Abstract

A new quaternary germanide has been synthesized and structurally characterized. BaLi2Cd2Ge2 adopts the rhombohedral CaCu4P2 structure type (Pearson code hR7; space group

1 Introduction

In a recent paper, we described new results from our exploratory work in the Ba-Li-In-Ge system [1]. As noted therein, two quaternary Ba-Li-In-Ge phases had previously been identified: BaLi1−x

In

x

Ge2 (BaLi0.9Mg0.1Si2 type, space group Pnma, No. 62; Pearson code oP16) [2] and BaLi

x

In2−x

Ge2 (ThCr2Si2 type, space group I4/mmm, No. 139; Pearson code oI10) [3], both featuring small degrees of Li/In admixing. Our synthetic approach employed molten In as a flux, allowing us to grow crystals of yet another quaternary phase, BaLi2+x

In2−x

Ge2 (0 ≤ x ≤ 0.66) or BaLi2In2Ge2, for short (CaCu4P2 type, space group

Having recognized this flexibility of the structure, and keeping in mind the fact that BaMg2Li2Ge2 is known [4] (N.B. despite the resemblance between the chemical compositions and structures of BaMg2Li2Ge2 and BaLi2In2Ge2, the two phases are formally isotypic, but with subtly different bonding characteristic, vide infra), we attempted to extend this chemistry to other systems with divalent metals. Drawing on prior successes employing molten Cd as a flux for the syntheses of new germanides [5, 6], we embarked on exploring the AE-Li-Cd-Ge systems (AE = alkaline earth metals Ca, Sr, Ba, and nominally divalent Eu, Yb). As a result, the discovery of the new rhombohedral BaLi2Cd2Ge2 phase emerged, which is the first structurally characterized compound between the respective elements. The intricacies of the chemical bonding of BaLi2Mg2Ge2 and BaLi2Cd2Ge2, which are isoelectronic but structurally slightly different, and BaLi2In2Ge2 and BaLi2Cd2Ge2, which are not isoelectronic, yet very much structurally akin, are the main subject of discussion in this paper.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Synthesis

The starting materials were purchased from Alfa Aesar, all with stated purity 99.9 wt% or better. The metals were stored in an argon gas filled glovebox and used as received; the surface of the Li rod was cleaned with a scalpel blade prior to cutting and using it.

Single crystals of BaLi2Cd2Ge2 were grown from excess Cd, intended as a flux. An elemental mixture with the ratio Ba:Li:Cd:Ge = 1:10:20:2 was loaded into an alumina crucible, which was subsequently placed in a fused silica tube. The crucible was covered with a plug, made from quartz wool to be used as a filter during the removal of the molten Cd via centrifugation. Before placing the tube in the furnace, it was connected to a vacuum line and flame-sealed. Heat-treatment proceeded in the following manner: i) temperature was ramped up to 473 K at a rate 20 K h−1, allowing the Li to melt, before further raising the temperature to 973 K with a ramp rate of 50 K h−1. ii) After annealing at this temperature for 10 h, a cooling to 773 K was initiated with a rate of 5 K h−1. iii) At this point of the synthesis, the sealed tube was taken out from the furnace, flipped, and the molten metallic flux was separated from the grown crystals by using a centrifuge.

The procedure mirrors that used for growing BaLi2In2Ge2 crystals [1], where it was established that the success of the experiment is incumbent upon using a large excess of Li. We do not believe that molten Li acts as a flux at the given reaction conditions, rather, the 5× over stoichiometric amount used in the reaction is deemed necessary to compensate for the loss of Li due to evaporation and side reactions with the reactor walls. Upon completion of the heat-treatment, the tube was brought back into the glovebox and was break-opened. The visually inhomogeneous products consisted of the known phases BaCd2Ge2 and BaCd11, which were easily identified by powder X-ray diffraction as the main products. Closer inspection under an optical microscope revealed the presence of some small black plates with metallic luster dispersed within the larger BaCd2Ge2 and BaCd11 crystallites. Single-crystal X-ray diffraction confirmed that they were the new BaLi2Cd2Ge2 phase.

Following the structure elucidation of BaLi2Cd2Ge2, reactions aimed at the production of AELi2Cd2Ge2 (AE = Ca, Sr, Eu) were set up with the same nominal compositions as the ones described in the preceding paragraph, but they were unsuccessful. An attempt to grow crystals from the close-to-the-stoichometry Pb flux reaction were unsuccessful. Similarly, reactions intended to produce AELi2Zn2Ge2 (AE = Ca, Sr, Ba, Eu) also did not yield the desired materials. In all of the above cases, stable Zn- and Cd-bearing binaries, such as Ba2Zn or BaZn13 were the most recurring side products.

2.2 Powder X-ray diffraction (PXRD) and single-crystal X-ray diffraction (SCXRD)

Samples for PXRD were prepared by grinding the as-synthesized materials with an agate mortar and pestle. The X-ray powder diffraction patterns were then recorded using a Rigaku Miniflex powder diffractometer utilizing Ni-filtered CuKα radiation (λ = 1.5418 Å) and could be only used for main-phase identification.

Single crystals for SCXRD were selected under an optical microscope, and cut to suitable dimensions for subsequent data collection (to mitigate potential issues arising from X-ray absorption, the sizes of the selected crystals were smaller than 100 μm in any direction). The crystals were then mounted on low background MiTeGen plastic loops using Paratone-N oil. A Bruker APEX II CCD-based diffractometer, equipped with a monochromated MoKα radiation source (λ = 0.71073 Å) was used. Intensity data were collected and integrated using the Bruker-supplied software, and absorption correction was applied using Sadabs [7]. The structure was solved and refined to convergence by full-matrix least-square methods on F 2 by using Shelxt and Shelxl, respectively [8, 9]. All sites, including Li, were refined with anisotropic displacement parameters. The final difference Fourier map was featureless.

One specific aspect of the refinements concerning the site occupation factors (SOF) requires a special mention. All SOFs were checked by freeing an individual SOF, while other variables were kept fixed. No statistically significant deviations were observed for the SOF of the heavy elements; the Li position indicated a freely-refined SOF of ca. 125%. This is indicative of potential disordering at the Li site, likely due to a Li/Ge admixture (in analogy with Li/Ge disorder in many RE-Li-Ge ternary phases (RE = rare earth metal) [10, 11]), or Li/Cd co-occupation (in analogy with the Li/Cd disorder in Ba4Li2Cd2 Pn 6 and Li/In disorder in the isotypic BaLi2+x In2−x Ge2 (0 ≤ x ≤ 0.66) quaternary phases [1, 12]). Since the detected “over-occupation” of the Li atom barely had statistical significance (deviations were within ca. 4σ), and since no additional experimental work has been conducted so far to confirm/refute the possibilities of Li/Cd or Li/Ge mixing, the final refinements presented in this paper reflect a devoid of a disordered chemical composition BaLi2Cd2Ge2 (Table 1). Further details of the structural work are discussed later on.

Selected crystallographic data and structure refinement parameters for BaLi2Cd2Ge2.

| Formula | BaLi2Cd2Ge2 |

| Formula weight/g mol−1 | 521.20 |

| Radiation; λ/Å | Mo Kα; 0.71073 |

| Temperature/K | 200(2) |

| Crystal system | Rhombohedral |

| Space group |

|

| Z | 3 |

| a/Å | 4.5929(6) |

| c/Å | 26.119(5) |

| V/Å3 | 477.16(13) |

| ρ calcd /g cm−3 | 5.44 |

| µ(MoKα)/cm−1 | 218.6 |

| Reflections: parameters | 206:12 |

| R 1 (I > 2 σ(I))a | 0.0144 |

| R 1 (all data)a | 0.0306 |

| wR 2 (I > 2 σ(I))a | 0.0150 |

| wR 2 (all data)a | 0.0307 |

| Largest peak; deepest hole/e − Å−3 | 1.02; −0.80b |

-

a R 1 = ∑||F o | − |F c ||/∑|F o |; wR 2 = [∑[w(F o 2 − F c 2)2]/∑[w(F o 2)2]]1/2, where w = 1/[σ2 F o 2 + (0.014P)2 + 2.032P], and P = (F o 2 + 2F c 2)/3); b The largest peak and the deepest hole are 0.7 Å away from Cd and 0.9 Å away from Li, respectively.

CCDC 2101506 contains the supplementary crystallographic data for this paper. These data can be obtained free of charge from The Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre via www.ccdc.cam.ac.uk/data_request/cif.

2.3 Electronic structure calculations

First-principle calculations were performed within the density functional theory framework (DFT) with the aid of the TB-LMTO-ASA code [13]. For all calculations, the von Barth-Hedin version of the local density approximation functional (LDA) was employed [14]. The Brillouin zone was sampled by a 24 × 24 × 24 k-point grid after checking for convergence of the total energy. Chemical bonding was inspected utilizing crystal orbital Hamilton population analysis (COHP) and electron localization function (ELF) [15], [16], [17].

3 Results and discussion

3.1 Crystal structure

BaLi2Cd2Ge2 crystallizes in the space group

Atomic coordinates and equivalent isotropic displacement parameters (Å2) for BaLi2Cd2Ge2.

| Atom | Wyckoff symbol | Site symmetry | x | y | z | U eq a |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ba | 3a |

|

0 | 0 | 0 | 0.011(1) |

| Ge | 6c | 3m | 0 | 0 | 0.2486(1) | 0.011(1) |

| Cd | 6c | 3m | 0 | 0 | 0.4715(1) | 0.014(1) |

| Li | 6c | 3m | 0 | 0 | 0.1442(3) | 0.005(2) |

-

a U eq is defined as one third of the trace of the orthogonalized U ij tensor.

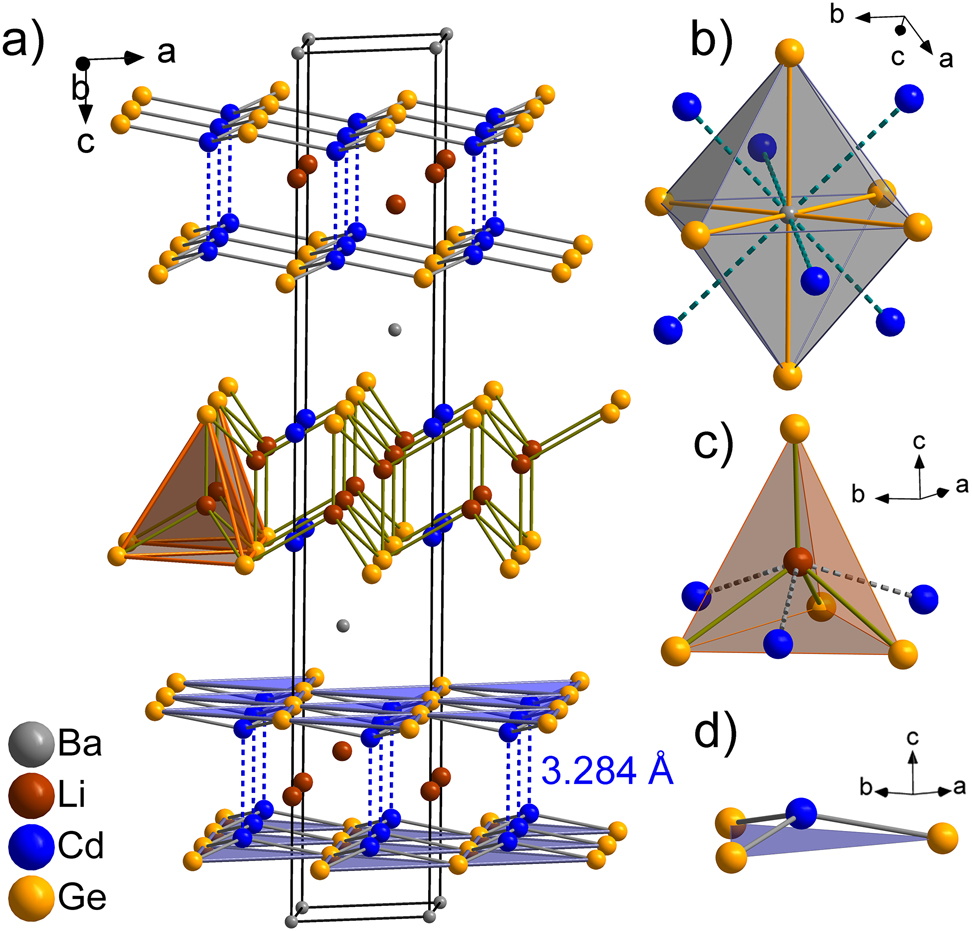

BaLi2Cd2Ge2 can be viewed as a Zintl phase, where the anionic substructure is made up of alternating [Cd2Ge2] double-layers. The large Ba2+ cations are located between the polyanionic 2D fragments, and the small Li+ cations are found within them (Figure 1). The single [CdGe] layers are puckered and consist of 3-coordinate Cd and Ge atoms. Two such layers come close together with the shortest distance being just under 3.3 Å (between neighboring Cd atoms). Tetrahedral voids in the packing of the Ge atoms created by this arrangement are filled by Li+ cations, and octahedral holes between two [Cd2Ge2] slabs are filled by Ba2+. Alternatively, the structure can be described as layers consisting of edge-sharing [LiGe4] tetrahedra (Figure 1(a)), identical to those in the CaAl2Si2 structure type, with Ba and Cd atoms located between and within the 2D fragments, respectively.

(a) Representation of the structure of rhombohedral BaLi2Cd2Ge2. Local coordination environment of Ba (b), Li (c), and Cd (d).

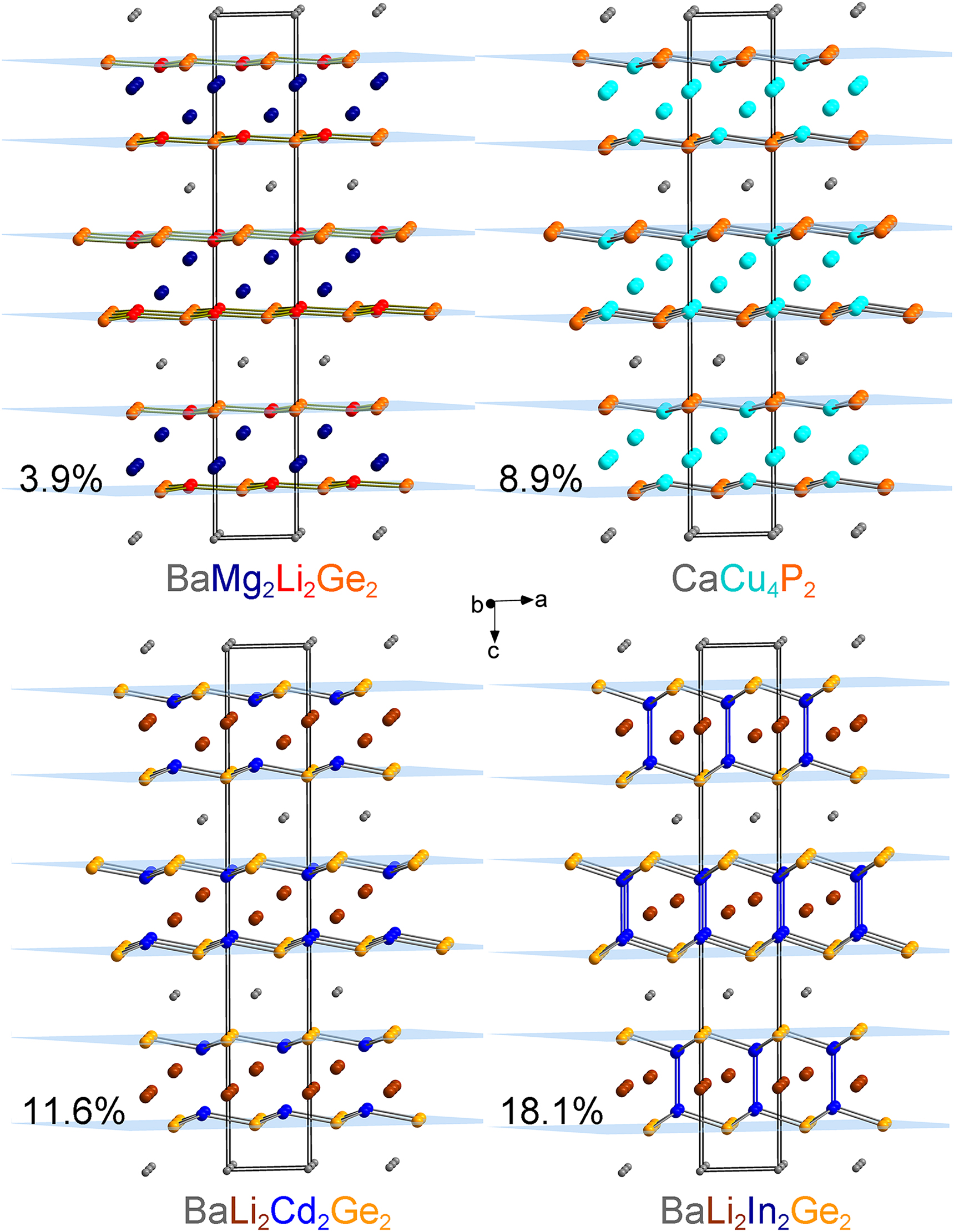

A closer look at the [Cd2Ge2] double-layers is necessary for a better understanding of the nature of the bonding and the electronic structure (Section 3.3). These 2D fragments are extending parallel to the ab plane, and a single [CdGe] sheet can be considered as being a puckered variant of the ZrBeSi-type structure, also known as LiGaGe-type structure [19]. While each Cd atom is trigonally coordinated by three Ge atoms, it slightly protrudes by ca. 0.5 Å (or ca. 11.6% of the total interlayer distance) from the imaginary plane formed by the Ge atoms (Figure 2).

Structural relationships between BaMg2Li2Ge2, CaCu4P2, BaLi2Cd2Ge2, and BaLi2In2Ge2.

The protruding value was calculated as a ratio of the atom-to-plane distance to the interplane distance.

The shortest distance between layers is represented by the Cd–Cd contacts (3.28 Å). This separation is 15% longer than the sum of the covalent radius assigned to Cd (1.44 Å) [20], suggestive of an absence of homoatomic Cd–Cd bonding. Electronic structure calculations, vide infra, support this notion. Interestingly, the crystal structure of the β-CaZnGe phase also features puckered [ZnGe] layers without interlayer bonding [21].

An interesting comparison can be made with the [CuP] layers in the archetype CaCu4P2 structure (Figure 2) [18]. The Cu atoms “protrude” 0.33 Å out of the plane of the P atoms (ca. 8.9% of the plane-to-plane total distance) with no evidence of Cu–Cu interlayer bonding. Thus, CaCu4P2 can be rationalized as a charge-balanced Zintl phase, i.e., (Ca2+)(Cu+)4(P3− )2. Similarly, partitioning of the valence electrons in BaLi2Cd2Ge2 can be described by the formulation (Ba2+)(Li+)2(Cd2+)2(Ge4−)2. The same charge-balance scheme applies to BaMg2Li2 Tt 2 (Tt = Si, Ge), where the assignment of charges is as follows: (Ba2+)(Mg2+)2(Li+)2(Tt 4−)2. One will notice that the order of Li and Cd and Li and Mg in the respective formulae is interchanged to reflect the different bonding patterns [4]. Divalent Mg and monovalent Li in BaMg2Li2 Tt 2 occupy the Li and Cd sites in BaLi2Cd2Ge2, respectively. In this view, the [LiGe] layers are almost flat (Li deviates from the plane of Ge atoms by only 0.15 Å, or ca. 3.9%) and all Mg atoms are located between two layers, retaining their tetrahedral coordination by the Tt atoms (Figure 2).

The discussed bonding patterns are slightly different for the AELi2In2Ge2 (AE = Sr, Eu, Ba) family of compounds, where the presence of homoatomic In–In bonding (ca. 3.03 Å) was detected (Figure 2) [1]. The latter serves as an interconnection between two layers, uniting the slab, which eventually has to be considered as built up of staggered ethane-like [Ge3In–InGe3] fragments linked via Ge atoms. Indium atoms are 0.86 Å away from the plane of the Ge atoms (ca. 18.1%). This structural feature is observed in some pnictides, such as the structurally related hexagonal SrIn2As2 phase (puckering 22.7%) and the rhombohedral CaGa2As2 phase (22.5%) [22, 23]. All given examples boast homoatomic In–In or Ga–Ga bonding, which causes large deviations from planarity, and requires assigning the triel elements not in the 3+ state, but rather 2+ state. Consequently, the electron counts reflect this consideration: Both (Ba2+)(Li+)2(In2+)2(Ge4−)2 and (Sr2+)(In2+)2(As3−)2 satisfy the charge balance criteria and can be rationalized based on the Zintl concept.

The structural relationships described above are associated with the strivings of the constituent elements to form certain coordination environments. A trigonal-planar coordination is known for Li, for the coinage metals (Cu, Ag, Au), Zn, and, in very rare cases, for Cd [24]. At the same time this type of coordination is less common for Mg, Ga, and In, which are usually tetrahedrally or octahedrally (in case of Mg [25]) coordinated. This may explain the observed difference in bonding and the specific site preferences for all phases mentioned above within the discussed structure type. Homoatomic Cd–Cd bonds in BaLi2Cd2Ge2, Cu–Cu bonds in CaCu4P2, and Li–Li bonds in BaMg2Li2 Tt 2 are unfavorable from the point of view of charge balance, despite that a tetrahedral coordination is preferred for these elements. With the trigonal planar coordination for the Cd atom being far from optimal, one might consider Zn → Cd substitution with the expectation that the Zn atoms may favor the trigonal planar coordination more so than Cd. With this idea in mind, we pursued the compounds ALi2Zn2Ge2 (A = Ca, Sr, Ba); they were considered as possible isostructural analogs of BaLi2Cd2Ge2, where the [ZnGe] layers will be very close to being “flat”. However, as was stated in the experimental section, such synthetic attempts have been, so far, unsuccessful.

The role of Li in the formation of compounds with this structure should also be discussed; after all the Li atoms can occupy multiple sites in this arrangement. A binary Li5Ge2 compound is known beyond the discussed cases of BaLi2 M 2Ge2 (M = Cd, In) and BaMg2Li2 Tt 2. In the Li5Ge2 structure, the Li atoms can be seen as forming [LiGe] layers and filling the space within and between them. While the crystal structure of this binary phase is not unequivocally established to date, computational work suggests its existence with the same rhombohedral structure discussed in this paper [26]. One should notice that in the structure of the binary phase, the Ge atoms are expected to be dimerized, forming strong Ge–Ge bonds. With the Ge atoms located at the atomic site that corresponds to that of the Cd/In atoms in BaLi2 M 2Ge2, the remaining three sites occupied by Ba, Li, and Ge are taken by Li. Therefore, the electron count in Li5Ge2 leads to the imbalanced formulation (Li+)5(Ge3−)2(h +), where h + denotes an electron hole. We have attempted to experimentally validate these speculations, but preliminary structural analysis has shown that the length of the Ge–Ge bonds can vary depending on the synthetic conditions, which is indicative of the existence of a homogeneity range in Li5−x Ge2+x . This also signals the unique role of Li in the formation of the novel phases within the discussed structure type.

A brief comparison of selected crystallographic metrics for BaLi2Cd2Ge2 and BaLi2In2Ge2 is presented next. Similar values of the covalent radii for In (1.42 Å) and Cd (1.44 Å) account for the almost identical unit cell parameters for both phases. While the overall unit cell volumes are indeed very similar (ca. 475 vs ca. 477 Å3 for In-bearing and Cd-bearing phases, respectively), the unit cell parameters a and c are noticeably different: a = 4.52, c = 26.8 Å for BaLi2In2Ge2, and a = 4.59, c = 26.12 Å for BaLi2Cd2Ge2. In → Cd substitution causes a shortening of the c axis and can be associated with the different coordination observed for In and Cd in both compounds. The larger Cd atom within the [CdGe] layer (parallel to the ab plane) apparently is the reason for the slight expansion in the latter directions. Cd–Ge distances in BaLi2Cd2Ge2 (Table 3) are close to the sum of the covalent radii for Cd (1.44 Å) and Ge (1.22 Å) [20].

Selected interatomic distances for BaLi2Cd2Ge2.

| Atom pair | Distance (Å) |

|---|---|

| Ba–Ge ×6 | 3.4540(6) |

| Ba–Cd ×6 | 3.7927(6) |

| Li–Ge | 2.726(9) |

| Li–Ge ×3 | 3.074(4) |

| Li–Cd ×3 | 2.854(3) |

| Cd–Ge ×3 | 2.6982(4) |

The local coordination environments for the Ba, Li and Cd atoms are visualized in Figure 1, panels b), c) and d). The distorted octahedral coordination of the Ba atoms in the BaLi2Cd2Ge2 compound consists of six Ge neighbors with distances within the typical range for Ba germanides [1], [2], [3], [4]. The coordination sphere can be extended by including six Cd atoms, with Ba–Cd contacts approaching 3.8 Å (Table 3). Although too long to be considered as typical bonds, the Ba–Cd interactions play some role in the overall electronic stability, as supported by our calculations, vide infra. The Li atoms are surrounded by four Ge atoms in a distorted tetrahedral coordination environment. The shortest Li–Ge bond is oriented along the c axis (Table 3). The Li atoms also have some close Cd neighbors, but only three out of the six Li–Cd contacts are within bonding distances (Table 3), whereas the other three are much longer (ca. 3.46 Å) and similar in magnitude to the Li–In contacts in BaLi2+x In2−x Ge2 (x ≈ 0.66) [1]. Not surprisingly, In–In interatomic distances in the latter compound are comparable to the Cd–Cd contacts observed in the title phase.

3.2 Electronic structure

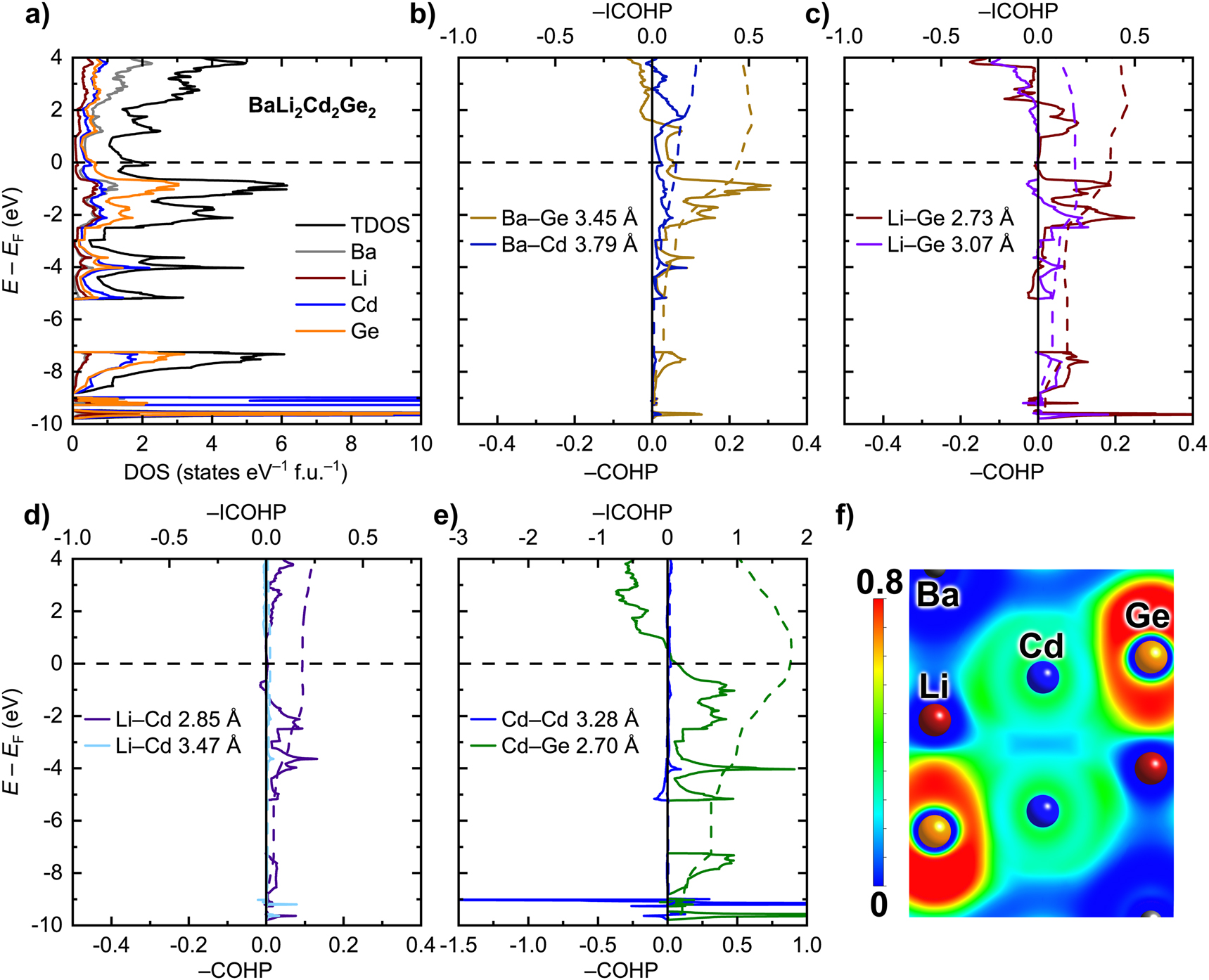

The electronic density of states (DOS) for the BaLi2Cd2Ge2 phase is shown in Figure 3(a). The deep lying states below the Fermi level (E F ) are mainly composed of the occupied, localized Cd(4d) and Ge(4s) states. The latter signal the presence of lone pairs of electrons on the Ge atoms. Close to the Fermi level, significant mixing of electronic states is observed, similar to the case of the structurally related BaLi2In2Ge2 and BaMg2Li2Ge2 [1, 4].

(a) Total and projected electronic densities of states (DOS) for BaLi2Cd2Ge2. (b–e) Crystal orbital Hamilton population curves (COHP, solid curves) and their integrals (ICOHP, dashed curves) for selected interactions. (f) Section of the Electron Localization Function (ELF) though a Cd⋯Cd–Ge plane.

Quite unexpectedly, the Fermi level in BaLi2Cd2Ge2 crosses a distinct peak in the DOS. As discussed above, the electron partitioning suggests that the studied compound can be classified as a Zintl phase, according to the scheme: (Ba2+)(Li+)2(Cd2+)2(Ge4−)2 (N.B. One should be mindful that here we greatly overstate the ionicity of the chemical bonding, neglecting the possible covalency of Li–Ge and especially Cd–Ge interactions). Therefore, the presence of an electronic band gap or a dip in the electronic density of states at the Fermi level would indeed be anticipated. In fact, the two related phases mentioned above, BaLi2In2Ge2 and BaMg2Li2Ge2, display pronounced pseudogaps at E F [1]. The apparent deviation of BaLi2Cd2Ge2 from the expected behavior poses questions as to the applicability of the Zintl concept in this case and whether or not there may exist disorder, akin to that in BaLi2+x In2−x Ge2.

To better understand the electronic properties of BaLi2Cd2Ge2, we analyzed the chemical bonding in this compound. Crystal orbital Hamilton population curves (COHP) for selected interatomic contacts are given in Figure 3(b)–(e). A notable feature is the presence of partially filled bonding states observed for the Ba–Ge and Ba–Cd contacts at the Fermi level (Figure 3(b)). These states appear to be responsible for the emergence of the peak in the DOS. In comparison, the COHP curves for the Li–Ge, Li–Cd, and Cd–Ge contacts reveal pseudogaps at E F (Figure 3(c)–(e)). The Li–Ge and Li–Cd interactions are bonding, but are somewhat underoptimized due to the presence of unoccupied bonding states above E F or antibonding states just below (Figure 3(c) and (d)). The strongest interaction, Cd–Ge, is essentially optimized – only a small number of bonding states are still available above the Fermi level (Figure 3(e)). As expected from the electron counting arguments presented earlier, the absence of Cd–Cd bonds in the structure is confirmed by the calculations – this notion is reflected in the nonbonding character seen for the pair Cd–Cd (Figure 3(e)). An inspection of the Electron Localization Function (ELF), which does not show any maxima between the Cd atoms from adjacent layers (Figure 3(f)), reaffirms this reasoning.

The provided analysis suggests that the maximum in the electronic density of states at E F observed for the BaLi2Cd2Ge2 phase mainly stems from underoptimized Ba–Ge and Ba–Cd interactions. Although the corresponding Ba–Ge and Ba–In interactions in the structurally related BaLi2In2Ge2 phase were found to be underoptimized as well [1], the respective unoccupied bonding states were found shifted away from the Fermi level, resulting in a pseudogap in the electronic spectrum. Since both BaLi2Cd2Ge2 and BaLi2In2Ge2 are formally electron-balanced according to the formula (Ba2+)(Li+)2(M 2+)2(Ge4−)2 (M = Cd or In; recall that the charge 2+ is assigned to In due to the presence of In–In bonds), the difference in the electronic structures between the two compounds is rather unexpected.

The valence electron count in the other quaternary germanide with an analogous structure, BaMg2Li2Ge2, also appears to be amenable to a full breakdown if one were to use the classic inorganic concepts. In this situation, the ionic picture (Ba2+)(Mg2+)2(Li+)2(Ge4−)2 may be more appropriate compared to BaLi2Cd2Ge2, considering the electronegativities of the constituting elements, especially Mg (χ P = 1.2) and Cd (χ P = 1.7). An important structural difference between the two compounds needs to be remembered though, the sites of Mg and Li are interchanged relative to those of Cd and Li. If the resultant [LiGe] sheets are regarded as polyanionic units with covalent bonding, with one valence electron provided by Li and four by Ge, the [LiGe]3− layers in BaMg2Li2Ge2 allow for all atoms to attain closed-shell configurations. Unlike BaLi2Cd2Ge2 and BaLi2In2Ge2, the structure of the Mg phase features almost planar [LiGe] sheets, vide supra, which allows describing the atoms in the layers as sp 2-hybridized, in contrast to the sp 3-hybridized species in the Cd and In representatives. The sp 2 hybridization can be compatible with a higher bond order than a single bond for the Li–Ge contacts. In a rather naïve picture, one may consider two out of three Li–Ge bonds in the local coordination as single bonds and one as a double bond. Then, every atom would need four valence electrons to satisfy the octet rule (or 16 electrons per [Li2Ge2] unit), which is fulfilled for the [Li2Ge2]6− layers in BaMg2Li2Ge2. Owing to the electron conjugation provided by the sp2 hybridization, all three bonding contacts around Li (or, equivalently, Ge) can be of the same length and an intermediate bond order in this representation. We notice that a similar scenario could be realized for the layers in BaLi2Cd2Ge2 if they were flat.

To check this hypothesis, we ran first-principle calculations on a hypothetical BaLi2Cd2Ge2 model where Cd and Ge were shifted (equally, in opposite directions from their actual positions) to lie in the same plane, while the coordinates of other atoms were unchanged. In line with the rationale provided above, the electronic density of states for this model exhibits a pseudogap at the Fermi level (Figure 4(a)). Analysis of the chemical bonds shows that all principal bonding interactions are almost optimized at E F in this model (Figure 4(b)). A question to ask here is: If the bonding is optimized for the model with flat [CdGe] sheets, why does the experimentally observed structure show displacement of the Cd atoms away from the Ge plane? It is important to note that the optimized bonding does not guarantee a lower total energy. Location of the Cd atoms in the Ge plane would likely lead to high chemical pressure due to the shortened Cd–Ge contacts. The high spatial requirements of the Cd atoms (in comparison with, e.g., the smaller Li atoms in BaMg2Li2Ge2) result in rippling of the [CdGe] layers. By corrugating the layers, the system appears to become electron-deficient, evidenced by the presence of underoccupied bonding states at E F . If the geometric factor is indeed at play in this case, studying other representatives with smaller M atoms in the [MGe] layers, e.g., Zn or Mn, will be instructive. The Zn phase could not be made so far, as mentioned earlier, and more dedicated efforts need to be done; the Mn phase, if it exists, may also be interesting from a perspective of magnetism.

![Figure 4:

(a, b) Total and projected electronic densities of states (DOS) for a BaLi2Cd2Ge2 model with flat [CdGe] layers and the corresponding Crystal Orbital Hamilton population curves (COHP) for selected averaged interactions, respectively. (c, d) Same electronic properties for a BaLiCd3Ge2 model.

Solid and dashed colored curves denote COHP curves and their integrals, respectively.](/document/doi/10.1515/znb-2021-0114/asset/graphic/j_znb-2021-0114_fig_004.jpg)

(a, b) Total and projected electronic densities of states (DOS) for a BaLi2Cd2Ge2 model with flat [CdGe] layers and the corresponding Crystal Orbital Hamilton population curves (COHP) for selected averaged interactions, respectively. (c, d) Same electronic properties for a BaLiCd3Ge2 model.

Solid and dashed colored curves denote COHP curves and their integrals, respectively.

From the above, it is evident that the unexpected high DOS at the Fermi level in BaLi2Cd2Ge2 is related to the 3-fold coordination of the Cd atoms by Ge. This bonding environment makes the application of the Zintl concept somewhat ambiguous, as was previously noted in our presentation, and has also been discussed for some other phases with trigonally coordinated metal species [27]. However the perceived electron deficiency in BaLi2Cd2Ge2 also indicates that the electronic structure is likely to be stabilized, subject to a suitable electron doping. A possible way to inject electrons in the system is via the substitution of Li by Cd, in a manner similar to the Li → In exchange in BaLi2−x In2+x Ge2 [1], provided that Cd will exhibit cationic character upon such substitution. There is a hint from the single-crystal work that this might be the case, since the SOF of the Li site was freely refined as 25% “overoccupied”, but the exact reasons for this experimental observations are still unclear (more systematic studies will be necessary to discern two likely scenarios, BaLi2−x Cd2+x Ge2 or BaLi2−x Cd2Ge2+x ). Our first-principle calculations on yet another hypothetical model, BaLiCd3Ge2, with half of the Li atoms replaced by Cd in an ordered manner, confirm this scenario (Figure 3(c)). The Ba–Ge and Ba–Cd bonding states that were crossed by the Fermi level in the original BaLi2Cd2Ge2 structure are occupied in the BaLiCd3Ge2 model (Figure 3(d)). The Li–Ge and Li–Cd interactions are almost unaffected by electron doping due to the small number of the respective hybridized electronic states in the vicinity of the Fermi level. Due to the extension of the bonding states for the Cd–Ge contacts above E F in BaLi2Cd2Ge2, electron doping has a weakly stabilizing effect on the covalent Cd–Ge interactions. Therefore, the main effect of electron doping is optimization of Ba–Ge and Ba–Cd interactions in the structure. It is worth noting that the somewhat too small anisotropic displacement parameters of Li in the refined BaLi2Cd2Ge2 structure may point toward small substitution of Li by Cd, as such substitution would be favorable based on our calculations.

Dedicated to: Professor Richard Dronskowski of the RWTH Aachen on the occasion of his 60th birthday.

Funding source: National Science Foundation (NSF)

Award Identifier / Grant number: DMR-2004579

-

Author contributions: All the authors have accepted responsibility for the entire content of this submitted manuscript and approved submission.

-

Research funding: This work received financial support from the National Science Foundation (NSF) through an award number DMR-2004579.

-

Conflict of interest statement: The authors declare no conflicts of interest regarding this article.

References

1. Ovchinnikov, A., Bobev, S. Inorg. Chem. 2019, 58, 7895–7904; https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.inorgchem.9b00588.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

2. You, T.-S., Bobev, S. J. Solid State Chem. 2010, 183, 2895–2902; https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jssc.2010.09.041.Search in Google Scholar

3. Nam, G., Jang, E., You, T.-S. Bull. Kor. Chem. Soc. 2013, 34, 3847–3850; https://doi.org/10.5012/bkcs.2013.34.12.3847.Search in Google Scholar

4. Zürcher, F., Wengert, S., Nesper, R. Z. Kristallogr. N. Cryst. Struct. 2001, 216, 503–504; https://doi.org/10.1524/ncrs.2001.216.14.537.Search in Google Scholar

5. Suen, N.-T., Huang, L., Meyers, J. J., Bobev, S. Inorg. Chem. 2018, 57, 833–842; https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.inorgchem.7b02781.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

6. Guo, S.-P., Meyers, J. J., Tobash, P. H., Bobev, S. J. Solid State Chem. 2012, 192, 16–22; https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jssc.2012.03.045.Search in Google Scholar

7. Sheldrick, G. M. Sadabs (version 2014/2). Program for Empirical Absorption Correction of Area Detector Data; Bruker AXS Inc.: Madison, Wisconsin (USA), 2014.Search in Google Scholar

8. Sheldrick, G. M. Acta Crystallogr. 2015, A71, 3–8; https://doi.org/10.1107/S2053273314026370.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

9. Sheldrick, G. M. Acta Crystallogr. 2015, C71, 3–8; https://doi.org/10.1107/S2053229614024218.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

10. Fornasini, M. L., Palenzona, A., Pani, M. Intermetallics 2012, 31, 114–119; https://doi.org/10.1016/j.intermet.2012.06.011.Search in Google Scholar

11. Guo, S.-P., You, T.-S., Jung, Y.-H., Bobev, S. Inorg. Chem. 2012, 51, 6821–6829; https://doi.org/10.1021/ic300566x.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

12. Makongo, J. P. A., You, T.-S., He, H., Suen, N.-T., Bobev, S. Eur. J. Inorg. Chem. 2014, 2014, 5113–5124; https://doi.org/10.1002/ejic.201402434.Search in Google Scholar

13. Jepsen, O., Andersen, O. K. TB-LMTO-ASA (version 47); Max-Planck-Institut für Festkörperforschung: Stuttgart (Germany), 2000. http://www2.fkf.mpg.de/andersen/LMTODOC/LMTODOC.html (accessed Aug, 2021).Search in Google Scholar

14. von Barth, U., Hedin, L. J. Phys. C Solid State Phys. 1972, 5, 1629–1642; https://doi.org/10.1088/0022-3719/5/13/012.Search in Google Scholar

15. Steinberg, S., Dronskowski, R. Crystals 2018, 8, 225; https://doi.org/10.3390/cryst8050225.Search in Google Scholar

16. Dronskowski, R., Blöchl, P. E. J. Phys. Chem. 1993, 97, 8617–8624; https://doi.org/10.1021/j100135a014.Search in Google Scholar

17. Savin, A., Nesper, R., Wengert, S., Fässler, T. F. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. Engl. 1997, 36, 1808–1832; https://doi.org/10.1002/anie.199718081.Search in Google Scholar

18. Mewis, A. Z. Naturforsch. 1980, 35b, 942–945; https://doi.org/10.1515/znb-1980-0802.Search in Google Scholar

19. Matar, S. F., Pöttgen, R. Z. Naturforsch. 2019, 74b, 307–318; https://doi.org/10.1515/znb-2019-0010.Search in Google Scholar

20. Cordero, B., Gómez, V., Platero-Prats, A. E., Revés, M., Echeverría, J., Cremades, E., Barragán, F., Alvarez, S. Dalton Trans. 2008, 2832–2838; https://doi.org/10.1039/b801115j.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

21. Zhu, M., Xia, S.-Q. J. Alloys Compd. 2019, 774, 502–508; https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jallcom.2018.10.033.Search in Google Scholar

22. Ogunbunmi, M. O., Baranets, S., Childs, A. B., Bobev, S. Dalton Trans. 2021, 50, 9173–9184; https://doi.org/10.1039/D1DT01521D.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

23. He, H., Stearrett, R., Nowak, E. R., Bobev, S. Eur. J. Inorg. Chem. 2011, 2011, 4025–4036; https://doi.org/10.1002/ejic.201100065.Search in Google Scholar

24. Bünzli, J. -C. G., Pecharsky, V. K., Eds. Handbook on the Physics and Chemistry of Rare Earths; North-Holland, Elsevier: Amsterdam, Vol. 60, 2021. (in press).Search in Google Scholar

25. Wang, J., Mark, J., Woo, K. E., Voyles, J., Kovnir, K. Chem. Mater. 2019, 31, 8286–8300; https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.chemmater.9b03740.Search in Google Scholar

26. Tipton, W. W., Matulis, C. A., Hennig, R. G. Comput. Mater. Sci. 2014, 93, 133–136; https://doi.org/10.1016/j.commatsci.2014.06.014.Search in Google Scholar

27. Wang, Y., Qin, Q., Sang, R., Xu, L. Dalton Trans. 2015, 44, 18316–18319; https://doi.org/10.1039/C5DT02600H.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

© 2021 Walter de Gruyter GmbH, Berlin/Boston

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- In this issue

- Laudatio/Preface

- Celebrating the 60th birthday of Richard Dronskowski

- Review

- Orbital-selective electronic excitation in phase-change memory materials: a brief review

- Research Articles

- Solving the puzzle of the dielectric nature of tantalum oxynitride perovskites

- d- and s-orbital populations in the d block: unbound atoms in physical vacuum versus chemical elements in condensed matter. A Dronskowski-population analysis

- Single-crystal structures of A 2SiF6 (A = Tl, Rb, Cs), a better structure model for Tl3[SiF6]F, and its novel tetragonal polymorph

- Na2La4(NH2)14·NH3, a lanthanum-rich intermediate in the ammonothermal synthesis of LaN and the effect of ammonia loss on the crystal structure

- Linarite from Cap Garonne

- Salts of octabismuth(2+) polycations crystallized from Lewis-acidic ionic liquids

- High-temperature diffraction experiments and phase diagram of ZrO2 and ZrSiO4

- Thermal conversion of the hydrous aluminosilicate LiAlSiO3(OH)2 into γ-eucryptite

- Crystal structure of mechanochemically prepared Ag2FeGeS4

- Effect of nanostructured Al2O3 on poly(ethylene oxide)-based solid polymer electrolytes

- Sr7N2Sn3: a layered antiperovskite-type nitride stannide containing zigzag chains of Sn4 polyanions

- Exploring the frontier between polar intermetallics and Zintl phases for the examples of the prolific ALnTnTe3-type alkali metal (A) lanthanide (Ln) late transition metal (Tn) tellurides

- Zwitterion coordination to configurationally flexible d 10 cations: synthesis and characterization of tetrakis(betaine) complexes of divalent Zn, Cd, and Hg

- An approach towards the synthesis of lithium and beryllium diphenylphosphinites

- Synthesis, crystal and electronic structure of CaNi2Al8

- Crystal and electronic structure of the new ternary phosphide Ho5Pd19P12

- Synthesis, structure, and magnetic properties of the quaternary oxysulfides Ln 5V3O7S6 (Ln = La, Ce)

- Synthesis, crystal and electronic structure of BaLi2Cd2Ge2

- Structural variations of trinitrato(terpyridine)lanthanoid complexes

- Preparation of CoGe2-type NiSn2 at 10 GPa

- Controlled exposure of CuO thin films through corrosion-protecting, ALD-deposited TiO2 overlayers

- Experimental and computational investigations of TiIrB: a new ternary boride with Ti1+x Rh2−x+y Ir3−y B3-type structure

- Synthesis and crystal structure of the lanthanum cyanurate complex La[H2N3C3O3]3 · 8.5 H2O

- Cd additive effect on self-flux growth of Cs-intercalated NbS2 superconducting single crystals

- 14N, 13C, and 119Sn solid-state NMR characterization of tin(II) carbodiimide Sn(NCN)

- Superexchange interactions in AgMF4 (M = Co, Ni, Cu) polymorphs

- Copper(I) iodide-based organic–inorganic hybrid compounds as phosphor materials

- On iodido bismuthates, bismuth complexes and polyiodides with bismuth in the system BiI3/18-crown-6/I2

- Synthesis, crystal structure and selected properties of K2[Ni(dien)2]{[Ni(dien)]2Ta6O19}·11 H2O

- First low-spin carbodiimide, Fe2(NCN)3, predicted from first-principles investigations

- A novel ternary bismuthide, NaMgBi: crystal and electronic structure and electrical properties

- Magnetic properties of 1D spin systems with compositional disorder of three-spin structural units

- Amine-based synthesis of Fe3C nanomaterials: mechanism and impact of synthetic conditions

- Enhanced phosphorescence of Pd(II) and Pt(II) complexes adsorbed onto Laponite for optical sensing of triplet molecular dioxygen in water

- Theoretical investigations of hydrogen absorption in the A15 intermetallics Ti3Sb and Ti3Ir

- Assembly of cobalt-p-sulfonatothiacalix[4]arene frameworks with phosphate, phosphite and phenylphosphonate ligands

- Chiral bis(pyrazolyl)methane copper(I) complexes and their application in nitrene transfer reactions

- UoC-6: a first MOF based on a perfluorinated trimesate ligand

- PbCN2 – an elucidation of its modifications and morphologies

- Flux synthesis, crystal structure and electronic properties of the layered rare earth metal boride silicide Er3Si5–x B. An example of a boron/silicon-ordered structure derived from the AlB2 structure type

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- In this issue

- Laudatio/Preface

- Celebrating the 60th birthday of Richard Dronskowski

- Review

- Orbital-selective electronic excitation in phase-change memory materials: a brief review

- Research Articles

- Solving the puzzle of the dielectric nature of tantalum oxynitride perovskites

- d- and s-orbital populations in the d block: unbound atoms in physical vacuum versus chemical elements in condensed matter. A Dronskowski-population analysis

- Single-crystal structures of A 2SiF6 (A = Tl, Rb, Cs), a better structure model for Tl3[SiF6]F, and its novel tetragonal polymorph

- Na2La4(NH2)14·NH3, a lanthanum-rich intermediate in the ammonothermal synthesis of LaN and the effect of ammonia loss on the crystal structure

- Linarite from Cap Garonne

- Salts of octabismuth(2+) polycations crystallized from Lewis-acidic ionic liquids

- High-temperature diffraction experiments and phase diagram of ZrO2 and ZrSiO4

- Thermal conversion of the hydrous aluminosilicate LiAlSiO3(OH)2 into γ-eucryptite

- Crystal structure of mechanochemically prepared Ag2FeGeS4

- Effect of nanostructured Al2O3 on poly(ethylene oxide)-based solid polymer electrolytes

- Sr7N2Sn3: a layered antiperovskite-type nitride stannide containing zigzag chains of Sn4 polyanions

- Exploring the frontier between polar intermetallics and Zintl phases for the examples of the prolific ALnTnTe3-type alkali metal (A) lanthanide (Ln) late transition metal (Tn) tellurides

- Zwitterion coordination to configurationally flexible d 10 cations: synthesis and characterization of tetrakis(betaine) complexes of divalent Zn, Cd, and Hg

- An approach towards the synthesis of lithium and beryllium diphenylphosphinites

- Synthesis, crystal and electronic structure of CaNi2Al8

- Crystal and electronic structure of the new ternary phosphide Ho5Pd19P12

- Synthesis, structure, and magnetic properties of the quaternary oxysulfides Ln 5V3O7S6 (Ln = La, Ce)

- Synthesis, crystal and electronic structure of BaLi2Cd2Ge2

- Structural variations of trinitrato(terpyridine)lanthanoid complexes

- Preparation of CoGe2-type NiSn2 at 10 GPa

- Controlled exposure of CuO thin films through corrosion-protecting, ALD-deposited TiO2 overlayers

- Experimental and computational investigations of TiIrB: a new ternary boride with Ti1+x Rh2−x+y Ir3−y B3-type structure

- Synthesis and crystal structure of the lanthanum cyanurate complex La[H2N3C3O3]3 · 8.5 H2O

- Cd additive effect on self-flux growth of Cs-intercalated NbS2 superconducting single crystals

- 14N, 13C, and 119Sn solid-state NMR characterization of tin(II) carbodiimide Sn(NCN)

- Superexchange interactions in AgMF4 (M = Co, Ni, Cu) polymorphs

- Copper(I) iodide-based organic–inorganic hybrid compounds as phosphor materials

- On iodido bismuthates, bismuth complexes and polyiodides with bismuth in the system BiI3/18-crown-6/I2

- Synthesis, crystal structure and selected properties of K2[Ni(dien)2]{[Ni(dien)]2Ta6O19}·11 H2O

- First low-spin carbodiimide, Fe2(NCN)3, predicted from first-principles investigations

- A novel ternary bismuthide, NaMgBi: crystal and electronic structure and electrical properties

- Magnetic properties of 1D spin systems with compositional disorder of three-spin structural units

- Amine-based synthesis of Fe3C nanomaterials: mechanism and impact of synthetic conditions

- Enhanced phosphorescence of Pd(II) and Pt(II) complexes adsorbed onto Laponite for optical sensing of triplet molecular dioxygen in water

- Theoretical investigations of hydrogen absorption in the A15 intermetallics Ti3Sb and Ti3Ir

- Assembly of cobalt-p-sulfonatothiacalix[4]arene frameworks with phosphate, phosphite and phenylphosphonate ligands

- Chiral bis(pyrazolyl)methane copper(I) complexes and their application in nitrene transfer reactions

- UoC-6: a first MOF based on a perfluorinated trimesate ligand

- PbCN2 – an elucidation of its modifications and morphologies

- Flux synthesis, crystal structure and electronic properties of the layered rare earth metal boride silicide Er3Si5–x B. An example of a boron/silicon-ordered structure derived from the AlB2 structure type