Abstract

This study investigates the relationship between architectural heritage in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia and the United States, providing insights for place-based learning (PBL). The researcher analyzes the similarities and differences between New Mexico (NM) and Saudi Arabia, such as materials, color, and motif units, to design and apply them to develop a range of modern designs. The study method used is an experiential approach based on a case study, based on the author’s living experience in NM from 2014 to 2018, visiting museums and heritage areas, taking photographs, and tasting the culture. Moreover, this study includes a literature review for PBL. In addition, the research study uses a descriptive and experimental method and practical procedure by designing, borrowing, and analyzing the inspiration of specific traditions and integrating both cultures into artworks and ornaments in weaving beads and textiles. The result of the study applied six innovative designs by creating art projects through experimental learning. The result presented three themes: (1) similarities in instructions, materials, and colors of the architectural heritage between the Santa Fe and Saudi Najd styles, (2) differences between the architectural heritage doors, windows, and roof system, and (3) drawing inspiration from architectural heritage for textile bead weaving designs.

1 Introduction

Heritage expresses the connection between people, land, and their culture. It connects the present with the past and heralds a bright future. It is a way of acquiring knowledge, experience, and skills and allows for innovation, growth, and renewal, representing individual and group identity, a sense of place, and a sense of belonging (Smith, 2022). In other words, it refers to a community’s culture transmitted from one generation to another. Alzahrani (2022) has stated that heritage is the cultural elements transmitted from one generation to another. It refers to the results of civilization in all fields of human activity, including social and economic heritage, indicating the type of life our ancestors lived regarding their customs, traditions, and buildings. Heritage brings together culture, identity, and the past (Maruyama et al., 2008) and provides a framework for addressing social and economic problems. The principle of heritage development refers to cultivating heritage to strengthen community identity and promote economic development (William, 2013). Many experts have studied the developmental role of heritage and stressed that governments significantly contribute to achieving this development. Aljahani (2019) stated that every society knows its identity, distinguishing it from other cultures. Heritage identifies a community’s position in the world and its relations with other communities, which is shaped by cultural factors and accumulated throughout its history and can be both moral and material.

In general, heritage is a source of inspiration and reference for designers. Communities possess an abundance of architectural heritage that designers can use as inspiration, such as historic buildings, town sites, important archeological sites, and monumental sculptures and paintings (Aljahani, 2019). Saudi Vision 2030 encourages designers to explore new sources of material folklore and heritage that have not been studied previously. The Kingdom of Saudi Arabia’s (KSA’s) Ministry of Culture is using the framework of Saudi Vision 2030 to support the Kingdom’s cultural sector. The framework identifies three central objectives: (1) Promoting culture as a way of life; (2) enabling culture to contribute to economic growth; and 3) creating opportunities for international cultural exchange (The Ministry of Culture, 2019).

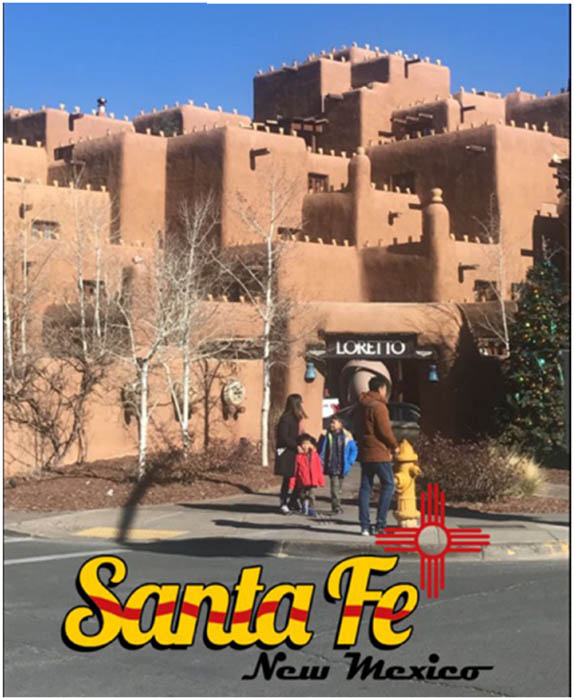

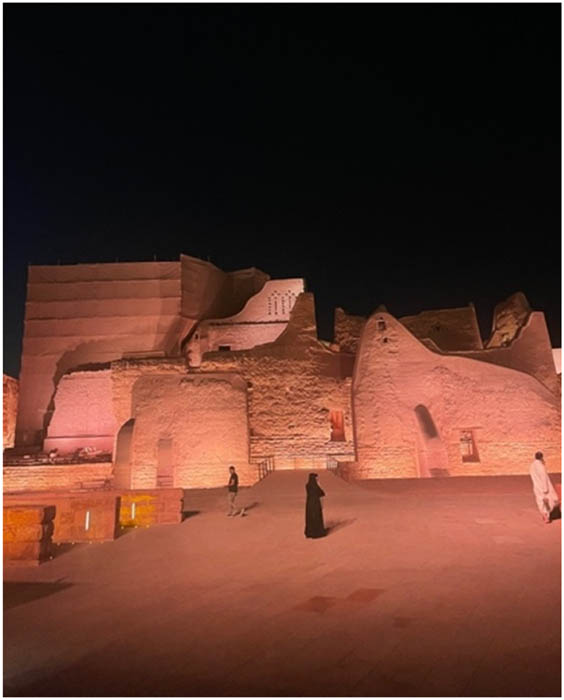

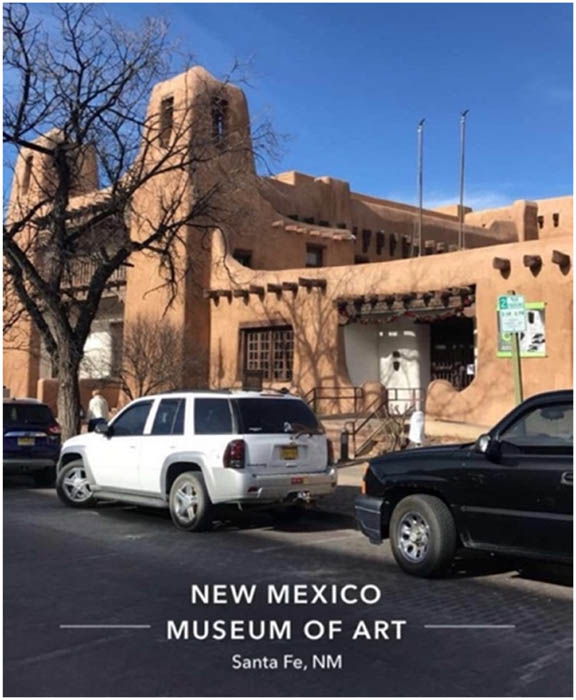

Saudi Arabia has a visitors’ center located at the Ad-Dir’iyah heritage site, a significant place for the cultural and political history of the Arabian Peninsula (Aljahani, 2019). The United States has a similar site at the New Mexico (NM) History Museum, a unique marketplace established under the portal of the important palace of the governors in Santa Fe. This place has enabled various arts to come to life throughout the city, both within the indoor galleries and historic architectural buildings and through performances that celebrate the heritage of the area (Lovato, 2004). Thus, the market celebrates culture and contributes to economic growth. Indian artists are seated with their backs against the front wall of the palace under Nusbaum’s restored doorway. In front of them are neatly displayed handmade jewelry, pottery, and other works of art on fabric spread on the ground. Tourists can walk towards the doorway to peruse these artists and their work (Abel, 2013). Art and cultural museums provide the means for preserving history, sustaining culture, and creating identity. Museums enable people to understand each other’s cultures and strengthen democracy and build communities (Zeuli et al., 2021).

This study investigates the relationship between the Santa Fe style in NM in the United States of America (USA) and the Najd style in Ad-Dir’iyah in the KSA in building design or architectural heritage. This study also provides a geographical and historical introduction to Saudi Arabia and NM and reviews certain traditional buildings. Thus, this study analyzes the similarities (colors and materials) and differences (doors, windows, and roof systems) between the architectural heritage of both the Najd style in the KSA and the Santa Fe style in the USA. Specifically, the study focuses on the effectiveness of integrating woven beading textiles to create contemporary artworks inspired by American and Saudi architectural heritages. The study explains how teachers can use place-based learning (PBL) to develop a curriculum in art and design for pedagogical purposes. The researcher designed and applied six innovative designs by creating art projects through experimental learning.

2 Literature Review

2.1 Heritage

Many experts have studied the significance of heritage and have emphasized the crucial role governments play in achieving developmental goals. According to Kirshenblatt (1998), heritage is a new mode of cultural development in the present that has recourse to the past. Aljahani (2019) argued that every society knows its identity, distinguishing it from other cultures. Heritage relates to a community’s position in the world and its relations with other communities based on its own identity, formed by cultural factors and developed and accumulated over history; cultural heritage is both moral and material. Material culture includes handicrafts and the traditional tangible manufacturing of industrial products made from natural raw materials such as clay, wood, leather, fiber, and metal. Traditional culture is considered a crucial material culture in a society (Yang et al., 2018). Material culture is also the transformation of raw material into a specific form that serves a purpose for society, such as folk arts, crafts, buildings, clothing, and food (Al-Bassam, 1985). Moreover, creative place-making refers to a successful path from economic development, such as reusing vacant spaces, to generating income and jobs. Thus, it produces livability outcomes such as public safety, community identity, and environmental quality.

2.2 Ad-Dir’iyah as an Example of the Saudi Najd Style of Architecture Heritage

The KSA is located in the Middle East (Ahmed et al., 2022), and the Saudi architectural heritage belongs to five regions, namely, central, western, northern, southern, and eastern. Each region has its own unique urban style in addition to the typical Islamic style (Ghazala, 2021). This study considered the central regions of the KSA, including the Najd style of Riyadh, the capital of the KSA (Ahmed et al., 2022). Ad-Dir’iyah is located to the northwest of Riyadh, where the ruling House of Saud developed the citadel of At-Turaif as their political, social, cultural, economic, and religious center (Aljahani, 2019). Here the traditional buildings vary according to the geographical and climatic environment. This region presents flat and mountainous areas, as well as desert and coastal environments.

Central Saudi Arabia has a distinct heritage architecture, including several aesthetic characteristics. Thus, this region is a fertile resource for inspiration in the art of painting (Almogren, 2020). Its architectural heritage has standard features reflecting Islamic culture. The characteristics include fabric, design, shape, materials, layout, surroundings, and both external and internal features, which express the ideas and feelings of Saudi artists whose values are rooted in the social and cultural environment (Alzahrani, 2022). The artistic traditions of Islam are noticeable in a rich system of ornamentation applied to art and architecture. Islamic ornamentation includes three predominant decoration types: calligraphy, vegetal motifs, and geometric patterns. Figurative forms of humans and animals are not typical due to the Qur’anic commandment against idolatry. Instead, abstract decoration shapes are used to create visual statements about religious ideas and to express the logic of the Islamic vision of the universe (Jowers et al., 2010).

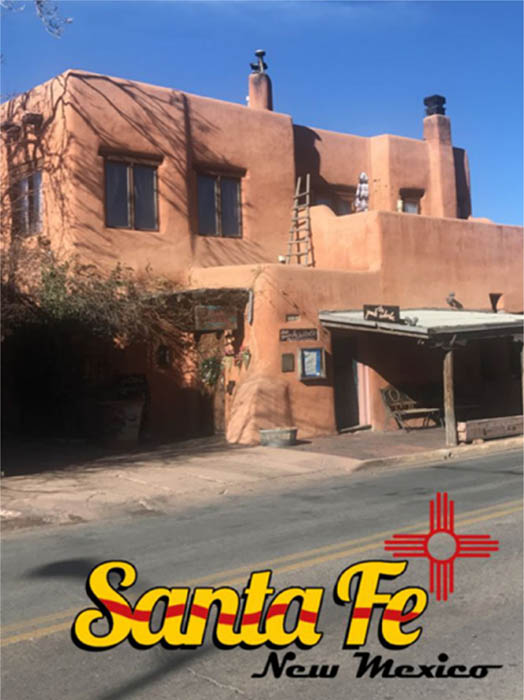

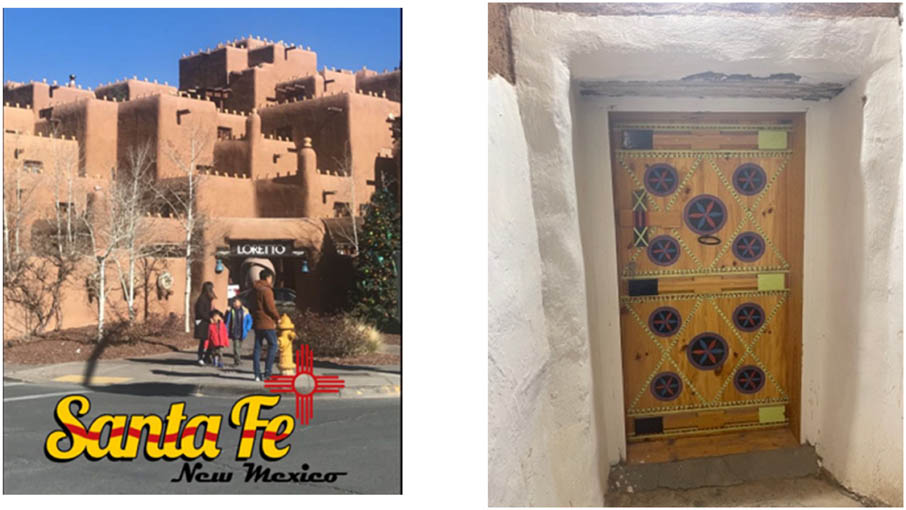

2.3 Santa Fe as an Example of the Multicultural Style of Architecture Heritage

NM is the southwestern and fifth largest state in the USA (Zumlot et al., 2009), and its capital, Santa Fe, is a city of culture, arts, crafts, and architecture with a rich history. This state is characterized by old adobe structures and ancient landscapes (Dye, 2007). Its unique artworks can be seen throughout the city, both in indoor galleries and historic architectural buildings and through performances that celebrate its heritage (Lovato, 2004). Santa Fe’s rich artistic heritage stems from the American Indian architecture and construction that followed the zoning for buildings in the Spanish Pueblo style (Mathis, 1999). According to William (2013), the heritage areas commemorate the 400-year “coexistence” of Spanish and Indian peoples in this region and honor NM’s position within the United States.

The Palace of the Governors is an adobe building on the north side of the Santa Fe Plaza. Constructed around 1610, the Palace served as the administrative center of NM for 300 years. Spaniards, Mexicans, Americans, and Pueblo Indians all occupied the palace at different times, asserting their authority over the region and its diverse population. In 1909, the territorial legislature converted the building into a museum of history and anthropology, and since then, it has become Santa Fe’s best-developed historic site. In particular, the Palace of the Governors embodies the complex relationship between colonialism, multiculturalism, and heritage preservation in NM. Heritage tourism is one of the most common ways to integrate conservation and development, attracting more tourists to areas such as the Northern Rio Grande National Heritage Area (Thomas, 2013). According to Guthrie (2013), the Palace of the Governors, a one-story adobe building on the northern side of the Santa Fe Plaza, has always been Santa Fe’s most famous landmark. Its front facade has become a tourist icon: under the front portal of the Palace, Indian artists display handcrafted jewelry, pottery, and other goods. As tourists walk past, they admire the artwork and enjoy a quintessential New Mexican cultural experience.

2.4 Textile – Weaving Beads

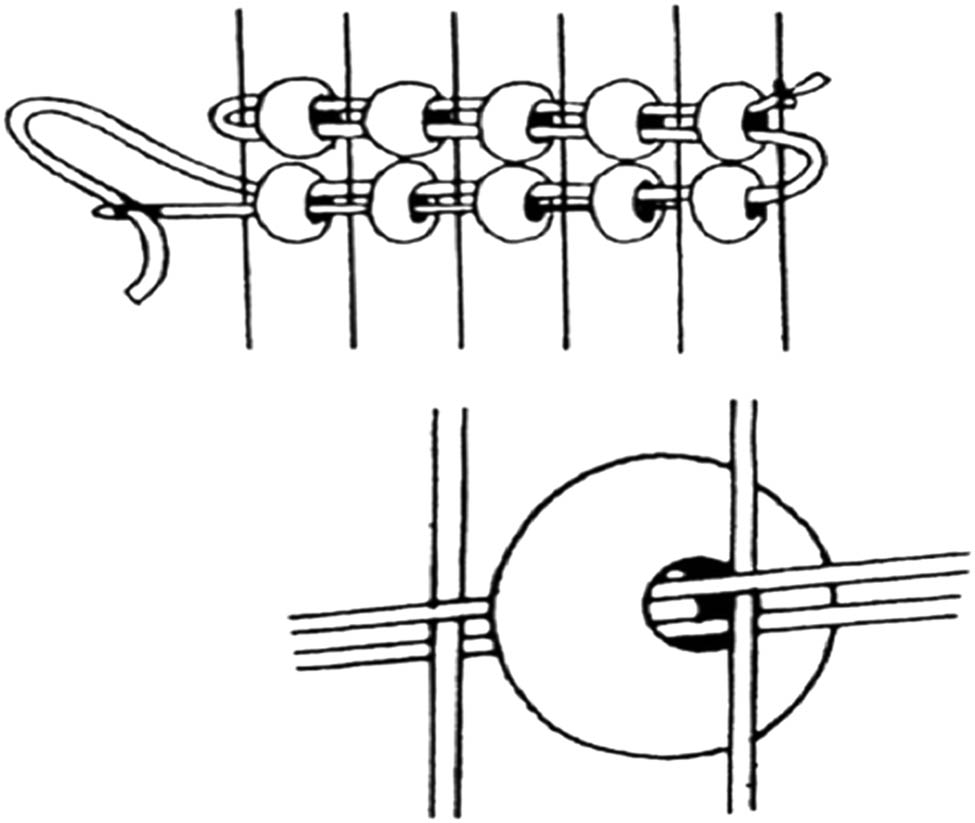

For centuries, human beings have created and embellished textiles to communicate individual and social identity, spiritual beliefs, and aesthetic ideals (Leslie, 2007). Many different processes transform yarn into fabrics or textiles. Among these processes, weaving is the most common method. There are three basic weave types: plain, twill, and satin. All other weaves are modifications or combinations of these patterns (Marshall, 2000). Weaving beads creates a type of textile by using weaving and beading techniques. Weaving beads is crucial to human expertise, particularly for women who enjoy handcrafts (Leslie, 2007). This technique is the predominant textile design type in the Arabian Peninsula. The Bedouins of Saudi Arabia are the simplest and most frequently used plain weave type. Weaving uses looms and soft wool yarn (Ross, 1994). According to Leslie (2007), bead weaving is defined as making or embellishing textiles and creating new fabric using a needle and fiber, thread, or yarn. In other words, bead weaving is a plain weave textile that uses the same weaving process as a loom but uses thread, needle, and beads instead. Figure 1 illustrates that each warp yarn passes alternately over one and then under one filling yarn for the entire length of the fabric. Two adjacent warp yarns interlace with each other. One warp yarn goes under the same filling yarn as the first and second. It requires two harnesses to weave a fabric body because the weave repeats every two ends (Johnson et al. 2015). This study focuses on basic weaving, which uses plain-weave beads to create artwork.

Plain-weave beads.

3 Theoretical Framework

3.1 PBL

PBL refers to an approach to pedagogy (Elfer, 2011). Khamouja et al. (2023) defined PBL as a form of modern pedagogy that involves students discovering knowledge and the location of teaching is intentional, local, or relevant to the topic. According to Zeuli et al. (2021), “knowing” a place implies expressing sensitivity to its complexity and being aware of the differences and similarities between that place and other places. A learning environment is a place that has several dimensions, such as geographical, ecological, cultural, and political characteristics, with a context for multidisciplinary learning and leveraging students’ sense of place; thus, the students become more engaged and their learning more meaningful (Ladachart et al., 2020; Zeuli et al., 2021; Khamouja et al., 2023). Zeuli et al. (2021) argued that these elements are present in one of the leading frameworks of PBL, which proposes four dimensions, namely, the biophysical, psychological, socio-cultural, and political-economic. The PBL can lead to more suitable lifestyles and economies to the ecological and cultural attributes of a place (Semken, 2005).

This study investigates the relationship between the architectural heritage of the KSA and that of the USA. The researcher analyzes the similarities between Santa Fe in NM, USA, and Ad-Dir’iyah in Riyadh, KSA, to observe, analyze, design, and apply bead weaving to textiles to develop a range of modern designs and artworks inspired by the architectural heritage of the two countries. The author selected textile bead weaving because both cultures use this technique. Previous studies provided the researcher with the continuous linking heritage and the PBL in art teaching and learning to help teachers upgrade teaching standards and designing to inspire heritage through artifact analysis and get unique artwork outcomes and how these architectural heritage styles have been used in educational settings or as artistic inspiration within practice-based studies. The experience of learning influenced the current study, and the researcher used her design skills to transfer her knowledge and experiences to the art and design curriculum.

4 Methodology

The current study is a qualitative methodology incorporating an experiential approach based on a field study. The filed study is a way of learning that take place outside the classroom. It involves researcher going to different locations and conducting research to gain practical knowledge about the architectural heritage between Santa Fe in NM, USA, and Ad-Dir’iyah in Riyadh, KSA. The research design is a case study through PBL, which the researcher implemented using an experiential approach. This study presents the suitability of two case studies, which is a qualitative research method and can be used in teaching art and design. The methodology engages the researcher in the lives and experiences of those being studied and explores the social, psychological, and emotional implications of these experiences. Field study integrated with experiential, a descriptive-analytical method, was used to study the American and Saudi heritage in two areas, namely, (1) the historic downtown Santa Fe Plaza and (2) Ad-Dir’iyah, in Riyadh, the KSA. The research mainly focused on the following points:

The relationship between the Saudi and NM architectural heritages.

Effective implementation of innovative artistic designs from Saudi and NM architectural heritage sources in textiles.

4.1 The Purposeful Sample

The purposeful sample was focused on the historic downtown Santa Fe Plaza in NM and Ad-Dir’iyah in Riyadh city in the KSA. Although they represent different heritages, the research found similarities between the two countries. The study focused on traditional architecture, specifically ten buildings in the KSA and NM, respectively. The researcher then analyzed the similarities (motif units, colors, and materials) and differences (doors, windows, and roof systems) between the architectural heritage. In this research, inspiration from architectural heritage for textile bead weaving is drawn to create contemporary artworks inspired by American and Saudi heritage buildings.

5 Data Collection and Analysis

The research used a qualitative case study method with experiential approach. Moreover, the data collection included observation as field study and analysis of the documents and artifacts.

5.1 Observation

Observation is the act of noting a phenomenon in the art and design field. A researcher observed using all senses, which are sight, hearing, touch, smell, and taste. Creswell (2009) states that the researcher can obtain more information from observation than discussion or written documents. The observer can note the physical setting, participants, activities, interactions, and conversations. Then, the researcher analyzed observations documented in field notes by saving the observation protocol on Google Docs files. During the observation process, the researcher toured art museums, took photographs of various buildings, examined the architectural heritage, and experienced the local culture. The observations were based on the author’s own experience living in NM from 2014 to 2018. The researcher felt at home when she arrived in NM to pursue her Ph.D. in Las Cruces, NM, USA, including buildings, artworks, people, weather, and the desert. However, the researcher wanted to explore the emotional implications of such experiences. Over the course of four years, she observed the similarities in art heritage between NM and that of her home country, KSA. She lived in Las Cruces but also visited several other cities, such as Santa Fe, Albuquerque, Ruidoso, and Truth or Consequences.

5.2 Documents and Artifacts

The documents and artifacts are other primary sources of the qualitative data. The documents cover an assortment of written records, visual data, artifacts, and even archival data. The data from documents and artifacts include visual documents such as letters, videos, drawings, web-based media, and photography.

5.3 Camera

Captured high-quality photographs of the buildings and architectural heritage details to document the observations serve as visual reference for creating the artworks.

5.4 Drawing Tools

The researcher used drawing tools, such as sketchbook, pencils, ruler, color pencils, and tracing, for creating artworks and then translated the design to technology program. .

5.5 Textile Tools

In the current study, the textile tools included loom beads, different colors of beads (2 mm), cotton thread, and big eye beading needles.

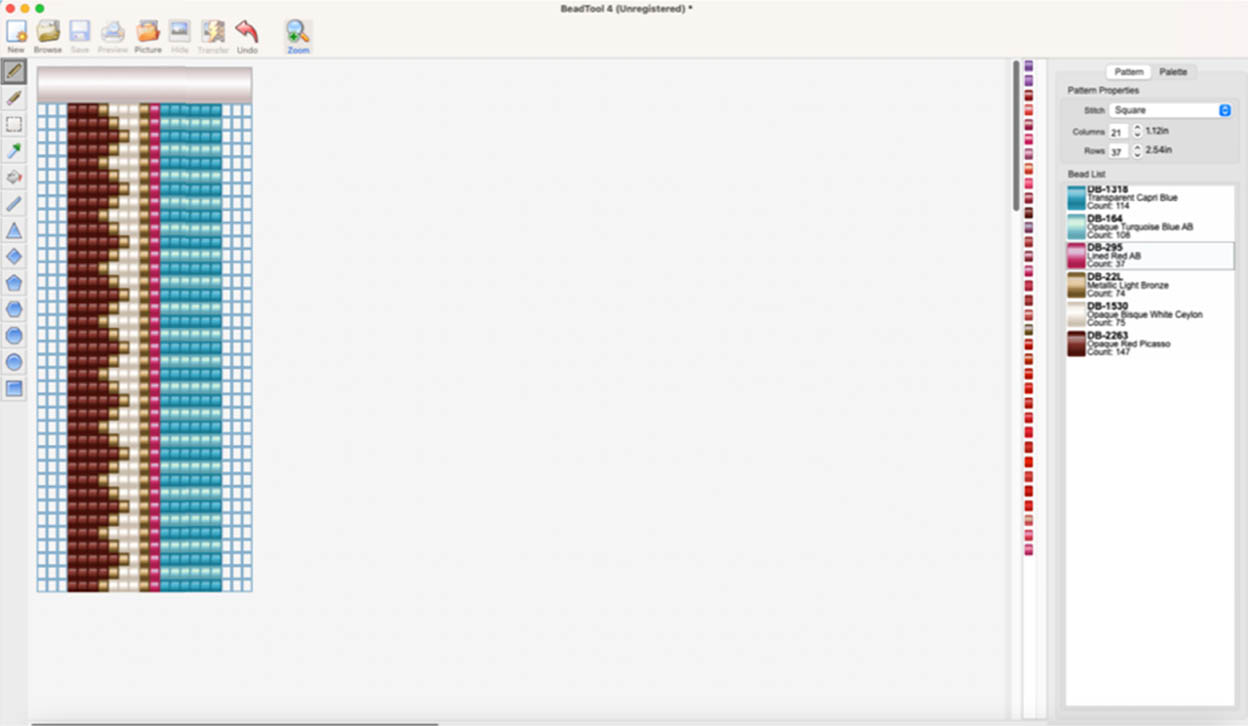

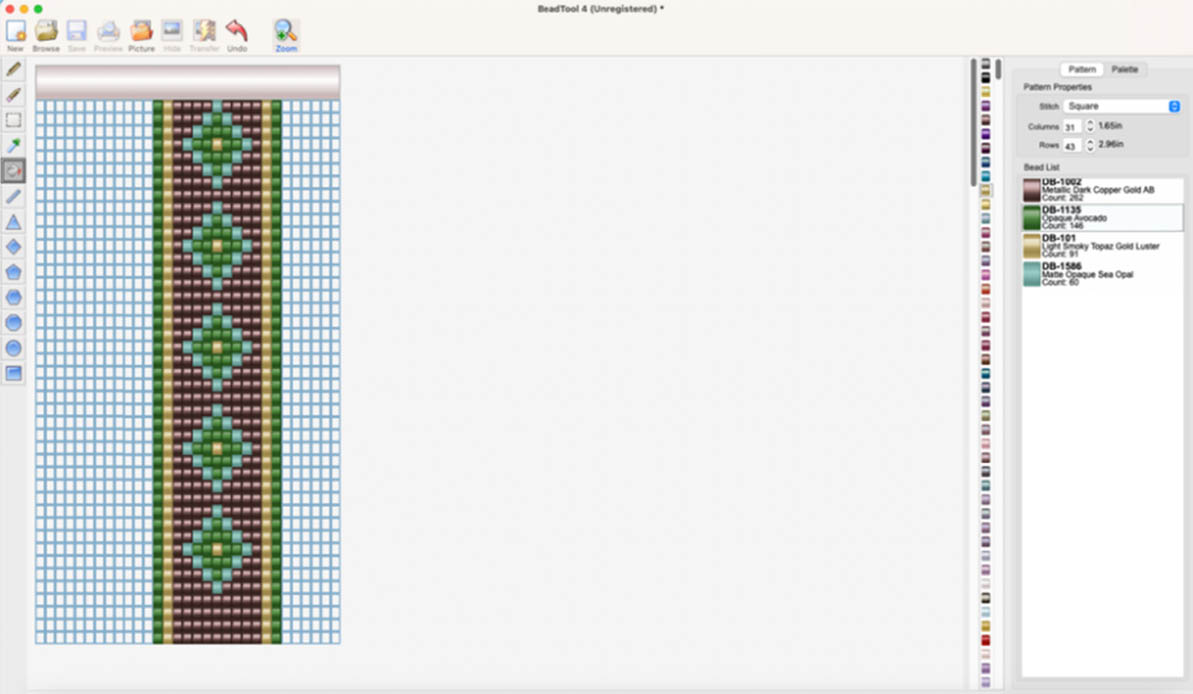

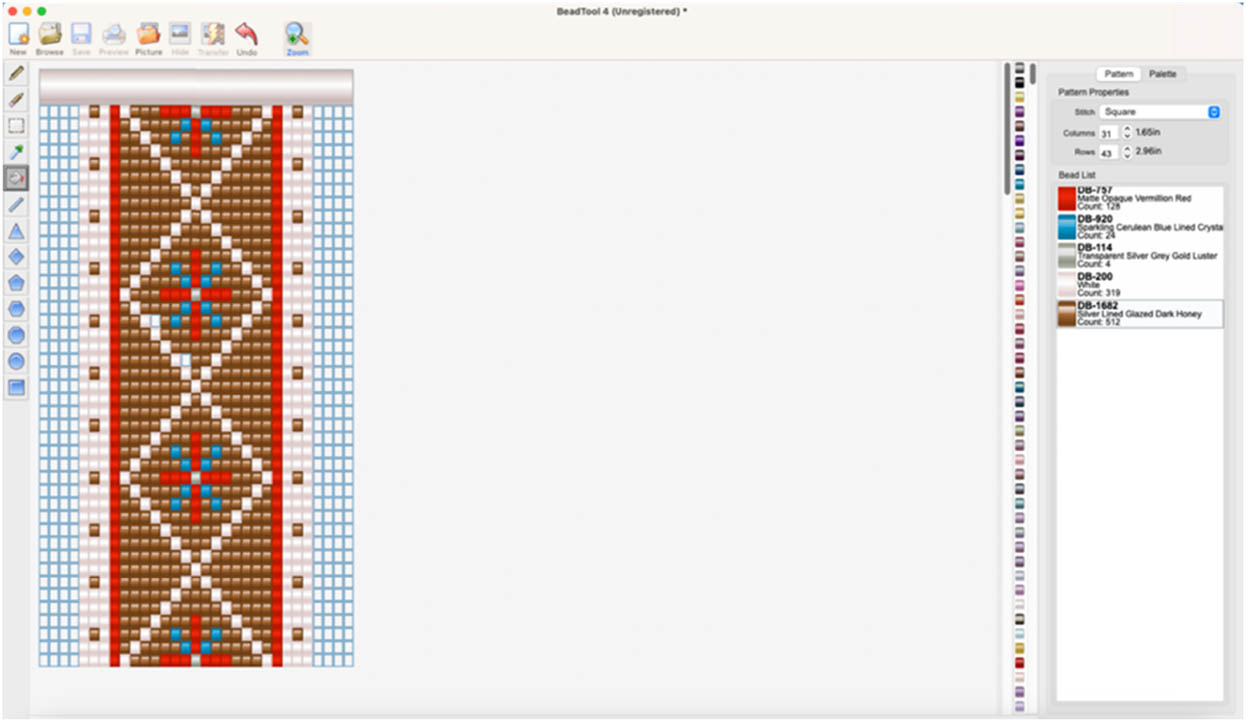

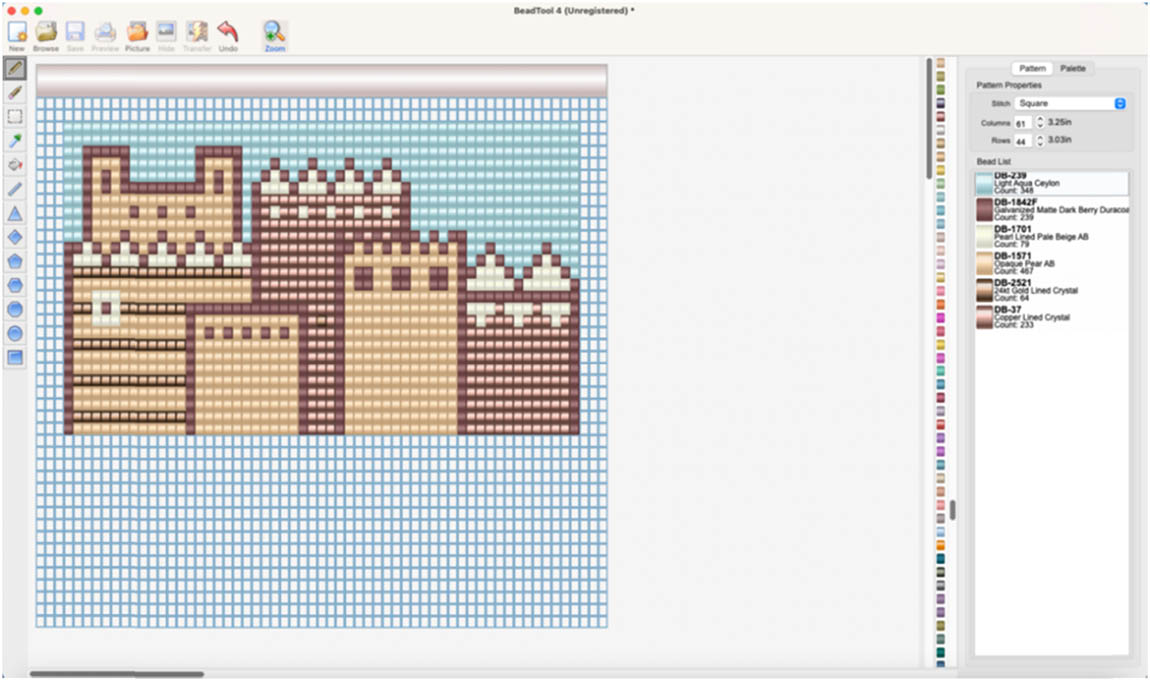

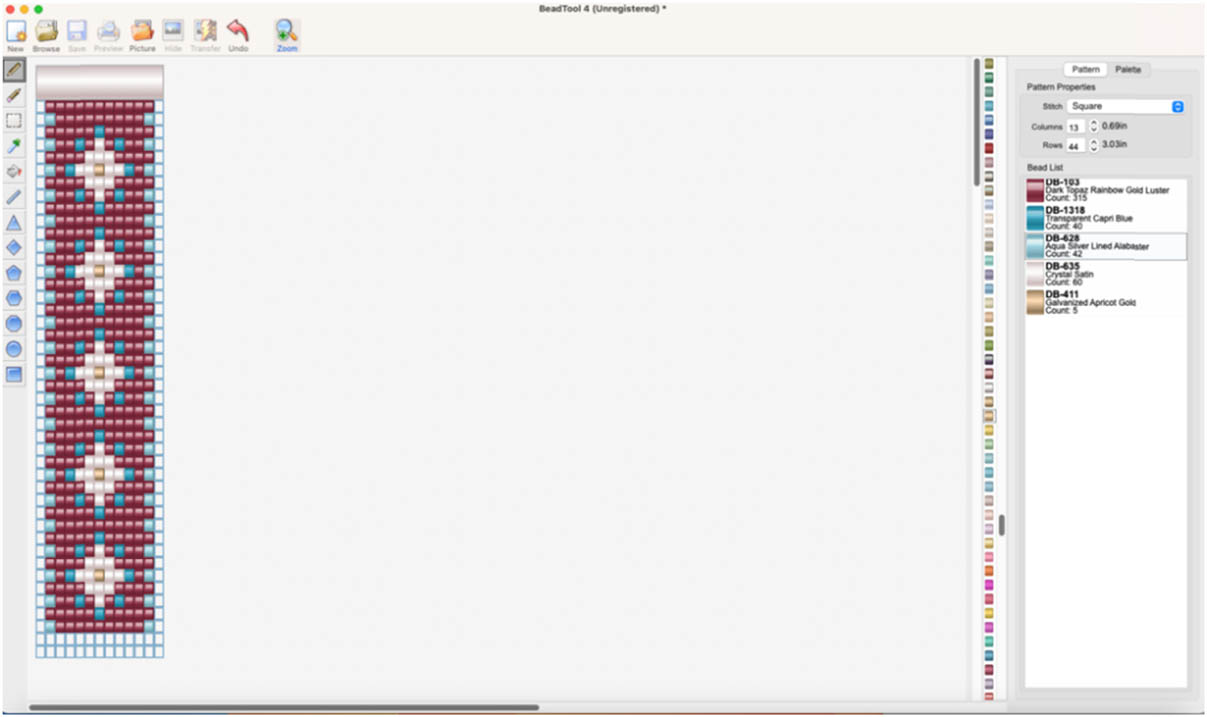

5.6 The Bead Tool 4 Software

The designs from sketches were transferred to a technology tool, the Bead Tool 4 software, which can be found at https://www.beadtool.net/. The researcher used the tools to create six designs of different beading textile artworks inspired by architectural buildings from NM and the KSA. This tool was helpful and easy to use to design bead weaving textiles. It has drawing tools and a main tool bar which are easy to use, just like any drawing program. The researcher enjoyed using patterns and the software palette tools. It was also easy to use the patterns and solve problems when mistakes had been made in the paper sketches. Although the researcher has different design patterns and projects, the tool allowed her to create different sizes of each design pattern, depending on her projects. The palettes included different shapes and types of beads. The palettes have lists of beads of different colors and tones, organized by DB numbers or the name of the colors. However, the Bead Tool 4 software was only useful for computers. Finally, the researcher applied the final state for the desired image of the artwork from heritage sources, in which the artwork reaches its climax so that it combines originality and contemporary.

5.7 Filed Note

The researcher was keeping a note of details during observations, documenting important information about the buildings on Google Docs files. Documenting work online is an effective strategy for success. The first resource to help students be successful is Google Docs and Google Drive.

6 Thematic Data Analysis

The focus of this section is the thematic analysis of the data produced in this qualitative case study. The researcher uploaded observations filed note into the NVIVO software program in order to prepare for coding and analyzing the data. Then, she used coding to group the data using the research questions, and looked for (1) common themes similarities in instructions, materials, and colors of the architectural heritage between the Santa Fe and Saudi Najd styles and (2) differences between the architectural heritage doors, windows, and roof system. Finally, the researcher coded the data twice from different sources to report the findings.

7 Limitation

The limitations of this research study are as follows: (1) The time limit was a period of 5 years from the beginning of the research project, observing the buildings in both countries, analyzing the designs, and using an experiential approach and (2) the geographical boundaries limited the geographical area to the western region in the KSA (Najd) and NM in the southwestern region of the USA.

8 Results and Discussion

The result presented three themes: (1) similarities in instructions, materials, and colors of the architectural heritage between the Santa Fe and Saudi Najd styles, (2) differences between the architectural heritage doors, windows, and roof system, and (3) drawing inspiration from architectural heritage for textile bead weaving designs. The first and second themes answer the “relationship between the Saudi and New Mexico architectural heritages.”

The comparisons between the Santa Fe and the Saudi Najd styles are particularly significant because of the traditional and unique cultural manifestations, along with the diverse geography and climatic regions. The researcher identified different themes by investigating both places and analyzed the relations between the traditional architectural and artistic expressions of the Santa Fe and Saudi Najd styles.

The researcher used PBL as a form of modern pedagogy, which involved her discovering knowledge of both the Saudi and NM architectural heritages. The sense of place is the human relationship to the place, including many diverse forms of place meanings such as aesthetic, economic, familial, cultural, historical, political, or scientific significance. The researcher also forms personal, emotional, and affirmative attachments to NM and KSA places that are meaningful to her. According to Semken et al. (2017), the nature of place and the human relationship to place are particularly well characterized in the PBL theory and practice within geography and environmental psychology. This study is relevant and applicable to PBL. Hence, a place is any locality that becomes imbued with meaning through human experience. During the PBL, the researcher had the opportunity to explore the architectural heritage between the two countries. The current study provides a review and analysis of the assessment of the PBL in Arts, beginning with the assessment of the sense of place, a primary learning outcome of the PBL across arts and design. This is followed by an analysis of cognitive, affective, and behavioral learning outcomes related to the PBL, drawing inspiration from architectural heritage for textile bead weaving designs. Art is a powerful tool for learning because nature-infused learning experiences evoke powerful emotions (Gray & Thomson, 2016). Thus, art activities can connect researchers to the architectural heritage through PBL to support research, asserting that the art leverages deep engagement and links with the heritage. Applying PBL resulted in six innovative designs by creating different art projects through experimental learning. By engaging in experiential learning, individuals are given the unique opportunity to continually expand their understanding and abilities in practical contexts.

Allen et al. (2019) identified a four-step, interrelated cycle of learning. Beginning with the Concrete Experience phase, learners engage in firsthand interactions with situations, issues, or tasks to acquire knowledge (Lavoie et al., 2018; Murgu et al., 2018). Murgu et al. argued that the second phase, the Reflective Observation stage, examines the experience and evaluates the outcome. In the next stage, Abstract Conceptualization, learners connect previous knowledge to their experience (Morris, 2020). Finally, the Active Experimentation phase encourages practical application, allowing individuals to experiment with various approaches and solutions (Govindasamy et al., 2023).

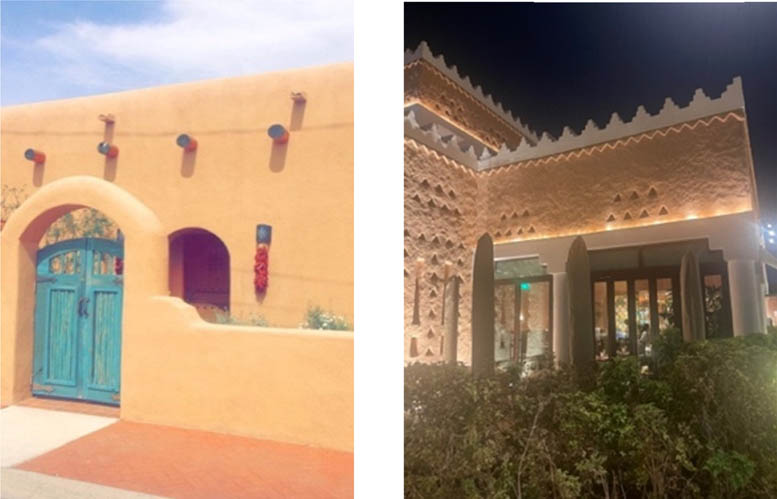

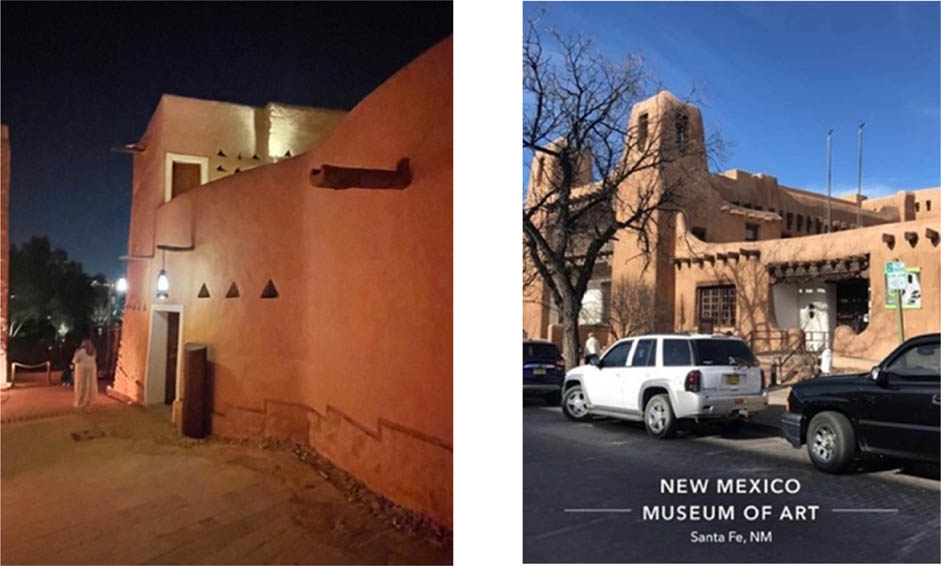

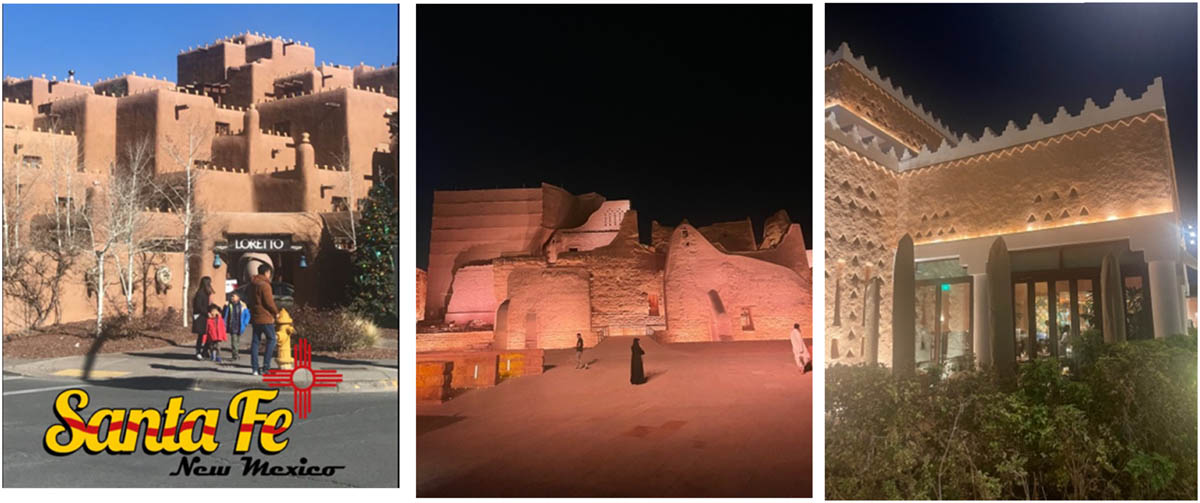

8.1 Theme 1: Similarities in Materials and Colors of the Architectural Heritage Between Santa Fe and Saudi Najd Styles

The result considered two American and Saudi heritage areas, namely, (1) the historic downtown Santa Fe Plaza and (2) Ad-Dir’iyah, in Riyadh, the KSA. Although they represent different heritages, the research found similarities between the two countries. The architectural constructions in both countries were the color of the earth and were made from clay soil. The shapes of the buildings made from the soil became an integral part of the environment (Moscatelli, 2023). In Saudi Arabia, the researcher studied the Najd style of buildings, which considered various geometric configurations, usually square or rectangular. In the USA, the researcher studied the Santa Fe style of buildings.

The researcher identified three main similarities between NM and the KSA in terms of buildings, materials, and colors representing architectural heritage, which are explained in detail below. Table 1 shows the similarities in construction and traditional architecture in both cities. Further, the construction materials are made from natural raw materials such as clay, wood, leather, fiber, and metal. The sand color of the main building as well as walls in the Santa Fe Pueblo style is similar to the Saudi Najd style. Maruyama et al. (2008) state that, in Santa Fe, people draw attention to the building’s material features (made of adobe, wood, glass, and plaster) and suggest that these are historic and old. The Saudi buildings were constructed with similar materials such as stones, different varieties of trees suitable for construction, and mud or sundried bricks and finished with a mud plaster application. Other materials are metal, glass, or textiles (Mazzetto & Vanini, 2023). Adobe is Santa Fe’s classic exterior material. It is claimed that “adobe was the primary building material used in the early days of Santa Fe’s settlement” (Wilson, 1981).

Traditional Architecture in Santa Fe and Ad-Dir’iyah

| The historic downtown Santa Fe Plaza, Pueblo style, NM, USA | Ad-Dir’iyah, Najd style in Riyadh, the KSA |

|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Adobe, a mixture of sun-dried soil and straw, provided excellent insulation and temperature regulation in the region. The warm reds and deep browns of adobe add to Santa Fe’s architectural flair. Many Santa Fe heritage structures feature functional and sociable inner courtyards. According to “Santa Fe Art and Architecture,” these courtyards “provided a cool, shaded area for outdoor living and were often adorned with fountains, gardens, and other decorative elements” (Bleiler & Strong, 2012). Courtyards gave reprieve from the hot, arid environment while also fostering community and a connection with nature. Although Santa Fe’s history buildings are basic and functional, they often feature subtle architectural embellishments that add visual appeal and cultural significance. Wilson (1981), e.g., states that “carved wooden lintels, corbels, and other decorative elements were common features of Spanish colonial architecture in Santa Fe.” These Spanish and Pueblo-inspired ornamental embellishments reflected artistry and cultural identity, contributing to the city’s architectural heritage.

8.2 Theme 2: Differences between the Architectural Heritage Doors, Windows, and Roofing

The authenticity of the heritage buildings in Ad-Dir’iyah lies in the keen integration of features that meet the needs of the people while enhancing the adaptability of these buildings to the intense heat and sun in Saudi Arabia. These heritage buildings have diverse Najd motifs, facades, doors, windows, and walls that exemplify the practicality and sustainability of the extreme desert climate (Almogren, 2020). The buildings have a distinct façade design made of mud and brick to provide shade for the local communities from the extreme heat of the sun (Rahmayati & AlGhunaim, 2024). The buildings have rammed-earth thick walls and small exteriors to protect them from extreme temperatures and wind (Moscatelli, 2023). Similarly, the heritage buildings are designed using crafts and materials that create a visual appeal that aligns with the geometric forms and the cultural identity of the locals. The orientation of the buildings further contributes to the well-being of the residents. They have shaded outdoor zones that enhance the efficiency and performance of the buildings during cultural and recreational events (Bay et al., 2022). These spaces have vegetation, water, and endemic plants to enhance biodiversity, efficient and natural lighting, and thermal comfort. Such designs propagate the traditional Saudi traditions for future generations to appreciate the value from the heritage designs. Nadji culture, predominantly in Ad-Dir’iyah, is the cornerstone of Saudi heritage. It weaves all the rich cultural, climatic, and historic fabric of the country. For decades, the buildings in Ad-Dir’iyah have been preserved to protect cultural values and create fresh perspectives that resonate with the locals and global audience (Almogren, 2020). The vernacular architectural designs of preserved heritage buildings in Ad-Dir’iyah have created a timeless cultural symbol that engages the geographical and cultural aspects of Najd culture. The woven and well-integrated features of the heritage buildings show that they appreciate and respect the Najd culture.

In other words, Santa Fe history buildings are usually one to two stories tall. Its traditional architecture and adobe construction influence the region’s low-rise design. According to Bleiler and Strong (2012), the modest heights “allow the buildings to blend seamlessly with the surrounding landscape and create a sense of visual cohesion” in Santa Fe’s historic districts. As Santa Fe strives to conserve its architectural legacy, heritage building protection varies. In the words of Wilson, “Some structures have been meticulously restored, while others show the natural wear and tear of time” (1981). Buildings can be conserved or restored based on historical significance, structural soundness, and resources. Heritage structures, regardless of protection status, symbolize Santa Fe’s rich cultural history and contribute to its character.

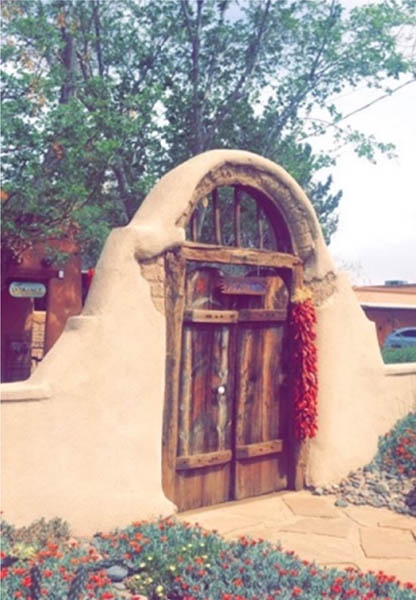

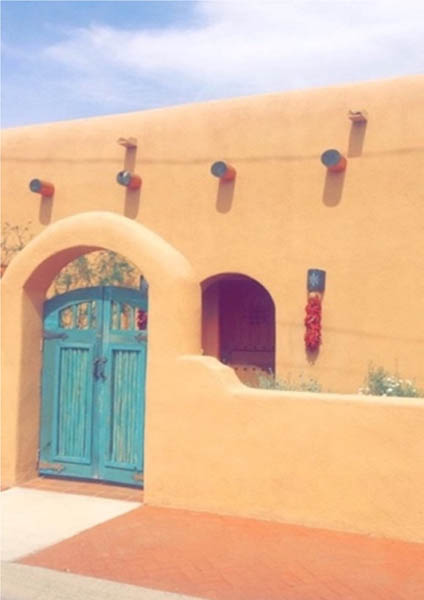

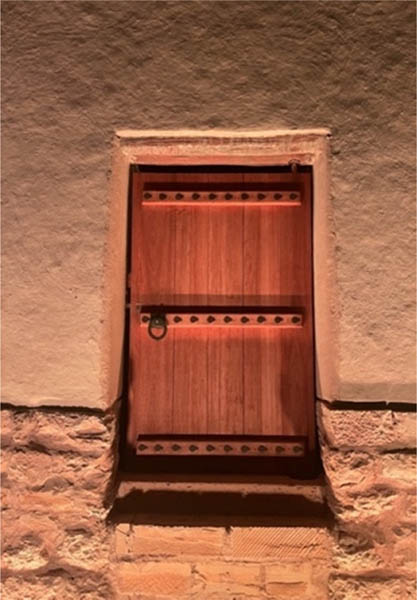

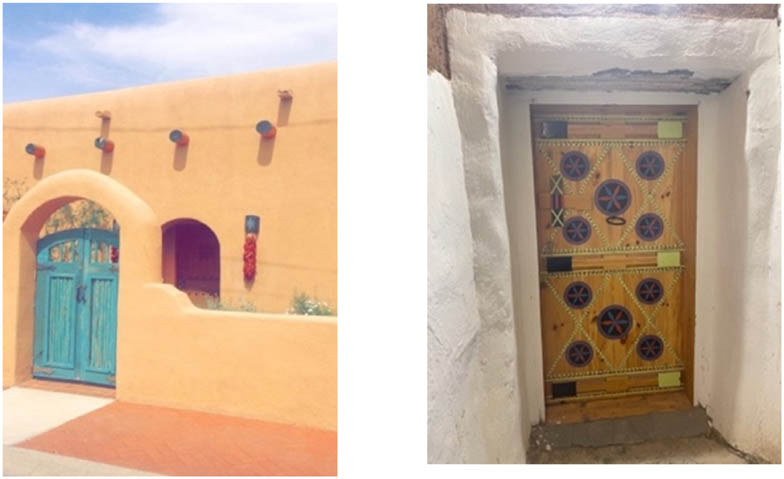

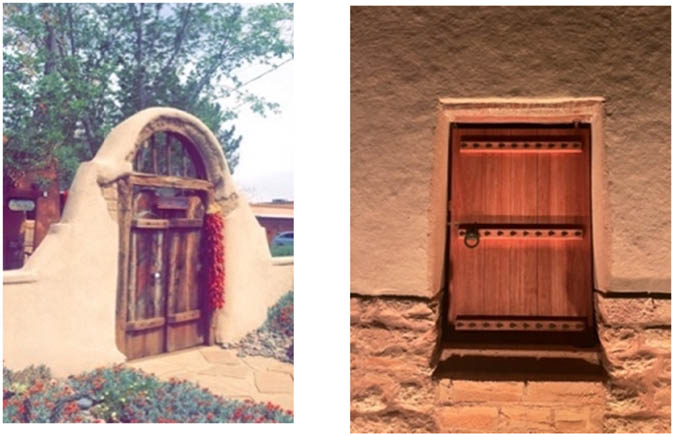

8.2.1 Doors

Even though the doors in both cities were made from woody natural materials, the colors of the doors differed. As shown in Table 2, the Santa Fe style used one simple color, such as blue or natural wood, but the Saudi Najd style used a rich variety of colors and motifs. The wooden doors in the Saudi heritage architecture use overlapping, opposite, symmetrically decorative, and geometric shapes. The decorations on those doors depend, to a large extent, on the geometric and plant motifs, such as triangles, circles, squares, intersecting lines, and the simulation of roses, leaves, palm fronds, and bunches of grapes. The colors used are bright, such as yellow, blue, red, green, and black (Ben Ali Alsoliman, 2019). Table 2 shows the differences in the architectural doors of heritage buildings in both cities. A study identified four main traditional construction materials used in architectural heritage buildings. Sanchez-Calvillo et al. (2023) explained that traditional construction materials for architectural heritage buildings were natural soils, stones, wood, and lime, locally available throughout the country. Moscatelli (2023) explained it as follows:

Differences between the architectural heritage doors

| Santa Fe Pueblo style | Saudi Najd style |

|---|---|

|

|

|

|

“The traditional Najd doors function as an access element to the building and are unique in their design. They are usually square in size, single-sided, made of wood or palm trees. Some entrance doors are colored, engraved, and painted with geometric motifs, embellished with repetitive designs of a symbolic nature, and very pleasant in style and composition” (p. 8).

There are three architectural heritage ornamentations in terms of art and design, namely, Islamic geometric patterns based on the principles of symmetry, repetition, and balance. The patterns comprise simple polygons such as squares, triangles, and stars. Doors are also decorated with motifs such as flowers, roses, plants, or leaves. The unique design of doors in heritage buildings expresses specific elements and principles of architectural design.

8.2.2 Windows

The windows of historic Santa Fe buildings reflect both the climate and the region’s energy efficiency. Bleiler and Strong (2012) stated that “the windows are typically small and deeply recessed, providing natural lighting while minimizing heat gain.” This design element enhances the depth and character of building facades while serving a useful purpose. However, the windows of Najd buildings have Furjat, small openings in the walls. The Najd architectural style has walls often pierced with small rectangular or triangular openings to promote adequate air movement and lighting to the interior spaces and the view from inside to outside (Moscatelli, 2023).

8.2.3 Roofing System

Heritage structures in Santa Fe have distinct roofing styles that are appropriate for the environment. The most frequent flat roofs are “parapet roofs,” “featuring a low wall around the perimeter to protect against harsh weather conditions.” These roofs feature canales (scuppers) and vigas that “extend beyond the walls to allow rainwater to drain away from the adobe structure” (Wilson, 1981). Santa Fe’s exposed wooden beam vigas contribute to its architectural legacy by serving as both structural and decorative components.

In contrast, the Najd building has Shurfat, which means the battlements at the top of the wall. The hand-molded and layered walls are tapered upwards and finished in a crenelated shape. The form of triangles or arrows, sometimes alternating between full and empty, are decorative elements that create a proportional rhythm by acting as a parapet for the rooftop (Moscatelli, 2023). To conclude, both Santa Fe’s and Ad-Dir’iyah’s heritage buildings combine culture, functionality, and aesthetics. These architectural marvels preserve its unique culture’s identity for future generations in both countries.

8.3 Theme 3: Inspiration from Architectural Heritage for Textile Bead Weaving Designs

The third theme explains the effectiveness of implementing innovative studies from Saudi and NM architectural heritage sources in textiles. Based on aesthetic perceptions, students draw ideas and designs from many sources, such as places. These places are considered as sources of inspiration and provide learners with innovative designs. Tolstoy (2023) said:

“Art is about communication, a communication of feeling, just as speech is a communication of thought. Good art is achieved when an artist feels compelled to share his emotions and succeeds in doing so, be it through writing, painting, or the composition of a piece of music” (p. 2).

Heritage architecture represents one source that can function as a reference for designers in their artworks. In this study, researchers examined the effect of PBL integrated project study on inspiration from architectural heritage. The PBL was integrated into an experiential research design to develop an art teaching and learning curriculum.

The researcher studied artworks based on architectural heritage designs using experiential learning and how the arts promote a personal relationship with the PBL. This study comprised strategies on various subjects of inspiration and how to generate ideas by observing, analyzing, and synthesizing new designs rather than imitating them. Costanza-Chock (2020) defined the design as the idea that designers sketch, draw, and mark out representations that will later become objects, buildings, or systems. A pattern is an abstract idea, and the elements repeat predictably. A geometric pattern repeats and forms geometric shapes. The researcher selected architectural heritage objects and transformed the thoughts from the units of architectural heritage into her design ideas. Costanza-Chock (2020) argued that “professional designers are inextricably connected with computers, software, and the virtual representation of objects and systems” (p. 14).

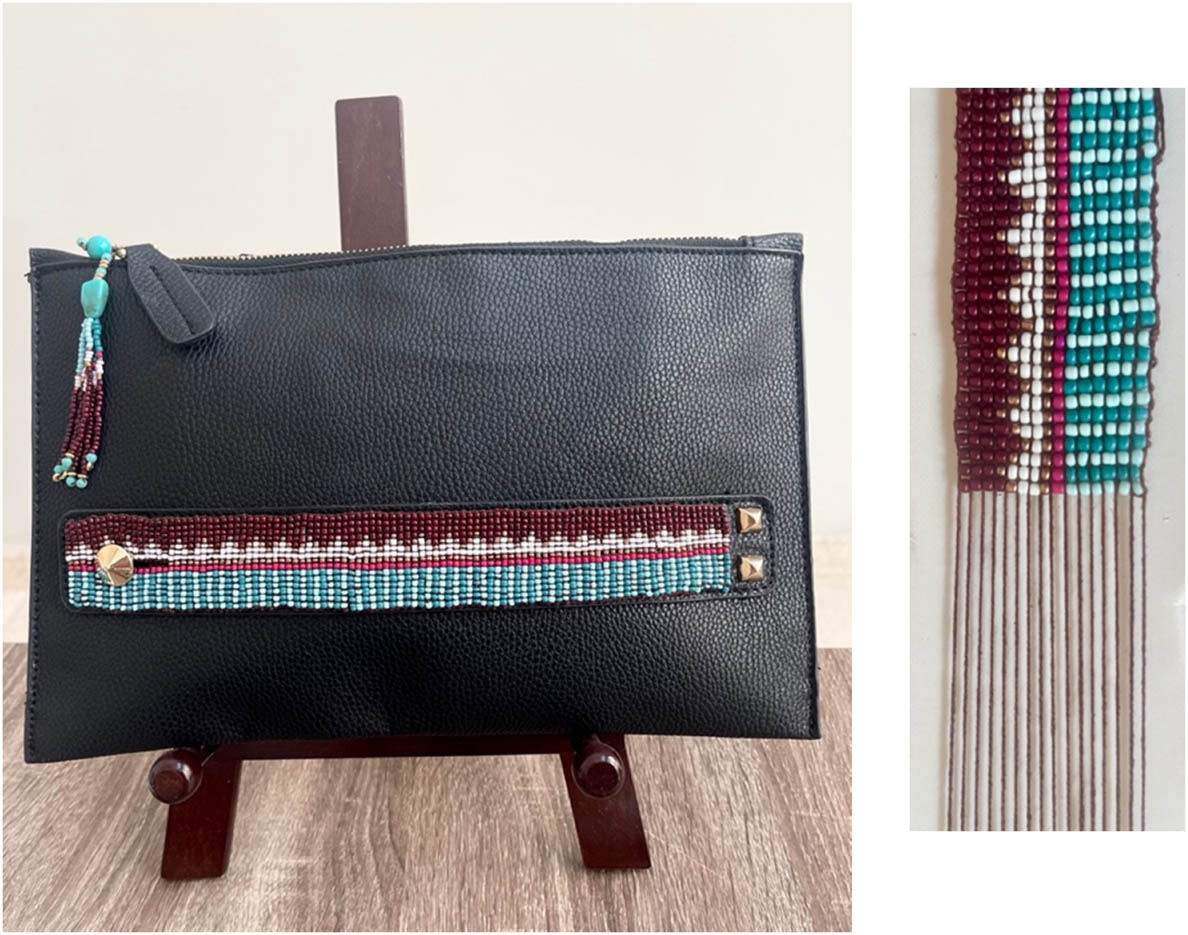

Then, the designs from sketches were transferred to a technology tool, the Bead Tool 4 software. The researcher used the tool to create six designs of different beading textile artworks inspired by architectural buildings from NM and the KSA. The six designs were a handbag, a bookmark, a mug, a T-shirt, portrait beads, and a badge card holder. The researcher prepared the materials for each project, such as the pattern, the loom, the thread, the needle, and the glass beads. Each project had a different pattern, loom, and bead color. The beads were all 2 mm in size, which depended on the design and pattern project.

8.3.1 Handbag Design

Santa Fe style. The researcher used two tones of blue colors of beads in weave textile, which was inspired by Santa Fe heritage doors, and red color, which was inspired by the decoration of red peppers in front of the Santa Fe heritage doors.

Najd style. The researcher used a triangle in the design, which was inspired by the roof of the Ad-Dir’iyah heritage building. Table 3 illustrates the handbag design process.

Handbag design

| Architecture heritage source |

|

| Design using bead software |

|

| Applying the design to the textile. |

|

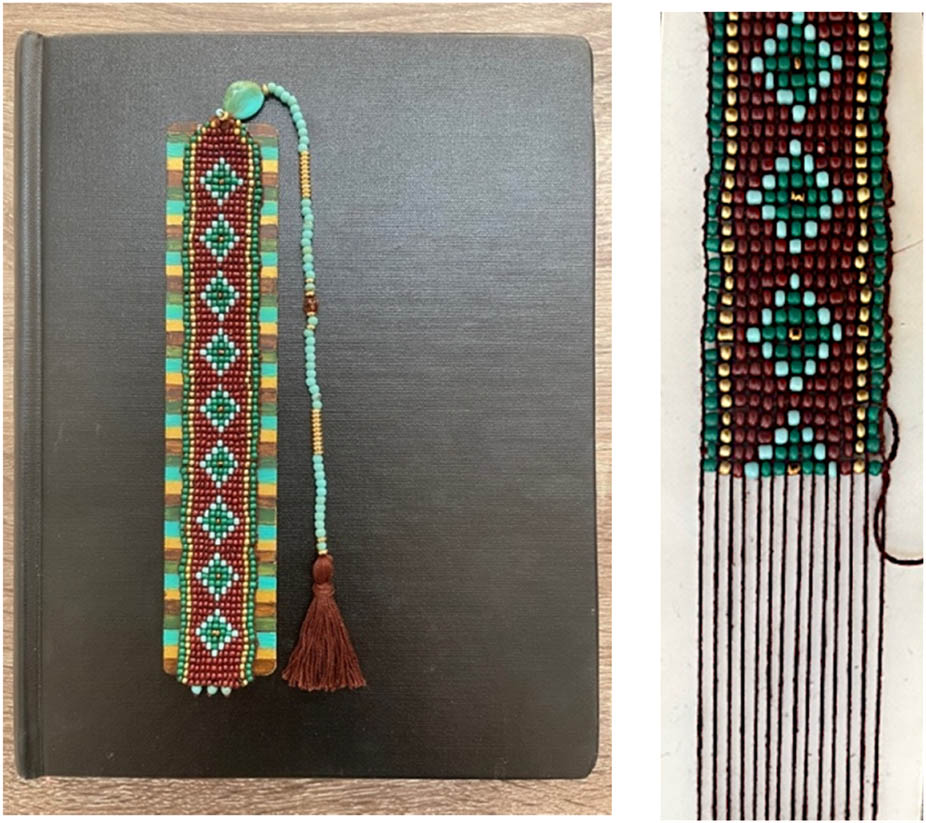

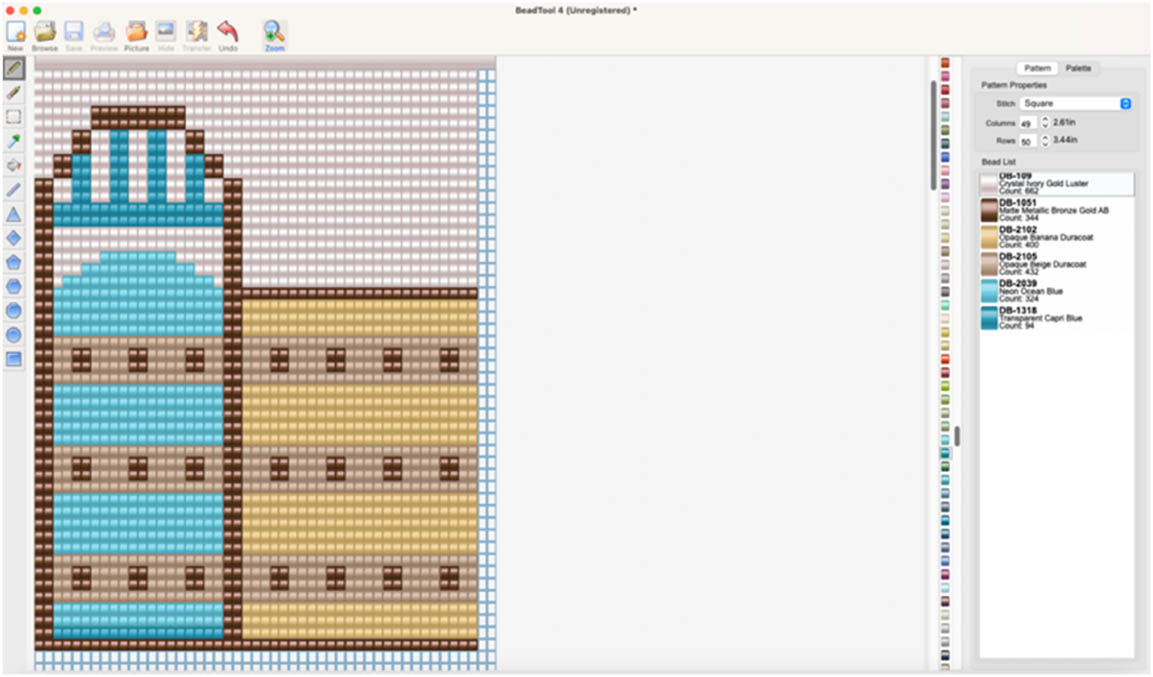

8.3.2 Bookmark Design

Santa Fe style. The researcher used dark red and sand color beads inspired by the buildings in Santa Fe heritage. She also drew lines under the weaving beads in her design, which was inspired by the window in the Santa Fe heritage building.

Najd style. The researcher used rhombus and triangle shapes, which were inspired by the Ad-Dir’iyah heritage building. Table 4 illustrates the bookmark design process.

Bookmark design

| Architecture heritage source |

|

| Design using bead software |

|

| Applying design to the textile |

|

8.3.3 Mug Design

Santa Fe style. The researcher used dots and lines on the left and right of her pattern, which were inspired by a Santa Fe heritage building.

Najd style. The researcher used rhombus and triangle shapes, and a rose was placed inside each shape, which was inspired by the Ad-Dir’iyah heritage door decoration. Table 5 illustrates the mug design process.

Mug design

| Architecture heritage source |

|

| Design using bead software |

|

| Applying design to textile |

|

8.3.4 T-shirt Design

Santa Fe style. The researcher used shapes and design features, such as dots and lines observed in the Santa Fe heritage buildings, in her pattern.

Najd style. The researcher used shapes and design features, such as dots and lines used in the Ad-Dir’iyah heritage buildings, in her pattern. Table 6 illustrates the T-shirt design process.

T-shirt design

| Architecture heritage source |

|

| Design using bead software |

|

| Applying the design to the textile |

|

8.3.5 Portrait Design

Santa Fe style. The researcher used the blue color beads in different tones and shapes from the Santa Fe heritage door designs as inspiration for her pattern.

Najd style. The researcher used a square shape with sand and brown beads in her design, which was inspired by the Ad-Dir’iyah heritage door decorations. Table 7 illustrates the portrait design process.

Portrait design

| Architecture heritage source |

|

| Design using bead software |

|

| Applying the design to the textile |

|

8.3.6 Badge card holder Design

Santa Fe style. The researcher designed dots and lines in light blue beads on the left and right of her pattern, inspired by the roof of a building in Santa Fe. She also used a square shape in her design, which was inspired by the Santa Fe heritage window.

Najd Style. The researcher designed a rose in dark blue and off-white color in the middle of her pattern, inspired by the KSA door decoration of a building. Table 8 illustrates the lanyard design process.

Badge card holder design

| Architecture heritage source |

|

| Design using bead software |

|

| Applying the design to the textile |

|

9 Reflection of the Study

9.1 Express unique ideas on Heritage by Using PBL in Arts Teaching and Learning

The process of weaving beads involves several stages that are taught and learned in art and design education. There are many different forms of folk heritage worldwide, and a teacher can allow art students to choose one type of architectural heritage to inspire their ideas. Teachers can build their curricula using PBL pedagogy, where teaching and learning are transferred from the classroom to an open place. Students learn and study about a specific place to gain knowledge and become creators. Then, they move beyond place as a simple geographical term; the concept of place includes the narratives of political and economic decisions that affect local areas and shape human life (Yemini et al., 2023).

The artist designers can see something around them that others cannot see; thus, they derive their ideas and designs from many sources such as places. Heritage architecture represents one place source that can function as a reference for designers in their artworks. In particular, there are six design stages the teacher can use to help students in the art process when drawing inspiration from the heritage and using the PBL framework: (1) Find and observe a geographical location, (2) analyze the source, (3) find objective inspiration, (4) find aesthetic imagination in form and subject, (5) synthesize new designs rather than imitate designs, and (6) apply the design.

PBL is important for the current and future practice of arts and design and is allied to sustainability heritage. When students are engaged in PBL experiences, they gained a significant role in understanding cultural identity or worldview and increased their interest in art and design.

Teacher’s role is to implement the PBL in the classroom to let students explore cultural heritage. Consequently, the students can be taught to understand and express their own emotions and empathize with others, building love and trust in the classroom (Gray & Thomson, 2016). Moreover, when teachers have incorporated PBL into the art and design curriculum, they have recognized affective transformation and built a bridge between classrooms and deep connections with heritage.

9.2 Integrate Technology Use into the Art and Heritage Curriculum

Experiential learning that uses technology can be designed and delivered in different ways that develop the knowledge and skills needed in the digital age (AbuKhousa et al., 2023). Instructors need to improve the curricula for teaching art and design by using technological devices for teaching drawing and design. Education has become formal, and curricula should be planned to be progressive, systematic, and purposeful. Content today revolves around theory and methodology. Curriculum “could simultaneously refer to the content (the race itself), the program (the course being run), and the process, or methods used (the vehicles) during a given race” (McClusky III & Smith, 2008, p. 171).

Other improvements would include using programming software in the art and design classroom and teaching students how to create by sketching their designs. Art and design students want professional instructors to teach art that uses technology. Art professors should guide and interact with students and give them more in terms of their experience in life. When their career experience is added, instruction, career, and personal advice from a professor are aspects that cannot be obtained from technology. Research by Li and Sun (2023) discussed that using technology in teaching improves the interaction between teacher and students, solves problems, increases practical skills, and imparts theoretical knowledge. However, both art and design professors and students need training in the use of technology. Professors can attend workshops for professional development in using technology to teach art or try new programming. They should update their curricula using technology as part of their instruction by learning how to use these devices in the art classroom, how to use software programming to teach students, and how to integrate technology into the art curriculum.

10 Conclusion

This study investigated the relationship between the architectural heritage of the KSA and the USA. The researcher analyzed the similarities and differences in architectural heritage between NM and the KSA, such as instruction, materials, color, and motif units, to design and apply these to develop a range of modern designs and artworks. This study followed a qualitative methodology, incorporating an experiential case study approach through PBL. Thus, the data collection used included observation and analysis of the documents and artifacts. The result presented three themes: (1) similarities in motif units, materials, and colors of the architectural heritage between the Santa Fe and Saudi Najd styles, (2) differences between the architectural heritage doors, windows, and roof systems, and (3) drawing inspiration from architectural heritage for textile bead weaving designs.

Additionally, the implemented experiential approach resulted in six innovative designs that could be developed in various modern artworks with decorative units to produce art pieces using textile weave beading techniques. Different forms of heritage are present worldwide, and students can choose one type of heritage to inspire their ideas. Therefore, teachers can incorporate PBL pedagogy into their curricula, where teaching and learning are transferred from the classroom to an open space and learning about different cultures and heritage.

Recommendations are given for art and design faculty to create classrooms that promote student engagement and interactions, including:

Provide training for teachers in using PBL based on art and architectural heritage,

Design a course for international culture and heritage in arts,

Use the PBL as outdoor adventure activities in teaching arts.

Acknowledgements

The author extends her appreciation to Dr. Loretta Salas, an Associate Professor at NMSU. She is supportive and traveled with me to Santa Fe, explaining different places during the observation.

-

Funding information: The author received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

-

Author contributions: The author confirms the sole responsibility for the conception of the study, presented results and manuscript preparation.

-

Conflict of interest: Authors state no conflict of interest.

References

Abel, A. (2013). Santa Fe folk art market. National Geographic Traveler, 30(4).Suche in Google Scholar

AbuKhousa, E., El-Tahawy, M. S., & Atif, Y. (2023). Envisioning architecture of metaverse intensive learning experience (MiLEx): Career readiness in the 21st century and collective intelligence development scenario. Future Internet, 15(2), 53.10.3390/fi15020053Suche in Google Scholar

Ahmed, A. H., Aseri, A. A., & Ali, K. A. (2022). Geological and geochemical evaluation of phosphorite deposits in northwestern Saudi Arabia as a possible source of trace and rare-earth elements. Ore Geology Reviews, 144, 104854. doi: 10.1016/j.oregeorev.2022.104854.Suche in Google Scholar

Al-Bassam, L. (1985). Traditional inheritance of women’s clothing in Najd. Qatar: Folklore Center.Suche in Google Scholar

Aljahani, T. (2019). Visitor center design and possibilities for visitor engagement at Ad-Dir’iyah heritage site. (Doctoral dissertation). The Florida State University.Suche in Google Scholar

Allen, C., Boddy, J., & Kendall, E. (2019) An experiential learning theory of high level wellness: Australian Salutogenic research. Health Promotion International, 34, 1045–1054. doi: 10.1093/heapro/day051. PMid: 30101338Suche in Google Scholar

Almogren, N. B. A. (2020). Diriyah narrated by Its built environment: the story of the first Saudi State (1744–1818). (Doctoral dissertation). Massachusetts Institute of Technology.Suche in Google Scholar

Alzahrani, A. (2022). Understanding the role of architectural identity in forming contemporary architecture in Saudi Arabia. Alexandria Engineering Journal, 61(12), 11715–11736. doi: 10.1016/j.aej.2022.05.041.Suche in Google Scholar

Bay, M. A., Alnaim, M. M., Albaqawy, G. A., & Noaime, E. (2022). The heritage jewel of Saudi Arabia: A descriptive analysis of the heritage management and development activities in the At-Turaif District in Ad-Dir’iyah, a World Heritage Site (WHS). Sustainability, 14(17), 10718.10.3390/su141710718Suche in Google Scholar

Ben Ali Alsoliman, G. (2019). Role of the technique of reconstruction in the preservation of the heritage buildings. JES. Journal of Engineering Sciences, 47(5), 737–751. doi: 10.21608/jesaun.2019.115735.Suche in Google Scholar

Bleiler, L., & Strong, C. (2012). Santa Fe art and architecture. Arcadia Publishing.Suche in Google Scholar

Costanza-Chock, S. (2020). Design justice: Community-led practices to build the worlds we need. MIT Press.10.7551/mitpress/12255.001.0001Suche in Google Scholar

Creswell, J. W. (2009). Qualitative procedures. Research design: Qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods approaches (pp. 173—202).Suche in Google Scholar

Dye, V. E. (2007). All aboard for Santa Fe: Railway promotion of the Southwest, 1890s to 1930s. UNM Press.Suche in Google Scholar

Elfer, C. J. (2011). Place-based education: A review of historical precedents in theory & practice.Suche in Google Scholar

Ghazala, A. A. S. A. (2021). The concept of visual scope for heritage values and vocabulary as an introduction to restoring urban identity in the twenty-first century. A case study of the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. Architecture Research, 11(1), 1–10. doi: 10.5923/j.arch.20211101.01.Suche in Google Scholar

Govindasamy, P., Abdullah, N., & Ibrahim, R. (2023) The significance and application of creativity skills for special educational needs (SEN) students with learning disabilities in the 21st century learning. Journal of Contemporary Social Science and Education Studies, 3, 39–47. doi: 10.5281/zenodo.10174713 Suche in Google Scholar

Gray, T., & Thomson, C. (2016). Transforming environmental awareness of students through the arts and place-based pedagogies. Learning Landscapes, 9(2), 239–260.10.36510/learnland.v9i2.774Suche in Google Scholar

Guthrie, T. H. (2013). Recognizing heritage: The politics of multiculturalism in New Mexico. University of Nebraska Press.Suche in Google Scholar

Johnson, I., Cohen, A. C., & Sarkar, A. K. (2015). JJ Pizzuto’s fabric science: Studio access card. USA: Bloomsbury Publishing.10.5040/9781501311239Suche in Google Scholar

Jowers, I., Prats, M., Eissa, H., & Lee, J. H. (2010). A study of emergence in the generation of Islamic geometric patterns’. CAADRIA. doi: 10.52842/conf.caadria.2010.039.Suche in Google Scholar

Khamouja, A., Mohamed, M. B., & El Ghouati, A. (2023). Place-based learning and students’ motivation at the second-year baccalaureate level. Journal of Education and Practice, 14(24), 81–87. doi: 10.7176/JEP/14-24-12.Suche in Google Scholar

Kirshenblatt-Gimblett, B. (1998). Destination culture: Tourism, museums, and heritage (Vol. 10). Univ of California Press.10.1525/9780520919488Suche in Google Scholar

Ladachart, L., Poothawee, M., & Ladachart, L. (2020). Toward a place-based learning progression for haze pollution in the northern region of Thailand. Cultural Studies of Science Education, 15, 991–1017. doi: 10.1007/s11422-020-09981-9.Suche in Google Scholar

Lavoie, P., Michaud, C., Belisle, M., Boyer, L., Gosselin, E., Grondin, M., Larue, C., Lavoie, S., & Pepin, J. (2018) Learning theories and tools for the assessment of core nursing competencies in simulation: A theoretical review. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 74, 239–250. doi: 10.1111/jan.13416. PMid: 28815750.Suche in Google Scholar

Leslie, C. A. (2007). Needlework through history: An encyclopedia. USA: Bloomsbury Publishing.10.5040/9798400690372Suche in Google Scholar

Li, Y., & Sun, R. (2023). Innovations of music and aesthetic education courses using intelligent technologies. Education and Information Technologies, 1–24.10.1007/s10639-023-11624-9Suche in Google Scholar

Lovato, A. L. (2004). Santa Fe Hispanic culture: Preserving identity in a tourist town. (1st ed.) University of New Mexico Press.Suche in Google Scholar

Marshall, S. G. (2000). Individuality in clothing selection and personal appearance. New Jersey: Prentice Hall.Suche in Google Scholar

Maruyama, N. U., Yen, T. H., & Stronza, A. (2008). Perception of authenticity of tourist art among Native American artists in Santa Fe, New Mexico. International Journal of Tourism Research, 10(5), 453–466. doi: 10.1002/jtr.680.Suche in Google Scholar

Mathis, B. E. (1999). A place for art: An artists’ community in Santa Fe, New Mexico. (Doctoral dissertation), Texas Tech University Lubbock, Texas.Suche in Google Scholar

Mazzetto, S., & Vanini, F. (2023). Urban heritage in Saudi Arabia: Comparison and assessment of sustainable Reuses. Sustainability, 15(12), 9819. doi: 10.3390/su15129819.Suche in Google Scholar

McClusky III, D. A., & Smith, C. D. (2008). Design and development of a surgical skills simulation curriculum. World Journal of Surgery, 32(2), 171–181.10.1007/s00268-007-9331-9Suche in Google Scholar

Morris, T. H. (2020). Experiential learning–A systematic review and revision of Kolb’s model. Interactive Learning Environments, 28, 1064–1077. doi: 10.1080/10494820.2019.1570279.Suche in Google Scholar

Moscatelli, M. (2023). Rethinking the heritage through a modern and contemporary reinterpretation of traditional Najd Architecture, cultural continuity in Riyadh. Buildings, 13(6), 1471. doi: 10.3390/buildings13061471.Suche in Google Scholar

Murgu, S. D., Kurman J. S., & Hasan O. (2018). Bronchoscopy education: An experiential learning theory perspective. Clinics in Chest Medicine, 39, 99–110. doi: 10.1016/j.ccm.2017.11.002. PMid:29433728.Suche in Google Scholar

Rahmayati, Y., & AlGhunaim, J. (2024). Enhancing city authenticity through humanitarian architecture: A synergy of design and identity, case study, Al-Diriyah, Saudi Arabia. Journal of City: Branding and Authenticity, 1(2), 73–82.10.61511/jcbau.v1i2.2024.411Suche in Google Scholar

Ross, H. C. (1994). The art of Arabia costume: A Saudi Arabian profile. Switzerland: Arabesque Commercial SA.Suche in Google Scholar

Sanchez-Calvillo, A., Alonso-Guzman, E. M., Solís-Sánchez, A., Martinez-Molina, W., Navarro-Ezquerra, A., Gonzalez-Sanchez, B., Arreola-Sanchez, M., & Sandoval-Castro, K. (2023). Use of audiovisual methods and documentary film for the preservation and reappraisal of the vernacular architectural heritage of the State of Michoacan, Mexico. Heritage, 6(2), 2101–2125. doi: 10.3390/heritage6020113.Suche in Google Scholar

Semken, S. (2005). Sense of place and place-based introductory geoscience teaching for American Indian and Alaska Native undergraduates. Journal of Geoscience Education, 53(2), 149–157.10.5408/1089-9995-53.2.149Suche in Google Scholar

Semken, S., Ward, E. G., Moosavi, S., & Chinn, P. W. (2017). Place-based education in geoscience: Theory, research, practice, and assessment. Journal of Geoscience Education, 65(4), 542–562.10.5408/17-276.1Suche in Google Scholar

Smith, L. (2022). Heritage, the power of the past, and the politics of (mis) recognition. Journal for the Theory of Social Behaviour. 52(4), 623–642. doi: 10.1111/jtsb.12353.Suche in Google Scholar

The Ministry of Culture. (2019). Mission statement. https://www.moc.gov.sa/en/About#road-map.Suche in Google Scholar

Thomas H. Guthrie. (2013). Recognizing Heritage : The Politics of Multiculturalism in New Mexico. University of Nebraska Press.10.2307/j.ctt1ddr8k9Suche in Google Scholar

Tolstoy, L. (2023). What is art?. BoD-Books on Demand.Suche in Google Scholar

William W. Dunmire. (2013). New Mexico’s Spanish Livestock Heritage : Four Centuries of Animals, Land, and People. University of New Mexico Press.Suche in Google Scholar

Wilson, C. M. (1981). The Santa Fe, New Mexico Plaza: An architectural and cultural history, 1610–1921. The University of New Mexico. https://www.nmhistoricpreservation.org/assets/files/grants-documents/grants-2021-ft-stanton/Santa%20Fe%20Plaza%20-%20CLR.pdf.Suche in Google Scholar

Yang, Y., Shafi, M., Song, X., & Yang, R. (2018). Preservation of cultural heritage embodied in traditional crafts in the developing countries. A case study of Pakistani handicraft industry. Sustainability, 10(5), 1336. doi: 10.3390/su10051336.Suche in Google Scholar

Yemini, M., Engel, L., & Ben Simon, A. (2023). Place-based education–a systematic review of literature. Educational Review, 1–21.10.1080/00131911.2023.2177260Suche in Google Scholar

Zeuli, K., Rosario Jackson, M, & Beattie, S. (2021). Reckoning with a reckoning: How cultural institutions can advance equity. NonProfit Quarterly, 23. https://nonprofitquarterly.org/reckoning-with-a-reckoning-how-cultural-institutions-can-advance-equity/. Accessed 29 January 2023.Suche in Google Scholar

Zumlot, T., Goodell, P., & Howari, F. (2009). Geochemical mapping of New Mexico, USA, using stream sediment data. Environmental Geology, 58, 1479–1497. doi: 10.1007/s00254-008-1650-0.Suche in Google Scholar

© 2024 the author(s), published by De Gruyter

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Special Issue: Critical Green Theories and Botanical Imaginaries: Exploring Human and More-than-human World Entanglements, edited by Peggy Karpouzou and Nikoleta Zampaki (National and Kapodistrian University of Athens, Greece)

- Critical Green Theories and Botanical Imaginaries: Exploring Human and More-than-Human World Entanglements

- On Vegetal Geography: Perspectives on Critical Plant Studies, Placism, and Resilience

- The Soil is Alive: Cultivating Human Presence Towards the Ground Below Our Feet

- Relational Transilience in the Garden: Plant–Human Encounters in More-than-Human Life Narratives

- “Give It Branches & Roots”: Virginia Woolf and the Vegetal Event of Literature

- Botanical imaginary of indigeneity and rhizomatic sustainability in Toni Morrison’s A Mercy

- Blood Run Beech Read: Human–Plant Grafting in Kim de l’Horizon’s Blutbuch

- “Can I become a tree?”: Plant Imagination in Contemporary Indian Poetry in English

- Gardens in the Gallery: Displaying and Experiencing Contemporary Plant-art

- From Flowers to Plants: Plant-Thinking in Nineteenth-Century Danish Flower Painting

- Becoming-with in Anicka Yi’s Artistic Practice

- Call of the Earth: Ecocriticism Through the Non-Human Agency in M. Jenkin’s “Enys Men”

- Plants as Trans Ecologies: Artifice and Deformation in Bertrand Mandico’s The Wild Boys (2017)

- Ecopoetic Noticing: The Intermedial Semiotic Entanglements of Fungi and Lichen

- Entering Into a Sonic Intra-Active Quantum Relation with Plant Life

- Listening to the Virtual Greenhouse: Musics, Sounding, and Online Plantcare

- Decolonising Plant-Based Cultural Legacies in the Cultural Policies of the Global South

- Special Issue: Safe Places, edited by Diana Gonçalves (Universidade Católica Portuguesa, Portugal) and Tânia Ganito (University of Lisbon, Portugal)

- On Safe Places

- Tracing Exilience Through Literature and Translation: A Portuguese Gargantua in Paris (1848)

- Safe Places of Integration: Female Migrants from Eurasia in Lisbon, Portugal

- “We Are All the Sons of Abraham”? Utopian Performativity for Jewish–Arab Coexistence in an Israeli Reform Jewish Mimouna Celebration

- Mnemotope as a Safe Place: The Wind Phone in Japan

- Into the Negative (Space): Images of War Across Generations in Portugal and Guinea-Bissau. Death is Not the End

- Dwelling in Active Serenity: Nature in Werner Herzog’s Cinema

- Montana as Place of (Un)Belonging: Landscape, Identity, and the American West in Bella Vista (2014)

- Data that Should Not Have Been Given: Noise and Immunity in James Newitt’s HAVEN

- Special Issue: Cultures of Airborne Diseases, edited by Tatiana Konrad and Savannah Schaufler (University of Vienna, Austria)

- Ableism in the Air: Disability Panic in Stephen King’s The Stand

- Airborne Toxicity in Don DeLillo’s White Noise

- Eco-Thrax: Anthrax Narratives and Unstable Ground

- Vaccine/Vaccination Hesitancy: Challenging Science and Society

- Considerations of Post-Pandemic Life

- Regular Articles

- A Syphilis-Giving God? On the Interpretation of the Philistine’s Scourge

- Historical Perceptions about Children and Film: Case Studies of the British Board of Film Censors, the British Film Institute, and the Children’s Film Foundation from the 1910s to the 1950s

- Strong and Weak Theories of Capacity: Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick, Disability, and Contemporary Capacity Theorizing

- Arabicization via Loan Translation: A Corpus-based Analysis of Neologisms Translated from English into Arabic in the Field of Information Technology

- Unraveling Conversational Implicatures: A Study on Arabic EFL Learners

- Noise in the “Aeolus” Episode in Joyce’s Ulysses: An Exploration of Acoustic Modernity

- Navigating Cultural Landscapes: Textual Insights into English–Arabic–English Translation

- The Role of Context in Understanding Colloquial Arabic Idiomatic Expressions by Jordanian Children

- All the Way from Saudi Arabia to the United States: The Inspiration of Architectural Heritage in Art

- Smoking in Ulysses

- Simultaneity of the Senses in the “Sirens” Chapter: Intermediality and Synaesthesia in James Joyce’s Ulysses

- Cultural Perspectives on Financial Accountability in a Balinese Traditional Village

- Marriage Parties, Rules, and Contract Expressions in Qur’an Translations: A Critical Analysis

- Value Perception of the Chronotope in the Author’s Discourse (Based on the Works of Kazakh Authors)

- Cartography of Cultural Practices and Promoting Creative Policies for an Educating City

- Foreign Translators Group in the PRC From 1949 to 1966: A STP Perspective

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Special Issue: Critical Green Theories and Botanical Imaginaries: Exploring Human and More-than-human World Entanglements, edited by Peggy Karpouzou and Nikoleta Zampaki (National and Kapodistrian University of Athens, Greece)

- Critical Green Theories and Botanical Imaginaries: Exploring Human and More-than-Human World Entanglements

- On Vegetal Geography: Perspectives on Critical Plant Studies, Placism, and Resilience

- The Soil is Alive: Cultivating Human Presence Towards the Ground Below Our Feet

- Relational Transilience in the Garden: Plant–Human Encounters in More-than-Human Life Narratives

- “Give It Branches & Roots”: Virginia Woolf and the Vegetal Event of Literature

- Botanical imaginary of indigeneity and rhizomatic sustainability in Toni Morrison’s A Mercy

- Blood Run Beech Read: Human–Plant Grafting in Kim de l’Horizon’s Blutbuch

- “Can I become a tree?”: Plant Imagination in Contemporary Indian Poetry in English

- Gardens in the Gallery: Displaying and Experiencing Contemporary Plant-art

- From Flowers to Plants: Plant-Thinking in Nineteenth-Century Danish Flower Painting

- Becoming-with in Anicka Yi’s Artistic Practice

- Call of the Earth: Ecocriticism Through the Non-Human Agency in M. Jenkin’s “Enys Men”

- Plants as Trans Ecologies: Artifice and Deformation in Bertrand Mandico’s The Wild Boys (2017)

- Ecopoetic Noticing: The Intermedial Semiotic Entanglements of Fungi and Lichen

- Entering Into a Sonic Intra-Active Quantum Relation with Plant Life

- Listening to the Virtual Greenhouse: Musics, Sounding, and Online Plantcare

- Decolonising Plant-Based Cultural Legacies in the Cultural Policies of the Global South

- Special Issue: Safe Places, edited by Diana Gonçalves (Universidade Católica Portuguesa, Portugal) and Tânia Ganito (University of Lisbon, Portugal)

- On Safe Places

- Tracing Exilience Through Literature and Translation: A Portuguese Gargantua in Paris (1848)

- Safe Places of Integration: Female Migrants from Eurasia in Lisbon, Portugal

- “We Are All the Sons of Abraham”? Utopian Performativity for Jewish–Arab Coexistence in an Israeli Reform Jewish Mimouna Celebration

- Mnemotope as a Safe Place: The Wind Phone in Japan

- Into the Negative (Space): Images of War Across Generations in Portugal and Guinea-Bissau. Death is Not the End

- Dwelling in Active Serenity: Nature in Werner Herzog’s Cinema

- Montana as Place of (Un)Belonging: Landscape, Identity, and the American West in Bella Vista (2014)

- Data that Should Not Have Been Given: Noise and Immunity in James Newitt’s HAVEN

- Special Issue: Cultures of Airborne Diseases, edited by Tatiana Konrad and Savannah Schaufler (University of Vienna, Austria)

- Ableism in the Air: Disability Panic in Stephen King’s The Stand

- Airborne Toxicity in Don DeLillo’s White Noise

- Eco-Thrax: Anthrax Narratives and Unstable Ground

- Vaccine/Vaccination Hesitancy: Challenging Science and Society

- Considerations of Post-Pandemic Life

- Regular Articles

- A Syphilis-Giving God? On the Interpretation of the Philistine’s Scourge

- Historical Perceptions about Children and Film: Case Studies of the British Board of Film Censors, the British Film Institute, and the Children’s Film Foundation from the 1910s to the 1950s

- Strong and Weak Theories of Capacity: Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick, Disability, and Contemporary Capacity Theorizing

- Arabicization via Loan Translation: A Corpus-based Analysis of Neologisms Translated from English into Arabic in the Field of Information Technology

- Unraveling Conversational Implicatures: A Study on Arabic EFL Learners

- Noise in the “Aeolus” Episode in Joyce’s Ulysses: An Exploration of Acoustic Modernity

- Navigating Cultural Landscapes: Textual Insights into English–Arabic–English Translation

- The Role of Context in Understanding Colloquial Arabic Idiomatic Expressions by Jordanian Children

- All the Way from Saudi Arabia to the United States: The Inspiration of Architectural Heritage in Art

- Smoking in Ulysses

- Simultaneity of the Senses in the “Sirens” Chapter: Intermediality and Synaesthesia in James Joyce’s Ulysses

- Cultural Perspectives on Financial Accountability in a Balinese Traditional Village

- Marriage Parties, Rules, and Contract Expressions in Qur’an Translations: A Critical Analysis

- Value Perception of the Chronotope in the Author’s Discourse (Based on the Works of Kazakh Authors)

- Cartography of Cultural Practices and Promoting Creative Policies for an Educating City

- Foreign Translators Group in the PRC From 1949 to 1966: A STP Perspective