Abstract

The three nitrides ε-TaN, δ-NbN and γ′-Mo2N have been synthesized electrochemically from the elements at 450°C in a molten salt mixture LiCl/KCl:Li3N. For all compounds the working electrode consisting of a tantalum, niobium or molybdenum foil was anodically polarized and the system was fed with dry nitrogen. The applied constant voltage was 2.5 V (for ε-TaN), 2.2 V (for δ-NbN), and 2.8 V (for γ′-Mo2N). Chemical analysis on N and O resulted in compositions of TaN0.81(1)O0.13(2), NbN1.17(2)O0.28(1) and MoN0.88(1)O0.11(1), respectively. Lattice parameters of ε-TaN refined by the Rietveld method are a = 519.537(4) and c = 291.021(3) pm. The other two nitrides crystallize in the cubic system (rocksalt type) with a = 436.98(2) pm for δ-NbN and with a = 417.25(2) pm for γ′-Mo2N.

1 Introduction

The interest in the chemistry of nitrides has steadily increased during the past decades, due to their high potential in various fields of applications [1]. One category of these nitrides are interstitial nitrides, which possess several technologically relevant characteristics like high hardness and strength, high thermal and electrical conductivity, primarily in non-stoichiometric phases due to a complex electronic situation and chemical bonding including ionic, metallic and covalent components [2]. Frequently, the synthesis of binary nitrides employs high temperature reactions of the metals or precursors thereof with nitrogen or ammonia [1], [3], [4]. Such reactions suffer from the low thermal stability of nitrogen-rich phases concomitant to the elevated temperatures necessary to activate dinitrogen, or, alternatively, from the corrosive and harmful properties of ammonia. For some time, we have been developing an electrochemical synthesis in a molten salt system in order to produce bulk nitrides at rather low temperatures avoiding the use of ammonia [5], [6]. Earlier, thin films of AlN [7], GaN [8], InN [8], TiN [9], CrN/Cr2N [10], Co3N [11], ε-Fe2N1−x/γ′-Fe4N [12], [13], ZrN [14] and amorphous SnNx [15] were produced by a similar technique. Recently, we have presented the electrochemical bulk synthesis of ε-Fe3N1.5, Co3InN and Ni3InN, all with rather high nitrogen contents [5], [6].

The system Ta–N contains a variety of stable and metastable phases ranging from the nitrogen-richest compound Ta3N5 [16] via Ta2N3 [17], Ta4N5 [18], Ta5N6 [18], three modifications of TaN (ε, δ, θ) [19], [20], [21], [22], [23], [24], [25], and β-Ta2N [18], [19], [20], [26], to α-Ta(N), the solid solution of nitrogen in tantalum [19], [20]. One focus of the work presented here is the electrochemical synthesis and characterization of ε-TaN. This hexagonal phase with a very narrow homogeneity range was proposed by Schönberg and Brauer in 1954, having a B35 CoSn-type structure (space group P6/mmm) and a composition of TaN1.00 [19], [20]. For the synthesis, Schönberg reacted tantalum metal or tantalum hydride with gaseous ammonia at T=1000°C [19]. Another possibility is the heating of tantalum powder in a nitrogen atmosphere for 6 h at 1400°C, which was proposed by Brauer and Zapp [20]. Later, Christensen reinvestigated the crystal structure of ε-TaN using neutron diffraction and suggested P6̅2m as the correct space group [27]. For the synthesis he reacted tantalum powder and nitrogen gas, which resulted in a mixture of ε-TaN and β-Ta2N. In order to produce a single-phase sample the mixture was heated to 1450°C under a nitrogen pressure of 1.4 MPa [27]. In 2005, a phase mixture of nanocrystalline hexagonal ε-TaN and cubic δ-TaN was obtained from the mixture of TaCl5, NH4Cl and Na kept in an autoclave at 650°C for 8 h [28].

As already noted by Schönberg [19], those tantalum nitrides are very susceptive for incorporating oxide impurities. In some way, materials like TaNyOx benefit from the combination of favorable properties of tantalum nitride and tantalum oxide: tantalum nitrides are known for being corrosion resistant and chemically inert hard ceramics. Tantalum oxide, Ta2O5, is known for its high refractive index, large band gap and high dielectric constant [29]. In 1954, Schönberg described four phases in the ternary system Ta–N–O, namely TaN0.90O0.10, TaN0.75O0.25, TaN0.65O0.35 and TaN0.50O0.50. The preparation of the samples was performed from ε-TaN or δ-TaN0.8−0.90 as starting materials with the help of steam in the presence of hydrogen at about 700°C. Unfortunately, the synthesis of the different phases was not described in more detail [30]. Shortly thereafter, Brauer et al. reported the formation of β-TaON from Ta2O5 and wet NH3 at 790°C [31], [32]. A second polymorph α-TaON was claimed by Buslaev, obtained from the decomposition of NH4TaCl6 at 400°C, which resulted in the formation of Ta2N3Cl, followed by hydrolysis [33]. However, this phase seems to be questionable according to quantum-chemical calculations [34]. In 2007 the metastable polymorph γ-TaON was synthesized by ammonolysis of β-Ta2O5 at 600–1000°C [35].

The system Nb–N is similarly complex and contains several phases, namely Nb3N4, Nb4N5, Nb5N6, NbN (δ, δ′, ε, η), γ′-Nb4N3, β-Nb2N and α-NbNx (x<0.13) [36], [37], [38]. Especially, δ-NbN is a high-temperature phase, stable above 1370°C. It crystallizes with a rocksalt-type structure and the exact composition depends on the temperature and nitrogen pressure applied during synthesis [39]. At T=1400°C, the homogeneity range is located between NbN0.88 and NbN0.98 [40]. Due to its favorable combination of superconducting and mechanical properties, δ-NbN is a promising material for hot electron photodetectors, carbon nanotube junctions or radio frequency superconducting accelerator cavities [41]. One possibility to synthesize this niobium nitride is the reaction of niobium in an N2 atmosphere at 1450°C [42]. At 1400°C in an NH3 atmosphere, fibers of δ-NbN can be obtained by thermal conversion of niobium alkoxide-cellulose acetate gel fibers [43]. Oxide nitrides are also known for niobium. A very slow temperature rise leads to the thermal decomposition of NbOCl2N3 at 500°C, which results in baddeleyite-type NbON crystals [44].

The Mo–N phase diagram includes hexagonal Mo5N6 [45], three modifications of MoN (WC-type, NiAs-type, distorted NiAs-type) [46], [47], [48], [49], and the nitrides β-Mo2N and γ′-Mo2N. The β-phase is a tetragonal low-temperature modification, and the γ′-form the corresponding cubic high-temperature modification [50], [51], [52]. Both phases are separated by a two-phase region. In general, the homogeneity range of γ′-Mo2N ranges from 28.7 to 34.5 at% N [53]. Especially, γ′-Mo2N is known for its superconducting properties below 5.2 K [52] and its catalytic activity [54]. There are various methods to synthesize this compound, like a metathesis reaction between MoCl5 and Ca3N2 [55] or heating of MoCl5 under N2/H2 gas at 650°C [56]. Further possibilities are the conversion of nitridotris(neopentyl)molybdenum(VI) in N2 at 500°C [57] or of a mixture of MoCl5 and urea in acetonitrile in N2 at 600°C [58], but the preparation of bulk γ′-Mo2Nx with x>1 in high quality is still a challenge. γ′-Mo2N1.34 was obtained from Na2MoO4 and h-BN at 1300°C and pressures of up to 5 GPa [59]. Reports about the preparation and the structural properties of molybdenum oxide nitrides are rare [60]. Mostly MoO3 was used as a starting material. Mo(O,N)3−δ, for example, can be produced by ammonolysis of α-MoO3 at 275°C in a topotactic reaction [61].

In this study, we demonstrate the electrochemical synthesis of three binary refractory nitrides, namely ε-TaN, δ-NbN and γ′-Mo2N, as an alternative method, avoiding harmful gases or high temperatures.

2 Experimental section

The description of the electrochemical cell used in this study was earlier given in detail [6]. All manipulations were carried out in an argon-filled glove box. Prior to the electrochemical transition metal nitride synthesis, Li3N was produced from Li pieces annealed under nitrogen at 170°C (36 h) followed by heating to 225°C (2 h). Additionally, LiCl (Grüssing, 99%) and KCl (Burdick & Jackson, for analysis) were dried under dynamic vacuum for several hours at 200°C. A tantalum (for ε-TaN), niobium (for δ-NbN) or molybdenum foil (for γ′-Mo2N) was connected to a pure molybdenum wire and served as the working electrode. A second pure molybdenum wire was used as a counter electrode. 0.5 mol% Li3N were added to the eutectic chloride mixture (59 mol% LiCl, 41 mol% KCl) to assist as nitrogen reservoir. The mixture was molten in a high-purity alumina crucible under argon atmosphere. The operation temperature of the electrochemical synthesis was 450°C and the applied constant voltage 2.5 V (for ε-TaN), 2.2 V (for δ-NbN), and 2.8 V (for γ′-Mo2N). During synthesis, the electrical current at constant voltage diminished continuously and after 5 h (for ε-TaN), 2.5 h (for δ-NbN) and 4 h (for γ′-Mo2N) the electrochemical synthesis was interrupted when the current reached zero. The binary transition metal nitrides were recovered at the bottom of the crucible below the electrode, washed several times with deionized water and dried at 50°C for 3 days.

2.1 Characterization

Powder X-ray diffraction patterns of the microcrystalline samples were obtained at room temperature on a STOE Stadi-p diffractometer (STOE, Darmstadt, Germany) equipped with a Ge(111) monochromator and a Mythen1K detector in the 2θ range of 5–65° applying MoKα1 radiation in transmission geometry. The structure refinements were carried out using the FullProf program suite [62].

CSD 1897836 (ε-TaN) contains the supplementary crystallographic data for this paper. These data can be obtained free of charge from The Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre viawww.ccdc.cam.ac.uk/data_request/cif.

Chemical analyses of N, O and H were performed by the hot gas extraction method with a LECO ONH836 instrument (LECO corporation, Saint Joseph, MI, USA).

An electron-beam microprobe analysis of type CAMECA SX 100 (Cameca SAS, Gennevilliers, France) with a Si-drift detector (Thermo Fischer Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) proved the absence of further metallic elements.

TG measurements were performed on a STA 449C Jupiter instrument (Netzsch Gerätebau GmbH, Selb, Germany).

3 Results and discussion

Compared to conventional syntheses of binary transition metal nitrides, the electrochemical synthesis avoids harmful and corrosive ammonia for direct nitridation of refractory metals or for the ammonolysis of precursors like transition metal halides, hydrides or else. Concomitantly, the synthesis is successful at significantly lower temperatures than those required for the reaction of the metals with gaseous nitrogen [5], [6]. Merely a nitrogen reservoir of Li3N is needed to be added to the LiCl-KCl electrolyte in order to provide an initial nitride source for the melt. Li3N was reported to show a good solubility in molten LiCl (15 mol%) at 650°C, although this solubility decreases by adding KCl [63]. In this study, only a small amount of Li3N served as a nitrogen reservoir in the eutectic mixture LiCl-KCl. Therefore, we regard it as save to assume the Li3N is dissolved in the salt mixture, particularly since there is no evidence for the formation of a second phase. A nitrogen gas electrode (pure nitrogen gas fed into the system to bath the cathode) allows a continuous supply of nitride ions for the surface nitriding process of the anode via cathodic reduction of nitrogen gas [64]. The formed binary nitrides can be recovered below the working electrode in bulk form. Typically, the nitrides obtained in the electrochemical synthesis show a rather high nitrogen content at the upper border of the homogeneity range or even beyond, as we have observed previously also for iron nitrides and ternary perovskite nitrides [5], [6].

3.1 Electrochemical synthesis of ε-TaN

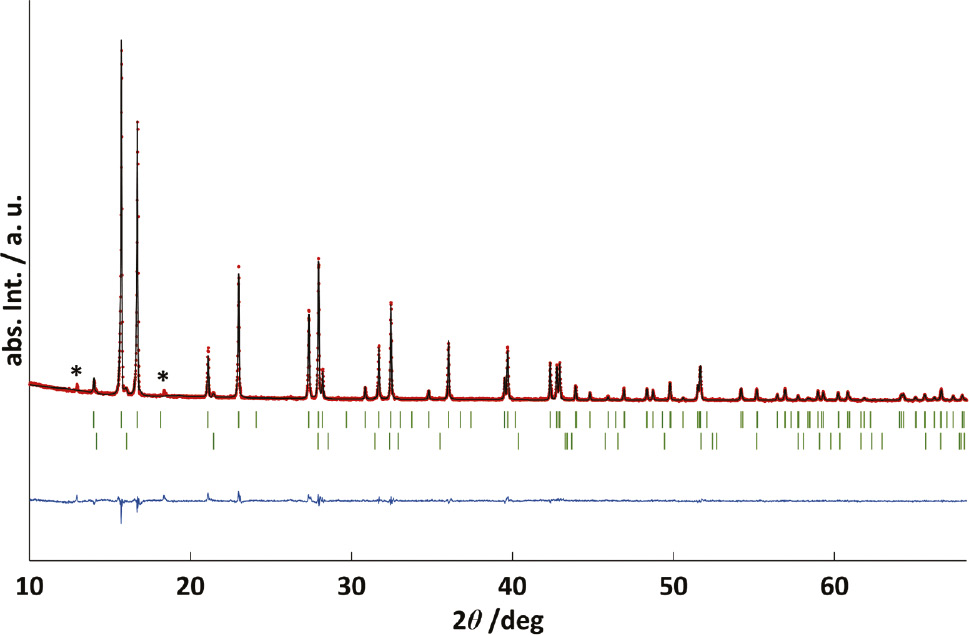

After the anodic nitridation of tantalum foil at a voltage of 2.5 V and an operation temperature of 450°C in a salt melt, a black sample of ε-TaN was obtained. Figure 1 shows the Rietveld refinement of ε-TaN in space group P6̅2m with a small impurity of δ-TaN0.8 in P6̅m2 [19], [21].

Rietveld refinement of the crystal structure of ε-TaN (MoKα1): observed (red circles), calculated (solid black line) and difference (observed – calculated, blue line) powder diffraction pattern. Vertical bars indicate the Bragg positions of ε-TaN (above) and a minor impurity of δ-TaN0.8 (below, green). Reflections marked with an asterisk (*) are due to a minor impurity of unknown composition, which do not seem to belong to a simple superstructure of the known hexagonal unit cell.

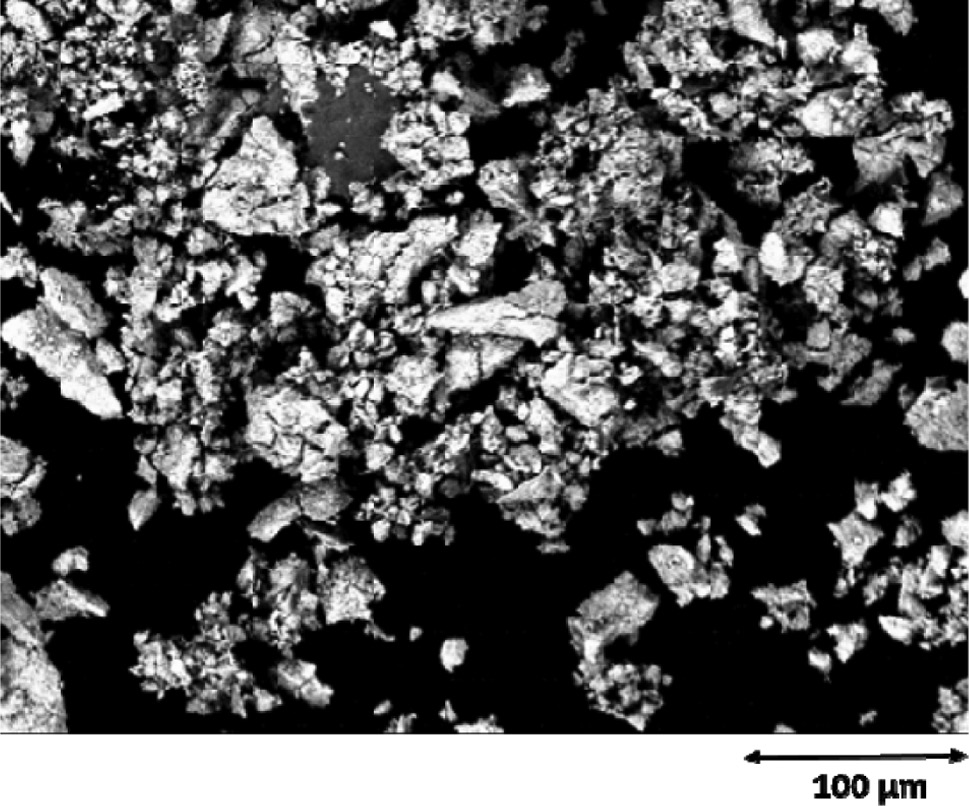

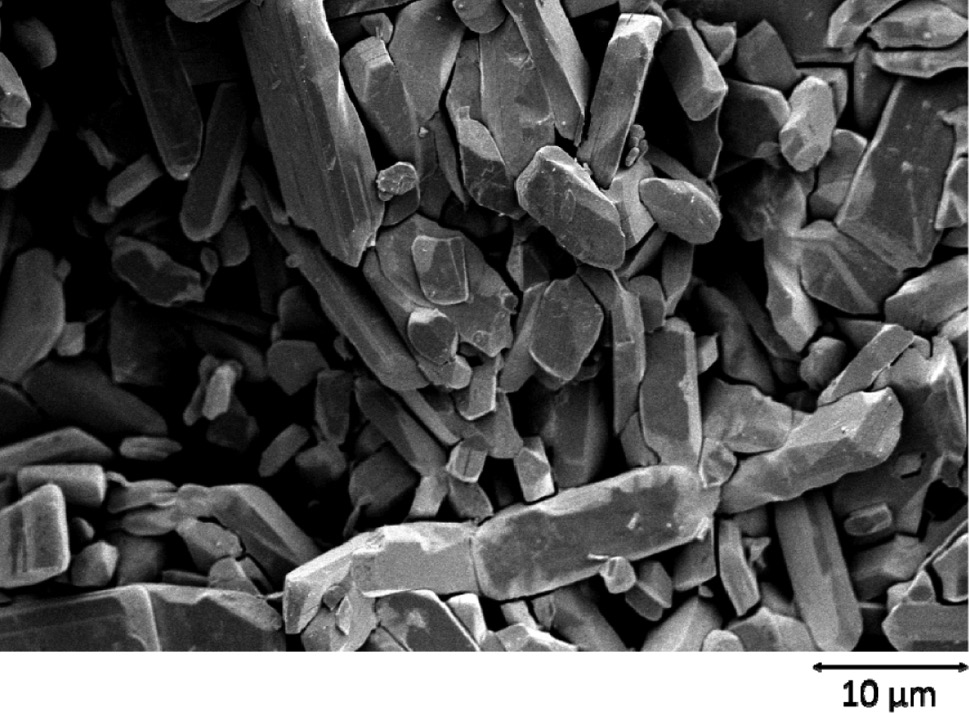

The predominant phase ε-TaN crystallizes hexagonally in space group P6̅2m with a=519.537(4) pm and c=291.021(3) pm. The obtained lattice parameters are close to the reported data of a=519.6 pm and c=291.1 pm [21]. Additionally, a small amount of δ-TaN0.8 (about 0.5 wt.-%) crystallizes hexagonally in space group P6̅m2 with a=293.77(8) pm and c=288.2(1) pm, in agreement with the reported data of a=293.1 pm and c=287.9 pm [19]. In order to properly describe the reflections of this minor impurity, the nitrogen content was fixed to 0.8 according to the literature report. The elemental analysis on N, O and H of the bulk product results in a composition of TaN0.81(1)O0.13(2)H0.014(1), representing a composition Ta(N,O)0.94 with relatively high occupation of the non-metal site as already indicated by the rather large unit cell parameters. The partial substitution of nitride ions by oxide ions in such compounds typically leads to slightly reduced unit cell parameters compared to a pure nitride due to the smaller ionic radius of O2− (140 pm [65]) relative to N3− (150 pm [66]). The oxide nitride TaN~0.90O~0.10 has reported lattice parameters of a=1034 pm and c=580.2 pm with a ratio of c/a=0.561 [30], which resembles the obtained value c/a=0.560 for ε-TaN (see Table 1). The high oxygen content in the product is probably caused by oxygen impurities in the feed nitrogen gas, on the transition metal foil surfaces or in the electrolyte, despite rigorous drying. N and O cannot be distinguished by powder X-ray diffraction due to their similar electron numbers. EDX measurements have indicated that no additional elements are present. Coherent particles with sizes between 50 and 60 μm are shown in the SEM image (Fig. 2), which is in qualitative agreement with the sharp reflections observed in PXRD.

Unit cell parameters, residual values and structural data of ε-TaN from the Rietveld refinement (MoKα1) with Ta(1) located at Wyckoff site 1a (0,0,0), Ta(2) at 2d (1/3,2/3,1/2) and N at 3f (x,0,0), and of δ-TaN0.8 with Ta located at Wyckoff site 1a (0,0,0) and N at 1d (1/3, 2/3, 1/2).

| Parameter | ε-TaN | δ-TaN0.8 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Crystal system | Hexagonal | Hexagonal | |

| Space group | P6̅2m | P6̅m2 | |

| a/pm | 519.537(4) | 293.77(8) | |

| c/pm | 291.021(3) | 288.2(1) | |

| V/106 pm3 | 68.028 | 21.541 | |

| Dx/g cm−3 | 14.28 | 14.82 | |

| Rp/% | 3.32 | ||

| Rwp/% | 4.44 | ||

| χ | 1.29 | ||

| x(N) | 0.393(2) |

SEM image of ε-TaN.

As reported earlier, ε-TaN represents a high-temperature stable material: a thermogravimetric measurement of TaN0.81(1)O0.13(2)H0.014(1) in Ar atmosphere with a heating rate of 5 K min−1 showed no weight loss until 1000°C and no change of the PXRD pattern before and after this heat treatment.

3.2 Electrochemical synthesis of δ-NbN

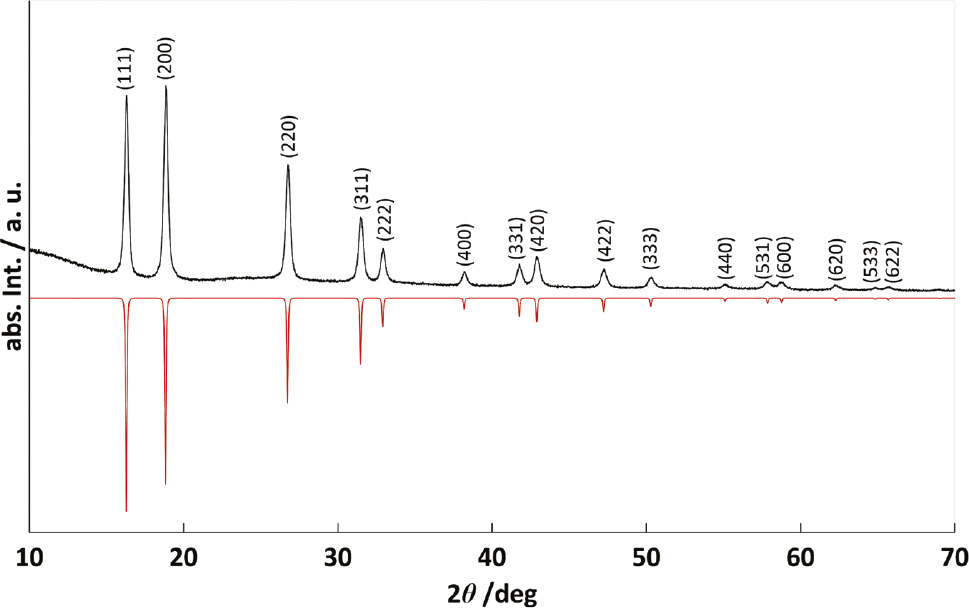

Figure 3 shows the PXRD pattern of black microcrystalline δ-NbN obtained after the anodic nitridation of niobium foil at a voltage of 2.2 V and at T=450°C in a molten salt system.

Observed PXRD pattern of δ-NbN (upwards, MoKα1) and simulated pattern from crystal structure data (downwards).

Because of the broad peak shape of the reflections Rietveld refinements of the structure and composition were not possible, but the lattice parameter of the cubic rocksalt-type phase could be determined to a=436.98(2) pm. Reported lattice parameters of the δ-NbN phase are near 439.2 pm for stoichiometric NbN, while the value for N-deficient NbN0.86 may be as low as 438.2 pm and for Nb-defective Nb0.94N even reach 437.6 pm [67]. We note that the lattice parameter obtained in this study is even lower. A comparison between the observed and the simulated PXRD pattern indicates the product to be single phase. In an EDX measurement no additional elements heavier than sodium were detected. Elemental analyses on N, O and H gave a composition of NbN1.17(2)O0.28(1)H0.01(1) translating into Nb0.69(N,O). This composition explains the smaller unit cell parameter, which is due to severe Nb deficiency, or in other words due to a high nitride – and oxide – content, concomitant to partial substitution of larger nitride by smaller oxide ions. Again, the comparably high oxygen content is probably due to impurities within the reactor system.

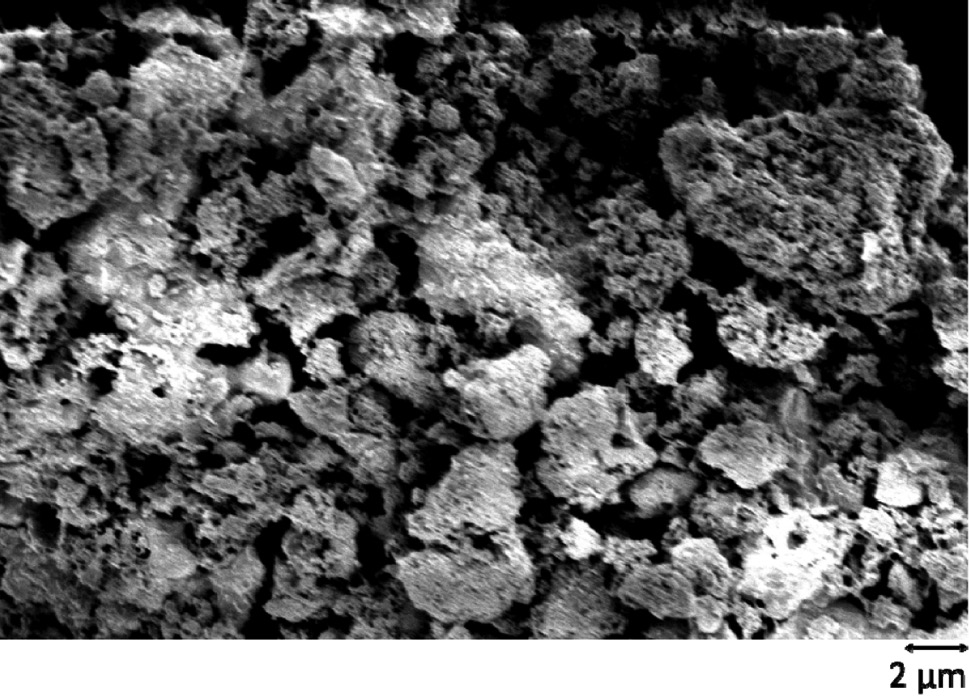

The SEM image (Fig. 4) of the obtained δ-NbN product reveals particles with sizes between 5 and 7 μm, but the surface morphology already indicates that these particles consist of smaller grains, in agreement with the broadened reflections in the PXRD pattern. Particle sizes calculated by the Scherrer equation [68] are around 130 nm.

SEM image of δ-NbN.

A TG measurement of δ-Nb0.69(N,O)=NbN1.17O0.28 up to 1000°C in Ar atmosphere has revealed a total mass loss of 2.3% (Fig. 5) occurring in three distinct steps. Assuming a loss of exclusively nitrogen up to 700°C, the resulting composition after the second step is calculated to NbN1.11O0.28. The final step is not completed up to T=1000°C. The mass loss leads to an overall composition of NbN0.98O0.28, however, a PXRD measurement of the product has shown two phases: one phase can be associated with NbO2. In experiments described in the literature, the reaction of Nb2O5 with NH3 at T=700°C resulted in δ-niobium oxide nitride, which appears to be the most stable phase between 600 and 800°C. In the temperature range of 800 and 850°C this niobium oxide nitride was shown to be no longer stable and to decompose into NbO2 and a second phase [69]. The second phase has a cubic lattice parameter of a=438.67 pm, which is close to the reported unit cell of δ-NbN1.025 [67], but this comparison might be ambiguous due to an unknown minor oxygen content possibly still present in this phase. No further mass change was observed upon cooling the sample after reaching T=1000°C.

TG measurement of δ-NbN in Ar atmosphere, with a rate of 5 K min−1 for heating (black) and cooling (red).

3.3 Electrochemical synthesis of γ′-Mo2N

During the anodic nitridation of a molybdenum foil at a voltage of 2.8 V and an operation temperature of 450°C in salt melt, γ′-Mo2N was electrochemically produced as a black material, which precipitated at the bottom of the crucible.

The results of powder X-ray diffraction (Fig. 6) suggest a single phase cubic rocksalt-type compound. Rietveld refinements were not possible because of the broad peak shape of the reflections. Compared to ε-TaN and δ-NbN, γ′-Mo2N has the smallest particle size in the range of 2–7 μm according to the SEM image (Fig. 7). However, the broad reflection profiles in PXRD indicate far smaller grains. Calculations with the Scherrer equation [68] resulted in particle sizes around 70 nm. The lattice parameter of the γ′ phase was determined to a=417.25(2) pm. This value is again significantly larger than a=416.13(1) pm found for a sample with nearly exact composition Mo2N according to neutron diffraction, however, reported values in the literature cover a broad range of 412–430 pm, indicative of a significant homogeneity range [52], [59], [70]. No further elements were observed by EDX analysis. Bulk elemental analysis on N, O and H gave a composition of MoN0.88(1)O0.11(1)H0.060(5), i.e. Mo2N1.76O0.22 close to Mo(N,O) with again a rather high oxygen content. γ′-Mo2N is described as rocksalt-type phase with an extremely high degree of randomly unoccupied nitrogen positions. Notably, upon heating of MoO3 in a stream of NH3 at T=700°C a molybdenum oxide nitride Mo2O1−xNx intermediate with a face-centered cubic structure und a lattice parameter of 416.8 pm was observed, which finally was converted into γ′-Mo2N [70], [71].

Observed PXRD pattern of γ′-Mo2N (upwards, MoKα1) and simulated pattern from crystal structure data (downwards).

SEM image of γ′-Mo2N.

The results of a TG measurement of γ′-Mo2N1.76O0.22 in argon atmosphere are shown in Fig. 8. The nitride decomposes between 100 and 1000°C with liberation of nitrogen gas and a total mass loss of 9.3%. The mass loss of 5.2% in the first step appears to be due to the transformation of γ′-Mo2N1.76O0.22 into γ′-Mo2N, probably retaining the oxygen content and forming Mo2(N0.94O0.22). According to its PXRD pattern this phase crystallizes cubically with a lattice parameter of a=414.99(2) pm. Mo2(N1.02O0.22) decomposes between 700 and 800°C with a mass loss of 3.5%. After the second step three phases were observed in PXRD: the main phase is represented by γ′-Mo2N with an again enlarged lattice parameter of a=416.66 pm, indicative of segregation of the oxide into a second solid phase, next to MoO2 and a small amount of Mo. The third step is not completed up to the maximum temperature of 1000°C. The final product consists of Mo, MoO2 and tetragonal β-Mo2N according to PXRD. Rietveld refinement of this product was not possible because of the even further increased broad shape of the reflections of the molybdenum nitride. It has been previously reported that γ′-Mo2N-samples lose nitrogen and oxygen at 800°C, and at 900°C there is a complete elimination of oxygen from the nitrided products [71].

TG measurement of γ′-Mo2N1.76O0.22 in Ar atmosphere, heating rate 5 K min−1.

4 Conclusion

In summary, anodic electrochemical synthesis of ε-TaN, δ-NbN and γ′-Mo2N is possible by reaction of the respective metal foils with nitrogen gas in a salt melt. This method of preparation can be carried out at significantly lower temperatures in comparison to those required for reacting metal powders directly with N2 or NH3, which typically proceeds at temperatures well above T=977°C [18], [42]. As we have earlier observed for binary iron nitride phases as well as ternary intermetallic nitrides [5], [6], the products are rather rich in nitrogen, typically at the thermodynamic upper limit of the corresponding nitrogen-rich homogeneity range of the phases, or even beyond. However, in contrast to phases where no oxide nitrides are known in the systems, the oxyphilic refractory transition metals used in this study for nitride formation are highly susceptive for uptake of oxygen impurities present in the system, e.g. at the surfaces of the applied electrodes, and as impurities in the electrolyte and the feed nitrogen gas at the cathode, and form oxide nitride phases with significant substitution of nitride by oxide ions. Thus, the electrochemical synthesis technique in future needs considerable improvement in order to produce pure nitrides, and work in this direction has just been started in our group.

Professor Arndt Simon on the occasion of his 80th birthday.

Acknowledgement

We thank William Clark for performing the TG measurements and Martin Schweizer for the generation of the SEM images.

References

[1] P. Höhn, R. Niewa, in Handbook of Solid State Chemistry, Vol. 1: Materials and Structure of Solids (Eds.: R. Dronskowski, S. Kikkawa, A. Stein), Wiley-VCH, Weinheim, Deutschland, 2017, pp. 251. ISBN 978-3-527-32587–0.Search in Google Scholar

[2] H. O. Pierson, Handbook of Refractory Carbides and Nitrides. Properties, Characteristics, Processing and Applications, Noyes Publications, Westwood, New Jersey, 1996.10.1016/B978-081551392-6.50017-9Search in Google Scholar

[3] R. Niewa, F. J. DiSalvo, Chem. Mater.1998, 10, 2733–2752.10.1021/cm980137cSearch in Google Scholar

[4] R. Niewa, H. Jacobs, Chem. Rev.1996, 96, 2053–2062.10.1021/cr9405157Search in Google Scholar

[5] T. S. Lehmann, B. Blaschkowski, R. Niewa, Eur. J. Inorg. Chem.2019, 1709–1713.10.1002/ejic.201900013Search in Google Scholar

[6] T. S. Lehmann, R. Niewa, Eur. J. Inorg. Chem.2019, 730–734.10.1002/ejic.201801294Search in Google Scholar

[7] T. Goto, T. Iwaki, Y. Ito, Electrochim. Acta2005, 50, 1283–1288.10.1016/j.electacta.2004.08.018Search in Google Scholar

[8] K. E. Waldrip, J. Y. Tsao, T. M. Kerly, Molten Salt-Based Growth of Bulk GaN and InN for Substrates, US Patent 7, 435, 297 B1, Oct. 14, 2008.Search in Google Scholar

[9] T. Goto, M. Tada, Y. Ito, Electrochim. Acta1994, 39, 1107–1113.10.1016/0013-4686(94)E0024-TSearch in Google Scholar

[10] H. Tsujimura, T. Goto, Y. Ito, Electrochim. Acta2002, 47, 2725–2731.10.1016/S0013-4686(02)00137-8Search in Google Scholar

[11] H. Tsujimura, T. Goto, Y. Ito, J. Electrochem. Soc.2004, 151, D73–D77.10.1149/1.1779334Search in Google Scholar

[12] H. Tsujimura, T. Goto, Y. Ito, J. Alloys Compd.2004, 376, 246–250.10.1016/j.jallcom.2003.12.042Search in Google Scholar

[13] T. Goto, K. Toyoura, H. Tsujimura, Y. Ito, Mater. Sci. Eng.2004, A380, 41–45.10.1016/j.msea.2004.03.054Search in Google Scholar

[14] T. Goto, H. Ishigaki, Y. Ito, Mater. Sci. Eng. A2004, 371, 353–358.10.1016/j.msea.2003.12.054Search in Google Scholar

[15] T. Goto, Y. Ito, J. Phys. Chem. Solids2005, 66, 418–421.10.1016/j.jpcs.2004.06.088Search in Google Scholar

[16] N. E. Brese, M. O’Keffe, P. Rauch, F. J. DiSalvo, Acta Crystallogr.1991, C47, 2291–2294.10.1107/S0108270191005231Search in Google Scholar

[17] A. Y. Ganin, L. Kienle, G. V. Vajenine, Eur. J. Inorg. Chem.2004, 3233–3239.10.1002/ejic.200400227Search in Google Scholar

[18] N. Terao, Jpn. J. Appl. Phys.1971, 10, 249–259.10.1143/JJAP.10.248Search in Google Scholar

[19] N. Schönberg, Acta Chem. Scand.1954, 8, 199–203.10.3891/acta.chem.scand.08-0199Search in Google Scholar

[20] G. Brauer, K. H. Zapp, Z. Anorg. Allg. Chem.1954, 277, 129–139.10.1002/zaac.19542770304Search in Google Scholar

[21] A. N. Christensen, B. Lebech, Acta Crystallogr.1978, B34, 261–263.10.1107/S0567740878002733Search in Google Scholar

[22] J. Gatterer, G. Dufek, P. Ettmayer, R. Kiefer, Monatsh. Chem.1975, 106, 1137–1147.10.1007/BF00906226Search in Google Scholar

[23] T. Mashimo, S. Tashiro, T. Toya, H. Yamazaki, S. Yamaya, K. Oh-ishi, Y. Syono, J. Mater. Sci.1993, 28, 3439–3443.10.1007/BF01159819Search in Google Scholar

[24] G. Brauer, E. Mohr, A. Neuhaus, A. Skogan, Monatsh. Chem.1972, 103, 794–798.10.1007/BF00905439Search in Google Scholar

[25] T. Mashimo, S. Tashiro, J. Mater. Sci. Lett.1994, 13, 174–176.10.1007/BF00278152Search in Google Scholar

[26] L. E. Conroy, A. N. Christensen, J. Solid State Chem.1977, 20, 205–207.10.1016/0022-4596(77)90069-XSearch in Google Scholar

[27] N. Christensen, Acta Crystallogr.1978, B34, 261–263.10.1107/S0567740878002733Search in Google Scholar

[28] L. Shi, Z. Yang, L. Chen, Y. Qian, Solid State Commun.2005, 133, 17–120.10.1016/j.ssc.2004.10.004Search in Google Scholar

[29] C. Taviot-Guého, J. Cellier, A. Bousquet, E. Tomasella, J. Phys. Chem. C2015, 119, 23559–23571.10.1021/acs.jpcc.5b07373Search in Google Scholar

[30] N. Schönberg, Acta Chem. Scand.1954, 8, 620–623.10.3891/acta.chem.scand.08-0620Search in Google Scholar

[31] G. Brauer, J. Weidlein, J. Strähle, Z. Anorg. Allg. Chem.1966, 348, 298–308.10.1002/zaac.19663480511Search in Google Scholar

[32] G. Brauer, J. Weidlein, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl.1965, 4, 875.10.1002/anie.196508751Search in Google Scholar

[33] Y. A. Buslaev, M. A. Glushkova, M. M. Ershova, E. M. Shustorovich, Neorg. Mater.1966, 2, 2120–2123.Search in Google Scholar

[34] M.-W. Lumey, R. Dronskowski, Z. Anorg. Allg. Chem.2003, 629, 2173–2179.10.1002/zaac.200300198Search in Google Scholar

[35] H. Schillig, A. Stork, E. Irran, H. Wolff, T. Bredow, R. Dronskowski, M. Lerch, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed.2007, 46, 2931–2934.10.1002/anie.200604351Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[36] R. Sanjines, M. Benkahoul, M. Papagno, F. Levy, D. Music, J. Appl. Phys.2006, 99, 044911.10.1063/1.2173039Search in Google Scholar

[37] R. Scholder, Gmelins Handbuch der anorganischen Chemie, Niob, Teil B1, Vol. 8 (Ed.: R. J. Meyer), Verlag Chemie, Weinheim, 1970, pp. 91–127.Search in Google Scholar

[38] G. M. Demyashev, V. R. Tregulov, R. K. Chuzhko, J. Cryst. Growth1983, 63, 135–144.10.1016/0022-0248(83)90438-4Search in Google Scholar

[39] V. Buscaglia, F. Caracciolo, M. Ferretti, M. Minguzzi, R. Musenich, J. Alloys Compd.1998, 266, 201–206.10.1016/S0925-8388(97)00482-9Search in Google Scholar

[40] W. Lengauer, M. Bohn, Acta Mater.2000, 48, 2633–2638.10.1016/S1359-6454(00)00056-2Search in Google Scholar

[41] Y. Zou, X. Wang, T. Chen, X. Li, X. Qi, D. Welch, P. Zhu, B. Liu, T. Cui, B. Li, Sci. Rep.2015, 5, 1–11.10.1038/srep10811Search in Google Scholar

[42] G. Brauer, J. Jander, Z. Anorg. Allg. Chem.1952, 270, 160–178.10.1002/zaac.19522700114Search in Google Scholar

[43] Y. Kurokawa, T. Ishizaka, J. Mater. Sci.2001, 36, 301–306.10.1023/A:1004847722451Search in Google Scholar

[44] M. Weishaupt, J. Strähle, Z. Anorg. Allg. Chem.1977, 429, 261–269.10.1002/zaac.19774290132Search in Google Scholar

[45] R. Marchand, F. Tessier, F. J. DiSalvo, J. Mater. Chem.1999, 9, 297–304.10.1039/a805315dSearch in Google Scholar

[46] C. L. Bull, P. F. McMillan, E. Soignard, K. J. Leinenweber, J. Solid State Chem.2004, 177, 1488–1492.10.1016/j.jssc.2003.11.033Search in Google Scholar

[47] H. Ihara, Y. Kimura, K. Senzaki, H. Zezuka, M. Hirabayashi, Phys. Rev. B1985, 31, 3177–3178.10.1103/PhysRevB.31.3177Search in Google Scholar

[48] K. Saito, Y. Asada, J. Phys. F: Met. Phys.1987, 17, 2273–2283.10.1088/0305-4608/17/11/016Search in Google Scholar

[49] A. Y. Ganin, L. Kienle, G. V. Vajenine, J. Solid State Chem.2006, 179, 2339–2348.10.1016/j.jssc.2006.05.025Search in Google Scholar

[50] B. T. Matthias, J. K. Hulm, Phys. Rev.1952, 87, 799–806.10.1103/PhysRev.87.799Search in Google Scholar

[51] C. L. Bull, P. F. McMillan, E. Soignard, K. Leinenweber, J. Solid State Chem.2004, 177, 1488–1492.10.1016/j.jssc.2003.11.033Search in Google Scholar

[52] C. L. Bull, T. Kawashima, P. F. McMillan, D. Machon, O. Shebanova, D. Daisenberger, E. Soignard, E. T. Muromachi, L. C. Chapon, J. Solid State Chem.2006, 179, 1762–1767.10.1016/j.jssc.2006.03.011Search in Google Scholar

[53] P. Ettmayer, Monatsh. Chem.1970, 101, 127–140.10.1007/BF00907533Search in Google Scholar

[54] U. S. Ozkan, L. Zhang, P. A. Clark, J. Catal.1997, 172, 294–306.10.1006/jcat.1997.1873Search in Google Scholar

[55] J. L. O’Loughlin, C. H. Wallace, M. S. Knox, R. B. Kaner, Inorg. Chem.2001, 40, 2240–2245.10.1021/ic001265hSearch in Google Scholar PubMed

[56] K. Inumaru, K. Baba, S. Yamanaka, Chem. Mater.2005, 17, 5935–5940.10.1021/cm050708iSearch in Google Scholar

[57] B. Mazumder, A. L. Hector, J. Mater. Chem.2009, 19, 4673–4686.10.1039/b817407eSearch in Google Scholar

[58] A. Gomathi, A. Sundaresan, C. N. R. Rao, J. Solid State Chem.2007, 180, 291–295.10.1016/j.jssc.2006.10.020Search in Google Scholar

[59] X. Zheng, H. Wang, X. Yu, J. Feng, X. Shen, S. Zhang, R. Yang, X. Zhou, Y. Xu, R. Yu, H. Xiang, Z. Hu, C. Jin, R. Zhang, S. Wei, J. Han, Y. Zhao, Hui Li, S. Wang, Appl. Phys. Lett.2018, 113, 221901-1–221901-5 and references given therein.10.1063/1.5048540Search in Google Scholar

[60] L. Cunha, L. Rebouta, F. Vaz, M. Staszuk, S. Malra, J. Barbosa, P. Carvalho, E. Alves, E. Le Bourhis, Ph. Goudeau, J. P. Rivière, Vacuum2008, 82, 1428–1432.10.1016/j.vacuum.2008.03.015Search in Google Scholar

[61] S. Kühn, P. Schmidt-Zhang, A. H. P. Hahn, M. Huber, M. Lerch, T. Ressler, Chem. Cent. J.2010, 5, 1–10.10.1186/1752-153X-5-42Search in Google Scholar

[62] J. Rodriguez-Carvajal, Physica B1993, 192, 55–69.10.1016/0921-4526(93)90108-ISearch in Google Scholar

[63] W. Sundermeyer, Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. Engl.1965, 4, 222–238, and references within.10.1002/anie.196502221Search in Google Scholar

[64] T. Goto, Y. Ito, Electrochim. Acta1998, 43, 3379–3384.10.1016/S0013-4686(98)00010-3Search in Google Scholar

[65] R. D. Shannon, Acta Crystallogr.1976, A32, 751–767.10.1107/S0567739476001551Search in Google Scholar

[66] W. H. Baur, Crystallogr. Rev.1987, 1, 59–83.10.1080/08893118708081679Search in Google Scholar

[67] G. Brauer, H. Kirner, Z. Anorg. Allg. Chem.1964, 329, 34–43.10.1002/zaac.19643280105Search in Google Scholar

[68] U. Holzwarth, N. Gibson, Nat. Nanotechnol.2011, 6, 534.10.1038/nnano.2011.145Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[69] R. A. Guidotti, D. G. Kesterke, Met. Trans.1973, 4, 1233–1237.10.1007/BF02644516Search in Google Scholar

[70] I. Jauberteau, A. Bessaudou, R. Mayet, J. Cornette, J. L. Jauberteau, P. Carles, T. Merle-Méjean, Coatings2015, 5, 656–687.10.3390/coatings5040656Search in Google Scholar

[71] M. D. Lyutaya, Academy of Science of the Ukraine; translated from Poroshk. Metall. (Kiev)1979, 195, 60–66.Search in Google Scholar

©2020 Walter de Gruyter GmbH, Berlin/Boston

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- In this Issue

- Laudatio/Preface

- Arndt Simon zum 80. Geburtstag gewidmet

- Research Articles

- High-temperature superconductors: underlying physics and applications

- Chemical resistance and chemical capacitance

- Investigations of the optical and electronic effects of silicon and indium co-doping on ZnO thin films deposited by spray pyrolysis

- Electrochemical synthesis of transition metal oxide nitrides with ε-TaN, δ-NbN and γ′-Mo2N structure type in a molten salt system

- Preferred selenium incorporation and unexpected interlayer bonding in the layered structure of Sb2Te3−xSex

- BOX A-type monopyrrolic heterocycles modified via the Suzuki-Miyaura cross-coupling reaction

- Cooperative activation of azides by an Al/N-based active Lewis pair – unexpected insertion of nitrogen atoms into C–Si bonds and formation of AlCN3 heterocycles

- Squares of gold atoms and linear infinite chains of Cd atoms as building units in the intermetallic phases REAu4Cd2 (RE=La–Nd, Sm) with YbAl4Mo2-type structure

- Synthesis and characterization of K5Sn2OF11

- Li vs. Zn substitution in Li17Si4 – Li17–ε–δZnεSi4 connecting the structures of Li21Si5 and Li17Si4

- Cs2Zn(CN)4: a first example of a non-cyano spinel of composition A2M(CN)4 with A=alkali metal and M=group 12 metal

- Magnetic and electronic properties of CaFeO2Cl

- A spatially separated [KBr6]5− anion in the cyanido-bridged uranium(IV) compound [U2(CN)3(NH3)14]5+[KBr6]5−·NH3

- Crystal structures of the tetrachloridoaluminates(III) of rubidium(I), silver(I), and lead(II)

- A new theoretical model for hexagonal ice, Ih(d), from first principles investigations

- Structural characterization and Raman spectrum of Cs[OCN]

- New cation-disordered quaternary selenides Tl2Ga2TtSe6 (Tt=Ge, Sn)

- The UV-phosphor strontium fluorooxoborate Sr[B5O7F3]:Eu

- Extending the knowledge on the quaternary rare earth nickel aluminum germanides of the RENiAl4Ge2 series (RE=Y, Sm, Gd–Tm, Lu) – structural, magnetic and NMR-spectroscopic investigations

- Structural diversity in Cd(NCS)2-3-cyanopyridine coordination compounds: synthesis, crystal structures and thermal properties

- Cation-anion pairs of niobium clusters of the type [Nb6Cl12(RCN)6][Nb6Cl18] (R=Et, nPr, iPr) with nitrile ligands RCN forming stabilizing inter-ionic contacts

- “Flat/steep band model” for superconductors containing Bi square nets

- La- and Lu-agardite – preparation, crystal structure, vibrational and magnetic properties

- A series of new layered lithium europium(II) oxoniobates(V) and -tantalates(V)

- The untypical high-pressure Zintl phase SrGe6

- A new ternary silicide GdFe1−xSi2 (x=0.32): preparation, crystal and electronic structure

- Lanthanide orthothiophosphates revisited: single-crystal X-ray, Raman, and DFT studies of TmPS4 and YbPS4

- A hexaniobate expanded by six [Hg(cyclam)]2+ complexes via Hg–O bonds yields a positively charged polyoxoniobate cluster

- Preliminary communication

- A hexaniobate expanded by six [Hg(cyclam)]2+ complexes via Hg–O bonds yields a positively charged polyoxoniobate cluster

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- In this Issue

- Laudatio/Preface

- Arndt Simon zum 80. Geburtstag gewidmet

- Research Articles

- High-temperature superconductors: underlying physics and applications

- Chemical resistance and chemical capacitance

- Investigations of the optical and electronic effects of silicon and indium co-doping on ZnO thin films deposited by spray pyrolysis

- Electrochemical synthesis of transition metal oxide nitrides with ε-TaN, δ-NbN and γ′-Mo2N structure type in a molten salt system

- Preferred selenium incorporation and unexpected interlayer bonding in the layered structure of Sb2Te3−xSex

- BOX A-type monopyrrolic heterocycles modified via the Suzuki-Miyaura cross-coupling reaction

- Cooperative activation of azides by an Al/N-based active Lewis pair – unexpected insertion of nitrogen atoms into C–Si bonds and formation of AlCN3 heterocycles

- Squares of gold atoms and linear infinite chains of Cd atoms as building units in the intermetallic phases REAu4Cd2 (RE=La–Nd, Sm) with YbAl4Mo2-type structure

- Synthesis and characterization of K5Sn2OF11

- Li vs. Zn substitution in Li17Si4 – Li17–ε–δZnεSi4 connecting the structures of Li21Si5 and Li17Si4

- Cs2Zn(CN)4: a first example of a non-cyano spinel of composition A2M(CN)4 with A=alkali metal and M=group 12 metal

- Magnetic and electronic properties of CaFeO2Cl

- A spatially separated [KBr6]5− anion in the cyanido-bridged uranium(IV) compound [U2(CN)3(NH3)14]5+[KBr6]5−·NH3

- Crystal structures of the tetrachloridoaluminates(III) of rubidium(I), silver(I), and lead(II)

- A new theoretical model for hexagonal ice, Ih(d), from first principles investigations

- Structural characterization and Raman spectrum of Cs[OCN]

- New cation-disordered quaternary selenides Tl2Ga2TtSe6 (Tt=Ge, Sn)

- The UV-phosphor strontium fluorooxoborate Sr[B5O7F3]:Eu

- Extending the knowledge on the quaternary rare earth nickel aluminum germanides of the RENiAl4Ge2 series (RE=Y, Sm, Gd–Tm, Lu) – structural, magnetic and NMR-spectroscopic investigations

- Structural diversity in Cd(NCS)2-3-cyanopyridine coordination compounds: synthesis, crystal structures and thermal properties

- Cation-anion pairs of niobium clusters of the type [Nb6Cl12(RCN)6][Nb6Cl18] (R=Et, nPr, iPr) with nitrile ligands RCN forming stabilizing inter-ionic contacts

- “Flat/steep band model” for superconductors containing Bi square nets

- La- and Lu-agardite – preparation, crystal structure, vibrational and magnetic properties

- A series of new layered lithium europium(II) oxoniobates(V) and -tantalates(V)

- The untypical high-pressure Zintl phase SrGe6

- A new ternary silicide GdFe1−xSi2 (x=0.32): preparation, crystal and electronic structure

- Lanthanide orthothiophosphates revisited: single-crystal X-ray, Raman, and DFT studies of TmPS4 and YbPS4

- A hexaniobate expanded by six [Hg(cyclam)]2+ complexes via Hg–O bonds yields a positively charged polyoxoniobate cluster

- Preliminary communication

- A hexaniobate expanded by six [Hg(cyclam)]2+ complexes via Hg–O bonds yields a positively charged polyoxoniobate cluster