Abstract

Objectives

The association between socioeconomic status and recurrent abdominal pain (RAP) among adolescents is an understudied issue. No study has examined whether such an association changes over time. The aim was to examine trends in RAP among adolescents in Denmark from 1991 to 2018, to examine whether there was social inequality in RAP and whether this inequality varied over time.

Methods

The study used data from the Danish part of the international Health Behaviour in School-aged Children (HBSC) study of nationally representative samples of 11-, 13- and 15-year-olds. This study pooled data from eight comparable surveys from 1991 to 2018, overall participation rate 88.0%, n=30,048. The definition of RAP was self-reported stomach-ache daily or several days per week during the past six months. We reported absolute inequality as prevalence difference in RAP between low and high socioeconomic status and relative inequality as odds ratio for RAP by socioeconomic status.

Results

In the entire study population, 5.6% reported RAP, 3.1% among boys and 7.8% among girls. There was a significant increase in RAP from 1991 to 2018 among boys and girls, test for trend, p<0.0001. The prevalence of RAP was significantly higher in low than high socioeconomic status, OR=1.63 (95% CI: 1.42–1.87). The absolute social inequality in RAP fluctuated with no consistent increasing or decreasing pattern.

Conclusions

The prevalence of RAP increased from 1991 to 2018. The prevalence was significantly higher among girls than among boys, and significantly higher in low socioeconomic status families. Professionals should be aware of RAP as common and potentially serious health problems among children and adolescents. In addition to clinical examination it is important to focus on improving the child’s quality of life, reduce parents’ and children’s concerns about the seriousness of the condition, and consider supplements to medicine use.

Introduction

Recurrent abdominal pain (RAP) is common among children and adolescents [1], [2], [3]. Studies which apply Apley’s criteria (at least three episodes of abdominal pain occurring in the space of three months, severe enough to affect daily activities) find prevalences between 2.5 and 16% [4], [5]. Studies which apply looser criteria with the risk of including trivial cases find higher prevalences [numbers] but regardless of study, RAP is a common problem among school-aged children. Many adolescent girls suffer from severe menstrual pain [6] and it is likely that there are sex-related qualitative differences in RAP. RAP can interfere with daily function related to school and social activities [7] and is often co-occurring with other pains such as headache and backpain [8]. RAP is predictive of sleep disorders [9], internalizing symptoms [5], [10], poor wellbeing [11], use of health care services [3], [12], and psychiatric disorders in adulthood [13], [14]. For these reasons, RAP is an important public health issue among adolescents.

Several studies have shown social inequality in abdominal pain among adolescents, i.e. highest prevalence in lower social strata [1], [5], [15], [16]. Ottová-Jordan et al. [17] show that the prevalence of pain among adolescents fluctuates over time but little is known about time trends in RAP. If RAP fluctuates over time, the social inequality may also change over time, and it is important to study such change over time to target interventions. We have not been able to find studies which address this issue.

The aims of this study are therefore 1) to examine time trends of RAP among adolescents in Denmark over a long time period, 1991–2018, 2) to examine whether there is social inequality in RAP and 3) whether social inequality varies over time. We expect that RAP is highest in lower social strata corresponding to the general social inequality in health complaints among adolescents [1], [16] and that the prevalence increases over time since there has been a general increase in aches and psychosomatic symptoms among adolescents in the Nordic countries [18], [19], [20], [21]. We expect that the social inequality increases over time. Social inequality in health-related outcomes tends to increase with increasing economic disparities in the society [22], [23], [24], [25], [26] and there has been a substantial increase in economic inequality in Denmark during the past 30 years [23], [27].

Methods

Study design and study population

The study used data from the Danish arm of the international Health Behaviour in School-aged Children (HBSC) study [1]. The study design was repeated and comparable studies of nationally representative samples of three age groups, 11-, 13- and 15-year-olds, following a standard protocol for sampling, measurement and data collection. This study used data from eight surveys in Denmark in 1991, 1994, 1998, 2002, 2006, 2010, 2014 and 2018. In Denmark, we recruited data from random samples of schools, a new sample in each survey, drawn from complete lists of public and private schools. In each school we invited all students in the fifth, seventh and ninth grade (corresponding to the age groups 11, 13 and 15) to participate and complete the internationally standardized HBSC questionnaire in the classroom [28]. The participation rate across all eight surveys was 88.0%, n=35,320. This study included students with complete information about sex, age, prevalence of abdominal pain and the family’s occupational social class (OSC), n=30,048 (Table 1).

Study population by the included variables and absolute social inequality in recurrent abdominal pain (RAP).

| Survey year | 1991 | 1994 | 1998 | 2002 | 2006 | 2010 | 2014 | 2018 | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Participation ratea | 90.2% | 89.5% | 89.9% | 89.3% | 88.8% | 86.3% | 85.7% | 84.8% | 88.0% |

| N | 1,860 | 4,046 | 5,205 | 4,824 | 6,269 | 4,922 | 4,534 | 3,660 | 35,320 |

| Included in this studyb | 1,648 | 3,578 | 4,685 | 4,258 | 4,977 | 4,125 | 3,796 | 2,981 | 30,048 |

| Distribution by sex | |||||||||

| % Boys | 49.7 | 49.0 | 49.4 | 48.1 | 48.5 | 49.0 | 47.4 | 48.4 | 48.6 |

| % Girls | 50.3 | 50.0 | 50.6 | 51.9 | 51.5 | 51.0 | 52.6 | 51.6 | 51.4 |

| By age group | |||||||||

| % 11-year-olds | 29.8 | 30.5 | 33.4 | 35.5 | 36.1 | 35.1 | 28.7 | 39.0 | 33.8 |

| % 13-year-olds | 35.0 | 34.6 | 35.6 | 33.2 | 36.0 | 34.7 | 36.1 | 34.6 | 35.0 |

| % 15-year-olds | 35.3 | 34.9 | 31.0 | 31.3 | 27.9 | 30.2 | 35.1 | 26.5 | 31.2 |

| By OSC | |||||||||

| % Highc | 28.4 | 33.2 | 28.0 | 24.6 | 27.7 | 38.8 | 42.4 | 42.8 | 32.9 |

| % Middlec | 51.8 | 48.5 | 49.7 | 54.4 | 49.5 | 42.3 | 41.5 | 44.7 | 47.8 |

| % Lowc | 19.8 | 18.3 | 22.3 | 21.0 | 22.8 | 18.9 | 16.1 | 12.4 | 19.3 |

| Boys with RAP, pctc | |||||||||

| All boysd | 2.2 | 2.5 | 2.6 | 2.9 | 2.8 | 3.6 | 3.9 | 3.9 | 3.1 |

| 95% CI | 1.2–3.2 | 1.7–3.2 | 1.9–3.2 | 2.2–3.6 | 2.1–3.4 | 2.8–4.3 | 3.1–4.8 | 2.9–4.9 | 2.8–3.3 |

| Boys in high OSC | 2.8 | 2.4 | 2.1 | 3.5 | 2.2 | 2.6 | 2.7 | 3.1 | 2.6 |

| 95% CI | 0.6–4.9 | 1.2–3.6 | 1.0–3.2 | 2.0–5.0 | 1.1–3.3 | 1.5–3.7 | 1.6–3.7 | 1.8–4.5 | 2.2–3.1 |

| Boys in middle OSCd | 1.2 | 1.8 | 2.2 | 2.3 | 2.2 | 4.1 | 4.7 | 4.3 | 2.8 |

| 95% CI | 0.2–2.2 | 0.9–2.7 | 1.3–3.0 | 1.4–3.1 | 1.4–3.0 | 2.8–5.4 | 3.1–6.2 | 2.7–5.9 | 2.4–3.2 |

| Boys in low OSC | 4.3 | 4.4 | 4.1 | 3.7 | 4.9 | 4.4 | 5.9 | 5.4 | 4.5 |

| 95% CI | 1.1–7.4 | 2.1–6.6 | 2.4–5.8 | 2.0–5.5 | 3.1–6.6 | 2.3–6.5 | 3.2–8.6 | 2.2–8.7 | 3.8–5.3 |

| Prevalence differencee | 1.5 | 2.0 | 2.0f | 0.3 | 2.7f | 1.8 | 3.2f | 2.3 | 1.9f |

| 95% CI | −2.2–5.3 | −0.6–4.5 | 0.0–4.1 | −2.1–2.6 | 0.1–4.7 | −0.5–4.2 | 0.3–6.2 | −1.2–5.8 | 1.0–2.8 |

| Girls with RAP, pctc | |||||||||

| All girlsd | 6.0 | 7.5 | 6.5 | 8.1 | 7.3 | 7.1 | 10.1 | 9.0 | 7.8 |

| 95% CI | 4.4–7.6 | 6.3–8.8 | 5.5–7.5 | 6.9–9.3 | 6.5–8.6 | 6.0–8.2 | 8.7–11.4 | 7.6–10.5 | 7.3–8.2 |

| Girls in high OSCd | 2.6 | 6.1 | 6.4 | 7.4 | 6.4 | 6.2 | 10.0 | 6.2 | 6.8 |

| 95% CI | 0.6–4.6 | 4.1–8.1 | 4.6–8.3 | 5.1–9.7 | 4.5–8.2 | 4.5–7.9 | 7.8–12.1 | 4.3–8.1 | 6.1–7.5 |

| Girls in middle OSCd | 6.0 | 7.8 | 5.9 | 7.1 | 7.6 | 7.1 | 8.9 | 9.8 | 7.5 |

| 95% CI | 3.7–8.2 | 6.1–9.6 | 4.6–7.3 | 5.6–8.5 | 6.1–9.1 | 5.4–8.8 | 7.0–10.9 | 7.5–12.0 | 6.9–8.1 |

| Girls in low OSCd | 10.7 | 9.0 | 7.9 | 11.6 | 8.7 | 8.8 | 13.3 | 15.9 | 10.1 |

| 95% CI | 6.1–15.4 | 6.0–12.0 | 5.6–10.2 | 8.6–14.5 | 6.4–11.1 | 6.0–11.5 | 9.7–17.0 | 10.6–21.3 | 9.0–11.2 |

| Prevalence differencee | 8.1f | 2.9 | 1.5 | 4.2f | 2.4 | 2.6 | 3.4 | 9.7f | 3.3f |

| 95% CI | 3.0–13.2 | −0.7–6.5 | −1.5–4.5 | 0.4–7.9 | −0.6–5.4 | −0.7–5.8 | −0.9–7.6 | 4.0–15.4 | 2.0–4.6 |

-

aNumber of participants in the data file as percentage of schoolchildren enrolled in the participating classes.

-

bParticipants with full information on sex, age group, occupational social class and abdominal pain.

-

cSex and age standardized prevalences.

-

dTrend from 1991 to 2018 was increasing and the increase was statistically significant, p<0.01.

-

ePercent point difference between low and high occupational social class.

-

fPrevalence difference statistically significant assessed by confidence limits, p<0.05.

Measurements

RAP was measured by the item: “In the last six months, how often have you had stomach-ache?” We dichotomized the responses into recurrent (“about every day” and “more than once a week”) vs. non-recurrent (“about every week”, “about every month”, and “rarely or never”). Two studies suggested that this measure is reliable assessed by consistent response patterns and valid assessed by qualitative interviews [29], [30]. This measurement was similar in all eight surveys.

The students’ socioeconomic status was measured by their parents’ OSC. The students answered these questions: “Does your father/mother have a job?”, “If no, why does he/she not have a job?”, “If yes, please say in what place he/she works (for example: hospital, bank, restaurant)” and “Please write down exactly what job he/she does there (for example: teacher, bus driver)”. The research group coded the answers into OSC from I (high) to V (low). We added OSC VI for economically inactive parents who receive unemployment benefits, disability pension or other kinds of transfer income, similarly based on students’ responses. The questions about occupation were identical across surveys and so was the coding procedure [31]. Most students (88.3%) provided enough information for the coding of OSC. Several studies showed that schoolchildren in these age categories can report their parents’ occupation with a high agreement with parents’ own information [32] and Pförtner et al. [33] showed that OSC is an appropriate variable for studies of social inequality in adolescents’ health. Each participant was categorized by the highest-ranking parent into three levels of OSC: High (I–II, e.g. professionals and managerial positions), middle (III–IV, e.g. technical and administrative staff, skilled workers), and low (V, unskilled workers and VI, economically inactive).

Statistical procedures

The prevalence of RAP is considerably higher among girls than boys [1], [3], [4] and we therefore conducted all analyses separately for boys and girls. We calculated age-standardized prevalence proportions of RAP with 95% confidence intervals. The analyses included X2-test for homogeneity and Cochran–Armitage test for trends over time. The analyses of social inequality of RAP included two approaches: 1) Prevalence difference between low and high OSC as an indicator of absolute social inequality and 2) logistic regression analyses to examine the relative social inequality. The logistic regression analyses included OSC, age group and survey year in mutually adjusted models and a final model with inclusion of an interaction term (survey year * OSC) to assess potential interaction between survey year and OSC. The analyses accounted for the applied cluster sampling by means of multilevel modelling (PROC GLIMMIX in SAS). Finally, we repeated the analyses with two other cut-points of RAP, 1) daily abdominal pain (“about every day”) vs. less often and 2) weekly abdominal pain (“about every day“, “more than once a week”, “about every week”) vs. less often.

Ethical approval

There is no formal agency for approval of questionnaire-based surveys in Denmark. Therefore, we asked the school board as the parents’ representative, the headmaster, and the students’ council in each of the participating schools to approve the study. The participants received oral and written information that participation was voluntary, and that data were treated confidentially. The study complied with national standards for data protection. From 2014 the Danish Data Protection Authority has requested notification of such studies and has granted acceptance for the 2014 survey (Case No. 2013-54-0576) and the 2018 survey (Case No. 10 622, University of Southern Denmark).

Results

Time trends

In the entire study population combining all eight surveys, 5.6% (95% CI: 5.3–5.8) reported RAP, increasing from 4.1% (3.1–5.0) in 1991 to 6.5% (5.6–7.4) in 2018 (test for trend, p<0.0001). Among boys 3.1% (2.8–3.4) reported RAP, increasing from 2.2% (1.2–3.2) in 1991 to 3.9% (2.9–4.9) in 2018 (test for trend, p<0.0001). Among girls, 7.8% (7.3–8.2) reported RAP, increasing from 6.0% (4.4–7.6) in 1991 to 9.0% (7.6–10.5) in 2018 (test for trend, p<0.0001) (Table 1). The OR (95% CI) for RAP was 2.67 (2.38–2.98) for girls compared to boys and it was 0.89 (0.79–1.00) among 13-year-olds and 0.65 (0.57–0.74) among 15-year-olds compared to 11-year-olds.

Absolute social inequality

In the entire study population, the prevalence of RAP was significantly higher among adolescents from low 7.5% (6.8–8.2) than high OSC 4.8% (4.4–5.2). The difference in RAP between low and high OSC was statistically significant for both boys (p<0.0001) and girls (p<0.0001). The prevalence of RAP among 4,404 students without information about OSC was similar to the prevalence in low OSC, 7.5% (6.8–8.2) (not shown in table, not included in the analyses). Table 1 shows that the absolute social inequality assessed by prevalence difference between low and high OSC fluctuated across the survey years without any clear increasing or decreasing pattern.

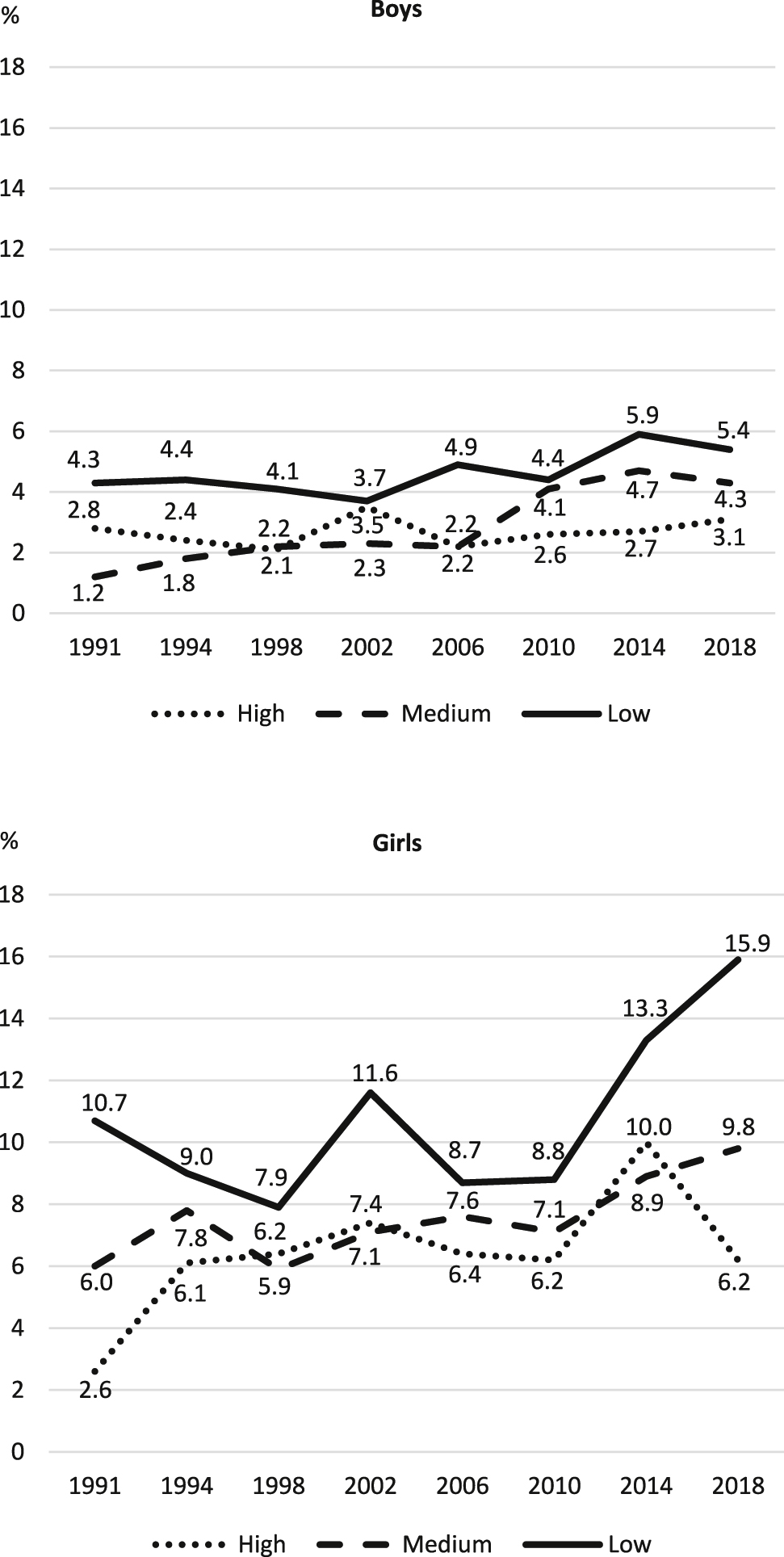

Figure 1 shows the prevalence of RAP by year and OSC among boys and girls. The prevalence of RAP was higher in low than high OSC in every survey year. The increase in RAP from 1991 to 2018 was statistically significant assessed by test for trend among boys from the middle OSC and among girls from high, middle and low OSC (test for trend, all p-values<0.01). Figure 1 confirms the pattern of fluctuating absolute inequality with no systematic increasing or decreasing difference between low and high OSC.

Age-standardized percent with recurrent abdominal pain by sex, survey year and occupational social class.

Relative social inequality

Table 2 shows the adjusted OR (95% CI) for RAP. In the entire study population, the OR (95% CI) for RAP was 1.13 (1.00–1.28) in middle and 1.63 (1.42–1.87) in low compared to high OSC. The association between OSC and RAP was almost similar for boys and girls. The interaction term (OSC * survey year) was not significant, pgirls=0.7532 and pboys=0.5083, i.e. survey year did not significantly modify the association between OSC and RAP which means that the relative social inequality was stable.

Mutually adjusted OR (95% CI) for recurrent abdominal paina.

| Independent variables | Boys + girls, n=30,048 | Boys, n=14,616b | Girls, n=15,432b |

|---|---|---|---|

| High (reference) | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Medium | 1.13 (1.00–1.28) | 1.12 (0.89–1.40) | 1.13 (0.98–1.31) |

| Low | 1.63 (1.42–1.87) | 1.81 (1.40–2.33) | 1.57 (1.33–1.85) |

| Boys (reference) | 1 | – | – |

| Girls | 2.67 (2.38–2.98) | – | – |

| 11-year-olds (reference) | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 13-year-olds | 0.89 (0.79–1.00) | 0.78 (0.63–0.97) | 0.94 (0.82–1.08) |

| 15-year-olds | 0.65 (0.57–0.74) | 0.54 (0.42–0.70) | 0.70 (0.60–0.82) |

| 1991 (reference) | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 1994 | 1.26 (0.92–1.71) | 1.10 (0.62–1.98) | 1.32 (0.92–1.89) |

| 1998 | 1.11 (0.82–1.51) | 1.16 (0.67–2.01) | 1.10 (0.77–1.57) |

| 2002 | 1.38 (1.02–1.87) | 1.31 (0.75–2.28) | 1.42 (1.00–2.01) |

| 2006 | 1.24 (0.92–1.72) | 1.26 (0.73–2.17) | 1.23 (0.87–1.75) |

| 2010 | 1.33 (0.98–1.81) | 1.62 (0.94–2.79) | 1.24 (0.87–1.76) |

| 2014 | 1.82 (1.34–2.47) | 1.84 (1.06–3.19) | 1.83 (1.29–2.60) |

| 2018 | 1.69 (1.24–2.32) | 1.86 (1.06–3.28) | 1.64 (1.14–2.37) |

-

aThe analyses accounted for the applied cluster sampling by means of multilevel modelling (PROC GLIMMIX in SAS).

-

bInclusion of an interaction term (survey year * OSC) in the analysis showed insignificant interaction, pgirls=0.7532, pboys=0.5083. Estimates in bold are statistically significant.

Sensitivity analyses

Analyses with the cut-point “daily abdominal pain” showed that 0.9% (0.7–1.1) of boys and 2.5% (2.2–3.7) of girls reported pain daily, p<0.0001. Among boys, the OR (95% CI) for RAP was 1.06 (0.85–1.32) in the middle and 1.71 (1.34–2.18) in the low compared to high OSC. Among girls, the corresponding figures were 1.02 (0.65–1.61) and 2.53 (1.60–3.99), i.e. a similar pattern of social inequality. Analyses with the cut-point “at least weekly abdominal pain” showed that 8.3% (7.8–8.7) of the boys and 16.9% (16.3–17.6) of the girls had abdominal pain at least one day every week, p<0.0001. The OR for RAP was 1.01 (0.93–1.09) in the middle and 1.28 (1.16–1.42) in the low compared to high OSC among boys. Among girls the corresponding figures were 1.02 (0.89–1.18) and 1.43 (1.21–1.69), again a similar and significant pattern of social inequality.

Discussion

Main findings

RAP was common as 3.1% of boys and 7.8% of girls report having stomach-ache every day or several days a week. The prevalence of daily RAP was 0.9 and 2.5% among boys and girls, and the prevalence of RAP at least one day per week was 8.3 and 16.9% among boys and girls. These prevalences correspond with other studies of RAP finding prevalences between 2.5 and 16% [1], [3], [4], [5], [6]. The increasing prevalence among both boys and girls from 1991 to 2018 was significant assessed by test for trend, but not assessed by the confidence limits around the prevalence estimates. The Cochran–Armitage test for trend [34] is based on the regression coefficient for a weighted linear regression of a binomial proportion of a variable (here: prevalence of RAP) on an explanatory variable (here: survey year), i.e. it assesses the general picture of a trend rather than the specific comparison of estimates from single survey years.

Several other studies of pain and psychosomatic complaints among adolescents in the Nordic countries suggest similar increases over time [18], [19], [20], [21]. During the observation period 1991–2018 there was an increasing trend for some risk factors for RAP (emotional symptoms, poor life satisfaction, loneliness, and perceived school pressure). On the other hand, there was a decreasing trend for other risk factors (smoking, alcohol use, and exposure to bullying) [35]. Potrebny et al. [21] suggest that the increase in over time may be related to an increasing trend in internalizing problems, loneliness, and decreasing age of puberty.

The finding of a decreasing prevalence with age during adolescence corresponds with other studies from the Nordic countries [36] and Germany [3]. RAP increases in childhood and decreases in adolescence [5], [36]. This association is poorly understood and King et al. [36] suggest that future pain research should include a developmental perspective in order to obtain a greater understanding of pain prevalence throughout the lifespan.

RAP was significantly more prevalent among adolescents from lower than higher OSC groups. This social inequality appeared among both boys and girls, in all survey years, and regardless of the cut-point for RAP. The finding of a social inequality in RAP corresponds with a few other studies [1], [5], [15], [16]. The absolute social inequality in RAP fluctuated from 1991 to 2018 with no clear increasing or decreasing trend and the relative social inequality was persistent. There are few other studies of time trends in RAP and whether changes over time influence the social inequality in RAP. According to Fryer et al. [37] the social inequality in RAP may be partially explained by the social patterning of risk factors for pain. Greco et al. [38] suggest that exposure to bullying and other forms of victimization is an important pathway to abdominal pain and exposure to bullying is most common in lower social strata [39]. The higher prevalence of RAP in the lower OSC group may also be related to a higher proportion of foreign-born adolescents in the lower OSC group. Kokkonen et al. [6] show that diet, e.g. milk-related organic disorders is a common cause of RAP, so dietary practices in first-generation immigrant families may result in a higher prevalence of RAP. Our expectation of an increasing social inequality in RAP, related to the increasing income inequality in Denmark in recent decades [23], [27] was not confirmed, as the social inequality in RAP did not change 1991–2018.

Limitations

The strength of this study was that it included eight nationally representative surveys of adolescents conducted over a 27-year period and that these studies are comparable as they used identical procedures for sampling and measurement. The participation rate was high (88.0%) but the study may still suffer from some selection bias: It is likely that the non-participants due to school absence included a high proportion of children with health problems such as RAP and the proportion with RAP was higher among the participants which were excluded from the analyses because of missing information about OSC. Therefore, the study may underestimate the proportion of adolescents with RAP. Validation studies suggest that the measurement of the two main variables, RAP and OSC is valid and appropriate [29], [30], [32], [33].

The measurement of RAP was quite restrictive (stomachache almost daily or more than weekly during the past six months), maybe too restrictive because stomachache less often also may be a threat to the adolescents’ life quality. It is a limitation that the definition did not include criteria for intensity of pain, e.g. severe enough to affect daily activities, so there is a risk that the measure included trivial cases.

Implications

This study raises several issues which should be addressed in future research about the epidemiology of RAP: The measurement of abdominal pain should focus on both frequency and intensity, e.g. use the clinical definition of RAP which is at least three episodes of pain that occur over three months and affect the child’s ability to perform normal activities [40]. Time trends in RAP may differ for light and intense pain and the association between RAP and OSC may also differ for light and intense pain. Future research should include a separate measure of menstrual pain among girls and separate functional (nonorganic) and organic abdominal pain. Future studies should also pay more attention to the consequences of RAP, consequences for the children and their families as well as studies of health care utilization related to RAP. Further, it is important not only to present trends but also to explain the changing prevalence of RAP and we propose studies which analyses trends in relation to potential explanatory factors.

It is likely that interventions which reduce risk factors for RAP may contribute to prevention of RAP. Examples are strengthening of peer relations at school, reducing bullying at school [38] and reducing parental mental health problems [37]. It may be appropriate to initiate interventions in early childhood where functional somatic symptoms such as RAP are common [40]. Further, it is important that professionals working with children and adolescents are aware of RAP and know that it is a common and potentially serious health problem among children and adolescents. From a clinical perspective, it is important to elucidate the underlying causes of RAP. RAP is often caused by organic disorders and/or nutrition-related factors. For instance, Kokkonen et al. [6] found that milk-related organic disorders were common causes for RAP. In addition to a proper clinical examination it may be appropriate to follow Reust & Williams’ [40] principles for the management of functional abdominal pain: focus on improving the child’s quality of life, reduce parents’ and children’s concerns about the seriousness of the condition, and consider cognitive behaviour therapy as a potentially beneficial supplement to medicine use. These therapies seem to at least partly beneficial [41].

Funding source: Nordea Foundation

Award Identifier / Grant number: 501100004825

Acknowledgements

Bjørn E. Holstein was the Principal Investigator for the Danish HBSC studies until 1994, Pernille Due 1998–2010 and Mette Rasmussen from 2010.

-

Research funding: The Nordea foundation (grant number 02-2011-0122) provided economic support for the 2010 study and The Danish Health Authority (grant number 1-1010-274/13) for the 2018 survey. The funding agencies did not interfere in the study design, data collection, analysis, interpretation, writing of this article or the decision to submit the manuscript for publication. None of the authors received any honorarium, grant or other form of payment to produce the manuscript.

-

Author contributions: All authors have contributed substantially to the conception and design of the paper and to the interpretation of data. MTD, BEH, KRM, TPP and MR collected the data. BEH performed the analyses and wrote the first draft of the manuscript. All authors contributed to the writing of the manuscript and a critical revision of the intellectual content. All authors have approved the final version of the manuscript and are accountable for all aspects of the work.

-

Conflict of interest: The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest.

-

Informed consent and ethical approval: There is no formal agency for approval of questionnaire-based surveys in Denmark. Therefore, we asked the school board as the parents’ representative, the headmaster, and the students’ council in each of the participating schools to approve the study. The participants received oral and written information that participation was voluntary, and that data were treated confidentially. The study complied with national standards for data protection. From 2014 the Danish Data Protection Authority has requested notification of such studies and has granted acceptance for the 2014 survey (Case No. 2013-54-0576) and the 2018 survey (Case No. 10 622, University of Southern Denmark).

References

1. Inchley, J, Currie, D, Young, T, Samdal, O, Torsheim, T, Augustson, L, Mathieson, F, Aleman-Diax, A, Molcho, M, Weber, M, Barnekow, V, editors. Growing up unequal: gender and socioeconomic differences in young people’s health and well-being. Copenhagen: World Health Organization; 2016.Search in Google Scholar

2. Schwille, IJ, Giel, KE, Ellert, U, Zipfel, S, Enck, P. A community-based survey of abdominal pain prevalence, characteristics, and health care use among children. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2009;7:1062–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cgh.2009.07.002.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

3. Swain, MS, Henschke, N, Kamper, SJ, Gobina, I, Ottová-Jordan, V, Maher, CG. An international survey of pain in adolescents. BMC Publ Health 2014;14:447. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-14-447.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

4. Chitkara, DK, Rawat, DJ, Talley, NJ. The epidemiology of childhood recurrent abdominal pain in Western countries: a systematic review. Am J Gastroenterol 2005;100:1868–75. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1572-0241.2005.41893.x.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

5. Kokkonen, J, Haapalahti, M, Tikkanen, S, Karttunen, R, Savilahti, E. Gastrointestinal complaints and diagnosis in children: a population-based study. Acta Paediatr 2004;93:880–6. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1651-2227.2004.tb02684.x.Search in Google Scholar

6. De Sanctis, V, Soliman, A, Bernasconi, S, Bianchin, L, Bona, G, Bozzola, M, et al. Primary dysmenorrhea in adolescents: prevalence, impact and recent knowledge. Pediatr Endocrinol Rev 2015;13:512–20.Search in Google Scholar

7. Roth-Isigkeit, A, Thyen, U, Stöven, H, Schwarzenberger, J, Schmucker, P. Pain among children and adolescents: restrictions in daily living and triggering factors. Pediatrics 2005;115:e152–62. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2004-0682.10.1542/peds.2004-0682Search in Google Scholar PubMed

8. Huntley, ED, Campo, JV, Dahl, RE, Lewin, DS. Sleep characteristics of youth with functional abdominal pain and a healthy comparison group. J Pediatr Psychol 2007;32:938–49. https://doi.org/10.1093/jpepsy/jsm032.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

9. Youssef, NN, Atienza, K, Langseder, AL, Strauss, RS. Chronic abdominal pain and depressive symptoms: analysis of the national longitudinal study of adolescent health. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2008;6:329–32. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cgh.2007.12.019.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

10. Ayonrinde, OT, Ayonrinde, OA, Adams, LA, Sanfilippo, FM, O’ Sullivan, TA, Robinson, M, et al. The relationship between abdominal pain and emotional wellbeing in children and adolescents in the Raine study. Sci Rep 2020;10:1646. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-58543-0.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

11. Rytter, D, Rask, CU, Vestergaard, CH, Nybo Andersen, AM, Bech, BH. Non-specific health complaints and self-rated health in pre-adolescents; impact on primary health care use. Sci Rep 2020;10:3292. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-60125-z.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

12. Campo, JV, Di Lorenzo, C, Chiappetta, L, Bridge, J, Colborn, DK, Gartner, JCJr, et al. Adult outcomes of pediatric recurrent abdominal pain: do they just grow out of it?. Pediatrics 2001;108:E1. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.108.1.e1.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

13. Hotopf, M, Carr, S, Mayou, R, Wadsworth, M, Wessely, S. Why do children have chronic abdominal pain, and what happens to them when they grow up? Population based cohort study. BMJ 1998;316:1196–200. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.316.7139.1196.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

14. Grøholt, EK, Stigum, H, Nordhagen, R, Köhler, L. Recurrent pain in children, socio-economic factors and accumulation in families. Eur J Epidemiol 2003;18:965–75. https://doi.org/10.1023/a:1025889912964.10.1023/A:1025889912964Search in Google Scholar PubMed

15. Holstein, BE, Currie, C, Boyce, W, Damsgaard, MT, Gobina, I, Kökönyei, G, et al. Socio-economic inequality in multiple health complaints among adolescents: international comparative study in 37 countries. Int J Public Health 2009;54(2 Suppl):260–70. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00038-009-5418-4.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

16. Ottová-Jordan, V, Smith, OR, Gobina, I, Mazur, J, Augustine, L, Cavallo, F, et al. Trends in multiple recurrent health complaints in 15-year-olds in 35 countries in Europe, North America and Israel from 1994 to 2010. Eur J Publ Health 2015;25(2 Suppl):24–7. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurpub/ckv015.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

17. Due, P, Damsgaard, MT, Madsen, KR, Nielsen, L, Rayce, SB, Holstein, BE. Increasing prevalence of emotional symptoms in higher socioeconomic strata. Trend study among Danish schoolchildren 1991–2014. Scand J Publ Health 2019;47:690–94. https://doi.org/10.1177/1403494817752520.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

18. Hagquist, C, Due, P, Torsheim, T, Välimaa, R. Cross-country comparisons of trends in adolescent psychosomatic symptoms-a Rasch analysis of HBSC data from four Nordic countries. Health Qual Life Outcome 2019;17:27. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12955-019-1097-x.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

19. Holstein, BE, Andersen, A, Denbæk, AM, Johansen, A, Michelsen, SI, Due, P. Short communication: persistent social inequality in frequent headache among Danish adolescents from 1991 to 2014. Eur J Pain 2018;22:935–40. https://doi.org/10.1002/ejp.1179.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

20. Potrebny, T, Wiium, N, Haugstvedt, A, Sollesnes, R, Torsheim, T, Wold, B, et al. Health complaints among adolescents in Norway: a 20-year perspective on trends. PLoS One 2019;14:e0210509. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0210509.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

21. Elgar, FJ, Pförtner, TK, Moor, I, De Clercq, B, Stevens, GW, Currie, C. Socioeconomic inequalities in adolescent health 2002–2010: a time-series analysis of 34 countries participating in the health behaviour in school-aged children study. Lancet 2015;385:2088–95. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(14)61460-4.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

22. Jutz, R. The role of income inequality and social policies on income-related health inequalities in Europe. Int J Equity Health 2015;14:117. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12939-015-0247-y.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

23. Levin, KA, Torsheim, T, Vollebergh, W, Richter, M, Davies, CA, Schnohr, CW, et al. National income and income inequality, family affluence and life satisfaction among 13 year old boys and girls: a multilevel study in 35 countries. Soc Indicat Res 2011;104:179–94. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-010-9747-8.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

24. Rathmann, K, Ottova, V, Hurrelmann, K, de Loose, M, Levin, K, Molcho, M, et al. Macro-level determinants of young people’s subjective health and health inequalities: a multilevel analysis in 27 welfare states. Maturitas 2015;80:414–20. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.maturitas.2015.01.008.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

25. Torsheim, T, Currie, C, Boyce, W, Samdal, O. Country material distribution and adolescents’ perceived health: multilevel study of adolescents in 27 countries. J Epidemiol Comm Health 2006;60:156–61. https://doi.org/10.1136/jech.2005.037655.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

26. Tóth, I. Time series and cross country variation of income inequalities in Europe on the medium run: are inequality structures converging in the past three decades? GINI Policy Papers 3, AIAS: Amsterdam Institute for Advanced Labour Studies; 2013.Search in Google Scholar

27. Roberts, C, Freeman, J, Samdal, O, Schnohr, CW, de Looze, ME, Gabhainn, SN, et al. The health behaviour in school-aged children (HBSC) study: methodological developments and current tensions. Int J Public Health 2009;54(2 Suppl):140–50. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00038-009-5405-9.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

28. Haugland, S, Wold, B. Subjective health complaints in adolescence-reliability and validity of survey methods. J Adolesc 2001;24:611–24. https://doi.org/10.1006/jado.2000.0393.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

29. Haugland, S, Wold, B, Stevenson, J, Aarø, LE, Woynarowska, B. Subjective health complaints in adolescence. A cross-national comparison of prevalence and dimensionality. Eur J Publ Health 2001;11:4–10. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurpub/11.1.4.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

30. Christensen, U, Krølner, R, Nilsson, CJ, Lyngbye, PW, Hougaard, CØ, Nygaard, E, et al. Addressing social inequality in aging by the Danish occupational social class measurement. J Aging Health 2014;26:106–27. https://doi.org/10.1177/0898264314522894.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

31. Lien, N, Friedstad, C, Klepp, K-I. Adolescents’ proxy reports of parents’ socioeconomic status: how valid are they. J Epidemiol Comm Health 2001;55:731–7. https://doi.org/10.1136/jech.55.10.731.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

32. Pförtner, T-K, Günther, S, Levin, KA, Torsheim, T, Richter, M. The use of parental occupation in adolescent health surveys. An application of ISCO-based measures of occupational status. J Epidemiol Comm Health 2015;69:177–84. https://doi.org/10.1136/jech-2014-204529.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

33. Agresti, A. Categorical data analysis, 2nd ed. New York: John Wiley; 2002.10.1002/0471249688Search in Google Scholar

34. Rasmussen, M, Kierkegaard, L, Rosenwein, SV, Holstein, BE, Damsgaard, MT, Due, P, editors. The health behaviour in school-aged children study 2018: health, wellbeing and health behaviour among 11-, 13- and 15-yearolds in Denmark (In Danish: Skolebørnsundersøgelsen 2018: Helbred, trivsel og sundhedsadfærd blandt 11-, 13- og 15-årige skoleelever i Danmark). Copenhagen: National Institute of Public Health, University of Southern Denmark; 2019.Search in Google Scholar

35. King, S, Chambers, CT, Huguet, A, MacNevin, RC, McGrath, PJ, Parker, L, et al. The epidemiology of chronic pain in children and adolescents revisited: a systematic review. Pain 2011;152:2729–38. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pain.2011.07.016.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

36. Fryer, BA, Cleary, G, Wickham, SL, Barr, BR, Taylor-Robinson, DC. Effect of socioeconomic conditions on frequent complaints of pain in children: findings from the UK Millennium cohort study. BMJ Paediatr Open 2017;1:e000093. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjpo-2017-000093.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

37. Greco, LA, Freeman, KE, Dufton, L. Overt and relational victimization among children with frequent abdominal pain: links to social skills, academic functioning, and health service use. J Pediatr Psychol 2007;32:319–29. https://doi.org/10.1093/jpepsy/jsl016.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

38. Due, P, Merlo, J, Harel-Fisch, Y, Damsgaard, MT, Holstein, BE, Hetland, J, et al. Socioeconomic inequality in exposure to bullying during adolescence: a comparative cross-sectional, multilevel study in 35 countries. Am J Publ Health 2009;99:907–14. https://doi.org/10.2105/ajph.2008.139303.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

39. Reust, CE, Williams, A. Recurrent abdominal pain in children. Am Fam Physician 2018;97:785–93. https://doi.org/10.1007/springerreference_123784.Search in Google Scholar

40. Rask, CU, Olsen, EM, Elberling, H, Christensen, MF, Ornbøl, E, Fink, P, et al. Functional somatic symptoms and associated impairment in 5–7 year-old children: the Copenhagen child cohort 2000. Eur J Epidemiol 2009;24:625–34. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10654-009-9366-3.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

41. Huertas-Ceballos, A, Logan, S, Bennett, C, Macarthur, C. Psychosocial interventions for recurrent abdominal pain (RAP) and irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) in childhood. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2008:CD003014. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.cd003014.pub3.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

© 2020 Walter de Gruyter GmbH, Berlin/Boston

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Editorial Comments

- Patients with shoulder pain referred to specialist care; treatment, predictors of pain and disability, emotional distress, main symptoms and sick-leave: a cohort study with a 6-months follow-up

- Inferring pain from avatars

- Systematic Review

- Repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation of the primary motor cortex in management of chronic neuropathic pain: a systematic review

- Topical Reviews

- Exploring the underlying mechanism of pain-related disability in hypermobile adolescents with chronic musculoskeletal pain

- Pain management programmes via video conferencing: a rapid review

- Clinical Pain Research

- Prevalence of temporomandibular disorder in adult patients with chronic pain

- A cost-utility analysis of multimodal pain rehabilitation in primary healthcare

- Psychosocial subgroups in high-performance athletes with low back pain: eustress-endurance is most frequent, distress-endurance most problematic!

- Trajectories in severe persistent pain after groin hernia repair: a retrospective analysis

- Involvement of relatives in chronic non-malignant pain rehabilitation at multidisciplinary pain centres: part one – the patient perspective

- Observational Studies

- Recurrent abdominal pain among adolescents: trends and social inequality 1991–2018

- Cross-cultural adaptation and psychometric validation of the Hausa version of Örebro Musculoskeletal Pain Screening Questionnaire in patients with non-specific low back pain

- A proof-of-concept study on the impact of a chronic pain and physical activity training workshop for exercise professionals

- Intravenous patient-controlled analgesia vs nurse administered oral oxycodone after total knee arthroplasty: a retrospective cohort study

- Everyday living with pain – reported by patients with multiple myeloma

- Original Experimental

- The CA1 hippocampal serotonin alterations involved in anxiety-like behavior induced by sciatic nerve injury in rats

- A single bout of coordination training does not lead to EIH in young healthy men – a RCT

- Think twice before starting a new trial; what is the impact of recommendations to stop doing new trials?

- The association between selected genetic variants and individual differences in experimental pain

- Decoding of facial expressions of pain in avatars: does sex matter?

- Differences in personality, perceived stress and physical activity in women with burning mouth syndrome compared to controls

- Educational Case Reports

- Leiomyosarcoma of the small intestine presenting as abdominal myofascial pain syndrome (AMPS): case report

- Duloxetine for the management of sensory and taste alterations, following iatrogenic damage of the lingual and chorda tympani nerve

- Lead extrusion ten months after spinal cord stimulator implantation: a case report

- Short Communication

- Postoperative opioids and risk of respiratory depression – A cross-sectional evaluation of routines for administration and monitoring in a tertiary hospital

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Editorial Comments

- Patients with shoulder pain referred to specialist care; treatment, predictors of pain and disability, emotional distress, main symptoms and sick-leave: a cohort study with a 6-months follow-up

- Inferring pain from avatars

- Systematic Review

- Repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation of the primary motor cortex in management of chronic neuropathic pain: a systematic review

- Topical Reviews

- Exploring the underlying mechanism of pain-related disability in hypermobile adolescents with chronic musculoskeletal pain

- Pain management programmes via video conferencing: a rapid review

- Clinical Pain Research

- Prevalence of temporomandibular disorder in adult patients with chronic pain

- A cost-utility analysis of multimodal pain rehabilitation in primary healthcare

- Psychosocial subgroups in high-performance athletes with low back pain: eustress-endurance is most frequent, distress-endurance most problematic!

- Trajectories in severe persistent pain after groin hernia repair: a retrospective analysis

- Involvement of relatives in chronic non-malignant pain rehabilitation at multidisciplinary pain centres: part one – the patient perspective

- Observational Studies

- Recurrent abdominal pain among adolescents: trends and social inequality 1991–2018

- Cross-cultural adaptation and psychometric validation of the Hausa version of Örebro Musculoskeletal Pain Screening Questionnaire in patients with non-specific low back pain

- A proof-of-concept study on the impact of a chronic pain and physical activity training workshop for exercise professionals

- Intravenous patient-controlled analgesia vs nurse administered oral oxycodone after total knee arthroplasty: a retrospective cohort study

- Everyday living with pain – reported by patients with multiple myeloma

- Original Experimental

- The CA1 hippocampal serotonin alterations involved in anxiety-like behavior induced by sciatic nerve injury in rats

- A single bout of coordination training does not lead to EIH in young healthy men – a RCT

- Think twice before starting a new trial; what is the impact of recommendations to stop doing new trials?

- The association between selected genetic variants and individual differences in experimental pain

- Decoding of facial expressions of pain in avatars: does sex matter?

- Differences in personality, perceived stress and physical activity in women with burning mouth syndrome compared to controls

- Educational Case Reports

- Leiomyosarcoma of the small intestine presenting as abdominal myofascial pain syndrome (AMPS): case report

- Duloxetine for the management of sensory and taste alterations, following iatrogenic damage of the lingual and chorda tympani nerve

- Lead extrusion ten months after spinal cord stimulator implantation: a case report

- Short Communication

- Postoperative opioids and risk of respiratory depression – A cross-sectional evaluation of routines for administration and monitoring in a tertiary hospital