Abstract

Amphidinol 3 (AM3) and theonellamide A (TNM-A) are potent antifungal compounds produced by the dinoflagellate Amphidinium klebsii and the sponge Theonella spp., respectively. Both of these metabolites have been demonstrated to interact with membrane lipids ultimately resulting in a compromised bilayer integrity. In this report, the activity of AM3 and TNM-A in ternary lipid mixtures composed of 1-palmitoyl-2-oleoyl-sn-glycerol-3-phosphocholine (POPC):brain sphingomyelin:cholesterol at a mole ratio of 1:1:1 or 3:1:1 exhibiting lipid rafts coexistence is presented. It was found that AM3 has a more extensive membrane permeabilizing activity compared with TNM-A in these membrane mimics, which was almost complete at 15 μM. The extent of their activity nevertheless is similar to the previously reported binary system of POPC and cholesterol, suggesting that phase separation has neither beneficial nor detrimental effects in their ability to disrupt the lipid bilayer.

1 Introduction

Marine organisms are among the most prolific, and yet still underexplored, sources of novel compounds. The number of new molecules being reported from these sources has increased steadily over the years, to about a thousand each year [1]. Owing to the distinctive environment where these marine natural products are being biosynthesized, a considerable proportion of these has unique structures and properties, usually rendering them with promising bioactivities [2]. In fact, several drug leads of marine origin have either been approved for the treatment of certain medical conditions or are already in various stages of clinical trials [3]. Among the many marine organisms, dinoflagellates and sponges offer great potential to obtain new structures largely because the former are implicated in algal blooms common around the world, while the latter has been traditionally the dominant source of unique marine secondary metabolites. For instance, a recent review of the 2014 literature showed that dinoflagellates and sponges account for 22.5% of the 1378 new marine-derived bioactive compounds reported during this period [1].

Amphidinols (AMs) are a class of polyhydroxy, polyene, antifungal, and hemolytic metabolites first reported in 1991 from the dinoflagellate Amphidinium klebsii found in Japan. Currently, 19 AM homologs have been reported from the same genus [4], [5], [6], [7], [8], [9], [10], [11], [12], in addition to the numerous congeners of this bioactive molecule that have also been isolated [13], [14], [15], [16], [17], including karlotoxins from the harmful algal bloom-implicated dinoflagellate Karlodinium sp. [18]. The defining characteristic of this family of compounds is the presence of two tetrahydropyran rings separating the polyol and polyene regions of the molecule. The antifungal activity of AMs is believed to arise from its ability to permeabilize the membrane, and among the homologues, amphidinol 3 (AM3) (Figure 1) has showed significantly greater antifungal effect. Investigation into the dye leakage capabilities of AM3 in binary lipid membrane mimics showed its absolute dependence on the presence of sterol exhibiting the correct 3β-OH stereochemistry [19], [20], [21]. Furthermore, AM3 activity has been found to be independent of membrane thickness, and coupled with results showing a hairpin configuration of the molecule in the membrane with the polyhydroxy region remaining on the surface while the polyene part penetrating the membrane interior [22], has led to a proposal on the formation of toroidal pores by the compound. However, we have also recently reported that AM3 does not disrupt phospholipid bilayer packing, as what would be expected for toroidal pore formers, so a barrel stave-like mechanism remains a distinct possibility [20].

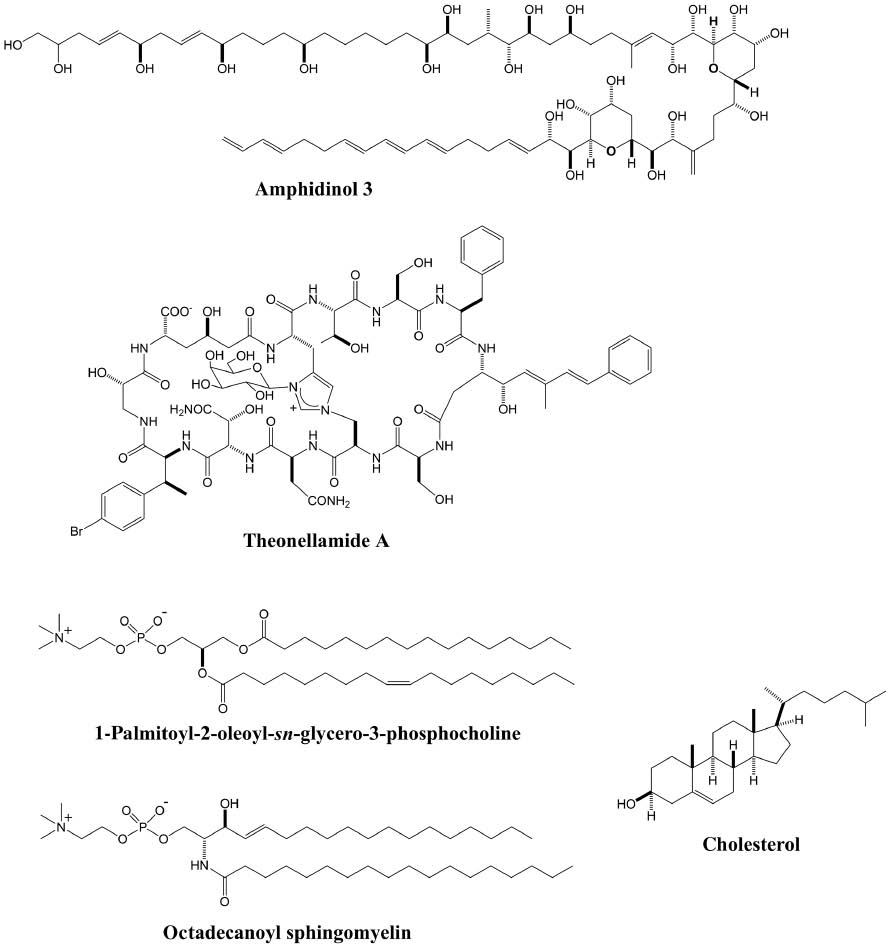

Chemical structures of amphidinol 3, theonellamide A, and lipids used in this study.

Octadecanoyl sphingomyelin is the predominant species of BSM from porcine.

Theonellamides (TNMs) are potent antifungal and cytotoxic metabolites isolated from the marine sponge Theonella spp. These are bicyclic dodecapeptides bridged by a unique histidinoalanine residue, first reported in 1989 with seven homologues known so far [23], [24], [25]. It was previously reported that TNMs specifically recognize 3β-OH sterols ultimately resulting in membrane damage via a mechanism different from the other common antifungal agents [26]. Moreover, these peptides preferentially partition into the liquid disordered domains as well as result in phase separation in biomembrane mimics [27]. Recently, we have also demonstrated the existence of a direct interaction between sterols in membranes and theonellamide A (TNM-A) (Figure 1), where it recognizes the hydroxyl moiety in the shallow region of the membrane [28]. However, unlike AM3, TNM-A does not seem to form pore structures in membranes composed of binary lipid mixtures, apparent from the very weak dye leakage observed, although the peptide induces disruption of the tight packing of the lipid bilayer [29].

Lipid rafts are ordered membrane microdomains believed to play a critical role in the segregation, lateral separation, and order in cell membranes [30], [31]. These structures are enriched in sphingolipids with saturated acyl chains and cholesterol, brought about by the preferential interaction between these two lipids, as well certain proteins that convey upon rafts important biological functions.

In this short communication, the membrane disrupting capabilities of AM3 and TNM-A in raft-forming ternary lipid mixtures containing 1-palmitoyl-2-oleoyl-sn-glycerol-3-phosphocholine (POPC), brain sphingomyelin (BSM), and cholesterol is reported, and compared with the previously published data on activity in membranes that do not exhibit phase separation.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Materials

AM3 was isolated as reported previously [20] while TNM-A was a kind gift from Dr. Shinichi Nishimura of Kyoto University. POPC and BSM were purchased from Avanti Polar Lipids (Alabaster, AL, USA). Cholesterol was obtained from Nacalai Tesque (Kyoto, Japan), while calcein was from Dojindo Laboratories (Kumamoto, Japan). Lipids were used as received and all other chemicals and reagents were standard and analytical quality reagents.

2.2 Preparation of calcein-entrapped liposomes

Large unilamellar vesicles (LUV) exhibiting phase separation were prepared as follows [20]: POPC (5.2 or 7.7 mg), BSM (5 or 2.5 mg), and cholesterol (2.6 or 1.3 mg) were mixed in a round bottom flask with chloroform to prepare mixtures of POPC:BSM:cholesterol at mole ratio of 1:1:1 or 3:1:1. The solution was vigorously mixed, after which the solvent was removed in vacuo to afford a thin lipid film, which was further dried overnight under vacuum. The dried lipid film was then rehydrated with 1 mL of 60 mM calcein (in 10 mM Tris–HCl buffer, pH 7.4, containing 1 mM EDTA and 150 mM NaCl). It was then subjected to two cycles of vortexing (1 min) and warming up (65°C), followed by five cycles of freezing (–20°C) and thawing (65°C) to obtain a suspension of multilamellar vesicles. Afterwards, the suspension was passed through a polycarbonate membrane filter (pore size, 200 nm) 19 times using a Liposofast extruder (Avestin Inc., Ottawa, Canada) to afford LUVs. Unencapsulated calcein was separated from the LUVs by passing the suspension through a Sepharose 4B column equilibrated and eluted with the same Tris–HCl buffer. The phospholipid concentration in the suspension was determined using the Phospholipid C-Test Wako (Wako Pure Chemical Industries Ltd., Osaka, Japan) following the manufacturer’s protocol. Resulting stock solution was stored at 4°C.

2.3 Calcein leakage measurement

Fluorescence measurements of the released calcein were carried out in a JASCO FP 6500 spectrofluorometer (JASCO Corp., Tokyo, Japan) using 490 and 517 nm as the excitation and emission wavelengths, respectively. Briefly, 20 μL of the LUV suspension was mixed with 960 μL of Tris–HCl buffer, then 20 μL of either AM3 or TNM-A was added to obtain the desired metabolite concentration. Fluorescence recordings were measured at 25°C and observed for a total of 5 min. Final lipid concentration in all measurements was 27 μM. To obtain the condition of 100% leakage, 20 μL of 10% Triton X-100 (v/v) in the same Tris–HCl buffer was added to the suspension.

3 Results and discussion

AM3 and TNM-A are two unique marine natural products that have been shown previously to act via a mechanism that involves direct interaction with membrane lipids resulting to a loss of membrane integrity [19], [20], [21], [22], [26], [27], [28], [29]. AM3 shows an absolute dependence in the presence of sterols in order to permeabilize the membrane, which most likely involves the formation of pores. On the other hand, TNM-A does not seem to form distinct membrane pores, although it disrupts the tight packing of the phospholipid bilayer. In these previous investigations of the membrane permeabilizing action by these compounds, only binary lipid mixtures of phospholipids and cholesterol were used. Furthermore, under the conditions where these experiments were performed, such binary lipid mixtures would result in membranes with no phase separation, i.e. it will be only in the liquid-disordered (ld) phase [32].

Ternary mixture of phospholipids, sphingomyelin (or a mixture of saturated and unsaturated phospholipids), and cholesterol has been the canonical model systems to mimic lipid rafts, and has been used extensively to investigate the membrane-disrupting mechanism of action of small molecules, such as antimicrobial peptides [32], [33], [34]. In this study, the mole ratio of POPC:BSM:cholesterol used (1:1:1 and 3:1:1) was previously shown to exhibit the coexistence of both the liquid-orderd (lo) and liquid-disordered (ld) domains [32].

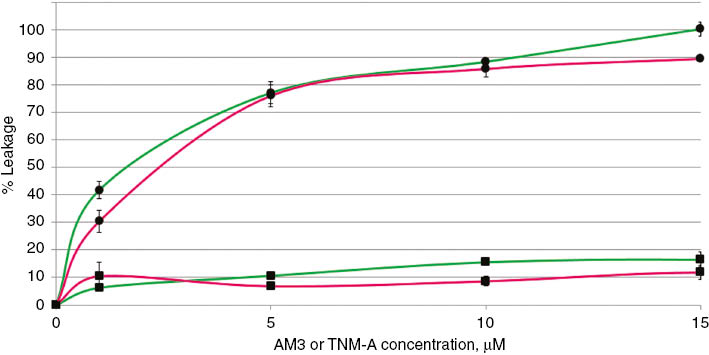

Corresponding liposomes were prepared with an encapsulated calcein, at a dye concentration of 60 mM. At this concentration, calcein fluorescence is quenched, and upon its leakage into the extracellular mileu, for instance, after pore formation, an increase in fluorescence will be observed. Figure 2 shows the % leakage activity of AM3 and TNM-A in raft-forming membrane mimics. AM3 permeabilizing activity is comparable in both lipid systems tested and was almost complete at the highest concentration used (15 μM). This extent of membrane damage is very similar to its activity in binary lipid mixtures consisting of POPC and cholesterol or ergosterol, as we have reported earlier [20]. These results imply that the presence of lo–ld phase separation has neither detrimental nor beneficial effect on the membrane disrupting capabilities of AM3. These findings are different from those observed with other membrane- active compounds such as antimicrobial peptides, whose membrane-disrupting effect is greatly increased in raft-forming membrane due to the preferential accumulation of the peptide in the ld phase leading to more drastic perturbation and subsequent dye leakage [33], [34], although there is no way from the current data to infer on which phase AM3 is colocalized. In addition, the presence of phase separation in membranes necessitates the existence of innate defects found along the interface of such phases, and these have been implicated in better binding and activity observed for certain pore-forming toxins [35]. In contrast, AM3 activity seems unaffected by these packing defects. Nevertheless, since AM3 action is primarily dependent on the presence of sterol, it is possible that the compound is able to recognize cholesterol in both phases, even though it is found deeper in raft domains [36], leading to pore formation. This ability to bind to raft domains has been reported earlier for certain pore-forming protein toxins, where depletion of membrane cholesterol significantly reduced raft binding and pore formation [37].

Calcein leakage from POPC:BSM:cholesterol liposomes after the addition of various concentration of AM3 (circles) or TNM-A (square).

Mole ratio of POPC:BSM:cholesterol used were 1:1:1 (green) and 3:1:1 (pink). Error bars represent standard deviation of three independent trials.

On the other hand, TNM-A shows a very weak dye leakage potential at all concentrations tested, and these activities were comparable to the previous report using binary lipid mixtures of POPC and cholesterol [28]. These data appear to be consistent with our proposal that TNM-A indeed does not form distinct membrane pores [29]. It has been reported earlier that TNM-A recognizes cholesterol in and preferentially partitions into the ld domain [27], which intuitively should result in faster membrane accumulation compared with lipid mixtures exhibiting no phase separation. In addition, we have demonstrated before, through surface plasmon resonance experiments that rate constants for TNM-A binding to ergosterol- or cholesterol-containing POPC membranes were about 10 times larger than in sterol free ones, which results in faster and greater accumulation in the former [28]. However, considering that the TNM-A activity is comparable on both types of lipid bilayers [28] and observed on the same time course suggests that the rate of peptide accumulation may not be significantly enhanced by domain formation.

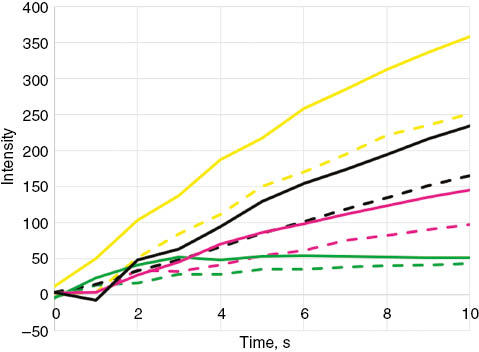

Even though no significant difference was observed in the activity of AM3 in the two raft-forming membrane mimics, a closer look at the time course fluorescence in these systems may provide additional insights into initial association rates of the compound. Figure 3 shows the average time course plots of calcein fluorescence (three independent trials) within 10 s after AM3 addition. In all concentration tested, dye fluorescence was stronger in the 3:1:1 ternary lipid mixture. Since dye fluorescence is directly related to amount of released dye, a higher fluorescence indicates a more substantial disruption of the bilayer integrity. It is therefore reasonable to suggest that more AM3 are membrane bound during the first few moments of contact between AM3 and the 3:1:1 membrane, and concomitantly a relatively faster rate of accumulation in this system. A possible explanation for this is that since the lo phase predominates in the 1:1:1 system [33], AM3 will have an easier time interacting with cholesterol in the 3:1:1 membrane mixture due the greater area of ld phase, which is loosely packed, present in this system.

Time course plots of calcein fluorescence within 10 s after the addition of AM3 to POPC:BSM:cholesterol liposomes.

Concentration of AM3 used were 15 μM (yellow), 10 μM (black), 5 μM (pink), and 1 μM (green). Mole ratio of POPC:BSM:cholesterol used were 1:1:1 (dashed lines) and 3:1:1 (solid lines). Lines show the average of three independent trials.

4 Conclusions

To summarize, AM3 showed a significantly greater dye leakage activity in ternary lipid mixtures exhibiting phase separation than TNM-A, which was comparable to the compounds’ previously reported activity in binary mixtures without lo–ld segregation [20], [28]. This demonstrates that for AM3, at least, its membrane permeabilizing capability is not dependent on whether lipid rafts form or not. It also appears that AM3 has a better initial interaction with ternary lipid mixtures where lo does not predominate. Notwithstanding, further experiments will have to be performed to analyze the interaction of both AM3 and TNM-A in raft-forming lipid bilayers, such as the kinetics involved in the binding of the compounds to these systems as well as whether or not cholesterol is also recognized in these kinds of membrane mimics.

Acknowledgments:

The author wishes to express his gratitude to Prof. Michio Murata (Osaka University) and Prof. Nobuaki Matsumori (Kyushu University) for critical discussion, and to Dr. Shinichi Nishimura (Kyoto University) for providing the TNM-A sample.

References

1. Blunt JW, Copp BR, Keyzers RA, Munro MH, Prinsep M. Marine natural products. Nat Prod Rep 2016;33:382–431.10.1039/C5NP00156KSearch in Google Scholar

2. Yiwen H, Guping H, Jianchen Y, Yongcheng L, Shengping C, Jie Y, et al. Statistical research on the bioactivity of new marine natural products discovered during the 28 years from 1985 to 2012. Mar Drugs 2015;13:202–21.10.3390/md13010202Search in Google Scholar

3. Montaser R, Luesch H. Marine natural products: a new wave of drugs? Future Med Chem 2011;3:1475–89.10.4155/fmc.11.118Search in Google Scholar

4. Satake M, Murata M, Yasumoto T, Fujita T, Naoki H. Amphidinol, a polyhydroxy-polyene antifungal agent with an unprecedented structure, from a marine dinoflagellate, Amphidinium klebsii. J Am Chem Soc 1991;113:9859–61.10.1021/ja00026a027Search in Google Scholar

5. Paul GK, Matsumori N, Murata M, Tachibana K. Isolation and chemical structure of amphidinol 2, a potent haemolytic compound from marine dinoflagellate Amphidinium klebsii. Tetrahedron Lett 1995;36:6279–82.10.1016/0040-4039(95)01259-KSearch in Google Scholar

6. Paul GK, Matsumori N, Konoki K, Murata M, Tachibana K. Chemical structures of amphidinols 5 and 6 isolated from marine dinoflagellate Amphidinium klebsii and their cholesterol-dependent membrane disruption. J Mar Biotechnol 1997;5:124–8.Search in Google Scholar

7. Murata M, Matsuoka S, Matsumori N, Paul GK, Tachibana K. Absolute configuration of amphidinol 3, the first complete structure determination from amphidinol homologues: application of a new configuration analysis based on carbon-hydrogen spin-coupling constants. J Am Chem Soc 1999:121:870–71.10.1021/ja983655xSearch in Google Scholar

8. Morsy N, Matsuoka S, Houdai T, Matsumori N, Adachi S, Murata M, et al. Isolation and structure elucidation of a new amphidinol with a truncated polyhydroxyl chain from Amphidinium klebsii. Tetrahedron 2005;61:8606–10.10.1016/j.tet.2005.07.004Search in Google Scholar

9. Echigoya R, Rhodes L, Oshima Y, Satake M. The structures of five new antifungal and haemolytic amphidinol analogs from Amphidinium carterae Collected in New Zealand. Harmful Algae 2005;4:383–9.10.1016/j.hal.2004.07.004Search in Google Scholar

10. Morsy N, Houdai T, Matsuoka S, Matsumori N, Adachi S, Oishi T, et al. Structures of new amphidinols with truncated polyhydroxyl chain and their membrane-permeabilizing activities. Bioorg Med Chem 2006;14:6548–54.10.1016/j.bmc.2006.06.012Search in Google Scholar PubMed

11. Meng Y, Van Wagoner RM, Misner I, Tomas C, Wright JL. Structure and biosynthesis of amphidinol 17, a haemolytic compound from Amphidinium carterae. J Nat Prod 2010;73:409–15.10.1021/np900616qSearch in Google Scholar PubMed

12. Nuzzo G, Cutignano A, Sardo A, Fontana A. Antifungal amphidinol 18 and its 7-sulfate derivative from the marine dinoflagellate Amphidinium carterae. J Nat Prod 2014;77:1524–7.10.1021/np500275xSearch in Google Scholar PubMed

13. Doi Y, Ishibashi M, Nakamichi H, Kosaka T, Ishikawa T, Kobayashi J, et al. A new polyhydroxyl compound from symbiotic marine dinoflagellate Amphidinium sp. J Org Chem 1997;62:3820–3.10.1021/jo970273lSearch in Google Scholar

14. Huang X, Zhao D, Guo Y, Wu H, Trivellone E, Cimino G. Lingshuiols A and B, two new polyhydroxy compounds from the chinese marine dinoflagellate Amphidinium sp. Tetrahedron Lett 2004;45:5501–4.10.1016/j.tetlet.2004.05.067Search in Google Scholar

15. Washida K, Koyama T, Yamada K, Kita M, Uemura D. Karatungiols A and B, two novel antimicrobial polyol compounds, from the symbiotic marine dinoflagellate Amphidinium sp. Tetrahedron Lett 2006;47:2521–5.10.1016/j.tetlet.2006.02.045Search in Google Scholar

16. Sugahara K, Kitamura Y, Murata M, Satake M, Tachibana K. Prorocentrol, a polyoxy linear carbon chain compound isolated from the toxic dinoflagellate Prorocentrum hoffmannianum. J Org Chem 2011;76:3131–8.10.1021/jo102585kSearch in Google Scholar PubMed

17. Inuzuka T, Yamada K, Uemura D. Amdigenols E and G, long carbon-chain polyol compounds, isolated from the marine dinoflagellate Amphidinium sp. Tetrahedron Lett 2014;55:6319–23.10.1016/j.tetlet.2014.09.094Search in Google Scholar

18. Waters AL, Oh J, Place AR, Hamann MT. Stereochemical studies of the karlotoxin class using NMR spectroscopy and DP-4 chemical-shift analysis: insights into their mechanism of action. Angew Chem 2015;54:15705–10.10.1002/anie.201507418Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

19. Morsy N, Houdai T, Konoki K, Matsumori N, Osihi T, Murata M. Effects of membrane constituents on membrane-permeabilizing activity of amphidinols. Bioorg Med Chem 2008;16:3084–90.10.1016/j.bmc.2007.12.029Search in Google Scholar PubMed

20. Espiritu RA, Matsumori N, Tsuda M, Murata M. Direct and stereospecific interaction of amphidinol 3 with sterol in lipid bilayers. Biochemistry 2014;53:3287–93.10.1021/bi5002932Search in Google Scholar PubMed

21. Swasono RT, Mouri R, Morsy N, Matsumori N, Oishi T, Murata M. Sterol effect on interaction between amphidinol 3 and liposomal membrane as evidenced by surface plasmon resonance. Bioorg Med Chem Lett 2010;20:2215–8.10.1016/j.bmcl.2010.02.025Search in Google Scholar PubMed

22. Houdai T, Matsumori N, Murata M. Structure of membrane-bound amphidinol 3 in isotropic small bicelles. Org Lett 2008;10:4191–4.10.1021/ol8016337Search in Google Scholar PubMed

23. Matsunaga S, Fusetani N, Hashimoto K, Walchli M, Theonellamide F. A novel antifungal bicyclic peptide from a marine sponge Theonella sp. J Am Chem Soc 1989;111:2582–8.10.1021/ja00189a035Search in Google Scholar

24. Matsunaga S, Fusetani N. Theonellamide A-E, cytotoxic bicyclic peptides, from a marine sponge Theonella sp. J Org Chem 1995;60:1177–81.10.1021/jo00110a020Search in Google Scholar

25. Youssef DT, Shaala LA, Mohamed GA, Badr JM, Bamanie FH, Ibrahim SR. Theonellamide G, a potent antifungal and cytotoxic bicyclic glycopeptide from the red sea marine sponge Theonella swinhoei. Mar Drugs 2014;12:1911–23.10.3390/md12041911Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

26. Nishimura S, Arita Y, Honda M, Iwamoto K, Matsuyama A, Shirai A, et al. Marine antifungal theonellamides target 3β-hydroxysterols to activate rho1 signalling. Nat Chem Biol 2010;6:519–26.10.1038/nchembio.387Search in Google Scholar PubMed

27. Arita Y, Nishimura S, Ishitsuka R, Kishimoto T, Ikenouchi J, Ishii K, et al. Targeting cholesterol in a liquid-disordered environment by theonellamides modulate cell membrane order and cell shape. Chem Biol 2015;22:1–7.10.1016/j.chembiol.2015.04.011Search in Google Scholar PubMed

28. Espiritu RA, Matsumori N, Murata M, Nishimura S, Kakeya H, Matsunaga S, et al. Interaction between the marine sponge cyclic peptide theonellamide a and sterols in lipid bilayers as viewed by surface plasmon resonance and solid-state 2H nuclear magnetic resonance. Biochemistry 2013;52:2410–18.10.1021/bi4000854Search in Google Scholar PubMed

29. Espiritu RA, Cornelio K, Kinoshita M, Matsumori N, Murata M, Nishimura S, et al. Marine sponge cyclic peptide theonellamide A disrupts lipid bilayer integrity without forming distinct membrane pores. Biochim Biophys Acta 2016;1858:1373–9.10.1016/j.bbamem.2016.03.019Search in Google Scholar PubMed

30. Simons K, Ikonen E. Functional rafts in cell membranes. Nature 1997;387:569–72.10.1038/42408Search in Google Scholar PubMed

31. Lingwood D, Simons K. Lipid rafts as a membrane-organizing principle. Science 2010;327:46–50.10.1126/science.1174621Search in Google Scholar PubMed

32. de Almeida RF, Fedorov A, Prieto M. Sphingomyelin/phosphatidylcholine/cholesterol phase diagram: boundaries and composition of lipid rafts. Biophys J 2003;85:2406–16.10.1016/S0006-3495(03)74664-5Search in Google Scholar

33. McHenry AJ, Sciacca MF, Brender JR, Ramamoorthy A. Does cholesterol suppress the antimicrobial peptide induced disruption of lipid raft containing membranes? Biochim Biophys Acta 2012;1818:3019–24.10.1016/j.bbamem.2012.07.021Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

34. Losada-Perez P, Khorshid M, Hermans C, Robijns T, Peeters M, Jimenez-Monroy KL, et al. Melittin disruption of raft and non-raft-forming biomimetic membranes: a study by quartz crystal microbalance with dissipation monitoring. Colloids Surf B Biointerfaces 2014;123:938–44.10.1016/j.colsurfb.2014.10.048Search in Google Scholar PubMed

35. Ros U, Edwards MA, Epand RF, Lanio ME, Schreier S, Yip CM, et al. The sticholysin family of pore-forming toxins induces the mixing of lipids in membrane domains. Biochim Biophys Acta 2013;1828:2757–62.10.1016/j.bbamem.2013.08.001Search in Google Scholar PubMed

36. Rog T, Pasenkiewicz-Gierula M. Cholesterol-sphingomyelin interactions: a molecular dynamics simulation study. Biophys J 2006;91:3756–67.10.1529/biophysj.106.080887Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

37. Nagahama M, Hayashi S, Morimitsu S, Sakurai J. Biological activities and pore formation of Clostridium perfringens beta toxin in hl 60 cells. J Biol Chem 2003;278:36934–41.10.1074/jbc.M306562200Search in Google Scholar PubMed

©2017 Walter de Gruyter GmbH, Berlin/Boston

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Review Article

- Structural diversity in echinocandin biosynthesis: the impact of oxidation steps and approaches toward an evolutionary explanation

- Research Articles

- Cytotoxic constituents of Alocasia macrorrhiza

- Isolation, antimicrobial and antitumor activities of a new polyhydroxysteroid and a new diterpenoid from the soft coral Xenia umbellata

- Volatile oil profile of some lamiaceous plants growing in Saudi Arabia and their biological activities

- Membrane permeabilizing action of amphidinol 3 and theonellamide A in raft-forming lipid mixtures

- Discovery and preliminary structure-activity relationship of the marine natural product manzamines as herpes simplex virus type-1 inhibitors

- NMR reassignment of stictic acid isolated from a Sumatran lichen Stereocaulon montagneanum (Stereocaulaceae) with superoxide anion scavenging activities

- Simultaneous formulation of terbinafine and salvia monoterpenes into chitosan hydrogel with testing biological activity of corresponding dialysates against C. albicans yeast

- Rapid Communication

- Chemical constituents of the leaves of Campylospermum elongatum

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Review Article

- Structural diversity in echinocandin biosynthesis: the impact of oxidation steps and approaches toward an evolutionary explanation

- Research Articles

- Cytotoxic constituents of Alocasia macrorrhiza

- Isolation, antimicrobial and antitumor activities of a new polyhydroxysteroid and a new diterpenoid from the soft coral Xenia umbellata

- Volatile oil profile of some lamiaceous plants growing in Saudi Arabia and their biological activities

- Membrane permeabilizing action of amphidinol 3 and theonellamide A in raft-forming lipid mixtures

- Discovery and preliminary structure-activity relationship of the marine natural product manzamines as herpes simplex virus type-1 inhibitors

- NMR reassignment of stictic acid isolated from a Sumatran lichen Stereocaulon montagneanum (Stereocaulaceae) with superoxide anion scavenging activities

- Simultaneous formulation of terbinafine and salvia monoterpenes into chitosan hydrogel with testing biological activity of corresponding dialysates against C. albicans yeast

- Rapid Communication

- Chemical constituents of the leaves of Campylospermum elongatum