Abstract

Friction stir welded (FSWed) joints of aluminum alloys exhibited a hardness drop in both the advancing side (AS) and retreating side (RS) of the thermo-mechanically affected zone (TMAZ) due to the thermal cycle involved in the FSW process. In this investigation, an attempt has been made to overcome this problem by post weld heat treatment (PWHT) methods. FSW butt (FSWB) joints of Al-Cu (AA2014-T6) alloy were PWHT by two methods such as simple artificial aging (AA) and solution treatment followed by artificial aging (STA). Of these two treatments, STA was found to be more beneficial than the simple aging treatment to improve the tensile properties of the FSW joints of AA2014 aluminum alloy.

1 Introduction

It is well known that the high strength aluminum alloys (2xxx series) have been widely applied in aircraft structures such as in fuselages, fins and wings [1], which are very difficult to weld by conventional fusion welding techniques. As is seen from the chemical composition and melting point difference between the oxide layer and bare metal this can result in hot cracking, alloy segregation, partially melted zone, porosity, etc. [2], [3]. Friction stir welding (FSW) is a solid state welding process in which metals do not melt and recast during FSW, which proves it is suitable for producing better quality joints compared to the fusion welding process. FSW was invented by The Welding Institute (TWI) in 1991 [4]. It has been effectively used in the joining of aluminum alloys particularly age- and precipitation-hardenable aluminum alloys (2xxx series) [5]. Nevertheless, many studies have reported on the mechanical properties of FSW joints which indicated that elongation of the as-welded joints are only 20%–40% those of the base metal (BM), for the heterogeneous microstructure across the weld cross-section [6], [7]. Similarly, a soft region observed in the heat affected zone (HAZ) either on advancing side (AS) or retreating side (RS), which is attributed to be due to the coarsening of precipitates by over aging during FSW, as it results in the degradation of joint strength.

In order to improve the mechanical properties of the FSWed joints, the post weld heat treatment (PWHT) method has been attempted by many investigators. Malard et al. [8] investigated the effect of PWHT on microstructural distribution in an AA2050-T34 fiction stir welded joints. The as-weld (AW) joint microstructure was dominated by the solute clusters while very little precipitation took place during FSW. During PWHT, the kinetics of precipitates in all the region were mainly controlled by the local dislocation density inherited from the welding and the amount of solute available for precipitation. Zhang et al. [9] who investigated the effect of aging and water cooling on FSWed joints of AA2219-T6 aluminum alloy, reported that the water cooling did not enhance the microhardness of the soft region but caused a slight improvement in tensile strength. Whereas in PWHT, aging improves the hardness of the soft region and tensile strength of 2214Al-T6 joints. Liu et al. [10] used two types of heat treatment, aging and solutionizing treatment followed by water quenching and aging, and reported the solution which was followed by water quenching and artificial aging (AA) treated joints produced abnormal grain growth (AGG) in the stir zone (SZ) and an increase the microhardness, whereas the AA samples showed lower hardness due to equilibrium precipitates and no re-precipitates. Chen et al. [11] investigated the effect of PWHT on the mechanical properties of 2219-O FSWed joints, and reported the fracture location of the PWHT sample had been changed to a weld zone (WZ). Safarkhanian et al. [12] analyzed the effect of AGG on the tensile strength of FSWed joints of the Al-Cu-Mg alloy. They concluded that AGG occurred during PWHT and it improved the tensile and elongation of the joint. On the other hand, the stable grains in the SZ had no effect on the mechanical properties.

Wang et al. [13] found two soft zones located at the AS and RS of the HAZ in the as-welded (AW) condition. Due to single low temperature aging treatment (LTA), the soft region close to the BM in the HAZ almost vanished. Sivaraj et al. [14] reported that the STA was beneficial in regaining the tensile properties of the joint compared to the AW, and AA treatments. Aydin et al. [15] investigated the effect of PWHT on the microstructure and mechanical properties of FSWed joints of AA2024 aluminum alloy. The PWHT procedure caused abnormal coarsening of the grains in the SZ, which resulted in a drop in microhardness at the SZ compared to the BM. The aging treatment was found to be more beneficial than other heat treatments. Zhilihu et al. [16] found that fine equiaxed grains were stable and were retained in the nugget of the weld, and the grain in the TMAZ became coarse and equiaxed as the annealing temperature increased. They also observed that the plastic deformation behavior of the nugget and base material were high. Rui-dong fu et al. [17] used two heat input conditions and concluded that under higher welding heat input conditions, the hardness of the SZ was lower than the BM. Under low welding heat input conditions, the hardness of the SZ was high, depending upon the tool rotational speed and they observed that the increase in tool rotational speed increased in the hardness of SZ. Sharma et al. [18] investigated the effect of PWHT on the microstructure and mechanical properties of friction stir welded (FSWed) AA7039 aluminum alloy. They reported that the applied PWHT increased the size of α grains in all the regions of FSWed joints. AGG was observed in entire region modified by FSW in the case of solution treatment with or without aging. Sree Sabari et al. [19] investigated the effect of PWHT on the tensile properties of FSWed AA2519-T87 aluminum alloy joints, they found that the STA treatment was beneficial in enhancing the tensile strength of the FSWed joints of AA2519-T87 alloy, which was mainly due to the presence of fine and densely distributed precipitates in the SZ.

From the literature review, it is understood that a lot of research [8], [9], [10], [11], [12], [13], [14], [15], [16], [17], [18], [19] was carried out focusing on the effect of PWHT on the FSW butt (FSWB) joints of 2xxx series of aluminum alloys such as AA2024, AA2214, AA2050 and AA2519, etc. But there are no studies reported on the effect of PWHT on the mechanical properties of FSWB joints of AA2014-T6 aluminum alloy. Hence, in this investigation, an attempt has been made to investigate the outcome of PWHT such as AA and solution treatment + artificial aging (STA) on the microstructure and tensile properties of the FSWB joints of AA2014-T6 aluminum alloy.

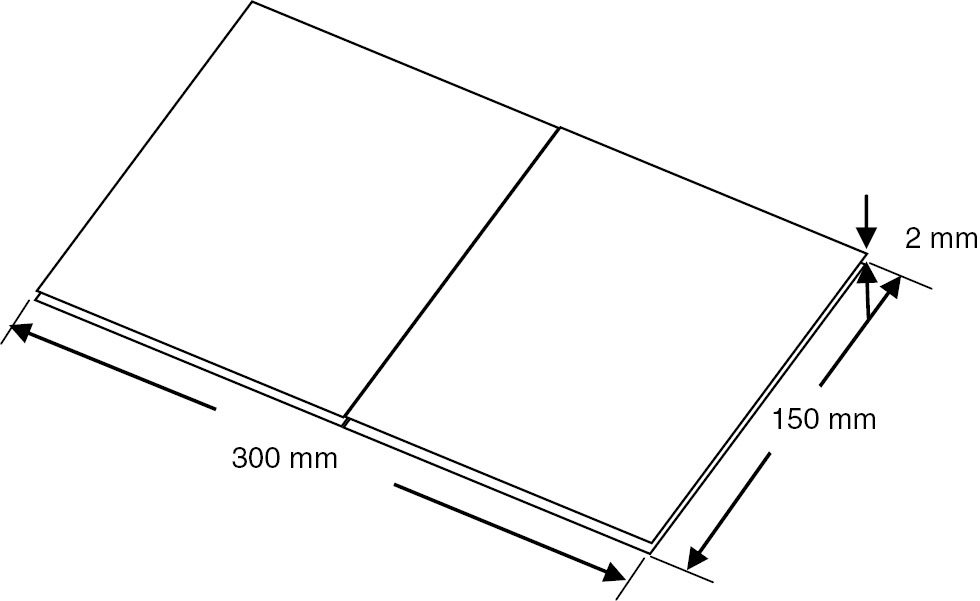

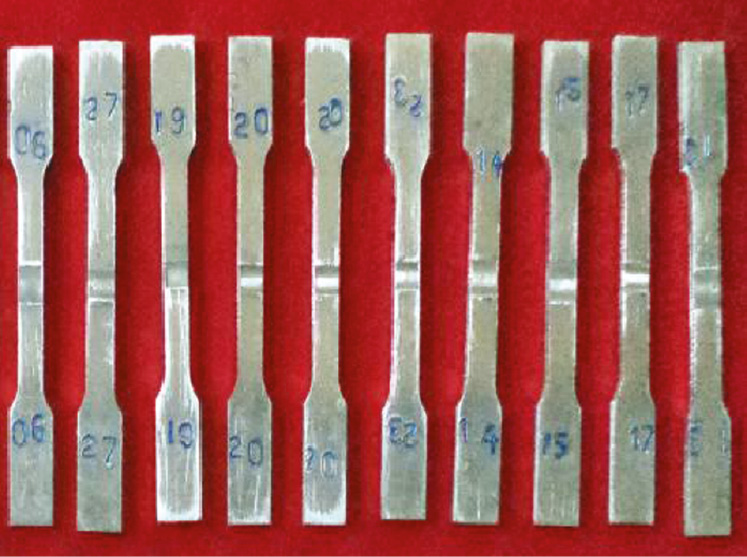

2 Experimental

Rolled sheets of 2 mm thick AA2014-T6 aluminum alloy were used as the parent metal (PM) in this investigation, and the chemical composition and mechanical properties of PM are presented in Tables 1 and 2, respectively. The sheets were cut into 300 mm×150 mm pieces and firmly clamped to achieve a square butt joint configuration (Figure 1). The joints were fabricated using a computer numerical controlled FSW machine, normal to the rolling direction of the sheet. A super HSS tool with dimensions shown in Figures 2 and 3 was used to fabricate the joints. Optimized FSW parameters were used for the fabrication of the joints (Table 3). They are tool rotational speed of 1500 rpm, welding speed of 50 mm/min, tool tilt angle of 2° and shoulder diameter of 7 mm. Figure 4 shows a photograph of the FSWB joints. To study the effect of PWHT on tensile strength of the joints, the welded joints were subjected to two different PWHT, namely AA and STA. The AA treatment was carried out at 170°C for a holding time of 10 h and STA treatment was carried out by solutionizing at 500°C for a soaking period of 1 h followed by cold water quenching. The tensile specimens were prepared as per the ASTM-E8-M04, and tensile test was carried out using a 100 kN electromechanical controlled universal testing machine at a cross head velocity of 1.5 mm/min. Figures 5 and 6 show the photograph of tensile specimens before and after testing. To analyze the effect of PWHT on microstructural characteristics, the specimens were cut across the cross section of the joints. The specimens were prepared by standard metallographic technique and were etched with Keller’s reagent, to reveal the grain size of the different WZ. The microstructural analysis was done using an optical microscope (OM) and the fracture surfaces of the tensile tested specimens were analyzed using a scanning electron microscope (SEM). The hardness was measured across the weld center line on top sheet by Vickers microhardness tested with a load of 0.5 kg and dwell time of 15 s. Transmission electron microscope (TEM) was employed to analyze the distribution of precipitates and the dislocation cell structure evolved in the SZ of the joint.

Chemical composition (wt.%) of parent metal.

| Si | Fe | Cu | Mn | Mg | Zn | Cr | Ti | Al |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.83 | 0.201 | 4.103 | 0.713 | 0.558 | 0.16 | 0.004 | 0.013 | Bal |

Mechanical properties of parent metal.

| 0.2% Yield strength (MPa) | Ultimate tensile strength (MPa) | Elongation in 50 mm gauge length (%) | Vickers microhardness (0.5 N, 15 s) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 433 | 461 | 8 | 154 |

Schematic diagram of FSW joint configuration.

Schematic diagram of FSW tool.

Photograph of fabricated FSW tool.

Photograph of fabricated FSW joint.

FSW parameters.

| Tool geometry | Process parameters | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tool shoulder | Pin | ||||||

| Type | Tool shoulder diameter (mm) | Major diameter (mm) | Minor diameter (mm) | Length (mm) | Tool rotational speed (rpm) | Welding speed (mm/min) | Tool tilt angle (°) |

| Concave | 7 | 2 | 1.5 | 1.5 | 1500 | 50 | 1.5 |

3 Results

3.1 Tensile properties

The tensile properties and hardness distribution of FSWed joints in AW, AA and STA conditions are presented in Table 4. In each condition, three specimens were tested and the average value is presented in Table 4. The PM showed tensile strength of 461 MPa. AW joint exhibited lower tensile strength (380 MPa) compared to the PM. The AA joint showed a tensile strength of 393 MPa, an increase of 4% compared to the AW joint. The STA joint yielded a tensile strength of 407 MPa, an enhancement of 7% compared to the AW joint.

Tensile and hardness test results.

| Sl. no | Joint condition | 0.2% yield strength (MPa) | Elongation in 50 mm gauge length (%) | Ultimate tensile strength (MPa) | Microhardness (Hv) at 0.5 N, 15 s | Fracture location | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SZ | TMAZ | HAZ | ||||||

| 1 | AW Joint | 305 | 4 | 380 | 124 | 106 | 108 | HAZ |

| 2 | AA Joint | 315 | 5.5 | 393 | 128 | 109 | 111 | SZ/TMAZ |

| 3 | STA Joint | 326 | 6 | 407 | 135 | 118 | 122 | SZ/TMAZ |

| 4 | Parent metal | 433 | 8 | 461 | 155 | |||

Photograph of fabricated tensile specimen (before testing).

Photograph of fabricated FSW joint (after testing).

3.2 Microhardness

The hardness measurement was carried out across the weld cross section on the mid thickness of the joint using a Vickers microhardness testing machine. The hardness profiles of AW, AA and STA joints are shown in Figure 7. The SZ of AW joint shows considerably lower hardness (124 Hv) compared to the hardness of PM (155 Hv). The hardness of the AW joint shows a drop in the TMAZ region on both sides of the joint. Nevertheless, the lowest hardness distribution region (soft part) in AW joint was observed at RS-TMAZ (106 Hv). The AA treatment resulted in an increase in hardness in the SZ. The STA joint recorded the highest hardness in all the regions of the joint compared to AW and AA joints.

Microhardness profile across the cross section of the weld.

3.3 Microstructure

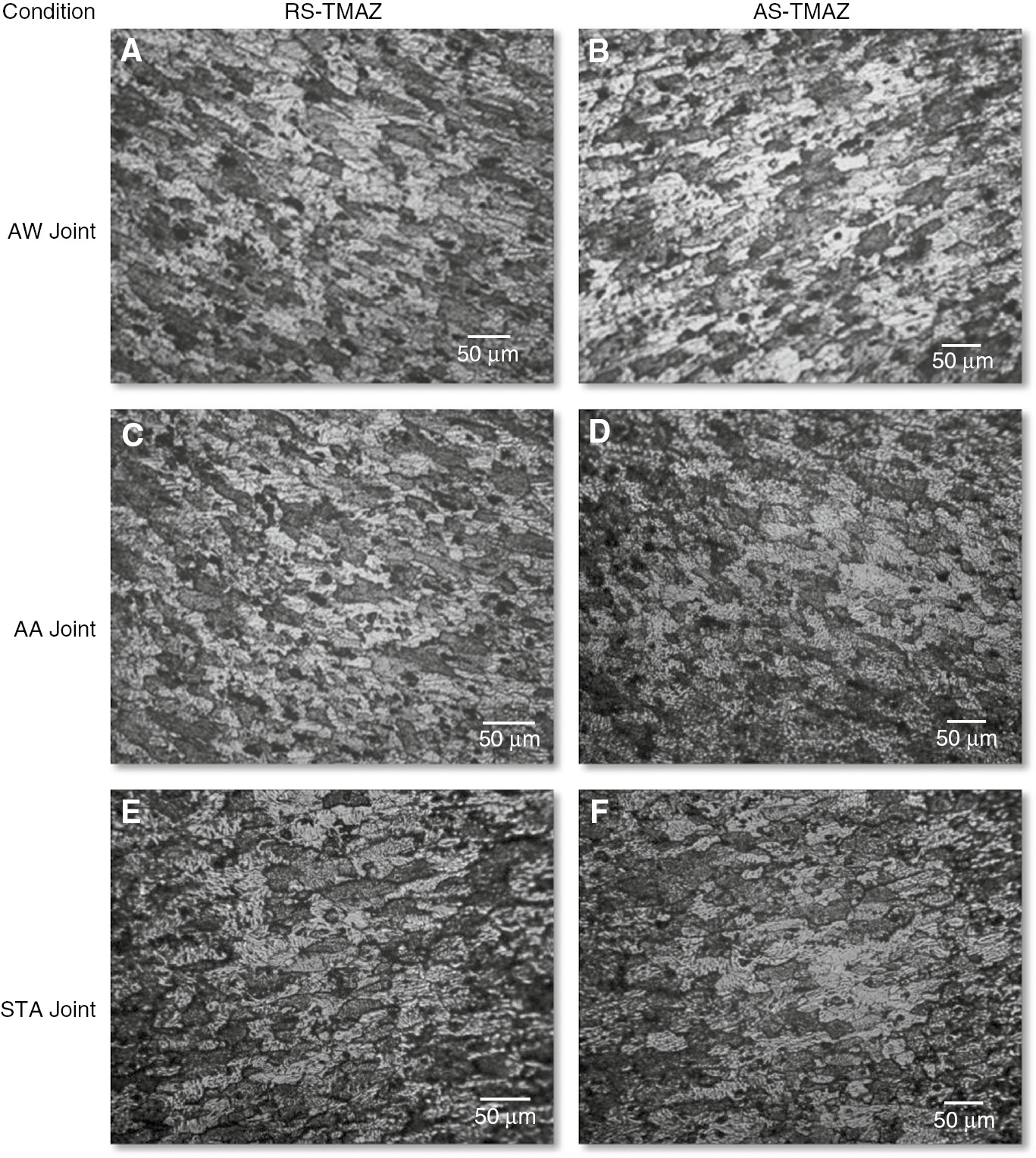

Figure 8 shows the optical micrograph of the PM and SZ of AW, AA and STA joints. The PM is composed of coarse and elongated grains with an average grain size of 30 μm. The SZ region of the AW joint (Figure 8B) consists of fine and equiaxed grains due to severe plastic deformation followed by dynamic recrystallization (DRX) that occurred during the FSW process. The SZ of AA joint (Figure 8C) reveals no change in the size of fine equiaxed grains, when subjected to the AA treatment. The SZ of STA joint (Figure 8D) reveals the marginal increase in grain size due to solutionizing followed by aging treatment. The optical micrographs of RS-TMAZ and AS-TMAZ in AW conditions are presented in Figure 9A and B, respectively. RS-TMAZ and AS-TMAZ reveal the extremely slanted and elongated grains due to the stress imparted by the tool in this region during FSW process. The optical micrographs of RS-TMAZ and AS-TMAZ in AA joint are shown in Figure 9C and D, respectively. The AS-TMAZ and RS TMAZ regions show no alteration in the grain size due to the AA treatment. The optical micrographs of RS-TMAZ and AS-TMAZ in STA joints are shown in Figure 9E and F, respectively. AS-TMAZ and RS-TMAZ show the partially strengthened conditions of the highly deformed matrix, which might be the finer precipitates precipitated during the STA treatment in the region [13].

Optical micrograph of stir zone of (A) PM, (B) AW, (C) AA, (D) STA joints.

Optical micrograph of AW (A) RS-TMAZ, (B) AS-TMAZ, AA (C) RS-TMAZ, (D) AS-TMAZ, and STA (E) RS-TMAZ, (F) AS-TMAZ.

TEM micrograph of PM (shown in Figure 10A) reveals two types of precipitates (coarse and fine). The coarse precipitates vary in size from 50 to 100 nm while the fine precipitates vary from 10 to 50 nm in size. TEM of the AW joint SZ (Figure 10B) reveals precipitates with fine needle like and spherical morphology. The finer Al2Cu and Al2CuMg precipitates in the SZ completely dissolved in the matrix due to friction heat during the FSW cycle [20]. SZ of the AA joint (Figure 10C) reveals agglomerated precipitates varying in size from 100 to 200 nm. SZ of the STA joint (Figure 10D) shows the dissolution of all the agglomerated coarse precipitates in the matrix except for few coarse precipitates. Figure 11 shows the SEM images of AW, AA and STA joints, there are two different particle marked a and b, the energy dispersive spectroscopy (EDS) analysis indicated that these particles are compound of Al-Cu-Mg and Al-Cu-Fe-Mn, according to the literature these particles are mostly likely Al2Cu Mg and (Cu, Fe, Mn) Al6 or Al7Cu2Fe.

TEM micrograph of (A) PM, (B) AW, (C) AA and (D) STA joint.

SEM images: (A) AW joint, (B) AA joint, (C) STA joint, (D) EDS spectrum of the a particle, (E) EDS spectrum of b particle.

3.4 Fractographs

Table 5 shows the fracture location of the FSWed joints. An analysis of the fracture surface of the tensile specimen can provide useful information pertaining to the role and contribution of the characteristic microstructural features to the mechanical properties of the joint [6], [21]. Figure 12 shows the fracture surface of the tensile tested samples treated by AW, AA and STA joint. The fracture surfaces of the tensile tested joints are characterized by the SEM, taken from the midpoint of the fracture area. The fracture surface of the AW joint is predominantly transgranular and shown in Figure 12B. It is characterized by an array of fine microscopic crack and population of voids of varying size and shape are distributed through the fracture region, cracked second phase particle and shallow dimples are found covering the transgranular fracture region. The mode of failure was ductile as evident from the dimpled fracture surface.

Fracture location of FSW joints.

| Sl. no | Joint condition | Fractured specimens | Fracture location |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | AW joint |  | HAZ |

| 2 | AA joint |  | SZ/TMAZ |

| 3 | STA joint |  | SZ/TMAZ |

SEM-fractographs of (A) PM, (B) AW, (C) AA, (D) STA joint.

4 Discussion

From the experimental results, it can be understood that the PWHT had a significant effect on the tensile strength and microstructural characteristics of FSWB joints of AA2014 aluminum alloy, and the following inferences can be obtained: (a) AA and STA treatment coarsened the α aluminum grains in all the regions of joints resulted in large size α aluminum grains, the grain growth appears to be natural consequence of heat treatment [22], (b) the size and distribution of strengthening precipitates were different in all PWHT joints, (c) the size and distribution of strengthening precipitates in the STA treated joints were uniform than other joints. This may be the reason for higher hardness and superior tensile strength of STA joints. The AGG in all the regions in FSW joints which may be attributed inhomogeneous plastic deformation during FSW and the following factors lead to AGG: (1) anisotropy in grain boundary and mobility, (2) reduction of pinning force due to dissolution of strengthening precipitates, (3) thermal dynamic forces driving AGG. A critical aspect to consider is the balance between thermodynamic driving forces and pinning driving forces that impede grain boundary immigration [23]. The solution temperature is another important factor to control the stability of the grains in the FSWed joints. The increase in solution temperature resulted in increases of grain growth [24]. In this study, solution treatment was carried out at 500°C and 1-h soaking period.

Figure 7 shows the hardness distribution of the FSWB joints before and after PWHT. The hardness distribution of the FSW joints depends greatly on the precipitates size and distribution [25]. The microhardness of the AW joint show a general low hardness distribution region (LHDR) on both the AS and RS. The reason for LHDR in the FSW joint is coarsening and over aging of strengthening precipitates due to the thermal cycle during FSW. The SZ was solutionized owing to a high thermal cycle (420°C–480°C) [26], [27] which resulted in the dissolution of Al2Cu precipitates. This may be the reason for the low hardness of the joint in AW condition. As seen the hardness of the SZ, thermo-mechanically affected zone (TMAZ) of AW joint exhibited lower hardness than the PM (155 Hv). The reason for low hardness in the HAZ may be attributed due to the HAZ has been experienced at more than 250°C in the FSW. Which is modifying the precipitate size and distribution but retain the same grain size of PM [27]. The AA and STA joints exhibited higher hardness in the SZ, TMAZ and HAZ, which may be attributed to the increase of volume fraction of dissolved precipitates that increased the content of the alloying element for precipitation hardening during aging [28]. Hence, the fully PWHT after FSW can improve the microhardness of the soft region (TMAZ).

The mechanical properties of FSW joints of the precipitation hardening aluminum alloy depend on the distribution and size of precipitates rather than grain size [29]. The most efficient method for precipitation of precipitates occurs in the aging treatment, this leads to improve the strength compared to the AW joint. In contrast, AA treated joints have very coarse precipitates. Hence, the lowest microhardness was observed in the weld region and strength when compared to the STA joint. The precipitation hardening aluminum alloy (2xxx) in the T6 state contains fine needle-like and spherical-shaped Al2Cu, Al2CuMg precipitates with an average size of 100 nm. The precipitates become coarse or dissolve during the FSW cycle. This result, reduces the strength of the joint. Table 4 shows the mechanical properties of the PM, and FSW joints before and after PWHT. As seen the tensile and elongation of the AW joint are about 380 MPa, 4% and 20%, 50% lower than the PM, respectively. The PWHT can improve the strength and ductility of the FSW joints, AA joints observed the tensile strength and elongation of 393 MPa and 5.5%, respectively. Moreover, the FSWed joint in the STA condition offered higher strength and lower elongation than AW and AA treated joints. From the tensile test results, the mechanical properties have been increased by the PWHT only in STA treatment. The reason for superior tensile strength in the STA joint is AGG. The AGG is a microstructural change in which some grains growth abnormally at the expense of fine matrix grains and it generally happens when the normal grain growth stopped [30]. The presence of AGG in the SZ has a significant effect on the tensile strength of FSW joints after PWHT. This might produced different microstructures in the SZ before and after PWHT.

TEM micrograph of the SZ treated by the AA shows that precipitate coarsening by agglomeration, the results of coarsening and the reduction in dislocation density, the hardness in the TMAZ decreased and width of the soft region increased compared with the AW joint. The joint treated with the solution treatment and followed by aging yielded higher tensile strength compared with the AW and AA joint. The width of the soft region in TMAZ was reduced and moved towards the center of the weld, because the AA process in the STA treatment caused the dissolution of precipitates in the aluminum matrix, the AA process in the STA treatment caused precipitation of fine θ′ precipitates.

From the results, the joint strength was considerably increased by AA, STA treatment of the two PWHT, the STA joint offered better strength (407 MPa) compared to the AW and AA joints. In general, during the tensile test the fracture of the FSW joint took place from the soft region (LHDR) of the joints. The location of LHDR is found to vary from HAZ, SZ/TMAZ interface depending upon the condition of the joints. The AW joint, fractured from HAZ (108 Hv) on the AS and the fracture location of the AA and STA joints was observed at the SZ/TMAZ interface on the AS. The AA joint fracture surface exhibited with deeper and larger dimples (Figure 12C). Similar behavior was also observed in the STA joint (Figure 12D), which exhibited elongated dimple surface, these elongated dimples suggested shearing of the dimples, during tensile testing and the fracture mode was ductile. The size of the dimples in the AA, STA joints is large, it could be indicative that large stretch zone is present at the tip of the crack, and resulted large plastic zone ahead of the crack [24].

5 Conclusions

The tensile strength of FSWB joints of AA2014-T6 aluminum alloy was lower because of precipitates dissolution due to thermal cycle involved FSW process.

The AA treatment (170°C, 10 h) applied in this investigation yielded 4% improvement in the tensile strength of FSWB joints of AA2014-T6 aluminum alloy.

The STA cycle (500°C, for 1 h, 170°C for 10 h) is found to be more beneficial to increase the tensile strength of FSWB joints of AA2014 aluminum alloy, and enhancement is approximately 7%.

STA joint yielded higher tensile strength than other joints due to the dissolution of all the agglomerated coarse precipitates (during AA) in the matrix except for few coarse precipitates. The AA process in the STA treatment caused re-precipitation of fine θ′ precipitates.

The AGG has significant effect on the tensile strength of FSWB joints of AA2014-T6 aluminum alloy.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge the financial support from the Aeronautical Development Agency (ADA), Bangalore, through a R&D project no: FSED 83.07.03 to carry out this project work.

References

[1] Heinz A, Hasler A, Keidel C, Moldenhauer S, Benedictus R, Miller WS. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2000, 280, 102–107.10.1016/S0921-5093(99)00674-7Suche in Google Scholar

[2] Genevosis C, Deschamps A, Denquin A, Doisneau-coottignies B. Acta Mater. 2005, 53, 2447–2458.10.1016/j.actamat.2005.02.007Suche in Google Scholar

[3] Mishra RS, Ma ZY. Mater Sci. Eng. R 2005;50, 1–78.10.1016/j.mser.2005.07.001Suche in Google Scholar

[4] Thomas WM, Nicholas ED, Needham JC, Murch MG, Temple Smith P, Dawes CJ. International patent application GB9125978.8.6. 1991.Suche in Google Scholar

[5] Nandan R, Debroy T, Bhadseshia HKDH. Prog. Mater. Sci. 2008, 53, 980–1023.10.1016/j.pmatsci.2008.05.001Suche in Google Scholar

[6] Srivatsan TS, Vasudevan S, Park L. Mater. Sci. 2007, 456, 235–245.Suche in Google Scholar

[7] Xu WF, Liu JH, Luan GH, Dong CL. Mater. Design 2009, 30, 3460–3467.10.1016/j.matdes.2009.03.018Suche in Google Scholar

[8] Malard B, De Geuser F, Deschamps A. Acta. Mate. 2015, 101, 90–100.10.1016/j.actamat.2015.08.068Suche in Google Scholar

[9] Zhang Z, Xiao BL, Ma ZY. Mater. Char. 2015, 106, 255–265.10.1016/j.matchar.2015.06.003Suche in Google Scholar

[10] Liu HJ, Zhang HJ, Yu L. Mater. Design 2011, 32, 1548–1553.10.1016/j.matdes.2010.09.032Suche in Google Scholar

[11] Chen YC, Liu HJ, Feng JC. J. Mater. Sci. 2005, 40, 4657–4659.10.1007/s10853-005-4085-ySuche in Google Scholar

[12] Safarkhanian A, Goodarzi M, Boutorabi MA. J. Mater. Sci. 2009, 44, 5452–5458.10.1007/s10853-009-3735-xSuche in Google Scholar

[13] Wang J, Fu R, Li Y, Zang J. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2014, 609, 147–153.10.1016/j.msea.2014.04.077Suche in Google Scholar

[14] Sivaraj P, Kanagaraj D, Balasubramanian V. Def. Tech. 2014, 10, 1–8.10.1016/j.dt.2014.01.004Suche in Google Scholar

[15] Aydin H, Bayram A, Uguz A, Akay SK. Mater. Design 2009, 30, 2211–2221.10.1016/j.matdes.2008.08.034Suche in Google Scholar

[16] Hu Z, Yuan S, Wang X, Liu G, Huang Y. Mater. Design 2011, 32, 5055–5060.10.1016/j.matdes.2011.05.035Suche in Google Scholar

[17] Fu R-D, Zhang J-F, Li Y-J, Kang J, Liu H-J, Zhang F-C. Mater. Sci. Eng. A, 2013, 559, 319–324.10.1016/j.msea.2012.08.105Suche in Google Scholar

[18] Sharma C, Dwivedi DK, Kumar P. Mater. Design 2013, 43, 134–143.10.1016/j.matdes.2012.06.018Suche in Google Scholar

[19] Sree Sabari S, Balasubramanian V, Malarvizhi S, Madusudhan Reddy G. J. Mech. Behav. Mater. 2015, 24, 195–205.10.1515/jmbm-2015-0021Suche in Google Scholar

[20] Elangovan K, Balasubramanian V. Mater. Char. 2007, 59, 1168–1177.10.1016/j.matchar.2007.09.006Suche in Google Scholar

[21] Suvillian A, Robson JD. Mater. Sci. Eng. A, 2008, 478, 351–360.10.1016/j.msea.2007.06.025Suche in Google Scholar

[22] Charit I, Mishra RS. Scr. Mater. 2008, 58, 367–371.10.1016/j.scriptamat.2007.09.052Suche in Google Scholar

[23] Charit I, Mishra RS, Mahoney MW. Scip. Mater. 2002, 47, 631–636.10.1016/S1359-6462(02)00257-9Suche in Google Scholar

[24] Chen YC, Feng JC, Liu HJ. Mater. Char. 2007, 58, 174–178.10.1016/j.matchar.2006.04.015Suche in Google Scholar

[25] Aydin H, Bayram A, Durgun I. Mater. Des. 2010, 31, 2568–2577.10.1016/j.matdes.2009.11.030Suche in Google Scholar

[26] Rhodes CG, Mahoney MW, Bingel WH. Scr. Mater. 1997, 36, 69–75.10.1016/S1359-6462(96)00344-2Suche in Google Scholar

[27] Mahgony MW, Rhodes CG, Flintoff JG, Spurling RA, Bingel WH. Metta. Mater. Trans. A, 1998, 29, 1955–1964.10.1007/s11661-998-0021-5Suche in Google Scholar

[28] Khodir SA, Shibayangi T. Mater. Sci. Eng. B 2008, 148, 82.10.1016/j.mseb.2007.09.024Suche in Google Scholar

[29] Attallah MM, Salem HG. Mater. Sci. Eng. A, 2005, 391, 51–59.10.1016/j.msea.2004.08.059Suche in Google Scholar

[30] Humphrereys FJ, Hatherly M. Recrystallization and Related Annealing Phenomena, 2nd ed. Elsevier, New York, 2004.10.1016/B978-008044164-1/50016-5Suche in Google Scholar

©2016 Walter de Gruyter GmbH, Berlin/Boston

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial License, which permits unrestricted non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Frontmatter

- Eccentric annular crack under general nonuniform internal pressure

- Path-dependent J-integral evaluations around an elliptical hole for large deformation theory

- On the correct interpretation of compression experiments of micropillars produced by a focused ion beam

- Influences of post weld heat treatment on tensile strength and microstructure characteristics of friction stir welded butt joints of AA2014-T6 aluminum alloy

- Effect of tool velocity ratio on tensile properties of friction stir processed aluminum based metal matrix composites

- Friction surfacing for enhanced surface protection of marine engineering components: erosion-corrosion study

- Propagation of SH waves in a regular non-homogeneous monoclinic crustal layer lying over a non-homogeneous semi-infinite medium

- Tsallis statistics and neurodegenerative disorders

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Frontmatter

- Eccentric annular crack under general nonuniform internal pressure

- Path-dependent J-integral evaluations around an elliptical hole for large deformation theory

- On the correct interpretation of compression experiments of micropillars produced by a focused ion beam

- Influences of post weld heat treatment on tensile strength and microstructure characteristics of friction stir welded butt joints of AA2014-T6 aluminum alloy

- Effect of tool velocity ratio on tensile properties of friction stir processed aluminum based metal matrix composites

- Friction surfacing for enhanced surface protection of marine engineering components: erosion-corrosion study

- Propagation of SH waves in a regular non-homogeneous monoclinic crustal layer lying over a non-homogeneous semi-infinite medium

- Tsallis statistics and neurodegenerative disorders