Abstract

While the history of the Bamum language has been well documented, the particulars of its phonology and orthography have received fragmentary treatment. Our contribution to the literature is an attempt to synthesize from the works that have gone before, to pull together disparate threads that have arisen from the influences of German, French, and English traditions. We discuss in turn phonology (noting in particular discrepancies in the accounting for the vowel inventory between sources), analysis of the writing system, and frequency distribution of characters and words. Discussion on historical phonology might shed some light on the development of orthographic principles while the preliminary exploration of the observed statistical patterns of the latest phase of the script, known as A ka u ku mfɛmfɛ, would be useful for future reference. We also offer indications for directions for future research on a wider scale, that would incorporate corpus studies of both the Bamum language and the invented Shümom language that also uses the Bamum script.

1 Introduction

Bamum language (ISO 639-3 code: bax) is a Bantoid language spoken in the Western province of Cameroon. It is classified as Bamum < Nun < Grassfield < Bantoid < Benue-Congo < Volta-Congo < Atlantic-Congo within the Niger-Congo macrofamily. The language is also known as Bamoum, Bamun, or Bamoun and is called shüpaməm in vernacular. The number of speakers was estimated as 420,000 in 2005 (Ethnologue 2024) and given the average yearly Cameroon population growth of 2.5 per cent (Census data 2005) can be estimated as over 600,000 people in 2022.

The Bamum people live predominantly in the Noun department with the capital in Foumban being the historical capital of the Bamum kingdom; see the map in Figure 1. The territory is situated between 10°30′ and 11°10′ East longitude and between 5° and 6° North latitude (Dugast and Jeffreys 1950: 1). Natural borders include the Vi River in the north, the Mbam River in the east, and the Noun River in the west and south-west (cf. Galitzine-Loumpet 2011). The Bamendjing Reservoir is located about thirty kilometers west of Foumban.

Approximate location of the Bamum people in Cameroon.

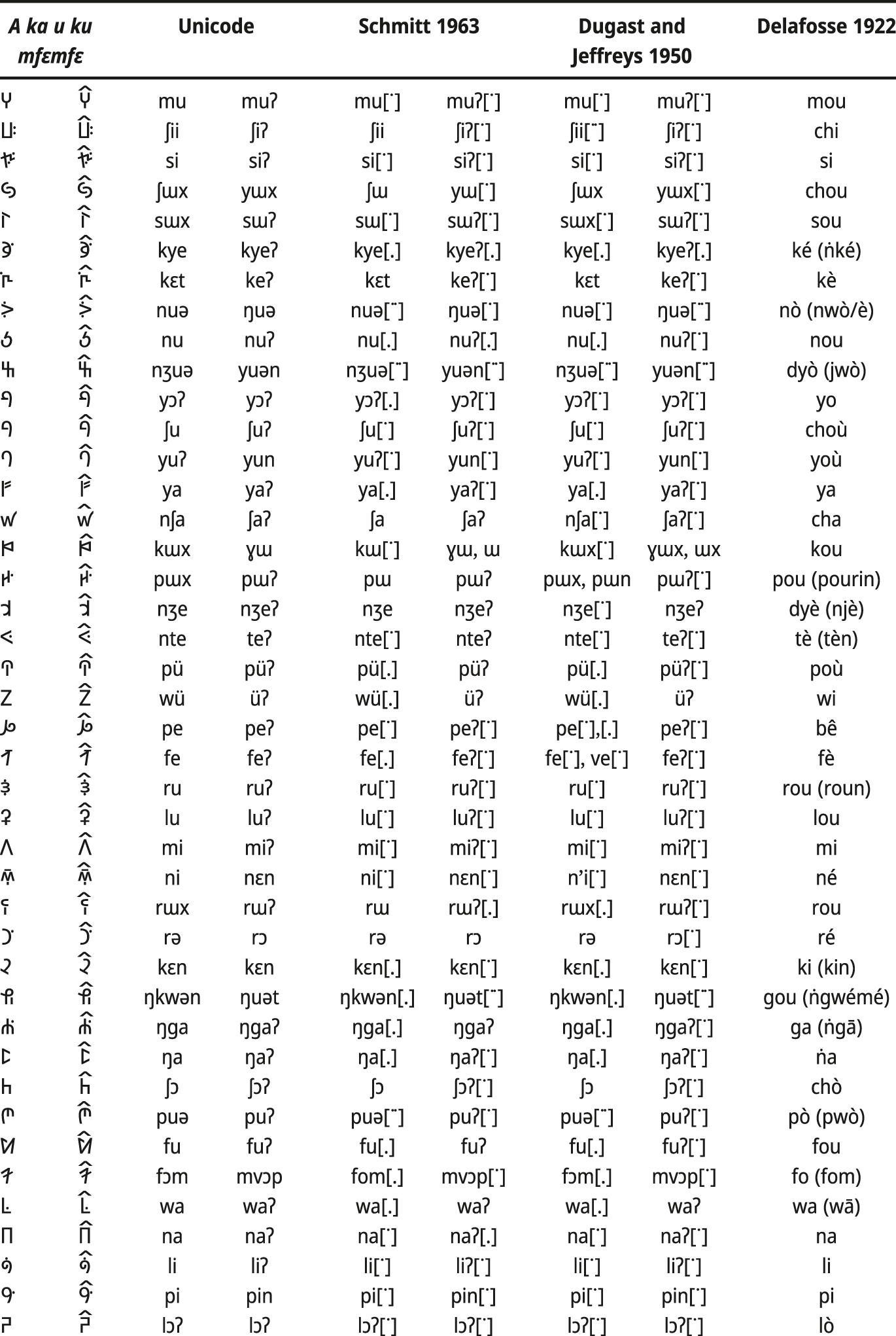

The Bamum language is best known from the indigenous writing system created in 1896–1918 by the local leader (mfɔn) Ibrahim Njoya (c. 1860–1933) often referred to as King or Sultan Njoya. The writing system underwent a rapid evolution from a pictographic script to a nearly alphabetic one within a rather short period of time (Dugast and Jeffreys 1950; Schmitt 1963). Characters from the last development stage are shown in Table 1. This script is known as A ka u ku mfɛmfɛ ‘new a-ka-u-ku’, from the names of the first four syllabic signs (Dugast and Jeffreys 1950). The first stage is known as lewa ‘book’ (about 500 signs), the second one is mbima ‘mixed’ (437 symbols, ca. 1900), subsequent stages were named by the first syllables: nyi nyi nʃa mfɯʔ (381 symbols, before 1906), rii nyi nʃa mfɯʔ (295 symbols, ca. 1907–1908), rii nyi mfɯʔ mɛn (205 symbols, ca. 1907–1908), a ka u ku (80 symbols, after 1910). These stages are traditionally referred to by the Roman letters A to F, with the final, A ka u ku mfɛmfɛ, known as stage G (Dugast and Jeffreys 1950; Schmitt 1963). In this last version from 1918, the shapes of the 80 symbols from stage F were simplified (Dugast and Jeffreys 1950: 30). The first accounts on the script were published in 1907 by Göhring (1907a, 1907b), a Swiss missionary from Basel. For readers’ convenience, we list the sources about the Bamum writing system in the Appendix. The role of the script is analyzed in the Cameroonian (Schumann 2019; Zang Zang 2012) and a wider African context (Mazrui and Mazrui 1992; Nganang 2015; Tuchscherer 2007; Unseth 2011). The script is considered an important component of the Bamum identity (Battestini 2004). In October 2009, the modern Bamum script (i. e., A ka u ku mfɛmfɛ) became part of the Unicode standard (version 5.2) and historical logograms were added to Unicode in October 2010 (version 6.0).

Characters of the modern Bamum script A ka u ku mfɛmfɛ.

Beyond the studies devoted to Njoya’s writing system, especially those by Dugast and Jeffreys (1950) and a three-volume magnum opus by Schmitt (1963), the materials on the Bamum language are rather scarce. To our knowledge, the situation has not changed significantly compared to 2012 when Abdoulaye Nchare wrote that “Shupamem is one of the least studied of the Grassfields Bantu languages at least in terms of studies explicitly dealing with syntactic phenomena” (Nchare 2012: 15). The Bamum language was included in Sigismund Koelle’s Polyglotta Africana (1854) as IX.A.8. Bámom. The phonology of Bamum was analyzed in detail by Ward (1938). The present-day status of the language is reflected in the book by Matateyou (2002) from the Parlons series, in Abdoulaye Nchare’s works including his PhD dissertation (see Nchare 2012 and references therein), and in Solange Pawou Molu’s PhD dissertation (Pawou Molu 2018). Note that as of today we have not been able to locate a Bamum dictionary of any significant size beyond word lists given by Koelle (1854), Schmitt (1963), and Matateyou (2002). A parallel list of more than 400 words in French, Bamum, and Shümom (a secret language invented by Njoya) is given by Dugast (1950). The Bibliography of Cameroonian languages merely listed a score of titles about the Bamum language as of 1993 (Barreteau et al. 1993).

We hope our modest analysis presented here will be a contribution towards studies of the Bamum language and hope that it triggers interest in the language with prospects of further larger-scale research in this direction. We begin with a discussion on the Bamum phonology in Section 2 including in particular some historical accounts, then proceed to a detailed analysis of the writing system in Section 3 and report some observations relevant to orthographic principles reflecting modern practices of the Bamum script usage. In Section 4, we analyze the frequency distribution of characters and the most frequent words, based on a recently published collection of poems by Samuel Calvin Gbetnkom, a modern Bamum poet (Gbetnkom 2022). Conclusions are given in Section 5.

2 Remarks on phonology

The first detailed study of the Bamum phonology was made back in 1938 by Ida Ward. Later on, the relevant analysis was included in works by Dugast and Jeffreys (1950) and Schmitt (1963). Separate discussions on this issue are found in studies from the last two decades (e.g., Matateyou 2002; Nchare 2012; Pawou Molu 2018).

There is a significant discrepancy on the vowel inventory in Bamum according to different authors. Ward (1938) considers eight vowels /a, ɛ, ə, i, ɔ, o, ø, ɯ/, with a remark that /ø/ represents “a front rounded vowel between close and half-close: it was often heard as ü” and that /o/ “is about half-way between Cardinal o and u”. Dugast and Jeffreys (1950) and Schmitt (1963) list nine vowels and the set is slightly different: /a, ɛ, e, ə, i, ɔ, u, ü, ɯ/. Additionally, Schmitt (1963: 49) notes that phoneme /o/ is foreign to Bamum. Matateyou (2002: 47) reports seven vowels only /a, ɛ, ə, i, ɔ, u, ʉ/, with the latter standing for [ɯ] (i.e., close back unrounded and not IPA close central rounded vowel) in accordance with the General Alphabet of Cameroon Languages (Tadadjeu and Sadembouo 1979). However, in the book itself a set of ten vowels /a, ɛ, e, ə, i, ɔ, o, u, ü, ʉ/ is used in text written in Bamum (Matateyou 2002: 37–38). The same set of ten vowels is listed by Nchare (2012: 39) as /a, ɛ, e, ə, i, ɔ, o, u, y, ɯ/. The close front rounded vowel [y] is transcribed further in the present article using a more traditional notation /ü/ leaving the notation /y/ for the palatal approximant IPA [j]. To round out the complexity, we note that Solange Pawou Molu (2018) in her PhD thesis uses the same set of ten vowels but with ʉ for ü/y and preserving ɯ with its traditional value.

The summary of vowels and their notation used in the present work is presented in Table 2.[1]

A simplified scheme of Bamum vowels.

| Front | Central | Back | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unrounded | Rounded | Unrounded | Rounded | ||

| Close | i | ü | ɯ | u | |

| Mid | e | ə | o | ||

| Open | ɛ | a | ɔ | ||

Vowels in Bamum can be short and long and can also form diphthongs. Diphthongs of iV and uV kinds result in palatalization and labialization of the preceding onset consonants, respectively (Nchare 2012: 42). The latter can be reflected in writing as wV: puə̀ or pwó ‘arm, hand’.

Similarly to other related Grassfield languages, Bamum has a complex tonal system, in which the following four tones can be identified (Nchare 2012: 63): high (H), low (L), rising (LH), and falling (HL). Of those, high and low tones might be considered the two principal tones (Matateyou 2002: 39; Schmitt 1963: 39). The role of tones in the Bamum grammar was recently analyzed by Magdalena Markowska in her M.A. thesis (Markowska 2020). Details on tone marking are discussed below in this section.

Bamum is rich in consonants. Three major groups are plosives /p, b, t, d, k, g, kp, gb, ʔ/ (with /ʔ/ denoting the glottal stop), fricatives /f, v, s, z, ʃ, ʒ, ɣ/, and nasal consonants /m, n, ɲ, ŋ/. The graphic representation of /ɲ/ is traditionally ny. Other consonants are a lateral /l/, a rolled /r/, and semivowels /w, y/. Matateyou (2002: 37–38) uses gh for /ɣ/ and sh for /ʃ/ and additionally lists ɓ for /β/ being the first consonant in Spanish vaca ‘cow’. Nchare (2012: 44) includes /β/ and adds a labiodental nasal /ɱ/. There are also prenasalized consonants /mb, mf, mv, nd, nt, ns, nz, nʃ, nʒ, nw, ny, ŋk, ŋg, ŋkp, ŋgb, ŋm/ (cf. Nchare 2012: 45).

It should be noted that word-finally “a light velar fricative” [x] was reported to follow back close vowels (Ward 1938). This feature was reproduced in writing and was later adopted by Dugast and Jeffreys (1950). It is not followed though either by Schmitt (1963) or later authors (Matateyou 2002; Nchare 2012; Pawou Molu 2018).

Palatalization can occur in /k/ before the front vowels /e, ɛ, i/ that is reproduced as ky in writing (Ward 1938). The rules for the palatalization are not straightforward though, cf. kyɛ́t ‘arrow’ and kɛ́t ‘barrel’ (Matateyou 2002: 159). This might be related to word etymology: Ward (1938: 425) provides an example of ŋkyɛ ‘water’ versus ɣakɛri ‘big’ derived from kɛri, a form of kɯt.

Although the sounds above have been indicated as phonemic, there is a chance that some of these may be allophones rather than independent phonemes.

In the remainder of this section, we present an analysis of historical changes in vowels inspired by Nchare’s observations (2012: 16–23). We select twenty words having a single-character representation in the A ka u ku mfɛmfɛ script, see Table 3. Their pronunciation is given according to Koelle (1854), Delafosse (1922), Ward (1938), Dugast and Jeffreys (1950), Schmitt (1963), Matateyou (2002), and Nchare (2012). The two latter sources can be considered modern Bamum. The data by Dugast and Jeffreys (1950) and Schmitt (1963) differ only slightly and mostly in tones.

Historical changes in some Bamum words represented by a single character in A ka u ku mfɛmfɛ.

-

*The last phonetic value corresponds to modern Bamum as evidenced by Matateyou (2002) and Nchare (2012).

Being historically dispersed and therefore written in different linguistic models, all the quoted sources are rather inconsistent in the notation of vowels. Koelle (1854: vi) uses ẹ for /ɛ/, ọ for /ɔ/, and n· for /ŋ/. The macron ( ˉ ) indicates long vowels and the acute ( ˊ ) is used to mark ‘accent’, though whether Koelle was referring to stress or tone is unclear.

Delafosse (1922) uses è for /ɛ/, ò for /ɔ/, é for /e/, and ṅ for /ŋ/. Differences between ou and où are unclear: both correspond to modern /u/ and /ɯ/. Examples include choù for the modern character  ʃu and chou for modern

ʃu and chou for modern  ʃɯ but soù for modern

ʃɯ but soù for modern  suu and sou for modern

suu and sou for modern  sɯ as well as lou for

sɯ as well as lou for  lu and nou for

lu and nou for  nu but yoù for

nu but yoù for  yuʔ. In one instance, poù corresponds to modern /ü/ as in

yuʔ. In one instance, poù corresponds to modern /ü/ as in  pü ‘we’.

pü ‘we’.

The notations by Ward (1938) mostly correspond to modern practices, except for the previously mentioned /o/ versus /u/ and /ø/ versus /ü/. Schmitt (1963: 50–51) suggested that the chosen values /o/ and /ø/ could be due to peculiarities of the informant’s pronunciation. Nchare (2012: 22) suggests that Ward’s data might represent a specific dialect while a dozen pages earlier no dialectal variations are mentioned (Nchare 2012: 10); no known dialect is independently reported by the Ethnologue data (2024). In what follows, we assume the phonetic values to be /u/ for Ward’s o and /ü/ for Ward’s ø.

Dugast and Jeffreys (1950) and Schmitt (1963) follow the convention of using the set of nine vowels /a, ɛ, e, ə, i, ɔ, u, ü, ɯ/ and additionally mark tones inserting after the respective words [.] for the low tone, [˙] for the high tone, and the combinations of these marks for more complicated tonal contours.

Matateyou (2002) and Nchare (2012) use ten vowels /a, ɛ, e, ə, i, ɔ, o, u, ü, ɯ/ but the notation differs for the latter two, as reported above: ʉ for /ɯ/ (Matateyou 2002) and y for /ü/ (Nchare 2012). Both sources use the grave accent ( ˋ ) for the low tone, the acute ( ˊ ) for the high tone, and the combinations of these marks in the form of a caron ( ˇ ) for the rising tone and a circumflex ( ˆ ) for the falling tone. Note that the issue of tone marking in practical orthography is rather complicated (cf. Bird 1999, 2001; Bernard et al. 2002; Lüpke 2011). In indigenous African scripts created since the 19th century, tones are mostly unmarked (cf. Rovenchak and Buk 2020; Daniels 2023), with prominent exceptions exemplified by the Bassa Vah and Nko alphabets.

Rows 11 and especially 12 in Table 3 suggest that the reading of Ward’s o should indeed be identified with /u/ rather than /o/. Additional examples include ń·gub – ŋgop – ŋgùp ‘skin’ and mbó – ŋgox – ŋgù ‘town, country’, where the first word stands for Koelle’s data, the middle corresponds to Ward’s data, and the last one is the modern phonetic value.

Certain examples demonstrate stable phonetic values: /a/ in rows 4, 7, and 8 (first vowel); /o/ in row 1; /i/ in row 13; /u/ in rows 6 and 8.

From Nchare’s data (2012: 21) we can draw the following vowel shifts:

[ɔ] → [u], [o]/[u] → [ü], [a] → [ɛ]

All of them correspond to vowel raising (movement “up” according to Table 2 considering that [ɛ] and [ɔ] are actually open-mid vowels). Additionally to these shifts we have also discovered an [e] → [i] transition with the same direction. It is also exemplified by the word Ɲiɲi ‘God’ given as nyḗnye by Koelle (1854).

Some other potential vowel shifts based on historical data as shown in Table 3 are listed in Table 4. The time given corresponds to the recorded data and suggests the upper estimation. Delafosse’s records often quote also Bamum character readings from 1907, so they likely represent the situation with the Bamum language at the turn of the 20th century.

Provisional historical vowel shifts in Bamum.

| Change | Time | Table 3 row |

|---|---|---|

| ɛː – aː | Before 1922 | 2 |

| a – ɛ | Before 1922 | 3, 19 |

| an – ɛn | Between 1922 and 1950 | 5 |

| a – ə | Between 1922 and 1950 | 8 |

| oː – u – ü | Before 1922, then before 1938 | 9 |

| oŋ – u | Before 1922 | 11 |

| e – i | Before 1922 | 16 |

| ūa – uɔ – ? – uə – uə/uo | Before 1922, then before 1950 | 15 |

| ūa – ? – uɔ – uə – uə/uo | Before 1938, then before 1950 | 18 |

We do not have sufficient evidence to discuss the evolution of /ɯ/. The reason is that such a phoneme is not distinguished by Koelle (1854) and neither is it possible to identify the respective notation properly in the data by Delafosse (1922). The following relevant lineages were discovered: ákōt – kwɯt – kùt ‘leg’, átot – tɯt – tɯ̀t ‘ear’, ndṣū́ – (yɯ) – njɯ́ ‘I eat’, ń·gọ – ŋgɯə – ŋgɯ́ə̀ ‘leopard’. In these examples, the first word corresponds to Koelle (1854), the second one is by Ward (1938), and the third one is the modern version from Matateyou (2002) or Nchare (2012).

3 The A ka u ku mfɛmfɛ script

In Bamum, words are mostly one or two syllables. The syllables have the structure (C)V(C), where the final consonant is either nasal /m, n, ŋ/ or voiceless /p, t/. A syllable can end in the glottal stop /ʔ/, which might originate from final /k/ (Schmitt 1963, p. 57; Nchare 2012, p. 48). As we have mentioned in the previous section, consonants can be prenasalized. Vowel-only words are not uncommon for the language and include in particular frequently used pronouns, see in particular Table 8.

Creating a writing system that would reproduce such a phonotactically complex structure is a tricky task. As shown in Table 1, the ultimate stage of the Bamum script might seem to be syllabic at first glance: of 80 characters in total, there is only one purely alphabetic character  for /m/, a few characters for closed syllables and an overwhelming majority of open-syllable characters. It appears, however, that the system functioned quite efficiently given that it was governed by several general and specific rules as described below.

for /m/, a few characters for closed syllables and an overwhelming majority of open-syllable characters. It appears, however, that the system functioned quite efficiently given that it was governed by several general and specific rules as described below.

The most productive approach to extend a syllable inventory is to apply diacritical marks; just compare the dakuten (゛) and handakuten (゜) marks in the Japanese kana. One of the diacritics in the Bamum script is called kɔʔndɔn; it looks like a circumflex mark over characters. Its main function is to mark a final glottal stop but certain unpredictable syllable changes are also attested (see Tables 5 and A in the Appendix). In five cases, kɔʔndɔn differentiates between low and high tone, all are for Cɛn syllables:  tɛ̀n /

tɛ̀n /  tɛ́n,

tɛ́n,  kɛ̀n /

kɛ̀n /  kɛ́n,

kɛ́n,  mɛ̀n /

mɛ̀n /  mɛ́n,

mɛ́n,  rɛ̀n /

rɛ̀n /  rɛ́n.

rɛ́n.

The second diacritical mark is called tukwɛntis; it looks like a horizontal line over a character. It mostly functions as a “killer stroke” removing vowels from syllables (see Table 5). This is similar to the virāma mark ( ् ) in Brahmi-derived scripts or sukūn ( ـْـ ) in ḥarakāt (system of short vowel marks in the Arabic orthography). Note that, to our knowledge, symbols with such a function are not attested in known syllabaries.

Representation of syllables in A ka u ku mfɛmfɛ. Gbetnkom (2022) innovations are highlighted in red on the gray background in the respective cells.

It might seem that the diacritics suffice to represent the entire variety of Bamum syllables in an almost alphabetic manner, by combining consonants obtained via the killer stroke with stand-alone vowels (cf. Table 5). But kɔʔndɔn and tukwɛntis are just recent additions into the script. During previous development stages, other strategies were developed, and they survived to the current A ka u ku mfɛmfɛ writing system.

The complex nature of the Bamum script can be exemplified by principles governing representation of syllables not covered by the set of Table 1 (with additions provided by diacritical marks). The main way to represent such a syllable (of the shape C1V1) is to write it as a combination C1V2+C2V1. For instance, in a quite regular manner Cɯ syllables are written as Cu+ɣɯ. Often, the combinations Ci+ü are used to represent Cü.

According to Dugast and Jeffreys (1950: 32) and Schmitt (1963: 48), the vowels /ɔ/ and /ə/ were not differentiated in the Bamum script. Certain observed phonotactic restrictions might be helpful in guessing word readings. For instance, /ɛ/ and /wə/ do not occur in open syllables, /ɔ/ is always /ɔʔ/ in monosyllabic words, except ɔ ‘yes’, tɔɔ ‘to pierce’, ṁgbɔ ‘corn’ (Schmitt 1963: 57).

Diphthongs are mostly written as consecutive vowels:  pɯən = pɯ+ə+n ‘people’,

pɯən = pɯ+ə+n ‘people’,  puaʔ = puə+aʔ ‘is’,

puaʔ = puə+aʔ ‘is’,  ʃie = ʃii+i+e ‘name (verb)’. Some characters contain diphthongs in syllable nucleus:

ʃie = ʃii+i+e ‘name (verb)’. Some characters contain diphthongs in syllable nucleus:  nue ‘drink’,

nue ‘drink’,  rie ‘say’. Such reading is preserved in polysyllabic words, e.g.,

rie ‘say’. Such reading is preserved in polysyllabic words, e.g.,  mbirien = m+pi+i+rie+n ‘antelope’.

mbirien = m+pi+i+rie+n ‘antelope’.

Word-final /p/ is represented by  pɯ:

pɯ:  ndap = n+ndaa+pɯ ‘box, house’,

ndap = n+ndaa+pɯ ‘box, house’,  nʒap = n+nʃa+pɯ ‘meat’,

nʒap = n+nʃa+pɯ ‘meat’,  pap = pa+a+pɯ ‘wide’. One character with kɔʔndɔn reads

pap = pa+a+pɯ ‘wide’. One character with kɔʔndɔn reads  mvɔp ‘dust, gunpowder’ (Dugast 1950). It is worth noting that the use of epenthetic (“dummy”) vowels to represent word- and syllable-final consonants is typical of syllabic scripts, e.g., -e in the Cypriot syllabary as in

mvɔp ‘dust, gunpowder’ (Dugast 1950). It is worth noting that the use of epenthetic (“dummy”) vowels to represent word- and syllable-final consonants is typical of syllabic scripts, e.g., -e in the Cypriot syllabary as in  ka-re (read right-to-left) for the Ancient Greek γᾰ́ρ ‘for, since’ (cf. Gnanadesikan 2011) or the use of katakana symbols of the -u [-ɯ] series to represent foreign words in Japanese (デスク de-su-ku for ‘desk’ or ホテル ho-te-ru for ‘hotel’).

ka-re (read right-to-left) for the Ancient Greek γᾰ́ρ ‘for, since’ (cf. Gnanadesikan 2011) or the use of katakana symbols of the -u [-ɯ] series to represent foreign words in Japanese (デスク de-su-ku for ‘desk’ or ホテル ho-te-ru for ‘hotel’).

Both syllable-final /m, n/ and syllable-initial /m, n/ followed by consonants (forming consonant clusters, which are treated as prenasalized consonants) are represented by  and

and  , respectively:

, respectively:  mgbie = m+pi+i+e ‘woman’,

mgbie = m+pi+i+e ‘woman’,  nsɛn = n+si+e+n ‘forest’,

nsɛn = n+si+e+n ‘forest’,  lum = lu+m ‘year’. The character

lum = lu+m ‘year’. The character  is also used for /ŋ/ before /k, g/:

is also used for /ŋ/ before /k, g/:  ŋkye = n+kye+e ‘salt’,

ŋkye = n+kye+e ‘salt’,  ŋgup = n+ku+u+pɯ ‘skin’ (Dugast 1950). Final /m/ and /n/ are intrinsic to several Bamum characters, see the last column in Table 5.

ŋgup = n+ku+u+pɯ ‘skin’ (Dugast 1950). Final /m/ and /n/ are intrinsic to several Bamum characters, see the last column in Table 5.

There was also a rather curious approach to marking the final /t/ using  rɯ, first attested during stage C and which became standard during stage F (Schmitt 1963: 151–155). It might originate from an implicit pronoun ‘your’, e.g., nʒɯt ‘sheep (sg.)’ versus nʒɯrɯ ‘your sheep (sg.)’. The version in the Bamum script would be

rɯ, first attested during stage C and which became standard during stage F (Schmitt 1963: 151–155). It might originate from an implicit pronoun ‘your’, e.g., nʒɯt ‘sheep (sg.)’ versus nʒɯrɯ ‘your sheep (sg.)’. The version in the Bamum script would be  ʃɯ+rɯ (Schmitt 1963: 155). This method can be occasionally applied also word-internally:

ʃɯ+rɯ (Schmitt 1963: 155). This method can be occasionally applied also word-internally:  mbuətnə = m+puə+ɔ+rɯ+na+ɔ ‘blessing’ (Dugast 1950: 246),

mbuətnə = m+puə+ɔ+rɯ+na+ɔ ‘blessing’ (Dugast 1950: 246),  fɯtmum = fɯ+ɣɯ+rɯ+mɔ+m ‘Tuesday’,

fɯtmum = fɯ+ɣɯ+rɯ+mɔ+m ‘Tuesday’,  yetnʒuə = i+e+rɯ+nʒuə ‘Friday’ (Dugast 1950: 250). In the list of words given by Dugast (1950), only two words use different strategy for word-final /t/:

yetnʒuə = i+e+rɯ+nʒuə ‘Friday’ (Dugast 1950: 250). In the list of words given by Dugast (1950), only two words use different strategy for word-final /t/:  mbit = m+pi+i+ti ‘excrement’ and

mbit = m+pi+i+ti ‘excrement’ and  pit = pi+ti ‘war’ (cf. also Schmitt 1963: 155) but the same ending is again represented by

pit = pi+ti ‘war’ (cf. also Schmitt 1963: 155) but the same ending is again represented by  rɯ in

rɯ in  laʔpit = laʔ+pi+rɯ ‘the morning star’ (Dugast 1950: 244). Three characters possess intrinsic final /t/:

laʔpit = laʔ+pi+rɯ ‘the morning star’ (Dugast 1950: 244). Three characters possess intrinsic final /t/:  kɛt used as a suffix,

kɛt used as a suffix,  ŋuət ‘body’, and

ŋuət ‘body’, and  tɛt ‘three’.

tɛt ‘three’.

As non-prenasalized voiced stops /b, d, g, gb/ are rarely found in syllable onsets in Bamum, no separate characters were invented to represent them. Instead, the respective voiceless counterparts are used:  bɯa = pu+a ‘that (relative pronoun)’,

bɯa = pu+a ‘that (relative pronoun)’,  gbayi = kpa+a+i ‘lion’,

gbayi = kpa+a+i ‘lion’,  geloba = kye+lɔʔ+pa ‘camel’ (Dugast 1950); the latter word is given as keloba by Schmitt (1963: 695). From examples by Oumaru Nchare (c. 2005) and Matateyou (2015: 142) one can derive a principle to represent voiced consonants as follows: CvoicelessV1+V1 = CvoicedV1, so that adding a vowel-only character to a syllable with the respective inherent vowel changes the syllable’s onset to the voiced consonant, e. g.,

geloba = kye+lɔʔ+pa ‘camel’ (Dugast 1950); the latter word is given as keloba by Schmitt (1963: 695). From examples by Oumaru Nchare (c. 2005) and Matateyou (2015: 142) one can derive a principle to represent voiced consonants as follows: CvoicelessV1+V1 = CvoicedV1, so that adding a vowel-only character to a syllable with the respective inherent vowel changes the syllable’s onset to the voiced consonant, e. g.,  ʃu /

ʃu /  ʒu =

ʒu =  ʃu +

ʃu +  u. It is not clear, however, to what extent this rule has a universal nature. In particular, numerous examples by Dugast and Jeffreys (1950) suggest that adding the inherent vowel character to a syllable is one of the approaches to distinguish homonyms.

u. It is not clear, however, to what extent this rule has a universal nature. In particular, numerous examples by Dugast and Jeffreys (1950) suggest that adding the inherent vowel character to a syllable is one of the approaches to distinguish homonyms.

There are also numerous irregular character combinations in the traditional A ka u ku mfɛmfɛ orthography:  mfə = fu+ɔ,

mfə = fu+ɔ,  mfɔn = fu+ɔ+m,

mfɔn = fu+ɔ+m,  lɛt = lee+a+rɯ, etc. (Schmitt 1963: 168–169).

lɛt = lee+a+rɯ, etc. (Schmitt 1963: 168–169).

We have discovered several of Gbetnkom’s innovations in the representations of syllables. Some systematic approaches include:

combinations with

ə for Cə syllables:

ə for Cə syllables:  bə = mbaa+ə,

bə = mbaa+ə,  də = ndaa+ə,

də = ndaa+ə,  kə = kɔ+ə,

kə = kɔ+ə,  mə = mɔ+ə,

mə = mɔ+ə,  lə = li+ə,

lə = li+ə,  və = vü+ə,

və = vü+ə,  sə = sɯ+ə;

sə = sɯ+ə;combinations with

üʔ for Cü syllables:

üʔ for Cü syllables:  bü = pü+üʔ,

bü = pü+üʔ,  tü = tə+üʔ,

tü = tə+üʔ,  dü = ntuu+üʔ,

dü = ntuu+üʔ,  nü = na+üʔ,

nü = na+üʔ,  lü = lɔʔ +üʔ,

lü = lɔʔ +üʔ,  sü = sɯ+üʔ,

sü = sɯ+üʔ,  yü = yɯ+üʔ;

yü = yɯ+üʔ;some new combinations for Ci and Ce syllables:

bi = pi+i,

bi = pi+i,  yi = ya+i,

yi = ya+i,  ne = na+e,

ne = na+e,  ve = fe+e,

ve = fe+e,  ye = ya+e (note that bi and ve follow the voiceless–voiced representation rule mentioned above);

ye = ya+e (note that bi and ve follow the voiceless–voiced representation rule mentioned above);some new combinations with tukwentis to represent syllable-final consonants:

-d (?). The latter two seem mostly applicable for the transcription of foreign words.

-d (?). The latter two seem mostly applicable for the transcription of foreign words.

In Table 5, the characters and their combinations are listed. It is compiled mostly from Schmitt (1963) and Dugast and Jeffreys (1950) with some data by Delafosse (1922). Information from Nchare (c. 2005) and Matateyou (2015: 139–143) supplements representation of syllables with initial voiced consonants. Gbetnkom’s additions are highlighted in red and placed on the right side of the respective cells. We are aware that some of them might have been used before in other sources that may have slipped from our attention.

The first row in cells corresponds to syllables without the glottal stop in the coda; those with the glottal stop are given in the second row. Variants of representation are separated by the slash (/). Parentheses denote two possible representations, e.g., ( )

) for wi means that this syllable can be written both

for wi means that this syllable can be written both  and

and  and (

and ( )

) for wu mean the

for wu mean the  and

and  representations. Brackets […] mark characters usage not in their primary function.

representations. Brackets […] mark characters usage not in their primary function.

Certain hints about the values of character combinations used by Gbetnkom can be obtained from a poem in French being transcribed using the A ka u ku mfɛmfɛ writing system, see examples (1)–(3). In the first line, the original French phrase is given followed by the A ka u ku mfɛmfɛ version (transcription) in the second line. The third line lists the values of individual characters (separated by hyphens within words). The fourth line contains provisional reading of the Bamum script text. Note in particular the use of  nte to represent /te/.

nte to represent /te/.

| Si l’amour était devenu la force dominante du monde actuel, |

|

| si-i la-mu-rɯ e-nte ndaa-ə-vü-ə-na-üʔ la fu-ɔ-rɯ-si ndaa-ɔ-mi-na-a-n-tə ntuu-üʔ mɔn-ndaa-ə a-kɯ-tə-üʔ-e-li |

| sii lamurɯ e(n)te dəvənü la fɔrɯsi dominaantə dü mɔndə akɯtüeli |

| Les pauvres et les faibles trouveraient forces et places dans le coeur des riches |

|

| lee pɯ-ɔ-vü-rə e lee fe-mbaa-l-ə tə-ru-fe-e-re fu-ɔ-rɯ-sɯ-ə e pɯ-la-sɯ-ɔ ndaa-a-n lɔ-ə kɔ-ə-ə-rɯ ndaa-e rii-ʃ |

| lee pɔvürə e lee feblə təruvere fɔrɯsə e pɯlasɔ dan lə kəərɯ de riiʃ |

An interesting approach is used to reflect the liaison rule:

| Dans l’âme des a ttristés |

|

| ndaa-a-n la-m ndaa-e z-a a-tə-rii-si-nte |

| dan lam de za a təriisi(n)te |

The A ka u ku mfɛmfɛ writing system has a peculiar symbol  called nʒəmli. It is used as a determinative and its role on the previous stages of the Bamum script development was to mark proper names (Schmitt 1963: 200). It is likely though that this symbol also had an additional role of distinguishing homonyms. Dugast and Jeffreys (1950: 7) suggest that nʒəmli is placed before words situated “higher” on some native scale of values. Schmitt (1963: 202–203) gives a slightly different interpretation and provides several examples where nʒəmli is used to distinguish homonyms without reference to hierarchies:

called nʒəmli. It is used as a determinative and its role on the previous stages of the Bamum script development was to mark proper names (Schmitt 1963: 200). It is likely though that this symbol also had an additional role of distinguishing homonyms. Dugast and Jeffreys (1950: 7) suggest that nʒəmli is placed before words situated “higher” on some native scale of values. Schmitt (1963: 202–203) gives a slightly different interpretation and provides several examples where nʒəmli is used to distinguish homonyms without reference to hierarchies:  i reads as yi ‘know’ while

i reads as yi ‘know’ while  means yi ‘nose’,

means yi ‘nose’,  stands for nyi ‘enter’ versus

stands for nyi ‘enter’ versus  nyi ‘knife’, etc.

nyi ‘knife’, etc.

In the book we analyze (Gbetnkom 2022), the first occurrence of nʒəmli is on the cover in the author’s name rendered as  Gbetnkom Samuel Calvin = det+Mbaa+kpa+e+ti+kɔ+ɔ+m sa+mi+üʔ+e+li ka+li+fe+e+n. Note that the determinative is placed only before the first word. The most frequent word with nʒəmli is

Gbetnkom Samuel Calvin = det+Mbaa+kpa+e+ti+kɔ+ɔ+m sa+mi+üʔ+e+li ka+li+fe+e+n. Note that the determinative is placed only before the first word. The most frequent word with nʒəmli is  Ɲiɲi ‘God’. The following geographical names are found with nʒəmli:

Ɲiɲi ‘God’. The following geographical names are found with nʒəmli:  ‘Africa’,

‘Africa’,  ‘Kilimanjaro’,

‘Kilimanjaro’,  ‘Himalaya’,

‘Himalaya’,  ‘Everest’,

‘Everest’,  ‘Mississippi’,

‘Mississippi’,  ‘America’,

‘America’,  ‘Europe’, as well as the name

‘Europe’, as well as the name  ‘Manu Dibango’, a Cameroonian musician. It does not seem that the determinative is used in another role in the texts of Gbetnkom that we analyzed, i.e., to distinguish homonyms. Also, no names without the determinative are attested in any available texts.

‘Manu Dibango’, a Cameroonian musician. It does not seem that the determinative is used in another role in the texts of Gbetnkom that we analyzed, i.e., to distinguish homonyms. Also, no names without the determinative are attested in any available texts.

4 Frequency distribution of the Bamum characters and words

We have compiled three frequency lists based on the texts of the nine poems by Samuel Calvin Gbetnkom (2022). The tenth poem in this book is in French, so it was excluded from the analysis. In the first list, a character with the kɔʔndɔn or tukwɛntis diacritical marks is considered a single token different from the respective base character (without diacritics). For the second list, the diacritical marks were removed, and the frequencies of the basic characters were counted. Finally, the third list corresponds to words in the analyzed Bamum texts. In modern practice, an ordinary space character is used to separate words. All the lists were then sorted with respect to frequencies in the descending order yielding the so-called rank–frequency lists. The first (most frequent) item has rank 1, the next word has rank 2 and so on.

There are N = 3798 running characters (tokens) in the analyzed texts. The first list contains 114 distinct characters (types) and the second list has 72 types. The latter means that not all the A ka u ku mfɛmfɛ symbols had been used in the poems: the entire set should contain 80 (semi-)syllabic characters plus one nʒəmli symbol. Note that we did not count punctuation marks and did not consider diacritical marks as separate tokens.

In fact, the following nine characters are not attested in the analyzed material:  mee,

mee,  yɔʔ,

yɔʔ,  lu,

lu,  rɯ,

rɯ,  kɛn,

kɛn,  fɔm,

fɔm,  mbɛn,

mbɛn,  mɛn, and

mɛn, and  ɣɔm. Another two occur only with diacritical marks:

ɣɔm. Another two occur only with diacritical marks:  z and

z and  yuən. Results are shown in Table 6 and Figures 2, 3.

yuən. Results are shown in Table 6 and Figures 2, 3.

Absolute frequencies of the A ka u ku mfɛmfɛ symbols. “Symbol-1” and “Frequency-1” columns correspond to characters with diacritics while “Symbol-2” and “Frequency-2” columns stand for characters with diacritics stripped off.

Rank–frequency distribution for list 1 (characters with diacritics) along with fitting functions. The values of absolute frequencies (vertical axis) are calculated as f r = NP r , where N is the sample size (total number of characters) and P r corresponds to the respective model, in particular, given by Equation (4). The variable r on the horizontal axis is rank.

Rank–frequency distribution for list 2 (characters without diacritics) along with fitting functions. The values of absolute frequencies (vertical axis) are calculated as f r = NP r , where N is the sample size (total number of characters) and P r corresponds to the respective model, in particular, given by Equation (4). The variable r on the horizontal axis is rank.

Previous studies of character distribution in various writing systems have demonstrated that the respective rank–frequency dependencies follow certain mathematical models being rather uniform at least for alphabetic scripts (Grzybek 2007; Grzybek and Kelih 2005; Li and Miramontes 2011; Wilson 2013) later extended to an abugida exemplified by Devanagari (Pande and Dhami 2015) and a syllabary exemplified by Vai (Rovenchak et al. 2018). This means in particular that mathematical patterns governing the relationship between character frequencies and their ranks in various writing systems do not significantly depend on the genre or authorship of texts. This pattern, observed to be particularly uniform in some scripts, indicates a structured and predictable distribution of characters within texts in the respective languages. Similar models can also describe distributions of syllables at least in some languages (Rovenchak and Vydrin 2020). The universal nature of such models is yet to be checked for additional abugidas and syllabaries.

Here, we focus on discrete models paying special attention to a possibility of parameter interpretation. In this respect, the so-called (1-displaced) negative hypergeometric distribution given by

is of special interest. In the above formula, (…) are the so-called binomial coefficients (Binomial coefficient 2020; Weisstein 2024), r is the rank of the symbol in the rank–frequency list, real numbers K and M are fitting parameters with no special interpretation so far; they might depend, for instance, on author or genre of a particular text. The parameter n is interpreted as the grapheme inventory size (with a unity subtracted since the minimum values for both inventory and rank are 1). Equation (4) has proven to describe well the distribution of graphemes in alphabets for Slavonic (Grzybek and Kelih 2005), German (Grzybek 2007), Irish and Manx (Wilson 2013) languages, as well as for characters in the Vai syllabary (Rovenchak et al. 2018).

We have applied the Altmann-Fitter software (Altmann 2000) to analyze the first (characters with diacritics) and second (characters without diacritics) rank–frequency lists. This tool analyses the data over a few hundreds of discrete distributions and enables finding the best fits with respect to several criteria. Without delving into mathematical details of other distributions (Wimmer and Altmann 1999), we present in Table 7 a summary of those with the best accuracy. Due to cumbersome expressions, we do not present the other two distributions explicitly. The quality of fits is demonstrated using the so-called determination coefficient R2 (the closer is its value to 1 the better fit) and the discrepancy coefficient C = χ2/N that is calculated using the Pearson χ2 goodness-of-fit test (Mačutek and Wimmer 2013). A fit is considered satisfactory if C < 0.02, which is an empirical “rule of thumb” (Antić et al. 2006; Mačutek 2008). The results are also illustrated by Figures 2 and 3.

Distributions describing the Bamum character frequencies with the best accuracy.

| Discrete distribution | C | R 2 |

|---|---|---|

| List 1: | ||

|

|

||

| Jain–Poisson (highest R2) | 0.015 | 0.991 |

| Negative hypergeometric (n = 124) | 0.039 | 0.954 |

| Negative hypergeometric (fixed n = 175) | 0.022 | 0.969 |

|

|

||

| List 2: | ||

|

|

||

| Feller–Arley (highest R2) | 0.034 | 0.974 |

| Negative hypergeometric (n = 74) | 0.034 | 0.945 |

| Negative hypergeometric (fixed n = 80) | 0.031 | 0.947 |

The first immediate observation from Table 7 is that the negative hypergeometric distribution [Equation (4)] does not produce a good fit: for both lists, C > 0.02 and is almost twice as high as the desired maximum value for a proper fit. Another interesting result is that the value of the n parameter in this distribution does not reflect the inventory size of the script. For the first list, n = 124 is rather far from the expected 175 corresponding to 80 characters with and without kɔʔndɔn, 15 characters with tukwɛntis (this includes original 13 plus two being Gbetnkom’s innovations), and nʒəmli. For the second list, the inventory size corresponds to n = 80 while the fitting yields n = 74. Note that the quality of fitting improves if the value of n is fixed appropriately; still, the discrepancy coefficient C remains too high in these cases. The behavior of graphs in Figures 2 and 3 might be misleading as all the curves seem to follow the observed data in a satisfactory manner. This impression is due to the logarithmic vertical scale, which compresses the actual values closer together. To get an idea about the quality of the fitting, one should consult the C and R2 values.

The two-fold nature of the A ka u ku mfɛmfɛ script, i.e., the presence of both syllabic and alphabetic features, might be to blame for the character distribution not following the expected negative hypergeometric law with good precision. Distribution yielding better fitting characteristics require additional studies as the interpretations of their parameters is not well-established. Note that the Jain–Poisson distribution was shown to be a proper model for syllable distribution in Bamana and Maninka (Rovenchak and Vydrin 2020). The failure of the negative hypergeometric distribution to achieve a desired accuracy could mean, in particular, that in the A ka u ku mfɛmfɛ writing system proper units to analyze in this regard are not characters but certain of their combinations.

In Table 8, the most frequent words in the analyzed poems are listed. Since the A ka u ku mfɛmfɛ script lacks tone marking, it is not possible to tell apart homographs differing in tone only. Obviously, complete homonyms (words with the same tone) cannot be differentiated as well without deeper analysis of the respective word occurrences in sentences. A glossed text is required in order to deal with such situations. At the moment, no tools to analyze this level of the Bamum languages are available.

Most frequent words in the poems by Samuel Gbetnkom.

-

The following standard glosses are used for personal pronouns: 1SG – 1st person singular, 1PL – 1 person plural, 2SG – 2nd person singular; 3SG – 3rd person singular; 3PL – 3rd person plural.

*Schmitt (1963: 682, 689, 696) gives naa ‘mother’. **Schmitt (1963: 691) suggests a possible reading yii ‘this’.

In the third frequency list, there are 587 distinct words (types) while the total number of running words in the analyzed poems is 1622. More than two thirds of the types (396) occur only once in the texts. Such types are known as hapax legomena and their share can indeed be that high for rather short texts (cf. Kornai 2002). Note that the first ten most frequent words occupy more than 25 per cent of the text (407 of 1622 running words), while the first 15 words correspond to more that 30 per cent of text (494 of 1622). Slightly more than 50 words are required to cover a half of text and almost 190 suffice for 75 per cent.

The structure of the high-frequency vocabulary is quite regular. As we can see from Table 8, the majority of words there are function words (conjunctions, prepositions). Every third word of 15 is a personal pronoun and body parts are the only nouns within the top-frequent words. The appearance of body parts in high-frequency vocabulary was observed across various languages and text genres (see, e. g., Buk and Rovenchak 2007; Pattillo 2021).

There are a couple of interesting remarks here. First, the  modification to represent -ə syllables that might seem secondary from Table 5 is in fact one of the most productive in the running text: it appears in four out of 15 most frequent words. Another observation is that nda ‘true, good’ and mbə ‘to be’ from the top-frequent words have an “alphabetic” (three-symbol) representation. With a variety of approaches to form syllables in the Bamum script, it remains unclear why such a complicated approach was used in those cases, e.g., why not *

modification to represent -ə syllables that might seem secondary from Table 5 is in fact one of the most productive in the running text: it appears in four out of 15 most frequent words. Another observation is that nda ‘true, good’ and mbə ‘to be’ from the top-frequent words have an “alphabetic” (three-symbol) representation. With a variety of approaches to form syllables in the Bamum script, it remains unclear why such a complicated approach was used in those cases, e.g., why not * or *

or * to render mbə.

to render mbə.

5 Conclusions

In the first part of the paper, we have summarized the information about the phonology of Bamum and demonstrated certain discrepancies across various authors, especially with respect to the vowel inventory. We have been able to confirm previous suggestions by Nchare (2012) regarding historical changes of vowels, with the additional [e]→[i] shift discovered.

We have analyzed orthographic principles of the last version of the Bamum script known as A ka u ku mfɛmfɛ. An attempt was made to summarize variants of syllable representation based on various sources. The study of texts by Samuel Calvin Gbetnkom, a modern Bamum author, suggests certain regularization of syllable representation in modern practice. We might be witnessing a gradual establishment of a new orthographic norm in A ka u ku mfɛmfɛ. To corroborate these observations, further studies are required with more texts in the script by various authors, especially modern ones. It should be noted in particular that existing variability in syllable representations provides potential possibilities to distinguish homonyms and even to mark tones on a regular basis.

The analysis performed on the rank–frequency distributions of characters in the A ka u ku mfɛmfɛ script failed to achieve the desired accuracy with a mathematical model known as the negative geometric distribution, where one of the fitting parameters corresponds to the character inventory size. This result suggests that in complex orthographies, proper units aligning with this model are not characters but some of their combinations, even though, e.g., letter frequencies in English follow the mentioned distribution (Pande 2021). A recently proposed model (Özbey 2023) is worth attention in the future, as it was applied to describe character frequencies in over 100 languages, including those using non-alphabetic scripts like Amharic, Devanagari, Ojibwe, as well as Chinese and Japanese. Last but not least, ancient writing systems with both alphabetic and syllabic features, namely, Old Persian cuneiform (cf. Kent 1989) or Paleohispanic scripts (cf. Ferrer and Moncunill 2019), should be studied to discover a proper mathematical model for character frequency distribution, although the available material for quantitative analysis is rather limited.

While the fraction of alphabetic characters in Bamum is much lower than in the Old Persian script, there is at least one common feature in both writing systems: pleonastic representation of some syllables. Repeating the inherent vowel is typical of Old Persian, for instance,  di+i stands for di (see Testen 1996). In Bamum, however, this approach mostly serves a different purpose—voicing the onset—and most probably historically it was also used to discriminate homonyms, as we have mentioned in Section 3 (cf. also Coulmas 2004, p. 38).

di+i stands for di (see Testen 1996). In Bamum, however, this approach mostly serves a different purpose—voicing the onset—and most probably historically it was also used to discriminate homonyms, as we have mentioned in Section 3 (cf. also Coulmas 2004, p. 38).

We have performed an analysis of the Bamum character frequency data using distributions considered by Özbey (2023) and have not obtained a good fit for both rank–frequency lists (with and without diacritics). In particular, the parameter responsible for the character inventory size appeared significantly different from the real values (about 50 % and over 200 %, depending on the model). It is worth mentioning that a quick analysis of the Old Persian based on partial frequency data from the Behistun inscription (Hallock 1970) proved the negative hypergeometric distribution as the best fit, with the proper value of the parameter corresponding to the inventory size of 36 symbols (Testen 1996).

Finally, we would like to stress that for any widescale analysis of Bamum, electronic form of texts is essential. Some texts (by Abdoulaye Mbouombouo, another modern Cameroonian poet) available in Shümom, a secret language invented by Njoya, are another source for studies of the script. Moreover, it would be informative to conduct some analysis for Shümom itself. Corpus-based studies of the Bamum language are yet to be done and tools for processing this language yet await their creation and implementation.

Bibliography concerning the Bamum script

The following list is mostly based on two bibliographies (Barreteau et al. 1993; Ehlich et al. 1996) and is supplemented by some newer items we were able to discover as well as by references from older works. Modern works being mostly compilatory in nature as well as encyclopedia-like editions are not included. The list is sorted by date of publication.

Characters of the modern Bamum script with their phonetic values based on different sources.

Göhring, Martin. 1907a.

Göhring, Martin. 1907b.

Göhring, Martin. 1907c.

Göhring, Martin. 1907d.

Göhring, Martin. 1908.

Van Gennep, Arnold. 1908.

Struck, Bernhard. 1908.

Van Gennep, Arnold. 1909.

Meinhof, Carl. 1911.

Oehler, Anna. 1913.

Delafosse, Maurice. 1922.

Debarge, Josette. 1928–1929.

Labouret, Henri. 1935.

Crawford, O. G. S. 1935.

Dugast, Idelette. 1950.

Martin, Henri. 1951.

Dugast, Idelette and Jeffreys, M. David W. 1950.

Jeffreys, Mervyn David W. 1952.

Friedrich, Johannes. 1954.

Schmitt, Alfred. 1963.

Welch, Claude E. 1964.

Schmitt, Alfred. 1966.

Schmitt, Alfred. 1967.

Njoya, Ibrahim, Emmanuel Ghomsi, Aboubakar Njiasse Njoya & Martin Njimotapon Njikam. 1987.

Tardits, Claude. 1991.

Nchare, Oumarou. [c. 2005].

Nchare, Oumarou. [s.d.]

Riley, Charles. 2006.

Riley, Charles. 2006/2007.

Everson, Michael & Charles Riley. 2007.

Everson, Michael, Charles Riley & Konrad Tuchscherer. 2008.

Matateyou, Emmanuel (éd.). 2015.

Orosz, Kenneth J. 2015.

References

Altmann, Gabriel. 2000. Altmann-Fitter 2.1. Lüdenscheid: RAM-Verlag.Search in Google Scholar

Antić, Gordana, Ernst Stadlober, Peter Grzybek & Emmerich Kelih. 2006. Word length and frequency distributions in different text genres. In Myra Spiliopoulou, Rudolf Kruse, Christian Borgelt, Andreas Nürnberger & Wolfgang Gau (eds.), From data and information analysis to knowledge engineering (Studies in Classification, Data Analysis, and Knowledge Organization), 310–317. Berlin & Heidelberg: Springer.10.1007/3-540-31314-1_37Search in Google Scholar

Barreteau, Daniel, Terry Scruggs & Évelyne Ngantchui. 1993. Bibliographie des langues camerounaises. Paris: Orstom.Search in Google Scholar

Battestini, Simon. 2004. African writing systems, texts and cultural identities. TRANS Internet-Zeitschrift für Kulturwissenschaften 15. http://www.inst.at/trans/15Nr/01_2/battestini15.htm (accessed 18 August 2022).Search in Google Scholar

Bernard, H. Russell, George N. Mbeh, and W. Penn Handwerker. 2002. Does marking tone make tone languages easier to read? Human Organization 61(4). 339–349. http://www.jstor.org/stable/44127574.10.17730/humo.61.4.3u6lumuux1fn3q3ySearch in Google Scholar

Binomial coefficients. 2020. In Encyclopedia of mathematics URL: http://encyclopediaofmath.org/index.php?title=Binomial_coefficients&oldid=46066.Search in Google Scholar

Bird, Steven. 1999. When marking tone reduces fluency: An orthography experiment in Cameroon. Language and Speech 42(1). 83–115. https://doi.org/10.1177/00238309990420010401.Search in Google Scholar

Bird, Steven. 2001. Orthography and identity in Cameroon. Written Language & Literacy 4(2). 131–162. https://doi.org/10.1075/wll.4.2.02bir.Search in Google Scholar

Buk, Solomija & Andrij Rovenchak. 2007. Statistical parameters of Ivan Franko’s novel Perekhresni stežky (The Cross-Paths). In Peter Grzybek & Reinhard Köhler (eds.), Exact methods in the study of language and text: Dedicated to professor Gabriel Altmann on the occasion of his 75th birthday (Quantitative Linguistics, Vol. 62), 39–48. Berlin & New York: Mouton de Gruyter.10.1515/9783110894219.39Search in Google Scholar

Census data. 2005. Census data. Cameroon data portal. https://cameroon.opendataforafrica.org/rfdefze/census-data (accessed 07 August 2022).Search in Google Scholar

Coulmas, Florian. 2004. The Blackwell encyclopedia of writing systems. Blackwell, Malden, MA: Blackwell.Search in Google Scholar

Crawford, O. G. S. 1935. The writing of Njoya. Antiquity 9(36). 435–442. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0003598X00010917.Search in Google Scholar

Daniels, Peter T. 2023. Non-roman scripts of Africa. In R. M. Joshi, C. A. McBride, B. Kaani & G. Elbeheri (eds.), Handbook of Literacy in Africa. Literacy studies, vol. 24, 45–58. Cham: Springer.10.1007/978-3-031-26250-0_3Search in Google Scholar

Debarge, Josette. 1928–1929. Note sur l’écriture inventée par Njoya, Sultan des Bamoun. Archives Suisses d’Anthropologie Generale 5. 243–247.Search in Google Scholar

Delafosse, Maurice. 1922. Naissance et évolution d’un système d’écriture de création contemporaine. Revue d’Ethnographie et des Traditions Populaires 3(9). 11–36.Search in Google Scholar

Dugast, Idelette. 1950. La langue secrète du Sultan Njoya. Études Camerounaises 31–32(3). 231–260.Search in Google Scholar

Dugast, Idelette & M. David W. Jeffreys. 1950. L’écriture des Bamum : sa naissance, son évolution, sa valeur phonétique, son utilisation. Paris: Le Charles Louis.Search in Google Scholar

Ehlich, Konrad, Florian Coulmas & Gabriele Graefe (eds.). 1996. A bibliography on writing and written language (Trends in linguistics: Studies and monographs 89), vol. 3. Berlin & New York: Mouton de Gruyter.Search in Google Scholar

Ethnologue. 2024. Bamun. In David M. Eberhard, Gary F. Simons & Charles D. Fennig (eds.), Ethnologue: Languages of the World, 27th edn. Dallas, Texas: SIL International Online version: https://www.ethnologue.com/language/bax.Search in Google Scholar

Everson, Michael & Charles Riley. 2007. Preliminary proposal for encoding the Bamum script in the BMP of the UCS. ISO/IEC JTC1/SC2/WG2 N3209R ; L2/07-024R. https://www.unicode.org/L2/L2007/07024r-n3209r-bamum.pdf.Search in Google Scholar

Everson, Michael, Charles Riley & Tuchscherer Konrad. 2008. Proposal to encode modern Bamum in the BMP of the UCS. JTC1/SC2/WG2 N3522; L2/08-350. https://www.unicode.org/L2/L2008/08350-n3522-bamum.pdf.Search in Google Scholar

Ferrer, J. & N. Moncunill. 2019. Palaeohispanic writing systems: Classification, origin, and development. In Alejandro G. Sinner & Javier Velaza (eds.), Palaeohispanic Languages and Epigraphies, 78–108. Oxford: Oxford University Press.10.1093/oso/9780198790822.003.0004Search in Google Scholar

Friedrich, Johannes. 1954. Alaska-Schrift und Bamum-Schrift. Zeitschrift der Deutschen Morgenländischen Gesellschaft 104[n. F. 29](2). 317–329. http://www.jstor.org/stable/43368986.Search in Google Scholar

Galitzine-Loumpet, Alexandra. 2011. La cartographie du roi Njoya (Royaume Bamoun, Ouest Cameroun) : Représenter / traduire son espace-monde. Cartes et géomatique 210. 185–198. https://www.lecfc.fr/new/articles/210-article-14.pdf (accessed 16 August 2022).Search in Google Scholar

Gbetnkom, Samuel Calvin. 2022. Lo’ tù lu lulùre pon ntièn = Des ombres résilientes = From the resilient shadows. New Haven: Athinkra.Search in Google Scholar

Gnanadesikan, Amalia E. 2011. Syllables and syllabaries: What writing systems tell us about syllable structure. In Charles E. Cairns & Eric Raimy (eds.), Handbook of the syllable, 395–414. Leiden: Brill.10.1163/ej.9789004187405.i-464.118Search in Google Scholar

Göhring, Martin. 1907a. Der König von Bamun und seine Schrift. Der Evangelische Heidenbote 80(6). 41–42.Search in Google Scholar

Göhring, Martin. 1907b. Die Bamun-Schrift. Der Evangelische Heidenbote 80(11). 83–86.Search in Google Scholar

Göhring, Martin. 1907c. Der König von Bamum und seine Silbenschrift. Mitteilungen der Geographischen Gesellschaft für Thüringen zu Jena 25. 68–69.Search in Google Scholar

Göhring, Martin. 1907d. Sämtliche Zeichen der vom König Njoya von Bamum erfundenen Schrift. Mitgeteilt durch den Baseler Missionar Göhring. Basel: Missionsbuchhandlung. 1 Bl. F°.Search in Google Scholar

Göhring, Martin. 1908. Die Sach’ is dein, Herr Jesu Christ. Der Evangelische Heidenbote 81(2). 9–10.Search in Google Scholar

Grzybek, Peter. 2007. On the systematic and system-based study of grapheme frequencies: A reanalysis of German letter frequencies. Glottometrics 15. 82–91.Search in Google Scholar

Grzybek, Peter & Emmerich Kelih. 2005. Towards a general model of grapheme frequencies in Slavic languages. In Radovan Garabík (ed.), Computer treatment of Slavic and East European languages, 73–87. Bratislava: Veda.Search in Google Scholar

Hallock, Richard T. 1970. On the Old Persian signs. Journal of Near Eastern Studies 29(1). 52–55. https://doi.org/10.1086/372043.Search in Google Scholar

Jeffreys, Mervyn David W. 1952. The alphabet of Njoya, king of a tribe in the French Cameroons. West Africa Review 23(296). 428–430, 433.Search in Google Scholar

Kent, Roland G. 1989. Old Persian : Grammar, texts, lexicon. 2nd edn., rev. New Haven: American Oriental Society.Search in Google Scholar

Koelle, Sigismund Wilhelm. 1854. Polyglotta Africana, or a comparative vocabulary of nearly three hundred words and phrases, in more than one hundred distinct African languages. London: Church Missionary House.Search in Google Scholar

Kornai, András. 2002. How many words are there? Glottometrics 4. 61–86.Search in Google Scholar

Labouret, Henri. 1935. L’écriture bamoun. Togo-Cameroun 1935(avril–juillet). 127–133.Search in Google Scholar

Li, Wentian & Pedro Miramontes. 2011. Fitting ranked English and Spanish letter frequency distribution in US and Mexican Presidential speeches. Journal of Quantitative Linguistics 18(4). 359–380. https://doi.org/10.1080/09296174.2011.608606.Search in Google Scholar

Lüpke, Friederike. 2011. Orthography development. In P. K. Austin & J. Sallabank (eds.), The Cambridge handbook of endangered languages. (Cambridge handbooks in language and linguistics), 312–336. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.10.1017/CBO9780511975981.016Search in Google Scholar

Mačutek, Ján. 2008. A generalization of the geometric distribution and its application in quantitative linguistics. Romanian Reports in Physics 60(3). 501–509.Search in Google Scholar

Mačutek, Ján & Gejza Wimmer. 2013. Evaluating goodness-of-fit of discrete distribution models in quantitative linguistics. Journal of Quantitative Linguistics 20(3). 227–240. https://doi.org/10.1080/09296174.2013.799912.Search in Google Scholar

Markowska, Magdalena. 2020. Tones in Shupamem Reduplication. New York, NY: City University of New York M.A. thesis.Search in Google Scholar

Martin, Henri. 1951. Le pays des Bamum et le Sultan Njoya. Études camerounaises (Yaounde) 33–34. 5–40.Search in Google Scholar

Matateyou, Emmanuel. 2002. Parlons bamoun. Paris, Budapest & Torino: L’Harmattan.Search in Google Scholar

Matateyou, Emmanuel (éd.), 2015. L’écriture du roi Njoya : une contribution de l’Afrique à la culture de la modernité, 391. Paris: L’Harmattan.Search in Google Scholar

Mazrui, Alamin M. & Ali A. Mazrui. 1992. Language in a multicultural context: The African experience. Language and Education 6(2–4). 83–98. https://doi.org/10.1080/09500789209541330.Search in Google Scholar

Meinhof, Carl. 1911. Zur Entstehung der Schrift. Zeitschrift für Ägyptische Sprache und Altertumskunde 49(1–2). 1–24. https://doi.org/10.1524/zaes.1911.49.12.1.Search in Google Scholar

Nchare, Oumarou. c. 2005. The writting [sic] of king Njoya: Genesis, evolution, use. Foumban: Palais des Rois Bamoun, Maison de la Culture.Search in Google Scholar

Nchare, Abdoulaye Laziz. 2012. The Grammar of Shupamem. New York, NY: New York University PhD dissertation.Search in Google Scholar

Nchare, Oumarou. s.d. Je voudrais apprendre l’écriture Shümom. [S.l.]Search in Google Scholar

Nganang, Patrice. 2015. In praise of the alphabet. In Frieda Ekotto & Kenneth W. Harrow (eds.), Rethinking African cultural production, 78–93. Bloomington & Indianapolis: Indiana University Press.10.2307/j.ctt16gz7gh.8Search in Google Scholar

Njoya, Ibrahim, Emmanuel Ghomsi, Aboubakar Njiasse Njoya & Martin Njimotapon Njikam. 1987. Ŋga nsapŋgam : Recueil de proverbes bamum (Travaux et documents de l’Institut des sciences humaines, no 37), 95. Yaoundé: Ministère de l’enseignement supérieur et de la recherche scientifique, Centre de recherche et d’études anthropologiques [A collection of 76 proverbs presented first in French, then in Bamum orthography, and finally in the orginial Shʉpaməm script.].Search in Google Scholar

Oehler, Anna. 1913. Der Negerkönig Ndschoya, 2nd edn. 16. Basel: Basler Missionsbuchhandlung 1915.Search in Google Scholar

Orosz, Kenneth J. 2015. Njoya’s alphabet. The Sultan of Bamum and French colonial reactions to the A ka u ku script. Cahiers d’Études Africaines 217. 45–66. https://doi.org/10.4000/etudesafricaines.18002.Search in Google Scholar

Özbey, Can. 2023. Oblique logistic function for the rank-frequency distribution of letters. In 2023 4th International Informatics and Software engineering Conference (IISEC). Ankara, Turkiye.10.1109/IISEC59749.2023.10390992Search in Google Scholar

Pande, Hemlata. 2021. Mathematical modeling of the frequencies of letters for their occurrence in corpora, words (types) and in the initial positions of words of corpora. Glottotheory 12(1). 57–69. https://doi.org/10.1515/glot-2020-2010.Search in Google Scholar

Pande, Hemlata & Hoshiyar S. Dhami. 2015. Analysis and mathematical modelling of the pattern of occurrence of various Devanāgari letter symbols according to the phonological inventory of Indic script in Hindi language. Journal of Quantitative Linguistics 22(1). 22–43. https://doi.org/10.1080/09296174.2014.974457.Search in Google Scholar

Pattillo, Kelsie. 2021. On the borrowability of body parts. Journal of Language Contact 14(2). 369–402. https://doi.org/10.1163/19552629-14020005.Search in Google Scholar

Pawou Molu, Solange. 2018. Problèmes de morphophonologie nominale en langue bamun (ʃʉ̂pǎmə̀m). Paris: Université Sorbonne Paris Cité dissertation.Search in Google Scholar

Riley, Charles. 2006a. Report on work with the Bamum script in Cameroon. L2/06-313. https://www.unicode.org/L2/L2006/06313-riley-cameroon.pdf.Search in Google Scholar

Riley, Charles. 2006b/2007. Towards the encoding of the Bamum script in the UCS. L2/07-023. https://www.unicode.org/L2/L2007/07023-bamum-report.pdf.Search in Google Scholar

Rovenchak, Andrij & Solomija Buk. 2020. Indigenous African scripts. In Rainer Vossen, J. Gerrit & Dimmendaal (eds.), The Oxford Handbook of African languages, 797–812. Oxford: Oxford University Press.10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199609895.013.80Search in Google Scholar

Rovenchak, Andrij & Valentin Vydrin. 2020. Syllable frequencies in Manding: Examples from periodicals in Bamana and Maninka. Glottometrics 48. 17–37.Search in Google Scholar

Rovenchak, Andrij, Charles Riley & Tombekai Sherman. 2018. The diary of Boima Kiakpomgbo from Mando Town (Liberia): A quantitative study of a Vai text. Journal of Quantitative Linguistics 25(3). 271–287. https://doi.org/10.1080/09296174.2017.1373510.Search in Google Scholar

Schmitt, Alfred. 1963. Die Bamum-Schrift. 3 Bde (1. Text 2. Tabellen 3. Urkunden), vol. XVI, 700 + 59 + 73. Wiesbaden: Otto Harrossowitz, maps.Search in Google Scholar

Schmitt, Alfred. 1966. Ein Plan der Stadt Fumban, gezeichnet und beschriftet von einem Bamum-Mann. Anthropos 61(3/6). 529–543. http://www.jstor.org/stable/40458370.Search in Google Scholar

Schmitt, Alfred. 1967. Die Bamum-Schrift. Studium Generale 20. 594–604.Search in Google Scholar

Schumann, Clara. 2019. In search of « camerounité »: On the reappropriation of emigrant authors in the Cameroonian press. Études littéraires africaines 48. 115–129. https://doi.org/10.7202/1068435ar.Search in Google Scholar

Struck, Bernhard. 1908. König Ndschoya von Bamum als Topograph. Globus: Illustrierte Zeitschrift für Länder- und Völkerkunde (Braunschweig) 94(13). 206–209.Search in Google Scholar

Tadadjeu, Maurice & Etienne Sadembouo. 1979. Alphabet générale des langues camerounaises. Yaoundé: Departement des Langues Africaines et Linguistique, Université de Yaoundé, Cameroun.Search in Google Scholar

Tardits, Claude. 1991. L’écriture, la politique et le secret chez les bamoum. Africa: Rivista Trimestrale di Studi e Documentazione dell’Istituto Italiano per l’Africa e l’Oriente 46(2). 224–240. https://www.jstor.org/stable/40761904.Search in Google Scholar

Testen, David. D. 1996. Old Persian Cuneiform. In Peter T. Daniels & William Bright (eds.), The World’s writing systems, 134–137. New York: Oxford University Press.Search in Google Scholar

Tuchscherer, Konrad. 2007. Recording, communicating and making visible: A history of writing and systems of graphic symbolism in Africa. In Christine Mullen Kreamer, Mary Nooter Roberts, Elizabeth Harney & Allyson Purpura (eds.), Inscribing meaning: Writing and graphic systems in African art, 37–53. Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution.Search in Google Scholar

Unseth, Peter. 2011. Invention of scripts in West Africa for ethnic revitalization. In Joshua A. Fishman & Ofelia García (eds.), The handbook of language and ethnic identity. Vol. 2: The success-Failure continuum in language and ethnic identity efforts, 23–32. New York: Oxford University Press.Search in Google Scholar

Van Gennep, Arnold. 1908. Une nouvelle écriture nègre: Sa portée théorique. Revue des études ethnographiques et sociologiques 1(3). 129–139.Search in Google Scholar

Van Gennep, Arnold. 1909. Une nouvelle écriture nègre: sa portée théorique. In Religions, mœurs et légendes: essais d’ethnographie et de linguistique (Deuxième Série), 2e éd, 259–277. Paris: Mercvre de France.Search in Google Scholar

Ward, Ida C. 1938. The phonetic structure of Bamum. Bulletin of the School of Oriental Studies, University of London 9(2). 423–438. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0041977x00076989. https://www.jstor.org/stable/608347.Search in Google Scholar

Weisstein, Eric W. 2024. Binomial Coefficient. In MathWorld – A Wolfram web resource. https://mathworld.wolfram.com/BinomialCoefficient.html.Search in Google Scholar

Welch, Claude E. 1964. Njoya and the Bamoun script. West Africa 2453. (January–June). 621.Search in Google Scholar

Wilson, Andrew. 2013. Probability distributions of grapheme frequencies in Irish and Manx. Journal of Quantitative Linguistics 20(3). 169–177. https://doi.org/10.1080/09296174.2013.799919.Search in Google Scholar

Wimmer, Gejza & Gabriel Altmann. 1999. Thesaurus of univariate discrete probability distributions. Essen: Stamm.Search in Google Scholar

Zang Zang, Paul. 2012. Cohabitation des langues dans les medias au Cameroun 1884–1960. Revue électronique internationale de sciences du langage Sudlangues 18. 18–34. http://www.sudlangues.sn/spip.php?article197.Search in Google Scholar

© 2025 the author(s), published by De Gruyter, Berlin/Boston

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Articles

- The evolution of the Mawes Aas’e (Omotic-Mao) pronouns: evidence for Omotic Lineage

- The canar-yi in the coal mine: The loss of yi in Zulu reduplication

- Ideophones in Gizey grammar

- An overview of Bamum phonology and orthography, with an additional focus on character and word frequencies in recent poetry

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Articles

- The evolution of the Mawes Aas’e (Omotic-Mao) pronouns: evidence for Omotic Lineage

- The canar-yi in the coal mine: The loss of yi in Zulu reduplication

- Ideophones in Gizey grammar

- An overview of Bamum phonology and orthography, with an additional focus on character and word frequencies in recent poetry