Abstract

This study discusses the effect of corona pretreatment and subsequent loading of titanium dioxide nanoparticles on self-cleaning and antibacterial properties of cellulosic fabric. The corona-pretreated cellulosic fabrics were characterized by field emission scanning electron microscopy, and X-ray mapping techniques revealed that layers of the titania deposited on cellulose fibers were more uniform than the sample without pre-corona treatment. The self-cleaning property of treated fabrics was evaluated through discoloring dye stain under sunlight irradiation. The antibacterial activities of the samples against two common pathogenic bacteria including Escherichia coli and Staphylococcus aureus were also assessed. The results indicated that self-cleaning and antibacterial properties of the corona-pretreated fabrics were superior compared to the sample treated with TiO2 alone. Moreover, using corona pretreatment leads to samples with good washing fastness.

1 Introduction

In recent decades, surface functionalization has been proven particularly effective in realizing unique textiles with desired properties such as self-cleaning, antibacterial, antifungal, flame retardancy, ultraviolet blocking and superhydrophobic [1,2,3,4,5,6]. In view of the close relationship with our daily life, the self-cleaning and antibacterial textiles are especially attractive. Nano-photocatalysts, such as TiO2, ZnO and ZrO2, have been used to impart self-cleaning and antibacterial properties to textiles [7,8,9,10]. Many efforts have been directed towards obtaining long-lasting durability of such effects by enhancing the binding efficiency of the nano-photocatalysts. For example, Mohammadi et al. obtained durable self-cleaning and antibacterial fabric through simultaneous synthesis of zinc oxide nanoparticles and alkaline hydrolysis of polyester fabric [11]. Khajavi and Berendjchi obtained self-cleaning cotton fabrics through applying the nanotitanium dioxide particles immobilized by carboxylic acids [12]. Along the same lines, Karimi et al. treated cotton fabrics with TiO2 nanoparticles in the presence of succinic acid as a cross-link agent and reported the significant improvement in the durability of self-cleaning property of the fabric [13]. Yu et al. utilized cograft polymerization strategy to immobilize TiO2 nanoparticles covalently onto the cotton fabric surface [14]. Kale et al. coated cellulose–TiO2 nanoparticles on cotton fabric for durable photocatalytic self-cleaning [15]. Moreover, Hu et al. improved the self-cleaning properties of cotton fabric through the application of highly durable polysiloxane–TiO2 hybridized coating [16].

Recently, some studies have focused on pretreatment of textiles by low-pressure plasma and corona discharge. Both low-pressure plasma and corona discharge alter the fiber surface morphology and chemical composition that are critical for interaction with different nanoparticles [17,18,19,20]. For instance, Mirjalili et al. used corona treatment to increase the adsorption and stability of TiO2 particles on cotton fabrics [21]. Along the same lines, Mihailović et al. treated the cotton fabric with corona discharge and air plasma prior to deposition of colloidal TiO2 nanoparticles [22]. The possibility of using the corona treatment for facilitating the loading of silver nanoparticles from a colloid onto the polyester and polyamide fabrics was studied by Radetić et al. [17]. Moreover, Rezaei et al. demonstrated that nylon 6 fabrics pretreated with corona discharge were able to bind ZnO nanoparticles [19]. In addition, Shahidi et al. prepared durable antibacterial cotton fabrics through synthesis of ZnO nanoparticles on plasma pretreated fabrics [23].

In this study, corona treatment as a dry and environmentally friendly process has been used for surface activation of cotton fabrics. Thereafter, the titanium dioxide nanoparticles immobilized on cotton fabrics by hydrolysis of titanium isopropoxide using the in situ synthesis method. The role of corona treating time and titanium isopropoxide concentration over the self-cleaning performance and antibacterial activities of treated fabrics was investigated.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Materials

The cotton fabric bleached with hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) was obtained from Baft Azadi Co. (Iran). The specifications of the used cotton fabrics are shown in Table 1. Titanium isopropoxide (C12H28O4Ti) as a metal alkoxide reagent for producing nano titanium dioxide and hydrochloric acid (HCl, 37%) was utilized from Merck. Direct green 6 (CI 30295) was purchased from Alvan Sabet Co. (Iran).

Fabric specifications

| Plain wave cotton fabric | Yarn count (Tex) | Density (yarn/cm) | Weight (g/m2) | Thickness at 0.5 gf×cm−2 (mm) | ||

| Warp | Weft | Warp | Weft | |||

| 18.9 | 27.3 | 25 | 21 | 120.8 | 0.736 | |

2.2 Instruments

Microscopic images of cotton samples were obtained by a field emission scanning electron microscopy (FE-SEM; MIRA3 TESCAN, Czech). The standard procedure was followed, in which samples for microscopic analyses were coated with a gold layer before tests to ensure sufficient electrical conductivity and to prevent charging effects. In addition, chemical analysis of treated cotton fabrics was carried out by energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (Oxford). The scan area of electronic probe was about 30 μm × 30 μm. The elemental values were averaged from four measurements. X-ray diffraction (XRD) patterns of the samples were recorded by an X-ray diffractometer (Equinox 3000, INEL, France). The patterns were recorded in the diffraction range of 2θ from angle of 10°to 60°with a scanning speed of 2°min at 2θ step of 0.040° Cu×Kα radiation (λ = 1.540 Å) with the detector scan mode operating at 40 kV and 30 mA was used to investigate changes in the crystalline. An ultrasonic bath WiseClean (50–60 Hz) was used for synthesis and processing.

2.3 Corona treatment

The samples were first placed on a silicon roll and were then stuck to it using glue. The rotation rate of the roll was constant during the experiment and was five cycles per minute. The cotton fabric was prepared with a dimension of 10 × 10 cm2 and was then exposed to corona treating in 2 ampere current for the periods of 1, 2, 3, 4 and 5 min.

2.4 Synthesis of TiO2 nanoparticles on cotton fabrics

To synthesize nanocrystalline titania on raw and corona-treated cotton fabrics, various concentrations of titanium isopropoxide were used as precursors. Hydrolysis was carried out from ambient temperature to 75–80°C with a rate of 1°C min−1 by controlled dropwise titanium isopropoxide in the presence of 100 mL distilled water under ultrasonic irradiation. The pH was held at 5–6 by hydrochloric acid. The nano-TiO2-treated samples were dried at 60°C for 15 min followed by curing at 120°C for 3 min.

The exact formation and tests results for each sample examined in this study are summarized in Table 2.

Experimental conditions and tests results

| Corona radiation time (s) | Titanium isopropoxide (ml) | Titania (OWF%) | ΔE* before washing | ΔE* after washing | Water absorption (s) | Bending length (cm) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| - | 0 | 0 | 1.32 | –a | 10 | 1.30 |

| 1 | 0.21 | 4.21 | 2.38 | 88 | 1.40 | |

| 3 | 0.56 | 15.34 | 4.98 | 121 | 1.45 | |

| 5 | 1.11 | 22.33 | 6.09 | 144 | 1.50 | |

| 1 | 0 | 0 | 1.42 | –a | 7 | 1.30 |

| 1 | 0.32 | 5.67 | 4.23 | 90 | 1.40 | |

| 3 | 1.04 | 16.44 | 12.05 | 123 | 1.50 | |

| 5 | 1.76 | 26.79 | 19.97 | 146 | 1.55 | |

| 2 | 0 | 0 | 1.43 | –a | 7 | 1.30 |

| 1 | 0.41 | 7.02 | 6.67 | 90 | 1.40 | |

| 3 | 1.46 | 17.34 | 15.45 | 131 | 1.45 | |

| 5 | 3.14 | 27.15 | 23.12 | 147 | 1.55 | |

| 3 | 0 | 0 | 1.55 | –a | 5 | 1.35 |

| 1 | 0.48 | 9.49 | 8.31 | 93 | 1.40 | |

| 3 | 1.99 | 20.36 | 18.43 | 137 | 1.55 | |

| 5 | 4.65 | 30.12 | 26.82 | 150 | 1.60 | |

| 4 | 0 | 0 | 1.47 | –a | 4 | 1.35 |

| 1 | 0.50 | 9.65 | 8.31 | 93 | 1.40 | |

| 3 | 2.12 | 21.39 | 20.69 | 144 | 1.50 | |

| 5 | 5.12 | 32.14 | 31.21 | 152 | 1.60 | |

| 5 | 0 | 0 | 1.62 | –a | 4 | 1.35 |

| 1 | 0.52 | 9.75 | 9.15 | 97 | 1.45 | |

| 3 | 2.17 | 23.48 | 22.53 | 144 | 1.55 | |

| 5 | 5.21 | 33.56 | 32.01 | 155 | 1.60 |

- a

Test was not performed

2.5 Test methods

The self-cleaning function was estimated based on degradation of direct green 6 dye (100 mg/L) stain under sunlight (Yazd, Iran) irradiation for 3 consecutive days [11]. The color changes were determined with the ΔE* value based on the CIELAB color system. The total color difference (ΔE*) was calculated according to the following equation:

where L* defines lightness, a* denotes the red-green value and b* indicates the yellow-blue value.

Moreover, to evaluate the durability of coatings on the fabric, the color difference of the samples was measured after laundering. The titania-treated fabrics were washed according to the American Association of Textile Chemists and Colorists (AATCC) Test Method 61-2003 Test No. 2A using AATCC Standard Instrument Atlas Launder-Ometer (model LEF). An AATCC Standard Reference Detergent WOB was used. The treated samples were subjected to four cycles of consecutive washing. At the end of the fourth cycle, the samples were rinsed with distilled water and air-dried. Using this approach, each cycle of washing process is equivalent to five home machine launderings.

The AATCC 100–2004 test method as a quantitative technique was chosen for measuring antibacterial properties of the treated samples against Escherichia coli (ATCC 25922) and Staphylococcus aureus (ATCC 25923) as ordinary pathogenic bacteria. Antibacterial activity was expressed in terms of the bacteria reduction percentage (BR%) and calculated using the following equation:

Here A is the number of bacteria recovered from the inoculated treated test specimen incubated over 24 h, while B is the number of bacteria recovered from the inoculated treated test specimen immediately after inoculation (at “0” contact time).

The burning method was used to determine the percentage of titanium dioxide on weight of fabric (OWF). Weight-treated cotton fabrics were placed in a porcelain crucible and kept in an oven with a room temperature of 900°C for 140 min. The calculations were conducted in such a manner that the remainder weight was subtracted from the remainder weight of the raw cotton sample, and then the percentage was obtained.

Stiffness of fabric samples was determined according to the ASTM D 1388–96 (2002) test method. The AATCC 79–2000 test method was chosen for measuring hydrophilicity of the cotton samples.

3 Results and discussion

3.1 Characterization

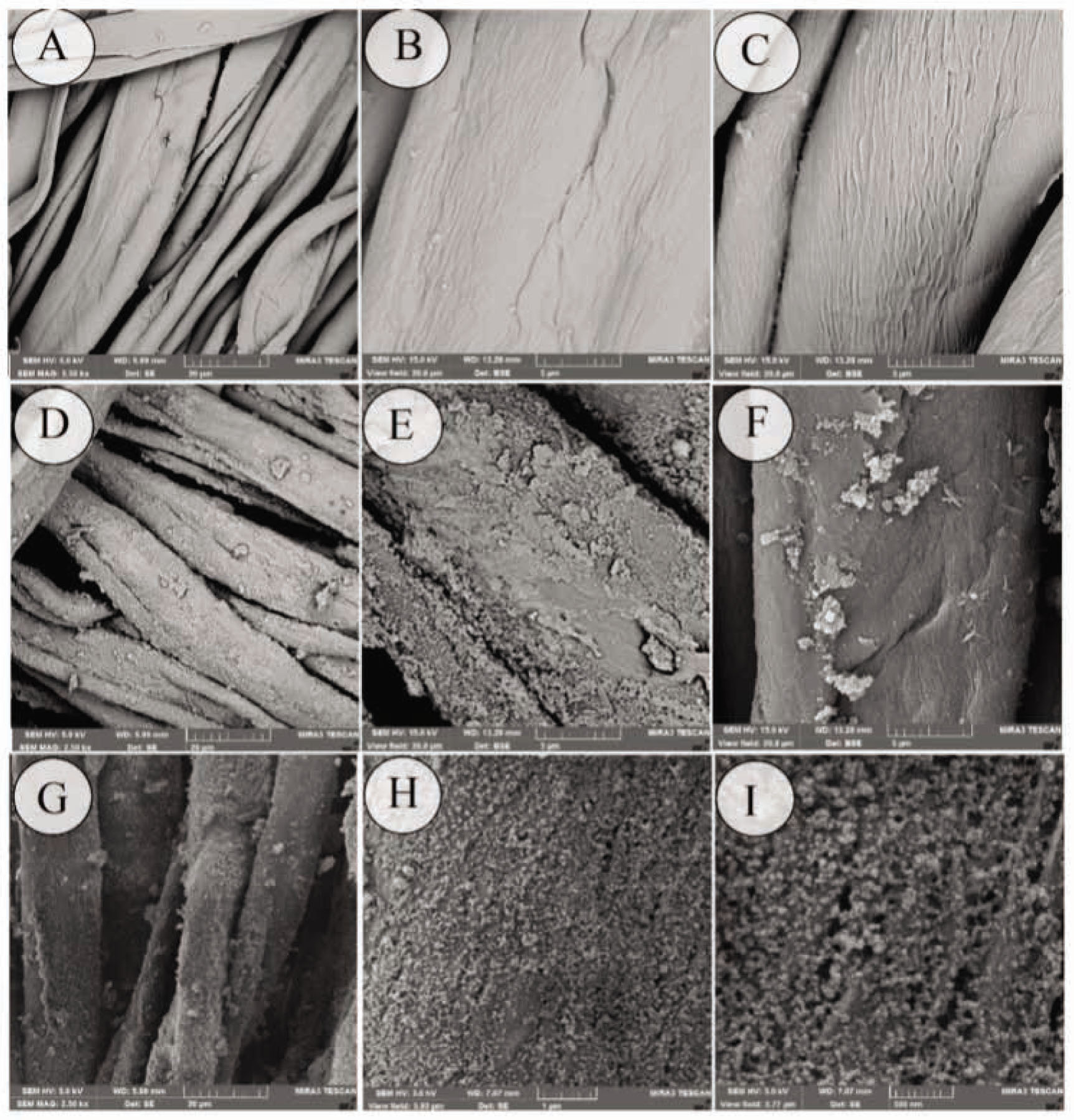

Microscopic images of raw cotton fabric, cotton fabric treated with corona and cotton samples treated with 5 ml titanium isopropoxide are presented in Figure 1. The surface of raw cotton is neat and smooth, and there is no particle existing on its surface (Figure 1A and B). As it can be observed in Figure 1C, physical grooves are created on the surface of cotton fibers as a result of corona radiation intensity. Morphological changes induced by corona can be attributed to fiber etching, which occurred as a consequence of a severe bombardment of the fiber surface by energetic particles and by reactive particles generated by the plasma [21]. After synthesis of titania, nano-TiO2 particles distribute on the surface of the cotton fabric (Figure 1D–I). It can be seen that titanium dioxide nanoparticles are accumulated on untreated fibers and the texture background of cotton fibers is clearly distinguishable (Figure 1D–F). However, distribution of TiO2 nanoparticles in the sample pretreated with corona is desirable (Figure 1 H and I). The average size of the TiO2 nanoparticles is in the range of 20–25 nm. Corona treatment increased the fiber surface area and the surface roughness. Altered chemical structure along with morphological changes in the cotton fiber surface improved the fiber accessibility to TiO2 nanoparticles [22].

FE-SEM images of various cotton fabric samples: (A and B) raw, (C) treated with corona radiation for 3 min, (D–F) treated with 5 ml titanium isopropoxide without corona pretreatment and (G–I) treated with 5 ml titanium isopropoxide and corona radiation (for 3 min). Note the different magnifications: (A) 2.5 kX, (B) 10 kX, (C) 10 kX, (D) 2.5 kX, (E) 10 kX, (F) 10 kX, (G) 2.5 kX, (H) 20 kX and (I) 30 kX.

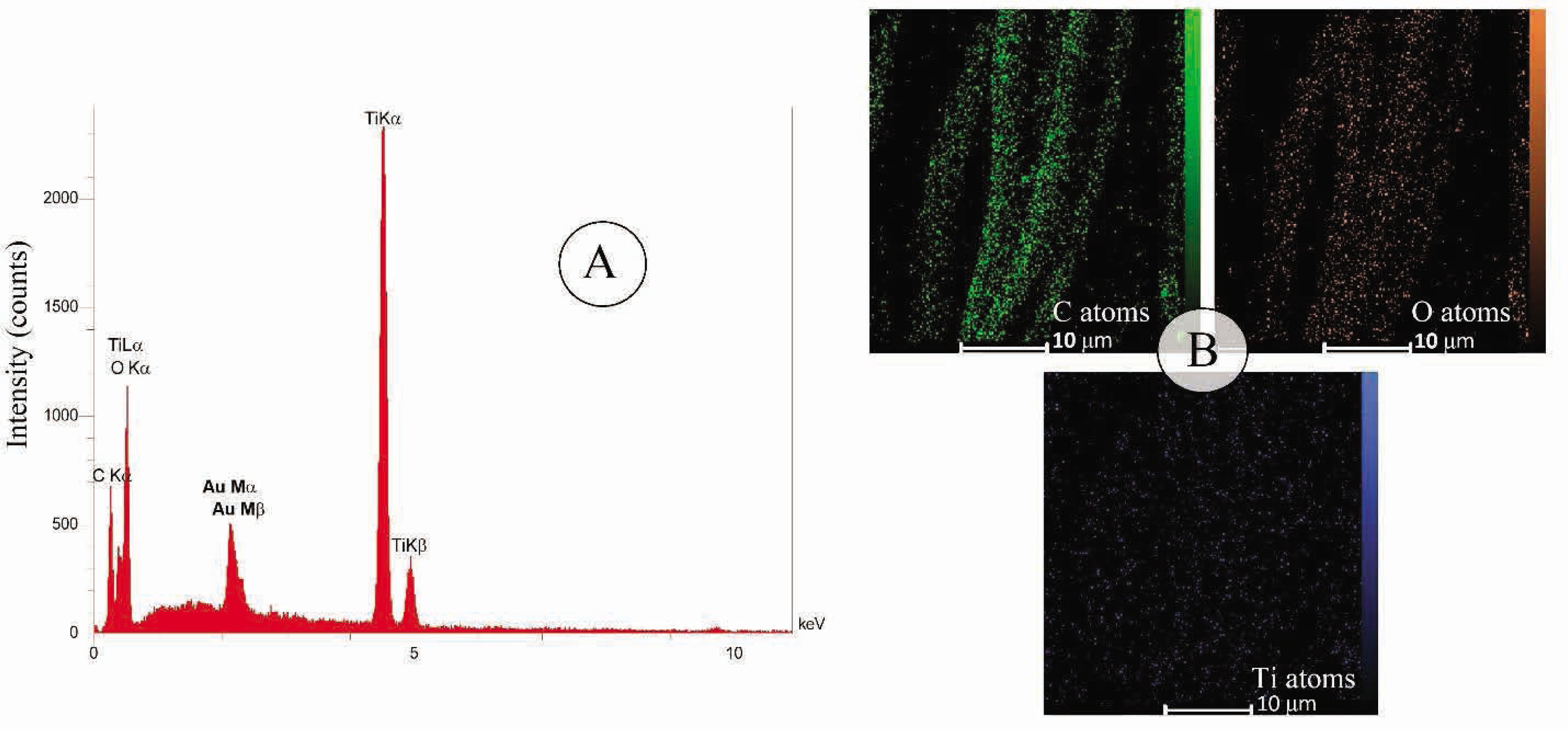

Figure 2A displays the EDS pattern of treated fabric with titanium dioxide nanoparticles after corona radiation, which indicates the presence of C, O, Ti and Au elements on the surface of the fabric. The presence of Au element in the EDS pattern is due to coating of gold layer on the fabric before FE-SEM observation. The distribution of C, O and Ti elements in treated cotton is investigated by the elemental mapping (Figure 2B). It is clearly illustrated that the distribution of Ti on the fabric surface is uniform.

EDS spectrum (A) and X-ray mapping images (B) of treated cotton fabric with titania (5 ml titanium isopropoxide) and corona radiation (for 3 min).

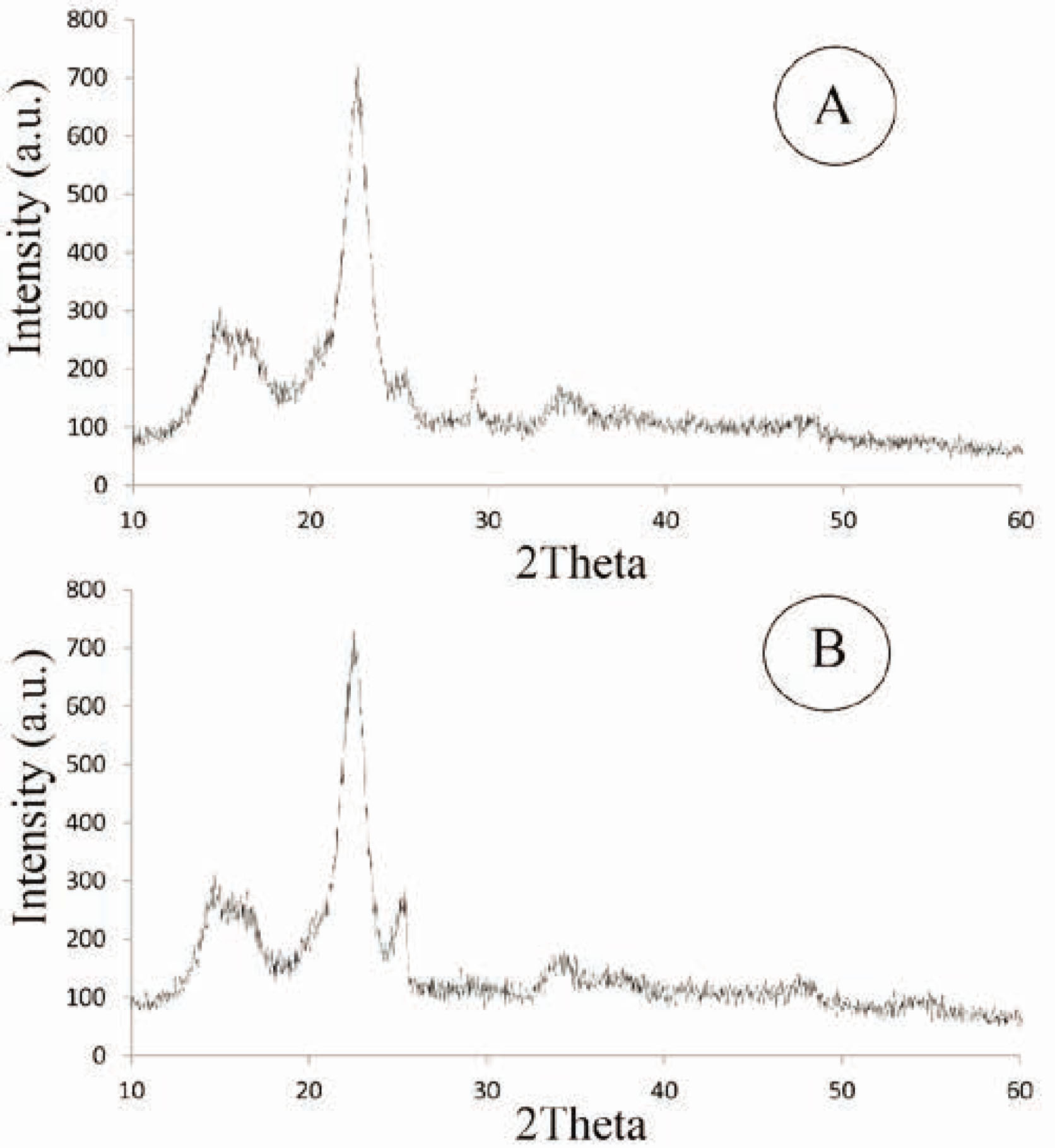

Figure 3 shows the XRD patterns of nano-TiO2-treated cotton fabrics with and without corona pretreatment. XRD spectra of samples exhibit two prominent peaks at 2θ angles of 16.5º and 22.8º, which are derived from cotton as a main substrate. The presence of titanium dioxide nanoparticles on the treated cotton fabrics can be confirmed by characterization peaks at 2θ angles of 25.3° (TiO2 anatase), 28.2° and 36.1° (TiO2 rutile) (JCPDS Card Nos. 21–1272 and 21–1276). A synergistic effect has been reported for the high photocatalytic activity by mixing rutile TiO2 into anatase TiO2 [24]. In addition, based on the following equation, the crystal size was calculated at 2θ = 25.3° and for the titania was 213 Å.

where K = 0.9 is the shape factor, λ = 1.54 is the wavelength of X-ray of Cu radiation, FWHM is full width at half maximum of the peak and θ is the diffraction angle.

The data for burning test are presented in Table 1. The results acquired indicate that the greater amount of titanium isopropoxide in impregnation bath leads to more TiO2 nanoparticles on the fabric surface. In addition, pretreatment of cotton fabrics with corona radiation had tangible effect on adsorption of nano-TiO2. The titanium dioxide percentage of coated cotton samples increased from 0.32% to 5.21% by increasing the time of corona radiation from 1 to 5 s. It can be concluded that pre-corona treatment results in better adsorption of titanium dioxide nanoparticles on the cotton fabric. Therefore, the results of the burning test confirm the results obtained from the FE-SEM images.

3.2 Self-cleaning

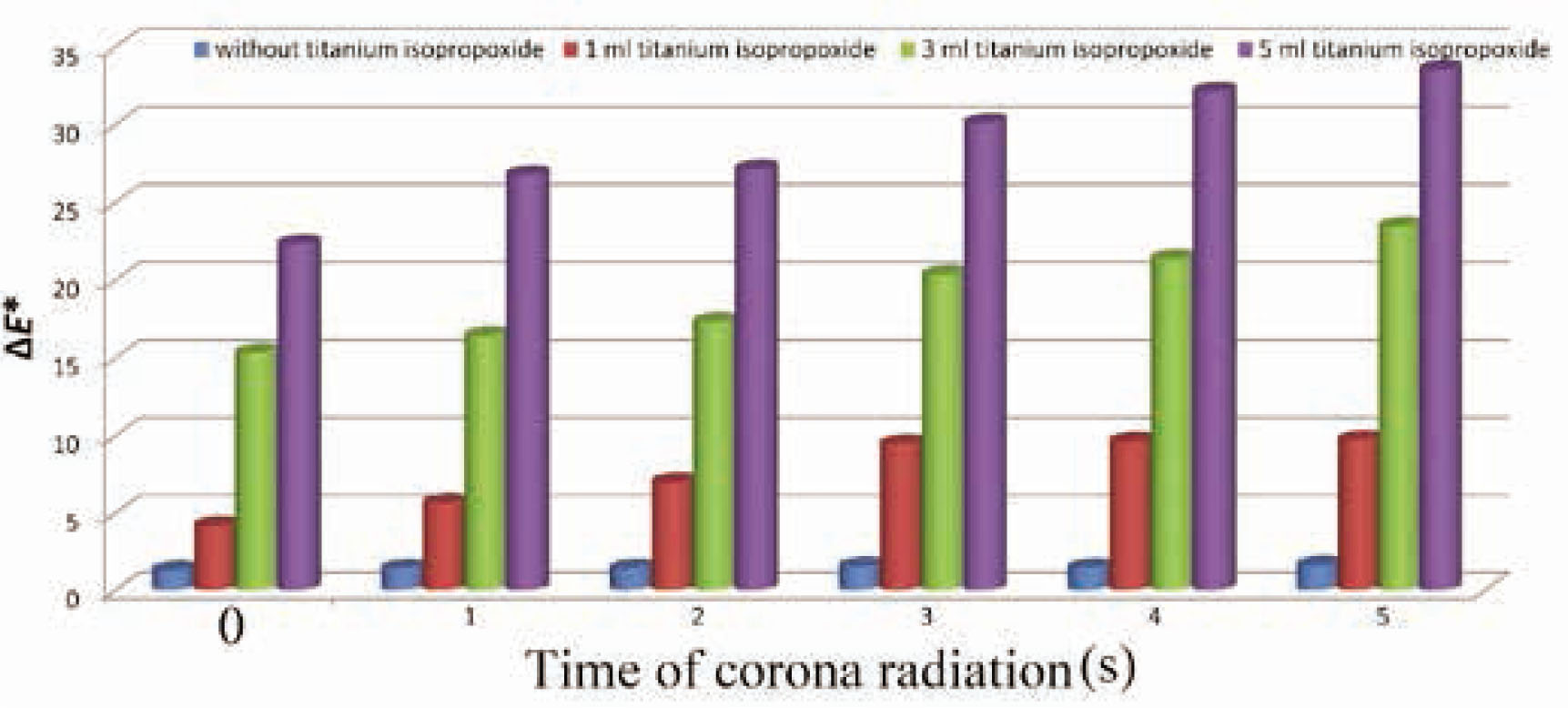

The cotton fabrics were stained with direct green 6 dye solution and exposed to sunlight irradiation. The fabric color coordinates were calculated before and after sunlight irradiation, and the self-cleaning performance was obtained based on the color difference (ΔE*). The raw cotton fabrics were not photoactive (ΔE* in the range of 1.32–1.62). As seen in Figure 4 and Table 2, all the nano-TiO2-treated cotton fabrics showed higher ΔE* values arising from photocatalytic activity of titanium dioxide nanoparticles to degrade dye stain. Irradiation of photocatalyst like TiO2 by light with more energy, compared to its band gaps, generates electron–hole pairs that induce redox reactions at the surface of the photocatalyst. Thus, titania can decompose common organic matters, dye molecules, bacterial cell membranes, etc. [25].

XRD patterns of treated cotton fabric with (A) 5 ml titanium isopropoxide and (b) 5 ml titanium isopropoxide along and corona radiation (for 3 min).

Comparative diagram of self-cleaning performance results of the cotton samples.

The results show that the amount of self-cleaning for the treated samples is higher when pretreated with corona radiation. Increasing the time of corona radiation increases the photodegradation of direct green 6. Increasing the time of corona pretreatment results in the increase in polar groups such as carboxyl groups on the surface of the cotton fibers [21, 22]. Therefore, more polar positions increase adsorption of nano-TiO2 and photodegradation of the direct dye. In addition, the increase in the titanium isopropoxide concentration had a tangible effect on the pho-activity of treated cotton samples, and the ΔE* of treated samples increased progressively because of the higher titania content on the fabric surface.

As shown in Table 2, after washing treatment, a significant reduction is observed in the amount of self-cleaning performance of the nano-TiO2-treated samples without precorona treatment. Since natural cotton carries limited negative charges in the aqueous solution, the interactions between fiber and particles are therefore predominated by Van de Waal's forces, rather than electrostatic forces. Van de Waal's forces are weak; therefore, most of titania nanoparticles bonded to natural cotton fibers are easily removed by washing. However, the self-cleaning property of the samples pretreated with corona has significantly been maintained. By comparing the samples treated with corona and those without pre-corona treatment, it can be concluded that corona treatment significantly contributes to adsorption and stabilization of TiO2 nanoparticles on the cotton fabrics. After corona treatment, the dominant interaction between nanoparticles and the surface of the fiber shifts from Van de Waal's forces for uncharged objects to electrostatic attraction for charged objects. Electrostatic attraction is a long distance force strong enough to attract the nanoparticles and to compensate the surface charges of the substrates [26].

3.3 Antibacterial assay

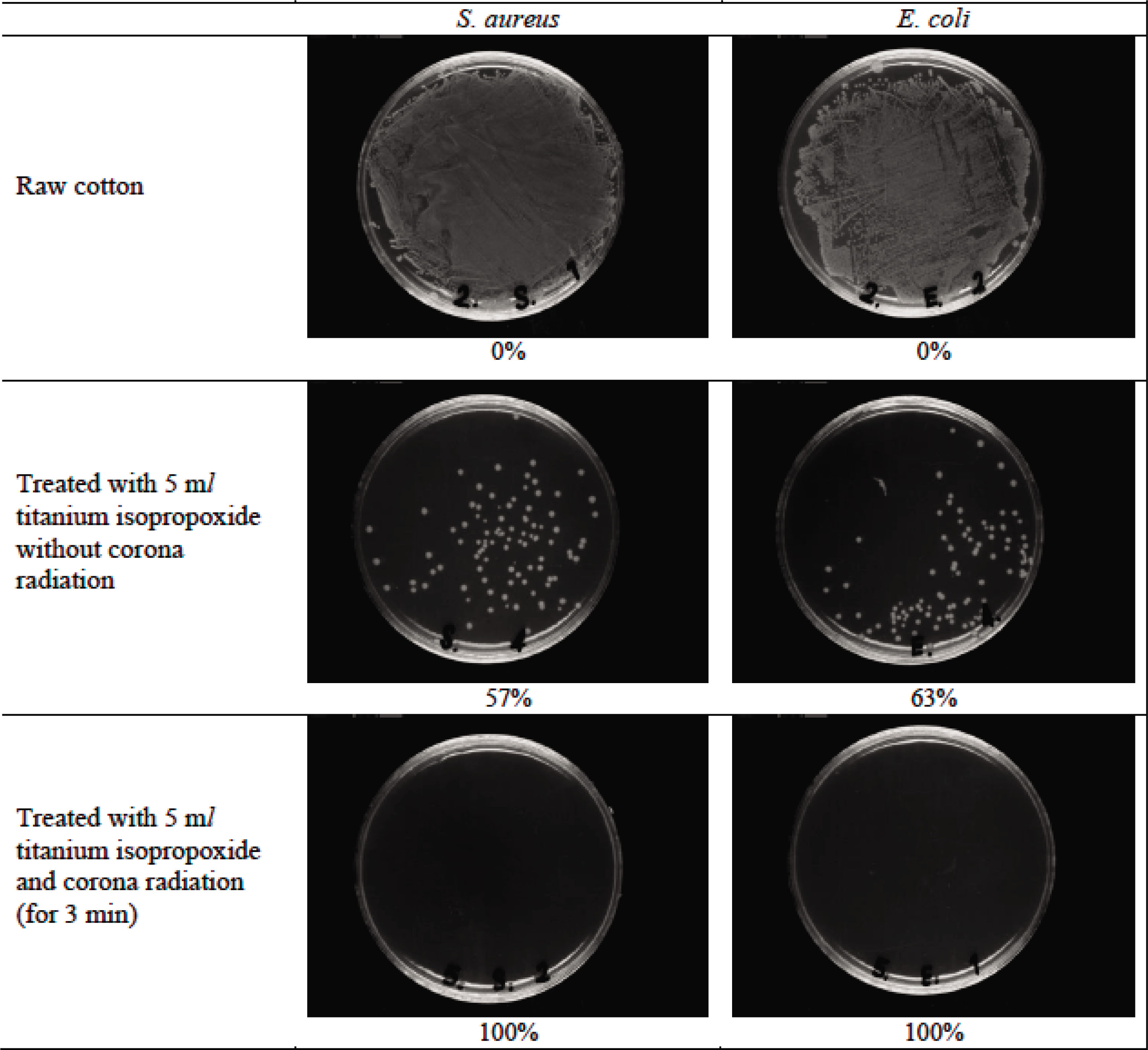

Antibacterial activities of raw and treated cotton samples were assessed quantitatively by the AATCC agar diffusion test method 100, the results of which are given in Figure 5. The raw cotton fabrics provide a suitable media for growth of microorganisms, which is due to the fact that raw cotton does not have any antibacterial agent in its surface. The nano-TiO2-treated cotton sample exhibited 57% of reduction for S. aureus and 63% of reduction for E. coli. Corona pretreatment had a tangible effect on antibacterial activity of treated cotton fabrics. The nano-TiO2-treated sample with corona radiation exhibited 100% of reduction for both S. aureus and E. coli. Improved antibacterial properties of corona-treated fabrics can be attributed to higher fiber surface roughness and increased hydrophilicity, which made them more accessible to titanium dioxide nanoparticles.

Antibacterial activity measurement of raw and treated cotton fabrics.

3.4 Flexibility and wettability

Time of water droplet absorption and bending length of different cotton fabrics are presented in Table 2. Loading of titanium dioxide with or without corona pretreatment in cotton fabrics led to increase in the time of water absorption due to blocking of the hydrophilic groups of cellulosic substrate by nano titanium dioxide. In addition, in comparison with raw cotton fabric, bending length values of treated cotton fabrics increased, which indicates the lower flexibility of samples.

4 Conclusion

As showed, homogeneous and stable coatings of titanium dioxide nanoparticles on cotton fabric were developed by pretreatment of the fabric with corona radiation. The corona pretreatment improves adsorption of titanium dioxide nanoparticles, and results in a stable self-cleaning and antibacterial properties of cotton fabrics. In addition, through FE-SEM and X-ray mapping images, the uniform deposition of titania nanoparticles on the surface of the corona-pretreated cotton fabrics was verified. Furthermore, the self-cleaning variation of the treated samples after consecutive washing was negligible. With regard to the method applied in this research, mass production of this product is possible.

References

[1] Hezavehi, E., Shahidi, S., Zolgharnein, P. (2015). Effect of dyeing on wrinkle properties of cotton cross-linked by Butane Tetracarboxylic Acid (BTCA) in presence of Titanium Dioxide (TiO2) Nanoparticles. Autex Research Journal, 15(2), 104–111.10.2478/aut-2014-0039Search in Google Scholar

[2] Jafari-Kiyan, A., Karimi, L., Davodiroknabadi, A. (2017). Producing colored cotton fabrics with functional properties by combining silver nanoparticles with nano titanium dioxide. Cellulose, 24(7), 3083–3094.10.1007/s10570-017-1308-8Search in Google Scholar

[3] Ayazi-Yazdi, S., Karimi, L., Mirjalili, M., Karimnejad, M. (2017). Fabrication of photochromic, hydrophobic, antibacterial, and ultraviolet-blocking cotton fabric using silica nanoparticles functionalized with a photochromic dye. Journal of the Textile Institute, 108(5), 856–863.10.1080/00405000.2016.1195088Search in Google Scholar

[4] Derakhshan, S. J., Karimi, L., Zohoori, S., Davodiroknabadi, A., Lessani, L. (2018). Antibacterial and self-cleaning properties of cotton fabric treated with TiO2/Pt. Indian Journal of Fibre & Textile Research, 43(3), 344–351.Search in Google Scholar

[5] Liu, L., Huang, Z., Pan, Y., Wang, X., Song, L., et al. (2018). Finishing of cotton fabrics by multi-layered coatings to improve their flame retardancy and water repellency. Cellulose, 25(8), 4791–4803.10.1007/s10570-018-1866-4Search in Google Scholar

[6] Pan, G., Xiao, X., Ye, Z. (2019). Fabrication of stable superhydrophobic coating on fabric with mechanical durability, UV resistance and high oil-water separation efficiency. Surface and Coatings Technology, 360, 318–328.10.1016/j.surfcoat.2018.12.094Search in Google Scholar

[7] Li, Z., Dong, Y., Li, B., Wang, P., Chen, Z., et al. (2018). Creation of self-cleaning polyester fabric with TiO2 nanoparticles via a simple exhaustion process: Conditions optimization and stain decomposition pathway. Materials & Design, 140, 366–375.10.1016/j.matdes.2017.12.014Search in Google Scholar

[8] Behzadnia, A., Montazer, M., & Rad, M. M. (2015). In situ photo sonosynthesis and characterize nonmetal/metal dual doped honeycomb-like ZnO nanocomposites on wool fabric. Ultrasonics Sonochemistry, 27, 200–209.10.1016/j.ultsonch.2015.05.021Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[9] Moazami, A., Montazer, M. (2016). A novel multifunctional cotton fabric using ZrO2 NPs/urea/CTAB/MA/SHP: introducing flame retardant, photoactive and antibacterial properties. Journal of the Textile Institute, 107(10), 1253–1263.10.1080/00405000.2015.1100806Search in Google Scholar

[10] Perelshtein, I., Applerot, G., Perkas, N., Wehrschetz-Sigl, E., Hasmann, A., et al.. (2008). Antibacterial properties of an in situ generated and simultaneously deposited nanocrystalline ZnO on fabrics. ACS Applied Materials & Interfaces, 1(2), 361–366.10.1021/am8000743Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[11] Mohammadi, M., Karimi, L., Mirjalili, M. (2016). Simultaneous synthesis of nano ZnO and surface modification of polyester fabric. Fibers and Polymers, 17(9), 1371–1377.10.1007/s12221-016-6497-5Search in Google Scholar

[12] Khajavi, R., Berendjchi, A. (2014). Effect of dicarboxylic acid chain length on the self-cleaning property of nano-TiO2-coated cotton fabrics. ACS Applied Materials & Interfaces, 6(21), 18795–18799.10.1021/am504489uSearch in Google Scholar PubMed

[13] Karimi, L., Mirjalili, M., Yazdanshenas, M. E., Nazari, A. (2010). Effect of nano TiO2 on self-cleaning property of cross-linking cotton fabric with succinic acid under UV irradiation. Photochemistry and Photobiology, 86(5), 1030–1037.10.1111/j.1751-1097.2010.00756.xSearch in Google Scholar PubMed

[14] Yu, M., Wang, Z., Liu, H., Xie, S., Wu, J., et al. (2013). Laundering durability of photocatalyzed self-cleaning cotton fabric with TiO2 nanoparticles covalently immobilized. ACS Applied Materials & Interfaces, 5(9), 3697–3703.10.1021/am400304sSearch in Google Scholar PubMed

[15] Kale, B. M., Wiener, J., Militky, J., Rwawiire, S., Mishra, R., et al. (2016). Coating of cellulose-TiO2 nanoparticles on cotton fabric for durable photocatalytic self-cleaning and stiffness. Carbohydrate Polymers, 150, 107–113.10.1016/j.carbpol.2016.05.006Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[16] Hu, J., Gao, Q., Xu, L., Wang, M., Zhang, M., et al. (2018). Functionalization of cotton fabrics with highly durable polysiloxane–TiO2 hybrid layers: potential applications for photo-induced water–oil separation, UV shielding, and self-cleaning. Journal of Materials Chemistry A, 6(14), 6085–6095.10.1039/C7TA11231ASearch in Google Scholar

[17] Radetić, M., Ilić, V., Vodnik, V., Dimitrijević, S., Jovančić, P., et al. (2008). Antibacterial effect of silver nanoparticles deposited on corona-treated polyester and polyamide fabrics. Polymers for Advanced Technologies, 19(12), 1816–1821.10.1002/pat.1205Search in Google Scholar

[18] Nourbakhsh, S., Parvinzadeh, M., Jafari, S. (2018). Comparison between nano and micro silicon softener on corona discharge-treated cotton fabric. Journal of Industrial Textiles, 47(7), 1757–1768.10.1177/1528083717708484Search in Google Scholar

[19] Rezaei, F., Maleknia, L., Valipour, P., Chizari Fard, G. (2016). Improvement properties of nylon fabric by corona pre-treatment and nano coating. Journal of the Textile Institute, 107(10), 1223–1231.10.1080/00405000.2015.1100394Search in Google Scholar

[20] Tomšič, B., Vasiljević, J., Simončič, B., Radoičić, M., Radetić, M. (2017). The influence of corona treatment and impregnation with colloidal TiO2 nanoparticles on biodegradability of cotton fabric. Cellulose, 24(10), 4533–4545.10.1007/s10570-017-1415-6Search in Google Scholar

[21] Mirjalili, M., Karimi, L., Barari-tari, A. (2015). Investigating the effect of corona treatment on self-cleaning property of finished cotton fabric with nano titanium dioxide. Journal of the Textile Institute, 106(6), 621–628.10.1080/00405000.2014.932058Search in Google Scholar

[22] Mihailović, D., Šaponjić, Z., Radoičić, M., Lazović, S., Baily, C. J., et al. (2011). Functionalization of cotton fabrics with corona/air RF plasma and colloidal TiO2 nanoparticles. Cellulose, 18(3), 811–825.10.1007/s10570-011-9510-6Search in Google Scholar

[23] Shahidi, S., Rezaee, H., Rashidi, A., Ghoranneviss, M. (2018). In situ synthesis of ZnO Nanoparticles on plasma treated cotton fabric utilizing durable antibacterial activity. Journal of Natural Fibers, 15(5), 639–647.10.1080/15440478.2017.1349714Search in Google Scholar

[24] Ohno, T., Tokieda, K., Higashida, S., Matsumura, M. (2003). Synergism between rutile and anatase TiO2 particles in photocatalytic oxidation of naphthalene. Applied Catalysis A: General, 244(2), 383–391.10.1016/S0926-860X(02)00610-5Search in Google Scholar

[25] Zohoori, S., Karimi, L., Ayaziyazdi, S. (2014). A novel durable photoactive nylon fabric using electrospun nanofibers containing nanophotocatalysts. Journal of Industrial and Engineering Chemistry, 20(5), 2934–2938.10.1016/j.jiec.2013.10.062Search in Google Scholar

[26] Song, J., Wang, C., Hinestroza, J. P. (2013). Electrostatic assembly of core-corona silica nanoparticles onto cotton fibers. Cellulose, 20(4), 1727–1736.10.1007/s10570-013-9922-6Search in Google Scholar

© 2021 Mojtaba Aalipourmohammadi et al., published by Sciendo

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Photostability of TiO2-Coated Wool Fibers Exposed to Ultraviolet B, Ultraviolet A, and Visible Light Irradiation

- Chemical Hand Warmers in Protective Gloves: Design and Usage

- The Removal of Reactive Red 141 From Wastewater: A Study of Dye Adsorption Capability of Water-Stable Electrospun Polyvinyl Alcohol Nanofibers

- A Review of Contemporary Techniques for Measuring Ergonomic Wear Comfort of Protective and Sport Clothing

- Experimental Study on Dyeing Performance and Antibacterial Activity of Silver Nanoparticle-Immobilized Cotton Woven Fabric

- Sewing Thread Consumption for Chain Stitches of Class 400 using Geometrical and Multilinear Regression Models

- The Status of Textile-Based Dry EEG Electrodes

- Comprehensive Assessment of the Properties of Cotton Single Jersey Knitted Fabrics Produced From Different Lycra States

- Prognosticating the Shade Change after Softener Application using Artificial Neural Networks

- Influence of the Structure of Seersucker Woven Fabrics on their Friction Properties

- Evaluation of Cochlospermum vitifolium Extracts as Natural Dye in Different Natural and Synthetic Textiles

- Homogeneous Coatings of Titanium Dioxide Nanoparticles on Corona-Treated Cotton Fabric for Enhanced Self-Cleaning and Antibacterial Properties

- Numerical Analysis of Large Deflections of a Flat Textile Structure with Variable Bending Rigidity and Verification of Results Using Fem Simulation

- Thermal Behavior of Aerogel-Embedded Nonwovens in Cross Airflow

- Kansei Engineering as a Tool for the Design of Traditional Pattern

Articles in the same Issue

- Photostability of TiO2-Coated Wool Fibers Exposed to Ultraviolet B, Ultraviolet A, and Visible Light Irradiation

- Chemical Hand Warmers in Protective Gloves: Design and Usage

- The Removal of Reactive Red 141 From Wastewater: A Study of Dye Adsorption Capability of Water-Stable Electrospun Polyvinyl Alcohol Nanofibers

- A Review of Contemporary Techniques for Measuring Ergonomic Wear Comfort of Protective and Sport Clothing

- Experimental Study on Dyeing Performance and Antibacterial Activity of Silver Nanoparticle-Immobilized Cotton Woven Fabric

- Sewing Thread Consumption for Chain Stitches of Class 400 using Geometrical and Multilinear Regression Models

- The Status of Textile-Based Dry EEG Electrodes

- Comprehensive Assessment of the Properties of Cotton Single Jersey Knitted Fabrics Produced From Different Lycra States

- Prognosticating the Shade Change after Softener Application using Artificial Neural Networks

- Influence of the Structure of Seersucker Woven Fabrics on their Friction Properties

- Evaluation of Cochlospermum vitifolium Extracts as Natural Dye in Different Natural and Synthetic Textiles

- Homogeneous Coatings of Titanium Dioxide Nanoparticles on Corona-Treated Cotton Fabric for Enhanced Self-Cleaning and Antibacterial Properties

- Numerical Analysis of Large Deflections of a Flat Textile Structure with Variable Bending Rigidity and Verification of Results Using Fem Simulation

- Thermal Behavior of Aerogel-Embedded Nonwovens in Cross Airflow

- Kansei Engineering as a Tool for the Design of Traditional Pattern