Abstract

Natural fiber-reinforced composites are getting more attention from researchers and manufacturing companies to replace metals and synthetic materials that have dominated the manufacturing industries. In this study, the mechanical properties of unidirectional (UD) flax roving-reinforced composites and woven fabric-reinforced composites were investigated. Three different composites were prepared from flax rovings, which have the same linear density and epoxy resin matrix, with different reinforcement and composite preparation methods. The samples were subjected to experimental tests of flexural rigidity and tensile strength in a parallel and perpendicular direction to fiber orientation. The test results showed that flexural rigidity and tensile strength of flax fiber-reinforced composites are highly dependent on the direction of fiber orientation. The results also reveal that in a parallel direction to fiber orientation, UD composites have higher flexural rigidity and tensile strength than woven fabric-reinforced composite.

1 Introduction

A composite material is defined as a material consisting of two or more constituent materials (reinforcement and matrix) with different chemical and physical properties in which the property of the final composite is intended to be better than the component materials [1,2,3]. Depending on the ideas and concepts that need to be identified, composite materials are classified into different groups [2]. Natural fiber-reinforced composite (NFRC) is one of the composite classifications based on their reinforcement type [4]. Textile composites are formed to use textile fibers, yarns, and fabrics as a composite reinforcement to achieve high-strength and low-density composites with reasonable manufacturing cost [4, 5, 6]. Nowadays, flax fiber-reinforced composite is one from natural fiber textile-reinforced composites, which is getting more attention from manufacturing industries and researchers due to its unique properties, including cost-effectiveness, low density, good specific strength, good bio-degradability, and environment-friendly material [3, 5, 7,8,9,10]. These properties widely spread the usage of flax fiber-reinforced composites in the aerospace, civil engineering, automotive, and many other industries [8, 10, 11].

The flax fiber-reinforced composite materials are produced by incorporating flax fibers with polymeric materials to fulfill the mechanical properties of the materials needed for different applications. The method of fabricating composite materials also depends on the intended end use of the composite and specific features of the materials looked-for the application.

Unidirectional (UD) composites are arranged in one direction with all fibers in a matrix; they are distinguished by their reinforcement angle [12]. The fabric structure/reinforcement type, constituent fiber, a resin matrix, composite preparation method, and their interface are the essential things to determine the strength of composite material [13, 14]. Omrani et al. [15] showed the impact of the weaving process and the waviness of weft yarns on the mechanical properties of the composites. Yukseloglu et al. [16] presented the modulus of UD flax fiber-reinforced composites increases with the increase of fiber volume fraction percentage in the reinforcement. Prasad et al. [17] showed the influence of composite preparation methods on the mechanical strength of composite material. Many researchers investigated and revealed that UD composites provide the greatest strength in the fiber direction [7, 9, 12].

The crucial characteristics of textile fiber-reinforced composites are their anisotropic property, which means their mechanical property is in-line with the direction of fiber orientation in the composite structure [18]. In this study, samples were tested in the parallel and perpendicular direction to the fiber orientations in the composite structure to determine and analyze the anisotropic mechanical properties of sateen weave fabric-reinforced composites and UD flax roving-reinforced composites.

2 Materials and methods

The low twist flax roving supplied by the Safilin company, which has a linear density of 190 tex, was used to produce the reinforcements. Based on the experimental test performed in the laboratory of the Institute of Architecture of Textiles at the Lodz University of Technology, flax rovings are characterized by breaking strength of 6.82 cN/tex and 1.32% elongation at the break.

An epoxy resin LH145 from Havel composites company was used as a matrix. Based on the supplier recommendation, epoxy resin LH145 was mixed with H135 hardener in the ratio of 100:35 parts by weight, respectively. Also, three different reinforcement materials were prepared from the same count of flax roving (190 tex) with varying roving densities per centimeter and employing different ways of preparation, as described below. The first type of reinforcement was prepared from 3/10 sateen weave fabric, which was woven from 190 tex flax yarn (weft) and 40 tex cotton yarn (warp) on a MAV rapier loom. The weft (flax yarn) was the prevailing yarn in the fabric structure with a density of 14 yarns/cm and the cotton yarn with a density of 10 yarns/cm (Figure 1a). The second type of reinforcement was unidirectionally arranged flax roving prepared by removing warp yarn (cotton) from woven fabric (Figure 1b); this UD reinforcement has a density of 14 rovings/cm. The third type of reinforcement was prepared on a rectangular frame, which has been made from the sheet of metals and wooden materials fixed with the reeds. Each single roving strand was drawn through reeds to form a parallelly arranged UD flax roving reinforcement (Figure 1c). The UD flax reinforcement made by this method has a density of 10 rovings/cm.

Different types of reinforcements used during composite preparation: (a) 3/10 sateen weave fabric used as a composite reinforcement, (b) unidirectional flax roving reinforcement prepared by removing cotton yarns from the woven fabric, and (c) unidirectional flax roving reinforcement made on a frame.

2.1 Composite preparation methods

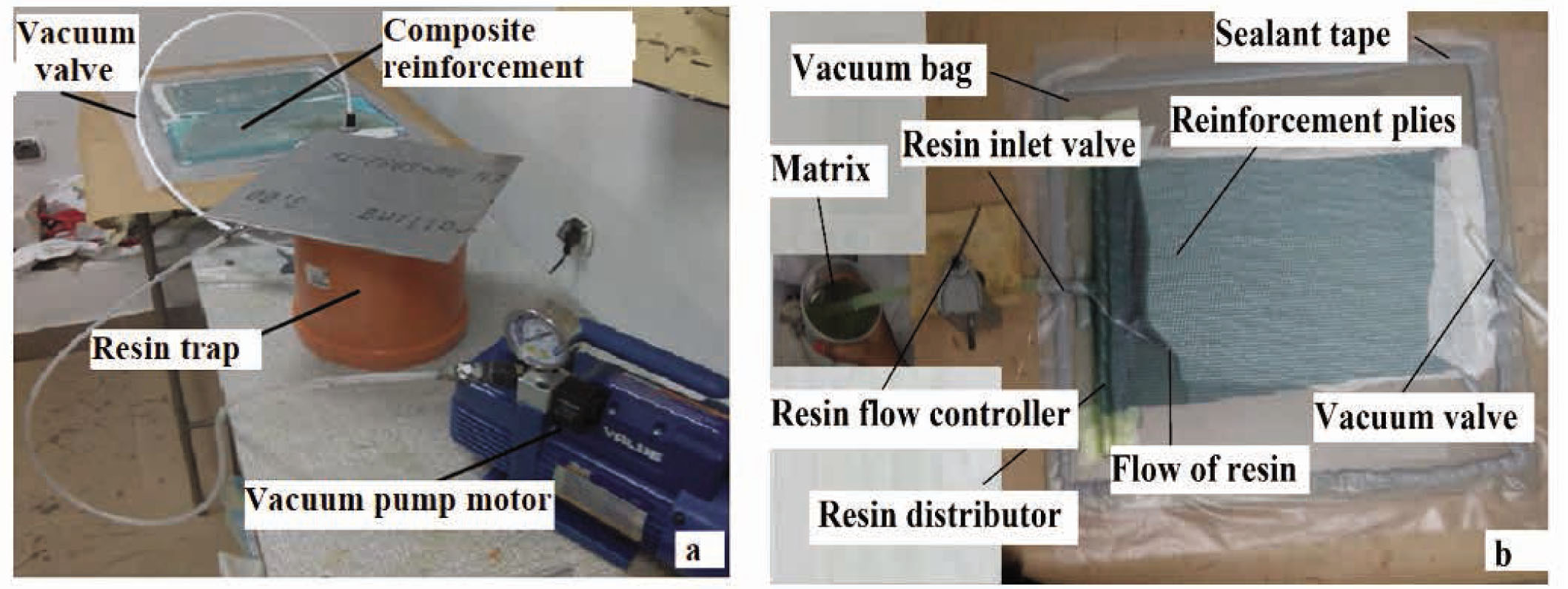

Flax roving-reinforced composites were prepared by vacuum bagging (Figure 2a) and resin infusion (Figure 2b) [19] methods of composite formation. In both methods, the mold was sealed using a vacuum bag, and atmospheric pressure was applied to hold laminate plies together. The pressure between the outside and inside of the sealed envelope must be equal to 0 to fabricate composite material with better quality. The pressure difference was measured using the gauge bar mounted on a vacuum pump motor. The main difference between the vacuum bagging method (Figure 2a) and the resin infusion method (Figure 2b) is the way of applying the resin to the reinforcement. In case of vacuum bagging method (Figure 2a), each ply of reinforcement has to be wetted manually using epoxy resin before the mold is sealed; in contrast to this, in the resin infusion method (Figure 2b), first, the dry plies of reinforcement have to be placed on the mold and sealed, as shown in Figure 2b, and then epoxy resin is slowly drawn to the envelope through a resin inlet valve, and by using a resin distribution medium, the resins are equally distributed over the surface of reinforcement plies. In both methods, a vacuum outlet valve is used to suck the air in the envelope and excess resin residues.

Methods of composite formation: (a) vacuum bagging method and (b) resin infusion method.

The vacuum bagging method of composite formation was used to produce woven fabric-reinforced composites, and the resin infusion method was used to produce UD composites. Also, the formation of UD composites was tried using a vacuum bagging method, but due to the difficulties of removing air from the gaps between parallelly arranged rovings, the produced composite was not good enough to be used for further experimental tests. In both methods, two layers of reinforcements were stacked together to produce the composite.

2.2 Experiments

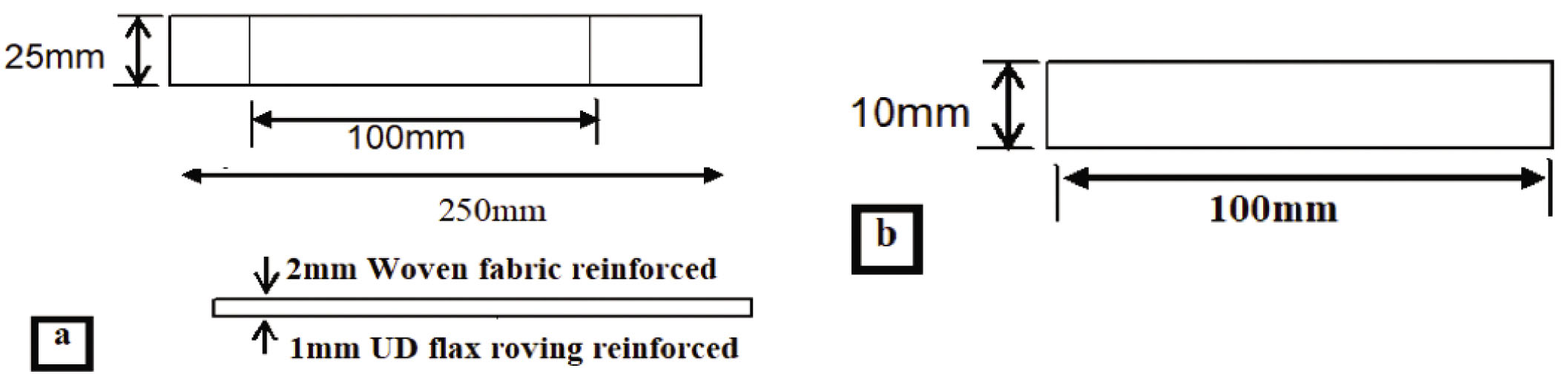

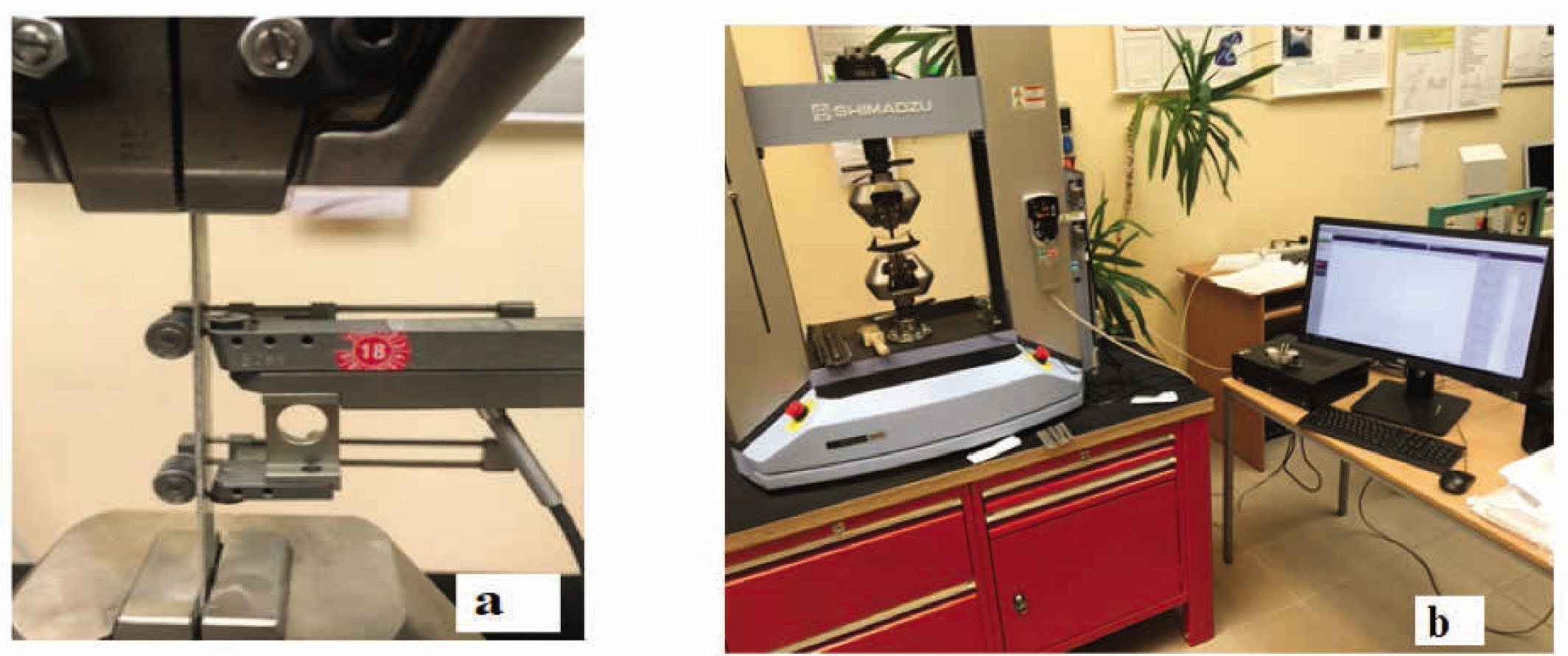

The tensile strength and flexural rigidity experimental tests were performed at the Lodz University of Technology in the Faculty of Mechanical Engineering by using the Shimadzu AG-X plus testing machine (Figure 4a), which has a maximum testing load of 50 KN. For the tensile strength experimental test, 10 specimens have been tested for each sample type both in perpendicular and parallel direction to fiber orientation in the composite structure. These specimens’ dimensions were prepared based on the American Standard of Test Method (ASTM) D3039 (Figure 3a) with a testing condition of 2 mm/min speed.

Specimen dimension: (a) tensile strength test and (b) flexural rigidity test.

Shimadzu AG-X plus testing machine: (a) tensile strength test and (b) flexural rigidity test.

Flexural rigidity test was performed to know the force required to bend the flax fiber-reinforced composites and determine the stiffness of the material. To do so, 10 specimens were prepared from each sample, both in perpendicular and parallel direction to fiber orientation in the composite structure with the dimension of the specimens(fig.3b) were prepared based on the ASTM D7264/D 7264-M standard. The specimens were tested using a three-point loading system(fig.4b) method of flexural rigidity test. The samples were tested with a speed of 5 mm/min.

3 Results and discussion

Experimental test results conducted for flexural rigidity and tensile strength experimental tests of composites are presented in Tables 1 and 2.

Three-point loading system flexural rigidity experimental test result

| Sample type | Test direction | Flexural stress (MPa) | Standard deviation | Coefficient of variation (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Woven | 0° | 117 | 1.5 | 1.2 |

| 90° | 27 | 0.9 | 3.4 | |

| UD-10 | 0° | 134 | 8.0 | 5.9 |

| 90° | 23 | 2.2 | 9.5 | |

| UD-14 | 0° | 163 | 20.2 | 12.3 |

| 90° | 38 | 3.7 | 9.7 |

Average tensile strength experimental test results

| Test results | Sample type | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Woven | UD-10 | UD-14 | ||||

| 0° | 90° | 0° | 90° | 0° | 90° | |

| Tensile strength (MPa) | 145 | 23 | 179 | 16 | 116 | 13 |

| Standard deviation | 8.3 | 0.7 | 18.5 | 3.5 | 19 | 0.9 |

| Coefficient of variation (%) | 5.7 | 3.0 | 10.3 | 21.9 | 16.4 | 6.9 |

| Modulus (GPa) | 7 | 2 | 6 | 4 | 7 | 1.5 |

| Standard deviation | 0.6 | 0.1 | 1.0 | 0.2 | 1.5 | 0.1 |

| Coefficient of variation (%) | 8.6 | 5.0 | 16.7 | 5.0 | 21.4 | 6.0 |

| Elongation (%) | 1 | 4 | 1 | 0.14 | 0.8 | 0.06 |

| Standard deviation | 0.1 | 0.4 | 0.1 | 0.01 | 0.05 | 0.01 |

| Coefficient of variation (%) | 10.0 | 10.0 | 10.0 | 7.1 | 6.3 | 16.7 |

3.1 Analysis of the influence of fiber orientation and reinforcement types on the flexural rigidity of composites

The composite sample reinforced with sateen weave fabric has 28.47% and 13.07% lower ability to withstand flexural stress in comparison to UD composite reinforced by 14 rovings/cm and 10 rovings/cm respectively in the direction of fiber orientation (Figure 5), this illustrates UD reinforced flax composites have higher bendable property than woven-reinforced composites. Also, in a perpendicular direction to fiber orientation, 14 rovings/cm reinforced UD composite has 28.81% and 39.21% higher flexural stress than woven fabric-reinforced composite and 10 rovings/cm reinforced UD composites, respectively (Figure 5). During the flexural rigidity experimental test, when the load applied to specimens in the direction of fiber orientation (0°), the specimens were bent to their maximum deflection point in all types of composites made; after the removal of applied load, each specimen is almost returned to their original position. Also, when experimental tests were carried out on specimens in perpendicular to the fiber orientation, both unidirectionally reinforced composites were cracked. In contrast to this, woven fabric-reinforced composites were almost returned to their original position after the removal of applied force.

The average flexural stress of flax-reinforced composite samples.

3.2 Analysis of the influence of fiber orientation and reinforcement types on the tensile strength of composites

The influence of reinforcement type and density of roving on the tensile strength of composites are shown in Figure 6. The study of tensile test result reveals that when a tensile force is applied to the specimen on a parallel direction to fiber orientation (0°), UD composite reinforced with 10 roving/cm has 18.73% and 34.90% higher tensile strength than woven fabric-reinforced composite and UD flax composite reinforced with 14 rovings/cm, respectively. As a result of the weaving process, the tensile strength of yarns is degraded, and this affects the composite material reinforced either by using woven fabric or UD composite made from yarns/rovings removed from woven fabric, this discloses the influence of single yarn/roving tensile properties on the composite material tensile strength.

The average tensile strength of flax fiber-reinforced composite samples.

The tensile experimental test carried out on the specimens in a perpendicular direction to the fiber orientation in the composite structure shows that woven fabric-reinforced composite has 44.64% and 30.62% higher tensile strength than composite reinforced by 14 rovings/cm and 10 rovings/cm, respectively. In this case, the woven fabric-reinforced composite has exhibited high tensile strength because of the presence of cotton yarn in the warp direction of the fabric.

Summing up the analysis of flexural rigidity and tensile strength of the composites shows that mechanical properties of flax fiber-reinforced composites are highly dependent on the direction of fiber orientation in the composite structure with significantly showing higher flexural rigidity and tensile strength in the direction of fiber orientation, signifying that textile material-reinforced composites have anisotropic properties. Besides, unidirectionally reinforced flax fiber exhibits higher tensile strength and flexural rigidity than woven fabric-reinforced composites. In contrast, woven fabric-reinforced composites have higher tensile strength than unidirectionally reinforced composites when the test was carried out in a perpendicular direction. Woven fabric-reinforced composite has exhibited excellent elongation in comparison with UD flax roving-reinforced composites during the tensile strength test because of the crimpage of yarns in the structure of the woven fabric.

4 Conclusion

In this study, the mechanical properties of woven and UD flax roving-reinforced epoxy composites were investigated. The experimental result obtained shows that woven fabric and UD flax roving-reinforced composites have higher tensile strength and flexural rigidity in the fiber direction (0°) compared with the experimental test carried out in the perpendicular direction (90°). Also, the experimental result reveals that the density of rovings in the composite structure influences the mechanical properties of UD flax fiber-reinforced composites, the higher density, the higher flexural rigidity property, and the vice-versa is true. The flexural rigidity and tensile strength of UD composites are higher than woven fabric-reinforced composites in the direction of fiber orientation. However, the woven fabric-reinforced composites have excellent tensile strength properties in the perpendicular direction to the fiber orientation, compared with UD composites.

Acknowledgment

We would like to thank every individual who supported us during this work and especially to Mr. Henry Browarski, for helping us in laboratory work with a full of patience and kindness. We are also grateful to Dr. Eng. Mariusz Urbańczyk, Faculty of Mechanical Engineering, for enabling us to carry out mechanical tests in the laboratory and also for helping us.

References

[1] Aleksendrić, D., Carlone, P. (2015). In soft computing in the design and manufacturing of composite materials. Composite Materials Manufacturing.10.1533/9781782421801.15Search in Google Scholar

[2] Hull D. (2012). An introduction to composite material. Cambridge Solid State Science Series, [ISBN 0 521 28392–2].10.1017/CBO9781139170130Search in Google Scholar

[3] Masuelli, A. M. (2013). Introduction of fibre-reinforced polymers − polymers and composites: concepts, properties, and processes. Materials Science.Search in Google Scholar

[4] Messiry, M. El. (2017). Natural fiber textile composite engineering. (1st ed.).10.1201/9781315207513Search in Google Scholar

[5] Vanleeuw, B., Carvelli, V., Barburski, M., Lomov, S. V., van Vuure, A. W. (2015). Quasi-unidirectional flax composite reinforcement: deformability and complex shape forming. Composites Science and Technology, 110, 76–86.10.1016/j.compscitech.2015.01.024Search in Google Scholar

[6] Long, A. C. (2006). Design and manufacture of textile composites. (1st ed.) Woodhead Publishing.10.1533/9781845690823Search in Google Scholar

[7] Czub, K., Barburski, M. (2017). Mechanical properties of flax roving composites reinforcement. IOP Conference Series: Materials Science and Engineering 254 (2017), 17th World Textile Conference AUTEX 2017, 29–31 May, Greece.10.1088/1757-899X/254/4/042004Search in Google Scholar

[8] Aly, N. M. (2017). A review on utilization of textile composites in transportation towards sustainability. 17th World Textile Conference AUTEX 2017, 29 – 31 May, Greece.10.1088/1757-899X/254/4/042002Search in Google Scholar

[9] Habibi, M., Laperriere, L., Lebrun, G., Toubal, L. (2017). Combining short flax fiber mats and unidirectional flax yarns for composite applications. Effect of short flax fibers on baxial mechanical properties and damage behaviour. Composite Part B Engineering, 123, 165–178.10.1016/j.compositesb.2017.05.023Search in Google Scholar

[10] Zhu, J., Zhu, H., Njuguna, J., Abhyankar, H. (2013). Recent development of flax fibres and their reinforced composites based on different polymeric matrices. Materials, 6, 5171–5198.10.3390/ma6115171Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[11] Yan, L., Chouw, N., Jayaraman K. (2013). Flax fiber and its composites - a review. Composite: Part B, Elsevier, 56, 296–317.10.1016/j.compositesb.2013.08.014Search in Google Scholar

[12] European Confederation of Flax and Hemp. (2012). Flax and Hemp fibres: a natural solution for the composite industry. (1st ed.).Search in Google Scholar

[13] Morozov, E. V. (2004). Mechanics and analysis of fabric composites and structures, AUTEX Research Journal, 4(2).10.1515/aut-2004-040202Search in Google Scholar

[14] Barburski, M., Weigert, L., Fernández, I., Pouplier, S., Roth, S., et al. (2017). Woven reinforced composites for improving the design of the hyperextension brace. Journal of Fashion Technology & Textile Engineering, S3. doi:10.4172/2329-9568.S3-002.Search in Google Scholar

[15] Omrani, F., Wang, P., Soulat, D., Ferreira, M. (2017). Mechanical properties of flax-fibre-reinforced preforms and composites: influence of the type of yarns on multi-scale characterisations. Composites Part A: Applied Science and Manufacturing, 93, 72–81.10.1016/j.compositesa.2016.11.013Search in Google Scholar

[16] Yukseloglu, S. M., Yoney, H. (2016). The mechanical properties of flax fibre reinforced composites, doi:10.1007/978-94-017-75151_19.Search in Google Scholar

[17] Vishnu, P., Muhammed, H. C. V., Abhiraj, R., Jospeh, M., Kannan, S., et al. (2019). Mechanical properties of flax fiber reinforced composites manufactured using hand layup and compression molding—a comparison. 10.1007/978-981-13-6412-9_72.Search in Google Scholar

[18] Vanleeuw, B., Carvelli, V., Lomov, S. V., Barburski, M., Vuure, A. W. (2014). Deformability of a flax reinforcement for composite materials. Key Engineering Materials, 611–612, 257–264; Trans Tech Publications, Switzerland doi:10.4028/www.scientific.net/KEM.611-612.257.Search in Google Scholar

[19] Barburski, M., Masajtis, J. (2009). Modelling of the change of structure of woven fabric under mechanical loading. Fibres and Textiles Easter Europe, 1(72), 39–45, [ISSN 1230-3666].Search in Google Scholar

© 2021 Tsegaye Sh. Lemmi et al., published by Sciendo

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Defect Detection of Printed Fabric Based on RGBAAM and Image Pyramid

- Hydrophilization of Polyester Textiles by Nonthermal Plasma

- Prediction of Sewing Thread Consumption for Over-Edge Stitches Class 500 Using Geometrical and Multi-Linear Regression Models

- Experimental Investigation of the Properties of Laminated Nonwovens Used for Packaging of Powders in Mineral Warmers

- An Approach to Estimate Dye Concentration of Domestic Washing Machine Wastewater

- Moisture and Thermal Transport Properties of Different Polyester Warp-Knitted Spacer Fabric for Protective Application

- Quick Detection of Aldehydes and Ketones in Automotive Textiles

- Identification of Miao Embroidery in Southeast Guizhou Province of China Based on Convolution Neural Network

- Effect of Temperature on the Structure and Filtration Performance of Polypropylene Melt-Blown Nonwovens

- Analysis of Mechanical Properties of Unidirectional Flax Roving and Sateen Weave Woven Fabric-Reinforced Composites

- Development of Mask Design Knowledge Base Based on Sensory Evaluation and Fuzzy Logic

- Preparation of Polypyrrole/Silver Conductive Polyester Fabric by UV Exposure

- A New Approach for Thermal Resistance Prediction of Different Composition Plain Socks in Wet State (Part 2)

- Analyzing Thermophysiological Comfort and Moisture Management Behavior of Cotton Denim Fabrics

- Comparison of the Effects of the Cationization of Raw, Bio- and Alkali-Scoured Cotton Knitted Fabric with Different Surface Charge Density

Articles in the same Issue

- Defect Detection of Printed Fabric Based on RGBAAM and Image Pyramid

- Hydrophilization of Polyester Textiles by Nonthermal Plasma

- Prediction of Sewing Thread Consumption for Over-Edge Stitches Class 500 Using Geometrical and Multi-Linear Regression Models

- Experimental Investigation of the Properties of Laminated Nonwovens Used for Packaging of Powders in Mineral Warmers

- An Approach to Estimate Dye Concentration of Domestic Washing Machine Wastewater

- Moisture and Thermal Transport Properties of Different Polyester Warp-Knitted Spacer Fabric for Protective Application

- Quick Detection of Aldehydes and Ketones in Automotive Textiles

- Identification of Miao Embroidery in Southeast Guizhou Province of China Based on Convolution Neural Network

- Effect of Temperature on the Structure and Filtration Performance of Polypropylene Melt-Blown Nonwovens

- Analysis of Mechanical Properties of Unidirectional Flax Roving and Sateen Weave Woven Fabric-Reinforced Composites

- Development of Mask Design Knowledge Base Based on Sensory Evaluation and Fuzzy Logic

- Preparation of Polypyrrole/Silver Conductive Polyester Fabric by UV Exposure

- A New Approach for Thermal Resistance Prediction of Different Composition Plain Socks in Wet State (Part 2)

- Analyzing Thermophysiological Comfort and Moisture Management Behavior of Cotton Denim Fabrics

- Comparison of the Effects of the Cationization of Raw, Bio- and Alkali-Scoured Cotton Knitted Fabric with Different Surface Charge Density