Abstract

The article evaluates the amount of the consumed sewing thread for women's underwear (underwear bras and panties). Based on the obtained findings, it was concluded that sewing thread amount depends enormously on the studied influential parameters. The present paper reports a contribution that allows industries and researchers to decrease the consumed amounts of sewing thread in case of women's underwear and panties The study takes into account the different stitch structures and fabric characteristics that are usually used. The effects of influential input parameters, such as fabric thickness, number of assembled layers, stitch density, and tension of the thread, are investigated. Useful models have been found and can be used by industries to accuracy predict the thread consumption for women's underwear and panties to launch the needed thread commands. The developed models use multiregressive method. In this study, the fabrics that have been considered are knitted fabrics because they are those used in women's underwear. We found that women's underwear bras consume more sewing threads than panties. Using linear regression method, good relationships (coefficients of correlation close to 1) between consumption behaviors and the investigated parameters such as fabric thickness, number of assembled layers, stitch number per centimeter, sizes and tension of threads, were found. Although, the increase of threads tension to sew female underwear decreases the consumed amount of threads, the increase of other studied parameters widely encourages the consumption values, especially for seams based on chain-stitch types.

1 Introduction

Female underwear represents a great importance for the industry and the consumer. Furthermore, despite the fact that underwear is ostensibly hidden from view, a large number of women consumers spend a great amount of money on buying underwear or bras and panties [1, 2]. Nonetheless, consuming female lingerie such as bras and panties with the purpose of experiencing feminine identity is a matter of controlling your bodily performance in social life [3]. Besides, to attempt the translation of a sexy psychological feeling, the underwear's garment should reach a relevant compromise between quality (comfort, lowest defaults, good shapes, high quality of sewing threads, sexy and original patterns, and so on) with low sewing thread consumption. In fact, sewing lingerie and underwear particularly has never been easier for many reasons [4]. First, the schedule assemblies of the overall underwear seem needing several steps to seam garments. Second, the field of fashion adapts with needs and produces social imperatives, for example, the introduction of strings or thongs that result from the need for invisible underwear to better support outerwear, especially as they become tighter and more revealing. Third, the underwear pattern manufacturing systems are not adapted to each body shape because, for each model, different results are acquired, which increases the complexity of the studied underwear patterns and fabrics [5]. Thus, the consumption of underwear can also be seen as a negotiation within a structured system. Moreover, lingerie fabrics are warp and weft knitted samples, which is why they remain delicate and require more attention because of their high extensibility, deformations, and high price of fabrics. In spite of these difficulties during seam processes particularly, some researchers proposed the use strictly of the guidance of underwear's patterns to be sewed and the different shapes of the undies suit most body types and there are different styles for women's comfort [4]. In contrast with these suggestions, the problems related to underwear's sewing thread consumption remained unresolvable, due to many parameters affecting the underwear quality such as size, esthetic, shape, thread tension, stitch length, the seam balance, blend compositions, fabric thickness, and its compressive modulus [4, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10]. In contrast with research in the literature review [6, 11], there is no study drawing attention to the consumed thread amount of sewing thread of knitted garments such as underwear bra or panties. Indeed, excepting some tentative published thread consumption charts for stitch types and fabric thicknesses by the Union Special sewing machine company, for example, and some works regarding bras [1, 12, 13], the sewing consumption behavior for female lingerie remains untreated sufficiently by researchers yet because many influential input parameters of sewing conditions that have been omitted and neglected [7, 8, 9, 14]. After a literature review, no articles have been found dealing with our specific subject the sewing thread consumption of women's underwear and panties. Therefore, the proposed approach seems to be relevant regarding this industrial problematic. This approach will be useful for the industries and the researchers.

2 Materials and methods

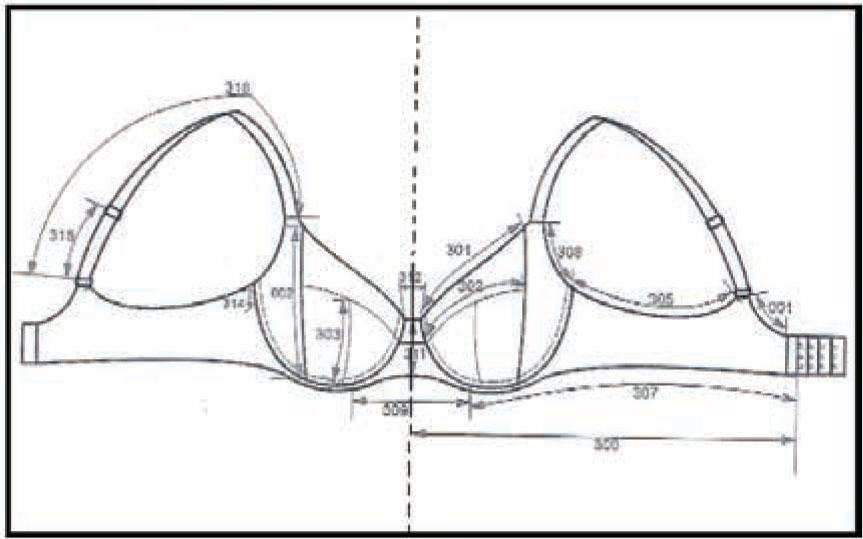

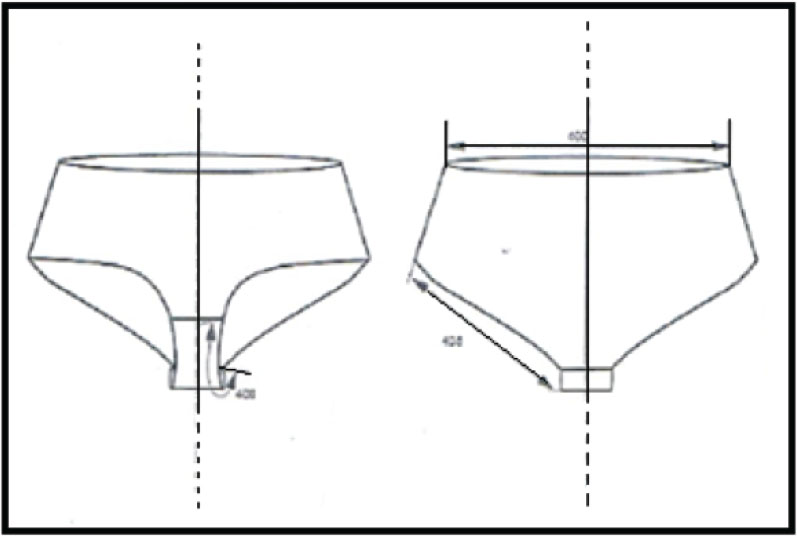

To sew the female underwear garments (bras and panties) as shown in Figures 1 and 2, respectively. Table 1 gives the characteristics of sewing threads used.

Studied women's underwear bra

Studied women's panty

Characteristics of 4 sewing threads used

| Characteristics | Sewing threads | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | |

| Structure | Twisted | Twisted | Assembled filaments | Assembled filaments |

| Number of ends | 3 | 2 | – | – |

| Sens of twist | Z | Z | – | – |

| Linear density (tex) | 24 | 28 | 21 | 18 |

| Composition | 70% PES, 30% CO | 100% PES | 100% PES | 100% PES |

Openwork structures are used for fancy laces and nets for dress wear, underwear (see Figure 3), nightwear, lingerie, sportswear, linings, blouses and shirts, drapes and curtains, and industrial fabrics.

Bras and briefs made from elastic raschel lace fabric. Note also the scalloped, elasticated edge trimmings

However, Table 2 presents the main characteristics of different knitted fabrics. To analyze the consumed thread during sewed women's underwear and panty samples, some influential inputs are selected [8].

Knitted fabric samples tested and their characteristics

| Tested knitted fabrics | Norm used | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristics | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | |

| Plain structure | Rib 1 ′ 1 | Tulle | Guilloché ordinaire 1 & 1 | Rib 1 ′ 1 | Double jersey | Jersey + foam | Single jersey | Single jersey | Single jersey | – |

| Blend | 76% PAM 24% El | 82% PAM 18% El | 83.5% PAM 16.5%El | 61% PAM 39% El | 75% PAM 25% El | 85% PAM 15% El | 74% PAM 26% El | 72.1% PAM 27.9% El | 60% PAM 40% El | – |

| M (g/m2) (CV%) | 85 (0.71%) | 175.2 (0.28%) | 59.33 (1.17%) | 198 (0.22%) | 465 (0.93%) | 328.7 (0.29%) | 156 (0.34%) | 63.9 (0.20%) | 201 (0.41%) | EN 12127 |

| Th (mm) (CV%) | 0.277 (1.76%) | 0.429 (0.88%) | 0.34 (1.55%) | 0.51 (0.74%) | 2.5 (0.96%) | 3.14 (0.56%) | 0.42 (1.44%) | 0.46 (1.15%) | 0.46 (1.04%) | ISO 5084 |

M, mass of knitted fabric sample; Th, thickness of knitted fabric; –, no norm standard used.

To evaluate the consumed thread of the studied female underwear, different sewing machines based on chain-stitch/lockstitch, overegged-stitch, and cover stitch were used. In fact, for experimental analysis, different input parameters such as thickness of knitted fabric (or layer's thickness, Fth), underwear's sizes, number of seamed layers, number of stitches per centimetre, SL (or density of stitches per seam length), tension of sewing threads (Tnl or Tbb or Tlp), and type of sewing stitch were investigated. All the effects on the consumption behaviors were also analyzed [10]. Keeping the same experimental conditions to obtain similar seamed samples for all tests, sewed knitted fabrics to made underwear's using basic stitch types (type 301; type 502, 504, and 505; and type 602) by varying the tensions of needle, Tnl and bobbin, Tbb or loopers, and Tlp, are investigated. In addition to the suitable adjustments, requested by the Juki 252-F manufacturer's sewing machine, seam length (=10 cm) of each sample was cut and sewn. According to literature [14] of panty's consumption, the weight fabric parameter presents a nonnegligible effect (=10.18%) when weight of seamed fabric increases. Then, the seam was unraveled to get the needle, the bobbin, or looper threads consumed in 10 cm length. After that, the consumed amount of sewing thread was measured to determine its length and the mean value of 10 tests within their relative CV% are carried out. Overall samples were conditioned for 24 hours in standard atmospheric laboratory conditions. Thus, the total sum of threads after unstitching was determined as function of each influential input investigated. Before and after stitching the specimens, all conditions are regulated and adjusted as recommended by Juki manufacturer to obtain a good sewing quality appearance of sewed samples.

In the present study, the underwear bras and panties are seamed using 2-thread overegged type 502, 3-thread overegged type 504, 4-thread overegged type 505, cover-stitch type 602, and lockstitch types 301 and 304. As shown in Table 1, the chosen levels for these studied underwear's are used to cover a maximum investigated underwear and panties made by a famous industrial company. Besides, for overall studied female underwear, the linear density or count of needle thread (100% PES) is 24tex and those of looper/bobbin threads are assembled filaments (18tex). The type of sewing thread (twisted or assembled) affects the consumption value [14]. Needle type used is B63 SUK within linear density equal to Nm70. Different women's panty sizes as given in literature survey are given by Table 4.

Studied parameters and their different levels as function of type of sewing stitch

| Stitch/cm, SL | Thread Tension, Tt (N) | Number of layers | Fabric thickness, Fth (mm) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 301/304 | 502 | 504 | 505 | 602 | ||||

| Levels | 2 | 0.09 | 0.046 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.03 | 1 | 0.27 |

| 9 | 1.9 | 0.26 | 0.45 | 0.73 | 0.58 | 5 | 3.14 | |

Women's panties sizes

| Panties sizing | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hip measure | 34–37 | 38–41 | 42–45 | 46–49 | 50–53 | 54–57 |

| Order panty size | 4/5 | 6/7 | 8/9 | 10/11 | 12/13 | 14/15 |

| P | S | M | L | XL | – | |

| Hip measure | 36–37 | 38–39 | 40–41 | 42–43 | 44–45 | 46–47 |

| Order panty size | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 |

In the present work, different sizes for both women's panties and bras are studied and their consumption values are also investigated to discuss the evolutions of the female underwear consumption behaviors as function of some parameters as breast shapes [1, 2, 3, 4, 5]. Indeed, a Taguchi experimental design was applied to limit the number of tests.

3 Results and discussion

The effect of all selected parameters on the thread consumption of studied knitted fabrics (9 samples) to sew women's bras and panties are investigated. By changing level values, the contribution of each influential input parameter can be widely evaluated and deeply discussed. Nevertheless, to improve the results, the regression analysis is conducted and the coefficients of determination values are discussed. All parameter contributions on the sewing thread consumptions are analyzed to explain the behavior of women sewed underwear bra and panty.

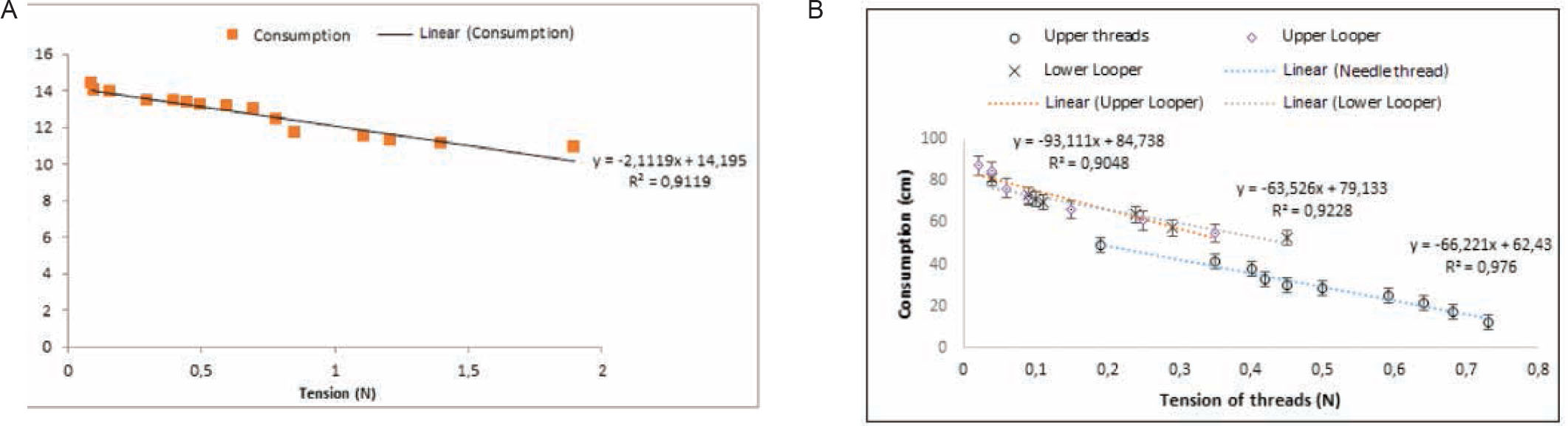

3.1 Influence of tension of sewing threads on the consumption behavior

Figure 4 shows the evolutions of the consumed thread amount as function of the tension of threads during and after seaming. Findings are carried out under specified sewing conditions, whereby needle(s) and bobbin or looper(s) thread tensioner adjustment, sewing speed, number of layers, fabric quality, and sewing thread quality were varied to investigate the effect of studied factors on the needle(s) and bobbin/looper(s) thread tensions. According to results, variations were detected in the peak tensions according to the sewing conditions, as proved by many researchers [7, 8, 9]. From the analysis of the data obtained, linear regression equations were derived to predict, with a good degree of accuracy (R = 0.955), the consumption values as function of the tensions generated, according to the sewing conditions.

Consumption behavior as function of tension of sewing threads: (a) Case of 502 and (b) Case of 504 or 512

For each sewing machine used (see Figure 4) to sew women's underwear bras and panties, a relationship between the consumed amount of thread and tensions generated was derived and discussed. By comparing between overall evolutions of the consumption behaviors, it may be concluded that the amount of the sewing thread consumed has a good correlation when tension of threads increases [9, 15, 16, 17]. Despite the remarkable increase in the consumption of sewing threads for sewing different knitted fabrics, the linear regression analysis shows fruitful relationships between the increase in thread tension and the consumption behaviors for the studied women’'s underwear (see Figure 4a and b). Many researchers [6, 18, 19, 20] determined and analyzed the sewing thread performance in terms of seam efficiency, pucker, slippage, and needle cutting index in the light of the dimensional and mechanical properties of the fabric, thread, and seam itself. Indeed, the breaking strength, elongation of the fabric, and sewing thread had an excellent correlation with seam efficiency. Most of the researchers considered that the tensile strength of the sewing threads reduces after stitching and studied thread properties such as size, coefficient of yarn-metal friction, twist direction, number of piles, type of fiber, and fiber denier on strength reduction [11, 21, 22, 23, 24]. These properties, along with the notable effect of fabric tightness can certainly explain the origin of highly-consumed thread and wastage values as well as the decrease of sewn garment quality. Several reasons are reported in the literature such as the structural disintegration, the loss in fiber strength, and the surface wear [21, 25]. Therefore, it was reported that the tensile properties of sewing thread have a bearing with the fabric characteristics [10, 20, 26, 27, 28]. However, to achieve a good appearance and the seam properties, different parameters tied to sewing machines, stitching plain geometries, fabric characteristics, and yarn structures are investigated in the literature [29]. According to the Figures 4 and 5, all coefficients of determination are ranged from 0.892 to 0.988. These values are close to 1, traducing the effectiveness of the regression analysis to explain the relationship between tension of threads and the consumption values. The predicted values of sewing thread consumption seem acceptable. However, there are relative errors, which reflect that experimental consumed thread remained an empirical value. It incorporates some factors such as waste factor as tackled in our previous work [30, 31]. Besides, another percentage is added related to seam performance, compressibility of both sewing thread and fabrics, frictional stresses, frictional extensions, and operator manipulations that can enormously affect the quality of seamed fabrics (seam efficiency, pucker, slippage and needle cutting index in the light of the dimensional and mechanical properties of the fabric, thread and seam itself). To provide a better quality of sewing thread and high appearance of seaming fabrics, some researchers used different techniques [6, 29]. According to obtained coefficient of determination (R = 0.937), a good relationship between the consumption behavior and the tensions of looper and needle threads is found [7, 15]. Therefore, it may be concluded that the predicted values on consumed sewing thread are significant, in the experimental set-up. It can be considered widely for further optimizations explaining sufficiently the existent good relationship between sewing thread consumption and the tested inputs. Based on obtained results, it may be concluded that all consumption's evolutions have the same curve shape. Indeed, when tension of threads increases, the consumption values decrease for overall stitch types [7, 9, 16]. However, compared to overegged stitch type 516 or 504, the light decrease of the consumption value for the lockstitch type 301 is notable and remarkable. In fact, by classifying, the consumed thread amounts, all seamed samples based on lockstitch structure (301, 304, and 308) offer minimum consumption values. Nevertheless, those based on chain stitch such as overegged stitch types 502, 504, 516 or chain stitch types 401 and 406 increase the consumption values. This superiority can be justified by the high consumptions of both upper and lower loopers (proved further in the next subsections). The bobbin thread lengths per stitch are always higher than the needle thread length per stitch. The consumption values widely increase when the bobbin thread was replaced by the looper(s) thread. It increases almost linearly with the increase in feed rate from slow, medium to high, or with the change of the thread twist. This is due to the fact that at higher feed rate, the fabric is moving faster and hence the length of yarn supply from needle and bobbin per seam is increased. According to results, along with the rise in feed rate both the looper as well as the needle and the covering thread length per stitch types increases, explaining the variation of consumption behaviors. However, in case of jean trousers, to reduce the mean value of the consumed thread, it is suitable to use sewing thread composed of 2 twisted threads. Furthermore, increasing the number of twisted threads encourages a high consumption value (an average increase value of 21.82% when the sewing thread was composed of 3 twisted threads instead of only 2) [14].

Consumption evolution as function of length of stitch (or number of stitches per centimeter)

3.2 Influence of stitches/cm on the consumed thread amount behavior

Figures 5 and 6 show the evolutions of the sewing thread consumptions as function of length of stitch (or number of stitches per centimeter) using different sewing machines to sew female underwear bras and panties. Regarding all consumption's behaviors, it may be concluded that the decrease of the stitch length increases widely the consumed amount. However, compared to lockstitch type 301 (see Figure 5); the overegged stitch types 502, 504 and 512 (Figure 6a–c, respectively) consume considerably the sewing threads. This result is found using the same experimental conditions for overall tests such as seam length (=100 mm), machine's adjustments, fabric and threads’ characteristics, needle type, and so on. Based on Figure 5, an accurate relationship (R = 0.987) between the consumption values and the length of stitch to seam fabric length using lockstitch type 301 was obtained.

Evolution of consumption values as function of stitches per centimeter: (a) Case of 502, (b) case of 504, and (c) case of 512

In addition, it is clear that the increase of the number of stitches per centimeter accurately encourages the consumption value of sewing thread (see Figure 6). This result seems in good agreement with those in the literature review dealing with the consumed thread of woven fabrics [11, 32, 33, 34, 35, 36].

Based on the low coefficients of variation, CV%, it may be concluded that the mean findings are efficient and fit adequately the real values of the consumed sewing thread. Therefore, for knitted samples, the needle thread consumption remains the lowest, compared to those of loopers. Comparing all overegged-stitch types, the obtained results show that the increase of the number of sewing thread increases the consumption values. This finding can be justified by the increase of the interloped threads during seam process. Similarly, the stitch length or stitches per centimeter affects the thread consumption but its effect is not as influencing as that of the thickness of the material [17, 36, 37]. The quantification of the input factors and their relative influences on sewing thread consumption can assist for accurate prediction of sewing thread required for sewing operation in garments industry. Additionally, the stitches can be backtracked at the end of the seam, which makes the seam even more secure. The least secure stitches of all are the different thread chain stitches in class 400–600. Seam security on the women's underwear (class 500) is another important seam performance factor especially for underwear bras and panties. The securest of stitches, lockstitch, is formed by the interlocking of the threads together allowing it be ranked as the least consumed stitch type. According to some studies [37, 38], when a thread breaks in a lockstitch seam, the stitches may run back for a short distance. This depends on the longitudinal and transverse stress applied to the seam, the stretch in the fabric and the surface nature of the used thread.

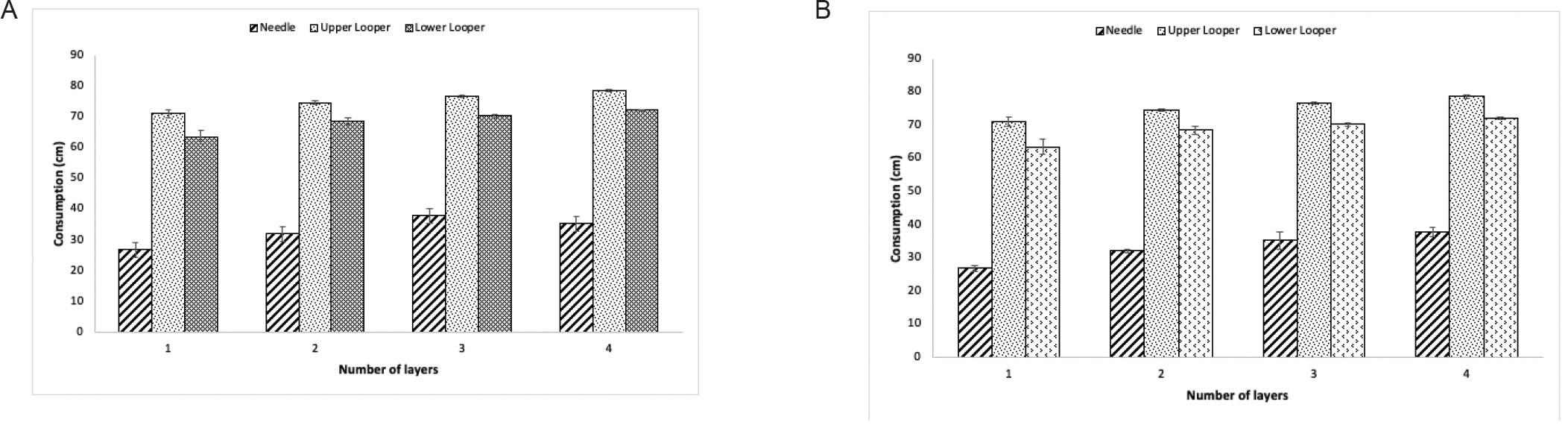

3.3 Influence of the number of layers on the consumption behavior

Figures 7 and 8 show the different evolutions of the consumption values when the number of assembled layers of knitted fabrics vary. Based on these behaviors, the increase in the assembled layers accurately increases the consumed amount of sewing thread. The effect of fabric tightness and certain thread properties like its size, coefficient of yarn-metal friction, twist direction, number of piles, type of fiber, and fiber denier on strength reduction are studied and found to influence the severity of strength reduction of the thread [21].

Evolution of consumed thread amount as function of number of layers: (a) Case of 301 and (b) Case of 502

Evolution of consumed thread amount as function of number of layers: (a) case of 504 and (b) case of 512

Furthermore, there is no comparison that can be mentioned between the consumed thread using lockstitch type 301 and those relative to other overegged-stitch or cover-stitch types. Indeed, the overegged-stitch types 502, 504, and 512 and the cover-stitch type 602 (406) need more threads to develop stitch structure than for the lockstitch type 301.

Moreover, the cover-stitch 602 (or 406) gives high contributions, contrary to other extensible stitch types such as chain-stitch (class 400) and overegged stitch (class 500), which gives adequate stretch for sewing comfort stretch fabrics and providing the maximum attainable consumption values [39, 40, 41]. The high number of needle threads, complicated geometrical shapes, and the covering threads used to envelop the secure zones may explain this result. In addition, these kinds of stitch type covered considerable parts of women's underwear to decorate or seam areas by the interlocking of the threads together encouraging a high amount of threads consumption. It is concluded from sensitivity analysis that the consumed upper thread has highest significant influence on the sewing thread consumption followed by lower thread and needle thread count. Therefore, according to literature surveys [40, 41], the looper threads lengths per stitch are always higher than the needle thread length per stitch; the same remark was also saved in this study. Contrary to lockstitch type 301, 304, or 308, extensible stitch types such as chain stitch (class 400) or overegged stitch (class 500) are more suitable to sew lingerie and women's underwear. In fact, they provide adequate stretch for sewing comfort stretch and knitted fabrics and providing the maximum attainable consumption values. In addition, the underwear bras’ and panties parts are seamed using the chain stitch (type 401), overegged stitch (type 502, 503, 504, and 516), and cover-stitch (type 406) in spite of lockstitch type 301 to decorate and secure seamed zones by the interlocking of the threads together encouraging a high amount of threads.

3.4 Influence of thickness fabric on consumed thread lengths

When the thickness of fabric samples changes, the consumed thread changes considerably. Nevertheless, obtained result shows the increase of the total amount of threads (for both bobbin and needle in case of lockstitch type 301) when the density of stitch is fixed to 4 stitches/cm and the tension of thread is equal to 0.75 N. Regarding the coefficient of correlation value (R = 0.943), it may be concluded that predicted consumption values can be depicted in the studied experimental set-up. However, Figure 9 shows the consumption behaviors of all sewed threads.

Evolution of consumption value as function of thickness's fabric: (a) case of 502 and (b) case of 504

Based on these evolutions, we remarked that for overegged-stitch types especially, looper's thread lengths are higher than the needle thread ones. Sewing thread consumption has a direct relationship with the stitch density, thickness of material, and interlacing factor. This effect is very significant for stitch density and thickness of material, while it is less significant for the interlacing factor. According to earlier work [14], the contribution of the fabric thickness is considered less significant due to its slight values to the mean consumption of jean trousers, and it seems nonsignificant because its variation cannot affect considerably the mean consumption value. In contrast with this finding, we can conclude that, in case of knitted fabrics to sew women's underwear bras and panties, fabric thickness has a large and significant effect on increasing the consumed thread amount. Several reasons can explain these results such as the light thread tensions that are generally recommended in knitted fabrics [7]. Moreover, added percentages related to seam performance, fabric tightness. and compressibility of both sewing thread and knitted fabrics help the increase or the decrease of the consumption values. Nevertheless, the consumed sewing thread for looper's system is higher than the consumed sewing thread for the needle(s) as shown in Figure 9b. The interlocking loops of thread used to cover the border of fabrics on the two sides helps the length values of threads. Indeed, upper looper thread remains the highest consumer of thread followed by lower looper thread and needle one and this conclusion is valuable for the unchanged seaming conditions.

3.5 Evaluation of the consumed thread for women's underwear bra sizes

The results obtained to evaluate the sewing thread consumption to sew tested underwear bra are based on 20 samples to measure the consumed amount of thread using the schedule assembly. Stitch breadth will depend on the thickness of the sewn material [36]. To calculate the thread consumption per unit length relative to each part of women's underwear bra or panty, this equation (see Equation 1) was multiplied with the stitch density. So, Equation (1) can also be written as follow:

where N(stitch type): number of stitches calculated to carry out the theoretical consumption value of sewing thread using stitch type (e.g., 301, 304, 504, and so on) regarding the sewn garment part length, lsea: Length of the seamed part in garment, Nbs: Stitch density along basic length or number of stitch per unit of length (=1 cm) adjusted voluntary by user in specific sewing machine (class 100–600), and BSL: Basic seam length (=100 mm).

Table 5 shows the studied women's underwear bra in its different sizes. The obtained results show that the variation of the bra sizes (relative to band and bust parts) enormously affects the consumed sewing thread (see Tables 5 and 6).

Consumption

| Size ▼ | Measurements (cm) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 65 | 70 | 75 | 80 | 85 | 90 | 95 | |

| D | 977.6 | 1006.5 | 1055 | 1081.9 | |||

| E | 1013.5 | 1040.4 | 1078.4 | 1118.7 | |||

| F | 1101.2 | 1129.4 | |||||

| G | 1072.1 | 1142 | 1170.3 | ||||

| H | 1214.3 | ||||||

Assembly schedule of the women's underwear bras as function of their sizes and influential parameters

| No | Operations | Sewing machine | Consumption values relative to bra's size (cm) | SL (stitch/cm) | Fth (cm) | Nt | Tnl (N) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| D | E | F | G | H | ||||||||||||||||

| 75 | 80 | 90 | 95 | 70 | 75 | 80 | 90 | 80 | 85 | 65 | 80 | 85 | 85 | |||||||

| 1 | Fasten the front yocke of low bra cup | 301 | 75 | 75 | 75 | 75 | 81 | 81 | 81 | 81 | 86 | 86 | 91 | 91 | 91 | 97 | 5 | 0.67 | 2 | 0.51 |

| 2 | Fasten the middle yocke of low bra cup | 301 | 84 | 84 | 84 | 84 | 86 | 86 | 86 | 86 | 88 | 88 | 90 | 90 | 90 | 92 | 5 | 0.67 | 2 | 0.51 |

| 3 | Assemble the 2 yokes of low bra cup | 301 | 32 | 32 | 32 | 32 | 34 | 34 | 34 | 34 | 36 | 36 | 36 | 38 | 38 | 40 | 5 | 1.23 | 4 | 0.51 |

| 4 | Assemble bias binding on bra cup | 302 | 34 | 34 | 34 | 34 | 36 | 36 | 36 | 36 | 38 | 38 | 40 | 40 | 40 | 42 | 5 | 1.73 | 3 | 0.51 |

| 5 | Stitching stopping point on bra cup | 304 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 9 | 1.73 | 3 | 0.46 |

| 6 | Put the two cups up and down using inlaid method | 308 | 34 | 35.6 | 38 | 39.8 | 40 | 40.9 | 42.5 | 43 | 40 | 42 | 38 | 42 | 43.2 | 45 | 3 | 0.91 | 3 | 0.49 |

| 7 | Assemble side bra cup in sheath | 301 | 38 | 40.1 | 43 | 45 | 39.2 | 40.1 | 42.9 | 45.1 | 45 | 47 | 42 | 47.5 | 49.5 | 52 | 5 | 1.2 | 4 | 0.51 |

| 8 | Oversew side bra cup | 504 | 38.2 | 40.5 | 43.4 | 45.4 | 39.6 | 40.7 | 43 | 45.5 | 45.4 | 47.2 | 42.3 | 47.7 | 49.6 | 52.4 | 7 | 1.2 | 4 | 0.43 |

| 9 | Top-stitching side bra cup | 304 | 38.1 | 40.1 | 43.1 | 45 | 39.2 | 40.1 | 42.9 | 45.1 | 45 | 47 | 42.2 | 47.5 | 49.5 | 52 | 4 | 1.65 | 4 | 0.49 |

| 10 | Banding of bra cup | 301 | 55.4 | 56.3 | 58.4 | 59 | 57.5 | 59.3 | 63.9 | 64.7 | 65 | 66.9 | 70 | 71.5 | 72.4 | 75 | 5 | 0.45 | 2 | 0.51 |

| 11 | Put bias binding on band | 301 | 24.5 | 24.5 | 24.5 | 24.5 | 24.5 | 24.5 | 24.5 | 24.5 | 24.5 | 24.5 | 24.5 | 24.5 | 24.5 | 24.5 | 3 | 0.31 | 2 | 0.51 |

| 12 | Assemble basque on band | 301 | 2.5 | 2.5 | 2.5 | 2.5 | 2.5 | 2.5 | 2.5 | 2.5 | 2.5 | 2.5 | 2.5 | 2.5 | 2.5 | 2.5 | 4 | 0.5 | 2 | 0.51 |

| 13 | Fasten band | 301 | 74.3 | 75.2 | 78.5 | 79.8 | 76.3 | 77.8 | 78.6 | 79.9 | 78.5 | 80.1 | 79.8 | 81.5 | 82.6 | 85.2 | 4 | 0.65 | 2 | 0.51 |

| 14 | Border low band | 304 | 54.5 | 57.4 | 64 | 67.7 | 50.3 | 53.7 | 57 | 63.6 | 56.9 | 60.4 | 46.4 | 56.6 | 60.2 | 59.9 | 4 | 1.48 | 3 | 0.35 |

| 15 | Fill low band | 304 | 54.5 | 57.4 | 64 | 67.7 | 50.3 | 53.7 | 57 | 63.6 | 56.9 | 60.4 | 46.4 | 56.6 | 60.2 | 59.9 | 4 | 1.98 | 4 | 0.42 |

| 16 | Put bias binding on yocke | 301 | 1.6 | 1.6 | 1.6 | 1.6 | 1.6 | 1.6 | 1.6 | 1.6 | 1.6 | 1.6 | 1.6 | 1.6 | 1.6 | 1.6 | 4 | 0.15 | 3 | 0.55 |

| 17 | Assemble yoke on basque | 301 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 4 | 0.46 | 3 | 0.56 |

| 18 | Assemble bias binding on basque | 301 | 2.4 | 2.4 | 2.4 | 2.4 | 2.4 | 2.4 | 2.4 | 2.4 | 2.4 | 2.4 | 2.4 | 2.4 | 2.4 | 2.4 | 4 | 0.67 | 3 | 0.53 |

| 19 | Fasten a part of the assembly bra cup with end back | 301 | 62.3 | 64.3 | 67.2 | 68.9 | 67.2 | 68.9 | 69.4 | 72.2 | 70.1 | 72.5 | 71.2 | 73.4 | 74 | 79.2 | 4 | 1.32 | 2 | 0.53 |

| 20 | Assemble bra cup on band | 301 | 61.3 | 63.1 | 66.1 | 67.5 | 67.3 | 69.4 | 73.6 | 75.4 | 75.9 | 76.1 | 75.3 | 78.6 | 80.1 | 84.2 | 4 | 2.4 | 4 | 0.55 |

| 21 | Border under arms | 304 | 28.7 | 30.8 | 35.2 | 38 | 25.5 | 27.7 | 30.1 | 34.7 | 28.4 | 31.3 | 20.4 | 27.6 | 30.5 | 29.8 | 4 | 3.25 | 3 | 0.45 |

| 22 | Assemble staples bra | 304 | 8 | 8 | 11 | 11 | 6 | 8 | 8 | 11 | 8 | 11 | 6 | 8 | 11 | 11 | 14 | 3.76 | 3 | 0.42 |

| 23 | Prepare bias for strapping | 401 | 66 | 69.2 | 71 | 72.5 | 72.3 | 74.4 | 78.6 | 80.4 | 80.9 | 81.1 | 80.3 | 83.6 | 85.1 | 89.2 | 4 | 2.75 | 2 | 0.44 |

| 24 | Strap low part of bra cup | 302 | 66 | 69.2 | 71 | 72.5 | 72.3 | 74.4 | 78.6 | 80.4 | 80.9 | 81.1 | 80.3 | 83.6 | 85.1 | 89.2 | 5 | 3.77 | 3 | 0.51 |

| 25 | Ganser collar | 304 | 30.9 | 31.9 | 33.7 | 34.7 | 31.1 | 31.9 | 32.9 | 34.7 | 33.9 | 34.9 | 32.1 | 34.9 | 35.9 | 36.9 | 4 | 2.68 | 3 | 0.49 |

| 26 | Stitching stopping point on under arms | 301 | 1.6 | 1.6 | 1.6 | 1.6 | 1.6 | 1.6 | 1.6 | 1.6 | 1.6 | 1.6 | 1.6 | 1.6 | 1.6 | 1.6 | 14 | 3.4 | 3 | 0.56 |

| 27 | Assembly side in front of bra strap | 301 | 1.6 | 1.6 | 1.6 | 1.6 | 1.6 | 1.6 | 1.6 | 1.6 | 1.6 | 1.6 | 1.6 | 1.6 | 1.6 | 1.6 | 14 | 4.9 | 3 | 0.55 |

| 28 | Assembly side behind bra strap | 301 | 1.6 | 1.6 | 1.6 | 1.6 | 1.6 | 1.6 | 1.6 | 1.6 | 1.6 | 1.6 | 1.6 | 1.6 | 1.6 | 1.6 | 14 | 4.9 | 3 | 0.6 |

| 29 | Put pattern | 301 | 1.6 | 1.6 | 1.6 | 1.6 | 1.6 | 1.6 | 1.6 | 1.6 | 1.6 | 1.6 | 1.6 | 1.6 | 1.6 | 1.6 | 5 | 3.97 | 3 | 0.55 |

| Actual consumption values (cm) | 977.6 | 1006.5 | 1055 | 1081.9 | 1013.5 | 1040.4 | 1078.4 | 1118.7 | 1101.2 | 1129.4 | 1072.1 | 1142 | 1170.3 | 1214.3 | ||||||

| Theoretical consumption values (cm) | 980.1 | 1010.6 | 1043 | 1091 | 1020.3 | 1041.7 | 1080.2 | 1120.1 | 1111.5 | 1132.8 | 1097 | 1150 | 1177.4 | 1200.9 | ||||||

| Errors (%) | 0.25 | 0.41 | 1.14 | 0.84 | 0.67 | 0.12 | 0.17 | 0.12 | 0.93 | 0.30 | 2.32 | 0.70 | 0.60 | 1.10 | ||||||

However, our result shows the good relationship (R = 0.990) between actual and theoretical consumption values using statistical method. This result seems more accurate than it is suggested by A&E’'s [42], which considers that the estimated thread consumption for a sewn women's bra (using his ANECALC tool) is accurate to 2%–3% of the actual thread. This obtained result widely encourages the industries to anticipate and predict the consumption values of women's underwear bras as well as some bra's sizes (see Table 6). As the coefficient of regression is very close to 100% (or coefficient of determination close to 1), the prediction of the consumed amount of women's underwear bra seems fruitful. Overall error values are very significant and reflect the accuracy of the analysis.

3.6 Evaluation of the consumed thread for women's panty sizes

To evaluate the sewing thread consumption to sew studied women's panty

Assembly schedule of studied women's panty size XS

| No | Operation | Sewing machine | Women's panty sizes | SL (stitch/cm) | Fth (mm) | Nl. | Tnl (N) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| XS | S | M | L | XL | |||||||||

| 1 | Oversew the panty elastic bottom | 504 | 29.00 | 29.00 | 29.00 | 29.00 | 29.00 | 7 | 1.14 | 3 | 0.45 | 36.60* | 45.01 |

| 73.30♣ | 66.23 | ||||||||||||

| 2 | Hem bottom of panty | 304 | 29.00 | 29.00 | 29.00 | 29.00 | 29.00 | 4 | 1.89 | 4 | 0.35 | 42.60 | 67.40 |

| 3 | Oversew the 2 yokes of the back of panty | 505 | 16.00 | 17.00 | 18.00 | 19.00 | 20.00 | 7 | 0.94 | 2 | 0.5 | 47.80 | 45.33 |

| 80.50 | 67.45 | ||||||||||||

| 4 | Oversew the 2 yokes of the front of panty | 505 | 10.00 | 11.00 | 12.00 | 13.00 | 14.00 | 7 | 0.94 | 2 | 0.5 | 46.20 | 45.33 |

| 76.30 | 67.45 | ||||||||||||

| 5 | Oversew front waist | 504 | 44.50 | 46.50 | 48.50 | 50.50 | 52.50 | 7 | 0.47 | 1 | 0.5 | 52.30 | 54.13 |

| 79.60 | 69.65 | ||||||||||||

| 6 | Oversew back waist | 504 | 42.50 | 44.50 | 46.50 | 48.50 | 50.50 | 7 | 0.47 | 1 | 0.5 | 49.50 | 49.88 |

| 75.80 | 69.65 | ||||||||||||

| 7 | Sew the 2 stickers | 301 | 0.80 | 0.80 | 0.80 | 0.80 | 0.80 | 4 | 0.86 | 2 | 0.65 | 06.50 | 08.37 |

| 8 | Sew sticker on garment | 301 | 1.50 | 1.50 | 1.50 | 1.50 | 1.50 | 4 | 1.03 | 3 | 0.65 | 07.00 | 10.17 |

| 9 | Assemble bottom of panty on back and front of garment | 505 | 6.00 | 6.50 | 7.00 | 7.50 | 8.00 | 7 | 1.2 | 3 | 0.5 | 41.40 | 40.76 |

| 60.10 | 65.24 | ||||||||||||

| 10 | Top-stitching the hole (bottom of panty, back and front of garment) | 301 | 5.50 | 6.00 | 6.50 | 7.00 | 7.50 | 4 | 1.91 | 3 | 0.65 | 15.90 | 19.79 |

| 11 | Assemble side | 505 | 14.00 | 16.00 | 18.00 | 20.00 | 22.00 | 7 | 0.94 | 2 | 0.5 | 42.30 | 45.33 |

| 66.90 | 67.45 | ||||||||||||

| 12 | Elastic waist | 406 | 72.40 | 76.80 | 81.80 | 87.40 | 93.00 | 7 | 1.98 | 2 | 0.3 | 35.60 | 30.44 |

| 89.60 | 87.46 | ||||||||||||

| 13 | Stitching stopping point on waist | 301 | 1.20 | 1.20 | 1.20 | 1.20 | 1.20 | 9 | 1.76 | 2 | 0.65 | 07.00 | 8.420 |

| 14 | Stitching stopping point on legs | 301 | 1.20 | 1.20 | 1.20 | 1.20 | 1.20 | 9 | 1.94 | 2 | 0.65 | 09.30 | 8.450 |

| Total consumption values (cm) | 1042.10 | 1039.47 | |||||||||||

| Error value (%) | 0.25 | ||||||||||||

- *

Needle thread consumption value.

- †

Bobbin/looper thread(s) consumption value.

Using the same expression of error, the difference between statistical and experimental consumption can be identified for each seaming step of women's underwear bra or panty (see Table 7). Besides, obtained finding presents a fruitful relationship (R = 0.958) between actual and theoretical consumption values. This result helps industrials to find the suitable predictable consumed thread amount for women's panties. For the smaller sizes of women's panties, the consumed amount of sewing thread is considerable. Despite the long schedule of the assembly of underwear bra (29 operations), the sewing consumption values for smaller sizes of women's panties, are higher than the sewing consumption values for the larger sizes of underwear bras. The short-seamed lengths in different parts of the underwear bra can explain this finding in spite of sizes differences. However, for women's panty, there are a large length to seam in different parts and so, it consumes more sewing threads than underwear bra. In spite of the minimal number of seaming operations of women's panty (only 14 steps in this analysis), the total consumed length of thread without wastage equal to 1280.1 cm for the XS’ size of panty.

4 Conclusions

To evaluate the sewing thread consumption for women underwear's, some underwear bras and panties were investigated based on some influential input parameters. Considering the basic seam length for the most useful stitch types to sew women's underwear bras and panties, the studied knitted samples were analyzed. The results show that the consumed amount of sewing thread to make female underwear's increases when overegged-stitches and cover-stitch types are used. Compared to lockstitch type 301, overegged stitches type 502, 504, and 512 highly consume threads. By comparing the consumption values, results show that the amount of thread to seam underwear bras remains higher than it is for panties. The several seaming operations and the complexity of assembly parts explain this superiority accurately. Nevertheless, the theoretical (using statistical multilinear regression method) and experimental consumptions (using stitching and unstitching methods) are compared and discussed. Regarding the effectiveness of results (error of accuracy <2% for women's bras) based on the coefficients of regression, industrials of women's underwear can successfully predict their consumed amount, in the studied experimental design of interest. Besides, all investigated input parameters that cover the largest experimental designs of interest remain influential and affect enormously the consumption behaviors. Therefore, the errors depicted highlights that there are always differences between experimental and theoretical findings. It may be mentioned, intuitively, that other input effects traduce these errors and should be considered such as the compressibility of knitted fabrics during seam process.

References

[1] Jantzen, C., Amy-Chinn, D., Ostergaard, P. (2006a). Doing and meaning: Towards an integrated approach to the study of women's relationship to underwear. Journal of Consumer Culture, 6(3), 379–401.10.1177/1469540506068685Search in Google Scholar

[2] Jantzen, C., Østergaard, P., Sucena Vieira C. M. (2006b). Becoming a woman to the backbone Lingerie consumption and the experience of feminine identity, Journal of Consumer Culture, 6(2), 177–202.10.1177/1469540506064743Search in Google Scholar

[3] Kowalski K., Janicka J., Massalska-Lipinska T., Nyka M. (2010). Impact of raw material combinations on the biophysical parameters and underwear microclimate of two-layer knitted materials. Fibers & Textiles in Eastern Europe, 18(5) (82), 64–70.Search in Google Scholar

[4] Gilewicz, P., Cichocka, A., Frydrych, I., (2016). Underwear for protective clothing used by founders. Fibers & Textiles in Eastern Europe, 24, 5(119), 96–99.10.5604/12303666.1215533Search in Google Scholar

[5] Tama, D., Öndogan, Z. (2014). Fitting evaluation of pattern making systems according to female body shapes. Fiber & Textile in Eastern Europe, 22, 4(106), 107–111.Search in Google Scholar

[6] Behera, B. K., Chand, S., Singh, T. G., Rathee, P. (1997). Sewability of denim. International Journal of Clothing Science and Technology, 9(2), 128–140.10.1108/09556229710168261Search in Google Scholar

[7] Horino T., Miura Y., Ando Y., Sakamoto K. (1982). Simultaneous measurement of needle thread tension and check spring motion of lockstitch sewing machine for industrial use. Journal of Textile Machinery Society Japan, 35, T30–T37.10.4188/transjtmsj.35.2_T30Search in Google Scholar

[8] Dorrity J. L., Olson L. H. (1996). Thread motion ratio used to monitor sewing machines. International Journal of Clothing Science and Technology, 8, 1–6.10.1108/09556229610109582Search in Google Scholar

[9] Ferreira F. B. N., Grosberg P., Harlock S. C. (1994a). A study of thread tensions on a lockstitch sewing machine—I. International Journal of Clothing Science and Technology, 6, 14–19.10.1108/09556229410054468Search in Google Scholar

[10] Amirbayat, J., Alagha, M. J. (1993). Further studies on balance and thread consumption of lockstitch seams. International Journal of Clothing Science and Technology, 5, 26–31.10.1108/eb003014Search in Google Scholar

[11] O’Dwyer U., Munden D. L. (1975). A study of the factors effecting the dimensions and thread consumption in 301 seams—part I. Clothing and Textiles Research Journal, 3, 3–32.Search in Google Scholar

[12] Schultz, J. (2004). Discipline and push-up: Female bodies, femininity, and sexuality in popular representations of sports bras. Sociology of Sport Journal, 21(2), 185–205.10.1123/ssj.21.2.185Search in Google Scholar

[13] Liu, Y., Wang J., Istook, W. L. (2017). Study of optimum parameters for Chinese female underwear bra size system by 3D virtual anthropometric measurement. Journal of Textile Institute, 108(6), 877–882.10.1080/00405000.2016.1195954Search in Google Scholar

[14] Jaouachi, B., Khedher, F. (2015). Evaluation of sewed thread consumption of jean trousers using neural network and regression methods. Fibers & Textiles in Eastern Europe, 23, 3(111), 91–96.10.5604/12303666.1152518Search in Google Scholar

[15] Kamata Y., Kinoshita R., Ishikawa S., Fujisaki K. (1984). Disengagement of needle thread from rotating hook, effects of its timing on tightening tension, industrial single-needle lockstitch sewing machine. Journal of Textile Machinery Society Japan, 30, 40–49.10.4188/jte1955.30.40Search in Google Scholar

[16] Ferreira F. B. N., Grosberg P., Harlock S. C. (1994c). A study of thread tensions on a lockstitch sewing machine—III. International Journal of Clothing Science and Technology, 6, 39–42.10.1108/09556229410074592Search in Google Scholar

[17] Ghosh S., Chavhan V. (2014). A geometrical model of stitch length for lockstitch seam. Indian Journal of Fiber & Textile Research, 39, 153–156.Search in Google Scholar

[18] Miyuki, M., Masako, N. (1994). Investigation of the performance of sewing thread. International Journal of Clothing Science and Technology, 6(2/3), 20–27.10.1108/09556229410063512Search in Google Scholar

[19] Prabir, J. (2011). Assembling technologies for functional garments—An overview. Indian Journal of Fiber & Textile Research, 36, 380–387.Search in Google Scholar

[20] Jonaitiene V., Stanys S. (2005). The analysis of the seam strength characteristics of the PES-PTFE air-jet-textured sewing threads. International Journal of Clothing Science and Technology, 17(3–4), 264–271.10.1108/09556220510590966Search in Google Scholar

[21] Sundaresan, G., Salhotra, K. R., Hari, P. K. (1998). Strength reduction in sewing threads during high speed sewing in industrial lockstitch machine: Part II: Effect of thread and fabric properties. International Journal of Clothing Science and Technology, 10(1), 64–79.10.1108/09556229810205303Search in Google Scholar

[22] Ajiki, I., Postle, R. (2003). Viscoelastic properties of threads before and after sewing. International Journal of Clothing Science and Technology, 15, 16–27.10.1108/09556220310461132Search in Google Scholar

[23] Geršak, J., Knez, B. (1993). Reduction in thread strength as a cause of loading in the sewing process. International Journal of Clothing Science and Technology, 3, 6–12.10.1108/eb002978Search in Google Scholar

[24] Midha, V. K., Kothari, V. K., Chatopadhyay, R., Mukhopadhyay, A. (2009). Effect of high-speed sewing on the tensile properties of sewing threads at different stages of sewing. International Journal of Clothing Science and Technology, 21, 217–238.10.1108/09556220910959981Search in Google Scholar

[25] Sundaresan, G., Hari, P. K., Salhotra, K. R. (1997). Strength reduction of sewing threads during high speed sewing in an industrial Lockstitch machine. Part I: Mechanism of thread strength reduction. International Journal of Clothing Science and Technology, 9, 334–345.10.1108/09556229710185460Search in Google Scholar

[26] Midha, V. K., Kothari, V. K., Chattopadhyay, R., Mukhopadhyay, A. (2010). Effect of workwear fabric characteristics on the changes in tensile properties of sewing thread after sewing. Journal of Engineered Fibers and Fabrics, 5, 31–38.10.1177/155892501000500104Search in Google Scholar

[27] Dobilaite, V., Juciene, M. (2006). The influence of mechanical properties of sewing threads on seam pucker. International Journal of Clothing Science and Technology, 18, 335–345.10.1108/09556220610685276Search in Google Scholar

[28] Zervent Ünal, B. (2011). The prediction of seam strength of denim fabrics with mathematical equations. The Journal of Textile Institute, 103, 744–751.10.1080/00405000.2011.603509Search in Google Scholar

[29] Fan, J., Leeuwner, W. (1998). The performance of sewing threads with respect to seam appearance. Journal of Textile Institute, 89 (1), 142–153.10.1080/00405009808658605Search in Google Scholar

[30] Khedher, F., Jaouachi, B. (2015). Waste factor evaluation using theoretical and experimental jean pants consumptions. Journal of Textile Institute, 106(4), 402–408.10.1080/00405000.2014.924225Search in Google Scholar

[31] Buzov, J. A., Modestova, T. A., Alymenkova, N. D. (1978). Fabric development in the garment industry. Moscow: Lyogkaya Industria, (p. 480).Search in Google Scholar

[32] Mukhopadhyay A. (2008). Relative performance of lockstitch and chain-stitch at the seat seam of military trouser. Journal of Engineered Fibers and Fabrics, 3(1), 21–24.10.1177/155892500800300103Search in Google Scholar

[33] Ukponmwan, J. O., Mukhopadhyay, A., Chatterjee K. N. (2000). Sewing threads. Textile Progress, 30, 79–80.10.1080/00405160008688888Search in Google Scholar

[34] Webster, J., Laing, R. M., Niven B. E. (1998a). Effects of repeated extension and recovery on selected physical properties of ISO-301 stitched seams, Part I: Load at maximum extension and at break. Textile Research Journal, 68, 854–86410.1177/004051759806801111Search in Google Scholar

[35] Webster J., Laing R. M., Enlow R. L. (1998b). Effects of repeated extension and recovery on selected physical properties of ISO-301 stitched seams, Part II: Theoretical model. Textile Research Journal, 68, 881–888.10.1177/004051759806801202Search in Google Scholar

[36] Rasheed, A., Ahmad, S., Mohsin, M., Ahmad, F., Afzal, A. (2014). Geometrical model to calculate the consumption of sewing thread for 301 Lockstitch. Journal of Textile Institute, 105(12), 1259–1264.10.1080/00405000.2014.886366Search in Google Scholar

[37] Rengasamy, R. S., Kothari, V. K., Alagirusamy, R., Modi, S. (2003). Studies on air-jet textured sewing threads. Indian Journal of Fibers & Textile Research, 28, 281–287.Search in Google Scholar

[38] Krishnan, S. A. N., Kumar, A. L. (2010). Design of sewing thread tension measuring device. Indian Journal of Fiber & Textile Research, 35, 65–67.Search in Google Scholar

[39] Gazzah, M., Khedher F., Jaouachi, B. (2017). Modelling the sewing thread consumption of 602 cover-stitch based on its geometrical shape. International Journal of Applied Research on Textile, 5(2).Search in Google Scholar

[40] Alagha, M. J., Amirbayat, J. & Porat, I. (1996). A Study of positive needle thread feed during Chain-stitch Sewing. Journal of Textile Institute, 87(2), 389–395.10.1080/00405009608659090Search in Google Scholar

[41] Lauriol, A. (1989). Initiation à la technologie des matériels dans les industries de l’habillement, Introduction to Materials technology In Clothing Industries, (151–154). Paris: Edition Vauclair.Search in Google Scholar

[42] American & Efird, ANECALC (2018), Thread Consumption, http://www.amefird.com/technical-tools/thread-consumption/, consulting date May 11, 1–4.Search in Google Scholar

[43] Chen, A., Zou, H. J., Du, R. (2001). Modeling of industrial sewing machines and the balancing of thread requirement and thread supply. Journal of Textile Institute, 92(3), 256–268.10.1080/00405000108659575Search in Google Scholar

© 2020 Brahem Mariem et al., published by Sciendo

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Fuzzy Logic Method for Predicting the Effect of Main Fabric Parameters Influencing Drape Phenomenon

- The Study on Effects of Walking on the Thermal Properties of Clothing and Subjective Comfort

- A Study on Improving Dyeability of Polyester Fabric Using Lipase Enzyme

- The Impact and Importance of Fabric Image Preprocessing for the New Method of Individual Inter-Thread Pores Detection

- Influence of Tensile Stress on Woven Compression Bandage Structure and Porosity

- Application of Silica Aerogel in Composites Protecting Against Thermal Radiation

- Multicriteria Decision-Making in Complex Quality Evaluation of Ladies Dress Material

- A Study of the Consumption of Sewing Threads for Women's Underwear: Bras and Panties

- Study of the Properties and Cells Growth on Antibacterial Electrospun Polycaprolactone/Cefuroxime Scaffolds

- How High-Loft Textile Thermal Insulation Properties Depend on Compressibility

- Lyocell Fabric Dyed with Natural Dye Extracted from Marigold Flower Using Metallic Salts

- Evolution of Physicochemical Structure of Waste Cotton Fiber (Hydrochar) During Hydrothermal Carbonation

- Analysis of the Thermal Insulation of Textiles Using Thermography and CFD Simulation Based on Micro-CT Models

- Circular Fashion – Consumers’ Attitudes in Cross-National Study: Poland and Canada

Articles in the same Issue

- Fuzzy Logic Method for Predicting the Effect of Main Fabric Parameters Influencing Drape Phenomenon

- The Study on Effects of Walking on the Thermal Properties of Clothing and Subjective Comfort

- A Study on Improving Dyeability of Polyester Fabric Using Lipase Enzyme

- The Impact and Importance of Fabric Image Preprocessing for the New Method of Individual Inter-Thread Pores Detection

- Influence of Tensile Stress on Woven Compression Bandage Structure and Porosity

- Application of Silica Aerogel in Composites Protecting Against Thermal Radiation

- Multicriteria Decision-Making in Complex Quality Evaluation of Ladies Dress Material

- A Study of the Consumption of Sewing Threads for Women's Underwear: Bras and Panties

- Study of the Properties and Cells Growth on Antibacterial Electrospun Polycaprolactone/Cefuroxime Scaffolds

- How High-Loft Textile Thermal Insulation Properties Depend on Compressibility

- Lyocell Fabric Dyed with Natural Dye Extracted from Marigold Flower Using Metallic Salts

- Evolution of Physicochemical Structure of Waste Cotton Fiber (Hydrochar) During Hydrothermal Carbonation

- Analysis of the Thermal Insulation of Textiles Using Thermography and CFD Simulation Based on Micro-CT Models

- Circular Fashion – Consumers’ Attitudes in Cross-National Study: Poland and Canada