Abstract

This article puts Werner Herzog’s films in dialogue with Martin Heidegger’s philosophy to answer the question of how to dwell, to be at home with nature. I argue that an apathy–empathy aporia blockades the discussion of the nature–human relationship in Herzog’s cinema, which tends to view his representation of nature as either entirely apathetic to human flourishing or totally identifiable with being human. Both versions of nature fail to do full justice to the nuanced vision of nature in Herzog, especially its dynamics and problematics as a safe place. To address this problem, I will closely read and compare three of his films across his career: Aguirre, The Wrath Of God (1972), Grizzly Man (2005), and Happy People: A Year in the Taiga (2010) in the light of Heidegger’s philosophy. Drawing on Heidegger’s thought on dwelling, technology, being-in-the-world, temporality, Gelassenheit, and Care, I move away from the standard paradigm and reinterpret the nature–human relationship in Herzog as a negotiation between the homely and the unhomely in search of an equilibrium I call “active serenity.” Thus, this article is both a film-philosophy experiment with Herzog and Heidegger and a contemplation of the antagonism between humans and nature, which underlines our modern world.

1 Introduction: Un-frameable Nature

A wide shot of wild nature initiates Heart of Glass (Herzog, 1976), one of Werner Herzog’s early masterpieces. A sea of fog sweeps over the mountains and moves swiftly from frame left to frame right, a majestic gesture of nature that defies framing (Figure 1). Such un-frameable nature permeates Herzog’s oeuvre. For instance, Ames (2016, p. 43) writes that the natural environment in Aguirre, The Wrath Of God [Herzog, 1972 (henceforth Aguirre)] is “unlimited by the frame and resistant to simulation in a studio set,” and “the immensity of space is indifferent to the camera.” Wondering at this vision of nature in Herzog, Barber (2015, p. 154) argues, “it emerges as an actor with its own agency and its own story to tell, and pushes back against human attempts at control.” Thus, this excessive, majestic, and autonomous nature complicates the nature–human relationship as simplified in classic Hollywood cinema. For example, in Douglas Sirk’s All That Heaven Allows (1955), nature is fetishised as an icon of humans’ normative yearning for simplicity, authenticity, and felicity. Encapsulated in the ending shot (Figure 2), nature is carefully framed by the windowpane and filtered through the window as banal, rosy scenery, a mere extension of the comforts of home, an index towards the prospect of a happy marriage. By contrast, as Gandy (2012, p. 536) writes, “there is a brutal immediacy about Herzog’s award-winning Grizzly Man (2005) that poses a profound challenge towards benign or sentimentalised conceptions of nature.” Hence, the nature–human relationship is far more complicated in Herzog, which is a constant attraction for critics and scholars.

Herzog’s frameless and unframeable nature of excess, majesty, and autonomy.

Sirk’s cozy and rosy nature as a well-framed happy ending.

Debates on the nature–human relation in Herzog are centred around whether nature is apathetic or empathetic toward human beings. On the one hand, nature seems indifferent. Commenting on the representation of landscape in Signs of Life (1968) and Aguirre, Horak (1979, p. 226) says nature appears as “a dangerous force, threatening by the very nature of its cosmic indifference to man.” Likewise, Prager (2007, p. 261) argues that the contrasting enormity of mountain images and the minuteness of human figures in La Soufrière (1977) and Scream of Stone (1991) accentuate “the landscape’s indifference to our presence.” Similar views hold that nature in Herzog is discordant and chaotic (Noys, 2007, p. 38), horrible (Ladino, 2009), incomprehensible (Barber, 2015), and hostile (Eldridge, 2019). “The natural world for Herzog,” as Furstenau (2020, p. 70) summarises, “is essentially chaotic, meaningless, without order or sense.” In short, on this side of the debate, nature in Herzog is perceived as an apathetic and alien force to humans, an unhomely place to dwell, an unsafe place par excellence.

On the other hand, nature seems to connect and empathise with human beings in a profound and primordial way. Investigating the landscapes in Herzog’s documentaries, Ames (2009, p. 49) argues that these images of nature are so intimately connected with humans that they exteriorise human beings’ “inner world of affect.” Prager (2007, p. 39) also notes this Herzogian use of “the landscape as an external representation of the complexities of internal psychology.” Such profound resonation between nature and humans leads Trigg (2012, p. 141) to conclude that in Herzog, as in Merleau-Ponty, “a philosophy of nature exists which challenges the dichotomy between” the self and the wilderness. Hence, according to this side of the argument, the boundary between nature and humanity collapses into overwhelming empathy and resonance between these two realms. Such paradoxical attitudes towards nature–human relations in Herzog are partly fuelled by Herzog himself, who claims to represent nature both as “chaos, hostility, and murder” (Herzog, 2005) and as “an inner state of mind, literally inner landscapes” (Cronin & Herzog, 2002, p. 136). We can speculate that it is this intrinsic apathy–empathy paradox residing in Herzog’s nature that constantly drives it to exceed both the cinematic frame and the theoretical framing.[1]

Such a paradox, I argue, makes Herzog’s cinema a promising site for exploring the problematics and dynamics of nature as a potential safe place for human flourishing, a place where we dwell, where we feel at home. For this project, Martin Heidegger’s philosophy provides an ideal framework. The relevance of Heidegger to understanding Herzog is a disputed issue. His name is dropped as a reference here and there to flesh out arguments.[2] However, before Moore’s (2020) more recent essay “The Great Ecstasy of Werner Herzog: Truth, Heidegger, Apocalypse,” Heidegger is barely engaged with as a central theoretical framework. In his The Cinema of Werner Herzog: Aesthetic Ecstasy and Truth, the first monograph on Herzog in English, Prager (2007, p. 21) suspects if such a close engagement is worthwhile at all, saying that “Heideggerian readings of Herzog, though they may properly isolate some degree of overlap in their discourses, remain only individual, possible readings.” One can even cite Herzog’s authorial intention to support this dismissal. “I can’t crack the code of Hegel and Heidegger,” as he tells Cronin (Cronin & Herzog, 2014, p. 178). Moreover, Heidegger’s Nazi controversy, sparked by the publication of the Black Notebooks and monumentalised by Wolin’s most recent Heidegger in Ruins: Between Philosophy and Ideology (2022), seems to disparage any further “Heideggerian” exploration of Herzog.

Against this background, this “unsafe place” for Heidegger, this article aims to rediscover Heidegger for Herzog, recuperating the use value of Heidegger’s philosophy for illuminating the truth content of Herzog’s vision of nature. Thus, my engagement with Heidegger is less ideological and more pragmatic. It has less to do with whether one should still think with Heidegger or not but more about how Heidegger’s thoughts can help to unravel the paradox in Herzog’s cinema to tell us more about the conditions of nature as a safe place. My central thesis is that nature, as Herzog’s films help to reveal, is not safe or unsafe per se but becomes so as the outcome of human beings’ dwelling with nature, as a becoming homely in being unhomely in nature. In other words, nature is neither an unsafe place, dangerous and hostile, in and of itself, nor a safe place where we can do whatever we want, an anthropocentric arena of objectification, exploitation, and projection. Rather, it only becomes a safe place if we realise that nature is the home to which we belong and are indebted and over which we must have stewardship and responsibility.[3] The dialectical insight of the homely and the unhomely comes from Heidegger’s Hölderlin lectures: “What is worthy of poetising in this poetic work is nothing other than becoming homely in being unhomely” (Heidegger, 1996, p. 121 emphasis added). The poet Hölderlin, as Prager (2007, p. 471) notes, has influenced Herzog’s cinematic vision more than any other filmmaker. The becoming homely in being unhomely in Herzog is a striving toward what I call “active serenity,” an equilibrium between empathy and apathy, which negotiates nature’s safety.[4]

The argument will unfold in the following way: First, I will lay out Heidegger’s thinking on nature as the theoretical foundation for discussion. Then, I will look at Aguirre as a cinematic exploration of what Heidegger diagnoses as the modern tendency to objectify nature as a mere exploitable resource in a colonial setting. Such apathetic objectification and exploitation of nature turn both humans and nature into uncanny/unhomely monsters. Comparatively, the seemingly empathic identification with nature, the total being-at-home in nature as attempted by Timothy Treadwell in Grizzly Man, also leads to natural and human disasters. In both cases, nature becomes an extremely unsafe place in contradistinctive ways. As a way out, the balance between apathy and empathy, homeliness and unhomeliness inherent in dwelling, is reached in Happy People: A Year in the Taiga (Herzog & Vasyukov, 2010) (henceforth Happy People) as “active serenity.” Hence, these films have been selected out of some 70 films made by Herzog to exemplify the visions of the extremity of being-not-at-home and being-at-home in nature and their redemptive synthesis.

The argument is not about discovering Herzog’s authorial opinions about nature, which, aside from the contradictions mentioned above, are further diluted by co-authorship and co-production inherent to the complex art form of cinema.[5] Instead, it articulates a hermeneutic circle between Herzog’s cinema and Heidegger’s philosophy to refresh our understanding of the complex human–nature relationship. This means that while I do engage with Herzog on various levels: Herzog-the-filmmaker, Herzog-the-narrator, and Herzog-the-self-commentator, my task is not to sort out these different Herzog(s) as truths in themselves. Rather, I treat them as interlocutors and bring them into dialogues with my readings of the films and Heidegger’s philosophy to discuss nature in terms of safe places and hopefully yield some truths. Such a method is prefigured in Plato’s dialogues and buttressed by philosophical hermeneutics, initiated by Heidegger and developed by Hans-Georg Gadamer and Paul Ricoeur. As both Gadamer and Ricoeur insist, reading a text is not about restoring the authorial intentions[6] but rather, as Ricoeur (1991, p. 57) puts in “What is a Text? Explanation and Understanding (1970),” is about “the self-interpretation of a subject who thenceforth understands himself better, understands himself differently, or simply begins to understand himself.” In essence, I will have achieved my goal if some better, different, and new understandings of nature, Herzog and Heidegger emerge as the article unfolds.[7]

2 Modern Enframing of Nature

Heidegger, as Cooper (2005, p. 339) remarks, is “almost the only twentieth-century philosopher of the very first rank to have addressed the issue… of the natural environment.” This may be an overstatement of Heidegger’s value for ecological critique, but it does highlight the worth of such a project. Heidegger’s “ecological critique” derives from his general critique of modernity: the ontological forgetfulness of Being, the epistemological problem of modern science, and the modern technological way of revealing.[8] The ontological critique resides primarily in his foundational work Being and Time (1927), where he points out the forgetfulness of Being throughout the entire Western metaphysical tradition since Plato and aggravated by modernity (Heidegger, 2001a). This forgetfulness of Being means the negligence of our “primordial” relation to the world, others, and ourselves, as the horizon out of which individual entities come into their specific beings. Primordially, Heidegger argues, we are “being-in-the-world” with others, with ourselves, and together as a whole, which precedes the post-Cartesian ontology that espouses the subject and object divide. According to this ontological view, nature, either as “ready-to-hand” equipment or simply that which “stirs and strives,” is with us in a primordial wholeness and not as “present-at-hand” objects standing against us (Heidegger, 2001a, 100).

This primordial wholeness with nature as “being-in-the-world,” however, is shattered by the subject–object division, which underwrites the epistemological outlook of modern science. Calling the modern age “The Age of the World Picture” (1938), Heidegger (1977) argues that the modern epistemological framework, as exemplified by modern science, demarcates humans as the observing subject and the world as the opposite, totalisable object. He says:

The real system of science consists in a solidarity of procedure and attitude with respect to the objectification of whatever is—a solidarity that is brought about appropriately at any given time on the basis of planning (Heidegger, 1977, p. 126).

Hence, for Heidegger, “a solidarity of procedure,” “the objectification of whatever is,” and “planning” characterise modern scientific epistemology: it is “to count only what is measurable and quantifiable as the proper field of scientific enquiry and description” (Cooper, 2005, p. 344). The result is the “scientific” qua objectifying approach to nature that rules out the immeasurable and unquantifiable vitality and heterogeneity of nature and objectifies it as a graspable and totalisable “picture” standing against human beings.

Furthermore, this objectification of nature not only obscures humans’ primordial being with nature but devastatingly reveals nature as a mere exploitable resource. In “The Question Concerning Technology” (1954), Heidegger argues that the essence of technology is not instrumentality but a way of revealing (Heidegger, 1993). Namely, technology is the epistemological machine that frames, or, “enframes” the world for us to understand. Hence, based on measurement and quantification as the epistemology of modern science, modern technology solidifies this epistemology as “the rule of enframing, which demands that nature be orderable as standing-reserve” (Heidegger, 1993, pp. 327–328). Thus technologically revealed, nature is a mere resource for humans to manipulate and exploit, “the world of exploitation” (Sheehan, 2015, p. 258). Or, in Heidegger’s elegy, “‘The Rhine’, as uttered by the art work, in Hölderlin’s hymn,” has become “the power station” and “the vacation industry,” submitted to the “monstrousness that reigns here” (Heidegger, 1993, p. 321 emphasis in original).[9]

Shifting from ontological primordiality to epistemological objectivity and ending up as a technological monstrosity, this vicious teleology seems to underline Heidegger’s critique of the modern human–nature relationship, appearing as an irrevocable and irredeemable degeneration. It is not, however, the whole story. Again, quoting Hölderlin with the line “But where danger is, grows/The saving power also,” Heidegger (1993, pp. 333–337) suggests that “the essential unfolding of technology harbours in itself what we least suspect, the possible rise of the saving power.” Namely, while criticising technology’s monstrous resourcification of nature, Heidegger also acknowledges that technology, as a way of revealing, also harbours the potential of bringing forth the truth of nature, because “there was a time when the bringing-forth of the true into the beautiful was called techne [technics]. The poiesis [poetry] of the fine arts was also called techne” (Heidegger, 1993, p. 339). As Sinnerbrink (2014, p. 70) argues, “cinema as the technological art par excellence” harbours this potential and the saving power of reuniting the techne and poiesis. This is, I argue, what Herzog’s cinema gestures at. Via audio-visual aesthetics, Herzog not only explores the human–nature crisis (Aguirre and Grizzly Man) that makes nature an unsafe place to dwell but also envisages potential solutions, potentially safe ways of dwelling with nature (Happy People).

3 Aguirre as the Most Uncanny/Unhomely

Aguirre tells the story of the Spanish conquistadorial expedition through Amazonia in search of El Dorado, the mythic city of gold. Around one-third of the way through the film, Aguirre, second-in-command, kills Ursúa (Ruy Guerra), the commander of the expedition, and becomes the actual dictator. To dramatise the megalomania, the “irrational thirst for power” (Nagib, 2012, p. 60) of Aguirre, the camera, in medium close-up, frames him like a bust of an ancient Roman emperor displaying a gigantic shoulder and a peremptory facial expression (Figure 3). The shallow focus blows everyone else out of clear view as if Aguirre is the one and only being in the scene. As he disdainfully dares “anyone else,” everyone keeps silent, and the soundtrack is filled only with his footsteps and the noise of nature. However, the noise of nature, the omnipresent and monotonous chirping of birds, the buzzing of insects, and the roaring of the waterfall sound like a response to Aguirre’s challenge or, rather, indifference to it. Its omnipresence and monotony manifest an indifference that disdains to respond to Aguirre, an apathetic gesture that defies his pseudo-omnipotence. In short, the sound of nature ironises the sight of human hubris; and irony is the film’s chief aesthetics that reveals nature’s inhospitality as the outcome of human beings’ exploitative approach towards nature.

Aguirre, like a Roman tyrant, defies any sovereignty except himself.

The deep antagonism between humans and nature is mobilised at the start of the film. As the camera moves closer to the mountain, we can gradually discern, through a veil of mist, a group of people winding down the mountain (Figure 4). Their “cannons, armour, and courtly gowns never seem to fit in the environment” (Carroll, 1998, p. 293). For instance, the redness of their clothes contrasts sharply with the green landscape, implying an animosity between humanity and nature. Moreover, this animosity is intensified by their extremely disproportionate scales. Through the extreme wide shot and deep focus, the camera sculpts the immensity of nature, which terribly overpowers humans on the one hand. Yet, on the other, the formal lining-up of human beings in red looked at from afar conjures up the image of the parasite and the leech, a sinister blood vessel sucking the life of nature. The scene is concluded by a falling cannon (Figure 5). With its explosion, the cannon damages both human and natural property and dynamises the human–nature conflict unfolding throughout the film.

The sharp contrast between humanity and nature in scale and colour.

Human–nature antagonism set on fire.

The development of the film is a rivalrous display of ferocity between nature and humanity. Nature in Aguirre appears as threatening and unnavigable torrents (Figure 6), menacing and impenetrable vegetation, dangerous and beguiling forests full of traps and cannibals, and malicious monkeys ravaging Aguirre’s colonial empire, the sinking raft at the film’s end. No less savage is humanity’s exploitative approach towards nature. The colonisers’ determination to find in it or turn it into El Dorado, the city of gold, is the film’s central narrative drive. Such a drive foregrounds what Heidegger (1993) in the “Technology” essay identifies as modern technological disclosure of nature as a mere resource, the jungle as gold. Via a Heideggerian lens, this common savageness of nature and humanity, however, is not viewed as fundamental and universal, as Trigg (2012) argues, but conditioned by humans’ dwelling with nature. It is humans’ exploitative way of dwelling, represented here as colonisation, that also discloses nature in such a monstrous way. The film, by comparatively and correspondingly showing the monstrosity of nature and that of humans, implies their correlation.

The fierce and chaotic rapids in Aguirre.

In Aguirre, the monstrous resourcification of nature is, ironically, embodied and suffered by two human figures: the native Indian (unnamed) and Flora (Cecilia Rivera), Aguirre’s daughter. The native Indians emerge amicably from the forest and, as such, can be regarded as the representative of nature. When two of them come to the colonisers and treat them as long-awaited gods, the colonisers only see the gold that hangs on the Indian’s neck and see them as no more than the possibility and exploitability of more gold. Hence, they are ruthlessly killed when found unpromising in this regard. Foregrounding the gold necklace in Aguirre’s hand, the composition of the confrontation scene transforms the gold into a synecdoche of the Indian (Figure 7). This reading complements that of Koepnick’s analysis. He interprets violence towards the Indians as an epistemological colonisation which regards them as “welcome objects of colonial Christianization” (Koepnick, 1993, p. 140). Thus,

As soon as the male Indian disappoints the colonial presumptions and, in the eyes of Aguirre’s troop, ridicules the bible, he is murdered: he who strays from preestablished paths of transculturation and transgresses the image of the noble savage, forfeits his right to exist (Koepnick, 1993, p. 140).

The gold as the synecdoche and ontology of the Indian.

My argument thus builds on Koepnick’s critique of objectification. Namely, the native Indians, like the nature they are symbolic of, are fundamentally determined and treated as mere resources, as exploitable and disposable objects. This symbolical portrayal has been described as problematic. Despite Herzog’s critical intention, he still needs to reproduce the colonial stereotype of the indigenous people as natural resources in order to subvert it (Ramey, 2012). Ramey (2012, p. 143) calls this “the paradoxical nature of irony in artistic expression: ironic art purports to mean the opposite of what it says, but it still must say it.” However, as my following analysis shows, within the technological-enframing logic the film critiques, it is not only indigenous people who are enframed as resources.[10]

More telling, and probably more ironic and excruciating, is Aguirre’s final treatment of his daughter, Flora, whose name also connotates nature. At the end of the film, when Flora is shot by an arrow and about to die, Aguirre domineeringly clutches her to his side, like a captured prey. In the shot that becomes the standard poster of the film, Aguirre’s desperation in appropriating Flora is evident in his clutching hands and twice larger size (Figure 8). To sanctify this possession of nature via his daughter, he declares, in delirium, “I, the wrath of God, will marry my own daughter, and with her, found the purest dynasty ever known to man.” Reading this iconic scene as an inverse Pietà, Ames (2016, p. 78) writes, “a figure of innocence [The iconographic reference to the Passion of Christ] thus gives rise to colonial fantasies of power and possession that are as disturbing as they are incestuous.” Thus, the native Indian and Flora, via their dual identity as human beings and nature, ironically show that humans’ exploitation of nature as mere resource backfires upon humanity itself, that “man becomes human material,” as Heidegger writes in “The Thing” (1950), like “the earth and its atmosphere become raw material” (Heidegger, 2001b, p. 109).

Aguirre’s possessive clutch of Flora (nature).

The irony of the film does not stop there. It digs into and satirises the underlying logic that justifies this monstrous resourcification of nature and humanity, which Heidegger (1993) identifies as the objectifying and quantifying worldview modern science upholds. This worldview is simultaneously epitomised and satirised in the figure Guzman (Peter Berling), an obese and impotent nobleman whom Aguirre, after his rebellion, imposes on the team as the new leader, the emperor of their colonial kingdom. While his easy-to-manipulate impotence is clearly the reason why Aguirre chooses Guzman as his puppet, it is his obesity that Aguirre ironically cites as the justification for his enthronement, as he is “the widest and weightiest nobleman,” an objectifiable and quantifiable justification par excellence. Thus, the figure of Guzman, a juxtaposition of obesity and impotence, ironically manifests at once this quantifying worldview and its absurdity.

In the enthronement scene (Figure 9), Guzman is surrounded, not imperially but rather imprisoningly, by the team. The throne, instead of empowering, dwarfs him below all others, accentuating his body fat on the chest and belly. The body fat, the objectifiable and quantifiable warrant of his majesty, helplessly heaps there, laying bare its impotence and absurdity. As if the irony is not sarcastic enough, the scene cuts to a medium close-up of Guzman’s crying (Figure 10), a deliberate visual contrast with Aguirre’s tyrannical appearance (Figure 3). Thus, a visual irony is formed, flipping around Guzman’s impotency and Aguirre’s impetuosity, which articulates a twofold criticism against this exploitative mode of dwelling with nature: the absurdity of its underlining logic of objectification and quantification (Guzman), and the monstrosity of humanity thus motivated (Aguirre).

The enthronement/imprisonment of Guzman, the quantifiable authority.

Guzman crying.

Thus, Aguirre resonates with Heidegger’s critique of modern technology: the transformation of both nature and humanity into mere exploitable resources. In such madness, as Heidegger (1996, p. 75) says in his Hölderlin lecture:

All these things that are attained, taken by themselves, merely incite and drive one to further hunting, and taken by themselves, do not have the propensity for bringing human beings into what is by essence their own.

“Bringing human beings into what is by essence their own,” as Heidegger discovers in his reading of Hölderlin, is to dwell, to be at home with oneself and the world. What the film shows us is the opposite. In the objectification and resourcification of the world, humans and nature become uncanny/unhomely monsters, unsafe for each other.

4 Grizzly Man’s Primordial Encounter with Nature

While Aguirre, via his unhomely mode of dwelling, utterly alienates himself from nature, Timothy Treadwell in Grizzly Man attempts the opposite. His mode of dwelling is underlined by total identification with and being-totally-at-home in nature, a dwelling, however, no less disastrous. Treadwell is a bear enthusiast who was, unfortunately and ironically, killed by a grizzly bear in October 2003, together with his girlfriend, Amie Huguenard. The film reconstructs a biography of Timothy by intercutting Treadwell’s left footage of his life in Alaska with bears and interviews with Treadwell’s friends and parents, people involved with the event, and bear professionals. As Grizzly Man centres on a tragic death by and in nature, the film can be viewed as another demonstration of its brutality, or, as Herzog comments during the film: “I believe the common denominator of the universe is not harmony but chaos, hostility, and murder.” Nature is, again, unhomely and unsafe.

The film demonstrates this unhomeliness not by abstract argumentation but by affective sensations. As Ames (2009, p. 49) puts it, Herzog’s cinema “refers primarily to the inner world of affect and to forms of embodied knowledge.” Grizzly Man conveys a powerful sense of the uncanniness/unhomeliness of nature, not created by the representation of death but rather its absence. Uncannily, it is a death that Treadwell almost captured. When he and Amie were under attack, his camera was running with the lens cap on, yet the audio recorded the whole process. The film does not include the recording but does show a scene in which Herzog listens to it (Figure 11). Noys (2007, p. 39) regards it as “one of the most disturbing scenes in the film” and Wilson (2020, p. 101) reads it as flirting with the “taboo against showing actual death” on screen. As Herzog listens and describes what he hears: “I hear the rain, and I hear Amy…,” the camera, instead of focusing on Herzog, moves ever closer to Jewel Palovak (Figure 12), the owner of the tape, who dares not listen to it. Thus, the scene creates two surrogates for us: Herzog, who listens to the recording for us, and Palovak, who reacts to Herzog’s description and imagines the situation amid the mise-en-scène of her home becoming unhomely.

The lit sight of the living room haunted by the (repressed) sound of dying.

The drama in the mind unfolding on Palovak’s face.

The camera movement invites us to scrutinise Palovak’s facial expressions and join her imagination of the death scene based on Herzog’s description. While denying our direct access to it, Herzog encourages our imagination of it in the most nightmarish way possible, as he later persuades Palovak to destroy the tape. Otherwise, “it will be the white elephant in your room all your life.” He also dissuades Palovak from ever looking at the photos of Treadwell’s remains at the coroners, which he has seen but also did not include in the film. Thus, by deliberately keeping the death unheard and unseen yet assuring us of its uncanniness/unhomeliness, the film aims at a more profound sense of uncanniness/unhomeliness beyond the audiovisual representation. The film stages the death in the theatre of our mind.

Heidegger’s phenomenology of temporality helps to illuminate how this uncanny drama unfolds. Unhappy with the modern scientific conception of time as the composite of measurable unities, Heidegger (2001a) tries to describe our authentic experience of time in Being and Time. He argues that our present is, always already, doubly informed by our expectations of the future and the memories of the past. Moreover, our future expectations are also motivated by our past experiences, while our recollections of the past are no less sharped by our future prospects. Thus, our present life, stretched between the past and the future, is anything but a discrete and qualifiable unit. Heidegger’s metaphor for such an authentic experience of time is “ecstasy,” taking the word’s root meaning in Greek and German as “standing outside.” In Heidegger’s words, “Temporality is the primordial ‘out-side-of-itself’ in and for itself” (Heidegger, 2001a, p. 377 emphasis in original). Thus, we understand the present moment as a simultaneous stepping into the future and the past and, from both positions, back to itself.[11]

The Herzog-listening-to-the-tape scene points to this complex temporal experience the film evokes. Appearing right in the middle of the film, it is foreshadowed by the first half and overshadows the rest. We know Treadwell is dead in the first 10 min of the film. We know this is a death that is anticipated through a friend of his who says it is “not necessarily a surprise,” through a journalist who, during his interview with Treadwell, says to him, “you are about to be killed by a bear,” and even through Treadwell himself who says at the very beginning of the film in one of his footage, that among bears “I may be hurt; I may be killed…they will decapitate me; they will chop me into bits and pieces.” Hence, every image in Treadwell’s footage showing him dwelling with the bears is a ghost that haunts the entire film (Figure 13). It bifurcates into two temporalities of death and is simultaneously inscribed with two grammatic tenses: perfect and past future. It is perfect because every image of Treadwell reminds us that his death is an accomplished fact, that we would not have been watching this film, seeing this particular image, had he been still alive. It is also past future because when the image was recorded, Treadwell was among lethal brutes that could have killed him at every moment, and that very image of him could have been the last. Hence, Death is immanent (perfect) and imminent (past future) in these pieces of footage, and the time of the dead is ecstatic.

Treadwell’s haunted and haunting footage.

Appalled by so affective an unhomeliness, Noys (2007, p. 50) argues that Grizzly Man “risks the dehistoricisation of this nature into mysticism” of primordial and fundamental brutality and hence discourages ecological politics. Although this criticism is aligned with Herzog’s own verdict, I contend that this brutality is not a universal state, “the common denominator” of nature, but a conditioned disclosure of nature via Treadwell’s mode of dwelling that seeks “the primordial encounter with” (Herzog) and total homeliness within nature. “I would be within the physical presence of bears 24 h a day for months at a time,” says Treadwell. It was this fatal proximity that enabled Treadwell to film and disclose nature as such, as a chaotic, hostile, and murderous force. An extreme close-up of the bear, which probably killed him (Figure 14), is a case in point.

The bear that haunts.

Accompanying this shot is Herzog saying: “What haunts me is that in all the faces of all the bears that Treadwell ever filmed, I discovered no kinship, no understanding, no mercy. I see only the overwhelming indifference of nature” (Herzog, 2005 emphasis added). While my argument above sides with Herzog’s discovery of the haunting affect of Treadwell’s image, I disagree with his misattribution of this affect to nature and the over-generalisation of nature as such. The hapticality and palpability of “the overwhelming indifference” diffused through the blank gaze, rough hairs, and audacious nose of the bear are conditioned and disclosed by the closeness of Treadwell’s lens, a dangerous closeness.

While Herzog’s totalising critique of nature is fallacious, the film can be viewed as a reassessment of Heidegger’s vision of the ontological relation with nature. Viewed in Heideggerian terms, Treadwell’s dwelling so dangerously close to nature seems to be an attempt to reverse the modern scientific objectification and technological resourcification of nature, as represented by Aguirre. Treadwell wishes to retrieve the primordial wholeness with nature, a wholeness unbroken by the modern subject-object division. This is, however, a disastrous misreading of Heidegger. For Heidegger, the primordial being-in-the-world rejects the subject–object division but does maintain boundaries and distances between different beings; and one of his foremost criticisms of the modern world is that “all distances in time and space are shrinking” (Heidegger, 2001b, p. 163 emphasis in original).

This “frantic abolition of all distances” (Heidegger, 2001b, p. 163) between humanity and animality is exactly what Treadwell’s primordial reintegration with nature entails. Treadwell starts to yell and behave like a bear, shuns human society, and sacrificially devotes himself to nature: “I would never, ever kill a bear in defence of my own life”; an excellent example of Deleuze and Guattari’s (1987) “becoming-animal” that rejects the hierarchical differentiation between human and animal, a point taken up by Jeong and Andrew’s “Grizzly Ghost: Herzog, Bazin and the Cinematic Animal” (2008). Simultaneously and paradoxically, he is also “anthropomorphising the bears” (Gandy, 2012, p. 537). Treadwell names most of the bears: “Ed,” “Rowdy,” “Mr Chocolate”…, socialises with them as “members of an up-and-coming subadult gang,” and keeps saying “I love you” to them. This seemingly harmonious confusion is, however, problematic, as it jeopardises the dwelling of both humans and animals. On the one hand, Treadwell submits himself to the lethal proximity of bears, and on the other, as an indigenous Alaskan says, “he did more damage to the bears because when you habituate bears to humans, they think all humans are safe.” Ultimately, this problematic confusion culminates in the death of Treadwell, his girlfriend, and the bear that kills them.

In essence, Treadwell’s remembering of the premodern primordial wholeness with nature leads to his dismemberment by nature, a becoming unhomely in being homely. As such, he exemplifies what Heidegger criticises in the Hölderlin lectures as “the adventurer” who:

finds the homely precisely in what is constantly and merely not-homely, in the foreign taken in itself. To put it more precisely: For the heart that seeks adventure, this distinction between the homely and the unhomely is altogether lost. The wilderness becomes the absolute itself and counts as the “fullness of being.” (Heidegger, 1996, p. 75)

Hence, Treadwell’s “primordial encounter” with nature, rather than restoring what Heidegger calls the ontological relation to nature, testifies to the boundary between humans and animals that Heidegger insists on. Many scholars, including Heidegger’s student Derrida (2002) and Heidegger’s editor and translator Krell (1993), have criticised this distinction as dogmatic, unfounded, and even anthropocentric. However, Treadwell’s tragic boundary-crossing dwelling with nature does suggest that such a distinction is necessary. Therefore, both Aguirre’s unhomely alienation from nature and Treadwell’s homely identification with it renders nature unsafe for both humans and nonhumans. What is needed is a balance between utter alienation and total identification, or in Heidegger’s words, a becoming homely in being unhomely. Happy People attempts to show such a vision of a safe dwelling in nature.

5 Happy People’s Lifestyle of Gelassenheit

Happy People, co-directed with Dmitry Vasyukov, documents a year in the life of a group of Russian hunters dwelling in the Siberian Taiga Forest and around the isolated village in Bakhta. This film occupies a significant position not only in Herzog’s filmmaking career but in film history in general. For Herzog, it discovers the balance between homeliness and unhomeliness in dwelling with nature, as shown in Aguirre and Grizzly Man, respectively. I term this balance “active serenity.” Moreover, Happy People is also Herzog’s homage to and dialogue with another legendary filmmaker, Andrei Tarkovsky, whose name is explicitly cited by Herzog in the film. Tarkovsky’s years in the Siberian Taiga have left an indelible mark on his filmmaking (Martin, 2005, p. 17). His nephew, Mikhail Tarkovsky, is the cinematographer and one of the initial conceivers of Happy People.

However, the film is generally overlooked by critics. Filimonova (2016) and Sitnikova (2015) draw on it only as a minor case study and comparative example in their research on the representation of Siberia. Laurie Johnson (2016, pp. 192–194) leaves less than two pages for it in his book-length study of Herzog and slightly dismisses the film as “romanticised stereotypes,” “non-ironic nostalgia for a simpler time,” and “a fairly Orientalist view of the Siberians.” The only genuine appreciation for the film comes from an anthropologist, McCall (2016). Hence, in this section, I aim to put the film on the map of world cinema by demonstrating how it offers a vision of nature as a safe place to dwell through active serenity, as both a dialogue with Tarkovsky and a transformative synthesis of Aguirre and Grizzly Man.

Rather than a restful and utopian stagnation that retreats from the world, the phrase “active serenity” seeks to characterise the dwelling envisioned in this film as a dynamic equilibrium that is actively maintained through careful responses to a world that is in perpetual change. I coin this expression by adapting a key term of the late Heidegger: Gelassenheit [releasement/serenity]. Gelassenheit characterises a calm composure, a non-willing “letting beings be” as an antidote to the modern technological enframing and exploitation of the world (Davis, 2014, p. 171). Such a cinematic Gelassenheit opens Happy People (Figure 15). Foretold by a gentle and mellow music piece, the camera pans slowly and steadily right, disclosing the village in Bakhta, the hunters’ main dwelling place in the Siberian Taiga Forest. This camerawork reveals a psychogeography and cinematography of Gelassenheit, of serene dwelling. A sense of abstraction accentuates this serenity. The sky, the land, and the river look like three horizontal straps on a surface without dimensionality. This abstract form is created by the distance of the shot that levels out the particularities of things and the seasonal lack of light–shadow interplay which is key to our sense of spatial depth. In his landmark study of abstraction in art, Worringer (1953) argues abstraction is an urge toward immortality. Through the negation of individuality and depth and the formation of geometric-crystalline regularity, abstraction “impresses upon [the object] the stamp of eternalisation and wrests it from temporality and arbitrariness” (Worringer, 1953, p. 42). Thus, together with the music and the pan, this aesthetics of abstraction releases the film into a permanent serenity that underlines the natural landscape it depicts.

The Taiga Forest, a psychogeography and cinematography of Gelassenheit.

This serenity, however, is not stagnation. A sense of movement, carried out by the pan, also resides in the imagery of the river. This imagery recalls Heidegger’s interpretation of the river Ister in Hölderlin’s hymn: “The river is the locality for dwelling. The river is the journeying of becoming homely” (Heidegger, 1996, p. 31). As Herzog’s narration explains, “the expanse in the foreground is not solid land but the frozen over Yenisei River.” Namely, appearing in the foreground of the opening shot and reappearing throughout the film, the Yenisei River foregrounds the world of the Taiga, a world that floats and changes with the river rather than resting on a solid base. Its thaw and freeze shape and symbolise a lifestyle governed by and responsive to natural evolution: setting up traps in spring as “the ice covering on the river is still solid” for transportation; with the river thawing, catching pikes and other fishes in summer; harvesting the land nourished by the thawed river in autumn; and travelling through the river, frozen up again, to hunt for sables in winter. Hence, dwelling with the river in Happy People is serenity maintained with responsive activities.

This activity of dwelling breaks forth the category of Gelassenheit, which, as Heidegger (1969, p. 61) argues in Discourse on Thinking (1959), “lies beyond the distinction between activity and passivity.” There may be, as Heidegger (1969, p. 61) suggests, “a higher acting [is] concealed in Gelassenheit than is found in all the actions within the world and in the machinations of all mankind…”. But such an esoteric notion of “higher acting” fails to account for the necessary and concrete activities that the dwelling of Happy People requires. Hence, the film invites us to read more critically about Heidegger’s dismissal of everyday and ordinary activity in Being and Time as “inauthentic.”[12] Revising Heidegger’s initial conception, I add “active” to “serenity” to better characterise the dwelling envisaged in Happy People. [13]

This active and serene dwelling, besides revisioning Heidegger, can also be read as Herzog’s response to and redemption of Tarkovsky’s dwelling caught up in cosmological destruction and renewal. This is Tarkovsky’s final word on cinema: the ending sequence of his final film, The Sacrifice (1986). Pleading God’s mercy to prevent imminent nuclear war, the father burns down his house and takes an oath of eternal silence. Cutting from the burning and falling house (Figure 16), a metaphor for the destruction of a world, the film shows the son carrying a bucket to water a withered tree, a faithful gesture that prays for the miraculous resurrection. Lying beside the tree, the son, in clothing whose colours interplay and intertwine with the environment, speaks for the first time at the end of the film, quoting the first line of the Gospel of John: “In the beginning was the Word. Why is that, Papa?” (Figure 17) Thus, the cut articulates a series of parallelisms: father-son, burning-watering, silence-sound, destruction-rejuvenation, which crystalises Tarkovsky’s cinematic cosmology. It is a cosmos characterised by cyclical destructions and renewals and the intervention of faith that seeks to preserve the world or facilitate its rejuvenation. Dwelling in such a cosmos is always and already in ruination as part of cosmological regeneration. Tarkovsky keeps reiterating this point of ruinating dwelling through the raid and rape of a church by Tatars in Andrei Rublev (Tarkovsky, 1966), the dilapidated and uninhabitable buildings in Stalker (Tarkovsky, 1979) and Nostalgia (Tarkovsky, 1983), and the burning houses in Mirror (Tarkovsky, 1975) and The Sacrifice (Tarkovsky, 1986).

The burning house in The Sacrifice as a metaphor for the apocalypse.

The son as the symbol of rejuvenation.

Like Tarkovsky’s films, Happy People also acknowledges the larger cosmological pattern that dwelling cycles with. Unlike Tarkovsky, however, the film envisages the redemption of dwelling from utter destruction not by divine intervention but by human care. Hence, while I agree with Ivakhiv (2013, p. 111) that there is a “strategy of inserting reminders of the ecology that surrounds and subtends human narrative” in both Herzog and Tarkovsky, I wish to highlight Herzog’s humanism vs Tarkovsky’s theism. Heidegger’s concept of Care sheds light on this point. A key idea in Being and Time, care plays a definitive role in Heidegger’s conception of being human, which entails “the necessity of both careful responsibility for our lives and world and the inevitability, in living, of loss and misfortune” (Scott, 2014, p. 58). We care, because being human, we are essentially being-in-the-world and interconnect with existing beings. This interconnection exposes us to the uncertainty and insecurity of world affairs. The dwelling in the Taiga is no exception. For example, bears, which are idealised and anthropomorphised by Treadwell in Grizzly Man, are, as Herzog’s narration tells us, “the real enemy of the trappers” in Happy People.

Accompanying this comment is a long shot that shows a bear by the far side of a river (Figure 18). While the long shot pushes the bear into the far distance, the composition furthers the distance by setting a river in the foreground as another separation between us and the bear. These cinematic gestures not only visualise the enmity between the trappers and the bears but critically dialogue with the dangerous extreme close-up of the bear in Grizzly Man (Figure 14). Unlike Treadwell, the Russian trappers carefully distance themselves from the bears. This careful distancing, conceptualised through Heideggerian Care, is both “ontic,” meaning the concerted separation with the bears, and also “ontological,” that is, safeguarding one’s humanity against the bears’ animality. This careful distancing, rather than Treadwell’s reckless encounter, brings out what Heidegger means by our primordial wholeness with nature as being-in-the-world that respects the difference and distance between beings.[14] In short, via human Care and not Tarkovsky’s appeal to God, Herzog’s Russian hunters become homely among the unhomeliness of nature.[15]

The bear kept apart.

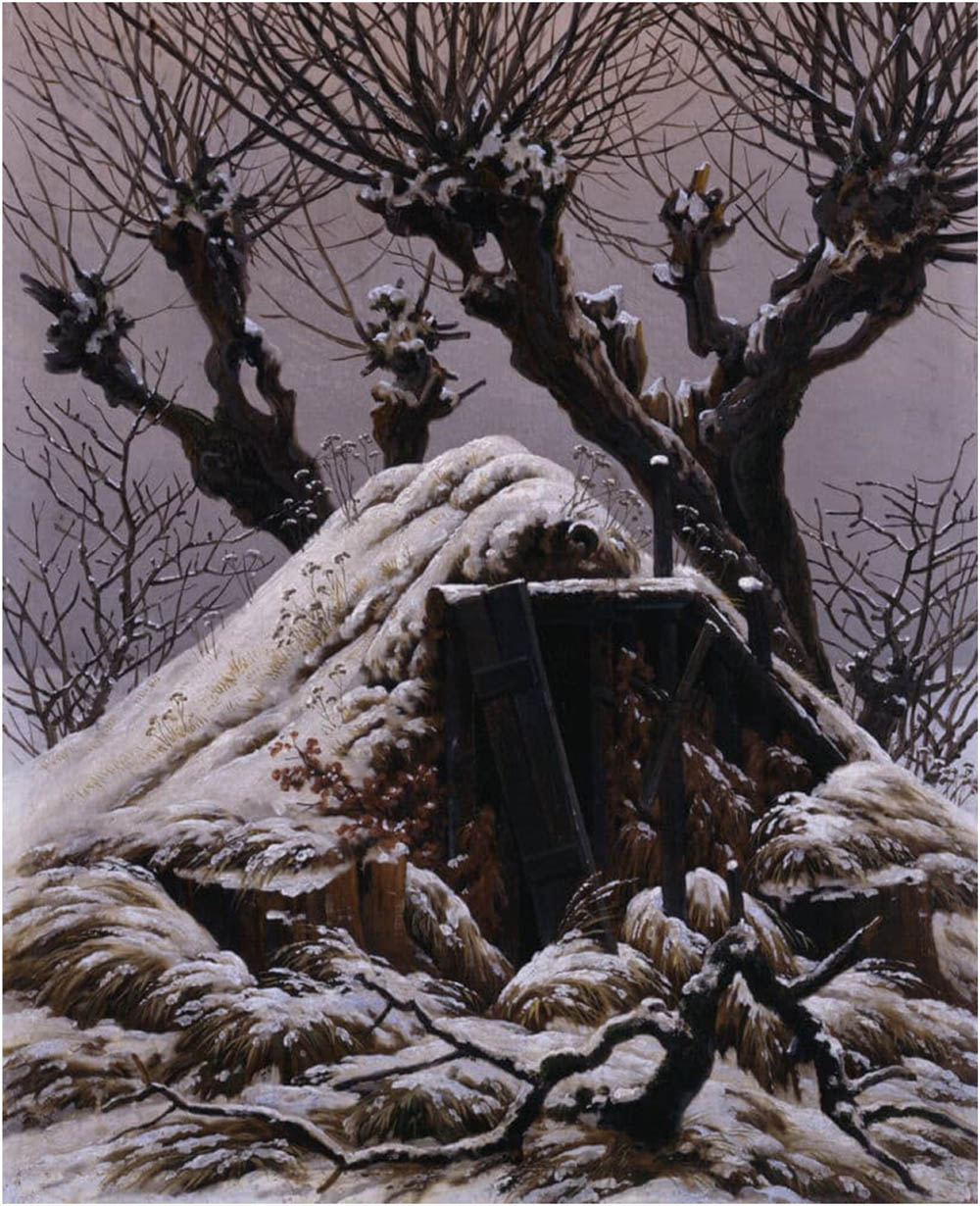

However, bears still “wreck all kinds of havoc to both huts and traps.” The permanent harsh weather and sudden snowstorm also threaten and damage the dwelling in the Taiga Forest. The unhomeliness of nature is inevitable. The snow-buried hut (Figure 19), which resembles those ruined houses in Tarkovsky’s films, is a case in point. Nevertheless, unlike Tarkovsky, who dramatises this ruination as an existential crisis, and whose characters resort to God as the only salvation, Herzog shows Gennady, the owner of the hut, treating his ruined dwelling place not as an apocalypse but as a common misfortune. His attitude exemplifies both Gelassenheit, the serene acceptance of the unavoidable unhomeliness of nature, and the active responsibility that he takes for his dwelling place. Patiently and carefully, he repairs the hut, shovelling away the snow, hacking down the fallen tree, and resetting the chimney. The hand-held camera, with its mobility, travels with Gennady inside and outside of the building and reveals to us its reconstruction. This documentary technique allows us a semi-presence in the situation, conveying a deeper sense of building and dwelling in the Taiga, its vicissitude and vitality, activity and serenity.

The snow-buried hut as the home becoming unhomely.

The camera, as a disclosive engine, analyses and analogises how the hunter’s technologies function as a means of revealing. The shovel, the axe, and the chimney, more than facilitating Gennady’s building, also reveal his being as a negotiation with nature, both deeply intertwined with it and clearly distinguished from it. The shovel shows the threat of the snow and his reaction to it; the axe illustrates the mutual damage that the tree and the man can bring to each other; the chimney demonstrates his need for the warmth of the inside and atmospheric link with the outside. In essence, they echo Heidegger’s definition of technology as a way of revealing and reveal the homely–unhomely ambivalence inherent to dwelling.

Moreover, Gennady’s way of revealing nature contrasts sharply with Aguirre’s enframing nature as a mere exploitable resource. As he says early in the film: “we all agree that greed is the trapper’s worst quality,” referring to the hunters who set up the traps so early that they make “a few coins at any price.” This criticism distinguishes the dwelling with nature in Happy People from the reductive and quantifying approach to nature, as represented in Aguirre. Although the hunters also take resources from nature, their mode of active and serene dwelling reveals its tranquil and celestial beauty. As one of them explains, coming into the Taiga is a dream-fulfilling experience because “you enjoy the beauty of nature and you do your job at the same time.” Preceding this comment is a series of shots that interweave exquisite close-ups (Figure 20) and sublime wide shots (Figure 21) of the splendid nature with people calmly and actively dwelling in their hardships (Figures 22 and 23).

Fiery twigs across icicles.

The grandiose meandering of the river.

A hunter with his dog in a wintry scenery.

A hut merging into the forest twilight.

The camera, gracefully cutting through these scenes, zooming in and out, and wallowing in a soundscape that mixes delicate natural sounds such as trickling springs and a lyrical piece of harp music, articulates a waltz between humans and nature, mediating between hardship and delicacy, activity and serenity. This sequence exemplifies what Pasolini (1976) theorises as the “cinema of poetry”; that is, cinematic apparatuses become indirect speakers for the characters and reveal their inner visions. Revealed thusly by Happy People, a cinema of poetry, nature manifests as splendid sceneries that echo the mode of dwelling which reveals it, contrasting with the ferocious and haunting nature in Aguirre and Grizzly Man. Therefore, far from being simplistic, stereotypical, and orientalist, as Johnson (2016) contends, Happy People offers a sophisticated vision of active serenity. Such a vision redeems Tarkovsky’s dwelling in ruination, carefully balances between Aguirre’s total alienation from nature and Grizzly Man’s utter identification with nature, between unhomeliness and homeliness, and poetically reveals nature as a safe place brimming with splendour.

6 Back to the Sea of Fog

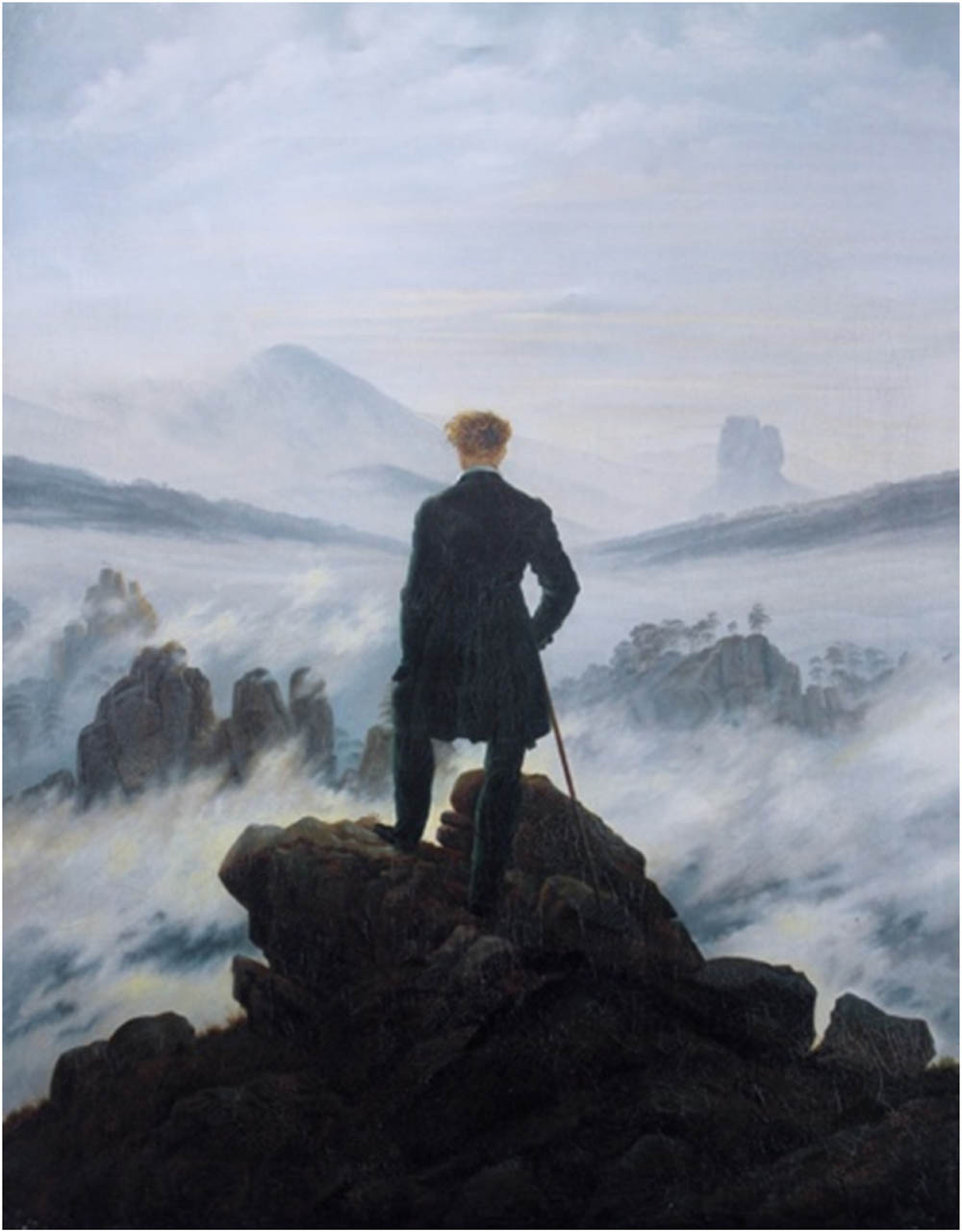

I began this article with an image of a sea of fog (Figure 1), and I will end it with another such image, probably the most famous on this subject: Wanderer above the Sea of Fog by Caspar David Friedrich (1818) (Figure 24). As Herzog tells Cronin (Cronin & Herzog, 2014, p. 142), Friedrich is “someone I do have great affinity for.” A sea of fog surges from the middle ground and spreads across the mountains and ravines until it integrates with the vast and boundless sky at the horizon. It is the archetype of Herzog’s unframeable nature, and the fog scene in Heart of Glass is a visual homage to it. More importantly, what foregrounds and centres the painting is a man standing majestically and calmly before the stupendous landscape, with his hair blown by the wind and flowing with the fog: a paramount example of dwelling with nature as active serenity. “Friedrich didn’t paint landscapes per se,” as Herzog says, “he revealed inner landscapes to us, ones that exist only in our dreams. It’s something I have always tried to do with my films (Cronin & Herzog, 2014, p. 142).” Figure 19, discussed above, also bears an unmistakable trace of Friedrich’s Cabin in the Snow (1827; Figure 25). Both show that the painter and filmmaker are more than aware of the precarity of dwelling with nature. Following this romantic lineage, we can speculate that Wanderer reveals an inner landscape of active serenity that Herzog’s Heart still lacks, and this lack anchors Herzog’s cinematic voyage towards it.

Wanderer above the Sea of Fog.

Cabin in the Snow.

In this article, I uncovered and undertook a voyage that explored the inner landscape of dwelling with nature with Heidegger’s philosophy and three films by Herzog: Aguirre, Grizzly Man, and Happy People. I conclude that, through these films, we can experience dwelling with nature as a struggle to balance apathy and empathy, between unhomeliness and homeliness. As such, my argument intervenes in the apathy-empathy aporia that structures and blockades the discussions of the human–nature relation in Herzog scholarship. Instead of essentialising and binarising this relation as either apathy or empathy, I, via a Heideggerian reading of Herzog, conceptualised this relation as an on-going negotiation and exploration in Herzog’s cinema, depending on the different modalities of dwelling.

As the companion of this cinematic voyage with Herzog, Heidegger’s philosophy has also been clarified and revised through the journey. Aguirre animates and ironises what Heidegger criticises as the modern technological enframing of nature as a mere resource according to scientific objectification and quantification. The comparison between the dwelling in Grizzly Man and that in Happy People helped to clarify Heidegger’s ontological relation to nature as being-in-the-world. What Heideggerian insight suggests is not the transgression of the boundary, as Treadwell tragically attempted, but the proper distance, as the Russian hunters carefully maintain. Finally, the active serenity of Happy People both reflected and rearticulated the Heideggerian notion of Gelassenheit as active serenity. In a nutshell, nature can be a safe place for us to dwell if we carefully and firmly sustain a vigorous equanimity within its perpetually changing landscape, like a wanderer above a sea of fog.

Acknowledgements

This article has been incubated for a long time and has thus accumulated many debts. First, it derives from the first chapter of my MPhil thesis, of which Martin A. Ruehl is the supervisor. Laura McMahon and Catherine Wheatley examined and helped to improve the thesis. The rewriting spans my DAAD scholarship at Heidelberg University and my PhD studies at the University of Cambridge, funded by the Queens’-Daim Zainuddin Scholarship. Cecília Mello and my PhD supervisor, Isabelle McNeill, offered crucial emotional and intellectual support during the darkest time of revising the piece. The two anonymous reviewers’ feedback is extremely dedicated and rigorous, which helped me clarify some essential aspects of my argument. Robbie Spiers, with whom I discuss most of my ideas, has proofread the piece twice. All errors and blind spots left are mine.

-

Author contribution: The author confirms the sole responsibility for the conception of the study, presented results, and manuscript preparation.

-

Conflict of interest: Author states no conflict of interest.

References

Ames, E. (2009). Herzog, landscape, and documentary. Cinema Journal, 48(2), 49–69. doi: 10.1353/cj.0.0080.Suche in Google Scholar

Ames, E. (2016). Aguirre, the wrath of god. British Film Institute.Suche in Google Scholar

Barber, J. (2015). Desire, incomprehensibility, and despair in the antarctic vision of Werner Herzog. Ecozon@, 6(2), 142–156.Suche in Google Scholar

Carroll, N. (1998). Interpreting the moving image. Cambridge University Press.Suche in Google Scholar

Cooper, D. E. (2005). Heidegger on nature. Environmental Values, 14(3), 339–351.Suche in Google Scholar

Cronin, P., & Herzog, W. (2002). Herzog on Herzog. Faber & Faber.Suche in Google Scholar

Cronin, P., & Herzog, W. (2014). Werner Herzog: A guide for the perplexed. Faber & Faber.Suche in Google Scholar

Davis, B. W. (2014). Will and Gelassenheit. In B. W. Davis (Ed.), Martin Heidegger: Key concepts (pp. 168–182). Routledge.Suche in Google Scholar

Deleuze, G., & Guattari, F. (1987). A thousand plateaus: Capitalism and schizophrenia (B. Massumi, Trans.). University of Minnesota Press.Suche in Google Scholar

Derrida, J. (2002). The animal that therefore I am (more to follow) (D. Wills, Trans.). Critical Inquiry, 28(2), 369–418.Suche in Google Scholar

Eldridge, R. T. (2019). Werner Herzog: Filmmaker and philosopher. Bloomsbury Academic.Suche in Google Scholar

Filimonova, T. (2016). Constructing happiness in Siberia: Happy People and the ideological potential of the provinces. Studies in Russian and Soviet Cinema, 10(3), 206–222. doi: 10.1080/17503132.2016.1218621.Suche in Google Scholar

Freud, S. (2003). The uncanny (D. McLintock, Trans.). Penguin.Suche in Google Scholar

Friedrich, C. D. (1818). Wanderer above the Sea of Fog [Oil Paint]. Hamburger Kunsthalle.Suche in Google Scholar

Friedrich, C. D. (1827). Cabin in the snow [Oil on canvas]. Alte Nationalgalerie.Suche in Google Scholar

Furstenau, M. (2020). Nature and natural meaning in Grizzly Man. In M. B. Wilson & C. Turner (Eds.), The philosophy of Werner Herzog (pp. 69–94). Lexington Books.Suche in Google Scholar

Gadamer, H. G. (1994). Heidegger’s ways (J. W. Stanley, Trans.). State University of New York Press.Suche in Google Scholar

Gadamer, H. G. (2004). Truth and method (J. Weinsheimer & D. G. Marshall, Trans.). Continuum.Suche in Google Scholar

Gandy, M. (2012). The melancholy observer: Landscape, neo-romanticism, and the politics of documentary filmmaking. In B. Prager (Ed.), A companion to Werner Herzog (pp. 528–546). Wiley-Blackwell.Suche in Google Scholar

Heidegger, M. (1969). Discourse on thinking (J. M. Anderson & E. H. Freund, Trans.). Harper & Row.Suche in Google Scholar

Heidegger, M. (1977). The age of the world picture. In W. Lovitt (Ed. & Trans.), The question concerning technology and other essays (pp. 115–154). Harper & Row.Suche in Google Scholar

Heidegger, M. (1993). Basic writings: Martin Heidegger (D. F. Krell, Ed.). HarperCollins.Suche in Google Scholar

Heidegger, M. (1993). The question concerning technology. In D. F. Krell (Ed.) & W. Lovitt (Trans.), Basic writings: Martin Heidegger (pp. 311–341). HarperCollins.Suche in Google Scholar

Heidegger, M. (1996). Hölderlin’s hymn ‘The Ister’ (W. McNeill & J. Davis, Trans.). Indiana University Press.Suche in Google Scholar

Heidegger, M. (2001a). Being and time (J. Macquarrie & E. Robinson, Trans.). Blackwell.Suche in Google Scholar

Heidegger, M. (2001b). The thing. In A. Hofstadter (Ed. & Trans.), Poetry, language, thought (pp. 163–184). HarperCollins.Suche in Google Scholar

Herzog, W. (Director). (1972). Aguirre, the Wrath of God. Filmverlag der Autoren.Suche in Google Scholar

Herzog, W. (Director). (1976). Heart of glass. Werner Herzog Filmproduktion.Suche in Google Scholar

Herzog, W. (Director). (2005). Grizzly Man. Lions Gate Films.Suche in Google Scholar

Herzog, W., & Vasyukov, D. (Directors). (2010). Happy People: A Year in the Taiga. Netflix.Suche in Google Scholar

Horak, J. C. (1979). Werner Herzog’s Écran Absurde. Literature/Film Quarterly, 7(3), 223–234.Suche in Google Scholar

Ivakhiv, A. J. (2013). Ecologies of the moving image: Cinema, affect, nature. Wilfrid Laurier University Press.Suche in Google Scholar

Jeong, S. H., & Andrew, D. (2008). Grizzly ghost: Herzog, Bazin and the cinematic animal. Screen, 49(1), 1–12. doi: 10.1093/screen/hjn001.Suche in Google Scholar

Johnson, L. R. (2016). Forgotten dreams: Revisiting romanticism in the cinema of Werner Herzog. Camden House.Suche in Google Scholar

Karalis, V. (2023). Theo Angelopoulos: Filmmaker and philosopher. Bloomsbury Academic.Suche in Google Scholar

Koepnick, L. P. (1993). Colonial Forestry: Sylvan Politics in Werner Herzog’s Aguirre and Fitzcarraldo. New German Critique, 60, 133–159. doi: 10.2307/488669.Suche in Google Scholar

Ladino, J. K. (2009). For the Love of Nature: Documenting Life, Death, and Animality in ‘Grizzly Man’ and ‘March of the Penguins’. Interdisciplinary Studies in Literature and Environment, 16(1), 53–90.Suche in Google Scholar

Martin, S. (2005). Andrei Tarkovsky. Kamera Books.Suche in Google Scholar

McCall, G. S. (2016). Happy People: A Year in the Taiga. Lithic Technology, 41(3), 252–254. doi: 10.1080/01977261.2016.1208380.Suche in Google Scholar

Moore, I. A. (2020). The Great Ecstasy of Werner Herzog: Truth, Heidegger, Apocalypse. In M. B. Wilson & C. Turner (Eds.), The philosophy of Werner Herzog (pp. 135–152). Lexington Books.Suche in Google Scholar

Mugerauer, R. (2008). Heidegger and homecoming: The leitmotif in the later writings. University of Toronto Press.Suche in Google Scholar

Nagib, L. (2012). Physicality, difference, and the challenge of representation: Werner Herzog in the light of the New Waves. In B. Prager (Ed.), A companion to Werner Herzog (pp. 58–79). Wiley-Blackwell.Suche in Google Scholar

Noys, B. (2007). Antiphusis: Werner Herzog’s Grizzly Man. Film-Philosophy, 11(3), 38–51.Suche in Google Scholar

Pasolini, P. P. (1976). The cinema of poetry. In B. Nichols (Ed.), M. de Vettimo & J. Bontemps (Trans.), Movies and methods (Vol. 1, pp. 542–558). University of California Press.Suche in Google Scholar

Prager, B. (2007). The cinema of Werner Herzog: Aesthetic ecstasy and truth. Columbia University Press.Suche in Google Scholar

Ramey, J. (2012). Representational Imperialism in Aguirre, The Wrath of God. The Latin Americanist, 56(2), 137–159. doi: 10.1111/j.1557-203X.2012.01153.x.Suche in Google Scholar

Ricoeur, P. (1984a). Time and narrative (K. McLaughlin & D. Pellauer, Trans.; Vol. 1). The University of Chicago Press.Suche in Google Scholar

Ricoeur, P. (1984b). Time and narrative (K. Blarney & D. Pellauer, Trans.; Vol. 3). The University of Chicago Press.Suche in Google Scholar

Ricoeur, P. (1991). What is a text? Explanation and understanding (1970). In M. Valdes (Ed.) & J. B. Thompson (Trans.), A Ricoeur reader: Reflection and imagination (pp. 43–64). University of Toronto Press.Suche in Google Scholar

Safranski, R. (1998). Martin Heidegger: Between good and evil (E. Osers, Trans.). Harvard University Press.Suche in Google Scholar

Sass, L. A. (1992). Heidegger, schizophrenia and the ontological difference. Philosophical Psychology, 5(2), 109–132. doi: 10.1080/09515089208573047.Suche in Google Scholar

Sass, L. A. (2017). Madness and modernism: Insanity in the light of modern art, literature, and thought (Revised ed.). Oxford University Press.Suche in Google Scholar

Sass, L. A. (2021). Everywhere and nowhere: Reflections on phenomenology as impossible and indispensable (in psychology and psychiatry). Critical Inquiry, 47(3), 544–564. doi: 10.1086/713545.Suche in Google Scholar

Scott, C. E. (2014). Care and authenticity. In B. W. Davis (Ed.), Martin Heidegger: Key concepts (pp. 57–68). Routledge.Suche in Google Scholar

Sheehan, T. (2015). Making sense of Heidegger: A paradigm shift. Rowman & Littlefield International.Suche in Google Scholar

Sinnerbrink, R. (2014). Technē and poiēsis: On Heidegger and film theory. In A. van den Oever (Ed.), Technē/technology: Researching cinema and media technologies – Their development, use, and impact (pp. 65–80). Amsterdam University Press.Suche in Google Scholar

Sirk, D. (Director). (1955). All that heaven allows. Universal Pictures.Suche in Google Scholar

Sitnikova, A. (2015). The image of Siberia in Soviet, Post-Soviet fiction and Werner Herzog’s documentary films. Journal of Siberian Federal University. Humanities & Social Sciences, 8, 677–706. doi: 10.17516/1997-1370-2015-8-4-677-706.Suche in Google Scholar

Tarkovsky, A. (Director). (1966). Andrei Rublev. Columbia Pictures.Suche in Google Scholar

Tarkovsky, A. (Director). (1975). Mirror. Mosfilm.Suche in Google Scholar

Tarkovsky, A. (Director). (1979). Stalker. Goskino.Suche in Google Scholar

Tarkovsky, A. (Director). (1983). Nostalgia. Gaumont.Suche in Google Scholar

Tarkovsky, A. (Director). (1986). The sacrifice. Sandrew.Suche in Google Scholar

Trigg, D. (2012). The flesh of the forest: Wild being in Merleau-Ponty and Werner Herzog. Emotion, Space and Society, 5(3), 141–147. doi: 10.1016/j.emospa.2011.06.003.Suche in Google Scholar

Wilson, M. B. (2020). Reflections from the Abyss: Herzog’s philosophy of death. In M. B. Wilson & C. Turner (Eds.), The philosophy of Werner Herzog (pp. 95–116). Lexington Books.Suche in Google Scholar

Wolin, R. (2022). Heidegger in ruins: Between philosophy and ideology. Yale University Press.Suche in Google Scholar

Worringer, W. (1953). Abstraction and empathy: A contribution to the psychology of style (M. Bullock, Trans.). Routledge.Suche in Google Scholar

© 2024 the author(s), published by De Gruyter

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Special Issue: Critical Green Theories and Botanical Imaginaries: Exploring Human and More-than-human World Entanglements, edited by Peggy Karpouzou and Nikoleta Zampaki (National and Kapodistrian University of Athens, Greece)

- Critical Green Theories and Botanical Imaginaries: Exploring Human and More-than-Human World Entanglements

- On Vegetal Geography: Perspectives on Critical Plant Studies, Placism, and Resilience

- The Soil is Alive: Cultivating Human Presence Towards the Ground Below Our Feet

- Relational Transilience in the Garden: Plant–Human Encounters in More-than-Human Life Narratives

- “Give It Branches & Roots”: Virginia Woolf and the Vegetal Event of Literature

- Botanical imaginary of indigeneity and rhizomatic sustainability in Toni Morrison’s A Mercy

- Blood Run Beech Read: Human–Plant Grafting in Kim de l’Horizon’s Blutbuch

- “Can I become a tree?”: Plant Imagination in Contemporary Indian Poetry in English

- Gardens in the Gallery: Displaying and Experiencing Contemporary Plant-art

- From Flowers to Plants: Plant-Thinking in Nineteenth-Century Danish Flower Painting

- Becoming-with in Anicka Yi’s Artistic Practice

- Call of the Earth: Ecocriticism Through the Non-Human Agency in M. Jenkin’s “Enys Men”

- Plants as Trans Ecologies: Artifice and Deformation in Bertrand Mandico’s The Wild Boys (2017)

- Ecopoetic Noticing: The Intermedial Semiotic Entanglements of Fungi and Lichen

- Entering Into a Sonic Intra-Active Quantum Relation with Plant Life

- Listening to the Virtual Greenhouse: Musics, Sounding, and Online Plantcare

- Decolonising Plant-Based Cultural Legacies in the Cultural Policies of the Global South

- Special Issue: Safe Places, edited by Diana Gonçalves (Universidade Católica Portuguesa, Portugal) and Tânia Ganito (University of Lisbon, Portugal)

- On Safe Places

- Tracing Exilience Through Literature and Translation: A Portuguese Gargantua in Paris (1848)

- Safe Places of Integration: Female Migrants from Eurasia in Lisbon, Portugal

- “We Are All the Sons of Abraham”? Utopian Performativity for Jewish–Arab Coexistence in an Israeli Reform Jewish Mimouna Celebration

- Mnemotope as a Safe Place: The Wind Phone in Japan

- Into the Negative (Space): Images of War Across Generations in Portugal and Guinea-Bissau. Death is Not the End

- Dwelling in Active Serenity: Nature in Werner Herzog’s Cinema

- Montana as Place of (Un)Belonging: Landscape, Identity, and the American West in Bella Vista (2014)

- Data that Should Not Have Been Given: Noise and Immunity in James Newitt’s HAVEN

- Special Issue: Cultures of Airborne Diseases, edited by Tatiana Konrad and Savannah Schaufler (University of Vienna, Austria)

- Ableism in the Air: Disability Panic in Stephen King’s The Stand

- Airborne Toxicity in Don DeLillo’s White Noise

- Eco-Thrax: Anthrax Narratives and Unstable Ground

- Vaccine/Vaccination Hesitancy: Challenging Science and Society

- Considerations of Post-Pandemic Life

- Regular Articles

- A Syphilis-Giving God? On the Interpretation of the Philistine’s Scourge

- Historical Perceptions about Children and Film: Case Studies of the British Board of Film Censors, the British Film Institute, and the Children’s Film Foundation from the 1910s to the 1950s

- Strong and Weak Theories of Capacity: Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick, Disability, and Contemporary Capacity Theorizing

- Arabicization via Loan Translation: A Corpus-based Analysis of Neologisms Translated from English into Arabic in the Field of Information Technology

- Unraveling Conversational Implicatures: A Study on Arabic EFL Learners

- Noise in the “Aeolus” Episode in Joyce’s Ulysses: An Exploration of Acoustic Modernity

- Navigating Cultural Landscapes: Textual Insights into English–Arabic–English Translation

- The Role of Context in Understanding Colloquial Arabic Idiomatic Expressions by Jordanian Children

- All the Way from Saudi Arabia to the United States: The Inspiration of Architectural Heritage in Art

- Smoking in Ulysses

- Simultaneity of the Senses in the “Sirens” Chapter: Intermediality and Synaesthesia in James Joyce’s Ulysses

- Cultural Perspectives on Financial Accountability in a Balinese Traditional Village

- Marriage Parties, Rules, and Contract Expressions in Qur’an Translations: A Critical Analysis

- Value Perception of the Chronotope in the Author’s Discourse (Based on the Works of Kazakh Authors)

- Cartography of Cultural Practices and Promoting Creative Policies for an Educating City

- Foreign Translators Group in the PRC From 1949 to 1966: A STP Perspective

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Special Issue: Critical Green Theories and Botanical Imaginaries: Exploring Human and More-than-human World Entanglements, edited by Peggy Karpouzou and Nikoleta Zampaki (National and Kapodistrian University of Athens, Greece)

- Critical Green Theories and Botanical Imaginaries: Exploring Human and More-than-Human World Entanglements

- On Vegetal Geography: Perspectives on Critical Plant Studies, Placism, and Resilience

- The Soil is Alive: Cultivating Human Presence Towards the Ground Below Our Feet

- Relational Transilience in the Garden: Plant–Human Encounters in More-than-Human Life Narratives

- “Give It Branches & Roots”: Virginia Woolf and the Vegetal Event of Literature

- Botanical imaginary of indigeneity and rhizomatic sustainability in Toni Morrison’s A Mercy

- Blood Run Beech Read: Human–Plant Grafting in Kim de l’Horizon’s Blutbuch

- “Can I become a tree?”: Plant Imagination in Contemporary Indian Poetry in English

- Gardens in the Gallery: Displaying and Experiencing Contemporary Plant-art

- From Flowers to Plants: Plant-Thinking in Nineteenth-Century Danish Flower Painting

- Becoming-with in Anicka Yi’s Artistic Practice

- Call of the Earth: Ecocriticism Through the Non-Human Agency in M. Jenkin’s “Enys Men”

- Plants as Trans Ecologies: Artifice and Deformation in Bertrand Mandico’s The Wild Boys (2017)

- Ecopoetic Noticing: The Intermedial Semiotic Entanglements of Fungi and Lichen

- Entering Into a Sonic Intra-Active Quantum Relation with Plant Life

- Listening to the Virtual Greenhouse: Musics, Sounding, and Online Plantcare

- Decolonising Plant-Based Cultural Legacies in the Cultural Policies of the Global South

- Special Issue: Safe Places, edited by Diana Gonçalves (Universidade Católica Portuguesa, Portugal) and Tânia Ganito (University of Lisbon, Portugal)

- On Safe Places

- Tracing Exilience Through Literature and Translation: A Portuguese Gargantua in Paris (1848)

- Safe Places of Integration: Female Migrants from Eurasia in Lisbon, Portugal

- “We Are All the Sons of Abraham”? Utopian Performativity for Jewish–Arab Coexistence in an Israeli Reform Jewish Mimouna Celebration

- Mnemotope as a Safe Place: The Wind Phone in Japan

- Into the Negative (Space): Images of War Across Generations in Portugal and Guinea-Bissau. Death is Not the End

- Dwelling in Active Serenity: Nature in Werner Herzog’s Cinema

- Montana as Place of (Un)Belonging: Landscape, Identity, and the American West in Bella Vista (2014)

- Data that Should Not Have Been Given: Noise and Immunity in James Newitt’s HAVEN

- Special Issue: Cultures of Airborne Diseases, edited by Tatiana Konrad and Savannah Schaufler (University of Vienna, Austria)

- Ableism in the Air: Disability Panic in Stephen King’s The Stand

- Airborne Toxicity in Don DeLillo’s White Noise

- Eco-Thrax: Anthrax Narratives and Unstable Ground

- Vaccine/Vaccination Hesitancy: Challenging Science and Society

- Considerations of Post-Pandemic Life

- Regular Articles

- A Syphilis-Giving God? On the Interpretation of the Philistine’s Scourge

- Historical Perceptions about Children and Film: Case Studies of the British Board of Film Censors, the British Film Institute, and the Children’s Film Foundation from the 1910s to the 1950s

- Strong and Weak Theories of Capacity: Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick, Disability, and Contemporary Capacity Theorizing

- Arabicization via Loan Translation: A Corpus-based Analysis of Neologisms Translated from English into Arabic in the Field of Information Technology

- Unraveling Conversational Implicatures: A Study on Arabic EFL Learners

- Noise in the “Aeolus” Episode in Joyce’s Ulysses: An Exploration of Acoustic Modernity

- Navigating Cultural Landscapes: Textual Insights into English–Arabic–English Translation

- The Role of Context in Understanding Colloquial Arabic Idiomatic Expressions by Jordanian Children

- All the Way from Saudi Arabia to the United States: The Inspiration of Architectural Heritage in Art

- Smoking in Ulysses

- Simultaneity of the Senses in the “Sirens” Chapter: Intermediality and Synaesthesia in James Joyce’s Ulysses

- Cultural Perspectives on Financial Accountability in a Balinese Traditional Village

- Marriage Parties, Rules, and Contract Expressions in Qur’an Translations: A Critical Analysis

- Value Perception of the Chronotope in the Author’s Discourse (Based on the Works of Kazakh Authors)

- Cartography of Cultural Practices and Promoting Creative Policies for an Educating City

- Foreign Translators Group in the PRC From 1949 to 1966: A STP Perspective