Revolutionizing the probiotic functionality, biochemical activity, antibiotic resistance and specialty genes of Pediococcus acidilactici BCB1H via in-vitro and in-silico approaches

-

Gege Hu

, Tariq Aziz

, Metab Alharbi

Abstract

This study presents a comprehensive genomic exploration, biochemical characterization, and the identification of antibiotic resistance and specialty genes of Pediococcus acidilactici BCB1H strain. The functional characterization, genetic makeup, biological activities, and other considerable parameters have been investigated in this study with a prime focus on antibiotic resistance and specialty gene profiles. The results of this study revealed the unique susceptibility patterns for antibiotic resistance and specialty genes. BCB1H had good in vitro probiotic properties, which survived well in simulated artificial gastrointestinal fluid, and exhibited acid and bile salt resistance. BCB1H didn’t produce hemolysis and had certain antibiotic sensitivity, making it a relatively safe LAB strain. Simultaneously, it had good self-coagulation characteristics and antioxidant activity. The EPS produced by BCB1H also had certain antioxidant activity and hypoglycemic function. Moreover, the genome with a 42.4 % GC content and a size of roughly 1.92 million base pairs was analyzed in the genomic investigations. The genome annotation identified 192 subsystems and 1,895 genes, offering light on the metabolic pathways and functional categories found in BCB1H. The identification of specialty genes linked to the metabolism of carbohydrates, stress response, pathogenicity, and amino acids highlighted the strain’s versatility and possible uses. This study establishes the groundwork for future investigations by highlighting the significance of using multiple strains to investigate genetic diversity and experimental validation of predicted genes. The results provide a roadmap for utilizing P. acidilactici BCB1H’s genetic traits for industrial and medical applications, opening the door to real-world uses in industries including food technology and medicine.

1 Introduction

Pediococcus acidilactici, a lactic acid bacterium, is important in the food and biotechnology industries because to its versatility. P. acidilactici, known for its probiotic properties, aids in the fermentation of a variety of food products, improving flavor and shelf life. Furthermore, its antibacterial properties make it an appealing candidate for food preservation [1]. The bacterium’s capacity to adapt to varied environmental conditions, as well as its strong acid and bile resistance, make it ideal for probiotic uses and imply a possible function in gastrointestinal health. Furthermore, P. acidilactici has received attention for its ability to create bioactive substances such exopolysaccharides (EPS) and bacteriocins, which have a variety of positive effects [2]. While P. acidilactici has received attention for its probiotic potential, antibacterial capabilities, and bioactive chemical synthesis, there is still a lack of information of the exact genetic elements and metabolic pathways that control these functions. The project intends to close this gap by using advanced molecular techniques such as DNA extraction, whole genome sequencing, and bioinformatics analyses [1]. The study aims to understand the genetic basis of P. acidilactici BCB1H’s biological activity, antibiotic resistance profiles, and potential for creating important bioactive chemicals. This study fills a critical information gap and establishes the groundwork for a more in-depth understanding of P. acidilactici ’s genetic underpinnings, allowing it to be used in a variety of industrial and therapeutic applications [3].

The present study investigates the genomics of P. acidilactici, a bacterium with important industrial uses, particularly in food technology and probiotics. P. acidilactici is known for its probiotic activity, antibacterial capabilities, and metabolic flexibility. This study focuses on strain BCB1H, with the goal of understanding its genetic makeup and functional properties. We hope to shed light on P. acidilactici BCB1H’s genetic traits, biological activities, antibiotic resistance, and other functional qualities by doing extensive DNA extraction, whole genome sequencing, and subsequent analysis. Understanding the genetic complexities of this strain can provide useful insights into its possible applications and contribute to advances in both biotechnological and medicinal fields.

To conclude, the extensive genomic investigation of P. acidilactici, notably the BCB1H strain, has revealed important information about its genetic makeup and functional properties. The study investigates the bacterium’s antibiotic resistance profiles, biological activities, and ability to produce bioactive substances such as exopolysaccharides (EPS) and bacteriocins. However, future research should concentrate experimental validation of anticipated genes in order to confirm their functions and processes. Furthermore, using additional strains of P. acidilactici in the analysis might help to gain a better knowledge of the species’ genetic diversity and potential [4]. Functional genomics research and in-depth experimental validation will be critical in confirming the projected genes’ roles and mechanisms. The findings of this work pave the door for additional investigation into how the genetic features of P. acidilactici can be used for practical applications in a variety of fields, including food technology and medicine. Continued research in this area shows promise for improving our understanding of this bacterium’s potential contributions to both industrial and medicinal domains [5].

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Bacterial strain identification & culturing

P. acidilactici BCB1H isolated from Chinese sauerkraut was stored at −80 °C in Dairy Laboratory in Beijing Technology and Business University of China. BCB1H was activated in MRS medium (Beijing Aoboxing Co., Ltd., Beijing, China) and cultured at 37 °C for 12 h for two consecutive generations as seed culture medium. The target strain was injected in MRS Medium and grown for 20 h before bacterial DNA extraction was carried out according to the “Bacterial Genomic DNA Extraction Kit” instructions provided by Beijing Tiangen. In a micro centrifuge tube, 0.5–4.0 ml of cells (maximum 2 × 109 cells) were harvested by centrifugation for 1 min at maximum speed, with the supernatant discarded as much as possible. The pellet was resuspended in 100 µl of EL Buffer and stirred thoroughly using a tip. The mixture was then incubated at 37 °C for 40 min, with certain bacteria requiring an additional hour or more [6].

2.2 Biological activities of the strain

2.2.1 Antibacterial activity

The disc diffusion method was used to evaluate antibacterial activity. Escherichia coli, Shigella flexneri, Staphylococcus aureus, Enterobacter stenibacillus, and Listeria monocytogenes were cultured overnight in the appropriate growth media. Sterile filter paper discs were impregnated with the test substance, BCB1H, and placed on the surfaces of agar plates containing the various bacterial strains. The plates were then incubated at 37 °C for 24 h. Following incubation, the diameter of the clear zones of inhibition around each disc was measured with a calibrated ruler. The experiment was conducted in triplicate, and the mean ± standard deviation of inhibition zone widths was computed for each bacterial strain. This provided insight into BCB1H’s antibacterial activity against the tested pathogens [7].

2.2.2 Hemolytic activity

The hemolytic test for the bacterial strain consisted of multiple phases. The hemolytic activity was then determined using a hemolysis assay. Blood agar plates were produced, and the bacterial strain was streaked on them. Following incubation, the plates were inspected for the presence of hemolysis zones surrounding the bacterial colonies. E. coli was used for comparative study. The diameters of these zones were measured, providing information about the strain’s hemolytic capabilities. As a positive control.

2.2.3 Resistance to antibiotics

Antibiotic resistance profiling was performed using the disc diffusion method. Bacterial cultures of BCB1H were spread onto agar plates, and antibiotic discs representing various classes, including β-lactams (penicillin, amoxicillin), macrolides (erythromycin, azithromycin), quinolones (norfloxacin, enrofloxacin), aminoglycosides (amikacin, gentamicin), chloramphenicol, rifampin, lincomycin, and sulfonamides (compound sulfamethoxazole), were placed on the inoculated plates. Following incubation at 37 °C, the widths of the clear zones around each disc were measured to determine antibiotic susceptibility. The interpretative criteria for sensitivity, intermediate sensitivity, and resistance were applied based on established diameter ranges, revealing the BCB1H antibiotic resistance profile to the tested medicines [8].

2.2.4 Acid & bile salt resistance

BCB1H’s acid and bile salt resistance was determined by measuring the optical density at 600 nm (OD600) of live lactic acid bacteria under various conditions. Bacterial cultures were cultivated till mid-log phase, and the initial OD600 was used as a control. The cultures were then treated to different pH levels and bile salt concentrations (0.1 %, 0.2 %, and 0.3 %). The OD600 was measured after each condition to assess BCB1H survival and growth. The experiment was repeated three times, and the average OD600 values were computed for each condition. The obtained results, including the control and fluctuations in OD600 under acid and bile salt stress, were recorded in order to better understand BCB1H’s acid and bile salt resistance profile [9].

2.2.5 Resistance to artificial gastrointestinal fluid

BCB1H resistance to artificial gastrointestinal settings was studied by exposing bacterial cultures to synthetic stomach (pH 3) and intestine (pH 6.8) environments. Viable bacterial counts were originally established, and successive exposures to acidic stomach and less acidic intestine environments were tested. The surviving bacterial populations were quantified after exposure. The triplicate experiment produced mean bacterial counts, which provided insights on BCB1H’s resilience to the different pH levels encountered in the gastrointestinal tract, as well as useful information for prospective probiotic uses [10].

2.2.6 Self-coagulation

The self-coagulation capability of BCB1H was investigated by leaving bacterial cultures undisturbed and observing visible signals of aggregate development over time. Furthermore, optical density measurements were performed to objectively characterize self-coagulation kinetics. The experiment was carried out in triplicate and attempted to define BCB1H’s ability for spontaneous coagulation, providing insights into its possible applications in a variety of industrial and biotechnological settings [11].

2.2.7 Antioxidant activities

Multiple assays were used to extensively examine BCB1H’s antioxidant activity. The 2,2-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl (DPPH) assay measured radical scavenging ability, whereas the hydroxyl radical scavenging assay assessed the ability to neutralize hydroxyl radicals. The 2,2-azino-bis(3-ethylbenzothiazoline-6-sulfonic acid) (ABTS) radical scavenging assay determined its ability to quench ABTS radicals, whereas the superoxide anion radical assay assessed its ability to scavenge superoxide radicals. All assays were carried out in triplicate, resulting in a thorough understanding of BCB1H’s antioxidant capability against diverse reactive oxygen species, which is critical for determining its possible applications in health and biotechnology contexts.

2.3 Biological activity of EPS

2.3.1 Antioxidant activity

Several experiments were used to assess the antioxidant activity of BCB1H-produced Exopolysaccharides (EPS). The EPS produced from BCB1H was isolated and prepared by the method previously reported [10]. The 2,2-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl (DPPH) radical scavenging experiment was used to assess EPS’s ability to neutralize free radicals. Furthermore, the hydroxyl radical scavenging assay evaluated its ability to counteract hydroxyl radicals, while the 2,2′-azino-bis(3-ethylbenzothiazoline-6-sulfonic acid) (ABTS) radical scavenging assay determined its ability to quench ABTS radicals. Furthermore, the superoxide anion radical assay was used to determine EPS’s ability to scavenge superoxide radicals. All experiments were carried out in triplicate, resulting in a thorough understanding of the antioxidant capacity of EPS produced by BCB1H, which is critical for assessing its potential benefits in a variety of biological and industrial applications [10].

2.3.2 Hypoglycemic activity in vitro

The EPS produced from BCB1H was tested for hypoglycemic action in vitro using α-amylase and α-glucosidase inhibition tests. These tests determined the inhibitory effects of EPS on major enzymes involved in glucose metabolism. To determine EPS’s possible hypoglycemic qualities, reactions were carried out in triplicate and quantitative assessments were performed. The results were interpreted and evaluated further [12].

2.4 DNA extraction and whole genome sequencing

The 200 μl GA buffer was mixed thoroughly, then centrifuged at 12,000×g for 1 min. The supernatant was transferred to a fresh 1.5 ml tube, then 400 μl of BA Buffer was added and stirred thoroughly. The mixture was then transferred to the spin column and centrifuged at 10,000×g for 1 min, discarding the flow-through. The spin column was washed further with 500 μl of G Binding Buffer and centrifuged at 10,000×g for 30 s. The flow-through was discarded. This process was repeated once more. The spin column was then centrifuged for an additional minute at 10,000×g before being transferred to a sterile 1.5 ml micro centrifuge tube. After that, 100 μl elution buffer was added and the mixture was incubated at room temperature for 1 min. Following a minute of centrifugation at 12,000×g, the spin column was removed, and the pure DNA was now in the buffer in the micro centrifuge tube. The genomic sequence was submitted to National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov) Genome Database under the specifically allocated accession number of GCF_021568595.1 [13], 14].

2.4.1 Genome drafting & genomic investigations

Genome annotation was performed by Bacterial and Viral Bioinformatics Resource Center PATRIC (BV-BRC) (https://www.bv-brc.org) that was accessed on 04 January 2024 [15]. A rapid annotation of subsystem technology (RAST) (https://rast.nmpdr.org), accessed on 04 January 2024, was utilized for the exploration of various cell and metabolic pathways [16], 17]. The prophage regions in the genome of P. acidilactici BCB1H strain were explored by Phage Search Tool Enhanced Release (PHASTER) (https://phaster.ca) online server that was directly accessed from the URL [18]. For the identification of clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats, CRISPR Finder (https://crisprcas.i2bc.paris-saclay.fr/CrisprCasFinder/Index). For all above mentioned analysis, the genome sequence was submitted in the FASTA format in a single file and the output was analyzed to access the results [19].

2.4.2 Comparative genomics & phylogenetics analysis

The phylogenetic tree of the BCB1H genome was constructed by PATRIC (BV-BRC) (https://www.bv-brc.org) phylogeny tool. The results were obtained by uploading the genome and performing the comprehensive genome analysis. The results were analyzed in the MEGA-X software. The phylogenetic tree was constructed and saved in the newick format for further interpretations [15].

2.4.3 Identification of specialty genes

The comprehensive genome analysis by PATRIC (BV-BRC) (https://www.bv-brc.org) predicted the specialty genes present in the whole genome of BCB1H Genome. Prediction was performed by four different databased and methods and the results suggested the presence of 28 specialty genes according to PATRIC, 8 specialty genes according to TCDB, 1 gene as per the prediction of CARD and 1 from NDARO. The results were further explored to study the present genes and their functionalities as well as their products [15].

2.4.4 Antibiotic resistance genes prediction

To study the antibiotic resistance genes in the BCB1H whole genome, comprehensive antibiotic resistance database (CARD) (http://arpcard.mcmaster.ca) database was utilized that was accessed on 6 January 2024. To conduct the analysis, the genome sequence was uploaded in the FASTA format and the results were obtained that were further interpreted [20].

2.4.5 Bacteriocin production

The prediction of bacteriocin producing genes in the genome of BCB1H was carried out by BAGEL 4 an online server that is freely accessible at (http://bagel4.molgenrug.nl) and was accessed on 7 January 2024. The genomic sequence was submitted in the FASTA format and the results were obtained after some processing. The obtained results were interpreted and analyzed for the identification of bacteriocin producing genes in whole genome under study [21].

2.4.6 Human pathogen detection

In order to pre-assess the safety of the strain under study, the PathogenFinder that is freely available at (https://cge.food.dtu.dk/services/PathogenFinder) and was accessed on 7 January 2024. The FASTA format of genome was submitted to the server and the results output was analyzed and interpreted for the pre-evaluation of the safety for BCB1H strain [22].

2.4.7 Detection of EPS biosynthesis genes

EPS biosynthesis genes were identified utilizing the PROKA (BV-BRC) bioinformatics platform. Gene prediction and annotation were used to discover open reading frames, with a particular emphasis on EPS biosynthesis genes. Functional analysis and validation were used to determine the biological significance of the predicted genes, while comparative genomics offered information about evolutionary links. The findings were interpreted in light of previous research, providing a simple and thorough understanding of EPS production in P. acidilactici [23].

3 Results

3.1 Biological activities of the strain

3.1.1 Antibacterial activity

The mean inhibition zone diameters evaluated after 24 h of incubation at 37 °C revealed different degrees of sensitivity. BCB1H showed inhibitory zone diameters of 14.7 mm for E. coli, 19.6 mm for S. flexneri, 19.4 mm for S. aureus, 19.8 mm for E. stenibacillus, and 14.4 mm for L. monocytogenes. The findings from experiment demonstrate BCB1H’s specific antibacterial activity against the tested bacterial strains that are represented in Table 1 below.

Antibacterial activity of the BCB1H genome.

| Bacterial name | Antibacterial circle diameter/mm | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Escherichia coli | Shigella flexneri | Staphylococcus aureus | Enterobacter stenibacillus | Listeria monocytogenes | |

| BCB1H | 14.7 | 19.6 | 19.4 | 19.8 | 14.4 |

3.1.2 Hemolytic activity

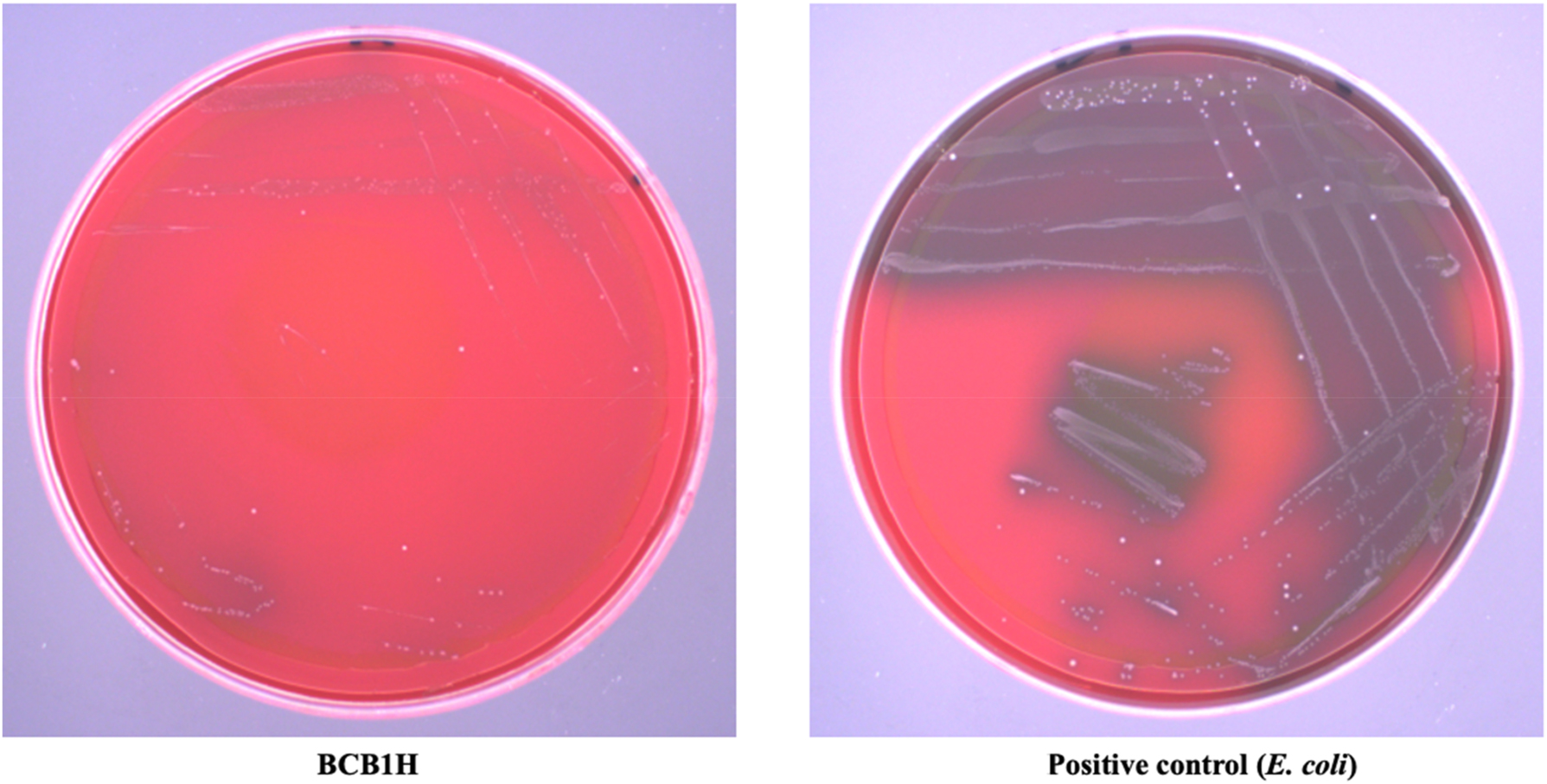

The hemolytic test results are negative, with no visible hemolysis surrounding the bacterial colonies on the blood agar plates. This indicates that the P. acidilactici BCB1H strain lacks hemolytic activity under the experimental conditions. The absence of hemolysis zones, even when compared to E. coli as a positive control, supports the conclusion that the strain lacks this specialized lysis activity on blood cells. The results of hemolytic activity are given below in Figure 1.

The hemolytic activity of BCB1H comparative to positive control (E. coli).

3.1.3 Resistance to antibiotics

BCB1H had unique susceptibility patterns. It showed sensitivity (S) to β-lactam antibiotics (penicillin, amoxicillin), macrolides (erythromycin, azithromycin), and chloramphenicol, as evidenced by inhibitory zone widths that reached or exceeded criteria. However, resistance (R) was seen against quinolones (norfloxacin, enrofloxacin), aminoglycosides (amikacin, gentamicin), rifampin, lincomycin, and sulfonamides (compound sulfamethoxazole), as evidenced by reduced inhibitory zones. Azithromycin and rifampin demonstrated intermediate sensitivity (I). These findings give a thorough antibiotic resistance profile for BCB1H across multiple medication classes. The results of antibiotic susceptibility are given below in Table 2.

Antibiotic resistance assay of BCB1H strain against various antibiotics.

| Drug species | Drug name | Antibacterial circle diameter/mm | Resistance result |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Drug sensitive (R) | Middle sensitive (I) | Sensitive (S) | BCB1H | ||

| β-lactam antibiotics | Penicillin | ≤13 | 14–17 | ≥18 | S |

| Amoxicillin | ≤19 | 20–27 | ≥28 | S | |

| Macrolides | Erythromycin | ≤13 | 14–22 | ≥23 | S |

| Azithromycin | ≤13 | 14–17 | ≥18 | I | |

| Quinolones | Norfloxacin | ≤12 | 13–16 | ≥17 | R |

| Enrofloxacin | ≤13 | 14–16 | ≥17 | R | |

| Aminoglycoside antibiotics | Amikacin | ≤14 | 15–16 | ≥17 | R |

| Gentamicin | ≤12 | 13–14 | ≥15 | R | |

| Chloramphenicols | Chloramphenicol | ≤12 | 13–17 | ≥18 | S |

| Rifamycin | Rifampin | ≤16 | 17–19 | ≥20 | I |

| Lincosamides | Lincomycin | ≤14 | 15–20 | ≥21 | R |

| Sulfonamides | Compound sulfamethoxazole | ≤10 | 11–15 | ≥16 | R |

3.1.4 Acid and bile salt resistance

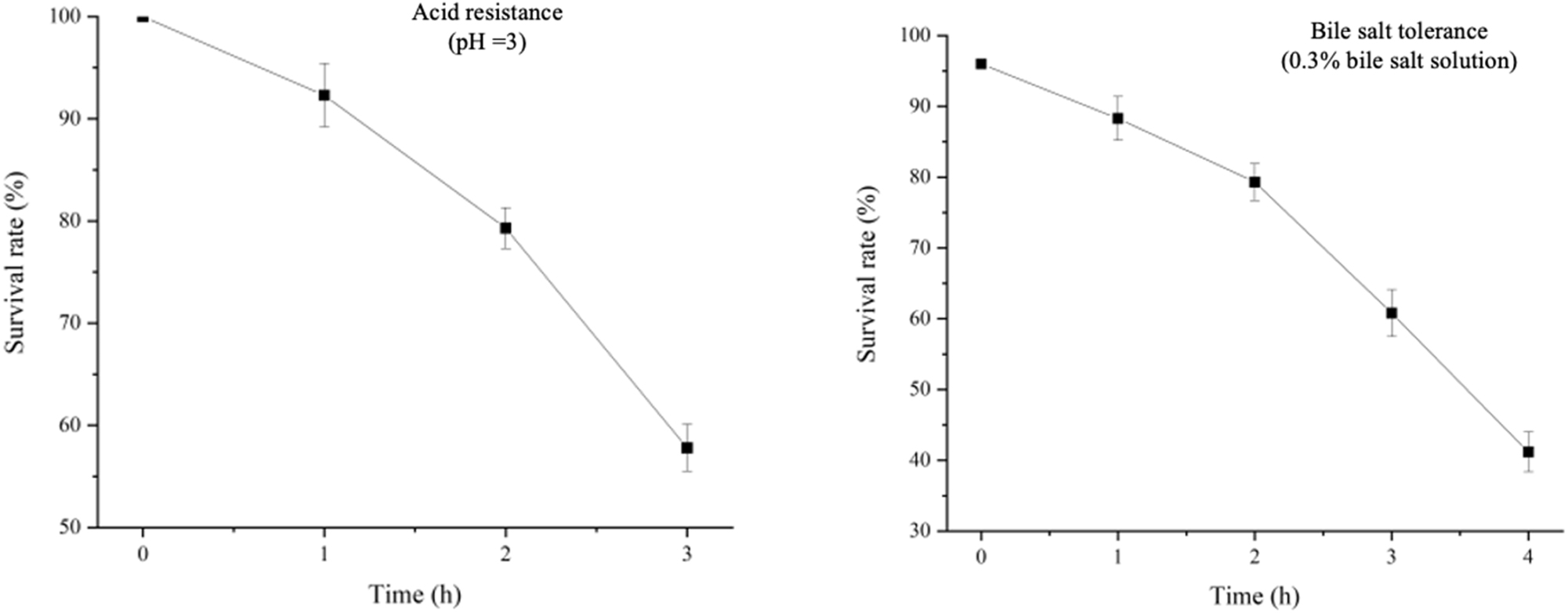

Cultures were grown to mid-log phase, with the original OD600 used as a control. The OD600 was determined following exposure to various pH levels (pH 3 and pH 4) and bile salt concentrations (0.1 %, 0.2 %, and 0.3 %). The control OD600 of 1.2748 demonstrated BCB1H’s robust development at neutral pH. However, in acidic conditions, OD600 gradually decreased. Notably, increasing bile salt concentrations caused a dose-dependent fall in OD600, indicating a decrease in bacterial viability. These findings, which were reproduced three times, shed light on BCB1H’s ability to adjust to acidic and bile salt conditions. The Figure 2 below depicts the graph of acid and bile resistance at various pH levels.

Acid resistance at 3 pH and the bile sale tolerance at 0.3 % bile salt concentrations.

3.1.5 Resistance to artificial gastrointestinal fluid

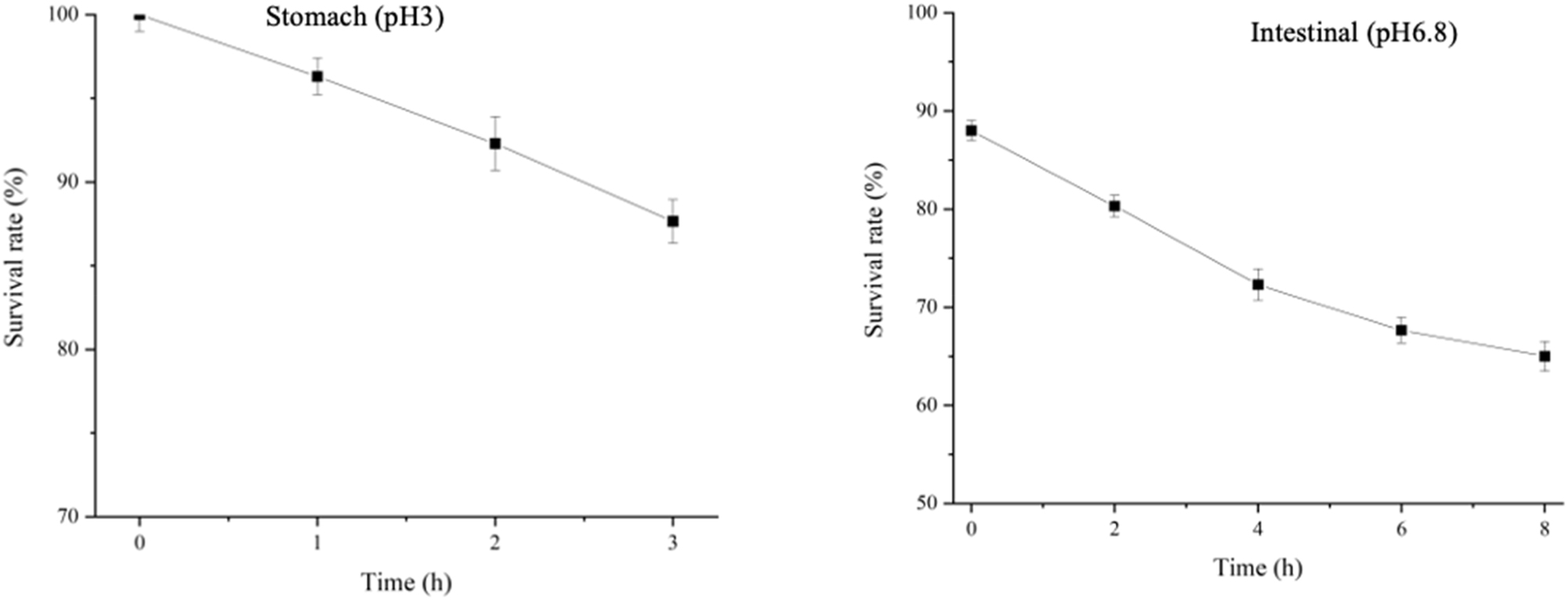

The resilience of BCB1H to artificial gastrointestinal conditions was examined by exposing bacterial cultures to synthetic stomach (pH 3) and intestine (pH 6.8) environments. Initial viable bacterial counts were measured, and further exposures indicated BCB1H’s ability to withstand dynamic pH fluctuations. Bacterial survival in the stomach (pH 3) was graphed as a fall from 100 to 87, indicating a moderate reduction in viable numbers. In the less acidic intestinal environment (pH 6.8), the survival graph fell from 87 to 65, demonstrating BCB1H’s resilience to various pH levels in the gastrointestinal tract. These data, derived from a triplicate experiment, provide vital insights into BCB1H’s potential as a probiotic, particularly given its ability to tolerate digestive system difficulties. The Figure 3 below depicts the graphs of artificial gastrointestinal fluid resistance of BCB1H.

Artificial gastrointestinal fluid resistance graphs for stomach environment at (pH 3) and intestinal environment at (pH 6.8).

3.1.6 Self-coagulation

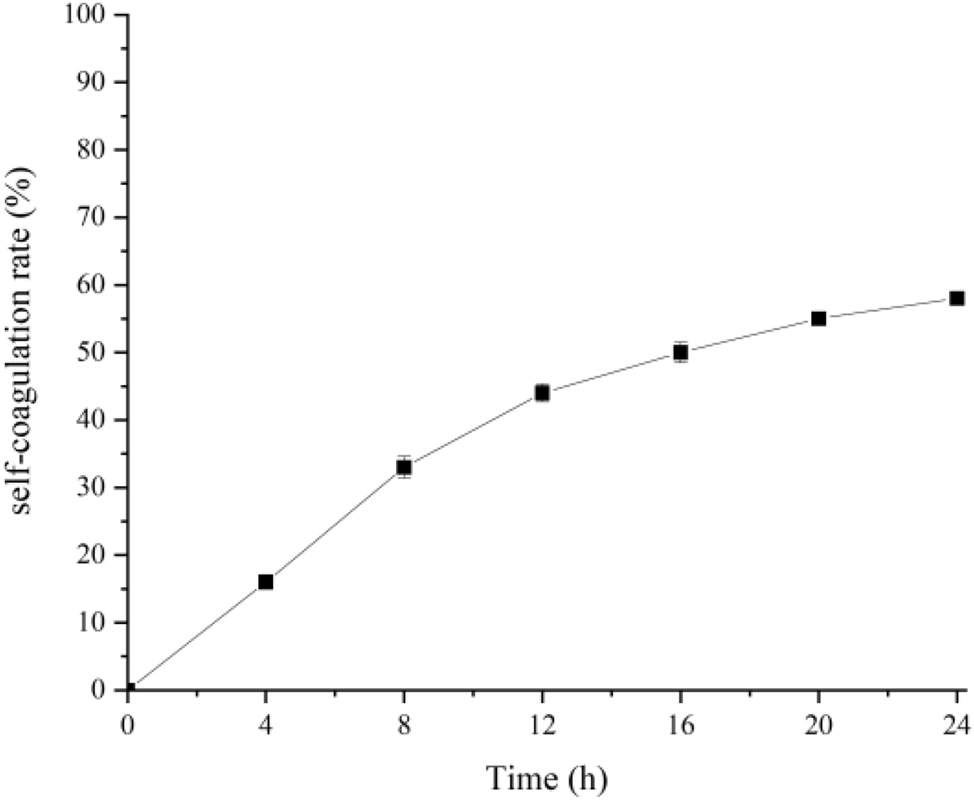

BCB1H’s self-coagulation capability was investigated by leaving bacterial cultures undisturbed and seeing apparent indicators of aggregation development over time. Optical density measurements were used to quantify the kinetics of self-coagulation. The experiment depicted visually as values decreasing from 0 to 55 %, revealed BCB1H’s spontaneous coagulation potential. These findings shed light on the bacterium’s potential applications in a variety of industrial and biotechnological settings where its self-coagulation characteristics may be advantageous. The Figure 4 below represents the percentage of self-coagulation rate in various time frames that is gradually increasing with the time frame.

The percentage of self-coagulation rate in various time frames.

3.1.7 Antioxidant activities

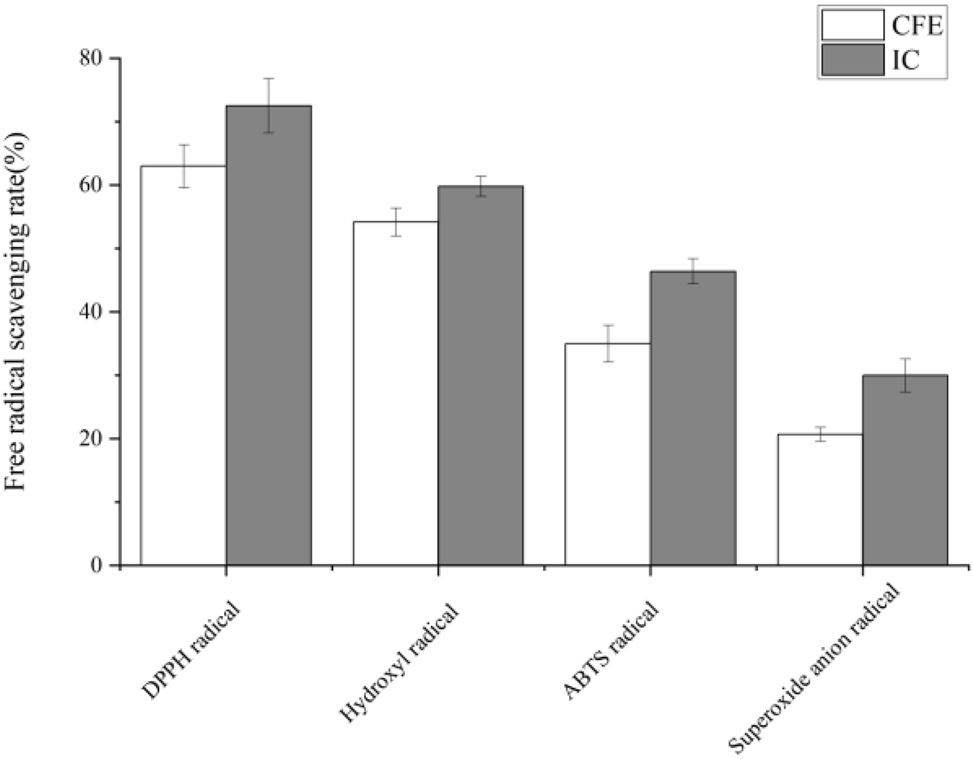

The 2,2-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl (DPPH) test exhibited 63 % radical scavenging activity. In the hydroxyl radical scavenging assay, BCB1H demonstrated a strong neutralizing capability of 58 %. The 2,2-azino-bis(3-ethylbenzothiazoline-6-sulfonic acid) (ABTS) radical scavenging experiment demonstrated a significant ability to quench ABTS radicals, reaching 38 %. The superoxide anion radical assay demonstrated a scavenging efficacy of 20 %. All experiments were performed multiple times allowing for a thorough understanding of BCB1H’s antioxidant properties against diverse reactive oxygen species. These findings highlight its potential applicability in health and biotechnology contexts, where antioxidant characteristics are critical. Figure 5 below represents the graph of antioxidant activity with four radical comparatives to control.

The antioxidant activity of BCB1H with DPPH, hydroxyl, ABTS and superoxide anion radicals.

3.2 Biological activity of EPS

3.2.1 Antioxidant activity

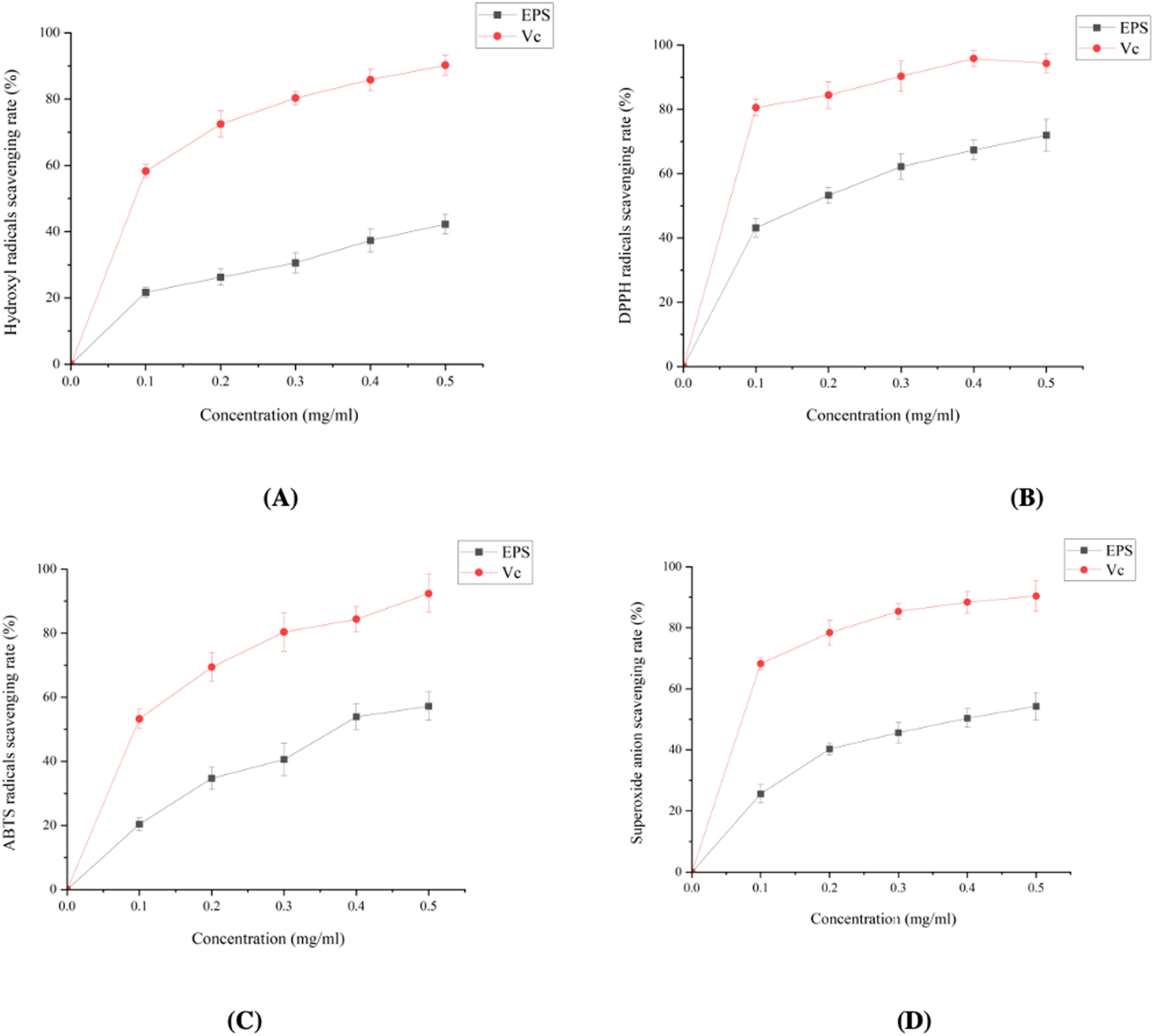

The 2,2-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl (DPPH) radical scavenging experiment revealed a radical neutralization capability ranging from 42 % to 63 % for EPS concentrations ranging from 0 to 0.5 mg/ml. The hydroxyl radical scavenging assay demonstrated a substantial ability to resist hydroxyl radicals, ranging from 0 % to 40 % for the same dose range. Additionally, the 2,2-azino-bis(3-ethylbenzothiazoline-6-sulfonic acid) (ABTS) radical scavenging experiment demonstrated a radical quenching effectiveness ranging from 42 % to 63 %. Furthermore, the superoxide anion radical assay demonstrated a scavenging capability ranging from 22 % to 45 %. All experiments, which were carried out in triplicate, provided a thorough understanding of the antioxidant potential of EPS produced by BCB1H, emphasizing its importance in a variety of biological and industrial applications. Figure 6 below represents the antioxidant activity of EPS produced by BCB1H.

Antioxidant activities of EPS produced by BCB1H. (A) Hydroxyl radical scavenging rate. (B) DPPH radicals scavenging rate. (C) ABTS radicals scavenging rate. (D) Superoxide anion scavenging rate.

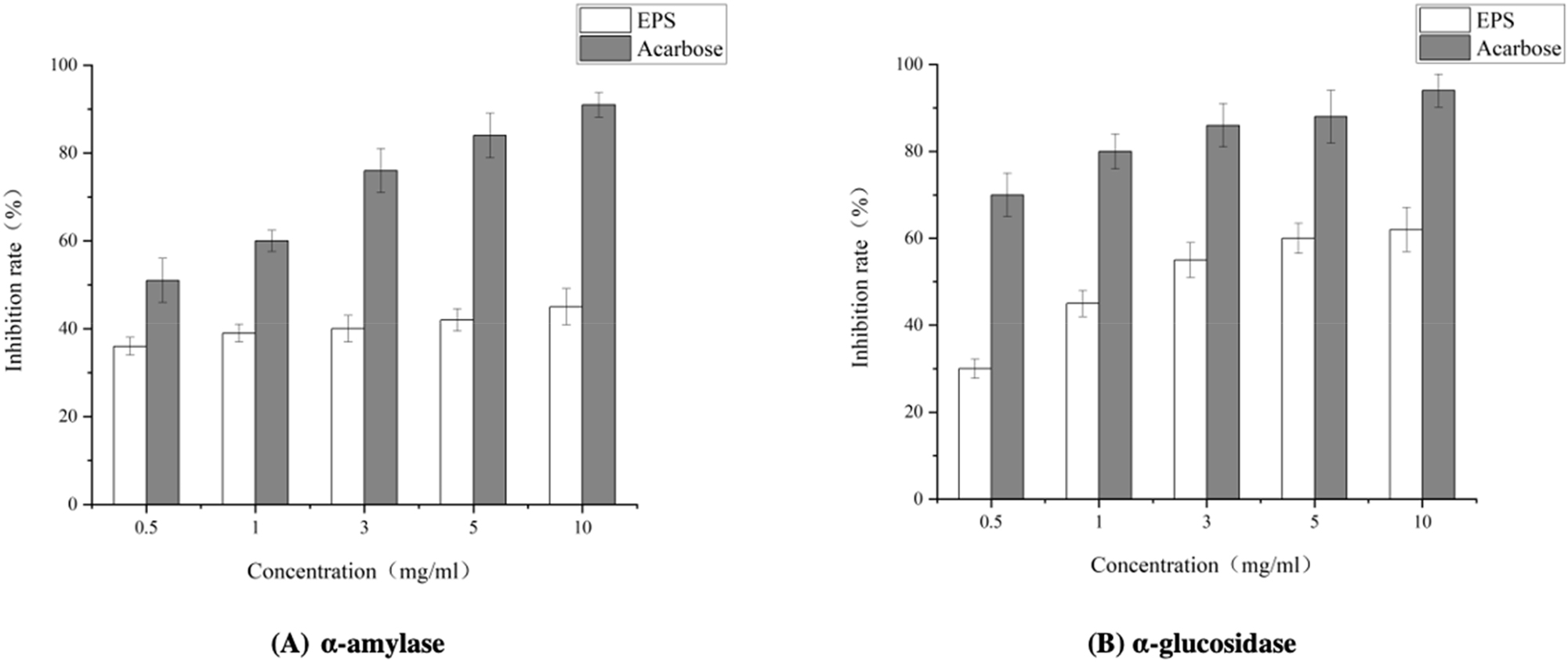

3.2.2 Hypoglycemic activity in vitro

BCB1H-EPS’s hypoglycemic activity was assessed in vitro through α-amylase and α-glucosidase inhibition tests. Concentrations ranging from 0.5 to 10 mg/ml were examined, and the inhibition rates were evaluated. BCB1H inhibited α-amylase concentration-dependently, reaching 50 % at the highest tested concentration (10 mg/ml). At a concentration of 10 mg/ml, the inhibitory impact of α-glucosidase grew progressively to 80 %. The results, obtained from triplicate experiments, signify EPS’s potential as a hypoglycemic agent by inhibiting key enzymes in glucose metabolism. Further interpretation and analysis will yield valuable insights into its use in blood glucose management. The Figure 7 below represents the hypoglycemic activities of BCB1H-EPS with α-amylase and α-glucosidase.

The hypoglycemic activities of BCB1H with α-amylase and α-glucosidase.

3.3 Genomic characteristics and functional annotations of P. acidilactici BCB1H

Approximately 1,915,620 base pairs make up the BCB1H genome, which has a 42.4 % GC content. There are 192 subsystems and 1895 genes in the genome. The genes present in the genome of BCB1H further comprised 29 % sub-system and 71 % non-subsystem coverage genes. There were 531 genes in the subsystem coverage, of which 512 were described and 19 were hypothetical. A non-subsystem coverage, on the other hand, consisted of 1,364 genes, of which 858 were predicted and 506 were speculative. Within the subsystem’s total of 721 categories, 120 were carbohydrates; 53 included cofactors, vitamins, prosthetic groups, and pigments; 49 included cell walls and capsules; 24 included virulence, disease, and defense; 3 included potassium metabolism; 4 included miscellaneous; 2 included phages and plasmid components; 18 membrane transport systems, 4 systems for iron acquisition and metabolism, 33 RNA metabolism, 78 systems for nucleosides and nucleotides, 119 protein metabolism, 5 cell division and cell cycle, 16 regulation and cell signaling, 50 DNA metabolism; 36 fatty acid biosynthesis; 6 dormancy and sporulation; 9 respiration; 16 stress response; 68 amino acid derivatives; 3 sulfur metabolism; and 4 phosphorus metabolism. The complete genomic features and overview are given below in Table S1. Figure S1 represents the category distribution of subsystems in BCB1H genome.

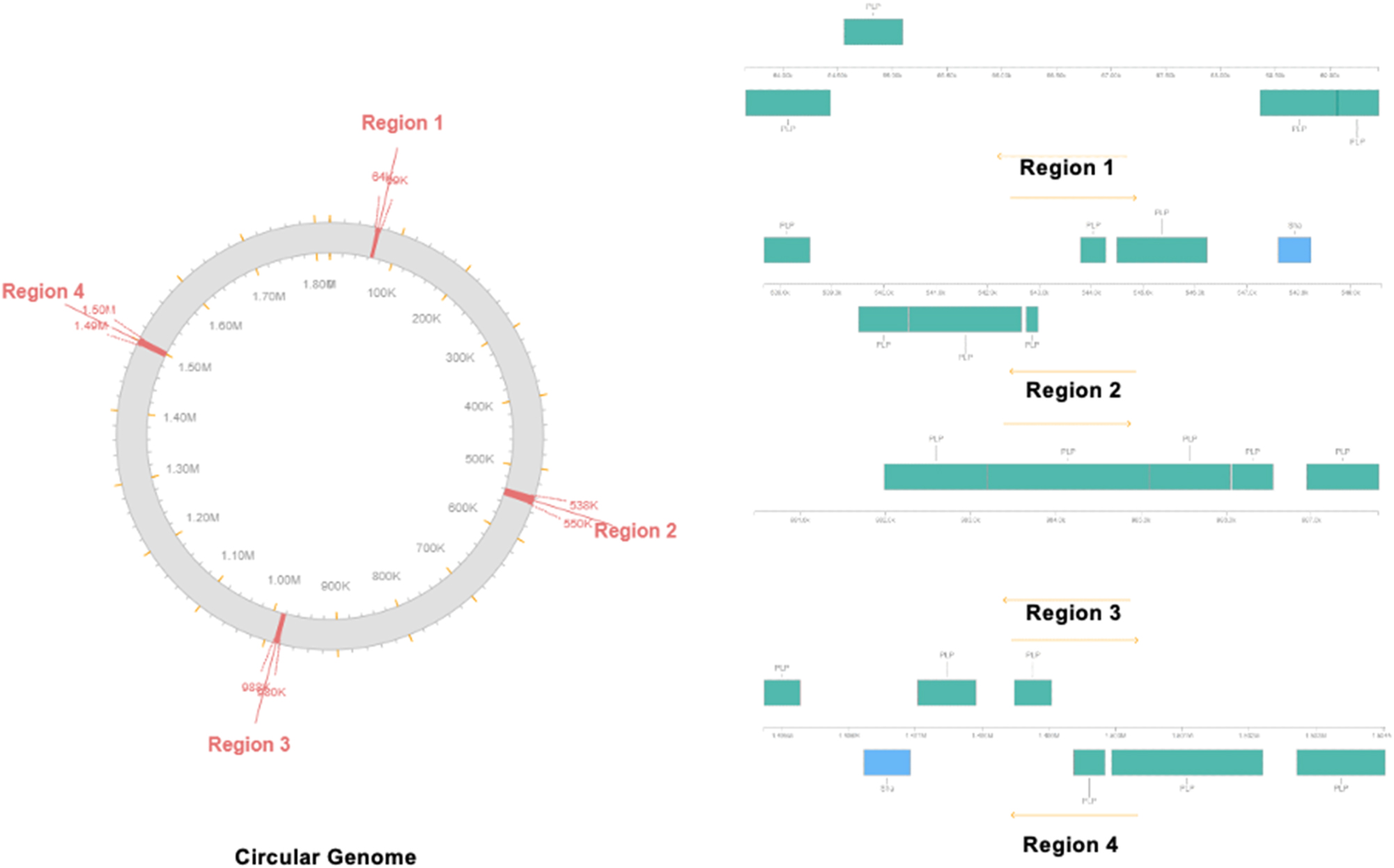

PHASTER found four important phage hits that will expand the genetic diversity and give access to genomic variation as bacteria develop. The phage regions identified by PHASTER throughout the whole genome of BCB1H are graphically represented in Figure 8.

Phage site prediction by PHASTER. Circular genome and expanded view of the all four phage sites identified in the genome.

The four notable hits were against phage portions of viruses and other bacteria that have previously been identified. The detailed information of the regions, size and sequence is given in Table 3 below.

The region length, scoring, region position and GC% of identified prophage regions.

| Region | Region length | Score | Total proteins | Region position | Most common phage | GC% |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 5.7 Kb | 10 | 9 | 63,661–69,446 | PHAGE_Arthro_Peas_NC_048096 | 43.57 % |

| 2 | 11.9 Kb | 20 | 14 | 537,692–549,606 | PHAGE_Pseudo_Lu11_NC_017972 | 42.08 % |

| 3 | 7.3 Kb | 10 | 8 | 980,471–987,792 | PHAGE_Bacill_G_NC_023719 | 43.51 % |

| 4 | 9.3 Kb | 20 | 11 | 1,494,731–1,504,042 | PHAGE_Lactoc_Q54_NC_008364 | 44.19 % |

`The CRISPR finder identified the CRISPR associated sequences in the genome of BCB1H and the results indicated three potential regions associated with CRISPR and Cas clusters. The start position, end position, spacer gene, cas genes, direction and evidence level are given below in Table 4.

Identified CRISPR associated sequences, region and sequences.

| Elements | Start | End | Spacer/gene | Repeat consensus/cas genes | Evidence level |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CRISPR | 1,359,285 | 1,359,388 | 1 | CAGATGCTCTACCAACTGAGCTAA | 1 |

| CRISPR | 1,553,457 | 1,554,548 | 16 | GATCTTAACCTTATTGATTTAACATCCTTCTGAAAC | 4 |

| Cas cluster | 1,554,577 | 1,560,749 | 4 | csn2_TypeIIA, cas2_TypeI-II-III, cas1_TypeII, cas9_TypeII |

3.3.1 Comparative genomics and phylogenetics analysis

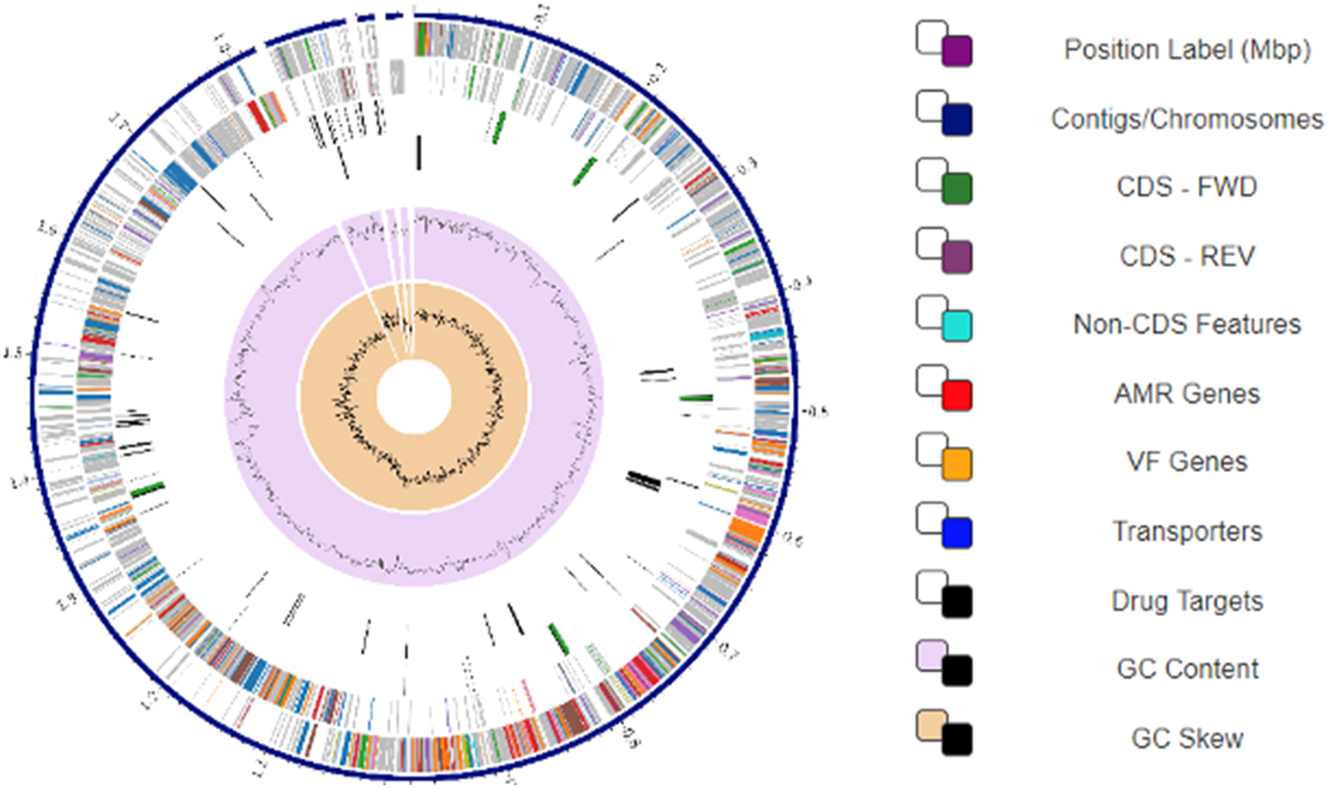

The circular view of the BCB1H genome was obtained by the PATRIC (BV-BRC) and analyzed for the presence of CDS, non-CDS features, drug targets and VF genes. The circular map of the BCB1H gene is given below in Figure 9.

Circular map of the BCB1H genome representing the genomic characteristics of genome.

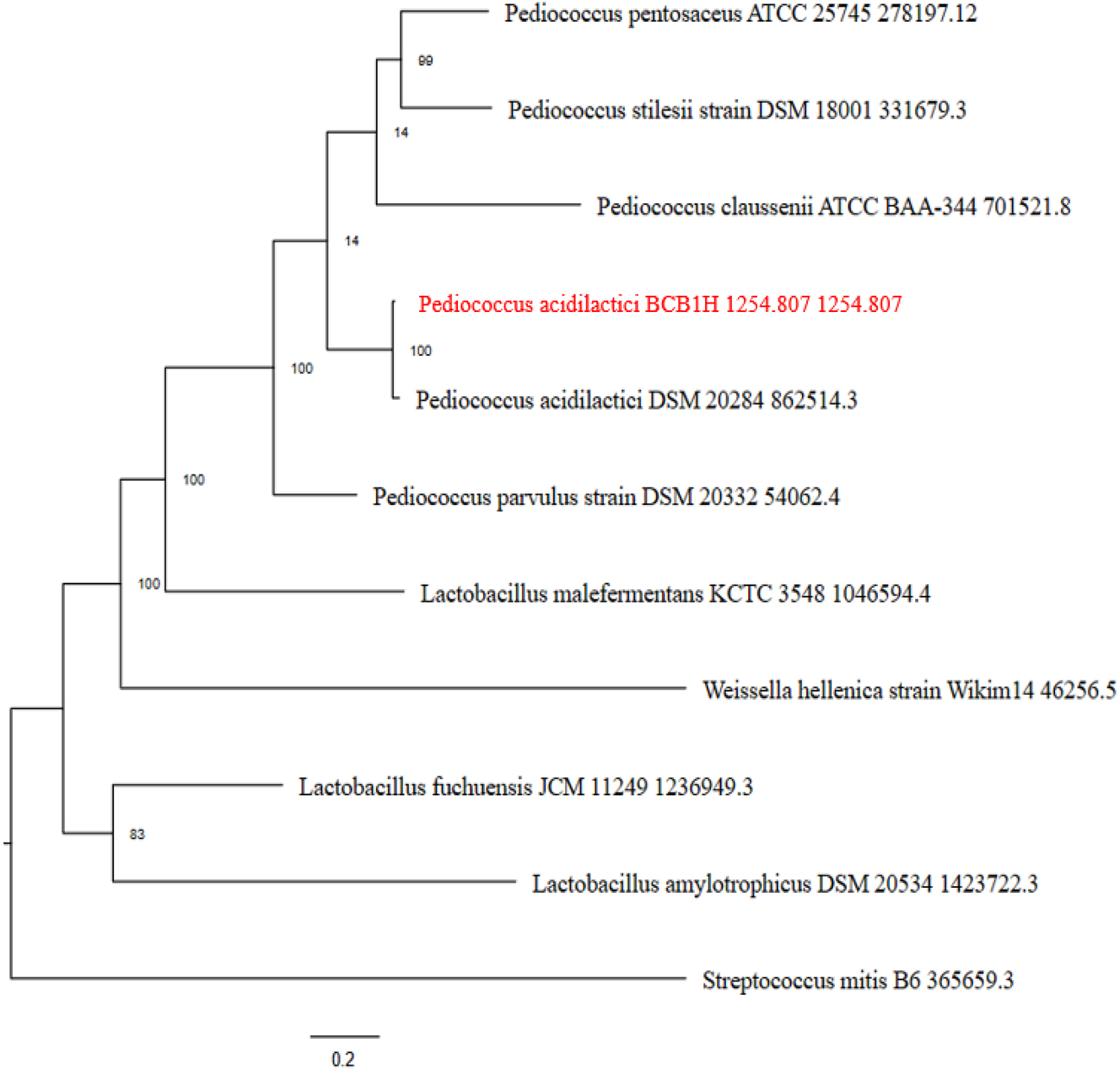

The phylogenetic tree was analyzed by MEGA-X software and the tree was obtained. The maximum likelihood similarity was observed with the other strains of P. acidilactici DSM and Pediococcus parvulus DSM. The minimum likelihood was observed with streptococcus mitis and lactobacillus strains. The phylogenetic tree is given below in the Figure 10.

The phylogenetic tree of the BCB1H genome representing the maximum likelihood with various strains.

3.3.2 Identification of specialty genes

As per the results of comprehensive genome analysis, there were total 28 specialty genes present in the BCB1H genome related to antibiotic resistance category according to PATRIC. On the other hand, total 8 specialty genes related to Transporter category were detected according to TCDB. But, CARD and NDARO detected only single gene related to antibiotic resistance in the whole genome. The detailed results of specialty genes prediction are given below in Table 5 where the RefSeq locus tag, Gene and their products are mentioned.

Specialty genes predicted by PATRIC (BV-BRC) in the BCB1H genome by various methods.

| Specialty genes | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Antibiotic resistance (PATRIC) | Transporter (TCDB) | |||||

| RefSeq locus tag | Gene | Product | RefSeq locus tag | Gene | Product | |

| L2V67_09050 | Tet(M) | Tetracycline resistance, ribosomal protection type ≥ Tet(M) | L2V67_06040 | lrgA | Antiholin-like protein LrgA | |

| L2V67_01345 | gidB | 16S rRNA (guanine(527)-N(7))-methyltransferase (EC 2.1.1.170) | L2V67_02420 | manY | PTS system, mannose-specific IID component | |

| L2V67_02900 | EF-G | Translation elongation factor G | L2V67_02415 | manX | PTS system, mannose-specific IIC component | |

| L2V67_03565 | Ddl | d-alanine--d-alanine ligase (EC 6.3.2.4) | L2V67_09270 | hypothetical protein | ||

| L2V67_05505 | inhA, fabI | Enoyl-[acyl-carrier-protein] reductase [NADH] (EC 1.3.1.9) | L2V67_09280 | hypothetical protein | ||

| L2V67_02905 | S10p | SSU ribosomal protein S10p (S20e) | L2V67_01875 | glpF | Glycerol uptake facilitator protein | |

| L2V67_04170 | Iso-tRNA | Isoleucyl-tRNA synthetase (EC 6.1.1.5) | L2V67_09090 | hypothetical protein | ||

| L2V67_02865 | rpoB | DNA-directed RNA polymerase beta subunit (EC 2.7.7.6) | L2V67_09265 | comA | Competence-stimulating peptide ABC transporter ATP-binding protein ComA | |

| L2V67_03685 | PgsA | CDP-diacylglycerol--glycerol-3-phosphate 3-phosphatidyltransferase (EC 2.7.8.5) | Antibiotic resistance (CARD) | |||

| RefSeq locus tag | Gene | Product | ||||

| L2V67_05535 | kasA | 3-Oxoacyl-[acyl-carrier-protein] synthase, KASII (EC 2.3.1.179) | L2V67_09050 | tetM | Tetracycline resistance, ribosomal protection type ≥ Tet(M) | |

| L2V67_05845 | GdpD | Glycerophosphoryl diester phosphodiesterase (EC 3.1.4.46) | Antibiotic resistance (NDARO) | |||

| RefSeq locus tag | Gene | Product | ||||

| L2V67_08525 | RlmA(II) | 23S rRNA (guanine(748)-N(1))-methyltransferase (EC 2.1.1.188) | L2V67_09050 | tet(M) | Tetracycline resistance, ribosomal protection type ≥ Tet(M) | |

| L2V67_02890 | S12p | SSU ribosomal protein S12p (S23e) | ||||

| L2V67_08255 | fabV | Enoyl-[acyl-carrier-protein] reductase [NADH] (EC 1.3.1.9), FabV ≥ refractory to triclosan | ||||

| L2V67_05060 | folP | Dihydropteroate synthase (EC 2.5.1.15) | ||||

| L2V67_04350 | EF-Tu | Translation elongation factor Tu | ||||

| L2V67_02150 | MurA | UDP-N-acetylglucosamine 1-carboxyvinyltransferase (EC 2.5.1.7) | ||||

| L2V67_04840 | folA, Dfr | Dihydrofolate reductase (EC 1.5.1.3) | ||||

| L2V67_00025 | gyrB | DNA gyrase subunit B (EC 5.99.1.3) | ||||

| L2V67_00030 | gyrA | DNA gyrase subunit A (EC 5.99.1.3) | ||||

| L2V67_02155 | rho | Transcription termination factor Rho | ||||

| L2V67_02870 | rpoC | DNA-directed RNA polymerase beta’ subunit (EC 2.7.7.6) | ||||

| L2V67_02205 | Alr | Alanine racemase (EC 5.1.1.1) | ||||

3.3.3 Antibiotic resistance genes prediction

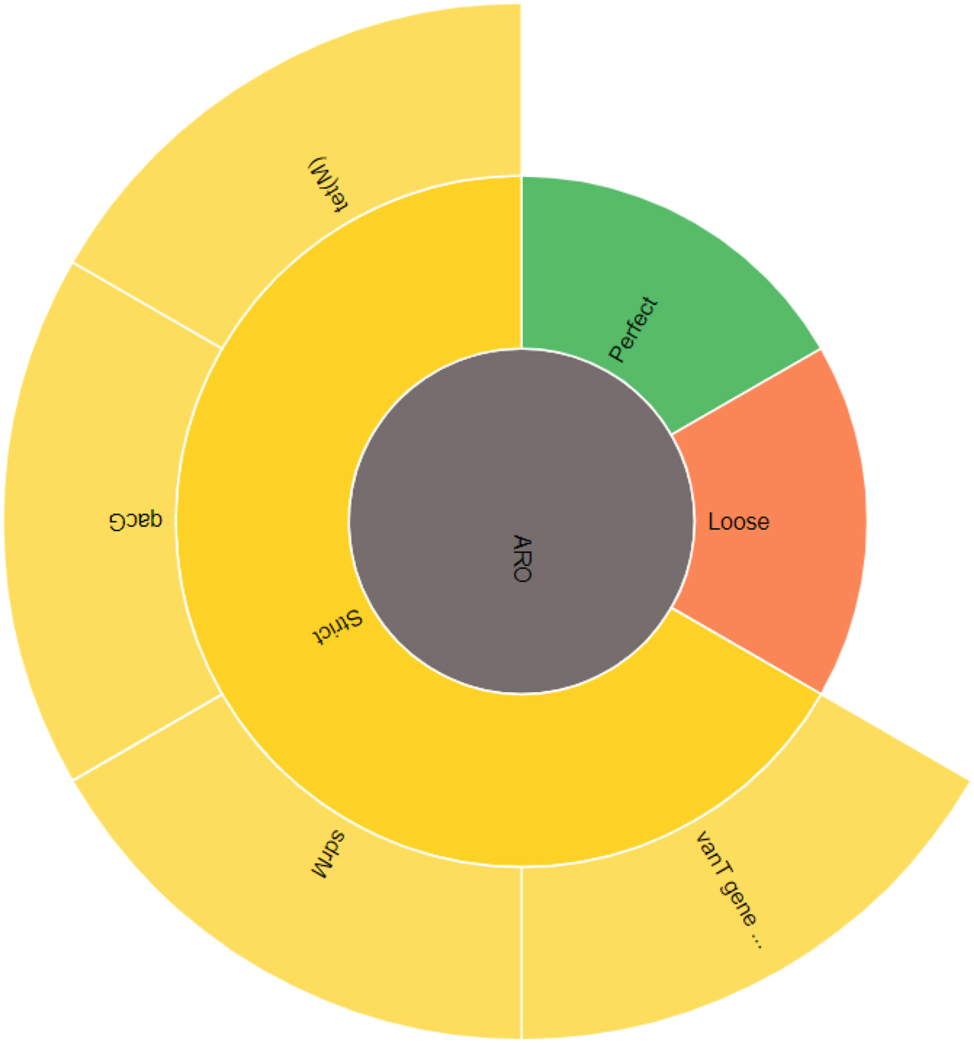

The comprehensive antibiotic resistance database (CARD) provided four types of strict antibiotic resistance with strict RGI criteria. The resistance to these antibiotics was mediated by two genes that followed the mechanism of antibiotic efflux, and the rest two were mediated by the mechanism of antibiotic target alteration. All these detections were performed by protein homology modeling. The detailed results are given below in Table 6 where the detection criteria, ARO terms, mechanism of resistance and drug classes are mentioned.

Antibiotic resistance criteria for the whole genome of BCB1H.

| ARO term | AMR gene family | Drug class | Resistance mechanism | % Identity | % Length |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| vanT gene in vanG cluster | Glycopeptide resistance gene cluster, vanT | Glycopeptide antibiotic | Antibiotic target alteration | 31.79 | 52.67 |

| sdrM | Major facilitator superfamily (MFS) antibiotic efflux pump | Fluoroquinolone antibiotic, disinfecting agents and antiseptics | Antibiotic efflux | 34.81 | 109.40 |

| qacG | Small multidrug resistance (SMR) antibiotic efflux pump | Disinfecting agents and antiseptics | Antibiotic efflux | 48.11 | 99.07 |

| tet(M) | Tetracycline-resistant ribosomal protection protein | Tetracycline antibiotic | Antibiotic target protection | 99.37 | 100.00 |

The diagrammatic explanation of the antibiotic resistance genes in the whole genome of BCB1H along with RGI criteria is depicted below in Figure 11.`

Graphical representation of AMR genes in BCB1H.

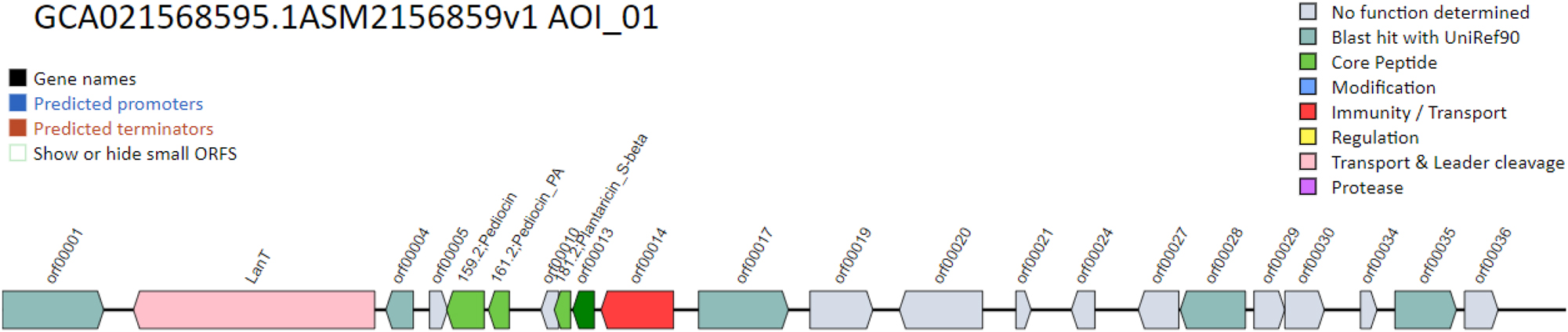

3.3.4 Bacteriocin production

Bacteriocin-producing genes were identified throughout the genome under inquiry after extensive interpretation and analysis. These findings shed light on BCB1H bacteriocin-producing capabilities, allowing for a better knowledge of its genetic properties and possible applications in biotechnological and therapeutic contexts. A total of 11 genes were predicted by BAGEL 5 which are given below in Table 7.

Condensed gene table for the bacteriocin-producing genes in BCB1H genome.

| Name | Function |

|---|---|

| orf00001 | Probable replication protein rep OS = Bifidobacterium longum (strain NCC 2705) OX = 206,672 GN = rep PE = 3 SV = 1 |

| LanT | Pediocin PA-1 transport/processing ATP-binding protein pedD |

| orf00004 | Pediocin PA-1 biosynthesis protein pedC |

| 159.2;Pediocin | 159.2;Pediocin |

| 161.2;Pediocin_PA | bacteriocinII; Bacteriocin_II; L_biotic_typeA; Bacteriocin_IIc; 161.2; Pediocin_PA |

| 181.2;Plantaricin_S-beta | 181.2;Plantaricin_S-beta |

| orf00013 | ComC; Bacteriocin_IIc; |

| orf00014 | Putative bacteriocin immunity protein |

| orf00017 | Probable transposase for insertion-like sequence element IS1161 OS = Streptococcus salivarius OX = 1304 PE = 3 SV = 1 |

| orf00028 | Probable integrase/recombinase YoeC OS = Bacillus subtilis (strain 168) OX = 224,308 GN = yoeC PE = 3 SV = 2 |

| orf00035 | Protein rlx OS = Staphylococcus aureus OX = 1280 GN = rlx PE = 4 SV = 1 |

The genes with predicted potentials of bacteriocin prediction are further explained diagrammatically in Figure 12 below. The gene names are given in black, predicted promoters are depicted in blue color and brown color represents the predicted terminators.

Diagrammatic elaboration of the bacteriocin producing genes in BCB1H.

3.3.5 Human pathogen detection

The PathogenFinder tool, accessed on January 7, 2024, was used to conduct a preliminary assessment of the BCB1H strain’s safety. The genome was submitted in FASTA format, which made it easier to analyze numerous aspects. The tool classified the input organism as a non-human pathogen, with a likelihood of being a human pathogen assessed at 0.163. The input proteome coverage was 0.76 %, indicating that the strain is unlikely to be a human pathogen. Further study resulted in particular information about the linked pathogenic and non-pathogenic families. Surprisingly, no matches were detected in pathogenic families, whereas 14 matches were discovered in non-pathogenic families. The detailed analysis of the sequences, total base pairs, and sequence lengths added to the overall assessment of the BCB1H strain. These data provide an important foundation for understanding the strain’s safety profile in terms of human health.

3.3.6 Detection of EPS biosynthesis genes

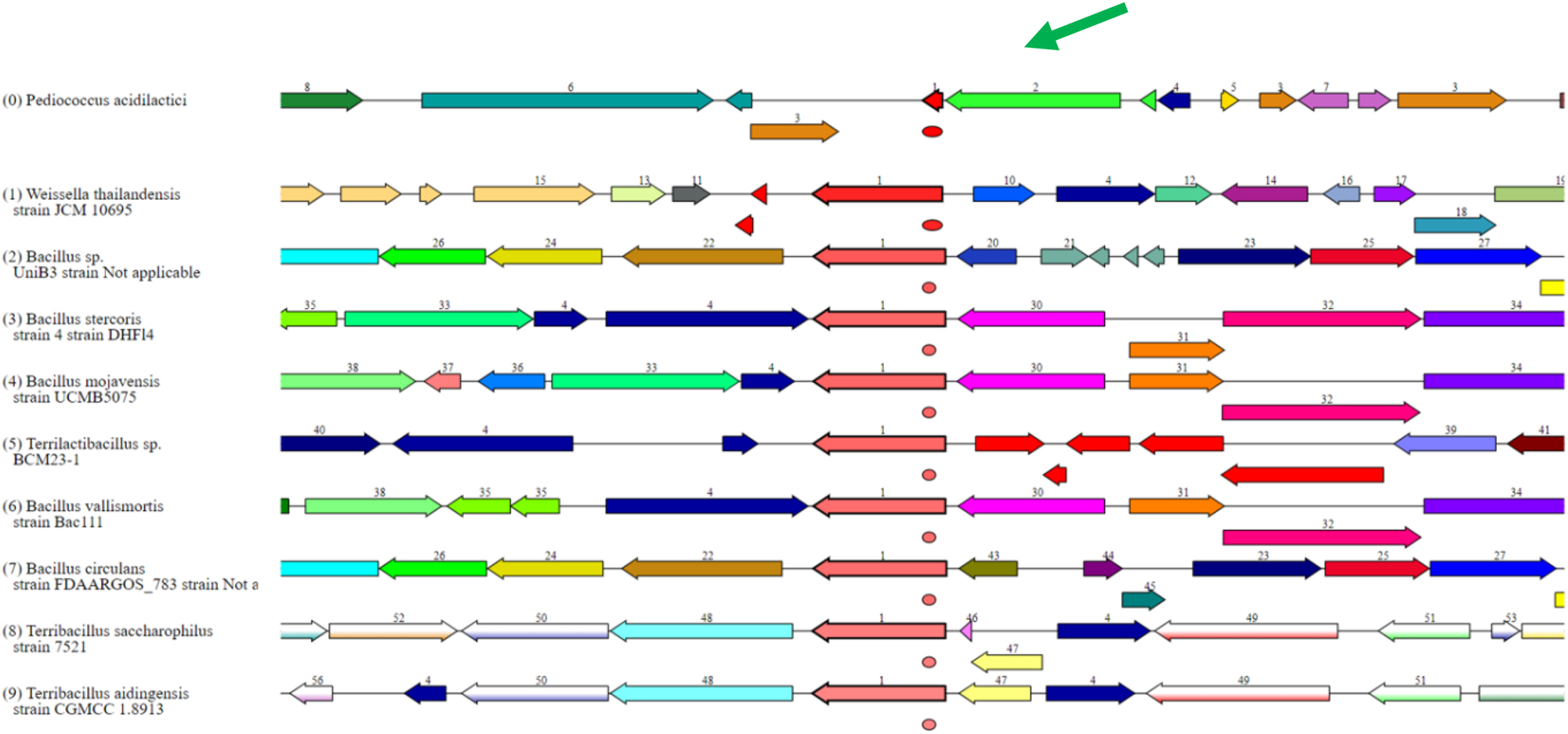

The PROKA (BV-BRC) platform was used to analyze the P. acidilactici genome and discovered genes involved in exopolysaccharide (EPS) biosynthesis. Several critical genes were found, including those that encode enzymes involved in the polymerization and modification of EPS. The functional study revealed conserved motifs and domains, confirming their potential roles in EPS biosynthesis. Comparative investigation of known EPS biosynthesis genes in related species revealed both similarities and differences. The comparative diagram of EPS biosynthesis-related genes in various genomes is given below in Figure 13.

The EPS biosynthesis associated gene set in P. acidilactici is highlighted in the green color, comparatively different genomes have been aligned.

4 Discussion

The study on P. acidilactici, specifically the BCB1H strain, provided important insights into its genetic and functional characteristics. The bacterium demonstrated a wide range of biological activities, including significant antibacterial activity against several diseases. Antibiotic resistance profiling revealed diverse susceptibility patterns, providing a thorough understanding of its potential applications [10]. The genomic analysis revealed the presence of specialized genes involved in antibiotic resistance and transporters. BCB1H showed resistance to acidic and bile salt environments, indicating its potential as a probiotic. Furthermore, the strain demonstrated self-coagulation and antioxidant activity, highlighting its flexibility. The PROKA platform enabled a focused analysis of the genetic basis of exopolysaccharide production [24]. The strain’s wide antibacterial activities indicate its promise as a natural antimicrobial agent, including inhibitory zones against a variety of harmful bacteria. Antibiotic resistance profile gives critical information on susceptibility patterns, directing possible therapeutic applications [25]. The capacity to withstand acidic and bile salt environments, together with self-coagulation capabilities, implies that it could be a good probiotic option for gastrointestinal health applications. The presence of specialist genes, as well as the identification of bacteriocin-producing genes, adds to its genetic flexibility. Exploring EPS biosynthesis genes with the PROKA platform provides specific insights into the genetic basis of exopolysaccharide production, which may have ramifications for a variety of industrial applications [26].

The results of this study on BCB1H have important significance for a variety of sectors. The strain’s various biological activity, antibiotic resistance profile, and genetic characteristics make it a prospective candidate for use in the pharmaceutical and food industries. Its antibacterial properties suggest that it could be used as a natural antimicrobial agent or probiotic to promote gastrointestinal health [27]. The discovered antibiotic-resistance genes provide information for antibiotic development and therapy techniques. Bacteriocin-producing genes provide opportunities for creating new antimicrobial drugs. Understanding EPS biosynthesis genes improves information for industrial applications, such as the manufacturing of bioactive molecules [28].

While this study provides insight into the genetic and molecular properties of P. acidilactici BCB1H, significant limitations should be addressed. Experimental validation of predicted genes and functions is required for reliable conclusions. Furthermore, broadening the analysis to include additional P. acidilactici strains would improve the findings’ generalizability. Future study should focus on functional genomics, experimental validation, and investigating the strain’s interactions in complex microbial ecosystems. Furthermore, examining the strain’s possible applications in certain industrial and medicinal situations will help to gain a more complete knowledge of its practical utility.

5 Conclusions

In conclusion, our study sheds light on the genetic and biological properties of P. acidilactici BCB1H, demonstrating its promise in a variety of industrial and medicinal applications. The strain’s various biological activity, antibiotic resistance profile, and bacteriocin-producing capabilities present significant opportunities for the pharmaceutical and food industries. However, the study recognizes the importance of experimental confirmation of predicted genes and recommends broadening the analysis to include a wider range of P. acidilactici strains. Future research should concentrate functional genomics studies, rigorous experimental validations, and investigations into the strain’s uses in specific industrial and medicinal contexts. This comprehensive approach will not only improve our understanding of P. acidilactici potential, but also open the road for its practical application in a variety of disciplines.

Funding source: National Natural Science Foundation of China

Award Identifier / Grant number: Project No. 32272296

Acknowledgments

Authors are thankful to the Researchers Supporting Project number (RSP2024R491), King Saud University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia.

-

Research ethics: This article does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors. Therefore, as an observational study, it doesn’t require any ethical approval.

-

Author contributions: Conceptualization, Tariq Aziz and Yang Zhennai; methodology, Gege Hu; software, Muhammad Naveed; validation, Muhammad Aqib Shabbir; formal analysis, Abdulrahman Alshammari; investigation, Abid Sarwar; resources, Junaid Yousaf.; data curation, Abid Sarwar; writing – original draft preparation, Tariq Aziz; writing – review and editing, Metab Alharbi; visualization, Muhammad Aqib Shabbir; supervision, Yang Zhennai; project administration, Tariq Aziz; funding acquisition, Tariq Aziz.

-

Competing interest: The authors declare no conflict of interest.

-

Research funding: This research work was supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China (Project No. 32272296).

-

Data availability: All the data has been included in the manuscript.

References

1. Qiao, Y, Qiu, Z, Tian, F, Yu, L, Zhao, J, Zhang, H, et al.. Pediococcus acidilactici strains improve constipation symptoms and regulate intestinal flora in mice. Front Cell Infect Microbiol 2021;11:655258. https://doi.org/10.3389/fcimb.2021.655258.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

2. Fugaban, JII, Vazquez Bucheli, JE, Park, YJ, Suh, DH, Jung, ES, Franco, BDGD. M, et al.. Antimicrobial properties of Pediococcus acidilactici and Pediococcus pentosaceus isolated from silage. J Appl Microbiol 2022;132:311–30. https://doi.org/10.1111/jam.15205.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

3. Song, Y-R, Lee, C-M, Lee, S-H, Baik, S-H. Evaluation of probiotic properties of Pediococcus acidilactici M76 producing functional exopolysaccharides and its lactic acid fermentation of black raspberry extract. Microorganisms 2021;9:1364. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms9071364.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

4. Yoon, J-W, Kang, S-S. In vitro antibiofilm and anti-inflammatory properties of bacteriocins produced by Pediococcus acidilactici against Enterococcus faecalis. Foodborne Pathog Dis 2020;17:764–71. https://doi.org/10.1089/fpd.2020.2804.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

5. Qiu, Z, Fang, C, Gao, Q, Bao, J. A short-chain dehydrogenase plays a key role in cellulosic D-lactic acid fermentability of Pediococcus acidilactici. Bioresour Technol 2020;297:122473. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biortech.2019.122473.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

6. Aziz, T, Sarwar, A, Ud Din, J, Al Dalali, S, Khan, AA, Din, ZU, et al.. Biotransformation of linoleic acid into different metabolites by food derived Lactobacillus plantarum 12-3 and in silico characterization of relevant reactions. Food Res Int 2021;147:110470. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodres.2021.110470.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

7. Abdollahzadeh, E, Nematollahi, A, Hosseini, H. Composition of antimicrobial edible films and methods for assessing their antimicrobial activity: a review. Trends Food Sci Technol 2021;110:291–303. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tifs.2021.01.084.Search in Google Scholar

8. Bhuyar, P, Rahim, M, Sundararaju, S, Maniam, G, Govindan, N. Antioxidant and antibacterial activity of red seaweed Kappaphycus alvarezii against pathogenic bacteria. Global J Environ Sci Manage 2020;6:47–58.Search in Google Scholar

9. Yang, X, Peng, Z, He, M, Li, Z, Fu, G, Li, S, et al.. Screening, probiotic properties, and inhibition mechanism of a Lactobacillus antagonistic to Listeria monocytogenes. Sci Total Environ 2024;906:167587. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2023.167587.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

10. Hu, G, Hu, H, Aziz, T, Shao, H, Yang, Z, Alharbi, M, et al.. Depiction of the dairy product supplemented with the exopolysaccharide from Pediococcus acidilactici BCB1H by metabolomics analysis. J Food Meas Char 2023;18:1690–1704.10.1007/s11694-023-02283-ySearch in Google Scholar

11. Li, N, Pang, B, Li, J, Liu, G, Xu, X, Shao, D, et al.. Mechanisms for Lactobacillus rhamnosus treatment of intestinal infection by drug-resistant Escherichia coli. Food Funct 2020;11:4428–45. https://doi.org/10.1039/d0fo00128g.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

12. Mahdi, S, Azzi, R, Lahfa, FB. Evaluation of in vitro α-amylase and α-glucosidase inhibitory potential and hemolytic effect of phenolic enriched fractions of the aerial part of Salvia officinalis L. Diabetes Metabol Syndr Clin Res Rev 2020;14:689–94. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dsx.2020.05.002.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

13. Aziz, T, Naveed, M, Shabbir, MA, Sarwar, A, Ali Khan, A, Zhennai, Y, et al.. Comparative genomics of food-derived probiotic Lactiplantibacillus plantarum K25 reveals its hidden potential, compactness, and efficiency. Front Microbiol 2023;14:1214478. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2023.1214478.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

14. Aziz, T, Naveed, M, Makhdoom, SI, Ali, U, Mughal, MS, Sarwar, A, et al.. Genome investigation and functional annotation of Lactiplantibacillus plantarum YW11 revealing streptin and ruminococcin-A as potent nutritive bacteriocins against gut symbiotic pathogens. Molecules 2023;28:491. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules28020491.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

15. Davis, JJ, Wattam, AR, Aziz, RK, Brettin, T, Butler, R, Butler, RM, et al.. The PATRIC Bioinformatics Resource Center: expanding data and analysis capabilities. Nucleic Acids Res 2020;48:D606–12. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkz943.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

16. Aziz, RK, Bartels, D, Best, AA, DeJongh, M, Disz, T, Edwards, RA, et al.. The RAST Server: rapid annotations using subsystems technology. BMC Genom 2008;9:75. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2164-9-75.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

17. Overbeek, R, Olson, R, Pusch, GD, Olsen, GJ, Davis, JJ, Disz, T, et al.. The SEED and the rapid annotation of microbial genomes using subsystems technology (RAST). Nucleic Acids Res 2014;42:D206–214. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkt1226.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

18. Arndt, D, Grant, JR, Marcu, A, Sajed, T, Pon, A, Liang, Y, et al.. PHASTER: a better, faster version of the PHAST phage search tool. Nucleic Acids Res 2016;44:W16–21. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkw387.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

19. Symeonidi, E, Regalado, J, Schwab, R, Weigel, D. CRISPR-finder: a high throughput and cost effective method for identifying successfully edited A. thaliana individuals. bioRxiv 2020.06.25.171538. https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.06.25.171538.Search in Google Scholar

20. Alcock, BP, Huynh, W, Chalil, R, Smith, KW, Raphenya, AR, Wlodarski, MA, et al.. CARD 2023: expanded curation, support for machine learning, and resistome prediction at the Comprehensive Antibiotic Resistance Database. Nucleic Acids Res 2023;51:D690–9. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkac920.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

21. van Heel, AJ, de Jong, A, Song, C, Viel, JH, Kok, J, Kuipers, OP. BAGEL4: a user-friendly web server to thoroughly mine RiPPs and bacteriocins. Nucleic Acids Res 2018;46:W278–81. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gky383.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

22. Cosentino, S, Voldby Larsen, M, Møller Aarestrup, F, Lund, O. PathogenFinder-distinguishing friend from foe using bacterial whole genome sequence data. PLoS One 2013;8:e77302. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0077302.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

23. Olson, RD, Assaf, R, Brettin, T, Conrad, N, Cucinell, C, Davis, JJ, et al.. Introducing the bacterial and viral bioinformatics resource center (BV-BRC): a resource combining PATRIC, IRD and ViPR. Nucleic Acids Res 2023;51:D678–d689. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkac1003.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

24. Al-Emran, HM, Moon, JF, Miah, ML, Meghla, NS, Reuben, RC, Uddin, MJ, et al.. Genomic analysis and in vivo efficacy of Pediococcus acidilactici as a potential probiotic to prevent hyperglycemia, hypercholesterolemia and gastrointestinal infections. Sci Rep 2022;12:20429. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-24791-5.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

25. Chen, Y, Ren, L, Sun, L, Bai, X, Zhuang, G, Cao, B, et al.. Amphiphilic silver nanoclusters show active nano–bio interaction with compelling antibacterial activity against multidrug-resistant bacteria. NPG Asia Mater 2020;12:56. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41427-020-00239-y.Search in Google Scholar

26. Hu, G, Jiang, H, Zong, Y, Datsomor, O, Kou, L, An, Y, et al.. Characterization of lactic acid-producing bacteria isolated from rumen: growth, acid and bile salt tolerance, and antimicrobial function. Fermentation 2022;8:385. https://doi.org/10.3390/fermentation8080385.Search in Google Scholar

27. Tian, P, Chen, Y, Qian, X, Zou, R, Zhu, H, Zhao, J, et al.. Pediococcus acidilactici CCFM6432 mitigates chronic stress-induced anxiety and gut microbial abnormalities. Food Funct 2021;12:11241–9. https://doi.org/10.1039/d1fo01608c.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

28. Surachat, K, Kantachote, D, Deachamag, P, Wonglapsuwan, M. Genomic insight into Pediococcus acidilactici HN9, a potential probiotic strain isolated from the traditional Thai-style fermented Beef Nhang. Microorganisms 2020;9:50. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms9010050.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

Supplementary Material

This article contains supplementary material (https://doi.org/10.1515/znc-2024-0074).

© 2024 the author(s), published by De Gruyter, Berlin/Boston

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Review Articles

- Advancing psoriasis drug delivery through topical liposomes

- Hepatoprotective activity of medicinal plants, their phytochemistry, and safety concerns: a systematic review

- Research Articles

- Phytochemical profile and antioxidant capacity of the endemic species Bellevalia sasonii Fidan

- In silico molecular modeling and in vitro biological screening of novel benzimidazole-based piperazine derivatives as potential acetylcholinesterase and butyrylcholinesterase inhibitors

- Coenzyme Q10 supplementation affects cellular ionic balance: relevance to aging

- Revolutionizing the probiotic functionality, biochemical activity, antibiotic resistance and specialty genes of Pediococcus acidilactici BCB1H via in-vitro and in-silico approaches

- Synthesis of modified Schiff base appended 1,2,4-triazole hybrids scaffolds: elucidating the in vitro and in silico α-amylase and α-glucosidase inhibitors potential

- Redefining a new frontier in alkaptonuria therapy with AI-driven drug candidate design via in-silico innovation

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Review Articles

- Advancing psoriasis drug delivery through topical liposomes

- Hepatoprotective activity of medicinal plants, their phytochemistry, and safety concerns: a systematic review

- Research Articles

- Phytochemical profile and antioxidant capacity of the endemic species Bellevalia sasonii Fidan

- In silico molecular modeling and in vitro biological screening of novel benzimidazole-based piperazine derivatives as potential acetylcholinesterase and butyrylcholinesterase inhibitors

- Coenzyme Q10 supplementation affects cellular ionic balance: relevance to aging

- Revolutionizing the probiotic functionality, biochemical activity, antibiotic resistance and specialty genes of Pediococcus acidilactici BCB1H via in-vitro and in-silico approaches

- Synthesis of modified Schiff base appended 1,2,4-triazole hybrids scaffolds: elucidating the in vitro and in silico α-amylase and α-glucosidase inhibitors potential

- Redefining a new frontier in alkaptonuria therapy with AI-driven drug candidate design via in-silico innovation