Abstract

Antimicrobial peptides (AMPs) are small peptides found in many organisms defending themselves against pathogens. AMPs form the first line of host defence against pathogenic infections and are key components of the innate immune system of amphibians. In the current study, cDNAs of precursors of four novel antimicrobial peptides in the skin of Paa spinosa were cloned and sequenced using the 3′-RACE technique. Mature peptides, named spinosan A–D, encoded by the cDNAs were chemically synthesized and their chemical properties were predicted. The antimicrobial, antioxidative, cyotoxic and haemolytic activities of these four AMPs were determined. While the synthesised spinosans A–C exhibited no activity towards any of the bacterial strains tested, spinosan-D exhibited weak but broad-spectrum antimicrobial activities against Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria. All peptides were weakly haemolytic towards rabbit erythrocytes, had a strong antioxidative activity, and a low cytotoxic activity against HeLa cells. These findings provide helpful insights that may be useful in the future design of anti-infective peptide agents.

1 Introduction

The emergence of pathogenic bacterial and fungal strains with resistance to commonly used antibiotics in all regions of the world is a serious threat to public health and is thus a cause of concern to both physicians and the general public [1]. As such, scientists have started to focus on the development of newer and more potent classes of antibiotics; amongst the relevant substances obtained thus far, antimicrobial peptides (AMPs) may be considered novel alternatives for antibiotics in the next decades.

AMPs, which are small peptides generally composed of 12–60 amino acids, may be considered as evolutionarily ancient components of the innate immune response of many organisms against microbes [2, 3]. As key elements of the innate immune system, AMPs target a wide range of pathogens, including Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria, fungi and protozoa [4, 5]. AMPs also play a central role in recruiting and promoting many elements of the innate immune system of most living organisms [6, 7]. In recent studies, AMPs have even shown selective anticancer effects on eukaryotic cells.

The dorsal skin granular glands of amphibians can secrete various AMPs with broad-spectrum antibacterial and antifungal activities that serve as a defence against microorganisms and other pathogens in the environment [8, 9]. Zasloff first isolated one of these peptides, magainin, from the skin secretions of the African clawed toad Xenopus laevis in 1987 [10]. Since then, a diverse array of AMPs have been isolated, purified, cloned and structurally characterised from 250 species of anuran amphibians belonging to eight genera [11]. Although the amino acid sequences and secondary structures of AMPs are dissimilar, the peptides are almost invariably cationic, relatively hydrophobic and tend to form amphipathic α-helices or amphipathic β-sheet peptides stabilised by multiple disulfide bridges [12, 13]. The antimicrobial activities of these AMPs correlate with their ability to selectively rupture the membranes of various microbes.

The giant spiny frog Paa spinosa (Anura: Ranoidae) [14], is distributed in China and Vietnam, particularly in China. This frog is highly valued in Chinese markets for its medicinal and nutritional value [14, 15]. However, wild P. spinosa populations have been depleted by human hunting and environmental events. Thus, the species has been listed as ‘Vulnerable’ (A2abc) [International Union for the Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources (IUCN) Red List Categories]. Investigations on the natural AMPs in the skin secretions of this frog may provide insights that are useful not only for the development of anti-infective agents, but also for the protection of P. spinosa by understanding its innate defence system. In the present work, we cloned cDNAs encoding novel AMPs from P. spinose, using primers based on conserved regions, and characterised the peptides obtained. We also assessed the antimicrobial, haemolytic, antioxidative and cytotoxic activities of these peptides.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Animals

Adult specimens of P. spinosa were captured in Lanxi, Zhejiang Province, China, and bred in captivity at Zhejiang Normal University. These frogs were used in this study. All experiments had been approved by Zhejiang Normal University.

2.2 Molecular cloning of cDNAs encoding the precursor proteins

Total RNA was extracted from the skin of the adult individuals using RNAiso Plus (Takara Bio, Dalian, China) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. cDNA synthesis was conducted using a high-fidelity PrimeScript RT-PCR kit (Takara Bio). The primers were designed according to the cDNA sequences of conserved N-terminal signal peptides from selected Ranidae AMP precursors and synthesised by Takara Bio Inc., First-strand cDNA was synthesised using the GSP1 primer (5′-ATGTTCACCTTGAAGAAATCCCTG-3′) and the first sense primer (5′-TACCGTCGTTCCACTAGATTT-3′). First-round PCR products were reamplified with the GSP1 primer and the second sense primer (5′-CGCGGATCCTCCACTAGTGATTTCACTATAGG-3′). PCR was performed under the following conditions: 30 min at 94 °C, 30 s at 94 °C, 30 s at 56 °C and 1 min at 72 °C for 30 cycles; a final extension for 10 min at 72 °C was performed. PCR products were purified using 1% agarose gel, extracted using a SanPrep gel extraction kit (Sangon, Shanghai, China) and then cloned into the pMD-18T vector (Takara Bio) for sequencing.

2.3 Peptide synthesis

All peptides used in the bioactivity tests were synthesised using a peptide synthesiser (Model 433 A, Applied Biosystems Inc.) from GL Biochem Ltd. (Shanghai, China). The synthesised peptides were purified by reversed-phase HPLC with a Waters column (Waters ODS2 C18, 0.46 cm×25 cm). The purity of the peptides was higher than 95% and their identity was confirmed by MALDI-TOF-MS (Voyager DE Pro, ABI). Prior to the assays, synthesised peptides were dissolved in sterile deionised water to a final concentration of 2 mg/mL.

2.4 Prediction of the physicochemical properties and amphipathicity of the AMPs

Peptide parameters, including net charge, theoretical pI, number of amino acids and grand average of hydropathicity (GRAVY), were computed by ProtParam. The GRAVY value for a protein is calculated as the sum of the hydropathy values of all of its amino acids [16]. Prediction of the secondary structures of the peptides was performed using the online HNN program (Hierarchical Neural Network Method of Guerm-eur, 1997) (http://npsa-pbil.ibcp.fr/cgi-bin/npsa_automat.pl?page¼/NPSA/npsa_hnn.html).

2.5 Antimicrobial assay

The bacterial strains used in the antimicrobial assays, including the Gram-positive bacteria Staphylococcus aureus and Bacillus subtilis and the Gram-negative bacteria Escherichia coli and Aeromonas hydrophila, were obtained from the China General Microbiological Culture Collection Centre. Fresh LB medium was used in the culture of the microorganisms. The antibacterial activities of the peptides were tested using an inhibition zone assay on agarose plates seeded with viable bacteria according to Bennich et al. [17]. The minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) of a peptide against the bacteria was determined by a standard micro-dilution method using 96-well microtitre plates [18]. Briefly, the peptide was serially diluted twofold to concentrations between 0.78 and 100 μg/mL in LB broth. About 50 μL of the samples were dispensed into the wells of the plate, and each solution was inoculated with 50 μL (2×105 cfu/mL) of a bacterial culture in logarithmic growth phase. Sterile deionised water was used as a negative control. The absorbance of each sample at 600 nm was recorded, using a microtitre plate reader, after the cultures had been incubated for 18 h at 37 °C. The MIC was defined as the lowest peptide concentration present in a clear well determined by visual inspection. To assess the validity of the assay, parallel incubations were performed with gentamycin sulfate as a positive control.

2.6 Haemolytic assay

The haemolytic activity of the peptides was determined as follows. Approximately 6 mL of rabbit red blood cells (RBCs) was washed several times with 5 mL of 0.9% NaCl by centrifugation at 358 g for 5 min. Approximately 40 μL of the peptide samples (2 mg/mL) was added to 960 μL of diluted erythrocytes to obtain a final peptide concentration of 80 μg/mL, and the cell suspensions were incubated at 37 °C for 30 min. About μL of 0.1% Triton X-100 was added to 960 μL of diluted erythrocytes as a positive control, and 10 μL of 0.9% NaCl was added to 990 μL of diluted erythrocytes as a negative control. After 30 min, the solutions were centrifuged at 805 g for 5 min, and the absorbance in the supernatants was measured at 540 nm. The percentage of haemolysis, H%, was calculated according to the following equation: H% = (Asample – Anegative) × 100/Apositive – Anegative. The experiments were carried out in triplicate.

2.7 Antioxidative activity

A free radical scavenging activity assay was used to examine the antioxidative activity of the peptides. 2,2-Diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl (DPPH; Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) was used as a stable radical, and the experiment was carried out as previously reported [19]. Briefly, 8 μL of peptide solution (0.2 mg/mL) was mixed with 92 μL of 6 × 10–5 M DPPH dissolved in methanol. The mixture was kept in the dark for 30 min at room temperature, and the amount of reduced DPPH was quantified by measuring the decrease in absorbance at 520 nm. The percentage of free radicals scavenged (S%) was calculated according to the following equation: S% = (Ablank – Asample) × 100/(Ablank). Deionised water was used as a negative control.

2.8 Cytotoxicity assay

The cytotoxicity of the peptides was determined by the MTT [3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide] cell viability assay [20]. HeLa cells were donated by Zhejiang Normal University. About 200 μL of HeLa cells in the logarithmic growth phase were seeded into a 96-well plate and incubated at 37 °C for 24 h. The peptides were serially diluted to obtain final concentrations of 400, 200, 100, 50, 25 and 12.5 μg/mL. About 4 μL of each peptide concentration was dispensed into each well of the plate. Following incubation times of 20, 44 and 68 h, 20 μL of fresh medium containing 5 mg/mL MTT was added to the wells after removal of the test samples. After 4 h of incubation, 150 μL of DMSO was added to each well to dissolve the formed formazan crystals. The samples were subsequently shaken for 10 min at room temperature, and their absorbance was recorded at 570 nm using a microtitre plate reader. The positive control was a nutrient solution and the negative control was mitomycin. All experiments were performed three times with duplicates for each measurement point. The IC50 value was determined as the concentration of a sample at which the absorbance at 570 nm was reduced by 50%.

3 Results

3.1 Molecular cloning of cDNAs encoding AMP precursor proteins

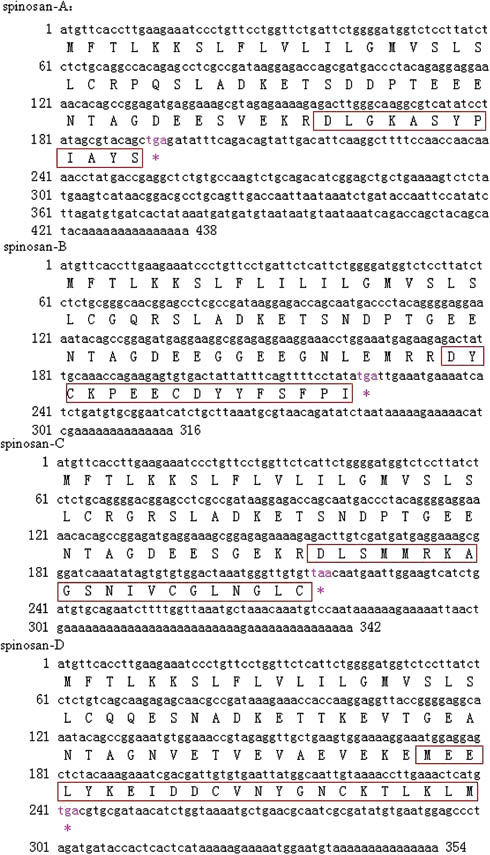

A total of four cDNAs encoding the precursors of four AMPs were cloned from the P. spinosa skin cDNA library. Alignment of the amino acid sequences with the NCBI protein database revealed that the four AMPs represent a novel family of frog AMPs with no similarities to known amphibian AMPs, except for parkerin and japonicin-1NPa [21] (similarities of 61%–81%). According to the generic name of the species of origin, the peptides were named spinosan-A, spinosan-B, spinosan-C and spinosan-D. The nucleotide sequences of the cDNAs and deduced amino acid sequences are shown in Figure 1.

Nucleotide and deduced amino acid sequences encoding AMP precursors. The box delineates the mature peptide and the asterisk indicates the stop codon.

All deduced precursor proteins showed overall architectures similar to those of other anuran AMP precursors. Each protein was composed of a putative signal peptide of 22 amino acid residues, an N-terminal acidic spacer domain of 16–29 residues, a Lys-Arg/Lys- processing site and a 12–23 residue C-terminal dermal peptide (Figure 2). The signal peptide sequences were highly similar amongst spinosan-A, spinosan-C and spinosan-D; in spinosan-B, Val11 was replaced with Ile11. The N-terminal acidic spacers of the peptides contained high levels of glutamic acid and aspartic acid.

Amino acid sequence alignment of AMP precursor proteins of P. spinosa.

Region 1, putative signal peptide domain; region 2, variable length acidic “spacer” peptide domain; region 3, KR (-Lys–Arg-), the conserved classical pro-peptide convertase processing site; region 4, the hypervariable domain that encodes the mature AMP.

3.2 Analysis of the physicochemical properties and amphipathicity of the AMPs

The GRAVY, net charge, theoretical pI and number of amino acids of the AMPs are shown in Table 1. Amongst the AMPs obtained in this study, only spinosan-C showed cationic features with a hydrophobic property.

Analysis of physicochemical properties of AMPs from the skin of P. spinosa.

| Peptide | GRAVY | Number of amino acids | PI | Net charge |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Spinosan-A | –0.142 | 12 | 5.83 | –1 |

| Spinosan-B | –0.669 | 16 | 3.92 | –3 |

| Spinosan-C | 0.450 | 20 | 8.06 | +1 |

| Spinosan-D | –0.478 | 23 | 4.51 | –2 |

GRAVY, Grand average of hydropathicity. Structural parameters of each peptide were calculated using the ProtParam tool.

3.3 Antimicrobial assay

The antimicrobial activities of the synthetic peptides were determined as MIC values. At a dose of 100 μg/mL, only spinosan-D exhibited slight anti-microbial activities towards Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria. Even at 2 mg/mL, spinosan-A, spinosan-B and spinosan-C showed no antimicrobial activity.

3.4 Haemolytic assay

The potential toxicity of AMPs was measured by a haemolytic assay against rabbit RBCs. No haemolysis was observed in the negative control, while 100% haemolysis was observed in the positive control (Triton-X). At a concentration of 80 μg/mL of spinosans A-D, maximally 4% haemolyis of rabbit RBC was observed (Table 2). This finding indicates that the interactions between the four AMPs and the phospholipids of the cell membrane of RBCs are very weak.

Haemolytic activity of AMPs from the skin of P. spinosa. against rabbit red blood cells.

| Peptide | Spinosan-A | Spinosan-B | Spinosan-C | Spinosan-D |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Haemolysis/% | 2.36±0.023 | 2.11±0.023 | 2.94±0.023 | 3.94±0.023 |

Each data point represents the mean of three independent assays.

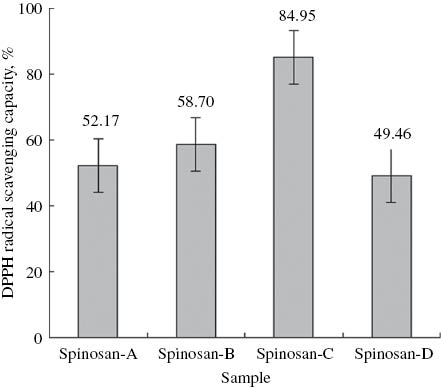

3.5 Antioxidative activity

At a concentration of 80 μg/mL, spinosan-C exhibited apparent antioxidative activity with an S% value-of 85%. For spinosans A, B and D the respective values were 52, 59 and 49%, respectively (Figure 3).

DPPH radical scavenging activity of spinosans A–D at a concentration of 80 μg/mL.

3.6 Cytotoxicity assay

The four AMPs exhibited low cytotoxic activity against HeLa cells. The cytotoxicity of spinosan-A was higher than that of the three other AMPs (Table 3).

Inhibition (IC50) of HeLa cell viability by the AMPs from the skin of P. spinosa.

| IC50 (μg/mL) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Spinosan-A | Spinosan-B | Spinosan-C | Spinosan-D |

| 350 | >400 | >400 | >400 |

4 Discussion

In the present study, cDNAs of four AMPs were cloned from P. spinosa. Compared with other AMPs obtained from frogs in Genbank, these four AMPs are novel and were subsequently named spinosan-A, spinosan-B, spinosan-C and spinosan-D.

Spinosan-D exhibited relatively weak but broad-spectrum antimicrobial activities against Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria. By contrast, the three other peptides were not active towards any of the bacterial strains tested. Whilst we are convinced that frog skin AMPs can provide lead templates for the design of novel anti-infection agents, these peptides usually have low bactericidal potency towards readily available microorganisms that are relevant to human disease. Low potency or even no antimicrobial activity is common amongst the AMPs discovered to date. For example, ishikawains 1–8, which were identified from the skin of Odorrana ishikawae, do not have particularly high antimicrobial activity [22]. The low antimicrobial potency of many ranid AMPs may be explained by the hypothesis that natural selection attenuates potency for the survival of cutaneous symbiotic bacteria that may provide the major system of defence against pathogenic microorganisms in the environment, with AMPs assumed to have a supplementary role in some species [23]. The giant spiny frog P. spinosa inhabits rocky streams in evergreen forests and open fields located on mountains that are 500–1500 m above sea level [24]; in these environments, surroundings are clean and pathogenic microorganisms are few. During long-term environmental adaptation, AMPs from P. spinosa may lose their original antibacterial functions. Another explanation for the low activities observed involves the secondary structures of the peptides. In nearly all cases, increasing the amphipathic α-helical character of a peptide is conducive to enhancing its activity. The α-helical conformation is responsible for the formation of pores in bacterial membranes and may thus lead to easier and stronger interactions between the peptide and microbial membranes.

In addition to direct antimicrobial activity, many AMPs from frogs possess strong antioxidative activity [19, 25–27]. Free radicals produced by an organism directly damage cell functions and genetic material [28]. Thus, free radicals in amphibian skins must be scavenged rapidly. In the free radical scavenging assay, the four novel peptides exhibited antioxidative activities even stronger than those of hainanenin-1 and hainanenin-5 from Amolops hainanensis with S% values of only 3.6% and 1.5%, respectively [29]. Our results confirm that peptides with potential antioxidative activity always contain cysteine, proline, methionine, tyrosine, or tryptophan residues which are responsible for radical scavenging activity of the molecules.

Spinosans A–D displayed relatively low potency, or even no antimicrobial activity, and they also exhibited only weak haemolytic activity towards rabbit RBCs (Table 2); these results are attributed to the low hydrophobicity of the molecules. Previous studies have also indicated that increasing the membrane affinity of the peptides by strengthening their hydrophobic interactions enhances their haemolytic activity [30].

Our results provide insights that will be useful in the future design and synthesis of peptide agents with selective toxicity and will aid in investigations on the relationship between the structure and haemolytic activity of AMPs. These findings increase the diversity of AMPs and provide more templates for designing anti-infection agents.

Most amphibian AMPs, such as bombinins and maximins, feature cytotoxic activity against cancer cell lines [31, 32]. The P. spinosa AMPs were hardly cytotoxic against HeLa cells, but spinosan-A was modestly cytotoxic (Table 3). Many AMPs have been shown to display cytotoxic activity against HeLa cells [32]; however, mechanisms responsible for this activity have yet to be identified.

Current results suggest that the novel AMPs obtained in this study may play a role in defending P. spinosa against environmental oxidative stresses. The four AMPs are new additions to the AMP family. Considering the activities of the peptides observed in this study, spinosan-D appears to be the most worthy of further research and utilisation.

Acknowledgements

The research was supported by the Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 31172116), the Major Science and Technology Specific Projects Zhejiang Province, China (Nos. 2010C12008 and 2012C12907-9), Project of Science and Technology Commission of Zhejiang, Province of China (No. 2014C32071), and Science and Technology Innovation Team of Zhejiang Province, China (No. 2012R10026-07).

References

1. Attoub S, Conlon JM, Mechkarska M. Esculentin-2CHa: a host-defense peptide with differential cytotoxicity against bacteria, erythrocytes and tumor cells. Peptides 2013;39:95–102.10.1016/j.peptides.2012.11.004Search in Google Scholar

2. Zasloff M. Antimicrobial peptides of multicellular organisms. Nature 2002;415:389–95.10.1038/415389aSearch in Google Scholar

3. Hancock RE. Petide antibiotics. Lancet 1997;349:418–22.10.1016/S0140-6736(97)80051-7Search in Google Scholar

4. Li X, Wang G, Wang Z. APD2: the updated antimicrobial peptides database and its application in peptide design. Nucleic Acids 2009;37:933–7.10.1093/nar/gkn823Search in Google Scholar

5. Hancock RE, Scott MG. Cationic antimicrobial peptides and their multifunctional role in the immune system. Immunol 2000;20:407–31.10.1615/CritRevImmunol.v20.i5.40Search in Google Scholar

6. Brown KL, Hancock RE. Cationic host defense cantimicrobial peptides. Immunol 2006;18:24–30.10.1016/j.coi.2005.11.004Search in Google Scholar

7. Hancock RE. Cationic peptides: effectors in innate immunity and novel antimicrobial. Lancet Infect 2001;1:156–64.10.1016/S1473-3099(01)00092-5Search in Google Scholar

8. Auvynet C, Rosenstein Y. Multifunctional host defense peptides: antimicrobial peptides, the small yet big players in innate and adaptive immuntiy. Febs J 2009;276:6497–508.10.1111/j.1742-4658.2009.07360.xSearch in Google Scholar PubMed

9. Boman HG. Peptide antibiotic and their role in innate immunity. Annu Eev Immunol 1995;13:61–92.10.1146/annurev.iy.13.040195.000425Search in Google Scholar PubMed

10. Zasloff M. Magainins, a class of antimicrobial peptides from Xenopus skin: isolation, characterization of two active forms and partial cDNA sequence of a precursor. P Natl Acad Sci USA 1987;84:5449–53.10.1073/pnas.84.15.5449Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

11. Li A, Wang C, Zhang Y. Purification, molecular cloning, and antimicrobial activity of peptides from the skin secretion of the black-spotted frog, Rana nigromaculata. World J Microb Biot 2013;29:1941–9.10.1007/s11274-013-1360-ySearch in Google Scholar PubMed

12. Chi SW, Han KH, Kim DH, Kim JS, Lee SH, Park YH. Solution structure and membrane interaction mode of an antimicrobial peptide gaegurin 4. Biochem Bioph Res Co 2007;352:592–7.10.1016/j.bbrc.2006.11.064Search in Google Scholar PubMed

13. Ding L, Har JY, Leptihn S, Wohland TJ. Correlation of charge, hydrophobicity, and structure with antimicrobial activity of s1 and MIRIAM peptides. Biochemistry 2010;49:9161–70.10.1021/bi1011578Search in Google Scholar

14. Liu CT, Yu BG, Zheng RQ, Zhang Y. Geographic variation in body size and sexual size dimorphism in the giant spiny frog Paa spinosa (David, 1875) (Anura: Ranoidae). J Nat Hist 2010;44:1729–41.10.1080/00222931003632682Search in Google Scholar

15. Huang H, Yang G, Ye SP, Zhang JY, Zheng RQ. Phylogeographic analyses strongly suggest cryptic speciation in the giant spiny frog (Dicroglossidae: Paa spinosa) and interspecies hybridization in Paa. PLOS One 2013;8:e70403.10.1371/journal.pone.0070403Search in Google Scholar

16. Hu YH, Liu JZ, Wang H, Yu Z J. Molecular cloning and characterization of antimicrobial peptides from skin of the broad-folded frog, Hylarana latouchii. Biochimie 2012;94:1317–26.10.1016/j.biochi.2012.02.032Search in Google Scholar

17. Bennich H, Boman HG, Engstrom A, Hultmark D, Kapur R. Insect immunity: isolation and structure of cecropin D and four minor antibacterial components from Cecropia pupae. Eur J Biochem 1982;127:207–17.10.1111/j.1432-1033.1982.tb06857.xSearch in Google Scholar

18. Abraham B, Conlon JM, Jumaa P, PaT, Sonnevend A. Brevinin-1BYa: a naturally occurring peptide from frog skin with broad-spectrum antibacterial and antifungal properties. Int J Antimicrob Ag 2006;27:525–9.10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2006.01.010Search in Google Scholar

19. Cong W, Liu C, Liu X, Wu J, Wang X, Yang H. Antioxidant peptidomics reveals novel skin antioxidant system. Mol Cell Proteomics 2009;8:571–83.10.1074/mcp.M800297-MCP200Search in Google Scholar

20. Mosmann T. Rapid colorimetric assay for cellular growth and survival: application to proliferation and cytotoxicity assays. J Immunol Methods 1983;65:55–63.10.1016/0022-1759(83)90303-4Search in Google Scholar

21. Zekuan L, Zhai L, Wang H. Novel families of antimicrobial peptides with multiple functions from skin of Xizang plateau frog, Nanorana parkeri. Biochimie 2010;92:475–81.10.1016/j.biochi.2010.01.025Search in Google Scholar PubMed

22. Fujii T, Iwakoshi-Ukena E, Okada G, Ukena K, Soga M, Sumida M. Characterization of novel antimicrobial peptides from the skin of the endangered frog Odorrana ishikawae by shotgun cDNA cloning. Biochem Bioph Res Co 2011;412:673–7.10.1016/j.bbrc.2011.08.023Search in Google Scholar PubMed

23. Conlon JM. Structural diversity and species distribution of host-defense peptides in frog skin secretions. Cell Mol Life Sci 2011;68:2303–15.10.1007/s00018-011-0720-8Search in Google Scholar

24. Zhao EM. China red data book of endangered animals: amphiba & reptiles. Bejing: Science Press, 1998.Search in Google Scholar

25. Feng F, Guo H, He W, Huang Y, Li Z, Zhang S. Host defense peptides in skin secretions of Odorrana tiannanensis: proof for other survival strategy of the frog than merely anti-microbial. Biochimie 2011;94:649–55.10.1016/j.biochi.2011.09.017Search in Google Scholar

26. Che Q, Feng F, Lu Z, Wang D, Wang H, Zhai L. Novel families of antimicrobial peptides with multiple functions from skin of Xizang plateau frog, Nanorana parkeri. Biochimie 2010;92: 475–81.10.1016/j.biochi.2010.01.025Search in Google Scholar

27. Hong J, Liu CB, Li DS, Ma DY, Wu J, Yang HL. Frog skins keep redox homeostasis by antioxidant peptides with rapid radical scavenging ability. Free Radical Bio Med 2010;48:1173–81.10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2010.01.036Search in Google Scholar

28. Izakovic M, Moncol J, Mazur M, Rhodes CJ, Valko M. Free radicals, metals and antioxidants in oxidative stress-induced cancer. Chem Biol Interac 2006;160:1–40.10.1016/j.cbi.2005.12.009Search in Google Scholar

29. Zhang SY, Guo HH, Shi F, Wang H, Li L, Jiao XD, et al. Hainaneins: a novel family of antimicrobial peptides with strong activity from Hainan cascade-frog, Amolops hainanensis. Peptides 2012;33:251–7.10.1016/j.peptides.2012.01.014Search in Google Scholar

30. Beyermann M, Bienert M, Dathe M, Krause E, Maloy WL, MacDonald DL, et al. Modulation of membrane activity of amphipathic, antibacterial peptides by slight modifications of the hydrophobic moment. Febs Lett 1997;417:135–40.10.1016/S0014-5793(97)01266-0Search in Google Scholar

31. Jin Y, Lee WH, Maximins S, Shen JH, Wang T, Zhang J, et al. A novel group of antimicrobial peptides from toad Bombina maxima. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2005;327: 945–51.10.1016/j.bbrc.2004.12.094Search in Google Scholar PubMed

32. Hoskin DW, Ramamoorthy A. Studies on anticancer activities of antimicrobial peptides. Biochim Biophys Acta 2008;1778: 357–75.10.1016/j.bbamem.2007.11.008Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

©2015 by De Gruyter

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Chemical characterization, antioxidant and cytotoxic activities of the methanolic extract of Hymenocrater longiflorus grown in Iraq

- Preventive effect of total glycosides from Ligustri Lucidi Fructus against nonalcoholic fatty liver in mice

- Synthesis of platinum(II) complexes of 2-cycloalkyl-substituted benzimidazoles and their cytotoxic effects

- cDNA cloning and functional characterisation of four antimicrobial peptides from Paa spinosa

- Evaluation of the water soluble extractive of astragali radix with different growth patterns using 1H-NMR spectroscopy

- SPME collection and GC-MS analysis of volatiles emitted during the attack of male Polygraphus poligraphus (Coleoptera, Curcolionidae) on Norway spruce

- Selective nematocidal effects of essential oils from two cultivated Artemisia absinthium populations

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Chemical characterization, antioxidant and cytotoxic activities of the methanolic extract of Hymenocrater longiflorus grown in Iraq

- Preventive effect of total glycosides from Ligustri Lucidi Fructus against nonalcoholic fatty liver in mice

- Synthesis of platinum(II) complexes of 2-cycloalkyl-substituted benzimidazoles and their cytotoxic effects

- cDNA cloning and functional characterisation of four antimicrobial peptides from Paa spinosa

- Evaluation of the water soluble extractive of astragali radix with different growth patterns using 1H-NMR spectroscopy

- SPME collection and GC-MS analysis of volatiles emitted during the attack of male Polygraphus poligraphus (Coleoptera, Curcolionidae) on Norway spruce

- Selective nematocidal effects of essential oils from two cultivated Artemisia absinthium populations