Abstract

2-Ethyl-1-phenylindazolium hexafluorophosphate was deprotonated by potassium 2-methyl-butan-2-olate to give the N-heterocyclic carbene of indazole, i.e., indazol-3-ylidene. This N-heterocyclic carbene undergoes a ring transformation to 9-ethylaminoacridine. Trapping of the carbene with sulfur, silver(I) oxide, and carbonylbis(triphenylphosphane)rhodium(I) chloride resulted in the formation of indazolethione, indazolone (X-ray structure analysis), and carbonylbis(triphenylphosphane)(2-ethyl-1-phenyl-1H-indazol-3-ylidene)rhodium(I) hexafluorophosphate (X-ray structure analysis), respectively. Reaction of the indazolium salt with phenolate and thiophenolate gave an N-ethyl-2-(phenylamino)benzimidate and benzimidothioate, respectively.

1 Introduction

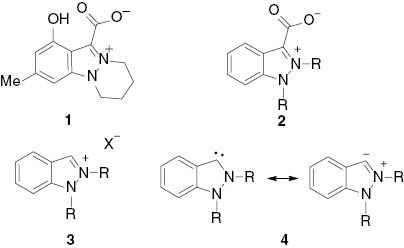

The number of publications dealing with indazoles has increased considerably during the last decade. Progress in the field of indazole chemistry concerning syntheses [1–4], structures [5], metalations [6, 7], and biological activities [8–11] has been summarized in recent review articles and book chapters. To date, only very few examples of natural products possessing the indazole ring have been discovered [12–14]. Among those, nigellicin (1) has been isolated from Nigella sativa (Scheme 1) [14]. This alkaloid belongs to the class of pseudo-cross-conjugated heterocyclic mesomeric betaines known to provide versatile starting materials for the generation of N-heterocyclic carbenes (NHC). Indeed, indazol-3-ylidenes 4 are formed on thermal decarboxylations of indazolium-3-carboxylates 2, when stabilizing effects such as hydrogen bonds to protic solvents or water of crystallization are absent [15]. The pseudo-cross-conjugated mesomeric betaines, pyrazolium-3-carboxylates [16] and imidazolium-2-carboxylates [17–22], behave similarly, and normal N-heterocyclic carbenes (nNHC) are formed effectively under relatively mild conditions. By contrast, decarboxylations of imidazolium-4-carboxylates, which are members of the class of cross-conjugated heterocyclic mesomeric betaines, to the abnormal N-heterocyclic carbene (aNHC) imidazole-4-ylidene require harsh conditions [22]. The relationship between N-heterocyclic carbenes and mesomeric betaines has been the subject of recent review articles [23, 24]. The deprotonation of indazolium salts 3 is an alternative pathway for the generation of indazol-3-ylidenes 4. In general, indazol-3-ylidenes (and pyrazol-3-ylidenes) have a chemistry of their own that sets them apart from the chemistry of N-heterocyclic carbenes of other ring systems [25–29]. Whereas the majority of N-heterocyclic carbenes are strong σ donors in transition metal-catalyzed cross-coupling reactions, indazol-3-ylidenes can be applied in coordination chemistry [30] and heterocycle synthesis [23–26]. In continuation of our studies of N-heterocyclic carbenes in synthesis [27–29] and catalysis [31], we describe here an indazolethione, an indazolone, and the formation of a rhodium complex as well as an indazole-acridine rearrangement of 2-ethyl-1-phenyl-indazol-3-ylidene. In addition, we report a ring-opening reaction of the indazole ring to a benzamide and a benzothioamide.

Betaines, salts and N-heterocyclic carbenes of indazole.

2 Results and discussion

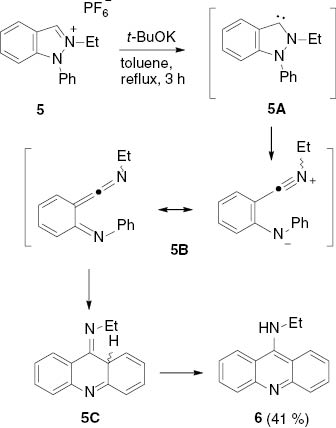

2-Ethyl-1-phenylindazolium hexafluorophosphate 5, prepared by ethylation of 1-phenylindazole using diethyl sulfate, was deprotonated with t-BuOK in toluene to give the 9-ethylaminoacridine 6 (Scheme 2). The mechanism of this reaction can be formulated in analogy to related transformations starting from indazol-3-ylidenes [26] as well as pyrazole-3-ylidenes [16] as follows: Deprotonation of the indazolium salt 5 gives the indazol-3-ylidene 5A, which undergoes a ring opening by N–N bond cleavage to ketenimine 5B. Subsequent ring–closure results in the formation of 5C, which tautomerizes to yield the acridine 6. DFT calculations have revealed that the ring–closure from 5B to 5C is predominantely pericyclic in nature [16, 26].

Ring transformation of indazolium salt 5 to acridine 6 via the N-heterocyclic carbene of an indazole.

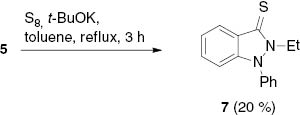

In the present studies, we investigated some interception reactions. Thus, reaction of indazolium salt 5 with t-BuOK in toluene at reflux temperature in the presence of sulfur gave indazole-3-thione 7, although in low yield (Scheme 3). Thione formations are supposed to be typical trapping reactions of N-heterocyclic carbenes.

Trapping of the NHC derived from 5 by sulfur.

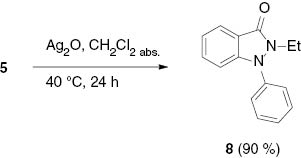

The corresponding oxygen analogue of thione 7, 2-ethyl-1-phenylindazolone 8, could be obtained on treatment of 5 with silver(I) oxide in anhydrous dichloromethane in excellent yields (Scheme 4). On examination of the reaction mixture by electrospray ionization mass spectrometry (ESIMS), the silver adduct of indazol-3-ylidene was unambiguously detected at m/z=551.0 (2 carbene + Ag+) when a sample was sprayed from MeOH at 0 V fragmentor voltage. A similar reaction, but in the presence of copper(I) chloride, has been observed with a triazolylidene that reacted with CsOH to give the corresponding triazolium-olates [32].

Indazolone formation starting from indazolium salt 5.

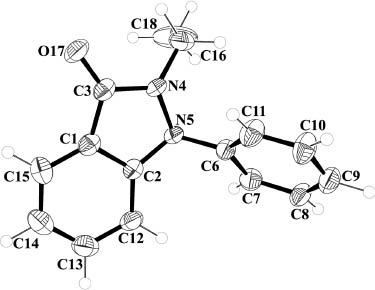

The indazolone 8 dissolved in THF displays a strong, broad but structureless fluorescence emission in the range 378–570 nm with a maximum at 425 nm (excitation wavelength 317 nm). Upon excitation at 248 nm, an additional broad, slightly structured fluorescence peak centered at 330 nm appears. This weaker emission can probably be attributed to the phenyl substituent. Single crystals of indazolone 8 suitable for an X-ray structure determination (Fig. 1) were obtained by slow evaporation of a concentrated solution in diethyl ether. The compound crystallizes in the monoclinic space group P21/c (no. 14) with Z=4. The phenyl ring is twisted with respect to the plane of the indazolone by 79.3° (torsion angle C2–N5–C6–C7; crystallographic numbering). The C–O bond length (C3 and O17; crystallographic numbering) was determined to be 123.5(4) pm.

Molecular structure of indazolone 8 in the solid state. Displacement ellipsoids are drawn at the 50 % probability level, H atoms as spheres with arbitrary radius.

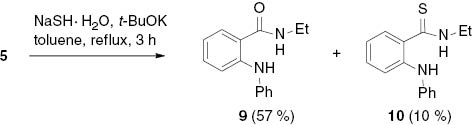

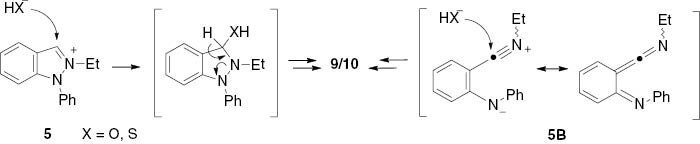

Reaction of the indazolium salt 5 with sodium hydrogen sulfide hydrate gave a mixture of N-ethyl-2-(phenylamino)benzamide (9) as the main product and the corresponding thioamide 10 as a result of two competing nucleophiles (Scheme 5).

Competing ring-opening reactions on treatment of indazolium salt 5 with NaSH·H2O.

The formation of the products 9 and 10 can either be explained by the nucleophilic attack of hydroxide or hydrogen sulfide, respectively, to the iminium bond of the indazolium salt 5, or by interception of the ketenimine 5B (Scheme 6). An interception of a ketenimine intermediate, although formed under inert conditions, with water has been reported [33]. Its formation as a byproduct was also observed on treatment of an N-ethyl indazolium-carboxylate with lithium silylcuprate [34]. Benzothioamide 10 is a known compound. It has been prepared before by treatment of a 3,1,2-benzothiazaphosphorine-4-thione with ethylamine [35].

Proposed mechanisms for the formation of 9 and 10.

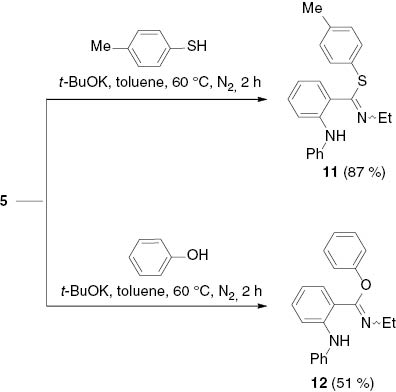

Correspondingly, 4-methylthiophenol and phenol converted the indazolium salt 5 into p-tolyl N-ethyl-2-(phenylamino)benzimidothioate (11) and phenyl N-ethyl-2-(phenylamino)benzimidate (12) (Scheme 7).

Ring cleavage of indazolium salt 5 to form a benzimidate (12) and a benzthioimidate (11).

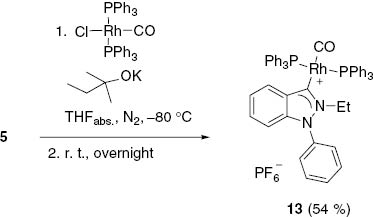

Finally, we trapped the N-heterocyclic carbene indazol-3-ylidene as a rhodium complex. Deprotonation of 2-ethyl-1-phenyl-indazolium hexafluorophosphate (5) with potassium 2-methyl-butan-2-olate in anhydrous THF at –80°C resulted in the formation of indazol-3-ylidene which was trapped by carbonylbis(triphenylphosphane)rhodium(I) chloride to give the rhodium complex 13 in 54% yield as yellow crystals (Scheme 8).

Synthesis of the rhodium complex 13.

In the 13C NMR spectra of 13, measured in CDCl3, the signal of the former carbene carbon atom of the indazole ligand appears at δ=186.6 ppm. The signal of the CO ligand was detected at 191.3 ppm. In comparison to salt 5, in the 1H NMR spectrum, the resonance of 5-H is shifted upfield by Δδ=0.54 ppm on complex formation. However, this value is also influenced by a solvent change from CDCl3 to [D6]DMSO, in which the salt is soluble. The CO frequency can be seen in the IR spectrum at 1974 cm–1. A comparison with the stretching frequencies of the CO ligands in comparable complexes (2009 and 1994 cm–1) [25] indicates very strong donor strengths of these indazol-3-ylidenes as already postulated earlier on comparing different stretching frequencies of selected 5-membered NHCs [30] or 13C NMR resonance frequencies of several palladium carbene complexes [36]. ESIMS were taken in MeOH solution. Samples were also sprayed from MeOH at fragmentor voltages between 0 and 150 V at 300°C drying gas temperature. At 0 V fragmentor voltage, the base peak corresponds to the molecular ion at m/z=877.2. The peak at m/z=849.2 at voltages above 100 V is due to the loss of CO, and the peak at m/z=615.0 is due to the loss of one molecule of PPh3. Additional peaks were detected at m/z=587.0 (–CO, –PPh3) and m/z=223.1, which corresponds to the carbene.

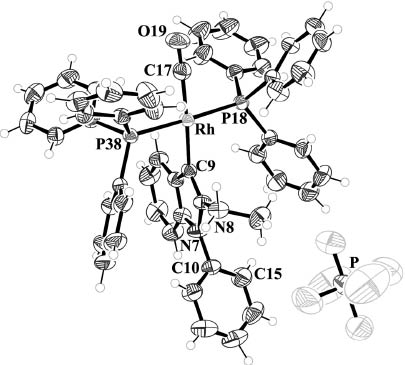

Single crystals of 13 were obtained by slow evaporation of a concentrated solution in CH2Cl2-i-PrOH, which allowed the determination of the solid-state structure (Fig. 2). The complex crystallizes in the triclinic space group P1̅ (no. 2) with Z=2. The Rh–Ccarbene and Rh–CCO bond lengths (Rh–C9 and Rh–C17; crystallographic numbering) were determined to be 208.3(2) and 186.9(3) pm, respectively. The phenyl substituent is rotated by 71.5(4)° out of the plane of the indazole ring (C4–N7–C10–C15).

Molecular structure of complex 13 in the solid state. Displacement ellipsoids are drawn at the 50 % probability level, H atoms as spheres with arbitrary radius.

In summary, we generated the N-heterocyclic carbene of 2-ethyl-1-phenylindazole by deprotonation of the corresponding indazolium salt. The carbene can be trapped as thione, oxide, or rhodium complex. It rearranges to 9-aminoethylacridine upon warming. Treatment of the indazolium salt with phenolate and thiophenolate resulted in a ring cleavage of the indazole ring to give a benzimidate and a benzthioimidate, respectively.

3 Experimental section

Nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectra were measured with Bruker Avance 400 MHz and Bruker Avance III 600 MHz instruments. 1H NMR spectra were recorded at 400 or 600 MHz, 13C NMR spectra at 100 or 150 MHz, with the solvent peak or tetramethylsilane used as the internal reference. Multiplicities are described by using the following abbreviations: s=singlet, d=doublet, t=triplet, q=quartet, and m=multiplet. The mass spectra were measured with a Varian 320 MS Triple Quad GC/MS/MS instrument. The ESIMS were measured with an Agilent LCMSD instrument series HP 1100. Samples for ESI mass spectrometry were sprayed from methanol at 30 V fragmentor voltage unless otherwise noted. Melting points are uncorrected and were determined in an apparatus according to Dr. Tottoli (Büchi). Yields are not optimized.

3.1 2-Ethyl-1-phenyl-1H-indazole-3(2H)-thione (7)

A solution of 1 mmol of the indazolium salt 5 [26], 2 mmol of sulfur and 1.2 mmol of potassium t-butoxide in 20 mL of toluene was stirred for 3 h at reflux temperature. After evaporation of the solvent in vacuo, the crude reaction product was purified by flash column chromatography (petroleum ether-ethyl acetate=5:1) and dried in vacuo. Yield: 50 mg of a yellow solid (20 %); m.p.: 90–92°C. – 1H NMR (CDCl3 + TMS): δ=8.12 (dt, J=8.0, 1.0 Hz, 1H, Ar-H), 7.59–7.47 (m, 4H, Ar-H), 7.32–7.24 (m, 3H, Ar-H), 7.00 (dt, J=8.3, 0.7 Hz, 1H, Ar-H), 4.38 (q, J=7.1 Hz, 2H, CH2-H), 1.25 (t, J=7.1 Hz, 3H, CH3-H) ppm. – 13C NMR (CDCl3 + TMS): δ=172.8, 145.7, 137.7, 132.3, 130.3, 129.9, 127.3, 127.2, 125.2, 123.2, 110.9, 41.1, 12.9 ppm. – IR (ATR): ν=3045, 3031, 2978, 2950, 2932, 1612, 1588, 1491, 1457, 1306, 1276, 1150, 1033, 977, 840, 748, 698, 609, 490 cm–1. – MS ((+)-ESI): m/z (%)=255.0 (100) [M+H]+. – HRMS ((+)-ESI): m/z=255.0958 (calcd. 255.0956 for [C15H15N2S]+).

3.2 2-Ethyl-1-phenyl-indazol-3-one (8)

A solution of 0.2 mmol of the indazolium salt 5 [26] and 0.4 mmol of silver(I) oxide in 5 mL of dichloromethane was stirred for 24 h at 40°C. After evaporation of the solvent in vacuo, the crude reaction product was purified by flash column chromatography (silica gel; dichloromethane) and dried in vacuo. Yield: 43 mg (90 %) of a colorless solid; m.p.: 80–82°C. – 1H NMR ([D6]DMSO): δ=7.78 (ddd, J=7.6, 0.9, 0.8 Hz, 1H, Ar-H), 7.58–7.53 (m, 3H, Ar-H), 7.46–7.38 (m, 3H, Ar-H), 7.24 (ddd, J=7.6, 7.0, 0.8 Hz, 1H, Ar-H), 7.14 (d, J=8.4 Hz, 1H, Ar-H), 3.70 (q, J=7.1 Hz, 2H, CH2-H), 1.04 (t, J=7.1 Hz, 3H, CH3-H) ppm. – 13C NMR ([D6]DMSO): δ=162.6, 149.3, 140.3, 132.7, 130.0, 128.0, 124.8, 123.2, 122.7, 117.5, 112.0, 37.3, 12.9 ppm. – IR (ATR): ν=2915, 2848, 1472, 1462, 1021, 958, 887, 843, 718, 557, 492, 473 cm–1. – MS (70 eV): m/z=238.2 [M]+. – HRMS ((+)-ESI): m/z=239.1183 (calcd. 239.1184 for [C15H15N2O]+).

3.3 N-Ethyl-2-(phenylamino)benzamide (9) and N-ethyl-2-(phenylamino)benzthioamide (10)

A solution of 1 mmol of the indazolium salt 5 [26], 1 mmol of sodium hydrogensulfide hydrate, and 1.2 mmol of potassium t-butoxide in 20 mL of toluene was stirred for 3 h at reflux temperature. After evaporation of the solvent in vacuo, the crude reaction product was purified by flash column chromatography (petroleum ether-ethyl acetate=5:1) and dried in vacuo.

3.4 N-Ethyl-2-(phenylamino)benzamide (9)

Yield: 137 mg (57 %), all spectroscopic data are identically with the literature values [33].

3.5 N-Ethyl-2-(phenylamino)benzothioamide (10)

Yield: 26 mg of a yellow solid (10 %); m.p.: 107–109°C. ref. [37]: 116°C. – 1H NMR (CDCl3 + TMS): δ=8.23 (s, 1H, PhNH-H), 7.86 (bs, 1H, EtNH-H), 7.24–7.11 (m, 5H, Ar-H), 7.02 (dd, J=8.5, 1.0 Hz, 2H, Ar-H), 6.88 (tt, J=7.3, 1.0 Hz, 1H, Ar-H), 6.76 (ddd, J=7.7, 7.4, 1.0 Hz, 1H, Ar-H), 3.71 (dq, J=5.4, 7.3 Hz, 2H, CH2-H), 1.23 (t, J=7.3 Hz, 3H, CH3-H) ppm. – 13C NMR (CDCl3 + TMS): δ=198.0, 142.1, 141.7, 130.7, 130.4, 129.4, 126.9, 121.9, 119.7, 119.4, 117.1, 40.9, 13.2 ppm. – IR (ATR): ν=3166, 3036, 3014, 2978, 2929, 1588, 1505, 1463, 1418, 1372, 1307, 1251, 1210, 1150, 1088, 1023, 967, 742, 696, 486 cm–1. – MS ((+)-ESI): m/z=279.0 [M+Na+]. – HRMS ((+)-ESI): m/z=257.1110 (calcd. 257.1112 for [C15H17N2S]+).

3.6 p-Tolyl-N-ethyl-2-(phenylamino)benzimidothioate (11)

A solution of 0.5 mmol of indazolium salt 5 [26], 0.5 mmol of 4-methylbenzenethiol and 0.6 mmol of potassium t-butoxide in 20 mL of toluene was stirred for 2 h at 60°C. After evaporation of the solvent in vacuo, the crude reaction product was purified by flash column chromatography (petroleum ether-ethyl acetate=5:1) and dried in vacuo. Yield: 150 mg of a yellow oil (87 %). – 1H NMR (CDCl3 + TMS): δ=9.11 (s, 1H, PhNH-H), 7.56 (dd, J=7.9, 1.5 Hz, 1H, Ar-H), 7.30–7.25 (m, 3H, Ar-H), 7.10–7.07 (m, 4H, Ar-H), 7.03 (ddd, J=8.0, 7.0, 1.5 Hz, 1H, Ar-H), 6.97–6.92 (m, 3H, Ar-H), 6.61 (ddd, J=7.9, 7.0, 1.2 Hz, 1H, Ar-H), 3.80 (q, J=7.3 Hz, 2H, CH2-H), 2.24 (s, 3H, PhMe-H), 1.41 (t, J=7.3 Hz, 3H, CH2CH3-H) ppm. – 13C NMR (CDCl3 + TMS): δ=161.1, 142.8, 142.4, 137.3, 132.1, 132.0, 129.8, 129.7, 129.4, 129.3, 124.0, 121.4, 119.1, 118.6, 115.9, 49.3, 21.1, 16.0 ppm. – IR (ATR): ν=3019, 2967, 2929, 2867, 1588, 1510, 1449, 1313, 1197, 1017, 926, 804, 745, 694, 491 cm–1. – MS ((+)-ESI): m/z=347.2. – HRMS ((+)-ESI): m/z=347.1583 (calcd. 347.1582 for [C22H23N2S]+).

3.7 Phenyl-N-ethyl-2-(phenylamino)benzimidate (12)

A solution of 0.5 mmol of the indazolium salt 5 [26], 0.6 mmol of phenol and 0.6 mmol of potassium t-butoxide in 20 mL of toluene was stirred for 2 h at 60°C. After evaporation of the solvent in vacuo, the crude reaction product was purified by flash column chromatography (petroleum ether-ethyl acetate=3:1) and dried in vacuo. Yield: 80 mg of a colorless solid (51 %); m.p.: 68–70°C. –1H NMR (CDCl3 + TMS): δ=11.10 (s, 1H, PhNH-H), 7.57 (dd, J=8.1, 1.5 Hz, 1H, Ar-H), 7.39 (dd, J=8.5, 1.0 Hz, 1H, Ar-H), 7.36–7.32 (m, 2H, Ar-H), 7.29–7.25 (m, 4H, Ar-H), 7.19 (ddd, J=8.5, 7.0, 1.5 Hz, 1H, Ar-H), 7.06–6.98 (m, 2H, Ar-H), 6.92–6.89 (m, 2H, Ar-H), 6.62 (ddd, J=8.1, 7.0, 1.0 Hz, 1H, Ar-H), 3.53 (q, J=7.3 Hz, 2H, CH2-H), 1.27 (t, J=7.3 Hz, 3H, CH3-H) ppm. – 13C NMR (CDCl3 + TMS): δ=155.9, 154.1, 146.2, 141.7, 131.5, 130.4, 130.0, 129.4, 122.6, 122.4, 121.2, 117.2, 115.4, 114.7, 113.9, 42.5, 16.1 ppm. – IR (ATR): ν=3021, 2968, 2931, 1634, 1588, 1575, 1488, 1455, 1376, 1287, 1201, 1161, 1129, 1047, 893, 744, 690, 641 cm–1. – MS ((+)-ESI): m/z=317.2 [M+H]+. – HRMS ((+)-ESI): m/z=317.1656 (calcd. 317.1654 for [C21H21N2O]+).

3.8 Carbonylbis(triphenylphosphane)(2-ethyl-1-phenyl-1H-indazole-3-ylidene)rhodium(I) hexafluorophosphate (13)

A solution of 0.5 mmol of indazolium salt 5 [26] and 0.5 mmol of carbonylbis(triphenylphosphane)rhodium(I) chloride in 20 mL of THF was cooled to –80°C. Then, 0.3 mL of a 2-m solution of potassium 2-methylbutan-2-olate in THF was added dropwise. The reaction mixture was stirred overnight at room temperature. Yellow solids formed were filtered off, washed with 2 mL of ethyl acetate and dried in vacuo. Yield: 277 mg (54 %); m.p.: 212°C (dec.) – 1H NMR (CDCl3 + TMS): δ=7.54–7.52 (m, 3H, Ar-H), 7.49–7.42 (m, 19H, Ar-H), 7.37–7.34 (m, 13H, Ar-H), 6.92 (t, J=7.5 Hz, 1H, Ar-H), 6.76–6.71 (m, 3H, Ar-H), 3.93 (q, J=7.3 Hz, 2H, CH2-H), 0.57 (t, J=7.3 Hz, 3H, CH3-H) ppm. – 13C NMR (CDCl3 + TMS): δ=191.3, 186.6, 140.5, 133.8 (dd, J=7.4, 6.6 Hz), 133.3, 132.5 (dd, J=24.0, 23.0 Hz), 132.1, 131.4, 131.0, 130.6, 129.5, 128.8 (dd, J=5.9, 5.0 Hz), 128.1, 126.9, 122.6, 109.5, 49.2, 13.8 ppm. – IR (ATR): ν=3058, 1974, 1497, 1437, 1306, 1119, 1091, 829, 744, 721, 693, 556, 514, 496 cm–1. – MS ((+)-ESI): m/z=877.2 [M]+. – HRMS ((+)-ESI): m/z=877.1984 (calcd. 877.1984 for [C52H44N2OP2Rh]+).

3.9 Crystal structure determinations

Suitable single crystals of compounds 8 and 13 were selected under a polarization microscope and mounted in a glass capillary (d=0.3 mm). Data collections were carried out at T=223(2) K using graphite-monochromatized MoKα radiation (λ=0.71073 Å) on a single-crystal diffractometer (Stoe IPDS II). The crystal structures were solved by direct methods using shelxs-97 [38] and refined with full-matrix least-squares calculations on F2 (shelxl-97) [38]. All non-H atoms were located in difference Fourier maps and were refined with anisotropic displacement parameters. The H positions of compound 8 were taken from a final ΔF synthesis. In the case of compound 13, the hydrogen positions at C59 and C60 (in both CH2Cl2 molecules) were fixed geometrically and treated as riding, with C–H=0.97 Å and Uiso(H)=1.2 Ueq(C).

C15H14N2O (8) Monoclinic space group P21/c (no. 14). Cell parameters: a=10.476(3), b=9.250(2), c=15.742(4) Å, β=121.95(2)°, V=1294.4(5) Å3, Z= 4, dcalcd.=1.22 g cm–3, F(000)=504 e. The structure refinement using 2449 independent reflections and 219 parameters converged at R1=0.0639, wR2=0.1012 [I>2 σ(I)], goodness of fit on F2=1.040, residual electron density 0.219 and –0.196 e Å–3.

C54H48Cl4F6N2OP3Rh (13) Triclinic space group P1̅ (no. 2). Cell parameters: a=12.183(1), b=14.658(1), c=15.803(2) Å, α=100.71(1), β=103.32(1), γ=91.90(1)°; V=2689.6(5) Å3, Z=2, dcalcd.=1.47 g cm–3, F(000)=1212 e. The structure refinement using 9879 independent reflections and 816 parameters converged at R1=0.0584, wR2=0.1135 [I>2 σ(I)], goodness of fit on F2=1.015, residual electron density 1.19 and –0.79 e Å–3.

CCDC 1002044 (compound 8) and CCDC 1002043 (compound 13) contain the supplementary crystallographic data for this paper. These data can be obtained free of charge from The Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre via www.ccdc.cam.ac.uk/data_request/cif.

Acknowledgments

Dr. Gerald Dräger, University of Hannover, Hannover, Germany, is greatfully acknowledged for measuring the high-resolution mass spectra. We thank PD Dr. Jörg Adams, Clausthal University of Technology, for measuring the fluorescence spectra.

References

[1] W. Stadlbauer in Science of Synthesis. Vol. 12 (Ed.: R. Neier), Thieme Verlag, Stuttgart 2002, pp. 227–324.Search in Google Scholar

[2] J. Elguero in Comprehensive Heterocyclic Chemistry, Vol. 3 (Eds.: A. R. Katritzky, C. W. Rees, E. F. V. Scriven), Pergamon, Oxford 1996, pp. 1–75.Search in Google Scholar

[3] W. Stadlbauer in Houben-Weyl, Methoden der Organischen Chemie, Vol. E8b (Ed.: E. Schaumann). Thieme Verlag, Stuttgart 1994, pp. 764–864.Search in Google Scholar

[4] A. Schmidt, A. Beutler, B. Snovydovych, Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2008, 4073–4095.10.1002/ejoc.200800227Search in Google Scholar

[5] J. Elguero, I. Alkorta, R. M. Claramunt, P. Cabildo, P. Cornago, M. Á. Farrán, M. Á. García, C. López, M. Pérez-Torralba, D. Santa Maria, D. Sanz, Chem. Heterocycl. Compds. 2013, 49, 177–202.Search in Google Scholar

[6] S. Roy, S. Roy, G. W. Gribble, Topics Heterocycl. Chem. 2012, 29, 155.Search in Google Scholar

[7] H. Ila, J. T. Markiewicz, V. Malakhov, P. Knochel, Synthesis 2013, 45, 2343–2371.10.1055/s-0033-1338501Search in Google Scholar

[8] B. Aguilera-Venegas, C. Olea-Azar, V. J. Aran, H. Speisky, Future Med. Chem. 2013, 5, 1843–1859.Search in Google Scholar

[9] A. Shafakat, A. Nasir, B. A. Dar, V. Pradhan, M. Farooqui, Mini-Rev. Med. Chem. 2013, 13, 1792–1800.Search in Google Scholar

[10] A. Thangadurai, M. Minu, S. Wakode, A. Agrawal, U. Kulandaivelu, B. Narasimhan, Acta Pharm. Sci. 2011, 53, 347–361.Search in Google Scholar

[11] H. Cerecetto, A. Gerpe, M. González, V. J. Arán, C. Ochoa de Ocáriz, Mini-Rev. Med. Chem. 2005, 5, 869–878.Search in Google Scholar

[12] Y.-M. Liu, Y.-H. Jiang, Q.-H. Liu, B.-Q. Chen, Phytochem. Lett. 2013, 6, 556.Search in Google Scholar

[13] Y.-M. Liu, J.-S. Yang, Q.-H. Liu, Chem. Pharm. Bull. 2004, 52, 454–455.Search in Google Scholar

[14] Atta-ur-Rahman, S. Malik, S. Hasan, M. I. Choudhary, C.-Z. Ni, J. Clardy, Tetrahedron Lett. 1995, 36, 1993–1996.Search in Google Scholar

[15] A. Schmidt, L. Merkel, W. Eisfeld, Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2005, 2124–2130.10.1002/ejoc.200500032Search in Google Scholar

[16] A. Schmidt, N. Münster, A. Dreger, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2010, 49, 2790–2793.Search in Google Scholar

[17] B. R. Van Ausdall, J. L. Glass, K. M. Wiggins, A. M. Aarif, J. Louie, J. Org. Chem. 2009, 74, 7935–7942.Search in Google Scholar

[18] M. Fèvre, J. Pinaud, A. Leteneur, Y. Gnanou, J. Vignolle, D. Taton, K. Miqueu, J.-M. Sotiropoulos, J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012, 134, 6776–6784.Search in Google Scholar

[19] X. Sauvage, G. Zaragoza, A. Demonceau, L. Delaude, Adv. Synth. Catal. 2010, 352, 1934–1948.Search in Google Scholar

[20] P. Bissinger, H. Braunschweig, T. Kupfer, K. Radacki, Organometallics 2010, 29, 3987–3990.10.1021/om100634bSearch in Google Scholar

[21] R. Lungwitz, T. Linder, J. Sundermeyer, I. Tkatchenko, S. Spange, Chem. Commun. 2010, 46, 5903–5905.Search in Google Scholar

[22] A. Schmidt, A. Beutler, M. Albrecht, F. J. Ramírez, Org. Biomol. Chem. 2008, 6, 287–295.Search in Google Scholar

[23] A. Schmidt, Z. Guan, Synthesis 2012, 3251–3268.10.1055/s-0032-1316787Search in Google Scholar

[24] A. Schmidt, S. Wiechmann, T. Freese, Arkivoc 2013, i, 424–469.10.3998/ark.5550190.p008.251Search in Google Scholar

[25] Z. Guan, J. C. Namyslo, M. H. H. Drafz, M. Nieger, A. Schmidt, Beilstein J. Org. Chem. 2014, 10, 832–840.Search in Google Scholar

[26] Z. Guan, S. Wiechmann, M. Drafz, E. Hübner, A. Schmidt, Org. Biomol. Chem. 2013, 11, 3558–3567.Search in Google Scholar

[27] A. Schmidt, B. Snovydovych, Synthesis 2008, 2798–2804.10.1055/s-2008-1067215Search in Google Scholar

[28] A. Schmidt, B. Snovydovych, S. Hemmen, Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2008, 4313–4320.10.1002/ejoc.200800456Search in Google Scholar

[29] A. Schmidt, A. Beutler, T. Habeck, T. Mordhorst, B. Snovydovych, Synthesis 2006, 1882–1894.10.1055/s-2006-942367Search in Google Scholar

[30] R. Jothibasu, H. V. Huynh, Chem. Commun. 2010, 46, 2986–2988.Search in Google Scholar

[31] A. Schmidt, A. Rahimi, Chem. Commun. 2010, 46,2995–2997.Search in Google Scholar

[32] A. Petronilho, H. Müller-Bunz, M. Albrecht, Chem. Commun. 2012, 48, 6499–6501.Search in Google Scholar

[33] A. M. González-Nogal, M. Calle, L. A. Calvo, P. Cuadrado, A. González-Ortega, Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2005, 4663–4669.10.1002/ejoc.200500438Search in Google Scholar

[34] A. M. González-Nogal, M. Calle, P. Cuadrado, Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2007, 6089–6096.10.1002/ejoc.200700742Search in Google Scholar

[35] L. Legrand, N. Lozac’h, Phosphorus Sulfur Rel. Elem. 1986, 26, 111–117.Search in Google Scholar

[36] H. V. Huynh, Y. Han, R. Jothibasu, J. A. Yang, Organometallics 2009, 28, 5395–5404.10.1021/om900667dSearch in Google Scholar

[37] L. Legrand, N. Lozac’h, Bull. Soc. Chim. France 1972, 10, 3892.Search in Google Scholar

[38] G. M. Sheldrick, Acta Crystallogr. 2008, A64, 112–122.Search in Google Scholar

©2015 by De Gruyter

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- In this Issue

- Editorial

- Zeitschrift für Naturforschung B now being published by De Gruyter

- Original Communications

- “Naked” S2O72– ions – the serendipitous formation of the disulfates [HPy]2[S2O7] and [bmim][HPy][S2O7] (HPy = pyridinium; bmim = 1-Butyl-3-methylimidazolium)

- Orthoamide und Iminiumsalze, LXXXVIII. Synthese N,N,N′,N′,N″,N″-persubstituierter Guanidiniumsalze aus N,N′-persubstituierten Harnstoff/Säurechlorid-Addukten**

- The acidic ionic liquid [BSO3HMIm]HSO4: a novel and efficient catalyst for one-pot, three-component syntheses of substituted pyrroles

- The influence of alkali-metal ions on the molecular and supramolecular structure of manganese(II) complexes with tetrachlorophthalate ligands

- New triazolothiadiazole and triazolothiadiazine derivatives as kinesin Eg5 and HIV inhibitors: synthesis, QSAR and modeling studies

- Two copper(I) complexes of bi- (or tri-)pyrazolyl ligands featuring Cu3pz3 or Cu4pz4 motifs

- Synthesis of ferrocenyl aryl ethers via Cu(I)/phosphine catalyst systems

- A prenylated acridone alkaloid and ferulate xanthone from barks of Citrus medica (Rutaceae)

- Synthesis and structural characterization of substituted phenols with a m-terphenyl backbone 2,4,6-R3C6H2OH (R=2,4,6-Me3C6H2, Me5C6)

- 2-Ethyl-1-phenylindazolium hexafluorophosphate. N-heterocyclic carbene formation, rearrangement, ring-cleavage reactions, and rhodium complex formation

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- In this Issue

- Editorial

- Zeitschrift für Naturforschung B now being published by De Gruyter

- Original Communications

- “Naked” S2O72– ions – the serendipitous formation of the disulfates [HPy]2[S2O7] and [bmim][HPy][S2O7] (HPy = pyridinium; bmim = 1-Butyl-3-methylimidazolium)

- Orthoamide und Iminiumsalze, LXXXVIII. Synthese N,N,N′,N′,N″,N″-persubstituierter Guanidiniumsalze aus N,N′-persubstituierten Harnstoff/Säurechlorid-Addukten**

- The acidic ionic liquid [BSO3HMIm]HSO4: a novel and efficient catalyst for one-pot, three-component syntheses of substituted pyrroles

- The influence of alkali-metal ions on the molecular and supramolecular structure of manganese(II) complexes with tetrachlorophthalate ligands

- New triazolothiadiazole and triazolothiadiazine derivatives as kinesin Eg5 and HIV inhibitors: synthesis, QSAR and modeling studies

- Two copper(I) complexes of bi- (or tri-)pyrazolyl ligands featuring Cu3pz3 or Cu4pz4 motifs

- Synthesis of ferrocenyl aryl ethers via Cu(I)/phosphine catalyst systems

- A prenylated acridone alkaloid and ferulate xanthone from barks of Citrus medica (Rutaceae)

- Synthesis and structural characterization of substituted phenols with a m-terphenyl backbone 2,4,6-R3C6H2OH (R=2,4,6-Me3C6H2, Me5C6)

- 2-Ethyl-1-phenylindazolium hexafluorophosphate. N-heterocyclic carbene formation, rearrangement, ring-cleavage reactions, and rhodium complex formation