Effect of Hibiscus sabdariffa L. leaf flavonoid-rich extract on Nrf-2 and HO-1 pathways in liver damage of streptozotocin-induced diabetic rats

-

Basiru Olaitan Ajiboye

, Courage Dele Famusiwa

, Damilola Ifeoluwa Oyedare

Abstract

This study investigated the effects of flavonoid-rich extract from Hibiscus sabdariffa L. (Malvaceae) leaves on liver damage in streptozotocin-induced diabetic rats by evaluating various biochemical parameters, including the molecular gene expressions of Nrf-2 and HO-1 as well as histological parameters. The extract was found to significantly reduce liver damage, as evidenced by lower levels of fragmented DNA and protein carbonyl concentrations. Oxidative stress markers, including malondialdehyde (MDA) level, were also significantly (p < 0.05) decreased, while antioxidant biomarkers, like reduced glutathione (GSH), catalase (CAT), superoxide dismutase (SOD), glutathione peroxidase (GPx), and glutathione-S-transferase (GST) were enhanced. Additionally, the extract improved the activities of key liver enzymes, including phosphatases and transaminases, and increased albumin levels. Importantly, the study demonstrated that H. sabdariffa extract effectively regulated the expression of Nrf-2 and HO-1, suggesting a significant role in mitigating liver damage. These findings highlight its potential as a therapeutic agent for liver protection in diabetic conditions.

1 Introduction

Diabetes mellitus (DM), a global health epidemic, exerts a multifaceted burden on individuals and healthcare systems worldwide. There are two primary types of diabetes: type-1 diabetes mellitus (T1DM) and the more prevalent type-2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) [1]. Both of these types present significant public health challenges, contributing to higher disease rates and premature mortality. Recent data suggests that T2DM has affected approximately 500 million individuals globally, with an estimated 20 % increase by 2050. In contrast, T1DM, while less common at 15 cases per 100,000 individuals, remains a significant concern [2]. DM is characterized by abnormal blood glucose levels due to insulin deficiency or impaired insulin function, influenced by factors like body mass index (BMI), physical inactivity, genetics, and lifestyle choices [3]. T1DM typically involves the immune-mediated destruction of pancreatic β-cells, resulting in insulin deficiency and recognizable symptoms [4]. Prolonged hyperglycemia leads to oxidative stress, inflammation, and impaired insulin regulation. T2DM is increasingly prevalent, especially in developing regions, and is associated with insulin resistance, particularly in the liver and other vital organs, causing increased glucose production and reduced glycogen synthesis [5], 6].

While diabetes primarily manifests as a metabolic disorder characterized by hyperglycemia, it is also associated with a spectrum of debilitating complications, among which liver damage stands as a significant concern [7]. Hepatic disorders in diabetic patients not only compromise overall health but also pose considerable therapeutic challenges [8]. In this context, the present study endeavors to explore the potential therapeutic benefits of flavonoid-rich extracts from Hibiscus sabdariffa L. (Malvaceae) leaves in mitigating liver damage in streptozotocin-induced diabetic rats. Diabetes-induced liver damage, often termed “diabetic hepatopathy,” encompasses a range of pathological alterations, including steatosis, inflammation, oxidative stress, fibrosis, and impaired liver function. The cascade of events leading to liver damage in diabetes is intricate and multifactorial, driven by a complex interplay of metabolic dysregulation, inflammation, and oxidative stress [9], 10]. The liver, a central metabolic organ, is profoundly affected by systemic insulin resistance and hyperglycemia, which contribute to the progression of liver pathology. Current therapeutic options for managing diabetic hepatopathy are limited and often insufficient, necessitating the exploration of novel treatment modalities [11], 12]. In this context, the focus of the present study lies in the potential hepatoprotective effects of flavonoid-rich extracts from H. sabdariffa leaves. These extracts have garnered substantial attention due to their antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, and antidiabetic properties [13], 14].

The Nrf-2 system is considered to be a major cellular defense mechanism against oxidative stress. Nrf-2 plays an important role in cellular defense and in improving the removal of ROS by activating genes that encode phase II detoxifying enzymes and antioxidant enzymes, such as GCLM, HO-1, GPX, and GST [15], [16], [17]. Under basal conditions, Nrf-2 appears to be associated with actin-binding Keap1, which forms the Keap1-Nrf-2 complex. The Keap1-Nrf-2 complex prevents Nrf-2 from entering the nucleolus, which promotes its proteasomal degradation [18], 19]. Upon treatment in the cells with oxidants including H2O2, oxidative stress and conformational changes occur as a result of the oxidation of thiol-sensitive amino acids that are present in the Keap1-Nrf-2 complex and may drive the dissociation of Nrf-2 from Keap1. Nrf-2 then translocate into the nucleus, where it binds to the antioxidant response element (ARE) of ARE target genes, which leads to enhanced antioxidant enzyme expression [20], 21].

Flavonoids are a class of polyphenolic compounds known for their capacity to scavenge free radicals, modulate inflammatory responses, and influence various signaling pathways [22]. H. sabdariffa, a plant rich in flavonoids, has a long history of use in traditional medicine for its diverse therapeutic effects [23]. The study’s central hypothesis revolves around the involvement of the Nrf-2 (Nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor-2) and HO-1 (heme oxygenase-1) pathways in mediating the potential ameliorative effects of H. sabdariffa leaf flavonoid-rich extract on diabetic liver damage [24]. These pathways have been implicated in the cellular defense against oxidative stress, inflammation, and cellular damage. The activation of Nrf-2 and HO-1 pathways may enhance the liver’s resilience and potentially mitigate the adverse effects of diabetes [25], 26]. To investigate this hypothesis, the study employed streptozotocin-induced diabetic rats as a well-established animal model for studying diabetic hepatopathy. The rats were administered low and high doses of H. sabdariffa leaf flavonoid-rich extract, alongside a metformin control group. A comprehensive array of biochemical and histological parameters was considered to evaluate the extract efficacy in mitigating liver damage and elucidate their influence on the Nrf-2 and HO-1 pathways. The significance of this research extends beyond the scope of animal experimentation. It holds the promise of identifying a natural remedy that could potentially ameliorate liver damage in diabetic patients. Furthermore, the study may shed light on the molecular mechanisms underlying the hepatoprotective effects of flavonoid-rich extracts and provide insights into the therapeutic potential of modulating the Nrf-2 and HO-1 pathways, all with the aim of advancing our understanding of the pathogenesis of diabetic hepatopathy and the potential avenues for its management.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Plant material

H. sabdariffa leaves were procured from Ojo-Oba market at Ado-Ekiti, Ekiti State, Nigeria. It was identified and authenticated by a senior taxonomist at the Forestry Research Institute of Nigeria (FRIN), Ibadan, Nigeria, with voucher number FHI:113742.

2.2 Chemicals

Absolute ethanol (EtOH), concentrated and diluted ammonium hydroxide (NH4OH), 10 % formalin, fructose, methanol (MeOH), phosphate buffer, sodium citrate buffer, streptozotocin (STZ), and sulphuric acid (H2SO4) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (Germany). All enzyme kits were manufactured by Randox Laboratory (Crumlin, UK).

2.3 H. sabdariffa extraction

One gram of leaves dried at room temperature and pulverised with an electric blender was defatted in 80 % MeOH by maceration for 72 h, then filtered through a muslin cloth and concentrated using a rotary evaporator. Subsequently, 20 g of the obtained sample was dissolved in 200 mL of 10 % H2SO4 and hydrolysed by heating in a water bath for 30 min at 100 °C. A step on ice for 15 min resulted in the precipitation of the flavonoid aglycones, which were then dissolved in 50 mL of 95 % warm EtOH, filtered in a 100 mL volumetric flask and made up to volume again with the same solvent, to be concentrated with a rotary evaporator. The filtrate was precipitated using concentrated NH4OH. The solution was allowed to settle and the precipitates were collected and rinsed with diluted NH4OH to obtain the flavonoid-rich extract, which was stored at 4 °C until use.

2.4 Experimental animals

A total of 40 male Wistar rats weighing (150 ± 20 g) were obtained from Show-Gold Animal House Idofin, Oye-Ekiti, Ekiti state, Nigeria. They were housed in groups of five (5) in a conventional laboratory setting with a room temperature of 22 ± 20 °C and a 12-h light/dark cycle. The animals were acclimatized for a week.

2.5 Diabetes induction

The rats were fed with standard pellet chow. Rats to be induced to diabetes were fed 20 % fructose water in addition to standard feed for one week, while normal control rats (NC) were given standard feed and water, as previously described by Salau et al. [27]. Twelve hours prior to administration by intraperitoneal injection of streptozotocin (STZ) (0.23 g dissolved in sodium citrate buffer pH 7.4 at a concentration of 0.1 M), the feed was removed from the cages leaving only water. Rats were administered 40 mg/kg body weight of STZ and an equal volume of citrate buffer pH 7.4 to the NC group. Animals with fasting blood glucose above 250 mg/dL 3 days after STZ injection were considered diabetic and were used for this study [28].

2.6 Experimental design and animal treatment

After DM induction, the animals were weighed and divided into five groups, each consisting of eight rats. Group I: rats without induced diabetes (normal control, NC); Group II: rats with non-induced diabetes (diabetic control, DC); Group III: rats with induced diabetes treated with low doses (150 mg/kg body weight) of flavonoid-rich H. sabdariffa leaf extract (LDHDFL); Group IV: rats with induced diabetes treated with high doses (300 mg/kg body weight) of flavonoid-rich H. sabdariffa leaf extract (HDHDFL); Group V: rats with induced diabetes treated with 200 mg/kg metformin (MET). The doses of the extract were based on findings from a preliminary study [29].

2.7 Tissue collection and processing

On day 22, rats were sacrificed under chloroform anaesthesia. Blood samples were taken immediately by cardiac puncture from each rat, collected in a plain vial and centrifuged for 15 min at 5,000 rpm. The serum was extracted and refrigerated until use. The liver from each animal was taken, washed in normal saline, cleaned with filter paper, weighed and homogenized in 0.1 M potassium phosphate buffer pH 6.5, then centrifuged at 4,000 rpm for 15 min before further analysis [30].

2.8 Biomolecular degradation biomarker assays

2.8.1 Percentage of fragmented DNA

DNA fragmentation was measured by the diphenylamine (DPA) spectrophotometric method described by Wolozin et al. [31] Intact DNA was separated from fragmented DNA by centrifugal sedimentation followed by precipitation and quantification using DPA. To minimize the formation of oxidative artifacts during isolation, 2,2,6,6-tetramethylpiperidinoxyl (20 mM final concentration) was added to all solutions and all procedures were performed on ice. Briefly, hepatocytes (1 × 106 in 1 mL PBS) were put in a 1.5 mL centrifuge tube (tube B) and centrifuged (200 g, 4 °C, 10 min) to obtain a cell pellet. The supernatants were transferred to fresh tubes (tube S). The obtained pellet (tube B) was suspended in 1 mL TTE (Tris Triton EDTA) buffer, pH 7.4 (TE buffer with 0.2 % Triton X-100) and centrifuged at 20,000 g (4 °C, 10 min). The supernatant obtained was transferred to fresh tubes (tube T) and the resulting pellets resuspended in TTE buffer. TCA (trichloro acetic acid, 1 mL of 25 %) was added to tubes T, B and S and vortexed vigorously. Tubes were kept overnight at 4 °C followed by centrifugation at 20,000 g (4 °C, 10 min). The supernatant was discarded and the pellet was hydrolysed by the addition of 160 pl of 5 % TCA followed by heating at 90 °C for 15 min. This was followed by the addition of 320 μL of freshly prepared DPA. The colour was developed by incubation at 37 °C for 4 h. The optical density of the solution was read at 600 nm in an ELISA reader. Percentage DNA Fragmentation was calculated using the following formula: % Fragmented DNA = S + T/S + T + B × 100. An agarose gel electrophoresis was also performed to analyse DNA fragmentation as described elsewhere.

2.8.2 Protein carbonyl content

According to Levine et al. [32], the sample supernatant was incubated with DNPH for 60 min at room temperature. Following precipitation by adding 20 % trichloroacetic acid, the pellet was washed with acetone and dissolved in 1 mL of Tris buffer containing sodium dodecyl sulphate (8 % w/v, pH 7.4). The absorbance was measured at 360 nm.

2.9 Oxidative stress biomarker assays

2.9.1 Malondialdehyde (MDA) level

To quantify the concentration of MDA in the liver, the method of Oloyede et al. [33] was followed. Briefly, a portion of TBA reagent (2 mL of 0.7 % and 1 mL of TCA) was added to 2 mL of sample. The mixture was heated in a water bath at 100 °C for 20 min. It was then cooled and centrifuged at 78 g (4,000 rpm) for 10 min. The absorbance of the supernatant was read at a wavelength of 540 nm against a reference blank of distilled water after centrifugation for a further 10 min.

2.9.2 Superoxide dismutase (SOD) activity

For SOD activity, the method described by Misra and Fridovich [12] was used. Tissue homogenate of 0.5 mL was diluted in 4.5 mL of distilled water (1:10) dilution factor. An aliquot of 0.2 mL of diluted serum sample was added to 2.5 mL of 0.05 M carbonate buffer (pH 10.2) to equilibrate in a spectrophotometric cuvette and the reaction was started by adding 0.3 mL of substrate (0.3 mM Epinephrine) and 0.2 mL of distilled water. The increase in absorbance at 480 nm was monitored every 30 s for 2½ min.

2.9.3 Glutathione S-transferase (GST) activity

GST was detected following the method of Habig et al. [34], with some modifications. For GST (CDNB) assay, the reaction medium contained 0.1 M potassium phosphate buffer pH 7.5 or 6.5, 1.0 mm GSH, 1.0 mm CDNB, 1 % absolute ethanol, and protein in a total volume of 1.0 mL. For GST (DCNB) assay, the reaction medium contained 0.1 m potassium phosphate buffer, pH 7.5, 5.0 or 1.0 mm GSH, 1.0 mm DCNB, 1 % absolute ethanol, and protein in a total volume of 1.0 mL. The reaction, conducted at 25 °C, was initiated by the addition of CDNB or DCNB, and the change in A340 or A345, respectively, was monitored for 120 s with a spectrophotometer (model DU-65, Beckman). All initial rates were corrected for the background nonenzymatic reaction. One unit of activity is defined as the formation of 1 μmol product min−1 at 25 °C (extinction coefficient at 340 nm = 9.6 mm−1 cm−1 for CDNB; extinction coefficient at 345 nm = 8.5 mm−1 cm−1 for DCNB).

2.9.4 Catalase (CAT) activity

CAT activity was assessed using the Beers and Sizer method [35]. Hydrogen peroxide (0.036 % w/w, 2.9 mL) was added and mixed with appropriately diluted homogenate (0.1 mL). A blank was prepared containing potassium phosphate buffer (50 mM, pH 7.0; 3.0 mL). The time required for the A240 nm of the reaction mixture to decrease from 0.45 to 0.40 absorbance units was recorded.

2.9.5 Glutathione peroxidase (GPx) activity

GPx activity was assayed following Haque et al. [36]. 500 μL of 0.1 M phosphate buffer (pH 7.4), 100 μL of 10 mM sodium azide, 200 μL of 4 mM GSH, 100 μL of 2.5 mM H2O2 were added to 500 μL of the liver homogenate sample, after which 600 μL of distilled water was added and mixed thoroughly. The reaction mixture was incubated at 37 °C for 3 min, then 0.5 ml 10 % TCA was added and centrifuged at 3,000 rpm for 5 min. To 1 mL of each of the supernatants, 2 mL of K2HPO4 and 1 mL of 0.04 % DTNB were added and the absorbance was read at 412 nm against a blank.

2.9.6 Reduced glutathione (GSH) level

GSH level in the liver homogenate was defined according to the Ellman method [37]. Briefly, 1.0 mL of liver homogenate was added to 0.1 mL of 25 % trichloroacetic acid (TCA) and the precipitate was removed by centrifugation at 5,000 g for 10 min. The supernatant (0.1 mL) was added to 2 mL of 0.6 mM DTNB prepared in 0.2 M sodium phosphate buffer (pH 8.0). The absorbance was read at 412 nm.

2.10 Phosphatase and transaminase activities

The activities of ALP, ACP, AST, and ALT were determined using commercial Randox kits, and the manufacturer procedures were followed. The serum level of albumin was determined by an automated analyzer (Architect c8000, Clinical Chemistry System, USA) via a Randox kit in line with the manufacturer’s instructions.

2.11 Relative gene expression of Nrf-2 and HO-1

Total RNA was isolated from tissue samples with Quick-RNA MiniPrep™ Kit (Zymo Research). The DNA contaminant was removed following DNAse I (NEB, Cat: M0303S) treatment. The RNA was quantified at 260 nm and the purity was confirmed at 260 nm and 280 nm using an A&E Spectrophotometer (A&E Lab. UK). Then, this was converted into cDNA using a cDNA synthesis kit based. Lastly, the obtained solution was subjected to polymerase chain reaction PCR amplification and agarose gel electrophoresis. The primer sequences used are illustrated in Table 1. Hence, the quantification of band intensity was done using “image J” software [38].

Primer sequences.

| Enzyme | Forward primer | Reverse primer |

|---|---|---|

| Nrf-2 | 5′- CAGCGACGGAAAGAGTATGA-3′ | 5′- TGGGCAACCTGGGAGTAG-3′ |

| HO-1 | 5′- CAACATCCAGCTCTTTGAGG-3′ | 5′- GGCAGAATCTTGCACTTTG-3′ |

| GAPDH | 5′-GCAAGGATACTGAGAGCAAGAG-3′ | 5′-CATCTCCCTCACAATTCCATCC-3′ |

2.12 Histopathological examination

Haematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining was used for histopathological examination, as reported by Blume et al. [39].

2.13 Statistical analysis

All results were reported as mean ± SD (n = 8). Statistical significances were assessed by ANOVA followed by Tukey’s multiple comparisons (post-hoc test) using software GraphPad prism (Version 5.0). P < 0.05 was set as statistically significant.

3 Results

3.1 Modulation of biomolecular degradation biomarkers in the liver of STZ-induced diabetic rats by the flavonoid-rich H. sabdariffa extract

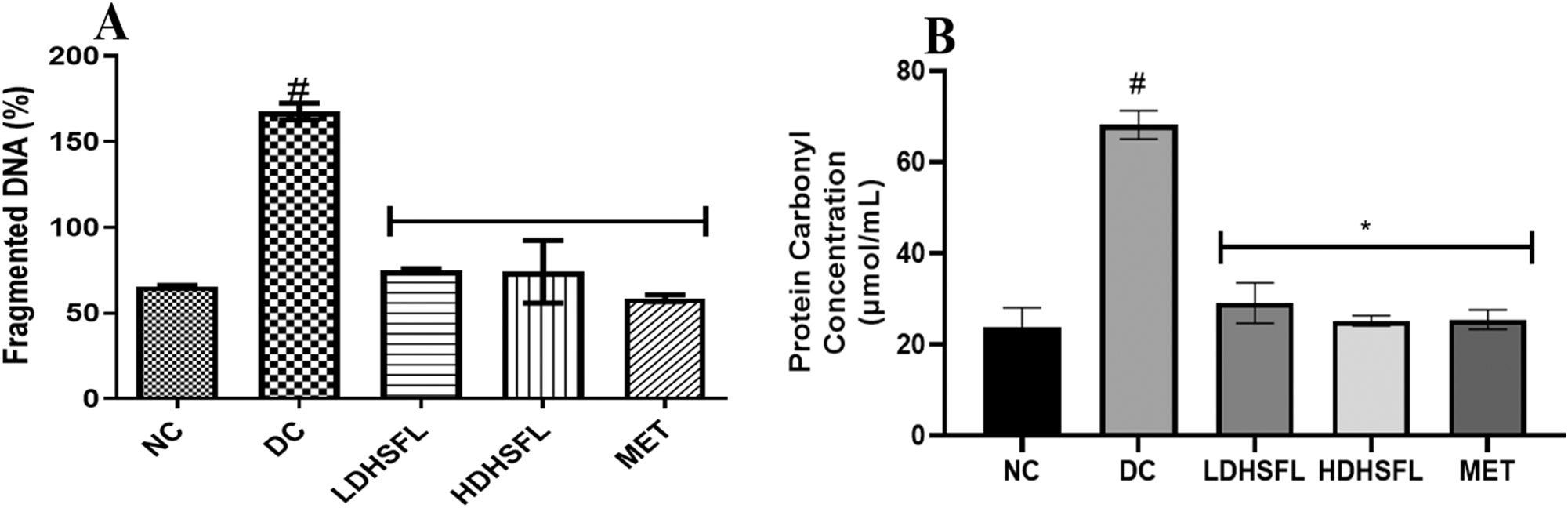

There was a significant (p < 0.05) increase in nucleic acid and protein degradation (measured by percentage of liver fragmented DNA and protein carbonyl concentration respectively) in the diabetic untreated group (DC) when compared with the normal (NC) (Figure 1). However, these misdemeanors were significantly (p < 0.05) attenuated in a dose-dependent manner by administration of both low and high doses of the extract, similar to that in the standard MET-administered group.

Percentage of liver fragmented DNA and protein carbonyl concentration in STZ-induced diabetic rats after administration of flavonoid-rich H. sabdariffa leaf extract. Each value represents the mean of eight measurements ± SD #p < 0.05 versus NC, *p < 0.05 versus DC. NC, normal control; DC, diabetic control; LDHSFL, diabetic rats given a low dose (150 mg/kg body weight) of flavonoid-rich extract of H. sabdariffa; HDHSFL, diabetic rats given a high dose (300 mg/kg body weight) of flavonoid-rich extract of H. sabdariffa; MET, diabetic rats given 200 mg/kg of metformin.

3.2 Modulation of redox stress biomarkers in the liver of STZ-induced diabetic rats by the flavonoid-rich extract from H. sabdariffa

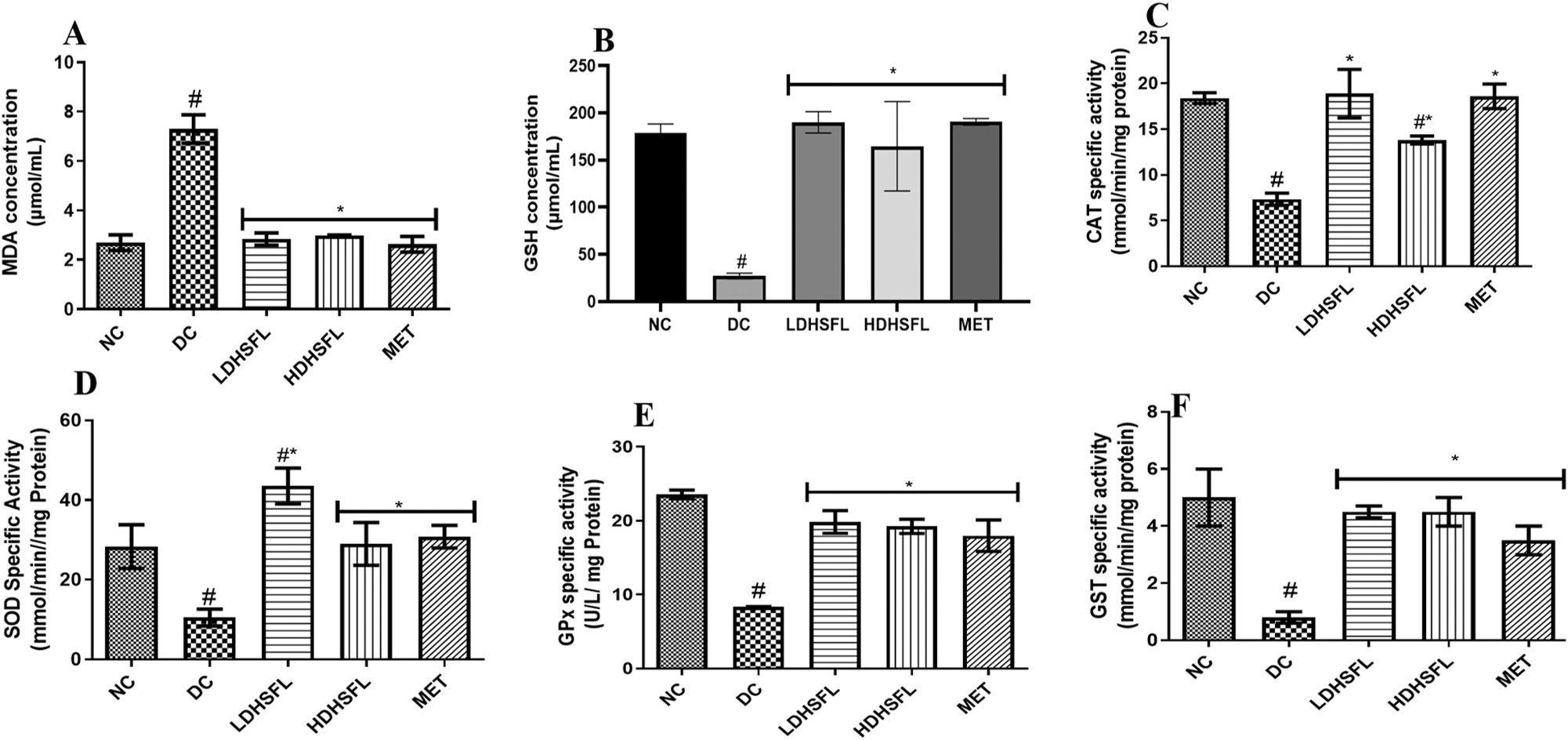

As shown in Figure 2, the DC group exhibited a significant increase (p < 0.05) in lipid peroxidation, as indicated by elevated MDA levels. Additionally, there was a notable decrease (p < 0.05) in the activities of antioxidant enzymes (GST, CAT, GPx, and SOD) and a significant reduction (p < 0.05) in GSH levels compared to the NC group. However, these adverse effects were significantly mitigated (p < 0.05) by both low and high doses of the H. sabdariffa extract, as well as by the standard treatment with MET, bringing the values closer to normal levels.

Oxidative stress biomarkers in STZ-induced diabetic rats after administration of flavonoid-rich H. sabdariffa leaf extract. Each value represents the mean of eight measurements ± SD #p < 0.05 versus NC, *p < 0.05 versus DC. NC, normal control; DC, diabetic control; LDHSFL, diabetic rats given a low dose (150 mg/kg body weight) of flavonoid-rich extract of H. sabdariffa; HDHSFL, diabetic rats given a high dose (300 mg/kg body weight) of flavonoid-rich extract of H. sabdariffa; MET, diabetic rats given 200 mg/kg of metformin; MDA, malondialdehyde; GSH, reduced glutathione; CAT, catalase; SOD, superoxide dismutase; GPx, glutathione peroxidase; GST, glutathione-S-transferase.

3.3 Modulation of phosphatase activity in the liver of STZ-induced diabetic rats by the flavonoid-rich extract from H. sabdariffa

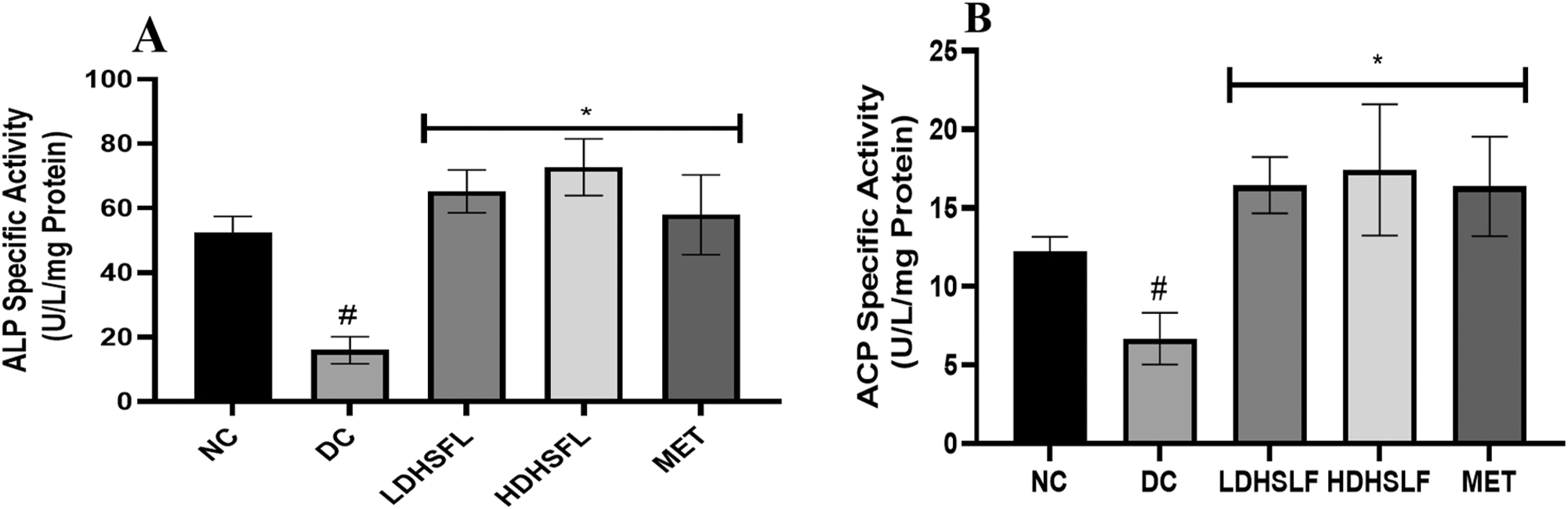

Figure 3 revealed the effect of H. sabdariffa flavonoid-rich extract on phosphatase activities in the liver of STZ-induced diabetic rats. There was a significant (p < 0.05) decrease in the activities of alkaline phosphatase (ALP) and acid phosphatase (ACP) in the diabetic untreated group (DC) when compared with the normal (NC). Nevertheless, these observed anomalies were remarkably (p < 0.05) reversed to near-normal conditions by the administration of low and high doses of flavonoid-rich extract of H. sabdariffa and standard metformin.

Phosphatase activities in STZ-induced diabetic rats after administration of flavonoid-rich H. sabdariffa leaf extract. each value represents the mean of eight measurements ± SD #p < 0.05 versus NC, *p < 0.05 versus DC. NC, normal control; DC, diabetic control; LDHSFL, diabetic rats given a low dose (150 mg/kg body weight) of flavonoid-rich extract of H. sabdariffa; HDHSFL, diabetic rats given a high dose (300 mg/kg body weight) of flavonoid-rich extract of H. sabdariffa; MET, diabetic rats given 200 mg/kg of metformin; ALP, alkaline phosphatase; ACP, acid phosphatase.

3.4 Modulation of hepatic transaminase activity and albumin levels by H. sabdariffa flavonoid-rich extract in STZ-induced diabetic rats

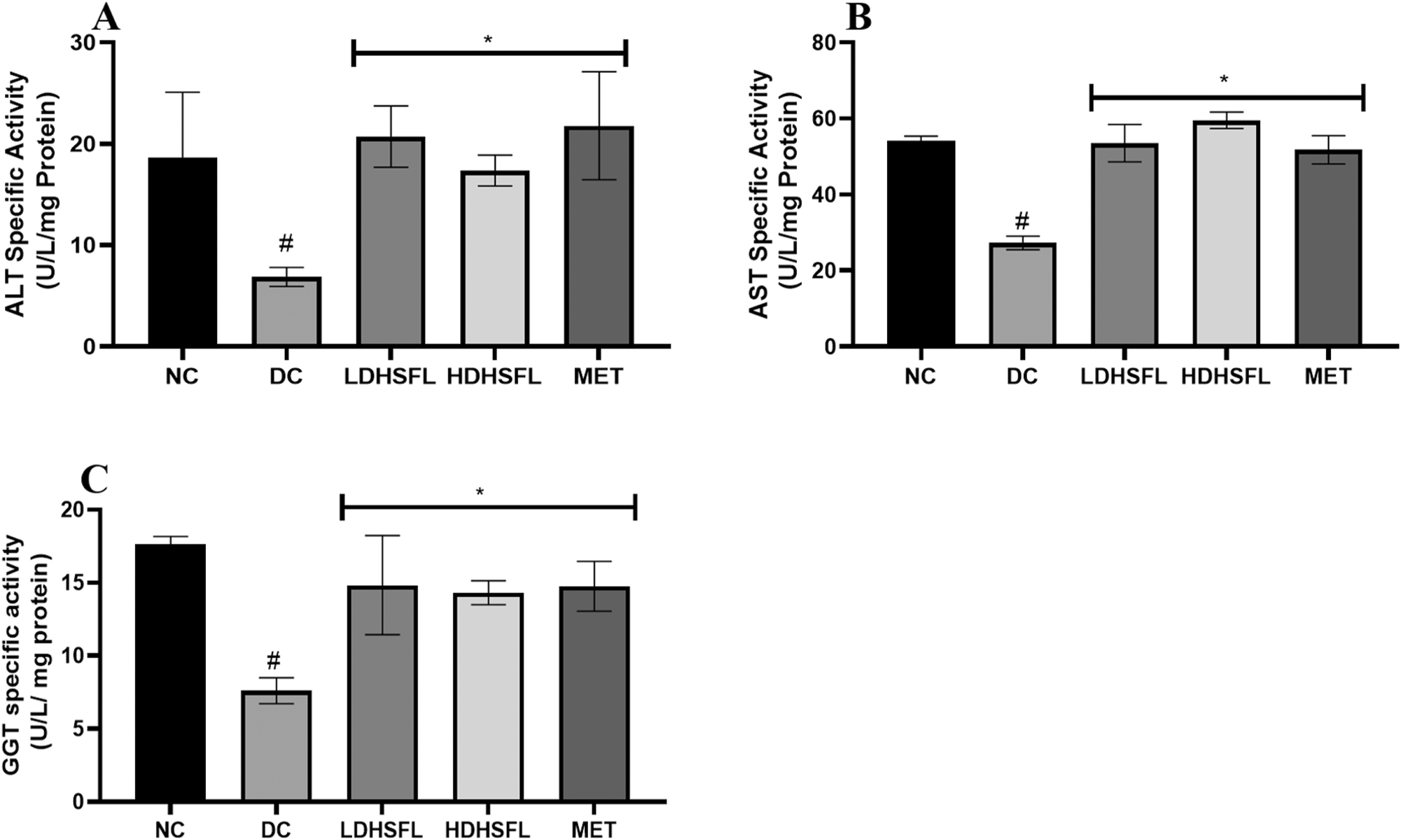

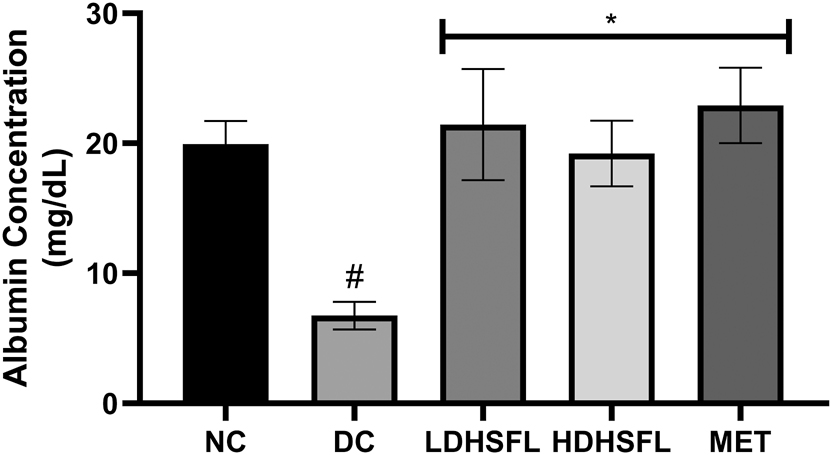

In DC untreated rats, the administration of STZ resulted in a significant (p < 0.05) reduction in hepatic transaminase activities and albumin levels, as demonstrated in Figures 4 and 5, respectively, compared to the NC rats. However, treatments with low and high doses of H. sabdariffa flavonoid-rich extract, similarly to MET, significantly reversed and normalized (p < 0.05) these negative changes in alanine transaminase (ALT), aspartate transaminase (AST) and gamma-glutamyl transferase (GGT) activity, as well as in albumin concentration.

Transaminase activities in STZ-induced diabetic rats after administration of flavonoid-rich H. sabdariffa leaf extract. each value represents the mean Of eight measurements ± SD #p < 0.05 versus NC, *p < 0.05 versus DC. NC, normal control; DC, diabetic control; LDHSFL, diabetic rats given a low dose (150 mg/kg body weight) of flavonoid-rich extract of H. sabdariffa; HDHSFL, diabetic rats given a high dose (300 mg/kg body weight) of flavonoid-rich extract of H. sabdariffa; MET, diabetic rats given 200 mg/kg of metformin; ALT, alanine transaminase; AST, aspartate transaminase; GGT, gamma-glutamyl transferase.

Albumin level in STZ-induced diabetic rats after administration of flavonoid-rich H. sabdariffa leaf extract. each value represents the mean of eight measurements ± SD #p < 0.05 versus NC, *p < 0.05 versus DC. NC, normal control; DC, diabetic control; LDHSFL, diabetic rats given a low dose (150 mg/kg body weight) of flavonoid-rich extract of H. sabdariffa; HDHSFL, diabetic rats given a high dose (300 mg/kg body weight) of flavonoid-rich extract of H. sabdariffa; MET, diabetic rats given 200 mg/kg of metformin.

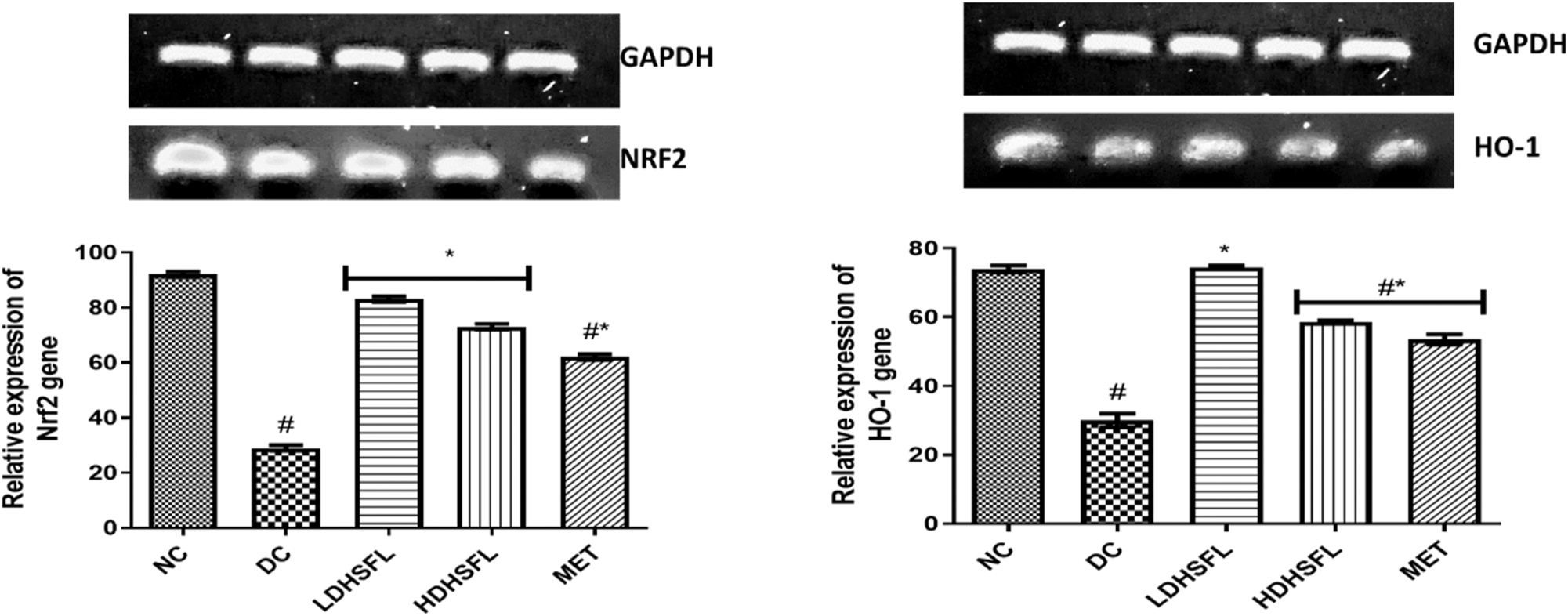

3.5 Modulation of the relative gene expression levels of Nrf-2 and HO-1 genes by H. sabdariffa flavonoid-rich extract in STZ-induced diabetic rats

Figure 6 illustrates the relative gene expression profiles of nuclear erythroid-related factor-2 (Nrf-2) and heme oxygenase-1 (HO-1) in STZ-induced diabetic rats, along with the restorative effects of the H. sabdariffa extract. Using glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) as the house-keeping gene, a significant (p < 0.05) down-regulation of Nrf-2 and HO-1 genes was observed in the DC group compared to the NC group. Treatment with H. sabdariffa, as well as the standard drug, significantly (p < 0.05) up-regulated and restored their expression in a dose-dependent manner.

Relative gene expression of Nrf2 and HO-1 in STZ-induced diabetic rats after administration of flavonoid-rich H. sabdariffa leaf extract. Each value represents the mean of eight measurements ± SD #p < 0.05 versus NC, *p < 0.05 versus DC. NC, normal control; DC, diabetic control; LDHSFL, diabetic rats given a low dose (150 mg/kg body weight) of flavonoid-rich extract of H. sabdariffa; HDHSFL, diabetic rats given a high dose (300 mg/kg body weight) of flavonoid-rich extract of H. sabdariffa; MET, diabetic rats given 200 mg/kg of metformin.

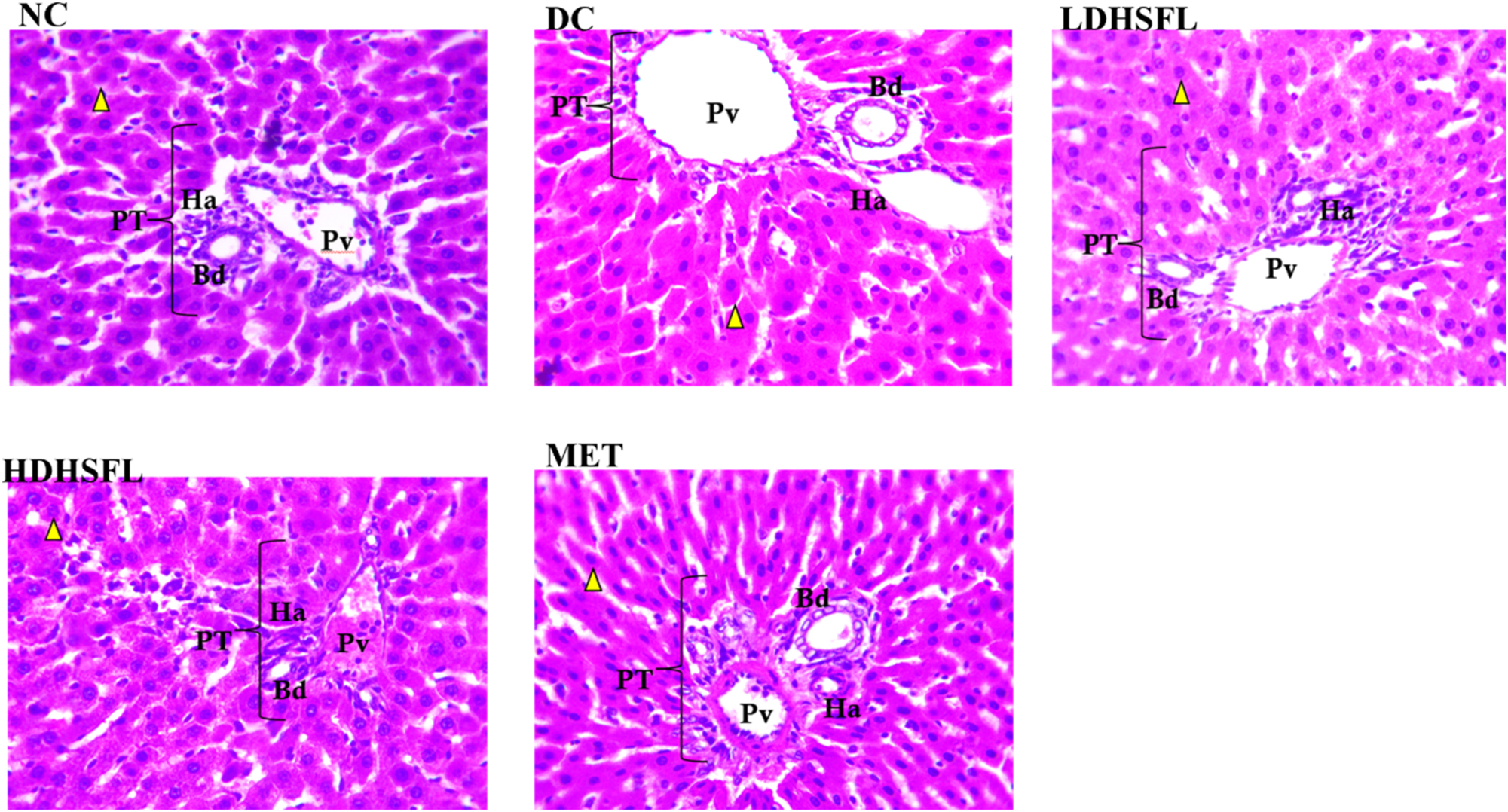

3.6 Impact of H. sabdariffa flavonoid-rich extract on liver histopathological alterations in rats with STZ-induced diabetes

The liver histology of the DC group showed harmful alterations, including blood vessel dilation, hepatocyte vacuolation, and abnormal pyknotic nuclei, compared to the NC group. However, these detrimental changes were significantly improved in the diabetic rats treated with both low and high doses of H. sabdariffa extract (LDHSFL and HDHSFL, respectively), as well as in those treated with the standard MET, as observed in the photomicrographs (Figure 7).

Liver histoarchitecture in STZ-induced diabetic rats after administration of flavonoid-rich H. sabdariffa leaf extract, showing the hepatocytes (yellow arrowhead) and portal triad (bile duct, hepatic artery, portal vein). NC, normal control with normal pyknotic hepatocyte nuclei and portal area; DC, diabetic control with dilation of the blood vessels and vacuolations of the hepatocytes; LDHSFL, diabetic rats given a low dose (150 mg/kg body weight) of flavonoid-rich extract of H. sabdariffa, with normal pyknotic hepatocyte nuclei and portal area. HDHSFL, diabetic rats given a high dose (300 mg/kg body weight) of flavonoid-rich extract of H. sabdariffa, with normal pyknotic hepatocyte nuclei and portal area. MET, diabetic rats given 200 mg/kg of metformin, with normal pyknotic hepatocyte nuclei and portal area.

4 Discussion

DM is a widespread metabolic disorder marked by persistently high blood sugar levels, which can cause progressive damage to various internal organs, including the liver [40], 41]. People with DM are at increased risk of liver complications such as abnormal enzyme levels, nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD), cirrhosis, hepatocellular carcinoma, and acute liver failure. This liver damage results from heightened oxidative stress and abnormal inflammatory responses [42], 43].

During liver injury, excessive production of free radicals and ROS damages essential biomolecules, including lipids, DNA, proteins, and cells, and activates pro-inflammatory genes [44]. The excessive ROS further aggravate inflammation and tissue damage. The liver plays a crucial role in regulating blood glucose levels through processes like glycogenesis and gluconeogenesis. When these processes are impaired and combined with oxidative stress, various types of liver damage can occur [45]. Thus, therapeutic strategies that balance carbohydrate metabolism and enhance antioxidant defenses may help protect against diabetes-induced liver injury [46]. Nrf-2 (Nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2) is a key target in treating and preventing such diseases because it controls the expression of antioxidant and protective genes [47]. As a master regulator of cellular defense, Nrf-2 is essential in managing antioxidant and anti-inflammatory responses. Its dysregulation is linked to chronic inflammatory diseases. Nrf-2 has demonstrated protective effects in various liver conditions, including acute liver injury, NAFLD, liver fibrosis, and hepatic ischemia-reperfusion injury (IRI) [48], 49]. Activation of Nrf-2 can reduce liver damage and inflammation caused by substances such as cadmium, STZ, LPS, D-GalN, carbon tetrachloride, and acetaminophen [50], 51]. Additionally, the Keap1-Nrf-2 complex has shown protective effects in orthotopic liver transplantation. Although recent studies underscore the potential of Nrf-2-based therapies for liver diseases, clinical trials in the USA are still pending for patients with acute liver failure [52].

STZ administration resulted in a significant (p < 0.05) increase in hepatic protein carbonyl levels and fragmented DNA in untreated diabetic rats. This indicates heightened degradation and dysfunction of biomolecules, consistent with previous studies [53], 54]. Measuring fragmented DNA in the liver is crucial for assessing liver cell damage, especially in liver diseases like hepatopathy [55]. Liver diseases often entail varying degrees of liver cell damage, and measuring fragmented DNA provides valuable insights into the damage’s severity. In cases where diabetes is a contributing factor, persistently high blood sugar levels can induce oxidative stress and liver inflammation, leading to cellular DNA damage [56]. Thus, quantifying fragmented DNA is a key marker for evaluating liver damage severity in diabetic individuals [57]. Fragmented DNA not only signals activated inflammation but also represents the extent of DNA damage from oxidative stress. As liver damage worsens, increased fragmented DNA levels provide important information for tailoring treatment strategies [58].

Protein carbonyl levels plays are another critical marker in diabetes, reflecting oxidative stress. Protein carbonylation, a post-translational modification resulting from amino acid oxidation, indicates an imbalance between ROS production and antioxidant defenses [59], 60]. Elevated protein carbonyls are common in poorly controlled diabetes and can lead to damage of cellular proteins, contributing to complications such as neuropathy and retinopathy [61], 62]. Monitoring protein carbonyl levels helps assess the risk and severity of these complications and the effectiveness of interventions targeting oxidative stress [63].

Remarkably, administration of the H. sabdariffa flavonoid-rich extract significantly (p < 0.05) alleviated the abnormalities caused by STZ intoxication, showing a dose-dependent improvement comparable to that of metformin. This underscores the extract potent protective properties, which counteract the degradation and dysfunction of biomacromolecules linked to diabetes, aligning with previously reported studies [28], 64].

This study found that STZ-induced diabetes resulted in a significant (p < 0.05) increase in lipid peroxidation, as evidenced by elevated MDA levels. This was accompanied by a notable (p < 0.05) decrease in the activity of crucial antioxidant enzymes (GST, CAT, GPx, SOD) and reduced GSH levels, aligning with previous research [65], 66]. The body antioxidant defense system depends on a multifaceted interplay of antioxidant compounds and enzymes such as SOD, CAT, GPx, and GST. Superoxide radicals, primary ROS generated during aerobic metabolism, are initially converted by SOD into less harmful H2O2 [67], 68]. CAT or GPx then further break down H2O2 into water and molecular oxygen, with GPx also reducing lipid peroxides and other toxic organic hydroperoxides. Deficiencies in these key antioxidant components can lead to oxidative stress and cellular damage [68]. GST facilitates the conjugation of GSH with xenobiotic compounds [69], but in STZ-induced diabetic rats, GSH levels were significantly depleted due to its involvement in GST-catalyzed conjugation with STZ. Reduced GST activity, which promotes the conjugation of STZ and GSH, has also been observed in such models [70]. Additionally, the activities of essential antioxidant enzymes (CAT, GPX, SOD) were markedly diminished in response to increased ROS, reflecting a cellular attempt to manage oxidative stress and prevent diabetes-related complications [71]. In contrast, NC rats did not show elevated antioxidant enzyme activities, as they did not produce ROS. DC rats, however, faced increased ROS levels due to pancreatic β-cell damage, leading to insulin deficiency and heightened oxidative stress [72]. Enhancing antioxidant enzyme activity and gene expression is crucial for managing such oxidative stress. Consistent with this study, previous research has reported increased MDA activity in the pancreas of STZ-induced diabetic rats, which can damage various biomolecules including enzymes, phospholipids, proteins, nucleic acids, and cell membranes [73].

Diabetes patients experience significant oxidative stress, characterized by increased oxidative products and diminished free radical scavenging capabilities [68]. Effective protection against free radical damage involves reducing lipid peroxidation, preserving cell membrane integrity, and maintaining normal cellular functions [74], 75]. The integrity of cell membranes is critical for the function of insulin receptors, which are membrane-bound [76]. Notably, administration of H. sabdariffa extract significantly (p < 0.05) alleviated these abnormalities in a dose-dependent manner, similar to the effects observed with metformin. This emphasizes the potent antioxidant properties of the extract, which mitigate oxidative stress and excessive free radicals associated with diabetes, consistent with previous studies [77].

In untreated diabetic rats, there was a significant (p < 0.05) reduction in phosphatase enzyme activities, including alkaline phosphatase (ALP) and acid phosphatase (ACP), in line with previous research [78]. ALP and ACP play distinct roles in diabetes and hepatopathy [79]. ALP, primarily found in the liver, bile ducts, and bones, serves as a marker for liver function [80]. Elevated ALP levels can indicate liver damage or hepatopathy. ACP, located mainly in lysosomes, reflects cellular activity and integrity [81], and while not a standard liver function marker, changes in its levels can be observed in liver diseases associated with diabetes. Monitoring ALP and ACP levels provides insights into liver health and potential complications related to diabetes [82].

Phosphatases are crucial in STZ-induced toxicity and diabetes management. In STZ-induced diabetes, phosphatases, including ACP, are involved in cellular responses to STZ toxicity, participating in signaling pathways and cellular processes [83]. They also regulate critical cellular functions related to glucose metabolism, insulin signaling, and oxidative stress response [71]. Phosphatases can affect insulin receptor phosphorylation and glycogen metabolism by dephosphorylating key enzymes [84]. Additionally, they help manage oxidative stress by modulating the phosphorylation status of proteins involved in antioxidant defense, such as the Nrf-2 pathway [85]. Activation of Nrf-2 stimulates the expression of antioxidant and phase II detoxification enzymes, protecting cells from oxidative damage [58]. The H. sabdariffa extract significantly (p < 0.05) mitigated abnormalities in phosphatase activity, indicating potential restorative effects on energy imbalance and hormonal regulation in diabetic rats [86], 87].

STZ-induced diabetes resulted in a significant (p < 0.05) reduction in hepatic transaminases, including alanine transaminase (ALT), aspartate transaminase (AST), and gamma-glutamyl transferase (GGT), as well as liver albumin levels, compared to normal controls, consistent with previous findings [88]. ALT, AST, and GGT are liver function markers, with ALT and AST indicating hepatocellular health and GGT reflecting biliary tract function [89]. Elevated ALT and AST levels suggest liver damage, while GGT is associated with various pathological conditions including diabetes [90], 91]. Decreased albumin levels, which are synthesized by the liver, indicate liver damage and are critical for maintaining overall health and fluid balance [92], 93]. The H. sabdariffa extract significantly improved transaminase activities and liver albumin levels in a dose-dependent manner, suggesting potential hepatoprotective effects and improved insulin resistance [94], 95].

Gene expression of Nrf-2 and HO-1 was significantly (p < 0.05) downregulated in the livers of STZ-induced diabetic rats compared to normal controls [96], 97]. Nrf-2 and HO-1 play crucial roles in diabetes management by regulating redox balance, insulin sensitivity, and glucose metabolism [98], 99]. STZ-induced diabetes increases oxidative stress and ROS production, leading to changes in Nrf-2 and HO-1 expression [100]. Nrf-2 activates the transcription of antioxidant genes, including HO-1, which has cytoprotective effects through heme degradation [101]. The Nrf2/HO-1 pathway is vital for cellular defense against oxidative stress, promoting cell survival and mitigating apoptosis [102]. The H. sabdariffa extract, like metformin, significantly (p < 0.05) upregulated Nrf-2 and HO-1 expressions, enhancing redox balance and glucose metabolism in diabetic rats [103], 104].

Histopathological examination revealed significant liver damage in untreated diabetic rats, including pyknotic hepatocyte nuclei, dilated blood vessels, hepatocyte vacuolation, and necrosis, reflecting STZ-induced diabetic damage [105], 106]. Inflammation and fibrosis, along with vascular alterations and amyloid deposits, were also observed [107], 108]. These changes underscore the pathophysiology of diabetes and its complications. Treatment with H. sabdariffa extract appeared to reverse these hepatic alterations, suggesting potential for partial recovery and corroborating previous research [109], 110].

In general, all results indicate that the flavonoid-rich extract of H. sabdariffa is not only effective in mitigating oxidative stress and liver dysfunction in STZ-induced diabetic rats, but also demonstrates a favourable safety profile. Various biomarkers showed no signs of toxicity associated with the extract. The data reflect a dose-dependent attenuation of diabetes-related abnormalities without adverse effects. All this suggests that H. sabdariffa may be a promising therapeutic candidate for the management of diabetes and associated liver complications, and that it merits further clinical investigation of its safety and efficacy in humans.

5 Conclusions

In conclusion, this study investigated the therapeutic potential of H. sabdariffa leaf extract, rich in flavonoids, in STZ-induced diabetic rats, focusing on its effects on oxidative stress, liver function, and the expression of Nrf-2 and HO-1 genes. The findings demonstrated that the extract effectively reduced oxidative stress, as shown by lower levels of protein carbonyls and fragmented DNA, similar to the effects of MET. The Nrf-2 and HO-1 genes were crucial in mediating these antioxidant and cytoprotective responses.

Additionally, the extract restored enzymatic balance, corrected phosphatase irregularities, and exhibited hepatoprotective potential by improving transaminase and albumin levels. It also modulated gene expression by upregulating Nrf-2 and HO-1, enhancing antioxidant defenses, and contributing to histopathological improvements in the liver.

This research underlines the potential of H. sabdariffa in the management of diabetes-related complications and suggests the need for further clinical studies to explore its possible applications in both diabetes and liver disorders.

Although no significant limitations have been observed at this stage, it is important to consider that potential issues may arise as the study progresses. For example, factors such as sample size and study duration should be carefully evaluated, as they could influence the generalizability of the results. Therefore, future research should focus on validating these findings through larger-scale clinical trials, which could provide further evidence and clarify the practical implications of the current discoveries.

-

Research ethics: All experimental protocols in this study were approved by FUOYE Faculty of Science Ethics Committee with ethics number FUOYEFSC 201122-REC2022/008).

-

Informed consent: Not applicable.

-

Author contributions: All authors have accepted responsibility for the entire content of this manuscript and approved its submission. Conceptualization, BOA, BEO and OAO; methodology, CDF, DIO, BPJ, ZOA, MI, SV and AFIA; formal analysis, BOA, BEO, CDF, DIO, BPJ, ZOA, MI and BICB; investigation, CDF, DIO, BPJ, ZOA, MI, SV and OAO; writing – original draft preparation, CDF, DIO, BPJ, ZOA, AFIA and OAO writing – review and editing, BOA, BEO, HH, BICB, SV and MI; supervision, MI.

-

Use of Large Language Models, AI and Machine Learning Tools: None declared.

-

Conflict of interest: The authors state no conflict of interest.

-

Research funding: None declared.

-

Data availability: The raw data can be obtained on request from the corresponding author.

References

1. DeFronzo, RA, Ferrannini, E, Groop, L, Henry, RR, Herman, WH, Holst, JJ, et al.. Type 2 diabetes mellitus. Nat Rev Dis Prim 2015;1:1–22. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrdp.2015.19.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

2. Papatheodorou, K, Banach, M, Bekiari, E, Rizzo, M, Edmonds, M. Complications of diabetes 2017. J Diabetes Res 2018;2018:3086167. https://doi.org/10.1155/2018/3086167.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

3. Magliano, DJ, Zimmet, P, Shaw, JE. Classification of diabetes mellitus and other categories of glucose intolerance. International textbook of diabetes mellitus. England: John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.; 2015:1–16 pp.10.1002/9781118387658.ch1Search in Google Scholar

4. Rojas, J, Bermudez, V, Palmar, J, Martínez, MS, Olivar, LC, Nava, M, et al.. Pancreatic beta cell death: novel potential mechanisms in diabetes therapy. J Diabetes Res 2018;2018:9601801. https://doi.org/10.1155/2018/9601801.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

5. Halim, M, Halim, A. The effects of inflammation, aging and oxidative stress on the pathogenesis of diabetes mellitus (type 2 diabetes). Diabetes Metab Syndr Clin Res Rev 2019;13:1165–72. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dsx.2019.01.040.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

6. Oguntibeju, OO. Type 2 diabetes mellitus, oxidative stress and inflammation: examining the links. Int J Physiol Pathophysiol Pharmacol 2019;11:45–63.Search in Google Scholar

7. Luna, R, Manjunatha, RT, Bollu, B, Jhaveri, S, Avanthika, C, Reddy, N, et al.. A comprehensive review of neuronal changes in diabetics. Cureus 2021;13. https://doi.org/10.7759/cureus.19142.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

8. Kumar, V, Xin, X, Ma, J, Tan, C, Osna, N, Mahato, RI. Therapeutic targets, novel drugs, and delivery systems for diabetes associated NAFLD and liver fibrosis. Adv Drug Deliv Rev 2021;176:113888. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addr.2021.113888.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

9. Huang, HZ, Qiu, M, Lin, JZ, Li, MQ, Ma, XT, Ran, F, et al.. Potential effect of tropical fruits Phyllanthus emblica L. for the prevention and management of type 2 diabetic complications: a systematic review of recent advances. Eur J Nutr 2021;60:3525–42. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00394-020-02471-2.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

10. Conde de la Rosa, L, Goicoechea, L, Torres, S, Garcia-Ruiz, C, Fernandez-Checa, JC. Role of oxidative stress in liver disorders. Liver 2022;2:283–314. https://doi.org/10.3390/livers2040023.Search in Google Scholar

11. Bedi, O, Aggarwal, S, Trehanpati, N, Ramakrishna, G, Krishan, P. Molecular and pathological events involved in the pathogenesis of diabetes-associated nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. J Clin Exp Hepatol 2019;9:607–18. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jceh.2018.10.004.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

12. Misra, HP, Fridovich, I. The purification and properties of superoxide dismutase from Neurospora crassa. J Biol Chem 1972;247:3410–4. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0021-9258(19)45155-7.Search in Google Scholar

13. Bule, M, Albelbeisi, AH, Nikfar, S, Amini, M, Abdollahi, M. The antidiabetic and antilipidemic effects of Hibiscus sabdariffa: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials. Food Res Int 2020;130:108980. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodres.2020.108980.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

14. Benoite, T, Vigasini, N. Antioxidant and antidiabetic activities of ethanolic extract of Hibiscus sabdariffa calyx and Stevia rebaudiana leaf. Asian J Biol Life Sci 2021;10:217–24.10.5530/ajbls.2021.10.31Search in Google Scholar

15. Bellezza, I, Giambanco, I, Minelli, A, Donato, R. Nrf2-Keap1 signaling in oxidative and reductive stress. Biochim Biophys Acta Mol Cell Res 2018;1865:721–33. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbamcr.2018.02.010.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

16. Zhang, JF, Bai, KW, Su, WP, Wang, AA, Zhang, LL, Huang, KH, et al.. Curcumin attenuates heat-stress-induced oxidant damage by simultaneous activation of GSH-related antioxidant enzymes and Nrf2-mediated phase II detoxifying enzyme systems in broiler chickens. Poultry Sci 2018;97:1209–19. https://doi.org/10.3382/ps/pex408.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

17. Gupta, A, Behl, T, Sehgal, A, Bhatia, S, Jaglan, D, Bungau, S. Therapeutic potential of Nrf-2 pathway in the treatment of diabetic neuropathy and nephropathy. Mol Biol Rep 2021;8:2761–74. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11033-021-06257-5.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

18. Wong, SY, Tan, MG, Wong, PT, Herr, DR, Lai, MK. Andrographolide induces Nrf2 and heme oxygenase 1 in astrocytes by activating p38 MAPK and ERK. J Neuroinflamm 2016;13:1–12. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12974-016-0723-3.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

19. Wang, FJ, Wang, SX, Chai, LJ, Zhang, Y, Guo, H, Hu, LM. Xueshuantong injection (lyophilized) combined with salvianolate lyophilized injection protects against focal cerebral ischemia/reperfusion injury in rats through attenuation of oxidative stress. Acta Pharmacol Sin 2018;39:998–1011. https://doi.org/10.1038/aps.2017.128.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

20. Vriend, J, Reiter, RJ. The Keap1-Nrf2-antioxidant response element pathway: a review of its regulation by melatonin and the proteasome. Mol Cell Endocrinol 2015;401:213–20. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mce.2014.12.013.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

21. Suzuki, T, Muramatsu, A, Saito, R, Iso, T, Shibata, T, Kuwata, K, et al.. Molecular mechanism of cellular oxidative stress sensing by Keap1. Cell Rep 2019;28:746–58. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.celrep.2019.06.047.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

22. Chen, L, Teng, H, Jia, Z, Battino, M, Miron, A, Yu, Z, et al.. Intracellular signaling pathways of inflammation modulated by dietary flavonoids: the most recent evidence. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr 2018;58:2908–24. https://doi.org/10.1080/10408398.2017.1345853.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

23. Amos, A, Khiatah, B. Mechanisms of action of nutritionally rich Hibiscus sabdariffa’s therapeutic uses in major common chronic diseases: a literature review. J Am Diet Assoc 2022;41:116–24. https://doi.org/10.1080/07315724.2020.1848662.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

24. Chang, TT, Chen, YA, Li, SY, Chen, JW. Nrf-2 mediated heme oxygenase-1 activation contributes to the anti-inflammatory and renal protective effects of Ginkgo biloba extract in diabetic nephropathy. J Ethnopharmacol 2021;266:113474. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jep.2020.113474.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

25. Abdel-Gaber, SA, Geddawy, A, Moussa, RA. The hepatoprotective effect of sitagliptin against hepatic ischemia reperfusion-induced injury in rats involves Nrf-2/HO-1 pathway. Pharmacol Rep 2019;71:1044–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pharep.2019.06.006.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

26. Hassan, M, Ibrahi, MA, Hafez, HM, Mohamed, MZ, Zenhom, NM, Abd Elghany, HM. Role of Nrf2/HO-1 and PI3K/Akt genes in the hepatoprotective effect of cilostazol. Curr Clin Pharmacol 2019;14:61–7. https://doi.org/10.2174/1574884713666180903163558.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

27. Salau, VF, Erukainure, OL, Ijomone, OM, Islam, MS. Caffeic acid regulates glucose homeostasis and inhibits purinergic and cholinergic activities while abating oxidative stress and dyslipidaemia in fructose-streptozotocin-induced diabetic rats. J Pharm Pharmacol 2002;74:973–84. https://doi.org/10.1093/jpp/rgac021.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

28. Ajiboye, TO, Raji, HO, Adeleye, AO, Adigun, NS, Giwa, OB, Ojewuyi, OB, et al.. Hibiscus sabdariffa calyx palliates insulin resistance, hyperglycemia, dyslipidemia and oxidative rout in fructose-induced metabolic syndrome rats. J Sci Food Agric 2016;96:1522–31. https://doi.org/10.1002/jsfa.7254.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

29. Ajiboye, BO, Famusiwa, CD, Nifemi, DM, Ayodele, BM, Akinlolu, OS, Fatoki, TH, et al.. Nephroprotective effect of Hibiscus Sabdariffa leaf flavonoid extracts via KIM-1 and TGF-1β signaling pathways in streptozotocin-induced rats. ACS Omega 2024;9:19334–44. https://doi.org/10.1021/acsomega.4c00254.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

30. Ajiboye, BO, Famusiwa, CD, Falode, JA, Ojelabi, AO, Mistura, AN, Ogunbiyi, DO, et al.. Ocimum gratissimum L. leaf flavonoid-rich extracts reduced the expression of p53 and VCAM in streptozotocin-induced cardiomyopathy rats. Phytomed Plus 2024;4:100548. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.phyplu.2024.100548.Search in Google Scholar

31. Wolozin, B, Iwasaki, K, Vito, P, Ganjei, JK, Lacanà, E, Sunderland, T, et al.. Participation of presenilin 2 in apoptosis: enhanced basal activity conferred by an Alzheimer mutation. Science 1996;274:1710–3. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.274.5293.1710.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

32. Levine, RL, Garland, D, Oliver, CN, Amici, A, Climent, I, Lenz, AG, et al.. Determination of carbonyl content in oxidatively modified proteins. Methods Enzymol 1990;186:464–78. https://doi.org/10.1016/0076-6879(90)86141-h.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

33. Oloyede, HOB, Abdulkareem, HO, Salawu, MO, Ajiboye, TO. Protective potentials of Vernonia amygdalina leaf extracts on cadmium induced hepatic damage. Al-Hikmah J Pure Appl Sci 2019;7:9–21.Search in Google Scholar

34. Habig, WH, Pabst, MJ, Fleischner, G, Gatmaitan, Z, Arias, IM, Jakoby, WB. The identity of glutathione S-transferase B with ligandin, a major binding protein of liver. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1974;71:3879–82. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.71.10.3879.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

35. Beers, RF, Sizer, IW. A spectrophotometric method for measuring the breakdown of hydrogen peroxide by catalase. J Biol Chem 1952;195:133–40. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0021-9258(19)50881-x.Search in Google Scholar

36. Haque, R, Bin-Hafeez, B, Parvez, S, Pandey, S, Sayeed, I, Ali, M, et al.. Aqueous extract of walnut (Juglans regia L.) protects mice against cyclophosphamideinduced biochemical toxicity. Hum Exp Toxicol 2003;22:473–80. https://doi.org/10.1191/0960327103ht388oa.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

37. Ellman, GL. Tissue sulfhydryl groups. Arch Biochem Biophys 1959;82:70–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/0003-9861(59)90090-6.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

38. Elekofehinti, OO, Ayodele, OC, Iwaloye, O. Momordica charantia nanoparticles promote mitochondria biogenesis in the pancreas of diabetic-induced rats: gene expression study. Egypt J Med Hum Genet 2021;22:1–11.10.1186/s43042-021-00200-wSearch in Google Scholar

39. Blume, G, Pestronk, A, Frank, B, Johns, DR. Polymyositis with cytochrome oxidase negative muscle fibres. Early quadriceps weakness and poor response to immunosuppressive therapy. Brain;120:39–45. https://doi.org/10.1093/brain/120.1.39.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

40. Tripathi, BK, Srivastava, AK. Diabetes mellitus: complications and therapeutics. Med Sci Mon Int Med J Exp Clin Res 2006;12:130–47.Search in Google Scholar

41. Galicia-Garcia, U, Benito-Vicente, A, Jebari, S, Larrea-Sebal, A, Siddiqi, H, Uribe, KB, et al.. Pathophysiology of type 2 diabetes mellitus. Int J Mol Sci 2020;21:6275. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms21176275.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

42. Raff, EJ, Kakati, D, Bloomer, JR, Shoreibah, M, Rasheed, K, Singal, AK. Diabetes mellitus predicts occurrence of cirrhosis and hepatocellular cancer in alcoholic liver and non-alcoholic fatty liver diseases. J Clin Transl Hepatol 2015;3:9. https://doi.org/10.14218/JCTH.2015.00001.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

43. Mohamed, J, Nafizah, AN, Zariyantey, AH, Budin, S. Mechanisms of diabetes-induced liver damage: the role of oxidative stress and inflammation. Sultan Qaboos Univ Med J 2016;16:e132. https://doi.org/10.18295/squmj.2016.16.02.002.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

44. Cichoż-Lach, H, Michalak, A. Oxidative stress as a crucial factor in liver diseases. World J Gastroenterol 2014;20:8082–91. https://doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v20.i25.8082.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

45. Hatting, M, Tavares, CD, Sharabi, K, Rines, AK, Puigserver, P. Insulin regulation of gluconeogenesis. Ann N Y Acad Sci 2018;1411:21–35. https://doi.org/10.1111/nyas.13435.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

46. Bae, CS, Lee, Y, Ahn, T. Therapeutic treatments for diabetes mellitus-induced liver injury by regulating oxidative stress and inflammation. Appl Microsc 2023;53:4. https://doi.org/10.1186/s42649-023-00089-2.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

47. Krajka-Kuźniak, V, Paluszczak, J, Baer-Dubowska, W. The Nrf2-ARE signaling pathway: an update on its regulation and possible role in cancer prevention and treatment. Pharmacol Rep 2017;69:393–402. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pharep.2016.12.011.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

48. Zimta, AA, Cenariu, D, Irimie, A, Magdo, L, Nabavi, SM, Atanasov, AG, et al.. The role of Nrf2 activity in cancer development and progression. Cancers 2019;11:1755. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers11111755.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

49. Bardallo, R, Panisello-Roselló, A, Sanchez-Nuno, S, Alva, N, Roselló-Catafau, J, Carbonell, T. Nrf2 and oxidative stress in liver ischemia/reperfusion injury. FEBS J 2022;289:5463–79.10.1111/febs.16336Search in Google Scholar PubMed

50. Ashrafizadeh, M, Ahmadi, Z, Mohammadinejad, R, Farkhondeh, T, Samarghandian, S. Curcumin activates the Nrf2 pathway and induces cellular protection against oxidative injury. Curr Mol Med 2020;20:116–33. https://doi.org/10.2174/1566524019666191016150757.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

51. Alshehri, AS, El-Kott, AF, El-Gerbed, MS, El-Kenawy, AE, Albadrani, GM, Khalifa, HS. Kaempferol prevents cadmium chloride-induced liver damage by upregulating Nrf2 and suppressing NF-κB and keap1. Environ Sci Pollut Res 2022;29:13917–29. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11356-021-16711-3.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

52. Hejazian, SM, Khatibi, SMH, Barzegari, A, Pavon-Djavid, G, Soofiyani, SR, Hassannejhad, S, et al.. Nrf-2 as a therapeutic target in acute kidney injury. Life Sci 2021;264:118581. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lfs.2020.118581.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

53. Abdullah, KM, Abul Qais, F, Hasan, H, Naseem, I. Anti-diabetic study of vitamin B6 on hyperglycaemia induced protein carbonylation, DNA damage and ROS production in alloxan induced diabetic rats. Toxicol Res 2019;8:568–79. https://doi.org/10.1039/c9tx00089e.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

54. Almatroodi, SA, Alnuqaydan, AM, Alsahli, MA, Khan, AA, Rahmani, AH. Thymoquinone, the most prominent constituent of Nigella sativa, attenuates liver damage in streptozotocin-induced diabetic rats via regulation of oxidative stress, inflammation and cyclooxygenase-2 protein expression. Appl Sci 2021;11:3223. https://doi.org/10.3390/app11073223.Search in Google Scholar

55. Marques, PE, Oliveira, AG, Pereira, RV, David, BA, Gomides, LF, Saraiva, AM, et al.. Hepatic DNA deposition drives drug-induced liver injury and inflammation in mice. Hepatology 2015;61:348–60. https://doi.org/10.1002/hep.27216.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

56. Sadasivam, N, Kim, YJ, Radhakrishnan, K, Kim, DK. Oxidative stress, genomic integrity, and liver diseases. Molecules 2022;27:3159. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules27103159.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

57. Farid, MM, Aboul, NAF, Salem, MM, Ahmed, YR, Emam, M, Hamed, MA. Chemical compositions of Commiphora opobalsamum stem bark to alleviate liver complications in streptozotocin-induced diabetes in rats: role of oxidative stress and DNA damage. Biomarkers 2022;27:671–83.10.1080/1354750X.2022.2099015Search in Google Scholar PubMed

58. Zhang, X, Wu, X, Hu, Q, Wu, J, Wang, G, Hong, Z, et al.. Mitochondrial DNA in liver inflammation and oxidative stress. Life Sci 2019;236:116464. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lfs.2019.05.020.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

59. Géhl, Z, Bakondi, E, Resch, MD, Hegedűs, C, Kovács, K, Lakatos, P, et al.. Diabetes-induced oxidative stress in the vitreous humor. Redox Biol 2016;9:100–3. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.redox.2016.07.003.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

60. Hecker, M, Wagner, AH. Role of protein carbonylation in diabetes. J Inherit Metab Dis 2018;41:29–38. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10545-017-0104-9.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

61. Luceri, C, Bigagli, E, Femia, AP, Caderni, G, Giovannelli, L, Lodovici, M. Aging related changes in circulating reactive oxygen species (ROS) and protein carbonyls are indicative of liver oxidative injury. Toxicol Rep 2018;5:141–5. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.toxrep.2017.12.017.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

62. Bhatti, JS, Sehrawat, A, Mishra, J, Sidhu, IS, Navik, U, Khullar, N, et al.. Oxidative stress in the pathophysiology of type 2 diabetes and related complications: current therapeutics strategies and future perspectives. Free Radic Biol Med 2022;184:114–34. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2022.03.019.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

63. Ayepola, OR, Brooks, NL, Oguntibeju, OO. Oxidative stress and diabetic complications: the role of antioxidant vitamins and flavonoids. In: Oguntibeju, O, editor. Antioxidant-antidiabetic agents and human health. London: IntechOpen; 2014:923–31 pp.Search in Google Scholar

64. Zainalabidin, S, Budin, SB, Anuar, NNM, Yusoff, NA, Yusof, NLM. Hibiscus sabdariffa Linn. improves the aortic damage in diabetic rats by acting as antioxidant. J Appl Pharm Sci 2018;8:108–14.Search in Google Scholar

65. Vuppalapati, L, Velayudam, R, Ahamed, KN, Cherukuri, S, Kesavan, BR. The protective effect of dietary flavonoid fraction from Acanthophora spicifera on streptozotocin induced oxidative stress in diabetic rats. Food Sci Hum Wellness 2016;5:57–64.10.1016/j.fshw.2016.02.002Search in Google Scholar

66. Rao, PS, Mohan, GK. In vitro alpha-amylase inhibition and in vivo antioxidant potential of Momordica dioica seeds in streptozotocin-induced oxidative stress in diabetic rats. Saudi J Biol Sci 2017;24:1262–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sjbs.2016.01.010.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

67. Das, K, Roychoudhury, A. Reactive oxygen species (ROS) and response of antioxidants as ROS-scavengers during environmental stress in plants. Front Environ Sci 2014;2:53. https://doi.org/10.3389/fenvs.2014.00053.Search in Google Scholar

68. Sachdev, S, Ansari, SA, Ansari, MI, Fujita, M, Hasanuzzaman, M. Abiotic stress and reactive oxygen species: generation, signaling, and defense mechanisms. Antioxidants 2021;10:277. https://doi.org/10.3390/antiox10020277.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

69. Kanwar, MK, Xie, D, Yang, C, Ahammed, GJ, Qi, Z, Hasan, MK, et al.. Melatonin promotes metabolism of bisphenol A by enhancing glutathione-dependent detoxification in Solanum lycopersicum L. J Hazard Mater 2020;388:121727. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhazmat.2019.121727.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

70. Al Nahdi, AM, John, A, Raza, H. Elucidation of molecular mechanisms of streptozotocin-induced oxidative stress, apoptosis, and mitochondrial dysfunction in Rin-5F pancreatic β-cells. Oxid Med Cell Longev 2017;2017:7054272. https://doi.org/10.1155/2017/7054272.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

71. Ighodaro, OM, Akinloye, OA. First line defence antioxidants-superoxide dismutase (SOD), catalase (CAT) and glutathione peroxidase (GPX): their fundamental role in the entire antioxidant defence grid. Alexandria J Med 2018;54:287–93. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajme.2017.09.001.Search in Google Scholar

72. Seedevi, P, Ramu Ganesan, A, Moovendhan, M, Mohan, K, Sivasankar, P, Loganathan, S, et al.. Anti-diabetic activity of crude polysaccharide and rhamnose-enriched polysaccharide from G. lithophila on Streptozotocin (STZ)-induced in Wistar rats. Sci Rep 2020;10:556. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-57486-w.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

73. Liu, H, Li, N, Jin, M, Miao, X, Zhang, X, Zhong, W. Magnesium supplementation enhances insulin sensitivity and decreases insulin resistance in diabetic rats. Iran J Basic Med Sci 2020;23:990. https://doi.org/10.22038/ijbms.2020.40859.9650.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

74. Rochette, L, Zeller, M, Cottin, Y, Vergely, C. Diabetes, oxidative stress and therapeutic strategies. Biochim Biophys Acta-General Subjects 2014;1840:2709–29. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbagen.2014.05.017.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

75. Sharma, A, Gupta, P, Prabhakar, PK. Endogenous repair system of oxidative damage of DNA. Curr Chem Biol 2019;13:110–9. https://doi.org/10.2174/2212796813666190221152908.Search in Google Scholar

76. Ammendolia, DA, Bement, WM, Brumell, JH. Plasma membrane integrity: implications for health and disease. BMC Biol 2021;19:1–29. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12915-021-00972-y.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

77. Adeyemi, DO, Adewole, OS. Hibiscus sabdariffa renews pancreatic β-cells in experimental type 1 diabetic model rats. Morphologie 2019;103:80–93. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.morpho.2019.04.003.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

78. Mandal, A, Das, V, Ghosh, P, Ghosh, S. Anti-diabetic effect of FriedelanTriterpenoids in streptozotocin induced diabetic rat. Nat Prod Commun 2015;10:1683–6. https://doi.org/10.1177/1934578x1501001013.Search in Google Scholar

79. Khajuria, P, Raghuwanshi, P, Rastogi, A, Koul, AL, Zargar, R, Kour, S. Hepatoprotective effect of Seabuckthorn leaf extract in streptozotocin induced diabetes mellitus in Wistar rats. Indian J Anim Res 2018;52:1745–50. https://doi.org/10.18805/ijar.b-3439.Search in Google Scholar

80. Poupon, R. Liver alkaline phosphatase: a missing link between choleresis and biliary inflammation. Hepatology 2015;61:2080–90. https://doi.org/10.1002/hep.27715.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

81. Kalas, MA, Chavez, L, Leon, M, Taweesedt, PT, Surani, S. Abnormal liver enzymes: a review for clinicians. World J Hepatol 2021;13:1688. https://doi.org/10.4254/wjh.v13.i11.1688.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

82. Levitsky, A, Selivanskaya, I, Tishchenko, T, Stupak, O. Mineralizing activity of periodontal bone tissue of rats with experimental diabetes. J Educ Health Sport 2023;42:115–23. https://doi.org/10.12775/jehs.2023.42.01.010.Search in Google Scholar

83. Safhi, MM, Alam, MF, Sivakumar, SM, Anwer, T. Hepatoprotective potential of Sargassum muticum against STZ-induced diabetic liver damage in wistar rats by inhibiting cytokines and the apoptosis pathway. Anal Cell Pathol 2019;2019:1–8. https://doi.org/10.1155/2019/7958701.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

84. Yadav, Y, Dey, CS. Ser/Thr phosphatases: one of the key regulators of insulin signaling. Rev Endocr Metab Disord 2022:23905–17. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11154-022-09727-8.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

85. Shopit, A, Niu, M, Wang, H, Tang, Z, Li, X, Tesfaldet, T, et al.. Protection of diabetes-induced kidney injury by phosphocreatine via the regulation of ERK/Nrf2/HO-1 signaling pathway. Life Sci 2020;242:117248. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lfs.2019.117248.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

86. Oboh, G, Adewuni, TM, Ademiluyi, AO, Olasehinde, TA, Ademosun, AO. Phenolic constituents and inhibitory effects of Hibiscus sabdariffa L.(Sorrel) calyx on cholinergic, monoaminergic, and purinergic enzyme activities. J Diet Suppl 2018;15:910–22. https://doi.org/10.1080/19390211.2017.1406426.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

87. Banwo, K, Sanni, A, Sarkar, D, Ale, O, Shetty, K. Phenolics-linked antioxidant and anti-hyperglycemic properties of edible Roselle (Hibiscus sabdariffa Linn.) calyces targeting type 2 diabetes nutraceutical benefits in vitro. Front Sustain Food Syst 2022;6:1–13. https://doi.org/10.3389/fsufs.2022.660831.Search in Google Scholar

88. Sobeh, M, Mahmoud, MF, Abdelfattah, MA, El-Beshbishy, HA, El-Shazly, AM, Wink, M. Hepatoprotective and hypoglycemic effects of a tannin rich extract from Ximenia americana var. caffra root. Phytomedicine 3017;33:36–42. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.phymed.2017.07.003.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

89. Stepien, M, Fedirko, V, Duarte-Salles, T, Ferrari, P, Freisling, H, Trepo, E, et al.. Prospective association of liver function biomarkers with development of hepatobiliary cancers. Cancer Epidemiol 2016;40:179–87. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.canep.2016.01.002.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

90. Bullón-Vela, MV, Abete, I, Martínez, JA, Zulet, MA. Obesity and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: role of oxidative stress. In: Jensen, M, editor. Obesity. England: John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.; 2018:111–33 pp.10.1016/B978-0-12-812504-5.00006-4Search in Google Scholar

91. Monserrat-Mesquida, M, Quetglas-Llabrés, M, Abbate, M, Montemayor, S, Mascaró, CM, Casares, M, et al.. Oxidative stress and pro-inflammatory status in patients with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Antioxidants 2020;9:759. https://doi.org/10.3390/antiox9080759.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

92. Agustanti, N, Djumhana, A, Abdurachman, SA, Soetodjo, NMN. Correlation between serum albumin and fasting blood glucose level in patients with liver cirrhosis. Indones J Gastroenterol Hepatol Dig Endosc 2014;15:143–6. https://doi.org/10.24871/1532014143-146.Search in Google Scholar

93. Soeters, PB, Wolfe, RR, Shenkin, A. Hypoalbuminemia: pathogenesis and clinical significance. J Parenter Enteral Nutr 2019;43:181–93. https://doi.org/10.1002/jpen.1451.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

94. Obouayeba, AP, Boyvin, L, M’Boh, GM, Diabaté, S, Kouakou, TH, Djaman, AJ, et al.. Hepatoprotective and antioxidant activities of Hibiscus sabdariffa petal extracts in Wistar rats. Int J Basic Clin Pharmacol 2014;3:774–80. https://doi.org/10.5455/2319-2003.ijbcp20141034.Search in Google Scholar

95. Jomeh, R, Chitsaz, H, Akrami, R. Effect of anthocyanin extract from Roselle, Hibiscus sabdariffa, calyx on haematological, biochemical and immunological parameters of rainbow trout, Oncorhynchus mykiss. Aquacult Res 2021;52:3736–44. https://doi.org/10.1111/are.15218.Search in Google Scholar

96. Yang, ZJ, Wang, HR, Wang, YI, Zhai, ZH, Wang, LW, Li, L, et al.. Myricetin attenuated diabetes-associated kidney injuries and dysfunction via regulating nuclear factor (erythroid derived 2)-like 2 and nuclear factor-κB signaling. Front Pharmacol 2019;10:647. https://doi.org/10.3389/fphar.2019.00647.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

97. Antar, SA, Abdo, W, Taha, RS, Farage, AE, El-Moselhy, LE, Amer, ME, et al.. Telmisartan attenuates diabetic nephropathy by mitigating oxidative stress and inflammation, and upregulating Nrf2/HO-1 signaling in diabetic rats. Life Sci 2020;291:120260. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lfs.2021.120260.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

98. Taneera, J, Fadista, J, Ahlqvist, E, Atac, D, Ottosson-Laakso, E, Wollheim, CB, et al.. Identification of novel genes for glucose metabolism based upon expression pattern in human islets and effect on insulin secretion and glycemia. Hum Mol Genet 2015;24:1945–55. https://doi.org/10.1093/hmg/ddu610.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

99. Chang, Y, Dong, M, Wang, Y, Yu, H, Sun, C, Jiang, X, et al.. GLP-1 gene-modified human umbilical cord mesenchymal stem cell line improves blood glucose level in type 2 diabetic mice. Stem Cell Int 2019;2019:4961865. https://doi.org/10.1155/2019/4961865.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

100. Fang, S, Cai, Y, Li, P, Wu, C, Zou, S, Zhang, Y, et al.. Exendin-4 alleviates oxidative stress and liver fibrosis by activating Nrf2/HO-1 in streptozotocin-induced diabetic mice. Sout Med J 2019;39:464–70. https://doi.org/10.12122/j.issn.1673-4254.2019.04.13.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

101. Otterbein, LE, Foresti, R, Motterlini, R. Heme oxygenase-1 and carbon monoxide in the heart: the balancing act between danger signaling and pro-survival. Circ Res 2016;118:1940–59. https://doi.org/10.1161/circresaha.116.306588.Search in Google Scholar

102. Huang, Y, Li, J, Li, W, Ai, N, Jin, H. Biliverdin/bilirubin redox pair protects lens epithelial cells against oxidative stress in age-related cataract by regulating NF-κB/iNOS and Nrf2/HO-1 pathways. Oxid Med Cell Longev 2022;2022:7299182. https://doi.org/10.1155/2022/7299182.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

103. Janson, B, Prasomthong, J, Malakul, W, Boonsong, T, Tunsophon, S. Hibiscus sabdariffa L. calyx extract prevents the adipogenesis of 3T3-L1 adipocytes, and obesity-related insulin resistance in high-fat diet-induced obese rats. Biomed Pharmacother 2021;138:111438. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biopha.2021.111438.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

104. Malar, DS, Prasanth, MI, Brimson, JM, Verma, K, Prasansuklab, A, Tencomnao, T. Hibiscus sabdariffa extract protects HT-22 cells from glutamate-induced neurodegeneration by upregulating glutamate transporters and exerts lifespan extension in C. elegans via DAF-16 mediated pathway. Nutr Healthy Aging 2021;6:229–47. https://doi.org/10.3233/nha-210131.Search in Google Scholar

105. Bilal, HM, Riaz, F, Munir, K, Saqib, A, Sarwar, MR. Histological changes in the liver of diabetic rats: a review of pathogenesis of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease in type 1 diabetes mellitus. Cogent Med 2016;3:1275415. https://doi.org/10.1080/2331205x.2016.1275415.Search in Google Scholar

106. Elamin, NMH, Fadlalla, IMT, Omer, SA, Ibrahim, HAM. Histopathological alteration in STZ-nicotinamide diabetic rats, a complication of diabetes or a toxicity of STZ. Int J Diabetes Clin Res 2018;5:1–8. https://doi.org/10.23937/2377-3634/1410091.Search in Google Scholar

107. Shahid, M, Subhan, F. Protective effect of Bacopa monniera methanol extract against carbon tetrachloride induced hepatotoxicity and nephrotoxicity. Pharmacologyonline 2014;2:18–28.Search in Google Scholar

108. Kumbhare, V, Gajbe, U, Singh, BR, Reddy, AK, Shukla, S. Histological & histochemical changes in liver of adult rats treated with monosodium glutamate: a light microscopic study. World J Pharm Pharmaceut Sci 2015;4:898–911.10.5958/2319-5886.2015.00001.6Search in Google Scholar

109. Adeyemi, DO, Ukwenya, VO, Obuotor, EM, Adewole, SO. Anti-hepatotoxic activities of Hibiscus sabdariffa L. in animal model of streptozotocin diabetes-induced liver damage. BMC Compl Alternative Med 2014;14:1–11. https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6882-14-277.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

110. Orji, BO, Modo, EU, Obi, FO. Post-treatment with Hibiscus sabdariffa Linn calyx extract enhances liver function following chronic paracetamol exposure in mice. J Phytomed Ther 2022;20:656–69.Search in Google Scholar

© 2024 the author(s), published by De Gruyter, Berlin/Boston

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Review Articles

- Ethnopharmacology and current conservational status of Cordyceps sinensis

- Review perspective on advanced nutrachemicals and anterior cruciate ligament rehabilitation

- Research Articles

- Cytotoxic compounds from Viscum coloratum (Kom.) Nakai

- Effect of Hibiscus sabdariffa L. leaf flavonoid-rich extract on Nrf-2 and HO-1 pathways in liver damage of streptozotocin-induced diabetic rats

- Inhibition of pro-inflammatory cytokines by homalolide A and homalomenol A isolated from rhizomes of Homalomena pendula

- Synthesis, in vitro anti-urease, in-silico molecular docking study and ADMET predictions of piperidine and piperazine Morita-Baylis-Hillman Adducts (MBHAs)

- Molecular modeling and synthesis of novel benzimidazole-derived thiazolidinone bearing chalcone derivatives: a promising approach to develop potential anti-diabetic agents

- Determination of essential oil and phenolic compounds of Berberis vulgaris grown in Şavşat, Artvin; revealing its antioxidant and antimicrobial activities

- Essential oil of Daucus carota (L.) ssp. carota (Apiaceae) flower: chemical composition, antimicrobial potential, and insecticidal activity on Sitophilus oryzae (L.)

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Review Articles

- Ethnopharmacology and current conservational status of Cordyceps sinensis

- Review perspective on advanced nutrachemicals and anterior cruciate ligament rehabilitation

- Research Articles

- Cytotoxic compounds from Viscum coloratum (Kom.) Nakai

- Effect of Hibiscus sabdariffa L. leaf flavonoid-rich extract on Nrf-2 and HO-1 pathways in liver damage of streptozotocin-induced diabetic rats

- Inhibition of pro-inflammatory cytokines by homalolide A and homalomenol A isolated from rhizomes of Homalomena pendula

- Synthesis, in vitro anti-urease, in-silico molecular docking study and ADMET predictions of piperidine and piperazine Morita-Baylis-Hillman Adducts (MBHAs)

- Molecular modeling and synthesis of novel benzimidazole-derived thiazolidinone bearing chalcone derivatives: a promising approach to develop potential anti-diabetic agents

- Determination of essential oil and phenolic compounds of Berberis vulgaris grown in Şavşat, Artvin; revealing its antioxidant and antimicrobial activities

- Essential oil of Daucus carota (L.) ssp. carota (Apiaceae) flower: chemical composition, antimicrobial potential, and insecticidal activity on Sitophilus oryzae (L.)