Abstract

The aim of this study was to evaluate the larvicidal activity of the essential oil of Youngia japonica aerial parts against the larvae of Aedes albopictus and to isolate any active compounds from the oil. Gas chromatography-mass spectrometry (GC-MS) analyses revealed the presence of 31 compounds, with menthol (23.53%), α-asarone (21.54%), 1,8-cineole (5.36%), and caryophyllene (4.45%) as the major constituents. Bioactivity-directed chromatographic separation of the oil led to the isolation of menthol and α-asarone as active compounds. The essential oil of Y. japonica exhibited larvicidal activity against the fourth instar larvae of A. albopictus with an LC50 value of 32.45 μg/mL. α-Asarone and menthol possessed larvicidal activity against the fourth instar larvae of A. albopictus with LC50 values of 24.56 μg/mL and 77.97 μg/mL, respectively. The results indicate that the essential oil of Y. japonica aerial parts and the two constituents can be potential sources of natural larvicides.

1 Introduction

Mosquito control is a vital public health practice throughout the world, and especially so in the tropics, because mosquitoes spread many diseases (e.g., malaria), viral pathogens (e.g., yellow fever, several forms of encephalitis, and Chikungunya fever), and several filarial nematodes. The Asian tiger mosquito, Aedes albopictus Skuse (Stegomyia albopictus) (Diptera: Culicidae) and the yellow fever mosquito (A. aegypti L.) are two main species of mosquito responsible for dengue fever in China [1]. Current methods to control mosquito larvae and pupae depend on the usage of synthetic chemical insecticides, such as organophosphates (e.g., temephos, fenthion, and malathion), and insect growth regulators, such as diflubenzuron and methoprene. However, heavy and repeated usage of these synthetic pesticides disrupt natural biological control systems, sometimes resulting in the widespread development of resistance and undesirable effects on non-target organisms and workers’ safety, presence of toxic residues in food, and high cost of procurement [2]. Thus, there is an urgent need to develop new materials for controlling mosquitoes using environmentally safe methods that feature biodegradable and target-specific insecticides against them.

Essential oils and their constituents have been suggested as alternative sources for insect control, because some are selective, are biodegraded to non-toxic products, and have few effects on non-target organisms and the environment [3]. Studies of the essential oils and extracts derived from such plants as Clinopodium gracile [4], Saussurea lappa [5], Toddalia asiatica [6], Inula racemosa [7], Isodon japonicus var. glaucocalyx [8], and many other plants have demonstrated promising larvicidal activities against mosquito vectors. During our mass screening program for new agrochemicals from wild plants and Chinese medicinal herbs, we found that the essential oil of Youngia japonica (L.) DC. (family: Compositae) aerial parts showed larvicidal activity against the Asian tiger mosquito, A. albopictus.

Oriental or Asiatic hawksbeard (Y. japonica) is an annual common weed that grows along the roadsides, in gardens, and waste areas of Anhui, Chongqing, Fujian, Gansu, Guangdong, Guangxi, Guizhou, Hainan, Hebei, Henan, Hubei, Hunan, Jiangsu, Jiangxi, Shaanxi, Shandong, Sichuan, Taiwan, Xizang, Yunnan, and Zhejiang provinces as well as in Japan, Korea, Malaysia, the Philippines, and India [9]. The whole plant of this species is used in folk medicine for the treatment of inflammatory diseases, such as angina, leucorrhea, mastitis, conjunctivitis, and rheumatoid arthritis [10]. In previous studies, various flavonoids, sesquiterpenoids, triterpenoids, sesquiterpene glycosides, tannins, and steroids have been isolated and identified from this plant [11–16]. However, a literature survey has shown that there is no report on the larvicidal activity of the essential oil of Y. japonica aerial parts against mosquitoes. Thus, we decided to investigate the larvicidal activity of the essential oil against the Asian tiger mosquito and isolate any active constituents from the essential oil.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Plant material and essential oil extract

Fresh aerial parts of Y. japonica at flowering stage (20 kg) were harvested from Lishui City (27.54° N and 119.20° E, Zhejiang Province, China) in August 2013. The herb was identified by Dr. Q.R. Liu (College of Life Sciences, Beijing Normal University, Beijing 100875, China), and a voucher specimen (No. ENTCAU-Compositae-10239) was deposited at the Department of Entomology, China Agricultural University, Beijing, China. The sample was air-dried, ground to powder using a grinding mill (Retsch Mühle, Haan, Germany); subjected to hydrodistillation, using a modified Clevenger-type apparatus, for 6 h, and then extracted with n-hexane. The oil was dried over anhydrous Na2SO4 after evaporation of n-hexane using a rotary evaporator and kept in a refrigerator (4 °C) pending subsequent experiments.

2.2 Insect

Mosquito eggs of A. albopictus utilized in bioassays were obtained from a laboratory colony maintained in the Department of Vector Biology and Control, Institute for Infectious Disease Control and Prevention, Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention, Beijing, China. The original eggs of A. albopictus were collected from Nanjing, Jiangsu Province, China, in 1997. Adults were maintained in a cage (60 cm×30 cm×30 cm) at 28 °C–30 °C and 75%–85% relative humidity (RH). The females were fed with blood (Mus musculus, Beijing Laboratory Animal Research Center, Chaoyang District, Beijing, China) every alternate day, whereas the males were fed with 10% glucose solution soaked on cotton pad, which were hung in the middle of the cage. A beaker with strips of moistened filter paper was kept for oviposition. The eggs laid on paper strips were kept wet for 24 h and then dehydrated at room temperature. The dehydrated eggs were placed into a plastic tray containing tap water in our laboratory at 26 °C–28 °C and natural summer photoperiod for hatching and dog food served as food for the emerging larvae. Larvae were controlled daily until they reached the fourth instar (within 12 h), at which point they were utilized for bioassays.

2.3 Gas chromatography-mass spectrometry (GC-MS)

The essential oil of Y. japonica aerial parts was subjected to GC-MS analysis on an Agilent (Santa Clara, CA, USA) system consisting of a model 6890N gas chromatograph, a model 5973N mass selective detector (EIMS; electron energy, 70 eV), and an Agilent ChemStation data system. The GC column was an HP-5ms (Santa Clara, CA, USA) fused silica capillary with a 5% phenyl-methylpolysiloxane stationary phase, film thickness of 0.25 μm, a length of 30 m, and an internal diameter of 0.25 mm. The GC settings were as follows: the initial oven temperature was held at 60 °C for 1 min and ramped at 10 °C/min to 180 °C, held for 1 min, ramped at 20 °C/min to 280 °C, and then held for 15 min. The injector temperature was maintained at 270 °C. The sample (1 μL; 1:100, v/v, in acetone) was injected with a split ratio of 1:10. The carrier gas was helium at a flow rate of 1.0 mL/min. Spectra were scanned from m/z 20–550 at 2 scans/s. Most constituents were identified by gas chromatography by comparison of their retention indices with those found in the literature or with those of authentic compounds available in our laboratories. The retention indices were determined in relation to a homologous series of n-alkanes (C8–C24) under the same operating conditions. Further identification was made by comparison of their mass spectra with those stored in the NIST 08 and Wiley 275 libraries or with mass spectra in the literature [17]. Component relative percentages were calculated based on the normalization method without using correction factors.

2.4 Purification and characterization of two constituents

The crude essential oil of Y. japonica aerial parts (25 mL) was chromatographed on a silica gel (Merck 9385, 230–400 mesh, 1000 g; Merck Millipore, Darmstadt, Germany) column (85 mm i.d., 850 mm long) by gradient elution with a mixture of solvents [n-hexane:ethyl acetate, from 100:0, 100:1, 100:2, ···, to 0:100 (v/v)]. Fractions of 500 mL each were collected and concentrated at 40 °C; similar fractions according to their TLC profiles were combined to yield 13 fractions. The screening experiments were conducted using 500 ppm solutions (initially dissolved in acetone) of various fractions. The larvicidal activity bioassay was carried out as described below. Fractions 4–6 and 9–10 that possessed larvicidal activity, with similar TLC profiles, were pooled and further purified by preparative silica gel column chromatography (pre-coated GF254 plate; Qingdao Marine Chemical Plant, Qingdao, China) with petroleum ether/acetone (50:1, v/v) to obtain the pure compounds the structures of which were determined as menthol (1) (0.15 g), and α-asarone (2) (0.16 g). The structures of the compounds were elucidated based on nuclear magnetic resonance. Next, 1H and 13C NMR spectra were recorded on Bruker ACF300 [300 MHz (H)] and AMX500 [500 MHz (H)] instruments, using CDCl3 as the solvent with tetramethylsilane (TMS) as internal standard. Electron impact (EI) mass spectra were determined on a Micromass VG7035 mass spectrometer (VG Micromass, Manchester, UK) at 70 eV (probe).

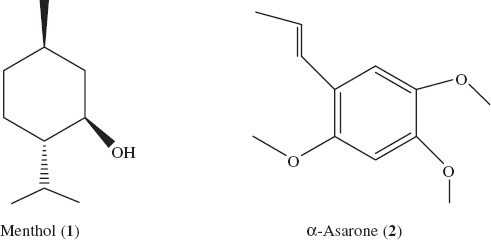

Menthol (1) (Figure 1): Crystalline solid, C10H20O. – 1H NMR (CDCl3, 500 MHz): δ=3.41 (1H, m, J=10.5, 4.3 Hz, H-6), 2.78 (2H, m, J=2.8 Hz, H-7), 1.96 (H, m, J=4.3, 2.1 Hz, H-5a), 1.66 (1H, m, H-3a), 1.62 (1H, m, H-2a), 1.42 (1H, m, H-4), 1.11 (1H, m, H-1), 0.94 (1H, m, H-2b), 0.93 (3H, s, H-9), 0.92 (1H, m, H-5b), 0.91 (3H, s, H-10), 0.83 (1H, m, H-3b), 0.81 (3H, s, H-8). – 13C NMR (CDCl3, 125 MHz): δ=72.5 (C-6), 50.2 (C-1), 45.1 (C-5), 34.6 (C-3), 31.7 (C-4), 25.9 (C-7), 23.3 (C-2), 22.2 (C-10), 21.0 (C-9), 16.2 (C-8). – EI-MS: m/z (%)=138 (27.6), 123 (31.3), 96 (29.0), 95 (70.2), 81 (76.7), 71 (100), 67 (25.7), 55 (40.1), 41 (40.9), 27 (15.3). The spectral data matched those of a previous report [18].

Mosquito larvicidal constituents isolated from the essential oil of Y. japonica

α-Asarone (2) (Figure 1). Crystalline solid, C12H16O3. – 1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3): δ=6.95 (1H, s, H-2), 6.66 (1H, dd, J=16, 1.6 Hz, H-7), 6.48 (1H, s, H-5), 6.09 (1H, dq, J=16, 7.2 Hz, H-8), 3.90 (3H, s, 10-OCH3), 3.84 (3H, s, 11-OCH3), 3.81 (3H, s, 12-OCH3), 1.89 (3H, dd, J=16, 7.2 Hz, H-10). – 13C NMR (125 MHz, CDCl3): δ=159.9 (C-4), 148.9 (C-6), 143.5 (C-1), 125.2 (C-7), 124.5 (C-8), 119.2 (C-3), 109.9 (C-2), 98.1 (C-5), 56.8 (C-10), 56.6 (C-12), 56.2 (C-11), 18.9 (C-9). – EI-MS: m/z (%)=208 (100), 165 (38), 137 (21), 105 (13), 91 (19), 69 (25), 41 (11). The spectral data matched those of a previous report [19].

2.5 Bioassay

Range-finding tests were conducted to determine the appropriate testing concentrations. The essential oil or constituents were first diluted to 10% (v/v), using acetone as a solvent, after which the final concentrations of 160, 80, 40, 20, and 10 μg/mL of the essential oil or constituents were tested. The larval mortality bioassays were carried out according to the test method of larval susceptibility as recommended by WHO [20]. A total of 20 larvae were placed in a glass beaker with 250 mL of aqueous solutions of test material at various concentrations, to which the emulsifier dimethylsulfoxide (DMSO; final content 0.05%, v/v) was added in the final test solution. Five replicates were run simultaneously per concentration. With each experiment, a set of controls made up of 0.05% DMSO and acetone and untreated sets of larvae in tap water were also run for comparison. Mortality was recorded after 24 h of exposure.

2.6 Data analysis

The observed mortality data were corrected for control mortality using Abbott’s formula. The mortality of larval mosquitoes in the control was <5%. Regression analysis was used to examine the linear relationship between concentrations and the mean value of larval mortalities [21]. When the goodness-of-fit test was significant (p<0.15) (Table 2), a heterogeneity factor was used in the calculation of confidence limits. The results from all replicates of the larvicidal bioassay were subjected to Probit analysis using PriProbit Program V1.6.3 to determine LC50 values and their 95% confidence intervals [21]. Significant differences in LC50 were based on non-overlap of the 95% confidence intervals.

3 Results and discussion

3.1 Essential oil analysis

The yield of the essential oil of Y. japonica aerial parts was 0.33% (v/w based on dry weight), and its density was determined to be 0.86 g/mL. A total of 31 compounds were identified from the essential oil of Y. japonica, accounting for 96.53% of the total oil. The principal constituents of Y. japonica essential oil were menthol (23.53%), α-asarone (21.54%), 1,8-cineole (5.36%), and caryophyllene (4.45%) (Table 1). Monoterpenoids represented 17 of the 31 constituents, corresponding to 44.50% of the oil. Sesquiterpenoids represented 12 of the 31 compounds, corresponding to 29.73% of the whole essential oil, and only two phenylpropanoids were identified, corresponding to 22.30% of the oil. The results were quite different from those reported previously [22], in which the essential oil of Y. japonica aerial parts harvested from Hunan province was found to mainly contain isophytol (29.85%), n-heneicosane (10.69%), dibutyl phthalate (8.81%), and farnesyl acetate (7.24%). The huge difference in the composition of the essential oils of Y. japonica aerial parts may be attributed to several factors, such as geographical variation, environmental conditions, and harvesting times as well as population variation.

Constituents identified from the essential oil of Y. japonica aerial parts.

| Peak no. | Compound | RIa | Composition, % |

|---|---|---|---|

| Monoterpenoids | 44.50 | ||

| 1 | α-Pinene | 931 | 0.32 |

| 2 | Camphene | 954 | 0.12 |

| 3 | β-Pinene | 981 | 0.67 |

| 4 | β-Myrcene | 991 | 0.17 |

| 5 | Limonene | 1029 | 0.31 |

| 6 | 1,8-Cineole | 1032 | 5.36 |

| 7 | γ-Terpinene | 1059 | 0.09 |

| 8 | Linalool | 1094 | 1.58 |

| 9 | Thujone | 1105 | 1.38 |

| 10 | Camphor | 1143 | 0.82 |

| 11 | Menthone | 1153 | 3.79 |

| 12 | Isomenthone | 1163 | 0.15 |

| 13 | Menthol | 1172 | 23.53 |

| 14 | 4-Terpineol | 1175 | 1.23 |

| 15 | α-Terpineol | 1189 | 3.15 |

| 16 | Neoisomenthol | 1194 | 0.69 |

| 17 | Menthyl acetate | 1297 | 1.14 |

| Sesquiterpenoids | 29.73 | ||

| 18 | Copaene | 1375 | 0.43 |

| 19 | Caryophyllene | 1420 | 4.45 |

| 20 | Ionone | 1422 | 2.22 |

| 21 | α-Caryophyllene | 1449 | 2.32 |

| 22 | δ-Selinene | 1492 | 0.89 |

| 23 | Dihydroactinolide | 1538 | 1.08 |

| 24 | Spathulenol | 1574 | 3.93 |

| 25 | Caryophyllene oxide | 1578 | 3.54 |

| 26 | Cedrol | 1607 | 1.67 |

| 27 | β-Eudesmol | 1648 | 3.45 |

| 28 | α-Cadinol | 1654 | 2.32 |

| 29 | α-Bisabolol | 1686 | 3.43 |

| Phenylpropanoids | 22.30 | ||

| 30 | Eugenol | 1356 | 0.76 |

| 31 | α-Asarone | 1645 | 21.54 |

| Total identified | 96.53 |

aRI, retention index as determined on an HP-5MS column using a homologous series of n-hydrocarbons.

3.2 Larvicidal activity

A positive correlation was observed between the essential oil/isolated compounds concentration and the larvicidal activity (p<0.15), with the rate of mortality being directly proportional to the concentration, indicating a dose-dependent effect on mortality (Table 2). The essential oil of Y. japonica aerial parts exhibited larvicidal activity against the fourth instar larvae of A. albopictus with an LC50 value of 32.45 μg/mL (Table 2). The two isolated constituents, menthol and α-asarone, had LC50 values of 77.97 μg/mL and 24.56 μg/mL, respectively (Table 2). The commercial insecticide, chlorpyrifos, showed larvicidal activity against the mosquitoes with an LC50 value of 1.86 μg/mL [6]. Thus, the essential oil of Y. japonica aerial parts was 17 times less toxic to A. albopictus larvae compared with chlorpyrifos. However, compared with other essential oils in the literature, which were obtained using the same bioassay, the essential oil of Y. japonica exhibited stronger larvicidal activity against A. albopictus larvae, e.g., essential oils of Allium macrostemon bulbs (LC50=72.86 μg/mL) [23], Eucalyptus urophylla (LC50=95.5 μg/mL) and E. camaldulensis (LC50=31.0 μg/mL) [24], Toddalia asiatica (LC50=69.09 μg/mL) [6], Clinopodium gracile (LC50=42.56 μg/mL) [4], Zanthoxylum avicennae leaves (LC50=48.79 μg/mL) [25], and Foeniculum vulgare (LC50=142.9 μg/mL) [26]. Among the two isolated compounds, α-asarone exhibited stronger larvicidal activity than the crude oil against A. albopictus larvae, while menthol was less toxic (based on non-overlap of the 95% confidence intervals). Thus, it is suggested that α-asarone is a major contributor to the larvicidal activity of the essential oil of Y. japonica. Moreover, compared with chlorpyrifos, α-asarone was 12 times less toxic to A. albopictus larvae (Table 2). In previous reports, α-asarone exhibited larvicidal activity against the third instar larvae of three mosquitoes, Culex pipiens pallens, A. aegyptiand Ochlerotatus togoi, with LC50 values of 22.38 ppm, 26.99 ppm and 26.38 ppm, respectively [27, 28]. Menthol also possessed larvicidal activity against the fourth instar larvae of A. aegypti with a 24-h LC50 value of 365.8 ppm [29, 30]. Moreover, some studies reported that α-asarone possesses insecticidal activity against several grain storage insects [19, 31, 32]. Menthol also possessed insecticidal activity against several insects and mites [33–36]. The abovementioned findings suggest that the essential oil of Y. japonica and the isolated constituents, especially α-asarone, show potential for development as possible natural larvicides for the control of mosquitoes.

Larvicidal activity of the essential oil of Youngia japonica and its isolated constituents against fourth-instar larvae of Aedes albopictus.

| Treatment | LC50, μg/mL (95% FLa) | LC95, μg/mL (95% FLa) | Slope±SD | Chi-square value (χ2) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Essential oil | 32.45 (29.38–35.96) | 55.76 (51.35–61.37) | 4.45±0.41 | 10.44 | 0.0054 |

| α-Asarone | 24.56 (22.41–26.94) | 51.28 (46.89–56.56) | 8.20±0.77 | 9.97 | 0.0068 |

| Menthol | 77.97 (70.21–85.21) | 167.86 (150.32–183.45) | 9.30±0.85 | 12.32 | 0.0021 |

| Chlorpyrifosb | 1.86 (1.71–2.05) | 6.65 (6.21–7.48) | 0.87±0.01 | 3.13 | – |

aFiducial limits, bFrom Liu et al. [19].

Youngia japonica is quite safe for humans, because it has been used in traditional medicine for the treatment of inflammatory diseases, such as angina, leucorrhea, mastitis, conjunctivitis, and rheumatoid arthritis [10]. However, a literature survey revealed that there is no experimental data on the toxicity of the essential oil of Y. japonica to humans. Thus, to develop a practical application for the essential oil and its constituents as novel insecticides, further research into the safety of the essential oil/compounds to humans is needed. Additional studies on the development of formulations are also necessary to improve efficacy and stability as well as to reduce costs. Moreover, field evaluation and further investigations on the effects of the essential oil and its constituents on non-target organisms are necessary.

Acknowledgments

This work was funded by the Hi-Tech Research and Development of China (2011AA10A202). We also thank Dr. Q.R. Liu from College of Life Sciences, Beijing Normal University, Beijing, China, for the identification of the investigated plant.

References

1. Liu ZL, Liu QZ, Du SS, Deng ZW. Mosquito larvicidal activity of alkaloids and limonoids derived from Evodia rutaecarpa unripe fruits against Aedes albopictus (Diptera: Culicidae). Parasitol Res 2012;111:991–6.10.1007/s00436-012-2923-9Search in Google Scholar PubMed

2. Regnault-Roger C, Vincent C, Arnason JT. Essential oils in insect control: low-risk products in a high-stakes world. Annu Rev Entomol 2012;57:405–24.10.1146/annurev-ento-120710-100554Search in Google Scholar PubMed

3. Isman MB. Botanical insecticides, deterrents, and repellents in modern agriculture and an increasingly regulated world. Annu Rev Entomol 2006;51:45–66.10.1146/annurev.ento.51.110104.151146Search in Google Scholar PubMed

4. Chen XB, Liu XC, Zhou L, Liu ZL. Essential oil composition and larvicidal activity of Clinopodium gracile (Benth.) Matsum (Labiatae) aerial parts against the Aedes albopictus mosquito. Trop J Pharm Res 2013;12:799–804.Search in Google Scholar

5. Liu ZL, He Q, Chu SS, Wang CF, Du SS, Deng ZW. Essential oil composition and larvicidal activity of Saussurea lappa roots against the mosquito Aedes albopictus (Diptera: Culicidae). Parasitol Res 2012;110:2125–30.10.1007/s00436-011-2738-0Search in Google Scholar PubMed

6. Liu XC, Dong HW, Zhou L, Du SS, Liu ZL. Essential oil composition and larvicidal activity of Toddalia asiatica roots against the mosquito Aedes albopictus (Diptera: Culicidae). Parasitol Res 2012;112:1197–203.10.1007/s00436-012-3251-9Search in Google Scholar PubMed

7. He Q, Liu XC, Sun RQ, Deng ZW, Du SS, Liu ZL. Mosquito larvicidal constituents from the ethanol extract of Inula racemosa Hook.f. Roots against Aedes albopictus. J Chem 2014, doi:10.1155/2014/738796.10.1155/2014/738796Search in Google Scholar

8. Liu XC, Liu QY, Zhou L, Liu ZL. Larvicidal activity of Isodon japonicus var. glaucocalyx (Maxim.) H.W.Li essential oil to Aedes aegypti L. and its chemical composition. Trop J Pharm Res 2014;13:1471–6.10.4314/tjpr.v13i9.13Search in Google Scholar

9. Ling Y, Shih C. Flora Republicae Popularis Sinicae, Vol. 80(1). Beijing, China: Science Press, 1997:155–7.Search in Google Scholar

10. Jiangsu New Medicinal College Encyclopedia of Chinese Materia Medica. Shanghai, China: Shanghai Scientific and Technologic Press, 1977:2066.Search in Google Scholar

11. Shiojima K, Suzuki H, Takano A, Kurihara M, Kodera N, Hirano A, et al. Composite constituents: triterpenoids from some cichorioideous plants. Nat Med 1997;51:125–30.Search in Google Scholar

12. Jang DS, Ha TJ, Choi SU, Nam SH, Park KH, Yang MS. Isolation of isoamberboin and isolipidiol from whole plants of Youngia japonica (L.) DC. Saengyak Hakhoechi 2000;31:306–9.Search in Google Scholar

13. Lee WB, Kwon HC, Yi JH, Choi SU, Lee KR. A new cytotoxic triterpene hydroperoxide from the aerial part of Youngia japonica. Yakhak Hoechi 2002;46:1–5.Search in Google Scholar

14. Chen WL, Liu QF, Wang J, Zou J, Meng DH, Zuo JP, et al. New guaiane, megastigmane and eudesmane-type sesquiterpenoids and anti-inflammatory constituents from Youngia japonica. Planta Med 2006;72:143–50.10.1055/s-2005-916182Search in Google Scholar PubMed

15. Ooi LS, Wang H, He ZD, Ooi VE. Antiviral activities of purified compounds from Youngia japonica (L.) DC (Asteraceae, Compositae). J Ethnopharmacol 2006;106:187–91.10.1016/j.jep.2005.12.028Search in Google Scholar PubMed

16. Yae E, Yahara S, El-Aasr M, Ikeda T, Yoshimitsu H, Masuoka C, et al. Studies on the constituents of whole plants of Youngia japonica. Chem Pharm Bull 2009;57:719–23.10.1248/cpb.57.719Search in Google Scholar PubMed

17. Adams RP. Identification of essential oil components by gas chromatography/mass spectrometry, 4th ed. Carol Stream, IL, USA: Allured Publishing Corporation, 2007.Search in Google Scholar

18. Hartner J, Reinscheid UM. Conformational analysis of menthol diastereomers by NMR and DFT computation. J Mol Struct 2008;872:145–9.10.1016/j.molstruc.2007.02.029Search in Google Scholar

19. Liu XC, Zhou L, Liu ZL, Du SS. Identification of insecticidal constituents of essential oil of Acorus calamus rhizomes against Liposcelis bostrychophila Badonnel. Molecules 2013;18:5684–95.10.3390/molecules18055684Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

20. World Health Organization. Report of the WHO informal consultation, on the evaluation and testing of insecticides. CTD/WHOPES/IC/96.1, Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization, 1996:32–6.Search in Google Scholar

21. Sakuma M. Probit analysis of preference data. Appl Entomol Zool 1998;33:339–47.10.1303/aez.33.339Search in Google Scholar

22. Liu XQ, Zou XP, Gao JM, Li LL. GC-MS analysis of volatile constituents of three compositae plants growing in Hunan. Northwest Pharm J 2010;25:179–81 (in Chinese with English abstract).Search in Google Scholar

23. Liu XC, Liu QY, Zhou L, Liu ZL. Evaluation of larvicidal activity of the essential oil of Allium macrostemon Bunge and its selected major constituent compounds against Aedes albopictus (Diptera: Culicidae). Parasites Vectors 2014;7:184.10.1186/1756-3305-7-184Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

24. Cheng SS, Huang CG, Chen YJ, Yu JJ, Chen WJ, Chang ST. Chemical compositions and larvicidal activities of leaf essential oils from two eucalyptus species. Bioresource Technol 2009;100:452–6.10.1016/j.biortech.2008.02.038Search in Google Scholar PubMed

25. Liu XC, Liu QY, Zhou L, Liu QR, Liu ZL. Chemical composition of Zanthoxylum avicennae essential oil and its larvicidal activity on Aedes albopictus Skuse. Trop J Pharm Res 2014;13:399–404.10.4314/tjpr.v13i3.13Search in Google Scholar

26. Conti B, Canale A, Bertoli A, Gozzini F, Pistelli L. Essential oil composition and larvicidal activity of six Mediterranean aromatic plants against the mosquito Aedes albopictus (Diptera: Culicidae). Parasitol Res 2010;107:1455–61.10.1007/s00436-010-2018-4Search in Google Scholar PubMed

27. Perumalsamy H, Chang KS, Park C, Ahn YJ. Larvicidal activity of Asarum heterotropoides root constituents against insecticide-susceptible and -resistant Culex pipiens pallens and Aedes aegypti and Ochlerotatus togoi. J Agric Food Chem 2010;58:10001–6.10.1021/jf102193kSearch in Google Scholar PubMed

28. Perumalsamy H, Kim JR, Kim SI, Kwon HW, Ahn YJ. Enhanced toxicity of binary mixtures of larvicidal constituents from Asarum heterotropoides root to Culex pipiens pallens (Diptera: Culicidae). J Med Entomol 2012;49:107–11.10.1603/ME11092Search in Google Scholar PubMed

29. Pandey SK, Tandon S, Ahmad A, Singh AK, Tripathia AK. Structure–activity relationships of monoterpenes and acetyl derivatives against Aedes aegypti (Diptera: Culicidae) larvae. Pest Manag Sci 2013;69:1235–8.10.1002/ps.3488Search in Google Scholar PubMed

30. Samarasekera R, Weerasinghe IS, Hemalal KD. Insecticidal activity of menthol derivatives against mosquitoes. Pest Manag Sci 2008;64:290–5.10.1002/ps.1516Search in Google Scholar

31. Momin RA, Nair MG. Pest-managing efficacy of trans-asarone isolated from Daucus carota L. seeds. J Agric Food Chem 2002;50:4475–8.10.1021/jf020209rSearch in Google Scholar

32. Park C, Kim SI, Ahn YJ. Insecticidal activity of asarones identified in Acorus gramineus rhizome against three coleopteran stored-product insects. J Stored Prod Res 2003;39:333–42.10.1016/S0022-474X(02)00027-9Search in Google Scholar

33. Delaplane KS. Controlling tracheal mites (Acari: Tarsonemidae) in colonies of honey bees (Hymenoptera: Apidae) with vegetable oil and menthol. J Econ Entomol 1992;85:2118–24.10.1093/jee/85.6.2118Search in Google Scholar

34. Aggarwal KK, Tripathi AK, Ahmad A, Prajapati V, Verma N, Kumar S. Toxicity of L-menthol and its derivatives against four storage insects. Insect Sci Appl 2001;21:229–35.10.1017/S1742758400007621Search in Google Scholar

35. Badawy ME, El-Arami SA, Abdelgaleil SA. Acaricidal and quantitative structure activity relationship of monoterpenes against the two-spotted spider mite, Tetranychus urticae. Exp Appl Acarol 2010;52:261–74.10.1007/s10493-010-9363-ySearch in Google Scholar PubMed

36. Han J, Kim SI, Choi BY, Lee SG, Ahn YJ. Fumigant toxicity of lemon eucalyptus oil constituents to acaricide-susceptible and acaricide-resistant Tetranychus urticae. Pest Manag Sci 2011;67:1583–8.10.1002/ps.2216Search in Google Scholar PubMed

©2015 by De Gruyter

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Larvicidal activity of the essential oil of Youngia japonica aerial parts and its constituents against Aedes albopictus

- Antiviral and antitumor activities of the lectin extracted from Aspidistra elatior

- Susceptibility of Microsporum canis arthrospores to a mixture of chemically defined essential oils: a perspective for environmental decontamination

- Central analgesic activity of the aqueous and ethanolic extracts of the leaves of Albizia lebbeck: role of the GABAergic and serotonergic pathways

- Three further triterpenoid saponins from Gleditsia caspica fruits and protective effect of the total saponin fraction on cyclophosphamide-induced genotoxicity in mice

- Acylated flavonol diglucosides from Ammania auriculata

- Synthesis and antimicrobial properties of N-substituted derivatives of (E)-2′,3″-thiazachalcones

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Larvicidal activity of the essential oil of Youngia japonica aerial parts and its constituents against Aedes albopictus

- Antiviral and antitumor activities of the lectin extracted from Aspidistra elatior

- Susceptibility of Microsporum canis arthrospores to a mixture of chemically defined essential oils: a perspective for environmental decontamination

- Central analgesic activity of the aqueous and ethanolic extracts of the leaves of Albizia lebbeck: role of the GABAergic and serotonergic pathways

- Three further triterpenoid saponins from Gleditsia caspica fruits and protective effect of the total saponin fraction on cyclophosphamide-induced genotoxicity in mice

- Acylated flavonol diglucosides from Ammania auriculata

- Synthesis and antimicrobial properties of N-substituted derivatives of (E)-2′,3″-thiazachalcones