Abstract

Heated gloves have been gaining popularity due to increasing work safety demands. The objective of the present work was to evaluate the effects of the presence of chemical hand warmers in protective gloves. The study involved three types of gloves appropriate for work activities performed in cold environments. Several hand warmer variants were designed, differing in terms of shape and location within the glove, which are of great relevance to the comfort of use. Manual dexterity tests were designed to approximate real conditions of the work environment, allow for simulation of occupational activities, and involve various aspects of manipulation.

1 Introduction

Cold environments are defined as locations with an air temperature equal to or less than 10°C. They put workers at risk of excessive cooling of distal body parts, and thus necessitate the use of protective gloves with enhanced insulation properties. Such gloves are usually made from textile systems, including waterproof leather and coated materials. In addition, textiles with superior thermal insulating capacity are often used to further reduce heat loss. In practice, cold-protective gloves should be primarily characterized by effective insulation [1, 2], good ergonomic properties and comfort of use [3, 4, 5], as well as the ability to actively maintain optimum hand temperature [6]. If gloves worn by the workers do not correspond to work duration and temperature exposure, they may lead to excessive cooling of the upper extremities [7, 8, 9] or frostbite as a result of contact with cold surfaces [10, 11].

Since traditional insulation materials often fail to meet user requirements, new state-of-the-art glove designs may incorporate active or passive warmers, including chemical hand warmers. Many of such solutions have been patented [12, 13, 14, 15, 16]. However, traditional batteries (whether rechargeable or not) are rather large, which in practice adversely affects user’s comfort. Another drawback is the risk of discharging before the completion of a task. These disadvantages have motivated some scholars to undertake research in the field of fibrous power supply (FPS), which is also known as textronic technology of power generation. While FPS products are characterized by a considerable ability to store electric energy, they still need to be improved in terms of strength, elasticity, and compatibility with textiles. It should be noted that such solutions remain expensive and energy-intensive. Another source of heating is offered by phase-change materials, which may store and release large amounts of energy. Those materials can be implemented in different ways, but the effectiveness of their various applications is not always sufficient to satisfy user expectations. Wired solutions tend to make gloves rigid and uncomfortable, in which case their heating advantages may be outweighed by difficulties related to occupational performance. Alternatively, one can use chemical hand warmers in which thermal energy is generated by various mixtures of powdered iron, alkaline, alkaline earth, or transition metals, activated or nonactivated carbon, as well as other components, depending on the application [17]. These solutions have been applied in patented glove designs for maintaining and releasing thermal energy [18, 19, 20]. The aforementioned warmers are typically placed in special pockets integrated with the dorsal or palmar parts of gloves. Given the great complexity of the problem, many workers remain at risk of excessive upper and lower limb cooling upon exposure to cold. Although new technologies are being developed to alleviate this problem, so far no universal practical solution has been designed. Taking into consideration the need to ensure safe working conditions, gloves with chemical warmers seem to offer a promising, practical alternative to existing electrical heating systems. The former contains active mineral components, such as a mixture of iron, activated carbon, sodium chloride, diatomite, and vermiculite, which enter into simple and safe chemical reactions in the presence of oxygen from the air. It is possible to adjust the warmers to the individual needs of the users in terms of the amount of heat produced under different cold exposure conditions, while maintaining glove functionality and hygiene. The applied mineral compounds are environmentally friendly, easily biodegradable, and safe for humans. The warmers are filled with a mixture of powdered iron; alkali metal, alkaline earth metal, or transition metal salts; activated and nonactivated carbon; and other components, depending on the application [21]. Active mineral compounds in the form of “hot packs” were first used in sports medicine and physical therapy. Local heat treatment was intended to improve motor performance [22, 23]. Over time, several exothermic reactions were patented; they involved mixtures of mineral components [24]; alkali metal and alkaline earth metal oxides and hydroxides [25]; iron oxidation in water [26]; reactions involving water, sand, and anhydrous magnesium sulfate [27]; reactions involving iron powder, sodium chloride, water, and activated carbon in an air-permeable bags made of polyethylene–hydrophobic polyolefin, in which the product maintains a temperature of 38–44°C for 1 h after activation [28]; and reactions of iron powder, carbon, alkali metal, and alkaline earth metal salts [29, 30]. These solutions led to the development of gloves with integrated pockets containing thermal packs retaining and transmitting heat energy that can be used, for example, in the prevention of Raynaud’s disease [18]; winter sports gloves [19]; and gloves and pads for local heat therapy [20].

However, there are few research papers concerning the design and use of warmers in gloves, one notable exception is in Sands et al. [31]. The authors reported that some of the studied devices exceeded packaging claims while others fell short, that the thermal behavior of the devices was variable over time, and that there appeared to be a simple but strong relationship between the mass of the devices and the duration of their heat production. Furthermore, they suggested that future research should include a wider variety of warmers using different chemical processes and address the influence of insulation on user warmth and comfort.

Therefore, the objective of the present work was to evaluate the effects of the presence of commercially available chemical hand warmers in protective gloves. In addition, the study was designed to determine which warmers in which positions within the glove are most favorable for user comfort and safety.

This paper is the first step toward a better understanding of the effects of the chemical hand warmers in the glove structure on user comfort in five manual dexterity tests. The main limitation was that the applied warmers were passive (turned off), as physiological response was not investigated.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Experimental protective gloves and the applied chemical hand warmers

The study involved three types of gloves: mitts (variant 1), five-finger gloves (variant 2), and rubber gloves with knitwear inserts (variant 3). These variants were selected as appropriate for work activities performed in cold environments. The characteristics of the three glove variants are given in Table 1.

Material characteristics of composite layers used in the tested glove variants

| Mitts –Variant 1 | |

| PU-coated PA 220 g/m2 |

| Chlorinated PET CSM—coated PA 235 dtex or 212 den (370 g/m2) | |

| 100% PE microfleece (130 g/m2) | |

| 100% PE nonwoven (110 g/m2) | |

| Five-finger gloves – Variant 2 | |

| Grain leather 0.8–0.9 mm |

| 100% PE microfleece 130 g/m2 | |

| 50% PA, 50% PU fleece (500 g/m2) | |

| 100% PE nonwoven, (110 g/m2) | |

| 89.5% PES/6.5% spandex/4% PU (380 g/m2), membrane—100% PU | |

| Five-finger rubber gloves with knitted inserts – Variant 3 | |

| The system consists of: |

| Rubber five-finger gloves made of 100% polyacrylonitrile | |

| Knitted five-finger inserts made of 100% PAN fiber | |

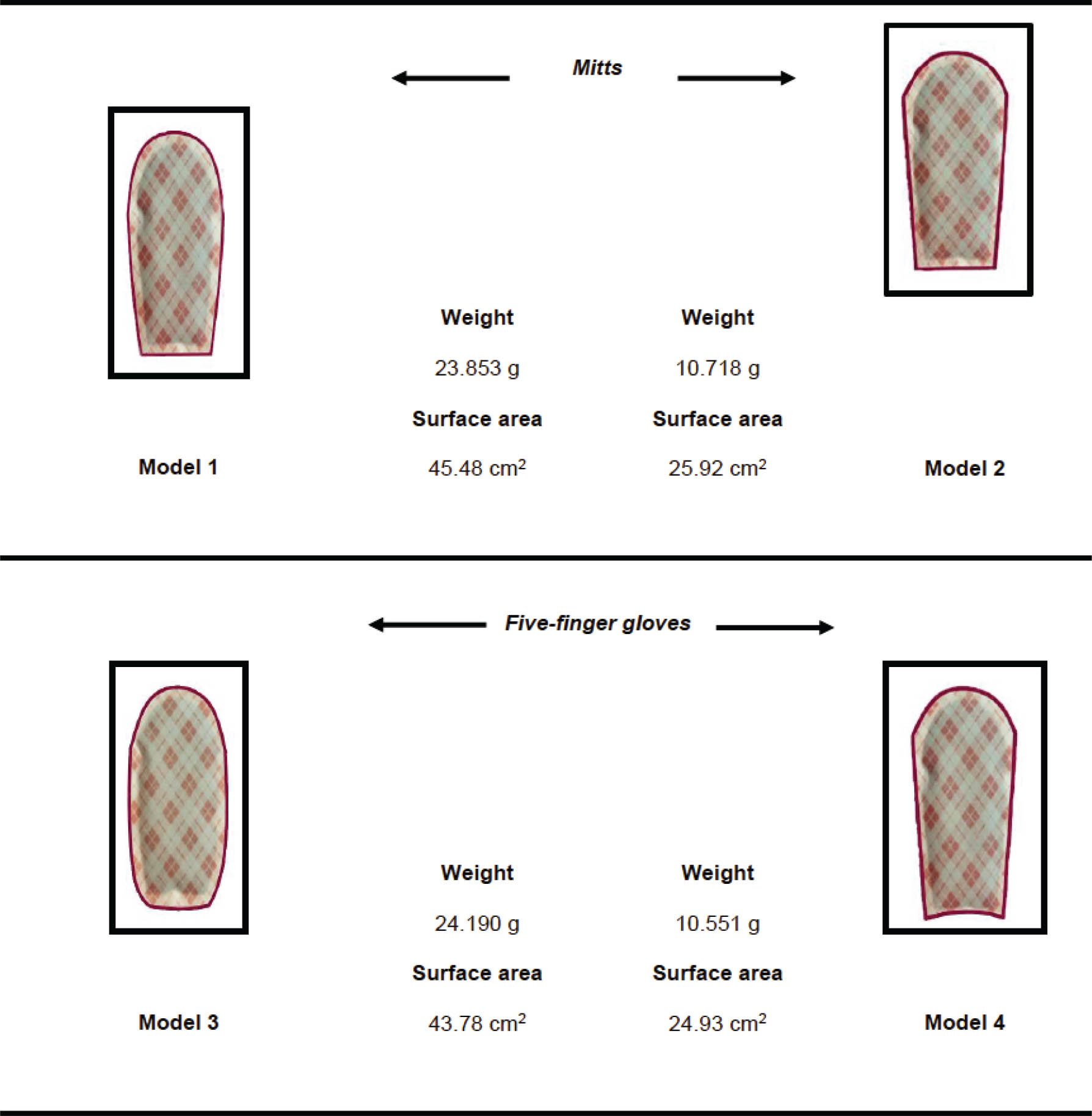

Protective gloves designed to improve the comfort of work in cold environments have been equipped with warmers containing mineral substances which release heat upon contact with air. Four models of warmers were tested (Table 2); they differed in shape and weight, and were tailored to the glove types in which they were implemented.

Models of warmers used in the tested gloves

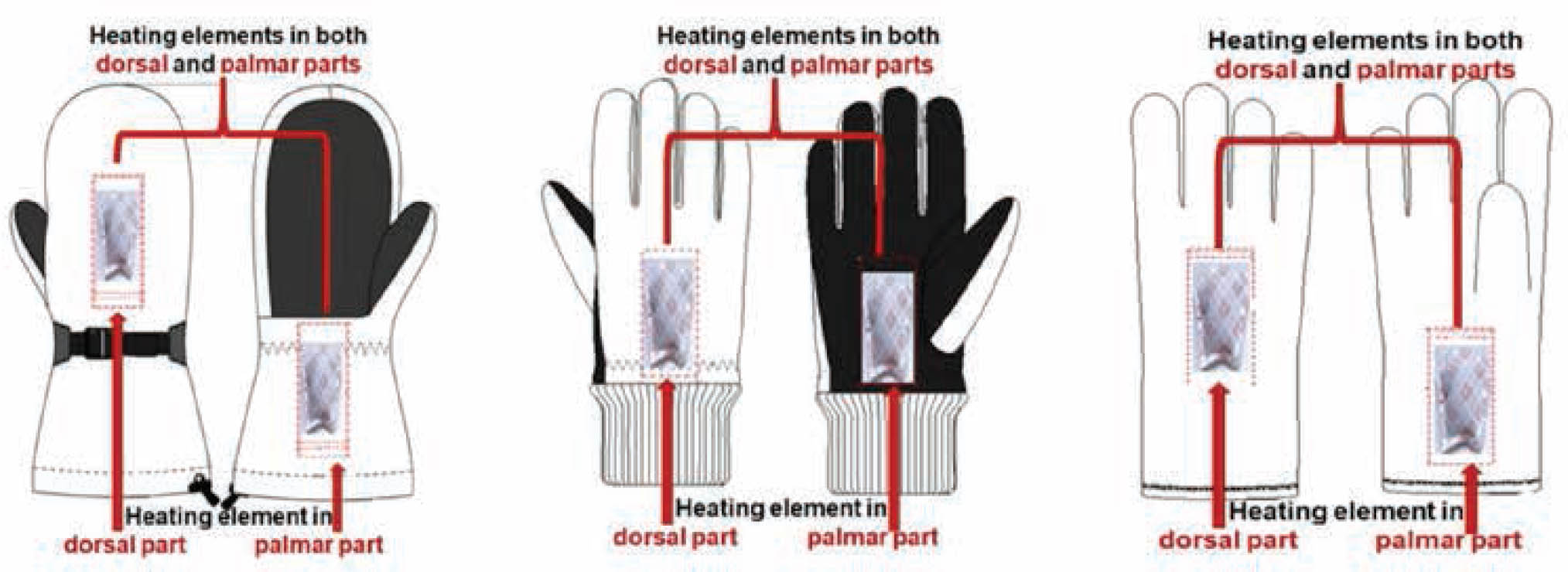

The tests were performed in two variants: with warmers and without them (as reference measurements). The warmers were integrated within designated pockets and placed:

in the palmar part of the gloves;

in the dorsal part of the gloves;

in both palmar and dorsal parts.

A schematic illustration of warmer location in the gloves is shown in Figure 1.

Schematic illustration of warmer location in the gloves.

2.2 Manual dexterity tests of cold-protective gloves with warmers

The study was conducted on a group of 10 professionally active men and included 5 manual dexterity tests as presented in Table 3. The first one is specified in the standard PN-EN 1082-2:2002 [32]. The second one is commercially available, but its application for assessing the ergonomic properties of gloves was proposed by the present authors, while the remaining three tests were originally developed by the authors and described in another work [33]. The tests were designed to approximate real conditions of the work environment, allow for simulation of occupational activities, and involved various aspects of manual dexterity.

List of applied manual dexterity tests

| Test | Manual dexterity test |

|---|---|

| TEST 1 | Cylinder grip and pull test for the evaluation of gross hand and arm movements |

| TEST 2 | Purdue Pegboard Test for the evaluation of fine finger movements |

| TEST 3 | Simulated occupational task of pulling aside for the evaluation of gross arm movements |

| TEST 4 | Simulated occupational task of holding down for the evaluation of gross hand movements |

| TEST 5 | Simulated occupational task of rotating for the evaluation of gross movements of the hands and arms |

The first manual test involved the gripping and pulling of a metal cylinder. The experimental apparatus consisted of a table with a cylinder equipped with a handle and connected to a dynamometer measuring the exerted force. During the test, the subjects stood at the table in a comfortable upright position, with one hand holding the cylinder handle. The subjects were asked to initially pull the cylinder with maximum force.

The second test evaluated hand and finger dexterity using the Purdue Pegboard consisting of two parallel rows with 25 holes in each. The subjects were asked to pick up pegs and place them in the holes during 30 s.

In the third test, the subjects stood erect at the experimental stand, looking at the proximal side of the pulley. They gripped the board with one hand, and then pulled it aside to a deflected position until a marker on the proximal side of the pulley became visible. In this test, the moment of force reflected muscle loading. The subjects were supposed to hold the board at the deflected position for 30 s, simulating occupational hand movements.

In test 4, the subjects also stood erect in front of the experimental stand. They placed one hand over the cart, at an angle of 45°, and positioned the three middle fingers on the indicated points. Subsequently, the subjects pushed the cart up to the designated marker. After 10 s, the experimenter measured finger displacement (the distance the subjects’ fingers moved along the surface of the cart in the process of holding it down).

During test 5, the subjects stood erect at the table with the measurement apparatus, holding the handle. Upon the experimenter’s signal, they started to drive in the handle by rotating it for 10 s. The initial handle setting was the same for all subjects.

2.3 Statistical analysis

Analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used with a posteriori Bootstrap resampling (1,000 replicates). Post hoc comparisons were made with the Bonferroni test. A 95% confidence interval [±2 standard deviation (SD)] for mean variable values was adopted. The measured values were consistent with normal distribution. Calculations were made using SPSS Statistics 23.0.

3 Results and discussion

Many studies have investigated the physiological effects of low temperatures and hand cooling, which significantly impair manual dexterity. To prevent that, thermal comfort may be maintained using multilayer systems of materials implemented in protective gloves. However, it is difficult to determine the optimum number of layers, given the fact that the heavier and thicker the resulting composite is, the more it tends to hinder manual dexterity and worker productivity [34]. This was also observed in the present study (Table 4) of holding down for the evaluation of gross hand movements. The results of the holding down test (Test 4) were not included in statistical analysis as they did not reveal differences between the studied glove designs or warmer parameters.

Analysis of variance (ANOVA) statistics for the effect of protective glove design on manual dexterity

| Protective glove design | Post hoc test | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variant 1 | Variant 2 | Variant 3 | F(2. 102) | p | ||||

| Test 1 | Maximum force [N] | M | 83.11 | 101.23 | 92.97 | 1 < 2 | 4.98 | p < 0.01 |

| SD | 27.21 | 22.13 | 22.48 | |||||

| Force maintained for 10 s [N] | M | 43.40 | 52.26 | 47.57 | 1 < 2 | 2.88 | p < 0.05 | |

| SD | 17.18 | 15.72 | 13.16 | |||||

| Test 2 | Number of pegs | M | 3.74 | 6.14 | 14.29 | 1 < 2,5 | 289.84 | p < 0.001 |

| SD | 1.54 | 1.80 | 2.33 | 2 < 5 | ||||

| Test 3 | Pulling away [s] | M | 26.94 | 27.80 | 27.14 | 0.41 | ns | |

| SD | 4.54 | 3.94 | 3.86 | |||||

| Test 5 | Driving in [mm] | M | 13.46 | 17.09 | 13.69 | 1 < 2 | 21.91 | p < 0.001 |

| SD | 1.56 | 2.92 | 2.97 | 2 > 5 | ||||

*The results of the holding down test (Test 4) were not included in statistical analysis as they did not reveal differences between the studied glove designs or warmer parameters.

Other authors who examined the effectiveness of electrically heated gloves in maintaining warm hands found that the users appreciated the advantages of such gloves in terms of higher thermal comfort and manual dexterity. Electrically heated gloves were also developed and evaluated with a view to alleviating the pain associated with constrained blood flow [35]. Research showed that such gloves had beneficial effects on individuals suffering from circulatory conditions [36]. Heating systems may maintain finger temperature at 22–25°C for 2–3 h during exposure to −15°C ambient air [37]. However, in the reviewed papers, hand skin temperature was measured at several isolated points on the surface of the hand under laboratory conditions, without a comprehensive evaluation of the hand as a whole, with manual dexterity being associated exclusively with hand skin temperature.

No works to date have evaluated the effects of the physical presence of an additional warmer in the glove structure on manual dexterity under real work conditions. The current results revealed some correlations between manual dexterity (comfort of use) and glove design as well as the shape (but not location) of the warmer. It was thus determined which warmers were optimum from the point of view of manual dexterity and comfort of use. Table 5 presents a summary of ANOVA statistics for the effect of warmer shape on manual dexterity in protective gloves.

Analysis of variance (ANOVA) statistics for the effect of warmer shape on manual dexterity in protective gloves

| Heating element shape | Post hoc test | F(4, 100) | p | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Without heating | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | ||||||

| Test 1 | Maximum force [N] | M | 114.60 | 81.20 | 77.87 | 96.80 | 89.90 | 0>1,2,3,4 | 6.41 | p < 0.001 |

| SD | 26.41 | 25.95 | 26.74 | 19.31 | 19.94 | |||||

| Force maintained for 10 s [N] | M | 67.93 | 40.60 | 38.93 | 48.37 | 45.00 | 0>1,2,3,4 | 11.88 | p < 0.001 | |

| SD | 22.34 | 12.98 | 13.37 | 9.68 | 9.93 | |||||

| Test 2 | Number of pegs | M | 7.20 | 3.40 | 4.13 | 10.47 | 10.37 | 1,2 < 3,4 | 13.98 | p < 0.001 |

| SD | 4.48 | 1.45 | 1.55 | 4.63 | 4.72 | |||||

| Test 3 | Pulling away [s] | M | 28.47 | 28.53 | 25.53 | 27.03 | 27.23 | - | 1.39 | ns |

| SD | 3.62 | 3.14 | 5.10 | 4.31 | 3.86 | |||||

| Test 5 | Driving in [mm] | M | 17.67 | 13.60 | 12.67 | 15.10 | 14.53 | 0>1,2,3,4 | 7.31 | p < 0.001 |

| SD | 3.46 | 1.24 | 1.11 | 3.09 | 3.00 | |||||

Finally, Table 6 presents ANOVA statistics for the effect of warmer location on manual dexterity in protective gloves (all variants). The tests did not reveal any statistically significant correlations for this parameter.

Analysis of variance (ANOVA) statistics for the effect of warmer location on manual dexterity

| Heating element location | Post hoc test | F(3. 86) | p | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dorsal | Dorsal and palmar | Palmar | ||||||

| Test 1 | Maximum force [N] | M | 93.87 | 85.37 | 87.00 | – | 1.18 | ns |

| SD | 23.51 | 22.01 | 22.82 | |||||

| Force maintained for 10 s [N] | M | 46.93 | 42.67 | 43.53 | – | 1.18 | ns | |

| SD | 11.74 | 11.01 | 11.39 | |||||

| Test 2 | Number of pegs | M | 7.77 | 8.23 | 8.60 | – | 0.21 | ns |

| SD | 5.04 | 5.04 | 5.05 | |||||

| Test 3 | Pulling away [s] | M | 27.97 | 26.40 | 26.93 | – | 1.10 | ns |

| SD | 3.56 | 4.30 | 4.54 | |||||

| Test 5 | Driving in [mm] | M | 14.47 | 14.00 | 14.30 | – | 0.23 | ns |

| SD | 2.60 | 2.77 | 2.78 | |||||

Statistical analysis showed a significant influence of glove design on manual dexterity: mitts were characterized by the lowest fine finger movement ability, while the other two glove variants did not impair user comfort in this respect. The location of the warmer did not exert a significant effect on manual dexterity in contrast to warmer shape, which was significant except for the pulling away task (Test 3). No differences were observed for warmer weight (Table 5). Higher values of maximum force, maintained force, and driving in distance were observed in the absence of a warmer (Tests 1, 2, and 5).

4 Conclusions

The final conclusions are as follows: the physical presence of a warmer in the glove structure in itself does not impair manual dexterity, but manual dexterity is significantly affected by the shape of the warmer.

Acknowledgments

The paper is based on the results of the COLDPRO project: “The use of active ecological mineral compounds in the production of cold-protective gloves and footwear” funded in the years 2015–2018 by the National Centre for Research and Development in Poland.

References

[1] Smith, J. C., Machado-Moreira, C. A., Plant, G., Hodder, S., Havenith, G., et al. (2013). Design data for footwear: sweating distribution on the human foot. International Journal of Clothing Science and Technology, 25(1), 43–58.10.1108/09556221311292200Search in Google Scholar

[2] Bertaux, E., Derler, S., Rossi, R. M., Zeng, X., Koehl, L., et al. (2010). Textile, physiological, and sensorial parameters in sock comfort. Textile Research Journal, 80(17), 1803–1810.10.1177/0040517510369409Search in Google Scholar

[3] Garner, J. C., Wade, C., Garten, R., Chander, H., Acevedo, E. (2013). The influence of firefighter boot type on balance. International Journal of Industrial Ergonomics, 43(1), 77–81.10.1016/j.ergon.2012.11.002Search in Google Scholar

[4] Geng, Q., Chen, F., Holmer, I. (1997). The effect of protective gloves on manual dexterity in the cold environments. International Journal of Occupational Safety and Ergonomics, 3(1–2), 15–29.10.1080/10803548.1997.11076362Search in Google Scholar

[5] Holmer, I. (1993). Work in the cold. International Archives of Occupational and Environmental Health, 65, 147–155.10.1007/BF00381150Search in Google Scholar

[6] Koradecka, D. (Ed.) (1997). Bezpieczeństwo Pracy i Ergonomia. CIOP (Warsaw, Poland).Search in Google Scholar

[7] Chen, F., Nilsson, H., Holmér, I. (1994). Finger cooling by contact with cold aluminium surfaces – effects of pressure, mass and whole body thermal balance. European Journal of Applied Physiology, 69(1), 55–60.10.1007/BF00867928Search in Google Scholar

[8] Geng, Q., Holmer, I. (2001). Change in contact temperature of finger touching on cold surfaces. International Journal of Industrial Ergonomics, 27(6), 387–391.10.1016/S0169-8141(01)00005-1Search in Google Scholar

[9] Kuklane, K. (2009). Protection of feet in cold exposure. Industrial Health, 47(3), 242–253.10.2486/indhealth.47.242Search in Google Scholar

[10] Kuklane, K., Geng, Q., Holmér, I. (1999). Thermal effects of steel toe caps in footgear. International Journal of Industrial Ergonomics, 23(5–6), 431–438.10.1016/S0169-8141(97)00074-7Search in Google Scholar

[11] Kuklane, K., Holmér, I. (1998). Effect of sweating on insulation of footwear. International Journal of Occupational Safety and Ergonomics, 4(2), 123–136.10.1080/10803548.1998.11076385Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[12] Gadd, P. R. (1996). Heated gloves. US Patent 5541388.Search in Google Scholar

[13] Cornwell, W. D. (1970). Electrically heated footwear and handwear. US 3621191.Search in Google Scholar

[14] Orban, R. F., Lewis, J. C. (1985). Electrically heated gloves. US 4764665.Search in Google Scholar

[15] Moss, G. J., Toler, M., Rehkemper, S. (1989). Heated gloves. US Patent 4950868.Search in Google Scholar

[16] Metcalf, E. K. (1975). Heated garment. US 3999037.Search in Google Scholar

[17] Davis, L. K., McCarthy, N. J. (1999). Disposable thermal body wrap. US 6336935.Search in Google Scholar

[18] Helenick, S. M. (1998). Thermal glove. US 6141801.Search in Google Scholar

[19] Langer, M. (2003). Climate controlled glove for sporting activities. US 2004/0244090A1.Search in Google Scholar

[20] Chen, Y.-G., Chen, J.-K. (2008). Cold/hot pack. US 2010/0016933A1.Search in Google Scholar

[21] Raleigh, G., Rivard, R., Fabus, S. (2005). Air activated chemical warming devices: effects of oxygen and pressure. Undersea and Hyperbaric Medicine Journal, 32(6), 445–449.Search in Google Scholar

[22] Kauranen, K., Vanharanta, H. (1997). Effects of hot and cold packs on motor performance of normal hands. Physiotherapy, 83(7), 340–344.10.1016/S0031-9406(05)65755-0Search in Google Scholar

[23] Okada, K., Yamaguchi, T., Minowa, K., Inoue, N. (2005). The influence of hot pack therapy on the blood flow in masseter muscles Journal of Oral Rehabilitation, 32, 7.10.1111/j.1365-2842.2005.01448.xSearch in Google Scholar PubMed

[24] Fearon, R. E., Foss, R. G. (1968). Exothermic composition containing a metal oxide and acid or acid salts US 3475239.Search in Google Scholar

[25] Jackman, R., Johnson, J. (1970). Exothermic composition US 3766079.Search in Google Scholar

[26] Krupa, C. S. (1975). Heating pack containing a granular chemical composition. US 3980070.Search in Google Scholar

[27] Gossett, R. L. (1974). Magnesium sulfate anhydrous hot pack having an inner bag provided with a perforated seal. US 4057047.Search in Google Scholar

[28] Miyashita, E. (1987). Hot compress structure. US 5233981.Search in Google Scholar

[29] Cramer, R. D., Davies, L. K., Ouellette, W. R. (1996). Disposable thermal body pad. US 6096067.Search in Google Scholar

[30] Davis, L. K., Cramer, R. D., Ouellette, W. R., Kimble, D. M. (1996). Thermal pack having a plurality of individual heat cells. US 6146732.Search in Google Scholar

[31] Sands, W. A., Kimmel, W. L., Wurtz, B. R., Stone, M. H., McNeal, J. R. (2009). Comparison of commercially available disposable chemical hand and foot warmers. Wilderness and Environmental Medicine, 20, 33–38.10.1580/08-WEME-OR-243.1Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[32] PN-EN 1082-2:2002 Odzież ochronna - Rękawice i ochrony ramion chroniące przed przecięciami i ukłuciami nożami ręcznymi - Część 2: Rękawice i ochrony ramion wykonane z materiałów innych niż plecionka pierścieni.Search in Google Scholar

[33] Irzmańska, E., Tokarski, T. (2017). A new method of ergonomic testing of gloves protecting against cuts and stabs during knife use. Applied Ergonomics, 61, 102–114.10.1016/j.apergo.2017.01.002Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[34] Dorman, L. E., Havenith, G. (2009). The effects of protective clothing on energy consumption during different activities. European Journal of Applied Physiology, 105(3), 463–470.10.1007/s00421-008-0924-2Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[35] Kempson, G. E., Clark, R. P., Goff, M. R. (1988). The design, development and assessment of electrically heated gloves used for protecting cold extremities. Ergonomics, 31(7), 1083–1091.10.1080/00140138808966746Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[36] Haisman, M. F. (1988). Physiological aspects of electrically heated garments. Ergonomics, 31(7), 1049–1063.10.1080/00140138808966744Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[37] Brajkovic, D., Ducharme, M. B., Frim, J. (1998). Influence of localized auxiliary heating on hand comfort during cold exposure. Journal of Applied Physiology, 85(6), 2054–2065.10.1152/jappl.1998.85.6.2054Search in Google Scholar PubMed

© 2021 Emilia Irzmańska et al., published by Sciendo

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Photostability of TiO2-Coated Wool Fibers Exposed to Ultraviolet B, Ultraviolet A, and Visible Light Irradiation

- Chemical Hand Warmers in Protective Gloves: Design and Usage

- The Removal of Reactive Red 141 From Wastewater: A Study of Dye Adsorption Capability of Water-Stable Electrospun Polyvinyl Alcohol Nanofibers

- A Review of Contemporary Techniques for Measuring Ergonomic Wear Comfort of Protective and Sport Clothing

- Experimental Study on Dyeing Performance and Antibacterial Activity of Silver Nanoparticle-Immobilized Cotton Woven Fabric

- Sewing Thread Consumption for Chain Stitches of Class 400 using Geometrical and Multilinear Regression Models

- The Status of Textile-Based Dry EEG Electrodes

- Comprehensive Assessment of the Properties of Cotton Single Jersey Knitted Fabrics Produced From Different Lycra States

- Prognosticating the Shade Change after Softener Application using Artificial Neural Networks

- Influence of the Structure of Seersucker Woven Fabrics on their Friction Properties

- Evaluation of Cochlospermum vitifolium Extracts as Natural Dye in Different Natural and Synthetic Textiles

- Homogeneous Coatings of Titanium Dioxide Nanoparticles on Corona-Treated Cotton Fabric for Enhanced Self-Cleaning and Antibacterial Properties

- Numerical Analysis of Large Deflections of a Flat Textile Structure with Variable Bending Rigidity and Verification of Results Using Fem Simulation

- Thermal Behavior of Aerogel-Embedded Nonwovens in Cross Airflow

- Kansei Engineering as a Tool for the Design of Traditional Pattern

Articles in the same Issue

- Photostability of TiO2-Coated Wool Fibers Exposed to Ultraviolet B, Ultraviolet A, and Visible Light Irradiation

- Chemical Hand Warmers in Protective Gloves: Design and Usage

- The Removal of Reactive Red 141 From Wastewater: A Study of Dye Adsorption Capability of Water-Stable Electrospun Polyvinyl Alcohol Nanofibers

- A Review of Contemporary Techniques for Measuring Ergonomic Wear Comfort of Protective and Sport Clothing

- Experimental Study on Dyeing Performance and Antibacterial Activity of Silver Nanoparticle-Immobilized Cotton Woven Fabric

- Sewing Thread Consumption for Chain Stitches of Class 400 using Geometrical and Multilinear Regression Models

- The Status of Textile-Based Dry EEG Electrodes

- Comprehensive Assessment of the Properties of Cotton Single Jersey Knitted Fabrics Produced From Different Lycra States

- Prognosticating the Shade Change after Softener Application using Artificial Neural Networks

- Influence of the Structure of Seersucker Woven Fabrics on their Friction Properties

- Evaluation of Cochlospermum vitifolium Extracts as Natural Dye in Different Natural and Synthetic Textiles

- Homogeneous Coatings of Titanium Dioxide Nanoparticles on Corona-Treated Cotton Fabric for Enhanced Self-Cleaning and Antibacterial Properties

- Numerical Analysis of Large Deflections of a Flat Textile Structure with Variable Bending Rigidity and Verification of Results Using Fem Simulation

- Thermal Behavior of Aerogel-Embedded Nonwovens in Cross Airflow

- Kansei Engineering as a Tool for the Design of Traditional Pattern