Abstract

The study aimed at evaluating the effect of using process-oriented guided inquiry learning (POGIL) approach on grade 12 students’ conceptual understanding and achievement in electrochemistry, and assessing students’ attitudes towards the approach. For the purpose a quasi-experimental research approach with a treatment group (TG) and a control group (CG) was employed. The TG students were taught by the POGIL approach while CG students were taught by the lecture method. The data were collected using pretest, posttest, observation, questionnaires, and interviews. Moreover, Cohen’s effect size test was used to evaluate the effect size between the two groups or the magnitude of the intervention. The collected data were analyzed qualitatively and quantitatively. The result of the pretest revealed that no significant difference (p > 0.05) observed between the two groups while a significant difference (p < 0.05) was observed on the posttest. The TG students’ achievement was significantly improved compared to the CG students. The effect size results indicated that small and large effect sizes were observed in pre- and posttests respectively. In general, the study revealed the effectiveness of POGIL in improving students’ conceptual understanding of electrochemistry rather than the lecture method and students have a positive attitude towards the approach.

1 Introduction

Electrochemistry is one of the branches of chemistry that study how chemical reactions produce electricity and how electricity is used to bring about chemical reactions in electrochemical cells. It plays a great role in the practical life. For instance, all sorts of batteries used for different purposes in daily life activities rely on chemical reactions to generate electricity. Besides, the concepts of electrochemistry are used in the isolation, purification, electroplating and extraction of some metals. Nowadays, scientists are using the concepts of electrochemistry to discover new elements, develop useful innovations, understand neuroscience, and for applications in the field of energy. 1 Therefore, chemistry students are expected to have a concrete understanding of electrochemistry concepts. However, many science education researchers reported that many high school students have difficulties understanding electrochemistry concepts and the topic ranked as among the most difficult topics in high school chemistry. 2 , 3 , 4 , 5 , 6

Over the past decades, a significant number of researchers have been involved in identifying students’ difficulties in learning electrochemistry and have studied their causes. High school students have difficulties understanding the concepts of electrochemistry and hold alternative conceptions of electrochemistry concepts such as current flows in electrolyte solutions and the salt bridge. 7 , 8 , 9 Moreover, students have difficulties identifying the components of electrochemical and electrolytic cells such as the anode and cathode; 10 , 11 the functions of the salt bridge; direction of flow of ions in electrochemical cells and reactions occurring at the electrochemical cells; 12 analyzing the electrolysis of molten compounds and aqueous solutions. 13 They also have alternative conceptions of the concept of electrolysis. 6

A plethora of research reports exist on the reasons for students’ learning difficulties in electrochemistry. Some of the identified reasons for the difficulty of electrochemistry concepts are the abstract nature of the topic; 13 , 14 , 15 the fact that most of the processes in electrochemistry are invisible to students and they cannot see the flow of electrons or the movement of ions in aqueous solutions with the naked eye; 3 , 7 , 11 and the cross-curricular nature of the electrochemistry topic. 8 Furthermore, Ali, Woldu and Yohannes 16 revealed that learners’ failure to integrate core ideas with structure-property relationships, misinterpretations of language in scientific contexts and inability to represent chemical phenomena at the macroscopic, particulate, and symbolic levels 17 are some of the challenges that contribute to students’ learning difficulties in electrochemistry. Chemical educators and researchers designed, implemented and suggested several student-centered learning strategies to minimize the challenges and promote students’ learning of electrochemistry. For instance, an interactive multimedia module with pedagogical agents (IMMPA) named Electrochemistry Lab (EC Lab); 13 developed the small-scale experiments involving electrochemistry and the galvanic cell model kit featuring sub-microscopic level; 18 electrochemistry designette; 19 , 20 POGIL; 21 , 22 , 23 problem-based learning (PBL); 24 and view, generate, evaluate, and modify (VGEM) sequence 21 , 22 , 23 were developed and implemented to minimize students’ difficulty of electrochemistry and to enhance students’ attitudes towards the topic.

Nowadays, POGIL is getting more attention and is widely used in science classes. It is a learning approach with a constructivist underpinning which is derived from Piaget’s mental functioning model or development of cognitive reasoning. 25 It encompasses process-oriented inquiry and working in teams which enable learners to participate actively in constructing their own knowledge. According to Piaget’s theory of cognitive development, learning takes place when students connect new scientific concepts to their prior knowledge or old concepts. Moreover, Piaget believed that cognitive development takes place when a learner experiences a cognitively challenging situation and assimilates it. In this regard, extensive evidence has been generated in support of the effectiveness of the POGIL approach in a range of scientific disciplines. 26 , 27 , 28 , 29 , 30 , 31 Eberlein, Kampmeier, Minderhout, Moog, Platt, Varma‐Nelson and White 21 , 22 , 23 compared three different teaching methods in science education such as problem-based learning, POGIL and peer-led team learning and the study revealed that the POGIL approach contributed more to the development of students’ learning capabilities. Barthlow and Watson, 32 also investigated the effect of the POGIL method on changing students’ alternative conceptions about the particulate nature of matter and found that students taught through POGIL had fewer alternative conceptions than those taught using traditional teaching methods. Besides, Şen, Yilmaz and Geban 23 also investigated the effect of using blended POGIL with concept map and lotus blossom techniques on minimizing students’ misconceptions in electrochemistry, and the study revealed the effectiveness of the approach in changing students’ misconceptions compared to traditional teaching methods. This is because the POGIL approach develops both important process skills or cognitive skills (information processing, critical thinking, and problem solving) and group dynamics skills (interpersonal communication, teamwork, and management), which are important in achieving learning goals needed by employer and in the scientific community. 22 , 33 , 34 , 35

Ethiopian education development programs focus on improving students’ achievement by enhancing the teaching and learning process through the transformation of schools into student-centered learning environments. 36 However, Ethiopian high school science teachers’ classes have not changed from being teacher-centered and the classes are still dominated by the traditional lecture approach. Also, students’ achievement in sciences remains unsatisfactory. Besides the aforementioned reported literature on students’ learning difficulties with concepts of electrochemistry, the researcher practically observed and noticed the learning difficulty of high school students in chemistry topics. This prompted a search for alternative student-centered approaches that accommodate students’ learning experiences for a better understanding of the concepts and reduction of misconceptions. As reported in the literature, POGIL is one of the student-centered approaches that is used to teach both content and key process skills and expected to reduce students’ conceptual difficulties. However, there is no such study implemented in Ethiopian high schools to mitigate students’ learning difficulties in electrochemistry, despite students facing significant challenges in comprehending electrochemistry concepts. Therefore, this study intended to investigate the effect of using the POGIL approach on students’ achievement in electrochemistry concepts, and their attitude towards the approach. This study aimed to answer the following research questions: What is the effect of using the POGIL approach on students’ achievement on electrochemistry concepts? What are the students’ attitudes towards the approach?

2 Research methodology

2.1 Background of the participants

The target population of the study was grade 12 natural science students of Mehal-meda Preparatory and Secondary School, Ethiopia. Mehal-meda Preparatory and Secondary School is a public government school and the researcher taught chemistry as a subject at the school for over 13 years. The students who enrolled at the school came from the surrounding community and they have a similar socio-cultural background, economic status, language (they speak Amharic language which is the national working language), and educational background. In fact, in Ethiopia, the majority of middle and upper-income families choose the private school option while lower-income families enroll their children in public schools. In all Ethiopian secondary schools (grades 9–12) English language is used as the medium of instruction and both private and public schools use the same curriculum with the same language of instruction.

Chemistry is taught in Ethiopian secondary schools as a core subject. Grade 12 students’ chemistry textbook has five chapters including base equilibria, electrochemistry, industrial chemistry, polymer chemistry, and introduction to environmental chemistry. This study focused on electrochemistry which comprised Oxidation-Reduction Reactions, Electrolysis of Aqueous solutions, Quantitative Aspects of Electrolysis, Industrial Applications of Electrolysis and Voltaic (Galvanic) Cells. Upon completion of grade 12, the students take the national matriculation examination, prepared by the Ethiopian national examination agency, and those who score a minimum pass mark (50 % score) in the examination are eligible to be admitted to university in the country.

2.2 Design of the study

A quasi-experimental research design was employed to evaluate the effect of the POGIL approach on grade 12 natural science students’ achievement in electrochemistry in the second semester of the 2023 academic year. The researcher randomly selected two of the four sections of grade 12 natural science students as the treatment group (TG;14 males and 19 females) and the other two sections as the control group (CG; 15 males and 23 females). Thus, in this study a total of 71 students (i.e. 33 TG and 38 CG) were randomly selected and participated. Each year, the school administrator distributed students heterogeneously into different sections based on their lower-grade transcript scores (high achievers, middle achievers, and low achievers). Accordingly, each class has lower, medium, and higher achievers; thus, the samples were formed from heterogeneous groups. The ages of participants were also between 18 and 20. The treatment group completed electrochemistry concepts with the POGIL approach while the control group completed the same topic receiving traditional instruction. To avoid information sharing between the two groups, the researchers arranged independent tutorial classes presented on two different days. Accordingly, CG students attended the tutorial classes on Monday and Wednesday while TG students attended the tutorial classes on Tuesday and Thursday. The pretest and posttest were administered to both groups at the beginning and the end of the study period, respectively (Table 1).

Research design of the study.

| Groups | N | Process | Data gathering methods |

|---|---|---|---|

| TG | 33 | POGIL | Pretest, posttest questionnaire, and observation checklist |

| CG | 38 | Lecture approach | Pretest, posttest, and observation checklist |

-

TG, treatment group; POGIL, process-oriented guided inquiry learning; CG, control group.

2.3 Intervention approach for treatment groups

The implementation of a POGIL approach is different from the normal class teaching approach and it has its own implementation procedures. It may be implemented in various ways depending on the nature of proposed goal, class size, the nature of the teaching space, and instructor preferences. 37 However, different implementations have common characteristics such as students working in groups, specifically designed POGIL activities, the teacher having the role of facilitator and coach of the students, and the students completing a work activity with a facilitator. Hence, in this study, the researchers adopted the following POGIL implementation approach and contextualized it by integrating it with electrochemistry.

Students were expected to work collaboratively, generally in groups.

The activities that the students used were POGIL activities, specifically designed guided-inquiry activities for POGIL implementation.

The students worked on the activity during class time with a facilitator present.

The dominant mode of instruction was not lecture or instructor-centered; the instructor served predominantly as a facilitator.

Students had assigned roles within their groups.

The activity was designed to be the first introduction to the topic or specific content.

Students were not expected to have worked on any part of the activity before the class meeting time.

Groups were expected to complete all of the Critical Thinking Questions or equivalently designated questions during class.

Source: https://pogil.org/implementing-pogil.

Prior to the implementation of POGIL, the researchers organized TG students into cooperative learning groups. This is because some researchers reported that students remember the concept more when they engage in cooperative learning and the inquiry approach plays a significant role in scaffolding POGIL. 33 , 34 , 35 Accordingly, the TG students were assigned in to cooperative learning groups (4–5 students in one group) based on their lower grade academic achievement and, in each group, there were a randomly selected group of high achievers, middle achievers, and low achievers (to promote diversity within the groups and avoid self-assignment driven by friendship). The next step was to assign the students into different roles, such as one student assigned as the leader (to ensure that the group process functioned properly), one as secretary (to record the important ideas jotted down by the group members), while the remaining students acted as reflectors. Within such a structure, an independent tutorial class was arranged for both group students (i.e. TG and CG) and they were continuously encouraged to meet with their group members two times per week for 1 h for five consecutive weeks without a regular class schedule.

The researchers selected some challenging electrochemistry topics which students struggled with as reported in the literature namely conductivity, redox reactions (reduction and oxidation), oxidizing and reducing agents, electrolysis of substances in aqueous solution, voltaic or galvanic cells, electrodes and electrode reactions, cathode and salt bridge, half-cell potentials and cell potential. Then, four POGIL models and experimental activities related with the identified topics were designed. Some of the activities were designed by the researchers, while some of them were adopted and contextualized from reported scientific activities. The researchers also prepared questions requiring critical thinking that were directly linked to the models and activities.

The teacher began the tutorial class by providing and explaining the designed model and experimental activities to the students lasting for 10 min. These models and activities guided the student to develop conceptual understanding of the topic through Exploration (students are requested to analyze information provided in a model or diagram), Concept Invention (students combine multiple pieces of data identified in the exploration phase and develop a particular concept), and Application (students apply the newly constructed concepts to new situations). Accordingly, a total of four POGIL models (Oxidation and Reduction; Oxidation, Reduction and Electron Exchange; Electrical Conductivity; and Electrolysis), and experimental activities were prepared on the electrochemistry topic. Then, TG students worked on the planned POGIL models and activities with their cooperative learning groups, following a three-phase POGIL learning cycle (exploration phase, concept invention phase, and application phase). Each group had 40 min to accomplish the activities. Then, the students worked with their group members, analyzed the model and experimental activities in the given time range and answered the questions based on their discussions. While the groups worked, the teacher circulated the classroom and checked the answers recorded by the groups’ secretaries. The teacher intervened and guided students in their learning process when necessary. Sometimes, the teacher interfered in the group discussion and asked the students to respond to the questions requiring critical thinking, encouraging students’ interaction within the group and among the groups. Sometimes the groups shared their experiences with each other. In this way, the groups had the opportunity to compare their answers and thus discuss their differences. The group members reached a consensus and the secretaries compiled the output and prepared a final report for evaluation. The teacher advised the group leaders to report their group’s progress and present that at the end of each activity within 10 min. Then, the group leaders submitted brief reports of their group’s progress at the end of each activity. This process continued in the same way until the assigned activities were accomplished.

2.4 Treatment approach used for control groups

Similar to TG students, the researcher arranged independent tutorial classes for CG students which lasted for five weeks (2 h per day). The researcher organized students in groups (4–5 students in one group) based on their lower-grade academic achievement. The groups were a random mix of high achievers, medium achievers, and lower achievers (to avoid self-selected grouping). Each cooperative learning group, was encouraged to solve selected electrochemistry questions together. During the instruction, the researcher placed more emphasis on selected difficult concepts of electrochemistry reported in the literature, such as redox reaction, oxidizing and reducing agent, conductivity, electrolysis, cell potential, half-cell reactions, electrode and galvanic cells. Then, the researcher defined these selected concepts, gave brief explanations, solved selected problems, gave some additional questions and encouraged students to solve the problems in their groups. To mitigate the potential bias between the treatment and control groups the following were the same: course teacher (chemistry teacher), teaching material (grade 12 students’ chemistry text-book), time coverage (two times per week for 1 h each), worksheet questions, pre- and posttest questions. Thus, the only difference was the implementation approach. In such a way, all the students were kept active, and they were involved in the learning process, the same posttest was administered to both groups at end of the treatment period.

2.5 Data gathering methods

The relevant data were collected from the study participants using multiple instruments (pretest, posttest, questionnaire, interviews and observation).

2.5.1 Electrochemistry concepts test

The researchers developed two types of conceptual tests (pretest and posttest) to evaluate students’ conceptual understanding of electrochemistry. The pretest was developed to evaluate students’ prior knowledge of the topic before the intervention while the posttest was used to compare the effect of the instructions at the end of the study. Accordingly, 20 questions for each test were developed and administered to both group of students.

For example, the following questions were randomly selected from pretest questions.

What is the purpose of a salt bridge in an electro chemical cell?

To provide a source of ions to react at the anode and cathode

To provide a means for electrons to travel from the cathode to the anode

To provide electrical neutrality in the half-cell through migration of ions

To provide a means for electrons to travel from the anode to the cathode

During electrolysis of an aqueous solution of copper sulfate solution using platinum electrodes, the reaction that takes place at the anode is____

Cu2+ + 2e− → Cu

2H2O → 4H+ + O2 + 4e-

Cu → Cu2+ + 2e-

4H+ + O2 + 4e− → 2H2O

In galvanic cell____

Cations move towards the anode and anions towards the cathode

Electrons move from the cathode to the anode in the outside circuit

Cations move towards the cathode and anions towards the anode

Oxidation occurs at the cathode and reduction at the anode

The following questions were randomly selected from the questions designed for the posttest.

Which of the following is the anodic reaction in the discharging of a lead storage battery?

Pb(s) + SO4 2−(aq) → PbSO4(s) + 2e-

PbO2(s) + SO4 2− + 4H+ + 2e− → PbSO4(s) +2H2O(l)

PbSO4 (s) + 2e- → Pb(s) + SO4 2−

PbSO4(s) + 2H2O(l) → PbO2(s) + SO4 2− + 4H+ + 2e−

A solution at 25 °C contains Ni2+, Pt2+, Pd2+ all at 1 M concentrations. Consider the standard reduction potentials

Ni2+ + 2e− → Ni EO = −0.23 V

Pt2+ + 2e− → Pt EO = 1.2 V

Pd2+ + 2e− → Pd EO = 0.99 V

Which metal plate out first when the solution is electrolyzed?

Ni

Pd

Pt

Ni &Pd

The standard cell potential (EO) for the reaction below is 1.10 V. What is the cell potential for this reaction when [Cu2+] = 1 × 10−5 M and [Zn2+] = 1 M?

Zn(s) + Cu2+(aq) → Zn2+(aq) + Cu(s)

1.10 V

0.95 V

1.20 V

1.35 V

2.5.1.1 Content validity and reliability

Prior to use for wide-scale applications, the researchers submitted the prepared pre- and posttest questions to experienced chemistry teachers for content validity evaluation. Then, the teachers checked whether the prepared questions were aligned with the course content and students’ learning experiences. The researchers received comments and critiques from evaluators and made some modifications to ensure high level of validity. Then, they distributed pre- and posttest to a pilot group of students (80 students not part of the sample of the study) and checked the reliability of the tests with Cronbach’s alpha which were 0.811 and 0.910 respectively. The result of Cronbach’s alpha indicates that the items are highly correlated with each other, showing that they contribute in a coherent way to the same underlying concept. Therefore, the two tests are reliable and acceptable. Taber 38 stated that Cronbach’s alpha within the range of 0.71–0.91 is statistically considered as good and in the acceptable range. Then, after ensuring the content validity and reliability of the tests, the researchers administered the two tests to both groups at the beginning and the end of the study respectively.

2.5.2 Questionnaire

The questionnaire was prepared to evaluate TG students’ attitudes towards the implemented POGIL approach. Psychologists agree that attitude has three components namely: cognitive (belief), affective (emotion), and behavioral (observable reaction). 39 Each component has psychometric measurement parameters such as a questionnaire (used to measure cognitive and affective components) and observations (to evaluate the behavior of learners). 33 , 34 , 35 Therefore, a number of questions were prepared to assess students’ attitude towards the implemented approach, the effect of the approach on students’ academic achievement, its suitability in teaching and learning electrochemistry concepts and the challenges that existed. For this purpose, three open-ended and eight closed-ended, ‘yes/no’ type questions were prepared and administered to all TG students.

2.5.3 Observation

The subject teacher (researcher) conducted observations from the start to the end of the intervention with a prepared checklist while TG students were undergoing POGIL class. It was intended to evaluate the level of students’ participation, their interaction during the discussion, their self-confidence when they presented their ideas, their engagement with each other, time management ability, and the drawbacks of the process. The checklist contained four levels of scale (1 = very low, 2 = low, 3 = high, 4 = very high) which were subsequently and changed into percentage.

2.5.4 Interview

The researcher interviewed eight students randomly selected from TG groups (one student from each group) to get detailed information about their experiences in POGIL classes. The students’ response during the interviews were recorded and transcribed into text to make it convenient for data analysis. A code was given for each interviewed student as IS1–IS8. Then, the researchers analyzed each student’s response to individual questions and subsequently regrouped students according to similarities in their ideas. Summaries were then provided for each regrouped cohort.

2.6 Data analysis

The data obtained using different instruments for data collection were analyzed using both quantitative and qualitative analyses. The data collected using pre- and posttests were analyzed by using an independent samples t-test. This is used to compare the means of the population and determine if a statistically significant difference was observed or not. The effect size was used to evaluate the magnitude of the difference between groups. 33 , 34 , 35 The data collected through questionnaires, observation, and interviews were analyzed using Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS 27). The data from students’ semi-structured interviews were transcribed and analyzed qualitatively.

3 Results and discussion

3.1 The pretest and posttest results

The result of a comparative analysis of the two groups on the pre- and posttests is reported in Table 2. The pretest results revealed that no statistically significant difference was observed between the two groups before the intervention. This means that the two groups were found to be similar in terms of preknowledge and suitable to use for a comparison of the effects of using the POGIL approach with the lecture method on the conceptual understanding of electrochemistry.

Comparison of pretest and posttest results of both groups using an independent sample t-test.

| Test | Group | N | Mean | SD | df | MD | t-value | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pretest | TG | 33 | 3.13 | 1.80 | 69 | 0.07 | −0.20 | 0.859a |

| CG | 38 | 3.20 | 1.96 | |||||

| Posttest | TG | 33 | 12.72 | 4.17 | 69 | 4.12 | 4.50 | 0.000b |

| CG | 38 | 8.60 | 3.50 |

-

aNot significant at p > 0.05; bSignificant at p < 0.05; TG, treatment group; CG, control group; N, number of TG and CG students; SD, standard deviation; df, degree of freedom; MD, mean difference.

In contrast, a statistically significant difference was observed between the two groups on the posttests. The treatment group students performed better in the posttest exam than the control group students (Table 2). This shows the effectiveness of POGIL in improving students’ understanding which, in turn, enhanced their achievement in electrochemistry. This result is in agreement with earlier reported studies on the effectiveness of the POGIL approach in enhancing students’ academic achievement in different chemistry concepts. For instance, Suwarni, Hastuti and Mulyani 28 evaluated the impact of the POGIL model combined with a Science–Technology–Society-Environment approach on chemical literacy and science process skills on buffer solutions, and he stated that the approach played a significant role in elevating students’ chemical literacy and science process skills. Vincent-Ruz, Meyer, Roe and Schunn 40 investigated the short-term and long-term effects of POGIL on students’ understanding and attitude towards a General Chemistry Course and the study revealed the significance of the approach in improving students’ achievement and attitudes. Other researchers also reported that POGIL helps students to build and restructure their knowledge, develops their higher-order thinking skills, and improves conceptual understanding. 41

3.2 The effect size measures of the two groups

In addition to the independent samples t-test, we used Cohen’s (d) effect size test to determine the size of the difference between the two groups or the magnitude of the effect of the intervention. We calculated the effect size of the pretest and posttest which were 0.037 and 1.070 respectively. Cohen 42 interpreted that an effect size d of 0.2 is small, 0.5 is medium, and 0.8 or above is a large effect. Accordingly, the effect size of the pretest result indicates that the difference between the TG and CG on the pretest is negligible while a large difference was observed on the posttest (1.070). The large effect size of the posttest result signifies the large favorable effect of the intervention (Table 3).

The effect size measures of the two groups.

| Test | Group | Mean | SD | MD | SDP | Cohen’s (d) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pretest | TG | 3.13 | 1.80 | 0.07 | 1.88 | 0.037 |

| CG | 3.20 | 1.96 | ||||

| Posttest | TG | 12.72 | 4.17 | 4.12 | 3.85 | 1.070 |

| CG | 8.60 | 3.50 |

-

SDP, pooled standard deviation; MD, mean difference.

The effect size result indicates that the effect of the intervention was high compared to the traditional. lecture method. Several researchers also reported the effectiveness of POGIL in improving students’ performance. For instance, Hein 26 compared the final exam results of students who completed an organic chemistry course by the POGIL approach with the traditional lecture approach and the result revealed that students taught by the POGIL method had better content knowledge and achieved better in the final exam than the students taught by the traditional lecture approach. Furthermore, Boda and Weiser 43 studied the effect of using POGIL in challenging students’ preconceptions in an introductory chemistry course and they revealed the effectiveness of the approach in reducing students’ misconceptions and enhancing their achievement in introductory chemistry courses. Wilujeng, Wibowo and Haris 29 investigated the effect of the POGIL learning model on high school students’ problem-solving abilities in thermodynamics and their findings indicated that POGIL has a significant effect on improving high school students’ problem-solving abilities in thermodynamics concepts.

3.3 Comparison between treatment and control group students on targeted electrochemistry questions

The researchers also analyzed individual student’s exam script performance on selected and targeted electrochemistry questions which required critical thinking and compared the results between the two groups (Figure 1).

Comparison of performance between TG and CG in selected concepts.

For questions focused on the conductivity of metals and electrolytes, about 69.5 % of TG and 50.0 % of the CG students gave correct answers. For questions focused on the redox reactions, about 63.0 % of TG and 37.5 % of the CG students gave correct answers. However, the majority of CG students failed to give correct answers. For questions focused on the concept of oxidizing and reducing agents, about 65.0 % of the TG, and 42.5 % of the CG students gave correct answers while majority of CG students did not. For questions focused on the concept of electrolysis of substance in aqueous solution, about 73.8 % of TG students and 52.5 % of CG students gave correct answers. For the items focused on the concept of electrode and electrode reactions, about 67.3 % of TG students and 45.0 % of CG students gave correct answers. For these questions the majority of CG students failed to give proper answers. For questions focused on the concept of voltaic cells, about 71.6 % of TG and 55.0 % of CG students gave correct answers. For questions focused on the identification of electrodes (the anode and cathode), about 76.0 % of TG and 37.5 % of CG students gave correct answers. Similarly, for these questions the majority of CG students couldn’t properly distinguish electrodes (the anode and cathode) compared to TG students. For questions focused on the purpose of the salt bridge and how it works, about 82.5 % of TG and 52.5 % of CG students gave correct answers. This indicates that the majority of TG students understood the purpose of the salt bridge and answered the given questions correctly, whereas only about half of CG students understood the concept. This may be attributed to the fact that during the POGIL session, the TG students conducted a galvanic cell experiment which could promote a better understanding of the migration of cations and anions (i.e. the cation migrates towards the anode and anions towards the cathode). However, many of the CG students remained confused about the migration of cations and anions. It is evident from the posttest result, that, compared to CG students, the TG students understood the concept of oxidizing and reducing agents, distinguishing the substance that could be oxidized and reduced in redox reactions. As before, the majority of CG students remained confused about redox reactions. Overall, from the above selected targeted questions analysis, it is evident that TG students understood electrochemistry concepts better than CG students who completed the topic with a traditionally designed lecture method. This outcome can be ascribed to the effect of the POGIL approach. Several other researchers also reported that students who experienced even a few inquiry activities developed more self-confidence, possessed high science process skills and critical thinking, and were unafraid of doing science. 28 , 29

3.4 Attitudes

The researchers used open and closed-ended questions to evaluate the cognitive and affective components of student attitude while observation was used to evaluate the behavioral component (students’ participation in group work, confidence in asking and answering questions, interaction, and interest or participation). A detailed description of TG students’ interview data will be presented in this section.

3.4.1 Observation of treatment group

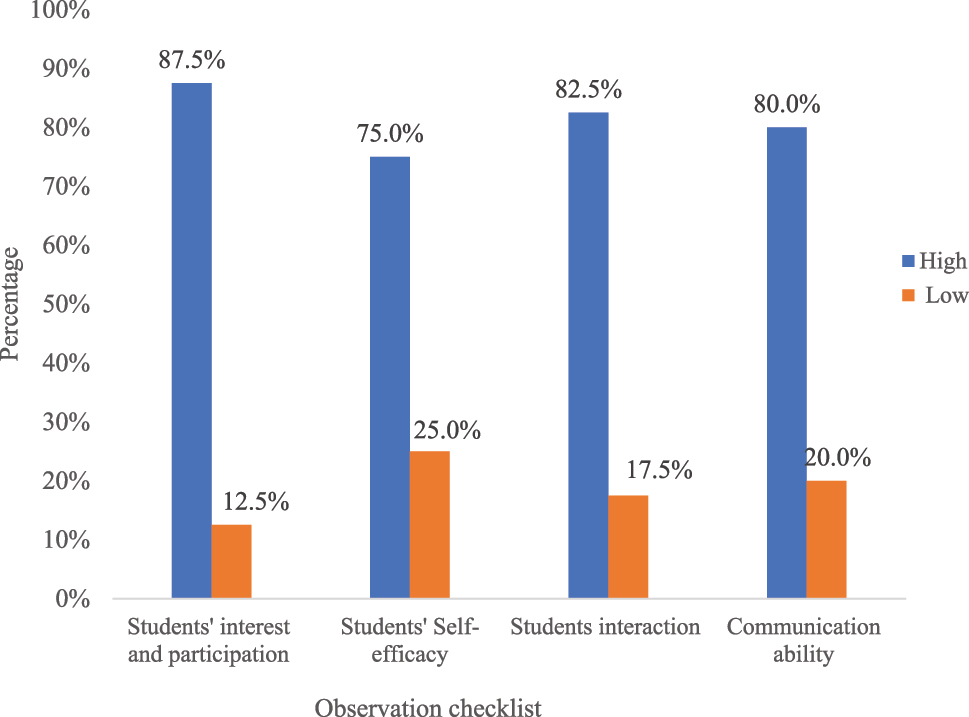

The researcher evaluated the overall learning environment in POGIL sessions while TG students participated in different activities by preparing an observation checklist on students’ interest and participation, self-efficacy, interaction, and communication ability. The evaluation results are presented in Figure 2.

Summary of observation checklist results.

During the intervention process, about 87.5 % of TG students have shown high interest and actively participated in performing practical activities, in group discussions, and in answering questions. However, about 12.5 % of students didn’t actively participate in group discussions and they only observed and listened to what others did. This may be due to group work not being their preferred learning style. Mundy and Potgieter 44 also reported that because students’ learning styles vary from individual to individual, the POGIL approach may be difficult for some students. Self-efficacy is important to achieve the designated goals. Bandura 45 defined self-efficacy as people’s judgments of their capabilities to organize and execute courses of action required to obtain designated types of performance. About 75.0 % of TG students showed self-efficacy (in reflecting or presenting their ideas). A number of researchers also reported that POGIL enhances student’s self-efficacy. 40 , 46 , 47 , 48 , 49 , 50 In contrast, about 25.0 % of students were shown with a weak sense of self-efficacy. This might be due to those students are at level of academic development stage and they need more help from the teacher through conventional instructions. According to Mundy and Potgieter, 44 students in the academic development program often lacked confidence in their own work and looked to the instructor for guidance, which is at odds with the student-centered nature of the POGIL approach. In the same way, about 82.5 % of students actively engaged and interacted with their peers during group work or in solving problems. However, about 17.5 % of students showed little interaction. Worth mentioning is that students’ interaction and discussion habits were low at the beginning of the POGIL class. However, they gradually developed interaction habits through the course of intervention. About 80 % of TG students developed communication skills through interaction with their peers by the end of the course. This idea was also raised during students’ interviews. Other studies also reported that POGIL enhances students’ communication skills. 51 , 52 However, about 20 % of them showed weak communication skills, which may be due to an instructional language barrier between primary and secondary schools. In the primary school, students learned all subjects except English (which was taught as a standalone subject) in mother tongue. In contrast, high school uses English as the medium of instruction and all subjects are taught in English. A number of researchers also emphasized the importance of instructional language on students’ communication ability and their understanding of complex chemical concepts. 53

3.4.2 Analysis of students’ response to close-ended questions

All TG students were asked to provide feedback on their experiences in the tutorial classes that employed POGIL (Table 4).

Students’ response to closed-ended questionnaires related to the used POGIL experience.

| No | Statement | % of respondents | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Positive | Neutral | Negative | ||

| 1 | I am able to understand electrochemistry concepts without too much difficulty. | 55.0 | – | 45.0 |

| 2 | The POGIL approach was a good way to learn electrochemistry concepts. | 87.5 | 5.0 | 7.5 |

| 3 | POGIL helped me to understand electrochemistry concepts and improve my achievement. | 97.5 | 2.5 | – |

| 4 | I am interested in POGIL class. | 92.5 | 7.5 | – |

| 5 | I felt that POGIL helped me to participate in group work on activities. | 77.5 | 2.5 | 10.0 |

| 6 | POGIL activities helped me to understand theoretical concepts of electrochemistry. | 82.5 | 17.5 | – |

| 7 | The POGIL approach helped me to evaluate my understanding level (it showed me what I know, I didn’t know, and what I need to learn more about). | 87.5 | 12.5 | – |

| 8 | The POGIL approach helped me to like the electrochemistry concepts. | 90.0 | 7.5 | 2.5 |

For question 1, ‘I am able to understand electrochemistry concepts without too much difficulty’, more than half (55.0 %) of TG students gave positive responses while about 45.0 % of them gave negative responses. Almost half of the students didn’t deny the difficulty of electrochemistry concepts for different reasons. Question 2 which focused on the suitability of the approach in learning electrochemistry topics about 87.5 % of the respondents gave positive responses. This indicates that the majority of them believed POGIL is suitable to learn electrochemistry topic. For the question related to the impact of the POGIL approach for understanding and improving students’ achievement in electrochemistry, about 97.5 % of respondents provided positive responses for the given statement. Almost all of the students believed that the approach was useful in improving their understanding and achievement. This is in line with studies conducted in other countries. For instance, a study conducted in the US revealed that using the POGIL approach in a general chemistry course significantly improved students’ achievement. 47

For question 4 which focused on students’ interest in POGIL, about 92.5 % of respondents gave positive responses. It is evident from students’ responses, that the POGIL approach enhanced students’ interest and this in turn improved students’ participation. Other studies also reported that students’ achievement is directly correlated with their interest. For instance, Cascolan 54 investigated the effect of using the POGIL approach in a chemistry course for Bachelor of Industrial Technology (BIT) students on their academic performance, motivational orientation, and self-regulated learning strategies. The result of the study revealed that a significant difference was observed in the motivational orientation and self-regulated learning strategies, and students who experienced POGIL showed high motivation and better academic performance than students in a traditional class. Moreover, Yuliastini, Rahayu, Fajaroh and Mansour 55 emphasized the importance of motivation in learning because students who have high motivation are actively involved in the learning process, try to learn diligently, and feel happy and optimistic in accomplishing the tasks given by the teacher. Similarly, for the question 5, which focused on the suitability of the POGIL approach in participating students in different group work activities, about 77.5 % of students had positive attitudes or agreed with the statement. This revealed that the structure of the approach helped students work together on different group activities and this improved their understanding and achievement. This result is in line with other reported studies. For example, the study conducted by Beck and Miller 56 revealed that the POGIL approach actively engages students in scientific practices and enhance their understanding. For the question 6, which focused on the effect of designed POGIL activities on students’ conceptual understanding of electrochemistry, about 82.5 % of students had positive attitudes or agreed with the statement. This indicates that the designed POGIL activities helped them to understand the basic concepts of the electrochemistry topic.

For question 7, focusing on the value of the POGIL approach to help students evaluate their own level of conceptual understanding, about 87.5 % of TG students agreed with the given statement. This indicates that POGIL helped them to recognize their own understanding level (helped them to evaluate what they know, what they didn’t know, and what they need to learn more about during discussions with their colleagues). For question 8 related to the effect of the approach in enabling students to like the electrochemistry topic, about 90.0 % of TG students agreed with the given statement. This indicates, that the approach helped the students to develop a positive attitude towards electrochemistry topic. This study is in line with the other studies reported on the effect of POGIL on students’ motivation. 57 , 58 Similarly, Santoso, Sumari and Setiadi 59 evaluated the effect of POGIL on students’ cognitive achievement and learning motivation on the acid-base topic and concluded that POGIL enhances students’ cognitive achievement and learning motivation.

3.4.3 Analysis of interview data

The researcher interviewed selected TG students at the end of the class using the following questions:

Do you think POGIL would help you to improve your understanding and achievement in electrochemistry? If your answer is yes, how? If no, why?

Do you think the POGIL approach has improved your interaction with your colleagues? If your answer is yes, how? If no, why?

Did you like the way this tutorial session was run? If your answer is yes, why? If no, why?

For the first question the majority of interviewed students explained that the POGIL approach helped them to understand the electrochemistry concepts and this in turn improved their achievement. Students explained that they had intensive group discussions during problem solving and this helped them better understand the concept.

For example, one student (IS3) replied that “I believe that learning the topic of electrochemistry using POGIL approach is interesting. During the POLGIL session we had good discussions with our colleagues, asking each other what we didn’t know and briefing each other on what we knew [more]. This helped me understand what I didn’t know and allowed me to share my understanding with my colleagues. This improved my understanding and contributed to my achievement”.

During the interview, students particularly acknowledged the importance of the POGIL approach in increasing students’ interaction (group work), and this significantly improved their conceptual understanding. Stanford, Moon, Towns and Cole 60 stated that collaborative discourse allows students to share ideas, get immediate feedback, and practice scientific arguments which enhances their conceptual understanding. Other studies also reported the effect of the approach in engaging students in group discussion and such fruitful engagement enhanced their conceptual understanding, confidence, and academic achievement. 40 , 47 , 57 , 61 Moreover, Aiman and Hasyda 62 stated that POGIL helped students to explore teaching materials, receive immediate feedback, and significantly improve their scientific concepts.

For the second question many students believed that POGIL approach created a chance for them to discuss with their colleagues freely.

For instance, one student (IS5) replied that: “…I can say simply, the approach improved my teamwork skills, interaction and communication skills. I believe that the approach helped students’ problem-solving ability. While we were together, we can predict the solution for the displayed questions based on the displayed model and solve the problems [more] easily than alone”.

During the interview, students appreciated the way they learned the topic compared to the usual lecture method. It is evident from students’ responses that the POGIL approach helped them to engage in group discussion (asking, answering, and explaining questions) and this enhanced their communication skills and problem-solving ability which, in turn, helped to improve their academic achievement. Several studies also reported that POGIL promotes students’ confidence, communication skills, problem-solving ability, interaction, autonomous learning, self-efficacy, and perseverance in learning. 46 , 57 , 63 Yalcinkaya, Boz and Erdur-Baker 48 reported that attempts to solve real-world problems through the POGIL approach improved students’ engagement, achievement and self-efficacy.

The third question focused on the evaluation of overall student attitudes towards the POGIL approach. Consequently, almost all interviewed students appreciated the way they learned electrochemistry with the POGIL approach.

For instance, one student (IS4) responded that “When I faced the concepts of electrochemistry at [an] earlier grade, it was challenging and I was worried about it. I thought the way we learned the topic was not [as] attractive as POGIL. POGIL approach is very nice in stark contrast with [the] earlier approach. Now my understanding of electrochemistry is improved and I like the way we learned the electrochemistry concepts/topic”.

Another student also replied (IS6) that:

“I did not know this method up to now. But now [I] proved on [to] myself, the method is very useful. I wish better if other teachers will also use it. Better if we adopt this approach in our normal classes”.

It is evident from students’ responses that they have a positive attitude towards the POGIL approach and electrochemistry concepts as a result of the intervention. In a POGIL session students engaged in conversations with each other to explain their answers to questions or ask each other. This increased students’ communication skills, thinking skills, and problem-solving skills. The paths helped them to process information, organize information, and retrieve information when necessary. This study is in line with other earlier reported findings. For instance, several researchers also demonstrated that using POGIL improved student retention in the course, enabled students to have positive attitudes towards the course, and enhance students’ process skills and academic performance. 26 , 40 , 41 , 50 , 63 , 64 , 65 Moreover, Vishnumolakala, Southam, Treagust, Mocerino and Qureshi 46 revealed that POGIL creates a conducive learning environment for learning and helps students develop an interest in chemistry.

It is worth mentioning that during the interviews, some students pointed out that time limitation is the major drawback observed during POGIL implementation. Mundy and Potgieter 44 also reported that time constraints are one of the major limitations of POGIL implementation and this needs special attention. Besides, Al Neyadi 50 stated time constraints are among the major reasons for teachers as well as for students to adopt other active learning strategies. Therefore, careful design of models, questions, activities, and assessment mechanisms is crucial to address the students’ concern about time limitations observed in POGIL implementation.

4 Conclusions

Ethiopian high school science teachers’ classes were dominated by teacher-centered teaching methods and students’ learning outcomes remain poor. To improve students’ understanding and reduce learning difficulties, the researchers implemented the POGIL approach for the electrochemistry concepts. The findings of the study indicate that the POGIL approach has a significant effect in improving students’ conceptual understanding of electrochemistry and students’ achievement on the topic compared to the lecture method. The result of the calculated effect size (Cohen’s d = 1.07) indicates a large effect on the posttest, which is due to the intervention. Besides, the researcher categorized the analysis of students’ responses to the closed-ended questionnaire, observation and interviews into three main ideas. The first point deals with the importance of POGIL in enhancing students’ interest and participation. The second point emphasized the importance of POGIL in creating an opportunity for discussion and sharing of ideas among group members and enhancing communication. The third point is enhancing students’ problem-solving skills/experiences. Overall, the analysis of students’ attitudes signifies that POGIL enhances students’ achievement’, interest, the experience of working together, and engagement in the activities. TG Students also have shown a positive attitude towards the POGIL approach.

5 Recommendations

The overall analysis of the study revealed that POGIL improves students’ understanding of electrochemistry concepts and students have a positive attitude towards the approach and the subject. Therefore, it would be better if chemistry teachers adopt and implement the POGIL approach to minimize students’ difficulty in electrochemistry, improve their understanding and achievement, and improve students’ attitudes towards the topic. However, since the implementation of POGIL was new in our school we faced some challenges. For instance, there was no prearranged setup for the implementation of POGIL including group arrangements, designed models, necessary resources for activities, and assessment techniques. Moreover, the approach demands strong commitment from both teachers and students, robust assessment mechanisms, and access to facilities like laboratory equipment and chemicals for in-school activities. Thus, these limitations need to be addressed before the implementation of POGIL. We recommend that educational stakeholders consider the challenges and limitations of POGIL and provide the necessary support by working closely with school teachers for effective implementation of the approach.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the support of Mehal-Meda Preparatory and Secondary School principals and Haramaya University, Department of chemistry staff members for their invaluable support during the research work. Besides, the authors would like to thank all grade 12 natural science students of 2023 Academic Year who participated in this study.

-

Research ethics: Haramaya University Ethics review committee.

-

Informed consent: Available with the corresponding author.

-

Author contributions: ABZ contributed in data curation; ATE contributed in data curation and writing the original draft of the manuscript; DB contributed in data curation and editing the manuscript.

-

Use of Large Language Models, AI and Machine Learning Tools: Not applicable.

-

Conflict of interest: The researchers involved in this study declared that they have no conflict of interest.

-

Research funding: None declared.

-

Data availability: The datasets generated during and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

1. Brett, C. M.; Oliveira-Brett, A. M. Future Tasks of Electrochemical Research. J. Solid State Electrochem. 2020, 24 (9), 2051–2052; https://doi.org/10.1007/s10008-020-04696-x.Suche in Google Scholar

2. Rosenthal, D. P.; Sanger, M. J. Student Misinterpretations and Misconceptions Based on their Explanations of Two Computer Animations of Varying Complexity Depicting the Same Oxidation–Reduction Reaction. Chem. Educ. Res. Pract. 2012, 13 (4), 471–483; https://doi.org/10.1039/C2RP20048A.Suche in Google Scholar

3. Schmidt, H. J.; Marohn, A.; Harrison, A. G. Factors that Prevent Learning in Electrochemistry. J. Res. Sci. Teach.: Official J. Natl. Assoc. Res. Sci. Teach. 2007, 44 (2), 258–283; https://doi.org/10.1002/tea.20118.Suche in Google Scholar

4. Turner, K. L.; He, S.; Marchegiani, B.; Read, S.; Blackburn, J.; Miah, N.; Leketas, M. Around the World in Electrochemistry: A Review of the Electrochemistry Curriculum in High Schools. J. Solid State Electrochem. 2023, 1–14; https://doi.org/10.1007/s10008-023-05548-0.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

5. Oladejo, A. I.; Ademola, I. A.; Ayanwale, M. A.; Tobih, D. Concept Difficulty in Secondary School Chemistry–An Intra-Play of Gender, School Location and School Type. J. Technol. Sci. Educ. 2023, 13 (1), 255–275; https://doi.org/10.3926/jotse.1902.Suche in Google Scholar

6. Nakiboglu, C.; Rahayu, S.; Nakiboğlu, N.; Treagust, D. F. Exploring Senior High-School Students’ Understanding of Electrochemical Concepts: Patterns of Thinking Across Turkish and Indonesian Contexts. Chem. Educ. Res. Pract. 2024, 25 (1), 42–61; https://doi.org/10.1039/D3RP00124E.Suche in Google Scholar

7. Duan, X.; Wang, L.; Li, G.; Liu, X.; Wan, M.; Du, J.; Zhan, R.; Wang, W.; Li, Y.; Tu, S.; Shen, Y.; Seh, Z. W.; Sun, Y. Revealing the Intrinsic Uneven Electrochemical Reactions of Li Metal Anode in Ah-level Laminated Pouch Cells. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2023, 33 (6), 2210669; https://doi.org/10.1002/adfm.202210669.Suche in Google Scholar

8. Turner, K. L.; He, S.; Marchegiani, B.; Read, S.; Blackburn, J.; Miah, N.; Leketas, M. Around the World in Electrochemistry: A Review of the Electrochemistry Curriculum in High Schools. J. Solid State Electrochem. 2024, 28 (3), 1361–1374; https://doi.org/10.1007/s10008-023-05548-0.Suche in Google Scholar

9. Akram, M.; Surif, J. B.; Ali, M. Conceptual Difficulties of Secondary School Students in Electrochemistry. Asian Soc. Sci. 2014, 10 (19), 276; https://doi.org/10.5539/ass.v10n19p276.Suche in Google Scholar

10. Garnett, P. J.; Treagust, D. F. Conceptual Difficulties Experienced by Senior High School Students of Electrochemistry: Electric Circuits and Oxidation-Reduction Equations. J. Res. Sci. Teach. 1992, 29 (2), 121–142; https://doi.org/10.1002/tea.3660290204.Suche in Google Scholar

11. Lin, C.-Y.; Wu, H.-K. Effects of Different Ways of Using Visualizations on High School Students’ Electrochemistry Conceptual Understanding and Motivation Towards Chemistry Learning. Chem. Educ. Res. Pract. 2021, 22 (3), 786–801; https://doi.org/10.1039/D0RP00308E.Suche in Google Scholar

12. Dorsah, P.; Yaayin, B. Altering Students Misconceptions in Electrochemistry Using Conceptual Change Texts. Int. J. Innov. Res. Dev. 2019, 8 (11), 33–44; https://doi.org/10.24940/ijird/2019/v8/i11/NOV19021.Suche in Google Scholar

13. Tien, L. T.; Osman, K. Misconceptions in Electrochemistry: How do Pedagogical Agents Help? Overcoming Students’ Misconceptions Sci. Strateg. Perspect. Malaysia 2017, 91–110; https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-10-3437-4_6.Suche in Google Scholar

14. Rogers, F.; Huddle, P. A.; White, M. D. Using a Teaching Model to Correct Known Misconceptions in Electrochemistry. J. Chem. Educ. 2000, 77 (1), 104; https://doi.org/10.1021/ed077p104.Suche in Google Scholar

15. Nurkhasanah, M. F.; Rohaeti, E. Development of Electronic Student Worksheet Based on Problem Based Learning on Electrochemical Materials. Jurnal Penelitian Pendidikan IPA 2024, 10 (2), 988–995; https://doi.org/10.29303/jppipa.v10i2.6185.Suche in Google Scholar

16. Ali, M. T.; Woldu, A. R.; Yohannes, A. G. High School Students’ Learning Difficulties in Electrochemistry: A Mini Review. African J. Chem. Educ. 2022, 12 (2), 202–237.Suche in Google Scholar

17. Osman, K.; Lee, T. T. Impact of Interactive Multimedia Module with Pedagogical Agents on Students’ Understanding and Motivation in the Learning of Electrochemistry. Int. J. Sci. Math. Educ. 2014, 12, 395–421; https://doi.org/10.1007/s10763-013-9407-y.Suche in Google Scholar

18. Supasorn, S. Grade 12 Students’ Conceptual Understanding and Mental Models of Galvanic Cells Before and After Learning by Using Small-Scale Experiments in Conjunction with a Model Kit. Chem. Educ. Res. Pract. 2015, 16 (2), 393–407; https://doi.org/10.1039/C4RP00247D.Suche in Google Scholar

19. Chia, V. Y.; Holtta-Otto, K.; Anariba, F. Using the Electrochemistry Designette to Visualize Students’ Competence and Misconceptions on Electrochemical Principles. J. Chem. Educ. 2022, 99 (3), 1533–1538; https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.jchemed.1c00773.Suche in Google Scholar

20. Tan, S. Y.; Chia, V. Y.; Hölttä-Otto, K.; Anariba, F. Teaching the Nernst Equation and Faradaic Current Through the Use of a Designette: An Opportunity to Strengthen Key Electrochemical Concepts and Clarify Misconceptions. J. Chem. Educ. 2020, 97 (8), 2238–2243; https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.jchemed.9b00932.Suche in Google Scholar

21. Şen, Ş.; Yılmaz, A.; Geban, Ö. The Effects of Process Oriented Guided Inquiry Learning Environment on Students’ Self-Regulated Learning Skills. Probl. Educ. 21st Century 2015, 66 (1), 54–66. https://doi.org/10.33225/pec/15.66.54.Suche in Google Scholar

22. Aini, F. Q.; Fitriza, Z.; Iswendi, I.; Rivaldo, I.; Mawardi, M.; Putri, A. K. Enhancing Students’ Science Process Skills Through the Implementation of POGIL-Based General Chemistry Experiment Manual: A Quantitative Study. Hydrogen: J. Kependidikan Kimia 2023, 11 (2), 116–128; https://doi.org/10.33394/hjkk.v11i2.7498.Suche in Google Scholar

23. Şen, Ş.; Yilmaz, A.; Geban, Ö. The Effect of Process Oriented Guided Inquiry Learning (POGIL) on 11th Graders’ Conceptual Understanding of Electrochemistry. In Asia-Pacific Forum on Science Learning and Teaching. Vol. 17; The Education University of Hong Kong, 2016; pp. 1–8. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/314949073.Suche in Google Scholar

24. Günter, T.; Alpat, S. K. The Effects of Problem-Based Learning (PBL) on the Academic Achievement of Students Studying ‘Electrochemistry. Chem. Educ. Res. Pract. 2017, 18 (1), 78–98; https://doi.org/10.1039/c6rp00176a.Suche in Google Scholar

25. Eberlein, T.; Kampmeier, J.; Minderhout, V.; Moog, R. S.; Platt, T.; Varma-Nelson, P.; White, H. B. Pedagogies of Engagement in Science: A Comparison of PBL, POGIL, and PLTL. Biochem. Mol. Biol. Educ. 2008, 36 (4), 262–273; https://doi.org/10.1002/bmb.20204.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

26. Hein, S. M. Positive Impacts Using POGIL in Organic Chemistry. J. Chem. Educ. 2012, 89 (7), 860–864; https://doi.org/10.1021/ed100217.Suche in Google Scholar

27. Roller, M. C.; Zori, S. The Impact of Instituting Process-Oriented Guided-Inquiry Learning (POGIL) in a Fundamental Nursing Course. Nurse Educ. Today 2017, 50, 72–76; https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nedt.2016.12.003.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

28. Suwarni, P. A.; Hastuti, B.; Mulyani, B. Impacts of the POGIL Learning Model Combined with a SETS Approach on Chemical Literacy and Science Process Skills in the Context of Buffer Solutions. JKPK J. Kim. Dan. Pendidik. Kim. 2024, 9 (1), 171–184; https://doi.org/10.20961/jkpk.v9i1.850576.Suche in Google Scholar

29. Wilujeng, I.; Wibowo, H. A. C.; Haris, A. The Effect of the POGIL Learning Model on High School Students’ Problem Solving Abilities in Thermodynamics. Phi: Jurnal Pendidikan Fisika dan Terapan 2024, 10 (2), 67–73; https://doi.org/10.22373/p-jpft.v10i2.25018.Suche in Google Scholar

30. Lin, S.-C.; Lee, H.-p. The Impact of Process-Oriented Guided Inquiry Learning on Students’ Academic Achievement and Capacities for Collaboration and Problem-Solving. J. Soc. Sci. Stud. 2023, 10 (2), 111; https://doi.org/10.5296/jsss.v10i2.21548.Suche in Google Scholar

31. Brown, S. D. A Process-Oriented Guided Inquiry Approach to Teaching Medicinal Chemistry. Am J Pharm Educ. 2010, 74 (7), 121; https://doi.org/10.5688/aj7407121FromNLMMedline.Suche in Google Scholar

32. Barthlow, M. J.; Watson, S. B. The Effectiveness of Process-Oriented Guided Inquiry Learning to Reduce Alternative Conceptions in Secondary Chemistry. School Sci. Math. 2014, 114 (5), 246–255; https://doi.org/10.1111/ssm.12076.Suche in Google Scholar

33. Reynders, G.; Suh, E.; Cole, R. S.; Sansom, R. L. Developing Student Process Skills in a General Chemistry Laboratory. J. Chem. Educ. 2019, 96 (10), 2109–2119; https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.jchemed.9b00441.Suche in Google Scholar

34. Idul, J. J. A.; Caro, V. B. Does Process-Oriented Guided Inquiry Learning (POGIL) Improve Students’ Science Academic Performance and Process Skills? Int. J. Sci. Educ. 2022, 44 (12), 1994–2014; https://doi.org/10.1080/09500693.2022.2108553.Suche in Google Scholar

35. Walker, L.; Warfa, A.-R. M. Process Oriented Guided Inquiry Learning (POGIL®) Marginally Effects Student Achievement Measures but Substantially Increases the Odds of Passing a Course. PLoS One 2017, 12 (10), e0186203; https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0186203.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

36. Abebe, W.; Woldehanna, T. Teacher Training and Development in Ethiopia: Improving Education Quality by Developing Teacher Skills, Attitudes and Work Conditions. Young Lives 2013, 1–23. https://ora.ox.ac.uk/objects/uuid:7e88bc5a-993f-43fd-89fa-5ab3098b6148/files/mf552d2c99d5e542366b57566f0570f16 (accessed 2024-3-16).Suche in Google Scholar

37. Moog, R. S.; Spencer, J. N. POGIL: An overview. In Process-Oriented Guided Inquiry Learning (POGIL), 1st ed.; American Chemical Society: Washington, DC, Vol. 994, 2008; pp 1–13.10.1021/bk-2008-0994.ch001Suche in Google Scholar

38. Taber, K. S. The use of Cronbach’s Alpha when Developing and Reporting Research Instruments in Science Education. Res. Sci. Educ. 2018, 48, 1273–1296; https://doi.org/10.1007/s11165-016-9602-2.Suche in Google Scholar

39. Eagly, A. H.; Chaiken, S. The Advantages of an Inclusive Definition of Attitude. Soc. Cogn. 2007, 25 (5), 582–602; https://doi.org/10.1521/soco.2007.25.5.582.Suche in Google Scholar

40. Vincent-Ruz, P.; Meyer, T.; Roe, S. G.; Schunn, C. D. Short-Term and Long-Term Effects of POGIL in a Large-Enrollment General Chemistry Course. J. Chem. Educ. 2020, 97 (5), 1228–1238; https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.jchemed.9b01052.Suche in Google Scholar

41. Cascolan, H. M. S. Students’ Conceptual Understanding, Metacognitive Awareness and Self-Regulated Learning Strategies Towards Chemistry Using POGIL Approach. ASEAN Multidiscip. Res. J. 2019, 1 (1).Suche in Google Scholar

42. Cohen, J. The t Test for Means. In Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences, 2nd ed.; Routledge: New York, 2013.Suche in Google Scholar

43. Boda, P.; Weiser, G. Using POGILs and Blended Learning to Challenge Preconceptions of Student Ability in Introductory Chemistry. J. Coll. Sci. Teach. 2018, 48 (1), 60–67; https://doi.org/10.2505/4/jcst18_048_01_60.Suche in Google Scholar

44. Mundy, C.; Potgieter, M. Refining Process-Oriented Guided Inquiry Learning for Chemistry Students in an Academic Development Programme. Afr. J. Res. Math. Sci. Technol. Educ. 2019, 23 (2), 145–156; https://doi.org/10.1080/18117295.2019.1622223.Suche in Google Scholar

45. Bandura, A. Social Foundations of Thought and Action, Vol. 1986; NJ: Englewood Cliffs, 1986; pp. 23–28.Suche in Google Scholar

46. Vishnumolakala, V. R.; Southam, D. C.; Treagust, D. F.; Mocerino, M.; Qureshi, S. Students’ Attitudes, Self-Efficacy and Experiences in a Modified Process-Oriented Guided Inquiry Learning Undergraduate Chemistry Classroom. Chem. Educ. Res. Pract. 2017, 18 (2), 340–352; https://doi.org/10.1039/C6RP00233A.Suche in Google Scholar

47. De Gale, S.; Boisselle, L. N. The Effect of POGIL on Academic Performance and Academic Confidence. Sci. Educ. Int. 2015, 26 (1), 56–79. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ1056455.pdf.Suche in Google Scholar

48. Yalcinkaya, E.; Boz, Y.; Erdur-Baker, O. Is Case-Based Instruction Effective in Enhancing High School Students’ Motivation Toward Chemistry? Sci. Educ. Int. 2012, 23 (2), 102–116.Suche in Google Scholar

49. Qureshi, S.; Vishnumolakala, V. R.; Southam, D. C.; Treagust, D. F. Inquiry-Based Chemistry Education in a High-Context Culture: A Qatari Case Study. Int. J. Sci. Math. Educ. 2017, 15, 1017–1038; https://doi.org/10.1007/s10763-016-9735-9.Suche in Google Scholar

50. Al Neyadi, S. Assessing the Effects of POGIL-Based Instruction Versus Lecture-Based Instruction on Grade 12 Self-Efficacy and Performance in Circular Motion Unit. J. Ecohumanism 2024, 3 (3), 1219–1238; https://doi.org/10.62754/joe.v3i3.3625.Suche in Google Scholar

51. Lotlikar, P. C.; Wagh, R. Using Pogil to Teach and Learn Design Patterns–A Constructionist Based Incremental, Collaborative Approach. In 2016 IEEE Eighth International Conference on Technology for Education (T4E); IEEE: Mumbai, India, 2016; pp. 46–49.10.1109/T4E.2016.018Suche in Google Scholar

52. Reynders, G.; Ruder, S. M. Moving a Large-Lecture Organic POGIL Classroom to an Online Setting. J. Chem. Educ. 2020, 97 (9), 3182–3187; https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.jchemed.0c00615.Suche in Google Scholar

53. Childs, P. E.; Markic, S.; Ryan, M. C. The role of Language in the Teaching and Learning of Chemistry. Chem. Educ.: Best Pract. Opportun. Trends 2015, 421–446; https://doi.org/10.1002/9783527679300.ch17.Suche in Google Scholar

54. Cascolan, H. M. S. Exploring students’ Academic Performance, Motivational Orientation and Self-Regulated Learning Strategies Towards Chemistry. Int. J. STEM Education Sustainability 2023, 3 (2), 225–239; https://doi.org/10.53889/ijses.v3i2.215.Suche in Google Scholar

55. Yuliastini, I.; Rahayu, S.; Fajaroh, F.; Mansour, N. Effectiveness of POGIL with SSI Context on Vocational High School Students’ Chemistry Learning Motivation. Jurnal Pendidikan IPA Indonesia 2018, 7 (1), 85–95; https://doi.org/10.15294/jpii.v7i1.9928.Suche in Google Scholar

56. Beck, J. P.; Miller, D. M. Encouraging Student Engagement by Using a POGIL Framework for a Gas-Phase IR Physical Chemistry Laboratory Experiment. J. Chem. Educ. 2022, 99 (12), 4079–4084; https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.jchemed.2c00314.Suche in Google Scholar

57. Purnama, R. G.; Rahayu, S. The Role of Process Oriented Guided Inquiry Learning (POGIL) and its Potential to Improve Students’ Metacognitive Ability: A Systematic Review. In AIP Conference Proceedings. The 5th International Conference on Mathematics and Science Education (ICoMSE) 2021: Science and Mathematics Education Research: Current Challenges and Opportunities, 3–4 August 2021; AIP Publishing: Malang, Indonesia, Vol. 2569, 2023; https://doi.org/10.1063/5.0113476.Suche in Google Scholar

58. Muntholib, M.; Anggraeni, D. P.; Zaroh, I.; Utomo, Y.; Yahmin, Y. The Effect of POGIL Instruction on Students’ Chemical Literacy in Electrolyte and Nonelectrolyte Solution. In AIP Conference Proceedings; AIP Publishing: Malang, Indonesia, Vol. 2569, 2023; https://doi.org/10.1063/5.0112761.Suche in Google Scholar

59. Santoso, A.; Sumari, S.; Setiadi, A. D. The Effect of POGIL Classroom on Students’ Achievement and Motivation on acid-Base Topics. In AIP Conference Proceedings. The 5th International Conference on Mathematics and Science Education (ICoMSE) 2021: Science and Mathematics Education Research: Current Challenges and Opportunities, 3–4 August 2021; AIP Publishing: Malang, Indonesia, Vol. 2569, 2023; https://doi.org/10.1063/5.0112292.Suche in Google Scholar

60. Stanford, C.; Moon, A.; Towns, M.; Cole, R. Analysis of Instructor Facilitation Strategies and their Influences on Student Argumentation: A Case Study of a Process Oriented Guided Inquiry Learning Physical Chemistry Classroom. J. Chem. Educ. 2016, 93 (9), 1501–1513; https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.jchemed.5b00993.Suche in Google Scholar

61. Douglas, E. P.; Chiu, C.-C. Process-Oriented Guided Inquiry Learning In Engineering. Proced. Soc. Behav. Sci. 2012, 56, 253–257; https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2012.09.652.Suche in Google Scholar

62. Aiman, U.; Hasyda, S.; Uslan, U. The Influence of Process Oriented Guided Inquiry Learning (POGIL) Model Assisted by Realia Media to Improve Scientific Literacy and Critical Thinking Skill of Primary School Students. Eur. J. Educ. Res. 2020, 9 (4), 1635–1647; https://doi.org/10.12973/eu-jer.9.4.1635.Suche in Google Scholar

63. Gao, Q.; Tong, M.; Sun, J.; Zhang, C.; Huang, Y.; Zhang, S. A Study of Process-Oriented Guided Inquiry Learning (POGIL) in the Blended Synchronous Science Classroom. J. Sci. Educ. Technol. 2024, 34, 103–121; https://doi.org/10.1007/s10956-024-10155-3.Suche in Google Scholar

64. Bailey, C. P.; Minderhout, V.; Loertscher, J. Learning Transferable Skills in Large Lecture Halls: Implementing a POGIL Approach in Biochemistry. Biochem. Mol. Biol. Educ. 2012, 40 (1), 1–7; https://doi.org/10.1002/bmb.20556.Suche in Google Scholar

65. Treagust, D. F.; Qureshi, S. S.; Vishnumolakala, V. R.; Ojeil, J.; Mocerino, M.; Southam, D. C. Process-Oriented Guided Inquiry Learning (POGIL) as a Culturally Relevant Pedagogy (CRP) in Qatar: A Perspective from Grade 10 Chemistry Classes. Res. Sci. Educ. 2020, 50, 813–831; https://doi.org/10.1007/s11165-018-9712-0.Suche in Google Scholar

© 2025 the author(s), published by De Gruyter, Berlin/Boston

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Frontmatter

- Review Article

- Non-formal chemistry learning: a scoping review

- Research Article

- Discussion on definition and understanding of the thermodynamic spontaneous process

- Good Practice Report

- A molecular motion-based approach to entropy and application to phase transitions and colligative properties

- Research Articles

- Interrelationship of differential changes of thermodynamic potentials in a system in which a reaction takes place intending to obtain useful work in isentropic conditions–lectures adapted to sensing learners

- A role-playing tabletop game on laboratory techniques and chemical reactivity: a game-based learning approach to organic chemistry education

- Predominant strategies for integrating digital technologies in the training of future chemistry and biology teachers

- Enhancing conceptual teaching in organic chemistry through lesson study: a TSPCK-Based approach

- Enhancing chemistry understanding and attitudes through an outreach education program on circular plastic economy: a case study with Thai twelfth-grade students

- Process oriented guided inquiry learning: a possible solution to improve high school students’ conceptual understanding of electrochemistry and attitude

- Good Practice Report

- Portable syringe kit demonstration of gas generating reactions for upper secondary school chemistry

- Research Article

- Determination of total hardness of water sample by titration using double burette method: an economical approach

- Good Practice Reports

- Interpretation of galvanic series when teaching metal corrosion

- Synthesis of valproic acid for medicinal chemistry practical classes

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Frontmatter

- Review Article

- Non-formal chemistry learning: a scoping review

- Research Article

- Discussion on definition and understanding of the thermodynamic spontaneous process

- Good Practice Report

- A molecular motion-based approach to entropy and application to phase transitions and colligative properties

- Research Articles

- Interrelationship of differential changes of thermodynamic potentials in a system in which a reaction takes place intending to obtain useful work in isentropic conditions–lectures adapted to sensing learners

- A role-playing tabletop game on laboratory techniques and chemical reactivity: a game-based learning approach to organic chemistry education

- Predominant strategies for integrating digital technologies in the training of future chemistry and biology teachers

- Enhancing conceptual teaching in organic chemistry through lesson study: a TSPCK-Based approach

- Enhancing chemistry understanding and attitudes through an outreach education program on circular plastic economy: a case study with Thai twelfth-grade students

- Process oriented guided inquiry learning: a possible solution to improve high school students’ conceptual understanding of electrochemistry and attitude

- Good Practice Report

- Portable syringe kit demonstration of gas generating reactions for upper secondary school chemistry

- Research Article

- Determination of total hardness of water sample by titration using double burette method: an economical approach

- Good Practice Reports

- Interpretation of galvanic series when teaching metal corrosion

- Synthesis of valproic acid for medicinal chemistry practical classes