Chemical characterization, antioxidant and cytotoxic activities of the methanolic extract of Hymenocrater longiflorus grown in Iraq

-

Rafal S.A. Al-Anee

, Khulood W. Al-Sammarrae

Abstract

Hymenocrater longiflorus was collected from northern Iraq, and the chemical composition and antioxidant and cytotoxic activities of this plant were investigated. Ten compounds detected by HPLC-ESI/MS were identified as flavonoids and phenolic acids. The free radical scavenging activity of the 70% methanol extract was evaluated using the 2,2-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl (DPPH) assay. The antioxidant activities of the extract may be attributed to its polyphenolic composition. The cytotoxicity of the plant extract against the osteosarcoma (U2OS) cell line was assessed with the 3-(4, 5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2, 5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide (MTT) assay. The extract significantly reduced the viability of cells in a concentration- and time-dependent manner. Cells were arrested during the S-phase of the cell cycle, and DNA damage was revealed by antibodies against histone H2AX. The apoptotic features of cell shrinkage and decrease in cell size were also observed. Western blot analysis revealed cleavage of poly (ADP-ribose)-polymerase 1 (PARP-1), in addition to increases in the proteins p53, p21, and γ-H2AX. Collectively, our findings demonstrate that the H. longiflorus extract is highly cytotoxic to U2OS cells, most likely due to its polyphenolic composition.

1 Introduction

Natural products play a rapidly increasing role in the development of chemopreventive and therapeutic agents [1, 2]. They represent valuable sources of compounds with a wide variety of chemical structures that exhibit specific biological activities and provide important prototypes for the development of novel drugs [3, 4]. The discovery of cytotoxic agents from natural sources by following up ethnomedicinal uses or the results of previous antitumor screening has had a rich and fruitful past, with the identification of novel agents such as Vinca alkaloids, taxanes, camptothecins, and epipodophyllotoxins [5].

Plant extracts can be considered chemical libraries of structurally diverse compounds, therefore allowing a promising approach in drug discovery. Approximately 60% of all drugs that are currently undergoing clinical trials for treatment of cancers are either natural products or compounds derived from natural products [6]. Over the past years, the focus of modern anticancer drug discovery has been on a wide variety of natural compounds, especially on phenolic compounds. Flavonoids are polyphenolic compounds that are widely distributed in plants and are known to have a broad spectrum of biological and pharmaceutical activities [7]. They are potential cancer-protecting agents [8] and may block several steps in the progression of carcinogenesis, including cell transformation, invasion, metastasis, and angiogenesis, through inhibition of kinases, reduction of transcription factors, regulation of the cell cycle, and induction of apoptotic cell death [9]. The present study focuses on Hymenocrater longiflorus Benth. (Lamiaceae) from the Kurdistan Province of Iraq. Hymenocrater longiflorus is a dense bush with a strong characteristic aroma and green leaves. This species is also distributed in the Oramanat region (Kermanshah Province of Iran), where it is commonly known as “Oraman’s tulip” by the local people [10]. Hymenocrater longiflorus is utilized as a medicinal herb in local and traditional medicine especially in Kurdistan. The aerial parts of the herb, in crude or baked form, are utilized in local folk medicine as an anti-inflammatory, sedative, and anti-allergy treatment (for skin diseases and insect bites). Recently, the antibacterial, antifungal, and antioxidant activities of H. longiflorus have been investigated [11]. However, no report exists regarding the cytotoxic and antitumor properties of H. longiflorus. For this reason, the present study was designed to investigate the in vitro anti-tumor activities of the methanolic extract of H. longiflorus in the U2OS cell line. The chemical composition and antioxidant activity of the extract were studied as well.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Reagents

Dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO), 2,2-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl (DPPH), trypan blue dye 0.4%, 3-(4, 5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2, 5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide (MTT), Bradford reagent, bovine serum albumin, sodium-dodecyl sulfate (SDS), ammonium persulfate, isopropanol, bromophenol blue, tetra-ethylene-diamine, 4% paraformaldehyde, MOWIOL mounting medium, sulforhodamine101, camptothecin (CPT, C9911) and doxorubicin (D1515) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (Taufkirchen, Germany). DMEM media were purchased from Euroclone (Pero, Italy). Methanol, ethanol, and acetic acid were purchased from Carlo Erba (Cornaredo, Italy). Propidium iodide solution was obtained from Becton Dickinson (San Jose, CA, USA). Acetonitrile was purchased from DuPont (Wilmington, DE, USA). The anti-p53 monoclonal antibody (Clone sc-126), anti-p21 polyclonal antibody produced in rabbit (Clone sc-397), and anti-actinin monoclonal antibody (Clone sc-10750) were purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Dallas, TX, USA). The rabbit monoclonal antibodies anti-P-p53-ser15 (Clone 9286) and anti-γH2AX (Clone 2577) were obtained from Cell Signaling Technology (Danvers, MA, USA). The mouse anti-parp monoclonal antibody (Clone sc-53643) and goat anti-actin monoclonal antibody (Clone sc-1616) were purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology. The anti-H2AX (SER 139) polyclonal antibody (JBW301, Cat.05-636) was purchased from Millipore (Molsheim, France). The anti-rabbit fluorescence monoclonal antibody (goat anti-rabbit Cy3) was purchased from Jackson Lab (Bar Harbor, ME, USA), 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole dihydrochloride (DAPI) from Sigma-Aldrich, and TRIS-base from BDH (London, UK).

2.2 Collection and extraction of H. longiflorus

Hymenocrater longiflorus Benth (Lamiaceae) was collected from the Hawraman Mountain (1739 m above sea level) above the Ballkha village in the Kurdistan Province of Iraq in May 2012. The plant material was identified by Dr. Saman Abdulrahman Ahmad, Department of Field Crop, College of Faculty of Agriculture Science, University of Sulaimani, Sulaimani, Iraq. The fresh aerial parts of the plant were washed thoroughly with tap water at room temperature to remove dirt prior to drying. The washed aerial parts were dried in the shade at room temperature for 7 d and then crushed into a fine powder. Approximately 100 g of powder were extracted once in a Soxhlet extractor with 70% (v/v) methanol in water (500 mL) 2 h at 40 °C. After filtering through Whatman filter paper no. 3, the extract was reduced to dryness in a rotary evaporator under reduced pressure at 45 °C. The residue (3 g) was stored, protected from light, at –20 °C in a glass container until use. For in vitro studies, the H. longiflorus extract was dissolved at a concentration of 10 mg mL–1 in DMSO: water (2:1, v/v).

2.3 Qualitative analysis of H. longiflorus extract

The H. longiflorus sample (10 mg mL–1 in DMSO: water) was diluted 1:100 (v/v) with acetonitrile: water (1:4 v/v). The qualitative analysis of the constituents was done with an LTQ-Orbitrap XL mass spectrometer (Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) coupled to a 1200 series capillary LC pump and auto-sampler (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA). The ion source was a desorption electrospray ionization Omni spray (Prosolia, Indianapolis, IN, USA), which was used in nanoelectrospray mode for negative and positive ions. The HPLC separation was obtained with a Zorbax SB-C18 column (100 mm × 0.5 mm; 5 μm particle size), using an elution mixture composed of solvent A (0.05% acetic acid in water, v/v) and solvent B (acetonitrile). The injection volume was 1 μL, and the flow rate was 10 μL min–1. The elution gradient ranged from 20% to 100% of solvent B within 40 min. The gradient was held at 100% for 6 min and re-equilibrated for 8 min at 20% of solvent B. Samples were directly injected into the HPLC column, which was directly coupled to the ion source spray capillary by a liquid junction. Data processing and calculations were done using the LTQ-Orbitrap Xcalibur 1.4 software [12]. The available reference standards were used (apigenin, caffeic acid and acacetin) for identification by direct comparison of the retention times and mass spectra acquired in the same analytical conditions. For other peaks, the measured accurate mass (or the most probable chemical formula that can be calculated from it) was compared with reference compounds available online at different chemical database websites (www.chemspider.com, www.chemfinder.com and pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov).

2.4 Stable free radical scavenging capacity

The free radical scavenging activities of the plant extract were measured with the DPPH assay [13]. The DPPH (2,2-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl) radical has a deep violet color because of its unpaired electron; the radical scavenging capability can be determined spectrophotometrically by the absorbance loss at 517 nm, when the pale yellow non-radical form is produced. Equal volumes (0.5 mL) of DPPH (60 μM) and each plant extract (10, 20, 40, 100, 500, and 1000 μg mL–1) were mixed in a cuvette and allowed to stand for 30 min at room temperature. The absorbance was read at 517 nm in a UV/VIS Lambda 19 spectrophotometer. The absorbance of the control (DPPH solution) was also read. The percentage of DPPH decoloration of the sample was calculated using the following formula:

2.5 Cell growth and viability assay

The human osteosarcoma U2OS cell was procured from the cell bank of the Department of Biology, University of Naples Federico II, Naples, Italy. The cell line was cultured in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle medium (DMEM) supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum and 1% streptomycin/penicillin in a humidified atmosphere of 5% CO2 and 95% air at 37 °C in T 25 cm2 tissue culture flasks. For cell growth and cytotoxicity assays, the cells were seeded in 12-well culture plates, at a density of 8 × 104 cells mL–1 and incubated for 24 h as above. Cells were treated with four concentrations (50, 100, 150, and 200 μg mL–1) of plant extract for 24, 48, and 72 h. After each incubation period, cells were counted, and the viability was assessed using a cell counter [14]. The MTT assay was used for confirmation. Briefly, the cells were seeded at 10,000 cells per well (100 μL) in 96-well dishes and then incubated overnight as above. Different concentrations of plant extract (10, 20, 40, 80, 100, and 150 μg mL–1) were used and incubated for 2, 4, 8, 24, 48, and 72 h. Subsequently, MTT (dissolved in phosphate buffered saline (PBS) at 5 mg mL–1) was added to each well and incubated for 60 min in the dark. Exogenous MTT was removed, and 100 μL of acidified isopropanol (1 μL hydrochloric acid per 1 mL isopropanol) was added to each well to dissolve the formazan crystals. After 5 min incubation, absorbance was measured at 570 nm in a Biotex microplate reader. The intensity of color produced is directly proportional to the number of viable cells. Each experiment was performed in triplicate [15]. The relative cell viability (%) of the control wells containing the cell culture medium only as a vehicle was calculated as follows:

2.6 Flow cytometry

Analysis of the cell cycle was performed according to the method of Erba et al. [16], with slight modifications. The cells were counted and plated at a concentration of 1 × 106 cells per 100 mm plate, allowed to grow for 24 h, and subjected to 50 or 100 μg mL–1 plant extract. A negative control was run as well. The cells were harvested after 3 or 6 h of treatment by centrifugation at 400 g at 4 °C for 2 min. The supernatant was removed, and the cells were washed twice with PBS, fixed in cold methanol, and kept at –20 °C for at least 30 min. Approximately 500 μL of PBS was added, mixed well, and the cell suspension centrifuged at 240 g at 4 °C for 5 min. The cells were suspended in PBS, mixed, and incubated for 30 min in an ice bath. The cells were permeabilized for 20 min at room temperature by addition of 500 μL of hypotonic solution containing 0.1% Na-citrate, 50 μg RNase, and 50 μg propidium iodide (PI) in 1 mL of PBS. The fluorescence emitted (610 nm) from the PI-DNA complex was quantified after excitation (535 nm) of the fluorescent dye in the FACSCalibur flow cytometry system (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA, USA). According to the distribution of the DNA content, the G1-, S-, and G2/M-phases were distinguished [17]. The data were analyzed with CellQuest and ModFit 3.0 software.

2.7 Determination of morphological aspects by fluorescence microscopy

U2OS cells were seeded at a density of 5 × 104 cells in six multi-well plates containing a sterile cover slip on the bottom of each well and were allowed to adhere for 48 h. The cells were treated with 50 and 100 μg mL–1, respectively, of H. longiflorus extract for 6 h. Subsequently, the medium was discarded by aspiration. The cells were washed with filtered PBS and stained with sulforhadamine101-DAPI (4,6-diamidine-2-phenylindole dihydrochloride) solution for 30–60 min. After staining, the slides were rinsed with distilled water, air-dried, and covered with a cover slip. Nuclei were observed with a fluorescence microscope by using a 365 nm filter [18].

2.8 Immunofluorescence of H2AX histone phosphorylation

U2OS cells were counted and seeded at a density of 5 × 104 cells in 12 multi-well plates containing a sterile cover slip on the bottom of each well. The cells were allowed to adhere for 18 h in a humidified atmosphere of 5% CO2 and 95% air at 37 °C and subsequently treated for 4 h with H. longiflorus extract at 80 or 100 μg mL–1. After treatment, the medium was removed, and the cells were washed with PBS (two to three times). The cells were then fixed with cooled 4% paraformaldehyde for 15 min. The cells were washed with 1 mL of filtered PBS, cold 70% ethanol was added, and the mixtures left standing for at least 6 h. Subsequently, the cells were re-hydrated and permeabilized with 0.5% Triton X-100 for 10 min–15 min at room temperature, washed with PBS, and subjected to the blocking solution TBS-T (5 g of milk powder in 100 mL of 20 mM Tris-HCl, 1.5 M NaCl, and 1% Tween 20, pH 8.0) for at least 30 min at room temperature. After blocking, the cells were incubated with 20 μL of anti-γ-H2AX (SER 139) polyclonal antibody, diluted 1:100, for 1 h in the dark at 37 °C. After washing the cells several times with 1 mL of TBS-T, the cells were incubated with 20 μL of anti-rabbit Cy3 conjugated secondary antibody for 45 min in the dark at room temperature. The slides were washed three times with TBS-T, then twice with PBS and stained with DAPI X 1 for 10 min at room temperature. Finally, the slides were mounted onto cover slips with the aid of MOWIOL and dried at room temperature. They were subsequently inspected under a fluorescence microscope (TE Eclipse 2000, Nikon). Images were acquired using Vico software.

2.9 Western blot analysis

For immunoblotting, U2OS cells were grown under the same conditions described above and treated with H. longiflorus extract, or with the positive reference compound camptothecin (CPT). Protein content was quantified by the Bio-Rad DC protein assay (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA) according to Amente et al. [19]. Equal amounts of proteins (50 μg each) were subjected to separation by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) on a 10% polyacrylamide gel. The gel was then equilibrated in transfer buffer, containing 10 mM Tris base, 200 mM glycine and 10% methanol, for 5 min before proteins were electroblotted onto a nitrocellulose membrane (Bio-Rad). The nitrocellulose membranes were immediately stained in 0.1% Ponceau S in 5% acetic acid and then photographed. The blots were then blocked with blocking solution (prepared as above) prior to incubation with the respective antibodies against actin, actinin, p53, p-p53, p21, parp, and γ-H2AX. Incubation of primary antibodies was performed overnight at 4 °C with slow constant shaking. This step was followed by 15 min washes with TBS-T prior to 1 and 0.5 h of incubation with the secondary antibody at room temperature. After extensive washes, results were visualized by enhanced chemiluminescence substrate (ECL, Amersham, Arlington Heights, IL, USA) by using a Bio-Rad Chemi-Doc MP Imager Station.

2.10 Statistical analysis

Data were obtained by tabulation in the statistical program GraphPad Prism version 5.01 (GraphPad Software, La Jolla, CA, USA) and presented as mean ± standard error. The significance of the difference between means was assessed by Duncan’s test, in which P ≤ 0.05 was considered significant.

3 Results and discussion

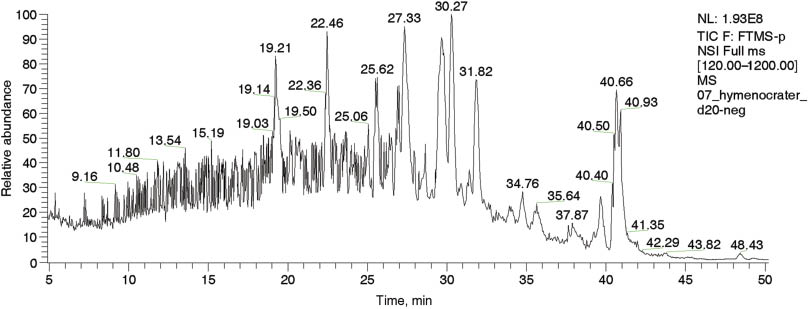

Ten compounds were identified by HPLC-ESI/MS in the methanolic extract of the H. longiflorus sample (Figure 1 and Table 1). The most abundant compounds were cirsimaritin, rosmarinic acid, apigenin-7-O-glucoside, genistein, and apigenin, followed by acacetin, carnosic acid, caffeic acid, ferulic acid, and isorhamnetin. The free radical scavenging activity of the H. longiflorus extract was determined by the DPPH assay and given as percentage of antiradical activity (ARA) as shown in Table 2. Such potent antiradical and antioxidant activity appears to be correlated with the total amount of polyphenolic compounds. Ahmadi et al. [11] reported that the essential oil and methanolic subfractions of a H. longiflorus extract have a potent radical scavenging activity in this assay.

Total ion current chromatogram and retention times in negative ion mode obtained by the LTQ-Orbitrap XL analyzer for the H. longiflorus methanolic extract.

Chemical compounds identified in the H. longiflorus methanolic extract by HPLC-ESI/MS in negative mode.

| Compound | Rt –ve, Min | Peak area, –ve | Molecular formula | Molecular mass, g moL–1 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Caffeic acid | 14.58 | 53,495,455 | C9H8O4 | 180.04 |

| Genistein | 26.04 | 106,470,766 | C15H10O5 | 270.24 |

| Ferulic acid | 21.40 | 35,969,442 | C10H10O4 | 194.18 |

| Cirsimaritin | 29.66 | 787,837,315 | C17H14O6 | 314.29 |

| Carnosic acid | 36.69 | 60,324,640 | C20H28O4 | 332.42 |

| Rosmarinic acid | 19.21 | 708,259,070 | C18H16O8 | 360.31 |

| Isorhamnetin | 21.63 | 27,621,294 | C16H12O7 | 316.26 |

| Apigenin | 26.04 | 106,470,766 | C15H10O5 | 270.24 |

| Apigenin-7-O- Glucoside | 19.44 | 421,579,156 | C15H10O5 | 270.24 |

| Acacetin | 32.37 | 73,250,463 | C16H12O5 | 284.26 |

| Total peak area (TPA) | 238 × 107 | |||

Rt, Retention time; –ve, negative mode.

DPPH free radical scavenging activity on different concentrations of the H. longiflorus methanolic extract.

| Concentration, μg mL–1 | Absorbance, Mean ± S.E. | ARA |

|---|---|---|

| 10 | 0.117 ± 0.002b | 51.50 |

| 20 | 0.104 ± 0.002b | 56.90 |

| 40 | 0.091 ± 0.001b | 62.20 |

| 100 | 0.052 ± 0.004c | 78.40 |

| 500 | 0.040 ± 0.002c | 83.50 |

| 1000 | 0.033 ± 0.001c | 86.20 |

| Positive control | 0.020 ± 0.001d | 91.70 |

Negative control absorbance, DPPH 0.242 ± 0.035 A; positive control, caffeic acid phenetheyl ester at 100 μg mL–1; ARA, anti-radical activity (%); different lower case letters, significant difference (P ≤ 0.05) between means. n = 3.

Flavonoids are considered the most abundant and most effective antioxidant compounds in plants. Present findings suggest that apigenin and related flavonoids are potentially useful as antioxidant and may have therapeutic applications in various diseases. Many natural phenols have been reported to scavenge reactive oxygen species (ROS), which are implicated in DNA damage, cancer, and accelerated cell aging [20, 21], while others can induce differentiation of numerous cell types [22] and inhibit glutathione reductase, cytochrome P450, and topoisomerase I-catalyzed DNA relegation [23].

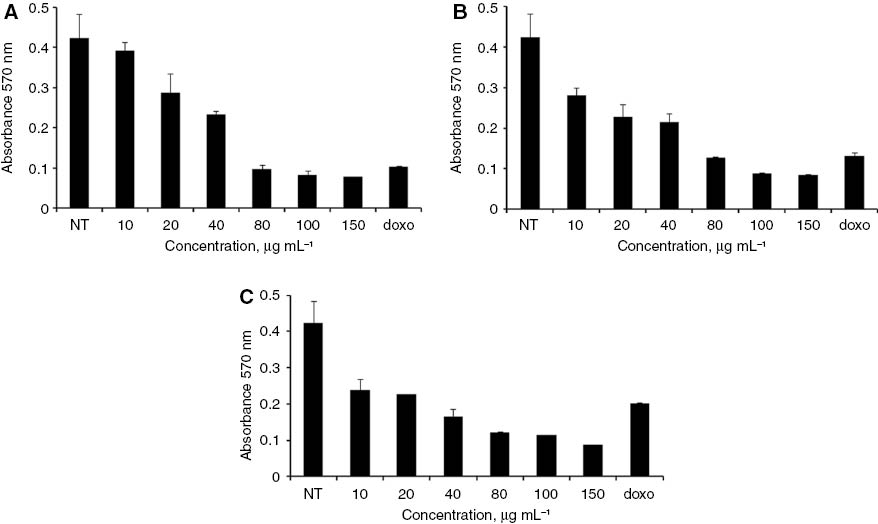

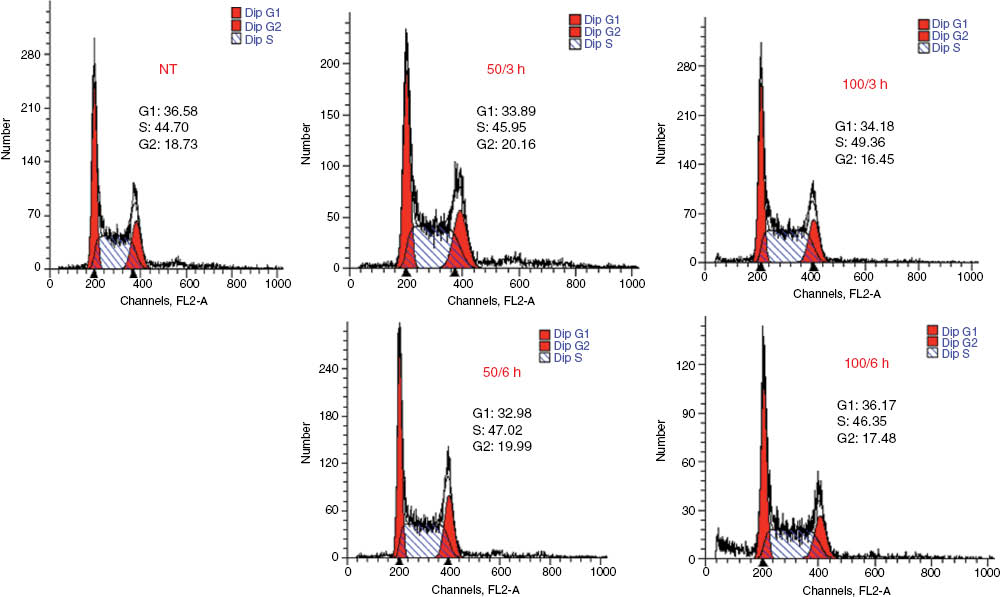

As reported in Table 3, treatment of U2OS cells with H. longiflorus extract decreased cell viability, and the effect was concentration- and time-dependent. Cytotoxicity evaluation by the MTT assay confirmed these findings (Figure 2, panels A–C). FACS analysis revealed that the H. longiflorus extract at both concentrations arrested U2OS cells slightly in S-phase (Figure 3). Many flavonoids have been shown to target the cell cycle by affecting cycle checkpoint pathways as well as the DNA damage response (DDR) pathway [24].

Mean of cell number of U2OS cells treated with different concentrations of the H. longiflorus methanolic extract.

| Concentration, μg mL–1 | Number of cells (Mean ± S.E) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| 24 h | 48 h | 72 h | |

| NT | 241,666 ± 112.60A,c | 393,750 ± 254.30A,b | 575,000 ± 432.40A,a |

| 50 | 200,000 ± 450.55B,a | 158,333 ± 164.75B,b | 83,333 ± 205.35B,c |

| 100 | 50,000 ± 188.95C,a | 16,666 ± 136.30C,b | 8333 ± 50.55C,c |

| 150 | 41,666 ± 126.40D,a | 8333 ± 67.45D,b | NilD,c |

| 200 | 16,666 ± 90.30E,a | NilE,b | NilD,b |

Nil, no growth; different capital letters, significant difference (P ≤ 0.05) between means of columns; different lower case letters, significant difference (P ≤ 0.05) between means of rows; NT, non treated cells.

Results of the MTT assay of U2OS cells treated with different concentrations of H. longiflorus extract at (A) 24, (B) 48 and (C) 72 h. Results are from one experiment that is representative of three similar experiments. Doxorubicin (doxo) was used as positive control at a concentration of 6 μg mL–1. The data were statistically analyzed by one-way ANOVA analysis. NT, Non treated cells.

Cell cycle histogram for the U2OS cell line obtained by FACS analysis, showing arrest in S-phase and decrease in cells in the G1-phase or G2-phase. Cells were harvested 3 or 6 h after addition of the extract and assayed for DNA content by propidium iodide (PI) staining; flow cytometry was then performed for cell cycle distribution. Flow cytometry histograms in which 50 or 100 μg mL–1 of H. longiflorus extract were used are presented. Percentage of cell distribution data for each treatment is indicated. NT, Non treated cells.

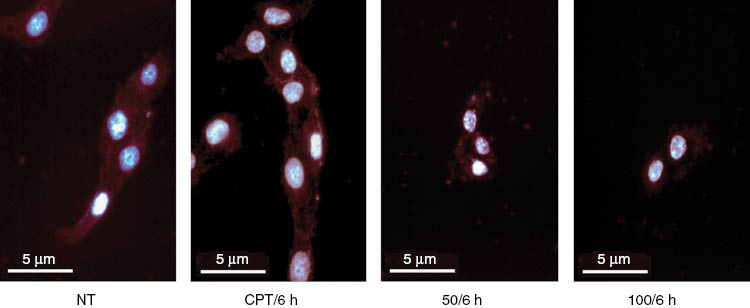

As seen in Figure 4, drastic changes in cellular morphology, such as a notable shrinkage of the cells, as well as aberrant nuclei were observed in response to the H. longiflorus extract. The observed antiproliferative effects (Table 3; Figure 2) prompted us to investigate possible DNA damage in treated cells. Induction of H2AX phosphorylation (γ-H2AX) was examined as a marker of DNA double-strand breaks (DSB) [25, 26]. The region flanking a DSB appears as a spot or focus when microscopically examined after antibody staining.

Morphological aspects of U2OS cells. After treatment with 50 or 100 μg mL–1 of H. longiflorus extract for 6 h, the cells were stained with DAPI and sulforhodamine101 (SR). Camptothecin CPT (12 μM) was used as positive control. The treatment revealed shrinkage of the cells or decrease in cell size. NT, Non treated cells.

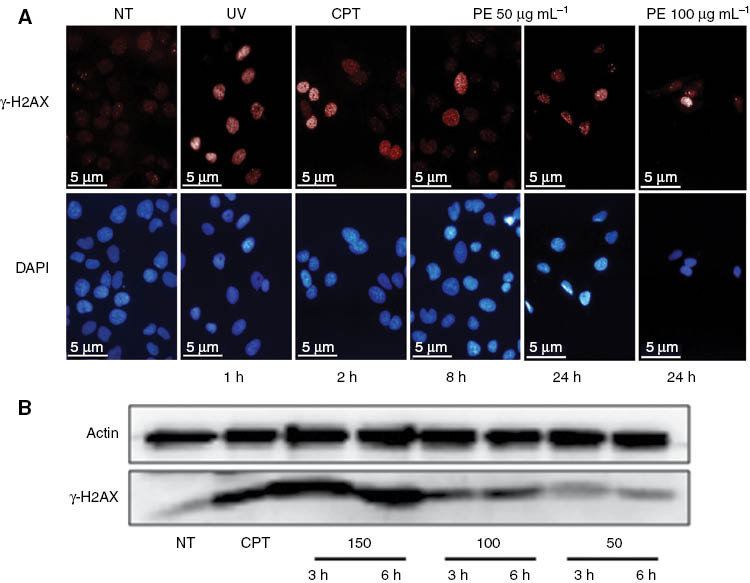

The increased occurrence of such spots, similar to those seen in these cells after CPT or UV treatment, was indeed observed in U2OS cells exposed to the H. longiflorum extract (Figure 5, Panel A) in a dose- and time-dependent manner (Figure 5, Panel B). Collectively, these data strongly suggest that the antiproliferative effect of H. longiflorus extract was due to DNA damage, followed by cell cycle arrest. γ-H2AX formation represents an early chromatin modification that is followed by DNA fragmentation during apoptosis [27, 28]. The involvement of apoptosis in U2OS cell death was suggested by the observed cell shrinkage (Figure 4), but this needs to be elucidated in more detail in further studies.

Phosphorylation of histone H2AX.

(A) Immunofluorescence staining for γ-H2AX. Increased γ-H2AX foci in treated cells treated with H. longiflorus at 50 and 100 μg mL–1. Camptothecin CPT (12 μM) and UV (40 J m–2) were used as positive control. (B) Immunoblotting for γ-H2AX. U2OS cells were incubated with 50, 100, and 150 μg mL–1 concentrations of the H. longiflorus extract for 3 and 6 h. Cell lysates were prepared, subjected to SDS-PAGE, and γ-H2AX visualized by immunoblotting with specific antibodies. The results showed increased levels of γ-H2AX (lower panel). Actin was used as a loading control (upper panel). Camprothecin (CPT) (12 μM) was used as positive control. Results are from one experiment representative of three similar experiments. NT, Non treated cells.

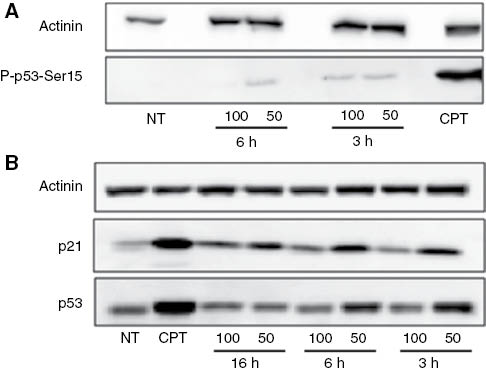

Following genotoxic damage, mammalian cells activate a coordinate molecular program called DNA Damage Response (DDR) to sense the damage and to induce molecular effector mechanisms involved in DNA repair and cell cycle arrest. The p53 protein and the stressed-activated generation of its phosphorylated form (P-p53-Ser15) play a pivotal role in DDR.

A detectable increase in the P-p53-Ser15 protein level was observed already after 3 h of treatment with the H. longiflorus extract (Figure 6, Panel A). The increase in the level of total p53 and also of p21 (a crucial effector of the p53 pathway) was found to be higher at 50 μg mL–1 extract than at 100 μg mL–1, likely due to the higher toxicity of latter concentration (Figure 6, Panel B), suggesting that the observed cell cycle arrest is, at least in part, due to a H. longiflorus extract-dependent activation of the p53-p21 axis. p53 is a transcription factor that recognizes specific binding sites within numerous target genes including mdm2, cyclin G, bax, and p21/WAF1/CIP1. Although multiple downstream targets are involved in the mediation of apoptotic effects, the main target for p53-induced cell cycle arrest seems to be the p21 gene [29].

Induction of the p53-p21 pathway. U2OS cells were incubated with 50 and 100 μg mL–1H. longiflorus extract for 3, 6, and 16 h. Cell lysates were prepared and subjected to SDS-PAGE. Actinin was used as a loading control.

(A) P-p53-Ser15 (lower panel). (B) p21 (central panel) and p53 (lower panel). Camptothecin (CPT) (12 μM) was used as positive control. Results are from one experiment representative of three similar experiments. NT, Non treated cells.

The response to DNA damage results in either apoptosis or cell cycle arrest to allow the lesions to be repaired, and in both pathways p53 is essential [17]. Specifically, in cell cycle arrest at G1-phase, p53 enhances p21 transcription, and p21 in turn inhibits cyclin-dependent kinase activity [30]. Loss of p21 results in replication defects and may lead to cell death after treatment with anticancer drugs [31]. Progression to S-phase after p53/p21-mediated arrest is achieved by proteasome-dependent degradation of p21 [32]. Genistein is known to activate stress signaling pathways that promote phosphorylation of p53 and the protein kinase ATM, leading to p21 induction [33] and γH2AX formation, as we have observed in our system (Figure 5).

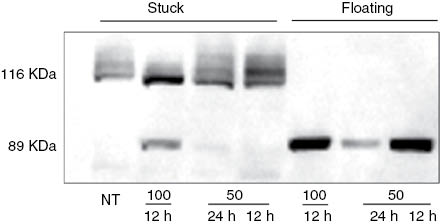

Poly(ADP-ribose) formation catalyzed by poly(ADP-ribose)polymerase-1 and -2 (PARP-1 and PARP-2) is one of the earliest events in the signaling of DNA damage. Following DNA damage, PARP-1 and PARP-2 modify their own functional domains (automodification) as well as other cellular proteins (heteromodification) to allow DNA damage repair. When the extent of DNA damage exceeds the cellular repair capacity and APT production is reduced due to NAD+ shortage, PARP-1 is cleaved by caspases into two fragments of 89 and 24 kDa, respectively, thereby initiating apoptosis [34]. In the present study, exposure to a high concentration (100 μg mL–1) of H. longiflorus extract for 24 h induced detachment of a number of cells from the walls of the wells and appeared to cause a form of cell death called anoikis. Anoikis is a cell death program that largely shares its molecular program with apoptosis, but occurs only when the cells are no longer attached to the substrate [35]. To determine which cell death program was initiated in the U2OS cells, the presence of PARP-1 fragments in cells either attached or freely floating was analyzed. As seen in Figure 7, the H. longifolius extract caused PARP-1 cleavage in U2OS cells still attached, suggesting that the cells were undergoing apoptosis rather than anoikis.

Western blot analysis of PARP-1 protein from the stuck (live cells) and floating (dead cells) samples, as indicated. Both the 116 kDa full-length protein, and the 89 kDa proteolytic fragment were detected using the monoclonal antibody C-2-10. NT, Non treated cells.

4 Conclusion

This study demonstrates that the H. longiflorus methanolic extract exerts potent antioxidant, cytotoxic, and apoptotic effects on U2OS cells. The search for the compound(s) responsible for the enhancement of PARP, p53, p21, and γ-H2AX appears worthwhile, and its/their potential as antitumor agent(s) should be investigated in the nude mice xenograft model system.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by a grant of Iraqi ministry of Higher Education and Scientific Research, and by grants from Associazione Italiana per la Ricerca sul Cancro (AIRC) and Ministero dell’Istruzione, dell’Università e della Ricerca (MIUR) to B. Majello.

Conflict of interest: The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest.

References

1. Newman DJ, Cragg GM, Snader KM. Natural products as sources of new drugs over the period 1981–2002. J Nat Prod 2003;66:1022–37.10.1021/np030096lSearch in Google Scholar

2. Butler MS. The role of natural product chemistry in drug discovery. J Nat Prod 2004;67:2141–53.10.1021/np040106ySearch in Google Scholar

3. Fulda S, Debatin KM. Extrinsic versus intrinsic apoptosis pathways in anticancer chemotherapy. Nature 2006;25:4798–811.10.1038/sj.onc.1209608Search in Google Scholar

4. King RE, Bomser JA, Min DB. Bioactivity of resveratrol. Compr Rev Food Sci Food Safety 2006;5:65–70.10.1111/j.1541-4337.2006.00001.xSearch in Google Scholar

5. Dantzig AH, Alwis DP, Burgess M. Considerations in the design and development of transport inhibitors as adjuncts to drug therapy. J Adv Drug Deliv Rev 2003;55:133–50.10.1016/S0169-409X(02)00175-8Search in Google Scholar

6. Rethy B, Csupor-Loffler B, Zupko I, Hajdu Z, Mathe I, Hohmann J, et al. Antiproliferative activity of hungarian asteraceae species against human cancer cell lines. J Pytother Res 2007;21:1200–8.10.1002/ptr.2240Search in Google Scholar PubMed

7. Duthie GG, Duthie SJ, Kyle JA. Plant polyphenols in cancer and heart disease: implications as nutritional antioxidants. Nutr Res Rev 2000;13:79–106.10.1079/095442200108729016Search in Google Scholar PubMed

8. Neuhouser ML. Dietary flavonoids and cancer risk: evidence from human population studies. J Nutr Cancer 2004;50:1–7.10.1207/s15327914nc5001_1Search in Google Scholar PubMed

9. Debnath J, Baehrecke EH, Kroemer G. Does autophagy contribute to cell death? Autophagy 2005;1:66–74.10.4161/auto.1.2.1738Search in Google Scholar PubMed

10. Rechinger KH. Labiatae. In: Rechinger KH. editor, Flora iranica, Graz (Austria): Akademische Druck-u Verlagsanstalt, 1982;150:239–50.Search in Google Scholar

11. Ahmadi F, Sadeghi S, Modarresi M, Abiri R, Mikaeli A. Chemical composition, in vitro anti-microbial, antifungal and antioxidant activities of the essential oil and methanolic extract of Hymenocrater longiflorus Benth., of Iran. Food Chem Toxicol 2010;48:1137–44.10.1016/j.fct.2010.01.028Search in Google Scholar PubMed

12. Sulaiman GM, Al Sammarrae KW, Ad’hiah AH, Zucchetti M, Frapolli R, Bello E, et al. Chemical characterization of Iraqi propolis samples and assessing their antioxidant potentials, Food Chem Toxicol 2011;49:2415–21.10.1016/j.fct.2011.06.060Search in Google Scholar PubMed

13. Kumar KS, Ganesan K, Subba Rao PV. Antioxidant potential of solvent extracts of Kappaphycus alvareii (Doty) Doty – an edible seaweed. Food Chem 2008;107:289–95.10.1016/j.foodchem.2007.08.016Search in Google Scholar

14. Louis KS, Siegel AC. Cell viability analysis using trypan Blue: manual and automated Methods. Methods Mol Biol 2011;740: 7–12.10.1007/978-1-61779-108-6_2Search in Google Scholar

15. Ferrari M, Chiara FM, Isetta AM. MTT colorimetric assay for testing macrophage cytotoxic activity in vitro. J Immunol Methods 1990;131:165–72.10.1016/0022-1759(90)90187-ZSearch in Google Scholar

16. Erba E, Bergamaschi D, Bassano L, Damia G, Ronzoni S, Faircloth GT, et al. Ecteinascidin-743 (ET-743), a natural marine compound, with a unique mechanism of action. Eur J Cancer 2001;37:97–105.10.1016/S0959-8049(00)00357-9Search in Google Scholar

17. Napolitano G, Amente S, Lavader ML, Palo G, Ambrosio S, Lania L, et al. Sequence-specific double strand breaks trigger P-TEFb-dependent Rpb1-CTD hyperphosphorylation. Mut Res 2013;749:21–7.10.1016/j.mrfmmm.2013.07.005Search in Google Scholar

18. Powolny A, Xu J, Loo G. Deoxycholate induces DNA damage and apoptosis in human colon epithelial cells expressing either mutant or wild-type p53. Int J Biochem Cell Biol 2001;33: 193–203.10.1016/S1357-2725(00)00080-7Search in Google Scholar

19. Amente S, Gargano B, Napolitano G, Lania L, Majello B. Camptothecin releases P-TEFb from the inactive 7SK snRNP complex. Cell Cycle 2009;8:1249–55.10.4161/cc.8.8.8286Search in Google Scholar PubMed

20. Peng DF, Hu TL, Schneider BG, Chen Z, Xu ZK, El-Rifai W. Silencing of glutathione peroxidase 3 through DNA hypermethylation is associated with lymph node metastasis in gastric carcinomas. PloS One 2012:7:e46214.10.1371/journal.pone.0046214Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

21. Echeverry C, Blasina F, Arredondo F, Ferreira M, Abin-Carriquiry JA, Vasquez L. Cytoprotection by neutral fraction of tannat red wine against oxidative stress-induced cell death. J Agric Food Chem 2004;52:7395–9.10.1021/jf040053qSearch in Google Scholar PubMed

22. Power KA, Ward WE, Chen JM, Saarinen NM, Thompson LU. Genistein alone and in combination with the mammalian lignans enterolactone and enterodiol induce estrogenic effects on bone and uterus in a postmenopausal breast cancer mouse model. Bone 2006;39:117–24.10.1016/j.bone.2005.12.015Search in Google Scholar PubMed

23. Doostdar H, Burke MD, Mayer RT. Bioflavonoids selective substrates and inhibitors for cytochrome P450 CYP1A and CYP1B1. Toxicology 2000;144:31–8.10.1016/S0300-483X(99)00215-2Search in Google Scholar

24. Haddad AQ. The cellular and molecular properties of flavonoids in prostate cancer chemoprevention. Ph.D Thesis, Institute of Medical Science, University of Toronto, 2008.Search in Google Scholar

25. Bhatia A, Dey P, Goel S, Singh G. Expression of γH2AX may help in defining a genetically more stable subtype of infiltrating ductal carcinoma of breast. Indian J Med Res 2013;137:759–66.Search in Google Scholar

26. Furuta T, Takemura H, Liao ZY, Aune GJ, Redon C, Sedelnikova OA, et al. Phosphorylation of histone H2AX and activation of Mre11, Rad50, and Nbs1 in response to replication-dependent DNA double-strand breaks induced by mammalian DNA topoisomerase I cleavage complexes. J Biol Chem 2003;278:20303–12.10.1074/jbc.M300198200Search in Google Scholar PubMed

27. Rogakou P, Nieves-Neira W, Boon C, Pommier Y, Bonnr WM. Initiation of DNA fragmentation during apoptosis induces phosphorylation of H2AX histone at serine 139. J Biol Chem 2000;275:9390–5.10.1074/jbc.275.13.9390Search in Google Scholar PubMed

28. Sulaiman GM, Ad’hiah AH, Al-Sammarrae KW, Bagnati R, Frapolli R, Bello E, et al. Assessing the anti-tumour properties of Iraqi propolis in vitro and in vivo. Food Chem Toxicol 2012;50:1632–41.10.1016/j.fct.2012.01.022Search in Google Scholar PubMed

29. Chen Y, Zhang L, Jones KA. SKIP counteracts p53-mediated apoptosis via selective regulation of p21Cip1 mRNA splicing. Genes Dev 2011;25:701–16.10.1101/gad.2002611Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

30. Harris SL, Levine AJ. The p53 pathway: positive and negative feedback loops. Oncogene 2005;24:2899–908.10.1038/sj.onc.1208615Search in Google Scholar PubMed

31. Liu G, Lozano G. p21 stability: linking chaperones to a cell cycle checkpoint. Cancer Cell 2005;7:113–4.10.1016/j.ccr.2005.01.019Search in Google Scholar PubMed

32. Gottifredi V, McKinney K, Poyurovsky MV, Prives C. Decreased p21 levels are required for efficient restart of DNA synthesis after S phase block. J Biol Chem 2004;279:5802–10.10.1074/jbc.M310373200Search in Google Scholar PubMed

33. Ye R, Goodarzi AA, Kurz EU, Saito S, Higashimoto Y, Lavin MF, et al. The isoflavonoids genistein and quercetin activate different stress signaling pathways as shown by analysis of site-specific phosphorylation of ATM, p53 and histone H2AX. DNA Repair (Amst) 2004;3:235–44.10.1016/j.dnarep.2003.10.014Search in Google Scholar PubMed

34. Huang Q, Wu YT, Tan HL, Ong CN, Shen HM. A novel function of poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase-1 in modulation of autophagy and necrosis under oxidative stress. Cell Death Differ 2009;16: 264–77.10.1038/cdd.2008.151Search in Google Scholar PubMed

35. Kroemer G, Galluzzi L, Vandenabeele P, Abrams J, Alnemri ES, Baehrecke EH, et al. Classification of cell death: recommendations of the nomenclature committee on cell death 2009. Cell Death Differ 2009;16:3–11.10.1038/cdd.2008.150Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

©2015 by De Gruyter

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Chemical characterization, antioxidant and cytotoxic activities of the methanolic extract of Hymenocrater longiflorus grown in Iraq

- Preventive effect of total glycosides from Ligustri Lucidi Fructus against nonalcoholic fatty liver in mice

- Synthesis of platinum(II) complexes of 2-cycloalkyl-substituted benzimidazoles and their cytotoxic effects

- cDNA cloning and functional characterisation of four antimicrobial peptides from Paa spinosa

- Evaluation of the water soluble extractive of astragali radix with different growth patterns using 1H-NMR spectroscopy

- SPME collection and GC-MS analysis of volatiles emitted during the attack of male Polygraphus poligraphus (Coleoptera, Curcolionidae) on Norway spruce

- Selective nematocidal effects of essential oils from two cultivated Artemisia absinthium populations

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Chemical characterization, antioxidant and cytotoxic activities of the methanolic extract of Hymenocrater longiflorus grown in Iraq

- Preventive effect of total glycosides from Ligustri Lucidi Fructus against nonalcoholic fatty liver in mice

- Synthesis of platinum(II) complexes of 2-cycloalkyl-substituted benzimidazoles and their cytotoxic effects

- cDNA cloning and functional characterisation of four antimicrobial peptides from Paa spinosa

- Evaluation of the water soluble extractive of astragali radix with different growth patterns using 1H-NMR spectroscopy

- SPME collection and GC-MS analysis of volatiles emitted during the attack of male Polygraphus poligraphus (Coleoptera, Curcolionidae) on Norway spruce

- Selective nematocidal effects of essential oils from two cultivated Artemisia absinthium populations