Isolation, antimicrobial and antitumor activities of a new polyhydroxysteroid and a new diterpenoid from the soft coral Xenia umbellata

-

Seif-Eldin N. Ayyad

, Khalid O. Al-Footy

Abstract

A new C-30 steroid, 3β-,5α-,6β-,11α-,20β-pentahydroxygorgosterol (1), and a new diterpenoid, xeniumbellal (2), along with three known aromadendrane-type sesquiterpenes, aromadendrene (3), palustrol (4) and viridiflorol (5), were isolated from the soft coral Xenia umbellata. Chemical structures were determined by analyzing their NMR and MS data. The antimicrobial and antitumor activities of the isolated compounds were examined. Both 1 and 2 showed moderate antibacterial activities, especially against the multidrug-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii (MIC 0.22 and 0.28 mM, respectively); while 2 showed antitumor activity against a lymphoma cell line with LD50 0.57 mM and was nontoxic to Artemia salina at all tested concentrations up to about 4 mM.

1 Introduction

In recent years, the search for and use of dietary supplements and drugs derived from marine organisms have accelerated. Marine animals, including soft corals, are known to provide natural compounds with great significance in medicinal applications [1], [2]. Soft corals of the genus Xenia (Alcyoniidae) are a proliferative source of bioactive diterpenoids having a nine-membered ring structure [3], [4], [5], [6]. Five groups of this class of diterpenoids were differentiated: xenicins, xeniolides, xeniaphyllanes, xeniaethers and azamilides [7]. These terpenoid compounds showed appreciable antitumor, antibacterial, and antifungal activities [5], [6], [7], [8].

In the course of our research program aimed at the discovery of bioactive and/or new metabolites from marine organisms, the constituents of the shallow water Red Sea soft coral Xenia umbellata Lamarck (Family Alcyoniidae, Order Alcyonacea, subclass Octocorallia, class Anthozoa, phylum Coelenterata) were investigated.

2 Experimental

2.1 General

Silica gel GF 254 (Merck, Darmstadt, Germany) was used for analytical thin layer chromatography (TLC). Preparative thin layer chromatography (PTLC) was performed on aluminum oxide plates (20×20 cm) of 250 µm thickness. Electron impact mass spectra were determined at 70 eV on a Kratos (Manchester, UK) MS-25 instrument. 1D and 2D NMR spectra were recorded by using Bruker (Karlsruhe, Germany) AVANCE III WM 600 MHz spectrometers and 13C NMR at 150 MHz. Tetramethylsilane (TMS) was used as internal standard. Plates were sprayed with 50%-sulfuric acid in methanol and heated at 100 °C for 1–2 min.

2.2 Collection and processing of the Xenia species

The marine invertebrate X. umbellata Lamarck had been collected using scuba at a depth of 5–10 m in November 2012 off the Red Sea Coast at Jeddah, Saudi Arabia, and was identified by Dr. Mohsen El-Sherbiny [Faculty of Marine Sciences, King Abdulaziz University (KAU), Jeddah, Saudi Arabia]. The collected animal was immediately frozen and lyophilized (VIRITIS Benchtop 4K; Millrock Technol., Kingston, NY, USA) until dryness and then extracted. A voucher specimen (XC-2012-11) was deposited in the Faculty of Marine Sciences of KAU.

About 50 g of the dried soft coral material was extracted three times by an equal mixture of CH2Cl2 and MeOH at room temperature, and the obtained extract was concentrated under vacuum to yield a brown gummy material (14.4 g).

2.3 Isolation and identification of compounds

The residue (14.4 g) was homogenized with silica gel (30 g) and then subjected to chromatography on a Si-gel open column (500 g, 75×2 cm) for separation of the constituents. n-Hexane was used as an eluent and the polarity was increased by increasing amounts of EtOAc. Fractions of 50 ml were collected. The course of fractionation was monitored by TLC with the aid of both UV light and spray reagent. Preparative TLC (PTLC) was used to isolate individual compounds.

2.3.1 3β-,5α-,6β-,11α-,20β-Pentahydroxygorgosterol (1)

The fraction eluted by n-hexane: EtOAc (4:6, v/v) (Rf=0.13, 65.0 mg) was subjected to PTLC using a mixture of CHCl3/MeOH (8.5:1.5). The band with Rf=0.68 (blue color with spray reagent) gave a white powder (10.4 mg); mp>300 °C; [α]D=−41.4 (MeOH; c=0.22); IR νmax (neat) cm−1: 3392 (br), 2956, 1036; EIMS (70 eV) m/z (rel. int.): 474 (62) [M+-H2O], 456 (95) [M+-2H2O], 438 (70) [M+-2H2O], 426 (50), 408 (40), 377 (100), 281 (25), 129 (80), 57 (100); HRESI-MS data m/z 492.3804 [M]+ (calculated for C30H52O5 492.3815); 1H, 13C NMR (Table 1).

NMR spectral data of compounds 1 and 2 in CDCl3 (δ, ppm, J, Hz).a

| Carbon No. | 1 | Carbon No. | 2 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| δ 1H (m, J, Hz) | δ13Cb | δ 1H (m, J, Hz) | δ13C | ||

| 1 | 1.72 (m) | 35.5 | 1 | 3.23 (ddd, 12, 2.4, 1.2) | 63.2 |

| 1.48 (m) | 3.07 (m) | ||||

| 2 | 1.45 (m) | 32.4 | 3 | 9.43 (d, 2.4) | 195.0 |

| 1.66 (m) | – | 4 | – | 141.8 | |

| 3 | 3.97 (dddd, 10.8, 10.8, 6.6, 4.8) | 67.3 | 4a | 3.51 (dd, 11.4, 8.4) | 33.2 |

| 4 | 2.07 (m) | 42.5 | 5 | 2.16 (m) | 30.5 |

| 1.10 (m) | |||||

| 1.52 (m) | 6 | 2.78 (m) | 26.6 | ||

| 2.36 | |||||

| 5 | – | 79.0 | 7 | – | 55.7 |

| 6 | 3.48 (brs) | 76.3 | 8 | 2.95 (d, 4.2) | 58.4 |

| 7 | 2.10 (m) | 34.9 | 9 | 3.20 (dt, 11.2, 4.2) | 59.2 |

| 1.82 (m) | |||||

| 8 | 1.57 (m) | 32.8 | 10 | 2.72 (dd, 13.8, 11.2) | 27.6 |

| 2.54 (dd, 13.8, 3.6) | |||||

| 9 | 1.21 (m) | 52.8 | 11 | – | 143.7 |

| 10 | – | 40.5 | 11a | 3.21 (dt, 11.4, 4.2) | 51.7 |

| 11 | 3.81 (ddd, 10.8, 10.8, 4.8) | 68.6 | 12 | 6.95 (d, 11.4) | 152.7 |

| 12 | 2.26 (dd, 12.0, 4.8) | 13 | 7.10 (dd, 15, 11.4) | 122.4 | |

| 1.50 (m) | 52.8 | 14 | 6.39 (d, 15) | 122.5 | |

| 13 | – | 44.2 | 15 | – | 71.5 |

| 14 | 1.15 (m) | 56.1 | 16 | 1.40 (s) | 29.5 |

| 15 | 1.58 (m) | 25.2 | 17 | 1.39 (s) | 29.5 |

| 1.03 (m) | 18 | 3.48 (d, 4.8) | 54.4 | ||

| 3.17 (d, 4.8) | |||||

| 16 | 1.38 (m) | 29.1 | 19 | 5.34 (br s) | 120.0 |

| 5.33 (br s) | |||||

| 1.27 (m) | |||||

| 17 | 1.29 (m) | 58.8 | |||

| 18 | 0.69 (s) | 13.4 | |||

| 19 | 1.25 (s) | 17.3 | |||

| 20 | – | 76.6 | |||

| 21 | 1.02 (s) | 21.5 | |||

| 22 | 0.19 (ddd, 11.4, 9, 6) | 32.7 | |||

| 23 | – | 26.3 | |||

| 24 | 0.25 (m) | 51.5 | |||

| 25 | – | 32.7 | |||

| 26 | 0.95 (d, 6.6) | 22.4 | |||

| 27 | 0.85 (d, 6.6) | 21.7 | |||

| 28 | 0.85 (d, 6.6) | 15.9 | |||

| 29 | 0.43 (dd, 9, 5.4), −0.10 (dd, −9, −4.8) | 14.5 | |||

| 30 | 0.91 (s) | 21.8 | |||

aAll assignments are based on 1D and 2D measurements (HMBC, HSQC, COSY). bImplied multiplicities were determined by DEPT (C=s, CH=d, CH2=t).

2.3.2 Xeniumbellal (2)

Another fraction eluted by n-hexane: EtOAc (4:6), (Rf=0.50, 89.3 mg) was subjected to PTLC using a mixture of CHCl3/MeOH (9.5:0.5). A blue band (with spray reagent) at Rf=0.30 yielded oily material (36.0 mg); [α]D=+51.0 (CHCl3; c=0.05); IR νmax (neat) cm−1: 3440, 3059, 2924, 1699, 1635, 1264, 731; HRESI-MS data m/z 348.1927 [M]+ (calculated for C20H28O5 348.1937); 1H, 13C NMR (Table 1).

2.3.3 Aromadendrene (3)

The fraction eluted with n-hexane, Rf=0.98 (16.1 mg) was re-purified by PTLC. The violet band (with spray reagent) at Rf=0.90 gave a pale yellow oil (9.3 mg). Compound 3 was identified as aromadendrene by comparison of its spectral data with those in the literature [9].

2.3.4 Palustrol (4)

The fraction eluted by n-hexane/ethylacetate (9:1), Rf=0.80 (240.9 mg) was re-purified by PTLC using the solvent system n-hexane/ethylacetate (8:2). The brown band (with spray reagent) at Rf=0.74 gave a colorless oil (124.5 mg). Compound 4 was identified as palustrol by comparison of its spectral data with those in the literature [10].

2.3.5 Viridiflorol (5)

The fraction eluted by n-hexane/ethylacetate (9:1), Rf=0.49 (40.0 mg) was re-purified by PTLC using the solvent system n-hexane/ethylacetate (8:2). The brown band (with spray reagent) at Rf=0.56 gave a white crystalline material (22.7 mg). Compound 5 was identified as viridiflorol by comparison of its spectral data with those in the literature [11].

2.4 Biological activities

2.4.1 Antimicrobail activity

The examined Gram-negative bacteria were Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Escherichia coli¸ Klebsiella pneumoniae, and Acinetobacter baumannii, while the Gram-positive bacteria were Staphylococcus aureus, Staphylococcus epidermidis and Streptococcus pneumoniae. All the tested bacterial isolates were obtained from King Fahd General Hospital, Jeddah, Saudi Arabia. Candida albicans and Asperigillus niger were from the culture collection of the Microbiology Department, Faculty of Science, KAU.

The agar well diffusion method [12] was used to determine the sensitivity of the pathogenic bacteria and fungi to the five isolated products (1–5). Over the surface of Mueller–Hinton agar, 0.5 ml of the bacterial suspension (4×106 CFU/ml) was spread and agar wells (6-mm diameter) were filled with 50 µl of the tested material (10 µg/ml DMSO). On Sabouraud agar or potato dextrose agar, yeast cells or fungal spore suspensions containing 4×104 CFU/ml were spread over the agar surface. After an hour of incubation at room temperature, the inoculated plates were incubated for 24 h at 37 °C for bacteria and 25 °C for 4 days for the fungi. Inhibition zone diameters were measured and the mean diameter of three replicates (mean ± SD) was calculated. Ampicillin trihydrate and amphotericin B were used as positive controls for bacteria and fungi, respectively, and DMSO was used as negative control.

The method of Chand et al. [13] modified by Aly and Gumgumjee [14] was used to determine the minimal inhibitory concentrations (MICs) of the active factions against the tested bacteria and fungi.

2.4.2 Lethality assay

The toxicity of the five isolated products (1–5) was determined using the brine shrimp lethality test [15].

2.4.3 Antitumor activity

The antitumor activity of the five isolated products (1–5) was determined against two cell lines, Ehrlich carcinoma and lymphoma obtained from NCI, Tanta, Egypt, which were cultured in RPMI 1640 medium (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) with 10% fetal calf serum (Gibco, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Carlsbad, CA, USA) at 37 °C for 48 h under a humidified atmosphere air containing 5% CO2 [16]. Then, the cells were collected, incubated for 24 h with different concentrations of the respective compound, centrifuged at 1500 g for 2 min, and after removing the supernatant, cells were counted in a hemacytometer and cell viability was assessed with trypan blue (Sigma-Aldrich) according to [17]. The dose lethal to 50% of the cells (LD50) was calculated. Bleomycin was used as positive control.

3 Results and discussion

The CHCl3-soluble fraction of the CH2Cl2/MeOH extract of the soft coral X. umbellate was fractionated on a silica gel column. Similar fractions were combined and purified using PTLC.

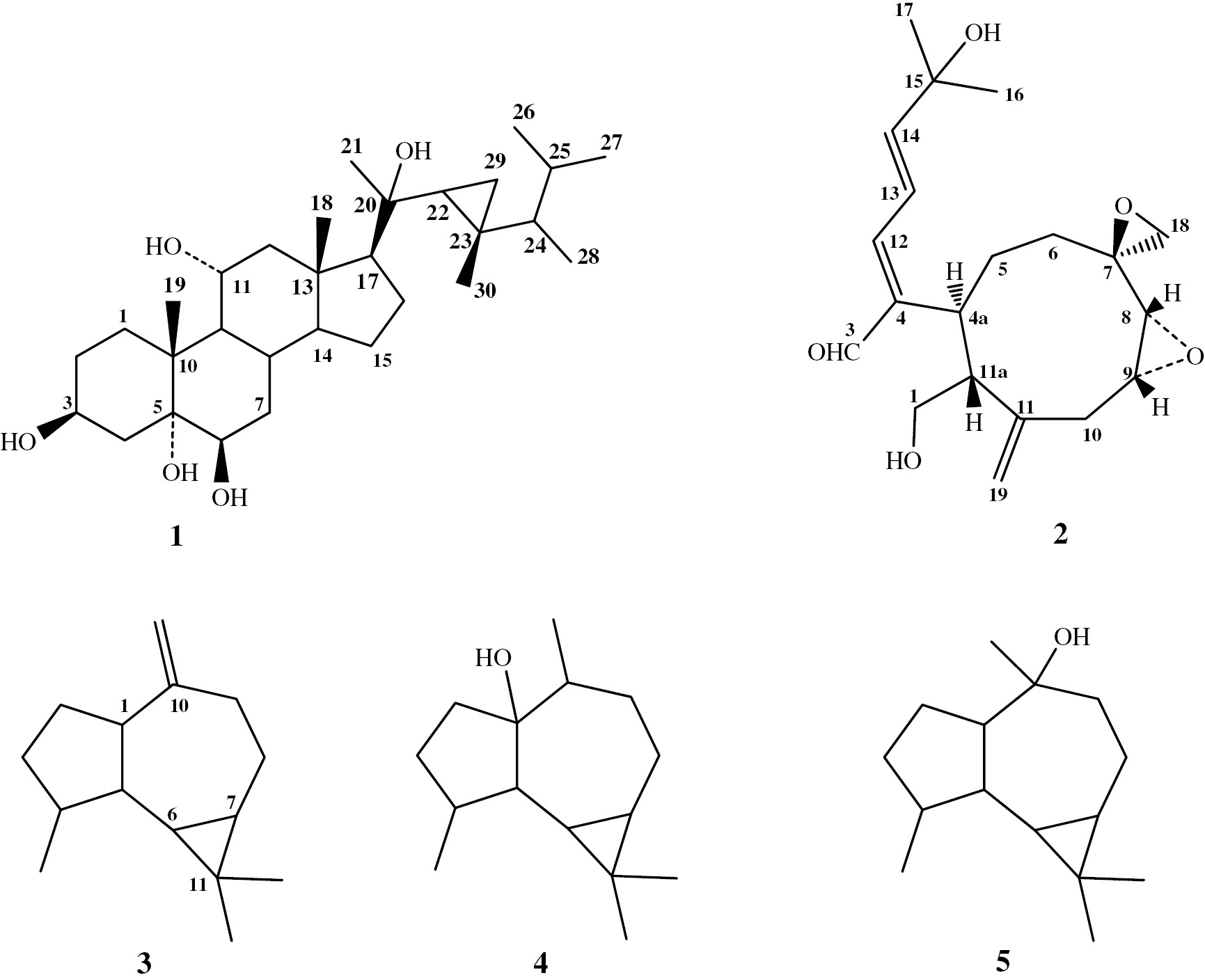

Two new metabolites from this marine organism were identified: the polyhydroxysteroid 3β-,5α-,6β-,11α-, 20β-pentahydroxygorgosterol (1) and the diterpenoid xeniumbellal (2), which were isolated along with three known sesquiterpenes (3–5) (Figure 1).

Compounds isolated from the soft coral Xenia umbellate.

Compound 1 was isolated as a white powder and was assigned the molecular composition C30H52O5 indicated by mass measurement (HREIMS m/z 492.3804, calculated 492.3815), implying five unsaturation sites. The consecutive appearance of fragment ions separated by 18 mass units from the parent peak indicates the existence of hydroxyl functions. The IR absorption spectrum showed a broad band at 3392 cm−1, supporting the presence of the hydroxyl function. The 13C NMR spectra of 1indicated resonances for 30 carbons, categorized by a DEPT NMR experiment into 7 CH3, 9 CH2, 10 CH and four non-protonated carbons (Table 1).

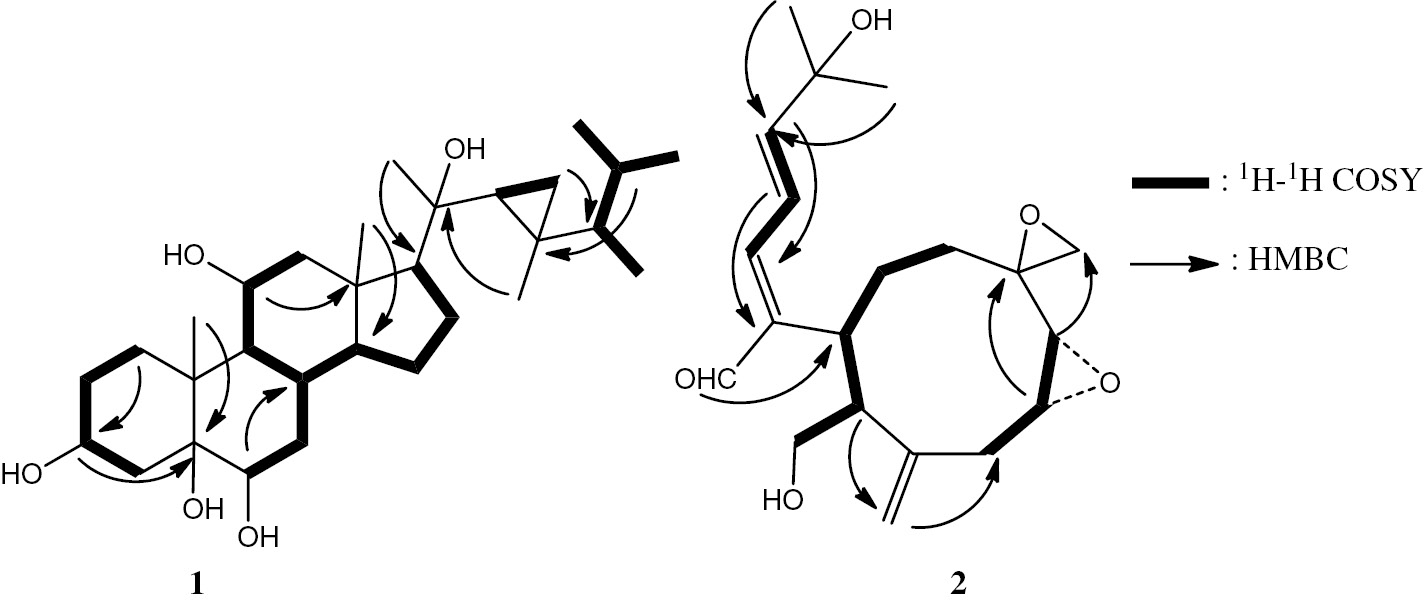

No signals were observed in the downfield region of the 13C NMR spectrum, which favored the presence of a pentacyclic carbon skeleton. The 1H and 13C NMR spectra showed the presence of seven methyl groups; three doublets resonating at δH/δC 0.95/22.4, δH/δC 0.95/15.9, and δH/δC 0.85/21.0, and four singlets resonating at δH/δC 1.25/17.3, δH/δC 1.02/21.5, δH/δC 0.91/14.5, and δH/δC 0.68/13.4. Such a methylation pattern can be attributed to a steroidal nucleus [18]. The 1H NMR spectrum exhibited signals in its upfield region (δH=−0.1 to 0.43 ppm), which were unambiguously ascribed to a cyclopropane-bearing gorgosterol-type side chain resonating at δH 0.43 (dd, 9.0, 5.4 Hz), δH 0.19 (dd, 11.4, 9.6) and δH −0.10 (dd, 9.0, 4.8). This information, together with the methylation pattern and several other features appearing in the 1D and 2D NMR spectra (Table 1), suggested a gorgosterol-type sterol. The presence and nature of five hydroxyl functionalities were revealed from 13C NMR, DEPT and HSQC spectra, where signals due to five oxygenated carbons [δH 79.0 (s), 76.6 (s), 76.3 (d), 68.6 (d), and 67.3 (d)] were noticed. The methine proton resonating at δH 3.97 (dddd, 10.8, 10.8, 6.6, and 4.8 Hz) should be located at C-3, since this is the only available position flanked by two methylene groups. H-H COSY and HSQC spectra established the positions of the other hydroxyl groups; H-3 is correlated with the quaternary carbon at δC 79.0, and this carbon is also correlated with the proton resonating at δH 3.48 (brs), which implies that positions 5 and 6 are both hydroxylated (Figure 2). The position of the fourth hydroxyl group was concluded by observing the proton resonating at δH 3.81, which appeared as doublet of doublet of doublets with J values of 10.8, 10.8, and 10.8 Hz. This proton could be located at several positions within the carbon skeleton, but owing to the HMBC correlations (Figure 2) between this proton and the two quaternary carbons assigned to C-10 and C-13, we were able to locate the OH group at C-11.

Selected 1H-1H COSY and HMBC correlations of 1 and 2.

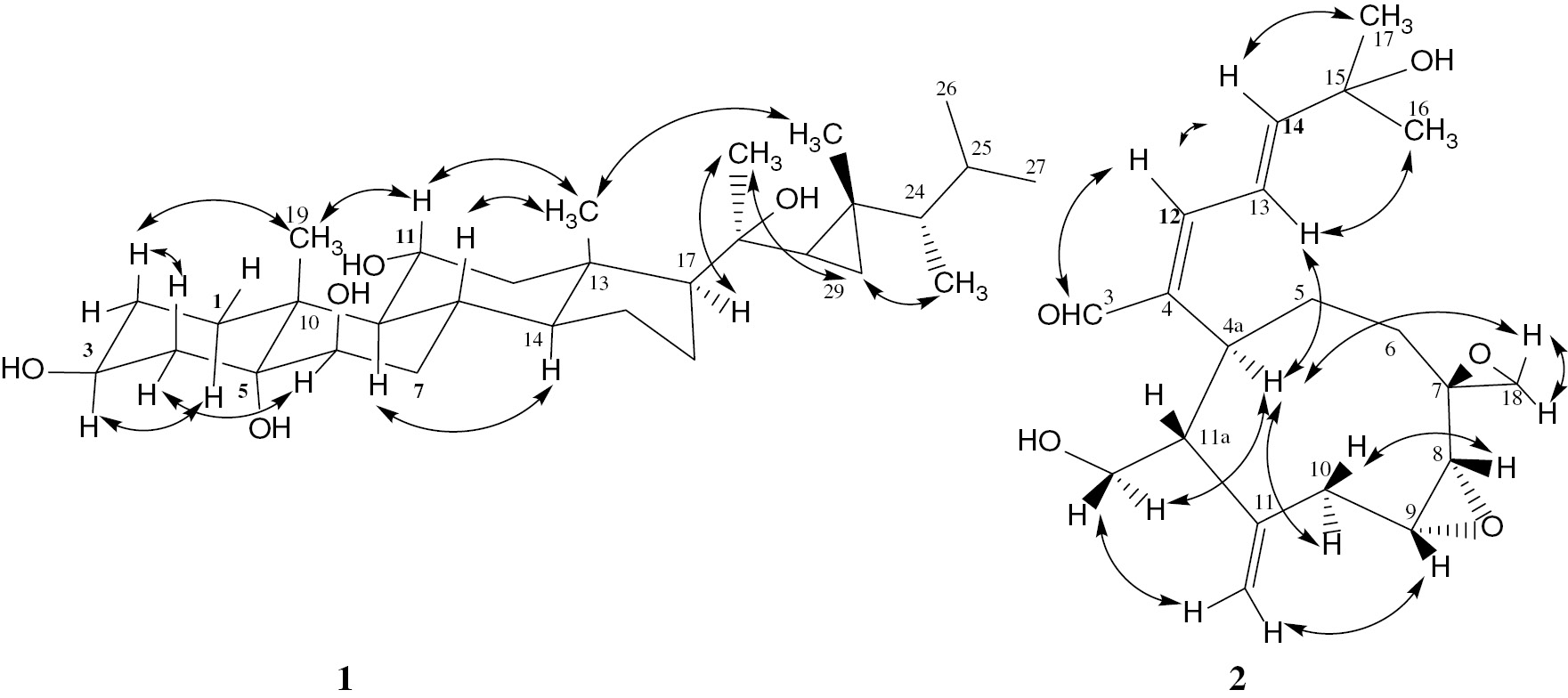

The position of the fifth OH group was deduced to be at C-20 from the HMBC correlations between the upfield protons assigned to the cyclopropanyl moiety and the signal at δC 76.6 together with the disappearance of the signal due to Me-21 frequently encountered in steroids. These conclusions were further supported by comparison of our data with those in the literature [19]. The stereochemistry of the hydroxyl groups was deduced from the values of the coupling constant and also from the NOE correlations with the well-established β−orientation of the two methyls Me-18 and Me-19, to be 3β-,5α-,6β-,11α-, 20β- (Figure 3). Hence, compound 1 can be assigned as 3β-,5α-,6β-,11α-,20β-pentahydroxygorgosterol.

Selected NOESY correlations of 1 and 2.

Compound 2 was isolated as an optically active colorless oil [a]D21+51 (c 0.05, CHCl3). It was assigned the molecular composition C20H28O5 indicated by mass measurement (HREIMS m/z 348.1927, calculated 348.1937), implying seven unsaturation sites. The IR spectrum showed absorption bands due to hydroxyl (3440 cm−1), conjugated aldehyde (1699, 1635 cm−1) and epoxide (1264 cm−1) functions, respectively. The absorption band at λmax 236 nm in the UV spectrum referred to a conjugated carbonyl group. Signals due to 20 carbons appearing in the 13C NMR spectra of 2 were categorized, by applying DEPT technique, into 2 CH3, 6 CH2, 8 CH, and four quaternary carbons (Table 1). 1H and 13C NMR spectra, together with a HSQC experiment, revealed the presence of the following characters: an aldehyde group [δH/δC 9.43/195.0], six oxygenated carbons [δC: 55.7 (s), 58.4 (d), 59.2 (d), 63.2 (t), and 71.5 (s)] an exocyclic double bond [δH/δC 5.34, 5.33/120.0, and 143.7 (s)], an α, β, γ, δ-unsaturated aldehyde [δH/δC: 9.43/195.0, 141.8 (s), 6.95 (d, 11.4)/152.7, 7.10 (dd, 15, 11.4)/122.4, and 6.39 (d, 15)/122.5], a disubstituted epoxy [δH/δC: 2.95/58.4 and 3.20/58.4], another disubstituted epoxy [δH/δC; 3.48, 3.17/54.4 and 55.7 (s)], and a carbinol group (CH2OH) [δH/δC; 3.23, 3.07/63.2], respectively. All this information suggested the presence of a nine-membered ring structure that is frequently found in this genus of soft corals.

H-H COSY and HMBC spectra (Figure 2) established the connections: C-3/C-4/C-12/C-13/C-14/C-15/C-16(C-17), C-1/C-4a/C-4/C-5/C-6, and C-8/C-9/C-10. The structure of 2 was well supported by comparison of its spectral data with those in literature [3], [4], [5], [6], and it was given the trivial name xeniumbellal (Figure 1) as a new natural product. After establishing the gross structure of compound 2, the relative stereochemistry of 2 was determined by the analysis of the coupling constant (J) values, by comparison of its spectroscopic data to those of Xenia diterpenes and from the NOESY cross-peaks (Figure 3). A cis-configuration was assigned to the epoxy moiety 8(9) due to the small measured (4.2 Hz) coupling constant between them. A trans-configuration for H-4a and H-11a was concluded due to the large J (11.4 Hz) observed between them. The E-geometry was assigned to the ∆4,12 double bond on the basis of the NOE cross-peaks observed between H-3 and H-12 and between H-13 and H-4a. The E-geometry of the ∆13 double bond was established by the large coupling constant (J=15 Hz) observed between H-13 and H-14. The suggested structure of the epimeric 7(18) epoxide was deduced based on NOESY cross-peaks (Figure 3) and by comparison of its spectral data with those of the similar diepoxy compound havannahine [20].

Compounds 3–5 were identified as aromadendrene, palustrol and viridiflorol by comparison of their spectral data with those in the literature [9], [10], [11].

After having established the chemical structures of compounds 1–5, a literature search suggested that polyhydroxysteroids, Xenia diterpenoids, and aromadendrane-type sesquiterpenoids may possess various antimicrobial and antitumor activities [3], [4], [5], [6], [7], [8], [21], [22], [23].

The crude extract and compounds 1–5 were subjected to a preliminary screening against a panel of Gram-negative and Gram-positive bacteria. The crude extract showed the highest antibacterial activity (diameter of inhibition zone ranging from 18 to 34 mm) compared with the individual five isolated compounds (Table 2).

Diameter of inhibition zone in mm at concentration level of 10 µg/ml of the crude extract and compounds 1 and 2.

| Tested microbe | Tested material | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Diameter of the inhibition zone (mm) | ||||

| Crude extract | 1 | 2 | Positive control (10 µg/ml)a | |

| Acinetobacter baumannii | 34±0.34 | 16±0.09 | 14±0.14 | 22±2.1 |

| Escherichia coli | 19±0.31 | 10±0.90 | 11±0.11 | 44±3.4 |

| Klebsiella pneumonia | 19±0. 99 | 10±0.40 | 11±0.09 | 33±2.1 |

| Pseudomonas aeruginosa | 21±1.14 | 10±0.01 | 11±0.04 | 40±2.5 |

| Staphylococcus aureus | 18±0.33 | 11±0.5 | 09±0.14 | 33±6.1 |

| Staphylococcus epidermidis | 18±0.44 | 08±0.06 | 08±0.07 | 35±5.1 |

| Streptococcus pneumonia | 19±0.54 | 10±0.22 | 11±0.04 | 43±5.1 |

| Aspergillus niger | 14±1.02 | 09±0.29 | 11±0.30 | 41±0.70 |

| Candida albicans | 12±0.99 | 09±0.19 | 10±0.80 | 29±0.90 |

aAmpicillin trihydrate for bacteria; amphotericin B for fungi. Compounds 3–5 did not exhibit antimicrobial activity at 10 µg/ml. Values are presented as mean±SD (n=3).

The more potent inhibition by the crude extract could be due to the synergism between all components of the extract, or to the presence of an un-isolated factor. 1 and 2 showed antibacterial activities against all tested bacteria, and the highest activity was found against A. baumannii with MICs of 0.22 and 0.28 mM, respectively, and the lowest activities were against S. epidermidis (Table 3). Resistance of A. baumannii to different antibiotics in hospitals has been well documented, due to its ability to resist desiccation and to survive on artificial surfaces. This bacterium has been found to be responsible for 19% of ventilator-associated pneumonia cases [24]. Furthermore, fractions 1 and 2 showed weak antifungal activities against Candida albicans and Aspergillus niger (MIC, 0.41 and 0.56–0.7 mM, respectively). No antimicrobial activities were recorded for compounds 3–5.

Minimal inhibitory concentrations (MIC) of the two active compounds 1 and 2 against the tested microbes.

| Tested microbe | Tested material | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| MIC (mM) | |||

| 1 | 2 | Positive controla | |

| Acinetobacter baumannii | 0.22±0.005 | 0.28±0.051 | ≥13 |

| Escherichia coli | 0.32±0.011 | 0.56±0.100 | 0.009±0.001 |

| Klebsiella pneumoniae | 0.32±0.033 | 0.56±0.034 | 0.009±0.002 |

| Pseudomonas aeruginosa | 0.32±0.021 | 0.42±0.044 | 0.013±0.001 |

| Staphylococcus aureus | 0.32±0.032 | 0.42±0.066 | 0.009±0.001 |

| Staphylococcus epidermidis | 0.41±0.091 | 0.70±0.007 | 0.009±−0.001 |

| Streptococcus pneumoniae | 0.32±0.101 | 0.42±0.067 | 0.007±0.002 |

| Candida albicans | 0.41±0.131 | 0.56±0.021 | 0.002±0.001 |

| Aspergillus niger | 0.41±0.125 | 0.70±0.131 | 0.001±0.001 |

aAmpicillin trihydrate for bacteria; amphotericin B for fungi. Mean±SD (n=3).

None of the compounds caused lethality in the brine shrimp Artemia salina (LD50 higher than 1.14 mM for 2, and even higher for the other compounds). Except for 2(LD50, 200 µg/ml=0.57 mM), no cytotoxicity of the compounds was observed against the lymphoma cell line, while compounds 1–5 showed no activity against the Ehrlich sarcoma cell line (Table 4).

Antitumor activity and toxicity of compounds 1–5.

| Tested product | Antitumor activity against the lymphoma cell line (LD50, mM) | Toxicity against Artemia salina (LD50, mM) |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | ≥1.60 | ≥2.40 |

| 2 | 0.57±0.08a | ≥1.14 |

| 3 | ≥3.92 | ≥3.92 |

| 4 | ≥3.60 | ≥3.60 |

| 5 | ≥3.60 | ≥3.60 |

| Bleomycin | 0.02±0.001 | ≥5 |

aSignificant result at p≤0.05 compared to control (untreated cells), no activity was observed for compounds 1–5 against the Ehrlich sarcoma cell line.

4 Conclusion

These results are promising, and product 2 may be used as a good antibacterial agent against multidrug resistant bacteria as well as a chemotherapeutic agent against tumor cells.

References

1. Schwartsmann G, Brondani da Rocha A, Berlinck RG, Jimeno J. Marine organisms as a source of new anticancer agents. Lancet Oncol 2001;2:221–5.10.1016/S1470-2045(00)00292-8Search in Google Scholar

2. Coll JC. The chemistry and chemical ecology of octocorals (Coelenterata, Anthozoa, Octocorallia). Chem Rev 1992;92:613–31.10.1021/cr00012a006Search in Google Scholar

3. Bishara A, Rudi A, Goldberg I, Benayahu Y, Kashman Y. Novaxenicins A–D and xeniolides I–K, seven new diterpenes from the soft coral Xenia novaebrittanniae. Tetrahedron 2006;62:12092–7.10.1016/j.tet.2006.09.050Search in Google Scholar

4. Munro MH, Blunt JW. Marine literature database. New Zealand: Department of Chemistry, University of Canterbury, 2006.Search in Google Scholar

5. El-Gamal AA, Wang S-K, Duh C-Y. Xenibellal, a novel norditerpenoid from the Formosan soft coral Xenia umbellate. Tetrahedron Lett 2005;46:4499–500.10.1016/j.tetlet.2005.04.118Search in Google Scholar

6. El-Gamal AA, Wang S-K, Duh C-Y. Umbellactal, a novel diterpenoid from the Formosan soft coral Xenia umbellate. Tetrahedron Lett 2005;46: 6095–6.10.1016/j.tetlet.2005.06.168Search in Google Scholar

7. Faulkner DJ. Marine natural products. Nat Prod Rep 2001;18:1–49.10.1039/b006897gSearch in Google Scholar

8. Duh CY, Wang SK, Chia MC, Chiang MY. A novel cytotoxic norditerpenoid from the Formosan soft coral Sinularia inelegans. Tetrahedron Lett 1999;40:6033–5.10.1016/S0040-4039(99)01194-6Search in Google Scholar

9. Warmers U, König WA. Sesquiterpene constituents of the liverwortCalypogeia fissa. Phytochemistry 1999;52:695–704.10.1016/S0031-9422(99)00321-0Search in Google Scholar

10. Cheer CJ, Smith DH, Djerassi C, TurschB, Braekman IC, Daloze D. Applications of artificial intelligence for chemical inference–XXI: Chemical studies of marine invertebrates-XVII. The computer-assisted identification of [+]-palustrol in the marine organism Cespitularia sp., aff. subviridis. Tetrahedron 1976;32:1807–10.10.1002/chin.197646056Search in Google Scholar

11. Faure R, Ramanoelin AR, Rakotonirainy O, Bianchini J-P, Gaydou EM. Two-dimensional nuclear magnetic resonance of sesquiterpenes. 4. Application to complete assignment of 1H and 13C NMR spectra of some aromadendrane derivatives. Mag Res Chem 1991;29:969–71.10.1002/mrc.1260290920Search in Google Scholar

12. Holder IA, Boyce ST. Agar well diffusion assay testing of bacterial susceptibility to various antimicrobials in concentrations non-toxic for human cells in culture. Burns 1994;20:426–9.10.1016/0305-4179(94)90035-3Search in Google Scholar

13. Chand S, Lusunzi I, Veal DA, Williams R, Karuso P. Rapid screening of the antimicrobial activity of extracts and natural products. J Antibiot (Tokyo) 1994;47:1295–304.10.7164/antibiotics.47.1295Search in Google Scholar PubMed

14. Aly MM, Gumgumjee N. Antimicrobial efficacy of Rheum palmatum, Curcuma longa and Alpinia officinarum extracts against some pathogenic microorganisms. Afr J Biotechnol 2011;10:12058–63.Search in Google Scholar

15. Meyer BN, Ferrigni NR, Putnam JE, Jacobsen LB, Nichols DE, Mclaughlan JL. Brine shrimp: a convenient general bioassay for active plant constituents. Planta Med 1982;45:31–4.10.1055/s-2007-971236Search in Google Scholar PubMed

16. Alarif WM, Al-Lihaibi SS, Ghandourah MA, Orif MI, Basaif SA, Ayyad S-E. Cytotoxic scalarane-type sesterterpenes from the Saudi Red Sea sponge Hyrtios erectus. J Asian Nat Prod Res 2016;18:611–7.10.1080/10286020.2015.1115019Search in Google Scholar PubMed

17. Badria FA, Ameen M, Akl MR. Evaluation of cytotoxic compounds from Calligonum comosum L. growing in Egypt. Z Naturforsch 2007;62c:656–60.10.1515/znc-2007-9-1005Search in Google Scholar PubMed

18. John Goad L, Akihisa T. Analysis of sterols, 1st ed. London: Blackie Academic & Professional, Chapman Hall, 1997.10.1007/978-94-009-1447-6Search in Google Scholar

19. Umeyama A, Shoji N, Ozeki M, Arihara S. Sarcoaldesterols A and B, two new polyhydroxylated sterols from the soft coral Sarcophyton sp. J Nat Prod 1996;59:894–5.10.1021/np960255jSearch in Google Scholar

20. Almourabit A, Gillet B, Ahond A, Beloeil J-C, Poupat C, Potier P. Invertébrés marins du lagon néo-calédonien, XI. Les Desoxyhavannahines, Nouveaux métabolites de Xenia membranacea. J Nat Prod 1989;52:1080–7.10.1021/np50065a026Search in Google Scholar

21. Wang ZL, Tang H, Wang P, Gong W, Xue M, Zhang HW, et al. Bioactive polyoxygenated steroids from the South China sea soft coral Sarcophyton sp. Mar Drugs 2013;11:775–87.10.3390/md11030775Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

22. Abdel-Lateff A, Alarif WM, Ayyad S-EN, Al-Lihaibi SS, Basaif SA. New cytotoxic isoprenoid derivatives from the Red Sea soft coral Sarcophyton glaucum. Nat Prod Res 2015;29:24–30.10.1080/14786419.2014.952637Search in Google Scholar PubMed

23. Al-Footy KhO, Alarif WM, Asiri F, Aly M, Ayyad S-EN. Rare pyrane-based cembranoids from the Red Sea soft coral Sarcophyton trocheliophorum as potential antimicrobial-antitumor agents. Med Chem Res 2015;24:505–12.10.1007/s00044-014-1147-1Search in Google Scholar

24. Koulenti D, Lisboa T, Brun-Buisson C, Krueger W, Macor A, Sole-Violan J, et al. Spectrum of practice in the diagnosis of nosocomial pneumonia in patients requiring mechanical ventilation in European intensive care units. Crit Care Med 2009;37:2360–8.10.1097/CCM.0b013e3181a037acSearch in Google Scholar PubMed

©2017 Walter de Gruyter GmbH, Berlin/Boston

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Review Article

- Structural diversity in echinocandin biosynthesis: the impact of oxidation steps and approaches toward an evolutionary explanation

- Research Articles

- Cytotoxic constituents of Alocasia macrorrhiza

- Isolation, antimicrobial and antitumor activities of a new polyhydroxysteroid and a new diterpenoid from the soft coral Xenia umbellata

- Volatile oil profile of some lamiaceous plants growing in Saudi Arabia and their biological activities

- Membrane permeabilizing action of amphidinol 3 and theonellamide A in raft-forming lipid mixtures

- Discovery and preliminary structure-activity relationship of the marine natural product manzamines as herpes simplex virus type-1 inhibitors

- NMR reassignment of stictic acid isolated from a Sumatran lichen Stereocaulon montagneanum (Stereocaulaceae) with superoxide anion scavenging activities

- Simultaneous formulation of terbinafine and salvia monoterpenes into chitosan hydrogel with testing biological activity of corresponding dialysates against C. albicans yeast

- Rapid Communication

- Chemical constituents of the leaves of Campylospermum elongatum

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Review Article

- Structural diversity in echinocandin biosynthesis: the impact of oxidation steps and approaches toward an evolutionary explanation

- Research Articles

- Cytotoxic constituents of Alocasia macrorrhiza

- Isolation, antimicrobial and antitumor activities of a new polyhydroxysteroid and a new diterpenoid from the soft coral Xenia umbellata

- Volatile oil profile of some lamiaceous plants growing in Saudi Arabia and their biological activities

- Membrane permeabilizing action of amphidinol 3 and theonellamide A in raft-forming lipid mixtures

- Discovery and preliminary structure-activity relationship of the marine natural product manzamines as herpes simplex virus type-1 inhibitors

- NMR reassignment of stictic acid isolated from a Sumatran lichen Stereocaulon montagneanum (Stereocaulaceae) with superoxide anion scavenging activities

- Simultaneous formulation of terbinafine and salvia monoterpenes into chitosan hydrogel with testing biological activity of corresponding dialysates against C. albicans yeast

- Rapid Communication

- Chemical constituents of the leaves of Campylospermum elongatum