Abstract

Background" Autism spectrum disorder (ASD) is a serious neurodevelopmental disorder that impairs a child’s ability to communicate with others. It also includes restricted repetitive behaviors, interests and activities. Symptoms manifest before the age of 3. In the previous studies, we found structural abnormalities of the temporal lobe cortex. High spine densities were most commonly found in ASD subjects with lower levels of cognitive functioning. In the present study, we retrospectively analyzed medical records in relation to the neonatal levels of total serum bilirubin (TSB), neuron-specific enolase (NSE), creatine kinase brain band isoenzyme (CK-BB), and neonatal behavior in ASD patients from Southern China. Methods: A total of 80 patients with ASD (ASD group) were screened for this retrospective study. Among them, 34 were low-functioning ASD (L-ASD group) and 46 were high-functioning ASD (H-ASD group). Identification of the ASD cases was confirmed with a Revised Autism Diagnostic Inventory. For comparison with ASD cases, 80 normal neonates (control group) were selected from the same period. Biochemical parameters, including TSB, NSE and CK-BB in the neonatal period and medical records on neonatal behavior were collected. Results: The levels of serum TSB, NSE and CK-BB in the ASD group were significantly higher when compared with those from the control group (P < 0.01, or P < 0.05). The amounts of serum TSB, NSE and CK-BB in the L-ASD group were significantly higher when compared with those in the H-ASD group (P < 0.01, or P < 0.05). The Neonatal Behavioral Assessment Scale (NBAS) scores in the ASD group were significantly lower than that in the control group (P < 0.05). Likewise, the NBAS scores in the L-ASD group were significantly lower than that in the H-ASD group (P < 0.05). There was no association between serum TSB, NSE, CK-BB and NBAS scores (P > 0.05) in the ASD group. Conclusions: The neonatal levels of TSB, NSE and CK-BB in ASD from Southern China were significantly higher than those of healthy controls. These findings need to be investigated thoroughly by future studies with large sample.

Introduction

Autism spectrum disorder (ASD) comprises a family of developmental disabilities characterized by behavioral abnormalities that include language delays, difficulties in social interactions, and repetitive or stereotyped behaviors [1, 2]. The majority of structural brain alterations in individuals with ASD identified in postmortem studies have been found both in cortical and non-cortical regions [3–8]. In the previous studies [9, 10], we examined postmortem brains of ASD individuals and found that cortical thickness values in ASD subjects decreased significantly with age. High spine densities were associated with decreased brain weights and were most commonly found in ASD subjects with lower levels of cognitive functioning.

The current high prevalence estimates for ASD suggest that some common perinatal and/or postnatal biological factors during the neonatal period may be responsible for this increased risk, but the relationship between abnormal brain structure and these factors in ASD patient are still unknown. Therefore, identification of biomarkers associated with these alterations may provide further insights into the disease mechanisms. In this study, we retrospectively analyzed hospital medical records in relation to the neonatal levels of total serum bilirubin (TSB), neuron-specific enolase (NSE), creatine kinase brain band isoenzyme (CK-BB), and neonatal behavior in ASD from Southern China.

Materials and methods

Participants

A total of 80 patients with ASD (ASD group) were screened for this retrospective study. Out of these 80 patients, 34 were low-functioning ASD (L-ASD group) and 46 were high-functioning ASD (H-ASD group). Identification of the ASD cases was made based upon available medical and psychological hospital records from June 2003 to June 2009, and the diagnosis was confirmed with a Revised Autism Diagnostic Inventory [11]. For comparison with the ASD cases, 80 normal neonates (control group) were also selected from the same period, whose all medical records and psychological documentation were within normal limits. The characteristics of neonates in the ASD group and control group are listed in Table 1. This study was carried out in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the institutional review boards of the local Bioethics Committee in Zhongnan Hospital of Wuhan University.

Laboratory tests

Venous blood samples were collected from all neonates in the hospital. Biochemical parameters, including total serum bilirubin (TSB), neuron-specific enolase (NSE) and creatine kinase brain band isoenzyme (CKBB) were routinely measured by an automatic biochemical analyzer, radioimmunoassay and immunoluminometric assay [12, 13]. Serum fasting glucose, total cholesterol, triglycerides, alanine transaminase, aspartate transaminase, total serum protein, serum albumin, and serum prealbumin were also evaluated (data not shown).

Evaluation of neonatal behavior

The Neonatal Behavioral Assessment Scale (NBAS) developed by Brazelton et al. [14] was used to evaluate the neonatal behavior within the first week after delivery in the hospital. The NBAS was performed by 1 of 2 examiners blinded to maternal psychiatric and medical status. The NBAS includes 28 behavioral items and 18 reflex items that are administered in a particular sequence. Items of the NBAS are categorized into 7 clusters for scoring purposes; these clusters reduce the dimensionality of data. Clusters include: 1) Habituation, defined as the ability to respond to and inhibit discrete stimuli while asleep, 2) Orientation, defined as the ability to attend to visual and auditory stimuli and the quality of overall alertness, 3) Motor cluster, defined as a measure of motor performance and the quality of movements and muscle tone, 4) Range of state, defined as a measure of infant arousal and state lability, 5) Regulation of state, defined as a measure of the infant’s ability to regulate his or her state in the face of increasing levels of stimulation, 6) Autonomic stability, defined as signs of stress related to homeostatic adjustments of the central nervous system, and 7) Reflexes, defined as the number of abnormal reflexes.

Statistical methods

All data were expressed as the mean ± standard deviation (SD). Group differences were analyzed using multiple regression analysis to compare the levels of TSB, NSE, CK-BB and NBAS mean scores. Pearson’s correlation coefficient was used to analyze the association between the levels of TSB and serum NSE, as well as between the levels of TSB and serum CK-BB in the ASD group. The correlation between the levels of serum NSE and NBAS mean scores, and between the levels of serum CK-BB and NBAS mean scores in the ASD group was evaluated in the same way. All statistical analyses were performed with SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 11.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA), with a significance level set at a α = 0.05.

Results

Comparison of serum TSB, NSE, CK-BB and NBAS scores between the ASD group and the control group in the neonatal period

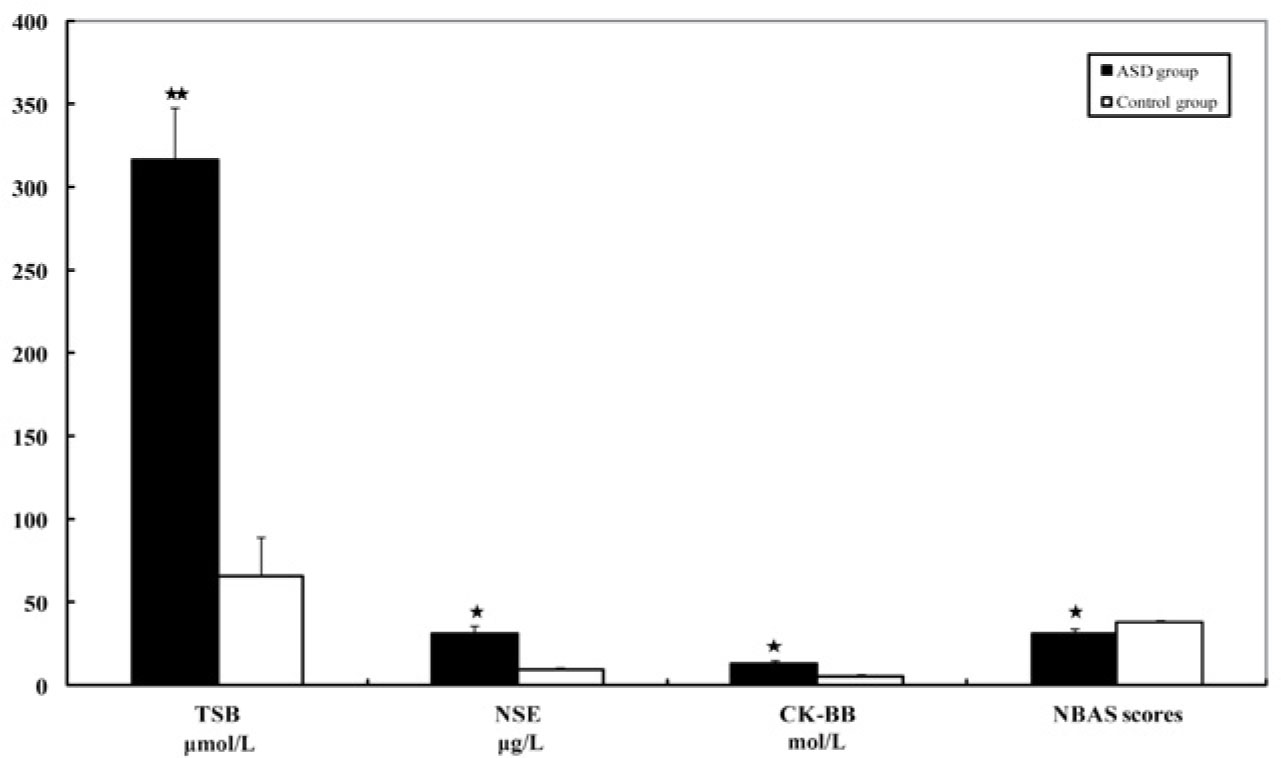

The levels of serum TSB (μmol/L), NSE (μg/L) and CK-BB (mol/L) in the ASD group were significantly higher when compared with those in the control group (P < 0.01, or P < 0.05). The NBAS scores in the ASD group were significantly lower than that in the control group (P < 0.05, Fig. 1).

Comparison of serum TSB, NSE, CK-BB and NBAS scores between the L-ASD group and the H-ASD group in the neonatal period

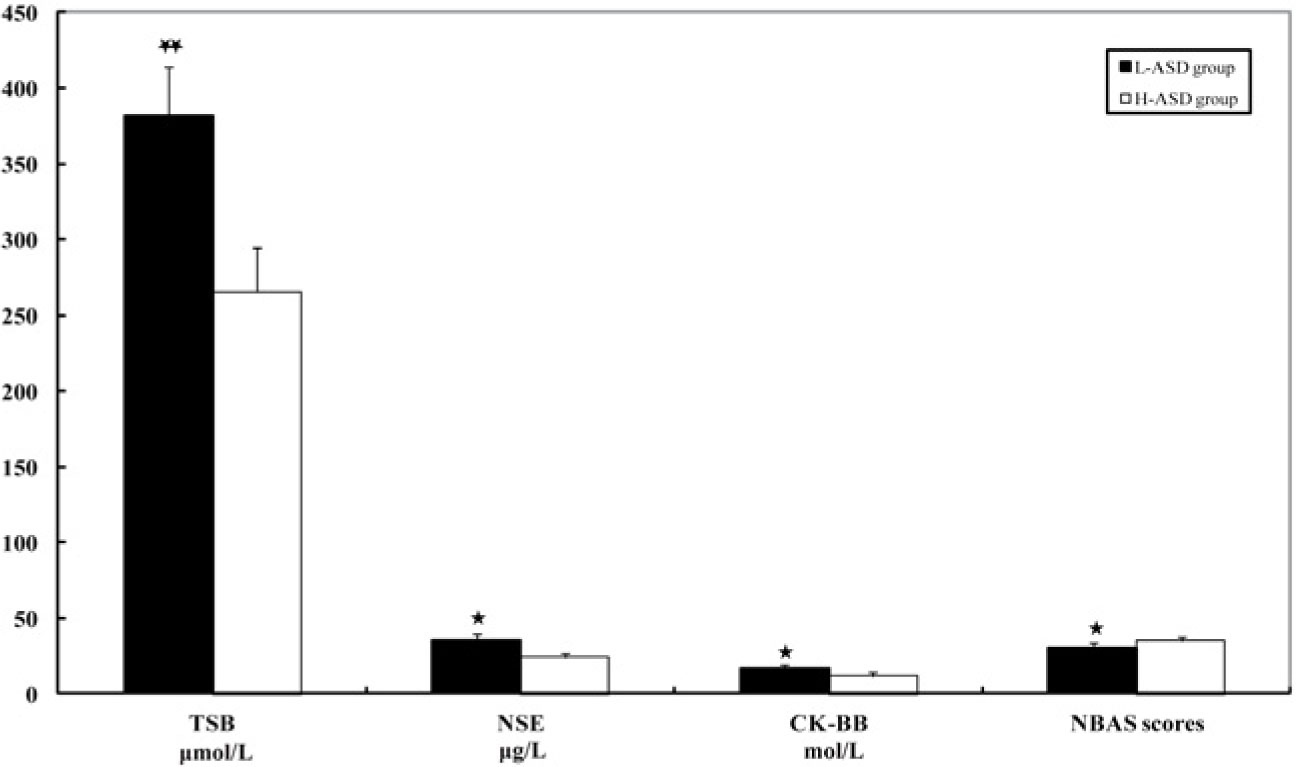

The levels of serum TSB (μmol/L), NSE (μg/L) and CK-BB (mol/L) in the L-ASD group were significantly higher when compared with those in the H-ASD group (P < 0.01, or P < 0.05). The NBAS scores in the L-ASD group was significantly lower than that in the H-ASD group (P < 0.05, Fig. 2).

Correlation analysis

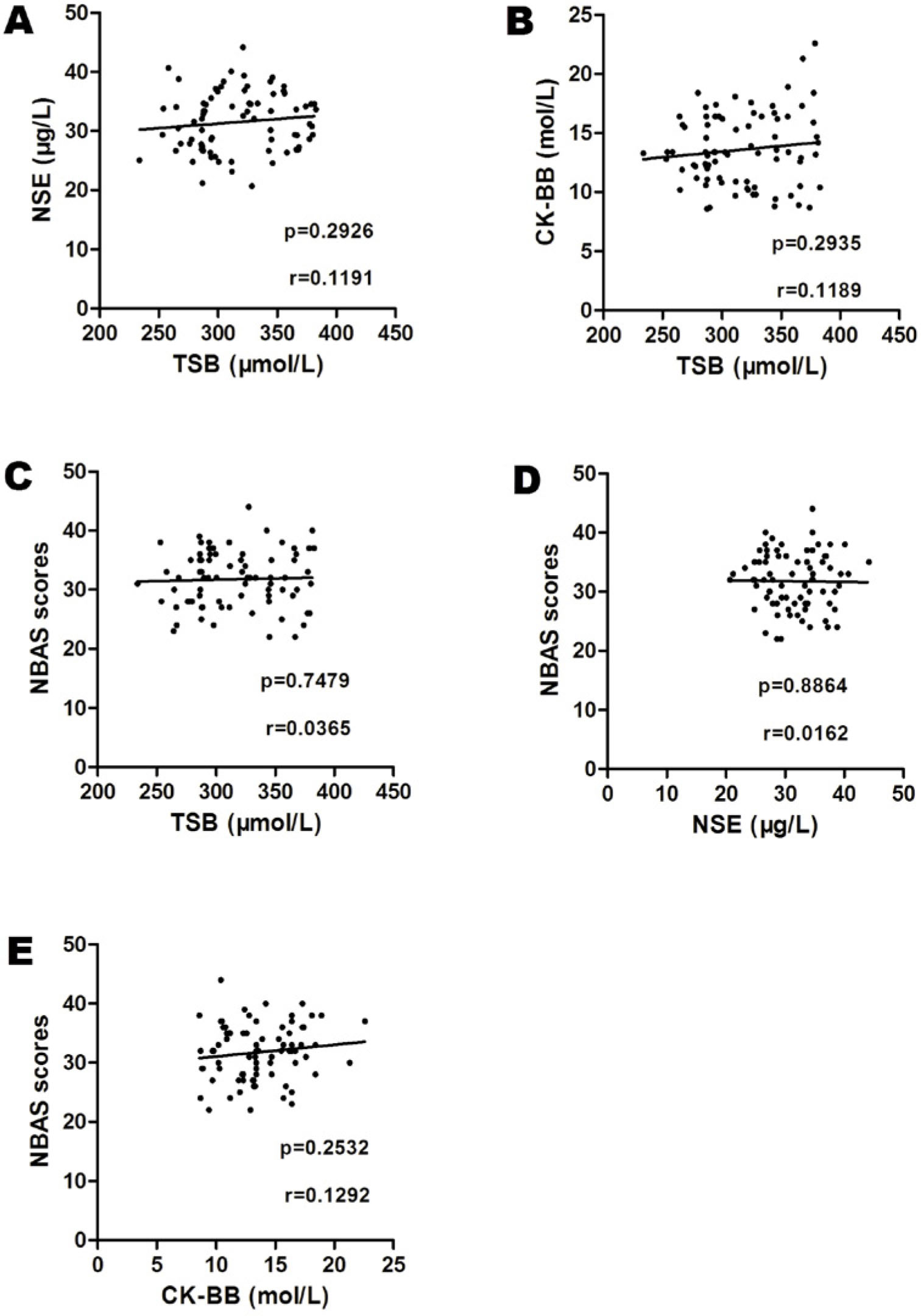

Pearson’s correlation analysis revealed no association between serum TSB, NSE, CK-BB and NBAS scores (P > 0.05) in the ASD group (Fig. 3, A-E).

Dicussion

ASD is characterized by impairments in verbal and nonverbal communication and social interaction, with onset usually occurring around the first 36 months of childhood. Latest reports estimate that ASD affects approximately 1–2 per 1,000 children, and that male/female ratio is approximately 4/1 [15, 16]. The dramatic increase in reported prevalence has encouraged an intense effort to identify early biological markers [17]. Such markers could allow for earlier identification and therapeutic intervention, contributing to improved prognosis [18]. Several investigators have postulated that exposure to some biological factors during the critical period of rapid brain growth that occurs during the second and third trimester of gestation may lead to abnormal fetal brain development in ASD.

One possible biological factor is hyperbilirubinemia. A population-based matched case-control study of 473 children with ASD children born from 1990 to 1999 in Denmark found an almost fourfold risk for ASD in infants who had hyperbilirubinaemia after birth [19]. Another population-based, follow-up study of all children born alive in Denmark between 1994 and 2004 showed that jaundice in the neonatal period increased risk of disorders of psychological development for children born at term. The excess risk of the infantile ASD was 67% [20]. A prospective study from a Canadian group showed an association with ASD in the combined moderate and severe hyperbilirubinemia group [21]. In contrast, a large case-control study nested within the cohort of singleton term infants born between 1995 and 1998 in Kaiser Permanente Northern California hospital, reported that children with any degree of bilirubin level elevation were not at increased risk of ASD [22]. A retrospective study from India showed that prematurity was associated with neonate hyperbilirubinemia in ASD [23], but this association was not found in the meta-analysis [24]. In this retrospective study, we analyzed two different ASD groups and showed that the level of TSB in the neonatal period in the ASD group was higher than in the control group. It was also significantly higher in the L-ASD group in comparison to the H-ASD group. Although the underlying mechanisms are unknown, it is currently thought that hyperbilirubinemia exert toxicity upon the basal ganglia and cerebellum, two brain regions that have been implicated as very important for the development of ASD [25].

Characteristics of the subjects in the ASD group and the control group (mean ± standard deviation)

| L-ASD group | H-ASD group | Control group | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male (female) | 18 (16) | 24 (22) | 42 (38) | |

| Gestational age (weeks) | 38.1 ±1.0 | 37.8 ± 0.8 | 38.4 ± 1.4 | > 0.05 |

| Age in days | 6.5 ± 1.5 | 5.6 ± 1.7 | 6.0 ± 1.6 | > 0.05 |

| Birth weight (kg) | 3.5 ± 0.9 | 3.6 ± 0.8 | 3.4 ± 1.0 | > 0.05 |

Serum TSB, NSE, CK-BB and NBAS scores in the ASD group and the control group (mean ± standard deviation) in the neonatal period. The amounts of serum TSB (μmol/L), NSE (μg/L) and CK-BB (mol/L) in the ASD group were significantly higher than those in the control group (*P < 0.05, **P < 0.01). The NBAS scores in the ASD group were significantly lower than in the control group. ASD, autism spectrum disorder; CK-BB, creatine kinase brain band isoenzyme; NBAS, Neonatal Behavioral Assessment Scale; NSE, neuron-specific enolase; TSB, total serum bilirubin.

Brain neurons contain a number of enolases. NSE is present predominantly in the neuron’s cytoplasm and accounts for about 75% of the total enolase subunits. The clinical interest of using NSE as marker of neuronal damage has been confirmed by several investigators (for review, see [26]). In this retrospective study, we found that the level of serum NSE in the ASD group was significantly higher than in the control group, also with significantly higher values in the H-ASD group as compared with those in the L-ASD group.

Serum TSB, NSE, CK-BB and NBAS scores in the neonatal period in the low-functioning ASD (L-ASD) group and the high-functioning ASD (H-ASD) group (mean ± standard deviation). The amounts of serum TSB (μmol/L), NSE (μg/L) and CK-BB (mol/L) in the L-ASD group were significantly higher than those in the H-ASD group (* P < 0.05, ** P < 0.01). The NBAS scores in the L-ASD group were significantly lower than those in the H-ASD group (* P < 0.05). CK-BB, creatine kinase brain band isoenzyme; NBAS, Neonatal Behavioral Assessment Scale; NSE, neuron-specific enolase; TSB, total serum bilirubin.

In the cells, the cytosolic CK enzymes consist of two subunits, which can be either B (brain type) or M (muscle type). There are, therefore, three different isoenzymes: CK-MM, CK-BB and CK-MB. Structural brain damage may produce a leakage of cytoplasmic enzymes into the blood. Therefore, biochemical marker such as CK, especially its brain-specific isoenzyme CK-BB, has been used as indicator of brain damage [27]. Al-Mosalem et al. [28] measured plasma CK in 30 Saudi autistic patients and compared those levels to 30 age-matched control samples; there were 72.35% higher levels of CK in autistic patients. Poling et al. [29] performed a retrospective study including 159 patients with autism not previously diagnosed with metabolic disorders and 94 age-matched controls, and found that serum CK level was abnormally elevated in 22 out of 47 patients with autism. Recently, Ramsey et al. [30] reported higher levels of CK-MB in the youngest ASD group and low levels in the oldest ASD group. In this retrospective study, we found that the level of serum CK-BB in the ASD group was significantly higher than that in the control group, with significantly higher levels in the H-ASD group as compared with the L-ASD group.

Correlations between serum TSB, NSE, CK-BB, and NBAS scores in the neonatal period in the ASD group (A-E). A. Correlation between the level of TSB and the amount of serum NSE (r = 0.1191, P = 0.2926). B. Correlation between the level of TSB with the amount of serum CK-BB (r = 0.1189, P = 0.2935). C. Correlation between the level of TSB and NBAS mean scores (r = 0.0365, P = 0.7479). D. Correlation between the amount of serum NSE and NBAS mean scores (r = 0.0162, P = 0.8864). E. Correlation between the amount of serum CK-BB and NBAS mean scores (r = 0.1292, P = 0.2532). ASD, autism spectrum disorder; CK-BB, creatine kinase brain band isoenzyme; NBAS, Neonatal Behavioral Assessment Scale; NSE, neuron-specific enolase; TSB, total serum bilirubin.

Developed in 1973, the NBAS, which assesses both cortical and subcortical functions, is used to evaluate neurobehavioral outcomes in the infant. It is a neurobehavioral screening tool, and will identify gross abnormalities or asymmetries. All items are administered when the baby is in the appropriate behavioral state, and there is a sequence to follow. The NBAS seeks to score the baby’s best performance, so that the examiner is working to elicit the best possible reactions from the baby. It provides information about how babies manage to protect their sleep, comfort themselves and organize their sleep and awake states. The NBAS is a reliable and useful instrument, and had been used by other studies of prenatal exposure and infant outcomes [31–33]. In this retrospective study, we found that the NBAS scores in the ASD group were significantly lower than those in the control group, again with significantly lower scores in the L-ASD group as compared with the H-ASD group. The underlying mechanisms nevertheless remain elusive and require further investigation.

Taken together, we proposed that higher levels of TSB may increase brain damage. In turn, increased brain damage may cause elevated levels of serum NSE and serum CK-BB, which may be associated with abnormal brain structure and neonatal behavior in children with ASD from Southern China. Elucidation of molecular mechanisms underlying these changes may help develop novel therapeutic interventions for neuronal protection in ASD. Unfortunately, the correlation analysis showed no association between serum TSB, NSE, CK-BB and NBAS scores in the ASD group. Therefore, these findings need to be investigated thoroughly by future studies with larger sample sizes.

Acknowledgments

Conflict of interest statement: The authors declare that they have no competing interests. The authors would like to thank all patients who participated in this study.

References

1. Banerjee S., Riordan M., Bhat MA., Genetic aspects of autism spectrum disorders: insights from animal models, Front. Cell. Neurosci., 2014, 8, 5810.3389/fncel.2014.00058Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

2. Sacrey L.A., Germani T., Bryson S.E., Zwaigenbaum L., Reaching and grasping in autism spectrum disorder: a review of recent literature, Front. Neurol., 2014, 5, 610.3389/fneur.2014.00006Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

3. Kemper T., Bauman M., Neuropathology of infantile autism, J. Neuropathol. Exp. Neurol., 1998, 57, 645–65210.1097/00005072-199807000-00001Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

4. Palmen S., van Engeland H., Hof P., Schmitz C., Neuropathological findings in autism, Brain, 2004, 127, 2572–258310.1093/brain/awh287Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

5. Casanova M.F., The neuropathology of autism, Brain Pathol., 2007, 17, 422–43310.1111/j.1750-3639.2007.00100.xSuche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

6. Casanova M.F., van Kooten I.A., Switala A.E., van Engeland H., Heinsen H., Steinbusch H.W., et al., Minicolumnar abnormalities in autism, Acta Neuropathol., 2006, 112, 287–30310.1007/s00401-006-0085-5Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

7. Williams R., Hauser S., Purpura D., DeLong G., Swisher C., Autism and mental retardation: Neuropathologic studies performed in four retarded persons with autistic behavior, Arch. Neurol., 1980, 37, 749–75310.1001/archneur.1980.00500610029003Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

8. Bailey A., Luthert P., Dean A., Harding B., Janota I., Montgomery M., et al., A clinicopathological study of autism, Brain, 1998, 121, 889–90510.1093/brain/121.5.889Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

9. Hutsler J.J., Love T., Zhang H., Histological and magnetic resonance imaging assessment of cortical layering and thickness in autism spectrum disorders, Biol. Psychiatry, 2007, 61, 449–45710.1016/j.biopsych.2006.01.015Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

10. Hutsler J.J., Zhang H., Increased dendritic spine densities on cortical projection neurons in autism spectrum disorders, Brain Res., 2010, 1309, 83–9410.1016/j.brainres.2009.09.120Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

11. Lord C., Rutter M., LeCouteur A., Autism Diagnostic Interview-Revised: a revised version of a diagnostic interview for caregivers of individuals with possible pervasive developmental disorders, J. Autism Dev. Disord., 1994, 24, 659–68510.1007/BF02172145Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

12. Vázquez M.D., Sánchez-Rodriguez F., Osuna E., Diaz J., Cox D.E., PérezCárceles M.D., et al., Creatine kinase BB and neuron-specific enolase in cerebrospinal fluid in the diagnosis of brain insult, Am. J. Forensic. Med. Pathol., 1995, 16, 210–21410.1097/00000433-199509000-00004Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

13. Kruse A., Cesarini K.G., Bach F.W., Persson L., Increases of neuron-specific enolase, S-100 protein, creatine kinase and creatine kinase BB isoenzyme in CSF following intraventricular catheter implantation, Acta Neurochir., 1991, 110, 106–10910.1007/BF01400675Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

14. Lester B., Als H., Brazelton T., Regional obstetric anesthesia and newborn behavior: a reanalysis toward synergistic effects, Child Dev., 1982, 53, 687–69210.2307/1129381Suche in Google Scholar

15. Trottier G., Srivastava L., Walker C.D., Etiology of infantile autism. A review of recent advances in genetic and neurological research, J. Psychiatry Neurosci., 1999, 24, 103–115Suche in Google Scholar

16. American Psychiatric Association., American psychiatric association, diagnostic and statistical manual-text revision (DSM IV-TR), American Psychiatric Association, Washington, DC, USA, 2000Suche in Google Scholar

17. Chakrabarti S., Fombonne E., Pervasive developmental disorders in preschool children: confirmation of high prevalence, Am. J. Psychiatr., 2005, 162, 1133–114110.1176/appi.ajp.162.6.1133Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

18. Aman M.G., Treatment planning for patients with autism spectrum disorders, J. Clin. Psychiatry, 2005, 66, 38–45Suche in Google Scholar

19. Maimburg R.D., Vaeth M., Schendel D.E., Bech B.H., Olsen J., Thorsen P., Neonatal jaundice: a risk factor for infantile autism?, Paediatr. Perinat. Epidemiol., 2008, 22, 562–56810.1111/j.1365-3016.2008.00973.xSuche in Google Scholar PubMed

20. Maimburg R.D., Bech B.H., Vaeth M., MØller-Madsen B., Olsen J., Neonatal jaundice, autism, and other disorders of psychological development, Pediatrics, 2010, 126, 872–87810.1542/peds.2010-0052Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

21. Jangaard K.A., Fell D.B., Dodds L., Allen A.C., Outcomes in a population of healthy term and near-term infants with serum bilirubin levels of > or = 325 micromol/L (> or = 19 mg/dL) who were born in Nova Scotia, Canada, between 1994 and 2000, Pediatrics, 2008, 122, 119–12410.1542/peds.2007-0967Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

22. Croen L.A., Yoshida C.K., Odouli R., Newman T.B. Neonatal hyperbilirubinemia and risk of autism spectrum disorders, Pediatrics, 2005, 115, e135–13810.1542/peds.2004-1870Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

23. Mamidala M.P., Polinedi A., Praveen Kumar P.T.V., Rajesh N., Vallamkonda O.R., Udani V., et al., Prenatal, perinatal and neonatal risk factors of autism spectrum disorder: a comprehensive epidemiological assessment from India, Res. Dev. Disabil., 2013, 34, 3004–301310.1016/j.ridd.2013.06.019Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

24. Amin S.B., Smith T., Wang H., Is neonatal jaundice associated with autism spectrum disorder: a systematic review, J. Autism Dev. Disord., 2011, 41, 1455–146310.1007/s10803-010-1169-6Suche in Google Scholar

25. Guinchat V., Thorsen P., Laurent C., Cans C., Bodeau N., Cohen D., Pre-, peri- and neonatal risk factors for autism, Acta Obstet. Gynecol. Scand., 2012, 91, 287–30010.1111/j.1600-0412.2011.01325.xSuche in Google Scholar

26. Lamers K.J., Vos P., Verbeek M.M., Rosmalen F., van Geel W.J., van Engelen B.G., Protein S-100B, neuron-specific enolase (NSE), myelin basic protein (MBP) and glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP) in cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) and blood of neurological patients, Brain Res. Bull., 2003, 61, 261–26410.1016/S0361-9230(03)00089-3Suche in Google Scholar

27. Vázquez M.D., Sánchez-Rodriguez F., Osuna E., Diaz J., Cox D.E., PérezCárceles M.D., et al., Creatine kinase BB and neuron-specific enolase in cerebrospinal fluid in the diagnosis of brain insult, Am. J. Forensic. Med. Pathol., 1995, 16, 210–21410.1097/00000433-199509000-00004Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

28. Al-Mosalem O.A., El-Ansary A., Attas O., Al-Ayadhi L., Metabolic biomarkers related to energy metabolism in Saudi autistic children, Clin. Biochem., 2009, 42, 949–95710.1016/j.clinbiochem.2009.04.006Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

29. Poling J.S., Frye R.E., Shoffner J., Zimmerman A.W., Developmental regression and mitochondrial dysfunction in a child with autism, Child Neurol., 2006, 21, 170–17210.1177/08830738060210021401Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

30. Ramsey J.M., Guest P.C., Broek J.A., Glennon J.C., Rommelse N., Franke B., et al., Identification of an age-dependent biomarker signature in children and adolescents with autism spectrum disorders, Mol. Autism, 2013, 4, 2710.1186/2040-2392-4-27Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

31. Lester B.M., Als H., Brazelton T.B., Regional obstetric anesthesia and newborn behavior: a reanalysis toward synergistic effects, Child Dev., 1982, 53, 687–69210.2307/1129381Suche in Google Scholar

32. Engel S.M., Zhu C., Berkowitz G.S., Calafat A.M., Silva M.J., Miodovnik A., et al., Prenatal phtalate exposure and performance on the Neonatal Behavioral Assessment Scale in a multiethnic birth cohort, Neurotoxicology, 2009, 30, 522–52810.1016/j.neuro.2009.04.001Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

33. Engel S.M., Berkowitz G.S., Barr D.B., Teitelbaum S.L., Siskind J., Meisel S.J., et al., Prenatal organophosphate metabolite and organochlorine levels and performance on the Brazelton Neonatal Behavioral Assessment Scale in a multiethnic pregnancy cohort, Am. J. Epidemiol., 2007, 165, 1397–140410.1093/aje/kwm029Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

© 2016 Meng-na Lv et al., published by De Gruyter Open

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 3.0 License.

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Research Article

- Early predictors and prevention for post-stroke epilepsy: changes in neurotransmitter levels

- Research Article

- The neonatal levels of TSB, NSE and CK-BB in autism spectrum disorder from Southern China

- Research Article

- Role of cerebral blood flow in extreme breath holding

- Review Article

- Teneurins, TCAP, and latrophilins: roles in the etiology of mood disorders

- Review Article

- How air pollution alters brain development: the role of neuroinflammation

- Research Article

- Allelic distribution of BDNF Val66Met polymorphism in healthy Romanian volunteers

- Review Article

- The serotonergic system and cognitive function

- Research Article

- Blocking mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) improves neuropathic pain evoked by spinal cord injury

- Research Article

- Emotional conflict occurs at a late stage: evidence from the paired-picture paradigm

- Research Article

- Sleep-wake patterns and sleep quality in urban Georgia

- Research Article

- Presenilin 2 overexpression is associated with apoptosis in Neuro2a cells

- Research Article

- No association of AQP4 polymorphisms with neuromyelitis optica and multiple sclerosis

- Research Article

- Serum C-reactive protein, fibrinogen and D-dimer in patients with progressive cerebral infarction

- Research Article

- Is the left uncinate fasciculus associated with verbal fluency decline in mild Alzheimer's disease?

- Research Article

- High fibrosis indices in cerebrospinal fluid of patients with shunt-dependent post-traumatic chronic hydrocephalus

- Review Article

- Enhancing attention in neurodegenerative diseases: current therapies and future directions

- Research Article

- Prediction of the long-term efficacy of STA-MCA bypass by DSC-PI

- Research Article

- Cortical function in Alzheimer’s disease and frontotemporal dementia

- Research Article

- More than a mere sequence: predictive processing of wh-dependencies in early bilinguals

- Research Article

- Blocking PAR2 alleviates bladder pain and hyperactivity via TRPA1 signal

- Research Article

- Gene expression profiling of the dorsolateral and medial orbitofrontal cortex in schizophrenia

- Research Article

- Cerebral mTOR signal and pro-inflammatory cytokines in Alzheimer’s disease rats

- Research Article

- Effects of ulinastatin on global ischemia via brain pro-inflammation signal

- Research Article

- Comparison of MSC-Neurogenin1 administration modality in MCAO rat model

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Research Article

- Early predictors and prevention for post-stroke epilepsy: changes in neurotransmitter levels

- Research Article

- The neonatal levels of TSB, NSE and CK-BB in autism spectrum disorder from Southern China

- Research Article

- Role of cerebral blood flow in extreme breath holding

- Review Article

- Teneurins, TCAP, and latrophilins: roles in the etiology of mood disorders

- Review Article

- How air pollution alters brain development: the role of neuroinflammation

- Research Article

- Allelic distribution of BDNF Val66Met polymorphism in healthy Romanian volunteers

- Review Article

- The serotonergic system and cognitive function

- Research Article

- Blocking mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) improves neuropathic pain evoked by spinal cord injury

- Research Article

- Emotional conflict occurs at a late stage: evidence from the paired-picture paradigm

- Research Article

- Sleep-wake patterns and sleep quality in urban Georgia

- Research Article

- Presenilin 2 overexpression is associated with apoptosis in Neuro2a cells

- Research Article

- No association of AQP4 polymorphisms with neuromyelitis optica and multiple sclerosis

- Research Article

- Serum C-reactive protein, fibrinogen and D-dimer in patients with progressive cerebral infarction

- Research Article

- Is the left uncinate fasciculus associated with verbal fluency decline in mild Alzheimer's disease?

- Research Article

- High fibrosis indices in cerebrospinal fluid of patients with shunt-dependent post-traumatic chronic hydrocephalus

- Review Article

- Enhancing attention in neurodegenerative diseases: current therapies and future directions

- Research Article

- Prediction of the long-term efficacy of STA-MCA bypass by DSC-PI

- Research Article

- Cortical function in Alzheimer’s disease and frontotemporal dementia

- Research Article

- More than a mere sequence: predictive processing of wh-dependencies in early bilinguals

- Research Article

- Blocking PAR2 alleviates bladder pain and hyperactivity via TRPA1 signal

- Research Article

- Gene expression profiling of the dorsolateral and medial orbitofrontal cortex in schizophrenia

- Research Article

- Cerebral mTOR signal and pro-inflammatory cytokines in Alzheimer’s disease rats

- Research Article

- Effects of ulinastatin on global ischemia via brain pro-inflammation signal

- Research Article

- Comparison of MSC-Neurogenin1 administration modality in MCAO rat model