Abstract

This paper discusses ideophonicity in Gizey (Chadic), viz., the ability of a word to depict sensory experiences. The term “ideophone” is frequently attested in the Gizey literature. While ideophones are classified as a separate word class (part-of-speech), the questions of what they are (phono-semantic characterisation) and how they function (morphosyntactic characterisation) are absent from that literature. Both concerns are addressed in this paper. I first describe the morphophonological, semantic, and syntactic properties of the words classified as “ideophones”. Then, I show that, indeed, Gizey contains several ideophonic words which distribute across different word classes. Thus, ideophones do not form a separate word class in Gizey as previous literature suggests.

1 Introduction

Ideophones have been defined as “an open lexical class of marked words that depict sensory imagery” (Dingemanse 2019: 16). While the interest in ideophones has grown steadily, there still persist several mistaken assumptions in the literature that warrant specific attention being given to this topic. One such mistaken assumption is that ideophones constitute a distinct word class (part-of-speech) in every language in which they are attested. As Newman (1968: 108) notes, “the tendency to treat the term ‘ideophone’ as being parallel to such terms as noun, verb, or adverb conceals the fact that ideophones often constitute a subclass of some major category.” Also, as Ameka (2001: 26) points out, ideophones “are first and foremost a type of words – a lexical class of words – which need not belong to the same grammatical word class in a particular language nor across languages”. What is highlighted here is the fact that phono-semantic characterisation, which allows of the identification of ideophones crosslinguistically, should not prevent a morphosyntactic approach to ideophones.

The term “ideophone” seems well established in the Gizey literature. As can be seen from Table 1, the Gizey-French dictionary (Ajello and Melis 2008) naturally contains most of the mentions (262), while other publications include only a limited number of occurrences.

Sources on Gizey that make mention of the term “ideophone” and its derivative “ideophonic”, and the number of occurrences therein.

| Sources | Occurrences |

|---|---|

| Ajello (2011) | 3 |

| Ajello and Melis (2008) | 262 |

| De Dominicis (2008) | 8 |

| Gaffuri et al. (2019) | 1 |

| Guitang (2022) | 8 |

| Ajello (2006) | 1 |

Generally, the term “ideophone” is used as a word class tag. For example, entries in Ajello and Melis (2008) precede the abbreviation “id.” (for “ideophone”) (e.g., (1)).

| bà id. – renforce la négation. àn zàwn fì vù ɗì bà : je n’ai vraiment rien trouvé. |

| bà id. – reinforces negation. àn zàwn fì vù ɗì bà : I have really found nothing (my translation). |

| Ajello and Melis (2008: 3) |

The same use also occurs in Ajello (2011: 10): “kíléŋ ‘(ideophone) calm, serious’; bèmmà ‘(ideophone) very short person/with big belly’”. Interestingly, in such glosses, other word class tags (e.g., “noun” or “verb”) are not explicitly provided. It would therefore appear that authors feel an urge to mark specific words as “ideophones”.

In some cases, tagging specific words as “ideophones” is used as a strategy to avoid that they be mistaken for other categories. For example, it seems from the entries under (2) that the author marks the words as “ideophones” because the translations evoke verbs or nouns.

| [bíŋ] ‘ideophone (to come out of a hole quickly)’ |

| [míŋ] ‘ideophone (a stroke or to get an erection)’ |

| De Dominicis (2008: 12) |

In other cases, the term “ideophone” appears in translations. For example, De Dominicis (2008: 9) translates the word kíh as “ideophone for a sudden fall”. Finally, some authors use “ideophone” while discussing specific linguistic phenomena or constraints. For example, De Dominicis (2008) lists ideophones amongst the words, including compounds, reduplicatives, toponyms, and loans, that violate the so-called disyllabic constraint: “roots never exceed two syllables” (De Dominicis 2008: 14). Guitang (2022), for his part, includes ideophones in the list of words in which frozen reduplication can be observed.

It is interesting to devote a few lines to discussing the relative size of the set of items to be characterised below. As indicated above, Ajello and Melis (2008) includes 262 lexical entries with the tag “ideophone”. It would appear that this class is relatively large, if compared, for example, to the class of “adverbs”, which includes only about 20 members. However, 262 is small in comparison to the words tagged “noun”, numbering 1345 in the same source. From a Northern Masa perspective, 262 also does not seem to constitute a large inventory. The description of Musey ideophones by Roberts and Soulokadi (2019), for example, is based on 500 items. The Masana-French dictionary (Melis 2006), for its part, includes more than 900 words tagged “ideophone”. What this suggests is that the size of the Gizey set of ideophones is probably underestimated. Note, furthermore, that I have collected some 120 additional ideophones from my personal fieldwork.

The datasets used for this paper comprise secondary data drawn mainly from Ajello and Melis (2008), and primary data I collected in the field in 2019. The lexical data from Ajello and Melis (2008) were extracted manually and entered into a FieldWorks lexicon (SIL Language Technology 2002). The original French glosses were translated into English. The data I collected in the field include folktales and controlled data elicited with verbal and visual stimuli from the Questionnaire on Information Structure (Skopeteas et al. 2006). These data include more than 30,000 words for about 4,000 segments (sentences). The narrative data were provided by 14 different speakers, male and female, aged 14 and above. Other translations, elicitations, grammaticality judgments, and consultants’ comments were collected at distance via WhatsApp (Meta Platforms 2023). Different distribution queries relating to phonology were run on Phonology Assistant (SIL Language Technology 2021).

This paper is organised thus. I first describe the salient properties of the words classified as “ideophone” both in my work and in previous research (Section 2). Then, I review definitions of the concept “ideophone” in Section 3, in order to answer the question whether the Gizey words classified as ideophones are indeed ideophones. I argue that ideophonicity, to be defined as the ability of a word to depict sensory experiences, manifests itself in Gizey. I also argue that ideophonicity occurs across different word classes. Thus, ideophones do not constitute a single word class in Gizey (Section 4). The approach outlined aligns well with Newman’s (1968) description of ideophones in the Chadic languages Hausa and Tera. In both languages, ideophonic words are distinguished by specific phono-semantic criteria. However, their distribution across grammatical classes varies according to their syntactic behaviour. The words labelled “ideophone” (a word class) in previous research on Gizey, distribute into the adjective and adverb classes, to be defined in Section 4. Finally, given that ideophones that are used adverbially can show properties of interjections, I distinguish both categories in Gizey (Section 4). Section 5 concludes this paper.

2 The properties of Gizey ideophones

In this section, I describe the morphophonological, semantic, and syntactic properties of the words classified as ideophones in the Gizey literature.

2.1 Morphophonological properties

The words labelled “ideophone” in descriptions of Gizey are relatively “normal” words with respect to their phonology and phonotactics, i.e., they do not show many remarkable features not attested elsewhere in the system. I emphasise this phonological normality because the default assumption appears to be that ideophones are phonological rebels, characterised by the use of marginal sounds or sounds otherwise absent from the prosaic system. But this is far from being a universal property of ideophones, as in many languages, ideophones can have normal phonology. And, as pointed out by Nuckolls et al. (2016), the apparent phonological “deviations” observed in ideophones follow a systematic pattern to a) expand the use of uncommon segmental and prosodic segments, b) expand the articulatory potential, and c) fill “gaps” in the phonological inventory. These consistent patterns invite us to reconsider whether ideophones are “really as weird and extra-systematic as linguists make them out to be” (Newman 2001).

In Gizey, the syllabic structures attested in the words classified as ideophones, namely CV (e.g., ŋì ‘hitting energetically’) and CVC (ʤɛ̀r ‘frying sound’), occur throughout the Gizey lexicon. These syllabic structures can occur on their own (monosyllabic) or combine to produce disyllabic (3) or trisyllabic ideophones (4). Words in Gizey are generally monosyllabic or disyllabic. Ideophones also abide by this constraint. Ideophones involving three or more syllables frequently involve frozen reduplication (to be discussed below).

| CVC.CV | dùrlú | ‘vast’ |

| CVC.CVC | ʧélɓét | ‘slippery’ |

| CV.CV | gùlí | ‘waddling’ |

| CV.CVC | ɓíwíw | ‘bitter’ |

| Ajello and Melis (2008) | ||

| CVC.CV.CV | ʧùkʧùrì | ‘on the side’ |

| CVC.CV.CVC | kúrbúʤúk | ‘completely’ |

| CV.CV.CV | kùzòrò | ‘slowly’ |

| CV.CV.CVC | bìgìrìw | ‘very large (of ears)’ |

| CV.CVC.CVC | ʔèlèŋrèŋ | ‘very narrow’ |

| Ajello and Melis (2008) | ||

As for the segmental material occupying the syllabic positions just discussed, there is no remarkable difference between ideophones and other lexical items. There also seems to be no specific constraint on the occurrence of certain consonants or vowels that is specific to ideophones. For example, polysyllabic ideophones tend to be monovocalic, just as is the case with other polysyllabic words. When polysyllabic ideophones involve different vowel qualities, a preference for the sequence /i/-/ɛ/ ([i]C[ɛ]) can be noticed. Examples include: hímɛ́s/hísɛ́s ‘excessively dry’ and kìrɛ̀s ‘hard (of an object)’.

Ideophones relating to sound emission (phonomimes) tend to include the vowel /i/ (e.g., brìt ‘sound of pooing’, gìndìm ‘loud sound, especially of a gunshot’). But this vowel is also attested in other ideophone subclasses, including phenomimes (i.e., perceptions of the external world, e.g., dìrìp ‘filled’, dìrlìŋ ‘in large numbers’) and psychomimes (i.e., perceptions of the internal world, e.g., sírìŋ ‘cleared, free’).

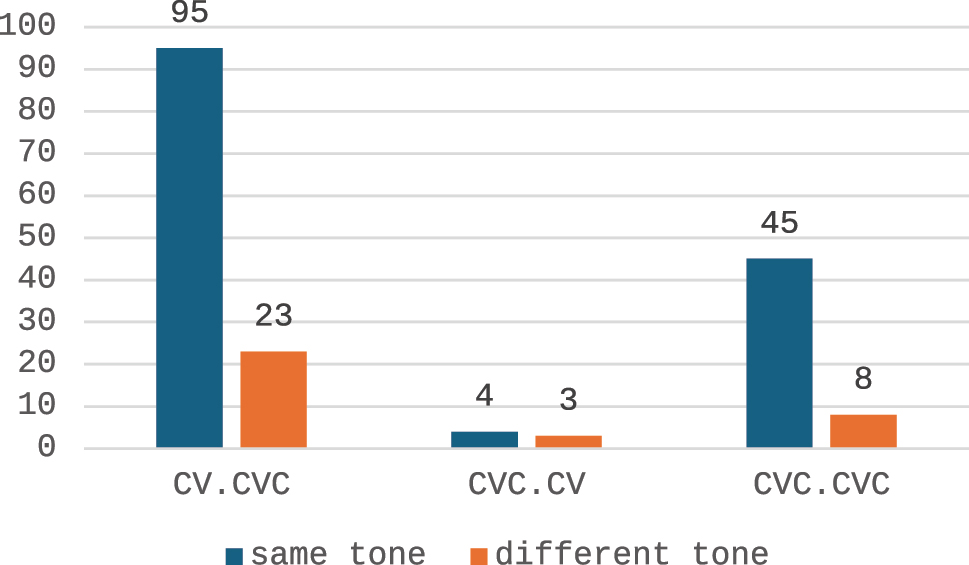

As for tone, the tonal schemes occurring in ideophones are L (e.g., kìrèɗ ‘associated with sliding’, dà ‘directly’, pèŋgèfì ‘small’), H (e.g., híʤíp ‘(with mít ‘die’) qualifies death that occurred while being bedridden’, tíníŋníŋ ‘huge quantity’, ɗít ‘violently’), LH (e.g., dùrlú ‘vast’, bìgímgím ‘loud sound of water’) and HL (e.g., kéɓèrèɗ ‘describing very small ears’, kégéglèkgè ‘cock-a-doodle-do’, ʧálàl ‘well, clearly’). These lexically specified tonal patterns also occur elsewhere in the lexicon. In Gizey, it is mostly verbs that have clearly predictable tonal patterns (see, e.g. De Dominicis 2006; Guitang 2024). A considerable proportion of polysyllabic ideophones are monotonal, i.e., they surface with one tone value (either H or L) throughout. Figure 1 shows the tonal configurations of disyllabic CV.CVC, CVC.CV, and CVC.CVC ideophones. A clear tendency for monotonality can be observed. This tendency can also be observed elsewhere in Gizey. In nouns, for example, about 65 % of CV.CVC roots are monotonal.[1]

Disyllabic CV.CVC, CVC.CV, and CVC.CVC ideophones and their tone patterns. Polysyllabic ideophones tend to be monotonal. Counts are indicated.

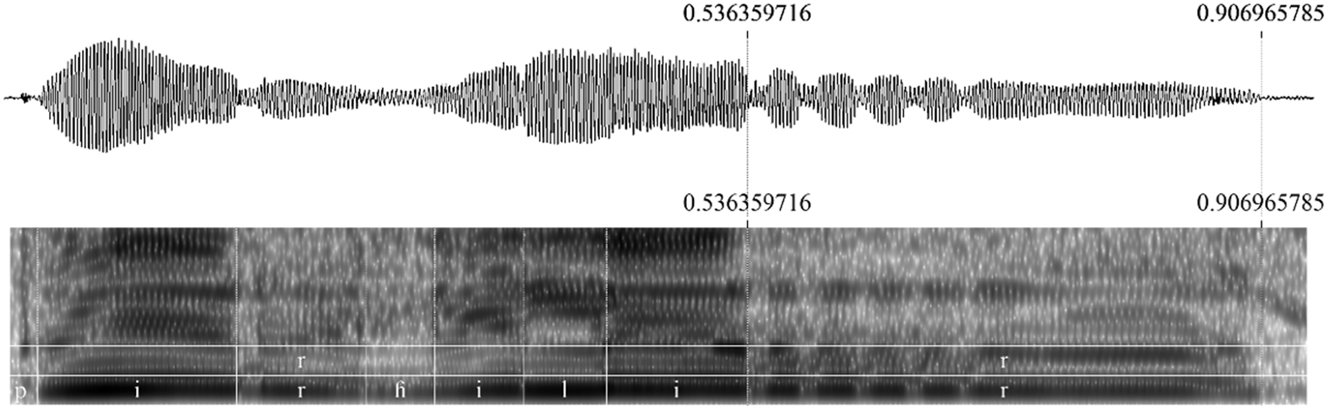

In spite of this general normality, Gizey ideophones do display certain structural properties that are unique or exhibited by them mostly. One such property is segmental lengthening. Segmental lengthening targets the internal vowels (e.g., fɛ́ɛ́ɛ́t ‘quickly and effortlessly’) or the final /r/ of ideophones. Lengthening is depictive, as it mirrors a property of the described eventuality. Figure 2, which combines waveform and spectrogram generated in Praat, allows a comparison between the realisations of two /r/s. The first one occurs in the verb pír ‘flee, fly off’ and the second in the ideophone ɦílír, which depicts flying from one point to another. Note that the final /r/ of ɦílír is realised with an extra length (≈370 ms against ≈93 ms for the first realisation). This would seem to mirror the duration of levitation.

Praat image to compare the realisation of two /r/s in the segment pír ‘flee, fly off’ + ɦílír ‘levitating’. Second /r/ is remarkably longer. Female speaker.

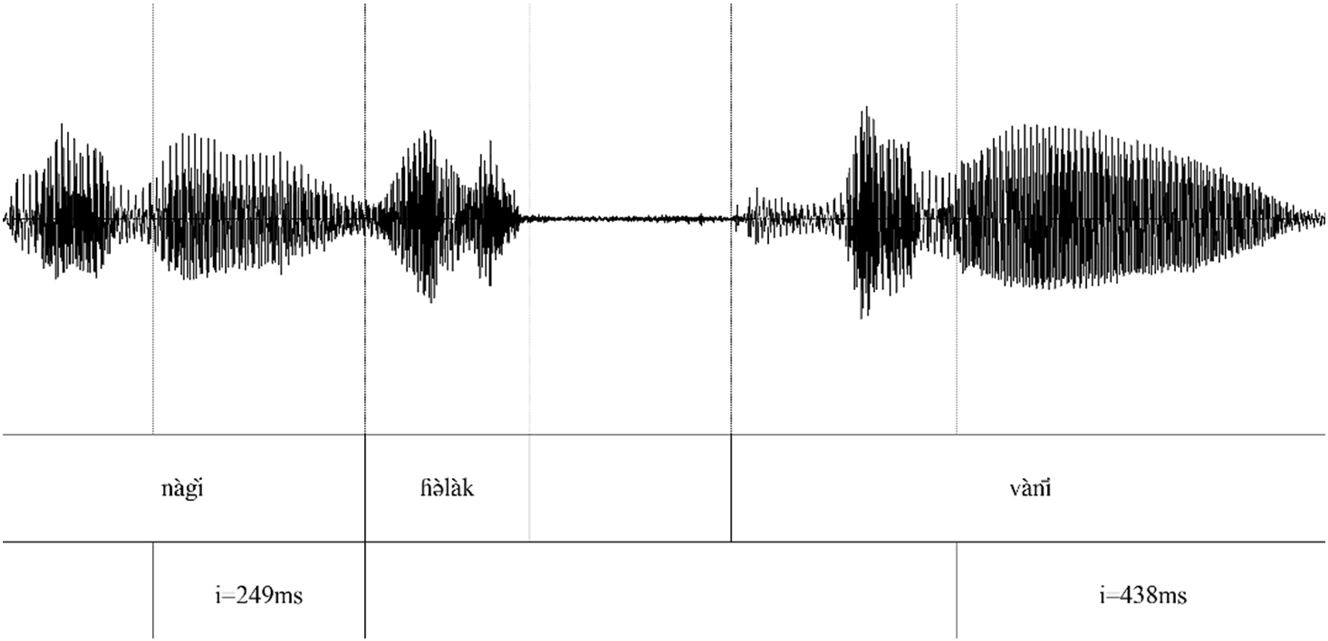

Elsewhere in Gizey, segmental lengthening chiefly occurs in the context of a pause (including hesitations), and the process only targets final vowels (non-iconic). The lengthening of final vowels in this context constitutes a pause filling strategy. Figure 3 below is a waveform of the segment nàgì ɦə̀làk vànī ‘You, give this thing (hesitation)’ (5). The final vowels (i) of the vocative nàk ‘2sf’ and the hesitation marker vànī ‘this.X’[2] are produced with extra length.

Final vowel lengthening as a pause filling strategy. Two final /i/s produced with extra length.

| nàg-ì | ɦə̀l=àk | vàn-ī |

| 2sf-fv | give.impv=2sf | this.X-fv |

| ‘You, give this thing (hesitation)’ | ||

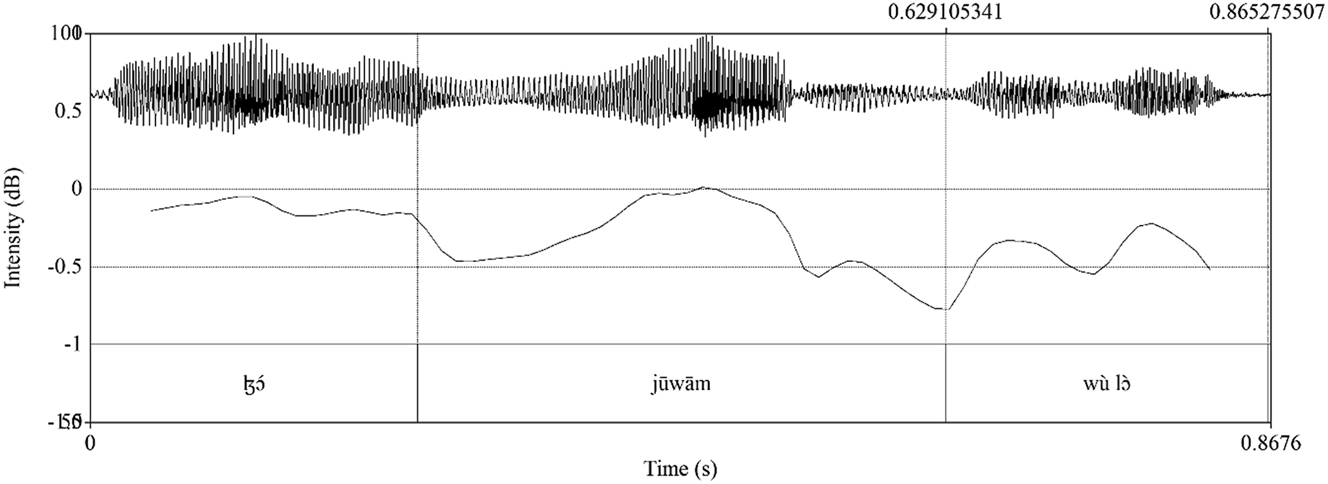

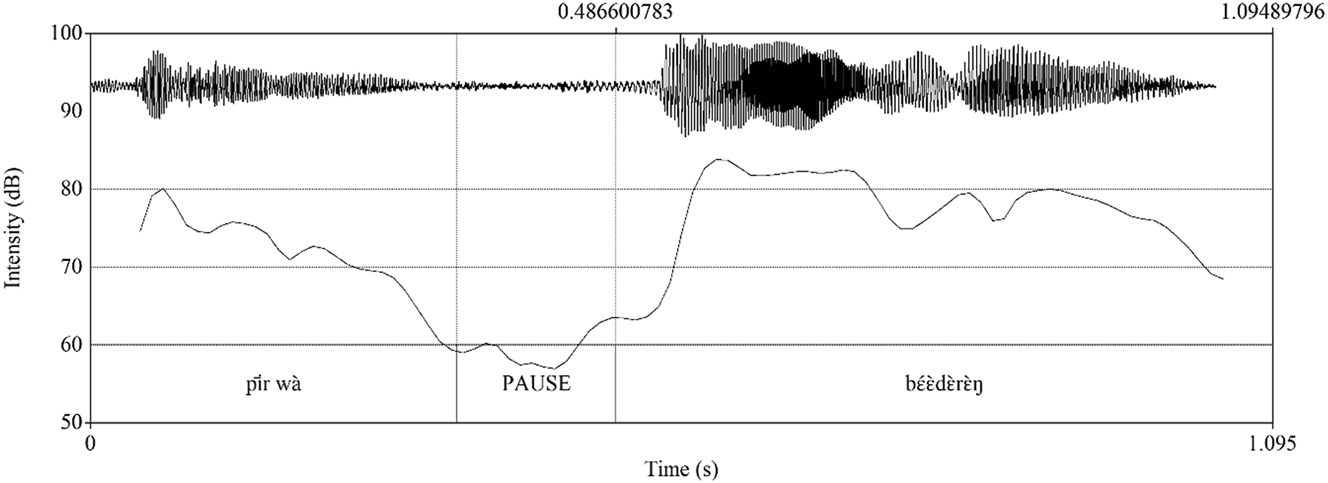

Ideophones are frequently uttered with foregrounded prosody (see, e.g., Akita 2021). Figures 4 and 5 compare the realisations of the adverb lɔ̀ ‘again’ and the ideophone bɛ́ɛ̀ŋdɛ̀rɛ̀ŋ ‘abruptly’, respectively, in the constructions provided in (6) and (7). Note the rise in amplitude in the realisation of bɛ́ɛ̀ŋdɛ̀rɛ̀ŋ (Figure 5).

Wave, intensity trace, and Textgrid, of ɮɔ́ jūwām wū lɔ̀ ‘Zlo took him again’.

Wave, intensity trace, and Textgrid of pīr wā bɛ́ɛ̀dɛ̀rɛ̀ŋ ‘jumped abruptly’. Ideophone bɛ́ɛ̀ŋdɛ̀rɛ̀ŋ produced after pause and pitch reset (foregrounded prosody).

| ɮɔ́ | jūw=ām | wū | lɔ̀ |

| Zlo | take.pfv=3sm | compl | again |

| ‘Zlo took him again.’ | |||

| Ø | pīr | wā | bɛ́ɛ̀ŋdɛ̀rɛ̀ŋ |

| pro | jump.pfv | compl | idph.abruptly |

| ‘He jumped abruptly.’ | |||

Three replicative processes manifest in ideophones: a) final syllable iteration, b) syntactic repetition, and c) frozen reduplication.

Final syllable iteration consists in the iteration of ultimate syllables, n number of times (as many as the speaker can sustain). This process is illustrated in Table 2. Only words classified as ideophones show this kind of iteration.

Final syllable iteration. Bases not attested independently.

| Bases | Examples | Gloss |

|---|---|---|

| sɛ́lɛ́rɛ́ | sɛ́lɛ́rɛ́-rɛ́-rɛ́-rɛ́ | ‘extremely thin’ |

| wɛ́tɛ́t | wɛ́tɛ́t-tɛ́t-tɛ́t-tɛ́t | ‘water pouring continuously’ |

| kɛ́rtí | kɛ́rtí-tí-tí-tí-tí | ‘a cutlass being neatly sharpened’ |

| kúlɔ̀rɔ̀ | kúlɔ̀rɔ̀-rɔ̀-rɔ̀-rɔ̀ | ‘wall gecko running steadily’ |

| háná | háná-ná-ná-ná-ná | ‘elephant running steadily’ |

Syntactic repetition involves the repetition of a whole word or clause, n number of times. The repetition of ideophones, illustrated in (8), depicts long duration, increasing quantity, and repetitive actions. While other words can be repeated similarly, in narrative texts, for example, ideophones frequently appear repeated, while other words do so only occasionally.

| ɮɔ́ | ʧì | húl=tì | tát | tát | tát | tát |

| Zlo | beat.pfv | tortoise=nongen.sf | idph.long_duration | |||

| ‘Zlo beat Tortoise continuously.’ | ||||||

Finally, frozen reduplication involves the reduplication, total (9) or partial (10), of bases not attested synchronically. In Gizey, frozen reduplication is also attested in nouns. Generally, reduplicants are faithful copies of the base strings at segmental and suprasegmental levels (see, e.g., (9) and (10)). Minimal changes, especially vowel deletion, can be observed in CVCV-CVCV reduplicatives (see Guitang 2022).

| bàʤàŋbàʤàŋ | ‘disorderly’ |

| dɔ̀kdɔ̀k | ‘always’ |

| Ajello and Melis (2008) | |

| lígìwgìw | ‘very long’ |

| ʔìlèŋrèŋrèŋ | ‘very narrow’ |

| tíníŋníŋ | ‘huge quantity’ |

| bìgímgím | ‘loud sound of water’ |

| Ajello and Melis (2008) | |

Final syllable iteration (Table 2) is different from final -CVC reduplication (10). In the former, the number of iterations depends on the communicative intentions of the speaker, and it cannot be predicted. Final -CVC reduplication, for its part, always involves a single copy of the final syllable. Also, while final syllable iteration is active and productive, final -CVC reduplication is a frozen process (Guitang 2022).

Ideophones that occur sentence-finally are sometimes not integrated syntactically. Two kinds of evidence can be used to show that ideophones are sometimes not integrated syntactically. The first kind of evidence relates to the phonetic realisation of CV postverbal particles like the completive particle wV (V for vowel slot) and the reversative particle gV. When they are used, these postverbal particles occupy a slot before adverbs. Interestingly, CV postverbal particles show positional allomorphy: in sentence-internal position (contextual/non-pausal form), their V slot is occupied by a high vowel, and in sentence-final position (non-contextual/pausal form), their V slot is occupied by a low vowel. Thus, the completive particle wV surfaces as wī or wū when it occurs sentence-internally and as wā in sentence-final position. The reversative particle, for its part, surfaces as gù sentence-internally and as gɔ̀ in sentence-final position. Example (11) shows the completive particle in contextual and non-contextual forms. In the first occurrence, the completive particle is sentence-internal (followed by the locative adverb gàŋgá ‘down’), it surfaces with a high vowel. In the second occurrence, however, the particle is not followed by any constituent, hence the low vowel.

| Gola drank plenty of milk for a long time | |||||||

| ɬī | dùttú | wū | gàŋgá | kɛ̀jn | Gola | mìt | wā |

| take.pfv | calabash | compl | down | dem | Gola | die.pfv | compl |

| ‘As the calabash was taken down, Gola died.’ | |||||||

Therefore, to show that an ideophone is not integrated in the syntax, it suffices to examine the surface realisation of preceding postverbal CV particles. If CV postverbal particles surface with a high vowel, then the ideophone is integrated (since the particle is not the final element). If, on the other hand, they surface with a low vowel, then the ideophone is not part of the preceding linguistic structure. To begin, consider the case in (12) where an ideophone is used. As can be seen, the ideophone fɛ́ɛ́ɛ́t is preceded by the reversative particle gù, which surfaces in its contextual form gù. Thus, in (12), fɛ́ɛ́ɛ́t is integrated syntactically as the last item of the structure.

| v=áʔ | kɛ̀jn | Ø | ŋə́d=áʔ | gù | fɛ́ɛ́ɛ́t |

| catch.pfv=3sf | dem | pro | slaughter.pfv | rev | idph.quickly_effortlessly |

| ‘As he1 caught her2, he1 slaughtered her2 dead.’ | |||||

The example in (13) shows the same facts with the completive particle and adverb lɔ̀ ‘again’. In this example, the completive particle precedes the adverb lɔ̀ ‘again’ in its contextual form wū. This suggests that lɔ̀ ‘again’ is fully integrated in that structure, and there is no pause preceding it (see Figure 4 above).

| ɮɔ́ | jūw=ām | wū | lɔ̀ |

| Zlo | take.pfv=3sm | compl | again |

| ‘Zlo took him again.’ | |||

Now, compare the realisation of the completive particle in (13) with its form in (14), involving an ideophone. In contrast, to (13), the completive particle surfaces with the pausal form wā in (14), in the context of the ideophone. The occurrence of this pausal form in (14) indicates that the ideophone bɛ́ɛ̀ŋdɛ̀rɛ̀ŋ is untethered, i.e., not connected with the previous linguistic structure. Note the significant pause between wā and bɛ́ɛ́ŋdɛ̀rɛ̀ŋ in Figure 5.

| Ø | pīr | wā | bɛ́ɛ̀ŋdɛ̀rɛ̀ŋ |

| pro | jump.pfv | compl | idph.abruptly |

| ‘He jumped abruptly.’ | |||

The second kind of evidence that ideophones are sometimes not integrated in the preceding construction relates to the occurrence of the final vowel. In Gizey, words generally bear a final vowel when they occur in sentence-final position. Compare the realisations of ʤùf ‘male’ in (15) and (16). In (15), ʤùf bears a final vowel since nothing follows it. In (16), however, ʤùf lacks a final vowel since it occurs sentence-internally.

| A child was born. Was it a boy or a girl? | |

| gɔ̀r | ʤùf-ú |

| child | male-fv |

| ‘A boy’ | |

| sà | ʤùf | máj | hàj | vù | ɗī |

| person | male | neg | inside | home | neg |

| ‘There was no male in that house.’ | |||||

Now observe that the word lìj=ná ‘place=nongen.sm’, which precedes the ideophone kìbìlìm in (17), maintains its final vowel. This suggests that the material preceding the ideophone is parsed as a distinct structure.

| nàʔ | hɔ̄j | wū | gɛ̀ɗ | lìj=ná |

| 3sf | return.pfv | compl | shake.ipfv | place=nongen.sm |

| kìbìlìm | kìbìlìm | kìbìlìm | ||

| idph.dog_canter | idph.dog_canter | idph.dog_canter | ||

| ‘She went back to shake the place while cantering.’ | ||||

As just pointed out, words bear a final vowel when they occur sentence-finally. While words from major word classes in Gizey (e.g., nouns and verbs), must bear a final vowel, ideophones only do so optionally. Thus, for example, the ideophone fáɗ ‘directly’ can be found with or without a final as shown in (18) and (19), respectively. I cannot yet explain this variation.

| ràw | tàm | sí | vì | mùl | kápráwn | fáɗ-ì |

| continue.pfv | against | rel.sm | of | chief | Kaprawn | directly-fv |

| ‘(She) went right away close to Chief Kapraw’s people.’ | ||||||

| nàŋ | hɔ́j | gù | fáɗ |

| 2sm | return.ipfv | rev | directly |

| ‘You return directly.’ | |||

2.2 Semantic properties

The meanings of ideophones are sometimes very specific (see Childs 1994; de Jong 2001 for similar observations). For example, the meaning of the ideophone ɓlùk is given as ‘medium-size colour spots of bovinae and ovicaprids’ (Ajello and Melis 2008). Another example is gìdrìŋ, which refers specifically to the way sheep run, or híjɛ́s, often occurring with mít ‘die’, which qualifies a dying eventuality which followed a long-term illness (Ajello and Melis 2008). Phonomimes (sound ideophones), for their part, may refer to specific sounds produced by specific objects. For example, gít renders the sound produced when a stick is thrown on someone. The very specific meanings most likely account for the fact that some ideophones seem to pair only with specific verbs from which they derive most of their meaning. Such ideophones include the forms ʧɛ́dɛ́t, tìŋ, and trɛ̀s that occur specifically with mùs ‘wash’ (mùs ʧɛ́dɛ́t ‘wash clean’), vì ‘hold’ (vì tìŋ ‘grip’), and hárás ‘cut in two parts’ (hárás très ‘cut in many small parts’); respectively.

The meanings expressed by Gizey ideophones cover all the levels of McLean’s (2021) implicational hierarchy (revising Dingemanse 2012), as can be seen under Table 3. The “other sensory perception” category is not limited to the sense of touch, as Table 3 would suggest. This class also includes colour (e.g., hɔ̀l ‘reddish’), taste (e.g., hùt ‘very salty’) and inner perceptions (e.g., ʤìgɛ́r ‘alert’, hɔ̀lɔ́ŋ ‘healthy’).

Gizey “ideophones” illustrating different points along McLean’s (2021) implicational hierarchy.

| Points | Examples | Gloss |

|---|---|---|

| Sound | ɮìk | ‘regular and continuous sound’ |

| gìndìm | ‘loud (gun) sound’ | |

| Movement | gìdrìŋ | ‘the way sheep run’ |

| jɔ̀ʔɔ̀r | ‘the way a sick or wet chicken walks’ | |

| Form | hùɗɔ̀ɗ | ‘round’ |

| ɗìgɛ̀rgɛ̀r | ‘straight’ | |

| Texture | ʤìɓ | ‘soft, melting’ |

| kìrɛ̀s | ‘crusty’ | |

| Other sensory perception | wìlìk | ‘very hot’ |

| hɔ́lɔ́l | ‘cold’ |

2.3 Syntactic properties

Across previous descriptions of Gizey, the words tagged ideophone are attested in two syntactic roles, namely, as predicates in nonverbal clauses or predicate modifiers. The predicate function is illustrated in (20), which involves the ideophone ʧélɓét ‘slippery’. The predicate modification function is illustrated in (21), which involves the ideophone mìɗìk ‘in large numbers’. In these functions, the ideophone is generally the last item in the sentence.

| sáɓ | vùn=ùm | ʧélɓét |

| spear | mouth=3sm | idph.slippery |

| ‘The edge of the spear is sharp.’ (Ajello and Melis 2008: 17) | ||

| ʤùvùl=l | túɗ | mìɗìk | mìɗìk |

| maggot=nongen.pl | walk.ipfv | idph.in_large_numbers | |

| ‘Maggots throng.’ (Ajello and Melis 2008: 85) | |||

Most ideophones select only one of these functions, while a few can fulfil both. In (22) and (23), the ideophone ɦàmlàk ‘askew’ can be seen in predicate and predicate modification functions, respectively.

| àr=àm | ɦàmlàk-ì |

| eye=3sm | idph.askew-fv |

| ‘He has a squint.’ (lit. ‘his eyes (are) askew’). (Ajello and Melis 2008: 55) | |

| nàm | túɗ | ɦàmlàk-ì |

| 3sm | walk.ipfv | idph.askew-fv |

| ‘He walks sideways.’ (Ajello and Melis 2008: 55) | ||

Ideophones are generally the last constituents in the sentence.

2.4 Interim summary

I just described the morphophonological, semantic, and syntactic properties of the words tagged “ideophone” in the Gizey literature. Ideophones share many features with other Gizey words. For example, ideophones do not show excessive “deviant” phonology as is the case in some languages. However, ideophones have certain properties that are unique, including internal vowel and final /r/ lengthening, final syllable iteration, the ability to be physically detached from preceding linguistic structures, etc. Some properties, e.g., exaggerated use of repetition and foregrounded prosody, only manifest more in ideophones as compared to other words. The key takeaway is that while identifying ideophones in Gizey might be difficult when examining a static word list, their distinct properties (discussed above) make them readily recognisable in the dynamic context of a story or lively conversation.

The question to be answered now is whether the words discussed so far are indeed ideophones, based on what “ideophone” means crosslinguistically.

3 Gizey “ideophones” are ideophones

To arrive at this conclusion, I first review definitions of the term “ideophone”. Then, I show that the words under discussion have the key properties of ideophones.

3.1 What are ideophones?

Dingemanse (2019: 15–16) lists the following as properties that define ideophones crosslinguistically:

ideophones are marked, i.e., they have structural properties that make them stand out from other words

they are words, i.e., conventionalized lexical items that can be listed and defined

they depict, i.e., they represent scenes by means of structural resemblances between aspects of form and meaning

their meanings lie in the broad domain of sensory imagery, which covers perceptions of the external world as well as inner sensations and feelings

ideophones form an open lexical class, i.e., a set of lexical items open to new additions

Dingemanse’s (2019) characterisation (i-v) includes properties that can be described as primary and others that can be described as consequential to some of the primary properties. The primary properties are (ii), (iii), and (iv), i.e., ideophones are words, and these words depict sensory experiences. These primary properties are included in all accepted definitions of ideophones. Consider these popular definitions by Doke and Kunene.

A vivid representation of an idea in sound. A word, often onomatopoeic, which describes a predicate, qualificative or adverb in respect to manner, colour, sound, smell, action, state or intensity (Doke 1935: 118).

An ideophone is a dramatization of actions or states (Kunene 1978: 3).

The main feature highlighted in these definitions is that ideophones depict (“vivid representation”, “dramatization”) sensory experiences (“onomatopoeic”, “states”, “colour”, “smell” etc.).

That their status as words that depict sensory experiences can be described as primary does not entail that these properties are accepted uncontroversially. For example, for some authors, e.g., Haiman (2018), ideophones are “not quite words” (“semi-words”) or are prelinguistic material. Also, while some ideophone enthusiasts see depiction (via iconicity) everywhere, it takes some time and effort to convince an external observer.

The consequential properties of being words that depict sensory experiences are (i) and (v). Beginning with point (i), that ideophones are marked can be interpreted as a more or less automatic consequence of their depictive nature. This is another way to say that ideophones are not marked for markedness’s sake. In the typological literature, the different strands that count as markedness include the occurrence of marginal sound segments (as compared to the prosaic system), unusual phonotactics and prosody, phonaesthemes,[3] replication processes, etc. (see Ibarretxe-Antuñano 2017). Take the occurrence of marginal sound segments, for example. The depiction of new auditory experiences may involve hitherto unused articulators or airstream mechanisms, thereby introducing “deviant” sounds in the phonological inventory as the nonce ideophone is domesticated.

As for point (v), given that ideophones depict sensory imagery, it is always possible to create new forms to express new sensory experiences. Thus, openness (v) also derives automatically from their nature as words that depict sensory experiences.

3.2 Gizey has ideophones

Before I elaborate on how ideophones convey meaning, I think it is useful for my readers to try and form their own idea of what it means for a word to depict a sensory experience. To that end, I invite my readers to guess what the ideophonic string hùwá hùwá hùwá hùwá hùwá hùwá depicts. We will return to this below.

As just discussed, to be counted as an ideophone, a word must be able to depict sensory experiences. But what exactly does it mean for a word to be able to depict? To depict means to provide a direct perceptual experience. Thus, ideophones provide a direct perceptual experience of things seen, heard, smelled, touched, tasted, or felt by the locutor. This can be carried out via different form-meaning mappings (iconicity) including direct iconicity, Gestalt iconicity, and relative iconicity.

Direct iconicity occurs when a word imitates a sound in the real world (Dingemanse 2014; Johansson et al. 2020) i.e., in onomatopoeia. In Gestalt iconicity, a word maps diagrammatically onto the structure of the state or event expressed. Finally, relative iconicity refers to those cases “where related forms are associated with related meanings, as when a contrast between the vowels [i:a] depicts an analogous contrast in magnitude” (Lockwood and Dingemanse 2015: 3). Two of these form-meaning mappings occur in the words classified as ideophones in the Gizey literature, namely direct and Gestalt iconicity.

Direct iconicity is instantiated in ideophones that depict the sounds produced by various objects (24) or the cries of animals (25).

| tìt | ‘sound of dripping water’ |

| gìndìm | ‘loud sound, especially of a gunshot’ |

| mɛ́ɛ́ | ‘baa’ |

| bùdùdù | ‘call of the Senegal coucal’ |

| ʧɛ́r | ‘call of the yellow-billed oxpecker’ |

| kɔ́ɔ́gɔ́ gùlɔ̀ɔ́k | ‘cock-a-doodle-do’ |

The animal cries under (25) have corresponding forms that are nouns. The nominal counterparts can include part, or all, of the material found in the cries, as can be seen from Table 4.

Four animal cries and related nouns.

| Animal cries | Related nouns |

|---|---|

| mɛ́ɛ́ ‘baa’ | mɛ́ɛ́ ‘goat’ (also ɦù mɛ́ɛ́ ‘caprine baa’) |

| bùdùdù ‘call of the Senegal coucal’ | bùtùktúk ‘Senegal coucal’ |

| ʧɛ́r ‘call of the yellow-billed oxpecker’ | ʧɛ́r ‘yellow-billed oxpecker’ |

| kɔ́ɔ́gɔ́ gùlɔ̀ɔ́k ‘cock-a-doodle-do’ | gùlɔ́k ‘cock’ |

Note that, elsewhere, the nouns under Table 4 show properties associated with nouns, e.g., plural marking: mɛ́ɛ́-gɛ́ ‘goat-pl’,[4] hosting of the non-generic clitic: bùtùktúk=ŋà ‘Senegal coucal=nongen.sm’, subject role, etc. Because of their onomatopoeic nature, one can surmise that the cries (interjections) are primary, and the nominal forms derived. For example, speakers have an auditory experience of a bleat, which they imitate (producing mɛ́ɛ́), and the output of imitation becomes the name of the animal (goat).

Gestalt iconicity is instantiated, for example, in words like kìbìlìm ‘dog canter’ where the trisyllabic shape nicely mirrors the three-beat gait of the dog. A certain amount of Gestalt iconicity occurs in verbs that describe bodily activities like excreting and coughing, which involve a certain amount of compression of the thoracic cage or the abdomen. These verbs include an initial glottal stop also produced with similar physiological disposition (Ladefoged and Johnson 2011). Examples include: ʔɔ́ɬ ‘cough (v)’, ʔɔ́k ‘excrete’, ʔɛ́ɬ ‘lay (eggs)’.

How about reduplicated words like bàʤàŋbàʤàŋ ‘disorderly’ and lígìwgìw ‘very long’ or un-reduplicated ones like gɛ̀lmɛ̀ɗ ‘lazily’ and hɔ̀lɔ́ŋ ‘healthy’, all classified as ideophones in the literature when they neither instantiate direct nor Gestalt iconicity?

There are many possible answers. One is that some of these words may instantiate conventional sound symbolism, viz. “the analogical association of certain phonemes and clusters with certain meanings” (Hinton et al. 1995: 5). This concerns, for example, frozen reduplicatives like lígìwgìw ‘very long’. The -CVC partial reduplication pattern involved (lígìw-gìw) is frequently attested in words that refer to straight and long objects, or to objects with an elongated feature. For example, the name for the hoopoe, ʤùkúlkúl, involves the -CVC reduplicative pattern. Also, many nouns using this pattern refer to snakes, e.g., ʧìkílkíl ‘Elapsoidea guntheri’. Such words are non-iconic, there is nothing in the -CVC reduplication pattern which suggests length or straightness. However, the pattern occurs in many words with similar meanings, probably via analogy, to the extent that a form-meaning connection is established.

Another possibility is that, in certain ideophones, iconicity stands instead in their gestural components rather than in their verbal components (e.g., when the verbal component lacks foregrounded prosody). For example, the non-iconic verbal string [g ɛ̀ l m ɛ̀ ɗ] ‘lazily’ is ideophonic because it is frequently (or always) associated with a representational gesture (iconic) which provides the perceptual experience. Let’s now return to the ideophone hùwá introduced above. hùwá is used to depict the gait of the chameleon (I bet that the reader did not have this in mind). No need to be particularly sceptical to doubt any connections between the string [hùwá] and the chameleon’s gait. But the iconicity involved in hùwá is expressed elsewhere, with gestures. The following link leads to a folder which contains a video showing the use of hùwá: https://bit.ly/425es0p. In that video, the speaker demonstrates the chameleon’s gait (gesture) while producing the non-iconic hùwá repeatedly (6 times).[5]

Note that this can be related to what Dingemanse (2014) refers to as “coerced iconicity”, “where the depictive presentation of some ideophones may coerce us into thinking of them as adequate renditions of the depicted material, even if the iconic mapping between form and meaning is not all that transparent” (Dingemanse 2014: 389).

Güldemann (2008: 280) characterises the duality just described as “a performance or a gesture in the disguise of a word.” It is also quite reminiscent of Dingemanse’s (2023) “text and supporting visual” analogy. Consider the example in (26).

| Ø | pīr | wā | bɛ́ɛ̀ŋdɛ̀rɛ̀ŋ |

| pro | jump.pfv | compl | abruptly |

| ‘He jumped abruptly.’ | |||

On Dingemanse’s proposal, the text would be the first segment/utterance Ø pìr wā, while the analogue of the supporting visual, which provides an image of the situation described by the first segment, would be the ideophone bɛ́ɛ̀ŋdɛ̀rɛ̀ŋ. Thus, discourse chunks like (26) juxtapose the descriptive mode of representation (the text), characterised by semiotic arbitrariness, and the depictive mode of representation (the visual support), characterised by iconicity.

This bipartition into descriptive-depictive in the same discourse chunk can be related to quotative constructions involving direct discourse. In line with the Depiction Theory (De Brabanter 2017), direct discourse is to be analysed as a demonstration, viz. an iconic communication act that enables an addressee to experience aspects of the speech of the reported speaker (see Clark and Gerrig 1990). A direct discourse segment is generally flagged as a demonstration by a related structure (matrix clause, speech introducing clause etc.), e.g., he said, she went etc. The relation with constructions involving an ideophone goes thus: the linguistic structure preceding an ideophone is a descriptive communication act relatable to the speech (e.g., ‘he said:’) and speech/non-speech framing devices (‘he goes:’) that usually serve to flag direct discourse. The ideophone, for its part, is an iconic communication act relatable to direct discourse. Thus, like direct discourse, an ideophone aims at providing a perceptual experience of a situation via its symbolic-iconic composition.

However, there is a fundamental difference between quotative constructions and constructions involving an ideophone: in the former, the structure preceding direct discourse is a flag which identifies the quoted linguistic material as a demonstration. In constructions involving an ideophone, however, the preceding linguistic structure is not a flag. Instead, it provides a descriptive (symbolic) account of a situation, which is then supported by (or accompanied by) a juxtaposed depiction (iconic) of the same situation.

4 Do ideophones form a distinct word class in Gizey?

The short answer is no, but a long answer is in order.

The classificatory strategy in the Gizey literature consisted hitherto in attributing the label “ideophone” to words that displayed the properties discussed in Section 2. Thus, ideophones are words with certain phono-semantic properties and which can be used as predicates or predicate modifiers. Consequently, ideophones were considered a distinct word class. The recognition of a separate class of ideophones has the following effects:

“Adverbs” stand as a particularly tiny class, with just about 20 members or so restricted to expressing location and time (manner being expressed exclusively by “ideophones”).

“Adjectives” include only derived members (resultative verbs), adjectival function being fulfilled chiefly by “ideophones” or “nouns”.

Words showing iconicity, of the direct or Gestalt kind, but which occupied other functions, e.g., subjects, were not included as ideophones. Thus, words like bùtùktúk ‘Senegal coucal’ (imitative noun) were excluded.

The approach adopted here, largely motivated by the injustice reported in (iii), is that ideophonicity, defined as the ability for a word to depict sensory imagery, is a universal property whose manifestations in given languages may target words from different word classes (see Kabore 1993). Ideophonicity comes out in many different strands and may manifest more or less systematically in different languages. This approach also allows for the possibility for “inherently” non-ideophonic words to be used ideophonically. Thus, for example, while English ‘long’ is not classified readily as an ideophone, it can be used ideophonically as in “it was a very looooooong snake”.[6] Implementing this in Gizey grammar means that nouns like bùtùktúk ‘Senegal coucal’ and kɔ̀rkɔ̀rɔ́ ‘African comb duck’ (imitation of cries) or verbs like ʔɔ́ɬ ‘cough’ are now classified as ideophones. As a convention, ideophones attested in different classes are referred to as “ideophonic X”, where X stands for the word class to which the ideophone belongs. For example, ideophones found in the noun word class are referred to as ideophonic nouns.

As for the interaction with the adverb and adjective classes, I consider ideophonic words that occur in adjectival function to be “ideophonic adjectives” and those occurring in adverbial function to be “ideophonic adverbs”. To be complete, I define the adjective and adverb classes below.

4.1 Defining the adjective and adverb classes

The adjective class is defined in Gizey as a class of words whose members occupy predicate role in nonverbal property predications. They can be modified by adverbs (to be defined below). Some adjectives have a morphological feature, suffixation of resultative -Vj, which signals their class membership. The target morphological construction derives adjectives from verbs. Examples of adjectives derived from verbs are provided in (27).

| bús-ɛ́j (stay-Vj) | ‘old’ |

| kùt-ɔ̀j (arrange-Vj) | ‘arranged’ |

| lùr-ìj (become mad-Vj) | ‘mad’ |

| mìd-ìj (die-Vj) | ‘dead’ |

| búw-íj (rot-Vj) | ‘rotten’ |

| gís-ɛ́j (make dirty-Vj) | ‘dirty’ |

Example (28) shows the derived adjective búwíj in a nonverbal property predication.

| ʤàn | búwíj-à |

| meat | rotten-fv |

| ‘The meat is rotten.’ (Ajello and Melis 2008: 11) | |

Most Gizey adjectives do not have morphology to attest to their membership in this class. These underived adjectives fall into two categories: ideophonic and non-ideophonic. Ideophonic adjectives exhibit the characteristics outlined in Section 2, such as foregrounded prosody and frequent repetition, while non-ideophonic adjectives align with the traits typical of prosaic vocabulary items. Examples of ideophonic adjectives include: ɦàmlàk ‘askew’, hɔ́lɔ́ŋ ‘healthy’, ŋìrìk ‘big’, etc. Underived non-ideophonic adjectives include fíjɔ̀k ‘tall’, ʤùrɔ̀j ‘young’, ɬáw ‘red’, ʤɔ̀ɔ̀ ‘bad’, nɛ́k ‘heavy’, jáw ‘incestuous’ etc. Some of these adjectives (the non-ideophonic ones) have nominal counterparts, e.g., gɔ̀r ‘child’ (noun, (29)) and gɔ̀r ‘small’ (adjective, (30)).

| gɔ̀r | mànná |

| child | mine |

| ‘My (boy) child.’ | |

| tì | gɔ̀r-ɔ́ |

| 3sf | small-fv |

| ‘She is small.’ | |

Words like gɔ̀r are classified as nouns exclusively by Ajello and Melis (2008), and adjectival uses are seen as extended uses. However, the evidence that this is just extended use is missing. Also, nouns that occur in an extended use tend to maintain a determiner (e.g., the non-generic clitic), as shown in (31) where the noun fàlɛ̀j ‘daytime’ is used adverbially. Note, in contrast, that gɔ̀r (30) does not require the non-generic clitic in adjectival function.

| ʔàn | kúl | fàlɛ̀j=t | sū |

| 1s | steal.ipfv | daytime=nongen.sf | q |

| ‘Do I steal in broad daylight? (why do you suspect me?)’ | |||

| (Ajello and Melis 2008: 36) | |||

Because there is no formal evidence for word class change (zero derivation), I take noun-adjective pairs like gɔ̀r ‘child’ (noun) and gɔ̀r ‘small’ (adjective) to involve word class flexibility (van Lier and Rijkhoff 2013). More precisely, such words involve roots that are underspecified with respect to noun or adjective category (see Luuk 2010: 352). Generally, Gizey is characterised by a considerable degree of word class flexibility.

The adverb class is defined in Gizey as a group of words used as predicate modifiers (e.g., fúrɔ́j ‘always’ in (32)). Members of this class lack inflectional and derivational morphology, and they distribute into different semantic subclasses, including manner adverbs, frequency adverbs, degree adverbs, directionals, locatives, etc. Ideophones account for the vast majority, if not all, of manner adverbs.

| sí | hə́rás | ɦùn=ùm | fúrɔ́j |

| 3pl | walk_past.ipfv | mouth=3sm | always |

| ‘They walk past him always.’ | |||

The boundary between the adjective and adverb classes is sometimes fuzzy, as some words can occupy roles associated with either of these classes. For example, the ideophonic word ɦàmlàk ‘askew’ is attested as predicate in a nonverbal property predication (33) and predicate modifier in a verbal clause (34), constructions which identify adjectives and adverbs, respectively. Here too, I take this to instantiate word class flexibility.

| àr=àm | ɦàmlàk-ì |

| eye=3sm | idph.askew-fv |

| ‘He has a squint.’ (lit. ‘his eyes (are) askew’). | |

| (Ajello and Melis 2008: 55) | |

| nàm | túɗ | ɦàmlàk-ì |

| 3sm | walk.ipfv | idph.askew-fv |

| ‘He walks sideways.’ (Ajello and Melis 2008: 55) | ||

4.2 Ideophonic adverbs and interjections

Crosslinguistically, ideophones share many features with interjections, both at the notional and formal levels (Haiman 2018; Dingemanse 2023).[7] First, both ideophones and interjections are characterised by their expressiveness. Second, ideophones and interjections can be used holophrastically, and both tend to be left untethered. Third, ideophones and interjections frequently display marked phonology. And, finally, ideophones and interjections are often accompanied by gesture, iconic (for ideophones) and non-iconic (for interjections).[8]

In Gizey, untethered ideophonic adverbs evoke the behaviour of interjections, hence the need to distinguish both.

The interjection class is defined as a class of conventionalized words that constitute utterances on their own and do not take part in any morphological or syntactic constructions. Thus, interjections lack inflectional or derivational morphology and they are autonomous (see Wilkins 1992). Typical members of this class “express a speaker’s mental state, action or attitude or reaction to a situation” (Ameka 1992: 106). Examples are provided in Table 5 below.

Some Gizey interjections.

| Interjections | Uses |

|---|---|

| háj/hɛ́j | rejection |

| hɛ́ʔ | surprise, confusion (generally precedes questions) |

| ɦí | surprise, generally an unpleasant surprise |

| hjé/ɦjé | surprise |

| húm | rejection, unpleasant surprise |

| jɔ̀ɔ̀ | used to show agreement |

| kɛ̀mkɛ̀m | used to make pleas |

| tɔ́ɔ́tɔ́ɔ́ | used to chase dogs away |

| jájò/jájà | expressing pains, usually when one is crying |

| ɦà/ɦà dɛ́ʔ | accompanies the action of giving, translates as ‘take!’ |

Also included in this class are ideophonic forms which imitate the sounds produced by different animals in my narrative data (Table 6).

Some animal-produced interjections (ideophonic).

| Forms | Gloss |

|---|---|

| mɔ́ɔ́ | ‘moo’ (cow mooing) |

| mɛ́ɛ́ | ‘baa’ (goat bleat) |

| màà | ‘baa’ (sheep bleat) |

| híígím híík | ‘hee-haw’ (donkey braying) |

| kɔ́ɔ́gɔ́ gùlɔ̀ɔ́k | ‘cock-a-doodle-do’ (cock crowing) |

| ɦɛ̀ɛ̀ | ‘neigh’ (horse whinny) |

The word forms in Tables 5 and 6 are conventionalised because they are known and used by different Gizey speakers. As for their ability to constitute utterances on their own, it can be shown in a speech reporting context. Example (35) involves the secondary interjection[9] máj ɗī, whose individual members are used elsewhere as a bipartite negator, as the sole material of the direct discourse. This is also illustrated in (36) where the interjection hjééé ‘really!’ is reported.

| nàm | lā | máj ɗī |

| 3sm | quot | no |

| ‘He says: no way!’ | ||

| nàm | kāk | ʤɛ̀ | ʤìbɛ̀r | j=ámū | ʔálà | hjééé |

| 3sm | sit.pfv | dem | think.ipfv | head=3sm | QUOT | really! |

| ‘He1 sat there, thinking: really!’ | ||||||

The key difference (non-semantic) between untethered ideophonic adverbs and interjections is that the former tend to occur at the right periphery, while interjections occur in the left periphery of discourse chunks. Consequently, untethered ideophonic adverbs cannot stand at the beginning of an out-of-the-blue utterance. Interjections, for their part, can occur in initial position, as shown in (37).

| You return home and find your children in the kitchen stealing food. You ask, surprised: | ||||||

| ʔálà | kí | l=úm | làkŋ | ìn | mí | gɛ̀ |

| interj | 2pl | do.ipfv=3sm | dem | cop | q.pro | q |

| ‘interj, what are you doing?’ | ||||||

It is by this criterion that I distinguish untethered ideophonic adverbs and interjections.

5 Conclusions

I opened this exploration of the concept “ideophone” in descriptions of Gizey with the observation that the notion is well established while it lacks a clear language-internal characterisation. I then reconstructed what “ideophone” means for authors by describing the properties of the words recognised as such. Crucially, I argued that, indeed, Gizey has ideophones, as per widely accepted definitions of the comparative concept. However, contrary to previous literature, I argued that ideophonicity, the ability of a word to depict sensory experiences, occurs across different word classes, including nouns, verbs, adjectives, and adverbs. The main insight to be gained is that ideophones do not form a distinct word class, as previous literature suggests. To account for the occurrence of certain ideophones in adjectival and adverbial functions, I hypothesised that such ideophones are characterised by word class flexibility. I defined the adjectives and adverb classes. Finally, I showed that, despite similarities at the notional and formal levels, interjections can be distinguished from untethered ideophonic adverbs on syntactic grounds.

Funding source: Université libre de Bruxelles (ULB)

Award Identifier / Grant number: Mini-ARC

Acknowledgments

I am very grateful to Julie Marsault, Yvonne Treis, and Aimée Lahaussois for corrections, discussions, and suggestions on earlier versions of this paper. I am also very grateful to Mark Dingemanse & an anonymous reviewer for their exceptionally kind words, positive feedback, and highly constructive comments. Many thanks to Philippe De Brabanter & Mikhail Kissine for their thoughtful comments. Thanks also to Pauline Maes, Joseph Lovestrand, Birgit Ricquier, Birgit Hellwig, Henning Schreiber and Ekaterina Aplonova for helpful suggestions and questions. I am very grateful to Félix Hlamma Digansia and Dieudonné Soupoursou, my consultants.

-

Research ethics: Not applicable.

-

Informed consent: Not applicable.

-

Author contributions: The author has accepted responsibility for the entire content of this manuscript and approved its submission.

-

Use of Large Language Models, AI and Machine Learning Tools: None declared.

-

Conflict of interest: Not applicable.

-

Research funding: This research was funded by the Université libre de Bruxelles (ULB) - MINI ARC framework.

-

Data availability: Not applicable.

Abbreviations

| 1= | First person | intj= | Interjection | quot= | Quotative |

| 2= | Second person | ipfv= | Imperfective | rel= | Relative pronoun |

| 3= | Third person | itv= | Itive | rev= | Reversative |

| compl= | Completive | neg= | Negation marker | sf= | Singular feminine |

| cop= | Copula | nongen | Non-generic | sm= | Singular masculine |

| dem= | Demonstrative | pfv= | Perfective | ||

| fv | Final vowel | pl= | Plural | ||

| id | Ideophone | pro | Null pronoun | ||

| idph | Ideophone | q= | Question marker | ||

| impv= | Imperative | q.pro | Question proform |

References

Ajello, Roberto. 2006. The importance of having a description of the endangered languages: The case of Gizey (Cameroon). In Amedeo De Dominicis (ed.), Undescribed and endangered languages: The preservation of linguistic diversity, 8–20. Newcastle upon Tyne: Cambridge Scholars Press.Suche in Google Scholar

Ajello, Roberto. 2011. Anthroponyms in the Gizey society (N-E Cameroon). In Maria Frascarelli (ed.), A country called Somalia: Culture, language and society of a vanishing state, 13–31. Torino: L’Harmattan.Suche in Google Scholar

Ajello, Roberto & Antonino Melis. 2008. Dictionnaire gizey-français, suivi d’une liste lexicale français-gizey. Pisa: Edizioni ETS.Suche in Google Scholar

Akita, Kimi. 2021. A typology of depiction marking: The prosody of Japanese ideophones and beyond. Studies in Language 45(4). 865–886. https://doi.org/10.1075/sl.17029.aki.Suche in Google Scholar

Ameka, Felix K. 1992. Interjections: The universal yet neglected part of speech. Journal of Pragmatics 18. 101–118. https://doi.org/10.1016/0378-2166(92)90048-G.Suche in Google Scholar

Ameka, Felix K. 2001. Ideophones and the nature of the adjective word class in Ewe. In F. K. Erhard Voeltz & Christa Kilian-Hatz (eds.), Ideophones, 25–48. Amsterdam: Benjamins.10.1075/tsl.44.04ameSuche in Google Scholar

Childs, George Tucker. 1994. African ideophones. In Hinton Leanne, Nichols Johanne & J. Ohala John (eds.), Sound symbolism, 178–209. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.10.1017/CBO9780511751806.013Suche in Google Scholar

Clark, Herbert H. & Richard J. Gerrig. 1990. Quotations as demonstrations. Language 66(4). 764–805. https://doi.org/10.2307/414729.Suche in Google Scholar

De Brabanter, Philippe. 2017. Why quotation is not a semantic phenomenon, and why it calls for a pragmatic theory. In Ilse Depraetere & Raphael Salkie (eds.), Semantics and pragmatics: Drawing a line, 227–254. Cham: Springer International Publishing.10.1007/978-3-319-32247-6_14Suche in Google Scholar

De Dominicis, Amedeo. 2006. Tonal patterns of Gizey. In Amedeo De Dominicis (ed.), Undescribed and endangered languages: The preservation of linguistic diversity, 60–163. Newcastle upon Tyne: Cambridge Scholars Press.Suche in Google Scholar

De Dominicis, Amedeo. 2008. Phonological sketch of Gizey. Studi Linguistici e Filologici Online 6. 1–78.Suche in Google Scholar

Dingemanse, Mark. 2012. Advances in the cross-linguistic study of ideophones. Language and Linguistics Compass 6(10). 654–672. https://doi.org/10.1002/lnc3.361.Suche in Google Scholar

Dingemanse, Mark. 2014. Making new ideophones in Siwu: Creative depiction in conversation. Pragmatics and Society 5(3). 384–405. https://doi.org/10.1075/ps.5.3.04din.Suche in Google Scholar

Dingemanse, Mark. 2019. Ideophone’ as a comparative concept. In Kimi Akita & Prashant Pardeshi (eds.), Ideophones, mimetics, and expressives, 13–33. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.10.1075/ill.16.02dinSuche in Google Scholar

Dingemanse, Mark. 2023. Ideophones. In Eva van Lier (ed.), The Oxford handbook of word classes, 466–476. Oxford: Oxford University Press.10.1093/oxfordhb/9780198852889.013.15Suche in Google Scholar

Doke, Clement Martin. 1935. Bantu linguistic terminology. London: Longmans.Suche in Google Scholar

Gaffuri, Luigi, Antonino Melis & Valerio Petrarca. 2019. Tessiture dell’identità. Lingua, cultura e territorio dei Gizey tra Camerun e Ciad. Napoli: Liguori Editore.Suche in Google Scholar

Guitang, Guillaume. 2022. Frozen reduplication in Gizey: Insights into analogical reduplication, phonological and morphological doubling in Masa. Morphology 32. 121–151. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11525-021-09389-3.Suche in Google Scholar

Guitang, Guillaume. 2024. A morphosyntactic description of Gizey (Chadic). Brussels: Université libre de Bruxelles PhD dissertation.Suche in Google Scholar

Guitang, Guillaume, Ousmanou & Pierre Davounoumbi. 2022. Microvariation in nominal plurality in Northern Masa. Journal of African Languages and Literatures 3. 86–105. https://doi.org/10.6093/jalalit.v3i3.9145.Suche in Google Scholar

Güldemann, Tom. 2008. Quotative indexes in African languages. A synchronic and diachronic survey. Berlin, New York: De Gruyter Mouton.10.1515/9783110211450Suche in Google Scholar

Haiman, John. 2018. Ideophones and the evolution of language. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.10.1017/9781107706897Suche in Google Scholar

Heath, Jeffrey. 2019. The dance of expressive adverbials (“ideophones”) in Jamsay (Dogon). Folia Linguistica 53(1). 1–24. https://doi.org/10.1515/flin-2019-2002.Suche in Google Scholar

Hinton, Leanne, Johanna Nichols & John Ohala. 1995. Introduction: Sound-symbolic processes. In Johanna Nichols, John J. Ohala & Leanne Hinton (eds.), Sound symbolism, 1–12. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.10.1017/CBO9780511751806.001Suche in Google Scholar

Ibarretxe-Antuñano, Iraide. 2017. Basque ideophones from a typological perspective. Canadian Journal of Linguistics/Revue canadienne de linguistique 62(2). 196–220. https://doi.org/10.1017/cnj.2017.8.Suche in Google Scholar

Johansson, Niklas Erben, Andrey Anikin, Gerd Carling & Holmer Arthur. 2020. The typology of sound symbolism: Defining macro-concepts via their semantic and phonetic features. Linguistic Typology 24(2). 353–310.10.1515/lingty-2020-2034Suche in Google Scholar

Jong, Nicky de. 2001. The ideophone in Didinga. In Erhard F. K. Voeltz & Christa Kilian-Hatz (eds.), Ideophones, 121–138. Amsterdam/Philadelphia: John Benjamins Publishing Company.10.1075/tsl.44.11jonSuche in Google Scholar

Kabore, Raphaël. 1993. Contribution à l’étude de l’idéophonie (CEROI-Paris. Travaux et documents (série linguistique) 21). Paris: Institut des langues et civilisations orientales.Suche in Google Scholar

Kunene, Daniel P. 1978. The ideophone in Southern Sotho (Marburger Studien Zur Afrika- Und Asienkunde A11), vol. 11. Berlin: Dietrich Reimer.Suche in Google Scholar

Ladefoged, Peter & Keith Johnson. 2011. A course in phonetics, 6th edn. Boston: Cengage Learning.Suche in Google Scholar

Lier, Eva van & Jan Rijkhoff. 2013. Flexible word classes in linguistic typology and grammatical theory. In Jan Rijkhoff & Eva van Lier (eds.), Flexible word classes: Typological studies of underspecified parts of speech. Oxford University Press.10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199668441.003.0001Suche in Google Scholar

Lockwood, Gwilym & Mark Dingemanse. 2015. Iconicity in the lab: A review of behavioral, developmental, and neuroimaging research into sound-symbolism. Frontiers in Psychology 6. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2015.01246.Suche in Google Scholar

Luuk, Erkki. 2010. Nouns, verbs and flexibles: Implications for typologies of word classes. Language Sciences (Oxford) 32(3). 349–365. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.langsci.2009.02.001.Suche in Google Scholar

McLean, Bonnie. 2021. Revising an implicational hierarchy for the meanings of ideophones, with special reference to Japonic. Linguistic Typology 25(3). 507–549. https://doi.org/10.1515/lingty-2020-2063.Suche in Google Scholar

Melis, Antonino. 2006. Dictionnaire Masa-français: dialectes gumay et ɦaara (Tchad). Pisa: Edizioni Plus.Suche in Google Scholar

Meta Platforms. 2023. WhatsApp messenger. Erlang: WhatsApp Inc. Available at: https://www.whatsapp.com/.Suche in Google Scholar

Newman, Paul. 1968. Ideophones from a syntactic point of view. JWAL 2. 107–117.Suche in Google Scholar

Newman, Paul. 1990. Nominal and verbal plurality in Chadic. Dordrecht: Foris publications.10.1515/9783110874211Suche in Google Scholar

Newman, Paul. 2001. Are ideophones really as weird and extra-systematic as linguists make them out to be? In F. K. Erhard Voeltz & Christa Kilian-Hatz (eds.), Ideophones (Typological Studies in Language), 251–258. Amsterdam/Philadelphia: John Benjamins Publishing Company.10.1075/tsl.44.20newSuche in Google Scholar

Nuckolls, Janis B., Elizabeth Nielsen, Joseph A. Stanley & Roseanna Hopper. 2016. The systematic stretching and contracting of ideophonic phonology in Pastaza Quichua. International Journal of American Linguistics 82(1). 95–116. https://doi.org/10.1086/684425.Suche in Google Scholar

Roberts, James & Albert Camus Soulokadi. 2019. On ideophones in Musey. In Henry Tourneux & Yvonne Treis (eds.), Topics in Chadic linguistics X – Papers from the 9th biennial international colloquium on the Chadic languages, Villejuif, September 7–8, 2017, 215–226. Koln: Rüdiger Köppe Verlag.Suche in Google Scholar

SIL Language Technology. 2021. Phonology assistant. Available at: https://software.sil.org/phonologyassistant/.Suche in Google Scholar

SIL Language Technology. 2002. SIL FieldWorks language explorer. Available at: https://software.sil.org/fieldworks/.Suche in Google Scholar

Skopeteas, Stavros, Ines Fieldler, Sam Hellmuth, Anne Schwarz, Ruben Stoel, Gisbert Fanselow, Caroline Féry & Manfred Krifka. 2006. Questionnaire on information structure: Reference manual (Interdisciplinary Studies on Information Structure), vol. 4. Potsdam: Universitätverlag Potsdam.Suche in Google Scholar

Wilkins, David P. 1992. Interjections as deictics. Journal of Pragmatics 18(2). 119–158. https://doi.org/10.1016/0378-2166(92)90049-H.Suche in Google Scholar

© 2025 the author(s), published by De Gruyter, Berlin/Boston

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Frontmatter

- Articles

- The evolution of the Mawes Aas’e (Omotic-Mao) pronouns: evidence for Omotic Lineage

- The canar-yi in the coal mine: The loss of yi in Zulu reduplication

- Ideophones in Gizey grammar

- An overview of Bamum phonology and orthography, with an additional focus on character and word frequencies in recent poetry

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Frontmatter

- Articles

- The evolution of the Mawes Aas’e (Omotic-Mao) pronouns: evidence for Omotic Lineage

- The canar-yi in the coal mine: The loss of yi in Zulu reduplication

- Ideophones in Gizey grammar

- An overview of Bamum phonology and orthography, with an additional focus on character and word frequencies in recent poetry