Abstract

Background

Mechanistic, translational, human experimental pain assessment technologies (pain bio markers) can be used for: (1) profiling the responsiveness of various pain mechanisms and pathways in healthy volunteers and pain patients, and (2) profiling the effect of new or existing analgesic drugs or pain management procedures. Translational models, which may link mechanisms in animals to humans, are important to understand pain mechanisms involved in pain patients and as tools for drug development. This is urgently needed as many drugs which are effective in animal models fail to be efficient in patients as neither the mechanisms involved in patients nor the drugs’ mechanistic actions are known.

Aim

The aim of the present topical review is to provide the basis for how to use mechanistic human experimental pain assessment tools (pain bio markers) in the development of new analgesics and to characterise and diagnose pain patients. The future aim will be to develop such approaches into individualised pain management regimes.

Method

Experimental pain bio markers can tease out mechanistically which pain pathways and mechanisms are modulated in a given patient, and how a given compound modulates them. In addition, pain bio markers may be used to assess pain from different structures (skin, muscle and viscera) and provoke semi-pathophysiological conditions (e.g. hyperalgesia, allodynia and after-sensation) in healthy volunteers using surrogate pain models.

Results

With this multi-modal, multi-tissue, multi-mechanism pain assessment regime approach, new opportunities have emerged for profiling pain patients and optimising drug development. In this context these technologies may help to validate targets (proof-of-concept), provide dose-response relationships, predicting which patient population/characteristics will respond to a given treatment (individualised pain management), and hence provide better understanding of the underlying cause for responders versus non-responders to a given treatment.

Conclusion

In recent years, pain bio markers have been substantially developed to have now a role to play in early drug development, providing valuable mechanistic understanding of the drug action and used to characterise/profile pain patients. In drug development phase I safety volunteer studies, pain bio marker scan provide indication of efficacy and later if feasible be included in clinical phase II, III, and IV studies to substantiate mode-of-action.

Implications

Refining and optimizing the drug development process ensures a higher success rate, i.e. not discarding drugs that may be efficient and not push non-efficient drugs too far in the costly development process. Mechanism-based pain bio markers can help to qualify the development programmes and at the same time help qualifying them by pain profiling (phenotyping) and recognising the right patients for specific trials. The success rate from preclinical data to clinical outcome may be further facilitated by using specific translational pain bio-markers. As human pain bio markers are getting more and more advanced it could be expected that FDA and EMA in the future will pay more attention to such mechanism-related measures in the approval phase as proof-of-action.

1 Introduction

Development of new drugs for pain is a major challenge as the costs for developing new compounds steadily increase, and the number of new analgesics approved is very low. Different regulatory bodies (FDA, EMA) use different strategies for approving pain compounds, which further complicates approval where, e.g. milnacipran and duloxetine are approved for fibromyalgia in US, but failed to be approved in Europe. Furthermore, it is clinically recognised that patients with fundamentally the same pain conditions may respond differently to various drugs most likely because different mechanisms are involved. Today limited success has been made in relating a symptom/mechanism (e.g. tactile allodynia) to drug effects of a given treatment in a given pain condition (e.g. painful diabetic neuropathy). Even though comprehensive sensory test protocols of specific sensory profiles have been developed (e.g. from the German Neuropathic Pain Network), it has not been possible to link sensory abnormalities with response to drugs in neuropathic pain [1]. This has not been investigated in detail for musculoskeletal and visceral pain conditions.

There is still substantial need to find more efficient ways in linking patients’ profile with drug mode of action, but to further develop and implement such an idea, new analgesics are needed.

Optimising the drug development process and implementing new drugs in individualised pain management regimes by mechanistic profiling are, therefore, the path to follow in future. This paper will address the concept of an advanced pain profiling using translational, mechanism-based human pain bio markers for profiling/characterisation of pain patients (Fig. 1) and for mechanistic profiling of drugs in early development.

Approximately 19% of the adult population in Europe suffers from chronic pain, and 2/3 of those suffer from musculoskeletal pain (e.g. back pain and osteoarthritis) [2]. The knowledge related to the neurobiology of the pain system has exploded over the last 20 years, resulting in massive investments in developing new analgesics. A significant number of compounds are in the pipeline of various companies as many new targets have been discovered.

There has been a tendency to develop centrally acting compounds targeting one very specific receptor (e.g. NK1), but this strategy seems to have failed as a broader mode of action seems important (“polypharmacy”), and in addition CNS drugs often cause side effects which disqualify them at an early stage.

Therefore, the tendency is currently to look for more selective peripherally acting compounds as this dramatically reduces the chances for adverse effects, but it poses the problem of reaching sufficient levels of drugs at the peripheral receptor site. Unfortunately a very limited number of new compounds have been introduced to the market in recent years, and some were removed again due to serious adverse effects (e.g. COX-II inhibitors), and other very efficient drugs (e.g. anti-NGF compound tanezumap) have not made it in the large phase III trials again due to some unexplained adverse effects. The latter, however, seems to be on its way back into larger trials as co-administration of NSAIDs retrospectively was found to be an important factor for driving the side effects (accelerated osteonecrosis, avascular necrosis).

2 Translational research

In the preclinical phase of drug development, there are many confounding factors contributing to such variations, e.g. pain models, strains, breeding place, food, and laboratory conditions [3, 4]. Kontinen and Meert [5] evaluated the predictive validity of four peripheral nerve injury models across more than 100 studies and concluded that the predictive sensitivity of these models ranged from 61% to 88%, with unclear or relatively low specificity.

For musculoskeletal conditions (e.g. osteoarthrosis (OA)), the predictability is most likely even lower. This lack of efficient translation between animal and human findings in drug effects is a main hurdle for efficient drug development [6, 7], and the current practice is to move as fast into small human proof-of-concept studies as possible to avoid spending too much time and money on preclinical studies not really contributing to the success of the development programme.

Lack of efficacy is the reason for 51% of phase II trial failures [8] although in rational drug development it can be expected that preclinical data had showed significant effect in various preclinical models. Developing translational and predictable pain models to act as a bridge between animal and clinical research could significantly enhance the rate of success in the development of new analgesics [9].

Moving from animal into patients adds a lot of new variables. Many factors can affect the outcome of a clinical drug study such as comorbidities, psycho-social factors, unknown aetiology of pain, fluctuations in pain, and general malaise. Furthermore, often the actual pain level of a chronic condition in an individual patient does not correlate with what is expected to be the severity of the clinical condition, e.g. joint damage, size of peptic ulcer, nerve damage, level and expansion of inflammation. This clearly shows that other factors such as reorganisation and sensitisation of the pain system may also be involved. Further, the area is complicated by the fact that the pain system can also show abnormal reaction in patient populations not even suffering from chronic pain (e.g. borderline personality disorders, major depression, and schizophrenia). Pain in individuals with cognitive impairment is another challenging area (e.g. dementia, elderly, and individuals with cognitive disabilities) where little is known as to what is happening within the pain system and how the patients do react to analgesics.

In more recent years regulatory authorities have pushed a focus on pain management in children, as companies have to prepare post-marketing paediatric plans when new compounds are introduced to the marked. However, this will in future require better understanding of how the pain system in children with pain may reorganise (e.g. sensitisation) compared with in adults.

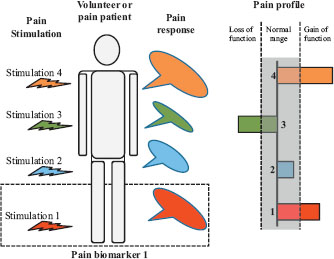

A theoretical sketch showing how a volunteer or patient is stimulated by various pain stimuli activating different nociceptors, pathways, and/or mechanisms. The pain responses to the individual stimuli can then be assessed in a quantitative way. A stimulus together with the associated response is termed a mechanistic pain bio marker (illustrated by dotted line box). At sketch 4, pain bio markers are combined to the mechanistic pain profile of the person. The individual responses can then be inside or outside the normal range (shaded). If the response is outside the normal range, it can either show a loss of function (e.g. hypoalgesia) or gain of function (e.g. hyperalgesia).

3 New drugs and drugs in development

Five decades (1960-2009) of drug development for the treatment of pain indicate that the total number of drugs specifically developed as analgesics has been 39 in comparison with 20 drugs developed for non-pain indications, but effective in pain [10]. These compounds include, but are not limited to gabapentin/pregabalin, COX-II inhibitors, tapentadol, anti-NGF monoclonal antibodies (tanezumab), new alpha2delta subunit Ca2+ channel blockers, botulinum toxins, TRPV1-antagonists (at present, efficacy demonstrated only in volunteers), ziconotide, Nav 1.7 sodium channel blocker (volunteers), and a peripherally acting κ-receptor agonist (volunteers). However, despite good analgesic effects in a variety of animal models, many compounds have failed in human phase I and II clinical studies. As many negative data are not published, there are most likely far more than those known from the literature such as FAAH (fatty-acid amide hydrolase) inhibitors, NK1 antagonists, use-dependent Na channel blocker, glycine-site NMDA antagonist, mGluR5 antagonists, TRPV1-antagonists (patients), CGRP receptor antagonist, and 5-HT-antagonist [10].

During the past 30 years an explosion in basic pain research has occurred, identifying many new pain mechanisms leading to many new candidate compounds in development [11]. Search for “pain” on ClinicalTrials.gov reveals approximately 14, 000 human trials of which a large proportion is related to new and existing analgesics. Among the many new potential drug candidates are chemokine inhibitors, ORL-1 (opioid receptor-like receptor) agonists, pro-inflammatory cytokine inhibitors, potassium channel blockers, voltage-gated calcium/sodium channel blockers, cannabinoid receptor agonists, TRP channel antagonists, purinergic P2 receptor antagonists, muscarinic/nicotinic acetylcholine receptor antagonists, MAP kinase inhibitors, imidazoline receptor agonists, catecholamine modulators, cathepsin inhibitors, and modulation of vesicular exocytosis. Anti-IL6 agents (sarilumab) may be a new class of compounds targeting inflammatory pain conditions (e.g. rheumatoid arthritis).

Due to the lack of success in introducing new compounds to the marked, the industry is trying to identify new indications of existing compounds, reformulate existing compounds (e.g. slow release, topical administration) or combination of already existing drugs in new ways.

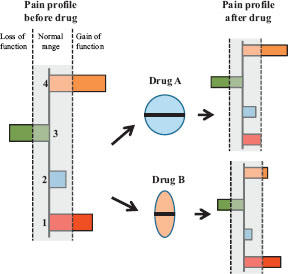

The mechanistic pain profile composed of 4 mechanistic pain bio markers characterises the pain patient. Two of the bio markers show gain of function, and one shows loss of function. The patients are then exposed to drug A and/or B. Drug A inhibits significantly the facilitated bio marker 1 response whereas drug B significantly inhibits the facilitated bio marker 4 response. Theoretically, combining drug A's mode-of-mechanism with drug B's mode-of-mechanism should cause an inhibition of the facilitated pain mechanisms indicating theoretically how individualised pain management regimes could be implemented. How such an approach would benefit patients needs to be proven for different classes of chronic pain disorders.

4 Experimental pain models in early drug development

The many pharmaceutical companies currently developing new analgesics have three basic needs to be fulfilled as early as possible in the drug development programme:

Speed: Minimising the time from preclinical development to market.

Efficacy: Investigating possible efficacy early in the development process and increasing value of early clinical trials (phases I and II) and suggesting optimal outcome variables.

Prediction: Early prediction of efficient doses and patient populations who will benefit from the drug in clinical trials.

For proof-of-mechanism evaluation, experimental pain models or human pain bio markers can be used as tools for characterising analgesic and antihyperalgesic action and help to qualify the above factors. Experimental pain stimuli (including the modality, activation pattern, localisation, intensity, frequency and duration of the pain stimulus) can be controlled, repeated over time, and quantitative mechanism-based pharmacodynamic measures are provided [12, 13] (Fig. 1). In addition opportunities exist to match a mode-of-action for a drug with a patient’s pain profile (Fig. 2) and hence start to implement individualised pain management regime [13, 14] although there is still a long way to go before such a strategy can be implemented.

It is evident that a chronic pain conditions can cause sensitisation as manifested by centrally mediated components such as allodynia, hyperalgesia, spreading sensitisation and spreading of pain [15]. Surrogate models mimicking such symptoms in healthy volunteers are likewise important in early drug development [16, 17] as they can act as a proxy for alternations in the peripheral or central neural apparatus in pain patients [18] and particularly in neuropathic pain [16].

Recent reviews have summarised how different pain bio markers have been used for drug profiling [13, 19, 20], and how psychophysical, electrophysiological, and imaging assessments of the evoked responses are used [12, 21, 22] (Fig. 2).

The German Neuropathic Pain Network test platform for quantitative sensory testing includes a variety of static and dynamic pain bio markers specifically designed to profile patients with neuropathic pain and associated sensitisation [23]. This platform mainly addresses cutaneous pain, and therefore other bio marker platforms are needed when patients with musculoskeletal or visceral pain are to be profiled [24] as not only the cutaneous manifestations in those patients are presented.

5 Added value of pain bio-markers in patient profiling and drug evaluation?

A recent review from a group of Pfizer researchers summarised the benefits from using predictive bio markers in drug development [25]. The analysis was performed on data from Phase II decisions for 44 programmes at Pfizer. Not only the majority of failures were found to be caused by lack of efficacy but it was also not possible to conclude whether the mechanism had been tested adequately in a large number of cases (43%). A key finding was that an integrated understanding of the fundamental mechanistic and pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic principles of exposure at the site of action, target binding, and expression of functional pharmacological activity determined the likelihood of candidate survival in phase II trials and improve the chance of progression to phase III.

As an example Morgan et al. referred particularly to Pfizers dopamine D3 receptor agonist (PF592379) programme for treating nociceptive pain. In rat in vivo models, the compound had positive effects on several different endpoints (e.g. pressure allodynia and hyperalgesia and weight deficit in the monosodium iodoacetate (MIA) osteoarthritis model). This suggested a therapeutic potential of dopamine agonists in the clinical treatment of nociceptive pain states such as osteoarthritis. A randomised, double-blind, placebo and active-controlled, crossover study was conducted in osteoarthritis, but no effect of the drug was found on pressure pain thresholds. It is known that dopamine receptors [26] may interact with the descending pain pathways, and hence it would have been of importance to include a bio marker of descending inhibition, [27] which is known to be impaired in patient with osteoarthritic pain [28]. A restoration of the impaired descending inhibition by the compound would have proved the mode-of action in that particular study.

Another example could be the development of TRPV1 antagonists as many companies are involved in developing such compounds and a number of experimental pain studies have been conducted [29]. A human volunteer study [30] investigated the effect of an experimental TRPV1 antagonist on heat pain thresholds, UVB-induced heat hyperalgesia, and on capsaicin-evoked neurogenic inflammation. The compound increased the heat pain threshold, increased heat pain tolerance in the UVB-evoked inflammatory area, and reduced the area of capsaicin-evoked flare. The magnitude of the pharmacodynamic effects was related to plasma concentration. These data strongly indicated that the compound might have analgesic efficacy and reduce hyperalgesia associated with inflammation. Many of the TRPV1 programmes have been terminated due to unwanted central side effects (hyperthermia), and no selective peripheral acting TRPV1 antagonist are yet in later clinical trials.

Pain bio markers and surrogate models can also be used to profile existing drugs, and an example is where pain models have been used to characterise and profile an existing toxin (botulinum toxin A), as this toxin has been suggested to exert analgesic effects in addition to muscle relaxation [31]. The toxin has also been found to inhibit central sensitisation in animal models [32]. Thus, the analgesic and anti hyperalgesic effects of botulinum toxin A were investigated in a human experimental volunteer study using capsaicin induced hyperalgesia and allodynia (surrogate model). Toxin pre-treatment induced a significantly long lasting anti-hyperexcitability inhibition together with analgesic effects on phasic pain stimuli and hence opening up new applications of this drug in the area of pain [33, 34].

Experimental studies have also been able to identify different actions of existing opioids where for example oxycodone has been shown to have a superior effect on visceral pain as compared with musculoskeletal pain possibly due to a kappa-agonistic effect [35] and opening up for new applications in chronic visceral pain [36]. Buprenorphine – as another opioid – has been shown to be more antihyperalgesic as compared with, e.g. fentanyl [37] in human surrogate models of hyperalgesia.

Koivisto and Pertovaara’s pain research groups have documented that blocking TRPA1 not only attenuates mechanical hypersensitivity in diabetes but also attenuates loss of axon reflexfunction and loss of peptidergic nerve endings in diabetes [38]. Thus, research into analgesics and antihyperalgesics with blockers of TRPA1 also promises to provide disease-modifying treatment of peripheral diabetic neuropathy [38, 39].

Finally, the recently established and by pain journal-editors accepted guidelines for reporting analgesic trials in animals, the ARRIVE-guidelines, promise to have a major impact on quality of design, planning, execution, and reporting of pain and analgesic research in animals, similar to what the CONSORT-guidelines did for clinical analgesic trials [40, 41].

6 Conclusion

The field of human pain bio markers has advanced significantly over the last 10-15 years, and many tools have been developed. Today it is possible to apply those pain bio markers to profile sensory abnormalities in pain patients and to provide proof for action mechanism of existing or new analgesics and anti-inflammatory drugs. Refining and optimising bio marker test platforms for different pain categories (neuropathic, musculoskeletal, and visceral) are needed. Future research focus should be on matching patients’ sensory profile with drug effects in order to pave the way for more personalised and individualised pain management and for more efficient development of new compounds. Utilising translational pain bio marker may further increase the success rate from preclinical data to clinical outcome of new drugs to the benefit of many pain patients.

Highlights

Human experimental pain models can use specific pain mechanism and specific drug actions.

Pain bio markers can indicate pain-mechanisms involved and how analgesics modulate pain.

Pain bio markers can assess pain from different tissues.

Multi-modal, multi-tissue, multi-mechanism pain assessment approaches can better individualise treatment and improve analgesic drug development.

DOI of refers to article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.sjpain.2013.07.025

-

Conflict of interest:No conflicts of interest to declare.

Acknowledgement

The author thanks Danish National Advanced Technology Foundation for their support.

References

[1] Sindrup SH, Finnerup NB, Jensen TS. Tailored treatment of peripheral neuropathic pain. Pain 2012;153:1781-2.Suche in Google Scholar

[2] Breivik H, Collett B, Ventafridda V, Cohen R, Gallacher D. Survey of chronic pain in Europe: prevalence, impact on daily life, and treatment. Eur J Pain 2006;10:287-333.Suche in Google Scholar

[3] Robinson I, Dowdall T, Meert TF. Development of neuropathic pain is affected by bedding texture in two models of peripheral nerve injury in rats. Neurosci Lett 2004;368:107-11.Suche in Google Scholar

[4] Christoph T, Kogel B, Schiene K, Mèen M, De Vry J, Friderichs E. Broad analgesic profile of buprenorphine in rodent models of acute and chronic pain. Eur J Pharmacol 2005;507:87-98.Suche in Google Scholar

[5] Kontinen VK, Meert TF. Predictive validityof neuropathic pain models in pharmacological studies with a behavioral outcome in the rat: a systematic review. In: Dostrovsky J, Carr DB, Koltzenburg M, editors. 10th World Congress on Pain. San Diego: IASP Press; 2003. p. 489-98.Suche in Google Scholar

[6] Quessy SN. The challenges of translational research foranalgesics: the state of knowledge needs upgrading and some uncomfortable deficiencies remain to be urgently addressed. J Pain 2010;11:698-700.Suche in Google Scholar

[7] Mao J. Translational pain research: achievements and challenges. J Pain 2009;10:1001-11.Suche in Google Scholar

[8] Arrowsmith J. Trial watch: phase II failures: 2008-2010. Nat Rev Drug Discov 2011;10:328-9.Suche in Google Scholar

[9] Rice AS, Cimino-Brown D, Eisenach JC, Kontinen VK, Lacroix-Fralish ML, Machin I. Animal models and the prediction of efficacy in clinical trials of analgesic drugs: a critical appraisal and call for uniform reporting standards. Pain 2008;139:243-7.Suche in Google Scholar

[10] Kissin I. The development of new analgesics over the past 50 years: a lack of real breakthrough drugs. Anesth Analg 2010;110:780-9.Suche in Google Scholar

[11] Dray A. Neuropathic pain: emerging treatments. Br J Anaesth 2008;101:48-58.Suche in Google Scholar

[12] Arendt-Nielsen L, Yarnitsky D. Experimental and clinical applications of quantitative sensory testing applied to skin, muscles and viscera. J Pain 2009;10:556-72.Suche in Google Scholar

[13] Arendt-Nielsen L, Hoeck HC. Optimizing the early phase development of new analgesics by human pain bio markers. Expert Rev Neurother 2011;11:1631-51.Suche in Google Scholar

[14] Woolf CJ. Overcoming obstacles to developing new analgesics. Nat Med 2010;16:1241-7.Suche in Google Scholar

[15] Graven-Nielsen T, Arendt-Nielsen L. Assessment of mechanisms in localized and widespread musculoskeletal pain. Nat Rev Rheumatol 2010;6:599-606.Suche in Google Scholar

[16] Klein T, Magerl W, Rolke R. Human surrogate models of neuropathic pain. Pain 2005;115:227-33.Suche in Google Scholar

[17] Fimer I, Klein T, Magerl W. Modality-specific somatosensory changes in a human surrogate model of postoperative pain. Anesthesiology 2011;115:387-97.Suche in Google Scholar

[18] Sandkuhler J. Models and mechanisms of hyperalgesia and allodynia. Physiol Rev 2009;89:707-58.Suche in Google Scholar

[19] Staahl C, Olesen AE, Andresen T, Arendt-Nielsen L, Drewes AM. Assessing efficacy of non-opioid analgesics in experimental pain models in healthy volunteers: an updated review. Br J Clin Pharmacol 2009;68:322-41.Suche in Google Scholar

[20] Staahl C, Olesen AE, Andresen T, Arendt-Nielsen L, Drewes AM. Assessing analgesic actions of opioids by experimental pain models in healthy volunteers – an updated review. Br J Clin Pharmacol 2009;68:149-68.Suche in Google Scholar

[21] Brock C, Arendt-Nielsen L, Wilder-Smith O, Drewes AM. Sensory testing ofthe human gastrointestinal tract. World J Gastroenterol 2009;15:151-9.Suche in Google Scholar

[22] Wise RG, Tracey I. The role of fMRI in drug discovery. J Magn Reson Imaging 2006;23:862-76.Suche in Google Scholar

[23] Maier C, Baron R, Tölle TR, Binder A, Birbaumer N, Birklein F, Gierthmühlen J, Flor H, Geber C, Huge V, Krumova EK, Landwehrmeyer GB, Magerl W, Maihöfner C, Richter H, Rolke R, Scherens A, Schwarz A, Sommer C, Tronnier V, Uçeyler N, Valet M, Wasner G, Treede RD. Quantitative sensory testing in the German Research Network on Neuropathic Pain (DFNS): somatosensory abnormalities in 1236 patients with different neuropathic pain syndromes. Pain 2010;150:439-50.Suche in Google Scholar

[24] Arendt-Nielsen L, Graven-Nielsen T. Translational musculoskeletal pain research. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol 2011;25:209-26.Suche in Google Scholar

[25] Morgan P, Van Der Graaf PH, Arrowsmith J, Feltner DE, Drummond KS, Wegner CD, Street SD. Can the flow of medicines be improved? Fundamental pharmacokinetic and pharmacological principles toward improving Phase II survival. Drug Discov Today 2012;17:419-24.Suche in Google Scholar

[26] Wei H, Viisanen H, Pertovaara A. Descending modulation of neuropathic hyper sensitivity by dopamine D2 receptors in or adjacent to the hypothalamic A11 cell group. Pharmacol Res 2009;59:355-63.Suche in Google Scholar

[27] Oono Y, Nie H, Matos RVL, Wang K, Arendt-Nielsen L. The inter-and intra-individual variance in descending pain modulation evoked by different conditioning stimuli in healthy men. Scand J Pain 2011;2:162-9.Suche in Google Scholar

[28] Arendt-Nielsen L, Nie H, Laursen MB, Laursen BS, Madeleine P, Simonsen OH, Graven-Nielsen T. Sensitization in patients with painful knee osteoarthritis. Pain 2010;149:573-81.Suche in Google Scholar

[29] Chizh BA, Sang CN. Use of sensory methods for detecting target engagement in clinical trials of new analgesics. Neurotherapeutics 2009;6:749-54.Suche in Google Scholar

[30] Chizh BA, O'Donnell MB, Napolitano A, Wang J, Brooke AC, Aylott MC, Bull-man JN, Gray EJ, Lai RY, Williams PM, Appleby JM. The effects of the TRPV1 antagonist SB-705498 on TRPV1 receptor-mediated activity and inflammatory hyperalgesia in humans. Pain 2007;132:132-41.Suche in Google Scholar

[31] Freund B, Schwartz M. Temporal relationship of muscle weakness and pain reduction in subjects treated with botulinum toxin A. J Pain 2003;4:159-65.Suche in Google Scholar

[32] Bach-Rojecky L, Relja M, Lackovic Z. Botulinum toxin type A in experimental neuropathic pain. J Neural Transm 2005;112:215-9.Suche in Google Scholar

[33] Gazerani P, Staahl C, Drewes AM, Arendt-Nielsen L. The effects of Botulinum Toxin type A on capsaicin-evoked pain, flare, and secondary hyperalgesia in an experimental human model of trigeminal sensitization. Pain 2006;122:315-25.Suche in Google Scholar

[34] Gazerani P, Pedersen NS, Staahl C, Drewes AM, Arendt-Nielsen L. Subcutaneous Botulinum toxin type A reduces capsaicin-induced trigeminal pain and vasomotor reactions in human skin. Pain 2009;141:60-9.Suche in Google Scholar

[35] Staahl C, Christrup LL, Andersen SD, Arendt-Nielsen L, Drewes AM. A comparative study of oxycodone and morphine in a multi-modal, tissue-differentiated experimental pain model. Pain 2006;123:28-36.Suche in Google Scholar

[36] Staahl C, Dimcevski G, Andersen SD, Thorsgaard N, Christrup LL, Arendt-Nielsen L, Drewes AM. Differential effect of opioids in patients with chronic pancreatitis: an experimental pain study. Scand J Gastroenterol 2007;42:383-90.Suche in Google Scholar

[37] Koppert W, Ihmsen H, Körber N, Wehrfritz A, Sittl R, Schmelz M, Schüttler J. Different profiles of buprenorphine-induced analgesia and antihyperalgesia in a human pain model. Pain 2005;118:15-22.Suche in Google Scholar

[38] Koivisto A, Pertovaara A. Transient receptor potential ankyrin 1 (TRPA1) ion channel inthe pathophysiology of peripheral diabetic neuropathy. Scand J Pain 2013;4:129-36.Suche in Google Scholar

[39] Jensen TS. New understanding of mechanisms of painful diabetic neuropathy: a pathto preventionand better treatment? Scand J Pain 2013;4:127-8.Suche in Google Scholar

[40] Rice ASC, Morland R, Huang W, Currie GL, Sena ES, Macleod MR. Transparency in the reporting of in vivo pre clinical pain research: the ARRIVE (Animal Research: Reporting In Vivo Experiments) guidelines. Scand J Pain 2013;4:58-62.Suche in Google Scholar

[41] Kontinen V. From clear reporting to better research models. Scand J Pain 2013;4:57.Suche in Google Scholar

© 2013 Scandinavian Association for the Study of Pain

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Editorial comment

- Chronic pain – The invisible disease? Not anymore!

- Clinical pain research

- New objective findings after whiplash injuries: High blood flow in painful cervical soft tissue: An ultrasound pilot study

- Editorial comment

- Chronic pain is strongly associated with work disability

- Observational studies

- Chronic pain: One year prevalence and associated characteristics (the HUNT pain study)

- Editorial comment

- Pain rehabilitation in general practice in rural areas? It works!

- Clinical pain research

- Effectiveness of multidisciplinary rehabilitation treatment for patients with chronic pain in a primary health care unit

- Editorial comment

- Mirror-therapy: An important tool in the management of Complex Regional Pain Syndrome (CRPS)

- Topical review

- Mirror therapy for Complex Regional Pain Syndrome (CRPS)—A literature review and an illustrative case report

- Editorial comment

- New insight in migraine pathogenesis: Vasoactive intestinal peptide (VIP) and pituitary adenylate cyclase-activating polypeptide (PACAP) in the circulation after sumatriptan

- Original experimental

- Vasoactive intestinal peptide (VIP) and pituitary adenylate cyclase-activating polypeptide (PACAP) in the circulation after sumatriptan

- Editorial comment

- Statistical pearls: Importance of effect-size, blinding, randomization, publication bias, and the overestimated p-values

- Topical review

- Significance tests in clinical research—Challenges and pitfalls

- Editorial comment

- Biomarkers of pain – Zemblanity?

- Topical review

- Mechanistic, translational, quantitative pain assessment tools in profiling of pain patients and for development of new analgesic compounds

- Editorial comment

- Chronic Benign Paroxysmal Positional Vertigo (BPPV): A possible cause of chronic, otherwise unexplained neck-pain, headache, and widespread pain and fatigue, which may respond positively to repeated particle repositioning manoeuvres (PRM)

- Observational studies

- Pain and other symptoms in patients with chronic benign paroxysmal positional vertigo (BPPV)

- Editorial comment

- The most important step forward in modern medicine, “a giant leap for mankind”: Insensibility to pain during surgery and painful procedures

- Topical review

- In praise of anesthesia: Two case studies of pain and suffering during major surgical procedures with and without anesthesia in the United States Civil War-1861–65

- Editorial comment

- Intravenous non-opioids for immediate postop pain relief in day-case programmes: Paracetamol (acetaminophen) and ketorolac are good choices reducing opioid needs and opioid side-effects

- Clinical pain research

- Intravenous acetaminophen vs. ketorolac for postoperative analgesia after ambulatory parathyroidectomy

- Editorial comment

- Scandinavian Association for the Study of Pain 2013—Annual scientific meeting abstracts of pain research presentations and greetings from incoming President

- Abstracts

- Why does the impact of multidisciplinary pain management on quality of life differ so much between chronic pain patients?

- Abstracts

- Health care utilization in chronic pain—A population based study

- Abstracts

- Pain treatment in rural Ghana—A qualitative study

- Abstracts

- Pain psychology specialist training 2012–2014

- Abstracts

- Pain assessment, documentation, and management in a university hospital

- Abstracts

- Promising effects of donepezil when added to patients treated with gabapentin for neuropathic pain

- Abstracts

- A pediatric patients’ pain evaluation in the emergency unit

- Abstracts

- Proteomic analysis of cerebrospinal fluid gives insight into the pain relief of spinal cord stimulation

- Abstracts

- The DQB1(*)03:02 HLA haplotype is associated with increased risk of chronic pain after inguinal hernia surgery and lumbar disc herniation

- Abstracts

- On the pharmacological effects of two lidocaine concentrations tested on spontaneous and evoked pain in human painful neuroma: A new clinical model of neuropathic pain

- Abstracts

- The mineralocorticoid receptor antagonist spironolactone enhances morphine antinociception

- Abstracts

- Expression of calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II in dorsal root ganglia in diabetic rats 6 months and 1 year after diabetes induction

- Abstracts

- Histamine in the locus coeruleus attenuates neuropathic hypersensitivity

- Abstracts

- Pronociceptive effects of a TRPA1 channel agonist methylglyoxal in healthy control and diabetic animals

- Abstracts

- Human inducible pluripotent stem cell-derived sensory neurons express multiple functional ion channels and GPCRs

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Editorial comment

- Chronic pain – The invisible disease? Not anymore!

- Clinical pain research

- New objective findings after whiplash injuries: High blood flow in painful cervical soft tissue: An ultrasound pilot study

- Editorial comment

- Chronic pain is strongly associated with work disability

- Observational studies

- Chronic pain: One year prevalence and associated characteristics (the HUNT pain study)

- Editorial comment

- Pain rehabilitation in general practice in rural areas? It works!

- Clinical pain research

- Effectiveness of multidisciplinary rehabilitation treatment for patients with chronic pain in a primary health care unit

- Editorial comment

- Mirror-therapy: An important tool in the management of Complex Regional Pain Syndrome (CRPS)

- Topical review

- Mirror therapy for Complex Regional Pain Syndrome (CRPS)—A literature review and an illustrative case report

- Editorial comment

- New insight in migraine pathogenesis: Vasoactive intestinal peptide (VIP) and pituitary adenylate cyclase-activating polypeptide (PACAP) in the circulation after sumatriptan

- Original experimental

- Vasoactive intestinal peptide (VIP) and pituitary adenylate cyclase-activating polypeptide (PACAP) in the circulation after sumatriptan

- Editorial comment

- Statistical pearls: Importance of effect-size, blinding, randomization, publication bias, and the overestimated p-values

- Topical review

- Significance tests in clinical research—Challenges and pitfalls

- Editorial comment

- Biomarkers of pain – Zemblanity?

- Topical review

- Mechanistic, translational, quantitative pain assessment tools in profiling of pain patients and for development of new analgesic compounds

- Editorial comment

- Chronic Benign Paroxysmal Positional Vertigo (BPPV): A possible cause of chronic, otherwise unexplained neck-pain, headache, and widespread pain and fatigue, which may respond positively to repeated particle repositioning manoeuvres (PRM)

- Observational studies

- Pain and other symptoms in patients with chronic benign paroxysmal positional vertigo (BPPV)

- Editorial comment

- The most important step forward in modern medicine, “a giant leap for mankind”: Insensibility to pain during surgery and painful procedures

- Topical review

- In praise of anesthesia: Two case studies of pain and suffering during major surgical procedures with and without anesthesia in the United States Civil War-1861–65

- Editorial comment

- Intravenous non-opioids for immediate postop pain relief in day-case programmes: Paracetamol (acetaminophen) and ketorolac are good choices reducing opioid needs and opioid side-effects

- Clinical pain research

- Intravenous acetaminophen vs. ketorolac for postoperative analgesia after ambulatory parathyroidectomy

- Editorial comment

- Scandinavian Association for the Study of Pain 2013—Annual scientific meeting abstracts of pain research presentations and greetings from incoming President

- Abstracts

- Why does the impact of multidisciplinary pain management on quality of life differ so much between chronic pain patients?

- Abstracts

- Health care utilization in chronic pain—A population based study

- Abstracts

- Pain treatment in rural Ghana—A qualitative study

- Abstracts

- Pain psychology specialist training 2012–2014

- Abstracts

- Pain assessment, documentation, and management in a university hospital

- Abstracts

- Promising effects of donepezil when added to patients treated with gabapentin for neuropathic pain

- Abstracts

- A pediatric patients’ pain evaluation in the emergency unit

- Abstracts

- Proteomic analysis of cerebrospinal fluid gives insight into the pain relief of spinal cord stimulation

- Abstracts

- The DQB1(*)03:02 HLA haplotype is associated with increased risk of chronic pain after inguinal hernia surgery and lumbar disc herniation

- Abstracts

- On the pharmacological effects of two lidocaine concentrations tested on spontaneous and evoked pain in human painful neuroma: A new clinical model of neuropathic pain

- Abstracts

- The mineralocorticoid receptor antagonist spironolactone enhances morphine antinociception

- Abstracts

- Expression of calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II in dorsal root ganglia in diabetic rats 6 months and 1 year after diabetes induction

- Abstracts

- Histamine in the locus coeruleus attenuates neuropathic hypersensitivity

- Abstracts

- Pronociceptive effects of a TRPA1 channel agonist methylglyoxal in healthy control and diabetic animals

- Abstracts

- Human inducible pluripotent stem cell-derived sensory neurons express multiple functional ion channels and GPCRs