Heterologous expression of a plant WRKY protein confers multiple stress tolerance in E. coli Bir bitkinin heterolog ifadesi WRKY proteini çoklu stres yaratır E. coli’de tolerans

Abstract

Objective

OsWRKY71, a WRKY protein from rice, is reported to function during biotic stresses. It is requisite to further enquire the efficiency and mechanism of OsWRKY71 under various environmental stresses. Stress indicators such as salt, cold, heat, and drought were studied by overexpressing the OsWRKY71 in E. coli.

Materials and methods

DNA binding domain containing region of OsWRKY71 was cloned and expressed in E. coli followed by exposure to stress conditions. OsWRKY71 was also assessed for its role in abiotic stresses in rice by qPCR.

Results

Recombinant E. coli expressing OsWRKY71 was more tolerant to stresses such as heat, salt and drought in spot assay. The tolerance was further confirmed by monitoring the bacterial growth in liquid culture assay demonstrating that it encourages the E. coli growth under salt, drought, and heat stresses. This tolerance may be the consequence of OsWRKY71 interaction with the promoter of stress related genes or with other proteins in bacteria. The RT-qPCR analysis revealed the up-regulation of OsWRKY71 gene in rice upon interaction to cold, salt, drought and wounding with maximum up-regulation against salinity.

Conclusion

Thus, the defensive role of OsWRKY71 may accord to the development and survival of plants during different environmental stresses.

Öz

Amaç

Pirinçten elde edilen bir WRKY proteini olan OsWRKY71’in biyotik stresler sırasında işlev gördüğü bildirilmektedir. OsWRKY71’in verimliliğinin ve mekanizmasının çeşitli çevresel stresler altında daha da sorgulanması gerekmektedir. Tuz, soğuk, sıcak ve kuraklık gibi stres göstergeleri, OsWRKY71’in E. coli’ de aşırı ifade edilmesiyle çalışılmıştır.

Gereç ve Yöntem

OsWRKY71’in DNA bağlama bölgesini içeren domeni klonlandı ve E. coli’ de ifade edildi, ardından stres şartlarına maruz bırakıldı. OsWRKY71 ayrıca, pirinçteki abiyotik streslerdeki rolü için qPCR ile değerlendirildi.

Bulgular

OsWRKY71’i eksprese eden rekombinant E. coli, sıcaklık, tuz ve kuraklık gibi kuraklık gibi streslere karşı daha toleranslıydı. Tolerans ayrıca, E. coli’ nin tuz, kuraklık ve sıcaklık stresleri altında büyümesinin teşvik edildiğini gösteren sıvı kültür testinde bakteri üremesinin izlenmesi ile kanıtlandı. Bu tolerans, OsWRKY71’in stresle ilişkili genlerin promotoru veya bakterilerdeki diğer proteinlerle etkileşiminin sonucu olabilir. RT-qPCR analizi, soğuk, tuz, kuraklık ve yaralama ile etkileşimin ardından pirinçte OsWRKY71 geninin yukarı regülasyonunu ortaya koydu; maksimum yukarı regülasyon tuzluluğa karşı görüldü.

Sonuç

Bu nedenle, OsWRKY71’in savunma rolü, farklı çevresel stresler sırasında bitkilerin gelişmesi ve hayatta kalması ile bağdaşabilir.

Introduction

Contrasting to animals, plants are unable to move away from extreme environmental stresses for instance cold, drought, salinity, and heat. These abiotic stresses create a severe risk to crop plants growth and productivity and ultimately affect the crop yield in a negative way. Plants have developed different adaptive strategies to lessen the unfavorable consequences by changing their molecular and cellular functions, for example altering the gene expression and consequent action of their gene products [1]. Of particular interest are the transcription factors intricated in inducing the plant reaction to environmental pressures by activating or repressing the target genes transcription by associating with cis-acting components in their promoter regions [2]. One class of transcription factors exclusively present in plants and is implicated in responding to a stress condition, is the WRKY group of proteins that interact with the conserved DNA sequence motif (TTGACT/C) [3]. The most noticeable characteristic of WRKY transcription factors is the presence of WRKY domain, composed of 60 amino acids, which contains signature motif WRKYGQK at the N-terminus, and a unique C–C–H–H/C type zinc-finger domain at the C-terminus. WRKY transcription factors are distributed into three sets on the basis of type of zinc finger domain and copies of WRKY domains [4]. Many WRKY encoding genes have been known to various plants, for instance, 125 WRKY genes are identified in rice and 74 WRKY genes in Arabidopsis [5], [6].

So far, numerous WRKY transcription factors were observed to be concerned in a plant with emphasis on providing resistance to pathogen infection. For example, AtWRKY18, AtWRKY40, and AtWRKY60 negatively control the resistance against Pseudomonas syringae and the barley WRKY proteins HvWRKY1 and HvWRKY2 negatively regulate the basal reaction against Blumeria graminis [7], [8]. OsWRKY45 increases the tolerance against Xanthomonas oryzae pathovar oryzae (Xoo) and Magnaporthe oryzae in rice [9], and OsWRKY28 improves the rice vulnerability to M. oryzae [10]. Decrease in the expression of these rice WRKYs improves the tolerance against Xoo and M. oryzae [11].

Remarkably, many WRKY genes are responsible for coordinating various biological processes such as AtWRKY33 is found to respond to pathogen attack, salinity and high temperature [12], and a pepper WRKY, CaWRKY40, is involved in providing tolerance against heat stress and Ralstonia solanacearum [13]. The indicated results proposed that WRKY proteins can connect several physiological processes by serving as knots although the functions of several members are still poorly understood.

Up-regulation of OsWRKY71 is observed against numerous signaling molecules involved in defense processes including salicylic acid, methyl jasmonate, and biotic elicitors. Consequently, over-expression of OsWRKY71 expands protection from Xoo and wounding in rice [10], [14]. Conversely, OsWRKY71 is also involved in transcriptional repression of genes responsive to gibberellin [15]. In the present study, a preliminary study was conducted to decipher the role of OsWRKY71 in abiotic stresses. To date, the role of OsWRKY71 in abiotic stresses is not fully elaborated. The current study was an endeavor to explore the role of OsWRKY71 transcription factor in abiotic stresses including cold, salt, heat and drought. Cloning of OsWRKY71 DNA binding domain containing region was performed followed by its functional characterization in E. coli against abiotic stresses. The data suggest that OsWRKY71 may be exploited as yet another target for making plants resistant to abiotic stresses.

Materials and methods

In silico analysis

The OsWRKY71 gene sequence was used as a query in BLAST with NCBI database for homology search. CLUSTALW (http://www.genome.jp/tools/clustalw/) online tool was used to align the protein sequences showing similarity with OsWRKY71 [16].

Plant materials

A stress tolerant variety of rice (Oryza sativa L. ssp. Indica) KS282 was used in present study, derived from Basmati370/CM70 [17]. The rice seeds were received from National Agricultural Research Centre (NARC) Islamabad. KS282 is derived from Basmati370/CM70, salt tolerant variety. Seeds were grown on MS medium (half-strength) and placed at 25°C in plant growth room for 10 days.

Cloning and over-expression of OsWRKY71 in E. coli

Ten-day old rice seedlings were used to extract whole RNA using the RNeasy mini kit from QIAGEN according to the instructions provided by the manufacturer. Then cDNA was synthesized using RevertAid Premium Reverse Transcriptase (Thermo Scientific, Waltham, USA) using commercially synthesized Oligo (dT) 18 primer. DNA binding domain containing region of OsWRKY71 was PCR amplified from cDNA using specific primers [Forward 5’-CGCGGATCCATGCGCATCCGCGAGGAG-3’ (BamHI), reverse 5’-CCGCTCGAGTCAGGCGCTCTTGCCGGA-3’ (XhoI)]. The specific sequence for restriction enzyme is underlined in the primer sequence. The amplified PCR product was gel purified, subjected to restriction digestion with BamH1 and XhoI followed by ligation in between BamHI and XhoI sites of the pGEX4T-1 vector (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech, Little Chalfont, UK). The pGEX4T-1 vector is designed for bacterial expression under the control of the tac promoter. The vector contains lacIq gene, the product of which interacts with the operator region and avoids its expression until its expression is induced by IPTG, hence upholding firm regulation on expression of the sequence inserted into vector. The wanted recombinant plasmids (pGEX4T-OsWKRY71) were recognized by restriction digestion, PCR amplification, and commercial sequencing. The recombinant plasmid (pGEX4T-OsWRKY71) and vector alone (pGEX4T-1) were subjected to transformation in the BL21 cells [18]. The BL21 cells transformed with pGEX4T-1 vector were used as a control. The expression of the recombinant product was encouraged using 1.0 mM IPTG in culture media for 6 h at 37°C and examined by SDS-PAGE.

Functional study of recombinant bacterial cells against multiple abiotic stresses

Spot assay and liquid culture assay were carried out to study the behavior of bacterial cells under different abiotic stresses as described by Yadav et al. [18] with certain alterations as described below.

Spot assay

The influence of NaCl, mannitol, low and high temperatures was examined on the growth of E. coli cells harboring recombinant (pGEX4T-OsWRKY71) and control vector (pGEX4T-1). Escherichia coli cells were allowed to grow at 37°C in the LB medium until OD600 extended 0.6. Subsequently expression of recombinant protein was encouraged by adding 1 mM IPTG and culturing was continued for another 4 h. The OD600 of the culture was then adjusted to 1, followed by 50-, 100- and 200-fold dilution. Each dilution (10 μL) was speckled on simple LB plates, and LB plates containing NaCl (400 mM, 500 mM and 600 mM) and mannitol (500 mM, 800 mM and 1 M). For cold and heat analysis, bacterial cultures were kept at 4°C and 50°C respectively, and samples were collected after 2, 4, 6 and 8 h in case of cold stress and after 1, 2 and 3 h of heat treatment. The samples were diluted by 50-, 100- and 200-fold, and 10 μL of each sample were speckled on LB agar plates supplemented with IPTG. All these plates were left at 37°C overnight and photographs were taken in the morning. The experiment was performed three times.

Liquid culture assay

Recombinant E. coli cells were allowed to grow in the same way as for spot assay followed by dilution of cultures to OD600 0.6. Then, 1 mM IPTG was added in 10 mL medium containing 400 μL bacterial cultures, 500 mM NaCl, 800 mM mannitol and incubated at 37°C. The sample was taken after every 2 h until 12 h followed for measurement of bacterial growth at OD600. For cold and heat stress, cells were grown at 4°C and 50°C respectively followed by harvesting after every 2 h until 12 h and then OD600 was estimated. The experiment was performed thrice, and Microsoft Excel was used to calculate the mean, standard deviation, and standard error. Changes in OD of liquid bacterial cultures were examined for significant change after each time duration by one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA).

Stress treatments and real time PCR

To study the expression of the OsWRKY71 gene, 10-day old seedlings were exposed to different abiotic stresses. Six seedlings were used in each stress treatment and the experiment was repeated twice. Untreated seedlings were taken as the experimental control. The following stress treatments were applied on 10-day old seedlings: (1) Drought stress; seedlings were placed on aluminum foil till visible leaf rolling appeared in the plants [19]. (2) Cold stress; the seedlings were transferred to 4°C for 48 h, moved to the control environment, and harvested after 24 h [20]. (3) Salt treatment; the seedlings were immersed in a beaker containing 200 mM NaCl for 3 h at 28±1°C [19]. (4) Heat treatment; the seedlings were subjected to 42°C for 6 h [21]. (5) Wounding stress; the seedlings were cut into pieces and left in water at room temperature [21]. The samples were collected separately and stored at –80°C until analysis.

Total RNA was extracted from control and stress treated rice seedlings using the RNeasy Plant Mini Kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany). Brilliant II SYBR Green QRT-PCR Master Mix Kit (Agilent Technologies, CA, USA) was employed in RT-qPCR reactions. RT-qPCR reaction was prepared using OsWRKY71 (F-5′TGGATTAGCACCCAGCCTTC3′, R-5′AGGCTGCTGGTGAAAGAAGT3′) and actin gene primers (F-5′GAAGATCACTGCCTTGCTCC3′ and R-5′CGATAACAGCTCCTCTTGGC3′) on extracted RNA templates. Primer designing and their properties were checked using different bioinformatics tools i.e. Integrated DNA technology oligoanalyzer (www.idtdna.com) and/or Primer BLAST (www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/primerBLAST). Sequences spanning the two exons junction were chosen to enhance specificity. PCR conditions used were: one cycle at 50°C for reverse transcription followed by polymerase stimulation at 95°C for 3 min and 40 cycles of PCR at 95°C for 30 s, 53°C for 1 min and 72°C for 30 s. The relative change in transcript level was calculated using 2−ΔΔCT method [22] with actin as an internal standard to determine relative expression levels [23]. RT-qPCR assays were performed twice (biological replicates), and each sample had three replicates (technical replicates). Student’s t-test was used to detect difference between stress treatments and respective controls.

Results

Cloning and sequence analysis of OsWRKY71

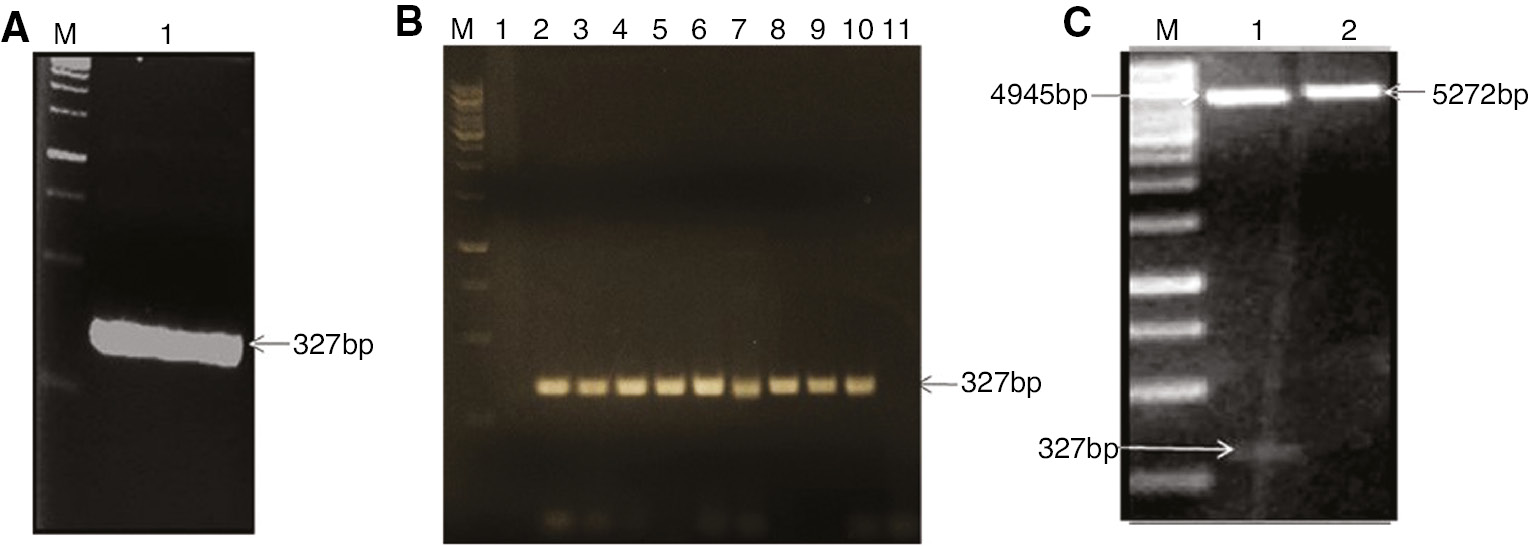

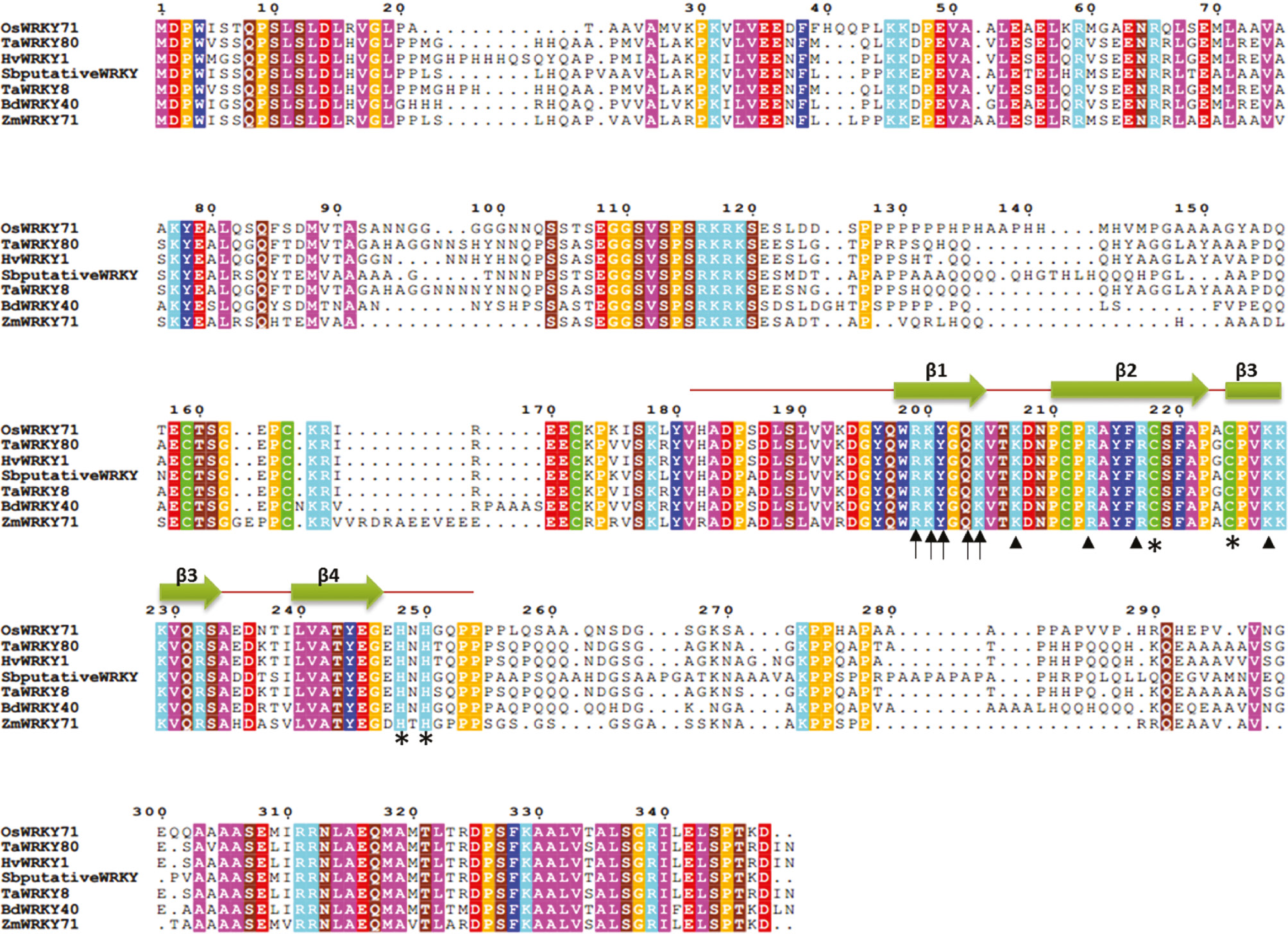

A 327 bp fragment of OsWRKY71 DNA binding domain was amplified from rice cDNA (Figure 1A), purified from gel and ligated with BamHI and XhoI digested pGEX4T-1 vector. Colony PCR was performed on selected 10 colonies and presence of 327 bp band confirmed the positive clones (Figure 1B). Cloned gene was also confirmed by restriction digestion and commercial sequencing. Plasmids extracted from overnight grown cultures of positive colonies were digested with BamHI and XhoI and checked on 1% agarose gel. Presence of 327 bp band demonstrated the successful ligation and transformation (Figure 1C). The upper ~4.5 kb fragment in lane 1 was of linearized pGEX-4T 1. The translated protein sequence of OsWRKY71 gene was subjected to BLAST search for finding homology with already available sequences in NCBI databases. The OsWRKY71 ortholog sequences were retrieved and multiple sequence alignment was carried out using CLUSTALW tool (Figure 2). It was observed that the DNA binding domain sequence is highly conserved in all WRKY proteins. Secondary structure was predicted by using PSIPRED and revealed that the DNA binding domain of OsWRKY71 is made up of ~60 amino acid residues extending from Valine191 to Proline252 and comprises of four β-sheets. It includes a single, highly conserved WRKY domain at the N terminus and zinc finger like structure at its C terminus (C-X5-C-X23-H-X1-H) which means that it belongs to group IIA [4] (Figure 2).

Cloning of OsWRKY71 DNA binding domain.

(A) PCR optimization of OsWRKY71 at 66°C. (B) Colony PCR (Lane M: 1 kb DNA ladder, Lane 1–10: Colonies 1–10, Lane 11: -ve control). (C) Restriction digestion of pGEX-OsWRKY71 (Lane 1: Restricted plasmid, Lane 2: Uncut plasmid).

Protein sequence alignment of OsWRKY71 (XP_015627417.1) structure of DNA binding domain.

WRKY proteins from different plant members including WRKY from T. aestivum (AFW98256.1; ABC61128.1), H. vulgare (AAS48544.1), S. bicolor (XP_002451666.1), B. distachyon (XP_003570741.1) and Z. mays (PWZ19903.1) were analyzed by TCOFFEE. Conserved residues are shaded in different colors. Green arrows indicate the four β strands of DNA binding domain in the C terminus of OsWRKY71. Arrows represent the key residues involve in making contact with DNA major groove. Arrowheads denote residues that make contact with DNA backbone. Asterisks represent cysteine and histidine residues of zinc finger like motifs in WRKY DNA binding domain.

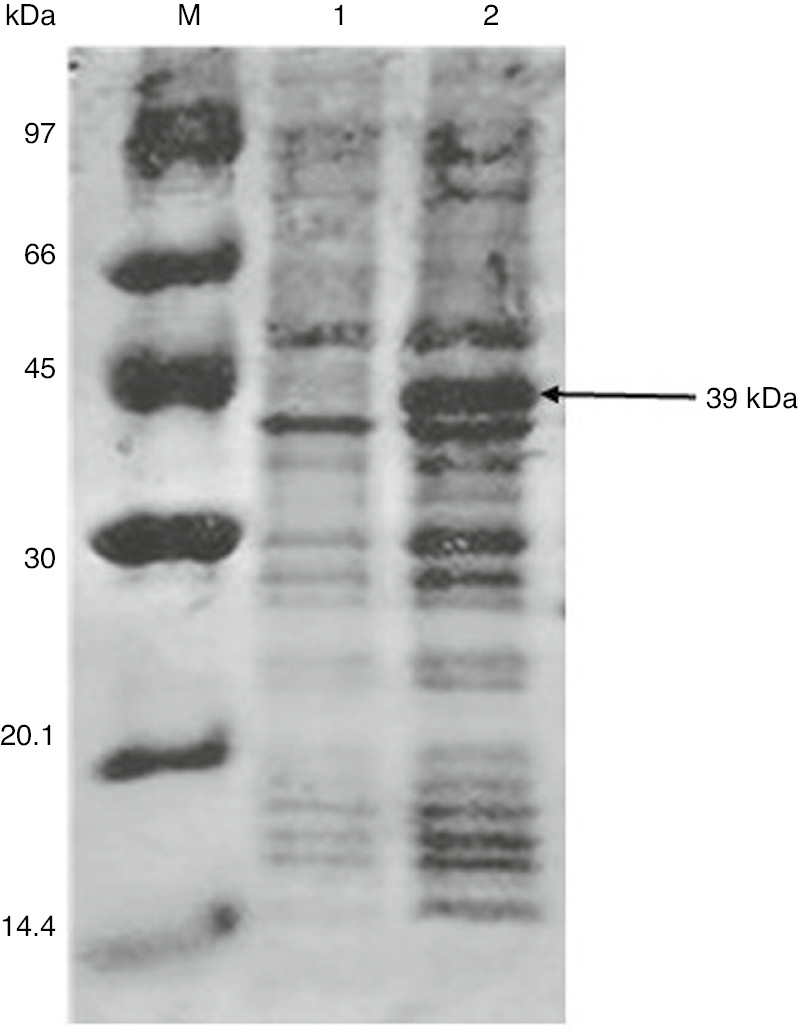

Expression of OsWRKY71 by SDS PAGE

OsWRKY71 was expressed in fusion with GST protein at the N-terminus having a size of 39 kDa. The expression of recombinant protein (pGEX4T-OsWRKY71) was induced with IPTG and was allowed the protein to express for 4 h at 37°C (Figure 3).

Expression of OsWRKY71 in E. coli.

Lane M: marker, Lane 1: uninduced BL21, Lane 2: induced BL21.

Overexpression of OsWRKY71 confers abiotic stress tolerance in E. coli

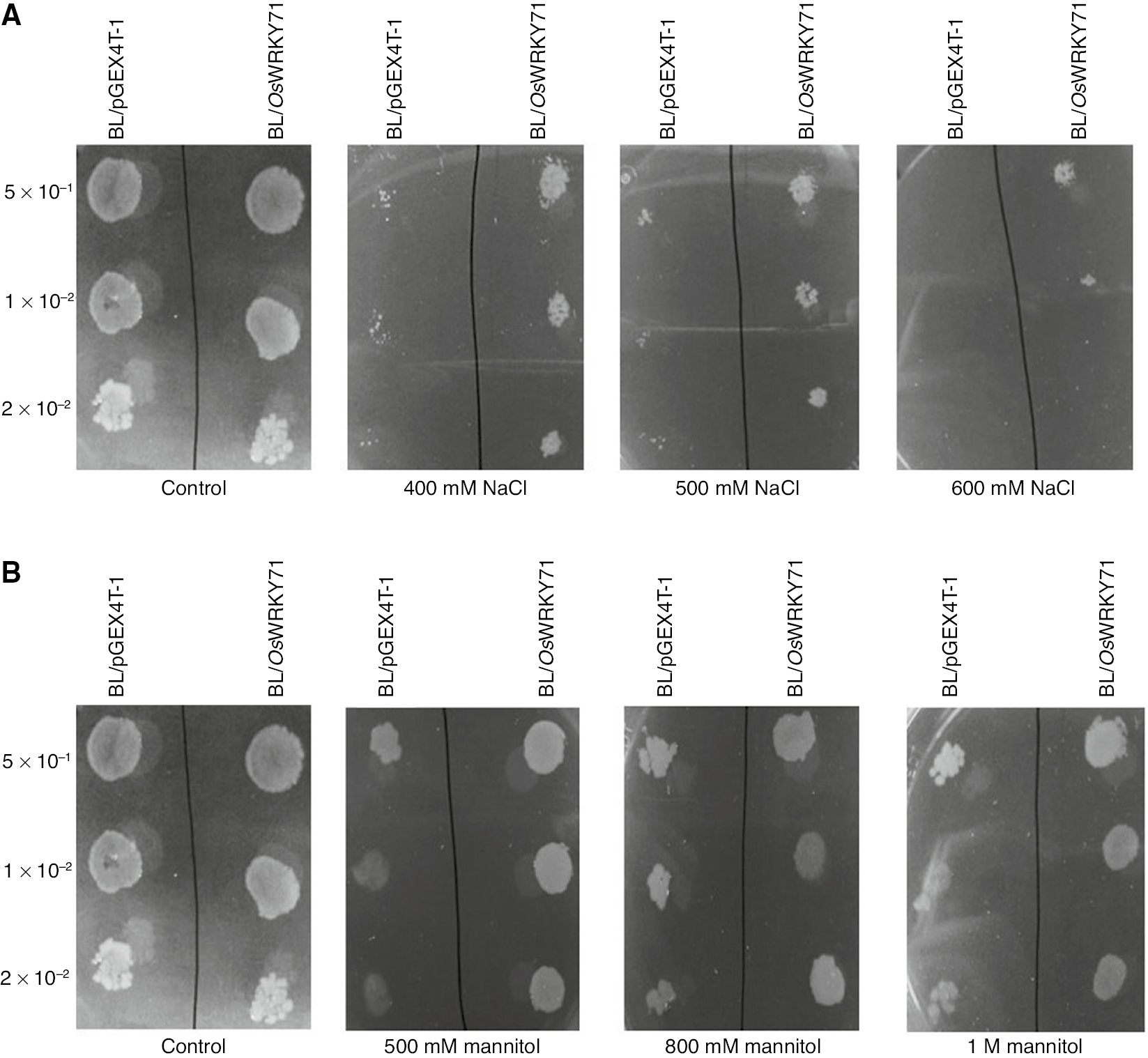

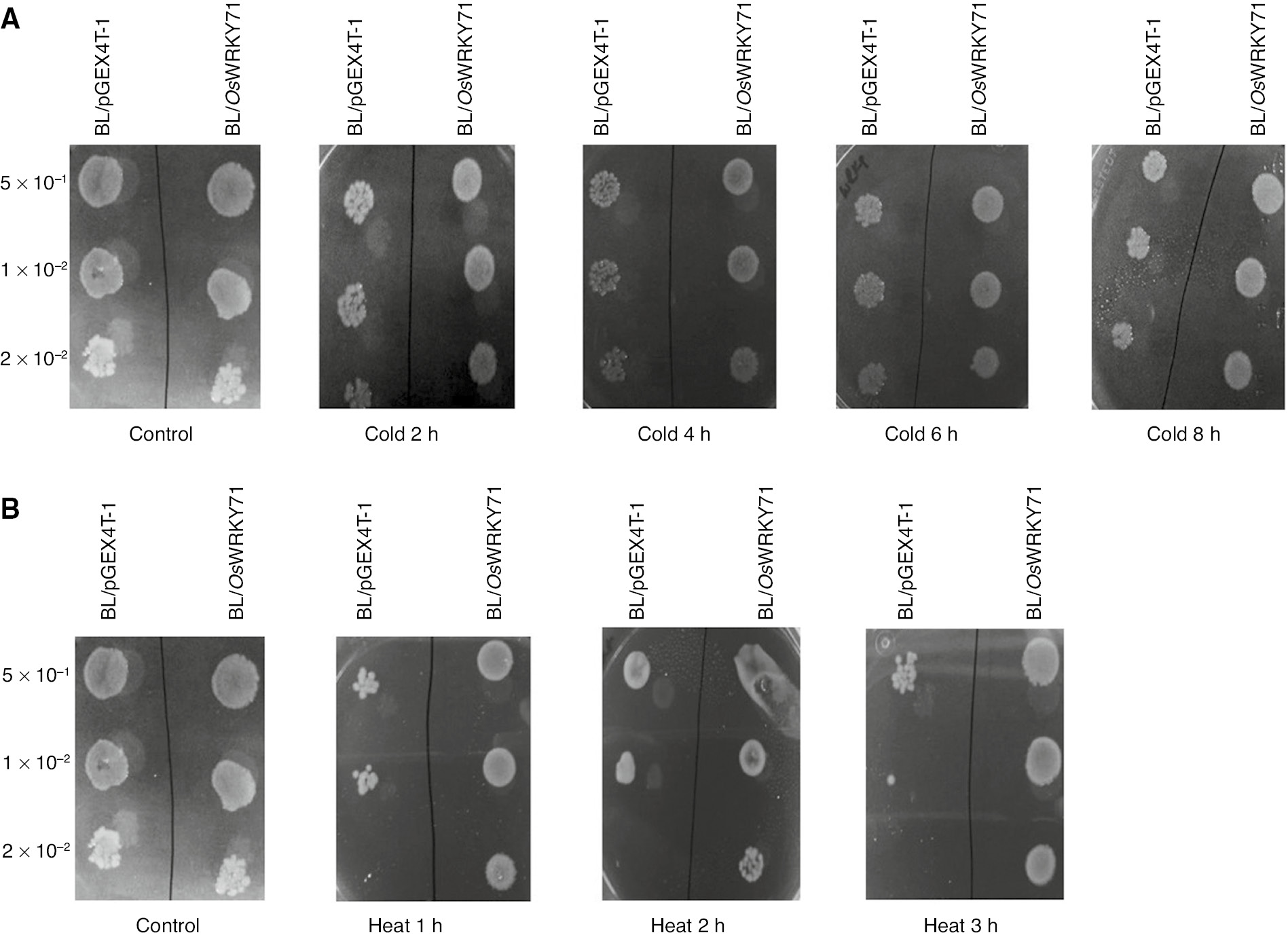

In order to assess the function of expressed OsWRKY71 protein in salt stress condition, the effect of high NaCl concentration was examined. BL/pGEX4T-1, BL/OsWRKY71 containing cells have same growth pattern on standard LB plates. But when plates were supplemented with various concentrations of NaCl and mannitol, there were visible differences with reference to growth and natural assortment (Figure 4). Likewise, OsWRKY71-expressing bacteria were able to bear the high temperature stress in comparison with the control cells. Whereas, there was no clear differences in growth of control and recombinant bacteria in response to cold shock (Figure 5).

Spot assay of BL/pGEX4T-1 and BL/OsWRKY71 recombinant cells.

Cultures were induced with 1 mM IPTG. OD was adjusted to OD600=1. Then 10 μL of 50-, 100- and 200-fold diluted bacterial suspension was spotted on LB plates. (A) Spot assay of BL/OsWRKY71 and BL/pGEX4T-1 on the LB plates supplemented with various concentrations of NaCl containing 400, 500 and 600 mM NaCl for salt stress. (B) Spot assay of BL/OsWRKY71 and BL/pGEX4T-1 on the LB plates supplemented with various concentrations of mannitol containing 500, 800 mM and 1 M mannitol for desiccation.

Spot assay of BL/pGEX4T-1 and BL/OsWRKY71 recombinant cells.

Cultures were induced with 1 mM IPTG. OD was adjusted to OD600=1. Then 10 μL of 50-, 100- and 200-fold diluted bacterial suspension was spotted on LB plates. (A) Spot assay of BL/OsWRKY71 and BL/pGEX4T-1 on the LB plates. Samples were spotted after 2, 4, 6 and 8 h of cold stress. (B) Spot assay of BL/OsWRKY71 and BL/pGEX4T-1 on the LB plates. Samples were spotted after 1, 2 and 3 h of heat stress.

In high salt concentration, the survival of OsWRKY71 transformed bacterial cells was considerably superior with improved persistence in comparison to untransformed cells. Each plate supplemented with 400–600 mM NaCl exhibited different numbers of bacterial colonies, and survival of the recombinant cells was affectedly better than that of non-recombinant cells. OsWRKY71-expressing bacterial cultures diluted by 50- and 100-fold persisted the 600 mM NaCl concentration, while there was no growth when bacterial culture was diluted up to 200-fold (Figure 4A). The outcome proposed that the development of control cells was stopped in high salt stress whereas this stress was better tolerated by cells expressing OsWRKY71.

The response of OsWRKY71 protein in drought was examined by accompanying the growth media with different concentrations of mannitol to create water stress for OsWRKY71-transformed and untransformed E. coli. The growth of recombinant cells was remarkably better as compared to control cells in mannitol-induced dehydration (Figure 4B). This outcome suggested that the expression of the OsWRKY71 gene expression has provided tolerance to E. coli cells against drought stress.

With the aim of identifying the outcome of OsWRKY71 overexpression on the growth of E. coli cells against low and high-temperature, cultures induced with IPTG were moved to 4°C and 50°C respectively. After employing the temperature stresses for different time intervals, the number of cells were compared in diluted cultures. Number of control cells was less as compared to BL/OsWRKY71 but growth rate was stagnant for both control and BL/OsWRKY71 cells after 2, 4, 6 and 8 h of cold treatment (Figure 5A). Heat stress was used to evaluate the response of OsWRKY71. Untransformed cells showed minor growth after 1, 2 and 3 h of heat stress in 50- and 100-fold dilutions, but no sign of growth was observed in 200-fold diluted control bacterial cells. In comparison, OsWRKY71 transformed cells indicated better survival till 3 h successively followed by high-temperature shock (Figure 5B). These results suggested that the OsWRKY71 gene significantly increased the tolerance to high-temperature stresses.

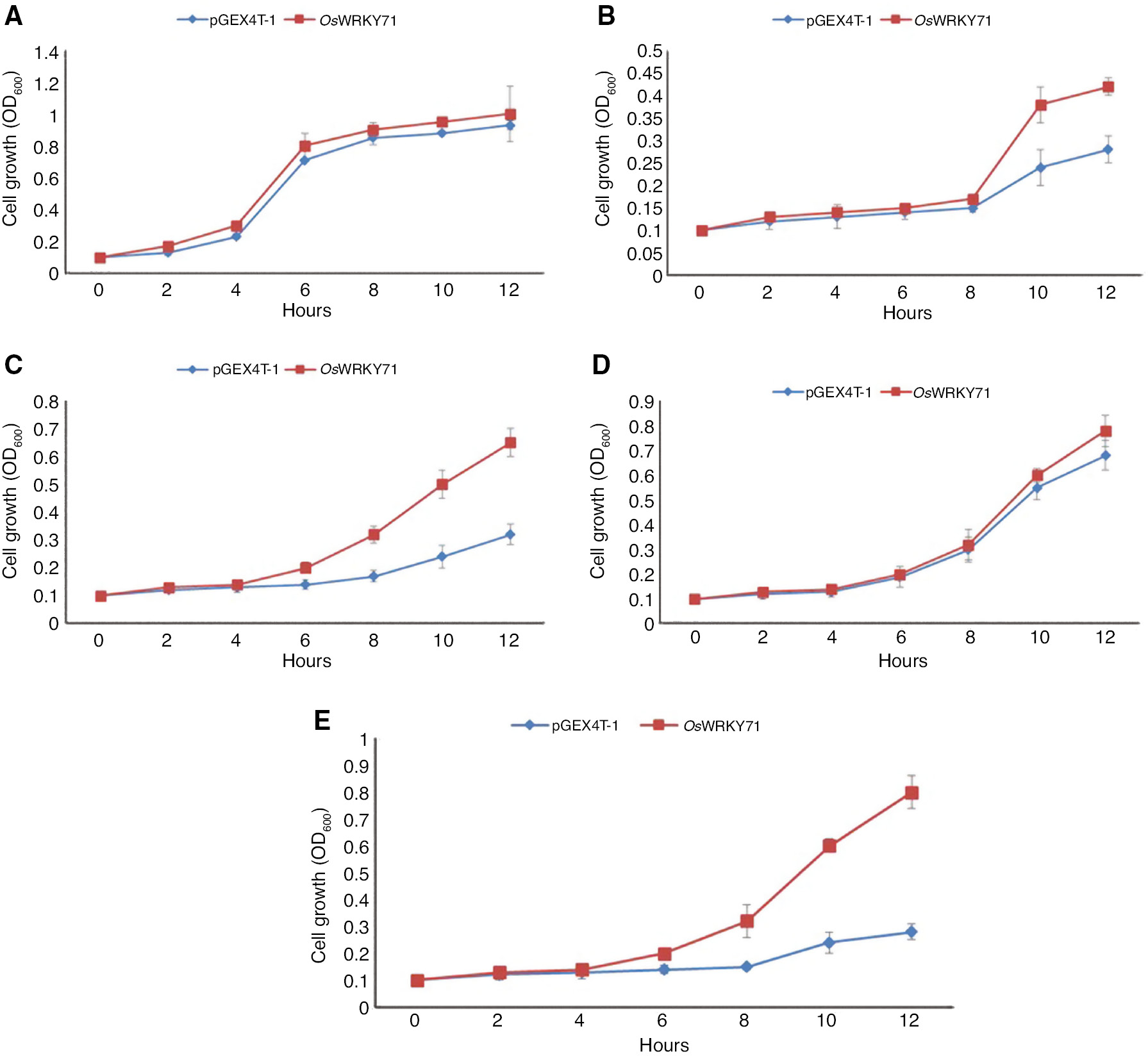

Bacterial growth curves were plotted by observing the growth of bacterial cells in LB medium under salt, drought, cold and heat stresses (Figure 6). Under high salt stress, OsWRKY71 transformants had improved growth in comparison to control. In water stress with mannitol treatment, OsWRKY71-expressing cultures displayed better tolerance than control. In cold stress, recombinants and control cells continued to grow at the same rate whereas in heat shock, recombinants grew markedly till 12 h as compared to untransformed cells that shows growth till 4 h and recorded no additional development (Figure 6).

The growth performance of BL/pGEX4T-OsWRKY71 and BL/pGEX4T-1 recombinants.

Transformed E. coli cells were subjected to different abiotic stresses. (A) LB medium, (B) 500 mM NaCl, (C) 800 mM mannitol, (D) cold treatment, (E) heat treatment. OD600 was measured at a 2 h interval for 12 h and mean values are shown in graph. Error bars represents the standard error.

Bacteria harboring OsWRKY71 showed significant tolerance in salt, drought and heat shocks as indicated by ANOVA. The results of spot, survival rate and growth curve assay under various stresses prove that the heterologous expression of OsWRKY71 confers tolerance to E. coli. Thus, OsWRKY71 might play an important role in gene regulation accompanied by the exposure to stresses, enhancing the adaptation of plant cells to varying environment.

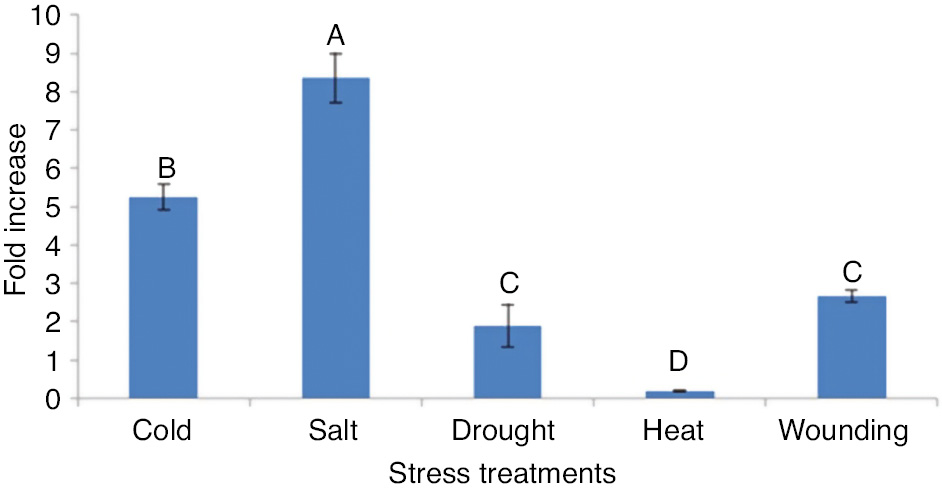

OsWRKY71 gene expression in response to abiotic stresses

OsWRKY71 expression was also examined in rice in response to cold, salt, drought, heat and wounding stresses by RT-qPCR (Figure 7). The Student’s t-test showed significant variation with respect to control in response to all the treatments for OsWRKY71 transcript expression. The expression level of OsWRKY71 gene was up-regulated by cold, salt, drought and wounding stresses. Expression was slightly induced (2-fold) by wounding and drought. Specifically, OsWRKY71 expression was greatly induced (8-fold) by salt stress (500 mM NaCl) while 5-fold increase was observed when cold stress was applied. These findings strongly proposed that OsWRKY71 gene plays important roles in providing tolerance to various abiotic stresses.

Relative expression analysis of OsWRKY71 gene in abiotic stresses by RT-qPCR.

Bars represent standard errors of the mean based on three independent experiments. Different alphabets on graph bars represents the significance of result. Expression level of OsWRKY71 in all types of stresses differ significantly. However, there is non-significant difference in expression level in response of drought and wounding stress.

Discussion

Plant growth and yield are significantly influenced by stresses for instance wounding, drought, salinity, cold and pathogen infection. To minimize damage caused by these harmful factors, plants respond by reprogramming the expression level of stress related genes via various transcription factors. In recent times, the functions of a growing number of stress responsive genes and transcription factors are being revealed. Understanding of these mechanisms is vital for the progress of transgenic approaches to increase the stress tolerance in crop plants. The WRKY transcription factors are implicated in regulating the stress-responsive signaling paths by forming a complex network. Remarkably, a single WRKY transcription factor can regulate multiple stresses via autoregulation, interaction to the W-boxes of their promoters or promoters of other genes and protein-protein interaction as negative and positive controllers [3].

In recent times, the E. coli heterologous expression system has been employed to examine the role of plants genes and transcription factors for their ability in providing tolerance to stress conditions. Using bacterial expression system (E. coli) to express active eukaryotic proteins and enzymes is the method of choice for a protein chemist since it offers many advantages over yeast, insect or mammalian. For instance, S. brachiata salt responsive gene SbSI-1 provided drought and salt resistance to E. coli cells [18]. Escherichia coli cells became resistant to drought stress on transformation with Tamarix hispida gene ThPOD3 [24]. Reddy et al. [25] investigated the expression of a cytoplasmic Hsp70 in E. coli cells and observed the defensive chaperone action against damage brought about by heat and salt stress. Soybean LEA proteins upgraded salinity tolerance in E. coli cells [26]. Yamada et al. [27] also observed the salt tolerance in E. coli, yeast and tobacco cells transformed with the mangrove allene oxide cyclase (AOC) gene. Likewise, plant transcription factors encoding genes, for instance, SbDREB2A, MuNAC4 transcription factor, and JcWRKY were also studied for their ability to provide stress tolerance by using the expression system of E. coli [28], [29]. To assess the defensive role of OsWRKY71 under different abiotic stresses, DNA binding domain containing region of OsWRKY71 was cloned and over-expressed in E. coli (Figure 3). Both qualitative (spot assay, Figures 4 and 5) and quantitative (liquid culture assay, Figure 6) assays were carried out to investigate the growth of bacterial cells containing the pGEX4T-OsWRKY71 and vector pGEX4T-1.

According to our results, OsWRKY71 expressing bacteria were able to tolerate salt, drought and heat stress at 600 mM NaCl, 1 M mannitol and 50°C, respectively. The improvement in growth of E. coli cells can be accredited to its interaction with the promoter of stress-related genes in bacteria. Despite the fact that the WRKY proteins are thought to be available in just plants, these transcription factors have additionally been presented to non-plant species, for instance, unicellular green algae [3]. OsWRKY71 protein belongs to C2H2 type zinc finger proteins. At the beginning zinc finger proteins were supposed to be reserve to the eukaryotes. However, in prokaryotes, the first C2H2 type zinc finger protein was recognized in Agrobacterium tumefaciens in 1998 [30]. Later research has proposed that evolution of eukaryotic zinc finger domains occurred from ROS proteins [31]. The family of WRKY transcription factors depicts the evolution from simple unicellular to complex multicellular frameworks. These examinations demonstrated that there might be some similarity in the regulatory network of eukaryotes and prokaryotes, receiving additional functional specificity based on requirement for existence with the fluctuating climate. These observations recommend that OsWRKY71 cooperates with the transcriptional machinery of the prokaryotic system and control the stress improvement process in E. coli cells.

Real time PCR results have shown increase in expression pattern of OsWRKY71 in KS282 under different abiotic stresses. Similar reports on different WRKY transcription factors on imparting abiotic stress tolerance have been published. The FaWRKY1 showed accumulation in response to elicitors and wounding in strawberry [32].The JcWRKY expression was up-regulated by drought and salinity in Jatropha curcas [29]. Marchive et al. [33] reported the buildup of the VvWRKY1 transcript in transgenic tobacco in reaction to hormones, wounding, and hydrogen peroxide. The WRKY38 showed accumulation against dehydration and cold stress in barley [34]. AtWRKY25 and AtWRKY53 expression were enhanced in reaction to heat and salt stresses in transgenic Arabidopsis plants [35], [36]. TcWRKY53 expression level was also increased by cold and salt treatments in Thlaspi caerulescens [37]. This shows that WRKY genes are involved to be expressed under different abiotic stresses. OsWRKY71 expressing bacterial cells survived under salt, drought and heat stresses whereas the expression of OsWRKY71 was upregulated against salt, drought, wounding and cold stress. The tolerance to salt and drought stress might be due to the presence of common protective mechanisms between prokaryotes and eukaryotes under stress conditions [38]. Different responses of E. coli and rice to cold and heat stress are observed which might be due to the difference in mode of gene expression in some cases in prokaryotes and eukaryotes because of difference in molecular biology of their transcription and translation [39].

To sum up, this study illustrates the role of OsWRKY71 in abiotic stresses. OsWRKY71 is responsive to salt, drought and heat stresses. OsWRKY71 may play significant role in plant abiotic stress resistance and could be employed in crops genetic engineering with the purpose of enhancing stress tolerance.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grant of Higher Education Commission (HEC) of Pakistan through an Indigenous Fellowship (Funder Id: http://dx.doi.org/10.13039/501100004681, Pin: 117-3978-BM7-083 (50018550)) and International Research Support Initiative Program Fellowships to Ms. Farah Deeba (Pin: IRSIP25BMS08).

-

Conflict of interest: The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

References

1. Golldack D, Luking I, Yang O. Plant tolerance to drought and salinity: stress regulating transcription factors and their functional significance in the cellular transcriptional network. Plant Cell Rep 2011;30:1383–91.10.1007/s00299-011-1068-0Search in Google Scholar

2. Cheng Y, Zhou Y, Yang Y, Chi YJ, Zhou J, Chen JY, et al. Structural and functional analysis of VQ motif-containing proteins in Arabidopsis as interacting proteins of WRKY transcription factors. Plant Physiol 2012;159:810–25.10.1104/pp.112.196816Search in Google Scholar

3. Rushton PJ, Somssich IE, Ringler P, Shen QJ. WRKY transcription factors. Trends Plant Sci 2010;15:247–58.10.1016/j.tplants.2010.02.006Search in Google Scholar

4. Eulgem T, Rushton PJ, Robatzek S, Somssich IE. The WRKY superfamily of plant transcription factors. Trends Plant Sci 2000;5:199–206.10.1016/S1360-1385(00)01600-9Search in Google Scholar

5. Ulker B, Somssich IE. WRKY transcription factors: from DNA binding towards biological function. Curr Opin Plant Biol 2004;7:491–8.10.1016/j.pbi.2004.07.012Search in Google Scholar PubMed

6. Wu K-L, Guo Z-J, Wang H-H, Li J. The WRKY family of transcription factors in rice and arabidopsis and their origins. DNA Res 2005;12:9–26.10.1093/dnares/12.1.9Search in Google Scholar PubMed

7. Xu X, Chen C, Fan B, Chen Z. Physical and functional interactions between pathogen-induced Arabidopsis WRKY18, WRKY40, and WRKY60 transcription factors. Plant Cell 2006;18:1310–26.10.1105/tpc.105.037523Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

8. Shen QH, Saijo Y, Mauch S, Biskup C, Bieri S, Keller B, et al. Nuclear activity of MLA immune receptors links isolate-specific and basal disease-resistance responses. Science 2007;315:1098–103.10.1126/science.1136372Search in Google Scholar PubMed

9. Jiang C-J, Yoshida R, Shimono M, Inoue H, Sugano S, Hayashi N, et al. Abscisic acid interacts antagonistically with salicylic acid signaling pathway in rice–magnaporthe grisea interaction. Mol Plant-Microbe Interact 2010;23:791–8.10.1094/MPMI-23-6-0791Search in Google Scholar PubMed

10. Chujo T, Otake Y, Nojiri H, Miyamoto K, Yokotani N, Shimogawa T, et al. OsWRKY28, a PAMP-responsive transrepressor, negatively regulates innate immune responses in rice against rice blast fungus. Plant Mol Biol 2013;82:23–37.10.1007/s11103-013-0032-5Search in Google Scholar PubMed

11. Delteil A, Blein M, Faivre-Rampant O, Guellim A, Estevan J, Hirsch J, et al. Building a mutant resource for the study of disease resistance in rice reveals the pivotal role of several genes involved in defence. Mol Plant Pathol 2012;13:72–82.10.1111/j.1364-3703.2011.00731.xSearch in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

12. Birkenbihl RP, Diezel C, Somssich IE. Arabidopsis WRKY33 is a key transcriptional regulator of hormonal and metabolic responses toward Botrytis cinerea infection. Plant Physiol 2012;159:266–85.10.1104/pp.111.192641Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

13. Dang FF, Wang YN, Yu L, Eulgem T, Lai Y, Liu ZQ, et al. CaWRKY40, a WRKY protein of pepper, plays an important role in the regulation of tolerance to heat stress and resistance to Ralstonia solanacearum infection. Plant Cell Environ 2013;36:757–74.10.1111/pce.12011Search in Google Scholar PubMed

14. Liu X, Bai X, Wang X, Chu C. OsWRKY71, a rice transcription factor, is involved in rice defense response. J Plant Physiol 2007;164:969–79.10.1016/j.jplph.2006.07.006Search in Google Scholar PubMed

15. Zhang ZL, Xie Z, Zou X, Casaretto J, Ho TH, Shen QJ. A rice WRKY gene encodes a transcriptional repressor of the gibberellin signaling pathway in aleurone cells. Plant Physiol 2004;134:1500–13.10.1104/pp.103.034967Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

16. Thompson JD, Higgins DG, Gibson TJ. CLUSTAL W: improving the sensitivity of progressive multiple sequence alignment through sequence weighting, position-specific gap penalties and weight matrix choice. Nucleic Acids Res 1994;22:4673–80.10.1093/nar/22.22.4673Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

17. Bashir K, Khan NM, Rasheed S, Salim M. Indica rice varietal development in Pakistan: an overview. Paddy Water Environ 2007;5:73–81.10.1007/s10333-007-0073-ySearch in Google Scholar

18. Yadav NS, Singh VK, Singh D, Jha B. A novel gene SbSI-2 encoding nuclear protein from a halophyte confers abiotic stress tolerance in E. coli and tobacco. PLoS One 2014;9:e101926.10.1371/journal.pone.0101926Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

19. Zheng H, Chen L, Han X, Zhao X, Ma Y. Classification and regression tree (CART) for analysis of soybean yield variability among fields in Northeast China: The importance of phosphorus application rates under drought conditions. Agric Ecosyst Environ 2009;132:98–105.10.1016/j.agee.2009.03.004Search in Google Scholar

20. Hu H, You J, Fang Y, Zhu X, Qi Z, Xiong L. Characterization of transcription factor gene SNAC2 conferring cold and salt tolerance in rice. Plant Mol Biol 2008;67:169–81.10.1007/s11103-008-9309-5Search in Google Scholar PubMed

21. Fang Y, Liao K, Du H, Xu Y, Song H, Li X, et al. A stress-responsive NAC transcription factor SNAC3 confers heat and drought tolerance through modulation of reactive oxygen species in rice. J Exp Bot 2015;66:6803–17.10.1093/jxb/erv386Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

22. Schmittgen TD, Livak KJ. Analyzing real-time PCR data by the comparative CT method. Nat Protoc 2008;3:1101–8.10.1038/nprot.2008.73Search in Google Scholar PubMed

23. Mendes Pinto I, Rubinstein B, Kucharavy A, Unruh JR, Li R. Actin depolymerization drives actomyosin ring contraction during budding yeast cytokinesis. Dev Cell 2012;22:1247–60.10.1016/j.devcel.2012.04.015Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

24. Guo XH, Jiang J, Wang BC, Li HY, Wang YC, Yang CP, et al. ThPOD3, a truncated polypeptide from Tamarix hispida, conferred drought tolerance in Escherichia coli. Mol Biol Rep 2010;37:1183–90.10.1007/s11033-009-9484-8Search in Google Scholar PubMed

25. Reddy PS, Mallikarjuna G, Kaul T, Chakradhar T, Mishra RN, Sopory SK, et al. Molecular cloning and characterization of gene encoding for cytoplasmic Hsc70 from Pennisetum glaucum may play a protective role against abiotic stresses. Mol Genet Genomics 2010;283:243–54.10.1007/s00438-010-0518-7Search in Google Scholar PubMed

26. Lan Y, Cai D, Zheng Y-Z. Expression in Escherichia coli of three different soybean late embryogenesis abundant (LEA) genes to investigate enhanced stress tolerance. J Integr Plant Biol 2005;47:613–21.10.1111/j.1744-7909.2005.00025.xSearch in Google Scholar

27. Yamada A, Saitoh T, Mimura T, Ozeki Y. Expression of mangrove allene oxide cyclase enhances salt tolerance in escherichia coli, yeast, and tobacco cells. Plant Cell Physiol 2002;43:903–10.10.1093/pcp/pcf108Search in Google Scholar PubMed

28. Gupta K, Agarwal PK, Reddy MK, Jha B. SbDREB2A, an A-2 type DREB transcription factor from extreme halophyte Salicornia brachiata confers abiotic stress tolerance in Escherichia coli. Plant Cell Rep 2010;29:1131–7.10.1007/s00299-010-0896-7Search in Google Scholar PubMed

29. Agarwal P, Dabi M, Agarwal PK. Molecular cloning and characterization of a group II WRKY transcription factor from Jatropha curcas, an important biofuel crop. DNA Cell Biol 2014;33:503–13.10.1089/dna.2014.2349Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

30. Chou AY, Archdeacon J, Kado CI. Agrobacterium transcriptional regulator Ros is a prokaryotic zinc finger protein that regulates the plant oncogene ipt. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1998;95:5293–8.10.1073/pnas.95.9.5293Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

31. Moreira D, Rodrı́guez-Valera F. A mitochondrial origin for eukaryotic C2H2 zinc finger regulators? Trends Microbiol 2000;8:448–9.10.1016/S0966-842X(00)01850-3Search in Google Scholar

32. Encinas-Villarejo S, Maldonado AM, Amil-Ruiz F, de los Santos B, Romero F, Pliego-Alfaro F, et al. Evidence for a positive regulatory role of strawberry (Fragaria x ananassa) Fa WRKY1 and Arabidopsis At WRKY75 proteins in resistance. J Exp Bot 2009;60:3043–65.10.1093/jxb/erp152Search in Google Scholar

33. Marchive C, Mzid R, Deluc L, Barrieu F, Pirrello J, Gauthier A, et al. Isolation and characterization of a Vitis vinifera transcription factor, VvWRKY1, and its effect on responses to fungal pathogens in transgenic tobacco plants. J Exp Bot 2007;58:1999–2010.10.1093/jxb/erm062Search in Google Scholar

34. Marè C, Mazzucotelli E, Crosatti C, Francia E, Cattivelli L. Hv-WRKY38: a new transcription factor involved in cold- and drought-response in barley. Plant Mol Biol 2004;55:399–416.10.1007/s11103-004-0906-7Search in Google Scholar

35. Li S, Fu Q, Huang W, Yu D. Functional analysis of an Arabidopsis transcription factor WRKY25 in heat stress. Plant Cell Rep 2009;28:683–93.10.1007/s00299-008-0666-ySearch in Google Scholar

36. Jiang Y, Guo L, Ma X, Zhao X, Jiao B, Li C, et al. The WRKY transcription factors PtrWRKY18 and PtrWRKY35 promote Melampsora resistance in Populus. Tree Physiol 2017;37:665–75.10.1093/treephys/tpx008Search in Google Scholar

37. Wei W, Zhang Y, Han L, Guan Z, Chai T. A novel WRKY transcriptional factor from Thlaspi caerulescens negatively regulates the osmotic stress tolerance of transgenic tobacco. Plant Cell Rep 2008;27:795–803.10.1007/s00299-007-0499-0Search in Google Scholar

38. Liu Y, Zheng Y. PM2, a group 3 LEA protein from soybean, and its 22-mer repeating region confer salt tolerance in Escherichia coli. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2005;331:325–32.10.1016/j.bbrc.2005.03.165Search in Google Scholar

39. Lawrence JG. Shared strategies in gene organization among prokaryotes and eukaryotes. Cell 2002;110:407–13.10.1016/S0092-8674(02)00900-5Search in Google Scholar

©2020 Walter de Gruyter GmbH, Berlin/Boston

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Review Article

- Lipidomics and cognitive dysfunction – A Narrative review

- Research Articles

- Effects of topiramate on adipocyte differentiation and gene expression of certain carbonic anhydrase isoenzymes

- Heterologous expression of a plant WRKY protein confers multiple stress tolerance in E. coli Bir bitkinin heterolog ifadesi WRKY proteini çoklu stres yaratır E. coli’de tolerans

- Cytogenetic impact of sodium chloride stress on root cells of Vigna radiata L. seedlings

- Understanding the impacts of self-shuffling approach on structure and function of shuffled endoglucanase enzyme via MD simulations

- Evaluation ofTrichoderma atroviride and Trichoderma citrinoviride growth profiles and their potentials as biocontrol agent and biofertilizer

- Physio-biochemical analyses in seedlings of sorghum-sudangrass hybrids that are grown under salt stress under in vitro conditions

- The structural diversity of ginsenosides affects their cholinesterase inhibitory potential

- Extracellular acidity and oxygen availability conjointly control eukaryotic cell growth via modulation of cytoplasmic translation

- Genome-wide identification, phylogeny and expression analysis of G6PC gene family in common carp, Cyprinus carpio

- The effect of Diplotaenia turcica root extract in streptozotocin-induced diabetic rats

- Letter to the Editor

- Metabolomics analysis of medicinal insect Protaetia brevitarsis after Bacillus subtilis fermentation

- Opinion Paper

- Identifying and solving scientific problems in the medicine: key to become a competent scientist

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Review Article

- Lipidomics and cognitive dysfunction – A Narrative review

- Research Articles

- Effects of topiramate on adipocyte differentiation and gene expression of certain carbonic anhydrase isoenzymes

- Heterologous expression of a plant WRKY protein confers multiple stress tolerance in E. coli Bir bitkinin heterolog ifadesi WRKY proteini çoklu stres yaratır E. coli’de tolerans

- Cytogenetic impact of sodium chloride stress on root cells of Vigna radiata L. seedlings

- Understanding the impacts of self-shuffling approach on structure and function of shuffled endoglucanase enzyme via MD simulations

- Evaluation ofTrichoderma atroviride and Trichoderma citrinoviride growth profiles and their potentials as biocontrol agent and biofertilizer

- Physio-biochemical analyses in seedlings of sorghum-sudangrass hybrids that are grown under salt stress under in vitro conditions

- The structural diversity of ginsenosides affects their cholinesterase inhibitory potential

- Extracellular acidity and oxygen availability conjointly control eukaryotic cell growth via modulation of cytoplasmic translation

- Genome-wide identification, phylogeny and expression analysis of G6PC gene family in common carp, Cyprinus carpio

- The effect of Diplotaenia turcica root extract in streptozotocin-induced diabetic rats

- Letter to the Editor

- Metabolomics analysis of medicinal insect Protaetia brevitarsis after Bacillus subtilis fermentation

- Opinion Paper

- Identifying and solving scientific problems in the medicine: key to become a competent scientist