Abstract

More than half of the >5000 approved mineral species are known from five or fewer localities and thus are rare. Mineralogical rarity arises from different circumstances, but all rare mineral species conform to one or more of four criteria: (1) P-T-X range: minerals that form only under highly restricted conditions in pressure-temperature-composition space; (2) Planetary constraints: minerals that incorporate essential elements that are rare or that form at extreme conditions that seldom occur in Earth’s near-surface environment; (3) Ephemeral phases: minerals that rapidly break down under ambient conditions; and (4) Collection biases: phases that are difficult to recognize because they lack crystal faces or are microscopic, or minerals that arise in lithological contexts that are difficult to access. Minerals that conform to criterion 1, 2, or 3 are inherently rare, whereas those matching criterion 4 may be much more common than represented by reported occurrences.

Rare minerals, though playing minimal roles in Earth’s bulk properties and dynamics, are nevertheless of significance for varied reasons. Uncommon minerals are key to understanding the diversity and disparity of Earth’s mineralogical environments, for example in the prediction of as yet undescribed minerals. Novel minerals often point to extreme compositional regimes that can arise in Earth’s shallow crust and they are thus critical to understanding Earth as a complex evolving system. Many rare minerals have unique crystal structures or reveal the crystal chemical plasticity of well-known structures, as dramatically illustrated by the minerals of boron. Uncommon minerals may have played essential roles in life’s origins; conversely, many rare minerals arise only as a consequence, whether direct or indirect, of biological processes. The distribution of rare minerals may thus be a robust biosignature, while these phases individually and collectively exemplify the co-evolution of the geosphere and biosphere. Finally, mineralogical rarities, as with novelty in other natural domains, are inherently fascinating.

Introduction

Of the more than 5000 species of minerals approved by the International Mineralogical Association (IMA), fewer than 100 common minerals account for more than 99% of Earth’s crustal volume, with a handful of feldspar mineral species comprising ~60 vol% (Rudnick 2003; Levin 2009). By contrast, most minerals are volumetrically insignificant and scarce. Rock-forming minerals understandably attract the greatest attention in the mineralogical literature, whereas the discovery of new minerals, which are usually extremely rare, no longer represents the central pursuit of many mineralogists. To what extent, therefore, are rare minerals important in understanding Earth?

This topic is informed by investigations of rare biological species, which have been examined in the context of ecosystem diversity and stability (Rabinowitz 1981; Rabinowitz et al. 1986; Gaston 1994, 2012; Dobson et al. 1995; Hull et al. 2015). Concerns about loss of diversity through extinction of rare species have provided a special focus (Lyons et al. 2005; Bracken and Low 2012). Recent results suggest that rare species may contribute unique ecological functions, including resistance to climate change, drought, or fire, and thus their loss may disproportionately affect the robustness of an ecosystem (Jain et al. 2013; Mouillot et al. 2013).

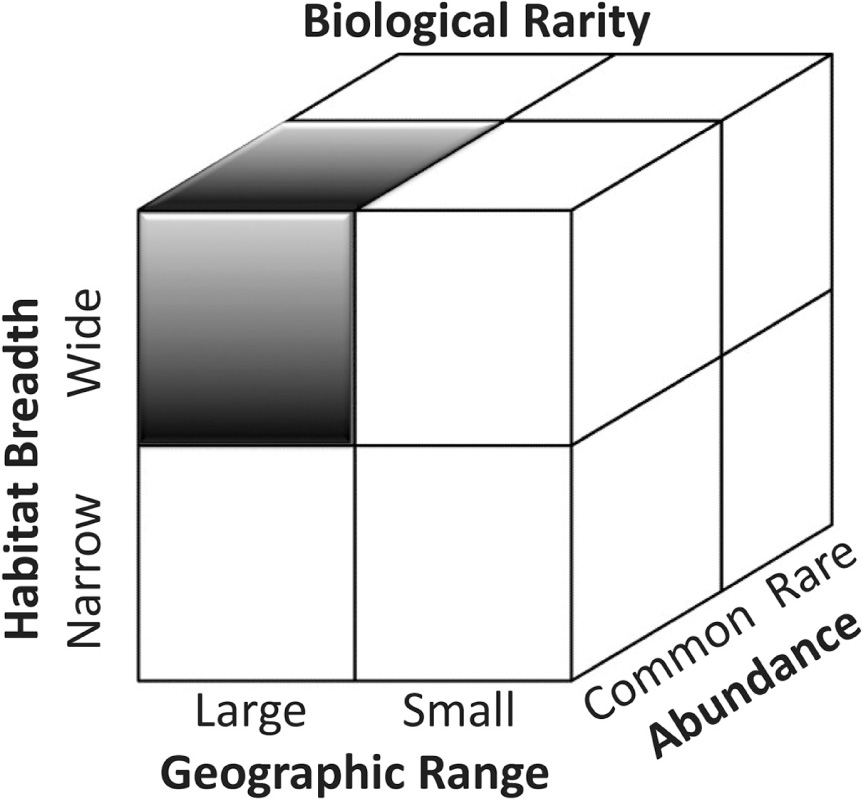

In a classic contribution, Deborah Rabinowitz (1981) proposed a taxonomy of biological rarity. She recognized that three factors—abundance, geographic range, and habitat restrictions—collectively contribute to rarity, as illustrated schematically in a dissected cube (Fig. 1). Subsequent studies have expanded on this foundation by examining factors that may influence sampling efficiency; for example, biases resulting from inadequate sampling time (Zhang et al. 2014) or the episodic apperarance of some ephemeral species (Petsch et al. 2015) may result in underestimates of rare species. The Rabinowitz scheme, which has been applied to a range of ecosystems (e.g., Arita et al. 1990; Ricklefs 2000; Hopkins et al. 2002; Richardson et al. 2012), can inform efforts to develop a taxomony of mineralogical rarity, as well.

Rabinowitz’s (1981) taxonomy of biological rarity: For a species to be common it must be abundant, distributed over a large geographic range, and able to live in a wide habitat (upper-left shaded octant). Other octants of this dissected cube delineate seven types of biological rarity. Note, however, that all three axes correspond to continuous parameters; therefore, divisions between wide vs. narrow habitat, common vs. rare abundance, and large vs. small geographic range are inherently arbitrary. This visualization, furthermore, does not include effects of sampling biases on perceptions of species rarity.

Recent studies in “mineral ecology,” which employ statistical methods to model the diversity and distribution of mineral species in Earth’s near-surface environments, depend strongly on the rarest of mineral species (Hazen et al. 2015a, 2015b; Hystad et al. 2015a2015b; Grew et al. 2016). It is therefore useful to consider the nature of rarity in mineralogy. In this essay we follow the lead of ecologists, cataloging the varied causes of rarity in the mineral kingdom and considering the scientific significance of these uncommon phases.

The Taxonomy of Rare Minerals

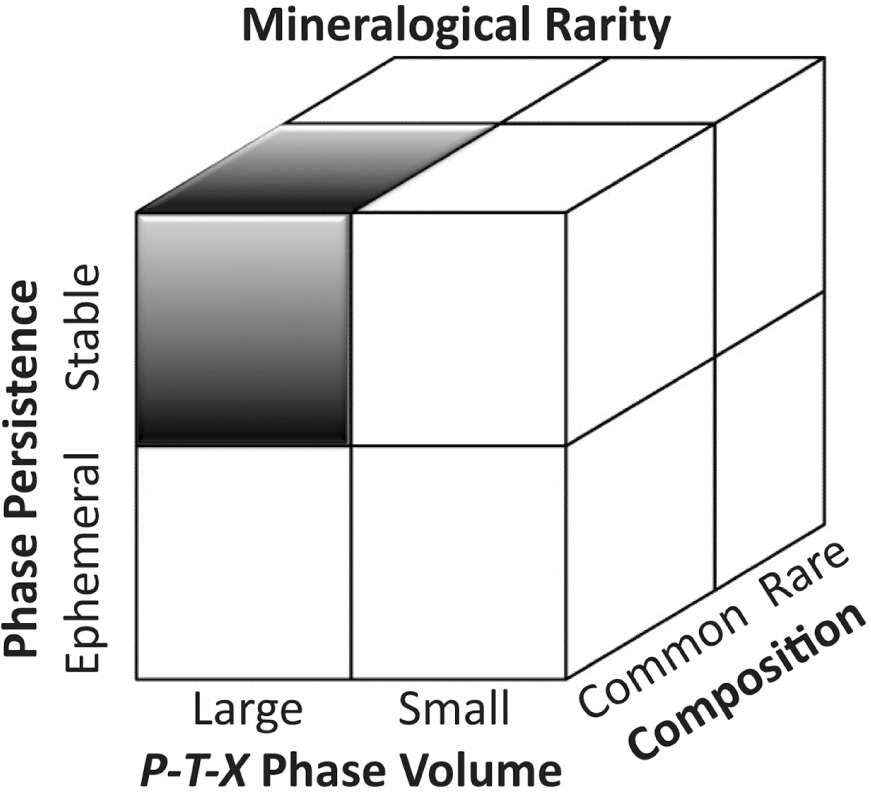

The word “rare” has been used in several mineralogical contexts. Here we define “rare” minerals as those recorded from five or fewer localities (defined by the number of mineral districts, as tabulated in the “Localities” section under each mineral species in the crowd-sourced database mindat.org)—a condition met by at least 2550 species, or more than half of all IMA approved minerals. Note that many of these minerals have a total known volume <1 cm3. This definition thus differs from the more colloquial use of the term “rare mineral,” which is often applied to gemstones. However, diamond, ruby, emerald, and other precious gems are found at numerous localities and are sold in commercial quantities, and thus are not rare in the sense used in this contribution. Uses of the word “rare” in the context of “rare earth elements” or “rare metals” are similarly misleading, as many thousands of tons of these commodities are produced annually. Note that alternative definitions of rarity, for example based on total crustal volume or mass of each mineral, might be proposed. However, a metric based on numbers of localities has the advantage of reproducibility through the open access data resource mindat.org (though it has been noted that locality lists in that database are neither complete nor fully referenced; Grew et al. 2016). We find that minerals known from 5 or fewer localities are rare for four different reasons. Every rare mineral conforms to one or more of these four distinct categories (Fig. 2).

Taxonomy of mineralogical rarity: Commoner species, represented by the upper left-hand shaded octant, must incorporate common chemical elements, have a large volume of phase stability in P-T-X space, and be stable. The other seven octants represent different types of rarer species. As with Figure 1, the three axes of this figure correspond to continous scales, for example from smaller to larger volume of stability in P-T-X space. Thus, any partitioning of mineral species into octants is inherently arbitrary. Note also that this visualization does not include the effects of sampling bias on perceptions of species rarity.

(1) Phase topology

Restricted phase stability in P-T-X space: The first category of mineral rarities arises because different phases have different ranges of stability in multi-dimensional pressure-temperature-composition (P-T-X) space (where composition typically refers to numerous coexisting elements). On the one hand, the commonest rock-forming minerals display wide ranges of P-T-X stability. By contrast, some rare phases, even though formed from relatively common elements, display extremely limited P-T-X stability fields and thus form only under idiosyncratic conditions (Table 1). For example, harmunite (CaFe2O4; Galuskina et al. 2014), though formed from abundant elements, has a narrow stability field (Phillips and Muan 1958), especially in the presence of silica (Levin et al. 1964, Fig. 656), and is reported from only two localities in mindat.org. Similarly, hatrurite (Ca3SiO5; Gross 1977) is listed on mindat.org from only one locality in spite of the abundance of many other calcium silicates. Hatrurite is rare because it only forms at temperatures above 1250 °C in a narrow range of compositions (Welch and Gutt 1959), notably in the absence of aluminum (Levin et al. 1964, Fig. 630). We also suggest that the extreme rarity of several zeolites (recorded at only one or two localities in mindat.org; Table 1), is also a consequence of their presumed highly restricted phase stability in P-T-X space. Zeolites display modular framework crystal structures with interconnected 4-, 6-, and 8-member tetrahedral rings that form a rich variety of channels and cavities, so small changes in the ratios of cations, as well as in the P-T conditions of formation, can lead to many new phases (Bish and Ming 2001; Bellussi et al. 2013; www.iza-structure.org/databases/).

Selected rare minerals (defined as occurring at five or fewer localities on mindat.org), chemical formulas (rruff.info/ima), causes of rarity (see text for explanations), and remarks (for additional notes on mineral localities and paragenesis see Anthony et al. 1990)

| Mineral | Formula | Limited P-T-X | Rare elements | Ephemeral minerals | Biased sampling | Remarks |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Harmunite | CaFe2O4 | X | Narrow stability in CaO-Fe2O3 system | |||

| hatrurite | Ca3SiO5 | X | Narrow stability in CaO-SiO2 system | |||

| boggsite | Na3Ca8(Si77Al19)O192·70H2O | X | Rare zeolite mineral | |||

| faujasite-Mg | (Mg,Na,K,Ca)2(Si,Al)12O24·15H2O | X | Rare zeolite mineral | |||

| gottardiite | Na3Mg3Ca5Al19Si117O272·93H2O | X | Rare zeolite mineral | |||

| mutinaite | Na3Ca4Al11Si85O192·60H2O | X | Rare zeolite mineral | |||

| parthéite | Ca2(Si4Al4)O15(OH)2·4H2O | X | Rare zeolite mineral | |||

| paulingite-Ca | (Ca,K,Na,Ba)10(Si,Al)42O84·34H2O | X | Rare zeolite mineral | |||

| perlialite | K9NaCa(Si24Al12)O72·15H2O | X | Rare zeolite mineral | |||

| bernalite | Fe(OH)3 | X | Forms only at low pH | |||

| ammonioalunite | NH4Al3(SO4)2(OH)6 | X | Forms only at low pH | |||

| meta-aluminate | Al2SO4(OH)4·5H2O | X | Forms only at low pH | |||

| schwertmannite | X | Forms only at low pH | ||||

| hazenite | KNaMg2(PO4)2·14H2O | X | Hypersaline, high pH | |||

| balyakinite | Cu2+Te4+O3 | X | Te ~ 0.005 ppm crustal abundance | |||

| carlfriesite | CaTe6+ | X | Te ~ 0.005 ppm crustal abundance | |||

| mroseite | CaTe4+O2(CO3) | X | Te ~ 0.005 ppm crustal abundance | |||

| clearcreekite | Hg | X | Hg ~ 0.05 ppm crustal abundance | |||

| hanawaltite | Hg61+Hg2+O3Cl2 | X | Hg ~ 0.05 ppm crustal abundance | |||

| donharrisite | Ni8Hg3S9 | X | Hg ~ 0.05 ppm crustal abundance | |||

| birchite | Cd2Cu2(PO4)2SO4·5H2O | X | Cd ~ 0.09 ppm crustal abundance | |||

| drobecite | CdSO4·4H2O | X | Cd ~ 0.09 ppm crustal abundance | |||

| lazaridisite | (CdSO4)3·8H2O | X | Cd ~ 0.09 ppm crustal abundance | |||

| swedenborgite | NaBe4Sb5+O7 | X | Rare combination of Be + Sb | |||

| alburnite | Ag8GeTe2S4 | X | Rare combination of Ge + Te | |||

| ichnusaite | Th(MoO4)2·3H2O | X | Rare combination of Th + Mo | |||

| alsakharovite-Zn | NaSrKZn(Ti,Nb)4(Si4O12)2(O,OH)4·7H2O | X | 9 coexisting elements | |||

| carbokentbrooksite | (Na,□)12(Na,Ce)3Ca6Mn3Zr3NbSi25O73(OH)3(CO3)·H2O | X | 10 coexisting elements | |||

| johnsenite-(Ce) | [Na12Ce3Ca6Mn3Zr3WSi25O73(CO3)(OH)2 | X | 10 coexisting elements | |||

| senaite | Pb(Mn,Y,U)(Fe,Zn)2(Ti,Fe,Cr,V)18(O,OH)38 | X | 11 coexisting elements | |||

| acetamide | CH3CONH2 | X | Volatilizes on exposure to air and sunlight | |||

| hydrohalite | NaCl·2H2O | X | Melts at –0.1 °C | |||

| meridianiite | MgSO4·11H2O | X | Melts at 2°C | |||

| chalcocyanite | CuSO4 | X | Hygroscopic | |||

| ekaterinite | Ca2B4O7Cl2·2H2O | X | Hygroscopic | |||

| kamchatkite | KCu3O(SO4)2Cl | X | Hygroscopic | |||

| nitromagnesite | Mg(NO3)2·6H2O | X | Hygroscopic | |||

| rorisite | CaFCl | X | Hygroscopic | |||

| scacchite | MnCl2 | X | Hygroscopic | |||

| sinjarite | CaCl2·2H2O | X | Hygroscopic | |||

| sveite | KAl7(NO3)4(OH)16Cl2·8H2O | X | Hygroscopic | |||

| tolbachite | CuCl2 | X | Hygroscopic | |||

| aplowite | CoSO4·4H2O | X | Dehydrates | |||

| boothite | CuSO4·7H2O | X | Dehydrates | |||

| chvaleticeite | MnSO4·6H2O | X | Dehydrates | |||

| hohmannite | X | Dehydrates | ||||

| hydrodresserite | BaAl2(CO3)2(OH)4·3H2O | X | Dehydrates | |||

| hydroscarbroite | Al14(CO3)3(OH)36·nH2O | X | Dehydrates | |||

| lonecreekite | NH4Fe3+(SO4)2·12H2O | X | Dehydrates | |||

| marthozite | Cu2+(UO2)3(Se4+O3)2O2·8H2O | X | Dehydrates | |||

| zaherite | Al12(SO4)5(OH)26·20H2O | X | Dehydrates | |||

| avogadrite | KBF4 | X | Ephemeral fumarole mineral | |||

| carobbite | KF | X | Ephemeral fumarole mineral | |||

| chloraluminite | AlCl3·6H2O | X | Ephemeral fumarole mineral | |||

| cyanochroite | K2Cu(SO4)2·6H2O | X | Ephemeral fumarole mineral | |||

| ferruccite | NaBF4 | X | Ephemeral fumarole mineral | |||

| melanothallite | Cu2OCl2 | X | Ephemeral fumarole mineral | |||

| palmierite | K2Pb(SO4)2 | X | Ephemeral fumarole mineral | |||

| piypite | K4Cu4O2(SO4)4·(Na,Cu)Cl | X | Ephemeral fumarole mineral | |||

| ponomarevite | K4Cu4OCl10 | X | Ephemeral fumarole mineral | |||

| aubertite | Cu2+Al(SO4)2Cl·14H2O | X | Water-soluble supergene mineral | |||

| bayleyite | Mg2(UO2)(CO3)3·18H2O | X | Water-soluble supergene mineral | |||

| caracolite | Na2Pb2(SO4)3Cl | X | Water-soluble supergene mineral | |||

| fedotovite | K2Cu3O(SO4)3 | X | Water-soluble supergene mineral | |||

| grimselite | K3Na(UO2)(CO3)3·H2O | X | Water-soluble supergene mineral | |||

| pseudograndreefite | Pb6(SO4)F10 | X | Water-soluble supergene mineral | |||

| redingtonite | Fe2+Cr2(SO4)4·22H2O | X | Water-soluble supergene mineral | |||

| wheatleyite | Na2Cu(C2O4)2·2H2O | X | Water-soluble supergene mineral | |||

| wupatkiite | CoAl2(SO4)4·22H2O | X | X | Water-soluble supergene mineral | ||

| gregoryite | Na2CO3 | X | Water-soluble carbonatite lavas | |||

| natroxalate | Na2C2O4 | X | Water-soluble alkaline massif mineral | |||

| koktaite | (NH4)2Ca(SO4)2·H2O | X | Water-soluble coal mine dump mineral | |||

| lecontite | (NH4)Na(SO4)·2H2O | X | Water-soluble mineral from bat guano | |||

| minasragrite | V4+O(SO4)·5H2O | X | X | Water-soluble mineral in fossilized wood | ||

| ransomite | Cu | X | Water-soluble mineral from mine fires | |||

| ye’elimite | Ca4Al6O12(SO4) | X | Water-soluble high-T metamorphic mineral | |||

| chlorocalcite | KCaCl3 | X | Deliquescent | |||

| erythrosiderite | K2Fe3+Cl5·H2O | X | Deliquescent | |||

| gwihabaite | (NH4)NO3 | X | Deliquescent | |||

| molysite | FeCl3 | X | Deliquescent | |||

| mikasaite | Fe23+(SO4)3 | X | Deliquescent | |||

| tachyhydrite | CaMg2Cl6·12H2O | X | Deliquescent | |||

| edoylerite | X | Photo-sensitive | ||||

| metasideronatrite | Na2Fe3+(SO4)2(OH)·H2O | X | Photo-sensitive | |||

| sideronatrite | Na2Fe3+(SO4)2(OH)·3H2O | X | Photo-sensitive | |||

| agaite | Pb3Cu2+Te6+O5(OH)2(CO3) | X | X | Microscopic | ||

| andchristyite | PbCu2+Te6+O5(H2O) | X | X | Microscopic | ||

| bairdite | Pb2 | X | X | Microscopic | ||

| chromschieffelinite | Pb10 | X | X | Microscopic | ||

| houseleyite | Pb6CuTe4O18(OH)2 | X | X | Microscopic | ||

| markcooperite | Pb2(UO2)TeO6 | X | X | Microscopic | ||

| ottoite | Pb2TeO5 | X | X | Microscopic | ||

| telluroperite | Pb3Te4+O4Cl2 | X | X | Microscopic | ||

| hutcheonite | Ca3Ti2(SiAl2)O12 | X | TEM-identified nanomineral | |||

| allendeite | Sc4Zr3O12 | X | X | TEM-identified nanomineral | ||

| fingerite | Cu11O2(VO4)6 | X | X | X | X | Ephemeral fumarole Cu +V mineral |

| mcbirneyite | Cu3(VO4)2 | X | X | X | X | Ephemeral fumarole Cu +V mineral |

| stoiberite | Cu5O2(VO4)2 | X | X | X | X | Ephemeral fumarole Cu +V mineral |

| ziesite | Cu2 | X | X | X | X | Ephemeral fumarole Cu +V mineral |

Special cases of restricted mineral stabilities arise from extremes of eH and pH. For example, several native elements, including nickel, silicon, titanium, and zinc, seldom occur in Earth’s crust owing to the requirement of extremely reducing conditions. The exceptionally acidic conditions of some hot springs and weathered sulfide environments (with reported pH as low as –3.6; Nordstrom et al. 2000), also lead to rare minerals (Table 1), such as bernalite ammonioalunite, and schwertmanite [e.g., Jönsson et al. 2006; for characteristics and citations of rare minerals see Anthony et al. (1990) and references therein]. Similarly, extremely alkaline hypersaline Mono Lake, California, with pH ~10 hosts the only known occurrence of the biologically mediated mineral hazenite.

The great contrasts among stability ranges of minerals point to as yet unexplored aspects of the topological distribution of phases in P-T-X space. IMA approved minerals incorporate 72 different chemical elements that are reported as essential in one or more minerals. Furthermore, the numbers of species containing each of these elements is, to a significant degree, correlated with the crustal abundance of the element (Christy 2015; Hazen et al. 2015a). This correlation between crustal abundance and mineral diversity suggests that there exists an average “phase volume” in 74-dimensional P-T-X space, as well as a statistical distribution of smaller to larger phase volumes.

Two caveats are required. First, a continuum exists between “small” and “large” phase volumes; therefore, any division of minerals into one or the other of these two categories (as implied by the dissected cube in Fig. 2) is inherently arbitrary. Second, while it is obvious that some minerals have a greater stability range than others, no metric yet exists to quantify “volume of P-T-X phase space.” Such a metric is essential if quantitative statistical analysis of the distribution of phases in phase space is to be attempted.

In spite of these issues, it seems likely that the number of different mineral species to be found on a terrestrial planet or moon will be a direct consequence of phase topology in combination with the extent of mineral evolution on the body. Mineral diversity, including the presence of rare minerals, will reflect the total P-T-X range available on that planetary body, coupled with the statistical distribution of phase topologies. Investigations of the relationship between mineral diversity and phase space may thus prove to be of interest, both in characterizing the variety of rocky planets and in developing a deeper understanding of phase topology.

(2) Planetary constraints: Incorporation of rare elements or formation atP-T conditions rarely encountered in near-surface environments

A second category of mineral rarity arises from the improbable occurrence of certain P-T-X chemical microenvironments near Earth’s surface (Table 1). These rare minerals often have large stability ranges in P-T-X space and thus do not conform to category 1; rarity arises because those stability conditions are rarely sampled in Earth’s crust.

Several examples include minerals of Earth’s rarest chemical elements, such as tellurium with a crustal abundance of 0.005 ppm, mercury with a crustal abundance of 0.05 ppm, and cadmium with an upper crustal abundance of 0.09 ppm (Table 1; Wedepohl 1995; Rudnick and Gao 2005). Many additional rare minerals, as well as thousands of potential minerals that are known as synthetic phases but have not yet been discovered naturally, require the incorporation of two or more elements that seldom occur together and thus are far rarer than would be expected from their crustal abundances. Examples include such unusual pairings as Be-Sb in swedenborgite, Ge-Te in alburnite, and Mo-Th in ichnusaite (Table 1). A few minerals incorporate nine or more chemical elements in combinations that point to rare, if not unique, geochemical environments (Table 1).

Finally, several minerals such as diamond, coesite, and ringwoodite may form commonly at depth, where they crystallize at extremes of pressure and temperature, but those P-T regimes are less commonly sampled at Earth’s surface—an effect that is analogous to compositional regimes rarely found in Earth’s crust. As an extreme example is the perovskite form of MgSiO3, bridgmanite, which has only been described as a microscopic shock phase from a single meteorite, yet it is likely that bridgmanite is the dominant lower mantle mineral, and thus is Earth’s most important mineral in terms of volume (Tschauner et al. 2014).

Unlike the first category of rarities that arise from limited stability in P-T-X space, many of the scarce minerals in category 2 have extensive P-T-X stability ranges. Rarity emerges from the nature of cosmochemistry and the idiosyncrasies of unusual geochemical environments on Earth, as opposed to restrictions imposed by phase topology. Note that, as with the ill-defined parameter “volume of P-T-X phase space,” compositional rarity is a continuous function; some elements and their combinations are less common than others. Also, as with phase space, there exists no obvious metric of rarity for combinations of elements. It might be tempting to employ crustal abundances of elements to quantify the compositional axis (e.g., Wedepohl 1995; Rudnick and Gao 2005), but the production of rare minerals is equally dependent on the extent to which an element can be locally concentrated by physical, chemical, or biological processes—mechanisms that do not directly correlate with crustal abundances. For example, hafnium with a crustal abundance of 5.3 ppm is an essential element in only one mineral species, in contrast to uranium (2.7 ppm; >250 species), because Hf mimics Zr and thus is not easily concentrated into its own phases. Thus, no simple measure yet exists for compositional rarity, which must for the present remain a qualitative characteristic of minerals.

(3) Ephemeral minerals: Phases that do not persist under ambient conditions

A third category of mineral rarities includes numerous phases that form under varied non-ambient conditions but degrade quickly at ambient conditions. Some of these minerals may form frequently in Earth’s near-surface environment, but are nevertheless rare primarily owing to their relatively brief lifetimes.

Minerals can be ephemeral for several reasons. Phases that melt or evaporate at ambient conditions are rarely represented in mineral collections. For example, methane hydrate (nominally CH4·5.75H2O) is well known as an abundant crystalline phase from continental shelf and Arctic drill sites (Hyndman and Davis 1992; Kvenvolden 1995), but it evaporates quickly at room pressure, or burns if set afire, and has not yet been characterized as a mineral. Similarly, the crystalline form of CO2, which is only stable below –78.5 °C, is not yet known as a mineral on Earth, though it could form under Earth’s most extreme cold conditions of –94.7 °C (recorded from East Antarctica by NASA in August 2010) and it has been documented by remote sensing on Mars (Byrne and Ingersoll 2003). By contrast, phases such as ethanol (C2H5OH; freezing temperature –114 °C) and acetylene (C2H2; –80.8 °C) that have been proposed as plausible minerals on Titan (surface temperature –179 °C) are unlikely phases on Earth. Other phases that melt or evaporate under most surface conditions include acetamide, hydrohalite, and meridianiite (Table 1).

Hygroscopic phases that rapidly hydrate (Table 1) may also be more common than is reflected in mineral collections. Magnesium sulfate (MgSO4), though well known as a synthetic compound, has not yet been found in nature. By contrast, 11 hydrated magnesium sulfate minerals have been described, including such common phases as epsomite (MgSO4·7H2O) and kieserite (MgSO4·H2O). Lime (CaO), similarly, is recorded from fewer than 10 localities, in contrast to the common hydrated daughter mineral, portlandite [Ca(OH)2]. By contrast, several uncommon minerals are unstable in part because they readily dehydrate upon exposure to air (Table 1).

Water-soluble minerals may also be under-reported, and thus appear to be rare. More than 100 evaporite mineral species, including halides, borates, and nitrates, can persist in dry evaporite environments for many years, only to be washed away during rare rain events. Similarly, water-soluble phases that form in volcanic fumeroles may form intermittently and then dissolve with each subsequent rainstorm. Several examples of these scarce soluble fumarolic phases incorporate an alkali and/or a halogen element (Table 1). Other water-soluble phases that may be under-reported occur in a wide variety of environments, including oxidized zones of ore bodies, carbonatite lavas, alkaline massifs, coal mine waste dumps, bat guano, fossilized wood, mine fires, and high-temperature metamorphic assemblages (Table 1). Among the least stable minerals are rare species that are deliquescent—both adsorbing moisture from the air and then dissolving in it. Finally, a few rare minerals, including edoylerite, metasideronatrite, and sideronatrite, are photosensitive and gradually decompose when exposed to sunlight.

It should be noted that the description of a mineral as “ephemeral,” as with other parameters of rarity, is a relative term. The phases enumerated in Table 1 (and many more) may degrade in less than a day. However, many unstable or metastable minerals transform more slowly. Many Hg minerals, for example, are known to evaporate gradually; thus, more than half of IMA approved mercury minerals are known only from deposits younger than 50 million years (Hazen et al. 2012), in contrast to the age distributions of minerals of many other elements (Hazen et al. 2014). Similarly, borates, nitrates, and halides that are stable for thousands of years in evaporite deposits may, nevertheless, be ephemeral over time scales of millions of years. Grew et al. (2016) have found that more than 100 species of boron minerals (of 291 approved species) are known only from the Phanerozoic Eon. Thus, gradual loss of some Hg and B minerals may contribute to their relative rarity.

(4) Negative sampling biases

A significant number of rare minerals may be poorly documented because they are either difficult to recognize based on their appearance, occur only at the micro- or nano-scale, or are found in under-sampled lithological contexts. Thus, some minerals are rare because they are exceptionally problematic to recognize in hand specimen; notably a pale color and lack of distinctive crystal morphology leads to difficulty in identification. For example, Hazen et al. (2015b) noted that more than half of known sodium minerals are poorly crystalline and white or gray in color. Rare sodium minerals, thus, may be significantly under-reported, while a significant fraction of sodium minerals remains undiscovered.

At the extremes of scale, several new minerals have been discovered only as micro- or nano-phases. These microscopic minerals, and many others yet to be discovered, are likely to be more common than implied by numbers of known localities. For example, several rare tellurium minerals known only from Otto Mountain, California, have been discovered through intensive application of microscopy and electron microprobe analysis of specimens from that deposit (Housely et al. 2011; Table 1). These minerals are intrinsically uncommon, but their rarity may be exaggerated because of the technical difficulties in finding and characterizing such microscopic phases.

The application of transmission electron microscopy to the discovery of new minerals, thus far applied primarily to meteorite phases, has led to descriptions of species such as hutcheonite and allendeite, which may remain rare by virtue of the difficulty and expense of the analytical technique (Table 1; Ma and Krot 2014; Ma et al. 2014). These extraterrestrial phases, and many others awaiting discovery on Earth, are certainly volumetrically insignificant, but they may occur much more commonly than is implied by a list of their known localities. We suspect that numerous other nano-minerals await discovery, and all will be rare by virtue of their miniscule grain size.

Some minerals may seem to be rare because of their remote and/or dangerous environmental contexts. Minerals from Antarctica, deep-ocean minerals (notably those formed at sub-surface volcanic vents), and phases that grow in aqueous environments at extremes of temperature or pH, crustal environments at elevated pressures, or in volcanic fumaroles, are all from mineral-forming environments to which access is challenging and thus may be under-represented in mineral collections.

It should be noted that positive sampling biases also likely affect our perceptions of mineral rarity. Intensive searches for deposits of rare elements such as Au, Cd, Co, Ge, U, and the rare earths have undoubtedly led to the discovery of species containing these elements at more localities than comparably rare minerals of less economic interest (Hazen et al. 2015b).

Rarity in mineralogy vs. biology

The preceding taxonomy of mineralogical rarity differs in significant respects from that for biological species (compare Figs. 1 and 2). Biological species are rare if they have few individuals, are found in a narrow geographic range, and/or have a restricted habitat. These traits are not exactly analogous to the potential for formation of rare minerals, which must possess small P-T-X phase volume (category 1 above), incorporate rare combinations of elements (category 2), and/or are ephemeral (category 3). Both biological and mineralogical rarity depend to a significant degree on the nature of the environmental niches in which the species are found but, unlike evolving biological species, minerals owe their rarity to circumstances of cosmochemistry, geochemistry, and/or phase equilibria.

An additional important difference between biological and mineralogical rarity is that biological species, once extinct, will not re-emerge naturally. Rare minerals, on the other hand, may disappear from Earth for a time, only to reappear when the necessary physical and chemical conditions arise again.

Even more fundamental a difference between biological and mineralogical species lies in what John N. Thompson (2013) has called “relentless evolution.” In contrast to mineral species, biological species that do not become extinct nevertheless are constantly evolving, in some instances not so gradually, into new forms. Minerals do not evolve in this way, though an intriguing and as yet little explored aspect of mineralogy is how trace and minor elements and isotopes in common mineral species have varied through Earth history in response to changing near-surface conditions (Hazen et al. 2011). Thus, such diverse mineral groups as feldspars, amphiboles, clays, tourmalines, and oxide spinels from Earth’s Archean Eon may differ in subtle and systematic ways from those formed more recently.

Important similarities in the perceptions of biological and mineralogical rarity are the influences of sampling bias. In both domains, species that are difficult to discover by virtue of their bland appearances, small sizes, or inaccessible environments (category 4) may be much more common than are represented by reported occurrences (Zhang et al. 2014; Hazen et al. 2015b; Petsch et al. 2015).

Like biological rarities, rare minerals often display two or more of the categories of rarity, as illustrated by the various octants in Figure 2. For example, several rare copper vanadate minerals, including fingerite, mcbirneyite, stoiberite, and ziesite (Table 1), are known from the summit crater fumeroles of Izalco volcano, El Salvador, and at most one other locality (Hughes and Hadidiacos 1985). These minerals: (category 1) have extremely restricted stabilities in P-T-X space (Brisi and Molinari 1958); (category 2) they feature two elements, Cu and V, that are seldom found in combination; (category 3) they may be unstable under prolonged exposure to the atmosphere; and (category 4) they form in an extremely dangerous volcanic environment.

Implications: Why Rare Minerals are Important

Even though most rare minerals play minimal roles in Earth’s bulk properties and dynamics, they are nevertheless important for varied reasons. Hystad et al. (2015a) found that frequency distributions of minerals conform to large number of rare events (LNRE) models, which depend primarily on numbers of mineral species from 10 or fewer localities. Thus, uncommon minerals are key to understanding the diversity and disparity of Earth’s mineralogical environments, and they are essential in calculating accumulation curves that lead to the prediction of as yet undescribed minerals (Hazen et al. 2015a, 2015b; Hystad et al. 2015a; Grew et al. 2016).

Novel minerals are also significant because they often point to extreme compositional regimes that can arise in Earth’s shallow crust. In this respect, Earth differs from other terrestrial planets and moons in our Solar System, which appear to be mineralogically far simpler than Earth. Thus rare minerals are valuable in understanding Earth as a complex evolving system in which pervasive fluid-rock interactions and biological processes lead to new mineral-forming niches (Hystad et al. 2015b). Indeed, LNRE distributions of minerals may constitute a sensitive biosignature for planets and moons.

An additional important motivation for the continued discovery and study of rare minerals is the likelihood of finding novel crystal structures, as well as new compositional regimes for known structure types. Grew et al. (2016) demonstrated that the 87 minerals of boron found at only 1 locality and with known crystal structures have a significantly higher average and maximum structural complexity (average complexity 420 bits per unit cell; maximum complexity 2321 bits; Krivovichev 2012) than the 88 minerals with known structures from 2, 3, 4, or 5 localities (average complexity 336 bits per unit cell; maximum complexity 1656 bits). These rare minerals, in turn, have significantly greater average structural complexity than the 81 more common boron minerals with known structures from 6 or more localities (average complexity 267 bits per unit cell). Rare minerals, furthermore, have a higher percentage of unique crystal structures compared to rock-forming minerals. More than half of boron minerals known from only one locality (53%) are structurally unique, compared to 42% unique structures for B species from 2 to 5 localities and 32% from more common B minerals known from more than 5 localities. The study of rare minerals thus leads to a disproportionately large number of novel crystal structures and, consequently, is central to advances in crystal chemistry. In addition, rare minerals are critical in establishing the compositional plasticity of more common structures. For example, of 24 species of the tourmaline group (the most diverse B structure type), 15 species are known from 5 or fewer localities and 11 are unique. Without rare species our understanding of the remarkable compositional plasticity of the tourmaline structure would be significantly limited.

Another possible contribution of rare minerals, though as yet speculative, relates to the origins of life. While most origins-of-life scenarios incorporate common minerals such as feldspars or clays (e.g., Cleaves et al. 2012), several uncommon minerals, including species of sulfides, borates, and molybdates (Wächtershäuser 1988; Ricardo et al. 2004; Kim et al. 2011; Hazen 2006; Cleaves et al. 2012), have also been invoked. Conversely, many rare minerals arise only as a consequence, whether directly (e.g., through biomineralization or bioweathering) or indirectly (e.g., atmospheric oxidation), of biological processes (Hazen et al. 2008, 2013). More than two-thirds of known mineral species, including the great majority of rare species, have thus been attributed to biological changes in Earth’s near-surface environment. Again, we suggest that the distribution of rare minerals may not only arise from biological activity, but it may also be a robust biosignature for life on other terrestrial worlds.

Finally, mineralogical rarities, as with novelties in biology, astronomy, and other natural systems, are inherently fascinating. We live on a planet with remarkable mineralogical diversity, featuring countless variations of color and form, richly varied geochemical niches, and captivating compositional and structural complexities. Rare species, comprising as they do more than half of the diversity of Earth’s rich mineral kingdom, thus provide the clearest and most compelling window into the complexities of the evolving mineralogical realm.

Acknowledgments

This publication is a contribution to the Deep Carbon Observatory. We are grateful to Edward Grew, George Harlow, and Woollcott K. Smith for detailed and perceptive reviews that greatly improved this manuscript. We also thank Ernst Burke, Robert Downs, Daniel Hummer, and Marcus Origlieri for helpful advice and constructive comments. This work was supported by the Deep Carbon Observatory, the Alfred P. Sloan Foundation, the W.M. Keck Foundation, a private foundation, and the Carnegie Institution for Science.

References Cited

Anthony, J.W., Bideaux, R.A., Bladh, K.W., and Nichols, M.C. (1990) Handbook of Mineralogy. Mineral Data Publishing, Arizona, Tucson.Search in Google Scholar

Arita, H.T., Robinson, J.G., and Redford, K.H. (1990) Rarity in neotropical forest mammals and its ecological correlates. Conservation Biology, 4, 181–192.10.1111/j.1523-1739.1990.tb00107.xSearch in Google Scholar

Bellussi, G., Carati, A., Rizzo, C., and Millini, R. (2013) New trends in the synthesis of crystalline microporous materials. Catalysis Science and Technology, 3, 833–857.10.1039/C2CY20510FSearch in Google Scholar

Bish, D.L., and Ming, D.W. [Eds.] (2001) Natural Zeolites: Occurrence, Properties, Applications, vol. 45. Reviews in Mineralogy and Geochemistry, Mineralogical Society of America, Chantilly, Virginia.Search in Google Scholar

Bracken, M.E.S., and Low, N.H.N. (2012) Realistic losses of rare species disproportionately impact higher trophic levels. Ecology Letters, 15, 461–467.10.1111/j.1461-0248.2012.01758.xSearch in Google Scholar PubMed

Brisi, C., and Molinari, A. (1958) Il sistema osido ramicoanidride vanadica. Annali di Chimica Roma, 48, 263–269.Search in Google Scholar

Byrne, S., and Ingersoll, A.P. (2003) A sublimation model for Martian polar ice features. Science, 299, 1051–1053.10.1126/science.1080148Search in Google Scholar PubMed

Christy, A.G. (2015) Causes of anomalous mineralogical diversity in the Periodic Table. Mineralogical Magazine, 79, 33–49.10.1180/minmag.2015.079.1.04Search in Google Scholar

Cleaves, H.J. II, Scott, A.M., Hill, F.C., Leszczynski, J., Sahai, N., and Hazen, R.M. (2012) Mineral-organic interfacial processes: potential roles in the origins of life. Chemical Society Reviews, 41, 5502–5525, DOI: 10.1039/c2cs35112a.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

Dobson, F.S., Yu, J., and Smith, A.T. (1995) The importance of evaluating rarity. Conservation Biology, 9, 1648–1651.10.1046/j.1523-1739.1995.09061648.xSearch in Google Scholar

Galuskina, I.O., Vapnik, Y., Lazic, B., Armbruster, T., Murashko, M., and Galuskin, E.V. (2014) Harmunite CaFe2O4: A new mineral from the Jabel Harmun, West Bank, Palestinian Autonomy, Israel. American Mineralogist, 99, 965–975.10.2138/am.2014.4563Search in Google Scholar

Gaston, K.J. (1994) Rarity. Chapman & Hall, London.10.1007/978-94-011-0701-3Search in Google Scholar

Gaston, K.J. (2012) Ecology: the importance of being rare. Nature, 487, 46–47.10.1038/487046aSearch in Google Scholar PubMed

Grew, E.S., Krivovichev, S.V., Hazen, R.M., and Hystad, G. (2016) Evolution of structural complexity in boron minerals. Canadian Mineralogist, in press.10.3749/canmin.1500072Search in Google Scholar

Gross, S. (1977) The mineralogy of the Hatrurim formation, Israel. Geological Survey of Israel Bulletin, 70, 1–80.Search in Google Scholar

Hazen, R.M. (2006) Mineral surfaces and the prebiotic selection and organization of biomolecules (Presidential Address to the Mineralogical Society of America). American Mineralogist, 91, 1715–1729.10.2138/am.2006.2289Search in Google Scholar

Hazen, R.M., Papineau, D., Bleeker, W., Downs, R.T., Ferry, J., McCoy, T., Sverjensky, D.A., and Yang, H. (2008) Mineral evolution. American Mineralogist, 93, 1693–1720.10.2138/am.2008.2955Search in Google Scholar

Hazen, R.M., Bekker, A., Bish, D.L., Bleeker, W., Downs, R.T., Farquhar, J., Ferry, J.M., Grew, E.S., Knoll, A.H., Papineau, D., and others. (2011) Needs and opportunities in mineral evolution research. American Mineralogist, 96, 953–963.10.2138/am.2011.3725Search in Google Scholar

Hazen, R.M., Golden, J., Downs, R.T., Hysted, G., Grew, E.S., Azzolini, D., and Sverjensky, D.A. (2012) Mercury (Hg) mineral evolution: A mineralogical record of supercontinent assembly, changing ocean geochemistry, and the emerging terrestrial biosphere. American Mineralogist, 97, 1013–1042.10.2138/am.2012.3922Search in Google Scholar

Hazen, R.M., Jones, A., Kah, L., and Sverjensky, D.A. (2013) Carbon mineral evolution. Reviews in Mineralogy and Geochemistry, 75, 79–107.10.1515/9781501508318-006Search in Google Scholar

Hazen, R.M., Liu, X.-M., Downs, R.T., Golden, J., Pires, A.J., Grew, E.S., Hystad, G., Estrada, C., and Sverjensky, D.A. (2014) Mineral evolution: Episodic metallogenesis, the supercontinent cycle, and the co-evolving geosphere and biosphere. Economic Geology Special Publication, 18, 1–15.Search in Google Scholar

Hazen, R.M., Grew, E.S, Downs, R.T., Golden, J., and Hystad, G. (2015a) Mineral ecology: chance and necessity in the mineral diversity of terrestrial planets. Canadian Mineralogist, 53, 295–323, DOI: 10.3749/canmin.1400086.Search in Google Scholar

Hazen, R.M., Hystad, G., Downs, R.T., Golden, J., Pires, A., and Grew, E.S. (2015b) Earth’s “missing” minerals. American Mineralogist, 100, 2344–2347, DOI: 10.2138/am-2015-5417.Search in Google Scholar

Hopkins, G.W., Thacker, J.I., Dixon, A.F.G., Waring, P., and Telfer, M.G. (2002) Identifying rarity in insects: the importance of host plant range. Biological Conservation, 105, 293–307.10.1016/S0006-3207(01)00203-8Search in Google Scholar

Housely, R.M., Kampf, A.R., Mills, S.J., Marty, J., and Thorne, B. (2011) The remarkable occurrence of rare secondary tellurium minerals at Otto Mountain, near Baker, California. Rocks & Minerals, 86, 132–142.10.1080/00357529.2011.537169Search in Google Scholar

Hughes, J.M., and Hadidiacos, C.G. (1985) Fingerite, Cu11O2(VO4)6, a new vanadium sublimate from Izalco volcano, El Salvador: descriptive mineralogy. American Mineralogist, 70, 193–196.Search in Google Scholar

Hull, P.M., Darroch, S.A.F., and Erwin, D.H. (2015) Rarity in mass extinctions and the future of ecosystems. Nature, 528, 345–351.10.1038/nature16160Search in Google Scholar

Hyndman, R.D., and Davis, E.E. (1992) A mechanism for the formation of methane hydrate and sea-floor bottom-simulating reflectors by vertical fluid expulsion. Journal of Geophysical Research, 97, 7025–7041.10.1029/91JB03061Search in Google Scholar

Hystad, G., Downs, R.T., and Hazen, R.M. (2015a) Mineral frequency distribution conforms to a Large Number of Rare Events model: Prediction of Earth’s missing minerals. Mathematical Geosciences, 47, 647–661, DOI: 10.1007/s11004-015-9600-3.Search in Google Scholar

Hystad, G., Downs, R.T., Grew, E.S., and Hazen, R.M. (2015b) Statistical analysis of mineral diversity and distribution: Earth’s mineralogy is unique. Earth & Planetary Science Letters, 426, 154–157.10.1016/j.epsl.2015.06.028Search in Google Scholar

Jain, M., Flynn, D.F.B., Prager, C.M., Hart, G.M., DeVan, C.M., Ahrestani, F.S., Plamer, M.I., Bunker, D.E., Knops, J.M.H., Jouseau, C.F., and Naeem, S. (2013) The importance of rare species: a trait-based assessment of rare species contributions to functional diversity and possible ecosystem function in tall-grass prairies. Ecology and Evolution, 4, 104–112.10.1002/ece3.915Search in Google Scholar

Jönsson, J., Jönsson, J., and Lövgren, L. (2006) Precipitation of secondary Fe(III) minerals from acid mine drainage. Applied Geochemistry, 21, 437–445.10.1016/j.apgeochem.2005.12.008Search in Google Scholar

Kim, H.-J., Ricardo, A., Illangkoon, H.I., Kim, M.J., Carrigan, M.A., Frye, F., and Benner, S.A. (2011) Synthesis of carbohydrates in mineral-guided prebiotic cycles. Journal of the American Chemical Society, 133, 9457–9468.10.1021/ja201769fSearch in Google Scholar

Krivovichev, S.V. (2012) Topological complexity of crystal structures: Quantitative approach. Acta Crystallographica, A68, 393–398.10.1107/S0108767312012044Search in Google Scholar

Kvenvolden, K.A. (1995) A review of the geochemistry of methane in natural gas hydrate. Organic Geochemistry, 23, 997–1008.10.1016/0146-6380(96)00002-2Search in Google Scholar

Levin, E.M., Robbins, C.R., and McMurdie, H.F. (1964) Phase Diagrams for Ceramists. The American Ceramic Society, Ohio, Columbus.Search in Google Scholar

Levin, H.L. (2009) The Earth Through Time, 9th ed. Wiley, Hoboken, New Jersey.Search in Google Scholar

Lyons, K., Brigham, C., Traut, B., and Schwartz, M. (2005) Rare species and ecosystem functioning. Conservation Biology, 19, 1019–1024.10.1111/j.1523-1739.2005.00106.xSearch in Google Scholar

Ma, C., and Krot, A.N. (2014) Hutcheonite, Ca3Ti2(SiAl2)O12, a new garnet mineral from the Allende meteorite: An alteration phase in a Ca-Al-rich inclusion. American Mineralogist, 99, 667–670.10.2138/am.2014.4761Search in Google Scholar

Ma, C. Beckett, J.R., and Rossman, G.R. (2014) Allendeite (Sc4Zr3O12) and hexamolyb-denum (Mo,Ru,Fe), two new minerals from an ultrarefractory inclusion from the Allende meteorite. American Mineralogist, 99, 654–666.10.2138/am.2014.4667Search in Google Scholar

Mouillot, D., Bellwood, D.R., Baraloto, C., Chave, J., Galzin, R., Harmelin-Vivien, M., Kulbicki, M., Lavergne, S., Lavorel, S., Mouquet, N., and others. (2013) Rare species support vulnerable functions in high-diversity ecosystems. PLoS Biology, DOI: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1001569.Search in Google Scholar

Nordstrom, D.K., Alpers, C.N., Ptacek, C.J., and Blowes, D.W. (2000) Negative pH and extremely acidic mine waters from Iron Mountain, California. Environmental Science & Technology, 34, 254–258.10.1021/es990646vSearch in Google Scholar

Petsch, D.K., Pinha, G.D., Dias, J.D., and Takeda, A.M. (2015) Temporal nestedness in Chironomidae and the importance of environmental and spatial factors in species rarity. Hydrobiologia, 745, 181–193.10.1007/s10750-014-2105-0Search in Google Scholar

Phillips, B., and Muan, A. (1958) Phase equilibria in the system CaO-iron oxide in air and at 1 atm O2 pressure. Journal of the American Ceramic Society, 41, 445–454.10.1111/j.1151-2916.1958.tb12893.xSearch in Google Scholar

Rabinowitz, D. (1981) Seven forms of rarity. In J. Synge, Ed., The Biological Aspects of Rare Plant Conservation, p. 205–217. Wiley, New York.Search in Google Scholar

Rabinowitz, D., Cairns, S., and Dillon, T. (1986) Seven forms of rarity and their frequency in the flora of the British Isles. In M.E. Soulé, Ed., Conservation Biology: The Science of Scarcity and Diversity, p. 182–204. Sinauer Associates, Sunderland, Massachusetts.Search in Google Scholar

Ricardo, A., Carrigan, M.A., Olcott, A.N., and Benner, S.A. (2004) Borate minerals stabilize ribose. Science, 303, 196.10.1126/science.1092464Search in Google Scholar

Richardson, S.J., Williams, P.A., Mason, N.W.H., Buxton, R.P., Courtney, S.P., Rance, B.D., Clarkson, B.R., Hoare, R.J.B., St. John, M.G., and Wiser, S.K. (2012) Rare species drive local trait diversity in two geographically disjunct examples of a naturally rare alpine ecosystem in New Zealand. Journal of Vegetation Science, 23, 626–639.10.1111/j.1654-1103.2012.01396.xSearch in Google Scholar

Ricklefs, R.E. (2000) Rarity and diversity in Amazonian forest trees. Trends in Ecology & Evolution, 15, 83–84.10.1016/S0169-5347(99)01718-8Search in Google Scholar

Rudnick, R.L. (Ed.) (2003) The Crust. Treatise on Geochemistry, vol. 3, Elsevier-Pergamon, Oxford, U.K.Search in Google Scholar

Rudnick, R.L. and Gao, S. (2005) Composition of the continental crust. In H.D. Holland and K.K. Turekian, Eds., The Crust, 3, p.1–64. Treatise on Geochemistry, Elsevier-Pergamon, Oxford, U.K.10.1016/B0-08-043751-6/03016-4Search in Google Scholar

Thompson, J.N. (2013) Relentless Evolution. University of Chicago Press, Illinois.10.7208/chicago/9780226018898.001.0001Search in Google Scholar

Tschauner, O., Ma, C., Beckett, J.R., Prescher, C., Prakapenka, V.B., and Rossman, G.R. (2014) Discovery of bridgmanite, the most abundant mineral in Earth, in a shocked meteorite. Science, 346, 1100–1102.10.1126/science.1259369Search in Google Scholar PubMed

Wächtershäuser, G. (1988) Before enzymes and templates: theory of surface metabolism. Microbiology Reviews, 52, 452–484.10.1128/mr.52.4.452-484.1988Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

Wedepohl, K.H. (1995) The composition of the continental crust. Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta, 59, 1217–1232.10.1180/minmag.1994.58A.2.234Search in Google Scholar

Welch, J.H., and Gutt, W. (1959) Tricalcium silicate and its stability within the system CaO-SiO2. Journal of the American Ceramic Society, 42, 11–15.10.1111/j.1151-2916.1959.tb09135.xSearch in Google Scholar

Zhang, J., Nielsen, S.E., Grainger, T.N., Kohler, M., Chipchar, T., and Farr, D.R. (2014) Sampling plant diversity and rarity at landscape scales: importance of sampling time in species detectability. PLoS ONE 9, e95334m DOI: 10.1371/journal.pone.0103920.Search in Google Scholar

© 2016 by Walter de Gruyter Berlin/Boston

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 3.0 License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Invited Centennial Article

- On the nature and significance of rarity in mineralogy

- Special collection: mechanisms, rates, and timescales of geochemical transport processes in the crust and mantle

- Zircon saturation and Zr diffusion in rhyolitic melts, and zircon growth geospeedometer

- Review

- On silica-rich granitoids and their eruptive equivalents

- Special collection: advances in ultrahigh-pressure metamorphism

- Discovery of in situ super-reducing, ultrahigh-pressure phases in the Luobusa ophiolitic chromitites, Tibet: new insights into the deep upper mantle and mantle transition zone

- Special collection: from magmas to ore deposits

- Uraninite from the Olympic Dam IOCG-U-Ag deposit: linking textural and compositional variation to temporal evolution

- Special collection: from magmas to ore deposits

- A story of olivine from the McIvor Hill complex (Tasmania, Australia): Clues to the origin of the Avebury metasomatic Ni sulfide deposit

- Special collection: perspectives on origins and evolution of crustal magmas

- The origin of extensive Neoarchean high-silica batholiths and the nature of intrusive complements to silicic ignimbrites: Insights from the Wyoming batholith, U.S.A.

- Special collection: perspectives on origins and evolution of crustal magmas

- From the Hadean to the Himalaya: 4.4 Ga of felsic terrestrial magmatism

- Spinels renaissance: the past, present, and future of those ubiquitous minerals and materials

- Compositional effects on the solubility of minor and trace elements in oxide spinel minerals: insights from crystal-crystal partition coefficients in chromite exsolution

- Spinels renaissance: the past, present, and future of those ubiquitous minerals and materials

- An X-ray magnetic circular dichroism (XMCD) study of Fe ordering in a synthetic MgAl2O4-Fe3O4 (spinel-magnetite) solid-solution series: Implications for magnetic properties and cation site ordering

- Research Article

- High concentrations of manganese and sulfur in deposits on Murray Ridge, Endeavour Crater, Mars

- Research Article

- A Cr3+ luminescence study of spodumene at high pressures: effects of site geometry, a phase transition, and a level-crossing

- Research Article

- Phase transitions between high- and low-temperature orthopyroxene in the Mg2Si2O6-Fe2Si2O6 system

- Research Article

- High-temperature and high-pressure behavior of carbonates in the ternary diagram CaCO3-MgCO3-FeCO3

- Research Article

- Natural Mg-Fe clinochlores: enthalpies of formation and dehydroxylation derived from calorimetric study

- Research Article

- Trace element thermometry of garnet-clinopyroxene pairs

- Research Article

- Constraints on the solid solubility of Hg, Tl, and Cd in arsenian pyrite

- Research Article

- Ni-phyllosilicates (garnierites) from the Falcondo Ni-laterite deposit (Dominican Republic): mineralogy, nanotextures, and formation mechanisms by HRTEM and AEM

- Research Article

- Cu diffusion in a basaltic melt

- Research Article

- High-pressure behavior of the polymorphs of FeOOH

- New Mineral Names

- New Mineral Names

Articles in the same Issue

- Invited Centennial Article

- On the nature and significance of rarity in mineralogy

- Special collection: mechanisms, rates, and timescales of geochemical transport processes in the crust and mantle

- Zircon saturation and Zr diffusion in rhyolitic melts, and zircon growth geospeedometer

- Review

- On silica-rich granitoids and their eruptive equivalents

- Special collection: advances in ultrahigh-pressure metamorphism

- Discovery of in situ super-reducing, ultrahigh-pressure phases in the Luobusa ophiolitic chromitites, Tibet: new insights into the deep upper mantle and mantle transition zone

- Special collection: from magmas to ore deposits

- Uraninite from the Olympic Dam IOCG-U-Ag deposit: linking textural and compositional variation to temporal evolution

- Special collection: from magmas to ore deposits

- A story of olivine from the McIvor Hill complex (Tasmania, Australia): Clues to the origin of the Avebury metasomatic Ni sulfide deposit

- Special collection: perspectives on origins and evolution of crustal magmas

- The origin of extensive Neoarchean high-silica batholiths and the nature of intrusive complements to silicic ignimbrites: Insights from the Wyoming batholith, U.S.A.

- Special collection: perspectives on origins and evolution of crustal magmas

- From the Hadean to the Himalaya: 4.4 Ga of felsic terrestrial magmatism

- Spinels renaissance: the past, present, and future of those ubiquitous minerals and materials

- Compositional effects on the solubility of minor and trace elements in oxide spinel minerals: insights from crystal-crystal partition coefficients in chromite exsolution

- Spinels renaissance: the past, present, and future of those ubiquitous minerals and materials

- An X-ray magnetic circular dichroism (XMCD) study of Fe ordering in a synthetic MgAl2O4-Fe3O4 (spinel-magnetite) solid-solution series: Implications for magnetic properties and cation site ordering

- Research Article

- High concentrations of manganese and sulfur in deposits on Murray Ridge, Endeavour Crater, Mars

- Research Article

- A Cr3+ luminescence study of spodumene at high pressures: effects of site geometry, a phase transition, and a level-crossing

- Research Article

- Phase transitions between high- and low-temperature orthopyroxene in the Mg2Si2O6-Fe2Si2O6 system

- Research Article

- High-temperature and high-pressure behavior of carbonates in the ternary diagram CaCO3-MgCO3-FeCO3

- Research Article

- Natural Mg-Fe clinochlores: enthalpies of formation and dehydroxylation derived from calorimetric study

- Research Article

- Trace element thermometry of garnet-clinopyroxene pairs

- Research Article

- Constraints on the solid solubility of Hg, Tl, and Cd in arsenian pyrite

- Research Article

- Ni-phyllosilicates (garnierites) from the Falcondo Ni-laterite deposit (Dominican Republic): mineralogy, nanotextures, and formation mechanisms by HRTEM and AEM

- Research Article

- Cu diffusion in a basaltic melt

- Research Article

- High-pressure behavior of the polymorphs of FeOOH

- New Mineral Names

- New Mineral Names