Abstract

Objectives

In evidence-based medicine, we base our conclusions on the effectiveness of interventions on the results of high-quality meta-analysis. If a new randomized controlled trial (RCT) is unlikely to change the pooled effect estimate, conducting the new trial is a waste of resources. We evaluated whether recommendations not to conduct further RCTs reduced the number of trials registered for two scenarios.

Methods

Analysis of registered trials on the World Health Organisation (WHO) International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (ICTRP). We regarded trial protocols relevant if they evaluated the effectiveness of (1) exercise for chronic low back pain (LBP) and (2) cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) for chronic pain. We calculated absolute and relative numbers and change of registered trials in a pre-set time window before and after publication of the recommendations, both published in 2012.

Results

We found 1,574 trials registered in the WHO trial registry for exercise in LBP (459 before 2012; 1,115 after) and 5,037 trials on chronic pain (1,564 before 2012; 3,473 after). Before 2012, 13 trials on exercise for LBP (out of 459) fit the selection criteria, compared to 42 trials (out of 1,115) after, which represents a relative increase of 33%. Twelve trials (out of 1,564) regarding CBT for chronic pain, fit the selection criteria before 2012 and 18 trials (out of 3,473) after, representing a relative decrease of 32%. We found that visibility, media exposure and strength of the recommendation were related to a decrease in registered trials.

Conclusions

Recommendations not to conduct further RCTs might reduce the number of trials registered if these recommendations are strongly worded and combined with social media attention.

Introduction

In evidence-based medicine the choice of a treatment is based on patient preferences, scientific evidence and clinical expertise. The scientific evidence on the effectiveness of an intervention is determined when a meta-analysis of high-quality trials demonstrates a statistically significant and clinically worthwhile effect [1]. Until such evidence exists, researchers may claim that a new randomized controlled trial (RCT) is justified. Unfortunately, often the decision to justify another trial is made without consideration of how the findings of a new trial would alter the clinical recommendations for an intervention based on the existing evidence [2]. A trial that is unlikely to alter clinical recommendations is unnecessary and constitutes research waste [3]. Therefore, the need for replication of research should be balanced with the avoidance of mere repetition, even if the underlying mechanisms of effect are not (fully) understood [4]. In addition, the GRADE approach states that when there is high-quality evidence of an effect estimate then “further evidence is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect” [3], [5].

Recently, recommendations have been made that a new trial is not necessary in situations when we either know the intervention is, or is not, effective, and there is evidence that new data will not change the clinical recommendation for the use of the intervention [6], [7]. These studies concern recommendations of main interventions in the field of physiotherapy and psychology of: (1) Exercise compared to minimal intervention to reduce pain in people with chronic low back pain (LBP) [6]; or (2) Cognitive Behavioural Therapy (CBT) compared to simple alternatives to reduce disability in people with chronic pain [7].

Therefore, the aim of this study is to determine whether recommendations not to conduct further trials changed the number of registered trials intending to evaluate the above-mentioned research questions. Our secondary aim was to assess whether any change in the number of registered trials was related to trial-specific factors (such as country or origin, sample size, participant condition) or publication factors, such as the journal impact factor or strength of the recommendation.

Methods

Design

We analysed the number of trials registered on the World Health Organisation (WHO) International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (ICTRP) as this is the most complete trial registry, in 4-years’ time windows before and after the recommendation not to conduct further trials.

Selection criteria

We used the same selection criteria as the two papers that recommended not to conduct further trials (Appendix 1) [6], [7]. For the first recommendation registered trial protocols were included if they met the following criteria: (1) RCT comparing at least two interventions; (2) participants with chronic LBP (≥3 months) randomly allocated to either exercise or a control group of no or minimal intervention; and (3) measured pain or disability as an outcome. For the second recommendation, registered trial protocols were included if they met the following criteria: (1) RCT comparing at least two interventions; (2) participants with chronic pain (≥3 months) that were randomly allocated to CBT or a control group of no intervention or a non-psychotherapy alternative intervention; and (3) measured pain or disability as an outcome.

Trials evaluating psychological treatments with a component of CBT were included, e.g. internet-based CBT, acceptance and commitment therapy (ACT) and other modifications of CBT, both individual as group-based. We excluded physiotherapy as a control arm, assuming that this would be an active intervention.

Search strategy

We searched the WHO-ICTRP (http://apps.who.int/trialsearch/) for trial protocols using the selection criteria. The papers that made the recommendations were published in 2012. Therefore, we searched for trials registered in an a priori set period of 4 years between 1st January 2008 and 31st December 2011 and for trials registered between 1st January 2015 and 31st December 2018. The a priori set period after the recommendation was chosen based on the idea that researchers should have been able to read the recommendation prior to planning and conducting a RCT.

We were unable to use “exercise” or “CBT” as search terms to limit the yield (Appendix 2) and therefore the yield in CBT for chronic pain was much larger than in exercise for LBP. To ensure we had comparable numbers we decided to limit the period for CBT to 2-year periods (1st January 2009 and 31st December 2010 and between 1st January 2016 and 31st December 2017).

Screening

Two authors independently screened all titles and abstracts for relevance (IS and LvR), and a third author (AV) resolved the conflicts. We extracted the data from the registry, and in case of uncertainty, we checked the original registration and all available (published) data. In addition, the third assessor performed a 10% random check of all titles and abstracts from the original registration.

Data extraction

Data were extracted on: (1) the number of trials registered that evaluated exercise/CBT compared to no intervention in patients with LBP and chronic pain, and absolute numbers of registered trials on LBP and chronic pain in the trial registry; (2) trial-specific factors (e.g. condition, setting, country, sample size, ethical approval and granting body [last check August 2019]); and (3) factors related to the publication (e.g. journal of publication [impact factor], strength of recommendation, Altmetrics score, keywords used). The Altmetrics score, literally “alternative metrics”, measures and monitors the reach and impact of research publications through online interactions, next to the traditional measurements of academic success such as citation counts, impact factor, and author H-index (www.altmetrics.com). While the Almetric score does not measure how many times a particular article is read it does provide an indication of the extent of the readership.

Data synthesis

First, we calculated frequencies of the absolute and relative numbers of included trial protocols before and after 2012 both for exercise in LBP and for CBT in chronic pain. We calculated the relative number by dividing the number of trials that met our selection criteria (included trials) by the total number of trials that evaluated exercise/CBT in patients with LBP/chronic pain in the trial registry during the search period. Next, the relative risk ratio, absolute change and relative change were calculated. For our primary aim, we decided a priori that we consider a change in the number of trials registered that was a relative positive or negative change, when this change was >10%. If the relative change was between −10 and 10% we would consider this as no change.

Results

Search

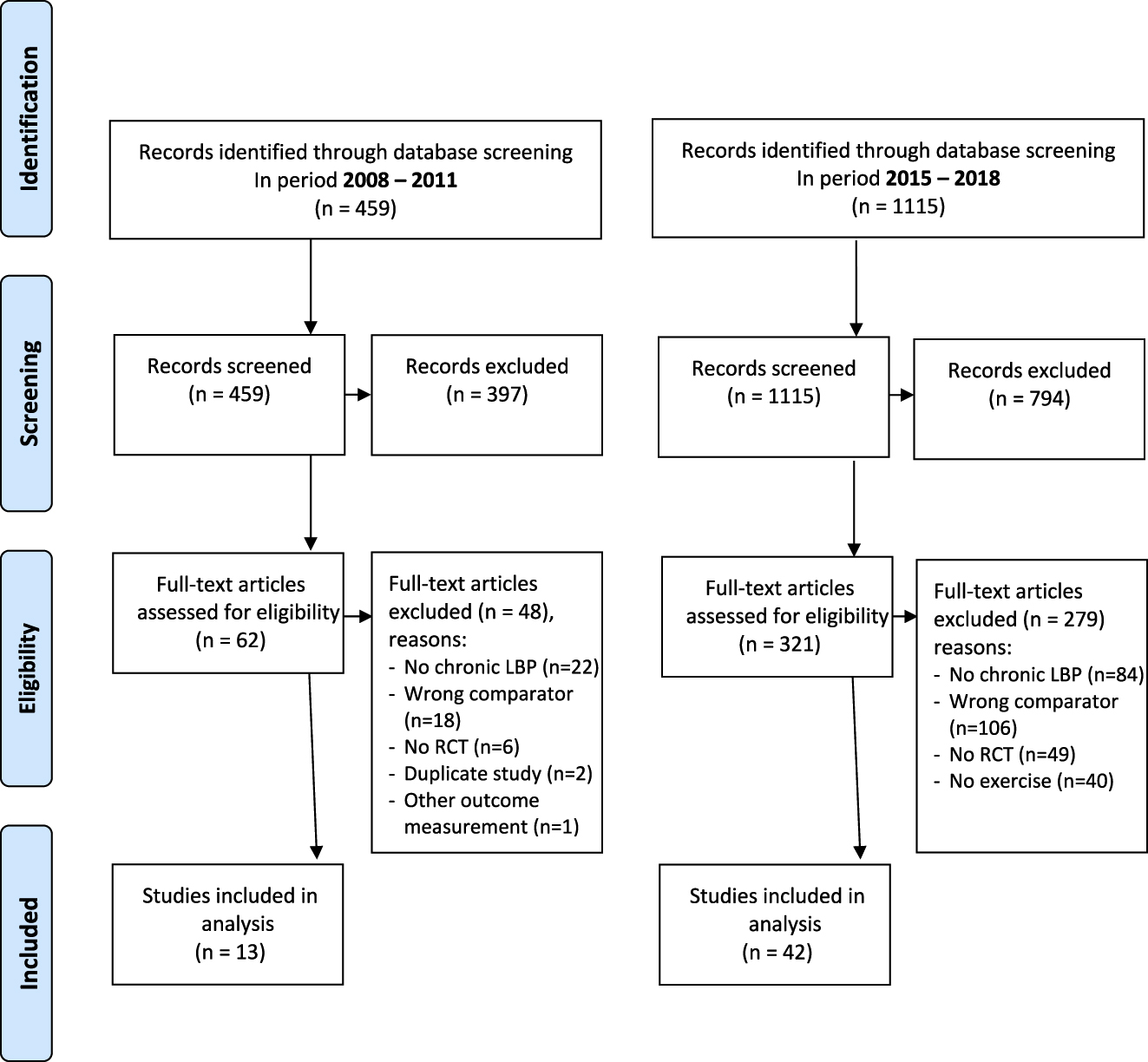

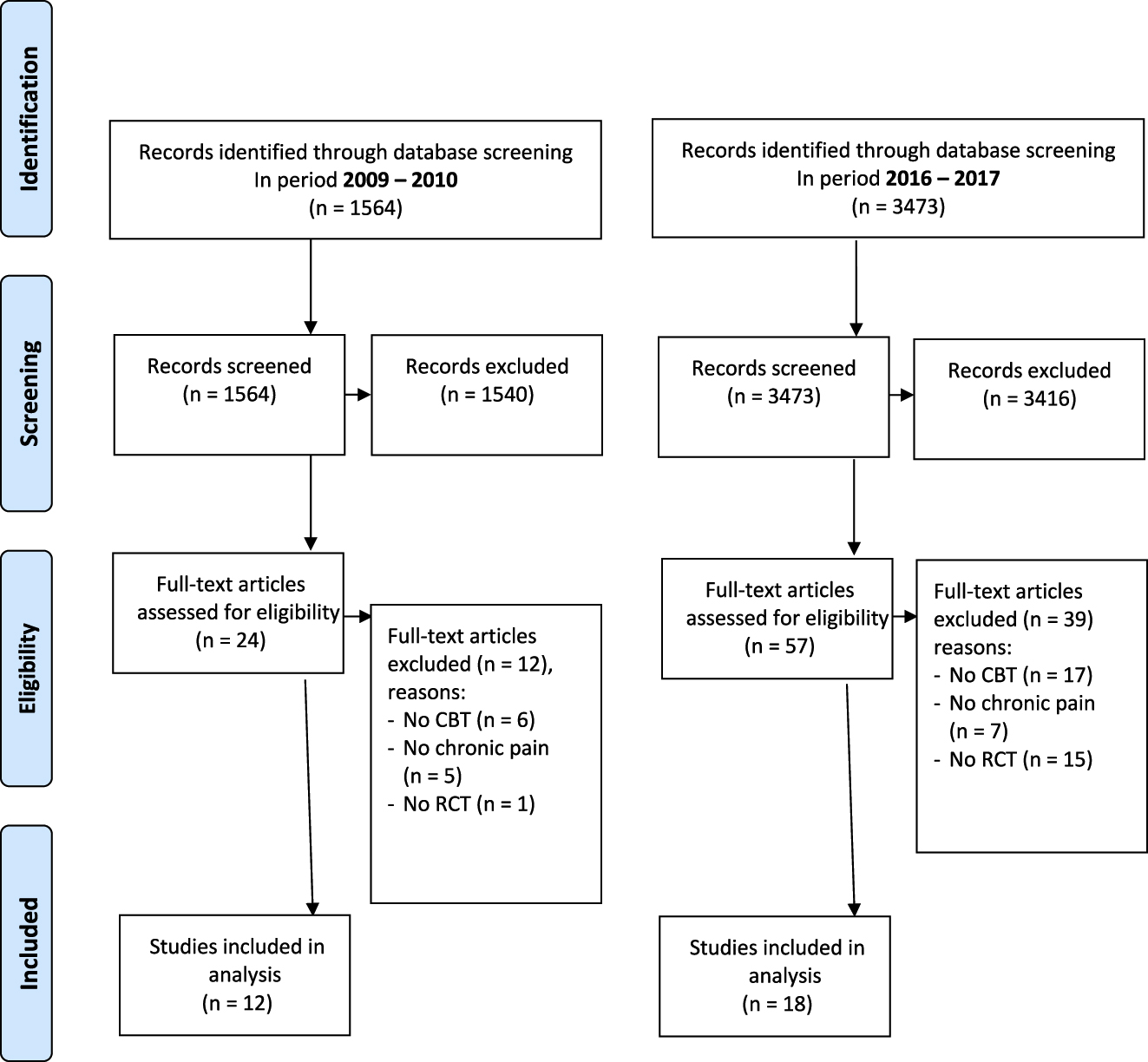

There were in total 1,574 trials registered for exercise in LBP: 459 before 2012 and 1,115 after (Figure 1) and 5,037 trials on chronic pain: 1,564 before 2012 and 3,473 after (Figure 2). There was a 90.7% agreement between the two authors in the selection of included trials. We present all trial-specific factors in Appendix 3.

PRISMA flowchart for trials evaluating exercise for low back pain (LBP) in period 2008–2011 (pre-recommendation) and 2015–2018 (post-recommendation).

PRISMA flowchart for trials evaluating cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) for chronic pain in period 2009–2010 (pre-recommendation) and 2016–2017 (post-recommendation).

Impact of recommendations

Exercise for LBP

We found an increase in the number of registered trials of exercise for LBP before and after 2012 of 33%; from 13 trials out of 459 (2.83%) to 42 trials out of 1,115 (3.77%) (Table 1).

Differences before and after recommendations.

| Total | Pre | Post | Relative risk ratio | Absolute change (%) | Relative change (%) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Included | Registered | Included | Registered | |||||

| Exercise for LBP | 1,574 | 13 | 459 | 42 | 1,115 | (3.77–2.83)/(3.77)=0.33 | +0.94 | +33 |

| CBT for chronic pain | 5,037 | 12 | 1,564 | 18 | 3,473 | 0.52–0.77)/(0.52)=−0.32 | −0.25 | −32 |

CBT for chronic pain

We found a decrease in the number of registered trials of CBT for chronic pain before and after 2012 of 32%; from 12 out of the 1,564 (0.77%) trials to 18 out of 3,473 trials (0.52%) (Table 1).

Characteristics of included trials

Exercise for LBP

Out of 1,574 trials we found 13 that evaluated exercise compared to a control condition in the period of 2008–2011 and 42 in the period of 2015–2018 (Appendix 3). Participants in the control condition received treatment as usual (n=11), education (n=10) or no intervention/waiting list (n=20). The majority of the trials (n=35, 63%) recruited participants in a primary care setting with a mean sample size of 94 participants (range 20–600). After 2012, the mean sample size declined, from 115 to 89 participants and trials were less likely to be registered in a first world country (Europe, USA or Australia). More than half of all trials (n=30) mentioned ethical approval, in other cases it was either unclear (n=21) or not obtained (n=4). The government funded most trials, except for seven trials (12.5%). Trials registered before 2012, six out of 13 trials (46.2%) published their results in a journal (with impact factors ranging from 0.22 up to 19.36 by August 2019).

CBT for chronic pain

Out of 5,037 trials we found 12 that evaluated a modality of CBT in the period of 2009–2010 and 18 in the period of 2016–2017 (Appendix 3). The control arm consisted of education (n=11), a waiting list group (n=10) or treatment as usual (n=9). Most trials were offered in a hospital setting (n=22, 73%) with a mean sample size of 127 participants (range 28–400). After 2012, the mean sample size increased from 101 to 145 participants. Ethical approval was obtained for 14 trials (47%), and unclear for 16 (53%). Trials were primarily funded by the government (n=16), or by a charity or industry. Nine out of 12 trials registered before 2012 (75%) published their results in a journal (with impact factors ranging from 2.01 to 4.52).

Specific factors related to the recommendation

Exercise for LBP

The recommendation was as follows: “…a new trial, even a large trial, would not resolve the uncertainty about whether the effects are large enough to be worthwhile.” [6]. We classified this as a weak recommendation. The study was published in the BMJ (impact factor of 27.6) in 2012. This paper has an Altmetrics score of 21, based on 30 citations and media exposure on three different forums (half of the impact is from tweets [last updated March 3rd 2020]). In addition, as this paper was a research methods paper, not a ‘recommendations on stopping exercise trials’ paper, this paper did not use keywords which might have influenced the visibility of this paper in any data source.

CBT for chronic pain

The recommendation was: “We recommend the immediate cessation of new trials of CBT against simple alternatives”. [7]. We classified this recommendation as strong. It was published in the Cochrane database of systematic reviews which has an impact factor of 7.75. This paper has an Altmetrics score of 110, based on 586 citations and media exposure on six different forums (last updated March 3rd 2020).

Discussion

Main findings

We found a marked reduction in clinical trials of CBT for chronic pain, but a marked increase in clinical trials of exercise for LBP, following clear recommendations that neither intervention required further investigation. Our data demonstrated that researchers can, but don’t always, follow recommendations from other researchers as regards the value of conducting further RCTs.

The increase in the number of LBP trials registered may not have been influenced by the publication of this recommendation. The publication itself did not have a clear statement on exercise in LBP in the title or abstract, and there were no keywords provided [6]. Although it was published in a relatively high impact journal, it did not result in much media exposure (Altmetrics score). Also, an overview of Cochrane reviews on exercise in adults with chronic pain stated that further research is needed [13]. Although this overview was not specifically targeted at LBP, just three out of 21 included reviews were on LBP, and conclusions were not specific for LBP either, it could have influenced the increase in exercise for LBP protocols.

By contrast, the chronic pain recommendation in the Cochrane review (also a high impact journal) had a firmer recommendation, was easier to find due to the inclusion of keywords, and had a higher Altmetrics score [7]. The Altmetrics score could be a more realistic reflection of the attention of research output and its impact on researchers (and their plans to conduct new trials) than journal impact. It shows that research may have more impact, if it is available, accessible and has a clear message. We conclude that the difference in adherence to the recommendation between exercise for LBP and CBT for chronic pain was not related to the impact factor of the journal in which the recommendation was published, but probably more related to the strength of the recommendation, the visibility (i.e. Altmetrics score) of the paper and probably also to the use of keywords.

Strengths and limitations

This study is the first study to investigate the impact of recommendations not to conduct further trials on the registration of new trials. It identifies specific factors related to the impact of the recommendations.

This study nevertheless has some limitations. It was difficult to search the WHO-ICTRP, which might be a result of the format of the search boxes in the trial register. The search parameters were restrictive making it difficult to conduct an extensive search, but this influenced both searches equally.

The wording of the recommendations differs between studies. As for exercise in LBP it was not really a “recommendation”, which might explain why it had less impact than a “clear” recommendation stated in the conclusion of a Cochrane systematic review.

In addition, we had trouble extracting data from the trial protocols, as protocols were often incomplete, and provided unclear descriptions of the intervention and control conditions. To make sure we did not miss any relevant protocols, we searched for the full text for final selection. This shows again the importance of a high-quality protocols addressing the study methodology in full, particularly a clear description of the intervention [8]. Studies of published trial reports showed that the poor description of interventions meant that 40–89% were non-replicable and hence increase research waste [9]. Therefore, authors are advised to follow a standardized format (e.g. SPIRIT statement), regularly update the trial protocol, and report all results. Almost half of the studies on LBP before 2012 published their results. This is in line with a recent European study that showed that half of all trials are non-compliant with reporting results to the EU Clinical trials register [10]. This is comparable to another study that found that half of all non-registered studies are not published [11]. In addition, the current study investigated only one domain of science-allied health interventions for chronic pain. We cannot be certain that the same pattern would emerge in other domains of science such as RCTs on medications. We do feel however that the recommendations below are applicable to all domains and research areas.

Recommendations

To reduce research waste and increase research impact, researchers should have a clear message to other researchers. In addition, one may consider a targeted media campaign to address policy makers, funding bodies and society. Researchers should be encouraged to thoroughly research the available, published and unpublished literature before designing a new trial [12]. When a meta-analysis of existing trials does not provide clear findings about whether an intervention has worthwhile effects, extended funnel plots can be used to explore the potential impact of a new trial on the updated meta-analysis and chance of changing clinical recommendations [6]. It is hoped that the use of living systematic reviews will help to inform researchers when a clinical question has been adequately addressed and further deter researchers from planning and conducting RCTS that do add to the overall existing evidence. We acknowledge that the current research landscape encourages and rewards early career researchers, including PhD candidates, who have conducted RCTs. An investigation into the rationale, not only for early career researchers but all researchers, for conducting RCTs would assist in understanding how to ensure only necessary RCTs are conducted. We encourage researchers and policymakers to actively spread and follow recommendations to increase their impact and to reduce research waste. Also funding bodies and ethical committees should take some responsibility for this, especially in a competitive research environment.

Conclusion

We found a marked reduction in protocols of CBT for chronic pain, but a marked increase in protocols of exercise for LBP, following clear recommendations that neither intervention required further investigation. This study shows that strong recommendations, visibility and media exposure may be relevant.

Acknowledgments

Amanda Williams, for her help with the manuscript and Stephanie Rizoski, Monique Williams and Samuel Leslie for helping with the data extraction.

-

Research funding: The authors state they did not receive any funding for this study.

-

Author contributions: All authors have accepted responsibility for the entire content of this manuscript and approved its submission.

-

Competing interest: The authors state they all have no conflicts of interest.

-

Informed consent: Not applicable as no patients are involved.

-

Ethical approval: Not applicable as no patients are involved.

Appendix 1: Definitions of selection criteria for trial protocols

Exercise for LBP:

P atients with chronic nonspecific low back pain, defined as a nonspecific episode of low back pain (with or without leg pain) lasting for 12 weeks or longer.

I ntervention: exercise therapy that included the performance of any physical activity in order to develop the body (or part of the body) and improve health.

C ontrol intervention included no intervention or a waiting list or a minimal (passive) intervention such as laser therapy, education or massage therapy.

O utcome: pain, disability, quality of life

Cognitive Behavioural Therapy for chronic pain:

P atients with chronic pain, defined as more than 3 months of pain irrespective of the cause.

I ntervention: cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT), that included psychological treatments with a component of CBT, e.g. internet-based CBT, acceptance and commitment therapy (ACT) and other modifications of CBT, both individual as group-based.

C ontrol intervention: a simple alternative that included no intervention, waiting list or a minimal (non-psychotherapy) intervention such as exercise, education, or standard care.

O utcome: pain, disability, quality of life (return to work)

Appendix 2: Search strategy

Advanced search of the WHO International Clinical Trials Registry Platform

Search 1:

Box 1: Left black (Search terms entered in Box 1 search the title of the protocol)

Box 1: Condition/Participants (without synonyms boxed left unticked) – “low back pain”*

Box 2: Intervention (without synonyms boxed left unticked) – Left blank

Search for clinical trials in children: Box not ticked

Recruitment status is: “ALL”

Primary Sponsor is: Leave blank

Secondary ID: Leave blank

Countries of Recruitment: Leave blank – all countries searched.

Date of Registration is between: “01/01/2008” and “31/12/2011”

Phases are: “ALL”

With results only: Box not ticked

Search 2:

Box 1: Left black (Search terms entered in Box 1 search the title of the protocol)

Box 1: Condition / Participants (without synonyms boxed left unticked) – “low back pain”*

Box 2: Intervention (without synonyms boxed left unticked) – Left blank

Search for clinical trials in children: Box not ticked

Recruitment status is: “ALL”

Primary Sponsor is: Leave blank

Secondary ID: leave blank

Countries of Recruitment: Leave blank – all countries searched.

Date of Registration is between: “01/01/2015” and “31/12/2018”

Phases are: “ALL”

With results only: Box not ticked

Search 3:

Box 1: Left black (Search terms entered in Box 1 search the title of the protocol).

Box 1: Condition/ Participants (without synonyms boxed left unticked) – chronic pain

Box 2: Intervention (without synonyms boxed left unticked) – Left blank

Search for clinical trials in children: Box not ticked

Recruitment status is: “ALL”

Primary Sponsor is: Leave blank

Secondary ID: leave blank

Countries of Recruitment: Leave blank – all countries searched.

Date of Registration is between: “01/01/2009” and “31/12/2010”

Phases are: “ALL”

With results only: Box not ticked

Search 4:

Box 1: Left black (Search terms entered in Box 1 search the title of the protocol)

Box 1: Condition/Participants (without synonyms boxed left unticked) – chronic pain

Box 2: Intervention (without synonyms boxed left unticked) – Left blank

“Search for clinical trials in children”: Box not ticked

Recruitment status is: “ALL”

Primary Sponsor is: Leave blank

Secondary ID: leave blank

Countries of Recruitment: Leave blank- all countries searched.

Date of Registration is between: “01/01/2016” and “31/12/2017”

Phases are: “ALL”

With results only: Box not ticked

*The WHO International Clinical Trials Registry Platform automatically searches synonyms generated using the UMLS Metathesaurus.

The following terms for low back pain will also therefore be included:

Low back pain synonyms:

“- ACHE, LOW BACK, ACHES, LOW BACK, BACK ACHE, LOW, BACK ACHES, LOW, BACK PAIN, BACK PAIN LOWER BACK, BACK PAIN LUMBAR, BACK PAIN, LOW, BACK PAIN, LOWER, BACK PAINS, LOW, BACK PAINS, LOWER, BACK; PAIN, LOW, BACKACHE, LOW, BACKACHE; LOW, BACKACHES, LOW, LBP, LOW BACK ACHE, LOW BACK ACHES, LOW BACK DERANGEMENT SYNDROME, LOW BACK SYNDROME, LOW BACK; PAIN, LOW BACKACHE, LOW BACKACHES, LOW; BACKACHE, LOWER BACK PAIN, LOWER BACK PAINS, LOWER BACKACHE, LOWER BACKACHE (DIAGNOSIS), LUMBAGO, LUMBAGO (DIAGNOSIS), LUMBAGO NOS, LUMBALGIA, LUMBAR BACK PAIN, LUMBAR PAIN, NONSPECIFIC PAIN LUMBAR REGION, PAIN, LOW BACK, PAIN, LOWER BACK, PAIN; BACK, LOW, PAIN; LOW BACK, PAIN;BACK LOW, PAIN; BACK; LUMBAR, PAINS, LOW BACK, PAINS, LOWER BACK, SPONDYLOSIS; INTERVERTEBRAL DISC DISORDERS; OTHER BACK PROBLEMS, SYNDROME; LOW BACK, low back pain”.

Chronic Pain Synonyms:

–CHRONIC; PAIN, PAIN, PAIN CHRONIC, PAIN, CHRONIC, PAIN; CHRONIC, PAIN; CHRONIC, PAINS, CHRONIC, chronic pain

Trials registered (n=13) between 2008 and 2011 on the effectiveness of exercise vs. no or minimal intervention in chronic low back pain patients.

| Year | Setting (sample size) | Intervention | Control | Ethical approval | Granting body* | Published results | Impact factor# |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2008 | Primary care, Australia (160) | Tai chi, twice weekly for 8 weeks | No treatment | Yes | Gov | Yes | 4.149 |

| 2008 | Primary care, Brazil (119) | Back school (incl. exercises) | Weekly lectures | Unclear | Gov | No | |

| 2009 | Hospital, UK (50) | Pedometer driven walking program given by a physiotherapist | Single education session + back book | Yes | Other (physio foundation) | Yes | 2.454 |

| 2009 | Primary care, USA (30) | Hatha yoga | Treatment as usual | Unclear | Gov | No | |

| 2009 | Unclear, Spain (60) | Progressive whole-body vibration | Treatment as usual | Yes | Gov | No | |

| 2010 | Primary care, USA (72) | Total body resistance exercise program | Standard care | Yes | Gov | Yes | 0.22 |

| 2011 | Unclear, Brazil (44) | Physiotherapy exercises | Exercise booklet | Unclear | Gov | No | |

| 2010 | Primary care, Germany (299) | IRENA (intensive rehabilitation program incl. exercises) | Educational booklet | Unclear | Gov | No | |

| 2010 | Primary care, Japan (150) | Water-exercise group and booklet | No treatment | Unclear | Gov | No | |

| 2010 | Primary care, Iran (36) | Core stability exercises | Waiting list | Yes | Gov | Yes | 0.82 |

| 2011 | Primary care, USA (320) | Physical therapy | Back pain help book | Yes | Gov | Yes | 19.384 |

| 2011 | Hospital, Germany (176) | Yoga | No intervention** | Yes | Gov | Yes | 4.519 |

| 2011 | Primary care Germany (40) | Whole vibration training | No treatment | Yes | Other (pension insurance) | No |

-

*Industry, governmental (Gov), other.

-

**5-year impact factor, if not available impact factor of 2018.

-

#In trial register there is only 1 control group (Qigong), in the publication there is also a no intervention group.

Trials registered (n=12) between 2009 and 2010 on the effectiveness of CBT vs. no or minimal treatment in chronic pain patients.

| Year | Setting (sample size) | Intervention | Control | Ethicalapproval | Granting body* | Published results | Impact factor |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2009 | Hospital, Netherlands (50) | Internet CBT | Waiting list | Yes | Other (health insurance) | Yes | 4.519 |

| 2009 | Hospital, USA (86) | Patient-controlled CBT | Waiting list | Yes | Gov | Yes | 3.249 |

| 2009 | Hospital, Norway (234) | CBT | Waiting list | Yes | Gov | Yes, part of the trial | 2.699 |

| 2009 | Hospital, USA (48) | Internet CBT (also for headache) | Waiting list | Yes | Gov | Yes | 3.189 |

| 2009 | Hospital, USA (47) | CBT | Education | Unclear | Other (VA Connecticut healthcare system) | No | |

| 2009 | Hospital, Germany (28) | CBT-PMP | Waiting list | Yes | Gov | Yes | 2.012 |

| 2009 | Hospital, Switserland (120) | CBT | Physiotherapy | Yes | Other (rehabilitation foundation) | Yes | 2.012 |

| 2010 | Primary care, USA (41) | Telephone CBT | Telephone pain education | Unclear | Gov | No | |

| 2010 | Hospital, Canada (48) | CBT self-help manual / approach for insomnia | Sleep diary | Unclear | Gov | No | |

| 2010 | Primary care, USA (367) | CBT for pain | Osteoarthritis education | Yes | Gov | Yes | 4.519 |

| 2010 | Hospital, Ireland (50) | CBT-PMP | Waiting list | Yes | Industry | Yes | 2.454 |

| 2010 | Hospital, UK (92) | Contextual CBT | Back to fitness class | Yes | Other (charity) | Yes | 2.012 |

-

*Industry, governmental (Gov), other.

Trials registered (n=42) between 2015 and 2018 on the effectiveness of exercise vs. no or minimal treatment in chronic low back pain patients.

| Year | Setting (sample size) | Intervention | Control | Ethical approval | Granting body* |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2015 | Primary care, USA (40) | Yoga | Back pain helpbook | Unclear | Governmental |

| 2015 | Primary care, USA (152) | Yoga | Treatment as usual | Unclear | Governmental |

| 2015 | Primary care, Brazil (40) | Physical therapy | Osteopathic manipulation | Yes | Governmental |

| 2015 | Primary care, Iran (60) | Exercise | Education | Yes | Governmental |

| 2015 | Hospital, Australia (92) | Mind-body exercises | Treatment as usual | Yes | Governmental |

| 2015 | Hospital, Australia (60) | Exercise program wii | Treatment as usual | Yes | Governmental |

| 2015 | Primary care, Italy (96) | Exercise rehabilitation program | Waiting list | No | Other (self-funded) |

| 2016 | Hospital care, Thailand (72) | Qigong | Waiting list | Unclear | Governmental |

| 2016 | Unclear, Brazil (30) | Pilates | No intervention | Unclear | Governmental |

| 2016 | Unclear, Japan (46) | Exercise | Thermotherapy | Yes | Other(Self-funded) |

| 2016 | Primary care, Iran (20) | Exercises | No treatment | Yes | Governmental |

| 2016 | Hospital, China (108) | Taijiquan exercise | NSAIDs | No | Governmental |

| 2017 | Unclear, Brazil (26) | Pilates | No treatment | Yes | Governmental |

| 2017 | Primary care, USA (57) | Tai chi | Education | Unclear | Other (NGO) |

| 2017 | Primary care, Spain/Denmark (85) | Strength training | Treatment as usual | Unclear | Governmental |

| 2017 | Primary care, Spain (38) | Physiotherapy | Treatment as usual by GP | Unclear | Governmental |

| 2017 | Unclear, Brazil (90) | Exercise | Electroanalgesia | Unclear | Governmental |

| 2017 | Primary care, Nigeria (120) | Motor control exercise | Education | Unclear | Governmental |

| 2017 | Primary care, Brazil (84) | Exercise | Analgesia | Unclear | Governmental |

| 2017 | Hospital, USA (42) | Exercise & meditation | Listen to audio book | Unclear | Governmental |

| 2017 | Primary care, USA (40) | Exercise program | Waiting list | Unclear | Governmental |

| 2017 | Primary care, Sweden (600) | Physiotherapy | Booklet | Yes | Governmental |

| 2017 | Primary care, Iran (45) | Suspension exercises | No treatment | Yes | Governmental |

| 2017 | Primary care, Iran (64) | Back school program, including information establishing and maintaining correct posture and exercises for stability | No treatment | Yes | Governmental |

| 2017 | Hospital, China (178) | Baduanjin qigong | Treatment as usual | Yes | Governmental |

| 2017 | Hospital, China (136) | Rehabilitation exercise training | No treatment | No | Governmental |

| 2017 | Hospital, Australia (346) | Physiotherapy and coaching | Treatment as usual | Yes | Governmental |

| 2018 | Primary care, Japan (20) | Exercise | Waiting list | Unclear | Governmental |

| 2018 | Primary care, Brazil (60) | Pilates | No treatment | Yes | Governmental |

| 2018 | Primary care, Brazil (30) | Aerobic exercise | Shockwave | Unclear | Governmental |

| 2018 | Primary care, USA (70) | Exercise | Waiting list | Unclear | Governmental |

| 2018 | Primary care, Nigeria (30) | Motor control exercise | Education | Unclear | Governmental |

| 2018 | Primary care, Australia (80) | Green exercise | No treatment | Yes | Governmental (EU) |

| 2018 | Primary care, Iran (75) | Exercise | Education | Yes | Governmental |

| 2018 | Hospital, Iran (72) | Exercise | No treatment | Yes | Governmental |

| 2018 | Primary care, Iran (30) | Pilates | No treatment | Yes | Governmental |

| 2018 | Primary care, India (96) | Yoga | Treatment as usual | Yes | Governmental |

| 2018 | Primary care, India (90) | Exercises | Education | Yes | Governmental |

| 2018 | Primary care, India (20) | Physiotherapy | Ayurvedic classical herbal formulation | Yes | Other (private) |

| 2018 | Hospital, China (100) | Aquatic exercise | Physical agents | Yes | Governmental |

| 2018 | Hospital. China (76) | Hip bone balance exercise | Massage | No | Other (self-funded) |

| 2018 | Hospital, Australia (32) | Resistance exercise program | Treatment as usual | Yes | Governmental |

-

*Industry, governmental, other.

Trials registered (n=18) between 2016 and 2017 on the effectiveness of CBT vs. no or minimal treatment in chronic pain patients.

| Year | Setting | Intervention | Control | Ethical approval | Granting body* |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2016 | Hospital, Germany (54) | CBT | Treatment as usual | Yes | Other (PRANA foundation) |

| 2016 | Hospital, Sweden (91) | CBT | Waiting list | Unclear | Governmental |

| 2016 | Hospital, USA (60) | Online self-management program based on cognitive behavioural principles | Treatment as usual | Unclear | Governmental |

| 2016 | Hospital, Norway (120) | ACT | Treatment by GP | Yes | Governmental |

| 2016 | Primary care, Iran (30) | CBT | No treatment | Yes | Governmental |

| 2016 | Primary care, China (150) | CBT | Education | Yes | Other (charity) |

| 2017 | Hospital, USA (420) | CBT | Coping skills training and physical exercise program | Unclear | Governmental |

| 2017 | Primary care, Ireland (70) | CBT | Treatment as usual | Unclear | Other (person, charity) |

| 2017 | Hospital, USA (139) | CBT | Treatment as usual | Unclear | Governmental |

| 2017 | Unclear, Nigeria (37) | CBT | Exercise | Yes | Governmental |

| 2017 | Unclear, Cyprus (150) | ACT | Psycho-education | Unclear | Governmental |

| 2017 | Primary care, Sweden (400) | ACT | No treatment | Unclear | Governmental |

| 2017 | Hospital, Sweden (200) | Internet CBT | Waiting list | Unclear | Governmental |

| 2017 | Hospital, USA (231) | CBT | Health education | Unclear | Governmental |

| 2017 | Hospital, Sweden (113) | Internet ACT | Waiting list | Unclear | Other (AFA insurance) |

| 2017 | Hospital, Ireland (160) | ACT + exercise | Exercise | Unclear | Governmental |

| 2017 | Hospital, USA (40) | CBT | Education | Unclear | Governmental |

| 2017 | Hospital, USA (143) | Internet CBT | Treatment as usual | Unclear | Governmental |

-

*Industry, governmental, other.

References

1. Burns, PB, Rohrich, RJ, Chung, KC. The levels of evidence and their role in evidence-based medicine. Plast Reconstr Surg 2011;128:305–10. https://doi.org/10.1097/prs.0b013e318219c171.Search in Google Scholar

2. Sutton, AJ, Cooper, NJ, Jones, DR, Lambert, PC, Thompson, JR, Abrams, KR. Evidence-based sample size calculations based upon updated meta-analysis. Stat Med 2007;26:2479–500. https://doi.org/10.1002/sim.2704.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

3. Glasziou, P, Altman, DG, Bossuyt, P, Boutron, I, Clarke, M, Julious, S, et al. Reducing waste from incomplete or unusable reports of biomedical research. Lancet 2014;383:267–76. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(13)62228-x.Search in Google Scholar

4. Chalmers, I, Glasziou, P. Avoidable waste in the production and reporting of research evidence. Lancet 2009;374:86–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(09)60329-9.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

5. Guyatt, GH, Oxman, AD, Vist, GE, Kunz, R, Falck-Ytter, Y, Alonso-Coello, P, et al. GRADE: an emerging consensus on rating quality of evidence and strength of recommendations. BMJ 2008;2008:924–6. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.39489.470347.ad.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

6. Ferreira, ML, Herbert, RD, Crowther, MJ, Verhagen, A, Sutton, AJ. When is a further clinical trial justified? BMJ 2012;345: e5913. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.e5913.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

7. Williams, AC, Eccleston, C, Morley, S. Psychological therapies for the management of chronic pain (excluding headache) in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2012;11:CD007407.10.1002/14651858.CD007407.pub3Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

8. Viergever, RF, Ghersi, D. The quality of registration of clinical trials. PLoS One 2011;6: e14701. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0014701.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

9. Chan, A-W, Song, F, Vickers, A, Jefferson, T, Dickerson, K, Gotzsche, PC, et al. Increasing value and reducing waste: addressing inaccessible research. Lancet 2014;383:257–66. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(13)62296-5.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

10. Goldacre, B, DeVito, NJ, Heneghan, C, Irving, F, Bacon, S, Fleminge, J. et al. Compliance with requirement to report results on the EU clinical trials register: cohort study and web resource. BMJ 2018;362:k3218. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.k3218.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

11. Zarin, DA, Tse, T, Williams, RJ, Rajakannan, T. Update on Trial Registration 11 years after the ICMJE policy was established. N Engl J Med 2017;376:383–91. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMsr1601330.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

12. Chan, AW. Out of sight but not out of mind: how to search for unpublished clinical trial evidence. BMJ 2012;344:d8013. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.d8013.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

13. Geneen, LJ, Moore, RA, Clarke, C, Martin, D, Colvin, LA, Smith, BH. Physical activity and exercise for chronic pain in adults: an overview of Cochrane reviews. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2017;1:CD011279. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD011279.pub2.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

© 2020 Walter de Gruyter GmbH, Berlin/Boston

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Editorial Comments

- Patients with shoulder pain referred to specialist care; treatment, predictors of pain and disability, emotional distress, main symptoms and sick-leave: a cohort study with a 6-months follow-up

- Inferring pain from avatars

- Systematic Review

- Repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation of the primary motor cortex in management of chronic neuropathic pain: a systematic review

- Topical Reviews

- Exploring the underlying mechanism of pain-related disability in hypermobile adolescents with chronic musculoskeletal pain

- Pain management programmes via video conferencing: a rapid review

- Clinical Pain Research

- Prevalence of temporomandibular disorder in adult patients with chronic pain

- A cost-utility analysis of multimodal pain rehabilitation in primary healthcare

- Psychosocial subgroups in high-performance athletes with low back pain: eustress-endurance is most frequent, distress-endurance most problematic!

- Trajectories in severe persistent pain after groin hernia repair: a retrospective analysis

- Involvement of relatives in chronic non-malignant pain rehabilitation at multidisciplinary pain centres: part one – the patient perspective

- Observational Studies

- Recurrent abdominal pain among adolescents: trends and social inequality 1991–2018

- Cross-cultural adaptation and psychometric validation of the Hausa version of Örebro Musculoskeletal Pain Screening Questionnaire in patients with non-specific low back pain

- A proof-of-concept study on the impact of a chronic pain and physical activity training workshop for exercise professionals

- Intravenous patient-controlled analgesia vs nurse administered oral oxycodone after total knee arthroplasty: a retrospective cohort study

- Everyday living with pain – reported by patients with multiple myeloma

- Original Experimental

- The CA1 hippocampal serotonin alterations involved in anxiety-like behavior induced by sciatic nerve injury in rats

- A single bout of coordination training does not lead to EIH in young healthy men – a RCT

- Think twice before starting a new trial; what is the impact of recommendations to stop doing new trials?

- The association between selected genetic variants and individual differences in experimental pain

- Decoding of facial expressions of pain in avatars: does sex matter?

- Differences in personality, perceived stress and physical activity in women with burning mouth syndrome compared to controls

- Educational Case Reports

- Leiomyosarcoma of the small intestine presenting as abdominal myofascial pain syndrome (AMPS): case report

- Duloxetine for the management of sensory and taste alterations, following iatrogenic damage of the lingual and chorda tympani nerve

- Lead extrusion ten months after spinal cord stimulator implantation: a case report

- Short Communication

- Postoperative opioids and risk of respiratory depression – A cross-sectional evaluation of routines for administration and monitoring in a tertiary hospital

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Editorial Comments

- Patients with shoulder pain referred to specialist care; treatment, predictors of pain and disability, emotional distress, main symptoms and sick-leave: a cohort study with a 6-months follow-up

- Inferring pain from avatars

- Systematic Review

- Repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation of the primary motor cortex in management of chronic neuropathic pain: a systematic review

- Topical Reviews

- Exploring the underlying mechanism of pain-related disability in hypermobile adolescents with chronic musculoskeletal pain

- Pain management programmes via video conferencing: a rapid review

- Clinical Pain Research

- Prevalence of temporomandibular disorder in adult patients with chronic pain

- A cost-utility analysis of multimodal pain rehabilitation in primary healthcare

- Psychosocial subgroups in high-performance athletes with low back pain: eustress-endurance is most frequent, distress-endurance most problematic!

- Trajectories in severe persistent pain after groin hernia repair: a retrospective analysis

- Involvement of relatives in chronic non-malignant pain rehabilitation at multidisciplinary pain centres: part one – the patient perspective

- Observational Studies

- Recurrent abdominal pain among adolescents: trends and social inequality 1991–2018

- Cross-cultural adaptation and psychometric validation of the Hausa version of Örebro Musculoskeletal Pain Screening Questionnaire in patients with non-specific low back pain

- A proof-of-concept study on the impact of a chronic pain and physical activity training workshop for exercise professionals

- Intravenous patient-controlled analgesia vs nurse administered oral oxycodone after total knee arthroplasty: a retrospective cohort study

- Everyday living with pain – reported by patients with multiple myeloma

- Original Experimental

- The CA1 hippocampal serotonin alterations involved in anxiety-like behavior induced by sciatic nerve injury in rats

- A single bout of coordination training does not lead to EIH in young healthy men – a RCT

- Think twice before starting a new trial; what is the impact of recommendations to stop doing new trials?

- The association between selected genetic variants and individual differences in experimental pain

- Decoding of facial expressions of pain in avatars: does sex matter?

- Differences in personality, perceived stress and physical activity in women with burning mouth syndrome compared to controls

- Educational Case Reports

- Leiomyosarcoma of the small intestine presenting as abdominal myofascial pain syndrome (AMPS): case report

- Duloxetine for the management of sensory and taste alterations, following iatrogenic damage of the lingual and chorda tympani nerve

- Lead extrusion ten months after spinal cord stimulator implantation: a case report

- Short Communication

- Postoperative opioids and risk of respiratory depression – A cross-sectional evaluation of routines for administration and monitoring in a tertiary hospital