Abstract

This study is to investigate the role of the coating of TiO2 nanoparticles deposited on wool fibers against high-intensity ultraviolet B (UVB), ultraviolet A (UVA), and visible light irradiation. The properties of tensile and yellowness and whiteness indices of irradiated TiO2-coated wool fibers are measured. The changes of TiO2-coated wool fibers in optical property, thermal stability, surface morphology, composition, molecular structure, crystallinity, and orientation degree are characterized using diffuse reflectance spectroscopy, thermogravimetric analysis, scanning electronic microscopy, energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy, Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy, and X-ray diffraction techniques. Experimental results show that the tensile properties of anatase TiO2-coated wool fibers can be degraded under the high-intensity UVB, UVA, and visible light irradiation for a certain time, resulting in the loss of the postyield region of stress–strain curve for wool fibers. The coating of TiO2 nanoparticles makes a certain contribution to the tensile property, yellowness and whiteness indices, thermal stability, and surface morphology of wool fibers against high-intensity UVB, UVA, and visible light irradiation. The high-intensity UVB, UVA, and visible light can result in the photo-oxidation deterioration of the secondary structure of TiO2-coated wool fibers to a more or less degree. Meanwhile, the crystallinity and orientation degree of TiO2 coated wool fibers decrease too.

1 Introduction

It is well-known that the prolonged exposure of wool fibers to sunlight, particularly ultraviolet (UV) rays, can result in the photo-yellowing, photo-tendering, and photo-degradation of wool [1]. Consequently, an increase in surface roughness and loss of mechanical strength of wool fibers will happen [2], which are greatly influenced by the wavelength of incident radiation [3]. The visible light radiation in sunlight causes the photo-bleaching of wool, while the UV irradiation causes the photo-yellowing [4]. The resulting changes of irradiated wool in color, physical, and chemical properties are mainly attributed to the cleavage of peptide and disulfide bonds, the oxidation or elimination of small molecules, and the formation of new cross-links [5]. It has been reported that the short-wave ultraviolet C (UVC, 200–280 nm) radiation selectively oxidizes the surface of wool fibers to produce thiol and S-sulfonate

Some pioneering studies show that the photo-yellowing and photo-tendering of wool are primarily caused by the higher energy UV rays below 310 nm. On the contrary, others claim that the most effective yellowing waves are either in 340–420 or 320–400 nm region [9, 10]. It is generally recognized that the chromophores absorbing between 250 and 320 nm region exist in the form of aromatic amino acid residues, for example, tryptophan, tyrosine, phenylalanine, and cystine [11]. These photo-induced chromophores are derived from tryptophan and tyrosine of wool keratins [12]. It has been demonstrated that UV rays make wool surface damage to some extent in a short time, whereas the inner cortical components are impaired in prolonged exposure [13]. Moreover, the photo-yellowing of the wool cuticle is much more easily noticeable than that of cortical fibrils [14]. The photo-stabilities of wool fabrics modified with helium gas plasma, papain enzyme, acylation and acid anhydride, and permanganate oxidation under the long-wave ultraviolet A (UVA; 320–400 nm) and short-wave ultraviolet B (UVB; 280–320 nm) rays, and blue light irradiation are highly dependent upon the modification type [15]. More recently, the photo-yellowing mechanisms of wool and the current strategies for improving wool's photostability have been systemically summarized [16].

The photo-degradation prevention treatments of wool have been extensively investigated using organic polymeric UV absorbers [17,18,19] and inorganic UV blockers, such as TiO2 [20, 21] and ZnO [22, 23], or by dyeing and mordanting with alum and ferrous sulfate [24] in recent years. As an ideal semiconductor photocatalyst, anatase titanium dioxide (TiO2) nanoparticles are of great interest because of their impressive features, such as nontoxicity, physicochemical stability, good reflective, UV absorption ability, and high photocatalytic reactivity [25]. According to the solid band theory, there are two likely reaction mechanisms of TiO2, which acts as UV-blocking additive, under UV rays for the consumption of generated active species: they can react with other active electrons and holes and then being trapped by the absorbents surrounding TiO2 and initiating a series of reduction and oxidation reactions [26]. For instance, to gain the anti-shrinkage [27], self-cleaning [28], anti-UV [29], antibacterial [30], and moth-proofing properties [31, 32], wool fabrics or fibers have been treated with nano-TiO2 sol in combination with chitosan and polycarboxylic acid [33] to increase the binding force of TiO2 nanoparticles on wool surface, or with TiO2 sol and poly(sodium 4-styrene-sulfonate) [34] by layer-by-layer self-assembly technology. The UV exposure experiments reveal the photo-oxidation, and hence the degree of photo-yellowing of wool keratin is significantly determined by the dose of absorbed UV radiation [35] and the concentrations of TiO2 [36]. The alkali solubility of the nano-TiO2-coated wool fabrics can be reduced while the fabric becomes more hydrophilic [37]. TiO2 nano-photo-bleaching has been applied to the scoured and protease pretreated wool fabrics; thus, the improved whiteness index and hydrophilicity can be obtained [38].

More previous studies have reported that the wool fabric has been fabricated by in situ synthesis of N-doped TiO2 under ultrasound irradiation [39]. The polyester/wool blended fabric has been treated with proteases and lipases [40] or oxygen plasma [41] to enhance the anchoring of nano-TiO2 on the fabric surface. TiO2 nanoparticles co-doped with nonmetal/metal have been deposited on the surface of photo sono-treated wool fabric using titanium isopropoxide, silver nitrate, and ammonia [42]. Research has been undertaken to reduce the photocatalytic activity of TiO2 by depositing a layer of SiO2 shell on TiO2 nanoparticles, which are anchored on wool fabrics to improve the photo-yellowing of the wool [43].

However, it is worth mentioning that the radiation wavelength and dose relating to tensile and yellowness and whiteness of wool fibers are missing in most previous studies. Also, little is known about the effects of high-intensity short-wave UVB and long-wave UVA rays on the structure of wool fibers. Although TiO2 has been widely used as inorganic UV blockers, the influences of TiO2 coating on the properties of wool fibers have not been investigated in detail except a few studies [44]. The purpose of this study is to clarify whether the coating of TiO2 nanoparticles could protect wool fibers from the prolonged exposure to high-intensity UVB, UVA, and visible light. The influences of UVB, UVA, and visible light on various tensile, yellow and white indices, morphology, molecule structure, crystallinity, orientation, and thermal stability of TiO2-coated wool fibers are discussed.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Materials

The 80s Merino wool fibers were friendly provided by Shandong Ruyi Technology Group Co., Ltd., in China. The average linear density of the as-obtained wool fibers was measured to be 3.48 ± 0.04 dtex. The chemical reagents were of analytical grade and included tetraisopropyl titanate ((CH3CH3CHO)4Ti, CAS: 546-68-9), sodium carbonate (Na2CO3), anhydrous ethanol (CH3CH2OH), and acetone (CH3COCH3). The deionized water was used in the whole experiment.

2.2 Fabrication of TiO2-coated wool fibers

The TiO2-coated wool fibers were prepared by immobilizing of TiO2 nanoparticles on wool fibers using tetraisopropyl titanate as the precursor under hydrothermal condition. Before modification with TiO2, according to the material-to-liquor ratio of 1:20, 5 g of wool fibers was first immersed in 100 ml of sodium carbonate (2 g/l) aqueous solution at 50°C for 120 min and then dipped successively into deionized water, acetone, and anhydrous ethanol solution at 50°C for 10 min, followed by washing with deionized water thrice and finally dried in an oven at 50°C. Next, 0.5 ml of tetraisopropyl titanate was completely dissolved in 10 ml of anhydrous ethanol solution at room temperature, and 70 ml of deionized water was then added under vigorous magnetic stirring. The pretreated wool fibers (0.5 g) were soaked in the above mixture solution at ambient temperature for 10 min. The wool fibers along with the suspension were subsequently transferred into a 100-ml polytetrafluoroethylene reaction vessel, which was enclosed in a stainless steel tank. The tank was set in a reactor and was run at a speed of 60 rpm. At the same time, it was heated up to 110°C at a heating rate of 2°C/min and kept for 1.5 h at 110°C. After that, the wool fibers were washed alternately twice with deionized water and anhydrous ethanol at room temperature for 10 min each time and finally dried at 50°C. The original and tetraisopropyl titanate hydrothermal-treated wool fibers were designated as W1 and W2 specimens, respectively.

2.3 Wool fibers exposed to UVB, UVA, and visible light irradiation

The laboratory-accelerated irradiation testing was employed to assess the effect of TiO2 coating on the structure and properties of wool fibers under three high-intensity radiation sources, namely UVB ray (280–320 nm), UVA ray (320–400 nm), and visible lights. The erythemally weighted UV irradiance (or DUV) was typically around 0.025 mW/cm2 in midday summer sunlight; thus, a Philips TL18W/10 UVB lamp (20 W) with the main wavelength of 365 nm was used to produce the long-wave UVA rays, and its irradiance was measured to be 0.26 mW/cm2 by a TM-213 UV meter (Tenmars Electronics Co., Ltd., Taiwan), which is about 10 orders of magnitude larger than that of the DUV. Meanwhile, to cause greater damage to wool fibers, three Philips TL 20W/01 lamps (20 W for each) with the main wavelength of 311 nm were used to produce high energy short-wave UVB rays, and its irradiance was measured to be 0.7 mW/cm2. For visible light irradiation, a metal halide light (800 W) was used to simulate the visible light and UV rays were blocked out by the UV filter. The luminous intensity was measured to be 59,500 lx by a TES-1332A digital light meter (TES Electrical Electronic Corp., Taiwan). A thin layer of wool fibers was exposed to UVB, UVA, and visible light irradiation for a specific period of time. The distances between irradiation sources and wool fibers were set at 10 cm. To explore the effects of irradiation intensity on the tensile properties, the wool fibers were exposed to one (0.49 mW/cm2), two (0.62 mW/cm2), and three (0.7 mW/cm2) UVB lamps for 48 h.

2.4 Measurement and characterization

2.4.1 Measurement of tensile property

The tensile properties of wool fibers were performed on a YG(B)006 electric single fiber strength machine (Ningbo Textile Instrument Factory, China) at a constant rate of 10 mm/min in accordance with ISO 5079:1996 standard. The clamping length was 10 mm and the pretension was 0.1 cN. The mean values were calculated by measuring more than 300 wool fibers to ensure a 95% confidence level.

2.4.2 Measurements of yellowness and whiteness indices

The yellowness and whiteness indices of wool fibers were conducted on a Datacolor SF300 spectrophotometer according to the ASTM E-313 standard. CIE standard illuminant D65 with 10° observer was used. The average values were recorded by measuring five independent measurements.

2.4.3 Optical property analysis

The diffuse reflectance spectra of wool fibers were recorded on a Perkin-Elmer Lambda 950 UV–vis–NIR spectrophotometer using an integrating-sphere accessory over the range of 200–800 nm at a scanning speed of 600 nm/min.

2.4.4 Thermal property analysis

According to the ASTM E537-2002 standard, the thermal stability of wool fibers was obtained on a TGA Q500 thermogravimetric analyzer (TGA; TA Instruments) in the temperature range of 40–600°C at a nitrogen flow rate of 40 ml/min and a heating rate of 10°C/min.

2.4.5 Scanning electronic microscopy observation

The morphologies of wool fibers were observed using a Zeiss Merlin Compact field emission scanning electron microscope (FE-SEM) with an acceleration voltage of 10 kV.

2.4.6 Energy-dispersive X-ray analysis

The chemical compositions of wool fibers were analyzed by an energy-dispersive X-ray (EDX) spectroscopy attached to the FE-SEM.

2.4.7 Frontie Fourier-transform infrared analysis

The molecular structures of wool fibers were determined using Perkin-Elmer Spotlight 400 and Frontie Fourier-transform infrared (FT-IR) imaging system based on the attenuated total refraction mode in the wavenumber range of 650–4,000 cm−1 at a resolution of 4 cm−1.

2.4.8 X-ray diffraction analysis

The crystal structures of wool fibers were investigated on a D/Max-Rapid II micro-X-ray diffractometer (Rigaku Corporation, Japan) using Cu Kα radiation (40 kV, 200 mA, exposure 800 s). The crystallinity index (CI) (%) of wool fibers was calculated by the following Eq. (1) based on Segal's empirical formula [7]:

where I9° and I14° are the diffraction intensities at the 2θ of 9° and 14°, respectively.

According to the azimuth diffraction pattern of the I9° crystal face, the orientation degree [45], y, of wool fibers in the range of 0–180° was calculated by the following Eq. (2):

where HW is the full width at half maximum of the diffraction peak.

3 Results and discussion

3.1 Tensile property

The representative stress–strain curves abstracted from the mean values of more than 30 wool fibers (not given) show that all fiber specimens before and after exposure to irradiation have the similar typical stress–strain curves. They are almost overlapped in the initial stress–strain region, which obeys the Hook's law. In the stress–strain plastic region, the stress values of wool fibers decrease to various degrees after being irradiated by UVB, UVA, and visible light irradiation. The W2 specimens’ behavior is a little better than the W1 specimens primarily because of the coating of TiO2 nanoparticles. However, in the stress–strain postyield region, the irradiated W1 and W2 specimens are broken down more quickly than the unexposed ones, meaning the cleavage of the molecular chains of wool proteins induced by UV rays or visible light irradiation [7]. Importantly, the prolonged exposure to UVB/UVA rays or visible light would accelerate the photoaging of wool fibers, especially for UVB rays.

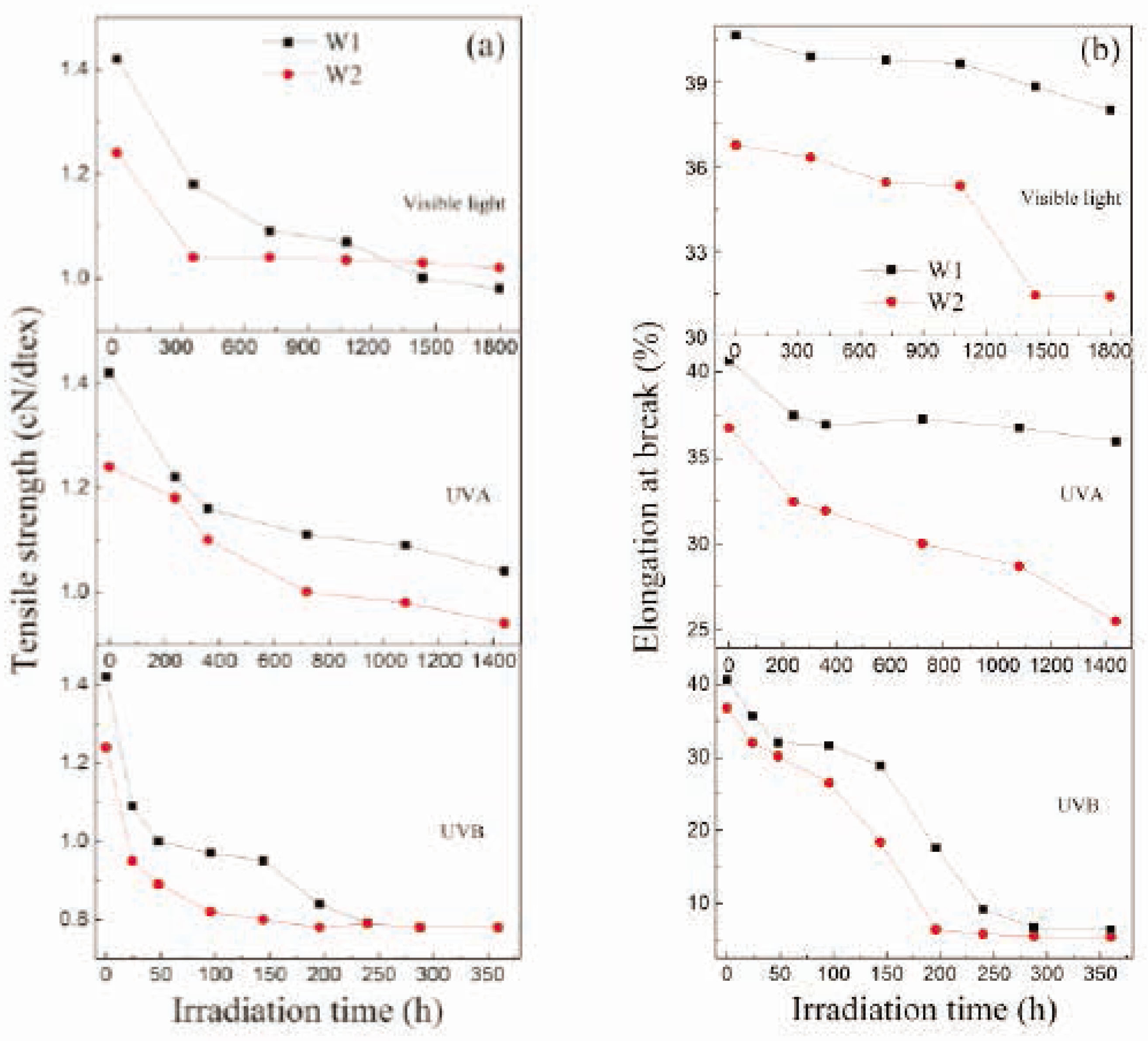

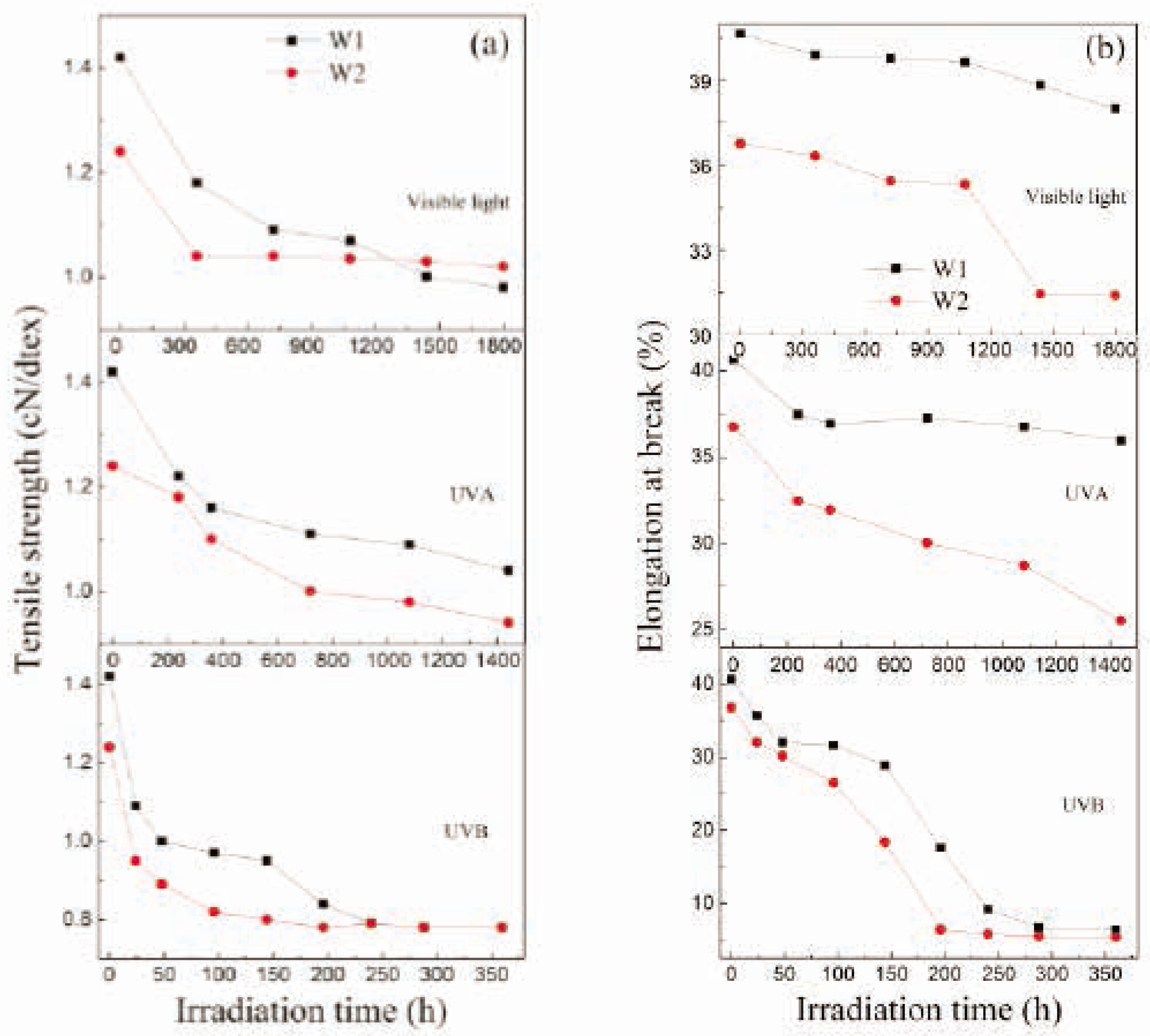

3.1.1 Effects of irradiation time on tensile strength and elongation at break

The tensile strength and elongation at break of wool fibers are reduced from 1.42 to 1.24 cN/dtex and from 40.7 to 36.8% after being coated with TiO2, which is mainly attributed to the hydrothermal treatment using hot pressurized water [46] and tetraisopropyl titanate. The impacts of irradiation time on the tensile strength of wool fibers exposed to UVB (0.7 mW/cm2), UVA (0.26 mW/cm2), and visible light (59,500 lx) irradiation are shown in Figure 1A. It is clear that the tensile strengths of W1 and W2 specimens decrease quickly along with the irradiation times at first and then slowly decrease with the increase in irradiation times. It has been demonstrated that the amount of α-helical keratin in wool can be reduced to some extent due to the radiation-induced thermal denaturation, which influences the strain-induced α–β transformation, and hence the loss of tensile strength of wool fibers occurs [5]. The UVB rays lead the most serious damage to tensile strength of wool fibers in a short time, even though their surfaces are coated with TiO2 nanoparticles in comparison with the UVA rays and visible light. This is because of the very high energy of photons and the large irradiation intensity of UVB rays. The tensile strengths of the W2 specimens decrease by 37% after 196 h of UVB, 20% after 1,440 h of UVA, and 18% after 1,800 h of visible light irradiation, which are smaller than the corresponding values of W1 specimens (41% for UVB, 44% for UVA, and 50% for visible light irradiation). But for the long-term UVB rays irradiation over 240 h, the tensile strengths for both W1 and W2 specimens reach the same value 0.78 cN/dtex.

The impacts of irradiation time on (A) tensile strength and (B) elongation at break for wool fibers.

The impacts of irradiation time on the elongation at break for wool fibers exposed to UVB (0.7 mW/cm2), UVA (0.26 mW/cm2), and visible light (59,500 lx) irradiation are shown in Figure 1B. It is evident that as the irradiation times increase, the elongations at break for both fiber specimens decrease under UVB, UVA, and visible light irradiation. The decreased rates of the W1 and W2 specimens exposed to UVB rays are much faster than those exposed to UVA rays and visible light. So, the results imply that the coating of TiO2 nanoparticles plays a certain role in protecting the tensile properties of wool fibers against high-intensity UVB, UVA, and visible light irradiation during a period of time.

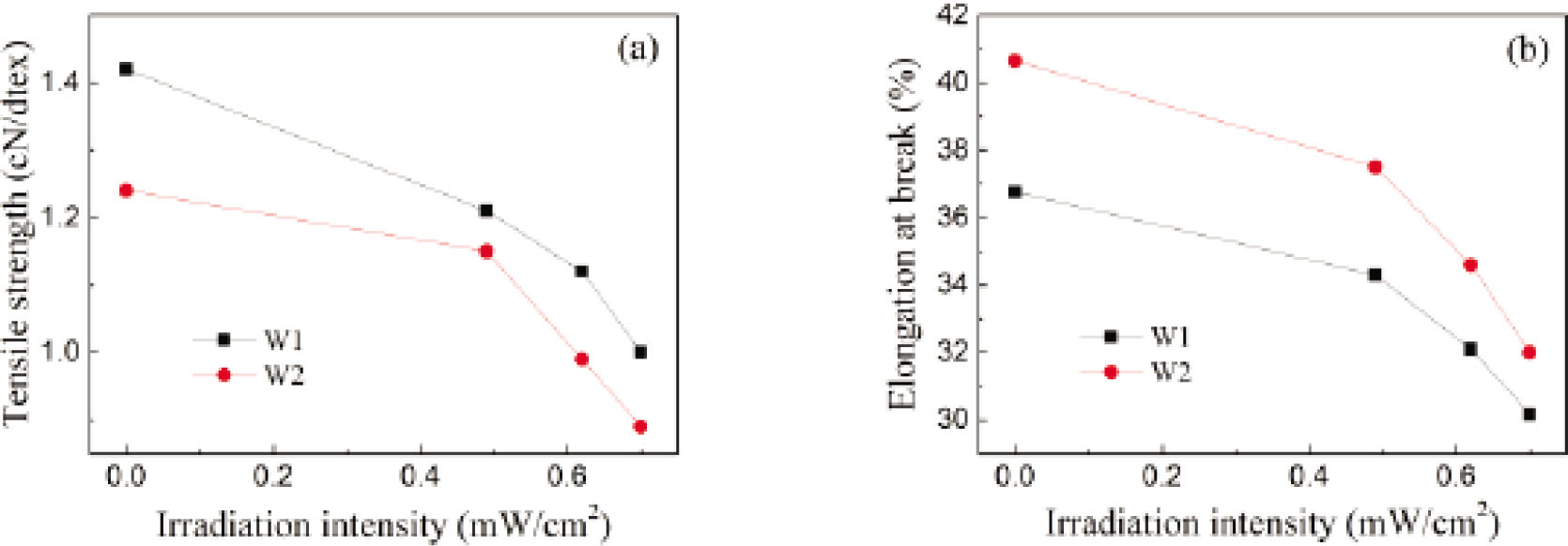

3.1.2 Effect of irradiation intensity

The effects of irradiation intensity on the tensile properties of wool fibers exposed to three different UVB irradiations for 48 h are shown in Figure 2. It is obvious that after the identical exposure time, the tensile strength and elongation at break for both fiber specimens decrease along with the increase in irradiation intensity, which is resulted from the more high energy photons of UVB rays. Namely, the higher the irradiation intensity of UVB rays, the more serious TiO2-coated wool fibers are suffered to damage.

The impacts of irradiation intensity on (A) tensile strength and (B) elongation at break for wool fibers exposed to UVB rays for 48 h.

3.2 Yellowness and whiteness indices

The impacts of irradiation time on the yellowness index of wool fibers under UVB, UVA, and visible light irradiation are shown in Figure 3A. The yellowness index of wool fibers increases slightly from 17.8 to 18.1 after being coated with TiO2. It is noticed that the high-intensity UVB rays have a great influence on the yellowness indices of wool fibers. The yellowness indices increase quickly with the increase in irradiation time. This is because of the formation of yellow chromophores derived from tryptophan and tyrosine oxidation products [47]. However, the W2 specimens’ behavior is much better than the W1 specimens mainly due to the TiO2 coating. On the contrary, the UVA rays have almost no obvious influence on the yellowness indices of wool fibers whether they are coated with TiO2 nanoparticles or not. It means that the UVA rays cannot destroy the chromophores of wool. For visible light, the yellowness indices for the W1 and W2 specimens have negligible changes with the increase in irradiation time.

The impacts of irradiation time on (A) yellowness indices and (B) whiteness indices for wool fibers.

The impacts of irradiation time on the whiteness index of wool fibers when exposed to UVB, UVA, and visible light irradiation are shown in Figure 3B. After treatment with tetraisopropyl titanate, the whiteness index of wool fibers decreases from 57.9 to 54.1. It is noted that the whiteness indices for both W1 and W2 specimens decrease sharply with the increasing irradiation time under UVB irradiation. The W2 specimens’ behavior is much better than the W1 specimens. Similarly, the UVA rays and visible light have little influence on the whiteness indices of wool fibers, except the whiteness index of the W2 specimens, which increase slightly at the late period of UVA irradiation primarily because of the photo-bleaching of TiO2 [38]. Therefore, the results confirm that the TiO2 film makes a little contribution to the photo-yellowing of wool fibers against UVB rays.

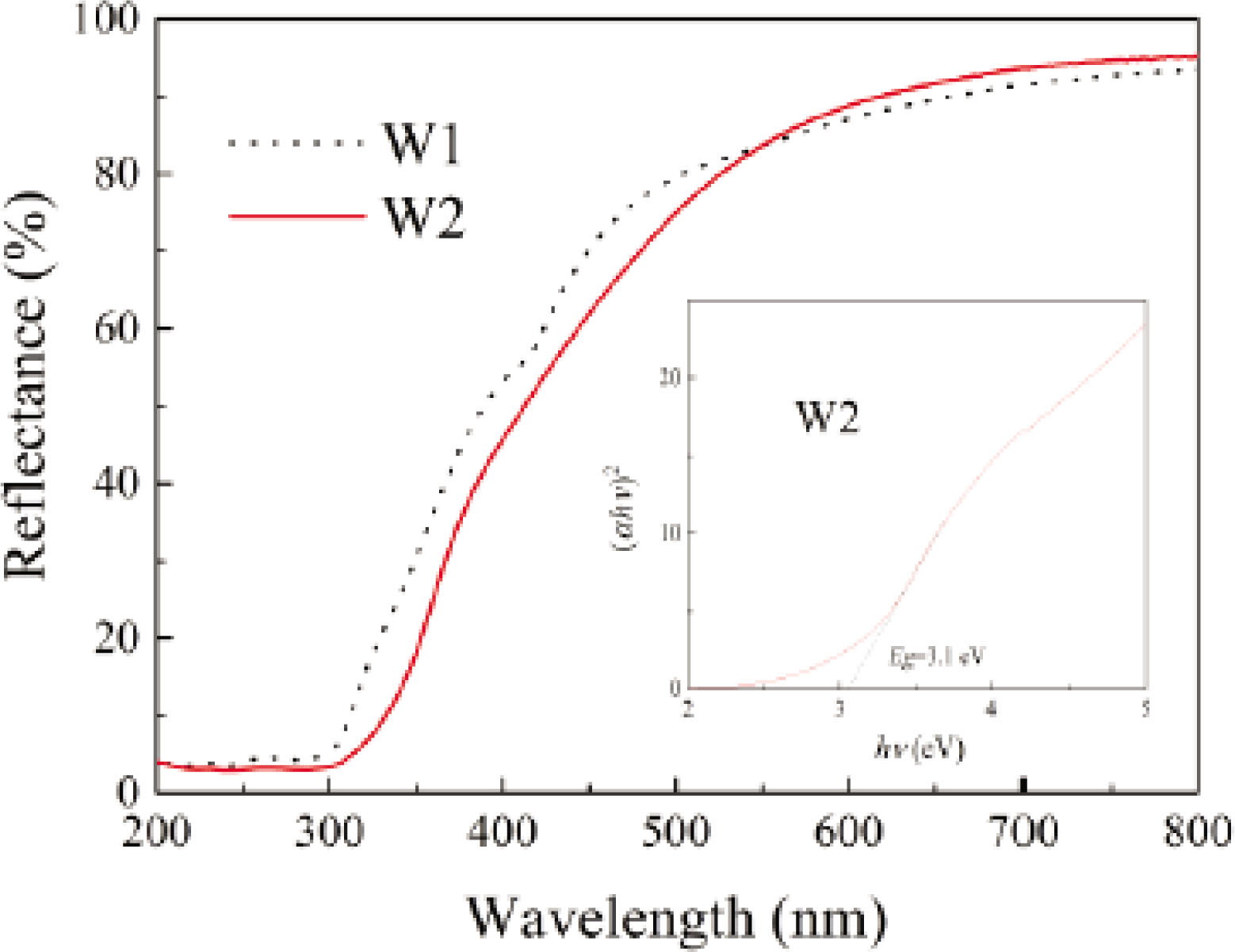

3.3 Optical property

The diffuse reflectance spectra of wool fibers are shown in Figure 4. It is observed that the W1 specimens can absorb UV rays and visible light to some extent, which are associated with the UV- and visible-absorbing chromophores, such as cystine, tryptophan, tyrosine, phenylalanine, and yellow oxidation products [48]. When the wool fibers are treated with tetraisopropyl titanate under the hydrothermal condition, the capability of absorbing UV rays and visible light is slightly improved. The optical absorption edge extends to visible light region owing to the coating of TiO2 nanoparticles. It has been confirmed that the co-doping of carbon, nitrogen, oxygen, and sulfur in the TiO2-modified wool fibers acts as a trapping center for electrons and holes, thereby reducing the recombination rate of charge carriers [49]. The relationship between (αhν)2 and incident photon energy (hν) for the W2 specimens is shown in Figure 5, where α is the absorption coefficient. The bandgap of the TiO2-coated wool fibers is estimated as 3.1 eV, which is smaller than 3.2 eV of the theoretical value of anatase TiO2 [39].

Diffuse reflectance spectra of wool fibers.

3.4 Thermal stability

The TGA/DTG curves of wool fibers before and after exposure to UVB (0.7 mW/cm2), UVA (0.26 mW/cm2), and visible light (59,500 lx) irradiation are shown in Figure 5. It is found that the thermal decomposition for all wool fibers can be classified into two degradation periods. The first thermal degradation period occurred at below 100°C is ascribed to the removal of surface absorbed water and residual water molecules in wool fibers and TiO2 particles. The second thermal degradation period is principally located in the region of 200–500°C, resulting from the decomposition of long polypeptide chains of keratin proteins [27]. When wool fibers are irradiated by UV rays or visible light for specific times, the maximum thermal decomposition temperatures increase about 9–∼11°C from 305°C for the W1 specimens and 2–∼4°C from 314°C for the W2 specimens. UV or visible light irradiation causes the breakdown of long polypeptide chains of keratin proteins to some extent. After irradiation, the onset decomposition temperatures of the W1 specimens decrease from 245 to 234°C for 360 h of UVB, 243°C for 1,440 h of UVA, and 241°C for 1,800 h of visible light. The corresponding relative masses are shifted from 26.3 to 65.1% for 360 h of UVB, 29.7% for 1,440 h of UVA, and 18.5% for 1,800 h of visible light. As for the W2 specimens, the onset decomposition temperatures increase about 3–∼6°C from 242°C. The corresponding relative masses increase from 21.5 to 28.1% for 360 h of UVB, 24.8% for 1,440 h of UVA, and 22.9% for 1,800 h of visible light. So the TGA/DTG results suggest that the coating of TiO2 nanoparticles makes a certain contribution to the thermal properties of wool fibers against UVB, UVA, and visible light irradiation.

TGA/DTG curves of (A) W1 and (B) W2 wool fibers.

3.5 Surface morphology

The scanning electronic microscopy (SEM) images of surface morphology for wool fibers exposed to UVB (0.7 mW/cm2), UVA (0.26 mW/cm2), and visible light (59,500 lx) irradiation at a specific time are shown in Figure 6. As shown in Figure 6A, the unexposed W1 specimens have the typical overlapping cuticle scales and their complex surfaces are dotted with some small organic fragments. After 360 h of UVB irradiation, many small cracks are formed on fiber surfaces due to the bombardment of high-energy UVB photons. When the W1 specimens are exposed to UVA rays for 1,440 h, a few tiny cracks are observed on fiber surfaces. That is induced by the breaking of inter- and intra-chains bonds as well as the chain reactions of carbonyl radicals [50]. Under 1,800 h visible light irradiation, besides very few of crevices, several fragments are attached to fiber surfaces.

SEM images of (A) W1-untreated and (B) W2-treated wool fibers.

As illustrated in Figure 6B, a layer of particulate matter is deposited on the surfaces of the unexposed W2 specimens. The high-resolution SEM image indicates that these particulates are constituted with nano- and sub-meter-sized particles. Under 360 h UVB irradiation, the wool scales are well preserved and the TiO2 particles are maintained on fiber surfaces. After 1,440 h of UVA rays and 1,800 h of visible light irradiation, both fiber specimens have no distinct changes in their appearances and their scales are also kept intact. Thus, the coating of TiO2 nanoparticles on fiber surfaces can withstand the photocorrosion of high-intensity UVB and UVA irradiation for a long time.

3.6 Chemical composition

The chemical compositions of wool fibers before and after exposure to UVB (0.7 mW/cm2), UVA (0.26 mW/cm2), and visible light (59,500 lx) irradiation are summarized in Table 1. In the case of the W1 specimens, the carbon contents increase when exposed to UVB/UVA or visible light irradiation for specific times, whereas the oxygen contents decrease to some extent. Also, the nitrogen content decreases under UVB and UVA irradiation, but it increases slightly under visible light irradiation. Conversely, the sulfur content increases under UVB and UVA irradiation, but it decreases under visible light irradiation. This is because the crystalloid substances are precipitated out of wool fibers [50]. As far as the W2 specimens are concerned, after hydrothermal treatment with tetraisopropyl titanate, the titanium element is introduced into wool fibers. After being exposed to UVB, UVA, and visible light irradiation for specific times, there are various reductions in the contents of carbon, nitrogen, and sulfur, but the oxygen contents increase. This is mainly attributed to the removal of organic components.

The results of chemical compositions of wool fibers

| Irradiation condition | Elements | Weight (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| W1 sample | W2 sample | ||

| Unexposed | C | 49.08 | 49.49 |

| N | 14.46 | 12.52 | |

| O | 29.10 | 27.31 | |

| S | 7.35 | 6.33 | |

| Ti | – | 4.36 | |

| 240 h UVC | C | 52.21 | 45.68 |

| N | 9.97 | 11.51 | |

| O | 17.25 | 34.65 | |

| S | 20.57 | 3.28 | |

| Ti | – | 4.88 | |

| 1,440 h UVA | C | 54.12 | 45.91 |

| N | 12.34 | 11.43 | |

| O | 19.45 | 32.51 | |

| S | 14.10 | 5.94 | |

| Ti | – | 4.21 | |

| 1,800 h visible light | C | 51.05 | 47.68 |

| N | 14.90 | 8.95 | |

| O | 27.33 | 34.66 | |

| S | 6.72 | 5.17 | |

| Ti | – | 3.54 | |

3.7 Molecule structure

The FT-IR spectra of wool fibers before and after exposure to UVB (0.7 mW/cm2), UVA (0.26 mW/cm2), and visible light (59,500 lx) irradiation are shown in Figure 7. As for the W1 specimens, the N–H stretching vibration at 3,274 cm−1 is broadened after 360 h UVB irradiation. The CH3 asymmetric stretching vibration at 2,960 cm−1 is slightly shifted to 2,962 cm−1. The C=O stretching vibration at 1,630 cm−1 (amide I) increases to 1,645 cm−1 and the N–H bending vibration at 1,515 cm−1 increases to 1,523 cm−1 (amide II), implying the breaking of hydrogen bonds between keratin macromolecules [27]. The C–H asymmetric and symmetric bending vibrations at 1,449 and 1,391 cm−1 are weakened to some degree and separated into 1,442, 1,414, and 1,386 cm−1. This is ascribed to the removal of some crystalline substances in wool fibers [50]. The C–N stretching vibration at 1,234 cm−1 (amide III) is significantly weakened and decreases to 1,217 cm−1. Furthermore, besides the eliminations of 1,173 and 921 cm−1, the C–O stretching vibrations at 1,071 and 1,044 cm−1 are markedly strengthened and shifted to 1,079 and 1,041 cm−1, respectively, indicating the oxidation of sulfur and reduction of cysteic acid residues [6, 8], or the breaking of disulfide bond of cystine in wool scales [51], or the breakdown of inter- and intra-molecular chains of wool [50]. Under 1,440 h of UVA irradiation, the N–H absorption band at 3,274 cm−1 increases to 3,277 cm−1. The CH3 and CH2 asymmetric stretching vibrations at 2,960 and 2,927 cm−1 are shifted to 2,962 and 2,934 cm−1, respectively. However, there are no visible changes at bands of C=O, N–H, and C–N. The C–H symmetric bending vibration at 1,391 cm−1 decreases to 1,388 cm−1. Moreover, the C–O stretching vibration at 1,071 cm−1 increases to 1,077 cm−1. Exposed to visible light irradiation for 1,800 h, the N–H stretching vibration increases to 3,276 cm−1 and the CH3 asymmetric stretching vibration increases to 2,964 cm−1. Meanwhile, the C–H symmetric bending vibration is shifted to 1,389 cm−1.

FT-IR spectra of (A) W1-untreated and (B) W2-treated wool fibers.

In comparison with the unexposed W1 specimens, there is no obvious change for the W2 specimens except for the C–H symmetric bending vibration at 1,391 cm−1, which decreases to 1,389 cm−1. After exposure to 360 h of UVB irradiation, the N–H stretching vibration is slightly broadened. The CH3 asymmetric stretching vibration increases to 2,966 cm−1. The C=O, N–H, and C–N absorption bands at 1,630, 1,514, and 1,234 cm−1 are shifted to 1,643, 1,520, and 1,227 cm−1, respectively. The C–H asymmetric and symmetric vibrations at 1,449 and 1,389 cm−1 are shifted to 1,443 and 1,416 cm−1, respectively. In addition, the C–O stretching vibrations at 1,071, 1,045, and 921 cm−1 are strengthened and shifted to 1,083, 1,042, and 930 cm−1, respectively. Under 1,440 h UVA irradiation, the CH3 asymmetric stretching vibration increases 2,964 cm−1, while the C–H symmetric vibration decreases to 1,387 cm−1. The C=O and C–N absorption bands are shifted to 1,633 and 1,232 cm−1. The C–O stretching vibration at 1,045 cm−1 decreases slightly to 1,043 cm−1. After 1,800 h of visible light illumination, the CH3 asymmetric stretching vibration increases to 2,964 cm−1 and the C–H symmetric vibration decreases to 1,387 cm−1. The C–N stretching vibration is shifted to 1,232 cm−1. The C–O stretching vibration at 1,045 cm−1 decreases to 1,042 cm−1. In brief, it can be concluded that UVB, UVA, and visible light irradiation result in the photo-oxidation deterioration of the secondary structure of TiO2-coated wool fibers to a more or less degree, which greatly depends on the irradiance, irradiation time, and irradiation wavelengths. The short-wave UVB rays would cause more serious damage to the structurally disordered degree of wool than long-wave UVA rays and visible light.

3.8 Crystallinity and orientation

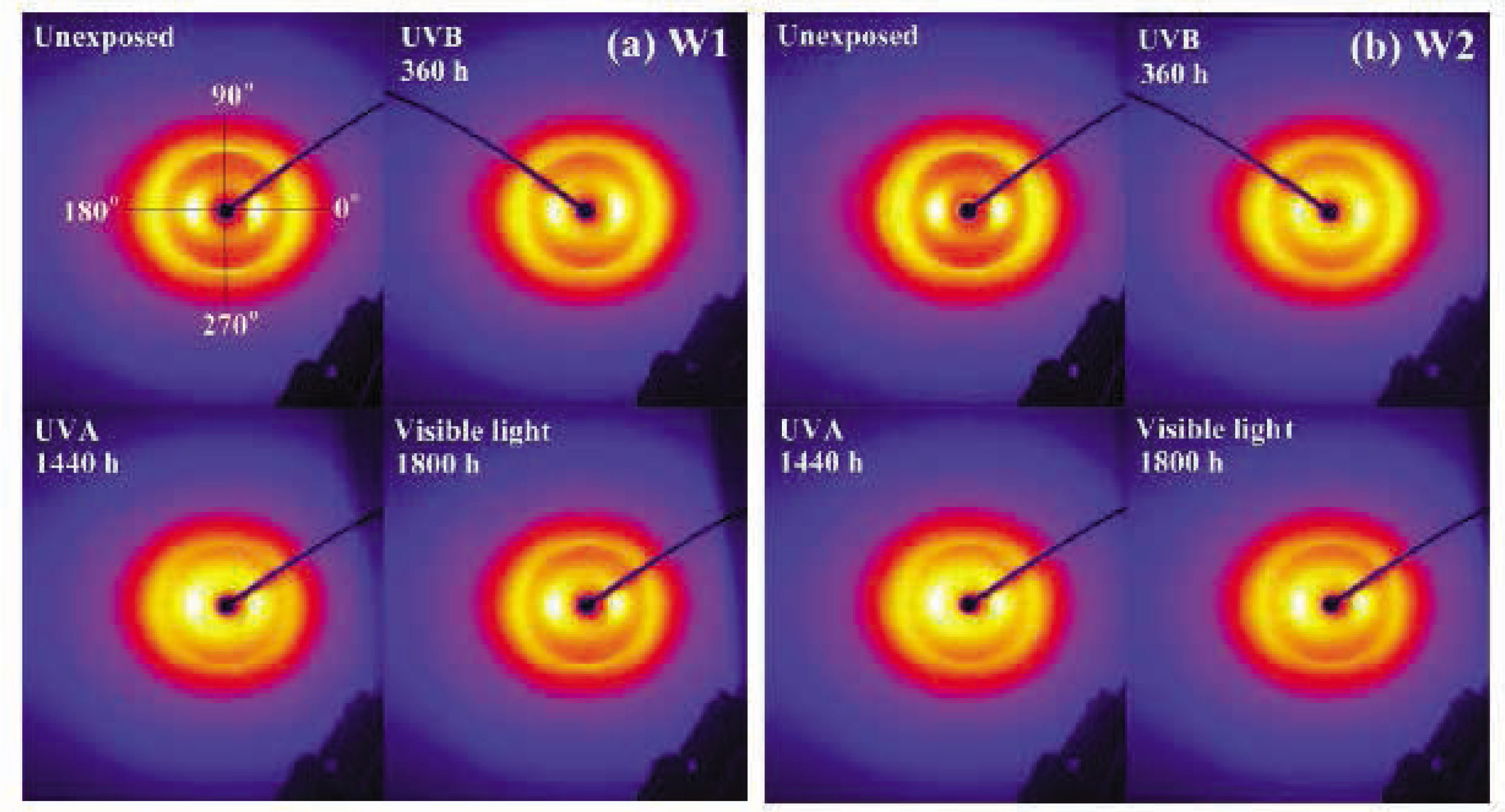

The two-dimensional X-ray diffraction (XRD) images, XRD curves, and orientation curves of wool fibers before and after exposure to UVB (0.7 mW/cm2), UVA (0.26 mW/cm2), and visible light (59,500 lx) irradiation are shown in Figures 8–10, respectively. It is seen in Figure 8 that the arc-shaped diffraction image of the unexposed W1 specimens directly reveals the oriented crystal structure and the crystalline state of wool [52]. The preferred orientation of the keratin molecules is located at the angles of 0° (180° and 90° (270° After exposure to UVB (360 h) or UVA (1,440 h) or visible light (1,800 h) irradiation, the brightness of spots at 0° (180° becomes dull and the small arc rings at 90° (270° are almost disappeared. It means that the preferred orientation of wool is weakened to some extent, namely the orientation of the keratin molecules becomes random. A similar phenomenon is also found in the W2 specimens. It is known that the wool fibers are constituted with long-chain polypeptides held together by the covalent and electrovalent cross-linkages. The valence forces vary according to the type of linkage, and the electrovalent forces include Coulomb forces and Van del Vaal's forces [53]. Therefore, the long-term illumination under UVB/UVA rays or visible light would disorder the margin of α-helical crystalline phase and cause the part of β-helical crystals irregularity [54], leading to the degradation of tensile properties of wool fibers.

Two-dimensional X-ray diffraction images of (A) W1-untreated and (B) W2-treated wool fibers.

It is worth noticing in Figure 9 that in comparison with the W1 specimens, besides the characteristic diffraction peaks at around 9° (the equatorial reflections of 0.98 nm for α-helix and β-sheet structure) and 20° (the meridional reflections of 0.51 nm for α-helix structure and the equatorial reflections of 0.465 nm for β-sheet structure) of wool [30], a series of small diffraction peaks are observed in the XRD curves of the W2 specimens. The diffraction peaks occurred at 25° 38° 48° 54° 55° 63° and 75° are assigned to the (101), (004), (200), (105), (211), (204), and (215) crystalline planes of anatase TiO2 (JCPDS No 21-1272) [55]. As shown in Table 2, the crystallinity indices of the W1 specimens decrease from 34.7 to 29.7% after 360 h of UVB, 26.5% after 1,440 h of UVA, and 31.8% after 1,800 h of visible light irradiation. When the wool fibers are treated with tetraisopropyl titanate, the CI of the W2 specimens decreases to 34.2%. After being irradiated by UVB, UVA, and visible light irradiation, the crystallinity indices further decrease to 22.9% after 360 h of UVB, 27.0% after 1,440 h of UVA, and 27.8% after 1,800 h of visible light irradiation.

XRD curves of (A) W1-untreated and (B) W2-treated wool fibers.

The results of the crystallinity index and orientation degree for wool fibers

| Wool fibers | Irradiation condition | Crystallinity index (%) | Orientation degree |

|---|---|---|---|

| W1 | Unexposed | 34.7 | 0.726 |

| UVC 240 h | 29.7 | 0.715 | |

| UVA 1,440 h | 26.5 | 0.666 | |

| Visible light 1,800 h | 31.8 | 0.720 | |

| W2 | Unexposed | 34.2 | 0.734 |

| UVC 240 h | 22.9 | 0.700 | |

| UVA 1,440 h | 27.0 | 0.698 | |

| Visible light 1,800 h | 27.8 | 0.697 |

The orientation curves in Figure 10 make clear that the orientation structure of wool fibers is changed to some degree after being treated with tetraisopropyl titanate, especially when they are exposed to UVB/UVA rays or visible light. The orientation degrees (see Table 2) of the W1 specimens decrease from 0.726 to 0.715 after 360 h of UVB, 0.666 after 1,440 h of UVA, and 0.72 after 1,800 h of visible light irradiation. The decreases in orientation for the irradiated wool fibers are assigned to the scission of peptide chains, resulting from the short-chain molecules [7]. The orientation degree of the W2 specimens increases to 0.734 after being treated with tetraisopropyl titanate. The orientation degrees of the W2 specimens decrease to 0.70 after 360 h of UVB, 0.698 after 1,440 h of UVA, and 0.697 after 1,800 h of visible light irradiation. As a result, high-intensity UVB, UVA, and visible light irradiation can lead to the destruction of wool fibers whether it is coated with TiO2 nanoparticles or not.

Orientation curves of (A) W1-untreated and (B) W2-treated wool fibers.

4 Conclusions

To sum up, TiO2-coated wool fibers are irradiated under high-intensity UVB, UVA, and visible light irradiation. The results of tensile and yellowness and whiteness indices indicate that the tensile strength and elongation at break of TiO2-coated wool fibers decrease significantly when exposed to UVB rays for a certain time. The high energy UVB irradiation causes much more damage to wool fibers than UVA rays and visible light. However, the TiO2 coating can protect wool fibers from high-intensity UVB, UVA, and visible light to a more or less degree. After irradiation, the postyield region of the stress–strain curve of TiO2-coated wool fibers is lost. The coating of TiO2 can almost not withstand the photo-yellowing of wool fibers against UVB rays compared with UVA rays and visible light. TGA/DTG results indicate that the TiO2 coating facilitates the thermal stability of wool fibers when exposed to UVB/UVA rays or visible light. SEM, EDX, FT-IR, and XRD indicate that the coating of TiO2 is constituted with anatase TiO2 nanoparticles and organic components. The morphology of wool fibers can be well preserved by the TiO2 coating under the high-intensity UVB, UVA, and visible light irradiation. However, the chemical composition and molecule structure of TiO2-coated wool fibers are changed. The crystallinity indices and orientation degrees of TiO2-coated wool fibers are reduced too.

Acknowledgements

This study has been supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 51873169) and the Sanqin Scholar Foundation (2017).

References

[1] Kim, J. I., David, S. K. (1992). The photostability of shrinkproofing polymer systems on wool fabric. Polymer Degradation and Stability, 38(2), 131–137.10.1016/0141-3910(92)90006-QSearch in Google Scholar

[2] Lee, W. S. (2009). Photoaggravation of hair aging. International Journal of Trichology, 1(2), 94–99.10.4103/0974-7753.58551Search in Google Scholar

[3] Millington, K. R., Church, J. S. (1997). The photodegradation of wool keratin II. Proposed mechanisms involving cystine. Journal of Photochemistry and Photobiology B: Biology, 39(3), 204–212.10.1016/S1011-1344(96)00020-6Search in Google Scholar

[4] Launer, H. F., (1965). Effect of light upon wool. Part IV: Bleaching and yellowing by sunlight. Textile Research Journal, 35(5), 395–400.10.1177/004051756503500502Search in Google Scholar

[5] Schmidt, H., Wortmann, F. J. (1994). High pressure differential scanning calorimetry and wet bundle tensile strength of weathered wool. Textile Research Journal, 64(11), 690–695.10.1177/004051759406401108Search in Google Scholar

[6] Church, J. S., Millington, K. R. (1996). Photodegradation of wool keratin: Part 1. Vibrational spectroscopic studies. Biospectroscopy, 2(4), 249–258.10.1002/(SICI)1520-6343(1996)2:4<249::AID-BSPY6>3.0.CO;2-1Search in Google Scholar

[7] El-Zaher, N. A., Micheal, M. N. (2002). Time optimization of ultraviolet–ozone pretreatment for improving wool fabrics properties. Journal of Applied Polymer Science, 85(7), 1469–1476.10.1002/app.10750Search in Google Scholar

[8] Periolatto, M., Ferrero, F., Migliavacca, G. (2014). Low temperature dyeing of wool fabric by acid dye after UV irradiation. The Journal of the Textile Institute, 105(10), 1058–1064.10.1080/00405000.2013.872324Search in Google Scholar

[9] Lennox, F. G., King, M. G., Leaver, I. H., Ramsay, G. C., Savige, W. E. (1971). Mechanisms, prevention, and correction of wool photo-yellowing. Applied Polymer Symposia, 18, 353–369.Search in Google Scholar

[10] Andrady, A. L., Harnid, S. H., Hu, X., Torikai, A. (1995). Effects of increased solar ultraviolet radiation on materials. Journal of Photochemistry and Photobiology B Biology, 24(3), 191–196.10.1016/S1011-1344(98)00188-2Search in Google Scholar

[11] Millington, K. R. (2006). Photoyellowing of wool. Part 1: Factors affecting photoyellowing and experimental techniques. Coloration Technology, 122(4), 169–186.10.1111/j.1478-4408.2006.00034.xSearch in Google Scholar

[12] Dyer, J. M., Bringans, S. D., Bryson, W. G. (20061). Characterisation of photo-oxidation products within photoyellowed wool proteins: Tryptophan and tyrosine derived chromophores. Photochemical & Photobiological Sciences, 5(7), 698–706.10.1039/b603030kSearch in Google Scholar PubMed

[13] Nogueira, A. C. S., Richena, M., Dicelio, L. E., Joekes, I. (2007). Photo yellowing of human hair. Journal of Photochemistry and Photobiology B: Biology, 88(2–3), 119–125.10.1016/j.jphotobiol.2007.05.005Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[14] Zhang, H., Millington, K. R., Wang, X. G. (2008). A morphology-related study on photodegradation of protein fibres. Journal of Photochemistry and Photobiology B: Biology, 92(3), 135–143.10.1016/j.jphotobiol.2008.05.011Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[15] Zhang, H., Deb-Choudhury, S. (2013). The effect of wool surface and interior modification on subsequent photostability. Journal of Applied Polymer Science, 127(5), 3435–3440.10.1002/app.37573Search in Google Scholar

[16] Millington, K. R. (2016). Photoyellowing of wool. Part 2: Photoyellowing mechanisms and methods of prevention. Coloration Technology, 122(6), 301–316.10.1111/j.1478-4408.2006.00045.xSearch in Google Scholar

[17] Riedel, J. H., Hocker, H. (1996). Multifunctional polymeric UV absorbers for photostabilization of wool. Textile Research Journal, 66(11), 684–689.10.1177/004051759606601103Search in Google Scholar

[18] Jones, D. C., Carr, C. M., Cooke, W. D., Lewis, D. M. (1998). Investigating the photo-oxidation of wool using FT-Raman and FT-IR spectroscopies. Textile Research Journal, 68(10), 739–748.10.1177/004051759806801007Search in Google Scholar

[19] Millington, K. R., Giudice, M. D., Sun, L. (2014). Improving the photostability of bleached wool without increasing its yellowness. Coloration Technology, 130(6), 413–417.10.1111/cote.12109Search in Google Scholar

[20] Montazer, M. Pakdel, E. (20112). Functionality of nano titanium dioxide on textiles with future aspects: Focus on wool. Journal of Photochemistry and Photobiology C-Photochemistry Reviews, 12(4), 293–303.10.1016/j.jphotochemrev.2011.08.005Search in Google Scholar

[21] Pakdel, E., Daoud, W. A., Wang, X. G. (2015). Assimilating the photo-induced functions of TiO2-based compounds in textiles: Emphasis on the sol-gel process. Textile Research Journal, 85(13), 1404–1428.10.1177/0040517514551462Search in Google Scholar

[22] Montazer, M., Amiri, M. M., Reza, M. A. M. (2013). In situ synthesis and characterization of nano ZnO on wool: Influence of nano photo reactor on wool properties. Photochemistry and Photobiology, 89(5), 1057–1063.10.1111/php.12090Search in Google Scholar

[23] Zhang, M. W., Tang, B., Sun, L., Wang, X. G. (20142). Reducing photoyellowing of wool fabrics with silica coated ZnO nanoparticles. Textile Research Journal, 84(17), 840–1848.10.1177/0040517514530028Search in Google Scholar

[24] Baaka, N., Ben Ticha, M., Haddar, W., Amorim, M. T. P., Mhenni, M. F. (2018). Upgrading of UV protection properties of several textile fabrics by their dyeing with grape pomace colorants. Fibers and Polymers, 19(2), 307–312.10.1007/s12221-018-7327-0Search in Google Scholar

[25] Masakazu, A. Masato, T. (2003). The design and development of highly reactive titanium oxide photocatalysts operating under visible light irradiation. Journal of Catalysis, 216(1), 505–516.10.1016/S0021-9517(02)00104-5Search in Google Scholar

[26] Yang, H. Y., Zhu, S. K., Pan, N. (2004). Studying the mechanisms of titanium dioxide as ultraviolet-blocking additive for films and fabrics by an improved scheme. Journal of Applied Polymer Science, 92(5), 3201–3210.10.1002/app.20327Search in Google Scholar

[27] Hsieh, S. H., Zhang, F. R., Li, H. S. (2006). Anti-ultraviolet and physical properties of woolen fabrics cured with citric acid and TiO2/chitosan. Journal of Applied Polymer Science, 100(6), 4311–4319.10.1002/app.23830Search in Google Scholar

[28] Tung, W. S., Daoud, W. A., Leung, S. K. (2009). Understanding photocatalytic behavior on biomaterials: Insights from TiO2 concentration. Journal of Colloid and Interface Science, 339(2), 424–433.10.1016/j.jcis.2009.07.043Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[29] Siwinska-Stefanska, K., Ciesielczyk, F., Kołodziejczak-Radzimska, A., Paukszta, D., Sojka-Ledakowicz, J., et al. (2012). TiO2-SiO2 inorganic barrier composites: From synthesis to application. Pigment & Resin Technology, 41(3), 139–148.10.1108/03699421211226426Search in Google Scholar

[30] Niu, M., Liu, X. G., Dai, J. M., Hou, W. S., Wei, L. Q., et al. (2012). Molecular structure and properties of wool fiber surface-grafted with nano-antibacterial materials. Spectrochimica Acta Part A: Molecular and Biomolecular Spectroscopy, 86, 289–293.10.1016/j.saa.2011.10.038Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[31] McNeil, S. J., Sunderland, M. R. (2016). The nanocidal and antifeedant activities of titanium dioxide desiccant toward wool-digesting Tineola bisselliella moth larvae. Clean Technologies and Environmental Policy, 18(3), 843–852.10.1007/s10098-015-1060-4Search in Google Scholar

[32] Sunderland, M. R., McNeil, S. J. (2017). Protecting wool carpets from beetle and moth larvae with nanocidal titanium dioxide desiccant. Clean Technologies and Environmental Policy, 19(4), 1205–1213.10.1007/s10098-016-1297-6Search in Google Scholar

[33] Montazer, M., Pakdel, E. (20111). Self-cleaning and color reduction in wool fabric by nano titanium dioxide. Journal of the Textile Institute, 102(4), 343–352.10.1080/00405001003771242Search in Google Scholar

[34] Liu, J., Wang, Q., Fan, X. R. (2012). Layer-by-layer self-assembly of TiO2 sol on wool to improve its anti-ultraviolet and anti-ageing properties. Journal of Sol-Gel Science and Technology, 62(3), 338–343.10.1007/s10971-012-2730-xSearch in Google Scholar

[35] Zhang, H., Millington, K. R., Wang, X. G. (2009). The photostability of wool doped with photocatalytic titanium dioxide nanoparticles. Polymer Degradation and Stability, 94(2), 278–283.10.1016/j.polymdegradstab.2008.10.009Search in Google Scholar

[36] Montazer, M., Pakdel, E. (2010). Reducing photoyellowing of wool using nano TiO2. Photochemistry and Photobiology, 86(2), 255–260.10.1111/j.1751-1097.2009.00680.xSearch in Google Scholar PubMed

[37] Montazer, M., Pakdel, E., Moghadam, M. B. (2011). The role of nano colloid of TiO2 and butane tetra carboxylic acid on the alkali solubility and hydrophilicity of proteinous fibers. Colloids and Surfaces A: Physicochemical and Engineering Aspects, 375(1–3), 1–11.10.1016/j.colsurfa.2010.10.051Search in Google Scholar

[38] Montazer, M., Morshedi, S. (2014). Photo bleaching of wool using nano TiO2 under daylight irradiation. Journal of Industrial and Engineering Chemistry, 20(1), 83–90.10.1016/j.jiec.2013.04.023Search in Google Scholar

[39] Behzadnia, A., Montazer, M., Rashidi, A., Rad, M. M. (2014). Rapid sonosynthesis of N-doped nano TiO2 on wool fabric at low temperature: Introducing self-cleaning, hydrophilicity, antibacterial/antifungal properties with low alkali solubility, yellowness and cytotoxicity. Photochemistry and Photobiology, 90(6), 1224–1233.10.1111/php.12324Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[40] Montazer, M., Seifollahzadeh, S. (2011). Enhanced self-cleaning, antibacterial and UV protection properties of nano TiO2 treated textile through enzymatic pretreatment. Photochemistry and Photobiology, 87(4), 877–883.10.1111/j.1751-1097.2011.00917.xSearch in Google Scholar PubMed

[41] Haji, A., Shoushtari, A. M., Mazaheri, F., Tabatabaeyan, S. E. (2016). RSM optimized self-cleaning nano-finishing on polyester/wool fabric pretreated with oxygen plasma. The Journal of the Textile Institute, 107(8), 985–994.10.1080/00405000.2015.1077023Search in Google Scholar

[42] Behzadnia, A., Montazer, M., Rad, M. M. (2016). In situ photo sonosynthesis of organic/inorganic nanocomposites on wool fabric introducing multifunctional properties. Photochemistry and Photobiology, 92(1), 76–86.10.1111/php.12546Search in Google Scholar

[43] Zhang, M. W., Xie, W. J., Tang, B., Sun, L., Wang, X. G. (2017). Synthesis of TiO2&SiO2 nanoparticles as efficient UV absorbers and their application on wool. Textile Research Journal, 87(14), 1784–1792.10.1177/0040517516659375Search in Google Scholar

[44] Aksakal, B., Koc, K., Bozdogan, A., Tsobkallo, K. (2013). Uniaxial tensile properties of TiO2 coated single wool fibers by sol-gel method: The effect of heat treatment. Journal of Applied Polymer Science, 130(2), 898–907.10.1002/app.39162Search in Google Scholar

[45] Bohn, A., Fink, H. P., Ganster, J., Pinnow, M. (2000). X-ray texture investigations of bacterial cellulose. Macromolecular Chemistry and Physics, 201(15), 1913–1921.10.1002/1521-3935(20001001)201:15<1913::AID-MACP1913>3.0.CO;2-USearch in Google Scholar

[46] Zhang, H., Sun, R. J., Zhang, X. T. (2014). Effect of hydrothermal processing on the structure and properties of wool fibers. Industria Textila, 65(3), 123–128.Search in Google Scholar

[47] Dyer, J. M., Bringans, S. D., Bryson, W. G. (2006). Determination of photooxidation products within photoyellowed bleached wool proteins. Photochemistry and Photobiology, 82(2), 551–557.10.1562/2005-08-29-RA-663Search in Google Scholar

[48] Millington, K. R. (2012). Diffuse reflectance spectroscopy of fibrous proteins. Amino Acids, 43(3), 1277–1285.10.1007/s00726-011-1201-ySearch in Google Scholar

[49] Zhang, H., Yang, Z. W., Zhang, X. T., Mao, N. T. (2014). Photocatalytic effects of wool fibers modified with solely TiO2 nanoparticles and N-doped TiO2 nanoparticles by using hydrothermal method. Chemical Engineering Journal, 254(7), 106–114.10.1016/j.cej.2014.05.097Search in Google Scholar

[50] Zeng, Y., Liu, Y., Liu, J. J., Zheng, H. L., Zhou, Y., et al. (2015). Application of electron paramagnetic resonance spectroscopy, Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy-attenuated total reflectance and scanning electron microscopy to the study of the photo-oxidation of wool fiber. Analytical Methods, 7(24), 10403–10408.10.1039/C5AY01988ESearch in Google Scholar

[51] Xu, B. S., Niu, M., Wei, L. Q., Hou, W. S., Liu, X. G. (2007). The structural analysis of biomacromolecule wool fiber with Ag-loading SiO2 nano-antibacterial agent by UV radiation. Journal of Photochemistry and Photobiology A: Chemistry, 188(1), 98–105.10.1016/j.jphotochem.2006.11.025Search in Google Scholar

[52] Shi, K. H., Ye, L., Li, G. X. (2015). Structure and hydrothermal stability of highly oriented polyamide 6 produced by solid hot stretching. RSC Advances, 5(38), 30160–30169.10.1039/C5RA01976ASearch in Google Scholar

[53] Sookne, A. M., Harris, M. (1937). Stress-strain characteristics of wool as related to its chemical constitution. Journal of Research of the National Bureau of Standards, 19, 535–549.10.6028/jres.019.033Search in Google Scholar

[54] Xiao, X. L., Hu, J. L. (2016). Influence of sodium bisulfite and lithium bromide solutions on the shape fixation of camel guard hairs in slenderization process. International Journal of Chemical Engineering, 2016, 1–11.10.1155/2016/4803254Search in Google Scholar

[55] Yang, W. G., Wang, Y. L., Shi, W. M. (2012). One-step synthesis of single-crystal anatase TiO2 tetragonal faceted-nanorods for improved-performance dye-sensitized solar cells. CrystEngComm, 14(1), 230–234.10.1039/C1CE05844DSearch in Google Scholar

© 2021 Qi Tang et al., published by Sciendo

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Photostability of TiO2-Coated Wool Fibers Exposed to Ultraviolet B, Ultraviolet A, and Visible Light Irradiation

- Chemical Hand Warmers in Protective Gloves: Design and Usage

- The Removal of Reactive Red 141 From Wastewater: A Study of Dye Adsorption Capability of Water-Stable Electrospun Polyvinyl Alcohol Nanofibers

- A Review of Contemporary Techniques for Measuring Ergonomic Wear Comfort of Protective and Sport Clothing

- Experimental Study on Dyeing Performance and Antibacterial Activity of Silver Nanoparticle-Immobilized Cotton Woven Fabric

- Sewing Thread Consumption for Chain Stitches of Class 400 using Geometrical and Multilinear Regression Models

- The Status of Textile-Based Dry EEG Electrodes

- Comprehensive Assessment of the Properties of Cotton Single Jersey Knitted Fabrics Produced From Different Lycra States

- Prognosticating the Shade Change after Softener Application using Artificial Neural Networks

- Influence of the Structure of Seersucker Woven Fabrics on their Friction Properties

- Evaluation of Cochlospermum vitifolium Extracts as Natural Dye in Different Natural and Synthetic Textiles

- Homogeneous Coatings of Titanium Dioxide Nanoparticles on Corona-Treated Cotton Fabric for Enhanced Self-Cleaning and Antibacterial Properties

- Numerical Analysis of Large Deflections of a Flat Textile Structure with Variable Bending Rigidity and Verification of Results Using Fem Simulation

- Thermal Behavior of Aerogel-Embedded Nonwovens in Cross Airflow

- Kansei Engineering as a Tool for the Design of Traditional Pattern

Articles in the same Issue

- Photostability of TiO2-Coated Wool Fibers Exposed to Ultraviolet B, Ultraviolet A, and Visible Light Irradiation

- Chemical Hand Warmers in Protective Gloves: Design and Usage

- The Removal of Reactive Red 141 From Wastewater: A Study of Dye Adsorption Capability of Water-Stable Electrospun Polyvinyl Alcohol Nanofibers

- A Review of Contemporary Techniques for Measuring Ergonomic Wear Comfort of Protective and Sport Clothing

- Experimental Study on Dyeing Performance and Antibacterial Activity of Silver Nanoparticle-Immobilized Cotton Woven Fabric

- Sewing Thread Consumption for Chain Stitches of Class 400 using Geometrical and Multilinear Regression Models

- The Status of Textile-Based Dry EEG Electrodes

- Comprehensive Assessment of the Properties of Cotton Single Jersey Knitted Fabrics Produced From Different Lycra States

- Prognosticating the Shade Change after Softener Application using Artificial Neural Networks

- Influence of the Structure of Seersucker Woven Fabrics on their Friction Properties

- Evaluation of Cochlospermum vitifolium Extracts as Natural Dye in Different Natural and Synthetic Textiles

- Homogeneous Coatings of Titanium Dioxide Nanoparticles on Corona-Treated Cotton Fabric for Enhanced Self-Cleaning and Antibacterial Properties

- Numerical Analysis of Large Deflections of a Flat Textile Structure with Variable Bending Rigidity and Verification of Results Using Fem Simulation

- Thermal Behavior of Aerogel-Embedded Nonwovens in Cross Airflow

- Kansei Engineering as a Tool for the Design of Traditional Pattern