ABSTRACT

Background

In recent years, multidisciplinary rehabilitation (MDR) became an alternative treatment option for chronic non-cancer pain. MDR is mostly available in specialized pain units, usually at rehabilitation centers where the level of knowledge and therapeutically options to treat pain conditions are considered to be high. There is strong evidence that MDR in specialized pain units is affecting pain and improves the quality of life in a sustainable manner. There are few studies about MDR outcome in primary health care, especially in those units situated in rural areas and with a different population than that encountered in specialized hospitals. That, in spite of the fact that the prevalence of pain in the patients treated in primary care practice is about 30%. The aim of this study is to analyze the effectiveness of MDR for chronic non-cancer patients in a primary health care unit.

Methods

This study included a total of 51 patients with chronic pain conditions who were admitted and completed the local MDR-program at the primary health care unit in Arvika, Sweden. The major complaint categories were fibromyalgia (53%), pain from neck and shoulder (28%) or low back pain (12%). The inclusion criteria were age between 16 and 67 years and chronic non-cancer pain with at least 3 months duration. The multidisciplinary team consisted of a general practitioner, two physiotherapists, two psychologists and one occupational therapist. The 6-week treatment took place in group sessions with 6-8 members each and included cognitive-behavioral treatment, education on pain physiology, ergonomics, physical exercises and relaxation techniques.

Primary outcomes included pain intensity, pain severity, anxiety and depression scores, social and physical activity, and secondary outcomes were sick leave, opioid consumption and health care utilization assessed in the beginning of the treatment and at one year follow-up. Data was taken from the Swedish Quality Register for Pain Rehabilitation (SQRP) and the patients’ medical journal.

Results

One year after MDR treatment, sick leave decreased from 75.6% to 61.5% (p <0.05). Utilization of health-care during one year decreased significantly from 27.4 to 20.1 contacts (p = 0.02). There were significant improvements concerning social activity (p = 0.03) and depression (p <0.05), but not in anxiety (p = 0.1) and physical activity (p = 0.08). Although not statistically significant, some numerical decrease in the mean levels of pain intensity, pain severity and opioid consumption were reported one year after MDR (p > 0.05).

Conclusions

The results obtained one year after rehabilitation indicated that patients with chronic noncancer pain might benefit from MDR in primary health care settings.

Implications

This study suggests that MDR in primary care settings as well as MDR at specialized pain units may lead to better coping in chronic non-cancer pain conditions with lower depression scores and higher social activity, leading to lower sick leave. This study demonstrated that there is a place for MDR in primary health care units with the given advantage of local intervention in rural areas allowing the patients to achieve rehabilitation in their home environment.

1 Introduction

Chronic non-cancer pain appears as a significant phenomenon and a public health problem in Scandinavia and other countries [1, 2, 3]. Breivik et al. investigated chronic pain in Europe and found that pain with moderate to severe intensity occurs in 19% of adult Europeans with a prevalence of 18% chronic pain among the general Swedish population [4]. A significant proportion of those affected have difficulty living with their pain which is affecting “their social and working lives” [4]. The prevalence of pain in the patients treated in primary care practice is about 30%. A little less than half of these patients received a prescription for analgesic drugs. The pain diagnoses at a primary care level showed a predominance of musculoskeletal pain [5].

Most research on treatment with multidisciplinary pain rehabilitation (MDR) has taken place in specialized expert level units, usually at rehabilitation centers where the level of knowledge and therapeutically options to treat pain conditions are considered to be high. There are few studies about MDR outcome in primary health care, especially in those units situated in rural areas and with a different population than that encountered in the university hospitals. For example, the distance from Arvika, a town of about 17,000 inhabitants situated in Värmland in the middle of Sweden, to the closest university clinic in Örebro is 150 km. To travel there several times a week or a month to access a rehabilitation program simply is not possible for many chronic pain patients. This is in spite of the well-known fact that chronic pain is a condition which is not limited to urban settings [6,7]. There are differences between urban and local programs when considering the main outcomes such as pain, pain intensity, physical or social activity and also important psychometric values such as depression and anxiety [8].

There is evidence that MDR of chronic pain, which today is mostly available in special pain units, affects the quality of life and sick-leave in a positive and sustainable manner [3,8]. However, there is not enough evidence to determine which patients should be treated in highly specialized units and which may be treated in primary care MDR-programs. In recent years, multidisciplinary rehabilitation (MDR) became an alternative treatment option for chronic pain [3,9, 10, 11]. It is considered that MDR improves the potential for patients to return to work [12], and reduces sick leave [13,14]. These benefits were mostly observed after multimodal rehabilitation treatment in patients with chronic back pain [15]. Evidence-based treatment with multimodal rehabilitation for patients with complex pain syndromes is still poorly studied.

The aim of the study was to determine if patients with chronic pain problems could benefit from multidisciplinary pain rehabilitation in primary health care units.

2 Methods

The MDR program at the local primary health care unit was developed according to the Swedish recommendations for rehabilitation of non-cancer pain patients [3]. The present study was conducted as a prospective controlled pragmatic trial [16]. This study was performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and the CONSORT Statement [17,18] and approved by the Regional Ethical Board.

2.1 Participants and study design

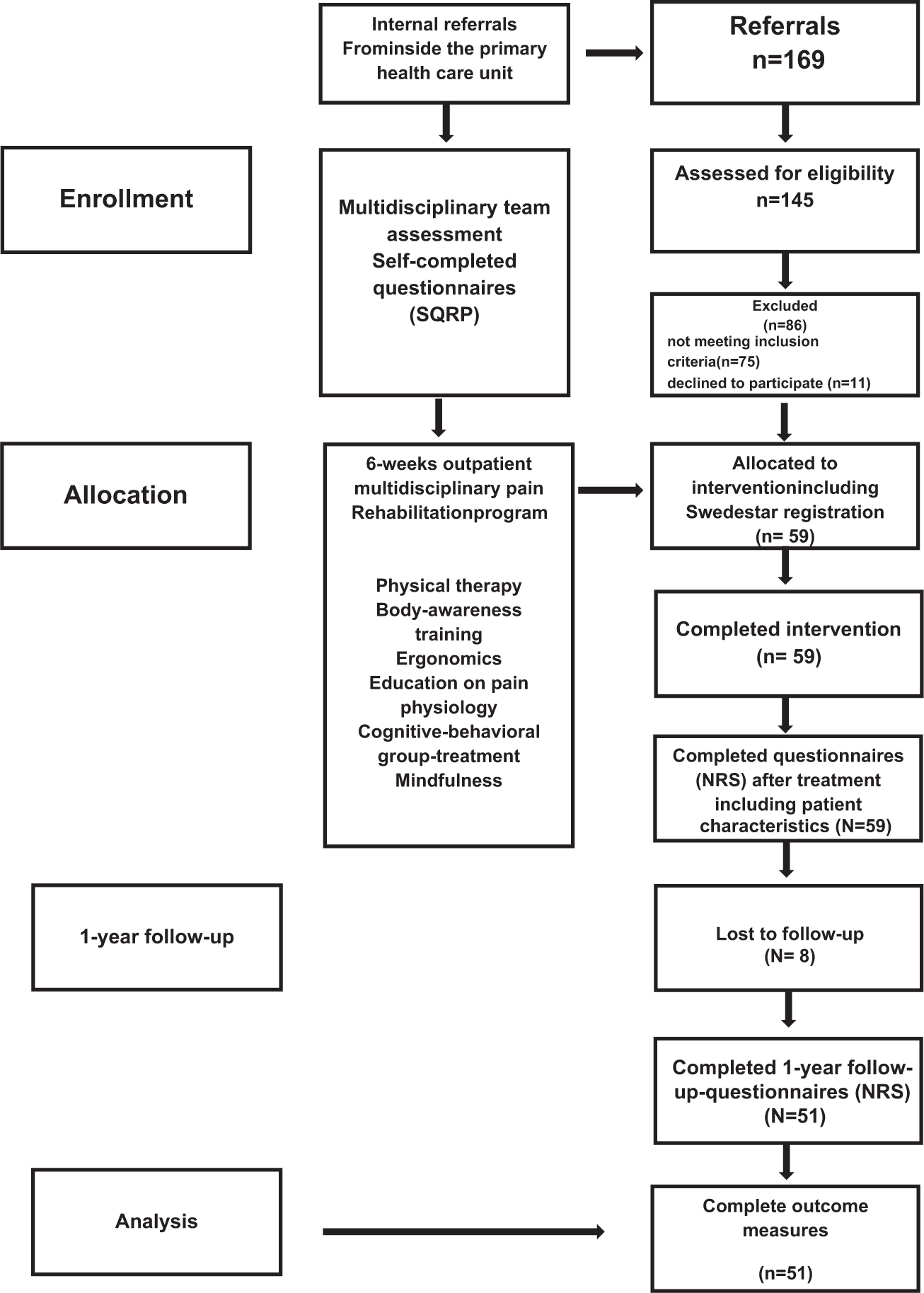

One hundred and sixty-nine patients were the potentially participants for rehabilitation’s program (Fig. 1). The inclusion criteria were age between 16 and 67 years and chronic non-cancer pain with at least 3 months duration. Pain was of musculoskeletal origin from the neck-shoulder region, low back pain or such generalized pain conditions as fibromyalgia. An important inclusion criterion was high motivation to life changes and to return to work after completing the multimodal rehabilitation. Exclusion criteria were ongoing medical treatment for the specific pain condition, psychiatric disease, drug abuse as well as use of opioids more than the equivalent of 40 mg oral morphine/day (Table 1). All assessed patients signed a consent form and underwent a complete multidisciplinary team evaluation with individual interviews and examination by all team members. The demographics, education, mean localization and duration of complaints, duration of sick leave at assessment, anxiety, depression, opioids consumption, social and physical activity were assessed before and one year after rehabilitation in all the patients.

The multidisciplinary team consisted of a general practitioner, two physiotherapists, two psychologists and one occupational therapist. All patients were examined clinically by the same GP. The interviews followed a structured and standardized protocol. The assessment took place at the pain unit which is located close to the primary health care unit. The mean assessment duration was about 2 weeks. Each examination protocol was accessible by the other team members. Then, a team meeting with all team members was held in order to discuss the findings. The special focus was on patients’ motivation to participate in treatment, biopsychosocial resources and their expectations concerning rehabilitation. The assessment ended with a team conference with the patient and in some cases with the patients together with family members. The team was represented by two or three members, avoiding a large group setting which was considered to be uncomfortable to many patients. There, all team findings were presented to the patient who was given the opportunity to ask questions concerning the evaluation or proposed treatment.

2.2 Interventions

The aim of treatment was not to reduce pain but to focus on patients’ quality of life, reduce their drug consumption and maintain or restore their capacity to work. The team was working multidisciplinarily and consisted of 2 cognitive-behavioral educated psychologists, one general practitioner with a special interest in pain rehabilitation, one medical secretary, an ergonomic therapist and 2 physiotherapists with special education in body-awareness and cognitive-behavioral therapy. It may be noted that no member of the team had special experience in pain treatment more than on the primary health care level. In Sweden, there is an ambition that all these professions should be available in all primary health care units throughout the country. The 6-week treatment took place in group sessions with 6–8 members each. The first patient group was started in November 2008. Up to August 2011 a total of 8 groups underwent treatment. In this way, all patients could receive MDR-treatment as outpatients while living at home, avoiding long travel. There was the possibility to have close contact with the responsible general practitioner as well as the local office of the Swedish Insurance Agency and the place of work. This model provided a unique link between patient’s rehabilitation on the one hand and every-day-life on the other hand.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria.

Inclusion criteria:

|

Exclusion criteria:

|

Flow diagram.

If the interdisciplinary team assessed the patient as qualified for MDR, he/she was included in the next program. The rehabilitation treatment was scheduled over 6 weeks which included 3 days of treatment with 5 h each day, interrupted by two free days a week (Table 2).

At the third week, a mid-program interview was held by one of the psychologists. During treatment, the participant was given the opportunity to have individual contacts with all team members. At the end of the MDR, the patient met all team members individually again for treatment follow-ups. The aim of these meetings was to encourage the patient to go back to work and to use the new skills in every-day-life. At this point, the referring GP, the local Swedish Insurance Agency and the employer were invited to attend to inform them about the treatment results. Before, at the end of program and one year after MDR program the patients filled in the questionnaires. The follow-up was done one year after the patient finished treatment.

2.3 Questionnaires

The pain unit in Arvika is linked to the Swedish Quality Registry for Pain Rehabilitation (SQRP). This registry was initiated by the Swedish Association for Rehabilitation Medicine in 1995 and has aggregated data since 1998. It compares all patients referred to the majority of Swedish MDR-units. The SQRP uses several validated, standardized self-reporting instruments for pain and its consequences such as the Multidimensional Pain Inventory (MPI), Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HAD) the EQ-5D and SF-36 Health Survey [19]. Furthermore, it collects demographic data such as age, sex and education level but also on diagnoses relevant to rehabilitation [20].

Pain intensity was assessed by the Numeric Rating Scale (NRS) with anchor points no pain = 0 and worst pain imaginable = 10. The Numeric Rating Scale is used as a self-reporting numeric scale where higher values indicate higher level of pain [21, 22, 23].

The Hospital and Anxiety Depression Scale (HAD) was developed by Zigmond and Snaith in 1983 for use with physically ill patients [24]. It measures symptoms of anxiety and depression on a scale from 0 to 21 points for each outcome. Zero to 7 points is regarded as no significant anxiety or depression, 8–10 points indicating possible signs for anxiety/depression and >10 points indicating moderate or severe anxiety or depression [25]. It gives clinically meaningful results as a psychological screening tool and is sensitive to changes both during the course of disease and in response to both psychotherapeutic and psychopharmacological intervention [26].

Components of the rehabilitation program (6 weeks).

General practitioner (12 h of education)

|

Ergonomics (18 h)

|

Physiotherapist (20 h)

|

Psychologist (28 h of cognitive behavioral-treatment)

|

Additional education (12 h) provided by

|

The Multidimensional Pain Inventory (MPI) is a pain-specific instrument. It was developed in 1985 by Kerns et al. [27] in order to increase reliability and validity in the assessment of chronic pain. The MPI is recommended for use in conjunction with behavioral and psychophysiological assessment strategies in the evaluation of chronic pain patients in clinical settings. It detects psychosocial and behavioral consequences of chronic pain using scales 0–6, value 0 indicating no problems and 6 severe problems. It consists of 12 subscales. The SQRP uses five subscales for pain severity, pain control, activity, impact of pain on daily life and emotional imbalance [28,29]. For this study, only the scale for pain severity was used.

The SF-36 on health-related quality of life was constructed to survey health status in clinical practice and research, health policy evaluations, and general population surveys. It consists of 36 questions grouped to eight scales and two indices [30,31]. The scales are social function, pain, health in general, vitality and others. For the present study, only the scale on social function was used. There is valid control data on the Swedish general population for this instrument [32]. Normal values for the Swedish population for different ages and sex has been presented [33].

The EQ-5D has been used to measure quality of life and health aspects in comparison to other instruments [34, 35, 36]. The EQ-5D seizes physical and psychosocial function. It consists of five dimensions, each on a scale with three values (1 =no problems; 2 = moderate problems; 3 = severe problems). In addition to this, it contains a health barometer with 101 values (0 = worst imaginable condition; 100 = best imaginable condition). The five dimensions are activity, mobility, personal hygiene, pain and depression. The measured values are transferred to an index which is correlated to a healthy population. There is recent evidence that the sensitivity for correlating of this index to the Swedish population is weak [37]. For this study, the EQ-5D was used because it has a long tradition in Sweden.

2.4 Outcomes

In the present study, data on sick-leave was taken directly from the medical doctor’s sick-leave journals for each patient. These documents were available from the software-system “Swedestar” used by all medical doctors at the primary health care unit at Arvika. No patient in the MDR group had been assessed by another doctor elsewhere concerning sick leave. Sick leave in Sweden is registered in percentages of sick leave at 100%, 75%, 50%, 25% or 0%. Data on health care utilization were taken also from Swedestar. Here, all types of contacts with the primary health care unit but also the local emergency unit at the local hospital during 12 months before the patients’ first assessment visit at the MDR-unit and 12 months after the program finished were compared for all single MDR-group patients. These contacts considered the number of visits to doctors and nurses as well as the number of prescriptions or telephone calls.

The consumption of analgesics and especially opioids was considered of special interest. The impact on rehabilitation regarding opioid prescription is often neglected or unclear. Therefore it was decided to use opioid consumption as a primary outcome for this trial. For this, Swedestar was used to assess all prescriptions for strong and weak opioids during the 12 months before the patient’s first assessment visit at the MDR-unit and compare them to the 12 months after the program finished for all single MDR-group patients. All opioid doses were transformed to a standardized oral opioid equivalent dose as used in the Swedish medicines information portal on the internet as published by the trade association for the research-based pharmaceutical industry in Sweden [38].

3 Statistics

GraphPad PRISM version 4.0 (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA) was used for handling and analyzing the data. Data are presented as either means ± SD or as median with ranges, 25% and 75% percentiles. The level of significance was set at a p value <0.05. This study was a descriptive observational study, thus no randomization or blinding was done. Non-parametric statistical methods were performed as follow: the chi-square test and the Mann-Whitney U test were used to test for differences in patient characteristics at admission and after 12 months. The independent-samples t-test was used to test for differences in the changes in pain intensity and the physical sub-scores of SF-36 scores at admission and at 12 months after.

4 Results

A total of 169 patients were referred to the local pain rehabilitation group at the health care pain unit Arvika. Eighty-six were excluded because at assessment that they did not fulfill the inclusion criteria (Table 1). Thus, the remaining 59 patients were admitted to the rehabilitation program and completed the routine questionnaires. All the 59 patients who started the MDR program finished it successfully, no one discontinued or withdrew before the end. After completing MDR the SQRP-questionnaires was answered by 59, at one-year follow-up by 51 patients. Patients’ characteristics are shown in Table 3. Most participants were female (86%, n = 44) and the mean age was 48 ± 7.8 years for both women and men. The major complaint category was generalized pain such as fibromyalgia (53%). Others were pain from neck and shoulder such as whiplash-trauma (28%) or low back pain (12%).

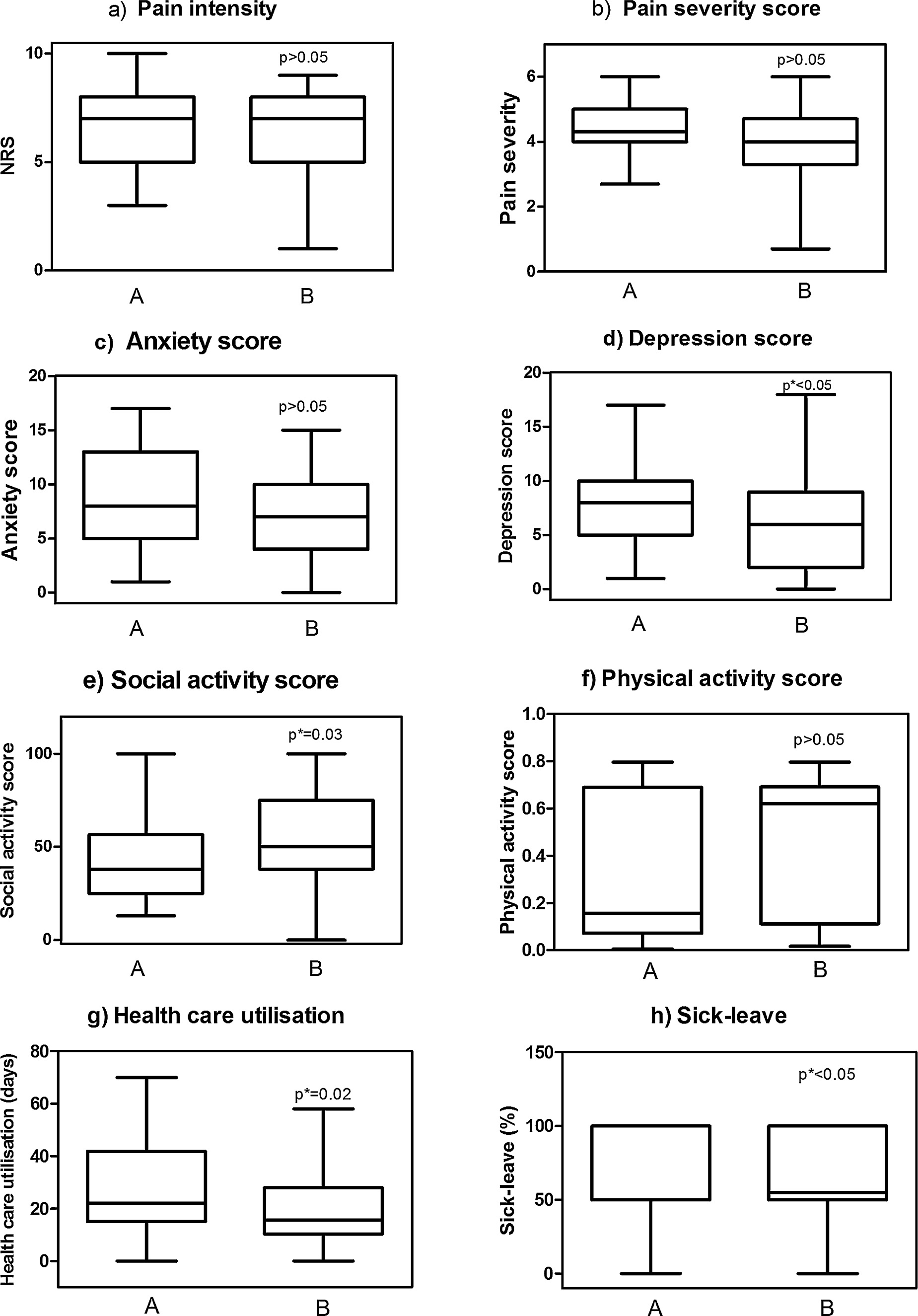

Results: A box-and-whisker plot indicating the smallest observation, lower quartile, median, upper quartile, and largest observation for (a) pain intensity, (b) pain severity, (c) anxiety score, (d) depression score, (e) social score, (f) physical activity score, (g) health care utilization, and (i) sick leave.

Baseline characteristics of the study population in comparison to the Swedish Quality Register of Pain Rehabilitation (SQRP) patients before treatment.

| Arvika Primary Care | SQRP | |

|---|---|---|

| Total number of subjects completing MDR including patient characteristics (Nov. 2008-Aug. 2011) | N = 51 | N = 4251 |

| Sex | ||

| Male | N = 7(14%) | N =1098(26%) |

| Female | N = 44(86%) | N = 3153(74%) |

| Mean age (years) ± SD | 48 ± 7.8 | 45 |

| Education higher than secondary school | N =10(20%) | N=1157 (27%) |

| Localization of complaints | ||

| Neck/shoulder | N =14(28%) | N =1063(25%) |

| Low back | N=6 (12%) | N =792(19%) |

| Generalized pain | N = 27 (53%) | N =1454 (34%) |

| Moderate/severe depression (HAD > 11) | 29% | 31% |

| Moderate/severe anxiety (HAD > 11) | 43% | 35% |

| Mean duration of complaints at assessment (days) | 4120 | 3040 |

| Mean duration of sick leave at assessment (days) | 2294 | 1731 |

The study results are presented in Fig. 2. Sick leave decreased from 75.6 ± 32% before MDR to 61.5 ± 36% at one-year follow-up (p<0.05). Mean health-care utilization decreased from 27.4 ± 7 contacts during the 12 months before treatment to 20.1 ± 14 contacts during the 12 months after treatment (p = 0.02). Consumption of opioids decreased without reaching statistically significance from 1828 mg morphine equivalents per patient during 12 months before to 1382 mg 12 months after treatment (p >0.05). Regarding the primary outcomes, there were significant differences concerning social activity (p = 0.03), but not physical activity (p = 0.08). Patients improved in the psychometrical outcomes depression and anxiety with mean values in HAD for depression 8.15 before and 6.28 one year after treatment (p<0.05). For anxiety, MDR-participants had a mean value for HAD of 8.71 before and 7.0 12 months after treatment (p > 0.05). The mean level of pain intensity reported before MDR was reported as 6.71 on NRS-scale and sank to 6.27 one year after treatment finished. This decrease was not statistically significant (p > 0.05). The mean pain severity decreased from 4.38 to 3.97 and this change was not of statistical significance.

5 Discussion

In the present study, the effectiveness of multidisciplinary rehabilitation for patients with chronic non-cancer pain in a local primary health care setting was analyzed. The baseline characteristics of the population observed at the Pain Unit Arvika differed from the observed population of the Swedish Quality Register for Pain. The latter represents only participants from larger pain rehabilitation units. The Arvika-population consisted of a higher percentage of women, many patients with generalized pain conditions such as fibromyalgia, lower education levels, patients with a longer duration of complaints and a longer duration of sick-leave. In several studies, these items were described as negative predictors for successful rehabilitation [39, 40, 41]. A possible explanation might be that the socioeconomic population structure of rural inhabitants on average is often regarded as lower educated and with lower socio-economic status. In these rural areas, there might exist a different sociocultural view on pain and chronic pain conditions with women still take higher responsibility for children, family and housework leading to a higher burden and fewer possibilities to focus on disease prevention or rehabilitation.

Many studies on MDR focus on outcomes such as pain intensity, pain severity, depression and anxiety [42]. There is less known the role played by MDR concerning sick leave from work, in spite of the fact that avoiding sick leave is considered a primary goal of most rehabilitation concepts. Some studies used data from institutions such as social insurance systems, to examine levels of sick leave [19], but in the present study we used Swedestar, a computerize way to collect information from the patients’ journals. The tight correlation between pain intensity and pain severity on one hand and psychometric values such as anxiety and depression on the other hand is a well-known fact and discussed in many trials [43]. In spite of this, little is known on the impact of rehabilitation at primary care level to anxiety and depression. Depression and anxiety are common among patients with chronic pain [25] and have been found to increase the risk for reduced activity levels or social functioning. Improvement in psychological factors is described as essential for increased physical activity. In the present study, anxiety and depression declined at follow-up with significant reduction for depression (p<0.05). Furthermore, the effects of MDR in primary care on both physical and social activity are widely unknown. The MDR in the present primary care setting showed improvement in all three primary outcomes sick-leave, health care utilization and opioid prescription with a significant reduction in health-care utilization. It is well-known that patients with chronic pain complaints are characterized by specific healthcare consumption patterns with often a high frequency of contacts with primary health-care units as well as emergency units [44,45] but without improvement in symptoms. In that way, they are often described as a group of high users of the medical system putting special press on providers, although, there is hardly any focus on health-care utilization in rehabilitation research. This is possibly due to the fact that links between rehabilitation centers on the one hand and primary health care units on the other hand are minimal in many settings. Rehabilitation programs located in primary health care must therefore have a natural focus on the effectiveness regarding which extended health care is needed after completion of rehabilitation. Although the MDR itself did not in any way focus on medication more than optimizing it at assessment, there was a numerical decrease of opioid consumption at one-year follow up. All these findings mean a reduction of health care costs after treatment [46,47]. These benefits of MDR might be explained by a change in patients’ behavior, pain self-management or the way of dealing with more complex pain conditions. Possibly participants of MDR at the primary care level may feel more safe or secure due to the multidisciplinary treatment setting the patient in focus. Although in previous studies a decrease of pain intensity and pain severity was described [43,48] no statistically significant change was found in the present study, but the items for both social and physical activity increased. These findings may support the assumption as above stating that MDR in primary care may lead to better self-esteem in chronic pain patients who often are trapped in a vicious circle of pain, physical and social inactivity, sick leave, depression and a self-fulfilling prophecy of even more pain. In future, there is a strong need for more research analysing these outcomes on larger study populations, e.g. in multicentre studies.

This study suggests that MDR in primary care settings may lead to better coping in chronic pain condition with the result of lower depression scores and higher activity, leading to lower sick leave. This study demonstrated that there is a place for MDR in primary health care units with the advantage of local intervention in rural areas allowing the patients to achieve rehabilitation in their home environment.

6 Study limitations

A weakness of the analysis is the low study number with only 51 patients. This low number and the high proportion of women (86%) may be a source of bias. There is a need for evidence based studies concerning local rehabilitation programs in order to find out which patients may benefit from MDR at the primary care [41]. Naturally, there will be fewer participants in local settings compared to larger units at e.g. university hospitals or more urban rehabilitation clinics.

Another weakness is the lack of a control group. Here the patients have acted as their own controls, before and one year after participation in the pain rehab program. This is not optimal, a separate control group receiving no treatment would have been more appropriate. This is however difficult to arrange.

Therefore, the design using the patients as their own controls, before and after treatment, and comparing the results with data from a national quality register for pain rehabilitation is considered sufficient.

7 Conclusion

This trial describes a patient population that did not have access to larger units for MDR treatment. Further research is needed to identify practical criteria by which patients may best receive MDR at primary care units and which patients should be referred to a specialized pain unit. We furthermore are in need for larger and better conducted studies assessing MDR in primary care. As a suggestion for the future, local MDR therapy may become available for patients with access to a pain-or rehabilitation specialist. In that way, the specialist could use his/her special knowledge for recommendations of rehabilitation levels locally or in more specialized units. As well, all MDR units should have close contact with the larger specialized rehabilitation units for tight cooperation.

HIGHLIGHTS

Multidisciplinary rehabilitation for chronic pain in primary health care was analyzed

Depression and social activity improved significantly one year after treatment.

Sick leave and utilization of health care decreased significantly.

Patients with chronic pain benefit from rehabilitation in primary health care.

DOI of refers to article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.sjpain.2013.07.021

Author contributions

Klaus Stein contributed to conception and acquisition of data, Adriana Miclescu contributed to analysis and interpretation of data;

Both authors participate in revising it critically for important intellectual content

Both authors give final approval of the version to be submitted and for revised version.

Founding sources

None declared.

-

Conflict of interest

Conflict of interest statement: None declared.

Acknowledgments

Thanks to Ann Säterman for administrative support.

References

[1] Ahacic K, Käreholt I. Prevalence of musculoskeletal pain in the general Swedish population from 1968 to 2002: age, period and cohort patterns. Pain 2010;151:206–14.Suche in Google Scholar

[2] Neubauer E, Zahlten-Hingurange A, Schiltenwolf M, Buchner M. Multimodale Therapie bei chronischem HWS-und LWS-Schmerz. Schmerz 2006;20:210–8.Suche in Google Scholar

[3] SBU: Metoder för behandling av längvarig smärta. SBU-rapport; 2006,117/1+2.Suche in Google Scholar

[4] Breivik H, Collett B, Ventafridda V, Cohen R, Gallacher D. Survey of chronic pain in Europe: prevalence, impact on daily life and treatment. Eur J Pain 2006;10:287–333.Suche in Google Scholar

[5] Hasselström J, Liu-Palmgren J, Rasjö-Wrääk G. Prevalence of pain in general practice. Eur J Pain 2002;6:375–85.Suche in Google Scholar

[6] Bouhassira D, Lantèri-Minet M, Attal N, Laurent B, Touboul C. Prevalence of chronic pain with neuropathic characteristics in the general population. Pain 2008;136:380–7.Suche in Google Scholar

[7] Probst J, Moore C, Baxley E, Lammie J. Rural-urban differences in visits to primary care physicians. Fam Med 2002;34:609–15.Suche in Google Scholar

[8] Hällgren S, Fahlström M. Specialistteam och primärvärd I glesbygd – ett smärtfritt samarbete. Läkartidningen 2011;34:1560–2.Suche in Google Scholar

[9] Jensen I, Busch H, Bodin L, Hagberg J, Nygren A, Bergström G. Cost effectiveness of two rehabilitation programmes for neck and back pain patients: a seven year follow-up. Pain 2009;142:202–8.Suche in Google Scholar

[10] Scascighini L, Toma V, Dober-Spielmann S, Sprott H. Multidisciplinary treatment for chronic pain: a systematic review of interventions and outcomes. Rheumatology 2008;47:670–8.Suche in Google Scholar

[11] Schuetze A, Kaiser U, Ettrich U, Grosse K, Gossrau G, Schiller M, Pöhlmann K, Brannasch K, Scharnagel R, Sabatowski R. Evaluation einer multimodalen Schmerztherapie am Universitäts-Schmerzzentrum Dreseden. Schmerz 2009;23:609–17.Suche in Google Scholar

[12] SBU: Rehabiliteringvid långvarig smärta. SBU-rapport; 2010. p. 198.Suche in Google Scholar

[13] Guzman J, Esmail R, Karjalainen K, Malmivaara A, Irvin E, Bombardier C. Multidisciplinary rehabilitation for chronic low back pain: systematic review. BMJ 2001;322:1511–6.Suche in Google Scholar

[14] Bergstroem G, Bergstroem C., Hagberg J, Bodin L,Jensen I. A 7-yearfollow-up of multidisciplinary rehabilitation among chronic neck and back pain patients. Is sick leave outcome dependent on psychologically derived patient groups? Eur J Pain 2010;14:426–33.Suche in Google Scholar

[15] Keller S, Ehrhardt-Schmelzer S, Herda C, Schmid S, Basler H-D. Multidisciplinary rehabilitation for chronic back pain in an outpatient setting: a controlled randomized trial. Eur J Pain 1997;1:279–92.Suche in Google Scholar

[16] Rowbotham M, Gilron I, Glazer C, Rice A, Smith B, Stewart W, Wasan A. Can pragmatic trials help us better understand chronic pain and improvement treatment? Pain 2013;154:643–6.Suche in Google Scholar

[17] Zwarenstein M, Treweek S, Gagnier JJ, Altman D, Tunis S, Haynes B, Oxman A, Moher D. Improving the reporting of pragmatic trials: an extension of the CONSORT statement. BMJ 2008;337:a2390.Suche in Google Scholar

[18] Dworkin R, Turk D, McDermott M, Peirce-Sandner S, Burke LB, Cowan P, Farrar JT, Hertz S, Raja SN, Rappaport BA, Rauschkolb C, Sampaio C. Interpreting the clinical importance of group differences in chronic pain in clinical trials: IMMPACT recommendations. Pain 2009;146:238–44.Suche in Google Scholar

[19] Nyberg VE, Novo M, Sjölund BH. Do Multidimensional Pain Inventory scale scores changes indicate risk of receiving sick leave benefits 1 year after a pain rehabilitation programme? Disabil Rehabil 2011;33:1548–56.Suche in Google Scholar

[20] Nationella Registret over Smärtrehabilitering. Ärsrapport; 2011.Suche in Google Scholar

[21] Kim EB, Han HS, Chung JH, Park BR, Lim SN, Yim KH, Shin YD, Lee KH, Kim WJ, Kim ST. The effectiveness of a self-reporting bedside pain assessment tool for oncology inpatients. J Palliat Med 2012 [Epub ahead of print].Suche in Google Scholar

[22] van Dijk JF, Kappen TH, van Wijck AJ, Kalkman CJ, Schuurmans MJ. The diagnostic value of the numeric pain rating scale in older postoperative patients. J Clin Nurs 2012;21:3018–24.Suche in Google Scholar

[23] Oldenmenger WH, de Raaf PJ, de Klerk C, van der Rijt CC. Cut points on the 0–10 numeric rating scales for symptoms included in the Edmonton symptom assessment scale in cancer patients: a systematic review. J Pain Symptom Manage 2012 [Epub ahead ofprint].Suche in Google Scholar

[24] Zigmond AS, Snaith RP. The hospital anxiety and depression scale. Acta Psychiatr Scand 1983;67:361–70.Suche in Google Scholar

[25] Xie J, Bi Q, Li W, Shang W, Yan M, Yang Y, Miao D, Zhang H. Positive and negative relationship between anxiety and depression of patients in pain: a bifactor model analysis. PLoS ONE 2012;7:e47577.Suche in Google Scholar

[26] Herrmann C. International experiences with the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale – a review of validation data and clinical results. J Psychosom Res 1997;42:17–41.Suche in Google Scholar

[27] Kerns RD, Turk DC, Rudy TE. The West Haven-Yale Multidimensional Pain Inventory (WHYMPI). Pain 1985;23:345–56.Suche in Google Scholar

[28] Wittink H, Turk DC, Carr DB, Sukiennik A, Rogers W. Comparison of the redundancy, reliability, and responsiveness to change among SF-36, Oswestry Disability Index, and Multidimensional Pain Inventory. Clin J Pain 2004;20:133–42.Suche in Google Scholar

[29] Verra ML, Angst F, Staal JB, Brioschi R, Lehmann S, Aeschlimann A, de Bie RA. Reliability of the Multidimensional Pain Inventory and stability ofthe MPI classification system in chronic back pain. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 2012;24:155 [Epub ahead of print].Suche in Google Scholar

[30] Ware Jr JE, Sherbourne CD. The MOS 36-item short-form health survey (SF-36). Conceptual framework and item selection. Med Care 1992;30:473–83.Suche in Google Scholar

[31] Keller SD, Ware Jr JE,Bentler PM, Aaronson NK, Alonso J, Apolone G, Bjorner JB, Brazier J, Bullinger M, Kaasa S, Leplège A, Sullivan M, Gandek B. Use of structural equation modeling to test the construct validity ofthe SF-36 Health Survey in ten countries: results from the IQOLA Project. J Clin Epidemiol 1998;51:1179–88.Suche in Google Scholar

[32] Taft C, Karlsson J, Sullivan M. Performance of the Swedish SF-36 version 2.0. Qual Life Res 2004;13:251–6.Suche in Google Scholar

[33] Persson LO, Karlsson J, Bengtsson C, Steen B, Sullivan M. The Swedish SF-36 Health Survey II. Evaluation of clinical validity: results from population studies of elderly and women in Gothenburg. J Clin Epidemiol 1998;51:1095–103.Suche in Google Scholar

[34] DeSmedt D, Clays E, Doyle F, Kotseva K, Prugger C, Pajak A, Jennings C, Wood D, De Bacquer D. Validity and reliability of three commonly used quality of life measures in a large European population of coronary heart disease patients. Int J Cardiol 2012 [Epub ahead of print].Suche in Google Scholar

[35] Gu NY, Bell C, Botteman MF, Ji X, Carter JA, van Hout B. Estimating preference-based EQ-5D health state utilities or item responses from neuropathic pain scores. Patient 2012;12:185–97.Suche in Google Scholar

[36] Linde L, Sörensen J, Ostergaard M, Hoerslev-Petersen K, Hetland ML. Health-related quality oflife: validity, reliability, and responsiveness of SF-36, 15D, EQ-5D (corrected) RAQoL, and HAQ in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. J Rheumatol 2008;35:1528–37.Suche in Google Scholar

[37] Karlsson JA, Nilsson JÅ, Neovius M, Kristensen LE, Guelfe A, Saxne T, Geborek P. National EQ-5D tariffs and quality-adjusted life-year estimation: comparison of UK, US and Danish utilities in south Swedish rheumatiod arthritis patients. Ann Rheum Dis 2011;70:2163–6.Suche in Google Scholar

[38] http://www.fass.se/LIF/home/index.jspSuche in Google Scholar

[39] Thomtén J, Soares J, Sundin O. Pain among women: associations with socio-economic factors over time and the mediating role of depressive symptoms. Scand J Pain 2012;3:62–7.Suche in Google Scholar

[40] Sullivan M, Linton S, Shaw W. Risk-factortargeted psychological interventions for pain-related disability. In: Proceedings of the 11th world congress on pain 2006. Seattle: IASP Press; 2006.Suche in Google Scholar

[41] Heiskanen T, Roine RP, Kalso E. Multidisciplinary pain treatment – which patients do benefit? Scand J Pain 2012;3:201–7.Suche in Google Scholar

[42] Salaffi F, Stancati A, Silestri CA, Ciapetti A, Grassi W. Minimal clinically important changes in chronic musculoskeletal pain intensity measured on a numeric rating scale. Eur J Pain 2004;8:283–91.Suche in Google Scholar

[43] Hechler T, Dobe M, Kosfelder J, Damschen U, Hübner B, Blankenburg M, Sauer C, Zernikow B. Effectiveness of a 3-week multimodal inpatient pain treatment for adolescents suffering from chronic pain – statistical and clinical significance. Clin J Pain 2009;25:156–66.Suche in Google Scholar

[44] Hoelsted J, Alban A, Hagild K, Eriksen J. Utilisation of health care system by chronic pain patients who applied for disability pensions. Pain 1999;82:275–82.Suche in Google Scholar

[45] Mueller-Schwefe G, Freitag A, Höer A, Schiffhorst G, Becker A, Casser HR, Glaeske G, Thoma R, Treede RD. Healthcare utilization of back pain patients: results of a claims data analysis. J Med Econ 2011;14:816–23.Suche in Google Scholar

[46] Skouen J, Grasdal A, Haldorsen EM, Ursin H. Relative cost-effectiveness of extensive and light multidisciplinary treatment programs versus treatment as usual for patients with chronic low back pain on long-term sick leave. Spine 2002;9:901–10.Suche in Google Scholar

[47] Jensen B, Bergström G, Ljungquist T, Bodin L. A 3-year follow-up of a multidisciplinary rehabilitation programme for back and neck pain. Pain 2005;115:73–83.Suche in Google Scholar

[48] Merrick D, Sundelin G, Stâlnacke BM. One-Year Follow-up of two Different Rehabilitation Strategies for Patients with Chronic Pain. J Rehabil Med 2012;44:764–73.Suche in Google Scholar

© 2013 Scandinavian Association for the Study of Pain.

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Editorial comment

- Chronic pain – The invisible disease? Not anymore!

- Clinical pain research

- New objective findings after whiplash injuries: High blood flow in painful cervical soft tissue: An ultrasound pilot study

- Editorial comment

- Chronic pain is strongly associated with work disability

- Observational studies

- Chronic pain: One year prevalence and associated characteristics (the HUNT pain study)

- Editorial comment

- Pain rehabilitation in general practice in rural areas? It works!

- Clinical pain research

- Effectiveness of multidisciplinary rehabilitation treatment for patients with chronic pain in a primary health care unit

- Editorial comment

- Mirror-therapy: An important tool in the management of Complex Regional Pain Syndrome (CRPS)

- Topical review

- Mirror therapy for Complex Regional Pain Syndrome (CRPS)—A literature review and an illustrative case report

- Editorial comment

- New insight in migraine pathogenesis: Vasoactive intestinal peptide (VIP) and pituitary adenylate cyclase-activating polypeptide (PACAP) in the circulation after sumatriptan

- Original experimental

- Vasoactive intestinal peptide (VIP) and pituitary adenylate cyclase-activating polypeptide (PACAP) in the circulation after sumatriptan

- Editorial comment

- Statistical pearls: Importance of effect-size, blinding, randomization, publication bias, and the overestimated p-values

- Topical review

- Significance tests in clinical research—Challenges and pitfalls

- Editorial comment

- Biomarkers of pain – Zemblanity?

- Topical review

- Mechanistic, translational, quantitative pain assessment tools in profiling of pain patients and for development of new analgesic compounds

- Editorial comment

- Chronic Benign Paroxysmal Positional Vertigo (BPPV): A possible cause of chronic, otherwise unexplained neck-pain, headache, and widespread pain and fatigue, which may respond positively to repeated particle repositioning manoeuvres (PRM)

- Observational studies

- Pain and other symptoms in patients with chronic benign paroxysmal positional vertigo (BPPV)

- Editorial comment

- The most important step forward in modern medicine, “a giant leap for mankind”: Insensibility to pain during surgery and painful procedures

- Topical review

- In praise of anesthesia: Two case studies of pain and suffering during major surgical procedures with and without anesthesia in the United States Civil War-1861–65

- Editorial comment

- Intravenous non-opioids for immediate postop pain relief in day-case programmes: Paracetamol (acetaminophen) and ketorolac are good choices reducing opioid needs and opioid side-effects

- Clinical pain research

- Intravenous acetaminophen vs. ketorolac for postoperative analgesia after ambulatory parathyroidectomy

- Editorial comment

- Scandinavian Association for the Study of Pain 2013—Annual scientific meeting abstracts of pain research presentations and greetings from incoming President

- Abstracts

- Why does the impact of multidisciplinary pain management on quality of life differ so much between chronic pain patients?

- Abstracts

- Health care utilization in chronic pain—A population based study

- Abstracts

- Pain treatment in rural Ghana—A qualitative study

- Abstracts

- Pain psychology specialist training 2012–2014

- Abstracts

- Pain assessment, documentation, and management in a university hospital

- Abstracts

- Promising effects of donepezil when added to patients treated with gabapentin for neuropathic pain

- Abstracts

- A pediatric patients’ pain evaluation in the emergency unit

- Abstracts

- Proteomic analysis of cerebrospinal fluid gives insight into the pain relief of spinal cord stimulation

- Abstracts

- The DQB1(*)03:02 HLA haplotype is associated with increased risk of chronic pain after inguinal hernia surgery and lumbar disc herniation

- Abstracts

- On the pharmacological effects of two lidocaine concentrations tested on spontaneous and evoked pain in human painful neuroma: A new clinical model of neuropathic pain

- Abstracts

- The mineralocorticoid receptor antagonist spironolactone enhances morphine antinociception

- Abstracts

- Expression of calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II in dorsal root ganglia in diabetic rats 6 months and 1 year after diabetes induction

- Abstracts

- Histamine in the locus coeruleus attenuates neuropathic hypersensitivity

- Abstracts

- Pronociceptive effects of a TRPA1 channel agonist methylglyoxal in healthy control and diabetic animals

- Abstracts

- Human inducible pluripotent stem cell-derived sensory neurons express multiple functional ion channels and GPCRs

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Editorial comment

- Chronic pain – The invisible disease? Not anymore!

- Clinical pain research

- New objective findings after whiplash injuries: High blood flow in painful cervical soft tissue: An ultrasound pilot study

- Editorial comment

- Chronic pain is strongly associated with work disability

- Observational studies

- Chronic pain: One year prevalence and associated characteristics (the HUNT pain study)

- Editorial comment

- Pain rehabilitation in general practice in rural areas? It works!

- Clinical pain research

- Effectiveness of multidisciplinary rehabilitation treatment for patients with chronic pain in a primary health care unit

- Editorial comment

- Mirror-therapy: An important tool in the management of Complex Regional Pain Syndrome (CRPS)

- Topical review

- Mirror therapy for Complex Regional Pain Syndrome (CRPS)—A literature review and an illustrative case report

- Editorial comment

- New insight in migraine pathogenesis: Vasoactive intestinal peptide (VIP) and pituitary adenylate cyclase-activating polypeptide (PACAP) in the circulation after sumatriptan

- Original experimental

- Vasoactive intestinal peptide (VIP) and pituitary adenylate cyclase-activating polypeptide (PACAP) in the circulation after sumatriptan

- Editorial comment

- Statistical pearls: Importance of effect-size, blinding, randomization, publication bias, and the overestimated p-values

- Topical review

- Significance tests in clinical research—Challenges and pitfalls

- Editorial comment

- Biomarkers of pain – Zemblanity?

- Topical review

- Mechanistic, translational, quantitative pain assessment tools in profiling of pain patients and for development of new analgesic compounds

- Editorial comment

- Chronic Benign Paroxysmal Positional Vertigo (BPPV): A possible cause of chronic, otherwise unexplained neck-pain, headache, and widespread pain and fatigue, which may respond positively to repeated particle repositioning manoeuvres (PRM)

- Observational studies

- Pain and other symptoms in patients with chronic benign paroxysmal positional vertigo (BPPV)

- Editorial comment

- The most important step forward in modern medicine, “a giant leap for mankind”: Insensibility to pain during surgery and painful procedures

- Topical review

- In praise of anesthesia: Two case studies of pain and suffering during major surgical procedures with and without anesthesia in the United States Civil War-1861–65

- Editorial comment

- Intravenous non-opioids for immediate postop pain relief in day-case programmes: Paracetamol (acetaminophen) and ketorolac are good choices reducing opioid needs and opioid side-effects

- Clinical pain research

- Intravenous acetaminophen vs. ketorolac for postoperative analgesia after ambulatory parathyroidectomy

- Editorial comment

- Scandinavian Association for the Study of Pain 2013—Annual scientific meeting abstracts of pain research presentations and greetings from incoming President

- Abstracts

- Why does the impact of multidisciplinary pain management on quality of life differ so much between chronic pain patients?

- Abstracts

- Health care utilization in chronic pain—A population based study

- Abstracts

- Pain treatment in rural Ghana—A qualitative study

- Abstracts

- Pain psychology specialist training 2012–2014

- Abstracts

- Pain assessment, documentation, and management in a university hospital

- Abstracts

- Promising effects of donepezil when added to patients treated with gabapentin for neuropathic pain

- Abstracts

- A pediatric patients’ pain evaluation in the emergency unit

- Abstracts

- Proteomic analysis of cerebrospinal fluid gives insight into the pain relief of spinal cord stimulation

- Abstracts

- The DQB1(*)03:02 HLA haplotype is associated with increased risk of chronic pain after inguinal hernia surgery and lumbar disc herniation

- Abstracts

- On the pharmacological effects of two lidocaine concentrations tested on spontaneous and evoked pain in human painful neuroma: A new clinical model of neuropathic pain

- Abstracts

- The mineralocorticoid receptor antagonist spironolactone enhances morphine antinociception

- Abstracts

- Expression of calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II in dorsal root ganglia in diabetic rats 6 months and 1 year after diabetes induction

- Abstracts

- Histamine in the locus coeruleus attenuates neuropathic hypersensitivity

- Abstracts

- Pronociceptive effects of a TRPA1 channel agonist methylglyoxal in healthy control and diabetic animals

- Abstracts

- Human inducible pluripotent stem cell-derived sensory neurons express multiple functional ion channels and GPCRs