Abstract

Linarite, PbCuSO4(OH)2, crystallizes as secondary mineral in form of clusters of crystals in Mine du Pradet at Cap Garonne in France. A tiny single crystal was isolated and its structure was refined from synchrotron diffraction data (λ = 0.049592 nm): P121/m1, a = 467.75(2), b = 563.48(4), c = 967.64(5) pm, β = 102.647(5)°, wR = 0.0544, 819 F 2 values and 56 variables. The proton positions were also refined. The Cu2+ cations are located within Cu(OH)2 ribbons and exhibit pronounced Jahn-Teller distortion (d(Cu–O): 2 × 191.9, 2 × 197.3 and 2 × 252.8 pm). The Cu(OH)2 ribbons are condensed with the sulfate tetrahedra and the lead cations. The latter are coordinated to eight oxygen atoms in a slightly anisotropic manner. Calculations of the electron localization function (ELF) of PbO (litharge), PbSO4 (anglesite) and PbCuSO4(OH)2 (linarite) show pronounced lone-pair character for PbO but rather isotropic ELF values around the lead cations in PbSO4 and PbCuSO4(OH)2.

1 Introduction

Linarite, PbCuSO4(OH)2 [1], [2] is a typical secondary mineral which occurs in oxidized areas of copper and lead-containing zones. Its occurrence was first reported in 1822 and was named after the locality Linares in Spain. Meanwhile several hundred locations have been reported. Actually, linarite would be a reasonable mineral for copper and lead production; however, its abundance is too low for an economic use. Linarite usually occurs in the form of tufted aggregates of small crystals (on the µm scale). Larger single-crystal specimens (even cm-size) have been collected in the Mammoth Mine and the Grand Reef Mine in Graham County, Arizona. Such crystals allow for property studies. A single crystal approximately 1 cm in size from Grand Reef Mine was used for a neutron diffraction study [3].

Diffraction data was recorded for linarite samples from different locations [4], [5], [6], [7], [8], [9], [10], [11], [12], [13], [14], including powder and single-crystal work with laboratory and synchrotron X-ray data as well as neutron scattering experiments. The hydrogen bonding in linarite was studied on the basis of neutron time-of-flight data [14]. Besides the basic crystallographic characterization, linarite has been investigated with respect to its optical properties [15], [16], [17], [18], [19]. Optical absorption spectroscopic studies confirmed the presence of divalent copper in D 4h site symmetry [16]. Since 2006 PbCuSO4(OH)2 has attracted considerable interest from solid state physicists and chemists [20], [21], [22], [23], [24], [25], [26], [27], [28], [29], [30] with respect to its copper-oxygen substructure which behaves as a quasi-one-dimensional S = 1/2 frustrated-spin chain. The magnetic and transport properties and the multiferroic behaviour [31], [32], [33] of linarite have been studied in depth.

The present contribution focuses on linarite from Cap Garonne [34]. Its existence was first mentioned by Mumme et al. [35] during their study of schulenbergite. Herein we report on synchtrotron single-crystal X-ray data and a study of the electronic structure of linarite with respect to the lead lone-pair of electrons.

2 Experimental

2.1 Sample selection

The linarite sample originates from Cap Garonne (Département du Var, Région Provence-Alpes-Côte d’Azur), Mine du Pradet [34]. It was localized in the northern part of the mine (Mine Nord) in the so-called rift mirror gallery (Galerie du Miroir de Faille) within a rock face. The vertical cut (Figure 1) revealed (from bottom to top) a zinc-containing zone (adamite) followed by a copper-containing one (olivenite, azurite, malachite), a copper/zinc zone (rosasite), a lead zone (galena, linarite, dundasite, caledonite, cerussite) and finally a lead-copper zone (bayldonite, gartrellite). The linarite crystals grew in form of tufted aggregates (Figure 2) on a quartz/covellite/galena matrix. The habit of our linarite microcrystals agrees with the many entries in the RRUFF data base [2].

Location of linarite in the north mine, rift mirror gallery (Mine Nord, Galerie du Miroir de Faille) of Cap Garonne (Photo: E. Magnan). The source of discovery (red arrow) has a width of ca. 60 × 70 cm.

Agglomerated linarite crystals of the north mine (Mine Nord, Galerie du Miroir de Faille) of Cap Garonne; FoV 2.1 mm (Photo: P. Clolus).

2.2 X-ray diffraction

Part of the linarite surface was scraped off with a spatula, powdered and filled into a 0.1 mm Lindemann capillary. A powder pattern was recorded at room temperature on a STOE Stadi P diffractometer with CuKα 1 radiation in the 2θ range 5–80°. Eight ranges of 2 h each were added up. The refined lattice parameters of a = 467.78(6), b = 563.73(4), c = 967.64(9) pm, β = 102.66(1)° and V = 0.2490 nm3 compare well with the single-crystal data (Table 1).

Crystal data and structure refinement parameters for PbCu(OH)2SO4, space group P121/m1, Z = 2 and 400.81 g mol−1. Standard deviations are given in parentheses.

| Temperature, K | 295(2) |

| Lattice parameters (single-crystal data) | |

| a, pm | 467.75(2) |

| b, pm | 563.48(4) |

| c, pm | 967.64(5) |

| β, deg | 102.647(5) |

| Unit cell volume V, nm3 | 0.2489 |

| Calculated density, g cm−3 | 5.35 |

| Crystal size, µm3 | 40 × 40 × 40 |

| Beamline | DESY PETRA III P24 |

| Diffractometer type | Kappa diffractometer |

| Wavelength λ, Å | 0.49592 (synchrotron) |

| Transmission (min/max) | 0.620/0.746 |

| Detector distance, mm | 111.08 |

| Exposure time, s | 2.5 |

| ω range/increment, deg. | 360/0.5 |

| Absorption coefficient, mm−1 | 15.1 |

| Absorption correction | Multi-scan |

| F(000), e | 354 |

| θ range, deg | 1.51–20.74 |

| Range in hkl | ±6; −7 → +6, ±13 |

| Total no. reflections | 3069 |

| Independent reflections/R int | 819/0.0446 |

| Reflections with I > 2 σ(I)/R σ | 774/0.0398 |

| Data/parameters | 819/56 |

| Goodness-of-fit on F 2 for all data | 1.05 |

| R/wR for I > 2 σ(I) | 0.0222/0.0539 |

| R/wR for all data | 0.0230/0.0544 |

| Largest diff. peak/hole, e Å−3 | 1.94/−1.04 |

Small fragments of the lath-shaped overgrown tufts were selected after careful mechanical fragmentation. The tiny crystal splinters were glued to glass fibres using varnish and their quality was checked using a Buerger precession camera with white Mo radiation and an image plate technique. Intensity data of a suitable crystal was collected at beamline P24 (EH1) of the Deutsches Elektronen-Synchrotron (room temperature, Huber Kappa-diffractometer, Pilatus 1M CdTe detector, λ = 0.49592 Å). Data integration and absorption correction were performed with the CrysAlis [36] and Sadabs [37] routines.

2.3 Structure refinement

The data set showed a primitive monoclinic lattice and the systematic extinctions were in agreement with space group P21/m. The standardized atomic parameters (entry 1,223,862 in the Pearson data base [38]) of the time-of-flight neutron diffraction study [14] were taken as starting values and the structure was refined on F 2 values with the Shelxl software package [39] with anisotropic atomic displacement parameters for the non-hydrogen atoms. The latter were refined with isotropic displacement parameters which were set to values of 1.2 U eq of the neighbouring oxygen atoms [40]. The final difference Fourier syntheses revealed no significant residual electron density. The refined atomic positions, displacement parameters, and interatomic distances are given in Tables 2 and 3.

Wyckoff sites, atomic coordinates, equivalent isotropic and anisotropic displacement parameters in pm2 for PbCu(OH)2SO4 measured at 295 K. The anisotropic displacement factor exponent takes the form: −2π 2[(ha*)2 U 11 + … + 2hka*b*U 12]. Standard deviations are given in parentheses.

| Atom | Wyckoff | x | y | z | U 11 | U 22 | U 33 | U 12 | U 13 | U 23 | U eq/U iso |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pb | 2e | 0.32863(4) | 1/4 | 0.84188(2) | 208(1) | 261(2) | 150(1) | 0 | −11(1) | 0 | 214(1) |

| Cu | 2c | 0 | 0 | 1/2 | 117(3) | 107(3) | 160(3) | 5(2) | 21(2) | −11(2) | 129(1) |

| S | 2e | 0.1160(3) | 1/4 | 0.16792(13) | 121(5) | 158(6) | 136(6) | 0 | 33(5) | 0 | 138(2) |

| O1 | 2e | 0.9344(9) | 1/4 | 0.0243(4) | 200(20) | 251(19) | 154(18) | 0 | 1(16) | 0 | 207(8) |

| O2 | 2e | 0.4291(10) | 1/4 | 0.1640(5) | 130(20) | 400(20) | 270(20) | 0 | 67(17) | 0 | 266(9) |

| O3 | 4f | 0.0572(7) | 0.0374(4) | 0.2471(3) | 287(16) | 169(12) | 155(13) | −25(11) | 37(11) | 15(10) | 206(6) |

| O4 | 2e | 0.7146(8) | 1/4 | 0.4658(4) | 107(16) | 127(16) | 157(17) | 0 | 21(14) | 0 | 131(7) |

| O5 | 2e | 0.2678(8) | 1/4 | 0.5950(4) | 114(16) | 152(16) | 148(17) | 0 | 35(13) | 0 | 137(7) |

| H1 | 2e | 0.628(14) | 1/4 | 0.373(2) | 160a | ||||||

| H2 | 2e | 0.428(10) | 1/4 | 0.558(7) | 160a | ||||||

-

aFixed parameter.

Interatomic distances (pm) for PbCu(OH)2SO4. All distances of the first coordination spheres are listed. Standard deviations are given in parentheses.

| Pb: | 1 | O5 | 234.3(4) |

| 2 | O3 | 243.7(3) | |

| 1 | O1 | 281.8(3) | |

| 1 | O1 | 299.2(3) | |

| 2 | O2 | 304.2(3) | |

| 1 | O2 | 304.9(3) | |

| Cu: | 2 | O4 | 191.9(3) |

| 2 | O5 | 197.3(2) | |

| 2 | O3 | 252.8(3) | |

| S: | 1 | O1 | 146.2(4) |

| 1 | O2 | 147.3(5) | |

| 2 | O3 | 148.0(3) | |

| O4: | 1 | H1 | 90(2) |

| O5: | 1 | H2 | 90(6) |

CCDC 2071334 contains the supplementary crystallographic data for this paper. These data can be obtained free of charge from The Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre via www.ccdc.cam.ac.uk/data_request/cif.

2.4 EDX data

A clump of linarite crystals from the sample shown in Figure 2 was broken off the matrix and studied by energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDX) using a Zeiss EVO® MA10 scanning electron microscope in variable pressure mode (60 Pa) with PbF2, Cu, FeS2 and SiO2 as standards. The EDX analyses on several lath-shaped crystals showed a Pb:Cu:S:O ratio of 1.0(1):0.9(1):1.1(1):6.2(2), close to the ideal composition. No impurity elements were detected.

2.5 Electronic structure calculations

All density-functional theory (DFT) single-point calculations were performed using the periodic Amsterdam density functional (ADF-BAND) package [41], [42] within generalized gradient approximation using the Perdew–Burke–Ernzerhof (PBE) [43] functional and a double zeta with polarization functions (DZP)-type basis set. The Brillouin zone was sampled by a 5 × 3 × 3 k-grid. Relativistic effects are treated with the scalar relativistic zero order regular approximation (ZORA) [44], [45]. The experimentally determined structure of linarite was employed without further optimization. Optimized structures of PbO and PbSO4 were taken from the literature [46]. Chemical bonding was analysed using the electron localization function (ELF) [47], [48] as included in ADF-BAND, providing a measure of electron pairing (a value of unity indicates perfect localization).

3 Crystal chemical description

The structural description of linarite so far mainly focused on the hydrogen bonding [14] and the copper-oxygen substructure [3], [22], [26], which is the striking structural motif for the quasi one-dimensional S = 1/2 frustrated-spin chain. A view of the PbCuSO4(OH)2 structure along the monoclinic axis is presented in Figure 3, emphasizing two important building groups, (i) the isolated SO4 2− tetrahedra and (ii) the strongly elongated CuO6 10− octahedra. The SO4 2− tetrahedra show S–O distances in a comparatively small range of 146.2–148.0 pm. These distances are in good agreement with those of previous work [12], [14] as well as in the anglesite structure (PbSO4, d(S–O): 142–148 pm [49]).

(left) Unit cell of PbCuSO4(OH)2. Lead, copper, oxygen and hydrogen atoms are drawn as grey, blue, red, and black circles, respectively. The elongated CuO6 (4 + 2 coordination) octahedra and the SO4 tetrahedra are emphasized. (right) Cutout of a chain of condensed CuO6 octahedra and SO4 tetrahedra. The longer Cu–O3 distances of 252.8 pm are emphasized by dashed lines.

The SO4

2− tetrahedra condense with the lead cations and build double-layers which extend in ab direction. These double-layers are further condensed in c direction with the copper-oxygen substructure. The formally very high charge density on the CuO6

10− octahedra is diminished by two different features: (i) the Cu2+ cations show a pronounced Jahn-Teller distortion (d(Cu–O4): 2 × 191.9 pm, d(Cu–O5): 2 × 197.3 pm and d(Cu–O3): 2 × 252.8 pm), and (ii) the O4 and O5 atoms correspond to the hydroxide groups. Neglecting the loosely bound O3 atoms and considering the substantial monoclinic distortion, the copper-oxygen coordination is distorted square-planar. These CuO4 units are trans edge-linked to infinite chains (Figure 4). Adjacent CuO4 units are slightly tilted with respect to each other. The copper atoms (Wyckoff site 2c) have centrosymmetric site symmetry

![Figure 4:

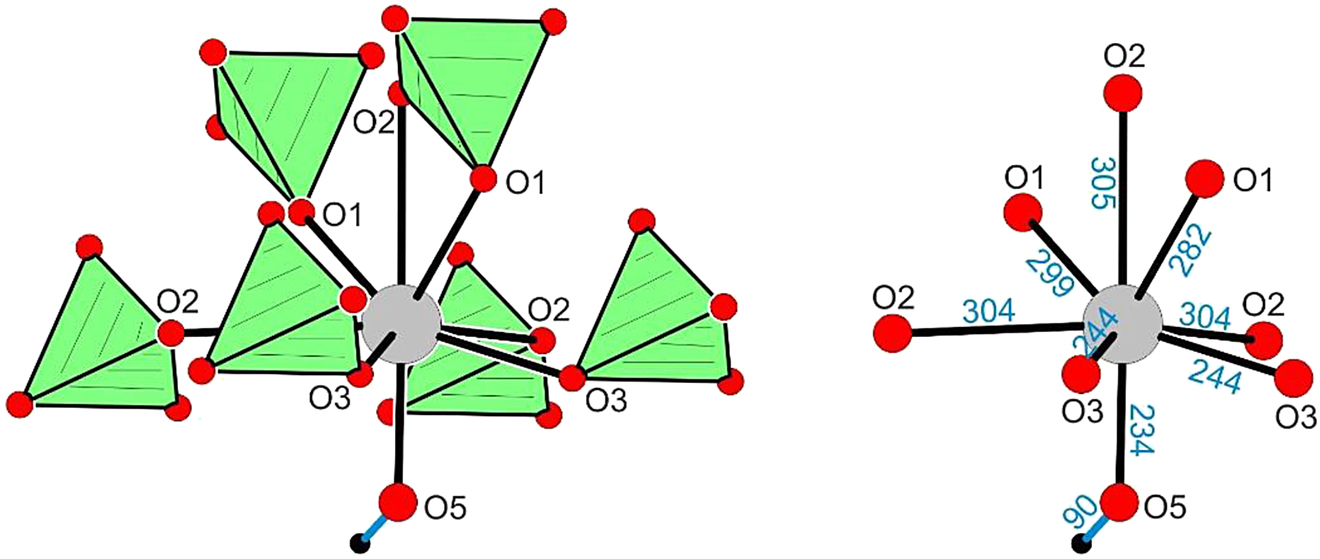

Cutout of the Cu(OH)2 substructures of Cu(OH)2 [41] (top) and PbCuSO4(OH)2 (bottom). Copper, oxygen and hydrogen atoms are drawn as blue, red, and black circles, respectively. Atom designations and relevant interatomic distances (in pm) are given.](/document/doi/10.1515/znb-2021-0041/asset/graphic/j_znb-2021-0041_fig_004.jpg)

Cutout of the Cu(OH)2 substructures of Cu(OH)2 [41] (top) and PbCuSO4(OH)2 (bottom). Copper, oxygen and hydrogen atoms are drawn as blue, red, and black circles, respectively. Atom designations and relevant interatomic distances (in pm) are given.

The CuO4 substructure of PbCuSO4(OH)2 is closely related to the structure of Cu(OH)2 (Figure 4) [50]. The striking difference concerns the orientation of the hydroxide groups. Cu(OH)2 is non-centrosymmetric (space group Cmc21) and the copper atoms on Wyckoff position 4a have site symmetry m and two slightly different Cu–O distances. The O1H1 and O2H2 groups point all to one side of each CuO4/2 ribbon. These 1D Cu(OH)2 ribbons are condensed via hydrogen bonding. For a more general overview on copper-oxygen substructures in complex oxides we refer to a detailed review by Eby and Hawthorne [51].

4 Lone-pair character at the lead cations

A final structural issue of linarite not discussed in the literature as yet concerns the coordination of the lead atoms. Each Pb2+ cation has eight oxygen neighbours (Figure 5), O5 from a hydroxide group, five oxygen atoms from end-on and two oxygen atoms from a side-on coordination of sulfate tetrahedra. In view of the similar Cu(OH)2 ribbons (Figure 4), at first sight one might consider PbCuSO4(OH)2 as a 1:1 intergrowth structure of PbSO4 and Cu(OH)2 slabs; however, the lead coordination in the anglesite structure is distinctly different (Figure 6). The coordination number therein is increased to 10, resulting from four end-on and three side-on coordinating sulfate tetrahedra.

Coordination of the lead atom (site symmetry m) in PbCuSO4(OH)2. Atom designations and relevant Pb–O distances (in pm) are given.

![Figure 6:

Coordination of the lead atom (site symmetry m) in PbSO4 [49]. Atom designations and relevant Pb–O distances (in pm) are given.](/document/doi/10.1515/znb-2021-0041/asset/graphic/j_znb-2021-0041_fig_006.jpg)

Coordination of the lead atom (site symmetry m) in PbSO4 [49]. Atom designations and relevant Pb–O distances (in pm) are given.

This difference is reflected in the calculated electronic structure, especially in the ELF. Figure 7 shows rather isotropic ELF values around the lead cations in PbSO4. In linarite, the density of spin-paired electrons is less symmetric around the lead cations (Figure 8). Yet, it does not display the typical localization basin pointing towards void space, associated with a lone pair, as is clearly visible for PbO in Figure 9 and in ref. [52], [53].

(a) Electron localization function (ELF) heat map of PbSO4 viewed along the crystallographic a axis. (b) ELF isosurface at a value of 0.4. Lead, sulfur and oxygen atoms are drawn as grey, yellow and red spheres, respectively.

Electron localization function (ELF) of linarite. View along the a axis (a) and the b axis (b) with isosurface value of 0.4. (c) Orientation of the coloured plane shown in (d). (d) ELF heat map viewed along the c axis. Lead, copper, sulfur, oxygen and hydrogen atoms are drawn as grey, orange, yellow, red, and white spheres, respectively.

Electron localization function (ELF) of PbO. (a) Isosurface at a value of 0.4. (b) Heat map. Lead and oxygen atoms are drawn as grey and red spheres, respectively.

Dedicated to: Professor Richard Dronskowski of the RWTH Aachen on the occasion of his 60th birthday.

Acknowledgements

We thank SIMMCG (Syndicat Intercommunal du Musée de la Mine de Cap Garonne) for supporting the scientific work within the mine and Dr. Carsten Paulmann and the beamline staff of P24, DESY, for their support during the diffraction experiments.

-

Author contributions: All the authors have accepted responsibility for the entire content of this submitted manuscript and approved submission.

-

Research funding: None declared.

-

Conflict of interest statement: The authors declare no conflicts of interest regarding this article.

References

1. Anthony, J. W., Bideaux, R. A., Bladh, K. W., Nichols, M. C., Eds. Linarite data sheet. In Handbook of Mineralogy. Mineralogical Society of America: Chantilly, VAUSA, 2021; pp. 20151–21110. http://www.handbookofmineralogy.org/.Search in Google Scholar

2. Lafuente, B., Downs, R. T., Yang, H., Stone, N. The power of databases: the RRUFF project. In Highlights in Mineralogical Crystallography; Armbruster, T., Danisi, R. M., Eds.; DeGruyter: Berlin, 2015, pp. 1–30. (data base entries R060130, R060472 and R120094).10.1515/9783110417104-003Search in Google Scholar

3. Schäper, M., Wolter, A. U. B., Drechsler, S.-L., Nishimoto, S., Müller, K.-H., Abdel-Hafiez, M., Schottenhamel, W., Büchner, B., Richter, J., Ouladdiaf, B., Uhlarz, M., Beyer, R., Skourski, Y., Wosnitza, J., Rule, K. C., Ryll, H., Klemke, B., Kiefer, K., Reehuis, M., Willenberg, B., Süllow, S. Phys. Rev. B 2013, 88, 184410 (17 pages).10.1103/PhysRevB.88.184410Search in Google Scholar

4. Wadlo, A. W. Am. Mineral. 1935, 20, 575–597.Search in Google Scholar

5. Berry, L. G. Am. Mineral. 1951, 36, 511–512.Search in Google Scholar

6. Araki, T. Mem. Coll. Sci., Univ. Kyoto, Ser. A 1958, 25, 69–79.Search in Google Scholar

7. Bachmann, H.-G., Zemann, J. Naturwissenschaften 1960, 47, 177; https://doi.org/10.1007/bf00639741.Search in Google Scholar

8. Bachmann, H.-G. Fortschr. Mineral. 1961, 39, 86a.Search in Google Scholar

9. Bachmann, H. G., Zemann, J. Acta Crystallogr. 1961, 14, 747–753; https://doi.org/10.1107/s0365110x61002254.Search in Google Scholar

10. Araki, T. Mineral. J. 1962, 3, 282–295; https://doi.org/10.2465/minerj1953.3.282.Search in Google Scholar

11. Powell, H. E., Ballard, L. N. Magnetic susceptibility of copper-, lead-, and zinc-bearing minerals. In Bureau of Mines Information Circular, Washington, Vol. 8383, 1968.Search in Google Scholar

12. Effenberger, H. Mineral. Petrol. 1987, 36, 3–12; https://doi.org/10.1007/bf01164365.Search in Google Scholar

13. Chebotareva, N. V., Semenova, T. F., Filatov, S. K., Serafimova, E. K. Volcanol. Seismol. 1999, 20, 335–342.10.1542/pir.20.10.335Search in Google Scholar

14. Schofield, P. F., Wilson, C. C., Knight, K. S., Kirk, C. A. Can. Mineral. 2009, 47, 649–662; https://doi.org/10.3749/canmin.47.3.649-662.Search in Google Scholar

15. Bykova, E. Yu., Marsii, I. M., Nasedkin, V. V., Borisovskii, S. E., Glavathkikh, S. F., Gorshkov, A. I., Ziborova, T. A. Dokl. Akad. Nauk. 1993, 333, 469–472.Search in Google Scholar

16. Sudhana, B. M., Reddy, B. J., Vedanand, S., Reddy, Y. P., Rao, P. S. Eff. Defects Solids 1995, 133, 217–224; https://doi.org/10.1080/10420159508223992.Search in Google Scholar

17. Babonas, G.-J., Maltsev, V., Rėza, A., Baran, M., Deyev, S., Shvanskaya, L., Kindurys, A., Vaišnoras, R. Lith. J. Phys. 2001, 41, 299–304.Search in Google Scholar

18. Babonas, G. J., Szymczak, R., Baran, M., Reza, A., Maltsev, V., Sabataityte, J., Dyeyev, S. Cryst. Eng. 2002, 5, 209–216; https://doi.org/10.1016/s1463-0184(02)00031-x.Search in Google Scholar

19. Constable, E., Squires, A. D., Rule, K. C., Lewis, R. A. Far-infrared spectroscopy of quantum spin chain: PbCuSO4(OH)2. In 2015 40th International Conference on Infrared, Millimeter, and Terahertz waves (IRMMW-THz), Hong Kong, 2015, pp. 1–2; https://doi.org/10.1109/IRMMW-THz.2015.7327664.Search in Google Scholar

20. Baran, M., Jedrzejczak, A., Szymczak, H., Maltsev, V., Kamieniarz, G., Szukowski, G., Loison, C., Ormeci, A., Drechsler, S.-L., Rosner, H. Phys. Status Solidi C 2006, 3, 220–224; https://doi.org/10.1002/pssc.200562523.Search in Google Scholar

21. Szymczak, R., Szymczak, H., Kamieniarz, G., Szukowski, G., Jaśniewicz-Pacer, K., Florek, W., Maltsev, V., Babonas, G. J. Acta Phys. Pol., A 2009, 115, 925–930; https://doi.org/10.12693/aphyspola.115.925.Search in Google Scholar

22. Willenberg, B., Schäper, M., Rule, K. C., Süllow, S., Reehuis, M., Ryll, H., Klemke, B., Kiefer, K., Schottenhamel, W., Büchner, B., Ouladdiaf, B., Uhlarz, M., Beyer, R., Wosnitza, J., Wolter, A. U. B. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2012, 108, 117202; https://doi.org/10.1103/physrevlett.108.117202.Search in Google Scholar

23. Wolter, A. U. B., Lipps, F., Schäper, M., Drechsler, S.-L., Nishimoto, S., Vogel, R., Kataev, V., Büchner, B., Rosner, H., Schmitt, M., Uhlarz, M., Skourski, Y., Wosnitza, J., Süllow, S., Rule, K. C. Phys. Rev. B 2012, 85, 014407 (16 pages); https://doi.org/10.1103/physrevb.85.014407.Search in Google Scholar

24. Schäpers, M., Rosner, H., Drechsler, S.-L., Süllow, S., Vogel, R., Büchner, B., Wolter, A. U. B. Phys. Rev. B 2014, 90, 224417 (14 pages); https://doi.org/10.1103/physrevb.90.224417.Search in Google Scholar

25. Willenberg, B., Schäpers, M., Wolter, A. U. B., Drechsler, S.-L., Reehuis, M., Hoffmann, J.-U., Büchner, B., Studer, A. J., Rule, K. C., Ouladdiaf, B., Süllow, S., Nishimoto, S. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2016, 116, 047202 (5 pages); https://doi.org/10.1103/physrevlett.116.047202.Search in Google Scholar

26. Rule, K. C., Willenberg, B., Schäpers, M., Wolter, A. U. B., Büchner, B., Drechsler, S.-L., Ehlers, G., Tennant, D. A., Mole, R. A., Gardner, J. S., Süllow, S., Nishimoto, S. Phys. Rev. B 2017, 95, 024430 (6 pages); https://doi.org/10.1103/physrevb.95.024430.Search in Google Scholar

27. Feng, Y., Povarov, K. Yu., Zheludev, A. Phys. Rev. B 2018, 98, 054419 (7 pages); https://doi.org/10.1103/physrevb.98.054419.Search in Google Scholar

28. Cemal, E., Enderle, M., Kremer, R. K., Fåk, B., Ressouche, E., Goff, J. P., Gvozdikova, M. V., Zhitomirsky, M. E., Ziman, T. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2018, 120, 067203 (6 pages) https://doi.org/10.1103/physrevlett.120.067203.Search in Google Scholar

29. Heinze, L., Bastien, G., Ryll, B., Hoffmann, J.-U., Reehuis, M., Ouladdiaf, B., Bert, F., Kermarrec, E., Mendels, P., Nishimoto, S., Drechsler, S.-L., Rößler, U. K., Rosner, H., Büchner, B., Studer, A. J., Rule, K. C., Süllow, S., Wolter, A. U. B. Phys. Rev. B 2019, 99, 094436 (14 pages); https://doi.org/10.1103/physrevb.99.094436.Search in Google Scholar

30. Gotovko, S. K., Svistov, L. E., Kuzmenko, A. M., Pimenov, A., Zhitomirsky, M. E. Phys. Rev. B 2019, 100, 174412 (12 pages); https://doi.org/10.1103/physrevb.100.174412.Search in Google Scholar

31. Yasui, Y., Sato, M., Terasaki, I. J. Phys. Soc. Jpn. 2011, 80, 033707 (4 pages); https://doi.org/10.1143/jpsj.80.033707.Search in Google Scholar

32. Povarov, K. Yu., Feng, Y., Zheludev, A. Phys. Rev. B 2016, 94, 214409 (10 pages); https://doi.org/10.1103/physrevb.94.214409.Search in Google Scholar

33. Mack, T., Ruff, A., Krug von Nidda, H.-A., Loidl, A., Krohns, S. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 4460 (7 pages); https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-04752-z.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

34. Favreau, G., Galéa-Clolus, V. Cap Garonne; Association des Amis de la Mine de Cap Garonne (AAMCG) – Association Française de Microminéralogie (AFM), Couleur et Impression Les Arcades; Castelnau-Le-Lez: France, 2014.Search in Google Scholar

35. Mumme, W. G., Sarp, H., Chiappero, P. J. Archaeol. Sci. 1994, 47, 117–124.Search in Google Scholar

36. CrysAlis Pro Software System. Intelligent Data Collection and Processing Software for Small Molecule and Protein Crystallography; Rigaku Oxford Diffraction: Yarnton, Oxfordshire (U. K.), 2014.Search in Google Scholar

37. Sheldrick, G. M. Sadabs. Bruker AXS Inc.: Madison, Wisconsin (USA), 2001.Search in Google Scholar

38. Villars, P., Cenzual, K., Eds. Pearson’s Crystal Data: Crystal Structure Database for Inorganic Compounds (release 2020/21); ASM International®: Materials Park, Ohio (USA), 2020.Search in Google Scholar

39. Sheldrick, G. M. Acta Crystallogr. 2015, C71, 3–8.Search in Google Scholar

40. Massa, W. Kristallstrukturbestimmung, 8. Auflage; Springer Spektrum: Berlin, 2015.10.1007/978-3-658-09412-6Search in Google Scholar

41. te Velde, G., Baerends, E. J. Phys. Rev. B 1991, 44, 7888–7903; https://doi.org/10.1103/physrevb.44.7888.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

42. BAND 2019.3. SCM, Theoretical Chemistry; Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam: Amsterdam (The Netherlands), 2019. http://www.scm.com.Search in Google Scholar

43. Perdew, J. P., Burke, K., Ernzerhof, M. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1996, 77, 3865–3868; https://doi.org/10.1103/physrevlett.77.3865.Search in Google Scholar

44. Philipsen, P. H. T., van Lenthe, E., Snijders, J. G., Baerends, E. J. Phys. Rev. B 1997, 56, 13556–13562; https://doi.org/10.1103/physrevb.56.13556.Search in Google Scholar

45. Philipsen, P. H. T., Baerends, E. J. Phys. Rev. B 2000, 61, 1773–1778; https://doi.org/10.1103/physrevb.61.1773.Search in Google Scholar

46. Jain, A., Ong, S. P., Hautier, G., Chen, W., Richards, W. D., Dacek, S., Cholia, S., Gunter, D., Skinner, D., Ceder, G., Persson, K. A. APL Mater. 2013, 1, 011002; https://materialsproject.org.10.1063/1.4812323Search in Google Scholar

47. Becke, A. D., Edgecombe, K. E. J. Chem. Phys. 1990, 92, 5397–5403; https://doi.org/10.1063/1.458517.Search in Google Scholar

48. Savin, A., Jepsen, O., Flad, J., Andersen, O. K., Preuss, H., von Schnering, H. G. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. Engl. 1992, 31, 187–188; https://doi.org/10.1002/anie.199201871.Search in Google Scholar

49. Sahl, K. Beitr. Mineral. Petrogr. 1963, 9, 111–132.10.1007/BF02679983Search in Google Scholar

50. Oswald, H. R., Reller, A., Schmalle, H. W., Dubler, E. Acta Crystallogr. 1990, C46, 2279–2284; https://doi.org/10.1107/s0108270190006230.Search in Google Scholar

51. Eby, R. K., Hawthorne, F. C. Acta Crystallogr. 1993, B49, 28–56; https://doi.org/10.1107/s0108768192007274.Search in Google Scholar

52. Raulot, J.-M., Baldinozzi, G., Seshadri, R., Cortona, P. Solid State Sci. 2002, 4, 467–474.10.1016/S1293-2558(02)01280-3Search in Google Scholar

53. Walsh, A., Watson, G. W. J. Solid State Chem. 2005, 178, 1422–1428; https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jssc.2005.01.030.Search in Google Scholar

© 2021 Walter de Gruyter GmbH, Berlin/Boston

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- In this issue

- Laudatio/Preface

- Celebrating the 60th birthday of Richard Dronskowski

- Review

- Orbital-selective electronic excitation in phase-change memory materials: a brief review

- Research Articles

- Solving the puzzle of the dielectric nature of tantalum oxynitride perovskites

- d- and s-orbital populations in the d block: unbound atoms in physical vacuum versus chemical elements in condensed matter. A Dronskowski-population analysis

- Single-crystal structures of A 2SiF6 (A = Tl, Rb, Cs), a better structure model for Tl3[SiF6]F, and its novel tetragonal polymorph

- Na2La4(NH2)14·NH3, a lanthanum-rich intermediate in the ammonothermal synthesis of LaN and the effect of ammonia loss on the crystal structure

- Linarite from Cap Garonne

- Salts of octabismuth(2+) polycations crystallized from Lewis-acidic ionic liquids

- High-temperature diffraction experiments and phase diagram of ZrO2 and ZrSiO4

- Thermal conversion of the hydrous aluminosilicate LiAlSiO3(OH)2 into γ-eucryptite

- Crystal structure of mechanochemically prepared Ag2FeGeS4

- Effect of nanostructured Al2O3 on poly(ethylene oxide)-based solid polymer electrolytes

- Sr7N2Sn3: a layered antiperovskite-type nitride stannide containing zigzag chains of Sn4 polyanions

- Exploring the frontier between polar intermetallics and Zintl phases for the examples of the prolific ALnTnTe3-type alkali metal (A) lanthanide (Ln) late transition metal (Tn) tellurides

- Zwitterion coordination to configurationally flexible d 10 cations: synthesis and characterization of tetrakis(betaine) complexes of divalent Zn, Cd, and Hg

- An approach towards the synthesis of lithium and beryllium diphenylphosphinites

- Synthesis, crystal and electronic structure of CaNi2Al8

- Crystal and electronic structure of the new ternary phosphide Ho5Pd19P12

- Synthesis, structure, and magnetic properties of the quaternary oxysulfides Ln 5V3O7S6 (Ln = La, Ce)

- Synthesis, crystal and electronic structure of BaLi2Cd2Ge2

- Structural variations of trinitrato(terpyridine)lanthanoid complexes

- Preparation of CoGe2-type NiSn2 at 10 GPa

- Controlled exposure of CuO thin films through corrosion-protecting, ALD-deposited TiO2 overlayers

- Experimental and computational investigations of TiIrB: a new ternary boride with Ti1+x Rh2−x+y Ir3−y B3-type structure

- Synthesis and crystal structure of the lanthanum cyanurate complex La[H2N3C3O3]3 · 8.5 H2O

- Cd additive effect on self-flux growth of Cs-intercalated NbS2 superconducting single crystals

- 14N, 13C, and 119Sn solid-state NMR characterization of tin(II) carbodiimide Sn(NCN)

- Superexchange interactions in AgMF4 (M = Co, Ni, Cu) polymorphs

- Copper(I) iodide-based organic–inorganic hybrid compounds as phosphor materials

- On iodido bismuthates, bismuth complexes and polyiodides with bismuth in the system BiI3/18-crown-6/I2

- Synthesis, crystal structure and selected properties of K2[Ni(dien)2]{[Ni(dien)]2Ta6O19}·11 H2O

- First low-spin carbodiimide, Fe2(NCN)3, predicted from first-principles investigations

- A novel ternary bismuthide, NaMgBi: crystal and electronic structure and electrical properties

- Magnetic properties of 1D spin systems with compositional disorder of three-spin structural units

- Amine-based synthesis of Fe3C nanomaterials: mechanism and impact of synthetic conditions

- Enhanced phosphorescence of Pd(II) and Pt(II) complexes adsorbed onto Laponite for optical sensing of triplet molecular dioxygen in water

- Theoretical investigations of hydrogen absorption in the A15 intermetallics Ti3Sb and Ti3Ir

- Assembly of cobalt-p-sulfonatothiacalix[4]arene frameworks with phosphate, phosphite and phenylphosphonate ligands

- Chiral bis(pyrazolyl)methane copper(I) complexes and their application in nitrene transfer reactions

- UoC-6: a first MOF based on a perfluorinated trimesate ligand

- PbCN2 – an elucidation of its modifications and morphologies

- Flux synthesis, crystal structure and electronic properties of the layered rare earth metal boride silicide Er3Si5–x B. An example of a boron/silicon-ordered structure derived from the AlB2 structure type

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- In this issue

- Laudatio/Preface

- Celebrating the 60th birthday of Richard Dronskowski

- Review

- Orbital-selective electronic excitation in phase-change memory materials: a brief review

- Research Articles

- Solving the puzzle of the dielectric nature of tantalum oxynitride perovskites

- d- and s-orbital populations in the d block: unbound atoms in physical vacuum versus chemical elements in condensed matter. A Dronskowski-population analysis

- Single-crystal structures of A 2SiF6 (A = Tl, Rb, Cs), a better structure model for Tl3[SiF6]F, and its novel tetragonal polymorph

- Na2La4(NH2)14·NH3, a lanthanum-rich intermediate in the ammonothermal synthesis of LaN and the effect of ammonia loss on the crystal structure

- Linarite from Cap Garonne

- Salts of octabismuth(2+) polycations crystallized from Lewis-acidic ionic liquids

- High-temperature diffraction experiments and phase diagram of ZrO2 and ZrSiO4

- Thermal conversion of the hydrous aluminosilicate LiAlSiO3(OH)2 into γ-eucryptite

- Crystal structure of mechanochemically prepared Ag2FeGeS4

- Effect of nanostructured Al2O3 on poly(ethylene oxide)-based solid polymer electrolytes

- Sr7N2Sn3: a layered antiperovskite-type nitride stannide containing zigzag chains of Sn4 polyanions

- Exploring the frontier between polar intermetallics and Zintl phases for the examples of the prolific ALnTnTe3-type alkali metal (A) lanthanide (Ln) late transition metal (Tn) tellurides

- Zwitterion coordination to configurationally flexible d 10 cations: synthesis and characterization of tetrakis(betaine) complexes of divalent Zn, Cd, and Hg

- An approach towards the synthesis of lithium and beryllium diphenylphosphinites

- Synthesis, crystal and electronic structure of CaNi2Al8

- Crystal and electronic structure of the new ternary phosphide Ho5Pd19P12

- Synthesis, structure, and magnetic properties of the quaternary oxysulfides Ln 5V3O7S6 (Ln = La, Ce)

- Synthesis, crystal and electronic structure of BaLi2Cd2Ge2

- Structural variations of trinitrato(terpyridine)lanthanoid complexes

- Preparation of CoGe2-type NiSn2 at 10 GPa

- Controlled exposure of CuO thin films through corrosion-protecting, ALD-deposited TiO2 overlayers

- Experimental and computational investigations of TiIrB: a new ternary boride with Ti1+x Rh2−x+y Ir3−y B3-type structure

- Synthesis and crystal structure of the lanthanum cyanurate complex La[H2N3C3O3]3 · 8.5 H2O

- Cd additive effect on self-flux growth of Cs-intercalated NbS2 superconducting single crystals

- 14N, 13C, and 119Sn solid-state NMR characterization of tin(II) carbodiimide Sn(NCN)

- Superexchange interactions in AgMF4 (M = Co, Ni, Cu) polymorphs

- Copper(I) iodide-based organic–inorganic hybrid compounds as phosphor materials

- On iodido bismuthates, bismuth complexes and polyiodides with bismuth in the system BiI3/18-crown-6/I2

- Synthesis, crystal structure and selected properties of K2[Ni(dien)2]{[Ni(dien)]2Ta6O19}·11 H2O

- First low-spin carbodiimide, Fe2(NCN)3, predicted from first-principles investigations

- A novel ternary bismuthide, NaMgBi: crystal and electronic structure and electrical properties

- Magnetic properties of 1D spin systems with compositional disorder of three-spin structural units

- Amine-based synthesis of Fe3C nanomaterials: mechanism and impact of synthetic conditions

- Enhanced phosphorescence of Pd(II) and Pt(II) complexes adsorbed onto Laponite for optical sensing of triplet molecular dioxygen in water

- Theoretical investigations of hydrogen absorption in the A15 intermetallics Ti3Sb and Ti3Ir

- Assembly of cobalt-p-sulfonatothiacalix[4]arene frameworks with phosphate, phosphite and phenylphosphonate ligands

- Chiral bis(pyrazolyl)methane copper(I) complexes and their application in nitrene transfer reactions

- UoC-6: a first MOF based on a perfluorinated trimesate ligand

- PbCN2 – an elucidation of its modifications and morphologies

- Flux synthesis, crystal structure and electronic properties of the layered rare earth metal boride silicide Er3Si5–x B. An example of a boron/silicon-ordered structure derived from the AlB2 structure type