Well-being in pain questionnaire: A novel, reliable, and valid tool for assessment of the personal well-being in individuals with chronic low back pain

-

Jani Mikkonen

, Frank Martela

Abstract

Background

Well-being is closely related to health, recovery, and longevity. Chronic musculoskeletal pain (CMP) is a major health challenge in the general population, which can have a negative effect on subjective well-being. The ability to identify patients’ well-being protective factors, including psychological, social, and lifestyle components, can help guide the therapeutic process in the management of CMP. Recognizing the absence of a dedicated well-being questionnaire, tailored specifically for CMP populations, an 11-item well-being in pain questionnaire (WPQ) was developed.

Objectives

The objectives were to develop a valid and reliable patient-reported measure of personal pain-specific well-being protective factors and to evaluate its psychometric properties, including (i) internal consistency; (ii) known-group validity between subjects with chronic low back pain (CLBP) and healthy pain-free controls; (iii) convergent validity between the WPQ and measures of health-related quality of life, catastrophizing, sleep quality, symptoms of central sensitization, and anxiety; and (iv) structural validity with exploratory factor analysis.

Design

This is a cross-sectional validation study.

Methods

After reviewing previous CMP and well-being literature, the novel WPQ items were constructed by expert consensus and target population feedback. The psychometric properties of the WPQ were evaluated in a sample of 145 participants, including 92 subjects with CLBP and 53 pain-free controls.

Results

Feedback from a preliminary group of CMP patients about the relevance, content, and usability of the test items was positive. Internal consistency showed acceptable results (α = 0.89). The assessment of convergent validity showed moderate correlations (≤0.4 or ≥−0.4.) with well-established subject-reported outcome measures. The assessment of structural validity yielded a one-factor solution, supporting the unidimensionality of the WPQ.

Conclusions

The psychometric results provided evidence of acceptable reliability and validity of the WPQ. Further research is needed to determine the usability of the WPQ as an assessment and outcome tool in the comprehensive management of subjects with CMP.

1 Introduction

Subjective well-being means a subjective examination of one’s own life in terms of positive emotions, positive life evaluations, and a perception of functioning well in daily life [1,2,3]. Subjective well-being is closely related to objective measures of better health, recovery, and longevity in both healthy and clinical populations [2,4,5,6]. Chronic musculoskeletal pain (CMP) is one of the major public health challenges affecting the daily life of approximately 10% of the general population [7,8]. Chronic low back pain (CLBP) is the most researched and prevalent CMP syndrome [7,9].

Patient-reported outcome measures (PROMs) are commonly used to assess individuals with CMP in clinical and research settings [10]. Most CMP-related PROMs focus solely on symptomatology and contributing factors related to physical functions, emotions, cognitions, social aspects of life, lifestyle, and pain modulation [11,12,13]. Though results vary among individuals, well-established reciprocal relationships have been found among the severity of contributing factors to CMP and levels of disability with activities of daily living, quality of rest, and physical and psychological functions [14,15,16,17]. Interventions targeting CPM-related factors are commonly recommended treatment options [18,19,20,21,22,23].

In contrast, protective factors like well-being have traditionally been studied less often in CMP populations, though interest in well-being, resilience, optimism, and other protective factors, has been increasing more recently [24,25,26]. Previous study results have shown that better subjective well-being can function as a projective factor in some patients with CMP, which can lower the patient-reported symptom severity, disability, and pain catastrophizing [25,27,28]. These studies have examined well-being domains with generic PROMs of well-being, which are not specific to CMP populations. A comprehensive review of well-being measures has shown that questionnaire items and definitions of well-being vary considerable [26].

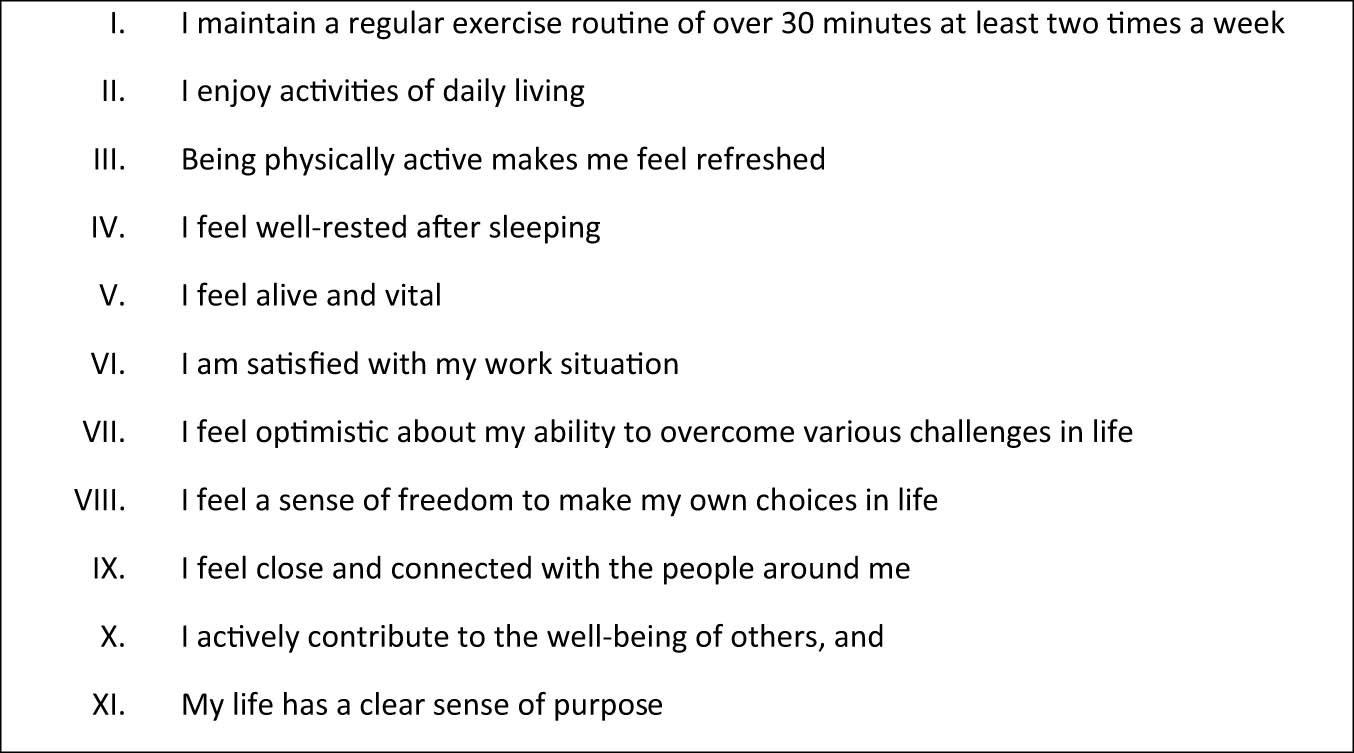

In this article, we report the stages of development and validity analysis of a novel PROM, the well-being in pain questionnaire (WPQ). Conceptually, we follow recent models of subjective well-being which argue that besides evaluative (e.g. life/job satisfaction) and emotional dimensions (e.g. vitality, joy), functional aspects of well-being should also be measured for a more comprehensive understanding [29,30,31]. As regards functional well-being, especially the role of psychological need satisfaction has been emphasized [32]. Besides, in the present context, we saw it as important to include measures of subjective experience of physical well-being to complement the more psychological dimensions of well-being. Accordingly, we wanted to build a measure of well-being that would include evaluative (life purpose and job satisfaction), emotional (vitality, enjoyment, and optimism), physical (refreshed, well-rested, and exercise), and functional dimensions of well-being (autonomy, relatedness, and contribution). The aim was not to cover all possible dimensions of well-being, as that would result in an unfeasibly long measure, but rather and in line with previous subjective well-being measures [31,33], to include some dimensions of each category and to provide a more comprehensive measure of subjective well-being.

The WPQ was designed to assess protective factors of well-being in subjects with CMP. Its aim was to assess pain-specific protective factors of personal well-being (e.g., positive psychological, social, and lifestyle aspects) to guide the therapeutic process in the management of CMP. We are unaware of any currently available validated PROMs that are specifically intended to measure the subjective well-being in subjects with CMP [25,27,28]. The objectives of the present study were to develop a valid and reliable patient-reported measure of personal pain-specific well-being protective factors and to evaluate its psychometric properties, including (i) internal consistency; (ii) known-group validity between subjects with CLBP and healthy pain-free controls; (iii) convergent validity between the WPQ and measures of health-related quality of life, catastrophizing, sleep quality, symptoms of central sensitization (CS), and anxiety; and (iv) structural validity with exploratory factor analysis (EFA).

2 Materials and methods

Ethical approval for the study was obtained from the Research Ethics Committee of the Northern Savo Hospital District with identification number 2131/2022 on 31st January 2022. This study was conducted following the Helsinki Declaration. In the development and validation of WPQ, we followed “Best Practices for Developing and Validating Scales for Health, Social, and Behavioural Research: A Primer” by Boateng et al. from 2018 when applicable [34] and COSMIN checklist recommendations [35] and their clarification [36].

2.1 Development of the WPQ

Because subjective well-being is determined from positive subjective and personal experiences [1,2,3], the WPQ items were constructed to emphasize positive aspects of life (i.e. protective factors) instead of negative contributing factors and consequences of CMP. That is why the word “pain” was not included in the wording of items and was only mentioned in the title and introduction sentence “Well-Being in Pain Questionnaire (WPQ) is to screen the effects of pain on a person’s well-being.”

The original Finnish version of the WPQ and its first translation into English were developed by the first authors JM and FM. Both are native Finnish speakers. English is their other professional working language. Generation of the WPQ items was based on the combination of deductive and inductive methods as recommended in the study of Boateng et al. [34]. Deductive methods were based on an extensive literature review, academic background, clinical expertise, and feedback from field experts. Inductive methods included qualitative and cognitive pretesting of the WPQ items in a target population of CPM patients.

The author JM developed items 1–6 (items related to activities and rest), which were constructed based on the knowledge of profound importance of regular physical activity, subjective feelings of contentment, perception of general quality in life, and the quality of rest in subjects with CMP [7,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22]. The author FM developed items 7–11, which were related to key elements of positive psychological functioning of feelings of optimism, freedom, closeness, contribution, and purpose [32,37,38]. Self-assessment over the last month was chosen because it was not considered to be too long and difficult to recall. JM is a long-term clinician and researcher of CMP and FM is a researcher of psychology, specializing in subjective well-being.

After the first Finnish version was drafted, a licenced professional translator and native English-speaker, specializing in healthcare texts, translated it into English. The translator also corrected the grammar and suggested some minor changes in the content of some items to increase readability. Then, the authors RN and LG evaluated the English version and provided feedback, which prompted some minor adjustments in some of the items. At that point, a provisional version of the WPQ was established.

Qualitative and cognitive pretesting and assessment of face validity of the provisional WPQ was performed with 30 CMP patients (specifically, CLBP) in the first author’s private clinic. These patients were informed about the details of the validation study and were asked to provide informed consent. They completed the WPQ at home and then gave verbal feedback about each WPQ item during the next clinic visit. The patients reported that the WPQ was easy to complete, the items were easy to understand, and the time frame (during the last month) was convenient to recall. After receiving this positive feedback about the appropriateness, content, and usability of the WPQ, it was agreed that the provisional version was the final version. The final version of the WPQ items is shown in Figure 1.

WPQ items. Each item is rated with a 5-point scale: “almost always” = 4, “often” = 3, “sometimes” = 2, “rarely” = 1, and “never” = 0.

2.2 Data collection

Data collection was carried out in two stages described in detail below. COSMIN checklist recommendations were used to make decisions about the number of participants needed for adequate statistical analyses, including internal consistency, known-group validity between subjects with CLBP and healthy pain-free controls, convergent validity, and structural validity [35]. Specific validity hypotheses were tested. First, we hypothesized that the total mean scores between the CLBP patients and healthy control subjects would be statistically different at a less than 0.05 significance level. Second, we hypothesized that convergent validity correlations between the WPQ and other CMP-related PROMs would be “≤0.4 or ≥−0.4.”

Subjects were recruited directly by the authors, other healthcare colleagues, and through study advertisements at Finnish spine and pain-related organizations. The study advertisements included information about the nature of the study, inclusion and exclusion criteria, and further instructions about how to complete all intake information and study PROMs at home.

The first stage of data collection included subjects with CLBP, which were collected through another registered clinical study (ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT05268822) [39] between 16th February 2022 and 20th October 2022. The recommended duration and frequency of CLBP were used to define CLBP in the present study [40]. CLBP was defined as “Low back pain present for more than three months and occurring more than three days per week” [41]. Written informed consent was obtained from all subjects with CLBP before the study.

The second stage of data collection included healthy control subjects, which were defined as “healthy subjects who did not report any persistent pain problems within the last month or pain at the moment of completing the questionnaires.” Subjects were recruited directly by the authors and other healthcare colleagues. Data collection was carried out between 14th January and 30th April 2023. The pain-free participants were informed about the study in a similar manner than the CLBP group, but additional information was provided about why written informed consent was not needed because according to the written decision of the University of Eastern Finland Research Ethics Committee, based on the Finnish National Board on Research Integrity guidelines.

Subjects were eligible for the study if they met the following inclusion criteria and not the exclusion criteria.

Inclusion criteria are as follows:

Males and females aged 18–68 years.

Subjects with low back pain lasting more than 3 days per week during the last 3 months or healthy subjects who reported no persistent pain problems within the last month nor having pain at when completing the questionnaires.

Proficient in written and spoken Finnish language.

Written informed consent was provided (subjects with CLBP only).

Completed pain history, demographics, and all PROMs.

Exclusion criteria are as follows:

History of malignancy.

Previous diagnosis of a neurological disease affecting the central nervous system (e.g., dementia, MS, etc.).

Previous diagnosis of a rheumatic disease (e.g., fibromyalgia, ankylosing spondylitis/rheumatoid arthritis, etc.).

Spinal surgery within 1 year of the study.

After the self-eligibility assessment of inclusion and exclusion criteria, the study participants completed study questionnaires on the webpages of Nordhealth Connect (https://connect.nordhealth.com/), which is a Finnish company providing an electronic platform with strong electronic authentication for data collection and storage of study questionnaires for participants. In Finland, strong electronic identification enables participants to verify their identity safely in various electronic services before completing PROM, demographic, and pain questions.

2.3 Demographic data and pain history

Each subject completed a structured set of web-based dichotomous (yes/no) questions about pain history. All subjects were asked demographic questions of age in years, height in centimetres, weight in kilograms, and educational level (1. Elementary school, 2. High school or vocational school, 3. Lower university degree, 4. Higher university). In the analysis phase, body mass index (BMI) was calculated using subject-reported data.

2.4 PROMs

The WPQ was designed to assess psychological, social, and lifestyle aspects of personal well-being over the last month. The WPQ utilized a 5-point Likert scale, including “almost always” = 4, “often” = 3, “sometimes” = 2, “rarely” = 1, and “never” = 0. A total score is determined by adding the results of each of the 11 items. Total scores ranged from 44 (the maximum well-being in pain) to 0 (the minimal well-being in pain). Note that the English version of the WPQ is not currently cross-culturally validated, and hence the English translation is not intended for use in clinical or research work without prior acceptable validation. The English and Finnish original full versions of the WPQ are included as supplementary materials 1 and 2, respectively.

The first part of the EuroQol (EQ-5D-5L) was used to assess five dimensions of health-related quality of life [42] – mobility, self-care, usual activities, pain/discomfort, and anxiety/depression – on a Likert scale (0 = no problems, 1 = slight problems, 2 = moderate problems, 3 = severe problems, and 4 = unable/extreme problems). The second part of the EQ-5D-5L enquired about self-rated health on a visual analogue scale between 100 “the best health you can imagine” and 0 “the worst health you can imagine” [42]. As a standard value set is not available in a Finnish population, a value set from a Danish population was used to calculate the index value, which is recommended by the EuroQol EQ-5D-5L User Guide [43]. EQ-5D-5L is one of the most commonly used PROMs of health-related quality of life in CMP populations [11].

The pain catastrophizing scale (PCS) is widely used and has been validated in different CMP populations [44]. It assesses the tendency to magnify the threat value of pain stimuli. Thirteen items are scored on a Likert scale from 0 to 4, producing total scores from 0 (no catastrophizing thoughts) to 52 (maximum catastrophizing thoughts) [45]. The PCS has been previously translated and validated in a Finnish CLBP population [46].

The Pain and Sleep Questionnaire Three-Item Index (PSQ-3) is a three-question questionnaire to evaluate the effects of pain on sleep. The three items are as follows: “1. How often have you had trouble falling asleep because of pain? 2. How often have you been awakened by pain during the night? 3. How often have you been awakened by pain in the morning?” The scale ranged from 0 (pain does not affect sleep) to 30 (pain has the maximum negative effect on sleep) [47]. The PSQ-3 has been translated into Finnish and validated in a Finnish CLBP population [48].

The CS inventory (CSI) assesses symptoms related to CS [49]. It is a two-part questionnaire in which part A contains 25 questions on CS-related symptomology using a Likert scale from 0 = never to 4 = always. The total score ranges from 0 to 100. Part B includes “No/Yes” and “year diagnosed” questions about previous diagnoses related to CS-related disorders. Part B of the CSI is to provide information only and is not scored [50]. Part B was not used in the present study. The CSI has been translated into Finnish and validated in a Finnish CLBP population [51].

The Generalized Anxiety Disorder Assessment (GAD-7) is a self-reported measure of symptoms related to generalized anxiety disorder. The items are rated over the preceding 2 weeks from not at all = 0 to nearly every day = 3. The total scale ranges from 0 (minimal anxiety) to 21 (the most severe anxiety) [52]. The GAD-7 has been adapted and validated in Finnish [53].

2.5 Statistical methods

Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS version 25 (IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 26.0. Armonk, NY: IBM Corp.). Statistical significance was defined as p < 0.05. Data were reported as n (%) or mean values with standard deviations (mean ± SD). Skewed distributed data were tested by the Mann–Whitney U-test. Categorical variables were compared by the likelihood ratio.

Convergent validity between the WPQ and other PROMs was calculated with Pearson’s correlation coefficient (r). The strengths of the correlations were interpreted as weak (<0.3), weak to moderate (>0.2 or <0.4), moderate (>0.3 or <0.7), moderate to high (>0.6 or <0.8), or high correlation (>0.7) [54]. Cronbach’s alpha was used to assess the internal consistency. An alpha value between 0.70 and 0.90 was considered acceptable [55]. A Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin (KMO) measure and Bartlett’s test of sphericity were used to test for appropriateness of the factor analysis. Unrotated EFA with maximum likelihood was used to identify the number of factors. EFA was recommended when there is no previous studies of the underlying factor structure of their measure [56]. The item loading cut-off value was set at ≥0.40, which is considered a “stable” value in the literature [57]. If the loading value was less than 0.40, the item was considered as “unstable” and hence is not a contributing factor [58].

3 Results

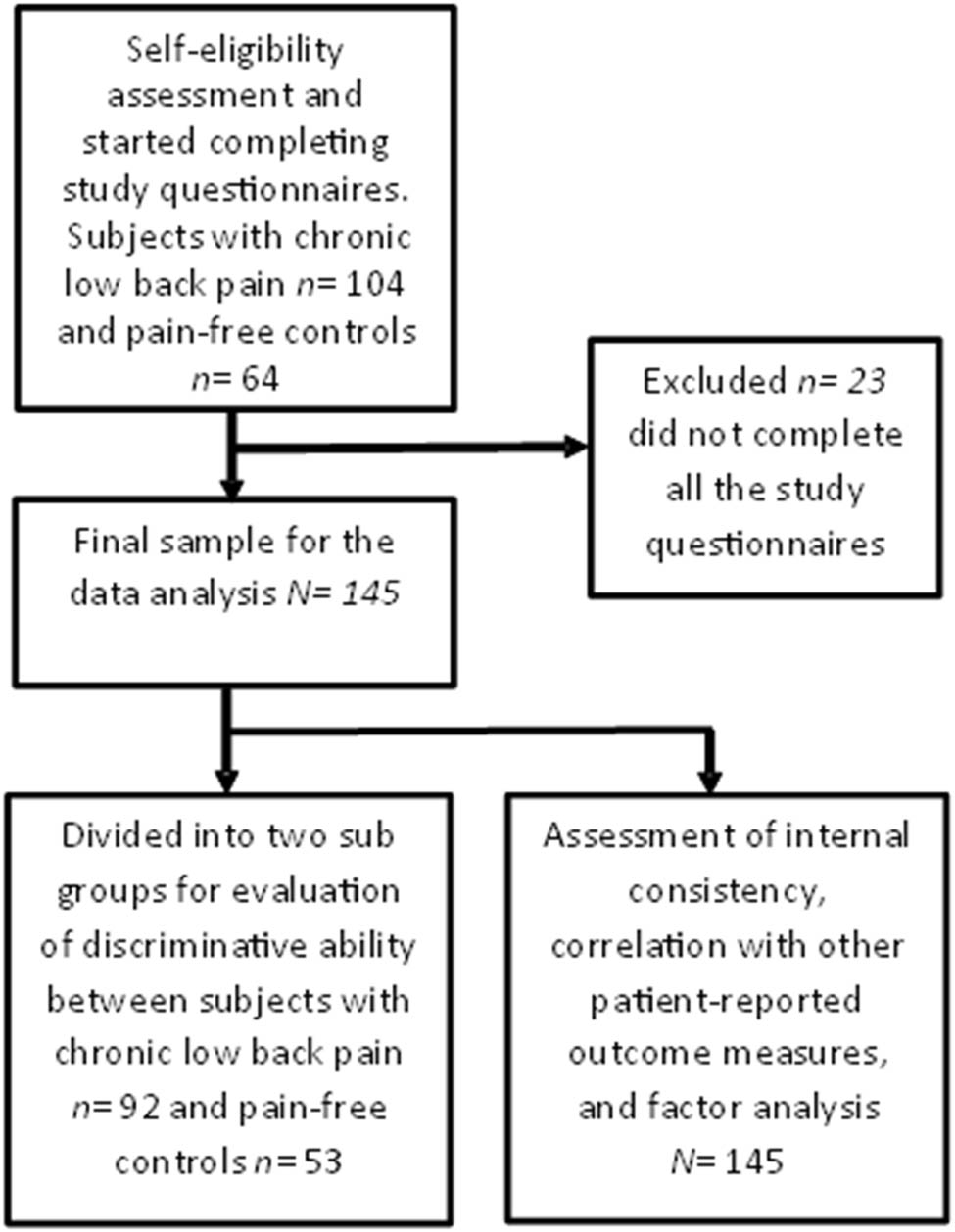

A total of 168 participants met self-assessed inclusion and exclusion criteria and agreed to participate. Twelve subjects in the CLBP group and 11 subjects in the pain-free control group did not complete all study questionnaires and hence were excluded. A total of 145 participants were included in the final analyses (Figure 2).

Flow chart.

Table 1 presents demographic information about the participants. Two statistically significant differences were found in the demographics between the two subject groups. The CLBP subjects were approximately 7 years older, and the pain-free controls were better educated, as more of those subjects had higher university degrees.

Demographics and patient-reported outcome score comparisons

| Subjects with CLBP (n = 92) mean (SD) | Pain-free controls (n = 53) mean (SD) | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age in years | 49.3 ± 12.2 | 42.1 ± 8.8 | <0.01 |

| Gender Female N (%) | 69 (75%) | 40 (75%) | 0.95 |

| Height in cm | 169.7 ± 8.5 | 170.1 ± 8.7 | 0.71 |

| Weight in kg | 77.0 ± 14.4 | 73.9 ± 8.7 | 0.35 |

| BMI | 26.7 ± 5.2 | 25.3 ± 4.8 | 0.42 |

| Educational level | 3.0 ± 0.9 | 3.4 ± 0.7 | 0.02 |

| WPQ | 34.0 ± 7.7 | 40.4.0 ± 3.5 | <0.01 |

| EuroQol 5-level EQ-5D version | 0.71 ± 0.11 | 0.94 ± 0.09 | <0.01 |

| EQ-5D-5L visual analogue scale | 65.5 ± 19.7 | 89.4 ± 8.4 | <0.01 |

| PCS | 15.3 ± 8.8 | 7.1 ± 4.9 | <0.01 |

| Pain and sleep questionnaire three-item index | 10.4 ± 8.8 | 0.8 ± 1.5 | <0.01 |

| CSI | 39.9 ± 13.5 | 24.6 ± 9.2 | <0.01 |

| Generalized anxiety disorder assessment | 4.1 ± 4.0 | 2.5 ± 2.8 | 0.01 |

The results are presented as mean ± SD or n (%). Educational level categories: 1. Elementary school. 2. High school or vocational school. 3. Lower university degree. 4. Higher university degree.

3.1 Known-group validity

As shown in Table 1, all study questionnaire mean scores, including the WPQ, were significantly better (indicating less symptom severity) in the pain-free control compared to the CLBP subjects. As shown in Table 2, the inter-group comparison showed significant group differences in all WPQ items, except items 8 and 9. It was noted that no pain-free control subject provided an answer of “never” for any of the items. All items reflected increased well-being scores in the pain-free control group.

WPQ group comparison of individual items (n = 145)

| Number | Item | Min–max scores in subjects with CLBP (n = 92) | Mean scores (SD) in subjects with CLBP (n = 92) | Min–max scores in pain-free controls (n = 53) | Mean scores (SD) in pain-free controls (n = 53) | Comparison between groups p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | I maintain a regular exercise routine of over 30 min at least two times a week | 0–4 | 2.9 ± 1.1 | 1–4 | 3.4 ± 0.9 | 0.04* |

| 2 | I enjoy activities of daily living | 1–4 | 2.9 ± 0.9 | 2–4 | 3.5 ± 0.6 | 0.01* |

| 3 | Being physically active makes me feel refreshed | 1–4 | 3.1 ± 0.9 | 3–4 | 3.9 ± 0.4 | <0.01* |

| 4 | I feel well-rested after sleeping | 0–4 | 2.3 ± 1.1 | 1–4 | 3.0 ± 0.8 | <0.01* |

| 5 | I feel alive and vital | 0–4 | 2.6 ± 1.1 | 1–4 | 3.3 ± 0.7 | <0.01* |

| 6 | I am satisfied with my work situation | 0–4 | 2.6 ± 1.2 | 1–4 | 3.3 ± 0.7 | <0.01* |

| 7 | I feel optimistic about my ability to overcome various challenges in life | 1–4 | 3.0 ± 0.9 | 2–4 | 3.6 ± 0.5 | <0.01* |

| 8 | I feel a sense of freedom to make my own choices in life | 1–4 | 3.2 ± 0.8 | 2–4 | 3.5 ± 0.6 | 0.07 |

| 9 | I feel close and connected with the people around me | 0–4 | 3.2 ± 0.8 | 1–4 | 3.4 ± 0.6 | 0.08 |

| 10 | I actively contribute to the well-being of others | 1–4 | 3.0 ± 0.8 | 2–4 | 3.3 ± 0.6 | 0.04* |

| 11 | My life has a clear sense of purpose | 0–4 | 3.0 ± 1.0 | 2–4 | 3.4 ± 0.7 | 0.04* |

The 5-point scale is scored as “almost always” = 4, “often” = 3, “sometimes” = 2, “rarely” = 1, and “never” = 0. The results are presented as mean ± SD. Likelihood ratio statistical significance p < 0.05*.

3.2 Internal consistency

Cronbach’s alpha showed acceptable results for the entire study group (α = 0.89) and separately for subjects with CLBP (α = 0.89) and pain-free controls (α = 0.75).

3.3 Convergent validity

As shown in Table 3, the WPQ demonstrated moderate correlations with PROMs of health-related quality of life, pain catastrophizing, sleep quality, CS symptoms, and generalized anxiety. Comparing the widely used health-related quality measure (EQ-5D-5L), correlations were stronger in the WPQ in 4 out of 5 comparisons including the EQ-5D-5L visual analogue scale.

Correlations between The Wellbeing in Pain Questionnaire, EuroQol 5-level EQ-5D version, and other patient-reported measures in participants with subjects with CLBP (n = 92)

| Patient-reported measures | Correlation with WPQ | Correlation with EuroQol 5-level EQ-5D version |

|---|---|---|

| WPQ | 1* | 0.45* |

| EuroQol 5-level EQ-5D version | 0.45* | 1* |

| EQ-5D-5L visual analogue scale | 0.60* | 0.56* |

| PCS | −0.45* | −0.41* |

| Pain and Sleep Questionnaire Three-Item Index | −0.41* | −0.45* |

| CSI | −0.55* | −0.47* |

| Generalized Anxiety Disorder Assessment | −0.46* | −0.36* |

Pearson’s correlation coefficient. Correlation two tailed-statistical significance p < 0.01*.

3.4 Factor analyses

EFA was performed to determine the factor structure of the WPQ. The KMO and Bartlett’s test of sphericity results revealed that the sample size was sufficient (KMO = 0.88), and the items were appropriate (Bartlett’s test of sphericity: χ 2 = 779.5, p < 0.01) for the factor analysis. Also, recommendations for suitability for the factor analysis of at least five subjects per item were met [59] as a total of 145 subjects and 11 items added up to 13.2 subjects per item.

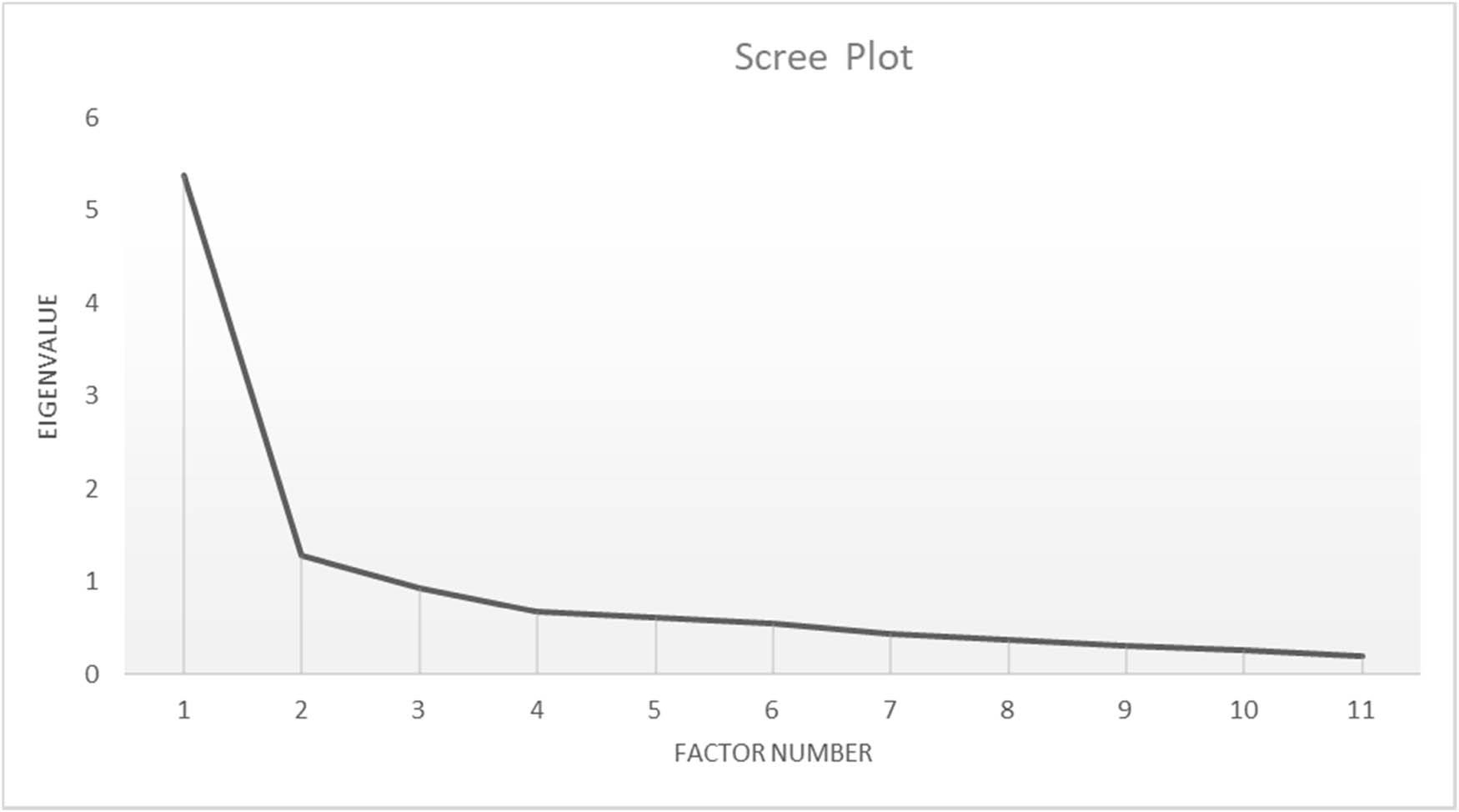

The EFA indicated that factor 1 explained 48.9% (eigenvalue: 5.381) and factor 2 explained 11.69% (eigenvalue: 1.285) of the total variance of the WPQ. Hence, the eigenvalue ratio of factor 1 and factor 2 were 4.19, which met the ≥4 requirement for a one-factor model [60]. As shown in Figure 3, the eigenvalue ratio was visualized on a scree plot.

Scree plot.

As shown in Table 4, EFA factor loadings for a 1- and 2-factor analyses (items required factor loading ≥0.40) showed an acceptable fit for the one-factor solution. On the tested 2-factor model, none of the item loadings met the requirement of factor loading of 0.4 or more.

Factor loadings for EFA (n = 145)

| Number | Item | EFA for factor one | EFA for factor two |

|---|---|---|---|

| Factor loadings | |||

| 1 | I maintain a regular exercise routine of over 30 min at least two times a week | 0.44 | 0.27 |

| 2 | I enjoy activities of daily living | 0.78 | 0.21 |

| 3 | Being physically active makes me feel refreshed | 0.53 | 0.34 |

| 4 | I feel well-rested after sleeping | 0.66 | 0.21 |

| 5 | I feel alive and vital | 0.83 | 0.17 |

| 6 | I am satisfied with my work situation | 0.65 | −0.05 |

| 7 | I feel optimistic about my ability to overcome various challenges in life | 0.75 | 0.10 |

| 8 | I feel a sense of freedom to make my own choices in life | 0.68 | 0.01 |

| 9 | I feel close and connected with the people around me | 0.58 | −0.43 |

| 10 | I actively contribute to the well-being of others | 0.55 | −0.40 |

| 11 | My life has a clear sense of purpose | 0.80 | −0.31 |

EFA values in bold refer to the factor loading ≥0.40.

4 Discussion

Published evidence suggests that protective factors of well-being are intrinsically linked to positive biopsychosocial outcomes in patients with CMP, and poor pain-related well-being can negatively impact treatment responsiveness [13,61]. The items on the WPQ were developed within this model. It attempts to tie together protective factors of well-being in patients with CMP, including well-being in exercise and sleep, productive activity, and positive psychological, into a single PROM [13,27]. The WPQ is a unique PROM in CMP populations because its items focus solely on positive protective factors, in affirmative and empowering language, instead of negative contributory factors, symptoms, and severity levels.

The WPQ was developed with deductive and inductive methods as recommended in the study of Boateng et al. [34]. Previous CMP and well-being literature, expert consensus, and target population feedback were used to construct the items. Face validity was assessed with established qualitative and cognitive pretesting in a group of 30 CLBP patients, who reported that the items were easy to understand, easy to complete, and relevant to their pain condition. Reliability and validity analyses demonstrated acceptable psychometric properties. The assessment of internal consistency showed that the items were closely related. Total scores and nine out of eleven intra-item scores were significantly different between the CLBP and healthy control groups, providing evidence of known-group validity. Convergent validity assessment showed moderate correlations between the WPQ and well-established PROMs of health-related quality of life, pain catastrophizing, sleep quality, CS symptoms, and generalized anxiety.

Compared to the health-related quality of life measure EQ-5D-5L, the correlations showed a stronger relationship with the WPQ, particularly concerning the health-related quality of life visual analogue scale, pain catastrophizing, CS symptoms, and generalized anxiety. This preliminary finding is notable, as previous reviews of well-being measures have often considered health-related quality of life and well-being as nearly synonymous [26], but items of EQ-5D-5L focus on symptom-based contributing factors. The a priori validity hypotheses were met, including the known-group validity of the known-group score difference and the moderate convergent validity results with other CMP-related PROMS. The assessment of structural validity, with analyses of EFA, yielded a one-factor (unidimensional) solution, suggesting that all items measured the same construct of subjective well-being.

Currently, very little is known about the role of protective factors of well-being in the management of CMP [25]. However, there has been a small but observable trend of an increased number of studies of CMP protective factors. Resilience is one of the most extensively researched protective factors in CMP populations. It refers to the ability to cope with and adapt to challenging life situations and circumstances. A pain-specific measure, the “Pain Resilience Scale,” has also been developed and validated [13,25,61,62]. A recent systematic review and meta-analysis determined that interventions based on subjective well-being domains (i.e. positive psychology interventions) are gaining popularity and have preliminary evidence of effectiveness in different CMP populations [59]. Use of the WPQ and other protective factor measures could foster new, more personalized models and interventions to better manage CMP. Improved assessment of protective factors of well-being could help guide CMP treatment.

More studies are needed to study the role of the subjective well-being in the complex multifactorial transition from short- to long-term CMP and its usability in alleviating individual suffering and societal burdens. Future studies should determine if low levels of protective well-being (e.g., low WPQ scores) in the acute stage of pain predicts a transition into CMP. It is very evident that novel and more comprehensive approaches for better management of CMP are needed [15,18,22,23,63,64].

5 Limitations

As with all studies of this kind, which assessed a relatively small group of CLBP subjects, generalization of results to larger CLBP and other CMP populations should be made with caution. Test–retest reliability should be investigated in future studies of the WPQ to ensure its consistency over time, standard error of measurement, and the smallest detectable change. Criterion validity between the WPQ and other non-pain specific measures of well-being should be studied in other chronic pain populations. Treatment responsiveness of the WPQ should also be evaluated. Another potential limitation is the challenge of capturing all essential items within an 11-item questionnaire, as both well-being and CMP encompass numerous protective and contributing factors. Only future studies utilizing the WPQ can determine the success of the item development and selection process.

6 Conclusions

Reliability and validity study objectives of the novel WPQ showed promising results, including acceptable internal consistency and known-group validity scores between CLBP subjects and healthy pain-free controls. Convergent validity showed moderate to good correlations with well-established PROMs of health-related quality of life, pain catastrophizing, sleep quality, CS symptoms, and generalized anxiety. The assessment of WPQ structure validity yielded a one-factor solution. The WPQ may be a useful tool for assessing protective factors of well-being in Finish-speaking subjects with CMP.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank all study subjects for their time and effort. Also, the authors want to thank Kirsi Töyrylä and Milla Suomi from Selkäliitto Ry and Kipumatkalla chronic pain peer support group moderators Sirpa Tahko, Päivi Vaarakallio, and Tuomo Ahola for help with data collection.

-

Research ethics: Research involving human subjects complied with all relevant national regulations and institutional policies and is in accordance with the tenets of the Helsinki Declaration (as amended in 2013). Ethical approval for this study was obtained from the Research Ethics Committee of the Northern Savo Hospital District, identification number 2131/2022, on 31st January 2022.

-

Informed consent: Informed consent was obtained from all individuals included in this study.

-

Author contributions: The author(s) have accepted responsibility for the entire content of this manuscript and approved its submission. JM: conceptualization, data curation, formal analysis, investigation, methodology, project administration, resources, software, validation, visualization, contributions/writing – original draft, and writing – review and editing. FM: conceptualization, methodology, resources, software, validation, contributions/writing – original draft, and writing – review & editing. RH: conceptualization, formal analysis, methodology, resources, validation, and contributions/writing – review and editing. KE: conceptualization, formal analysis, methodology, resources, validation, and contributions/writing – review and editing. LG: conceptualization, formal analysis, methodology, and contributions/writing – review and editing. VL: formal analysis, investigation, methodology, supervision, validation, and contributions/writing – review and editing. TS: methodology, resources, validation, and contributions/writing – review and editing. OA: conceptualization, formal analysis, methodology, contributions/writing – original draft, and writing – review and editing. RN: conceptualization, investigation, methodology, validation, contributions/writing – original draft, and writing – review and editing.

-

Competing interests: The authors state no conflict of interest.

-

Research funding: The authors state no funding was involved.

-

Data availability: The raw data can be obtained on request from the corresponding author.

-

Artificial intelligence/machine learning tool: Not applicable.

-

Supplementary material: The English and Finnish original versions of the WPQ are included as supplementary materials 1 and 2, respectively.

References

[1] Ruggeri K, Garcia-Garzon E, Maguire Á, Matz S, Huppert FA. Well-being is more than happiness and life satisfaction: a multidimensional analysis of 21 countries. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2020;18(1):192.10.1186/s12955-020-01423-ySuche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[2] Steptoe A, Deaton A, Stone AA. Subjective wellbeing, health, and ageing. Lancet. 2015;385(9968):640–8.10.1016/S0140-6736(13)61489-0Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[3] Gallagher MW, Lopez SJ, Preacher KJ. The hierarchical structure of well-being. J Pers. 2009;77(4):1025–50.10.1111/j.1467-6494.2009.00573.xSuche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[4] Birket-Smith M, Hansen BH, Hanash JA, Hansen JF, Rasmussen A. Mental disorders and general well-being in cardiology outpatients--6-year survival. J Psychosom Res. 2009;67(1):5–10.10.1016/j.jpsychores.2009.01.003Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[5] Moskowitz JT, Epel ES, Acree M. Positive affect uniquely predicts lower risk of mortality in people with diabetes. Health Psychol. 2008;27(1s):S73–82.10.1037/0278-6133.27.1.S73Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[6] Lamers SM, Bolier L, Westerhof GJ, Smit F, Bohlmeijer ET. The impact of emotional well-being on long-term recovery and survival in physical illness: a meta-analysis. J Behav Med. 2012;35(5):538–47.10.1007/s10865-011-9379-8Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[7] Hartvigsen J, Hancock MJ, Kongsted A, Louw Q, Ferreira ML, Genevay S, et al. What low back pain is and why we need to pay attention. Lancet. 2018;391(10137):2356–67.10.1016/S0140-6736(18)30480-XSuche in Google Scholar PubMed

[8] Cimmino MA, Ferrone C, Cutolo M. Epidemiology of chronic musculoskeletal pain. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol. 2011;25(2):173–83.10.1016/j.berh.2010.01.012Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[9] Maher C, Underwood M, Buchbinder R. Non-specific low back pain. Lancet. 2017;389(10070):736–47.10.1016/S0140-6736(16)30970-9Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[10] Pogatzki-Zahn E, Schnabel K, Kaiser U. Patient-reported outcome measures for acute and chronic pain: current knowledge and future directions. Curr Opin Anaesthesiol. 2019;32(5):616–22.10.1097/ACO.0000000000000780Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[11] Chiarotto A, Boers M, Deyo RA, Buchbinder R, Corbin TP, Costa L, et al. Core outcome measurement instruments for clinical trials in nonspecific low back pain. Pain. 2018;159(3):481–95.10.1097/j.pain.0000000000001117Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[12] Ramasamy A, Martin ML, Blum SI, Liedgens H, Argoff C, Freynhagen R, et al. Assessment of patient-reported outcome instruments to assess chronic low back pain. pain med. Pain Med (Malden, Mass). 2017;18(6):1098–110.10.1093/pm/pnw357Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[13] Goubert L, Trompetter H. Towards a science and practice of resilience in the face of pain. Eur J Pain. 2017;21(8):1301–15.10.1002/ejp.1062Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[14] Finan PH, Goodin BR, Smith MT. The association of sleep and pain: an update and a path forward. J Pain. 2013;14(12):1539–52.10.1016/j.jpain.2013.08.007Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[15] Buchbinder R, Underwood M, Hartvigsen J, Maher CG. The Lancet Series call to action to reduce low value care for low back pain: an update. Pain. 2020;161(Suppl 1):S57–64.10.1097/j.pain.0000000000001869Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[16] Van Looveren E, Bilterys T, Munneke W, Cagnie B, Ickmans K, Mairesse O, et al. The association between sleep and chronic spinal pain: A systematic review from the last decade. J Clin Med. 2021;10(17):3836.10.3390/jcm10173836Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[17] Kelly GA, Blake C, Power CK, O'keeffe D, Fullen BM. The association between chronic low back pain and sleep: a systematic review. Clin J Pain. 2011;27(2):169–81.10.1097/AJP.0b013e3181f3bdd5Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[18] Foster NE, Anema JR, Cherkin D, Chou R, Cohen SP, Gross DP, et al. Prevention and treatment of low back pain: evidence, challenges, and promising directions. Lancet. 2018;391(10137):2368–83.10.1016/S0140-6736(18)30489-6Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[19] Booth J, Moseley GL, Schiltenwolf M, Cashin A, Davies M, Hübscher M. Exercise for chronic musculoskeletal pain: A biopsychosocial approach. Musculoskelet Care. 2017;15(4):413–21.10.1002/msc.1191Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[20] Nijs J, Mairesse O, Neu D, Leysen L, Danneels L, Cagnie B, et al. Sleep disturbances in chronic pain: neurobiology, assessment, and treatment in physical therapist practice. Phys Ther. 2018;98(5):325–35.10.1093/ptj/pzy020Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[21] Nijs J, Lluch Girbés E, Lundberg M, Malfliet A, Sterling M. Addressing sleep problems and cognitive dysfunctions in comprehensive rehabilitation for chronic musculoskeletal pain. Man Ther. 2015;20(1):e3–4.10.1016/j.math.2014.10.007Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[22] Qaseem A, Wilt TJ, McLean RM, Forciea MA, Clinical Guidelines Committee of the American College of P, Denberg TD, et al. Noninvasive treatments for acute, subacute, and chronic low back pain: a clinical practice guideline from the american college of physicians. Ann Intern Med. 2017;166(7):514–30.10.7326/M16-2367Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[23] Rasmussen-Barr E, Halvorsen M, Bohman T, Boström C, Dedering Å, Kuster RP, et al. Summarizing the effects of different exercise types in chronic neck pain - a systematic review and meta-analysis of systematic reviews. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2023;24(1):806.10.1186/s12891-023-06930-9Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[24] Holmes MM, Lewith G, Newell D, Field J, Bishop FL. The impact of patient-reported outcome measures in clinical practice for pain: a systematic review. Qual Life Res. 2017;26(2):245–57.10.1007/s11136-016-1449-5Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[25] Larsson B, Dragioti E, Gerdle B, Björk J. Positive psychological well-being predicts lower severe pain in the general population: a 2-year follow-up study of the SwePain cohort. Ann Gen Psychiatry. 2019;18:8.10.1186/s12991-019-0231-9Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[26] Cooke PJ, Melchert TP, Connor K. Measuring well-being: A review of instruments. Couns Psychol. 2016;44(5):730–57.10.1177/0011000016633507Suche in Google Scholar

[27] Furrer A, Michel G, Terrill AL, Jensen MP, Müller R. Modeling subjective well-being in individuals with chronic pain and a physical disability: the role of pain control and pain catastrophizing. Disabil Rehabil. 2019;41(5):498–507.10.1080/09638288.2017.1390614Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[28] Müller R, Gertz KJ, Molton IR, Terrill AL, Bombardier CH, Ehde DM, et al. Effects of a tailored positive psychology intervention on well-being and pain in individuals with chronic pain and a physical disability: A feasibility trial. Clin J Pain. 2016;32(1):32–44.10.1097/AJP.0000000000000225Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[29] Graham C, Laffan K, Pinto S. Well-being in metrics and policy. Science. 2018;362(6412):287–8.10.1126/science.aau5234Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[30] Martela F. Being as having, loving, and doing: a theory of human well-being. Pers Soc Psychol Rev. 2024;28(4):372–97.10.1177/10888683241263634Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[31] Tennant R, Hiller L, Fishwick R, Platt S, Joseph S, Weich S, et al. The Warwick-Edinburgh mental well-being scale (WEMWBS): development and UK validation. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2007;5:63.10.1186/1477-7525-5-63Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[32] Martela F, Sheldon KM. Clarifying the concept of well-being: psychological need satisfaction as the common core connecting eudaimonic and subjective well-being. Rev Gen Psychol. 2019;23(4):458–74.10.1177/1089268019880886Suche in Google Scholar

[33] Su R, Tay L, Diener E. The development and validation of the Comprehensive Inventory of Thriving (CIT) and the Brief Inventory of Thriving (BIT). Appl Psychol Health Well Being. 2014;6(3):251–79.10.1111/aphw.12027Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[34] Boateng GO, Neilands TB, Frongillo EA, Melgar-Quiñonez HR, Young SL. Best practices for developing and validating scales for health, social, and behavioral research: a primer. Front Public Health. 2018;6:149.10.3389/fpubh.2018.00149Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[35] Mokkink LB, Terwee CB, Patrick DL, Alonso J, Stratford PW, Knol DL, et al. The COSMIN checklist for assessing the methodological quality of studies on measurement properties of health status measurement instruments: an international Delphi study. Qual Life Res. 2010;19(4):539–49.10.1007/s11136-010-9606-8Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[36] Mokkink LB, Terwee CB, Knol DL, Stratford PW, Alonso J, Patrick DL, et al. The COSMIN checklist for evaluating the methodological quality of studies on measurement properties: a clarification of its content. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2010;10:22.10.1186/1471-2288-10-22Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[37] Ryff CD. Happiness is everything, or is it? Explorations on the meaning of psychological well-being. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1989;57:1069–81.10.1037//0022-3514.57.6.1069Suche in Google Scholar

[38] Marsh HW, Huppert FA, Donald JN, Horwood MS, Sahdra BK. The well-being profile (WB-Pro): Creating a theoretically based multidimensional measure of well-being to advance theory, research, policy, and practice. Psychol Assess. 2020;32(3):294–313.10.1037/pas0000787Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[39] Mikkonen J, Luomajoki H, Airaksinen O, Goubert L, Pratscher S, Leinonen V. Identical movement control exercises with and without synchronized breathing for chronic non-specific low back pain:A randomized pilot trial. J Back Musculoskelet Rehabil. 2024;37(6):1561–71.10.3233/BMR-230413Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[40] Deyo RA, Dworkin SF, Amtmann D, Andersson G, Borenstein D, Carragee E, et al. Report of the NIH task force on research standards for chronic low back pain. Int J Ther Massage Bodyw. 2015;8(3):16–33.10.1111/pme.12538Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[41] Hoy D, March L, Brooks P, Blyth F, Woolf A, Bain C, et al. The global burden of low back pain: estimates from the Global Burden of Disease 2010 study. Ann Rheum Dis. 2014;73(6):968–74.10.1136/annrheumdis-2013-204428Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[42] Janssen MF, Pickard AS, Golicki D, Gudex C, Niewada M, Scalone L, et al. Measurement properties of the EQ-5D-5L compared to the EQ-5D-3L across eight patient groups: a multi-country study. Qual Life Res. 2013;22(7):1717–27.10.1007/s11136-012-0322-4Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[43] van Hout B, Janssen MF, Feng YS, Kohlmann T, Busschbach J, Golicki D, et al. Interim scoring for the EQ-5D-5L: mapping the EQ-5D-5L to EQ-5D-3L value sets. Value Health. 2012;15(5):708–15.10.1016/j.jval.2012.02.008Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[44] Quartana PJ, Campbell CM, Edwards RR. Pain catastrophizing: a critical review. Expert Rev Neurother. 2009;9(5):745–58.10.1586/ern.09.34Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[45] Osman A, Barrios FX, Kopper BA, Hauptmann W, Jones J, O'Neill E. Factor structure, reliability, and validity of the pain catastrophizing scale. J Behav Med. 1997;20(6):589–605.10.1023/A:1025570508954Suche in Google Scholar

[46] Mikkonen J, Leinonen V, Lähdeoja T, Holopainen R, Ekström K, Koho P, et al. Dimensionality, reliability, and validity of the Finnish version of the pain catastrophizing scale in chronic low back pain. Scand J Pain. 2024;24(1):0034.10.1515/sjpain-2024-0034Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[47] Ayearst L, Harsanyi Z, Michalko KJ. The pain and sleep questionnaire three-item index (PSQ-3): a reliable and valid measure of the impact of pain on sleep in chronic nonmalignant pain of various etiologies. Pain Res Manag. 2012;17(4):281–90.10.1155/2012/635967Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[48] Mikkonen J, Leinonen V, Luomajoki H, Kaski D, Kupari S, Tarvainen M, et al. Cross-cultural adaptation, reliability, and psychophysical validation of the pain and sleep questionnaire three-item index in finnish. J Clin Med. 2021;10(21):4887.10.3390/jcm10214887Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[49] Mayer TG, Neblett R, Cohen H, Howard KJ, Choi YH, Williams MJ, et al. The development and psychometric validation of the central sensitization inventory. Pain Pract. 2012;12(4):276–85.10.1111/j.1533-2500.2011.00493.xSuche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[50] Neblett R. The central sensitization inventory: A user’s manual. J Appl Behav Res. 2018;23:e12123.10.1111/jabr.12123Suche in Google Scholar

[51] Mikkonen J, Luomajoki H, Airaksinen O, Neblett R, Selander T, Leinonen V. Cross-cultural adaptation and validation of the Finnish version of the central sensitization inventory and its relationship with dizziness and postural control. BMC Neurol. 2021;21(1):141.10.1186/s12883-021-02151-6Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[52] Spitzer RL, Kroenke K, Williams JB, Löwe B. A brief measure for assessing generalized anxiety disorder: the GAD-7. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166(10):1092–7.10.1001/archinte.166.10.1092Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[53] Kujanpää T, Ylisaukko-Oja T, Jokelainen J, Hirsikangas S, Kanste O, Kyngäs H, et al. Prevalence of anxiety disorders among Finnish primary care high utilizers and validation of Finnish translation of GAD-7 and GAD-2 screening tools. Scand J Prim Health Care. 2014;32(2):78–83.10.3109/02813432.2014.920597Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[54] Abma IL, Rovers M, van der Wees PJ. Appraising convergent validity of patient-reported outcome measures in systematic reviews: constructing hypotheses and interpreting outcomes. BMC Res Notes. 2016;9:226.10.1186/s13104-016-2034-2Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[55] Tavakol M, Dennick R. Making sense of Cronbach’s alpha. Int J Med Educ. 2011;2:53–5.10.5116/ijme.4dfb.8dfdSuche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[56] Tavakol M, Wetzel A. Factor Analysis: a means for theory and instrument development in support of construct validity. Int J Med Educ. 2020;11:245–7.10.5116/ijme.5f96.0f4aSuche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[57] Guadagnoli E, Velicer WF. Relation of sample size to the stability of component patterns. Psychol Bull. 1988;103(2):265–75.10.1037//0033-2909.103.2.265Suche in Google Scholar

[58] Field A. Discovering statistics using IBM SPSS statistics. Zittau, DE: Sage Publications Ltd; 2013.Suche in Google Scholar

[59] Costello AB, Osborne J. Best practices in exploratory factor analysis: four recommendations for getting the most from your analysis. Pract Assess Res Eval. 2005;10:1–9.Suche in Google Scholar

[60] Reeve BB, Hays RD, Bjorner JB, Cook KF, Crane PK, Teresi JA, et al. Psychometric evaluation and calibration of health-related quality of life item banks: plans for the Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS). Med Care. 2007;45(5 Suppl 1):S22–31.10.1097/01.mlr.0000250483.85507.04Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[61] Sturgeon JA, Zautra AJ. Resilience: a new paradigm for adaptation to chronic pain. Curr Pain Headache Rep. 2010;14(2):105–12.10.1007/s11916-010-0095-9Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[62] Ankawi B, Slepian PM, Himawan LK, France CR. Validation of the pain resilience scale in a chronic pain sample. J Pain. 2017;18(8):984–93.10.1016/j.jpain.2017.03.013Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[63] Buchbinder R, van Tulder M, Öberg B, Costa LM, Woolf A, Schoene M, et al. Low back pain: a call for action. Lancet. 2018;391(10137):2384–8.10.1016/S0140-6736(18)30488-4Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[64] Wu A, March L, Zheng X, Huang J, Wang X, Zhao J, et al. Global low back pain prevalence and years lived with disability from 1990 to 2017: estimates from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. Ann Transl Med. 2020;8(6):299.10.21037/atm.2020.02.175Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

© 2025 the author(s), published by De Gruyter

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Editorial Comment

- Abstracts presented at SASP 2025, Reykjavik, Iceland. From the Test Tube to the Clinic – Applying the Science

- Quantitative sensory testing – Quo Vadis?

- Stellate ganglion block for mental disorders – too good to be true?

- When pain meets hope: Case report of a suspended assisted suicide trajectory in phantom limb pain and its broader biopsychosocial implications

- Transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation – an important tool in person-centered multimodal analgesia

- Clinical Pain Researches

- Exploring the complexities of chronic pain: The ICEPAIN study on prevalence, lifestyle factors, and quality of life in a general population

- The effect of peer group management intervention on chronic pain intensity, number of areas of pain, and pain self-efficacy

- Effects of symbolic function on pain experience and vocational outcome in patients with chronic neck pain referred to the evaluation of surgical intervention: 6-year follow-up

- Experiences of cross-sectoral collaboration between social security service and healthcare service for patients with chronic pain – a qualitative study

- Completion of the PainData questionnaire – A qualitative study of patients’ experiences

- Pain trajectories and exercise-induced pain during 16 weeks of high-load or low-load shoulder exercise in patients with hypermobile shoulders: A secondary analysis of a randomized controlled trial

- Pain intensity in anatomical regions in relation to psychological factors in hypermobile Ehlers–Danlos syndrome

- Opioid use at admittance increases need for intrahospital specialized pain service: Evidence from a registry-based study in four Norwegian university hospitals

- Topically applied novel TRPV1 receptor antagonist, ACD440 Gel, reduces temperature-evoked pain in patients with peripheral neuropathic pain with sensory hypersensitivity, a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, crossover study

- Pain and health-related quality of life among women of childbearing age in Iceland: ICEPAIN, a nationwide survey

- A feasibility study of a co-developed, multidisciplinary, tailored intervention for chronic pain management in municipal healthcare services

- Healthcare utilization and resource distribution before and after interdisciplinary pain rehabilitation in primary care

- Measurement properties of the Swedish Brief Pain Coping Inventory-2 in patients seeking primary care physiotherapy for musculoskeletal pain

- Observational Studies

- Association between clinical laboratory indicators and WOMAC scores in Qatar Biobank participants: The impact of testosterone and fibrinogen on pain, stiffness, and functional limitation

- Well-being in pain questionnaire: A novel, reliable, and valid tool for assessment of the personal well-being in individuals with chronic low back pain

- Properties of pain catastrophizing scale amongst patients with carpal tunnel syndrome – Item response theory analysis

- Adding information on multisite and widespread pain to the STarT back screening tool when identifying low back pain patients at risk of worse prognosis

- The neuromodulation registry survey: A web-based survey to identify and describe characteristics of European medical patient registries for neuromodulation therapies in chronic pain treatment

- Topical Review

- An action plan: The Swedish healthcare pathway for adults with chronic pain

- Systematic Reviews

- Effectiveness of non-invasive vagus nerve stimulation vs heart rate variability biofeedback interventions for chronic pain conditions: A systematic review

- A scoping review of the effectiveness of underwater treadmill exercise in clinical trials of chronic pain

- Neural networks involved in painful diabetic neuropathy: A systematic review

- Original Experimental

- Knowledge, attitudes, and practices of transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation in perioperative care: A Swedish web-based survey

- Impact of respiration on abdominal pain thresholds in healthy subjects – A pilot study

- Measuring pain intensity in categories through a novel electronic device during experimental cold-induced pain

- Robustness of the cold pressor test: Study across geographic locations on pain perception and tolerance

- Experimental partial-night sleep restriction increases pain sensitivity, but does not alter inflammatory plasma biomarkers

- Educational Case Reports

- Stellate ganglion block in disparate treatment-resistant mental health disorders: A case series

- Regaining the intention to live after relief of intractable phantom limb pain: A case study

- Trigeminal neuralgia caused by dolichoectatic vertebral artery: Reports of two cases

- Short Communications

- Neuroinflammation in chronic pain: Myth or reality?

- The use of registry data to assess clinical hunches: An example from the Swedish quality registry for pain rehabilitation

- Letter to the Editor

- Letter to the Editor For: “Stellate ganglion block in disparate treatment-resistant mental health disorders: A case series”

- Corrigendum

- Corrigendum to “Patient characteristics in relation to opioid exposure in a chronic non-cancer pain population”

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Editorial Comment

- Abstracts presented at SASP 2025, Reykjavik, Iceland. From the Test Tube to the Clinic – Applying the Science

- Quantitative sensory testing – Quo Vadis?

- Stellate ganglion block for mental disorders – too good to be true?

- When pain meets hope: Case report of a suspended assisted suicide trajectory in phantom limb pain and its broader biopsychosocial implications

- Transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation – an important tool in person-centered multimodal analgesia

- Clinical Pain Researches

- Exploring the complexities of chronic pain: The ICEPAIN study on prevalence, lifestyle factors, and quality of life in a general population

- The effect of peer group management intervention on chronic pain intensity, number of areas of pain, and pain self-efficacy

- Effects of symbolic function on pain experience and vocational outcome in patients with chronic neck pain referred to the evaluation of surgical intervention: 6-year follow-up

- Experiences of cross-sectoral collaboration between social security service and healthcare service for patients with chronic pain – a qualitative study

- Completion of the PainData questionnaire – A qualitative study of patients’ experiences

- Pain trajectories and exercise-induced pain during 16 weeks of high-load or low-load shoulder exercise in patients with hypermobile shoulders: A secondary analysis of a randomized controlled trial

- Pain intensity in anatomical regions in relation to psychological factors in hypermobile Ehlers–Danlos syndrome

- Opioid use at admittance increases need for intrahospital specialized pain service: Evidence from a registry-based study in four Norwegian university hospitals

- Topically applied novel TRPV1 receptor antagonist, ACD440 Gel, reduces temperature-evoked pain in patients with peripheral neuropathic pain with sensory hypersensitivity, a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, crossover study

- Pain and health-related quality of life among women of childbearing age in Iceland: ICEPAIN, a nationwide survey

- A feasibility study of a co-developed, multidisciplinary, tailored intervention for chronic pain management in municipal healthcare services

- Healthcare utilization and resource distribution before and after interdisciplinary pain rehabilitation in primary care

- Measurement properties of the Swedish Brief Pain Coping Inventory-2 in patients seeking primary care physiotherapy for musculoskeletal pain

- Observational Studies

- Association between clinical laboratory indicators and WOMAC scores in Qatar Biobank participants: The impact of testosterone and fibrinogen on pain, stiffness, and functional limitation

- Well-being in pain questionnaire: A novel, reliable, and valid tool for assessment of the personal well-being in individuals with chronic low back pain

- Properties of pain catastrophizing scale amongst patients with carpal tunnel syndrome – Item response theory analysis

- Adding information on multisite and widespread pain to the STarT back screening tool when identifying low back pain patients at risk of worse prognosis

- The neuromodulation registry survey: A web-based survey to identify and describe characteristics of European medical patient registries for neuromodulation therapies in chronic pain treatment

- Topical Review

- An action plan: The Swedish healthcare pathway for adults with chronic pain

- Systematic Reviews

- Effectiveness of non-invasive vagus nerve stimulation vs heart rate variability biofeedback interventions for chronic pain conditions: A systematic review

- A scoping review of the effectiveness of underwater treadmill exercise in clinical trials of chronic pain

- Neural networks involved in painful diabetic neuropathy: A systematic review

- Original Experimental

- Knowledge, attitudes, and practices of transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation in perioperative care: A Swedish web-based survey

- Impact of respiration on abdominal pain thresholds in healthy subjects – A pilot study

- Measuring pain intensity in categories through a novel electronic device during experimental cold-induced pain

- Robustness of the cold pressor test: Study across geographic locations on pain perception and tolerance

- Experimental partial-night sleep restriction increases pain sensitivity, but does not alter inflammatory plasma biomarkers

- Educational Case Reports

- Stellate ganglion block in disparate treatment-resistant mental health disorders: A case series

- Regaining the intention to live after relief of intractable phantom limb pain: A case study

- Trigeminal neuralgia caused by dolichoectatic vertebral artery: Reports of two cases

- Short Communications

- Neuroinflammation in chronic pain: Myth or reality?

- The use of registry data to assess clinical hunches: An example from the Swedish quality registry for pain rehabilitation

- Letter to the Editor

- Letter to the Editor For: “Stellate ganglion block in disparate treatment-resistant mental health disorders: A case series”

- Corrigendum

- Corrigendum to “Patient characteristics in relation to opioid exposure in a chronic non-cancer pain population”