Abstract

Five novel Pt(II) complexes with some 2-cycloalkyl-substituted benzimidazole carrier-ligands were synthesized and evaluated for their in vitro cytotoxic activities against HeLa and OVCAR-3 cell lines. A cell viability test revealed that [dichloro-bis(2-cycloheptylbenzimidazole) platinum(II)] is less cytotoxic than cisplatin, and its cytotoxic effect can be compared with that of carboplatin. Flow cytometric analysis revealed that this complex at 117 μM concentration causes apoptosis in approx. 72 % of the OVCAR-3 cell population. In addition, the complex was found to cause an increase in the SubG1 population of both OVCAR-3 and HeLa cells and to cause less apoptosis in HeLa cells than cisplatin.

1 Introduction

In clinical practice, platinum-based complexes are widely used for the treatment of cancer [1]. Cisplatin [cis-diamminedichloroplatinum(II)], oxaliplatin [trans-L-(diaminecyclohexane)oxalateplatinum(II)] and carboplatin [cis-diamine(1,1-cyclobutanedicarboxylate)platinum(II)] are used for treating various types of cancer, including genitourinary, colorectal and non-small cell lung cancer [2, 3]. However, the clinical success of cisplatin is limited by severe side effects as well as intrinsic and acquired drug resistance [4, 5]. For example, while initially high response rates can be achieved in the treatment of ovarian cancer, the long-term results are disappointing due to the development of drug resistance leading to recurrence of the cancer and subsequent death of most of these patients [6, 7]. To increase the efficacy and decrease the side effects, much research is done in the field of platinum based anticancer drug design [8].

It is generally thought that platinum drugs exert their anticancer effects by interaction with DNA, thereby inducing programmed cell death [9]. Bonds between Pt(II) and guanine N7, which is readily accessible in the major groove of DNA, are very strong, and intrastrand crosslinking of two adjacent guanines by square-planar Pt(II) results in bending and unwinding of DNA. These significant structural changes in DNA induced by platination trigger programmed cell death (apoptosis) in a series of downstream events that result from protein and enzyme recognition of the damaged DNA [10].

Cellular resistance to cisplatin is mainly attributed to up-regulation of DNA repair and of pathways promoting damage tolerance, furthermore to reduced intracellular accumulation of the drug and its inactivation by thiol-containing reductants such as glutathione and metallothionein, and lastly, alterations in proteins involved in apoptosis [11].

One strategy to overcome cisplatin resistance is to design new platinum complexes that specifically deal with some or even all of the resistance mechanisms [12].

With the consideration that variation in the chemical structure of the amine groups of cisplatin can significantly affect the cytotoxic activity and toxicity of platinum complexes, and with the aim of determining the effect of the substituents in position 2 of the benzimidazole carrier ligands of platinum(II) complexes on cytotoxic proporties, we previously synthesized some platinum(II) complexes with 2-substituted benzimidazole ligands [13–18].

It was found that some of these platinum complexes have in vitro cytotoxic activities on human rhabdomyosarcoma (RD) [14], cervix (HeLa) [19], larynx carcinoma (Hep-2) [20], MDA-MB-231 [21] and breast cancer (MCF-7) [22] cell lines.

In the present report, in order to determine the role of the hydrophobic cycloalkyl substituents (cyclo-propyl, -butyl, -pentyl, -hexyl, -heptyl) in position 2 of the benzimidazole carrier ligands on the cytotoxic activity of the platinum(II) compounds, the in vitro cytotoxic activity of 2-cycloalkyl-benzimidazole Pt(II) complexes on human ovarium (OVCAR-3) and cervial carcinoma (HeLa) cell lines was tested. We also report the effect of the representative compound 2-cycloheptylbenzimidazole Pt(II), which was found to be the most active among the tested compounds, on the cell cycle and apoptosis.

2 Experimental

2.1 Materials and instrumentation

All chemicals and solvents used were of reagent grade (Merck, Darmstadt, Germany; Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) and were used without further purification. All cell culture reagents were purchased from Gibco Life Technologies (Carlsbad, CA, USA).

Melting points were determined in an Electrothermal 9200 melting point apparatus and are uncorrected. Infrared (IR) spectra were obtained using a Perkin Elmer Spectrum 400 FTIR/FTNIR spectromer equipment with a Universal ATR Sampling Accessory in the range of 4000–400 cm–1. For the region of 400–200 cm–1, the samples were analyzed with a FTIR IFS 66/S spectrometer. Elemental analyses were performed with a Leco 932 CHNS analyzer, and proton magnetic resonance (1H-NMR) spectra were recorded in dimethylsulfoxide (DMSO)-d6 (Merck) on Varian Mercury 400 MHz FT NMR spectrometer. High resolution mass spectra data (HRMS) were collected in-house using a Waters LCT Premier XE mass spectrometer (high sensitivity orthogonal acceleration time-of-flight instrument) operating in ESI (+) (positive ion mode), coupled to an AQUITY ultra performance liquid chromatography system (Waters Corporation, Milford, MA, USA). Thin-layer chromatography (TLC) was performed on precoated aluminum plates (Silicagel 60 F254, Merck). Plates were visualized by ultraviolet light, Dragendorff reagent, or iodine vapor.

2.2 General procedure for the synthesis of the ligands

Five novel Pt(II) complexes of the structure Pt(L2Cl2) with some 2-cycloalkyl-benzimidazole carrier ligands (L) were synthesized according to the method of [23]. The ligands had been synthesized previously as indicated below.

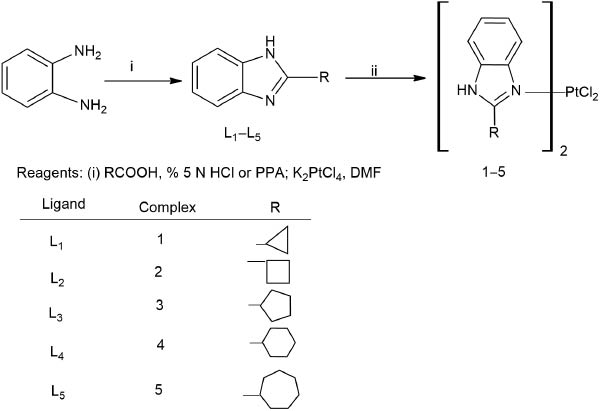

Ligands (L1-L5) were synthesized by condensation of the corresponding carboxylic acid with 1,2-phenylenediamine in the presence of 5N hydrochloric acid for L1, or polyphosphoric acid for L2-L5 as shown in Scheme 1.

Synthesis of carrier ligand and Pt(II) complexes.

The melting points of L1 (found m.p.: 236 °C Lit. m.p.: 234–236 °C) [24], L2 (found m.p.: 221 °C Lit. m.p.: 229–230 °C) [24], L3 (found m.p.: 259 °C Lit. m.p.: 251–253 °C) [24], L4 (found m.p.: 283 °C Lit. m.p.: 282 °C) [25] and L5 (found m.p.: 245 °C Lit. m.p.: 239–243 °C) [26] were in accordance with the literature.

2.3 Synthesis of the platinum(II) complexes

2.3.1 [Dichloro-bis(2-cyclopropylbenzimidazole)platinum(II)] ([PtL12Cl2].2.5H2O) (1):

316 mg (0.002 mol) L1 and 415 mg (0.001 mol) K2PtCl4 were dissolved in 5 mL DMF. The reaction mixture, protected from light, was heated at 65 °C for 12 days. Precipitated KCl was removed by filtration. A solution of 5 % (w/v) aqueous KCl (3 mL) was then added to the filtered solution and the mixture was stirred for 2 h. The resulting precipitate was filtered off, washed several times with small portions of water, ethanol and diethylether and dried in vacuo. Yield: 20 %, 0.116 g pure. HRMS [M+H]+ calcd. m/z 583.1797, found m/z 583.1800.

C20H20ClN4Pt.2.5 H2O: calc. C 38.28, H 4.01, N 8.93; found: C 37.75, H 3.47, N 9.006 %. IR (KBr) ν 336, 323 (Pt-Cl) cm–1.

2.3.2 [Dichloro-bis(2-cyclobutylbenzimidazole)platinum(II)] ([PtL22Cl2]. 0.5DMF) (2):

The procedure for the synthesis of complex 1 was followed using 258 mg (0.0015 mol) L2 and 311 mg (0.00075 mol) K2PtCl4 at 65 °C for 8 days.

Yield: 24 %, 0.160 g pure.HRMS [M+H]+ calcd. m/z 611.4529, found m/z 611.2152.

C22H24Cl2 N4Pt.0.5DMF: calc. C 43.62, H 4.28, N 9.74; found: C 43.84, H 4.604, N 9.19 %. IR (KBr) ν 323 (Pt–Cl) cm–1.

2.3.3 [Dichloro-bis(2-cyclopentylbenzimidazole)platinum(II)] ([PtL32Cl2]) (3):

The procedure for the synthesis of complex 1 was followed using 372 mg (0.002 mol) L3 and K2PtCl4 415 mg (0.001 mol) at 65 °C for 7 days.

Yield: 22 %, 0.144 g pure. HRMS [M+H]+ calcd. m/z 639.5066, found m/z 639.4907.

C24H28Cl2N4Pt: calc. C 45.15, H 4.42, N 8.77; found: C 44.97, H 4.42, N 8.94 %. IR (KBr) ν 336, 319 (Pt–Cl) cm–1.

2.3.4 [Dichloro-bis(2-cyclohexylbenzimidazole)platinum(II)] ([PtL42Cl2]. 0.5DMF) (4):

The procedure for the synthesis of complex 1 was followed using 400 mg (0.002 mol) L4 and K2PtCl4 415 mg (0.001 mol) at 65 °C for 8 days.

Yield: 25 %, 0.166 g pure. HRMS [M+H]+ calcd. m/z 667.5604, found m/z 667.2774.

C26H32Cl2N4Pt.0.5 DMF: calc. C 46.97, H 5.36, N 8.96; found: C 47.46, H 5.35, N 8.72 %. IR (KBr) ν 319 (Pt–Cl) cm–1.

2.3.5 [Dichloro-bis(2-cycloheptylbenzimidazole)platinum(II)] ([PtL52Cl2]) (5):

The procedure for the synthesis of complex 1 was followed using L5 500 mg (0.002 mol) and K2PtCl4 415 mg (0.001 mol) at 65 °C for 9 days.

Yield: 43 %, 0.30 g pure. HRMS [M+H]+ calcd. m/z 695.6141, found m/z 695.3070.

C28H36Cl2N4Pt: calc. C 48.42, H 5.22, N 8.07; found: C 47.80, H 5.27, N8.04 %. IR (KBr) ν 331, 323 (Pt-Cl) cm–1.

2.4 Cell culture

The OVCAR-3 and HeLa cell lines were obtained from the Cell and Virus Bank Department, Foot and Mouth Disease Institute (Ankara, Turkey). The cells were cultured in RPMI 1640 and DMEM medium, respectively, containing 2 mM L-glutamine, streptomycin (100 μg/mL), penicillin (100 U/mL) and 10 % heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum (FBS). The cells were grown in an incubator containing 5 % CO2 at 37 °C. All cell culture reagents were purchased from Gibco Life Technologies (Grand Island, NY, USA).

2.5 Preparation of test compounds

Stock solutions of the tested complexes were prepared in dimethylformamide (DMF) diluted with culture medium within 1 h, and immediately used in the experiments to avoid the possible ligand exchange between the test compounds and DMF. The final concentration of DMF never exceeded 0.1 % and had no effect on the cells. The culture medium was used as a negative control. Compounds 1–5 in concentrations of 80 and 160 μM, cisplatin at 10, 20 and 40 μM, and carboplatin at 10, 20, 40 and 80 μM were incubated in 96-well plates at 37 °C in humidified air containing 5 % CO2. The experiments were repeated three times.

2.5.1 MTT[3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide] cytotoxicity assay:

After cells had reached 90–95 % confluence, their viability was evaluated by the trypan blue exclusion test. For this, the cells were resuspended in culture medium to a density of 1 × 105 cells mL–1. Aliquots of 100 μL of cell suspension were added to the wells of a 96-well plate (Costar, Cambridge, MA, USA) and incubated for 24 h. Then, 100 μL of freshly prepared agents were added. 200 μL of culture medium without cells were used as negative control. The reference compounds cisplatin (CAS 15663-27-1) and carboplatin (CAS 41575-94-4) were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich. After 72 h incubation, 20 μL of MTT (Sigma-Aldrich) solution (5 mg/mL) were added to each well and the plates incubated for further 4 h. Then, to each well 100 μL isopropanol were added and the plates left standing, until after 4 h the purple formazan crystals were completely dissolved [27]. Absorbance was measured at 570 nm using a microplate ELISA reader. Absorbance of the negative control was substracted, and IC50 values were calculated using prism4, GraphPad software and program.

2.6 Cell cycle and subG1 peak analyses by flow cytometry

For the analysis of the apoptotic subG1 peak and cell cycle phases, the BD Cycletest Plus DNA Reagent Kit (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA, USA) was used according to the manufacturer’s recommendations. OVCAR-3 and Hela cells were seeded into 6-well plates (5 × 105 cells/well) treated with the twofold IC50 concentration of the compounds. Cells without additions were used as control. After 72 h treatment, cells were suspended by trypsin-EDTA and washed twice with cold PBS. Cell suspensions were consecutively exposed to 250 μL solution A (trypsin for 10 min, 200 μL solution B (trypsin inhibitor and RNase) for 10 min, and 250 μL solution C (propidium iodine stain) for 10 min at 4 °C in the dark. Cellular DNA content was monitored by a BD FACS CANTO II system with BD Modfit LT 3.2 software (BD Biosciences).

2.7 Annexin V staining apoptosis test

OVCAR-3 or Hela cells (0.5 × 106) were seeded into a 6-well plate and incubated for 24 h. Test compounds were added to the cells at twofold IC50 concentration. The cells were incubated under 5 % CO2 for 72 h and then collected with trypsin-EDTA. The subsequent procedures were carried out according to the instructions provided by the manufacturer of the FITC AnnexinV Apoptosis Detection Kit (BD Biosciences). Briefly, cells were washed with PBS, suspended in binding buffer, and 5 μL annexinV-FITC and 5 μL propidium iodide (PI) were added and the suspensions incubated for 15 min at RT. The samples were then analyzed in a flow cytometer (BD Biosciences FACS CANTO II system with FACS Diva software).

2.8 Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were performed using the computer software SPSS for Windows version 11.5 (SPSS Inc., Chiago, IL, USA). The Friedman test was used for multiple statistical comparisons. The Wilcoxon test was used as a post hoc test. A p-value <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

3 Results and discussion

3.1 Chemistry

The carrier ligands L1–L5 were prepared according to the method of [23] as shown in Scheme 1. Their melting points were in accordance with the literature.

The platinum(II) complexes 1–5 were synthesized by the reaction of the corresponding ligands and potassium tetrachloroplatinate in DMF. They were characterized by elemental analysis, HRMS, 1H-NMR, and IR spectra. Elemental analysis suggested a 1:2 (metal/ligand) stoichiometry for the complexes, which was supported by the HRMS spectra.

The IR spectra of the complexes in the regions of 4000–650 and 700–40 cm-1 were characteristically different from those of the free ligands. The Pt–N and Pt–Cl vibrations are considered characteristic for dichloro–diamine platinum complexes. But the metal-nitrogen stretching bands could not be distinguished from other ring skeleton vibrations present in the spectra. In the far-IR region of the spectra of compounds 2 and 4, a new broad band centered at ~320 cm–1 with a half-width of about 30 cm–1 appeared, due to v (Pt-Cl) and in the spectra of complexes 1, 3 and 5 two bands appeared in the range 336–319 cm–1, due to ν (Pt-Cl). It is well known that cis-dichloro complexes should show two bands of medium intensity because the vibrations are additive, but in many cases the second band appears only as a shoulder [28]. In some cases, cis-dichloro complexes show only one band due to low resolution independent of cis- or trans-configuration [29].

The 1H-NMR spectra of the Pt(II) complexes in DMSO-d6 (Table 1) are indicative of complex formation. These spectra were recorded immediately after dissolving the complexes in DMSO-d6, in order to avoid a ligand exchange reaction between the respective platinum complex and DMSO-d6. The spectra of the complexes revealed considerable differences from those of the free ligands. The large downfield shifts in the imidazole N1-H signal of the complexes compared to their ligands are the result of an increase in the N1-H acidic character after platinum binding [30]. The changes in the chemical shift observed upon coordination (Δδ = δ complex – δ free ligand) are mostly positive, indicating a decrease in electronic density on the 2-substituted benzimidazole ligands upon coordination of the platinum. The NH signal appears at around 12 ppm in L1–L5 and is shifted downfield in their complexes (13.2–13.4 ppm).

1H-NMR data of compounds 1–5.

| Compound | NH | Ar–H | Al–H |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | – | 7.95 ppm (m, 2H) 7.1–7.4 ppm (m, 6H) | 2.1 ppm (m,2H) 1 ppm (m,4H) 1.2ppm (m,4H) |

| 2 | 13.4(s,2H) | 8.2 ppm (d, 1H) 8.01 ppm (s, 0.5H,0.5xH of DMF) 7.9 ppm (d, 1H) 7.1–7.5 ppm (m, 6H) | 4.7 ppm (m, 2H,2xCH) 3.3 ppm (m,5H) 2.9 ppm (s, 1.5H, 0.5x-CH3of DMF) 2.7 ppm (s, 1.5H, 0.5x-CH3of DMF) 2 ppm (m,5H) 1.5 ppm (m,1H) 1.09 ppm (m, 1H) |

| 3 | 13.2(s,2H) | 7.2–7.4 ppm (m, 7H) 8.2 ppm (m, 1H) | 0.8 ppm (m,2H) 1 ppm (m,2H) 1.2 ppm (m,2H) 2.2–1.8 ppm (m,12H) |

| 4 | 13.2 (s,2H) | 7.9 ppm (s, 0.5H,0.5xH of DMF) 7.3–7.6 ppm (m, 6H) 8–8.4 ppm (m, 2H) | 1.2–2 ppm (m,17H) 2.9 ppm (s, 1.5H, 0.5x-CH3of DMF) 2.7 ppm (s, 1.5H, 0.5x-CH3of DMF) 3–3.4 ppm (m,5H) |

| 5 | 13.2 (s,2H) | 8.2–8.4 ppm (m, 2H) 7.4–7.8 ppm (m, 5H) 7.1 ppm (m,1H) | 2.9–3.2 ppm (m,3H) 1.2–2 ppm (m,23H) |

3.2 Biological evaluation

Cytotoxic activities of compounds 1–5 and and the reference compounds cisplatin and carboplatin were determined for the human OVCAR-3 and HeLa cervix cancer cell lines with the MTT assay are shown in Table 2. Cytotoxic activity of the ligands L1–L5 against the OVCAR-3 and HeLa cell lines was also tested, but not observed.

Cytotoxic activities of platinum (II) complexes, cisplatin and carboplatin on the OVCAR-3 and HeLa cells.

| Compounds | C (μM) | OVCAR-3 cells | HeLa cells | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [Inh.% (μM ± SD)] | p-Value | [Inh.% (μM ± SD)] | p-Value | ||

| 1 | 80 160 | 3 ± 1 11.33 ± 1.52 | p>0.05 | 7.67 ± 2.52 15.67 ± 1.15 | p>0.05 |

| 2 | 80 160 | 15 ± 3 42.33 ± 2.51 | p<0.05 | 16.67 ± 0.58 27.33 ± 1.52 | p>0.05 |

| 3 | 80 160 | 27 ± 1.73 66 ± 5.3 | p<0.05 | 14 ± 0 34 ± 0 | p<0.05 |

| 4 | 80 160 | 18 ± 2.64 16.67 ± 3.21 | p>0.05 | 14.33 ± 2.08 24.67 ± 1.15 | p>0.05 |

| 5 | 80 160 | 32 ± 2.08 69 ± 1.15 | p<0.05 | 24.67 ± 1.15 75 ± 1 | p<0.05 |

| Cisplatin | 10 20 40 | 63.67 ± 2.08 80 ± 3 79.33 ± 2.30 | p<0.05 | 9.67 ± 2.08 78.67 ± 0.57 88.66 ± 0.57 | p<0.05 |

| Carboplatin | 10 20 40 80 | 11 ± 1.73 20 ± 2 36.33 ± 0.58 77 ± 1 | p<0.05 | 7 ± 2 14 ± 1 21.67 ± 1.15 35.67 ± 4.04 | p < 0.05 |

Results are expressed as mean ± SD from three independent experiments (Friedman test). p-Values denote significance of difference to control.

The relative cytotoxic potencies of the complexes decreased in the order 5 > 3 > 2, 4 > 1 against the HeLa cell line, and 5, 3 > 2 > 4 > 1 against the OVCAR-3 cell line. Compound 4 was an exception from the general rule that the cytotoxic potency increased with the ring size.

3.3 Cell cycle and apoptosis

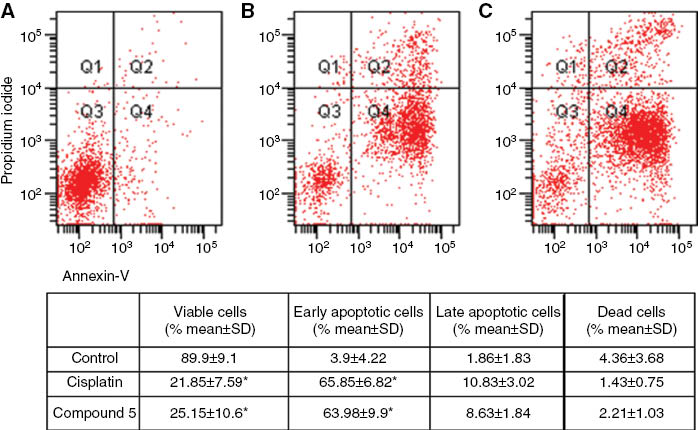

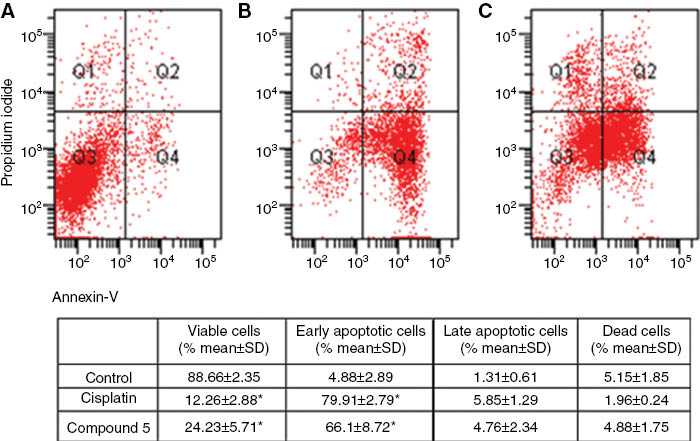

The effect of the most cytotoxic compound 5, on the cell cycle of the two cell lines was studied. Cisplatin, known to cause DNA damage and apoptosis in various human tumor cells [31] was used for comparision. The two cell lines were exposed to 5 and cisplatin at the twofold concentration of the the respective IC50 value for 72 h. In the OVCAR-3 cell line, 5 caused apoptosis in 72 % of the cells under these conditions, comparable to cisplatin (Figure 1), with a preferential arrest in SubG1, while in the HeLa cells 5 was less active than cisplatin (Figure 2).

Apoptosis of OVCAR-3 cancer cells treated with 2 × IC50 concentrations of cisplatin and compound 5 was evaluated by flow cytometry after 72 h using annexin-V/propidium iodide (PI) staining. Quadrant 1 (Q1): dead cells; Quadrant 2 (Q2): late apoptotic and necrotic cells; Quadrant 3 (Q3): viable cells; Quadrant 4 (Q4): early apoptotic cells. (A) Images of dot-plot of Annexin-V/PI staining in untreated cells; (B) staining in OVCAR-3 cells treated with cisplatin; (C) cells treated with compound 5. Results are expressed as mean ± SD from three independent experiments. *Denotes p < 0.05 compared with control (Friedman test–Wilcoxon signed ranks test).

Apoptosis of HeLa cancer cells treated with 2 × IC50 concentrations of cisplatin and compound 5 was evaluated by flow cytometry after 72 h using annexin-V/propidium iodide (PI) staining. Quadrant 1 (Q1): dead cells; Quadrant 2 (Q2): late apoptotic and necrotic cells; Quadrant 3 (Q3): viable cells; Quadrant 4 (Q4): early apoptotic cells. (A) The image of dot-plot of annexin-V/PI staining in untreated cells; (B) Staining in HeLa cells treated with cisplatin; (C) Cells treated with compound 5. Results are expressed as mean ± SD from three independent experiments. *Denotes p < 0.05 compared with control (Friedman test–Wilcoxon signed ranks test).

Compound 5 induced a significant increase in the SubG1 cell population in both OVCAR-3 and HeLa cells compared to the untreated control and cisplatin. This indicates that compound 5 induces sufficient levels of DNA damage (Tables 3 and 4).

Percentage of SubG1 peak and cell cycle distrubition of OVCAR-3 cancer cells untreated (control) and treated with 2 × IC50 concentraton of cisplatin and compound 5 determined after 72 h using cell cycle analysis by flow cytometry.

| OVCAR-3 cells | Apoptosis | Cell cycle phases | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SubG1 (% mean ± SD) | G0/G1 (% mean ± SD) | Synthesis (S) (% mean ± SD) | G2/M (% mean±SD) | |

| Control | 10.40 ± 6.70 | 74.00 ± 6.62 | 5.44 ± 0.46 | 8.64 ± 0.75 |

| Cisplatin | 51.73 ± 2.61* | 28.28 ± 1.81* | 7.90 ± 0.21 | 11.13 ± 0.96 |

| Compound 5 | 53.01 ± 9.68* | 28.63 ± 6.29* | 5.68 ± 1.61 | 11.01 ± 2.40 |

Results are expressed as mean ± SD from three independent experiments. *Denotes p < 0.05 compared with control (Friedman test– Wilcoxon signed ranks test).

Percentage of SubG1 peak and cell cycle distrubition of HeLa cancer cells untreated (control) and treated with 2x IC50 concentraton of cisplatin and compound 5 determined after 72 h using cell cycle analysis by flow cytometry.

| Hela cells | Apoptosis | Cell cycle phases | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SubG1 (% mean ± SD) | G0/G1 (% mean ± SD) | Synthesis (S) (% mean ± SD) | G2/M (% mean ± SD) | |

| Control | 6.53 ± 3.60 | 59.46 ± 5.90 | 26.16 ± 2.21 | 5.63 ± 1.53 |

| Cisplatin | 81.10 ± 4.77* | 12.03 ± 3.34* | 3.93 ± 1.10* | 1.30 ± 0.30 |

| Compound 5 | 80.30 ± 7.59* | 14.20 ± 5.70* | 4.22 ± 1.73* | 0.94 ± 0.35 |

Results are expressed as mean ± SD from three independent experiments. *Denotes p < 0.05 compared with control (Friedman test– Wilcoxon signed ranks test).

Most of the current antineoplastic drugs presently in use block the cell cycle in the S or G2/M phase [32]. Further studies must be done on compound 5.

4 Conclusion

The cytotoxicities of the five new Pt(II) complexes were less than that of cisplatin and comparable to carboplatin, but 5 with the 2-cycloheptyl-benzimidazole ring as carrier ligand was more active than carboplatin against the HeLa cancer cell line. Because of this, apoptosis and cell cycle studies were carried on compound 5, and further studies will be continued on this compound.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Research Foundation of Gazi University (02/2011-33, 02/2012-15 and 02/2012-19).

Conflict of interest statement: The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest to disclose.

References

1. Sadler PJ. Protein recognition of platinated DNA. Chem Bio Chem 2009;10:73–4.10.1002/cbic.200800733Search in Google Scholar

2. Jakupec MA, Galanski M, Arion VB, Hartinger CG, Keppler BK. Antitumour metal compounds: more than theme and variations. Dalton Trans 2008;2:183–94.10.1039/B712656PSearch in Google Scholar

3. Aris SM, Farrell NP. Towards antitumor active trans-platinum compounds. Eur J Inorg Chem 2009;1293–302.10.1002/ejic.200801118Search in Google Scholar

4. Alderden RA, Hall MD, Hambley TW. The discovery and development of cisplatin. J Chem Educ 2006;5:728–34.10.1021/ed083p728Search in Google Scholar

5. Lakomska I, Fandzloch M, Wietrzyk J. Structure-cytotoxicity relationship for different types of mononuclear platinum(II) complexes with 5,7-diterbutyl-1,2,4-triazolo[1,5-a]pyrimidine. J Inorg Biochem 2012;115:100–5.10.1016/j.jinorgbio.2012.05.005Search in Google Scholar

6. Lee S, Choi E, Jin C, Kim D. Activation of PI3K/Akt pathway by PTEN reduction and PIK3CAmRNA amplification contributes to cisplatin resistance in an ovarian cancer cell line. Gynecol Oncol 2005;97:26–34.10.1016/j.ygyno.2004.11.051Search in Google Scholar

7. Kelland LR, Sharp SY, O’Neill CF, Raynaud FI, Beale PJ, Judson IR. Mini review: discovery and development of platinum complexes designed to circumvent cisplatin resistance. J Inorg Biochem 1999;77:111–5.10.1016/S0162-0134(99)00141-5Search in Google Scholar

8. Zakovska A, Novakova O, Balcarova Z, Bierbach U, Farrell N, Brabec V. DNA ınteractions of antitumor trans-[PtCl2(NH3)(quinoline)]. Eur J Biochem 1998;254:547–557.10.1046/j.1432-1327.1998.2540547.xSearch in Google Scholar PubMed

9. Eastman A. The mechanism of action of cisplatin: from adducts to apoptosis. cisplatin: chemistry and biochemistry of leading anticancer drug. Verlag Helv Chim Acta Zürich 1999;111–34.10.1002/9783906390420.ch4Search in Google Scholar

10. Jung Y, Lippard SJ. Direct cellular responses to platinum-ınduced damage. Chem Rev 2007;107:1387–407.10.1021/cr068207jSearch in Google Scholar PubMed

11. Fuertes MA, Alonso C, Perez M. Biochemical modulation of cisplatin mechanisms of action: enhancement of antitumor activity and circumvention of drug resistance. Chem Rev 2003;103:645–62.10.1021/cr020010dSearch in Google Scholar

12. Marques MP. Platinum and palladium polyamine complexes as anticancer agents: the structural factor. ISRN Spectroscopy 2013;2013:1–29.10.1155/2013/287353Search in Google Scholar

13. Gümüş F, Demirci AB, Özden T, Eroğlu H, Diril N. Synthesis, characterization and mutagenicity of new cis-[Pt(2-substitutedbenzimidazole)2Cl2] complexes. Die Pharmazie 2003;58:303–7.Search in Google Scholar

14. Gümüş F, Pamuk İ, Özden T, Yıldız S, Diril N, Öksüzoğlu E, et al. Synthesis, characterization and in vitro cytotoxic, mutagenic and antimicrobial activity of platinum(II)complexes with the substitutedbenzimidazole ligands. J Inorg Biochem 2003;94:255–62.10.1016/S0162-0134(03)00005-9Search in Google Scholar

15. Gümüş F, Eren G, Açık L, Çelebi A, Öztürk F, Yılmaz Ş, et al. Synthesis, cytotoxicty and DNA ınteractions of new cisplatin analogues containing substitutedbenzimidazole ligands. J Med Chem 2009;52:1345–57.10.1021/jm8000983Search in Google Scholar

16. Utku S, Gümüş F, Tezcan S, Serin MS, Ozkul A. Synthesis, characterization, cytotoxicity and DNA binding of some new platinum(II) and platinum(IV) complexes with benzimidazole ligands. J Enzym Inhib Med Chem 2010;25:502–8.10.3109/14756360903282858Search in Google Scholar

17. Utku S, Özçelik AB, Gümüş F, Yılmaz Ş, Arsoy T, Açık L, et al. Synthesis, in vitro cytotoxic activity and DNA interactions of new dicarboxylatoplatinum(II) complexes with 2-hydroxymethylbenzimidazole as carrier ligands. J Pharm Pharmacol 2014;66:1593–605.10.1111/jphp.12290Search in Google Scholar

18. Özçelik AB, Utku S, Gümüş F, Keskin AÇ, Açık L, Yılmaz Ş, et al. Cytotoxicity and DNA ınteractions of some platinum(II) complexes with substituted benzimidazole ligands. J Enzym Inhib Med Chem 2012;3:1–6.10.3109/14756366.2011.594046Search in Google Scholar

19. Utku S, Gümüş F, Gür S, Özkul A. Synthesis and cytotoxic activity of platinum(II) and platinum(IV) complexes with 2-hydroxymethylbenzimidazole or 5(6)-chloro-2-hydroxymethylbenzimidazole ligands against mcf-7 and hela cell line. Turk J Chem 2007;31:503–14.Search in Google Scholar

20. Utku S, Gümüş F, Karaoğlu T, Özkul A. Cytotoxic activity of platinum(II) and platinum(IV)complexes bearing 5(6)-non/chlorosubstituted-2-hydroxymethyl benzimidazole ligands against hep-2cell line. J Fac Pharm 2007;36:21–30.Search in Google Scholar

21. Gümüş F, Algül Ö. DNA Binding Studies with cis-dichlorobis[5(6) non/chlorosubstituted-2-hydroxymethylbenzimidazole]platinum(II) Complexes. J Inorg Biochem 1997;68:71–4.10.1016/S0162-0134(97)00041-XSearch in Google Scholar

22. Gökçe M, Utku S, Gür S, Özkul A, Gümüş F. Synthesis, in vitro cytotoxic and antiviral activity of cis-[Pt(R)(- and S)+(-2-α-hydroxybenzylbenzimidazole)2Cl2] complexes. Eur J Med Chem 2005;40:135–41.10.1016/j.ejmech.2004.09.017Search in Google Scholar PubMed

23. Phillips MA. The formation of 2-substitutedbenzimidazoles. J Chem Soc 1928;2393–2399.10.1039/JR9280002393Search in Google Scholar

24. Pellicciari R, Fringuelli R, Natalini B, Brucato L, Contessa AR. Homolytic substitution and carbenoidic reactions in the preparation of benzimidazole derivates of pharmaceutical ınterest. Synthesis and properties of (2-Cycloalkyl-1-benzimidazolyl)-N,N-diethylacetamides. Arch Pharm 1985;318:393–9.10.1002/ardp.19853180503Search in Google Scholar

25. Nagawade RR, Shinde DB. Zirconyl(IV)cloride-promoted synthesis of benzimidazole derivates. Russ J Organ Chem 2006;42:453–4.10.1134/S1070428006030201Search in Google Scholar

26. Takao O, Shinich A. Water-soluble prefluxes, printed circuit boards, and surface treatment of metal surface thereof. Jpn Kokai Tokky Koho JP 09176871 A 19970708, 1997.Search in Google Scholar

27. Ural AU, Avcu F, Candir M, Guden M, Ozcan MA. In vitro synergistic cytoreductive effects of zoledronic acid and radiation on breast cancer cells. A Breast Cancer Res 2006;8:1–7.10.1186/bcr1543Search in Google Scholar

28. Mylonas S, Valavanidis A, Voukouvalidis V, Polyssiou M. Platinum(II) and palladium(II) complexes with amino acid derivatives. synthesis, ınterpretation of ır and 1h-nmr spectra and conformational ımplications. Inorg Chim Acta 1981;55:125–8.10.1016/S0020-1693(00)90793-XSearch in Google Scholar

29. Kammermeier T, Wiegrebe W. 1H-NMR and IR spectroscopic data of 1,3 diphenylpropane-1,3-diamines and their Pt(II) complexes: stereochemical assigments and binding mode of the non-amine ligands. Arch Pharm 1994;327:697–707.10.1002/ardp.19943271105Search in Google Scholar

30. Lippert B. Platinum nucleobase chemistry. Prog Inorg Chem 1989;37:1–97.10.1002/9780470166383.ch1Search in Google Scholar

31. Vakifahmetoglu H, Olsson M, Tamm C, Heidari N, Orrenius S, Zhivotovsky B. DNA Damage ınduces two distinct modes of cell death in ovarian carcinomas. Cell Death Differ 2008;15:555–66.10.1038/sj.cdd.4402286Search in Google Scholar PubMed

32. Ramos-Lima FJ, Moneo V, Quiroga AG, Carneo A, Navarro-Ranninger C. The role of p53 in the cellular toxicity by active trans-platinum complexes containing ısopropylamine and hydroxymethylpyridine. Eur J Med Chem 2010;45:134–41.10.1016/j.ejmech.2009.09.035Search in Google Scholar PubMed

©2015 by De Gruyter

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Chemical characterization, antioxidant and cytotoxic activities of the methanolic extract of Hymenocrater longiflorus grown in Iraq

- Preventive effect of total glycosides from Ligustri Lucidi Fructus against nonalcoholic fatty liver in mice

- Synthesis of platinum(II) complexes of 2-cycloalkyl-substituted benzimidazoles and their cytotoxic effects

- cDNA cloning and functional characterisation of four antimicrobial peptides from Paa spinosa

- Evaluation of the water soluble extractive of astragali radix with different growth patterns using 1H-NMR spectroscopy

- SPME collection and GC-MS analysis of volatiles emitted during the attack of male Polygraphus poligraphus (Coleoptera, Curcolionidae) on Norway spruce

- Selective nematocidal effects of essential oils from two cultivated Artemisia absinthium populations

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Chemical characterization, antioxidant and cytotoxic activities of the methanolic extract of Hymenocrater longiflorus grown in Iraq

- Preventive effect of total glycosides from Ligustri Lucidi Fructus against nonalcoholic fatty liver in mice

- Synthesis of platinum(II) complexes of 2-cycloalkyl-substituted benzimidazoles and their cytotoxic effects

- cDNA cloning and functional characterisation of four antimicrobial peptides from Paa spinosa

- Evaluation of the water soluble extractive of astragali radix with different growth patterns using 1H-NMR spectroscopy

- SPME collection and GC-MS analysis of volatiles emitted during the attack of male Polygraphus poligraphus (Coleoptera, Curcolionidae) on Norway spruce

- Selective nematocidal effects of essential oils from two cultivated Artemisia absinthium populations