Abstract

In our efforts to investigate the influence of alkali-metal ions on the formation of metal complexes with polyhalogen-substituted benzenedicarboxylates, two manganese(II) complexes of tetrachlorophthalic acid (1,2-H2BDC-Cl4), [Mn2(1,2-BDC-Cl4)2(H2O)9]·H2O (1) and [MnK2(1,2-BDC-Cl4)2(H2O)4]n (2), were synthesized and structurally characterized. Single-crystal X-ray diffraction studies have revealed that complexes 1 and 2 crystallize in space groups P1̅ and Pbcn, respectively. Complex 1 shows a discrete dinuclear structure, while complex 2 features a two-dimensional heterometallic framework containing rare Mn–O–K linkages. The results clearly suggest that the introduction of alkali metal ions does play a critical role in the construction of complexes 1 and 2 with distinct dimensionality and connectivity. Their spectroscopic, thermal, and fluorescence properties have also been studied briefly.

1 Introduction

The design of new discrete or infinite metal–organic coordination architectures is nowadays a very popular research direction, attracting increased attention in view of their intriguing structural diversities as well as their potential uses as functional materials [1–4]. The structural and functional diversification for such crystalline solids relies largely on the presence of suitable metal–ligand coordination interactions and supramolecular contacts (hydrogen bonding and other weak interactions). In this field, an effective and facile approach for the synthesis of these complexes is still the appropriate choice of well-designed organic ligands and metal ions [5–9]. Among widely used isomeric benzenedicarboxylic acids, phthalic acid with two carboxylic groups in ortho-position can bind metal ions in the most diverse coordination modes [10], leading to the formation of an extensive range of supramolecular coordination systems [11–16]. Furthermore, it has also been well demonstrated that the introduction of polarizable functional groups to the benzene ring is expected to increase the strength of the host–guest interactions [17]. In this context, to investigate the effect of substituents on the structures and properties of metal–phthalate complexes, phthalic acid with substituents such as methyl [18], nitro [19], fluoro [20], and chloro [21] groups have been documented so far. In our previous work, tetrafluorophthalic acid has been successfully used to construct a series of Ag(I), Cd(II), and Mn(II) coordination polymers by changing the organic molecule templates or the solvent systems [22–24]. Very recently, we have also shown that alkali metal ions play an essential role in the construction of coordination polymers with polyhalogen-substituted benzenedicarboxylate derivatives [25, 26]. Based on this strategy, herein, we selected tetrachlorophthalic acid (1,2-H2BDC-Cl4) as a feasible candidate to react with Mn(OAc)2·4H2O in EtOH-H2O solution. Two Mn(II) compounds, namely [Mn2(1,2-BDC-Cl4)2(H2O)9]·H2O (1) and [MnK2(1,2-BDC-Cl4)2(H2O)4]n (2), were formed, respectively. To our knowledge, only a few tetrachlorophthalate complexes of transition metals, in particular Cu(II) [27] and Ag(I) [28], have been documented as yet. Single-crystal X-ray structural analyses have indicated that 1 shows a discrete dinuclear structure, while 2 features a two-dimensional (2D) heterometallic–organic framework, revealing that the resulting structures can be properly regulated by the introduction of alkali metal ions. In addition, the spectroscopic, thermal, and luminescence properties of both complexes are discussed.

2 Results and discussion

2.1 Synthesis and general characterization

In this work, we selected 1,2-H2BDC-Cl4 to construct Mn(II) coordination architectures, aiming to explore the influence of alkali metal ions on the formation such complexes. Complex 1 was prepared by the direct reaction of equimolar quantitaties of 1,2-H2BDC-Cl4 and Mn(OAc)2·4H2O in EtOH-H2O solution. Upon addition of an equimolar amount of LiNO3 to the above reaction system, complex 1 could also be obtained by the same procedure (confirmed by X-ray diffraction). When KNO3 was used, yellow block-shaped crystals of 2 were produced instead. Using other alkali metal salts (e.g., NaNO3, RbNO3, CsNO3) as the potential structure-directing agents, we have not isolated any solid products suitable for X-ray analysis under the same conditions. Both complexes are stable at room temperature and insoluble in water and common organic solvents, which is consistent with their polymeric nature. In the IR spectra of 1 and 2, the broad peak appearing in the region of 3000–3500 cm–1 corresponds to the O–H stretching frequencies. Both complexes show characteristic bands of carboxylate groups appearing in the region of 1590–1650 cm–1 for the antisymmetric stretching vibrations and at 1340–1430 cm–1 for the symmetric stretching vibrations. In addition, the absence of a strong absorption band around 1715 cm–1 for the free 1,2-H2BDC-Cl4 molecule indicates that the 1,2-H2BDC-Cl4 ligands in 1 and 2 are completely deprotonated, which is consistent with the consideration of charge balance.

2.2 Structural descriptions of complexes 1 and 2

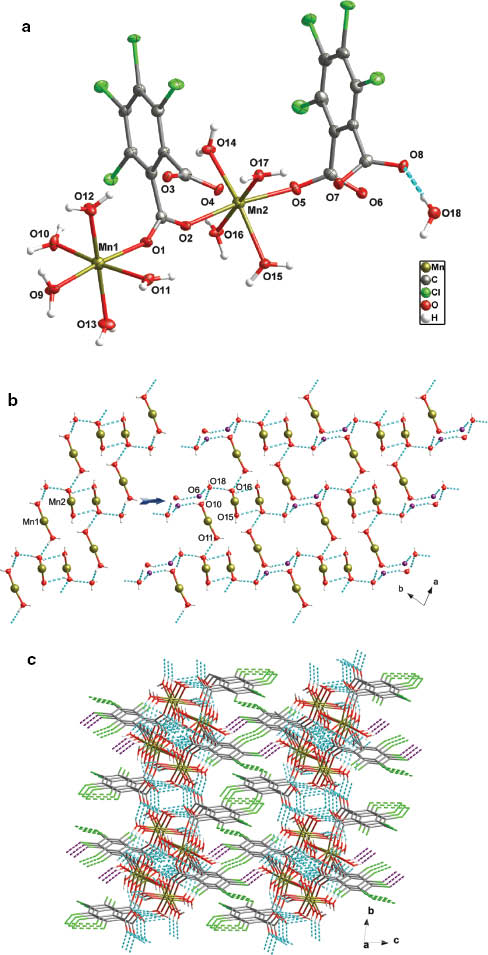

[Mn2(1,2-BDC-Cl4)2(H2O)9]·H2O (1) X-ray diffraction ana- lysis has revealed that complex 1 crystallizes in the triclinic space group P1̅ with Z = 2 and has a discrete dinuclear structure. The asymmetric unit is composed of two crystallographically independent Mn(II) ions (namely, Mn1 and Mn2), two 1,2-BDC-Cl4 dianions, nine metal-coordinated water molecules and one lattice water molecule. As shown in Fig. 1a, the Mn1 ion shows an octahedral coordination coming from one oxygen atom of one 1,2-BDC-Cl4 dianion and five aqua ligands with the Mn–O distances in the range of 2.125(3)–2.188(3) Å. The distorted octahedral geometry of Mn2 is provided by two oxygen donors of two 1,2-BDC-Cl4 ligands and four aqua ligands with the Mn–O distances in the range of 2.113(2)–2.260(2) Å. The 1,2-BDC-Cl4 ligands exhibit two types of coordination modes: one (1,2-BDC-Cl4I) is in a μ2-bridging fashion to connect Mn1 and Mn2 ions with the Mn···Mn distance of 6.454(1) Å, while the other one (1,2-BDC-Cl4II) adopts a terminal coordination mode at the Mn2 ion.

Views of (a) the coordination environments of the Mn1 and Mn2 ions in 1, (b) the water tape of 1, and (c) the 3D supramolecular architecture (Cl···Cl and C–H···Cl interactions are shown as bright green and violet dashed lines, respectively; irrelevant hydrogen atoms are omitted for clarity).

It should be pointed out that there are nine crystallographically independent coordinated aqua ligands [O9, O10, O11, O12, O13, O14, O15, O16, and O17] and one lattice water molecule [O18]. Among them, the coordinated water molecules of O10, O11, O15, O16, and the lattice water molecule of O18 as well as those of symmetry-related ones are arranged to afford a 1D metal-water cluster tape along the a axis, as shown in Fig. 1b (left). The O···O separations vary from 2.749(3) to 3.187 (3) Å with an average value of 2.893(3) Å, which is clearly shorter than the sum of the van der Waals radii (rvdW for O = 1.52 Å) and slightly longer than that found in liquid water (2.854 Å) [29], whereas the average O···O···O angle is 107.2(1)°. Furthermore, these water tapes are connected to each other through hydrogen bonds with the uncoordinated carboxylate atoms (O6), resulting in a 2D network (Fig. 1b, right). The tetrachlorinated benzene rings project on both the sides of such 2D motifs. Further analysis of the packing of the molecules has revealed that such layers with their parallel arrangement are connected by multiple Cl···Cl interactions (Cl2···Cl5i distance = 3.336 Å, i = –x–1, –y, –z+1; Cl4···Cl4ii distance = 3.629 Å, ii = –x+1, –y, –z+1; Cl7···Cl8iii distance = 3.632 Å, Cl8···Cl8iii distance = 3.512 Å, iii = –x, –y+1, –z+1) and intermolecular C–H···Cl interactions to generate a 3D supramolecular network (Fig. 1c). It should be pointed out that the Cl···Cl distance in 1 is shorter than twice Pauling’s van der Waals radius of the Cl atom (3.76 Å) [30], and is comparable to that stated by Bondi (3.52 Å) [31].

[MnK2(1,2-BDC-Cl4)2(H2O)4]n(2) Complex 2 crystallizes in the orthorhombic system with space group Pbcn with Z = 4 and shows a 2D heterometallic framework. The asymmetric unit contains half of one Mn(II) ion, one K(I) ion, one 1,2-BDC-Cl4 dianion, and two aqua ligands. Each Mn(II) ion adopts a distorted octahedral coordination geometry (MnO6) and is coordinated by four oxygen atoms from four different 1,2-BDC-Cl4 ligands with Mn–O distances of 2.182(3) and 2.185(3) Å and two terminal aqua ligands with Mn–O distances of 2.273(3) Å (Fig. 2a). The coordination environment around K(I) ion is shown in Fig. 2b. Each K(I) center is embraced by six carboxylate oxygen atoms from four 1,2-BDC-Cl4 ligands with K–O distances in the range of 2.648(3)–3.287(3) Å, two different aqua ligands with K–O distances of 2.747(5) and 2.935(3) Å, and one chlorine atom from a 1,2-BDC-Cl4 unit with K–Cl distances of 3.747(2) Å. In contrast to 1, each 1,2-BDC-Cl4 ligand in 2 is linked to two Mn(II) ions and four K(I) ions with one carboxylate group adopting a μ4-η2:η2-bridging mode and the other one adopting a μ4-η3:η1-bridging fashion. To the best of our knowledge, such a coordination mode has never been observed in metal complexes with phthalate or its substituted analogues. The connectivities lead to the formation of a 2D Mn(II)-K(I) heterometallic framework with the tetrachlorinated benzene rings lying on the two sides and containing a rare example of Mn–O–K linkage (Fig. 2c). Further analysis of the packing of the molecule has revealed that, similar to 1, weak Cl···Cl interactions (Cl1···Cl3i distance = 3.438 Å, Cl2···Cl4i distance = 3.643 Å, i = –x+1/2, –y+1/2, z–1/2) can be observed between adjacent coordination layers, which lead to the formation of a 3D supramolecular architecture (Fig. 2d).

Views of (a) the coordination environment of the Mn(II) ion in 2 (symmetry codes: #1: –x, y, –z+1/2; #2: –x, –y, –z+1; #3: x, –y, z–1/2), (b) the coordination environment of the K(I) ion in 2 (symmetry codes: #1: –x, y, –z+1/2; #3: x, –y, z–1/2; #4: x, –y+1, z–1/2), (c) the 2D heterometallic framework containing layered Mn–O–K linkages, and (d) the 3D supramolecular architecture (Cl···Cl interactions are shown as bright green dashed lines; irrelevant hydrogen atoms are omitted for clarity).

2.2.1 Thermal stability

The thermal stability of complexes 1 and 2 was investigated by thermogravimetric analysis (TGA) yielding the curves depicted in Fig. 3. The TGA trace of 1 shows that the first weight loss of 20.3 % occurring from 50 to ca. 165 °C corresponds to the loss of all water molecules (calculated, 20.1 %). With that, almost no weight loss was observed up to ca. 250 °C, where the complex began to decompose. Complex 2 is stable up to 70 °C and shows the first weight loss of 9.2 % in the temperature range of 70–150 °C corresponding to the release of four coordinated water molecules (calculated, 8.9 %). Subsequently, pyrolysis of the residual coordination framework is observed upon heating above 250 °C with a sharp weight loss. Further heating to 800 °C reveals a gradual weight loss of the sample.

TGA curves of complexes 1 and 2.

2.2.2 Luminescence properties

To explore their potential applications as luminescent crystalline materials, the emission spectra of complexes 1 and 2 as well as of the free ligand 1,2-H2BDC-Cl4 were recorded in the solid state at room temperature (Fig. 4). Excitation of the microcrystalline samples at 336 nm leads to the generation of broad fluorescence emissions in the range of 450–540 nm. The free ligand 1,2-H2BDC-Cl4 has a fluorescence emission band centered at 474 nm, which can be ascribed to the π → π* and/or n → π* transitions. For 1 and 2, excitation of the microcrystalline samples at 336 nm leads to the generation of intense fluorescence emissions with similar peak maxima observed in the blue region (1, 473 nm; and 2, 476 nm), which may be attributed to the ligand-centered transitions. In addition, the weaker shoulder peaks of the emission spectra around 508 nm can probably be assigned to intraligand transitions because a similar peak at about 510 nm also appears for 1,2-H2BDC-Cl4. Furthermore, the emission intensity of both complexes is obviously weaker than that of the free ligand, which is probably related to their complicated structures and the decay effect of high-energy C–H and/or O–H oscillators from the coordinated and lattice water molecules [32].

(color online). Solid-state fluorescence emission spectra of 1,2-H2BDC-Cl4 and of the complexes 1 and 2.

3 Conclusion

In summary, two Mn(II) complexes with a perchlorinated phthalate ligand 1,2-BDC-Cl4 have been synthesized and structurally characterized. Their structural diversity varies from a discrete dinuclear molecule to a 2D heterometallic framework, which are remarkably manipulated by the introduction of alkali metal ions. Investigation on the packing of the molecules of both complexes suggests that intermolecular C–H···Cl and/or Cl···Cl interactions are among the driving forces in the self-assembly of the lower-dimensional networks to generate the 3D supramolecular architectures. Accordingly, our present findings will enrich the crystal engineering strategies and offer the possibility of controlling the preparation of novel inorganic–organic hybrid materials based on halogenated carboxylate ligands.

4 Experimental section

All reagents and solvents were commercially available and used without further purification. The Fourier transform (FT) IR spectra (KBr pellets) were recorded on a Nicolet ESP 460 FT-IR spectrometer. Elemental analyses were performed with a PE-2400II (Perkin-Elmer) elemental analyzer. Thermogravimetric analysis (TGA) experiments were carried out on a Dupont thermal analyzer from room temperature to 800 °C (heating rate: 10 °C min–1, nitrogen stream). Photoluminescence spectra of the solid samples were recorded with a Varian Cary Eclipse spectrometer at room temperature.

4.1 Synthesis of [Mn2(1,2-BDC-Cl4)2(H2O)9]·H2O (1)

An ethanol solution (2 mL) of 1,2-H2BDC-Cl4 (91.2 mg, 0.3 mmol) was added to an aqueous (6 mL) solution of Mn(OAc)2·4H2O (73.5 mg, 0.3 mmol). Then, the mixture was stirred for ca. 30 min. The resulting solution was filtered and left to stand at room temperature. Yellow block-shaped crystals suitable for X-ray analysis were obtained after two weeks in 65 % yield (87.1 mg, on the basis of 1,2-H2BDC-Cl4). – Anal. for C16H20Cl8Mn2O18 (%): calcd. C 21.50, H 2.26; found C 21.26, H 2.27. – IR (KBr pellet): v = 3423 (br), 1646 (s), 1590 (vs), 1530 (m), 1433 (s), 1404 (m), 1344 (s), 1212 (w), 1131 (w), 918 (w), 843 (m), 672 (m), 650 (m), 615 (m) cm–1.

4.2 Synthesis of [MnK2(1,2-BDC-Cl4)2- (H2O)4]n (2)

The same synthetic procedure as that described for 1 was used except that KNO3 (60.6 mg, 0.6 mmol) was added, affording yellow block-shaped crystals of 2 upon slow evaporation of the solvent in 40 % yield (48.5 mg, on the basis of 1,2-H2BDC-Cl4). – Anal. for C16H8Cl8K2MnO12 (%): calcd. C 23.76, H 1.00; found C 24.03, H 1.02. – IR (KBr pellet): v = 3407 (br), 1592 (vs), 1532 (m), 1426 (s), 1388 (m), 1339 (s), 1207 (w), 1127 (w), 938 (w), 904 (w), 663 (m), 647 (m), 618 (m) cm–1.

4.3 X-ray structure determination

The single-crystal X-ray diffraction data for complexes 1 and 2 were collected on a Bruker Apex II CCD diffractometer with MoKα radiation (λ = 0.71073 Å) at room temperature. A semiempirical absorption correction was applied (SADABS) [33], and the program SAINT was used for integration of the diffraction profiles [34]. The structures were solved by Direct Methods using SHELXS and refined by the full-matrix least-squares techniques on F2 using SHELXL [35–38]. All nonhydrogen atoms were refined anisotropically. C-bound H atoms were placed in geometrically calculated positions and refined by using a riding model. H atoms of water were located in difference Fourier maps and refined in subsequent refinement cycles. Further crystallographic details are summarized in Table 1, selected bond lengths and angles are listed in Table 2, and hydrogen bond parameters are listed in Table 3.

Crystal structure data for 1 and 2.

| 1 | 2 | |

|---|---|---|

| Empirical formula | C16H20Cl8Mn2O18 | C16H8Cl8K2MnO12 |

| Mr | 893.80 | 808.96 |

| Crystal size, mm3 | 0.30 × 0.28 × 0.28 | 0.32 × 0.30 × 0.30 |

| Crystal system | triclinic | Orthorhombic |

| Space group | P1̅ | Pbcn |

| a, Å | 8.871(1) | 28.483(2) |

| b, Å | 13.113(1) | 7.333(1) |

| c, Å | 14.566(1) | 12.348(1) |

| α, deg | 80.11(1) | 90 |

| β, deg | 73.66(1) | 90 |

| γ, deg | 73.57(1) | 90 |

| V, Å3 | 1551.7(3) | 2579.2(3) |

| Z | 2 | 4 |

| Dcalcd, g cm–3 | 1.91 | 2.08 |

| μ(MoKα), cm–1 | 1.6 | 1.7 |

| F(000), e | 892 | 1596 |

| hkl range | –10 ≤ h ≤ +10 | –25 ≤ h ≤ +35 |

| –14 ≤ k ≤ +15 | –8 ≤ k ≤ +9 | |

| –17 ≤ l ≤ +17 | –15 ≤ l ≤ +15 | |

| Refl. measured/unique/Rint | 8340/5292/0.017 | 14097/2510/0.023 |

| Param. Refined | 397 | 178 |

| R(F)a/wR(F2)b | 0.0342/0.1460 | 0.0377/0.1380 |

| GOF (F2)c | 1.306 | 1.049 |

| Δρfin (max/min), e Å–3 | 0.70/–0.77 | 1.32/–1.89 |

aR1 = ∑||Fo|–|Fc||/∑|Fo|; bwR2 = [∑w(Fo2–Fc2)2/∑w(Fo2)2]1/2, w = [σ2(Fo2)+(AP)2+BP]–1, where P = (Max(Fo2, 0)+2Fc2)/3; cGoF = [∑w(Fo2–Fc2)2/(nobs–nparam)]1/2.

Selected bond lengths (Å) and angles (deg) for 1 and 2 with estimated standard deviations in parentheses.a

| 1 | 2 | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Distances | Distances | ||

| Mn1–O1 | 2.172(2) | Mn1–O1 | 2.185(3) |

| Mn1–O9 | 2.165(3) | Mn1–O1#1 | 2.185(3) |

| Mn1–O10 | 2.125(3) | Mn1–O4#2 | 2.182(3) |

| Mn1–O11 | 2.188(2) | Mn1–O4#3 | 2.182(3) |

| Mn1–O12 | 2.172(3) | Mn1–O5 | 2.273(3) |

| Mn1–O13 | 2.179(3) | Mn1–O5#1 | 2.273(3) |

| Mn2–O2 | 2.170(2) | K1–O1#1 | 3.287(3) |

| Mn2–O5 | 2.113(2) | K1–O1#3 | 2.858(3) |

| Mn2–O14 | 2.213(3) | K1–O2 | 2.648(3) |

| Mn2–O15 | 2.260(2) | K1–O3#1 | 3.143(4) |

| Mn2–O16 | 2.139(2) | K1–O3#4 | 2.809(4) |

| Mn2–O17 | 2.124(2) | K1–O4#3 | 2.787(3) |

| K1–O5#3 | 2.935(3) | ||

| K1–O6 | 2.747(5) | ||

| Angles | Angles | ||

| O1–Mn1–O9 | 174.8(1) | O1–Mn1–O1#1 | 114.9(1) |

| O1–Mn1–O10 | 90.0(1) | O1–Mn1–O4#2 | 86.7(1) |

| O1–Mn1–O11 | 84.3(1) | O1–Mn1–O4#3 | 93.6(1) |

| O1–Mn1–O12 | 99.3(1) | O1–Mn1–O5 | 82.3(1) |

| O1–Mn1–O13 | 89.2(1) | O1–Mn1–O5#1 | 162.2(1) |

| O9–Mn1–O10 | 92.2(1) | O4#2–Mn1–O4#3 | 179.4(1) |

| O9–Mn1–O11 | 93.7(1) | O4#2–Mn1–O5 | 92.1(1) |

| O9–Mn1–O12 | 85.4(1) | O4#2–Mn1–O5#1 | 87.5(1) |

| O9–Mn1–O13 | 85.8(1) | O5–Mn1–O5#1 | 81.2(2) |

| O10–Mn1–O11 | 173.9(1) | O1#1–K1–O1#3 | 86.4(1) |

| O10–Mn1–O12 | 91.3(1) | O1#1–K1–O2 | 74.9(1) |

| O10–Mn1–O13 | 98.3(1) | O1#1–K1–O3#1 | 68.3(1) |

| O11–Mn1–O12 | 87.5(1) | O1#1–K1–O3#4 | 107.9(1) |

| O11–Mn1–O13 | 83.8(1) | O1#1–K1–O4#3 | 58.4(1) |

| O12–Mn1–O13 | 167.2(1) | O1#1–K1–O5#3 | 112.7(1) |

| O2–Mn2–O5 | 170.9(1) | O1#1–K1–O6 | 159.4(1) |

| O2–Mn2–O14 | 96.4(1) | O1#3–K1–O2 | 149.8(1) |

| O2–Mn2–O15 | 83.4(1) | O1#3–K1–O3#1 | 85.2(1) |

| O2–Mn2–O16 | 87.3(1) | O1#3–K1–O3#4 | 125.9(1) |

| O2–Mn2–O17 | 90.00(1) | O1#3–K1–O4#3 | 73.1(1) |

| O5–Mn2–O14 | 92.6(1) | O1#3–K1–O5#3 | 60.8(1) |

| O5–Mn2–O15 | 87.9(1) | O1#3–K1–O6 | 78.4(1) |

| O5–Mn2–O16 | 94.3(1) | O2–K1–O3#1 | 108.6(1) |

| O5–Mn2–O17 | 88.2(1) | O2–K1–O3#4 | 83.0(1) |

| O14–Mn2–O15 | 167.7(1) | O2–K1–O4#3 | 76.9(1) |

| O14–Mn2–O16 | 82.9(1) | O2–K1–O5#3 | 148.6(1) |

| O14–Mn2–O17 | 98.6(1) | O2–K1–O6 | 112.4(1) |

| O15–Mn2–O16 | 84.9(1) | O3#1–K1–O3#4 | 59.9(2) |

| O15–Mn2–O17 | 93.7(1) | O3#1–K1–O5#3 | 53.3(1) |

| O16–Mn2–O17 | 177.1(1) | O3#1–K1–O6 | 123.3(1) |

| O3#4–K1–O4#3 | 158.1(1) | ||

| O3#4–K1–O5#3 | 65.6(1) | ||

| O3#4–K1–O6 | 92.2(1) | ||

| O4#3–K1–O5#3 | 133.8(1) | ||

| O4#3–K1–O6 | 103.3(2) | ||

| O5#3–K1–O6 | 71.6(1) | ||

aSymmetry codes, for 2, #1: –x, y, –z+1/2; #2: –x, –y, –z+1; #3: x, –y, z–1/2; #4: x, –y+1, z–1/2.

Hydrogen bond parameters in the crystal structures of 1 and 2.

| Complex | D–H···A | H···A (Å) | D···A (Å) | D–H···A (deg) | Symmetry code |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | O9–H9A···O8 | 1.98 | 2.751(3) | 167 | x, y+1, z |

| O5–H5B···O6 | 2.07 | 2.881(3) | 170 | x–1, y, z | |

| O9–H9A···O8 | 1.98 | 2.800(4) | 173 | x+1, y–1, z | |

| O9–H9B···O7 | 1.88 | 2.675(4) | 162 | –x+1, –y, –z | |

| O10–H10A···O6 | 1.99 | 2.732(4) | 149 | x+1, y–1, z | |

| O11–H11B···O15 | 2.07 | 2.861(4) | 160 | –x+1, –y, –z | |

| O12–H12A···O8 | 2.02 | 2.803(4) | 159 | x+1, y–1, z | |

| O12–H12B···O3 | 2.01 | 2.788(4) | 160 | ||

| O13–H13A···O5 | 2.05 | 2.820(4) | 155 | –x, –y, –z | |

| O14–H14A···Cl3 | 2.65 | 3.349(3) | 144 | –x, –y, –z+1 | |

| O14–H14B···O3 | 2.05 | 2.838(4) | 163 | x–1, y, z | |

| O15–H15A···O18 | 1.94 | 2.750(3) | 169 | –x, –y+1, –z | |

| O15–H15B···O2 | 2.25 | 2.979(4) | 148 | –x, –y, –z | |

| O15–H15B···O16 | 2.56 | 3.187(3) | 134 | –x, –y, –z | |

| O16–H16A···O3 | 1.99 | 2.746(4) | 152 | x–1, y, z | |

| O16–H16B···O1 | 2.31 | 3.036(4) | 149 | –x, –y, –z | |

| O16–H16B···O2 | 2.27 | 3.026(3) | 153 | –x, –y, –z | |

| O17–H17A···O4 | 1.90 | 2.707(4) | 167 | ||

| O17–H17B···O7 | 1.88 | 2.672(4) | 161 | ||

| O18–H18A···O8 | 2.01 | 2.829(4) | 173 | ||

| O18–H18B···O6 | 2.07 | 2.859(4) | 161 | –x, –y+1, –z | |

| 2 | O5–H5A···O3 | 2.00 | 2.733(5) | 148 | –x, –y, –z+1 |

| O5–H5B···O2 | 2.20 | 2.852(4) | 136 | x, y–1, z |

CCDC 1013362 and 1013363 contain the supplementary crystallographic data for this paper. These data can be obtained free of charge from The Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre via www.ccdc.cam.ac.uk/data_request/cif.

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge financial support by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (21201026), the Nature Science Foundation of Jiangsu Province (BK20131142), the Open Foundation of Jiangsu Province Key Laboratory of Fine Petrochemical Technology (KF1105), and a project funded by the Priority Academic Program Development (PAPD) of Jiangsu Higher Education Institutions.

References

[1] J. R. Li, J. Sculley, H. C. Zhou, Chem. Rev. 2012, 112, 869–932.Search in Google Scholar

[2] M. O’Keeffe, O. M. Yaghi, Chem. Rev. 2012, 112, 675–702.Search in Google Scholar

[3] C. Wang, T. Zhang, W. B. Lin, Chem. Rev. 2012, 112, 1084–1104.Search in Google Scholar

[4] Y. J. Cui, Y. F. Yue, G. D. Qian, B. L. Chen, Chem. Rev. 2012, 112, 1126–1162.Search in Google Scholar

[5] B. Moulton, M. J. Zaworotko, Chem. Rev. 2001, 101, 1629–1248.Search in Google Scholar

[6] B.-H. Ye, M.-L. Tong, X.-M. Chen, Coord. Chem. Rev. 2005, 249, 545–565.Search in Google Scholar

[7] Y.-F. Zeng, X. Hu, F.-C. Liu, X.-H. Bu, Chem. Soc. Rev. 2009, 38, 469–480.Search in Google Scholar

[8] R. Peng, M. Li, D. Li, Coord. Chem. Rev. 2010, 254, 2552–2555.Search in Google Scholar

[9] Z. Yin, Q. X. Wang, M. H. Zeng, J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012, 134, 4857–4863.Search in Google Scholar

[10] S. G. Baca, I. G. Filippova, O. A. Gherco, M. Gdaniec, Y. A. Simonov, N. V. Gerbeleu, P. Franz, R. Basler, S. Decurtins, Inorg. Chim. Acta 2004, 357, 3419–3429.10.1016/S0020-1693(03)00498-5Search in Google Scholar

[11] D. Sun, Z.-H. Wei, D.-F. Wang, N. Zhang, R.-B. Huang, L.-S. Zheng, Cryst. Growth Des. 2011, 11, 1427–1430.Search in Google Scholar

[12] J. Jin, S. Niu, Q. Han, Y. Chi, New J. Chem. 2010, 34, 1176–1183.Search in Google Scholar

[13] X. Li, M.-Q. Zha, X.-W. Wang, R. Cao, Inorg. Chim. Acta 2009, 362, 3357–3363.10.1016/j.ica.2009.03.017Search in Google Scholar

[14] X.-N. Cheng, W. Xue, W.-X. Zhang, X.-M. Chen, Chem. Mater. 2008, 20, 5345–5350.Search in Google Scholar

[15] A. Thirumurugan, S. Natarajan, Eur. J. Inorg. Chem. 2004, 4, 762–770.Search in Google Scholar

[16] H.-L. Liu, H.-Y. Mao, H.-Y. Zhang, C. Xu, Q.-A. Wu, G. Li, Y. Zhu, H.-W. Hou, Polyhedron 2004, 23, 943–948.10.1016/j.poly.2003.11.059Search in Google Scholar

[17] K. K. Tanabe, Z. Wang, S. M. Cohen, J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008, 130, 8508–8517.Search in Google Scholar

[18] G. A. Farnum, A. L. Pochodylo, R. L. LaDuca, Cryst. Growth Des. 2011, 11, 678–683.Search in Google Scholar

[19] D. Sun, F.-J. Liu, R.-B. Huang, L.-S. Zhang, CrystEngComm 2013, 15, 1185–1193.10.1039/C2CE26659HSearch in Google Scholar

[20] Y.-E. Cha, X. Li, S. Song, J. Solid State Chem. 2012, 196, 40–44.Search in Google Scholar

[21] N. Xu, D.-Z. Liao, S.-P. Yan, Z.-H. Jiang, J. Coord. Chem. 2008, 61, 435–440.Search in Google Scholar

[22] S.-C. Chen, Z.-H. Zhang, Q. Chen, L.-Q. Wang, J. Xu, M.-Y. He, M. Du, X.-P. Yang, R. A. Jones, Chem. Commun. 2013, 49, 1270–1272.Search in Google Scholar

[23] S.-C. Chen, Z.-H. Zhang, M.-Y. He, H. Xu, Q. Chen, Z. Anorg. Allg. Chem. 2010, 636, 824–829.Search in Google Scholar

[24] S.-C. Chen, J. Qin, Z.-H. Zhang, X.-X. Cai, J. Gao, L. Liu, M.-Y. He, Q. Chen, Z. Naturforsch. 2013, 68b, 277–283.Search in Google Scholar

[25] S.-C. Chen, Z.-H. Zhang, K.-L. Huang, H.-K. Luo, M.-Y. He, M. Du, Q. Chen, CrystEngComm 2013, 15, 9613–9622.10.1039/c3ce41108gSearch in Google Scholar

[26] S.-C. Chen, Z.-H. Zhang, Y.-S. Zhou, W.-Y. Zhou, Y.-Z. Li, M.-Y. He, Q. Chen, M. Du, Cryst. Growth Des. 2011, 11, 4190–4197.Search in Google Scholar

[27] M. Liang, D.-Z. Liao, Z.-H. Jiang, S.-P. Yan, P. Cheng, Inorg. Chem. Commun. 2004, 7, 173–175.Search in Google Scholar

[28] D. Sun, R.-B. Huang, L.-S. Zheng, Z. Naturforsch. 2011, 66b, 1035–1041.Search in Google Scholar

[29] A. H. Narten, W. E. Thiessen, L. Blum, Science 1982, 217, 1033–1034.10.1126/science.217.4564.1033Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[30] L. Pauling. The Nature of the Chemical Bond, Cornell University Press, Ithaca, New York, 1960.Search in Google Scholar

[31] A. Bondi, J. Phys. Chem. 1964, 68, 441–451.Search in Google Scholar

[32] B. Chen, Y. Yang, F. Zapata, G. Qian, Y. Luo, J. Zhang, E. B. Lobkovsky, Inorg. Chem. 2006, 45, 8882–8886.Search in Google Scholar

[33] G. M. Sheldrick. SADABS, Program for Empirical Absorption Correction of Area Detector Data, University of Göttingen, Göttingen (Germany) 2002.Search in Google Scholar

[34] SAINT, Software Reference Manual, Bruker Analytical X-ray Instruments Inc., Madison, Wisconsin (USA) 1998.Search in Google Scholar

[35] G. M. Sheldrick. SHELXTL NT (version 5.1), Bruker Analytical X-ray Instruments Inc., Madison, Wisconsin (USA) 2001.Search in Google Scholar

[36] G. M. Sheldrick. SHELXS/L-97, Programs for Crystal Structures Determination, University of Göttingen, Göttingen (Germany) 1997.Search in Google Scholar

[37] G. M. Sheldrick, Acta Crystallogr. 1990, A46, 467–473.Search in Google Scholar

[38] G. M. Sheldrick, Acta Crystallogr. 2008, A64, 112–122.Search in Google Scholar

©2015 by De Gruyter

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- In this Issue

- Editorial

- Zeitschrift für Naturforschung B now being published by De Gruyter

- Original Communications

- “Naked” S2O72– ions – the serendipitous formation of the disulfates [HPy]2[S2O7] and [bmim][HPy][S2O7] (HPy = pyridinium; bmim = 1-Butyl-3-methylimidazolium)

- Orthoamide und Iminiumsalze, LXXXVIII. Synthese N,N,N′,N′,N″,N″-persubstituierter Guanidiniumsalze aus N,N′-persubstituierten Harnstoff/Säurechlorid-Addukten**

- The acidic ionic liquid [BSO3HMIm]HSO4: a novel and efficient catalyst for one-pot, three-component syntheses of substituted pyrroles

- The influence of alkali-metal ions on the molecular and supramolecular structure of manganese(II) complexes with tetrachlorophthalate ligands

- New triazolothiadiazole and triazolothiadiazine derivatives as kinesin Eg5 and HIV inhibitors: synthesis, QSAR and modeling studies

- Two copper(I) complexes of bi- (or tri-)pyrazolyl ligands featuring Cu3pz3 or Cu4pz4 motifs

- Synthesis of ferrocenyl aryl ethers via Cu(I)/phosphine catalyst systems

- A prenylated acridone alkaloid and ferulate xanthone from barks of Citrus medica (Rutaceae)

- Synthesis and structural characterization of substituted phenols with a m-terphenyl backbone 2,4,6-R3C6H2OH (R=2,4,6-Me3C6H2, Me5C6)

- 2-Ethyl-1-phenylindazolium hexafluorophosphate. N-heterocyclic carbene formation, rearrangement, ring-cleavage reactions, and rhodium complex formation

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- In this Issue

- Editorial

- Zeitschrift für Naturforschung B now being published by De Gruyter

- Original Communications

- “Naked” S2O72– ions – the serendipitous formation of the disulfates [HPy]2[S2O7] and [bmim][HPy][S2O7] (HPy = pyridinium; bmim = 1-Butyl-3-methylimidazolium)

- Orthoamide und Iminiumsalze, LXXXVIII. Synthese N,N,N′,N′,N″,N″-persubstituierter Guanidiniumsalze aus N,N′-persubstituierten Harnstoff/Säurechlorid-Addukten**

- The acidic ionic liquid [BSO3HMIm]HSO4: a novel and efficient catalyst for one-pot, three-component syntheses of substituted pyrroles

- The influence of alkali-metal ions on the molecular and supramolecular structure of manganese(II) complexes with tetrachlorophthalate ligands

- New triazolothiadiazole and triazolothiadiazine derivatives as kinesin Eg5 and HIV inhibitors: synthesis, QSAR and modeling studies

- Two copper(I) complexes of bi- (or tri-)pyrazolyl ligands featuring Cu3pz3 or Cu4pz4 motifs

- Synthesis of ferrocenyl aryl ethers via Cu(I)/phosphine catalyst systems

- A prenylated acridone alkaloid and ferulate xanthone from barks of Citrus medica (Rutaceae)

- Synthesis and structural characterization of substituted phenols with a m-terphenyl backbone 2,4,6-R3C6H2OH (R=2,4,6-Me3C6H2, Me5C6)

- 2-Ethyl-1-phenylindazolium hexafluorophosphate. N-heterocyclic carbene formation, rearrangement, ring-cleavage reactions, and rhodium complex formation