Abstract

Reaction of [Me4N]2[Cd(TeTol)4] (Tol = 4-tolyl) with two equivalents of [Cu(PPh3)2NO3] gave a new soluble tellurolate-bridged heterobimetallic complex of [Cd(μ-TeTol)4{Cu(PPh3)2}2] (1) in which two [Cu(PPh3)2]+ fragments are chelated at opposite edges of a tetrahedral [Cd(TeTol)4]2– moiety via the tellurium atoms. Complex 1 is air and optically stable. The nonlinear optical absorption (α2 = 7.4 × 10–4 cm W–1 mol–1) and refraction (n2 = 2.3 × 10–9 cm2 W–1 mol–1) were determined by z-scan techniques with 7 ns pulses at 532 nm.

1 Introduction

The chemistry of transition metal tellurolate complexes continues to attract considerable attention due to their potential utility as single-source precursor for semiconducting binary- and ternary-phase materials [1–3]. Despite the surge in the development of this area of chemistry, the synthesis and structural characterization of metal-tellurium complexes remain underdeveloped relative to their selenium congeners [4]. Until recently, use of tellurium ligands has still been neglected in transition metal chemistry compared with the corresponding sulfur and, to a lesser extent, selenium derivative [5]. The difficulty in the synthesis of metal-tellurium complexes is due to the relatively low solubility, which has led to limitations of their isolation and structure determination. Fenske and coworkers have successfully probed the use of the bis-silylated tellurium reagent Te(SiMe3)2, the mono-silylated phenyl-tellurium reagent PhTeSiMe3, and other aryl-/alkyl-tellurolate ligands as an effective route to achieve high nuclearity phosphane-stablized copper-, silver- and cadmium-telluride clusters [6–11]. Similarly, Corrigan and coworkers have reported that the design of metal-tellurolate complexes using highly reactive Te(SiMe3)2 or RTeSiMe3 (R = n-Bu, Ph) offers a powerful entry into high nuclearity ternary cluster and nanocluster materials [12, 13]. Compared with the binary metal tellurides, ternary metal telluride complexes are very scarce [4, 5]. We have previously reported two ternary tellurolate clusters [CdM4(μ-TePh)3(μ3-TePh)3(PPh3)4] (M = Cu, Ag) [14]. In order to develop new metal telluride materials and explore their nonlinear optical properties, we report a new soluble tellurolate-bridged heterobimetallic complex [Cd(μ-TeTol)4{Cu(PPh3)2}2] (Tol = 4-tolyl) in this paper.

2 Experimental section

2.1 General

All syntheses were performed in oven-dried glassware under a purified nitrogen atmosphere using standard Schlenk techniques. The solvents were purchased from Sinopharm Chemical Reagent Co., Ltd, Shanghai, China, purified by conventional methods and degassed prior to use. [Me4N]2[Cd(TeTol)4] [15] and [Cu(PPh3)2NO3] [16] were prepared using methods previously described in the literature. All elemental analyses were carried out using a Perkin-Elmer 2400 CHN analyzer (USA). Electronic absorption spectra were obtained on a Shimadzu UV-3000 spectrophotometer (Japan). Infrared spectra were recorded on a Digilab FTS-40 spectrophotometer (USA) with use of pressed KBr pellets. Positive FAB mass spectra were recorded on a Finnigan TSQ 7000 spectrometer (USA). NMR spectra were recorded on a Bruker ALX 300 spectrometer (Switzerland) operating at 300 and 121.5 MHz for 1H and 31P, respectively. Chemical shifts (δ, ppm) were reported with reference to SiMe4 (1H) and H3PO4 (31P).

2.2 Synthesis of [Cd(μ-TeTol)4{Cu(PPh3)2}2] (1)

To a solution of [Me4N]2[Cd(TeTol)4] (227 mg, 0.20 mmol) in DMF (8 mL) was added [Cu(PPh3)2NO3] (260 mg, 0.40 mmol) in CH2Cl2 (20 mL) with stirring. The resulting mixture was stirred at room temperature for 1 h and then filtered. The filtrate was layered with 15 mL of i-PrOH and allowed to stand at room temperature. Orange block crystals of 1 were obtained after 1 week. Yield: 290 mg (67 %). – Anal. for C100H88P4Te4CdCu2: calcd. C 55.51, H 4.10; found: C 55.13, H 4.04. – UV/Vis (DMF; 10–3ε, mol–1·cm–1): λmax = 274 (11.5), 361 (0.92) nm. – IR (KBr disc, cm–1): v= 1079 (s, P–C), 527 (m, C–Te), 319 (w, Cd–Te). – 1H NMR ([D6]DMSO, ppm): δ = 2.16 (s, 12H, CH3), 7.04 (d, 8H, J = 6.8 Hz, C6H4), 7.15 (d, 8H, J = 6.4 Hz, C6H4), 7.22–7.61 (m, 60H, Ph). – 31P NMR ([D6]DMSO, ppm): δ = –4.15 (s). – MS (FAB): m/z = 2163 [M]+.

2.3 X-Ray crystallography

Crystallographic data and experimental details for [Cd(μ-TeTol)4{Cu(PPh3)2}2] are summarized in Table 1. Intensity data were collected on a Bruker SMART APEX 2000 CCD diffractometer using graphite-monochromated MoKα radiation (λ = 0.71073 Å) at T = 296(2) K. The collected frames were processed with the software Saint [17]. The data were corrected for absorption using the program Sadabs [18]. The structure was solved by Direct Methods and refined by full-matrix least-squares on F2 using the shelxtl software package [19, 20]. All non-hydrogen atoms were refined anisotropically. The positions of all hydrogen atoms were generated geometrically (Csp3–H = 0.97 and Csp2–H = 0.93 Å), assigned isotropic displacement parameters, and allowed to ride on their respective parent carbon or nitrogen atoms before the final cycle of least-squares refinement. The Flack parameter value of –0.03(4) for 1 indicated that the correct enantiomorph had been selected in the structure refinement.

Crystallographic data and experimental details of the structure determination of [Cd(μ-TeTol)4{Cu(PPh3)2}2] (1).

| Empirical formula | C100H88P4Cu2CdTe4 |

| Formula weight | 2163.46 |

| Crystal system | tetragonal |

| Space group | P4̅21/c |

| a = b, Å | 15.5219(5) |

| c, Å | 18.6922(14) |

| V, Å3 | 4503.5(4) |

| Z | 2 |

| Dcalcd., g cm–3 | 1.60 |

| Temperature, K | 296(2) |

| F(000), e | 2124 |

| μ(MoKα), mm–1 | 2.1 |

| Refl. total/unique/Rint | 28126/5209/0.0509 |

| Ref. parameters | 252 |

| R1a/wR2b [I > 2 σ(I)] | 0.0477/0.1102 |

| R1/wR2 (all data) | 0.0924/0.1363 |

| Goodness-of-fit (GoF)c | 1.09 |

| Flack (x) parameter | –0.03(4) |

| Final max/min difference peaks, e Å–3 | +0.84/–0.71 |

aR1 = Σ||Fo|–|Fc||/Σ|Fo|; b

CCDC 914937 contains the supplementary crystallographic data for this paper. These data can be obtained free of charge from The Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre via www.ccdc.cam.ac.uk/data_request/cif.

2.4 Optical measurements

A 1.65 × 10–4 m DMF solution of [Cd(μ-TeTol)4{Cu(PPh3)2}2] was placed in a 1-mm quartz cuvette for optical measurements. The optical limiting characteristics, along with nonlinear absorption and refraction, were investigated with linearly polarized laser light (λ = 532 nm, pulse width = 7 ns) generated from a Q-switched and frequency-doubled Nd:YAG laser. The spatial profiles of the optical pulses were nearly Gaussian. The laser beam was focused with a 25-cm focal-length focusing mirror. The radius of the laser beam waist was measured to be 30 ± 5 μm (half-width at e–2 maximum in irradiance). The incident and transmitted pulse energy were measured simultaneously by two Laser Precision detectors (RjP-735 energy probes) communicating to a computer via an IEEE interface [21, 22], while the incident pulse energy was varied by a Newport Com. Attenuator. The interval between the laser pulses was chosen to be 10 s to avoid the influence of thermal and long-term effects. The details of the set-up can be found elsewhere [23, 24].

3 Results and discussion

Interaction of the tetratellurolato cadmium complex [Me4N]2[Cd(TeTol)4] with two equivalents of [Cu(PPh3)2NO3] afforded a trinuclear tellurolate-bridged heterobimetallic complex [Cd(μ-TeTol)4{Cu(PPh3)2}2] (1) in a yield of 67 %. As expected, two [Cu(PPh3)2]+ fragments bind at opposite edges of a tetrahedral [Cd(TeTol)4]2– moiety via the tellurium atoms. Although a similar structure has been observed previously for the sulfur and selenium analogs [25], the current arrangement appears to be the first example of a structurally characterized (see below) ternary linear complex with bridging tellurolate ligands. The 1H NMR spectrum for complex 1 is very similar to those of the free ligands, indicating that the complex is diamagnetic. The 31P{1H} NMR resonance for complex 1 shows a single peak downfield from that of the free PPh3 ligand, indicating phosphorus atoms with the same coordination environment. Characteristic bands for the telluro-phenolato complex 1 were found at 1079 and 527 cm–1 in its IR spectrum. The former band is assignable to the mode of phenyl ring coupled with the P–C bonds, and the latter band is due to the C–Te bonds [15]. The Cd–Te vibrations at 319 cm–1 as a relatively weak sharp peak can also be observed [15].

The structure of complex 1 was confirmed by an X-ray diffraction study. As shown in Fig. 1, the solid-state structure of 1 contains two symmetry-related {(Ph3P)2Cu(μ-TeTol)2} units, each having crystallographic two-fold symmetry, the 2 (C2) axis passing through the Cu atoms. The {(Ph3P)2Cu(μ-TeTol)2} units are linked by the common Cd atom, which resides on a crystallographic 4̅ (S4) axis. The high molecular symmetry, as imposed by crystallography, results inter alia in the equivalence of the four phosphorus atoms as confirmed by 31P NMR. The geometry around the central cadmium atom is distorted tetrahedron, indicated by the Te–Cd–Te bond angles ranging from 97.54(2) to 115.74(1)°. The average Cd–Te bond length of 2.8433(6) Å in 1 is slightly longer than that of 2.7684(8) Å in [CdCu4(μ-TePh)3(μ3-TePh)3(PPh3)4] [14]. The copper atoms in 1 have a distorted tetrahedron geometry, being bonded to two phosphorus atoms of the PPh3 ligands and two tellurium atoms of TolTe– ligands. The average Cu–Te bond length is 2.6790(9) Å and the average Cu–Te–Cd bond angle is 78.27(3)°. The three metal atoms are collinear. The Cu···Cd distances are 3.487 Å too long for any significant metal-metal interaction.

![Fig. 1: A perspective view of [Cd(μ-TeTol)4{Cu(PPh3)2}2] with the ellipsoids drawn at 35% probability level.](/document/doi/10.1515/znb-2015-0001/asset/graphic/znb-2015-0001_fig1.jpg)

A perspective view of [Cd(μ-TeTol)4{Cu(PPh3)2}2] with the ellipsoids drawn at 35% probability level.

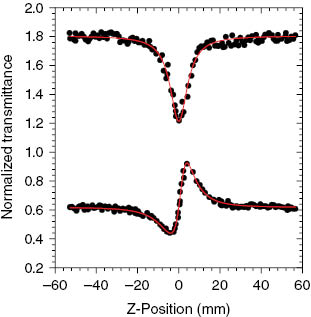

Different from the analogous colorless sulfur and selenium complexes [25, 26], complex 1 is orange and very stable in both solid state and solution. It has a weak absorbance at 532 nm, which may promise small intensity loss and temperature changes upon photon absorption when the laser pulse propagates in this heterobimetallic complex. The nonlinear optical properties of complex 1 were investigated using the z-scan technique [21–24]. The z-scan results without and with the aperture are given in Fig. 2 (up) and Fig. 2(down), respectively. To obtain the nonlinear optical parameters, we employed a z-scan theory that considers an effective nonlinearity of third-order nature. Both the absorption coefficient and the refractive index can be expressed as α = α0 + α2I and n = n0 + n2I, respectively, where α0 and α2 are the linear and nonlinear absorption coefficients; n0 and n2 are the linear and nonlinear refractive indices, respectively; and I is the irradiance of the laser beam within the sample. By applying the z-scan theory, the curves shown in Fig. 2 were numerically calculated to fit to the experimental data. The best fits were for α2 = 7.4 × 10–4 cm W–1 mol–1 and n2 = 2.3 × 10–9 cm2 W–1 mol–1. The nonlinear optical behavior of complex 1 is obviously better than those of the linear trinuclear heterobimetallic complexes [(μ-WSe4)(AgPPh3){Ag(PPh3)2] [27], [(μ-WSe4)(AgPCy3)2] [28], and [Cd(μ-SePh)4{M(PPh3)2}2] (M = Cu or Ag) [25], and comparable to those of cubane-like [(μ3-MoSe4)(MPPh3)3(μ3-Cl)] (M = Cu or Ag) [29].

Z-scan data of 1.65 × 10–4 m of 1 in DMF at 532 nm with Io being 1.17 × 1010 W m–2: the upper collected under the open aperture configuration showing nonlinear optical absorption; the lower obtained by dividing the normalized z-scan data obtained under the closed aperture configuration by the normalized z-scan data in the upper. The curves are theoretical fits based on z-scan theoretical calculations.

Meanwhile, the positive values of nonlinear refractions in 1 indicate that there are self-focusing effects in the nonlinear optical behavior. It is apparent that the nonlinear optical absorptive and refractive properties for linear heterometallic complexes as well as cubane-like clusters are highly sensitive to the heavy atom effect [30]. Moreover, the introduction of the semiconductor element tellurium into ternary metal complexes can effectively improve the nonlinear optical properties of metal telluride complexes [25, 26], which is one of the best routes to design this class of ternary tellurolate complexes as candidates for optical materials. More examples of metal tellurolate complexes will be synthesized for further investigation of the structure-property relationship.

Acknowledgments

This project was supported by the Natural Science Foundation of China under Project Number 90922008.

References

[1] J. Arnold, Prog. Inorg. Chem. 1995, 43, 353.Suche in Google Scholar

[2] W. Hirpo, S. Dhingra, A. C. Sutorik, M. G. Kanatzidis, J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1993, 115, 1597.Suche in Google Scholar

[3] J. J. Vittal, M. T. Ng, Acc. Chem. Res. 2006, 39, 869.Suche in Google Scholar

[4] M. W. DeGroot, M. W. Cockburn, M. S. Workentin, J. F. Corrigan, Inorg. Chem. 2001, 40, 4678.Suche in Google Scholar

[5] O. Bumbu, C. Ceamanos, O. Crespo, M. C. Gimeno, A. Laguna, C. Silvestru, M. D. Villacampa, Inorg. Chem. 2007, 46, 11460.Suche in Google Scholar

[6] J. F. Corrigan, D. Fenske, Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. Engl. 1997, 36, 1981.Suche in Google Scholar

[7] J. F. Corrigan, D. Fenske, W. P. Power, Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. Engl. 1997, 36, 1176.Suche in Google Scholar

[8] J. F. Corrigan, D. Fenske, Chem. Commun. 1997, 1837.10.1039/a704132bSuche in Google Scholar

[9] T. Langetepe, D. Fenske, Z. Anorg. Allg. Chem. 2001, 627, 820.Suche in Google Scholar

[10] X.-J. Wang, T. Langetepe, D. Fenske, B.-S. Kang, Z. Anorg. Allg. Chem. 2001, 627, 1158.Suche in Google Scholar

[11] A. Eichhöfer, A. Aharoni, U. Banin, Z. Anorg. Allg. Chem. 2002, 628, 2415.Suche in Google Scholar

[12] M. W. DeGroot, J. F. Corrigan, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2004, 43, 5355.Suche in Google Scholar

[13] M. W. DeGroot, N. J. Taylor, J. F. Corrigan, Inorg. Chem. 2005, 44, 5447.Suche in Google Scholar

[14] C. Xu, J. J. Zhang, Q. Chen, T. Duan, W. H. Leung, Q. F. Zhang, Inorg. Chem. Commun. 2012, 21, 1.Suche in Google Scholar

[15] N. Ueyama, T. Sugawara, K. Sasaki, A. Nakamura, S. Yamashita, Y. Wakatsuki, H. Yamazaki, N. Yasuoka, Inorg. Chem. 1988, 27, 741.Suche in Google Scholar

[16] G. J. Kubas, Inorg. Synth. 1996, 28, 68.Suche in Google Scholar

[17] smart and Saint+ for Windows NT (version 6.02a), Bruker Analytical X-ray Instruments Inc., Madison, Wisconsin (USA) 1998.Suche in Google Scholar

[18] G. M. Sheldrick, Sadabs, University of Göttingen, Göttingen (Germany), 1996.Suche in Google Scholar

[19] G. M. Sheldrick, shelxtl (version 5.1) Software Reference Manual, Bruker Analytical X-ray Instruments Inc., Madison, Wisconsin (USA), 1997.Suche in Google Scholar

[20] G. M. Sheldrick, Acta Crystallogr. 2008, A64, 112.Suche in Google Scholar

[21] M. Sheik-Bahae, A. A. Said, T. H. Wei, D. J. Hagan, E. W. Van Stryland, IEEE J. Quantum. Electron. 1990, 26, 760.Suche in Google Scholar

[22] M. Sheik-Bahae, A. A. Said, E. W. Van Stryland, Opt. Lett. 1989, 14, 955.Suche in Google Scholar

[23] T. Xia, A. Dogariu, K. Mansour, D. J. Hagan, A. A. Said, E. W. Van Stryland, S. Shi, J. Opt. Soc. Am. B 1998, 15, 1497.10.1364/JOSAB.15.001497Suche in Google Scholar

[24] H. W. Hou, B. Liang, X. Q. Xin, K. B. Yu, P. Ge, W. Ji, S. Shi, J. Chem. Soc., Faraday Trans. 1996, 92, 2343.Suche in Google Scholar

[25] C. Xu, J. J. Zhang, T. Duan, Q. Chen, W. H. Leung, Q. F. Zhang, Polyhedron 2012, 33, 185.10.1016/j.poly.2011.11.046Suche in Google Scholar

[26] C. Xu, J. J. Zhang, T. Duan, Q. Chen, W. H. Leung, Q. F. Zhang, J. Cluster Sci. 2010, 21, 813.Suche in Google Scholar

[27] Q. F. Zhang, W. H. Leung, Y. L. Song, M. C. Hong, C. H. L. Kennard, X. Q. Xin, New. J. Chem. 2001, 25, 465.Suche in Google Scholar

[28] Q. F. Zhang, J. Ding, Z. Yu, Y. Song, A. Rothenberger, D. Fenske, W. H. Leung, Inorg. Chem. 2006, 45, 8638.Suche in Google Scholar

[29] Q. F. Zhang, Y. N. Xiong, T. S. Lai, W. Ji, X. Q. Xin, J. Phys. Chem. B 2000, 104, 3446.10.1021/jp992782sSuche in Google Scholar

[30] S. Shi, Z. Lin, Y. Mo, X. Q. Xin, J. Phys. Chem. B 1996, 100, 10696.Suche in Google Scholar

©2015 by De Gruyter

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Frontmatter

- In this Issue

- Review

- Cerium intermetallics with ZrNiAl-type structure – a review

- Original Communications

- In vitro cytotoxicity of hydrazones, pyrazoles, pyrazolo-pyrimidines, and pyrazolo-pyridine synthesized from 6-substituted 3-formylchromones

- A supramolecular 3-D organic-inorganic hybrid structure based on {PMo12} layers arranged in an alternating mode

- Ionic binuclear ferrocenyl compounds containing 1,1,3,3-tetracyanopropenide anions – synthesis, structural characterization and catalytic effects on thermal decomposition of main components of solid propellants

- Zur Chemie der 1,3,5-Triaza-2-phosphorinan- 4,6-dione. Teil XIV. Darstellung von weiteren P-alkyl- und P-arylsubstituierten 1,3,5-Trimethyl-1,3,5-triaza-2-phosphorinan-4,6-dionen

- Synthesis, biological activity and modeling study of some thiopyrimidine derivatives and their platinum(II) and ruthenium(III) metal complexes

- Synthesis of functionalized benzene using Diels–Alder reaction of activated acetylenes with synthesized phosphoryl-2-oxo-2H-pyran

- Synthesis, structure, and optical nonlinearity of soluble ternary cadmium copper tellurolate complex [Cd(μ-TeTol)4{Cu(PPh3)2}2] (Tol = 4-tolyl)

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Frontmatter

- In this Issue

- Review

- Cerium intermetallics with ZrNiAl-type structure – a review

- Original Communications

- In vitro cytotoxicity of hydrazones, pyrazoles, pyrazolo-pyrimidines, and pyrazolo-pyridine synthesized from 6-substituted 3-formylchromones

- A supramolecular 3-D organic-inorganic hybrid structure based on {PMo12} layers arranged in an alternating mode

- Ionic binuclear ferrocenyl compounds containing 1,1,3,3-tetracyanopropenide anions – synthesis, structural characterization and catalytic effects on thermal decomposition of main components of solid propellants

- Zur Chemie der 1,3,5-Triaza-2-phosphorinan- 4,6-dione. Teil XIV. Darstellung von weiteren P-alkyl- und P-arylsubstituierten 1,3,5-Trimethyl-1,3,5-triaza-2-phosphorinan-4,6-dionen

- Synthesis, biological activity and modeling study of some thiopyrimidine derivatives and their platinum(II) and ruthenium(III) metal complexes

- Synthesis of functionalized benzene using Diels–Alder reaction of activated acetylenes with synthesized phosphoryl-2-oxo-2H-pyran

- Synthesis, structure, and optical nonlinearity of soluble ternary cadmium copper tellurolate complex [Cd(μ-TeTol)4{Cu(PPh3)2}2] (Tol = 4-tolyl)