) were always tagged as definite, while discourse-dependent definiteness was tagged depending on the rendition of the text in German by a bilingual annotator. When the German translation contained a definite article, the respective NP was marked as definite; otherwise it was tagged as indefinite or generic. Definiteness itself is largely a grammaticalization of identifiability in discourse (Lyons 1999), but identifiability, as clear as it might be for a researcher in a particular example and setting, is difficult to operationalize for an annotator to be consistent in their decisions. This is why we opted for definiteness in the German translation as a proxy – an option that is better falsifiable.

Sample2 was compiled in order to corroborate our results on the basis of a larger corpus. We extracted the data from the Universal Dependencies Treebank of Russian (version 2.11), with approx. 1,800,000 tokens, with a Python script.[4] This collection of texts represents a variety of genres: blog, fiction, poetry, social, wiki, contemporary fiction, popular science, newspaper and journal articles published between 1960 and 2016, texts from online news, etc. It is annotated for syntactic relations, most importantly, for objecthood and the governing verb, which are the focus of this study. Note that the texts in Sample1 and Sample2 overlap to some extent.

When extracting data from this corpus into Sample2, we only included clauses with the verb form tagged active (“Voice = Act”) and finite (“Person” tag must have been present in the annotation). We thus excluded passives, nominalizations and other forms that may have an independent impact on word order. In total, we arrived at 12,448 analyzed direct objects (this setzenodo.org as well as the Python code to extract the data are available in Seržant et al. 2024). Unfortunately, for technical reasons we could not take the alternating genitive-marked direct objects (the partitive genitive or the genitive under negation) into account. The direct objects in Sample2 are only those that were tagged accusative (regardless of whether distinctive from the nominative or not).

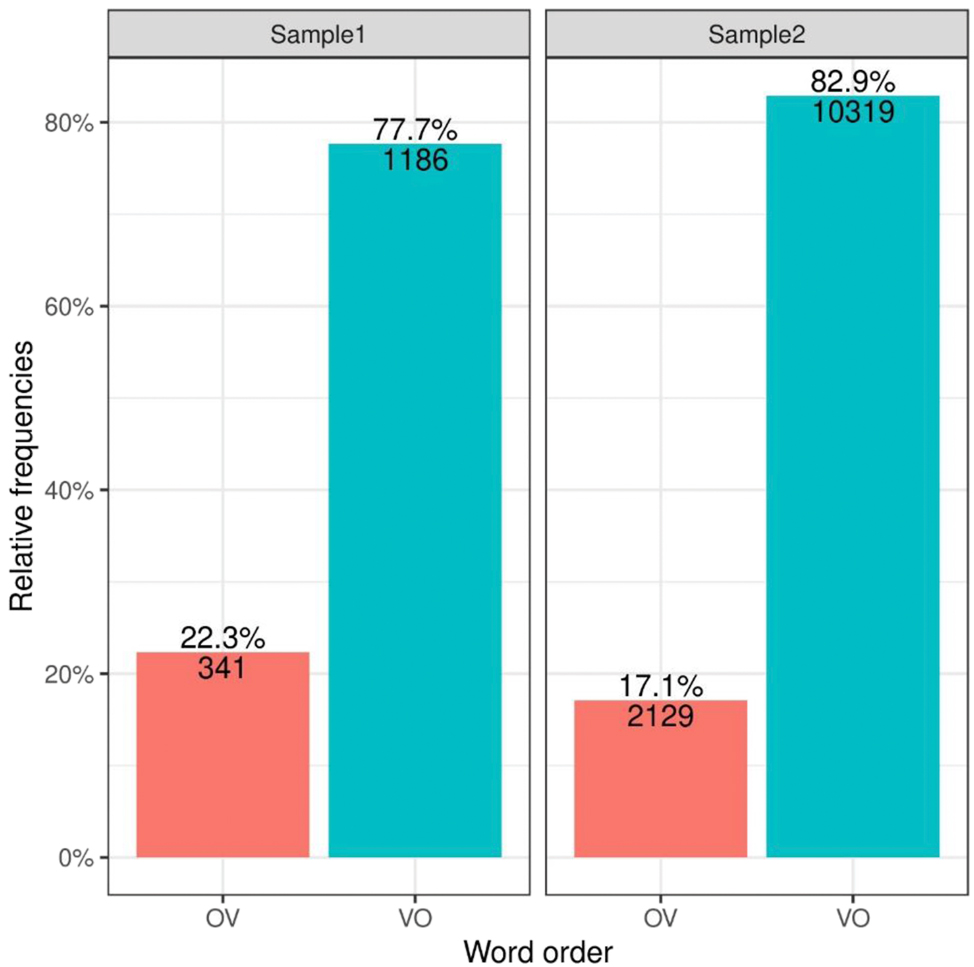

Since Sample1 and Sample2 contain somewhat different text collections, this has an effect on the overall distribution of OV versus VO, as is visualized in Figure 1.[5]

Word order frequencies in Sample1 and Sample2.

Sample1 consists of written texts only, whereas Sample2 is more approximated to spoken (and texting) language. The text sources of Sample1 are, on average, older than the sources of Sample2. Nevertheless, both samples exhibit the same general preferences.

3 Overview of results

Russian is generally a VO language (Figure 1). In order to explore the effects of different object, verb and clause properties on word order and possible interactions between these factors, we fitted binomial logistic regression models to the data from Sample1 and Sample2. This section provides an overview of these models and the main conclusions (i)-(vi) derived from them. The relevant R scripts and their outputs can be found at Seržant et al. (2024).

3.1 Model 1 based on Sample1

Before fitting a model, the data from Sample1 were slightly adapted to simplify the interpretation of the model. Pronominal objects were not taken into consideration because they show a different behavior than nominals (Section 4) and thus overload the model (failure to converge), reducing the number of observations from 1527 to 1204.

We performed mixed logistic regression analysis on Sample1 to examine the influence of all possible predictors (object animacy, object definiteness, polarity, finiteness, and aspect) on the variable word order with two values: “VO” and “OV”.[6] For the sake of convenience, the former was set as the reference level, i.e., the model calculated the coefficients for OV. Verb meaning was treated as a random effect. The calculation was conducted with the glmer function (R package “lme4” by Bates et al. 2015). The formula is: word order ∼ object animacy + object definiteness + negation + finiteness + aspect + (1|verb meaning). There are four conclusions (i)–(iv) one can make based on the model output:

The intercept is negative, which means that VO is generally more probable than OV (0.78 in case of Sample1, 0.74 for Sample2) when all fixed variables are at the reference level (i.e., singular, animate, definite, imperfective, finite affirmative clauses); see the discussion below.

The negative coefficient of object indefiniteness (estimated −0.6630, p ≈ 0.001) shows that the probability of the outcome “OV” significantly decreases for indefinite objects. For example, if all other predictors are at their reference level, the probability of having an indefinite object preceding the verb amounts to 0.13, while the probability of having a definite object preceding the verb is 0.22. We discuss more detailed evidence on definiteness, animacy and personal pronouns in Section 4, and their effects on the preferences of lexical verbs in Section 5.

Non-finiteness (with a coefficient estimate of −0.4026, p = 0.03) significantly reduces the probability of OV. This means that objects more often precede finite than non-finite verbs. We do not discuss this factor in detail. Our preliminary explanation here is that dependent infinitives generally tend to be placed immediately next to the main verb, and then the object follows. Thus, the word order in (3a) is more frequent than the one in (3b):

| Ja | budu | pisat’ | roman. |

| 1sg | aux.fut.1sg | write.inf | novel.acc |

| ‘I will write a novel.’ | |||

| Ja | budu | roman | pisat’. |

| 1sg | aux.fut.1sg | novel.acc | write.inf |

| ‘I will write a novel.’ | |||

By contrast, converbial and participial clauses require VO.

The opposite effect is shown for negative polarity (0.9825, p < 0.001). Other things being equal, the probability of OV in the clause with a negated predicate increases to 0.43. We discuss this factor in Section 8.

3.2 Model 2 based on Sample2

There were certain factors that we could not test with Sample1. Therefore, Sample2 was used in addition to Sample1 to primarily determine how the lengths of object phrases influence their linear positions – something that Sample1 would not allow for, given its size and annotation principles. Recall that Sample2 was extracted automatically from the Universal Dependencies Treebank and accordingly only contains the annotations provided by the corpus. Sample2, thus, contains only two numerical predictors: adjacency (the distance between the object and verb as the number of intermediate word tokens) and length of the object in word tokens. To avoid the effects of the object-dependent constituents embedded in the object NP, the adjacency is tested on objects expressed with one token only. Therefore, the number of observations reduces to 3858.[7]

For Sample2, we applied mixed effects logistic regression with adjacency as a fixed effect, the lexical verb as a random predictor with varying intercept, and the object lemma as a random predictor with varying intercept and slope. The formula looks as follows: word order ∼ adjacency + (adjacency|object lemme) + (1|verb meaning). We obtained the following results:

The adjacency coefficient estimate is positive (0.9012, p < 0.001), which means that the probability of OV increases by 0.19 on average, each time the verb moves away from the object by one token. For discussion, see Section 6.

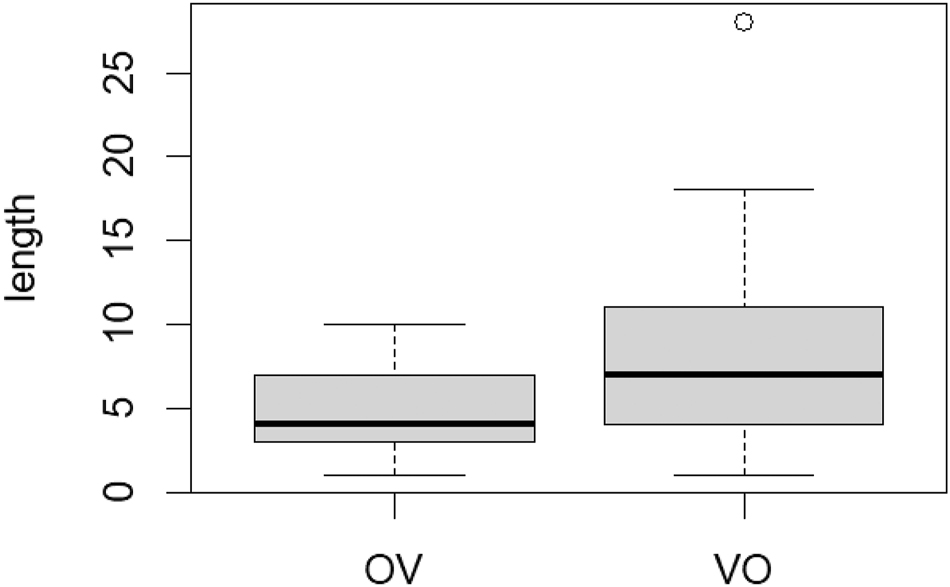

3.3 Model 3 based on Sample2

Another object feature that we claim to be a significant predictor of word order in Russian is object length (in tokens); details are discussed in Section 7. To test that hypothesis statistically, Model 3 based on Sample2 was fitted using the following formula: word order ∼ object length + (1 | verb meaning), where verb meaning is taken as a random predictor. Outliers with values higher than Q3 + 1.5 * IQR were removed from the sample. The modeling result based on 11,559 datapoints is as follows:

The longer the object, the lower the probability of OV (object length coefficient estimate is -0.28853, p < 2e-16). Each increase in an object by one token on average reduces this probability by 0.22.

To summarize all models, only such properties as shorter object length in tokens, longer object-verb distance (or non-adjacency of the object and the verb), definiteness, negative polarity, and finiteness are significantly relevant for placing the object before the verb in Russian. Other factors turn out to not be statistically significant in this regard.

Sections 4–8 provide detailed analyses and discussions of all factors triggering OV order, including animacy (not reaching significance in Sample1).

4 Accessibility of the object referent affecting OV versus VO

It is well-known that referential input properties of arguments – such as definiteness and/or animacy – affect the linear position of the arguments in the clause (often discussed in the literature under the labels prominence or saliency). This has also been discussed on various occasions specifically with respect to Slavic languages (see Jasinskaja and Šimík subm; Titov 2017; specifically on Polish, see Błaszczak 2001; on Czech, see Biskup 2011; Kučerová 2007). For example, Titov (2017) argues that the basic word order of the direct and indirect objects in Russian is DO-IO (IO-DO in Dyakonova 2009: 4; Junghanns and Zybatow 1997: 295; Sirotinina 1965 [2003]: 38) but presuppositionality and higher referential prominence of the input may change the order to IO-DO. In what follows, we build on these insights.

However, we argue that referential properties do not themselves influence word order. It is the more general cognitive phenomena relevant for speech production and processing that underlie them, as has been emphasized in the relevant literature (Jaeger and Norcliffe 2009: 868ff). Thus, the degree of accessibility (Ariel 1988, 2000), availability (Ferreira and Dell 2000; somewhat differently in Kibrik 1996) or the degree of activation (Chafe 1994) as well as topicality/topicworthiness (Givón 1979: 161–164, 1990: 198–199; Thompson 1995: 156–157) are the factors that influence speech production, and thus also word order. These terms, strictly speaking, refer to the amount of effort required to retrieve a referent from memory. However, we do not have access to speakers’ minds and thus cannot directly explore degrees of activation, availability, or accessibility. As these authors argue, we can, however, explore the effects of these phenomena on the utterances and on the way the referents are coded. Thus, in what follows we present indirect evidence for the accessibility of referents affecting the word order.

While the four approaches – availability, accessibility, activation, and topicality/topicworthiness – largely explore the same domain, they do so from different angles and with slightly different goals. For Ariel (1988, 2000), the accessibility of referents already introduced into the discourse depends on their inherent properties such as animacy, locator vs. non-participant, and on their contextual properties such as whether the referent was coded as grammatical subject in the preceding discourse, the distance from the previous mention (in sentences), etc. Givónian topicality/topicworthiness is similarly based on the grammatical and semantic role of the referent. Chafe’s notion of activation is likewise a cognitive notion that is about how much effort (“cognitive cost”, “activation cost”) the speaker and listener have to incur in order to (re)activate the referent (Chafe 1994: 72–75). Similarly, Kibrik (1996) explores the choice of referential devices used to code a participant – nominal versus pronominal – via its activation score based on a set of factors that combines fixed factors (animacy) and discourse factors (e.g., distance to the antecedent). While Ariel’s (1988, 2000) interest is to correlate accessibility with the (length of) coding and thus to predict whether the referent will be coded, e.g., with a full noun phrase, an independent pronoun, a clitic/index on the verb, or even zero, Givón (1979, 1990) and Thompson (1995) aim at predicting the cataphoric potential and the probability of the referent to re-occur as topic given the distance to its previous mentions, semantic roles, and grammatical roles (subject and agent are the most topical).

In what follows, we adopt Ariel’s notion of accessibility (Ariel 1988, 2000) and explore the correlation of accessibility of referents coded as direct objects to their linear positioning. Since we only discuss direct objects, we cannot say anything on how this grammatical role itself affects accessibility. We, therefore, restrict ourselves to only exploring different input types.

The position of the direct object in the monotransitive construction of Russian has the distributions shown in Table 1 and Table 2:

Word order preferences, (in)definiteness (Sample1).

| Definite | Indefinite | Generic | |

|---|---|---|---|

| OV | 28 % (218) | 19 % (97) | 11 % (26) |

| VO | 72 % (566) | 81 % (416) | 89 % (204) |

Word order preferences, animacy (Sample1).

| Animate | Inanimate | |

|---|---|---|

| OV | 38 % (83) | 20 % (258) |

| VO | 62 % (138) | 80 % (1048) |

Similar frequency distributions like those in Table 1 and Table 2 have been obtained previously, e.g., in Sirotinina’s (1965 [2003]: 48–49) corpus study (see also Czardybon et al. 2014: 147 for Polish). It follows from Table 1 that the preverbal position favors definite objects: 28 % of all definite objects occur pre-verbally, whereas only 19 % of indefinite objects take a pre-verbal position (see also Czardybon et al. 2014: 149 on Polish but cf. Šimík and Burianová 2020 on Czech). The difference between definite and indefinite NPs with respect to word order is statistically significant (Pearson’s χ2 p < 0.0003).

However, definiteness and animacy are generally not mutually independent factors. Animacy and definiteness are positively correlated in discourse: animate NPs tend to be definite, while inanimate NPs show a weaker tendency towards definiteness. Thus, we need to establish which of these factors is at play here, or whether they have an additive effect. In order to disentangle animacy and definiteness we computed the proportions of all four combinations with the two competing word orders in Table 3:

Word order preferences versus animacy and (in)definitenessa (Sample1).

| Animate, def | Animate, indef | Inanimate, def | Inanimate, indef | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| OV | 42 % (68) | 29 % (15) | 24 % (150) | 20 % (82) |

| VO | 58 % (93) | 71 % (37) | 76 % (473) | 80 % (379) |

-

aWe excluded all objects tagged as generic here (see Czardybon et al. 2014 for this issue in Polish).

Table 3 shows that both animacy and definiteness independently add up in favor of OV, weakening the general trend of the language towards VO. When both factors combine, the effect in favor of OV increases: animate definite objects are almost just as likely to be used with OV order (42 %) as with VO order (58 %), and the distribution here is close to chance. We conclude from this that animacy and definiteness both independently attract OV (Sirotinina 1965 [2003]: 45; Slioussar 2009: 289) against the general preference of nominal objects for VO in Russian.

Animate definite NPs encode referent types that are most frequently talked about (occurring as topics, see Geist 2010), which is why the referents encoded by these NP types are generally also among the most accessible ones.[8]

Personal pronouns are generally even more accessible than animate definite noun phrases (Ariel 2014 [1990]: 47). They show an even stronger preference for OV as opposed to VO (see Vinogradov and Istrina 1960: II, 682; Xolodilova 2013) and override the general trend towards VO.

We see that it is not simply animacy and definiteness that drive the trend torwards OV, since personal pronouns and animate definite NPs are equally animate and equally definite, and there should be no difference between these types of expressions if animacy and definiteness were the conditioning factors. Nevertheless, we observe a tendency to the effect that the higher the accessibility of the object type is, the more likely the object will occupy a preverbal position, even if it happens to be (part of) the focus in a particular utterance. To illustrate this, consider the following examples with pronominal objects, both occurring preverbally.

| Kto vyzval brigadu? |

| ‘Who called in the brigade?’ |

| Ja | jeje | vyzval. |

| 1sg.nom | 3sg.acc.f | call_in.pst.sg.m |

| ‘I called it in.’ | ||

| Ty s kem-nibud’ zdes’ znakom? |

| ‘Are you acquainted with anyone here?’ |

| Net, ja | tol’ko | vas | znaju. |

| neg 1sg.nom | only | 2pl.acc | know.prs.1sg |

| ‘No, I know only you.’ | |||

In (4b), it is the subject pronoun that is in focus, in (5b) it is the object pronoun. The preverbal position pragmatically represents the unmarked word order. This means that it is not the information-packaging role of topic itself that favors the preverbal position, since all pronouns (except reflexives and reciprocals) equally prefer the preverbal position. Rather, we claim, it is the accessibility of the object that drives the OV trend regardless of the actual information-packaging role of the object. Russian tends to place more accessible NP types into the preverbal position in a trade-off with the overall trend towards VO for all objects. Personal pronouns exhibit this trend in the most pronounced way and even tend to develop (en)clitic properties (Xolodilova 2013: 92).

What is more, the unstressed, shortened forms of the personal pronouns are even more accessible (Ariel 2014 [1990]: 62) and show an even stronger bias towards OV than the respective independent pronouns. While the written language – as represented in our samples – do not reflect the difference between the stressed and unstressed personal pronouns in Russian, the spoken language does maintain this distinction, with unstressed forms being tja ‘2sg.acc’ or mja ‘1sg.acc’. These pronouns occur exclusively as part of the background and may not be used, e.g., in contrastive focus, in which case the stressed full form of the pronoun is used. Reduced pronouns have a statistically significantly higher preference for OV than their orthotonic counterparts, as is shown in Xolodilova (2013: 77) for tja (71 % of OV) in comparison with the potentially orthotonic pronoun tebja ‘2sg.acc’ (52 %).[9] Note that even enclitic personal pronouns may be found in the postverbal position, despite the fact that they are inherently topics.

Theoretically one may also claim that it is not accessibility but the likelihood of being a topic that drives OV order. However, there are quite a few difficulties with a purely information-packaging account here. First, there is no direct link between information-packaging roles and specific linear positions, such that the topic would be preverbal and the focus postverbal (see Dyakonova 2009: 55; Junghanns 2001: 331; Rodionova 2001: 27, 31). For example, Rodionova (2001: 27, 31) claims that the preverbal object is always presupposed and topical. Sirotinina (1965 [2003]: 40) argues that the preverbal position of the object is mostly the first position in the sentence, in which the object is the topic, whereas backgrounded objects in a non-first preverbal position are rare. However, examples like (4b) and (5b) show that the preverbal position may also host foci; consider (6), in which the focused and (via referential anchoring) definite objects with the role of focus occur preverbally:

| I | kepočku | davaj, | i | čemodančik | priberu | kuda, | čtoby |

| and | hat.acc.sg | permissive | and | suitcase.acc.sg | put.prs.1sg | where | that.SUBJ |

| ty | znal. | ||||||

| you | know.pst.sg.m | ||||||

| ‘Let me put (your) hat and suitcase somewhere where you would know.’ | |||||||

| (L. N. Tolstoy, “Fireplace”, Sirotinina 1965 [2003]: 46) | |||||||

Analogously, the postverbal position is often taken to be focal by default. However, if this direct linkage were invariably true, we would have to assume that personal pronouns occur as foci or (part of) the comment in 38 % of all their occurrences in our sample (see Table 4), since they are found in postverbal position in 38 % of all their occurrences. This is, however, unlikely, since personal pronouns are known to be (secondary) topics most of the time, even in postverbal position (see Lambrecht 1994: 147 on primary and secondary topics), as shown in (7b):

Word order preferences versus different parts of speech (Sample1).

| OV | VO | |

|---|---|---|

| Full NPs, including proper names | 13 % (166) | 87 % (1066) |

| Reflexive and reciprocal pronouns | 11 % (3) | 89 % (24) |

| Personal pronouns | 62 % (62) | 38 % (38) |

| Liš’ tol’ko on otvoril dver’... |

| ‘As he opened the door...’ |

| Tanja | srazu | že | uvidela | jego | i | vyšla. |

| Tanja.nom | right | away | see.pst.sg.f | 3sg.acc | and | go_out.pst.sg.f |

| ‘Tanja saw him right away and went out.’ | ||||||

| (Jurij Trifonov, “Obmen”, 1969, RNC) | ||||||

To conclude, in Russian topics and foci are not directly linked with OV and VO order, respectively. At most, there could appear to be a probabilistic trend towards OV and VO via their correlation with accessibility, such that the more accessible referents tend to be topics, and the less accessible ones are often foci. Unfortunately, we do not have tagged data available to explore this any further. Such data would require tagging all objects for the roles of topic and focus, and comparing the predictions of these information-packaging roles with the predictions based on accessibility. It is notoriously difficult to objectively tag natural corpus data for focus and topic since no questions can be asked by the tagger like in the question-under-discussion model, which is better designed for experiments. Thus, Tomlin (1995: 517) mentions that “empirical difficulties identifying instances of themes or topics in actual discourse data” are, foremost, “definitions whose application in specific data analyses requires too much dependence on introspection or indirectly permits the use of structural information in the identification of instances of the key category” (Tomlin 1995: 520; see also other voices from corpus linguistics on difficulties annotating information structure, such as low inter-annotator agreement: Cook and Bildhauer 2011 or Lüdeling et al. 2014: 609). For example, the following example (courtesy of a reviewer) – even though integrated into a context – may have two distinct information-structural interpretations. The object in (8c) jego may either be interpreted as the contrastive focus (Why are you asking me? Ask him!) or as just the (secondary) topic (No idea, you should ask him) and the annotator would be forced to a subjective interpretation of the example in (8c):

| Čelovek toropitsja. |

| ‘A person is hurrying.’ |

| Kuda? |

| ‘Where?’ |

| Ne | znaju, | sprosi | jego. |

| neg | know.1sg | ask.imp.sg | 3sg.acc |

| ‘I don’t know. Ask him.’ | |||

| (Sirotinina 1965 [2003]: 51) | |||

In addition to these inherent falsifiability issues, recent research has generally questioned the linguistic applicability of the notions of topic and focus for various reasons (Frajzyngier and Shay 2016: 103; Matić and Wedgwood 2013; Ozerov 2015, 2018, 2021) and urged to recast these notions into cognitive notions such as attention (Tomlin 1995: 518).

Thus, instead of referring to topic and/or focus, we argue that accessibility is the main reason behind the preference for OV in Russian, which is statistically a VO language. This aligns with cross-linguistic evidence. As has been repeatedly claimed in the typological literature (inter alia, Ariel 1988; Du Bois 1987; Firbas 1992), languages generally tend to first articulate the information that is immediately available from previous discourse or the common ground, or easily retrievable from long-term memory. The tendency towards the beginning of the sentence is not rooted in the theoretical concept of topichood but rather in the cognitive mechanisms of speech production that maximize efficiency. Efficiency is defined as high-transmission accuracy under minimal effort for both the speaker and the hearer to process information (Gibson et al. 2019). Efficiency effects are found in production, comprehension, and learning (Christiansen and Chater 2016; Hawkins 2004; MacDonald 2013; O’Grady 2015).

We follow recent research from psycholinguistics showing that efficient speech production is the mechanism that is responsible for the order of elements in an utterance. The tendency for more accessible information to be uttered first is rooted in the incremental nature of human speech production and in the limited processing resources available to a human speaker and hearer (Jaeger and Norcliffe 2009: 869). Studies such as Pöppel (2009) and Wittmann (2011) have shown that the capacity of the working memory in which upcoming utterances are formed is approx. a 3-second window of speech. Overloading the working memory with the pre-planned material is known to be dispreferred for that reason (cf. the Now-or-Never bottleneck in Christiansen and Chater 2016: 5; see neurolinguistic evidence in Swaab et al. 2003). Ready-made items are therefore immediately passed on to the articulatory system in order to free up working memory capacities for the production of the upcoming information. Given the limited amount of resources available to a human speech producer, those chunks of information that are already available – e.g., from previous discourse and/or the common ground shared by the interlocutors – are articulated immediately in order to free up the resources of the working memory, and of the processor for the production of the upcoming information (Ferreira and Yoshita 2003; Kempen and Harbusch 2004). Ferreira and Dell (2000: 299) call this the Principle of Immediate Mention: “Production proceeds more efficiently if syntactic structures are used that permit quickly selected lemmas to be mentioned as soon as possible” (see more literature on this in Jaeger and Norcliffe 2009: 869). While English, for example, has to resort to special constructions allowing for non-canonical order of participants such as the passive voice, Russian is a free-word-order language in which the linear position of argument constituents does not bear any grammatical information, and thus its word order is directly responsive to efficiency pressures.

Moreover, our efficiency-based explanation of the pressure for more accessible referents to occur in OV is supported by other effects discussed below, such as the biases in verb adjacency that are very different in OV and VO orders. Before we turn to these in Section 6, we briefly discuss the effects of lexical verbs on word order in the following section. We suggest that this effect is primarily driven by accessibility preferences that these verbs have on their objects and that, therefore, this effect is a side-effect of the general pressure for more accessible referents to be placed early in the utterance.

5 Word order preferences of different lexical verbs

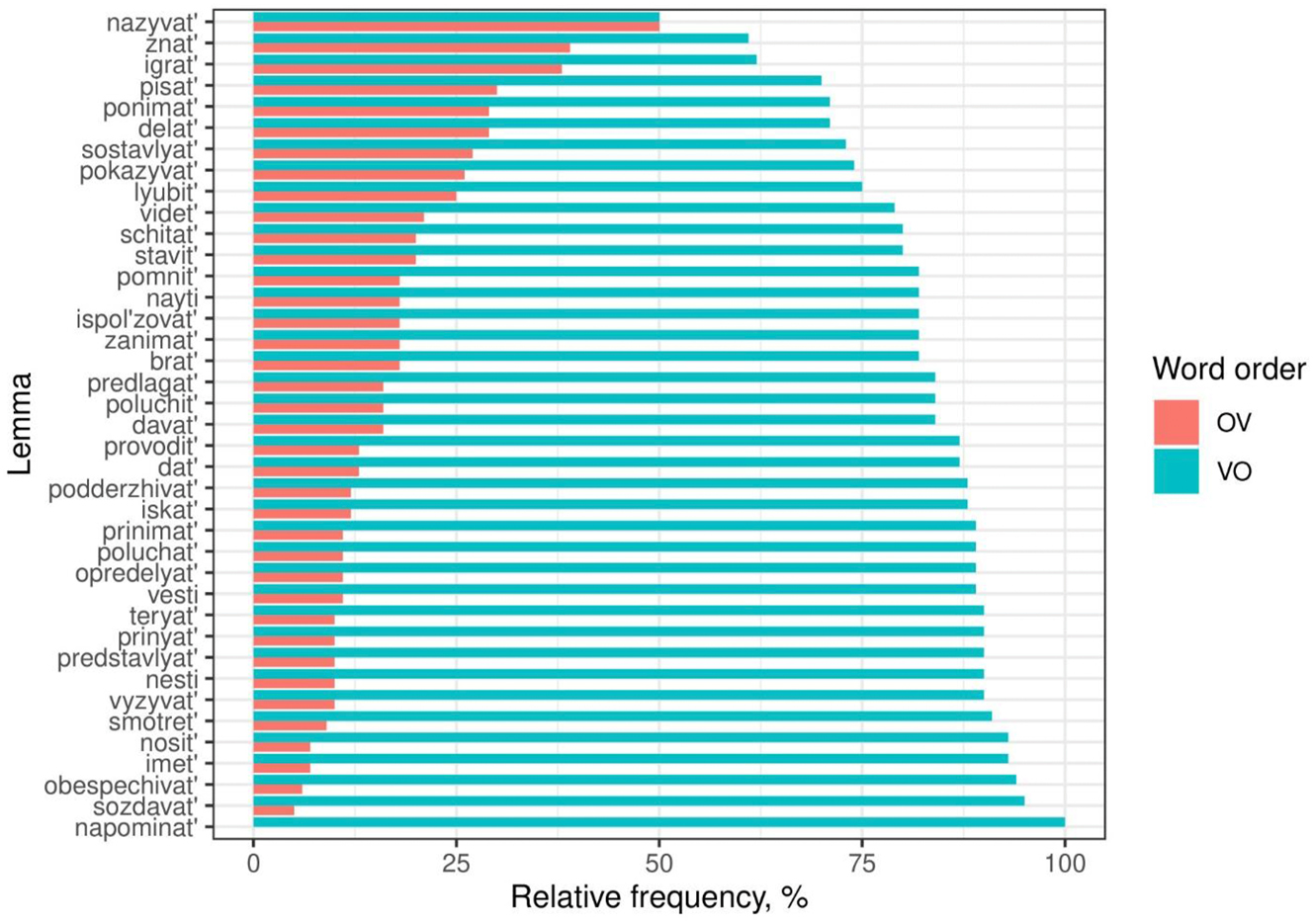

The word order of direct objects in Russian is also affected by the lexical verb. Different lexical verbs vary greatly in their preferences for OV or VO. In what follows, we only discuss Sample2 (because of its size), but the figures from Sample1 are comparable:

What one clearly observes from Figure 2 is that those verbs that predominantly take inanimate objects – napominat’ ‘to call to mind’, sozdavat’ ‘to create’, obespečivat’ ‘to supply’, imet’ ‘to have, possess’, nosit’ ‘to carry’, etc. – show a very low ratio of OV, whereas those verbs that may take both types of objects – like znat’ ‘to know (of)’ or nazyvat’ ‘to call, give a name to’ – show a somewhat higher degree of OV. Thus, for example, sozdavat’ ‘to create’ is used 11 times with inanimate objects and never with animate ones, and imet’ ‘to have, possess’ from Sample1 behaves similarly (45 vs. 0; animacy is not tagged in Sample2, Section 2). By contrast, nazyvat’ ‘to call/give name to sb./smth.’ is used 16 times with inanimate and 7 times with animate objects (30 %); znat’ is found with 11 inanimates and 1 animate object (8 %).

Word order preferences of lexical verbs (only verbs with 50+ occurrences in Sample2).

However, there are also verbs like pisat’ ‘to write’ which only take inanimate objects but nevertheless have a somewhat higher ratio of OV. Since definiteness is also a factor favoring OV (see Sections 3 and 4) it may be definiteness that increases the frequency of OV order with such verbs. However, this has to be explored further in another study. Consider also the results obtained by Pičxadze and Rodionova (2011), who show that particular lexicalized verb-object combinations are predominantly used with OV order, whereas compositional combinations tend towards VO order already in Old East Slavic.

6 Word order and the degree of adjacency of the direct object to the verb

Here, we rely on Sample2. The distance between the object and the verb was operationalized as the distance between the verb and the head of the object phrase. Note that this method artificially increases the number of non-adjacent objects in both VO and OV sentences. In OV, if the head of the object phrase is modified to the right, as in the following example (9), the distance artificially increases. The same holds for objects modified to the right in VO sentences.

| Razmyšlenija | o | svjazi | nalogov | i | tiranii | my |

| thought.acc/nom.pl | about | connection | tax.gen.pl | and | tyranny.gen.sg | 1pl |

| naxodim | i | u | Aristotelja. | |||

| find.1pl | and | at | Aristotle | |||

| ‘We also find thoughts on the connection between taxes and tyranny in Aristotle.’ | ||||||

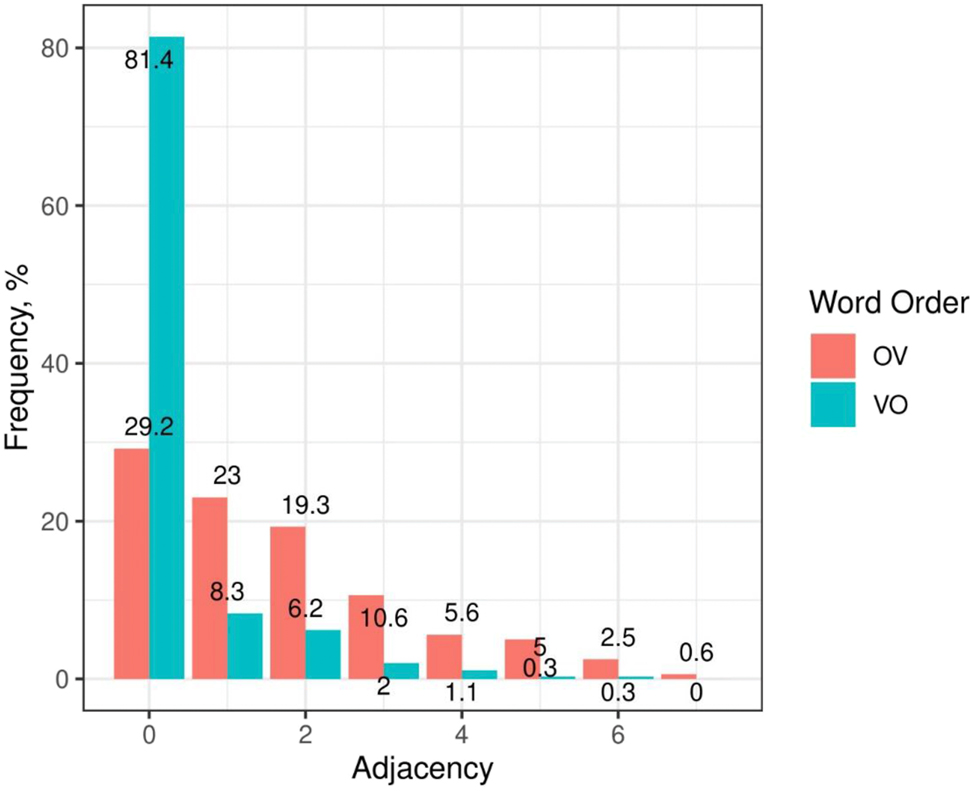

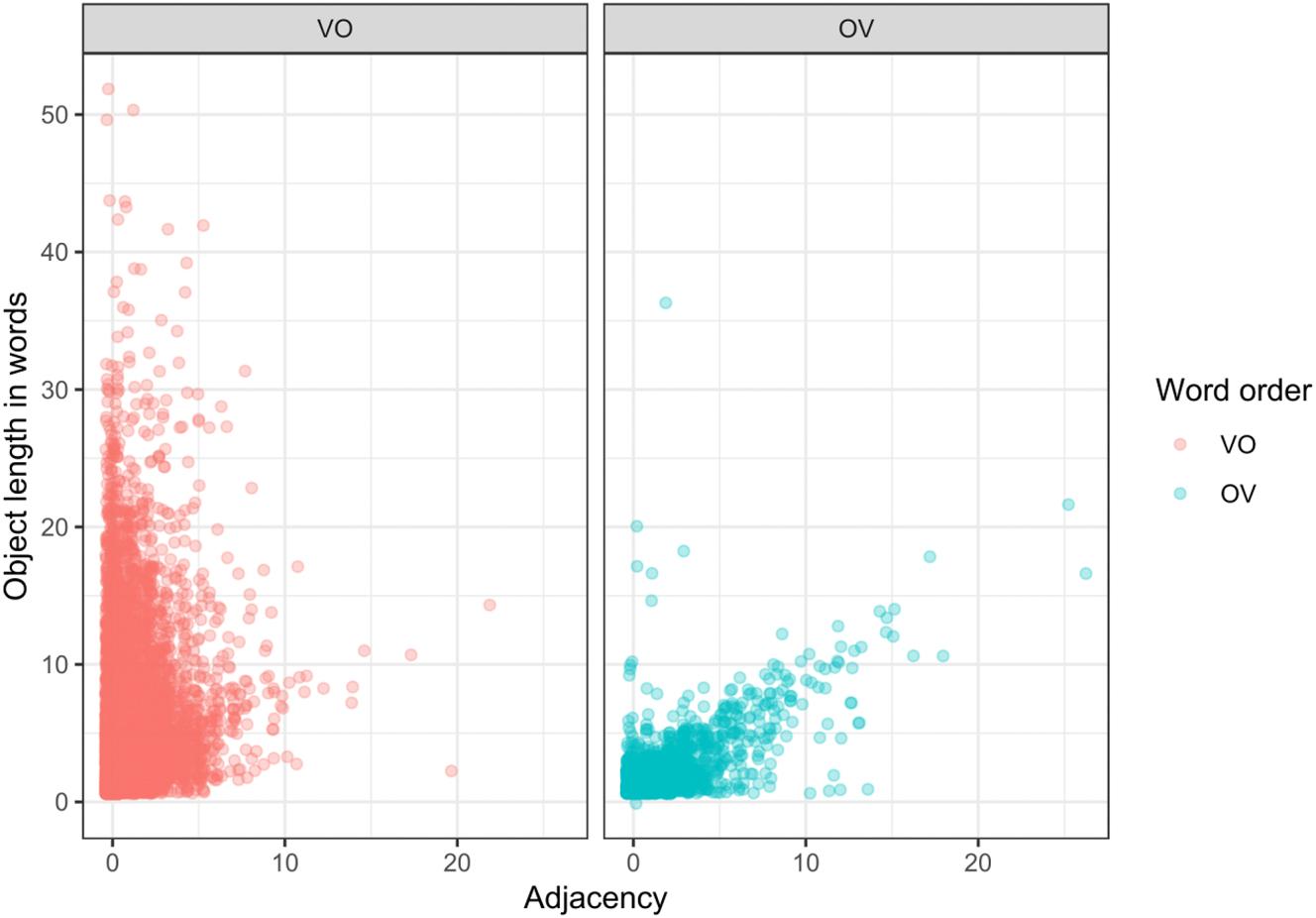

We found a preference for OV with objects that are more distant from the verb.

While there are many more objects following the verb than objects preceding the verb, the latter are more frequently used non-adjacently to the verb than the former. More generally, the verb-object distance (in word tokens) displays more variation in the OV configuration (Figure 3). By contrast, most of the postverbal objects – ca. 80 % – occur immediately adjacent to the verb (the distance is zero in this case). Importantly, there is no distinction between personal pronouns and nouns in this regard. The same tendency is observed with personal pronouns and there is, thus, no tendency towards stronger positional bonds of these with the verb in OV order.

Adjacency preferences of OV versus VO placed objects in Sample2 measured as the number of the intervening word tokens.

The fact that postverbal direct objects generally tend to occur immediately next to the verb has been observed in previous literature (Junghanns and Zybatow 1997: 294–295; Sirotinina 1965 [2003]: 40). Only if the verb additionally takes an oblique argument or an indirect object do these elements tend to precede the direct object (Sirotinina 1965 [2003]: 39):

| …vzjal | iz | pečurki | kolodu | kart | i | kiset. |

| take.pst.sg | from | stove | deck.acc.sg | card.gen.pl | and | pouch.acc.sg |

| ‘(Stepan) took the card deck and (tobacco) pouch from the stove.’ | ||||||

| (Tixij Don, p. 166; Sirotinina 1965 [2003]: 39) | ||||||

In Section 4 we argued that the OV preference of more accessible referents is rooted in the general tendency of speakers towards the early articulation of those pieces of information that are easily retrievable from memory, or are readily available from previous discourse or the common ground, in order to free up working memory for the production of the upcoming information. The same explanation also accounts for – on average – larger distances of objects from the verb in OV word order. Readily available and/or easily retrievable information is uttered first, regardless of what may follow after that since speech production and comprehension are inherently incremental. Thus, the distance to the verb does not really matter here. However, our explanation would only be consistent if the preverbal objects were in general quite short (in terms of word length) so as not to overly increase the comprehension costs of the entire utterance (which would be be a consequence if the preverbal object phrase were very long). Indeed, in the following section (Section 7), we show precisely this.

7 Word lengths of the object phrase affects the OV/VO choice with the preference for the efficiency-driven ordering

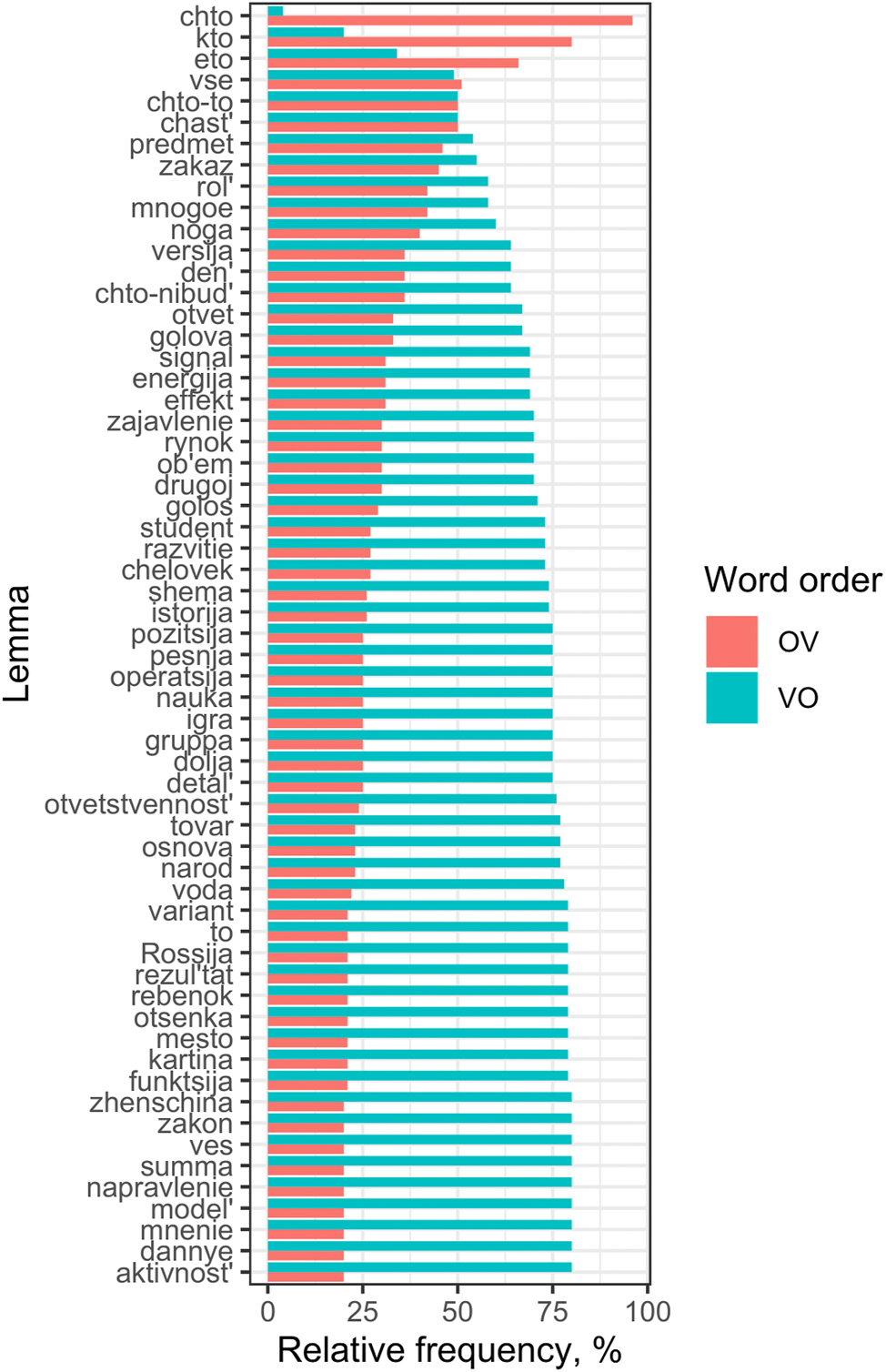

In addition to the effects of accessibility on OV and the general trend towards VO discussed above, there are also lexeme-specific effects on word order preferences. Figure 4 demonstrates the preferences for OV/VO order of frequent objects (>10 times) in Sample2.

Lemma-dependent word order preferences for objects in Sample2. The lemmas were automatically transliterated by our script via automatized transliteration services on the Web. The transliteration therefore does not meet all the standards of scientific transliteration of Russian. The lemmas are sorted according to the relative frequency of their OV order in Sample2. Note that we excluded lemmas with absolute frequencies of less than ten occurrences and the lemmas primarily figuring as relative pronouns which obligatorily occur in OV: kotoryj, čto, and kto.

Figure 4 shows that there is a rather high degree of dispersion: while some of the lemmas almost never occur in preverbal position (e.g., učastie ‘participation’, problema ‘problem’),[10] other lemmas are most frequently found in this position, for example, čto (chto) ‘what’, kto ‘who’, èto ‘this.n’, vsë ‘all.sg’, čto-to ‘something.n’. Such dispersion is not expected on the account that all lemmas generally tend towards VO order. The tendency towards OV for the question words čto (chto) ‘what’ and kto ‘who’ is expected, given that these pronouns normally occur first in the sentence, and we will not discuss them further.

While VO is the generally expected sequence, a closer look at the most frequent OV lemmas shows that they are pronouns (vsë ‘all.sg’ is a pronominally used quantifier, to be more precise) as opposed to nouns (see similar findings in Xolodilova 2013: 74). The question is, what property of pronouns drives these lemmas to the top of OV?

Xolodilova (2013: 48–69) explores this question in detail. The author identifies the following properties that might be responsible for their specific word order behavior (among others): (i) as compared to nouns, pronouns are significantly more frequent in discourse, (ii) they are generally much shorter in coding (often just monophonemic roots [Sitchinava apud Xolodilova 2013: 48]), (iii) mostly standalone (unmodified),[11] (iv) tend towards cliticization, (v) have abstract, indexical semantics, (vi) correlate with animacy, (vii) do not occur as direct objects with verbs like umet’ ‘be skilled in’, moč’ ‘be able to’, perekusit’ ‘have a snack’ (see Chvany 1996).

Pronouns are moreover always fixed for (in)definiteness and, thereby, for accessibility. However, definiteness and accessibility are clearly not the only factors here. First, there is the definite demonstrative to ‘that.n’, which predominantly occurs in VO (see Figure 4). This demonstrative only rarely occurs as a pronoun (e.g., when reinforced with the particle von in von to ‘that one’); mostly it is found as the head of a relative clause with a cataphoric function. This property explains its strong bias for VO, which we discuss in detail below.

Second, among the first three highest-ranked OV pronouns in Figure 4 – èto ‘this.n’, vsë ‘all.sg’ and čto-to ‘something.n’ – the last one is inherently indefinite and its referent is thus low-accessible. Similar evidence is provided by Xolodilova (2013: 75), who found that the indefinite negative polarity pronoun nikogo ‘no one.ACC’ occurs in 90 % of cases in OV order and only in 10 % in VO order. Thus, it is not or not only accessibility that drives the distribution in Figure 4.

There are two inherent properties of pronouns (and pronominally used quantifiers) that provide the clue: these items are generally unmodified and are coded by rather short phonetic strings. Given their shortness – in terms of both phonetic coding and phrase length measured in word tokens – these items are not significant barriers in the recognition of the constituents of the sentence and its structure, wherever in the clause they are placed. More generally, we argue that efficiency pressures that are crucially dependent on the coding length of the argument heavily constrain the word order of Russian. Here, we follow previous research on other efficiency-driven effects in Russian syntax (Berdicevskis et al. 2020; Kravtchenko 2014). We suggest that Hawkins’ Minimize Domain Principle is responsible for OV versus VO placement of particular object types:

| Minimize Domains (Hawkins 2004: 31, 2014: 11) |

| The human processor prefers to minimize the connected sequences of linguistic forms and their conventionally associated syntactic and semantic properties in which relations of combination and/or dependency are processed. The degree of this preference is proportional to the number of relations whose domains can be minimized in competing sequences or structures, and to the extent of the minimization difference in each domain. |

Hawkins (2014: 11) illustrates how Minimize Domains operates in the positioning of PPs in English with the following two examples:

| English |

| The man [VP looked [PP 1 for his son] [PP 2 in the dark and quite derelict building]] |

| The man [VP looked [PP2 in the dark and quite derelict building] [PP1 for his son]] |

The linear order in (11a) minimizes the recognition effort of the syntactic structure by the human processor faster than (11b) under the assumption that the head of a phrase allows the processor to identify the phrase that is coming up next. Thus, the prepositions for and in allow the processor to conclude that a prepositional phrase is coming up. Accordingly, in (11a), the entire structure of the clause, i.e., the subject phrase, the object PP1 and the adverbial PP2, are recognized after the first seven word tokens have been uttered, while 11 word tokens are minimally needed for identifying the entire structure (with both PPs) in (11b). The Minimize Domain Principle makes the processing of syntactic and semantic structure more efficient, as it reduces the amount of working memory load needed to process the entire sentence (Hawkins 2014: 12; see also Futrell et al. 2015; Liu 2020).

We argue that the same principle applies to object ordering in Russian: the preverbal position preferably hosts short object phrases, whereas the postverbal position does not have such a bias (in addition to the overall trend towards VO). This allows for early recognition of the verb (phrase) in Russian according to the Minimize Domain Principle (11). Only short objects in the Russian OV linearization do not significantly impede the recognition of the verb phrase and, crucially, of the structure of the entire utterance, because the decoder does not have to wait too long and store too much content in the working memory before the verbal phrase can be identified. Once the verb has been uttered, a longer object expression may go into production without hindering the recognition of the verbal phrase and thereby of the entire sentence structure, given that the head has already been uttered by the speaker and processed by the hearer.

In Figure 4 and in Table 5 we see that to ‘this.n’ disprefers OV despite its high accessibility and shortness of coding. However, to is mostly used not in its pronominal or demonstrative function but rather as the correlative head of relative clauses (i.e., … to, čto …). More specifically, the reason why to – while definite – strongly prefers the postverbal position is that most of the time it introduces a relative clause as a correlative, as illustrated in (13).

Frequencies of the inherently definite corelative pronoun to ‘this.n’ (Sample2).

| OV | VO |

|---|---|

| 21 % (15) | 79 % (56) |

| …kak | osvoboždajetsja | pisatel’, | voploščaja | to, | čto | gnetet |

| how | free.prs.3sg.rfl | writer.nom.sg | embody.conv | this.n | what | depresses |

| jego… | ||||||

| him | ||||||

| ‘how the writer becomes free, while embodying the (thing), which depresses him’ | ||||||

| From Universal Dependencies (sent_id = 2003Optimizm.xml_48) | ||||||

A relative clause, in turn, dramatically increases the overall length of the object phrase. The Minimize Domain Principle explains why to ‘this.n’ is mostly found in postverbal position despite the overall preference of definite expressions to occur preverbally (Section 4).

The postverbal position, which allows for the early occurrence of the verbal head and thus for the early recognition of the argument structure and thereby of the structure of the entire clause, admits longer object phrases introduced by to (8.1 word tokens on average and maximally 28 word tokens in Sample2). By contrast, the OV position, which postpones the production of the verbal head and thus delays the recognition of the verbal phrase and of the entire clause structure, admits shorter objects (5 word tokens on average and max. 10 word tokens), as illustrated in Figure 5:

Distribution of the lengths of the object phrase headed by to ‘this’ in OV and in VO.

This higher degree of dispersion of object lengths in the postverbal domain than in the preverbal domain is thus motivated by the Minimize Domain Principle as well.

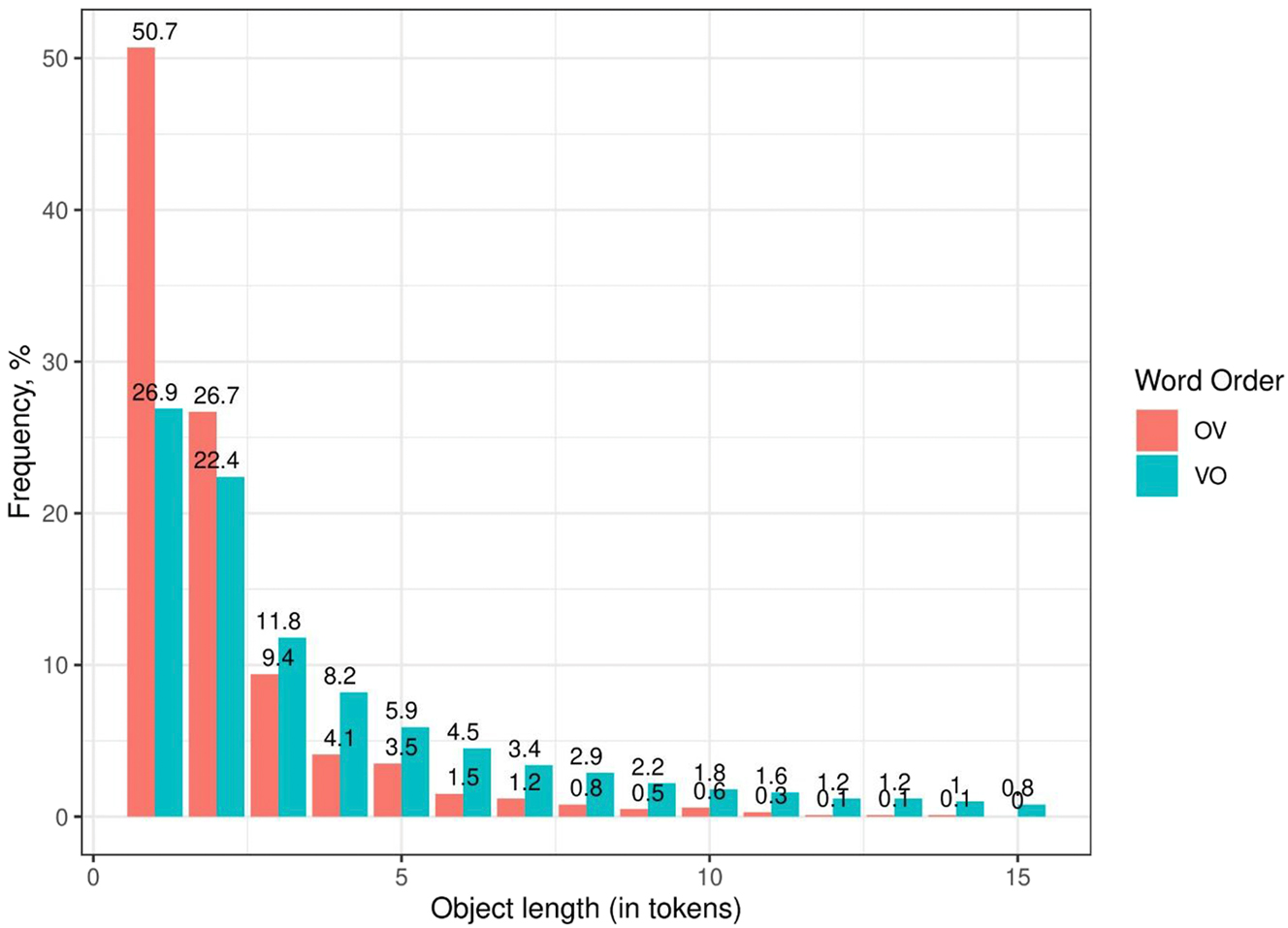

To summarize, a very long object phrase in the preverbal position heavily overloads the working memory of the hearer because their processor would have to wait with the processing of the verbal phrase (part of which the object is) up until the verb has been uttered. This strains working-memory costs in comprehension – cf. the Now-or-Never bottleneck in Christiansen and Chater (2016: 5) – as well as in production. This is the reason why lengthy preverbal objects are highly dispreferred in Russian and the postverbal position of the object is much more efficient here. Figure 6 illustrates the relative frequency of OV and VO of all direct objects depending on their word length.

Word order preferences of objects: frequency of OV/VO given the length in word tokens (Sample2). Note that the objects with the lengths in the range from 1 to 20 cover 98 % of the objects in the sample (N = 12,254). Therefore, we cut extremely long (exceeding 20 words) objects for illustrative purposes (2 %, N = 194).

A reviewer notes that efficiency might play a role in favoring VO with to in another way as well. When to introduces a relative clause as the correlative head, its referent is not accessible yet and the comprehender has to wait until the relative clause has been uttered in order to accommodate the referent. Above we argued that speakers first utter accessible and ready-made items in order to free up their working memory for constructing the pieces of information that are not yet available (accessible). So, the low accessibility is another pressure that is responsible for the VO bias of to that is driven by the strive towards more efficient processing.

Figure 6 shows clearly that – in addition to the overall trend towards VO – there is a decrease of the preference for OV, along with an increase of the length of the object phrase. There are only very few exceptions to this tendency – consider (14).

| Istoriju o tom, kak moj ded po materinskoj linii Nikolaj Sergeevič Norkin byl arestovan i story.acc about dem how my grandfather along mother.adj line pn pn pn was arrested and preprovožden v VČK na Goroxovuju v dekabre 1917 goda, ja mnogo raz slyšal ot nego … brought in VČK in Goroxovaja in december 1917 year 1sg.nom many times hear.pst.sg.m |

| from 3sg.gen |

| [lit.] ‘The story, about how my grandfather on my mother’s side Nikolaj Sergeevič Norkin was arrested and brought in Goroxovaja street in December 1917, I heard many times from himself …’ |

| (From Universal Dependencies, sent_id = 2015iz, predanii.xml) |

Finally, we also observe an interaction between the factor of adjacency to the verb (Section 6) and the length of the object phrase. Figure 7, a jitter plot, illustrates this.

Word order preferences of objects given their length and distance from the verb (viz. adjacency) in Sample2.

First, the plot shows that short objects are the most frequent object type in both positions, and that the most frequent position is immediately next to the verb. Second, objects longer than ten word tokens are increasingly rare in the OV position. Finally, extremely long objects (more than ten word tokens) are more common with VO order, and in this context they tend to occur right next to the verb.

Note that there is also an artificial effect of a correlation between the length of the OV objects with their distance from the verb. The reason for this is technical: the distance of the object phrase from the verb is measured – according to the tagging conventions in the Universal Dependencies Treebank corpus – as the distance between the head of the object phrase and the verb. If the object phrase is modified to the right of the head, as in the following example (15), the distance artificially increases.

| Razmyšlenija | o | svjazi | nalogov | i | tiranii | my |

| thought.acc/nom.pl | about | connection | tax.gen.pl | and | tyranny.gen.sg | 1pl |

| naxodim | i | u | Aristotelja. | |||

| find.1pl | and | at | Aristotle | |||

| ‘We also find thoughts on the connection between taxes and tyranny in Aristotle.’ | ||||||

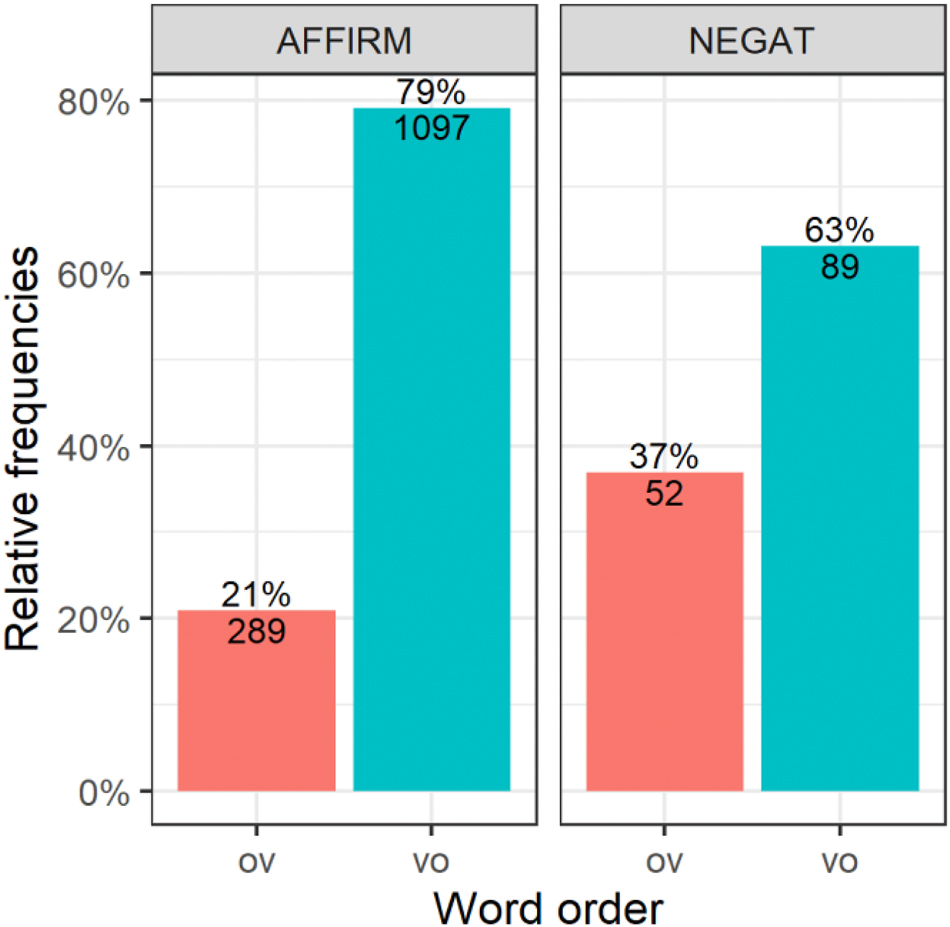

8 Word order and negation

As Figure 8 shows, OV word order is more frequently found in negated clauses (Figure 8) (p < 0.001[12]).

Correlation of VO versus OV word orders with polarity (Sample1).

Negative polarity pronouns such as ničto ‘nothing.n.sg’ occupy the OV positionmost of the time (12 times out of 14 total) in Sample1 (cf. Xolodilova 2013: 75 on the animate nikogo ‘no_one.acc.sg’). However, a statistically significant difference between the negated and the affirmative predicate (Figure 8) remains even if the negative polarity pronouns are not taken into consideration. We only report this effect here and do not offer an explanation, which might be related to the scope of negation over the direct object (cf. Haegeman 1995 for a syntactic explanation).

9 Discriminatory function

In addition to accessibility, word order may potentially be sensitive to the discriminatory function, i.e., to the morphological discrimination between subjects and objects. Comrie (1989) already suggested that the availability of a distinctive object (and/or subject) marking has an impact on the flexibility of the ordering of subjects and objects. At first glance, Table 6 indeed seems to suggest that the presence of a case marker that unequivocally signals the object (ACC or ACC = GEN in Russian) allows for more flexibility in word order than the absence of any morphological distinction between the subject and object (ACC=NOM).

Word order preferences versus DOM (Sample1).

| OV | VO | |

|---|---|---|

| ACC=NOM | 17 % (164) | 83 % (777) |

| ACC = GEN | 29 % (147) | 71 % (357) |

| ACC | 37 % (30) | 63 % (52) |

Moreover, very early on it has been claimed in the literature that the free word order of Russian is also sensitive to the discriminatory function (Comrie 1989; Jasinskaja and Šimík subm.; Sirotinina 1965 [2003]: 4, 95). For example, it has been suggested that the discriminatory function blocks any word order variants in those argument combinations in which both the subject and the object do not morphologically distinguish between nominative and accusative as in (14).

| Mat’ | ljubit | doč’ |

| Mother.nom=acc | love.prs.3sg | daughter.nom=acc |

| (i) ‘The mother loves her daughter.’ | ||

| (ii) ‘It is her mother whom the daughter loves (but not her father).’ | ||

For example, Jakobson (1984: 63) and Jasinskaja and Šimík (subm.) argue that (16) can only have meaning (i) and not meaning (ii) because neither of the nouns differentiates between nominative and accusative, and world knowledge does not help, either. Hence, word order is the only cue allowing the identification of the semantic and syntactic roles.

However, this claim in this form does not hold. First, both meanings (i) and (ii) are possible here, and the claim should be restated in probabilistic terms such that meaning (i) is more frequent and expected, whereas meaning (ii) is more unexpected and needs additional contextual support.

Second, this claim would require the ACC=NOM subtype of objects as doč’ in (16) to be positionally fixed or at least biased for the postverbal position (in order to be identifiable as the object) whereas the ACC≠NOM subtype of objects should enjoy more positional freedom and be less biased towards OV or VO. This is, however, not what we find. If one disregards those factors that, for independent reasons, are known to affect the figures in Table 6, such as negation (Section 8) and animacy (Section 4), the effect of a freer positional distribution of those NP types that morphologically differentiate between subjects and objects disappears. Thus, those NP types with an accusative form that is different from the nominative form are also predominantly animate NPs – mat’ ‘mother’ and doč’ ‘daughter’ in (16) above are very rare exceptions. Animacy was shown above to be one of the factors conditioning the preference for OV. If, however, we exclude animates and focus only on inanimates, the apparent effect of the presence of a higher degree of positional freedom in Table 6 disappears.

We see that indefinite inanimate direct objects do not have more positional freedom when they morphologically differentiate between subjects and objects (12%) than when they do not (15%).

Table 7 shows, however, that genitive-marked direct objects (under negation) are very often found in the OV position. However, the genitive-marked objects (GEN≠ACC) in Sample1 are the direct objects under predicate negation (which optionally allow for the alternation between ACC and GEN with direct objects) as well as a handful of partitive-genitive direct objects (see Seržant 2014, among many others). Yet, as was shown in Section 8 above, negation itself is an important trigger for OV. It is thus highly probable that the higher preference of GEN≠ACC cases for OV is in fact motivated by negation (Section 8) and not by the case itself. Of course, inanimate referents are less likely to yield ambiguity with regard to their syntactic and semantic roles in the sentence. So, our results should additionally be checked by the rare animate nouns with ACC=NOM like ‘mother’ and ‘daughter’ above.

Word order preferences versus DOM, inanimate indefinite NPs only (Sample1).

| OV | VO | |

|---|---|---|

| ACC=NOM | 15 % (51) | 85 % (291) |

| ACC≠NOM | 12 % (8) | 88 % (58) |

| GEN≠ACC | 44 % (22) | 56 % (28) |

To summarize, a morphological distinction between subjects and objects itself does not seem to lead to more positional freedom and thus a higher frequency of OV ordering, as one may be led to assume on the basis of the previous research.

10 Conclusions

Word order in Russian is a complex phenomenon. We identified a set of statistically significant word order preferences of direct objects in Russian. We view different word order patterns as non-hierarchical alternations with distinct probabilities that, in turn, depend on various factors including those summarized below. We suggest that Russian is indeed a free-word-order language (without the usual amendment “so-called”) because its word order preferences result from factors that are not traditionally considered parts of grammar sensu stricto (except for those mentioned above, such as converbial clauses). Instead, we observe effects of online efficiency management in discourse. Possibly some other factors, such as interactional factors, may also have an effect here (unexplored yet). To give an example, the maximal number of words in sentences is never constrained by grammars but rather by a set of interactional and efficiency considerations.

Our focus was on identifying cognitive factors at work via statistical preferences in the corpus. We have claimed that most of these preferences are driven by the pressure for more efficient sentence production and comprehension. Since the word order of Russian is not conventionalized (grammaticalized, syntacticized) for signaling grammatical functions unlike, say, that of French, efficiency pressures appear more pronounced in the former language.

First (Sections 4 and 5), we argued that the pressure towards OV is a function of the degree of accessibility of the object referent, to the effect that a higher level accessibility of the object referent yields a higher preference for the preverbal position, against the overall trend towards VO in Russian. Accessibility is a falsifiable factor in a usage-based approach as taken in the present study. We do not have data tagged for information-packaging roles. Judging from our previous experience as well as the evaluation of such tagging in the field (low inter-annotator agreement, etc., see Cook and Bildhauer 2011; Lüdeling et al. 2014: 609), tagging natural texts for topics and foci is an inherently difficult issue because these roles do not lend themselves to a clear operationalizable method in the situation in which the standard question-answer method is not available (Frajzyngier and Shay 2016: 103; Matić and Wedgwood 2013; Ozerov 2015, 2018, 2021; Tomlin 1995: 517). Impressionistically, it seems that sentence intonation has much more bearing on the pragmatic interpretation of sentences while word order is subject to various constraints imposed by efficient processing and comprehending (on the audience-design accounts).

Russian thus follows the universal trend of languages of the world to place more accessible information prior to informationally new elements (Ariel 1988; Du Bois 1987; Firbas 1992). This strong universal trend has been claimed to be rooted in the incremental nature of human speech production and in the limited processing resources of humans such as storage limitations of the human working memory (see Jaeger and Norcliffe 2009: 869–870 for an overview), whose estimated capacity is approx. a 3-second window of speech (see Pöppel 2009; Wittmann 2011). Overloading the working memory with the pre-planned material is known to be dispreferred for many reasons (cf. the Now-or-Never bottleneck in Christiansen and Chater 2016: 5; see neurolinguistic evidence in Swaab et al. 2003). Therefore, ready-made information chunks are immediately passed on to the articulatory system in order to free up production resources for the upcoming information. This is also why early articulated objects (OV) may have a longer distance to the verb than less accessible objects in the postverbal position, as we showed in Section 6.

Secondly, another factor that affects the linear position of the direct object is its length. In Section 7, we found that – in accordance with Hawkins’ Minimize Domain Principle (2014) – the preverbal position prefers shorter object phrases while the postverbal position does not have such a bias and easily hosts long direct objects (e.g., containing relative clauses). The Minimize Domain Principle makes sure that the production and comprehension costs are kept minimal and thus efficient (see comparable evidence from Dutch or German listed in Jaeger and Norcliffe 2009: 875).

Thirdly, we have shown that negation has an impact on OV in Section 8. We hypothesized that this effect might be related to issues of scope, which can be linked to the linear position. However, we did not explore this effect any further.

Fourthly, in Section 9, we obtained a null result, finding that the discriminatory function does not have an effect on word order of Russian and, contrary to previous claims, nouns not distinguishing between subjects and objects morphologically are not associated with more rigid word order, despite the formal ambiguity.

Finally, impressionistically, after checking the first few hundred examples in Sample1, we did not observe any significant effect of main versus subordinate clauses on the word order of Russian, except for object relative and converbial clauses, where the position of the object follows fixed constraints.

The factors we explore above are not entirely independent from one another. For example, as a reviewer pointed out, accessibility is related to length and adjacency. However, in contrast to the type-based approach on accessibility in Ariel (1988) (full NP vs. pronoun vs. clitic pronoun), our approach to length operates with gradual values. In contrast to Ariel’s approach, we can predict that, for example, a 50-word-tokens-long object is more likely to occur postverbally than one that is 20 word tokens long, although the degree of accessibility of these objects will largely be the same.

We primarily focused on cognitive factors affecting the word order choices of Russian speakers and we did not discuss or explore interactional and more broadly discourse and situation-related factors (inter alia, Du Bois 2014; Selting and Couper-Kuhlen 2000; Verhagen 2005) at all. These are often taken too narrowly to be only about the information-packaging roles of topic (and comment) and focus (and background). We suggested that there is no evidence showing that the information-packaging roles of topic and focus are directly linked with OV and VO positions in Russian once the effects of accessibility are controlled for. Moreover, information-packaging roles are both cross-linguistically and methodologically disputed and might not be suitable for making falsifiable, usage-based claims.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank cordially prof. Pavel Ozerov for his invaluable comments. Likewise, we thank the anonymous reviewers and the editors for their work: the paper considerably improved thanks to their comments and careful reading. This research has been funded with the support of the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG, German Research Foundation) – Project-ID 317633480 – SFB 1287 and Project-ID 498343796.

-

Data availability: The data and scripts used for this study are available at https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.13955552.

References

Adamec, Přemysl. 1966. Porjadok slov v sovremennom russkom jazyke [Word order in Modern Russian]. Prague: Academia.Suche in Google Scholar

Aissen, Judith. 2003. Differential object marking: Iconicity vs. economy. Natural Language and Linguistic Theory 21(3). 435–483. https://doi.org/10.1023/a:1024109008573.10.1023/A:1024109008573Suche in Google Scholar

Anttila, Arto, Matthew Adams & Michael Speriosu. 2010. The role of prosody in the English dative alternation. Language and Cognitive Processes 25. 946–981. https://doi.org/10.1080/01690960903525481.Suche in Google Scholar

Ariel, Mira. 1988. Referring and accessibility. Journal of Linguistics 24. 65–87. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0022226700011567.Suche in Google Scholar

Ariel, Mira. 2000. The development of person agreement markers: From pronouns to higher accessibility markers. In Michael Barlow & Suzanne Kemmer (eds.), Usage-based models of language, 197–260. Stanford, CA: CSLI Publications.Suche in Google Scholar

Ariel, Mira. 2014 [1990]. Accessing noun phrase antecedents. New York: Routledge.Suche in Google Scholar

Babyonyshev, Maria. 1996. Structural connections in syntax and processing: Studies in Russian and Japanese. Cambridge, MA: MIT PhD dissertation.Suche in Google Scholar

Bailyn, John F. 2003. A (purely) derivational approach to Russian free word order. In Wayles Browne, Ji-Yung Kim, Barbara Partee & Robert Rothstein (eds.), Formal Approaches to Slavic Linguistics (FASL) 11: The Amherst Meeting 2002. Ann Arbor, MI: Michigan Slavic Publications.Suche in Google Scholar

Bailyn, John F. 2012. The syntax of Russian. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.Suche in Google Scholar

Bates, Douglas, Martin Mächler, Benjamin Bolker & Steven Walker. 2015. Fitting linear mixed-effects models using lme4. Journal of Statistical Software 67(1). 1–48. https://doi.org/10.18637/jss.v067.i01.Suche in Google Scholar

Berdicevskis, Aleksandrs, Karsten Schmidtke-Bode & Ilja A. Seržant. 2020. Subjects tend to be coded only once: Corpus-based and grammar-based evidence for an efficiency-driven trade-off. In Proceedings of the 19th International Workshop on Treebanks and Linguistic Theories, 79–92.10.18653/v1/2020.tlt-1.8Suche in Google Scholar

Biskup, Petr. 2011. Adverbials and the phase model. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.10.1075/la.177Suche in Google Scholar

Bivon, Roy. 1971. Element order (Studies in the Modern Russian Language 7). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.Suche in Google Scholar

Błaszczak, Joanna. 2001. Investigation into the interaction between the indefinites and negation. Berlin: Akademie Verlag.10.1515/9783050080093Suche in Google Scholar

Błaszczak, Joanna. 2005. On the nature of n-words in Polish. Journal of Slavic Linguistics 13(2). 73–235.Suche in Google Scholar

Bresnan, Joan, Anna Cueni, Tatiana Nikitina & R. Harald Baayen. 2007. Predicting the dative alternation. In Gerlof Bouma, Irene Krämer & Joost Zwarts (eds.), Cognitive foundations of interpretation, 69–94. Amsterdam: Edita – The Publishing House of the Royal Netherlands Academy.Suche in Google Scholar

Chafe, Wallace. 1994. Discourse, consciousness, and time. Chicago & London: University of Chicago Press.Suche in Google Scholar

Christiansen, Morten H. & Nick Chater. 2016. The now-or-never bottleneck: A fundamental constraint on language. Behavioral and Brain Sciences 39. e62. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0140525x1500031x.Suche in Google Scholar

Chvany, Catherine V. 1996. A continuum of lexical transitivity: Slightly-transitive verbs. In Olga T. Yokoyama & Emily Kleinin (eds.), Selected essays of Catherine V. Chvany, 161–168. Columbus, OH: Slavica.Suche in Google Scholar

Comrie, Bernard. 1978. Ergativity. In Winfred P. Lehmann (ed.), Syntactic typology: Studies in the phenomenology of language, 329–394. Austin: University of Texas Press.Suche in Google Scholar

Comrie, Bernard. 1981. Language universals and linguistic typology: Syntax and morphology. Oxford: Basil Blackwell.Suche in Google Scholar

Comrie, Bernard. 1989. Language universals and linguistic typology: Syntax and morphology, 2nd edn. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.Suche in Google Scholar

Cook, Philippa & Felix Bildhauer. 2011. Annotating information structure: The case of “topic”. In Stefanie Dipper & Heike Zinsmeister (eds.), Beyond semantics: Corpus-based investigations of pragmatic and discourse phenomena. Proceedings of the DGfS Workshop Göttingen, February 23–25 (Bochumer Linguistische Arbeitsberichte 3), 45–56. Bochum: University of Bochum.Suche in Google Scholar