Abstract

Electrode migration is a challenge, even with adequate anchoring techniques, due to the high mechanical stress on components of occipital nerve stimulation (ONS) for headache disorders. When a lead displacement of an ONS implant is diagnosed, there are currently different approaches described for its management. Nevertheless current neuromodulation devices are designed like a continuum of components without any intermediate connector, and if a lead displacement is diagnosed, the solution is the complete removal of the electrode from its placement, and its repositioning through an ex-novo procedure. The described technique can allow ONS leads to be revised while minimizing the need to reopen incisions over the IPG, thus improving patients’ intraoperative and postoperative discomfort, shortening surgical time and medical costs, reasonably reducing the incidence of infective postoperative complications.

Introduction

Chronic daily headache (CDH) is a major worldwide health problem [1], [2], [3], [4] that affects 3–5% of the population and results in substantial disability [1]. The term CDH refers to headaches disorders that occur on 15 or more days per month for more than three months.

Migraine and cluster headache are the most common disabling primary headache disorders [5] (any pathological process other than the functional derangement of the pain neuromatrix), with migraine ranked as the first cause of disability in people under the age of fifty [3]. Chronic cluster headache (CCH) and chronic migraine (CM) have a substantial impact on health-related quality of life (HRQOL), as well as on social and economic costs (SEC) [6], [7], [8], [9], [10], [11].

Migraine headache is usually one-sided, often throbbing, and may be accompanied by nausea/vomiting or sensitivity to light. Episodes last from hours up to a few days.

In cluster headache, pain is located in or around the eye or temple and affects only one side of the head, which for most patients is always the same side. It is accompanied by other symptoms including facial flushing, tearing, and running nose. Individual attacks typically last from 15 min to 3 h and come in clusters lasting weeks to months during which there may be multiple episodes per day. In most cases, there are lengthy headache-free periods (months to years) between clusters.

Occipital neuralgia (ON), also known as C2 neuralgia, involves paroxysmal shooting or stabbing pain in the dermatomes of the greater occipital nerve (GON or nervus occipitalis major) and the lesser occipital nerve (LON or nervus occipitalis minor). From an origin in the suboccipital region, the pain spreads throughout the vertex, particularly the upper neck, back of the head, and behind the eyes. The pain may be accompanied by hypesthesia or dysesthesia in the affected areas. The most common trigger is compression of the GON or LON [12], with the GON more frequently involved (90%) than the LON (10%).

Advances in the management of headache disorders have meant that a substantial proportion of patients can be effectively treated with medical treatments; these often focuses on either abortive or prophylactic therapy.

Medical treatment of patients with chronic primary headache syndromes (such as chronic migraine, chronic cluster headache, chronic tension-type headache or hemicrania continua) is particularly challenging as valid studies are few and, in many cases, even higher doses of preventative medications are ineffective and adverse side effects frequently complicate the course of medical treatment. Chronic headaches that do not or no longer respond to prophylaxis are commonly encountered at tertiary level headache centres. The vast majority of these patients suffer from medication overuse headache (reported for up to 78% of patients with chronic migraine) [13], [14], [15].

Indeed, some patients may be intractable to the therapies recommended by national guidelines; in these patients, i.e. when the intolerance or lack of responsiveness to conservative treatments is ascertained, surgical options and neuromodulatory treatments could be considered.

Surgical options have previously ranged from radiofrequency rhizotomy of the Gasserian ganglion or of the trigeminal nerve, application of glycerol or local anaesthetics into the cisterna trigeminalis of the Gasserian ganglion; resection or blockade of the N. petrosus superficialis or of the ganglion sphenopalatinum; microvascular decompression; and to a whole range of other ablative or destructive methods.

Case reports of the complete inefficacy of surgical treatment in cluster headache and related syndromes exists [16], [17], [18], as well there is insufficient evidence to support the effectiveness of any specific surgical intervention for chronic migraine, especially with regard to permanent relief [19]. It follows that surgical procedures should be considered with great caution because no reliable long-term observational data are available and because they can induce a secondary chronic pain condition.

Technical progress has introduced the opportunity to use neurostimulation rather than ablative or destructive methods and it may be applied to virtually any neural structure, including peripheral nerves. Generally speaking, it is clear that the most effective and least invasive strategy must be preferred as first-line therapy for intractable chronic headaches [20]. For this reason, neurostimulation should only be considered in patients that have tried all first-line therapies recommended in European guidelines [21], and minimally invasive techniques like an ONS implant can be considered reliable options.

Lead migration is the most frequent hardware complication reported in patients carrying peripheral implants, requiring surgical revision. In 2007, Schwedt et al. [22], described 60% of his patients requiring a revision of their lead secondary to migration. In a systematic review Jasper et al. reported lead displacement for percutaneous cylindrical leads in 30 out of 115 patients and in two out of 35 patients with paddle type leads [23]. Other common concerns include complications related to the Implantable Pulse Generator (battery depletion, flipping, recharging difficulties) and infective complications, the latter ranging between 0 and 10% (excluding one case studies reporting an incidence of 28.5% [24], with an overall removals request incidence of 2.8%) [23], [, 25].

Different techniques for leads repositioning have been described in literature, each carrying pros and cons. This article will focus on the occipital nerve stimulation implant, describing a technique for the management of lead migration. The importance of this method is related to the opportunity to replace the implants’ leads through the same incision at the base of the occipital area used for the implant, avoiding further unnecessary surgical incisions specifically at the level of the scalp (where there is a higher risk of infection). This technique can reduce patients discomfort, the chances of “in situ” infection, and possibly reduce the intraoperative time and costs.

Case report

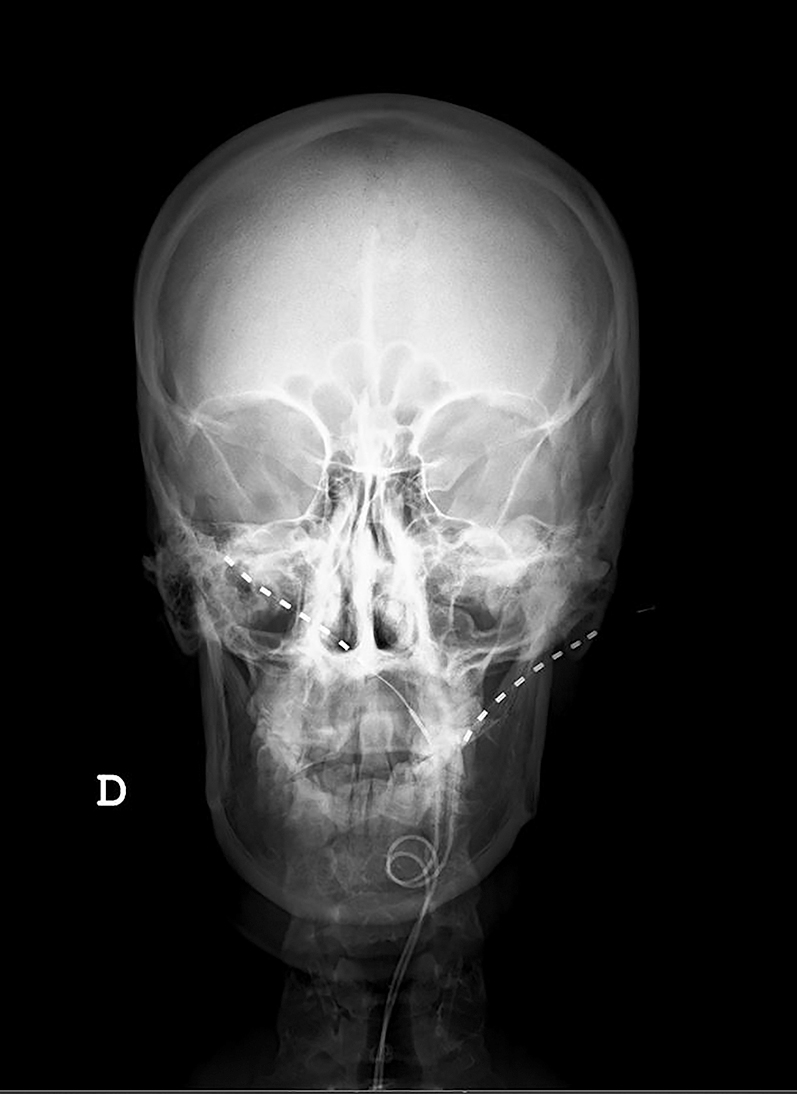

Twenty nine-year-old patient referred due to bilateral Arnold neuralgia and long-term cervicogenic headache. She was refractory to pharmacological treatment and repeated minimally invasive techniques on dorsal root ganglia and terminal branches of C2C3. According to previous background, the patient was scheduled for subcutaneous ONS. Under monitored sedation, bilateral occipital subcutaneous leads implant was performed. Two 90 cm Vectris Surescan electrodes, model 977A275 (Medtronic, Minneapolis, MN, USA), were placed with the introduction site at the level of C1C2. The tips of the leads in correspondence to the mastoid process were checked, the electrodes position overlapping with the patient’s pain area was monitored, without motor response to the cranial musculature that could lead to painful muscle stimulation [26] (in this phase the sedation was temporary interrupted to receive a functional feedback from the patient). Once adequate coverage was obtained of the symptomatic area, leads anchoring was done at the entry point , in the cervical paraspinal fascia using the Injex Bumpy lead anchor, model 97791 (Medtronic, Minneapolis, MN, USA). Strain-relieving, subcutaneous lead loops were used to absorb the stress of cervical movements, and minimize the risk of lead migration, as it is shown in Figures 1 and 2.

Radiographic scans at initial placement with leads entry point at C1 showing right higher than left placed.

Lateral fluoroscopy view at initial placement with leads entry point at C1.

Temporary extensions were connected to the implanted leads, with the exit at the level of the right flank and connection to the external battery by means of a 97725 single-use external sterile wireless neurostimulator. The patient remained in successful follow-up with a satisfactory system test for 15 days (where a satisfactory system test is considered the reduction of occipital headache of at least 50% from the average pre-implantation on a numeric rate scale), after which, new admission and final implant was performed. Previous surgical field was reopened and previously implanted electrodes were located, followed by disconnection from the temporal extensions. A subcutaneous pocket was then created on the left paraspinous flank in the scapular midline to house the internal power generator (IPG). Next step consisted of subcutaneous tunnelling of the leads up to the pocket for connection to the Intellis 97755 generator (Medtronic, Minneapolis, MN, USA). Impedance tests were performed to check the circuit, with optimal results. Battery fixation with non-absorbable suture, layered closure with absorbable suture, and intradermal synthetic absorbable skin suture represented the last steps.

Figures 1 and 2 show the final position of the implanted leads.

After a 30 days use period, a difference in clinical effectiveness was observed between the left and right lead, with better control of symptoms on the right side. Reprogramming was attempted without success, so it was decided to reschedule the patient for left electrode repositioning under monitored sedation.

Since the electrodes had not intermediate connections, obviously the first possibility was to disconnect the battery, and extract the entire electrode by 90 cm, to carry out a completely new process. Considered the young age of the patient and the consequences of this technique, determining both an additional trauma and new scars, we decided to proceed with a different technique.

The puncture with the Tuohy needle, performed in a “out-in” direction, was an already published possibility [27], but the patient refused to be shaved at the scalp level (beyond the site where the procedure was already performed).

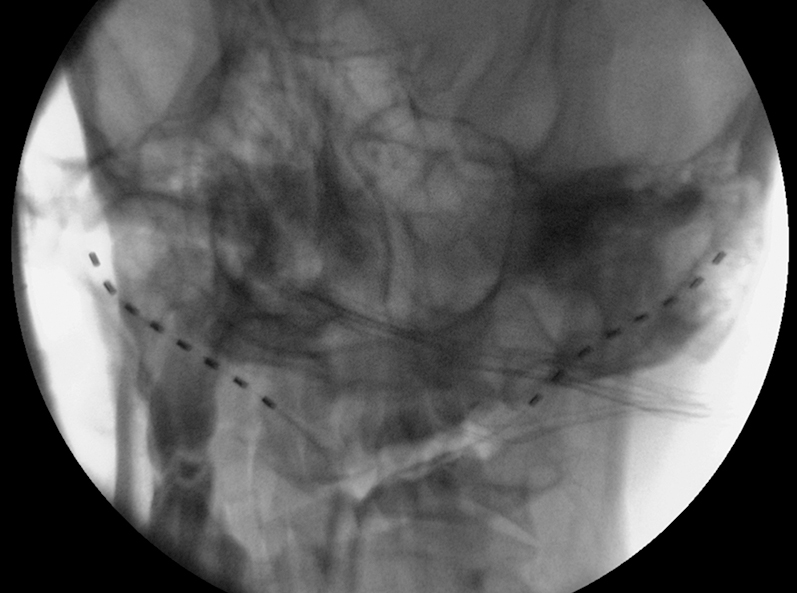

A sterile disposable needle with peel-away sheath, was presented by Shaw et al. [28], applied to peripheral field stimulation trial for low back pain syndrome. With this in mind, we decided to use an Introducer Needle with a T-Peel sheath 8,255 cm length, 17 GA (Avanos Medical, Inc. Alpharetta, GA, USA) (Figure 3). We used the same access selected for the initial implantation, at the C1C2 level, dissecting the planes until we found the anchor corresponding to the left electrode. Gentle removal of anchor, was done using anchor removal tool, and also any remaining suture material that was securing the anchor. The tunnelled portion at the cranial (occipital) level was pulled out. Using the introducer needle, performed an X-ray-guided puncture from the incision to the left mastoid process. Once located, the needle and dilator were removed, the cannula was left in place and the lead was introduced through it. Once verified the appropriate location of the electrode, with a simultaneous movement the cannula was pulled back and stripped, while a push pressure was firmly maintained on the inserted lead, to avoid during the maneuver necessary to remove the cannula, lead’s mobilization from the intended position. The final position of repositioned left lead is shown in Figure 4.

ON-Q T-peel introducer needle 3.25 IN-17 GA (Avanos Medical, Inc. Alpharetta, GA, USA).

Fluoroscopic image after left lead revision.

The whole system was then tested and confirmed by the patient to be in satisfactory working condition. The lead was then anchored for avoiding dislodgements; layered wound closure with absorbable suture and skin closure with intradermal synthetic absorbable suture, were completed. The patient was transported to recovery and discharged one day after from the hospital. The patient was seen in the office 10 days and six months after the procedure with no complications and total satisfaction with the result.

Discussion

ONS is a neuromodulation technique aimed at the treatment of different types of primary and secondary intractable headache disorders including migraine, CCH and non-migrainous chronic headaches, cervicogenic headache [29], [, 30] and neuropathic pain in the occipital region [31], [, 32].

The first report of a percutaneous technique for the control of occipital neuralgia was introduced by Weiner et al. [33]. This minimally invasive adjustable, and reversible approach provides an implantable device composed of a subcutaneous regional electrode and a pulse generator; the aim of treatment is preventive, based on a continues regular “tonic” stimulation, that generate paresthesia (stimulation of sphenopalatinum ganglion in contrast is used in episodic manner in response to onset of cluster attacks). Nowadays exists different modality of possible neuromodulatory patterns, producing paraesthesia-free pain relief by stimulating at much higher frequencies than usual (in the kilohertz range rather than the typical 50 Hz) [34], [35], [36], or by delivering stimulation in bursts (short trains of pulses separated by a gap) [37], [, 38].

When a lead displacement of an ONS implant is diagnosed, there are currently five approaches described for its management.

The first involves removing the migrated lead completely and then replacing it with a new lead [39], [, 40]. The second entails dissecting out the migrated lead, burying it, and then suturing the overlaying skin [40]. A third technique involves making an incision over the original anchor site and removing the distal portion of the lead; then a second incision on the opposite side of the occiput is made and a 15-G needle is advanced to the first incision site. The lead is then positioned retrogradely through the needle and the distal end of the occipital lead is sutured to prevent movement [41]. A fourth most recent technique, similar to Gofeld’s, requires less incisions and no distal suturing [40]. A 1.5–2.0 cm “V” shaped incision is made over the midline portion of the lead close to where the proximal anchor is located thus creating a flap; a 15-gauge Tuohy needle is then inserted 2 cm lateral to the most lateral point of the lead along the occiput (latero-medial direction 1 cm parallel and below to the previous tract, until it is visualized through the “V” shaped incision). The displaced lead is then carefully eased through the epidural needle in a medial to lateral direction.

The last technique described by Zimmerman et al. [27], uses a slotted 14-gauge Tuohy needle, modified in such a way that the cannula and head acquire a longitudinal opening or slot, all along the needle. The patient is prepped and draped in sterile fashion, and the anchor site (occipital or retromastoid) is opened through the original incision. The migrated lead is externalized and inspected. Next, the slotted Tuohy needle is inserted with the stylet in place from the incision site along the desired path of the lead, taking care to keep the needle in the subcutaneous fat layer. Next, the stylet is removed and the lead is inserted through the slotted needle.

In our case report, we used a nonspecifically, designed for the procedure, peel-away introducer through a simple median occipital incision (like already described). We must notice a specifically designed needle with a peel-away sheath, the Entrada needle, model SC4220, as a component of Spinal Cord Stimulation System (Boston Scientific, Valencia, CA, USA), which can be used to perform the described technique. Once confirmed the correct placement with fluoroscopy, the needle is removed and the lead is inserted through the peel away cannula. Fluoroscopic check is required before effectively “peel away” the introducer from the situ, leaving the electrode in the right position. Then the lead is fixed and the single incision is sutured. It is important to underline that like in the other technique the leads have to be placed subcutaneously, to avoid direct muscular stimulation.

Conclusion

Peripheral nerve stimulation for headache disorders is actually becoming a more common treatment option, meanwhile subcutaneous electrode migration is still a challenge even with adequate anchoring techniques, due to the high mechanical stress on components in this particular region of the body.

The described technique can allow ONS leads to be revised while minimizing the need to reopen incisions over the IPG and eventually over hairy skull sites, thus improving patients’ intraoperative and postoperative discomfort (also of esthetical kind), shortening surgical time and medical costs, reasonably reducing the incidence of infective postoperative complications.

-

Research funding: None.

-

Author contributions: All authors contributed in some part to the design, and drafting of the manuscript. Jose De Andres and Giuseppe Luca Formicola drafted and initiated the article, and prepared the manuscript draft with important intellectual contributions by Ruben Rubio-Haro and Carmen De Andres-Serrano. All authors contributed to the revision and approved the submitted version of the manuscript.

-

Competing interests: None.

-

Informed consent: Informed consent was obtained from all individuals included in this study.

-

Ethical approval: The local Institutional Review Board deemed the study exempt from review.

References

1. Lambru, G, Matharu, MS. Occipital nerve stimulation in primary headache syndromes. Therapeut Adv Neurol Disord 2012;5:57–67. https://doi.org/10.1177/1756285611420903.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

2. Vos, T, Flaxman, AD, Naghavi, M, Lozano, R, Michaud, C, Ezzati, M, et al.. Years lived with disability (YLDs) for 1160 sequelae of 289 diseases and injuries 1990–2010: a systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study 2010 [published correction appears in Lancet [published correction appears in Lancet. 2013 Feb 23;381(9867):628. AlMazroa, Mohammad A [added]; Memish, Ziad A [added]]. Lancet 2012;380:2163–96. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61729-2.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

3. Steiner, TJ, Stovner, LJ, Katsarava, Z, Lainez, JM, Lampl, C, Lantéri-Minet, M, et al.. The impact of headache in Europe: principal results of the Eurolight project. J Headache Pain 2014;15:31. https://doi.org/10.1186/1129-2377-15-31.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

4. Castillo, J, Muñoz, P, Guitera, V, Pascual, J. Epidemiology of chronic daily headache in the general population. Headache 1999;39:190–6. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1526-4610.1999.3903190.x.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

5. Robbins, MS, Lipton, RB. The epidemiology of primary headache disorders. Semin Neurol 2010;30:107–19. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0030-1249220.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

6. Gaul, C, Finken, J, Biermann, J, Mostardt, S, Diener, HC, Müller, O, et al.. Treatment costs and indirect costs of cluster headache: a health economics analysis. Cephalalgia 2011;31:1664–72. https://doi.org/10.1177/0333102411425866.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

7. Wang, SJ, Wang, PJ, Fuh, JL, Peng, KP, Ng, K. Comparisons of disability, quality of life, and resource use between chronic and episodic migraineurs: a clinic-based study in Taiwan. Cephalalgia 2013;33:171–81. https://doi.org/10.1177/0333102412468668.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

8. Hu, XH, Markson, LE, Lipton, RB, Stewart, WF, Berger, ML. Burden of migraine in the United States: disability and economic costs. Arch Intern Med 1999;159:813–8. https://doi.org/10.1001/archinte.159.8.813.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

9. Mathers, CD, Bernard, C, Iburg, KM, Inoue, M, Fat, DM, Shibuya, K, et al.. The global burden of disease in 2002: data sources, methods and results. Global programme on evidence for health policy discussion paper no. 54, (revised 2004).Suche in Google Scholar

10. Linde, M, Gustavsson, A, Stovner, LJ, Steiner, TJ, Barré, J, Katsarava, Z, et al.. The cost of headache disorders in Europe: the Eurolight project. Eur J Neurol 2012;19:703–11. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-1331.2011.03612.x.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

11. Darbà, J, Marsà, A. Analysis of the management and costs of headache disorders in Spain during the period 2011–2016: a retrospective multicentre observational study. BMJ Open 2020;10:e034926. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2019-034926.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

12. Headache Classification Subcommittee of the International Headache Society. The international classification of headache disorders: 2nd edition. Cephalalgia 2004;24(1 Suppl):9–160.Suche in Google Scholar

13. Diener, HC, Holle, D, Solbach, K, Gaul, C. Medication-overuse headache: risk factors, pathophysiology and management. Nat Rev Neurol 2016;12:575–83. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrneurol.2016.124.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

14. Lionetto, L, Negro, A, Palmisani, S, Gentile, G, Fiore, MRD, Mercieri, M, et al.. Emerging treatment for chronic migraine and refractory chronic migraine. Expet Opin Emerg Drugs 2012;17:393–406. https://doi.org/10.1517/14728214.2012.709846.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

15. Black, DF, Dodick, DW. Two cases of medically and surgically intractable SUNCT: a reason for caution and an argument for a central mechanism. Cephalalgia 2002;22:201–4. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1468-2982.2002.00348.x.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

16. Donnet, A, Valade, D, Régis, J. Gamma knife treatment for refractory cluster headache: prospective open trial. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2005;76:218–21. https://doi.org/10.1136/jnnp.2004.041202.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

17. Jarrar, RG, Black, DF, Dodick, DW, Davis, DH. Outcome of trigeminal nerve section in the treatment of chronic cluster headache. Neurology 2003;60:1360–2. https://doi.org/10.1212/01.wnl.0000055902.23139.16.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

18. Matharu, MS, Goadsby, PJ. Persistence of attacks of cluster headache after trigeminal nerve root section. Brain 2002;125:976–84. https://doi.org/10.1093/brain/awf118.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

19. Wormald, JCR, Luck, J, Athwal, B, Muelhberger, T, Mosahebi, A. Surgical intervention for chronic migraine headache: a systematic review. JPRAS Open 2019;20:1–18. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpra.2019.01.002.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

20. Pedersen, JL, Barloese, M, Jensen, RH. Neurostimulation in cluster headache: a review of current progress. Cephalalgia 2013;33:1179–93. https://doi.org/10.1177/0333102413489040.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

21. Martelletti, P, Jensen, RH, Antal, A, Arcioni, R, Brighina, F, de Tommaso, M, et al.. Neuromodulation of chronic headaches: position statement from the European Headache Federation. J Headache Pain 2013;14:86. https://doi.org/10.1186/1129-2377-14-86.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

22. Schwedt, TJ, Dodick, DW, Hentz, J, Trentman, TL, Zimmerman, RS. Occipital nerve stimulation for chronic headache--long-term safety and efficacy. Cephalalgia 2007;27:153–7. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2982.2007.01272.x.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

23. Jasper, J, Hayek, S. Systematic review: implanted occipital nerve stimulators. Pain Physician 2008;11:187–200.10.36076/ppj.2008/11/187Suche in Google Scholar

24. Johnstone, CS, Sundaraj, R. Occipital nerve stimulation for the treatment of occipital neuralgia-eight case studies. Neuromodulation 2006;9:41–7. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1525-1403.2006.00041.x.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

25. Eldabe, S, Buchser, E, Duarte, RV. Complications of spinal cord stimulation and peripheral nerve stimulation techniques: a review of the literature. Pain Med 2016;17:325–36. https://doi.org/10.1093/pm/pnv025.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

26. Hayek, SM, Jasper, JF, Deer, TR, Narouze, SN. Occipital neurostimulation-induced muscle spasms: implications for lead placement. Pain Physician 2009;12:867–76.10.36076/ppj.2009/12/867Suche in Google Scholar

27. Zimmerman, RS, Rosenfeld, DM, Freeman, JA, Rebecca, AM, Trentman, TL. Revision of occipital nerve stimulator leads: technical note of two techniques. Neuromodulation 2012;15:387–91. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1525-1403.2011.00413.x.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

28. Shaw, A, Mohyeldin, A, Zibly, Z, Ikeda, D, Deogaonkar, M. Novel tunneling system for implantation of percutaneous nerve field stimulator electrodes: a technical note. Neuromodulation 2015;18:313–6. https://doi.org/10.1111/ner.12224.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

29. Zhou, L, Abad, M, Ashkenazi, A, Hud-Shakoor, ZR. Poster 264: occipital and supraorbital nerve stimulation for refractory cervicogenic headache – a comparative study. Pm&R 2010;2:S119. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pmrj.2010.07.298.Suche in Google Scholar

30. Rodrigo-Royo, MD, Azcona, JM, Quero, J, Lorente, MC, Acín, P, Azcona, J. Peripheral neurostimulation in the management of cervicogenic headache: four case reports. Neuromodulation 2005;8:241–8. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1525-1403.2005.00032.x.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

31. Kapural, L, Mekhail, N, Hayek, SM, Stanton-Hicks, M, Malak, O. Occipital nerve electrical stimulation via the midline approach and subcutaneous surgical leads for treatment of severe occipital neuralgia: a pilot study. Anesth Analg 2005;101:171–4. https://doi.org/10.1213/01.ane.0000156207.73396.8e.Suche in Google Scholar

32. Palmisani, S, Al-Kaisy, A, Arcioni, R, Smith, T, Negro, A, Lambru, G, et al.. A six year retrospective review of occipital nerve stimulation practice--controversies and challenges of an emerging technique for treating refractory headache syndromes. J Headache Pain 2013;14:67. https://doi.org/10.1186/1129-2377-14-67.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

33. Weiner, RL, Reed, KL. Peripheral neurostimulation for control of intractable occipital neuralgia. Neuromodulation 1999;2:217–21. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1525-1403.1999.00217.x.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

34. De Andres, J, Monsalve-Dolz, V, Fabregat-Cid, G, Villanueva-Perez, V, Harutyunyan, A, Asensio-Samper, JM, et al.. Prospective, randomized blind effect-on-outcome study of conventional vs. high-frequency spinal cord stimulation in patients with pain and disability due to failed back surgery syndrome. Pain Med 2017;18:2401–21. https://doi.org/10.1093/pm/pnx241.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

35. Kapural, L, Yu, C, Doust, MW, Gliner, BE, Vallejo, R, Sitzman, BT, et al.. Novel 10-kHz high-frequency therapy (HF10 therapy) is superior to traditional low-frequency spinal cord stimulation for the treatment of chronic back and leg pain: the SENZA-RCT randomized controlled trial. Anesthesiology 2015;123:851–60. https://doi.org/10.1097/aln.0000000000000774.Suche in Google Scholar

36. Thomson, SJ, Tavakkolizadeh, M, Love-Jones, S, Patel, NK, Gu, JW, Bains, A, et al.. Effects of rate on analgesia in kilohertz frequency spinal cord stimulation: results of the PROCO randomized controlled trial. Neuromodulation 2018;21:67–76. https://doi.org/10.1111/ner.12746.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

37. Deer, T, Slavin, KV, Amirdelfan, K, North, RB, Burton, AW, Yearwood, TL, et al.. Success using neuromodulation with BURST (SUNBURST) study: results from a prospective, randomized controlled trial using a novel burst waveform. Neuromodulation 2018;21:56–66. https://doi.org/10.1111/ner.12698.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

38. Schu, S, Slotty, PJ, Bara, G, von Knop, M, Edgar, D, Vesper, J. A prospective, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled study to examine the effectiveness of burst spinal cord stimulation patterns for the treatment of failed back surgery syndrome. Neuromodulation 2014;17:443–50. https://doi.org/10.1111/ner.12197.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

39. Trentman, TL, Zimmerman, RS. Occipital nerve stimulation: technical and surgical aspects of implantation. Headache 2008;48:319–27. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1526-4610.2007.01023.x.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

40. Craig, JAJr, Fisicaro, MD, Zhou, L. Revision of a superficially migrated percutaneous occipital nerve stimulator electrode using a minimally invasive technique. Neuromodulation 2009;12:250–3. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1525-1403.2009.00223.x.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

41. Gofeld, M. Anchoring of suboccipital lead: case report and technical note. Pain Pract 2004;4:307–9. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1533-2500.2004.04407.x.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

© 2020 Walter de Gruyter GmbH, Berlin/Boston

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Frontmatter

- Editorial

- Salami-slicing and duplicate publication: gatekeepers challenges

- Editorial Comment

- Risk for persistent post-delivery pain – increased by pre-pregnancy pain and depression. Similar to persistent post-surgical pain in general?

- Systematic Review

- Acute experimentally-induced pain replicates the distribution but not the quality or behaviour of clinical appendicular musculoskeletal pain. A systematic review

- Topical Review

- Unwillingly traumatizing: is there a psycho-traumatologic pathway from general surgery to postoperative maladaptation?

- Clinical Pain Research

- Translation, cross-cultural adaptation and psychometric evaluation of the Thai version of the fear-avoidance beliefs questionnaire in patients with non-specific neck pain

- Pain management in patients undergoing radiation therapy for head and neck cancer – a descriptive study

- Do intensity of pain alone or combined with pain duration best reflect clinical signs in the neck, shoulder and upper limb?

- Different pain variables could independently predict anxiety and depression in subjects with chronic musculoskeletal pain

- Symptoms of central sensitization in patients with inflammatory bowel diseases: a case-control study examining the role of musculoskeletal pain and psychological factors

- Acceptability of psychologically-based pain management and online delivery for people living with HIV and chronic neuropathic pain: a qualitative study

- Determinants of pain occurrence in dance teachers

- Observational Studies

- A retrospective observational study comparing somatosensory amplification in fibromyalgia, chronic pain, psychiatric disorders and healthy subjects

- Utilisation of pain counselling in osteopathic practice: secondary analysis of a nationally representative sample of Australian osteopaths

- Effectiveness of ESPITO analgesia in enhancing recovery in patients undergoing open radical cystectomy when compared to a contemporaneous cohort receiving standard analgesia: an observational study

- Shoulder patients in primary and specialist health care. A cross-sectional study

- The tolerance to stretch is linked with endogenous modulation of pain

- Pain sensitivity increases more in younger runners during an ultra-marathon

- Original Experimental

- DNA methylation changes in genes involved in inflammation and depression in fibromyalgia: a pilot study

- Participants with mild, moderate, or severe pain following total hip arthroplasty. A sub-study of the PANSAID trial on paracetamol and ibuprofen for postoperative pain treatment

- Exploring peoples’ lived experience of complex regional pain syndrome in Australia: a qualitative study

- Although tapentadol and oxycodone both increase colonic volume, tapentadol treatment resulted in softer stools and less constipation: a mechanistic study in healthy volunteers

- Educational Case Report

- Updated management of occipital nerve stimulator lead migration: case report of a technical challenge

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Frontmatter

- Editorial

- Salami-slicing and duplicate publication: gatekeepers challenges

- Editorial Comment

- Risk for persistent post-delivery pain – increased by pre-pregnancy pain and depression. Similar to persistent post-surgical pain in general?

- Systematic Review

- Acute experimentally-induced pain replicates the distribution but not the quality or behaviour of clinical appendicular musculoskeletal pain. A systematic review

- Topical Review

- Unwillingly traumatizing: is there a psycho-traumatologic pathway from general surgery to postoperative maladaptation?

- Clinical Pain Research

- Translation, cross-cultural adaptation and psychometric evaluation of the Thai version of the fear-avoidance beliefs questionnaire in patients with non-specific neck pain

- Pain management in patients undergoing radiation therapy for head and neck cancer – a descriptive study

- Do intensity of pain alone or combined with pain duration best reflect clinical signs in the neck, shoulder and upper limb?

- Different pain variables could independently predict anxiety and depression in subjects with chronic musculoskeletal pain

- Symptoms of central sensitization in patients with inflammatory bowel diseases: a case-control study examining the role of musculoskeletal pain and psychological factors

- Acceptability of psychologically-based pain management and online delivery for people living with HIV and chronic neuropathic pain: a qualitative study

- Determinants of pain occurrence in dance teachers

- Observational Studies

- A retrospective observational study comparing somatosensory amplification in fibromyalgia, chronic pain, psychiatric disorders and healthy subjects

- Utilisation of pain counselling in osteopathic practice: secondary analysis of a nationally representative sample of Australian osteopaths

- Effectiveness of ESPITO analgesia in enhancing recovery in patients undergoing open radical cystectomy when compared to a contemporaneous cohort receiving standard analgesia: an observational study

- Shoulder patients in primary and specialist health care. A cross-sectional study

- The tolerance to stretch is linked with endogenous modulation of pain

- Pain sensitivity increases more in younger runners during an ultra-marathon

- Original Experimental

- DNA methylation changes in genes involved in inflammation and depression in fibromyalgia: a pilot study

- Participants with mild, moderate, or severe pain following total hip arthroplasty. A sub-study of the PANSAID trial on paracetamol and ibuprofen for postoperative pain treatment

- Exploring peoples’ lived experience of complex regional pain syndrome in Australia: a qualitative study

- Although tapentadol and oxycodone both increase colonic volume, tapentadol treatment resulted in softer stools and less constipation: a mechanistic study in healthy volunteers

- Educational Case Report

- Updated management of occipital nerve stimulator lead migration: case report of a technical challenge