Topically applied novel TRPV1 receptor antagonist, ACD440 Gel, reduces temperature-evoked pain in patients with peripheral neuropathic pain with sensory hypersensitivity, a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, crossover study

Abstract

Background

The transient receptor potential cation channel subfamily V1 (TRPV1) receptor is an important factor in pain transmission. The present Phase 2a study investigated the effect on evoked pain and safety of a topically administered TRPV1-antagonist (ACD440 Gel) in patients with chronic peripheral neuropathic pain (PNP).

Methods

This was an exploratory, randomized, placebo-controlled double-blind crossover study in patients with probable or definite PNP demonstrating sensory hypersensitivity, assessed as evoked pain on suprathreshold sensory stimulation, i.e. hyperalgesia. The aetiologies included a mix of postherpetic neuralgia, postoperative neuropathic pains, and chemotherapy-induced pain. Patients administered ACD440 Gel twice daily onto the painful area(s) for 7 days. Primary endpoint was hyperalgesia to brush, cold, heat, and pinprick. Secondary endpoints included spontaneous pain and Neuropathic Pain Symptom Inventory Questionnaire (NPSI). Due to a significant period effect, a post hoc analysis was conducted, including only period 1 data, i.e. a parallel group comparison.

Results

Fourteen patients were enrolled and completed the study. ACD440 Gel reduced pain intensity evoked by a 40°C thermoroller stimulus in heat hyperalgesic patients, by ACD440 from median 6 (IQR 4.75, 7.75) to 1.5 (IQR 0.75, 2.25), i.e. by −5.0 (95%CI −11.2, 1.2) vs placebo from median 4 (IQR 3.5, 5.0) to median 5.0 (IQR 4.5, 6.5), i.e. by 1.3 (95%CI −1.5, 4.2), p = 0.029. There were no adverse events induced by study treatment. Evoked mechanical hyperalgesia and brush allodynia were not significantly affected, p = 0.07.

Conclusion

ACD440 Gel demonstrated a significant analgesic effect on thermally evoked pain, especially in suprathreshold heat pain. This is congruent with an attenuation of thermal hyperalgesia in chronic neuropathic pain patients with C-fibre mediated pain, while there was no effect on evoked pain related to Aβ and Aδ stimuli. The results support further clinical development in patients with thermally induced C-fibre mediated pain.

1 Introduction

Neuropathic pain is caused by lesions or diseases of the somatosensory nervous system, where pain intensity of clinical relevance affects approximately 10% of the general population [1,2], out of which 85% is peripheral neuropathic pain (PNP) [3]. Neuropathic pain is often severely debilitating and has both a severe impact on quality of life and high direct socioeconomic costs for patients [4,5].

PNP can be classified by its aetiology as well as by sensory phenotype. The sensory phenotypes can be classified into three main categories, namely, sensory loss, mainly mechanical hypersensitivity and thermal hypersensitivity, each contributing to approximately one third of cases with PNP [6,7,8]. All sensory phenotypes are represented in all aetiologies of PNP, though in somewhat different proportions. The phenotype characterization is most often verified by quantitative sensory testing, measuring perception and pain thresholds of a battery of 13 different somatosensory parameters. However, patients often have not only allodynia to these sensory stimuli, but also increased pain on suprathreshold stimulation, hyperalgesia. The intensity of pain induced by suprathreshold stimulation has been used as an outcome variable in clinical trials and also in the clinic, as an assessment of treatment efficacy, together with reports of spontaneous pain.

The clinical significance of sensory profiles is unclear [6]. Currently, we have no knowledge of the individualized based treatment of neuropathic pain or of the mechanisms underlying a specific pain phenotype. There is some evidence from previous studies that patient profiling can be used in practice to determine optimal treatment strategies for subgroups of neuropathic pain patients [8].

Existing treatments for PNP are mostly oral and include tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs), serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRI), gabapentinoids, and tramadol. Only two topical treatments are approved: lidocaine patches and 8% capsaicin patches. In addition, in severe cases, opioids are prescribed. Overall, the limited efficacy leaves a majority of patients without sufficient pain relief. Accordingly, there is a need for analgesics utilizing other pain targets, specific to certain phenotypes, being developed to improve treatment efficacy of chronic PNP.

One novel target of potential value as a treatment option for neuropathic pain is the transient receptor potential cation channel subfamily V1 (TRPV1), a peripherally expressed receptor known to play an important role in pain signalling [9,10]. TRPV1 receptors are located on the peripheral nerve endings of the unmyelinated C-fibres, and are often upregulated or overexpressed in remaining C-fibre endings in patients with PNP, causing so called irritable nociceptors, or sensory hypersensitivity to peripheral stimulation [8,11]. The TRPV1 receptor is activated by stimuli such as heat, acidity, and capsaicin, and as such, one of the triggers of pain transduction in the peripheral tissue. Antagonism of the TRPV1 receptors has demonstrated a significant pain reduction in human experimental pain and in postoperative pain [12,13]. Previous efforts to develop TRPV1 antagonists for the treatment of chronic pain have failed due to systemic target related side effect [14,15,16] and a potent, locally administered TRPV1 antagonist could provide a novel non-opioid mechanism to obtain an analgesic effect without the associated side-effects and tolerability issues observed with previously failed oral therapies. AlzeCure Pharma is developing ACD440 Gel as a topical treatment for PNP in patients with sensory hypersensitivity, the topical administration avoiding effects related to high systemic exposure and thus without compromising side effects.

The ACD440 Gel formulation has previously been tested in healthy adult subjects, demonstrating >50% reduction in laser-evoked skin pain compared to placebo, with very low plasma concentrations, and a favourable safety profile [17]. This confirms that ACD440 reaches the epidermal nerve endings.

The current study aimed to confirm that ACD440 Gel could exert similar efficacy on the TRPV1 receptors in skin of patients suffering chronic PNP. The present study thus explored if a twice daily dermal application of ACD440 Gel for 7 days could reduce the intensity of pain evoked by suprathreshold stimuli of heat, cold, pinprick, and brush stroke to the affected painful areas, compared to placebo.

2 Methods

This was a phase 2a, crossover, randomized, single-centre, double-blind, placebo-controlled study exploring whether topically administered ACD440 gel, 14 mg/g, can reduce evoked pain compared to placebo in subjects with PNP with sensory hypersensitivity. The study was conducted at a single site, Multidisciplinary Pain Centre at Uppsala University Hospital, Uppsala, Sweden, in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki as adopted by the World Medical Association in 1964, and lastly amended in 2013. The study was conducted in accordance with Good Clinical Practice, after regulatory approval by the Swedish MPA (EudraCT 2022-000902-82) and ethics approval by the Swedish SERA (no. 2022-01922-01). The study was preregistered on www.clinicaltrials.gov (NCT05416931).

2.1 Study design and objectives

The key objective of the study was to investigate whether ACD440 gel, 14 mg/g, can reduce evoked pain compared to placebo in subjects with PNP with sensory hypersensitivity.

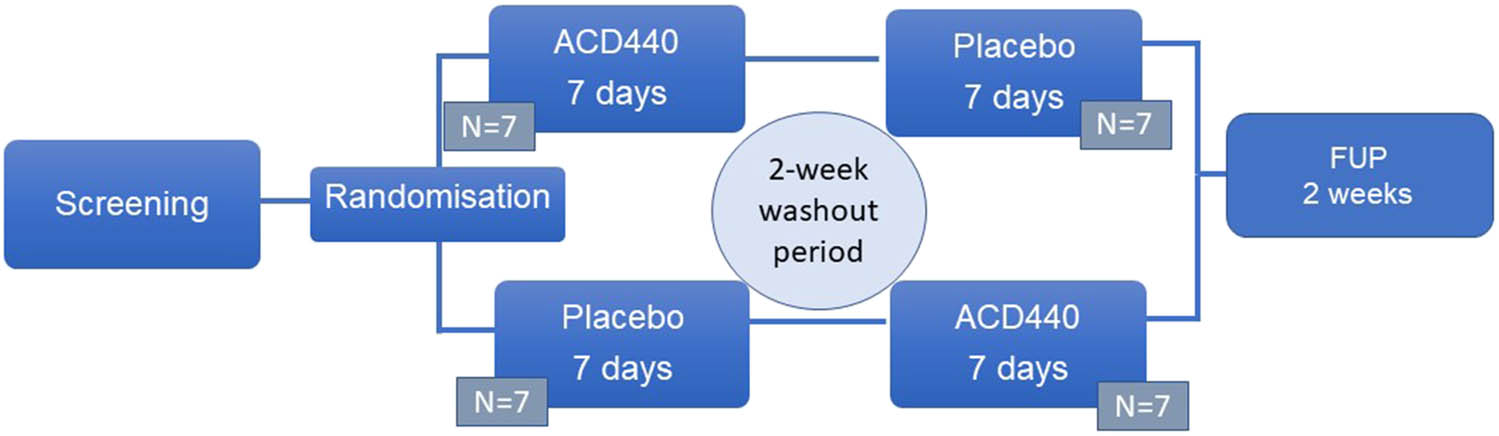

This randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, crossover study encompassed six visits: a screening visit, two treatment periods of 7 days, with a 14-day washout period to avoid any carryover effects, and a follow-up visit. Each treatment period included one baseline visit and an end-of-treatment visit (Figure 1).

Study design. This was a crossover study, with 7 days of study treatment, periods separated by a 2-week washout period without any study related activities. FUP: Follow-up visit.

2.2 Study medication and randomization

Patients were randomized by a computer algorithm to treatment sequence by an independent statistician. Treatment sequence was randomized in blocks of six (three patients receiving the sequence ACD440 Gel – Placebo gel, and three receiving the sequence Placebo gel – ACD440 Gel). The randomization list was kept guarded by the statistician, and for each patient, the sequence order was put in a sealed envelope, kept in a locked compartment at the study site. Study drug was delivered to the study site in kits of three dispensers, one for each treatment period, delivered to the patients labelled with study number, randomization number, and treatment sequence number (period 1 or 2), at the beginning of each treatment period. The active ACD440 Gel and placebo study medications were identical in appearance and smell. ACD440 Gel and placebo gel were applied twice daily, based on the results from a previous study in healthy subjects, where the effect of a single 1 h application lasted for 9–12 h [14].

2.3 Study participants

Participants were recruited via several routes, all preapproved by the Swedish SERA: Patients already being listed at the clinic, patients recruited via advertisements in local newspapers, on local public transportation, geotargeted on social media, and by referrals from other clinics. For patients having gained knowledge of the study by public advertisements, a call centre was set up, conducting a telephone interview, and for patients being potentially eligible, these were guided to the study site for further examinations. A video with information on the exact study procedures, as a preparatory information before the physical screening and eligibility visit, with one of the study nurses informing about the study, was also available for interested potential study participants.

For inclusion in the study, subjects had to fulfil all the following criteria: Signed informed consent, male or female, age 18–85 years, previously diagnosed with probable or definite PNP with peripheral sensitivity phenotype, of any aetiology, and with a history of pain lasting from 6 months to 10 years. The patients must present with sensory hypersensitivity to one or more of the following sensory stimuli: mechanical (brush or pinprick), thermal (cold or heat), with evoked pain intensity of 4–7 out of 10 in numerical rating scale (NRS) to at least one of the sensory stimuli. The affected body surface area of sensory hypersensitivity could be up to a total of 600 cm2. Participants with reproductive potential were required to use effective means of contraception.

Exclusion criteria included body mass index (BMI) <18.5 kg/m2 or >35 kg/m2, being a pregnant or breastfeeding woman, liver enzymes (AST and ALT) levels >2 times the upper limit of normal; any clinically significant neurological disease, other systemic diseases or conditions potentially interfering with study assessments, including another concomitant pain condition with an intensity of ≥4 out of 10 for which pain ratings could interfere with study assessments, a Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale score of 15 or above; ongoing HIV or Hepatitis B and/or C, other ongoing infection with fever; known history of hypersensitivity to study treatment components or a history of anaphylactic reactions; dermatological conditions in the intended treatment areas, including scars and tattoos; malignancy within the past 3 years (in situ basal cell carcinoma and squamous cell carcinoma of the skin exempt); any significant psychiatric disorder, including drug abuse or dependency; daily intake of opioids at a daily dose of more than 60 morphine equivalents, use of lidocaine patches within 7 days or use of capsaicin patches within 4 months prior to randomization until the follow-up visit; previous participation in a clinical study within 30 days or 5 study drug half-lives. Participants were allowed to maintain stable doses of concomitant centrally acting treatment for their neuropathic pain, including SNRIs, TCAs, gabapentinoids, and low doses of opioids, if at stable doses from 2 weeks prior to screening and throughout the study period.

2.4 Study specific methodologies

For final evaluation of eligibility as well as for treatment efficacy, a bedside semi-quantitative sensory test of evoked pain was conducted for four pain modalities (dynamic touch, pinprick, cold, and heat) using four different stimuli: brushing with a soft brush (SENSELab Brush-05, Somedic SenseLab AB, Sösdala, Sweden), pinprick (8 or 16 mN depending on body location) (PinPrick Stimulators, MRC Systems GmbH, Heidelberg, Germany), a cold metal Thermoroller (6°C), and a hot metal Thermoroller (40°C) (Somedic SenseLab AB, Sösdala, Sweden) (Figure 2). Patients rated the perceived pain intensity elicited by these suprathreshold stimuli. This testing method has been previously shown to exhibit low intraindividual variability, high-retest reliability, and low investigator-related test variability [18,19] and the individual intensity level of the respective stimulus were set based on age, gender, and body location [20,21].

Bedside sensory assessments were conducted for detection and quantification of hyperalgesia to brush, 6°C cold (thermoroller indicated by blue tape), 40°C heat (thermoroller indicated by red tape), and pinprick. Source: Created by authors.

2.5 Study objectives and endpoints

The study efficacy endpoints included three types of pain assessments all collected at study visits: (i) evoked pain at bedside tests (NRS 0–10) with provocation by brushing, pinprick, cold, or heat (ii) spontaneous pain intensity by recall over the last 24 h and (iii) the Neuropathic Pain Symptom Inventory (NPSI) questionnaire in which patients recalled their pain patterns over recent days [22,23].

The primary study endpoint was change from baseline (Day 1 in each treatment period) until Day 7 (14 applications), in evoked brushing pain score, evoked pinprick pain score, or evoked cold temperature induced pain score: one of the qualities for which the patient scored the highest at baseline.

The primary objective of the study was to compare the primary endpoint between the active ACD440 Gel and placebo gel treatment periods. Due to the risk of a period effect in a cross-over study, results were also planned to be summarized by treatment period.

Secondary endpoints were: Change from baseline (Day 1 in each treatment period) to Day 7 (14 applications) in pain intensity by 24 h recall, change from baseline to Day 7 in the average of all four bedside evoked pain scores (brushing, pinprick, cold, and heat provocation), change from baseline to Day 7 in NPSI scores, and the patient´s global impression of change (PGIC) at the end of each treatment period. The PGIC consisted of a numerical scale from 1 to 7, where 1 depicts very much improved, 4 depicts no difference and 7 depicts very much worsened.

All secondary objectives aimed to compare the endpoints between the active ACD440 Gel and placebo gel treatment periods. Results were also planned to be summarized by treatment period.

Safety endpoints included number and severity of reported adverse events (AEs), vital signs, and results from laboratory safety analyses.

Exploratory endpoints included comparing the change in evoked pain endpoints between the active ACD440 Gel and placebo gel treatment periods, and comparing changes in evoked pain in treatment period 1 only between the two treatments (avoiding any period effect). The latter comparisons were also done within hyperalgesia patient subgroups.

The following hyperalgesia patient subgroups were assessed and included the patients who demonstrated hyperalgesia in terms of a positive sensory phenotype at baseline: Patients with brush allodynia, patients with pinprick hyperalgesia, patients with heat hyperalgesia, patients with cold hyperalgesia, patients with thermal hyperalgesia (including patients with either heat or cold hyperalgesia) and patients with non-thermal hyperalgesia (patients with neither heat nor cold hyperalgesia).

2.6 Study procedures

After obtaining informed consent, and collection of demographic data, medical history, and physical and neurological examination, safety laboratory samples were taken and the area of body surface area to be treated was estimated. The total treatment area could cover an application of 50 to 600 cm2, and constitute of one or two areas, the latter in cases of bilateral pain. Patients were trained in application of the ACD440 Gel/placebo gel, to be repeated in the morning and in the evening, for 7 days (a total of 14 applications). The patient then went home and administered the first dose in the evening of Day 1. In the morning of Day 7 patients came back to the clinic for assessments, having administered the last study treatment dose. Assessments of evoked pain, NPSI and PGIC were performed and safety assessments (physical examination, vital signs, safety laboratory testing) and AEs were collected. After a two-week washout period, the same procedure was repeated for treatment period 2. After the completion of the second study period, patients underwent a follow-up visit after 14 days.

2.7 Statistical considerations

The sample size calculation was based on the results in a recently conducted proof-of-mechanism study in healthy participants, comparing ACD440 Gel and placebo gel, in a single-session crossover design. Based on these results, where ACD440 Gel reduced the laser evoked pain by 50% [14], it was estimated that a 30% reduction of the heat (37 C) evoked pain and 2.5% one-sided significance level in a Wilcoxon signed rank test of the within patient crossover difference between treatments in the primary endpoint would require a sample size of 14 randomized patients out of which 12 study completers, to achieve 80% power (10% dropout rate).

The full analysis set comprises all randomized patients. The safety analysis set comprises all participants having taken at least one dose of study medication. All preplanned efficacy analyses were performed on the full analysis set, and all safety analyses were performed on the safety analysis set. In subgroup analyses, the dataset is defined per analysis.

The hypotheses that within-subject treatment difference = 0 was tested using one-sided Wilcoxon signed rank tests, and would be rejected if p < 0.025. No formal hypothesis testing was carried out for secondary or exploratory endpoints. Data are summarized descriptively as appropriate. Exploratory analyses of change from baseline in evoked pain and average evoked pain based on treatment period 1 only (ACD440 Gel vs placebo) were performed using Wilcoxon Mann Whitney tests (parallel group comparison), for which one-sided p-values < 0.025 were regarded as (descriptively) statistically significant.

All statistical analyses were performed in accordance with the ICH E9 guideline for Statistical Principles for Clinical Trials, using SAS® (Version 9.4 or higher, SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA).

3 Results

A total of 23 subjects were screened for inclusion and 14 were randomized. There were 8 screening failures. One participant withdrew from the study prior to randomization, for personal reasons. Seven subjects were randomized (1:1) into each treatment sequence. There were no withdrawals during the study and no subject discontinued treatment. All 14 subjects (9 females, 5 males) participated in all treatment sessions, taking place between June 2022 and March 2023). All were of Caucasian ethnicity with a median age of 70 (range 50–85) years, and average BMI of 24.9 (SD 4.4). Nine of the patients had stable doses of ongoing medication for their neuropathic pain, 6 were taking paracetamol, 3 gabapentinoids, 2 opioids and 1 amitriptyline. A summary of demography and baseline characteristics is presented in Table 1. All randomized and treated subjects received treatment over either one or two body areas. The average treatment area was 261 cm2 (SD 147; range 80–600 cm2). All subjects were included in the primary efficacy and safety analyses. At inclusion, 11 subjects presented with cold hyperalgesia (6°C metal thermoroller), 9 subjects with heat hyperalgesia (40°C metal thermoroller), 9 subjects with mechanical hyperalgesia, and 9 subjects with brush allodynia. Baseline assessments were collected before the start of each treatment period.

Demographics and clinical characteristics of the included patients

| Demographics | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | 5 M, 9 F | |||

| Age, years, mean value (SD) | 68.5 (9.7) | |||

| Weight, kg, mean value (SD) | 71.76 (16.04) | |||

| Height, cm, mean value (SD) | 169.4 (13.0) | |||

| BMI, kg/m2 mean value (SD) | 24.92 (4.42) | |||

| History of neuropathic pain, years, median (range) | 4.75 (0.7–8.5) | |||

| Diagnosis | Gender (M/F) | Age (years) | History | Treatment order |

| Postherpetic neuralgia | F | 74 | 7 years | ACD440-placebo |

| Postherpetic neuralgia | F | 72 | 1.5 years | Placebo-ACD440 |

| Postherpetic neuralgia | F | 72 | 0.7 years | ACD440-placebo |

| Postherpetic neuralgia | F | 77 | 5 years | Placebo-ACD440 |

| Postherpetic neuralgia | M | 68 | 7 years | Placebo-ACD440 |

| Median nerve mononeuropathy | F | 55 | 6 years | ACD440-placebo |

| Neuroma left leg | F | 50 | 4.5 years | Placebo-ACD440 |

| Tibial nerve mononeuropathy | F | 71 | 1.1 years | Placebo-ACD440 |

| Postherpetic neuralgia | F | 65 | 1.3 years | ACD440-placebo |

| Post amputation pain | M | 69 | 6 years | ACD440-placebo |

| Postherpetic neuralgia | M | 79 | 6.3 years | Placebo-ACD440 |

| Post finger amputation pain | M | 56 | 2 years | Placebo-ACD440 |

| Postherpetic neuralgia | M | 85 | 8.5 years | ACD440-placebo |

| Chemotherapy induced neuropathic pain | F | 66 | 2.5 years | ACD440-placebo |

| Concomitant analgesics during trial | ||||

| Any analgesic | 9 (64.3%) | |||

| Paracetamol | 6 (42.9%) | |||

| Gabapentinoids | 3 (21.4%) | |||

| Opioids | 2 (14.2%) | |||

| Amitriptyline | 1 (7.1%) |

3.1 Efficacy/pharmacodynamics

Baseline pain intensity (most painful evoked pain) for period 1 was 6.43 (95% CI 4.74, 8.12) and for period 2 it was 6.21 (95% CI 4.63, 7.80) (Table 2).

Baseline scores for the respective treatment periods

| Assessment | Period 1, Day 1 | Period 2, Day 1 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean value (SD) | Mean value (SD) | |||||

| All patients (N = 14) | Patients with each hyperalgesia | All patients (N = 14) | Patients with each hyperalgesia | |||

| Score | N | NRS | Score | N | NRS | |

| Heat-evoked pain (37°C) | 2.8 (3.3) | 7 | 5.6 (2.4) | 4.1 (3.9) | 10 | 5.8 (3.3) |

| Cold-evoked pain (6°C) | 5.4 (3.3) | 12 | 6.3 (2.6) | 4.6 (3.7) | 12 | 5.3 (3.4) |

| Brush allodynia | 4.4 (3.6) | 10 | 6.2 (2.6) | 4.0 (3.2) | 11 | 5.1 (2.7) |

| Pinprick-evoked pain | 6.0 (3.5) | 13 | 6.5 (3.2) | 5.2 (3.0) | 13 | 5.6 (2.8) |

| Spontaneous pain intensity by 24 h recall | 5.6 (1.4) | 5.7 (3.0) | ||||

| NPSI evoked pain subscore, average 24-h recall | 5.2 (2.7) | 4.6 (1.9) | ||||

| NPSI total score | 40.5 (16.8) | 35.6 (17.7) | ||||

Note: Pain intensity for evoked and spontaneous pain was scored by the 0–10 NRS. At the respective baseline, pain scores were similar between treatment periods 1 and 2. Pinprick pain was evoked by either 8 or 16 mN, based on body location. Neuropathic pain symptom inventory (NPSI) is a self-reported questionnaire. SD depicts standard deviation.

The primary endpoint was the change from baseline in evoked pain defined as the most painful of the pinprick, cold (6°C) and brush stimuli, with a negative change from baseline reflecting an improvement for the patient.

A mean treatment difference of 0.63 (95% CI −1.26, 2.53) was observed between the ACD440 gel and the placebo gel (ACD440 minus placebo within-subject difference in change from baseline), p = 757. Hence a placebo effect of similar magnitude to the observed treatment effect was seen.

A summary of all pre-planned primary and secondary evoked pain results is shown in Table 3.

Study results for the pre-planned primary and secondary evoked pain endpoints and the spontaneous 24 h pain recall endpoint

| Assessment | ACD440 | Placebo | Difference |

|---|---|---|---|

| (N = 14) | (N = 14) | ACD440 – Placebo | |

| Mean value (95% CI) | Mean value (95% CI) | Mean value (95%CI) | |

| Primary endpoint: Worst evoked pain | −1.80 (−3.07, −0.53) | −2.43 (−4.16, −0.70) | 0.63 (−1.26, 2.53) (one-sided p = 0.7570) |

| Spontaneous pain intensity by 24 h recall | 0.21 (−0.72, 1.15) | −0.93 (−1.90, 0.04) | 1.14 (0.01, 2.27) |

| Average evoked pain | −1.13 ( −2.20, −0.05) | −0.71 (−1.46, 0.03) | −0.41 (−1.35, 0.52) |

Note: All of these analyses were based on change from baseline for each individual treatment period. A negative change from baseline corresponds to a reduction in pain intensity score by the 0-10 NRS. Pinprick pain was evoked by either 8 or 16 mN, based on body location.

Exploratory analyses were also performed on the four individual suprathreshold sensory assessments; brush allodynia, pinprick-evoked pain, heat-evoked pain and cold-evoked pain. Changes from baseline in heat-evoked pain thresholds were significantly different between treatment groups: mean −1.79 (95% CI −3.56, −0.01) with CD440 versus 0.43 (95% CI −1.29, 2.15) with placebo, one-sided p-value 0.0117 (Table 4).

Exploratory analyses of bedside evoked pain

| ACD440 mean (95% CI) | Placebo mean (95% CI) | One-sided p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| All patients both periods ( N = 14, crossover) | |||

| Heat-evoked pain (40°C) | −1.79 (−3.56, −0.01) | 0.43 (−1.29, 2.15) | 0.0117 |

| Cold-evoked pain (6°C) | −0.79 (−1.94, 0.37) | 0.07 (−1.24, 1.38) | 0.2471 |

| Brush allodynia | −0.64 (−1.88, 0.59) | −0.43 (−2.03, 1.17) | 0.3550 |

| Pinprick-evoked pain | −1.29 (−2.67, 0.10) | −2.93 (−4.70, −1.15) | 0.9351 |

| All patients period 1 ( N * = 7 + 7) | |||

| Worst evoked pain | −3.07 (−5.21, −0.93) | −2.86 (−5.48, −0.23) | 0.7235 |

| Average evoked pain | −2.07 (−4.18, 0.03) | −0.46 (−1.75, 0.83) | 0.0670 |

| Heat-evoked pain (40°C) | −2.86 (−6.42, 0.70) | 2.14 (−0.15, 4.44) | 0.0058 |

| Cold-evoked pain (6°C) | −1.29 (−3.60, 1.02) | −0.57 (−3.34, 2.20) | 0.2990 |

| Brush allodynia | −1.57 (−4.12, 0.98) | −0.14 (−3.45, 3.17) | 0.1987 |

| Pinprick-evoked pain | −2.57 (−5.18, 0.04) | −3.29 (−6.20, −0.38) | 0.7005 |

| Thermal hyperalgesia patients ( N * = 5 + 7) | |||

| Average evoked pain | −2.85 (−5.61, −0.09) | −0.46 (−1.75, 0.83) | 0.02335 |

| Heat-evoked pain (40°C) | −4.0 (−9.0, 1.0) | 2.1 (−0.1, 4.4) | 0.00505 |

| Cold-evoked pain (6°C) | −1.80 (−5.36, 1.76) | −0.57 (−3.34, 2.20) | 0.2519 |

| Brush allodynia | −2.80 (−5.19, −0.41) | −0.14 (−3.45, 3.17) | 0.10605 |

| Pinprick-evoked pain | −2.80 (−6.96, 1.36) | −3.29 (−6.20, −0.38) | 0.6414 |

| Heat hyperalgesia patients ( N * = 4 + 3) | |||

| Average evoked pain | −3.38 (−6.84, 0.09) | −0.50 (−3.35, 2.35) | 0.05715 |

| Heat-evoked pain (40°C) | −5.0 (−11.2, 1.2) | 1.3 (−1.5, 4.2) | 0.02855 |

| Cold-evoked pain (6°C) | −2.25 (−7.18, 2.68) | 1.00 (−1.48, 3.48) | 0.12855 |

| Brush allodynia | −3.50 (−5.55, −1.45) | −0.67 (−10.71, 9.37) | 0.22855 |

| Pinprick-evoked pain | −2.75 (−8.90, 3.40) | −3.67 (−7.46, 0.13) | 0.6857 |

| Non-thermal hyperalgesia patients ( N * = 2 + 0) | |||

| Average evoked pain | −0.13 (−8.07, 7.82) | ||

| Heat-evoked pain (40°C) | 0.0000 (0.0000, 0.0000) | — | — |

| Cold-evoked pain (6°C) | 0.0000 (0.0000, 0.0000) | — | — |

| Brush allodynia | 1.50 (−17.56, 20.56) | — | — |

| Pinprick-evoked pain | −2.00 (−14.71, 10.71) | — | — |

Note: A negative change from baseline corresponds to a reduction in pain. Worst evoked pain depicts the highest pain intensity of suprathreshold stimulation of the worst of brush allodynia, pinprick-evoked pain, and cold-evoked pain. Average evoked pain depicts the average pain intensity of brush allodynia, pinprick-evoked pain, heat-evoked pain, and cold-evoked pain. Pinprick pain was evoked by either 8 or 16 mN, based on body location. *depicts number of ACD440 patients + placebo patients.

The analysis of the primary endpoint was affected by a sizeable treatment period effect. In patients administered ACD440 in treatment period 1 the mean within-subject difference in change from baseline of evoked pain was −1.07 (95% CI −3.04, 0.90), while when ACD440 was administered in treatment period 2, the mean within-subject difference was 2.33 (95% CI −0.88, 5.54). Therefore, post hoc analyses were carried out, including only the data from the first treatment period.

3.1.1 Efficacy in period 1

Analyses within the first treatment period are based on the 7 patients having received placebo gel and 7 having received ACD440 Gel, thus as parallel groups. Just like in the primary analysis, no significant difference was shown between the changes from baseline in evoked pain at Day 7 after receiving ACD440 compared to placebo (one-sided p = 0.7235), Table 4.

In spite of the sample size being based on previous data on reduction of heat induced pain, the heat-evoked pain intensity as part of the primary endpoint was by mistake omitted from the study protocol, and thus heat-evoked pain was not part of the planned primary analysis. One secondary endpoint, the change from baseline in average evoked pain (the average of brush allodynia, pinprick-evoked pain, heat-evoked pain and cold-evoked pain) showed promising results within period 1 with mean −2.07 (95% CI −4.18, 0.03) in ACD440 patients and −0.46 (95% CI −1.75, 0.83) in placebo patients, one-sided p = 0.0670. Analyses of all individual suprathreshold sensory assessments from Period 1 were carried out on the 7 + 7 subjects (Table 4). These analyses revealed a significant difference in heat-evoked pain with mean change from baseline −2.86 (95% CI −6.42, 0.70) in ACD440 subjects and 2.14 (95% CI −0.15, 4.44) in placebo subjects (one-sided p = 0.0058). No other individual suprathreshold sensory assessment showed significant differences between treatment groups.

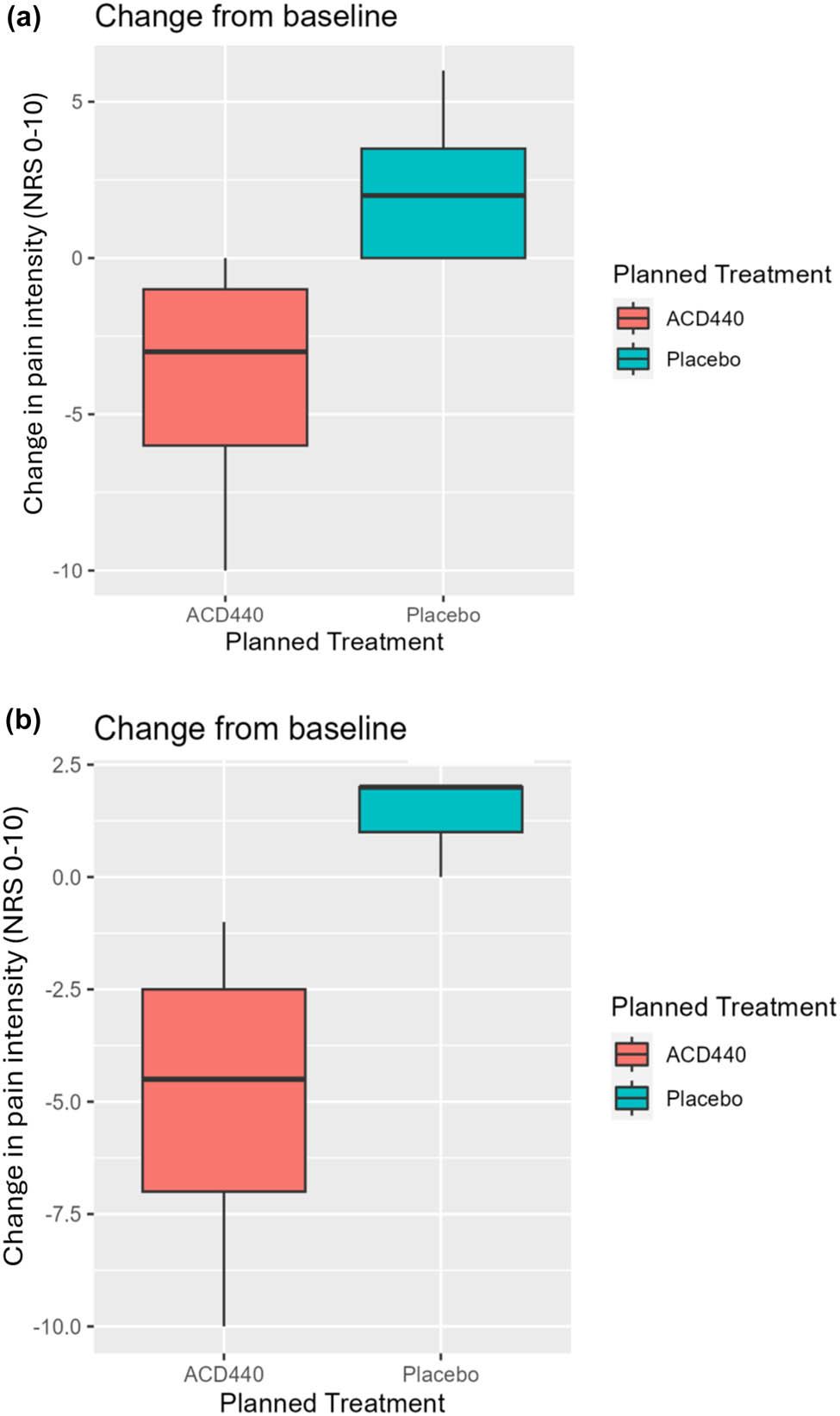

The four individual suprathreshold sensory assessments from Period 1 were further analysed within the subsets of subjects with heat induced hyperalgesia, thermal hyperalgesia, and non-thermal hyperalgesia. Patients with thermal hyperalgesia responded significantly better to ACD440 than to placebo towards heat-evoked pain, with mean change from baseline −4.0 (95% CI −9.0, 1.0, N = 5) in the former group and 2.1 (95% CI −0.1, 4.4, N = 7) in the latter (one-sided p = 0.00505), Figure 3a. The thermal hyperalgesia subjects consist of subjects with heat or cold hyperalgesia at baseline. The difference in response to heat-evoked pain is also statistically significant looking only within the heat hyperalgesia subjects, mean change from baseline −5.0 (95% CI −11.2, 1.2, N = 4) in ACD440 subjects and 1.3 (95% CI −1.5, 4.2, N = 3) in placebo subjects, Figure 3b.

The Y-axes show change from baseline in heat-evoked pain, for which a negative value reflects a response. NRS: Numerical rating scale. (a) Patients demonstrating thermal hyperalgesia at baseline responded significantly better to ACD440 Gel (N = 5) vs placebo gel (N = 7) on change from baseline in heat-evoked pain, one-sided p = 0.00505. (b) Patients demonstrating heat hyperalgesia at baseline responded significantly better to ACD440 Gel vs placebo gel on change from baseline in heat-evoked pain, one-sided p = 0.02855.

3.1.2 Patient reported outcomes

Neuropathic Pain Symptom Inventory (NPSI): At the ACD440 Gel baseline assessments, the NPSI total score mean was 36.71 (SD 18.76), and at the placebo gel baseline the mean was 39.36 (SD 17.27).

Instead, considering only the period baselines, independent of treatment allocation, at the Period 1 baseline, the mean NPSI score was 40.5 (SD 17.4) which was not different to the period 2 baseline, 35.6 (SD 18.3). (There was also no difference in mean change from baseline between ACD440 Gel and placebo gel, mean 9.79 (SD 14.53; 95% CI 1.40, 18.17).

Patient Global Impression of Pain (PGIC): There was no difference between treatments at Day 7 in either treatment period. There was no difference between ACD440 Gel, (mean 3.86, SD 1.10) and placebo (mean 4.71, SD 1.33) on Day 7, mean −0.86 (SD 1.61; 95% CI −1.79, 0.07).

3.1.3 Pharmacokinetics

Blood samples were collected at the baseline visit before each study treatment period, and on the last day of each treatment period. Samples have been saved in a biobank for later analysis.

3.2 Safety

There were 6 AEs reported by 6 out of the 14 subjects (42.9%). All AEs were of mild intensity and were assessed as unlikely to be related to the study treatment. The AEs were equally reported between the two treatments (ACD440 and placebo), and include one case each of atrial fibrillation, nausea, nasopharyngitis, cough, rash, and worsened pain. There were no AEs related to abnormal laboratory values, vital signs, or other safety assessments.

4 Discussion

The present exploratory Phase 2a, randomized, single-centre, double-blind, placebo-controlled crossover study was conducted in patients with chronic PNP with sensory hypersensitivity. The study failed to reach a significant treatment effect on the primary variable, i.e. reduction in evoked pain in the sensory domain where the participant reported his/her worst pain during the respective baseline assessment. This was considered to be due to a statistically significant period effect. Therefore, a secondary analysis including only data from the first treatment period (seven participants receiving ACD440 Gel and seven participants receiving placebo) was conducted, which shows that there was a significant reduction in pain evoked by suprathreshold heat stimulation by topical application of ACD440 Gel vs placebo gel. In a subsequent post hoc analysis, including only patients presenting with thermal hyperalgesia at the screening visit, the effect was even greater. This data altogether confirms that the gel formulation effectively penetrates the skin surface and reaches the target of TRPV1 receptors. The current results should therefore be interpreted as a successful translation from healthy subject proof-of-mechanism [14] to proof-of-mechanism in chronic PNP patients. The overall treatment effect suggests that ACD440 Gel may be effective in reducing pain where TRPV1 receptor mechanisms are important in the initiation or maintenance of pain, e.g. to heat-evoked pain.

Overall, the study did not demonstrate efficacy of ACD440 in reducing pain evoked by brush stroke, or by suprathreshold cold or pinprick stimulation. However, reduction in suprathreshold temperature evoked pain in general was significantly larger after ACD440 Gel was applied compared to placebo gel.

Considering the significant period effect seen in this study, this may be seen as a limitation of the study. In clinical trials of analgesics, placebo responses in reported pain intensity are often substantial. Well-known factors affecting the placebo response include frequent site visits [24]. These were challenging to avoid in this short trial. Also, the investigator–patient personal interactions are known to increase the risk of a placebo effect. A further very important factor may well be the possibility of potentially receiving an efficacious treatment after several failed treatment attempts. Any study design must be aware of these risks and avoid them as best as possible. It could be expected that a randomized crossover study design could reduce some of these sources, but as evident from this and other studies [25], other factors than randomization do play a role here, as seen by the clearer results in the period-1 only analyses. Of course, any carryover effects, with remaining drug effects not being sufficiently washed out would affect the outcome, though this is highly unlikely in the present trial. In order to avoid the natural variability in pain intensity over time, the present study had individual baseline data for the respective treatment periods. The findings of the present trial are also aligned with analyses of Gillving and coauthors, demonstrating that placebo responses in a crossover trial do not seem to be associated with age, sex, duration of pain, sensory profile, or treatment sequence [26].

In this study, we could not detect any change in overall spontaneous pain nor NSPI or its sub-scores. This may be due to the short study treatment duration and small sample size, neither overall spontaneous pain nor NSPI overall or its subscores were expected to change over the 7-day treatment duration. The response to a questionnaire interrogating about perceived evoked pain, may of course be impacted by the participant’s avoidance of any known painful stimuli. Further, the NPSI does not include any question regarding heat evoked pain. As demonstrated by Vollert et al. [7], the sample size for a clinical trial based on a phenotype stratification, including patients with heat hyperalgesia, would require screening of close to 100 patients for a crossover trial, and be predominantly of an aetiology that is not painful diabetic polyneuropathy. In published data on treatments for neuropathic pain, whether topical or systemic (duloxetine), the first efficacy signal of a clinically relevant magnitude was not detected until after 3–4 weeks of treatment [27,28]. In a clinical healthcare situation, around 6 weeks is a standard treatment duration of trying out the treatment response of a new treatment [29]. Thus, the overall analgesic effect of ACD440 Gel needs to be further evaluated in larger trials of a longer treatment duration, in order to evaluate the optimal segment of patients who would benefit from treatment with a topical TRPV1 receptor antagonist.

The self-reported NPSI questionnaire is an instrument designed as a tool to screen for possible neuropathic pain, and thus for use across neuropathic pain patients. Not all aspects that it addresses relates to the phenotypic phenomena linked to PNP with sensory hypersensitivity. In addition, it must be noted, that the questions in the NPSI asks about the subjective perception of the respective phenomenon during the last 24 h, not a standardized assessment. In daily life, provocations known to be painful could be wilfully avoided, or unwilfully more forceful, the NPSI hence displays a score that is not directly comparable to the standardized testing situation. Based on the specific phenomena addressed by a topical study treatment, only affecting pain related to the presence of nerve endings in the epidermal tissue [8], only a subset of the NPSI self-reported items related to evoked pains were of direct interest and utilized in this study, namely, questions 8–10.

Topical treatment with patches of the TRPV1 receptor agonist Qutenza® (capsaicin 8%, Grünenthal GmbH) has demonstrated good overall analgesic efficacy in PNP, with a duration of 3 months. However, the overall numbers-needed-to-treat is on average 11 [30], meaning that a limited proportion of study participants had a very good treatment response. These treatments require application in-house in a healthcare setting, as the application of the patch is painful and often requires complementary analgesics. Furthermore, the healthcare professional administering the treatment needs to use protective gear. Thus, a topical treatment without any demonstrated side effects would constitute a favourable treatment option.

Interestingly, an analysis of response predictors to the 8% capsaicin patch identified lack of peripheral hypersensitivity, in addition to pain intensity of ≤4/10 as positive predictors, rather than a phenotype representative of a high presence of TRPV1-receptors [31].

The topic of personalized treatment has become of increasing interest, because of the high failure rate in the development of new treatments for chronic pain with few drugs providing a sufficient analgesia. A wide array of incompletely understood mechanisms behind different aspects of PNP may likely be the reason for the low focus on providing a personalized treatment. The challenge of different underlying mechanisms, phenotypes, and possibly also of different underlying aetiologies are discussed by Vollert et al. and by Finnerup et al. [7,8].

Within the patient population of peripheral chronic neuropathic pain, the subgroup expressing a thermal hypersensitivity constitutes a minority of patients, for whom the specific therapeutic options are very limited. These patients, who can be identified with a simple bedside test can be expected to be especially benefited by a topical TRPV1-receptor antagonist, as a monotherapy or in addition to other analgesics.

A topical treatment with a TRPV1-antagonist such as ACD440 Gel has potential as a treatment for chronic PNP with hypersensitivity, as well as for other dermatological indications, e.g. painful skin diseases, chronic itch, pain, and itch in psoriasis. Based on the successful early development of Novartis’ TRPV1 antagonist libvatrep being developed for the topical treatment of postoperative and chronic corneal pain, this could also be a future avenue [32].

Taken together, and notwithstanding the placebo and treatment period effect, the data in this study suggest that ACD440 is safe and well tolerated in the patient population and supports the use of an extended treatment period in future studies. The data also suggest that ACD440 may have a beneficial effect on sensitivity to temperature-evoked pain in PNP patients with thermal hypersensitivity.

5 Conclusion

ACD440 Gel (14 mg/g) significantly reduced pain evoked by suprathreshold thermal stimulation in patients with chronic PNP of different aetiologies, displaying sensory hypersensitivity, mostly patients with refractory pain after postherpetic neuralgia. The positive results support further clinical development of ACD440 Gel as a future treatment of PNP with predictive response in a specific pain phenotype with preserved nociceptors demonstrating a sensory thermal hyperalgesia, or potentially other painful skin conditions.

Acknowledgements

We wish to thank RN Rezvan Kiani and Dr Martin Flores Bjurström (sub-investigator) for their valuable contribution to the conducted study.

-

Research ethics: The study was conducted at a single site, Multidisciplinary Pain Centre at Uppsala University Hospital, Uppsala, Sweden, in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki as adopted by the World Medical Association in 1964, and lastly amended in 2013. The study was conducted in accordance with Good Clinical Practice, after regulatory approval by the Swedish MPA (EudraCT 2022-000902-82) and ethics approval by the Swedish SERA (no. 2022-01922-01). The study was preregistered on www.clinicaltrials.gov (NCT05416931).

-

Informed consent: Informed consent was obtained from all participants in this study prior to taking part in any study related procedures.

-

Author contributions: All authors commented on the manuscript. All authors have accepted responsibility for the entire content of this manuscript and approved its submission. M.S., R.K., I.L., and M.M.H. contributed to study design, data, and result interpretation and critical review of the manuscript. A.M. contributed to study execution, data, and result interpretation and critical review of the manuscript.

-

Competing interests: M.S. is an employee of AlzeCure Pharma AB, M.M.H. and I.L. are consultants working for AlzeCure Pharma AB. M.S. is a member of the Editorial Board of the Scandinavian Journal of Pain. A.M. is the principal investigator. R.K. is a scientific advisor to AlzeCure Pharma AB. A.M. is the principal investigator. R.K. is a scientific advisor to AlzeCure Pharma AB.

-

Research funding: This study was fully sponsored by AlzeCure Pharma AB.

-

Data availability: The original data from this study is under the proprietary ownership of AlzeCure Pharma AB and subject to business confidentiality. Requests may be sent to info@alzecurepharma.com.

-

Artificial Intelligence/Machine learning tools: Not applicable.

References

[1] International Association for the Study of Pain. Pain terms and definitions. 2011. https://www.iasp-pain.org/resources/terminology/ Accessed on February 10, 2025.Suche in Google Scholar

[2] van Hecke O, Austin SK, Khan RA, Smith BH, Torrance N. Neuropathic pain in the general population: A systematic review of epidemiological studies. Pain. 2014 Apr;155(4):654–62. 10.1016/j.pain.2013.11.013. Epub 2013 Nov 26. Erratum in: Pain. 2014 Sep;155(9):1907. PMID: 24291734.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[3] Failde I, Dueñas M, Ribera MV, Gálvez R, Mico JA, Salazar A, et al. Prevalence of central and peripheral neuropathic pain in patients attending pain clinics in Spain: Factors related to intensity of pain and quality of life. J Pain Res. 2018 Sep;11:1835–47. 10.2147/JPR.S159729. Erratum in: J Pain Res. 2018 Oct 17;11:2397. PMID: 30254486; PMCID: PMC6140696.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[4] O’Connor AB. Neuropathic pain: quality-of-life impact, costs and cost effectiveness of therapy. Pharmacoeconomics. 2009;27(2):95–112. 10.2165/00019053-200927020-00002. PMID: 19254044.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[5] Tarride JE, Moulin DE, Lynch M, Clark AJ, Stitt L, Gordon A, et al. Impact on health-related quality of life and costs of managing chronic neuropathic pain in academic pain centres: Results from a one-year prospective observational Canadian study. Pain Res Manag. 2015 Nov-Dec;20(6):327–33. 10.1155/2015/214873. Epub 2015 Oct 16. PMID: 26474381; PMCID: PMC4676504.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[6] Baron R, Maier C, Attal N, Binder A, Bouhassira D, Cruccu G, et al. German Neuropathic Pain Research Network (DFNS), and the EUROPAIN, and NEUROPAIN consortia. Peripheral neuropathic pain: A mechanism-related organizing principle based on sensory profiles. Pain. 2017 Feb;158(2):261–72. 10.1097/j.pain.0000000000000753. PMID: 27893485; PMCID: PMC5266425.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[7] Vollert J, Attal N, Baron R, Freynhagen R, Haanpää M, Hansson P, et al. Quantitative sensory testing using DFNS protocol in Europe: an evaluation of heterogeneity across multiple centers in patients with peripheral neuropathic pain and healthy subjects. Pain. 2016;157:750–8. 10.1097/j.pain.0000000000000433.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[8] Finnerup NB, Kuner R, Jensen TS. Neuropathic pain: From mechanisms to treatment. Physiol Rev. 2021 Jan;101(1):259–301. 10.1152/physrev.00045.2019. Epub 2020 Jun 25. PMID: 32584191.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[9] Caterina MJ, Schumacher MA, Tominaga M, Rosen TA, Levine JD, Julius D. The capsaicin receptor: a heat-activated ion channel in the pain pathway. Nature. 1997 Oct;389(6653):816–24. 10.1038/39807. PMID: 9349813.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[10] Caterina MJ, Leffler A, Malmberg AB, Martin WJ, Trafton J, Petersen-Zeitz KR, et al. Impaired nociception and pain sensation in mice lacking the capsaicin receptor. Science. 2000 Apr;288(5464):306–13. 10.1126/science.288.5464.306. PMID: 10764638.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[11] Petersen KL, Rice FL, Suess F, Berro M, Rowbotham MC. Relief of post-herpetic neuralgia by surgical removal of painful skin. Pain. 2002 Jul;98(1–2):119–26. 10.1016/s0304-3959(02)00029-5. PMID: 12098623.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[12] Chizh BA, O’Donnell MB, Napolitano A, Wang J, Brooke AC, Aylott MC, et al. The effects of the TRPV1 antagonist SB-705498 on TRPV1 receptor-mediated activity and inflammatory hyperalgesia in humans. Pain. 2007 Nov;132(1–2):132–41. 10.1016/j.pain.2007.06.006.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[13] Quiding H, Jonzon B, Svensson O, Webster L, Reimfelt A, Karin A, et al. TRPV1 antagonistic analgesic effect: A randomized study of AZD1386 in pain after third molar extraction. Pain. 2013 Jun;154(6):808–12. 10.1016/j.pain.2013.02.004. Epub 2013 Feb 19. PMID: 23541425.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[14] Rowbotham MC, Nothaft W, Duan RW, Wang Y, Faltynek C, McGaraughty S, et al. Oral and cutaneous thermosensory profile of selective TRPV1 inhibition by ABT-102 in a randomized healthy volunteer trial. Pain. 2011 May;152(5):1192–200. 10.1016/j.pain.2011.01.051. Epub 2011 Mar 4. PMID: 21377273.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[15] Kort ME, Kym PR. TRPV1 antagonists: Clinical setbacks and prospects for future development. Prog Med Chem. 2012;51:57–70. 10.1016/B978-0-12-396493-9.00002-9. PMID: 22520471.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[16] Yue WWS, Yuan L, Braz JM, Basbaum AI, Julius D. TRPV1 drugs alter core body temperature via central projections of primary afferent sensory neurons. Elife. 2022 Aug;11:e80139. 10.7554/eLife.80139.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[17] Segerdahl M, Rother M, Halldin MM, Popescu T, Schaffler K. Topically applied novel TRPV1 receptor antagonist, ACD440 Gel, reduces evoked pain in healthy volunteers, a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, crossover study. Eur J Pain. 2024 Nov;28(10):1656–73. 10.1002/ejp.2299. Epub 2024 Jun 12. PMID: 38864733.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[18] Reimer M, Forstenpointner J, Hartmann A, Otto JC, Vollert J, Gierthmühlen J, et al. Sensory bedside testing: A simple stratification approach for sensory phenotyping. Pain Rep. 2020;5:e820. 10.1097/PR9.0000000000000820.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[19] Koulouris AE, Edwards RR, Dorado K, Schreiber KL, Lazaridou A, Rajan S, et al. Reliability and validity of the boston bedside quantitative sensory testing battery for neuropathic pain. Pain Med. 2020 Oct;21(10):2336–47. 10.1093/pm/pnaa192. PMID: 32895703; PMCID: PMC7593797.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[20] Rolke R, Magerl W, Campbell KA, Schalber C, Caspari S, Birklein F, et al. Quantitative sensory testing: A comprehensive protocol for clinical trials. Eur J Pain. 2006 Jan;10(1):77–88. 10.1016/j.ejpain.2005.02.003. PMID: 16291301.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[21] Pfau DB, Krumova EK, Treede RD, Baron R, Toelle T, Birklein F, et al. Quantitative sensory testing in the German Research Network on Neuropathic Pain (DFNS): Reference data for the trunk and application in patients with chronic postherpetic neuralgia. Pain. 2014 May;155(5):1002–15. 10.1016/j.pain.2014.02.004. Epub 2014 Feb 10. PMID: 24525274.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[22] Freeman R, Baron R, Bouhassira D, Cabrera J, Emir B. Sensory profiles of patients with neuropathic pain based on the neuropathic pain symptoms and signs. Pain. 2014 Feb;155(2):367–76. 10.1016/j.pain.2013.10.023. Epub 2013 Oct 25. PMID: 24472518.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[23] Bouhassira D, Attal N, Fermanian J, Alchaar H, Gautron M, Masquelier E, et al. Development and validation of the Neuropathic Pain Symptom Inventory. Pain. 2004 Apr;108(3):248–57. 10.1016/j.pain.2003.12.024. PMID: 15030944.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[24] Vase L, Petersen GL, Lund K. Placebo effects in idiopathic and neuropathic pain conditions. Handb Exp Pharmacol. 2014;225:121–36. 10.1007/978-3-662-44519-8_7.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[25] Demant DT, Lund K, Vollert J, Maier C, Segerdahl M, Finnerup NB, et al. The effect of oxcarbazepine in peripheral neuropathic pain depends on pain phenotype: A randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled phenotype-stratified study. Pain. 2014 Nov;155(11):2263–73. 10.1016/j.pain.2014.08.014. Epub 2014 Aug 17. PMID: 25139589.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[26] Gillving M, Demant D, Lund K, Holbech J, Otto M, Vase L, et al. Factors with impact on magnitude of the placebo response in randomized, controlled, cross-over trials in peripheral neuropathic pain. Pain. Dec 2020;161(12):2731–6. 10.1097/j.pain.0000000000001964.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[27] Galer BS, Rowbotham MC, Perander J, Friedman E. Topical lidocaine patch relieves postherpetic neuralgia more effectively than a vehicle topical patch: results of an enriched enrollment study. Pain. 1999 Apr;80(3):533–8. 10.1016/S0304-3959(98)00244-9. PMID: 10342414.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[28] Pritchett YL, McCarberg BH, Watkin JG, Robinson MJ. Duloxetine for the management of diabetic peripheral neuropathic pain: response profile. Pain Med. 2007 Jul-Aug;8(5):397–409. 10.1111/j.1526-4637.2007.00305.x. PMID:17661853.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[29] Freynhagen R, Baron R, Kawaguchi Y, Malik RA, Martire DL, Parsons B, et al. Pregabalin for neuropathic pain in primary care settings: Recommendations for dosing and titration. Postgrad Med. 2021 Jan;133(1):1–9. 10.1080/00325481.2020.1857992. PMID: 33423590.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[30] Derry S, Wiffen PJ, Kalso EA, Bell RF, Aldington D, Phillips T, et al. Topical analgesics for acute and chronic pain in adults - an overview of Cochrane Reviews. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017 May;5(5):CD008609. 10.1002/14651858.CD008609.pub2.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[31] Katz NP, Mou J, Paillard F, Turnbull B, Trudeau J, Stoker M. Predictors of response in patients with postherpetic neuralgia and HIV-associated neuropathy treated with the 8% capsaicin patch (Qutenza). Clin J Pain. Oct 2015;31(10):859–66. 10.1097/AJP.0000000000000186.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[32] Thompson V, Moshirfar M, Clinch T, Scoper S, Linn SH, McIntosh A, et al. Topical ocular TRPV1 antagonist SAF312 (Libvatrep) for postoperative pain after photorefractive keratectomy. Transl Vis Sci Technol. 2023 Mar;12(3):7. 10.1167/tvst.12.3.7.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

© 2025 the author(s), published by De Gruyter

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Editorial Comment

- Abstracts presented at SASP 2025, Reykjavik, Iceland. From the Test Tube to the Clinic – Applying the Science

- Quantitative sensory testing – Quo Vadis?

- Stellate ganglion block for mental disorders – too good to be true?

- When pain meets hope: Case report of a suspended assisted suicide trajectory in phantom limb pain and its broader biopsychosocial implications

- Transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation – an important tool in person-centered multimodal analgesia

- Clinical Pain Researches

- Exploring the complexities of chronic pain: The ICEPAIN study on prevalence, lifestyle factors, and quality of life in a general population

- The effect of peer group management intervention on chronic pain intensity, number of areas of pain, and pain self-efficacy

- Effects of symbolic function on pain experience and vocational outcome in patients with chronic neck pain referred to the evaluation of surgical intervention: 6-year follow-up

- Experiences of cross-sectoral collaboration between social security service and healthcare service for patients with chronic pain – a qualitative study

- Completion of the PainData questionnaire – A qualitative study of patients’ experiences

- Pain trajectories and exercise-induced pain during 16 weeks of high-load or low-load shoulder exercise in patients with hypermobile shoulders: A secondary analysis of a randomized controlled trial

- Pain intensity in anatomical regions in relation to psychological factors in hypermobile Ehlers–Danlos syndrome

- Opioid use at admittance increases need for intrahospital specialized pain service: Evidence from a registry-based study in four Norwegian university hospitals

- Topically applied novel TRPV1 receptor antagonist, ACD440 Gel, reduces temperature-evoked pain in patients with peripheral neuropathic pain with sensory hypersensitivity, a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, crossover study

- Pain and health-related quality of life among women of childbearing age in Iceland: ICEPAIN, a nationwide survey

- A feasibility study of a co-developed, multidisciplinary, tailored intervention for chronic pain management in municipal healthcare services

- Healthcare utilization and resource distribution before and after interdisciplinary pain rehabilitation in primary care

- Measurement properties of the Swedish Brief Pain Coping Inventory-2 in patients seeking primary care physiotherapy for musculoskeletal pain

- Understanding the experiences of Canadian military veterans participating in aquatic exercise for musculoskeletal pain

- “There is generally no focus on my pain from the healthcare staff”: A qualitative study exploring the perspective of patients with Parkinson’s disease

- Observational Studies

- Association between clinical laboratory indicators and WOMAC scores in Qatar Biobank participants: The impact of testosterone and fibrinogen on pain, stiffness, and functional limitation

- Well-being in pain questionnaire: A novel, reliable, and valid tool for assessment of the personal well-being in individuals with chronic low back pain

- Properties of pain catastrophizing scale amongst patients with carpal tunnel syndrome – Item response theory analysis

- Adding information on multisite and widespread pain to the STarT back screening tool when identifying low back pain patients at risk of worse prognosis

- The neuromodulation registry survey: A web-based survey to identify and describe characteristics of European medical patient registries for neuromodulation therapies in chronic pain treatment

- A biopsychosocial content analysis of Dutch rehabilitation and anaesthesiology websites for patients with non-specific neck, back, and chronic pain

- Topical Reviews

- An action plan: The Swedish healthcare pathway for adults with chronic pain

- Team-based rehabilitation in primary care for patients with musculoskeletal disorders: Experiences, effect, and process evaluation. A PhD synopsis

- Persistent severe pain following groin hernia repair: Somatosensory profiles, pain trajectories, and clinical outcomes – Synopsis of a PhD thesis

- Systematic Reviews

- Effectiveness of non-invasive vagus nerve stimulation vs heart rate variability biofeedback interventions for chronic pain conditions: A systematic review

- A scoping review of the effectiveness of underwater treadmill exercise in clinical trials of chronic pain

- Neural networks involved in painful diabetic neuropathy: A systematic review

- Original Experimental

- Knowledge, attitudes, and practices of transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation in perioperative care: A Swedish web-based survey

- Impact of respiration on abdominal pain thresholds in healthy subjects – A pilot study

- Measuring pain intensity in categories through a novel electronic device during experimental cold-induced pain

- Robustness of the cold pressor test: Study across geographic locations on pain perception and tolerance

- Experimental partial-night sleep restriction increases pain sensitivity, but does not alter inflammatory plasma biomarkers

- Is it personality or genes? – A secondary analysis on a randomized controlled trial investigating responsiveness to placebo analgesia

- Investigation of endocannabinoids in plasma and their correlation with physical fitness and resting state functional connectivity of the periaqueductal grey in women with fibromyalgia: An exploratory secondary study

- Educational Case Reports

- Stellate ganglion block in disparate treatment-resistant mental health disorders: A case series

- Regaining the intention to live after relief of intractable phantom limb pain: A case study

- Trigeminal neuralgia caused by dolichoectatic vertebral artery: Reports of two cases

- Short Communications

- Neuroinflammation in chronic pain: Myth or reality?

- The use of registry data to assess clinical hunches: An example from the Swedish quality registry for pain rehabilitation

- Letter to the Editor

- Letter to the Editor For: “Stellate ganglion block in disparate treatment-resistant mental health disorders: A case series”

- Corrigendum

- Corrigendum to “Patient characteristics in relation to opioid exposure in a chronic non-cancer pain population”

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Editorial Comment

- Abstracts presented at SASP 2025, Reykjavik, Iceland. From the Test Tube to the Clinic – Applying the Science

- Quantitative sensory testing – Quo Vadis?

- Stellate ganglion block for mental disorders – too good to be true?

- When pain meets hope: Case report of a suspended assisted suicide trajectory in phantom limb pain and its broader biopsychosocial implications

- Transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation – an important tool in person-centered multimodal analgesia

- Clinical Pain Researches

- Exploring the complexities of chronic pain: The ICEPAIN study on prevalence, lifestyle factors, and quality of life in a general population

- The effect of peer group management intervention on chronic pain intensity, number of areas of pain, and pain self-efficacy

- Effects of symbolic function on pain experience and vocational outcome in patients with chronic neck pain referred to the evaluation of surgical intervention: 6-year follow-up

- Experiences of cross-sectoral collaboration between social security service and healthcare service for patients with chronic pain – a qualitative study

- Completion of the PainData questionnaire – A qualitative study of patients’ experiences

- Pain trajectories and exercise-induced pain during 16 weeks of high-load or low-load shoulder exercise in patients with hypermobile shoulders: A secondary analysis of a randomized controlled trial

- Pain intensity in anatomical regions in relation to psychological factors in hypermobile Ehlers–Danlos syndrome

- Opioid use at admittance increases need for intrahospital specialized pain service: Evidence from a registry-based study in four Norwegian university hospitals

- Topically applied novel TRPV1 receptor antagonist, ACD440 Gel, reduces temperature-evoked pain in patients with peripheral neuropathic pain with sensory hypersensitivity, a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, crossover study

- Pain and health-related quality of life among women of childbearing age in Iceland: ICEPAIN, a nationwide survey

- A feasibility study of a co-developed, multidisciplinary, tailored intervention for chronic pain management in municipal healthcare services

- Healthcare utilization and resource distribution before and after interdisciplinary pain rehabilitation in primary care

- Measurement properties of the Swedish Brief Pain Coping Inventory-2 in patients seeking primary care physiotherapy for musculoskeletal pain

- Understanding the experiences of Canadian military veterans participating in aquatic exercise for musculoskeletal pain

- “There is generally no focus on my pain from the healthcare staff”: A qualitative study exploring the perspective of patients with Parkinson’s disease

- Observational Studies

- Association between clinical laboratory indicators and WOMAC scores in Qatar Biobank participants: The impact of testosterone and fibrinogen on pain, stiffness, and functional limitation

- Well-being in pain questionnaire: A novel, reliable, and valid tool for assessment of the personal well-being in individuals with chronic low back pain

- Properties of pain catastrophizing scale amongst patients with carpal tunnel syndrome – Item response theory analysis

- Adding information on multisite and widespread pain to the STarT back screening tool when identifying low back pain patients at risk of worse prognosis

- The neuromodulation registry survey: A web-based survey to identify and describe characteristics of European medical patient registries for neuromodulation therapies in chronic pain treatment

- A biopsychosocial content analysis of Dutch rehabilitation and anaesthesiology websites for patients with non-specific neck, back, and chronic pain

- Topical Reviews

- An action plan: The Swedish healthcare pathway for adults with chronic pain

- Team-based rehabilitation in primary care for patients with musculoskeletal disorders: Experiences, effect, and process evaluation. A PhD synopsis

- Persistent severe pain following groin hernia repair: Somatosensory profiles, pain trajectories, and clinical outcomes – Synopsis of a PhD thesis

- Systematic Reviews

- Effectiveness of non-invasive vagus nerve stimulation vs heart rate variability biofeedback interventions for chronic pain conditions: A systematic review

- A scoping review of the effectiveness of underwater treadmill exercise in clinical trials of chronic pain

- Neural networks involved in painful diabetic neuropathy: A systematic review

- Original Experimental

- Knowledge, attitudes, and practices of transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation in perioperative care: A Swedish web-based survey

- Impact of respiration on abdominal pain thresholds in healthy subjects – A pilot study

- Measuring pain intensity in categories through a novel electronic device during experimental cold-induced pain

- Robustness of the cold pressor test: Study across geographic locations on pain perception and tolerance

- Experimental partial-night sleep restriction increases pain sensitivity, but does not alter inflammatory plasma biomarkers

- Is it personality or genes? – A secondary analysis on a randomized controlled trial investigating responsiveness to placebo analgesia

- Investigation of endocannabinoids in plasma and their correlation with physical fitness and resting state functional connectivity of the periaqueductal grey in women with fibromyalgia: An exploratory secondary study

- Educational Case Reports

- Stellate ganglion block in disparate treatment-resistant mental health disorders: A case series

- Regaining the intention to live after relief of intractable phantom limb pain: A case study

- Trigeminal neuralgia caused by dolichoectatic vertebral artery: Reports of two cases

- Short Communications

- Neuroinflammation in chronic pain: Myth or reality?

- The use of registry data to assess clinical hunches: An example from the Swedish quality registry for pain rehabilitation

- Letter to the Editor

- Letter to the Editor For: “Stellate ganglion block in disparate treatment-resistant mental health disorders: A case series”

- Corrigendum

- Corrigendum to “Patient characteristics in relation to opioid exposure in a chronic non-cancer pain population”