Abstract

Lectins, a group of highly diverse proteins of non-immune origin and are ubiquitously distributed in plants, animals and fungi, have multiple significant biological functions, such as anti-fungal, anti-viral and, most notably, anti-tumor activities. A lectin was purified from the rhizomes of Aspidistra elatior Blume, named A. elatior lectin (AEL). In vitro experiments showed that the minimum inhibitory concentrations of AEL against the vesicular stomatitis virus, Coxsackie virus B4, and respiratory syncytial virus were all the same at about 4 μg/mL. However, AEL was ineffective against the Sindbis virus and reovirus-1. AEL also showed significant in vitro antiproliferative activity towards Bre-04, Lu-04, HepG2, and Pro-01 tumor cell lines by increasing the proportion of their sub-G1 phase. However, AEL failed to restrict the proliferation of the HeLa cell line. Western blotting indicated that AEL induced the upregulation of cell cycle-related proteins p53 and p21. The molecular basis and species-specific effectiveness of the anti-proliferative and anti-viral potential of AEL are discussed.

1 Introduction

Lectins, a group of highly diverse proteins of non-immune origin and are ubiquitously distributed in plants, animals and fungi, contain at least one non-catalytic domain, enabling them to selectively recognize and reversibly bind to specific free sugars or glycans present on glycoproteins and glycolipids without altering the structure of the carbohydrate [1, 2].

Most plant lectins can cause the programmed death of tumor cells by targeting both apoptotic and autophagic pathways [3]. TNF (tumor necrosis factor)-family [4], caspase-8 [5], mitochondrial membrane potential (MMP), caspase-3, apoptosis-associated factor-1 (Apaf-1) [6], Bcl-2 (B-cell lymphoma 2) family [7], MAPK (mitogen-activated protein kinase) signaling [8], SAPK (stress-activated protein kinase)/JNK(c-Jun N-terminal kinase) and p38 pathways, ERK (extracellular signal-regulated kinase) 1/2 pathway [9], and XIAP (X-linked inhibitor of apoptosis protein) [10] participate in lectin-induced autophagy. However, this activation of apoptosis is independent of p53 or p21 [11]. LC3 (microtubule-associated protein1 light chain 3)-II, BNIP3 (Bcl2/adenovirus E1B 19 kDa-interacting protein 3) [12], and ROS-p38-p53 [13] participate in lectin-induced apoptosis. The PI3K (phosphatidylinositol 3 kinase)-Akt (protein kinase B) pathway has been reported to act as negative regulator in lectin-induced autophagic cell death [14].

A few lectins, including those from Helix pomatia [15] and Agaricus bisporus [16], have been investigated for their use in tumor research and clinical therapy. As an important superfamily, monocot mannose-binding lectins have been isolated and characterized from various monocot families, including Liliaceae, Alliaceae, Orchidaceae, Amaryllidaceae, and Araceae [1]. Aspidistra elatior Blume, a member of Liliaceae, is a traditional Chinese medicinal herb and ornamental plant species. Its rhizomes and leaves trigger diuresis, abirritation, and detumescence in certain illnesses. For a long time, it has been used in China to cure injuries from falls, as well as rheumatic fever and rheumatism. In recent years, research into its biochemical constituents has mainly focused on the steroidal compounds [17]. However, there has been no report on the bioactivities of lectin(s) from A. elatior on tumor cell cycle or virus replication. In our previous report, a lectin was purified from the rhizomes of A. elatior Blume, named A. elatior lectin (AEL). Its mannose-binding property and hemagglutinating activity were also studied [18]. In the work presented here, the antiviral and antitumor activities of AEL are further investigated. Possible anti-proliferative and anti-viral mechanisms are also discussed.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Plant material, cell lines, virus strains, chemicals and reagents

The rhizomes of A. elatior Blume were collected on the campus of Sichuan University (Chengdu, China) in August. The Vero cell line (African green monkey kidney) and human tumor cell lines Pro-01 (prostate), Lu-04 (lung), Bre-04 (breast), HepG2 (liver), Hep3B (p53-null; liver), and HeLa (cervix) were purchased from Di’ao Group (Chengdu, China).

Vesicular Stomatitis Virus, Coxsacke Virus B4, Respiratory Syncytial Virus, Sindbis Virus, and Reovirus-1 were provided by the Medical Sciences Center of West China, Sichuan University, China. Meanwhile, (S)-9-(2,3-Dihydroxypropyl)adenine [(S)-DHPA] and ribavirin were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA). Carboxymethyl SepharoseTM and SephacrylTM S-100 were purchased from Pharmacia (Uppsala, Sweden).

2.2 Purification of agglutinin from rhizomes of A. elatior

The procedure of Xu et al. [18] was followed. In brief, the 80% ammonium sulfate saturated crude protein extract from A. elatior Blume rhizomes, after dialysis against 20 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0), was applied to a diethylaminoethyl-Sepharose column equilibrated with the same buffer. Then, the proteins were eluted with a linear 0–0.5 M NaCl gradient. The fractions showing hemagglutinating activity were pooled, concentrated to approximately 4 mg/mL and then loaded on a Sephacryl S-100 column (2 cm×100 cm) equilibrated with 10 mM phosphate-buffered saline (PBS; pH 7.2).

2.3 Homogeneity of AEL and determination of molecular mass

Sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) was carried out in 15% (w/v) acrylamide gels. Protein bands were visualized by Coomassie Brilliant Blue R-250 staining. The molecular mass of the native lectin was determined to be 56 kDa by gel filtration chromatography on the same Sephacryl S-100 column that had been used for purification (see above). Two adjacent bands of 13.5 kDa and 14.5 kDa were seen in SDS-PAGE, representing the two subunits of AEL [18].

2.4 Anti-viral assay

Vero cells were grown in RPMI medium supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum (FCS), 100 μg/mL penicillin (Chongqing Yaoyou Pharmaceutical Co., China), and 100 μg/mL streptomycin (Shanghai 4th Pharmaceutical Co.). Vero cells were seeded onto a 96-well plate with a concentration of 5×104 cells per mL and a volume of 20 μL per well. After incubation at 37 °C with 5% CO2 for 1 h, cells were then washed three times with phosphate buffered saline (PBS). Different concentrations of virus samples were then added to the cultures well in 1–106 dilutions. AEL samples and other drugs were serially diluted with PBS, after which aliquots of each dilution were adsorbed on a Vero cell monolayer. At the end of the adsorption, the virus inoculum was removed and cells were replenished with fresh medium. After incubation at 37 °C with 5% CO2 for 72 h, cells were observed and examined by a light microscopy. Virus replication in infected cells was assessed by the 50% tissue culture infection dose (TCID50) [19].

2.5 In vitro anti-proliferative potential of AEL against human tumor cell lines

The inhibitory potential of AEL against various human tumor cell lines (Pro-01, Lu-04, Bre-04, HepG2, Hep3B, and HeLa) was trested using the method of Kaur et al. [20]. Cells were seeded at 104 cells/well in 100 μL of RPMI 1640 medium containing 10% FCS in a 96-well tissue culture plate. Next, cells were suspended as single cells in the medium and incubated for 24 h in a CO2 incubator. Subsequently, 100 μL of lectin solution (50 μg/mL), prepared in RPMI 1640 medium, was added to the cells, and the cultures were incubated for 48 h. After the incubation period, adherent cells were fixed in situ by adding 50 μL of 50% (v/v) trichloroacetic acid (final concentration 10%) and incubated for 1 h at 4 °C. Next, the supernatant was discarded and the plates were washed five times with deionized water before allowing them to dry. About 100 μL of sulforhodamine B (0.4% w/v in acetic acid) were added to each well, and the cultures were incubated for 30 min at room temperature. The unbound sulforhodamine was removed by washing with 1% acetic acid and the plates were air-dried. The dye bound to basic amino acids of the cell membrane was solubilized with Tris buffer (10 mM, pH 10.5), and the absorption was measured at 540 nm using an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay reader. This was done to determine the relative viability in the treated and untreated cells.

2.6 Cell cycle measurement

Tumor cells were treated with or without 10 μg/mL AEL at 37 °C for 24 h and then harvested. FACScan flow cytometry was performed as previously described [21]. The percentages of cells at different cell cycle phases, or those that were undergoing apoptosis, were evaluated using Calibur FACScan flow cytometry (Becton Dickinson, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA).

2.7 Western blot analysis

After treatments, tumor cells were collected and the cell pellets were resuspended in lysis buffer and lysed at 4 °C for 1 h. The lysis buffer consisted of 50 mM Hepes, pH 7.4, 1% Triton X-100, 2 mM sodium orthovanadate, 100 mM sodium fluoride, 1 mM acetic acid, 1 mM phenylmethanesulfonyl fluoride (PMSF), 10 mg/L aprotinin, and 10 mg/L leupeptin (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA). After centrifugation at 12,000 g for 15 min, the supernatant protein content was determined using the Bio-Rad DC protein assay (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA, USA). Equal amounts of total protein were separated by 12% SDS-PAGE and transferred to nitrocellulose membranes, after which the membranes were soaked in blocking buffer (5% skim milk). Antibodies against p21, p53, and actin B were purchased from Santa Cruz Biotech (Santa Cruz, CA, USA). Proteins were visualized using horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated anti-rabbit or anti-mouse IgG and 3,3-diaminobenzidine tetrahydrochloride (DAB) as the HRP substrate [22].

2.8 Statistical analysis

All results presented here were confirmed in at least three independent experiments. Data were expressed as mean±SD. Statistical comparisons were made by Student’s t-test, and the least-significant difference (LSD) test was used to estimate significant differences between the mean values of the treatments. A value of p<0.05 was considered statistically significant.

3 Results

3.1 Anti-virus activity of AEL

On the one hand, treatments with 20 μg/mL AEL caused microscopically detectable alterations of the normal cell morphology, thus indicating cytotoxicity. The minimum inhibitory concentrations (to reduce virus-induced cytopathogenicity by 50%) of AEL against Vesicular Stomatitis Virus, Coxsackie Virus B4, and Respiratory Syncytial Virus were all the same at about 4 μg/mL. On the other hand, AEL was rather ineffective against Sindbis Virus and Reovirus-1 (Table 1). The minimum inhibitory concentrations for these two viruses were higher than 100 μg/mL (the minimum cytotoxic concentration; therefore, higher concentrations of AEL were not used).

Antiviral effects of AEL on several viruses in vitro.

| Drugs, μg/mL | Minimum inhibitory concentration | Minimum cytotoxic concentration | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vesicular stomatitis virus | Coxsackie virus B4 | Respiratory syncytial virus | Sindbis virus | Reovirus-1 | ||

| AEL | 4±1a | 4±1a | 4±1a | >100c | >100c | 100±10b |

| (S)-DHPA | 30±5a | 140±15c | 70±10b | 210±30c | 150±20c | 500±50d |

| Ribavirin | 7±1a | 40±5b | 3±1a | 60±5b | 40±5b | 1000±100c |

Virus minimum inhibitory concentration (±SD) means the concentration required to reduce virus-induced cyto-pathogenicity by 50%. Minimum cytotoxic concentration (±SD) means the required concentration to cause a microscopically detectable alteration of the normal cell morphology. Means within a single line followed by the same letter were not significantly different according to Duncan’s multiplication range test at the 5% level.

Minimum inhibitory concentrations of two anti-viral drugs, (S)-DHPA [23] and ribavirin [24], were higher than those of AEL. The concentrations varied for the different viruses, but the variation patterns differed from that of AEL (Table 1). (S)-DHPA and ribavirin are ribonucleoside analogs that directly inhibit viral RNA polymerase activity [24], whereas AEL may inhibit virus replication through different mechanisms (see Discussion for details).

3.2 Observation of cellular morphology

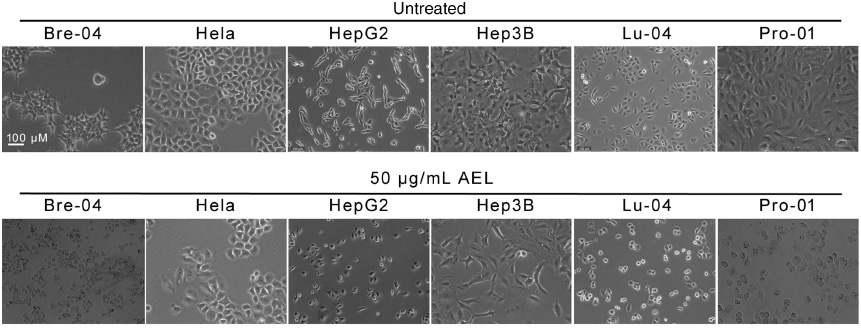

Marked apoptotic morphological changes, such as membrane blebbing, cell volume reduction and rounding, were obvious in AEL-treated Bre-04, Lu-04, HepG2, and Pro-01 cells (Figure 1). However, AEL did not cause apoptotic morphology in HeLa or Hep3B cells (Figure 1). These results indicate that AEL selectively induced apoptosis in Bre-04, Lu-04, HepG2 and Pro-01 cells, but not in HeLa or p53-deficient Hep3B cells, respectively.

Effects of AEL on the morphology of human tumor cell lines.

The indicated human tumor cells were treated with or without 50 μg/mL AEL for 24 h, and their morphologies were examined under a phase contrast microscopy. We used size bar in one of the panels.

3.3 In vitro anti-proliferative potential of AEL on human tumor cell lines

The anti-proliferative effect of the lectin on human tumor cells was determined over a range of 10–50 μg/mL. At 50 μg/mL, AEL had the highest anti-proliferative effect against Bre-04 (76%), followed by Lu-04, HepG2 and Pro-01, in which 72%, 68% and 61% growth inhibitions were observed, respectively, at the 5th day (Figure 2). At a concentration of 25 μg/mL, growth inhibition rates were 58%, 53%, 50%, and 20% for Bre-04, Lu-04, HepG2 and Pro-01, respectively. At 10 μg/mL, the growth inhibitions were 42%, 40%, 28%, and 12% in Bre-04, Lu-04, HepG2 and Pro-01 cells, respectively. At 1 μg/mL, AEL was almost ineffective against all tumor cell lines. The lectin was found to be inactive against the HeLa or p53-deficient Hep3B cell lines at all concentrations and for the entire duration studies (Figure 2). This finding is consistent with the earlier reported variation in the anti-proliferative potential of a variety of lectins with tumor cell lines as a function of their doses [19, 21, 22].

Anti-proliferative effect of 50 μg/mL AEL on human tumor cell lines as a function of time.

Bars indicate SD.

3.4 AEL arrested tumor cell cycles

As demonstrated in Table 2, AEL markedly increased the proportion of the sub-G1 phase in Bre-04, Lu-04, HepG2 and Pro-01 cells, indicating that AEL-induced apoptosis occurred in these tumor cells. Moreover, as evident from Table 2, AEL also triggered G2/M phase cell-cycle arrest. However, AEL neither enhanced the sub-G1 proportion nor triggered G2/M phase cell-cycle arrest in HeLa or p53- deficient Hep3B cells (Table 2).

Effect of 10 μg/mL AEL on the cell cycle of various tumor lines.

| Cell line | AEL± | G0/G1 | G2 | S |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lu-04 | AEL+ | 58.69±6.2a | 21.54±3.3b | 19.77±2.9e |

| AEL- | 52.31±6.8c | 23.68±3.8a | 24.01±3.0c | |

| Bre-04 | AEL+ | 56.73±6.1a | 22.05±3.4b | 21.22±2.7d |

| AEL- | 50.76±7.0b | 24.01±3.6a | 25.23±3.4b | |

| HepG2 | AEL+ | 56.65±6.6a | 22.01±2.9b | 21.34±3.7d |

| AEL- | 51.24±5.9b | 23.98±2.8a | 24.78±3.1b,c | |

| HeLa | AEL+ | 51.81±6.5b | 22.98±2.9a,b | 25.21±3.6b |

| AEL- | 51.16±6.8b | 23.71±3.4a | 25.13±3.4b | |

| Pro-01 | AEL+ | 55.40±5.6a | 21.59±2.7b | 23.01±2.9c |

| AEL- | 50.26±7.1b | 23.53±3.3a | 26.21±3.8a | |

| Hep3B (p53-null) | AEL+ | 57.15±6.2a | 22.36±3.0b | 20.49±3.5d |

| AEL- | 56.98±6.0a | 22.44±2.9b | 20.58±3.3d |

Percentages of each phase of the cell cycle are shown as mean±SD. Means within a single column followed by the same letter were not significantly different according to Duncan’s multiplication range test at the 5% level.

3.5 Analyses of cell cycle related proteins

Due to the AEL-induced arrest of the sub-G1 and G2/M phase, respectively, the levels of cell cycle-related proteins were investigated. Western blot data demonstrated that treatment of Bre-04, Lu-04, HepG2, and Pro-01 cells with AEL resulted in upregulation of p53 (Figure 3). Considering that p53 is an important regulator of p21 [22], p21 levels were also assessed. As seen in Figure 2, p21 was increased in parallel to p53. No p53 and only a trace of p21 could be detected in the p53- deficient Hep3B cell line. Likewise, almost no changes in the levels of p53 and p21 were observed in HeLa or Hep3B cells, indicating their insensitivity to the lectin (Figure 3).

p53 and p21 protein levels of human tumor cells treated with or without 50 μg/mL AEL. Western blots of actin B (ACTB) were used as the loading control.

4 Discussion

AEL2 is a member of the subfamily of strictly mannose-binding lectins, which are widespread among monocotyledonous plants. The monocotyledonous lectin subfamily is well-known to possess a broad range of biological functions [1, 2]. Herein, we mainly focused on exploring the anti-tumor and anti-viral activities of AEL. We further found that AEL affected the cell cycle by promoting p53 and p21 expression.

Some mannose-binding lectins can bind to certain mannose-containing envelope proteins of a virus, blocking virus entry into target cells. This also prevents transmission of the virus and forces the virus to delete the glycan moiety in its envelope protein, thereby triggering the neutralizing antibody [25]. Lectins of the Galanthus nivalis agglutinin (GNA)-related lectin family exhibit significant anti-human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) and anti-herpes simplex virus (HSV) properties that are closely related to their carbohydrate-binding activities [19, 26]. Further comparative analyses indicated that the dimer-based super-structure may play a primary role in the anti-HIV property of PCL [26]. The Yucca filamentosa lectin and the Polygonatum cyrtonema lectin (PCL) may possess anti-influenza properties via competitive binding to viral hemagglutinin (HA)-sialic acid complexes [27]. We may presume that the anti-viral properties of AEL are correlated with its carbohydrate-binding activity, as it is known for other mannose-binding lectins, but this needs to be further investigated.

Virus envelope proteins differ in their glycan groups. The structures of high-mannose N-glycans of virus envelope proteins determine their specific cell targets and their binding to particular types of lectins [28]. AEL was ineffective against Sindbis virus and reovirus-1. Therefore, to achieve broad-spectrum inhibition of a variety of viruses, a combination of different types of lectins may be adopted, but this has been studied only to some extent.

The anti-proliferative effect of AEL on human tumor cells was determined by analyzing their cell cycle and cell-cycle-related proteins. Lectin-induced p53 and p21 expression is tightly correlated with apoptosis in tumor cells [22]. Another example of lectin-induced apoptosis is that concanavalin A (ConA) induced apoptosis in human breast carcinoma MCF-7 cells via downregulation of ERK and JNK and upregulation of p53 and p21 [20]. It has previously been found that p21 is induced by both p53-dependent and -independent mechanisms following stress; furthermore, p21 induction may cause cell cycle arrest [29]. Sophora flavescens lectin (SFL) treatment also decreased ERK and enhanced p53 and p21 expression. SFL has been reported to trigger G2/M phase cell-cycle arrest by upregulating p21 expression and downregulating the expression of cyclin-dependent kinases CDK1 and CDK2 [22]. Ineffectiveness of AEL against the p53-deficient and p21-less Hep3B cells also indicates the involvement of these p53/p21-mediated apoptosis pathways in its action.

However, the cell surfaces of tumors differ in their carbohydrate-containing macromolecules. The surface properties of tumor cells play a major role in tumor growth at the primary site, invasion into surrounding host tissue as well as dissemination, embolization, implantation at distant secondary sites to form metastases; they also determine the binding activities to particular types of lectins [30]. Thus, AEL significantly inhibited the proliferation of Bre-04, Lu-04 and HepG2 cells, but failed to inhibit the proliferation of the HeLa cell line.

In conclusion, AEL is a novel lectin with a low degree of similarity to other mannose-binding lectins from Liliaceae, Amaryllidaceae, Orchidaceae, and Alliaceae. It manifests potent anti-proliferative activity to human cancer cell lines and exhibits anti-virus activities. Further investigations are necessary to unravel the molecular basis of the anti-proliferative and anti-viral effects of the lectin.

Acknowledgments

We wish to thank Dr. Dawei Zhang (Iowa State University, Ames, IA, USA) for language improvement. This work was supported by the Sichuan Natural Science Foundation (13ZB0296 and 014z1700) and the National Natural Science Foundation of China (31300207, 81173093, and J1103518).

References

1. Van Damme EJ, Peumans WJ, Barre A, Rouge P. Plant lectins: a composite of several distinct families of structurally and evolutionary related proteins with diverse biological roles. Crit Rev Plant Sci 1998;17:575–692.10.1016/S0735-2689(98)00365-7Suche in Google Scholar

2. Liu Z, Luo Y, Zhou TT, Zhang WZ. Could plant lectins become promising anti-tumour drugs for causing autophagic cell death? Cell Prolif 2013;46:509–15.10.1111/cpr.12054Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

3. Fu LL, Zhou CC, Yao S, Yu JY, Liu B, Bao JK. Plant lectins: targeting programmed cell death pathways as antitumor agents. Int J Biochem Cell Biol 2011;43:1442–9.10.1016/j.biocel.2011.07.004Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

4. Hoessli DC, Ahmad I. Mistletoe lectins: carbohydrate-specific apoptosis inducers and immunomodulators. Curr Org Chem 2008;12:918–25.10.2174/138527208784892196Suche in Google Scholar

5. Bantel H, Engels IH, Voelter W, Schulze-Osthoff K, Wesselborg S. Mistletoe lectin activates caspase-8/FLICE independently of death receptor signaling and enhances anticancer drug-induced apoptosis. Cancer Res 1999;59:2083–90.Suche in Google Scholar

6. Hostanska K, Vuong V, Rocha S, Soengas MS, Glanzmann C, Saller R, et al. Recombinant mistletoe lectin induces p53- independent apoptosis in tumor cells and cooperates with ionizing radiation. Br J Cancer 2003;88:1785–92.10.1038/sj.bjc.6600982Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

7. Sunayama J, Tsuruta F, Masuyama N, Gotoh Y. JNK antagonizes Akt-mediated survival signals by phosphorylating 14-3-3. J Cell Biol 2005;170:295–304.10.1083/jcb.200409117Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

8. De Mejia EG, Dia VP. The role of nutraceutical proteins and peptides in apoptosis, angiogenesis, and metastasis of cancer cells. Cancer Metast Rev 2010;29:511–28.10.1007/s10555-010-9241-4Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

9. Pae HO, Oh GS, Kim NY, Shin MK, Lee HS, Yun YG, et al. Roles of extracellular signal-regulated kinase and p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase in apoptosis of human monoblastic leukemia U937 cells by lectin-II isolated from Korean mistletoe. In Vitro Mol Toxicol 2001;14:99–106.10.1089/10979330152560496Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

10. Khil LY, Kim W, Lyu S, Park WB, Yoon JW, Jun HS. Mechanisms involved in Korean mistletoe lectin-induced apoptosis of cancer cells. World J Gastroenterol 2007;13:2811–8.10.3748/wjg.v13.i20.2811Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

11. Lyu SY, Choi SH, Park WB. Korean mistletoe lectin-induced apoptosis in hepatocarcinoma cells is associated with inhibition of telomerase via mitochondrial controlled pathway independent of p53. Arch Pharm Res 2002;25:93–101.10.1007/BF02975269Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

12. Lei HY, Chang CP. Lectin of Concanavalin A as an anti-hepatoma therapeutic agent. J Biomed Sci 2009;16:10.10.1186/1423-0127-16-10Suche in Google Scholar

13. Liu B, Cheng Y, Bian HJ, Bao JK. Molecular mechanisms of Polygonatum cyrtonema lectin-induced apoptosis, autophagy in cancer cells. Autophagy 2009;5:253–5.10.4161/auto.5.2.7561Suche in Google Scholar

14. Liu B, Bian HJ, Bao JK. Plant lectins: potential antineoplastic drugs from bench to clinic. Cancer Lett 2010;287:1–12.10.1016/j.canlet.2009.05.013Suche in Google Scholar

15. Schumacher U, Higgs D, Loizidou M, Pickering R, Leathem A, Taylor I. Helix pomatia agglutinin binding is a useful prognostic indicator in colorectal carcinoma. Cancer 1994;74:3104–7.10.1002/1097-0142(19941215)74:12<3104::AID-CNCR2820741207>3.0.CO;2-0Suche in Google Scholar

16. Parslew R, Jones KT, Rhodes JM, Sharpe GR. The antiproliferative effect of lectin from the edible mushroom (Agaricus bisporus) on human keratinocytes: Preliminary studies on its use in psoriasis. Br J Dermatol 1999;140:56–60.10.1046/j.1365-2133.1999.02607.xSuche in Google Scholar

17. Chen MQ, Sichuanensis KY, Lang Y. Steroidal glycosides from Aspidistra. Nat Prod Res Dev 1995;7:19–22.Suche in Google Scholar

18. Xu XC, Wu CF, Liu C, Luo YT, Li J, Zhao XP, et al. Purification and characterization of a mannose-binding lectin from the rhizomes of Aspidistra elatior Blume with antiproliferative activity. Acta Biochim Biophys Sin 2007;39:507–19.10.1111/j.1745-7270.2007.00305.xSuche in Google Scholar

19. Yang Y, Xu HL, Zhang ZT, Liu JJ, Li WW, Ming H, et al. Characterization, molecular cloning, and in silico analysis of a novel mannose-binding lectin from Polygonatum odoratum (Mill.) with anti-HSV-II and apoptosis-inducing activities. Phytomedicine 2011;18:748–55.10.1016/j.phymed.2010.11.001Suche in Google Scholar

20. Kaur M, Singh K, Rup PJ, Saxena AK, Khan RH, Ashraf MT, et al. A tuber lectin from Arisaema helleborifolium Schott with anti-insect activity against melon fruit fly Bactrocera cucurbitae (Coquillett) and anti-cancer effect on human cancer cell lines. Arch Biochem Biophys 2006;445:156–65.10.1016/j.abb.2005.10.021Suche in Google Scholar

21. Li CY, Wang Y, Wang HL, Shi Z, An N, Liu YX, et al. Molecular mechanisms of Lycoris aurea agglutinin-induced apoptosis and G2/M cell cycle arrest in human lung adenocarcinoma A549 cells, both in vitro and in vivo. Cell Prolif 2013;46:272–82.10.1111/cpr.12034Suche in Google Scholar

22. Shi Z, Chen J, Li CY, An N, Wang ZJ, Yang SL, et al. Antitumor effects of concanavalin A and Sophora flavescens lectin in vitro and in vivo. Acta Pharmacol Sin 2014;35:248–56.10.1038/aps.2013.151Suche in Google Scholar

23. Brabcová J, Blažek J, Janská L, Krečmerová M, Zarevúcka M. Lipases as tools in the synthesis of prodrugs from racemic 9-(2,3-dihydroxypropyl)adenine. Molecules 2012;17:13813–24.10.3390/molecules171213813Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

24. Yuan S. Drugs to cure avian influenza infection – multiple ways to prevent cell death. Cell Death Dis 2013;4:e835.10.1038/cddis.2013.367Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

25. Wu L, Bao JK. Anti-tumor and anti-viral activities of Galanthus nivalis agglutinin (GNA)-related lectins. Glycoconj J 2013;30:269–79.10.1007/s10719-012-9440-zSuche in Google Scholar PubMed

26. Ding J, Bao J, Zhu D, Zhang Y, Wang DC. Crystal structures of a novel anti-HIV mannose-binding lectin from Polygonatum cyrtonema Hua with unique ligand-binding property and super-structure. J Struct Biol 2010;171:309–17.10.1016/j.jsb.2010.05.009Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

27. Xu HL, Li CY, He XM, Niu KQ, Peng H, Li WW, et al. Molecular modeling, docking and dynamics simulations of GNA-related lectins for potential prevention of influenza virus (H1N1). J Mol Model 2012;18:27–37.10.1007/s00894-011-1022-7Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

28. Morizono K, Ku A, Xie Y, Harui A, Kung SK, Roth MD, et al. Redirecting lentiviral vectors pseudotyped with Sindbis virus-derived envelope proteins to DC-SIGN by modification of N-linked glycans of envelope proteins. J Virol 2010;84: 6923–34.10.1128/JVI.00435-10Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

29. Gartel AL, Tyner AL. The role of the cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor p21 apoptosis. Mol Cancer Ther 2002;1:639–49.Suche in Google Scholar

30. Rambaruth ND, Dwek MV. Cell surface glycan-lectin interactions in tumor metastasis. Acta Histochem 2011;113: 591–600.10.1016/j.acthis.2011.03.001Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

©2015 by De Gruyter

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Frontmatter

- Larvicidal activity of the essential oil of Youngia japonica aerial parts and its constituents against Aedes albopictus

- Antiviral and antitumor activities of the lectin extracted from Aspidistra elatior

- Susceptibility of Microsporum canis arthrospores to a mixture of chemically defined essential oils: a perspective for environmental decontamination

- Central analgesic activity of the aqueous and ethanolic extracts of the leaves of Albizia lebbeck: role of the GABAergic and serotonergic pathways

- Three further triterpenoid saponins from Gleditsia caspica fruits and protective effect of the total saponin fraction on cyclophosphamide-induced genotoxicity in mice

- Acylated flavonol diglucosides from Ammania auriculata

- Synthesis and antimicrobial properties of N-substituted derivatives of (E)-2′,3″-thiazachalcones

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Frontmatter

- Larvicidal activity of the essential oil of Youngia japonica aerial parts and its constituents against Aedes albopictus

- Antiviral and antitumor activities of the lectin extracted from Aspidistra elatior

- Susceptibility of Microsporum canis arthrospores to a mixture of chemically defined essential oils: a perspective for environmental decontamination

- Central analgesic activity of the aqueous and ethanolic extracts of the leaves of Albizia lebbeck: role of the GABAergic and serotonergic pathways

- Three further triterpenoid saponins from Gleditsia caspica fruits and protective effect of the total saponin fraction on cyclophosphamide-induced genotoxicity in mice

- Acylated flavonol diglucosides from Ammania auriculata

- Synthesis and antimicrobial properties of N-substituted derivatives of (E)-2′,3″-thiazachalcones