Participants with mild, moderate, or severe pain following total hip arthroplasty. A sub-study of the PANSAID trial on paracetamol and ibuprofen for postoperative pain treatment

-

Luma Mahmoud Issa

Abstract

Objectives

In this sub-study of the ‘Paracetamol and Ibuprofen in Combination’ (PANSAID) trial, in which participants were randomised to one of four different non-opioids analgesic regimen consisting of paracetamol, ibuprofen, or a combination of the two after planned primary total hip arthroplasty, our aims were to investigate the distribution of participants’ pain (mild, moderate or severe), integrate opioid use and pain to a single score (Silverman Integrated Approach (SIA)-score), and identify preoperative risk factors for severe pain.

Methods

We calculated the proportions of participants with mild (VAS 0–30 mm), moderate (VAS 31–60 mm) or severe (VAS 61–100 mm) pain and the SIA-scores (a sum of rank-based percentage differences from the mean rank in pain scores and opioid use, ranging from −200 to 200%). Using logistic regression with backwards elimination, we investigated the association between severe pain and easily obtainable preoperative patient characteristics.

Results

Among 556 participants from the modified intention-to-treat population, 33% (95% CI: 26–42) (Group Paracetamol + Ibuprofen (PCM + IBU)), 28% (95% CI: 21–37) (Group Paracetamol (PCM)), 23% (95% CI: 17–31) (Group Ibuprofen (IBU)), and 19% (95% CI: 13–27) (Group Half Strength-Paracetamol + Ibuprofen (HS-PCM + IBU)) experienced mild pain 6 h postoperatively during mobilisation. Median SIA-scores during mobilisation were: Group PCM + IBU: −48% (IQR: −112 to 31), Group PCM: 40% (IQR: −31 to 97), Group IBU: −5% (IQR: −57 to 67), and Group HS-PCM + IBU: 6% (IQR: −70 to 74) (overall difference: p=0.0001). Use of analgesics before surgery was the only covariate associated with severe pain (non-opioid: OR 0.50, 95% CI: 0.29–0.82, weak opioid 0.56, 95% CI: 0.28–1.16, reference no analgesics before surgery, p=0.02).

Conclusions

Only one third of participants using paracetamol and ibuprofen experienced mild pain after total hip arthroplasty and even fewer experienced mild pain using each drug alone as basic non-opioid analgesic treatment. We were not able, in any clinically relevant way, to predict severe postoperative pain. A more extensive postoperative pain regimen than paracetamol, ibuprofen and opioids may be needed for a large proportion of patients having total hip arthroplasty. SIA-scores integrate pain scores and opioid use for the individual patient and may add valuable information in acute pain research.

Introduction

Treatment of postoperative pain includes numerous analgesic drugs and techniques. Reports show most patients are not adequately treated [1] and few meet the goal of “no more than mild pain” as suggested by Moore [2]. Not all trials report the distribution of participants’ pain [3] and there may be differences in group-based means/medians of opioid use and the distribution of participants’ pain [4].

In acute pain trials participants are allowed to use escape/rescue opioids, but intervention efficacy is often analysed using either the participants pain scores or their need for supplementary opioids, thus ignoring the interdependency between the two. The Silverman Integrated Approach (SIA)-score [5], [6], [7] has been suggested as a composite score of pain and opioid use but is not yet widely accepted [8] and rarely reported.

Further, little is known about prediction of acute postoperative pain and not all patients are at risk of having severe pain. Being able to identify patients at risk and, thus, improving individualised treatment, is of high importance [9].

These gaps of knowledge are explored in the present sub-study [10] of the PANSAID trial [11], which was analysed [12] using differences in group-based means (medians) with opioid use as the co-primary outcome and pain scores as secondary outcomes. The aim was to reanalyse the data with regard to the distribution of participants’ pain (e.g. mild, moderate or severe pain) and risk factors for severe pain. We hypothesised that the distribution of participants’ pain (proportion of participants with “no more than mild pain” [VAS 0–30 mm]) and the integrated score of pain and supplementary opioid (SIA score of less than −100% [suggesting both lower than expected pain scores and opioid need]) would support the main results from the PANSAID trial of a better analgesic effect of the combination of paracetamol and ibuprofen. Regarding risk factors for severe pain, we hypothesised that easily measured preoperative participant characteristics could identify participants at risk for VAS 61–100 mm.

Methods

Trial overview and main results

PANSAID was a multi-centre, randomised, controlled, parallel, four-group clinical trial investigating the effects of different doses and combinations of paracetamol, ibuprofen and placebo in patients undergoing total hip arthroplasty (THA). The PANSAID trial was conducted at six Danish hospitals from December 2015 – January 2018. The protocol [13], the statistical analysis [12] and the main results [11] has been published previously. The trial protocol was approved by the Biomedical Research Ethics Committee of Region Zealand (SJ-462) and was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. PANSAID was monitored by Good Clinical Practice Units at Odense and Copenhagen University Hospitals, and the trial was registered at ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT02571361), EudraCT (2015-002239-16) and the Danish Data Protection Agency (REG-33-2015). All participants gave written informed consent prior to enrolment.

A total of 556 participants having primary planned THA where randomised into four intervention groups in a 1:1:1:1 ratio, stratified by site. The intervention groups were: group PCM + IBU (paracetamol 1000 mg + ibuprofen 400 mg), group PCM (paracetamol 1000 mg + matching placebo), group IBU (ibuprofen 400 mg + matching placebo), and group HS-PCM + IBU (paracetamol 500 mg + ibuprofen 200 mg).

The medication was taken orally 1 h before surgery and administered a total of four times (at 6-h intervals) during the first postoperative day. Throughout the trial, participants, caregivers, physicians, investigators, statisticians, and conclusion drawers were blinded to the intervention.

The primary analysis was based on the modified intention-to-treat (mITT) population — defined as participants who were randomised and underwent surgery. The two co-primary outcomes were 24-h morphine consumption using patient-controlled analgesia, and proportion of participants having one or more serious adverse events within 90 days following surgery (SAE were defined as any untoward medical occurrence that results in death; is life threatening; requires hospitalization; or results in significant or persistent disability or incapacity; birth defects; or a medical intervention to prevent one of the before-mentioned outcomes). The outcome of morphine consumption was in pairwise comparisons between the four groups (six comparisons) and the outcome of SAEs was a comparison between participants randomised to ibuprofen (groups PCM + IBU, IBU, and HS-PCM + IBU) and participants randomised to paracetamol (group PCM).

The main findings were that combining paracetamol 1 g and ibuprofen 400 mg resulted in reduced morphine consumption compared with each drug alone on the first postoperative day after total hip arthroplasty (16 mg, 99.6% CI: 6.5–24, p<0.001 compared with paracetamol, and 6 mg, 99.6% CI: −2 to 16, p=0.002 compared with ibuprofen). The reduction for the combination group vs. ibuprofen alone, was however, lower than the predefined minimum clinical important difference of 10 mg (10 mg was pragmatically chosen because it is commonly used in acute pain trials). The combination of lower dosages (group HS-PCM + IBU) resulted in reduced morphine consumption compared with paracetamol 1 g only, and comparable morphine consumption to ibuprofen 400 mg only. Regarding harm, the proportion of participants with one or more SAE was numerically higher in participants randomised to ibuprofen (15%) compared with participants randomised to paracetamol only (11%), although not statistically significant (relative risk 1.44, 97.5% CI: 0.79–2.64, p=0.18).

The present sub-study

The present sub-study was planned during recruitment of participants to the PANSAID trial and before any outcome data were explored. A protocol synopsis including choice of outcomes, statistical analysis plan, and covariates for the prediction model was made publicly available at the trial webpage (www.pansaid.dk) on 29 September 2017 [10], and was also outlined in the protocol and at clinicaltrials.gov (NCT02571361). During the re-analysis of the trial data for this article we further decided to include the composite outcome score (Silverman’s Integrated Approach (SIA)) of opioid use and pain scores and, therefore, all SIA-scores are regarded as post hoc. The sub-study included all participants in the mITT population. The primary outcome was proportion of participants experiencing mild pain 6 h postoperatively during mobilisation in the four randomisation groups. This manuscript adheres to the applicable CONSORT guideline.

Participants’ pain

All participants in the trial had their pain intensity measured on a Visual Analogue Scale (VAS; 0 mm, no pain and 100 mm, worst imaginable pain) 6 and 24 h postoperatively at rest and during 30° active hip flexion on the operated side. Mild pain was defined as VAS scores 0–30 mm, moderate pain as VAS scores 31–60 mm, and severe pain as VAS scores 61–100 mm.

Silverman and colleagues suggested integrating the Visual Analogue Scale score and rescue morphine to a composite score to circumvent statistical issues of mass significance [5]. To calculate the SIA score we calculated the mean VAS at rest and during mobilisation (Mean-VASrest, 0–24 h and Mean-VASmobilisation, 0–24 h, respectively). Mean-VASrest, 0–24 h, Mean-VASmobilisation, 0–24 h, and morphine requirement for each participant were ranked. A mean rank for all participants (across all randomisation groups) was calculated and the differences between the mean rank and the individual participant’s rank were expressed as percentages. The sum of the percentage (percentage-for-VASrest, 0–24 h + percentage-for-morphine requirement, and percentage-for-VASmobilisation, 0–24 h + percentage-for-morphine requirement) represent the SIA score at rest and during mobilisation, respectively. Hence, the range of the SIA score is from −200% to +200%. Negative values indicate lower summed pain scores and morphine requirement compared with the entire population.

To assess the participants’ pain, we investigated the distribution of participants’ pain (i.e. proportions of participants having mild, moderate or severe pain), and the proportions of participants having a SIA score of −200 to −100%, −100 to 100% and 100 to 200%.

Preoperative prediction of postoperative pain

To identify potential risk factors for severe postoperative pain we dichotomised pain during 30° flexion of the hip 24 h postoperatively to severe (VAS 61–100 mm) vs. mild-moderate (VAS 0–60 mm). The potential risk factors were chosen based on prior literature suggesting association with postoperative pain [14], [15], [16]. We chose the following potential risk factors: age (continuous), sex (female vs. male), BMI (continuous), ASA-score (dichotomised to I-II vs. III), use of analgesic medications prior to the surgery (none, non-opioid, weak opioid), type of anaesthesia (GA vs. spinal), type of THA (cemented/hybrid vs. no cement), surgical approach (lateral vs. posterior), and duration of surgery (continuous).

Statistical analysis

We assessed the data for normality by inspecting qq-plots and histograms. Data are presented as numbers and percentages, mean and SD, median and interquartile range as appropriate. Statistical tests were chi-squared test, Kruskal Wallis test, ANOVA, and Mann-Whitney U-test as appropriate.

We calculated number needed to treat (NNT) to achieve mild pain (VAS 0–30 mm) between two randomisation groups. NNT was calculated from the logistic regression model (with site as a covariate), if the pairwise comparison was statistically significant, using an online calculator [17].

For the logistic prediction models, we used both univariate and multiple regression. In the multiple logistic regression model, we used backwards stepwise regression removing one covariate (with the highest p-value) at the time. All models had site and randomisation group as co-variates. As sensitivity analyses, all models were done without dichotomising the dependent variable.

The level of significance was predefined and set to 0.01 (a modified Bonferroni correction) for the pairwise comparisons of participants experiencing mild pain to avoid issues with mass significance. For all other outcomes the level of significance was 0.05. Confidence intervals were 99 and 95% accordingly. The Rstudio version 1.1.383 was used for all analyses.

Results

All 556 participants from the mITT population were included in the analyses. Patient characteristics are described in detail elsewhere [11] and are outlined in Table 1.

Demographics. Data from the PANSAID trial.

| Paracetamol 1 g + ibuprofen 400 mg (group PCM + IBU) | Paracetamol 1 g + placebo (group PCM) | Placebo + ibuprofen 200 mg (group IBU) | Paracetamol 0.5 g + ibuprofen 200 mg (group HS-PCM + IBU) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of participants | 136 | 142 | 139 | 139 |

| Age, mean (SD), years | 67 (10) | 67 (10) | 67 (11) | 66 (10) |

| Sex, no., % | ||||

| Female | 68 (50) | 66 (46) | 67 (48) | 76 (55) |

| Male | 68 (50) | 76 (54) | 72 (52) | 63 (45) |

| ASA-score, no, % | ||||

| 1 | 34 (25) | 44 (31) | 44 (32) | 43 (31) |

| 2 | 87 (64) | 84 (59) | 80 (57) | 84 (60) |

| 3 | 15 (11) | 14 (10) | 15 (11) | 12 (9) |

| BMI, mean (SD), kg m−2 | 27.7 (4.3) | 27.4 (4.3) | 26.8 (3.9) | 27.6 (4.7) |

| Duration of surgery, mean (SD) (n), min | 54 (19) (135) | 52 (14) (141) | 53 (18) (139) | 53 (15) (139) |

-

ASA, American Society of Anesthesiologists; BMI, Body mass index; SD, standard deviation.

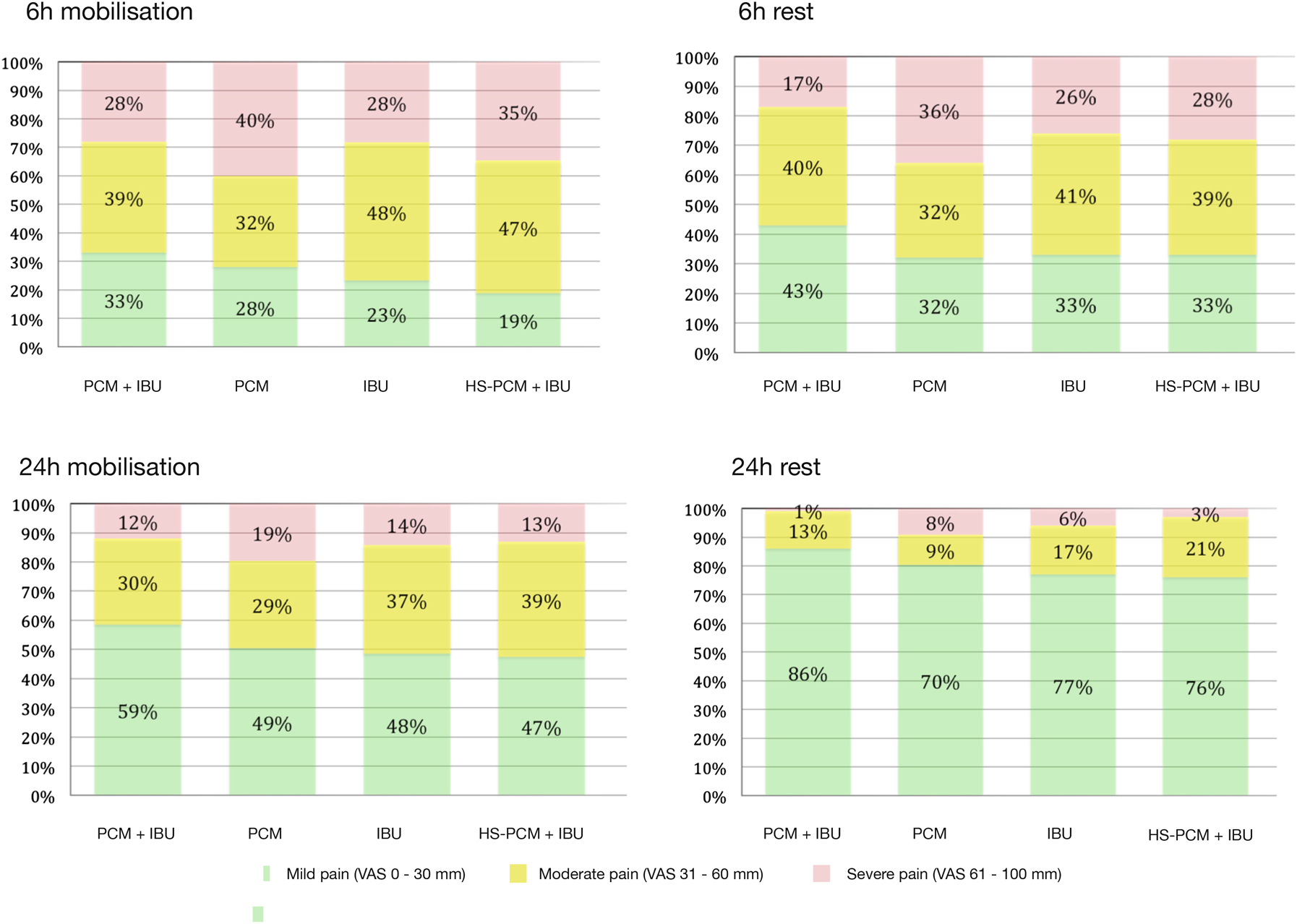

Participants’ pain

During mobilisation at 6 h postoperatively, 33% (95% CI: 26–42) (Group PCM + IBU), 28% (95% CI: 21–37) (Group PCM), 23% (95% CI: 17–31) (group IBU), and 19% (95% CI: 13–27) (Group HS-PCM + IBU) of participants had mild pain (VAS 0–30 mm). Proportions of participants experiencing mild, moderate, and severe pain at rest and at 24 h postoperatively can be seen in Figure 1 and Table S1.

The proportion of patients achieving mild pain, moderate pain and severe pain during 30° flexion of the hip and at rest in each group 6 and 24 h postoperatively.

Green, mild pain (VAS 0–30 mm); yellow, moderate pain (VAS 31–60 mm); red, severe pain (VAS 61–100 mm).

In pairwise comparisons of participants experiencing mild pain, there were two statistically significant comparisons (Group PCM + IBU vs. Group HS-PCM + IBU at 6 h postoperatively during mobilisation: OR for having mild pain was 2.22 (95% CI: 1.27–4.00; p=0.0006; NNT=7; 95% CI: 3–26); and Group PCM + IBU vs. Group PCM at 24 h postoperatively at rest: OR for having mild pain was 2.63 (95% CI: 1.43–5.00, p=0.002; NNT=6, 95% CI: 5–14)).

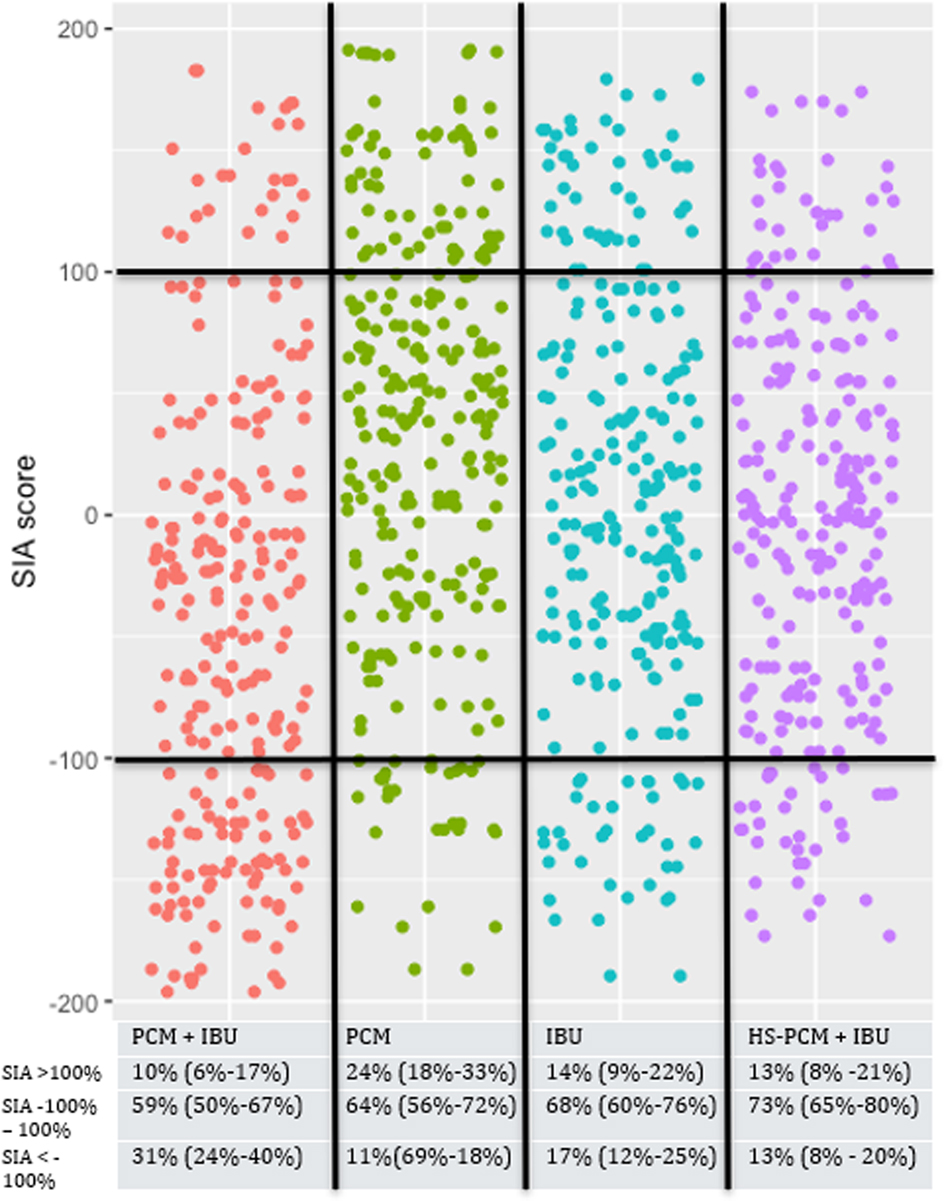

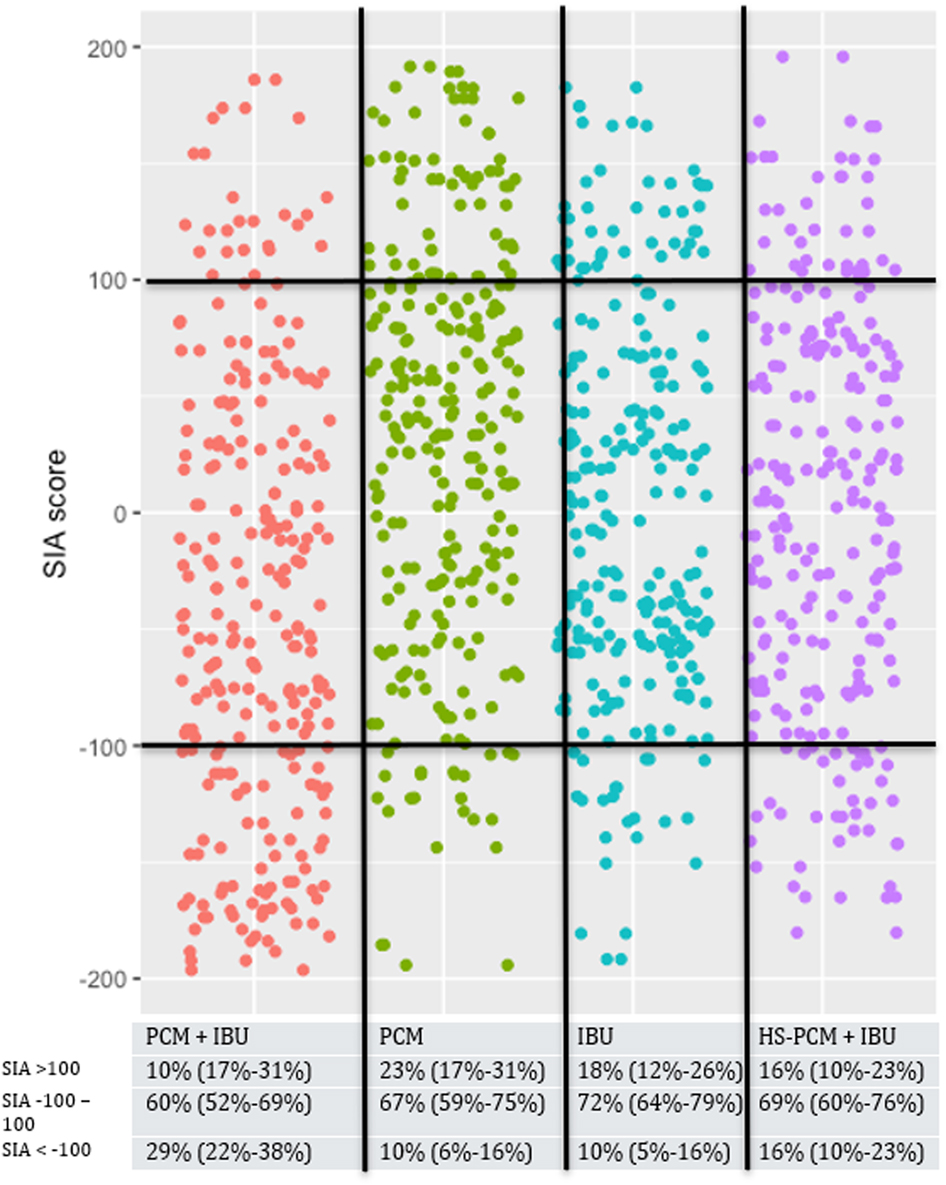

Median SIA scores at rest were: Group PCM + IBU: −36% (IQR: −124 to 12), Group PCM: 41% (IQR: −31 to 99), Group IBU: −2% (IQR: −52 to 70), and Group HS-PCM + IBU: 0% (IQR: −70 to 56) (overall difference: p=0.0001). Median SIA scores during mobilisation were: Group PCM + IBU: −48% (IQR: −112 to 31), Group PCM: 40% (IQR: −31 to 97), Group IBU: −5% (IQR: −57 to 67), and Group HS-PCM + IBU: 6% (IQR: −70 to 74) (overall difference: p=0.0001).

The distribution of SIA scores of participants in the four intervention groups are presented in Figures 2 and 3. In general, more participants in Group PCM + IBU had SIA-scores<−100% than all other groups, both at rest (Figure 2) and during mobilisation (Figure 3).

The Silverman integrated approach combining pain at rest and morphine consumption.

Red, paracetamol 1 g + ibuprofen 400 mg; green, paracetamol 1 g; blue, ibuprofen 400 mg; purple, paracetamol 0.5 g + ibuprofen 200 mg. Each dot represents a single patient.

The Silverman integrated approach combining pain during mobilisation and morphine.

Red, paracetamol 1 g + ibuprofen 400 mg; green, paracetamol 1 g; blue, ibuprofen 400 mg; purple, paracetamol 0.5 g + ibuprofen 200 mg. Each dot represents a single patient.

Prediction

One hundred and forty-two of five hundred and thirty-three participants had severe pain 24 h postoperatively during mobilisation. Results from the prediction models are found in Table 2. The surgical approach was found as a statistically significant covariate for predicting severe pain in the univariate analysis (OR 0.39, 95% CI: 0.25–0.62, p<0.001 for lateral approach compared with posterior approach, lateral approach less likely to have severe pain), but because of collinearity and perfect prediction, the surgical approach could not be evaluated in the multivariate analysis (one of the two surgical approaches were used exclusively at one hospital and the other approach was used exclusively at all other hospitals). Use of non-opioid analgesics prior to surgery compared with no use of analgesics resulted in lower risk of severe pain in both univariate and multivariate analyses and was the only statistically significant covariate after backwards elimination (non-opioid before surgery: OR 0.50, 95% CI: 0.29–0.82, weak opioid before surgery 0.56, 95% CI: 0.28–1.16, reference no analgesic before surgery, overall p-value=0.02).

Multivariable logistic regression model.

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Univariate analyses | Adjusted analyses | Afterwards backwards elimination | |

| OR (95% CI), p-Value | OR (95% CI), p-Value | OR (95% CI), p-Value | |

| Age | 0.99 (0.96–1.01), 0.16 | 0.98 (0.96–1.01), 0.18 | |

| Sex (reference: male) | 1.30 (0.87–1.94), 0.20 | 1.19 (0.78–1.83), 0.42 | |

| BMI | 1.01 (0.97–1.06), 0.60 | 1.01 (0.96–1.06), 0.69 | |

| ASA (reference: I + II) | 0.97 (0.51–1.95), 0.94 | 0.91 (0.46–1.90), 0.80 | |

| Use of analgesics (reference: none) | |||

|

0.50 (0.29–0.82) | 0.51 (0.30–0.86) | 0.50 (0.29–0.82) |

|

0.56 (0.28–1.16), 0.02 | 0.61 (0.29–1.28), 0.04 | 0.56 (0.28–1.16), 0.02 |

| Type of anaesthesia (spinal anaesthesia vs. general anaesthesia) | 0.89 (0.56–1.44), 0.63 | 0.87 (0.53–1.43), 0.58 | |

| Type of THA (reference: cemented) | 0.97 (0.51–1.91), 0.93 | 1.29 (0.60–2.87), 0.52 | |

| Surgical approach (reference: posterior) | 0.39 (0.25–0.63), <0.001 | NA | |

| Surgery time | 1.003 (1.00–1.02), 0.64 | 1.00 (0.98–1.02), 0.99 |

-

Univariate analyses are adjusted for site and randomisation group. Multivariate analyses are adjusted for all co-variate (rows in the table) in addition to site and randomisation group. If OR>1 the reference group had lower odds of severe pain, and vice versa. OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval; BMI, body mass index; ASA, American society of anaesthesiologists; GA, general anaesthesia; THA, total hip arthroplasty; NA, not available because of collinearity.

Discussion

In this re-analysis of the PANSAID trial, we present participants’ pain response. The main findings are that a relatively large proportion of participants did not experience mild pain at 6 h postoperatively both at rest and during mobilisation across all intervention groups. Although more participants had mild pain at 24 h, the proportion of patients not achieving mild pain was still relatively high. When investigating risk factors for severe pain we found use of non-opioid analgesics prior to surgery to be associated with less severe pain.

We consistently found numerically more participants experiencing mild pain, and participants with SIA-scores of less than −100%, for the combination of paracetamol and ibuprofen compared with all other groups at rest and during mobilisation. Although this was not statistically significant at every time point, possibly because of reduced power when dichotomising data [18], these findings support the claim that a combination of paracetamol and ibuprofen may be superior to paracetamol alone, ibuprofen alone and a combination of paracetamol and ibuprofen in lower dosages.

Using paracetamol and ibuprofen, 59% of participants had mild pain after 24 h during mobilisation. This renders more than 40% of the participants with moderate or severe pain, which may impair functional recovery and delay patients’ return to normal activities [19]. For some patients, a more extensive non-opioid analgesic regimen may be needed. However, both benefits and harm of adding further analgesics to the regimen should optimally be investigated in sufficiently powered clinical trials, as effects and harm of combining more than two analgesics are virtually unknown [20].

For pairwise comparisons of proportions of participants experiencing “no more than mild pain”, only two analyses between groups were statistically significant. Although the notion that “no more than mild pain” [2] should be the primary objective in pain treatment is relevant, the implications must be considered carefully when using a dichotomised outcome as a primary outcome in clinical trials. These implications include: (1) information loss (reduced power) [18], [, 21], (2) the underlying distribution of the data can potentially have huge impact on the results when continuous data are dichotomised to an arbitrarily chosen cut-point [22], (3) difficulties assessing clinically relevant differences between groups (i.e. a relatively large proportion of participants can cross the arbitrarily chosen cut-point and still have clinically irrelevant reductions in pain) [23], (4) when only focusing on participants crossing a certain cut-point investigators risk ignoring participants getting worse pain, and (5) by reducing pain to a number that must be achieved clinicians risk ignoring other outcomes important to the specific patient (ability mobilise, take deep breaths etc.) [24].

Pain is inherently difficult to quantify and is often confounded by use of opioids as needed. The Silverman Integrated Approach is postulated to integrate VAS scores and opioid use and enhance power [5], [, 7]. An advantage of the SIA score is that is combines pain scores and opioid use for each patient. A major drawback when using the SIA score is the equal weighing of pain and opioid use. Most can agree that a SIA score<−100% (using less opioid and having less pain) is positive but some patient may prefer high pain scores over high opioid use, or low pain scores with a high opioid use. Therefore, the interpretation of the SIA-score is difficult. Further, the SIA-score is based on ranks and not actual pain scores and opioid use and, therefore, the clinical relevance of a given difference is difficult to assess.

In this re-analysis we sought to identify participants at risk of having severe pain after 24 h. In the multivariable regression model (after backward elimination of initial chosen covariates), we found use of non-opioid analgesics prior to the surgery to have a substantial reduced risk of postoperative severe pain compared with no use of analgesics prior to surgery. This is a curious finding as previous studies have found use of (opioid) analgesics to be a risk factor for severe pain [15]. Use of analgesics prior to surgery was included as a surrogate marker for pre-operative pain as studies [1], [, 14] have found preoperative pain to be associated with postoperative pain. The use of analgesics as a marker for preoperative pain is suboptimal as there are numerous explanations on why patients use, do not use or discontinue analgesics, including lack of effect and adverse drug effects. Further, patients having severe preoperative pain would probably have been excluded from the original trial because daily use of opioid use was an exclusion criterium. Additionally, due to the pragmatic nature of the original trial, numerous factors associated with postoperative pain are not accounted for (e.g. anxiety, fear, and response to experimental pain [25]) and residual confounding is likely to be present, thus limiting the value of this prediction analysis.

The strengths of this study include that data arise from a trial with overall low risk of bias and few missing data. Furthermore, a study protocol was made publicly available before randomisation of the last patient and before data were accessible in order to avoid data-driven analyses and selective outcome reporting.

This study has several limitations. First, categorising continuous data has several potential limitations (see paragraph above) and may result in “loss of information” and reduced power [18]. The original trial was not powered for analyses with dichotomised data and, consequently, this sub-study may be severely underpowered. Second, the analyses performed for this sub-study were numerous and risk of type I errors exists. Only for the primary outcome were measures taken to avoid statistical significance due to multiplicity, and, thus, all other outcomes should be considered explorative and interpreted with caution. Third, SIA-scores are seldomly used and their limitations are many. These include difficulties in interpreting the results in a clinical context, difficulties in interpretation of opposing directions of opioid use and pain scores, and equal weighting of pain and opioid. In the present sub-study, SIA-scores were derived from VAS-scores at two time points only, and these two measurements may not reflect the patients’ pain the entire 24 h postoperatively. Further, all SIA-scores were not a part of the protocol for this sub-study and, therefore, these should be interpreted with caution. Fourth, the prediction model for severe pain is limited by the inclusion criteria in the original trial and the results therefore have limited generalisability. As previously mentioned, several factors associated with postoperative pain were not measured and substantial residual confounding may exist.

Conclusions

The majority of participants (67–81%) experienced more than mild pain after THA using a combination of paracetamol and ibuprofen or each drug alone as basic non-opioid analgesic treatment. The largest proportion of participants, 33%, experiencing mild pain was found in participants randomised to the combination of paracetamol and ibuprofen. When investigating risk factors for severe pain, we were not able, in any clinically relevant way, to predict severe postoperative pain using easily obtainable pre-surgical measures.

-

Research funding: Authors state only departmental funding were involved with this sub-study. The main trial was funded by The Danish Society of Anaesthesiology and Intensive Care Medicine (DASAIM), ‘Sophus Johansens Fond’, ‘Region Zealand Health Scientific Research Foundation’, ‘The local research foundation at Næstved-Slagelse-Ringsted Hospitals’, ‘The A.P. Møller Foundation for the Advancement of Medical Science’ and ‘Aase og Ejnar Danielsens Fond’. ‘Grosserer Chr. Andersen og Hustru Ingeborg Andersen, f. Schmidts legat (fond)’. The funders had no role in the design and conduct of the trial; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript; and decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

-

Author contributions: All authors read and approved the paper. LMI: This author performed all statistical analyses, interpreted the results, drafted the manuscript, approved the final version of the manuscript. KHT: This author supervised all statistical analyses, interpreted the results, drafted the manuscript in collaboration with LMI, approved the final version of the manuscript. DHP: This author interpreted the study results, critically revised the manuscript, approved the final version of the manuscript. JW: This author interpreted the study results, critically revised the manuscript, approved the final version of the manuscript. JCJ: This author interpreted the study results, critically revised the manuscript, approved the final version of the manuscript. OM: This author interpreted the study results, critically revised the manuscript, approved the final version of the manuscript.

-

Competing interests: Dr. Overgaard reports grants from Zimmer Biomet, outside the submitted work. Otherwise, none.

-

Informed consent: Informed consent has been obtained from all individuals included in this study.

-

Ethical approval: The research related to human use complies with all the relevant national regulations, institutional policies and was performed in accordance with the tenets of the Helsinki Declaration, and has been approved by the authors’ institutional review board or equivalent committee.

Proportion of patients experiencing mild, moderate and severe pain.

| Mobilisation, 6 h | Paracetamol 1 g + ibuprofen 400 mg | Paracetamol 1 g + placebo | Placebo + ibuprofen 200 mg | Paracetamol 0.5 g + ibuprofen 200 mg | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mild pain, % (95% CI) | 33 (26–42) | 28 (21–37) | 23 (17–31) | 19 (13–27) | 0.05 |

| Moderate pain, % (95% CI) | 39 (30–48) | 32 (25–41) | 48 (40–58) | 47 (38–56) | |

| Severe pain, % (95% CI) | 28 (21–37) | 40 (31–48) | 28 (21–37) | 35 (26–43) | |

| Rest, 6 h | |||||

| Mild pain, % (95% CI) | 59 (50–67) | 49 (40–57) | 48 (40–57) | 47 (39–56) | 0.23 |

| Moderate pain, % (95% CI) | 30 (22–38) | 29 (22–37) | 37 (29–46) | 39 (31–48) | |

| Severe pain, % (95% CI) | 12 (7–19) | 19 (13–26) | 14 (9–22) | 13 (8–21) | |

| Mobilisation, 24 h | |||||

| Mild pain, % (95% CI) | 43 (35–52) | 32 (25–41) | 33 (25–42) | 33 (25–42) | 0.18 |

| Moderate pain, % (95% CI) | 40 (32–49) | 32 (25–41) | 41 (33–50) | 39 (31–48) | |

| Severe pain, % (95% CI) | 17 (11–24) | 36 (28–44) | 26 (19–34) | 28 (21–36) | |

| Rest, 24 h | |||||

| Mild pain, % (95% CI) | 86 (78–91) | 70 (62–77) | 77 (69–84) | 76 (67–82) | 0.02 |

| Moderate pain, % (95% CI) | 13 (8–21) | 9 (5–16) | 17 (11–25) | 21 (15–30) | |

| Severe pain, % (95% CI) | 1 (0–5) | 18 (4–14) | 6 (3–12) | 3 (1–8) | |

-

Mobilisation measured during 30° flexion of the hip. p-values are chi-squared test.

References

1. Sommer, M, de Rijke, JM, van Kleef, M, Kessels, AG, Peters, ML, Geurts, JW, et al.. The prevalence of postoperative pain in a sample of 1490 surgical inpatients. Eur J Anaesthesiol 2008;25:267–74. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0265021507003031.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

2. Moore, RA, Straube, S, Aldington, D. Pain measures and cut-offs – ‘no worse than mild pain’ as a simple, universal outcome. Anaesthesia 2013;68:400–12. https://doi.org/10.1111/anae.12148.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

3. Barden, J, Edwards, JE, Mason, L, McQuay, HJ, Moore, RA. Outcomes in acute pain trials: systematic review of what was reported? Pain 2004;109:351–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pain.2004.01.032.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

4. Breivik, H, Borchgrevink, PC, Allen, SM, Rosseland, LA, Romundstad, L, Hals, EK, et al.. Assessment of pain. Br J Anaesth 2008;101:17–24. https://doi.org/10.1093/bja/aen103.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

5. Dai, F, Silverman, DG, Chelly, JE, Li, J, Belfer, I, Qin, L. Integration of pain score and morphine consumption in analgesic clinical studies. J Pain 2013;14:767–77.e8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpain.2013.04.004.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

6. Silverman, DG, O’Connor, TZ, Brull, SJ. Integrated assessment of pain scores and rescue morphine use during studies of analgesic efficacy. Anesth Analg 1993;77:168–70.10.1213/00000539-199307000-00033Suche in Google Scholar

7. Andersen, LPK, Gogenur, I, Torup, H, Rosenberg, J, Werner, MU. Assessment of postoperative analgesic drug efficacy: method of data analysis is critical. Anesth Analg 2017;125:1008–13. https://doi.org/10.1213/ANE.0000000000002007.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

8. Benzon, HT, Mascha, EJ, Wu, CL. Studies on postoperative analgesic efficacy: focusing the statistical methods and broadening outcome measures and measurement tools. Anesth Analg 2017;125:726–8. https://doi.org/10.1213/ANE.0000000000002218.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

9. Brummett, CM, Clauw, DJ. Flipping the paradigm: from surgery-specific to patient-driven perioperative analgesic algorithms. Anesthesiology 2015;122:731–3. https://doi.org/10.1097/ALN.0000000000000598.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

10. Thybo, KH, Hägi-Pedersen, D. Individual pain response and prediction of pain: preplanned sub-study of the PANSAID trial; 2017. Available from: https://docs.google.com/viewerng/viewer?url=http://pansaid.dk/onewebmedia/Protocol_Individual%2520pain%2520response%2520and%2520prediction_FINAL_version%25201.pdf [Accessed 15 Aug 2018].Suche in Google Scholar

11. Thybo, KH, Hagi-Pedersen, D, Dahl, JB, Wetterslev, J, Nersesjan, M, Jakobsen, JC, et al.. Effect of combination of paracetamol (acetaminophen) and ibuprofen vs. either alone on patient-controlled morphine consumption in the first 24 h after total hip arthroplasty: the PANSAID randomized clinical trial. J Am Med Assoc 2019;321:562–71. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2018.22039.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

12. Thybo, KH, Jakobsen, JC, Hagi-Pedersen, D, Pedersen, NA, Dahl, JB, Schroder, HM, et al.. PANSAID-paracetamol and NSAID in combination: detailed statistical analysis plan for a randomised, blinded, parallel, four-group multicentre clinical trial. Trials 2017;18:465. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13063-017-2203-1.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

13. Thybo, KH, Hagi-Pedersen, D, Wetterslev, J, Dahl, JB, Schroder, HM, Bulow, HH, et al.. PANSAID-paracetamol and NSAID in combination: study protocol for a randomised trial. Trials 2017;18:11. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13063-016-1749-7.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

14. Kalkman, CJ, Visser, K, Moen, J, Bonsel, GJ, Grobbee, DE, Moons, KG. Preoperative prediction of severe postoperative pain. Pain 2003;105:415–23. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0304-3959(03)00252-5.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

15. Liu, SS, Buvanendran, A, Rathmell, JP, Sawhney, M, Bae, JJ, Moric, M, et al.. Predictors for moderate to severe acute postoperative pain after total hip and knee replacement. Int Orthop 2012;36:2261–7. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00264-012-1623-5.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

16. Mei, W, Seeling, M, Franck, M, Radtke, F, Brantner, B, Wernecke, KD, et al.. Independent risk factors for postoperative pain in need of intervention early after awakening from general anaesthesia. Eur J Pain 2010;14:149 e1–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejpain.2009.03.009.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

17. Knowledge Translation Program. Evidence-based medicine toolbox; 2017. Available from: https://ebm-tools.knowledgetranslation.net/calculator/converter/ [Accessed 28 Jan 2020].Suche in Google Scholar

18. Altman, DG, Royston, P. The cost of dichotomising continuous variables. BMJ 2006;332:1080. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.332.7549.1080.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

19. Kehlet, H, Dahl, JB. Anaesthesia, surgery, and challenges in postoperative recovery. Lancet 2003;362:1921–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(03)14966-5.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

20. Mathiesen, O, Wetterslev, J, Kontinen, VK, Pommergaard, HC, Nikolajsen, L, Rosenberg, J, et al.. Adverse effects of perioperative paracetamol, NSAIDs, glucocorticoids, gabapentinoids and their combinations: a topical review. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand 2014;58:1182–98. https://doi.org/10.1111/aas.12380.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

21. Dawson, NV, Weiss, R. Dichotomizing continuous variables in statistical analysis: a practice to avoid. Med Decis Making 2012;32:225–6. https://doi.org/10.1177/0272989X12437605.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

22. Ragland, DR. Dichotomizing continuous outcome variables: dependence of the magnitude of association and statistical power on the cutpoint. Epidemiology 1992;3:434–40. https://doi.org/10.1097/00001648-199209000-00009.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

23. McGlothlin, AE, Lewis, RJ. Minimal clinically important difference: defining what really matters to patients. J Am Med Assoc 2014;312:1342–3. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2014.13128.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

24. Tan, SG, Cyna, AM. Subjective and objective experience of pain. Anaesthesia 2013;68:785–6. https://doi.org/10.1111/anae.12335.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

25. Werner, MU, Mjobo, HN, Nielsen, PR, Rudin, A. Prediction of postoperative pain: a systematic review of predictive experimental pain studies. Anesthesiology 2010;112:1494–502. https://doi.org/10.1097/ALN.0b013e3181dcd5a0.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

© 2020 Walter de Gruyter GmbH, Berlin/Boston

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Frontmatter

- Editorial

- Salami-slicing and duplicate publication: gatekeepers challenges

- Editorial Comment

- Risk for persistent post-delivery pain – increased by pre-pregnancy pain and depression. Similar to persistent post-surgical pain in general?

- Systematic Review

- Acute experimentally-induced pain replicates the distribution but not the quality or behaviour of clinical appendicular musculoskeletal pain. A systematic review

- Topical Review

- Unwillingly traumatizing: is there a psycho-traumatologic pathway from general surgery to postoperative maladaptation?

- Clinical Pain Research

- Translation, cross-cultural adaptation and psychometric evaluation of the Thai version of the fear-avoidance beliefs questionnaire in patients with non-specific neck pain

- Pain management in patients undergoing radiation therapy for head and neck cancer – a descriptive study

- Do intensity of pain alone or combined with pain duration best reflect clinical signs in the neck, shoulder and upper limb?

- Different pain variables could independently predict anxiety and depression in subjects with chronic musculoskeletal pain

- Symptoms of central sensitization in patients with inflammatory bowel diseases: a case-control study examining the role of musculoskeletal pain and psychological factors

- Acceptability of psychologically-based pain management and online delivery for people living with HIV and chronic neuropathic pain: a qualitative study

- Determinants of pain occurrence in dance teachers

- Observational Studies

- A retrospective observational study comparing somatosensory amplification in fibromyalgia, chronic pain, psychiatric disorders and healthy subjects

- Utilisation of pain counselling in osteopathic practice: secondary analysis of a nationally representative sample of Australian osteopaths

- Effectiveness of ESPITO analgesia in enhancing recovery in patients undergoing open radical cystectomy when compared to a contemporaneous cohort receiving standard analgesia: an observational study

- Shoulder patients in primary and specialist health care. A cross-sectional study

- The tolerance to stretch is linked with endogenous modulation of pain

- Pain sensitivity increases more in younger runners during an ultra-marathon

- Original Experimental

- DNA methylation changes in genes involved in inflammation and depression in fibromyalgia: a pilot study

- Participants with mild, moderate, or severe pain following total hip arthroplasty. A sub-study of the PANSAID trial on paracetamol and ibuprofen for postoperative pain treatment

- Exploring peoples’ lived experience of complex regional pain syndrome in Australia: a qualitative study

- Although tapentadol and oxycodone both increase colonic volume, tapentadol treatment resulted in softer stools and less constipation: a mechanistic study in healthy volunteers

- Educational Case Report

- Updated management of occipital nerve stimulator lead migration: case report of a technical challenge

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Frontmatter

- Editorial

- Salami-slicing and duplicate publication: gatekeepers challenges

- Editorial Comment

- Risk for persistent post-delivery pain – increased by pre-pregnancy pain and depression. Similar to persistent post-surgical pain in general?

- Systematic Review

- Acute experimentally-induced pain replicates the distribution but not the quality or behaviour of clinical appendicular musculoskeletal pain. A systematic review

- Topical Review

- Unwillingly traumatizing: is there a psycho-traumatologic pathway from general surgery to postoperative maladaptation?

- Clinical Pain Research

- Translation, cross-cultural adaptation and psychometric evaluation of the Thai version of the fear-avoidance beliefs questionnaire in patients with non-specific neck pain

- Pain management in patients undergoing radiation therapy for head and neck cancer – a descriptive study

- Do intensity of pain alone or combined with pain duration best reflect clinical signs in the neck, shoulder and upper limb?

- Different pain variables could independently predict anxiety and depression in subjects with chronic musculoskeletal pain

- Symptoms of central sensitization in patients with inflammatory bowel diseases: a case-control study examining the role of musculoskeletal pain and psychological factors

- Acceptability of psychologically-based pain management and online delivery for people living with HIV and chronic neuropathic pain: a qualitative study

- Determinants of pain occurrence in dance teachers

- Observational Studies

- A retrospective observational study comparing somatosensory amplification in fibromyalgia, chronic pain, psychiatric disorders and healthy subjects

- Utilisation of pain counselling in osteopathic practice: secondary analysis of a nationally representative sample of Australian osteopaths

- Effectiveness of ESPITO analgesia in enhancing recovery in patients undergoing open radical cystectomy when compared to a contemporaneous cohort receiving standard analgesia: an observational study

- Shoulder patients in primary and specialist health care. A cross-sectional study

- The tolerance to stretch is linked with endogenous modulation of pain

- Pain sensitivity increases more in younger runners during an ultra-marathon

- Original Experimental

- DNA methylation changes in genes involved in inflammation and depression in fibromyalgia: a pilot study

- Participants with mild, moderate, or severe pain following total hip arthroplasty. A sub-study of the PANSAID trial on paracetamol and ibuprofen for postoperative pain treatment

- Exploring peoples’ lived experience of complex regional pain syndrome in Australia: a qualitative study

- Although tapentadol and oxycodone both increase colonic volume, tapentadol treatment resulted in softer stools and less constipation: a mechanistic study in healthy volunteers

- Educational Case Report

- Updated management of occipital nerve stimulator lead migration: case report of a technical challenge