Abstract

The aim of this article is to construct a model that demonstrates how human communication, involving all kinds of media, may not only correspond to but also put us in contact with what we perceive to be the surrounding world. In which ways is truthfulness actually established by communication? To answer this, the notion of indices is employed: signs based on contiguity. However, an investigation of indices’ outward direction – creating truthfulness in communication – also requires an understanding of their inward direction: establishing coherence. To investigate these two functions, further concepts and various elementary categorizations are proposed: it is argued that there are several types of contiguity and many varieties of indexical objects, which invalidates the coarse fiction–nonfiction distinction.

1 Introduction

Truthfulness in communication should be investigated as thoroughly as possible because it involves accuracy, reliability, and value. Setting up actual connections to the world is central for many areas of communication and misconceptions of communicative (non-)truthfulness may have grave implications for both individuals and society at large.

How can truthfulness in all kinds of human communication be conceptualized so that it may be methodically investigated? This is the epistemological research question of this article. Existing research primarily examines how certain verbal propositions do or do not correspond to already known circumstances. These philosophical treatises mainly investigate a particular use of words understood as symbols: habitual signs. Although interesting, such investigations say little about how truthfulness is actually established by communication. This requires a focus on another kind of signs, that is, indices, that connect to objects not on the basis of habits or conventions, but of contiguity or real connections.

It furthermore requires attention to all kinds of communicative media, not only those involving language. Media products are those intermediate (bodily or non-bodily) material entities with semiotic capacities that make transfer of cognitive import among human minds possible through representation; media products thus act as collections of material signs that enable sharing mental objects (Elleström 2018). Note that the material–mental distinction is used not only to highlight a difference between the two realms, but also to demonstrate their strong interdependence.

The aim of this article is to construct a model of the ways human communication may put us in contact with what we perceive to be the surrounding world through indices: a conceptual framework for analyzing truthfulness in complex, and often multimodal communication. It should be valid for all media types, including those that are profoundly different: news reports, photographs, testimonies, novels, songs, chats, caresses, and scientific diagrams.

As will be demonstrated, however, such a framework requires an understanding of not only the outward direction of indices – generating truthfulness in communication – but also of their inward direction: forming coherence. These two facets will hence be investigated as the major functions of indices in human communication.

Consequently, the goal is to establish some basic theoretical principles for how coherence and especially truthfulness is achieved in communication. I will propose a series of distinctions of which the most essential is that between two different domains in the mind of the perceiver of media products: the intracommunicational, created in the act of communication, and the extracommunicational, existing prior to and outside the act of communication. The two basic functions of indices in communication can hence be identified as intracommunicational indexicality (internal coherence) and extracommunicational indexicality (external truthfulness). To investigate these functions properly, I will introduce further concepts and also propose various elementary categorizations in some vital, but under-researched areas; there are several types of contiguity and numerous varieties of indexical objects.

My approach will be semiotic, using some of Charles Sanders Peirce’s foundational conceptions and his notion of the index – which has been used surprisingly little in this research context – as starting points. I will try to grasp the entire field of human communication, moving beyond analysis of truthfulness in single written sentences. The philosophical research tradition of modal logic is hence only marginally relevant, as are indeed many of Peirce’s own ideas of truthfulness in propositions (discussed in Burke 1991; Howat 2015), although he discusses the role of indices in verbal propositions (Hookway 2000: 82–134) and is inclined to think of reasoning and propositions in terms that are broader than language alone (Stjernfelt 2014). Except for his notion of index, essential for understanding how communication connects to our experiences of the surrounding world (Bergman 2009), the article does not rely on Peirce’s general philosophical ideas about reality and truth (cf. McCarthy 1984; Nesher 1997).

My next move will therefore be to take a closer look at Peirce’s notion of index and briefly map the area of indexical objects. I will then present my distinction between intracommunicational and extracommunicational domains, including discussions of the nature of associated objects, which will be followed by a more refined description of spheres within the two domains. After that, I will suggest a foundational catalog of different kinds of contiguity, allowing us to discern various bases of internal coherence and external truthfulness. Subsequent sections will be devoted to charting varieties of internal coherence (more sketchy) and external truthfulness (including a list of types of extracommunicational indexical objects). In addition, the notion of communicating minds will be scrutinized in the light of the conceptual framework. Finally, I will briefly criticize the notions of fictionality and fiction in favor of a more nuanced conception of extracommunicational indexicality or external truthfulness.

2 Indices as real connections

In order to develop the model, a few basic semiotic notions derived from Peirce must be clarified. Most fundamentally, he distinguishes between three sign constituents: “A sign, or representamen, is something which stands to somebody for something in some respect or capacity.” In other words: the representamen stands for an object in some respects and thus “creates in the mind of that person” an interpretant (c.1897, CP 2.228). This entails that signs are not static items, but rather dynamical functions constituted by entirely relational constituents (existing only in interaction with each other) and mentally driven. Note that the term object refers to such a relational sign constituent throughout the article.

Peirce’s most productive way of distinguishing among different kinds of signs is to discern the relation between representamen and object, that is, the representing and represented entities. As these constituents are not arbitrarily connected (which would lead to cognitive chaos) there must be some kind of motivation for the connection to be established in the mind. Peirce sometimes calls this motivation the ground of the representamen and differs between three sign types characterized by their respective grounds: icons are based on similarity, indices on contiguity (1901, CP 2.305–2.306), and symbols on habits (this trichotomy is elaborated in various ways; see, for instance, 1906, CP 4.530–4.572). As icons, indices, and symbols are based on different, but compatible grounds (things may well be similar and contiguous at the same time, for instance), they hardly appear in isolation, but rather tend to cooperate in various ways.

The index is the semiotic backbone of my account of coherence and truthfulness in communication. As is often the case in Peirce’s writings, this notion is circumscribed in slightly shifting ways. As a rule, he emphasizes a physical cause and effect relation, that is, a “direct physical connection,” between representamen and object (c.1885, CP 1.372). Peirce thus argues that photographs, which are “in certain respects exactly like the objects they represent,” are not only icons, but also indices, since they are “produced under such circumstances that they [are] physically forced to correspond point by point to nature” (c.1895, CP 2.281). Likewise, symptoms of diseases are “signs which become such by virtue of being really connected with their objects” (c.1902, CP 8.119).

Although Peirce repeatedly emphasizes that the ground of an index is real, it is clear that the notion of indexicality goes beyond the real understood solely in physical terms. He also highlights non-physical connections, and sometimes he clearly states that indices do not “have exclusive reference to objects of experience” (1901, CP 2.305) and that “[i]t makes no difference whether the connection [between representamen and object] is natural, or artificial, or merely mental” (undated, CP 8.368). It should thus be noted that there is some tension in Peirce’s writings between his insistence that indexicality as such is based on palpable physical connections and his broader notion of indexicality being based also on mental contiguity (this strain is criticized by Goudge 1965 and defended by Atkin 2005). The solution is to adopt the notion most applicable for a wide-ranging analysis of communication: indices being based on real connections in a broad sense, including both material and mental contiguity (Elleström 2014: 102–105).

3 Indexical objects

This leads to the question: what is the nature of indexical objects? In the core of semiosis, representamens and objects, as well as interpretants, are mental. However, representamens may have an external material facet in that they are produced by perception of materiality; likewise, objects may have an external material facet in that they reach out to the material through recollection of former sensory perception of materiality (Elleström 2014).

Semiosis in communication, or, more precisely, semiosis that is immediately triggered by media products, is always built on material representamens. Additionally, semiosis in communication, as all semiosis, largely consists of chains of mental signs where interpretants become new mental representamens creating new interpretants and so on. In an utterance such as “I’m home,” the material sound of the voice tends to form symbols whose interpretants form mental indices referring to a specific person at a specific place.

In contrast, the objects of communicative signs may be mental as well as material. As contiguity may be both material and mental, this includes indexical objects. A comprehensive list of all kinds of indexical objects would amount to everything that is known, so I will here only give some general examples to demonstrate the large variety of phenomena that human communication may represent indexically. A rough categorization may start with material objects such as things: bodies, animals, and persons; physical qualities, properties and conditions; states of affairs; actions, movements, and events; certain places at certain times, etc. In contrast, there are mental objects such as percepts, experiences, emotions, psychological processes, ideas, convictions, ideologies, concepts, knowledge, volitions, intentions, etc. As the mental realm is very much interconnected with and formed by the experience of the material realm, many objects transgress the crude material–mental division. These include, for instance, spatiotemporal relations derived from the experience of being a body interacting with a surrounding world: distances, positions, interrelations, proportions, balance, structures, and contrasts.

These and many other objects may hence be represented through icons, indices, symbols, and, most commonly, through combinations of them. There is nothing extraordinary about indexical objects except that they are represented on the ground of contiguity; that is, real connections. In what follows, the different functions of these real connections and the nature of the various mental spheres where indexical objects are located in communication will be investigated.

4 Intracommunicational and extracommunicational domains and objects

We have noted that the representamens that initiate semiosis in communication come from sensory perception of media products. One perceives configurations of sound, vision, touch, and so forth that are created or brought out by someone and understood to signify something. But from where do the objects come? They clearly do not emerge out of nothing, but are drawn forth from earlier percepts, sensations, and notions that are stored, either in long-term or short-term memory, which may also cover ongoing communication. “Earlier” may hence be a century ago or a fraction of a second ago.

In semiotic terms, the stored mental entities may be direct percepts from outside of communication, interpretants from semiosis outside of communication, interpretants from semiosis in earlier communication, or interpretants from semiosis in ongoing communication. This is to say that objects of semiosis always require what Peirce calls “collateral experience” (1909, CP 8.177–8.185; cf. Bergman 2009) that may derive both from within and without ongoing communication. In other words: collateral experience may both be formed by semiosis inside the spatiotemporal frame of the communicative act, and stem from other, earlier involvements with the world, including former communication as well as direct experience of the surrounding existence.

In line with this twofold origin of collateral experience, I distinguish between two utterly entwined, but nevertheless dissimilar areas in the mind of the perceiver of media products: the intracommunicational and the extracommunicational domains, emphasizing a difference between the forming of cognitive import in ongoing communication and what precedes and surrounds it (cf. related, but divergent distinctions in cognitive psychology proposed by Brewer 1987: 187). I also find it appropriate to make a corresponding distinction between intracommunicational and extracommunicational objects, both formed by collateral experience from their respective domains.

Consequently, there are both intracommunicational and extracommunicational indexical objects. As indices are grounded on real connections, they are equally important for the two domains. On the one hand, they link entities in the intracommunicational domain to each other and thus establish coherence. Intracommunicational indices are the glue of semiosis, preventing separate interpretants created in communication from falling apart. On the other hand, they link entities in the intracommunicational domain to entities in the extracommunicational domain and thus establish truthfulness of various sorts and degrees. Extracommunicational indices are the anchor of semiosis, preventing the interpretants of communication from drifting away from the extracommunicational domain.

This is to say that the indexical junctions of representamens and objects result in interpretants that convince us that there is some coherence in what is being communicated and that the communicated substance is somehow linked to something external to the spatiotemporal frame of the communicative act.

From a temporal perspective, the extracommunicational domain is clearly prior to each new intracommunicational domain created. That is why I will roughly delineate the extracommunicational domain before exploring the intracommunicational domain. However, it will eventually become clear that the model sketched here actually has its center in the intracommunicational domain; my conceptual constructions are molded from the point of view of this domain. The discernment of something extracommunicational is obviously a consequence of focusing on what is intracommunicational.

4.1 Extracommunicational domain

The extracommunicational domain should thus be understood as the background area in the mind of the perceiver of media products. It comprises everything one is already familiar with. As it is a mental domain, it does not consist of the world as such, but rather of what one knows through perception and semiosis. This is to say that one’s stored experiences not only consist of percepts as such, but also of percepts that have been contemplated and processed by the mind through semiosis. The extracommunicational domain includes experiences of both what one presumes to be more objective states of affairs (dogs, universities, music, and statistical relations) and what one presumes to be more subjective states of affairs (states of mind related to individual experiences). It is thus actually formed in one’s mind not only through semiosis and immediate external perception, but also through interoception, proprioception, and mental introspection. The extracommunicational–intracommunicational domain distinction is hence very different from exterior–interior to the mind, world–individual, material–mental, and objective–subjective.

It is important to note that vital parts of the extracommunicational domain are constituted by perception and interpretation of media products. Former communication is thus very much part of what precedes and surrounds ongoing communication. Together, non-communicative and communicative prior experiences form “a horizon of possibilities,” to borrow an expression from Marie-Laure Ryan (1984: 127); the extracommunicational domain is the reservoir from which entities are selected to form new constellations of objects in the intracommunicational domain.

4.2 Intracommunicational domain

In contrast to the extracommunicational domain, the intracommunicational domain is the foreground area in the mind of the perceiver of media products. It is formed by one’s perception and interpretation of the media products that are present in the ongoing act of communication. It is based on both extracommunicational objects – emanating from the extracommunicational domain – and intracommunicational objects – arising in the intracommunicational domain – that together result in interpretants making up salient cognitive import in the perceiver’s mind. However, the intracommunicational domain is largely mapped upon the extracommunicational domain. Rehashing Ryan’s “principle of minimal departure” (1980: 406), I argue that one construes the intracommunicational domain as being the closest possible to the extracommunicational domain and allows for deviations only when it cannot be avoided.

As the intracommunicational domain is formed by communicative semiosis it may be called a virtual sphere. The virtual should not be understood in opposition to the actual but as something having potential. I hence define the virtual as a mental sphere, created by communicative semiosis, that has the potential to have real connections to the extracommunicational. A virtual sphere may hence represent extracommunicational objects indexically and be externally truthful.

A virtual sphere can consist of anything from a brief thought triggered by a few spoken words, a gesture, or a quick glance at an advertisement, to a complex narrative or a scientific theory formed by hours of watching television or reading books. Depending on the degree of attention to the media products, the borders of a virtual sphere need not necessarily be clearly defined. As communication is generally anything but flawless, a virtual sphere may be exceedingly incomplete or even fragmentary. It may also comprise what one apprehends as clashing ideas or inconsistent notions. As virtual spheres result from communication, they are, per definition, to a certain extent shareable among minds.

The coexistence of intracommunicational and extracommunicational objects results in a possible double view on virtual spheres: from one point of view, they form self-ruled spheres with a certain degree of experienced autonomy; from another point of view, they are always exceedingly dependent on the extracommunicational domain. The crucial point is that intracommunicational objects cannot be created ex nihilo; in effect, they are completely derived from extracommunicational objects. This is because nothing can actually be grasped in communication without the resource of extracommunicational objects. Even the most fanciful narratives require recognizable objects in order to make sense (cf. Bergman 2009: 261). To be more precise: intracommunicational objects are always in some way parts, combinations, or blends of extracommunicational objects; or, to be even more exact: intracommunicational objects are parts, combinations, or blends of interpretants resulting from representation of extracommunicational objects.

It is possible to represent, say, griffins (which, to the best of our knowledge, exist only in virtual spheres) because of one’s acquaintance with extracommunicational material objects such as lions and eagles that can easily be combined. A virtual sphere may even include notions such as a round square, consisting of two mutually exclusive extracommunicational objects together forming an odd intracommunicational object. Literary characters such as Lily Briscoe in Virginia Woolf’s novel To the Lighthouse are composite intracommunicational objects consisting of extracommunicational material and mental objects that stem from the world as one knows it. One cannot imagine Lily Briscoe unless one is fairly familiar with notions such as walking, talking, and eating; what it means to refer to persons with certain names; what women and men, adults and children are; what it means to love and to be bored; and what artistic creation is. Also, more purely mental extracommunicational objects may be modified or united into new mental intracommunicational objects. Objects such as familiar emotions may be combined into novel intracommunicational objects consisting of, say, conflicts between or blends of emotions that are perceived as unique although one is already acquainted with the components.

The question then arises: if all intracommunicational objects are ultimately derived from extracommunicational objects, how come virtual spheres are often experienced as having a certain degree of autonomy? This is because they, in part or in whole, may be perceived as new gestalts that disrupt the connection to the extracommunicational domain. This happens when one does not immediately recognize the new composites of extracommunicational objects. The reason for their not being re-cognized is that they have not earlier been cognized in the particular constellation in which they appear in the virtual sphere. Several such disruptions lead to greater perceived intracommunicational domain autonomy. Even though intracommunicational objects are entirely dependent on extracommunicational objects, one may thus say that they emerge within the intracommunicational domain.

The relation between extracommunicational and intracommunicational objects may be even more complex than hitherto indicated. Intracommunicational objects that are perceived as new gestalts might, in their turn, be part of more embracing gestalts that are recognized from the extracommunicational domain. A virtual sphere can contain representations of intracommunicational objects such as living trains formed by familiar extracommunicational objects such as “man-made machines for transportation” and “the quality of being animate and conscious” that together form a new gestalt. When living trains quarrel or fall in love with each other, however, they interact in a way that is recognized from the extracommunicational domain. The conclusion is that intracommunicational objects may be interspersed among extracommunicational objects in numerous, complicated ways.

5 Virtual sphere, other virtual spheres, perceived actual sphere

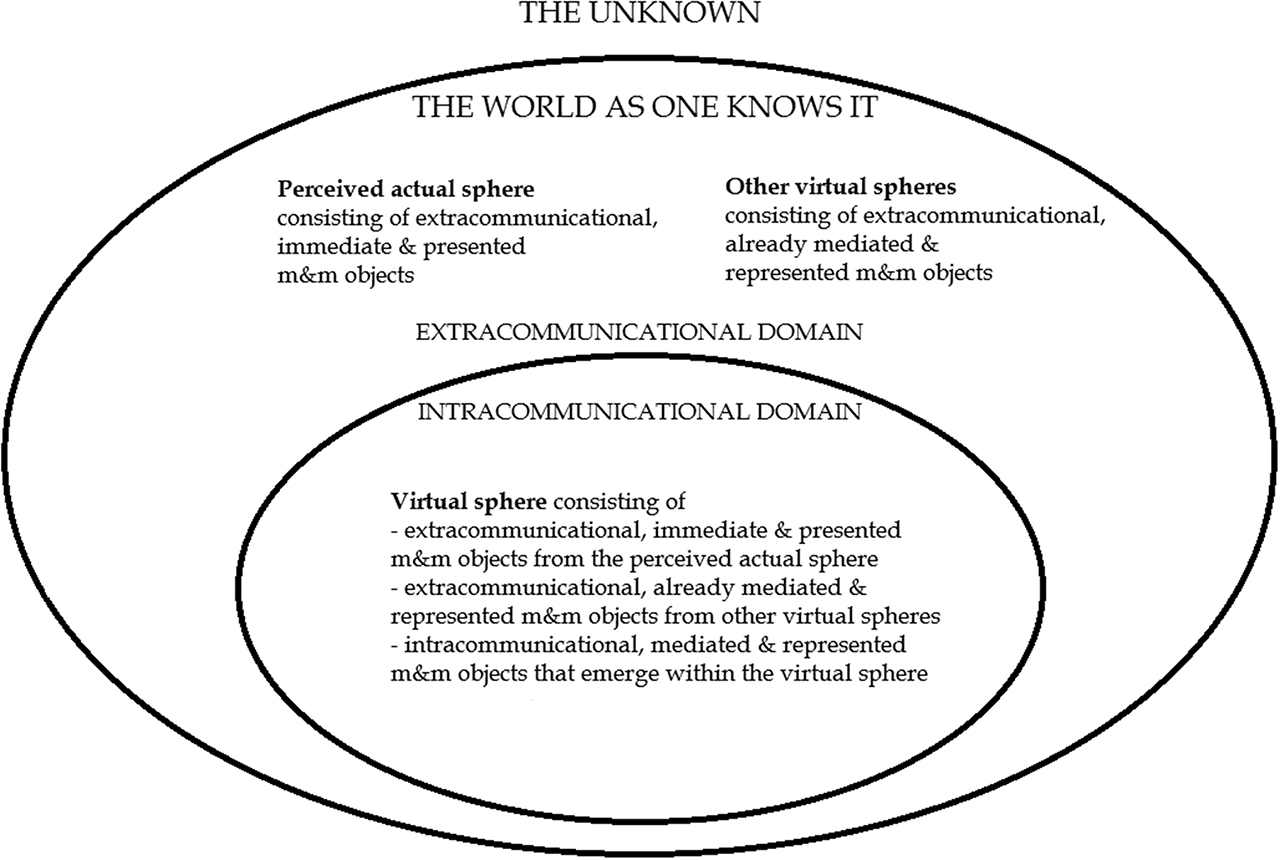

Having described the interrelations between the intracommunicational and the extracommunicational domains in some detail, it is now time to present an overview with the aid of a visual diagram (Figure 1). The main point is that whereas the intracommunicational domain simply consists of one virtual sphere, the extracommunicational domain consists of two rather different elements: on the one hand, other virtual spheres; on the other hand, what I propose to call the perceived actual sphere. From the point of view of a virtual sphere, there are thus three more or less distinct spheres: the virtual sphere itself, other virtual spheres, and the perceived actual sphere.

Virtual sphere, other virtual spheres, perceived actual sphere.

The perceived actual sphere consists of extracommunicational, immediate and presented material and mental objects beyond the realm of communication that the perceiving mind is acquainted with. “Perceived” shall be understood in a broad sense to include exteroception, interoception, and proprioception, and also to be joined with mental introspection and semiosis based on perception of the actual sphere. “Immediate and presented” shall be understood in contrast to communication: the perceived actual sphere does not consist of mediated representations formed by media products brought out by minds and their extensions, but is immediately present to us. Note that immediately present does not mean without the mediating mental mechanisms that connect sensation to perception or the complicated mediating functions that connect perception to the external world.

The other virtual spheres consist of extracommunicational, already mediated and represented material and mental objects that the perceiving mind is acquainted with. As virtual spheres are thoroughly semiotic, these objects are always made out of former interpretants. The other virtual spheres result from communication and comprise mediated representations formed by media products brought out by minds and their extensions.

Hence, the virtual sphere consists of extracommunicational, immediate and presented material and mental objects from the perceived actual sphere + extracommunicational, already mediated and represented material and mental objects from other virtual spheres + intracommunicational, mediated and represented material and mental objects that emerge within the virtual sphere.

As all schematic representations, this model is intended to give an overview of an intricate reality. It nevertheless not only points to mental areas that are fundamentally different in certain respects, but also reveals their complex interrelations. It must thus be emphasized that every virtual sphere, from the point of view of that sphere, is intracommunicational, and, hence, composed of objects that are derived from itself (to the extent that parts, combinations, and blends of extracommunicational objects may be understood as distinct), as well as from other virtual spheres and the perceived actual sphere. This comprises a mise-en-abyme: intracommunicational virtual spheres are formed by perceived actual spheres and by other, extracommunicational virtual spheres that are in turn formed by perceived actual spheres and by other, extracommunicational virtual spheres ad infinitum.

6 Varieties of contiguity

After this overview of the various spheres, we can further scrutinize indexicality with greater emphasis on its core principle of contiguity and how it operates in relation to the intracommunicational and the extracommunicational. Following Peirce, I have stated that indices are signs grounded on contiguity or real connections between representamen and object. While this is a foundational semiotic notion, little research has investigated what contiguity may actually consist of. What are real connections, on closer inspection?

It is generally assumed that real connections consist of contiguity in space or time. As they must be understood in terms of both materiality and mind-work, real connections can be established through concrete sensory perception of physical space and its temporal transformation as well as through more abstract, conceptual sensations of space and time. These two facets are deeply interconnected. Indeed, indices may arguably be said to evolve during childhood from involving material (present) objects to also connecting to mental (imagined) objects (West 2009, West 2013); from imagined objects there is only a short step to objects that are ideas or concepts rather than material entities. Given this sliding material–mental scale, it is clear that real connections may be established also between entities that differ materially and mentally. Additionally, one must remember that indices, as with other signs, are not objectively existing entities, but rather functions. Hence, contiguity, even if it is understood as real connections in time and space, may be more or less direct, unambiguous, and inter-subjective or indirect, ambiguous, and subjective. Subjective experiences are also real.

Nevertheless, there are clearly varieties of contiguity. I suggest categorization of, on the one hand, general subclasses that can be discerned as different kinds of relations between entities, and, on the other hand, specific subclasses that can be discerned as different kinds of relational channels between entities.

6.1 General subclasses of contiguity

Under the heading of general subclasses we have contiguity in a weaker sense: co-presence. Co-presence simply includes proximity, either in the sense of being adjacent (“person standing close to door”) or in the sense of being part of (“doorknob belonging to door”; “human body including hand”). We also have contiguity in a stronger sense: interaction. Interaction includes proximity and additionally causality, understood either as unidirectional (“person opening door”) or reciprocal (“person opening door that swings back and hits her in the head”).

Contiguity, as co-presence, and especially adjacency, tends toward being more indirect, ambiguous, and subjective compared to contiguity as interaction. As everything can have some sort of spatiotemporal co-presence with almost anything, there is little point in classifying these connections. The specific subclasses that are listed below are therefore primarily applicable to contiguity understood as interaction. These sorts of real connections tend to be relatively direct, unambiguous, and inter-subjective, although they are by no means independent of the human perspective on the events of the world.

6.2 Specific subclasses of contiguity

The following list of various kinds of relational channels between entities is in no way complete and there are no clear borders between the categories; the classification is merely to give a broad overview of real connections by way of illuminating examples ranging from material to mental contiguity.

Contiguity that does not include mental activities in the relational channel between entities embraces mechanical contiguity (between finger and fingerprint; between bow being drawn across strings and violin sounding); electromagnetic contiguity (between photons emitted from matter and digital photographs (see Godoy 2007); between input in computers and what is seen on the computer screens); chemical contiguity (between photons emitted from matter and classical photographs; between added heat and boiling water); and organic contiguity (between disease and observable symptoms; between dead animal and fossil).

Contiguity that includes corporeal and conscious or unconscious mental activities in the relational channel between entities holds, for instance, the combination of mental and mechanical contiguity (between the decision to use a pencil and written text; between sudden rage and the smashing of a window); and the combination of mental and organic contiguity (between emotional state and voice quality, facial expression, and body posture; between refusal to eat and sensation of hunger).

Finally, there is contiguity that merely consists of conscious or unconscious mental activities in the relational channel between entities (between sensations and assumptions; between premises and conclusions). Contiguity thus covers the field from concrete physical connections to abstract reasoning that ultimately derives from experiences of corporeal relations.

These general and specific subclasses of contiguity illuminate how both extracommunicational and intracommunicational objects become part of virtual spheres. It should be remembered, though, that even indices that build on stronger real connections, that is, interaction, and that reach out to the perceived actual sphere, represent only the world as one knows it. Not only mental, but also mechanical, electromagnetic, chemical, and organic contiguity are presumed contiguities formed by collateral experience. In the end, the extracommunicational and the intracommunicational domains are both mental.

7 Intracommunicational indexicality: Internal coherence

After identifying a large variety of contiguities forming grounds for both intracommunicational and extracommunicational indexicality, it is now time to take a closer look at the functions of intracommunicational and extracommunicational indexicality: to generate internal coherence and external truthfulness, respectively.

Intracommunicational indexicality is semiosis creating bonds within a virtual sphere, connecting representamens on the ground of contiguity to objects that are drawn into or formed inside the virtual sphere as it evolves. As the semiosis occurs within a virtual sphere, the contiguities are also virtual. Apart from being able to hold represented space and time, a virtual sphere is spatiotemporal in the sense that it is formed by more or less continuous perception and interpretation of physically more or less demarcated media products. Even if the perception is interrupted, or if parts of the media products are scattered, one has the mental capacity to (re)connect the pieces so that they represent a consistent virtual sphere. Hence, the sensation of the constituents of the media product, as well as what they represent, is that they are minimally co-present. The constituents of a virtual sphere are initially, when first being discerned, most certainly adjacent, and as perception and interpretation evolve they are often also understood to be part of each other and to interact.

As the mind strives for perceiving gestalts, one is deeply inclined to use these real connections as grounds for indices, which leads to chains and webs of representations that create coherence. If communication goes forward and makes sense, its constituents are contiguous in a stronger sense and indexicality based on causality rather than simply adjacency may result, which leads to even stronger coherence.

Internal coherence in communication may hence be defined as real connections between intracommunicational representamens and objects. But what does it mean to say that a virtual sphere is coherent? Examples of intracommunicational indexical junctions are the following: represented persons and actions appear to be generally interrelated; events and moods seem to somehow follow from another rather than occur randomly; details are apprehended as parts of discernible mental or material wholes; psychological states, ideas, and concepts are developed intelligibly; physical properties are associated to material items in a consistent way; physical and psychological actions lead to reactions that are linked to the actions; emotions are possible to understand in the context of other emotions and activities; concepts make sense considering the setting; entities and developments are felt to be proportional given the overall frame.

Indexical junctions like these, based on various sorts of contiguity, occur in all kinds of media products, whether they consist of a limited amount of material, spatiotemporal, sensorial, and semiotic modes (such as still images or written text) or are markedly multimodal (such as movies that are both spatial and temporal, visual and auditory, and iconic and symbolic). An important role of intracommunicational indexicality is hence to knit together the different modes of a media product through cross-modal representation, so that an integrated virtual sphere, rather than a set of unrelated, mode-specific mental spheres, can be created.

8 Extracommunicational indexicality: External truthfulness

In contrast, extracommunicational indexicality is semiosis creating bonds between a virtual sphere and its surroundings, connecting representamens on the ground of contiguity to objects from outside the virtual sphere. I suggest this is external truthfulness in communication, which may hence be defined as real connections between intracommunicational representamens and extracommunicational objects. The notion of truthfulness that I propose is thus to be understood as a conceived communicative trait, not to be confused with truth, understood as a feature of the actual, never fully accessible world. However, truth may possibly be approached through accumulated truthful communication and the observation of effects of further action on the basis of conceived truthfulness.

To what can communication be truthful, more precisely? I suggest that extracommunicational indexical objects can be classified variously, each category corresponding to a certain kind of truthfulness. I will here give some prominent examples of such forms of objects and truthfulness. It is not a rigid classification, but rather an incomplete inventory of types that sometimes overlap, sometimes complement each other, and sometimes are in conflict. I do not at all advise that they should be treated as categories for compartmentalization; they are rather flexible groupings for methodical investigations of truthfulness in communication.

Following the division of the extracommunicational domain into two parts we may state that a virtual sphere can be truthful to objects in the perceived actual sphere or to objects in other virtual spheres; to our notions of the surrounding world or to our acquaintance with earlier communication. In turn, earlier communication may be truthful to objects in the perceived actual sphere or to objects in other virtual spheres. The notion that there may be truthful representations of other virtual spheres that do not represent the perceived actual sphere has previously been discussed in terms of making truthful performances and statements about so-called fictional characters (Colapietro 2009: 117; Searle 1975: 329).

Our previous discussion of indexical objects also testifies that a virtual sphere can be truthful to objects that are material or that are mental. This is a crucial and, in a way, self-evident, but often neglected observation. According to my view, a concept of truthfulness only including real connections to materially observable states is perhaps easier to manage, but of little use.

Connecting to an age-old distinction of Aristotle, we can furthermore say that a virtual sphere can be truthful to objects that are (more or less) universal or those that are particular (Aristotle 1997 [c. 330 BCE]: 81; cf. Gale 1971: 335; Gallagher 2006: 341–343; Walton 1983: 80). Some variations of this distinction would be to say that a virtual sphere can be truthful to objects that are typical or atypical; permanent or temporary; and global or local. This could perhaps be understood as a sort of statistical view on truthfulness, having to do with probability of repeated contiguity in various environments and circumstances; truthfulness as a function of certain ways of framing the extracommunicational domain.

In a related manner, a virtual sphere can be truthful to objects that are wholes or to objects that are details (cf. Pavel 1986: 17). Truthfulness in detail does not guarantee a truthful whole and a truthful whole may harbor non-truthful details. This is truthfulness understood as perception of gestalts; truthfulness emanating from (in)attention to (absence of) singular real connections when construing the overall pattern of contiguity.

An important but more complex way of sorting extracommunicational indexical objects, partly coinciding with some of the earlier categories, is that a virtual sphere can be truthful to objects that have previously been manifested, that are presently manifested, that are bound to be manifested, or that may be manifested (cf. the notion of “possible worlds” in Pavel 1986: 46). One may perhaps even argue that a virtual sphere can be truthful to objects that ought to be manifested. These latter forms of truthfulness rely heavily on mental contiguity.

In this context, it must also be noted that any material item can be drawn into the communicative act and become a media product interacting with other media products or creating highly multimodal joint media products. In trials, for instance, fingerprints and other pieces of evidence are framed such that they communicate with standard media such as speech, written text, still images, movies, and sound recordings that incorporate them in order to create a virtual sphere based on strong contiguity to the perceived actual sphere. Thus, all varieties of contiguity, all kinds of intracommunicational indexical junctions, and all types of extracommunicational indexical objects pertain to external truthfulness in communication. This abundance demonstrates the complexity of forming coherent virtual spheres with real extracommunicational connection. There is, however, one factor that deserves special attention: the communicating mind.

9 Communicating minds warranting internal coherence and external truthfulness

Communication, as defined in this article, is about transferring cognitive import among minds. Therefore, the notion of communicating mind, for the moment understood as the mind of the producer of cognitive import, not the perceiver, is germane. In related but clearly different ways, it is central for conceiving both the intracommunicational and extracommunicational domains. To a certain extent, communicating minds are responsible for both internal (in)coherence and external (un)truthfulness. This comes about through representation. Communicating minds are made present to the mind of the perceiver via representamens of the media products and they may be objects in the virtual sphere itself, in other virtual spheres, and in the perceived actual sphere.

9.1 Perceived actual communicating mind

The starting point for this inquiry is the plain but fundamental observation that communicating minds, producing some cognitive import to be perceived via media products, do not simply disappear behind the virtual spheres created in the perceivers’ minds. In many situations, the communicating mind is decidedly represented by the media product and hence becomes part of the virtual sphere. In an ordinary conversation, for instance, the word “I” is often understood as an index, based on strong contiguity in actual space and time, for the communicating mind in the perceived actual sphere using her body and its extensions as media products when uttering the word. To the extent that anything can be established at all, this is a determinable communicating mind that can even be engaged in two-way communication. In other situations, the communicating mind may be much more distant in both space and time and sometimes, such as when one looks at ancient rock-paintings, the producer’s mind is not at all accessible and can only be construed as an idea of something that must have existed at some point. The painting becomes an index based on weak contiguity consisting of the notion that someone must have produced the visual configurations through actions of mind and hand. In any case, communicating minds are always, if they are parts of the perceived actual sphere, perceived actual producers’ minds.

Represented communicating minds that originate from the perceived actual sphere are objects that in various degrees warrant external truthfulness. Their existence in and collateral experiences of certain parts of the perceived actual sphere make it plausible that certain aspects of the communicated cognitive import are more or less truthful. Of course, the representation of communicating minds in the perceived actual sphere is not in itself a guarantee for complete truthfulness (for instance, there are factors such as forgetfulness, misconceptions, and lies that disconnect parts of the intracommunicational domain from the extracommunicational domain), but collateral experience of communicating minds makes it possible to partly decide upon the amount of contiguity that is present. This is an immensely complex issue that cannot be developed further for the moment; here I only want to stress that communicating minds are central extracommunicational objects; although their roles may vary considerably, they are always, at a minimum, necessary links to the perceived actual sphere.

9.2 Virtual communicating mind

Apart from representing communicating minds in the perceived actual sphere, media products may also represent those that emerge within the virtual sphere. As all intracommunicational objects, virtual communicating minds are ultimately construed by extracommunicational objects, which means that they may well be similar to perceived actual communicating minds. Nevertheless, perceivers of media products who have no knowledge of, access to, or interest in the actual producers tend to construe virtual spheres that include virtual communicating minds so that they are comprehensible as communicative entities. The craving for internal coherence can hence be achieved with the aid of virtual communicating minds: odd details, vague connections, and apparent inconsistencies may be knit together through the representation of virtual communicating minds having certain ideas, purposes, and peculiarities.

The notion of virtual communicating minds matches quite well with what has long been known in literary theory as “implied authors” (Booth 1961), although the scope of virtual communicators is of course much larger, including all kinds of communication and not only written texts of a certain kind. Literary theory has also suggested a broad range of internal mediating agents with more restricted responsibilities and capabilities compared to the implied author. These agents are generally called focalizers (restricting the communicated to the scope of what certain characters know, see, or hear) or narrators, with various prefixes (agents that are responsible for communicating within the overall frame of the virtual sphere). As the notion of narrator has been used mainly for media types including verbal language, the term “monstrator” has been suggested for denoting a corresponding notion for visual iconic media types (Gaudreault 2009 [1988]). These agents are intracommunicational objects that can be combined in various and sometimes complex ways. They have in common the function of interconnecting the parts of a virtual sphere so that compound virtual spheres can also be understood as wholes.

In addition, a virtual sphere may represent a multitude of agents from other virtual spheres: perceived actual communicating minds, virtual communicating minds, and indeed also internal mediating agents such as narrators. They are all extracommunicational objects that can be incorporated in a virtual sphere in intricate ways.

10 Truthfulness in so-called fiction

To close this article, I will put external truthfulness in relation to the contrasting notions of fiction and fictionality. Fictionality is normally understood as a supposed (at least partial) quality of certain media types labeled fictions – “novel, short story, graphic novel, fiction film, television serial fiction, and so on” (Nielsen et al. 2015: 62; cf. Searle 1975: 332) – and pertaining to representation of invented, unreal, and purely imaginary objects.

In other words, fictionality is supposedly not representation of objects from the perceived actual sphere, but solely of objects from the virtual sphere or other virtual spheres that do not represent the perceived actual sphere. This notion runs into trouble when considering that all intracommunicational objects ultimately rely on extracommunicational objects, although they emerge within the intracommunicational domain and may gain a sort of autonomy by way of being perceived as new gestalts. A minimal conclusion of this observation is that fictionality is very difficult to circumscribe because of the floating borders between extracommunicational objects and new intracommunicational gestalts. A more drastic conclusion is that there is no specific quality of fictionality, only sorts and degrees of truthfulness. Fictionality, if the notion is to be kept at all, should thus not be understood as a distinct feature, but as a lack of certain sorts of truthfulness. In effect, this renders the notion of fictionality superfluous and oppositions such as truthfulness–fictionality misleading. I hence argue that truthfulness and so-called fictionality are not two contrary qualities; rather, they represent different grades on the same scale. Abandoning the notion of fictionality rids us of heavy, but empty ballast and leaves us with a homogenous but indeed very complex notion of sorts and degrees of truthfulness.

If the notion of fictionality is deserted, what is then left of fiction, which is supposedly based on fictionality? Under all circumstances, it is clear that one cannot make “a categorical distinction” between fiction and nonfiction (Yadav 2010: 191; cf. Ryan 1991). Nonfiction, if the notion is to be kept in academic discourse, must be understood as a range of media types that are expected to have certain kinds of truthfulness. Fiction, an equally problematic notion, would then be a range of media types that are expected to lack certain kinds of truthfulness. However, this does not eliminate the condition that there is truthfulness in both fiction (including media types such as novels, animated cartoons, and ballads) and nonfiction (such as documentary films, scientific articles, and oral testimonies). This has been acknowledged in various ways by several scholars who otherwise differ in their conceptions and terminology (for instance, D’Alessandro 2016; Gale 1971; Grishakova 2008; Harshaw 1984; Ronen 1988; Ryan 1980; Searle 1975).

Because I find this conception of fiction versus nonfiction very coarse and unnecessarily cumbersome, I think it gives a better understanding of the varieties of truthfulness in communication if each media type is investigated on a more fine-grained scale regarding expected truthfulness in terms of different kinds of contiguity and different kinds of extracommunicational indexical objects. Let me illustrate this with some observations of a few media types from the historical and cultural perspective in which the author of this article is situated.

Television news programs are expected to be strongly truthful in a variety of ways. They should preferably include photographs or film footage produced by electromagnetic or chemical contiguity. They should certainly be truthful to objects in the perceived actual sphere, but also to objects in other virtual spheres, meaning that earlier communication must be correctly reported. Programs also ought to have real connections to both material and mental objects; not only to persons, places, and events, but also to objects such as ideas and emotions. Both wholes and details are expected to appear correctly. Importantly, these programs are expected to truthfully represent objects that are particular, regardless of their degree of universality, which means that also atypical and temporary rather than permanent objects are part of their norm. Furthermore, they should definitely be equally truthful to objects that have been manifested and those that are presently manifested – and, if possible, to objects that may or are bound to be manifested.

In contrast, historical paintings are expected to be strongly truthful in some ways and less truthful in others. To be counted as part of this media type, a media product should be produced by mental and mechanical contiguity by a person possessing relevant collateral experience. A historical painting ought to be truthful to mainly material, visual objects. Although the quality of universality is certainly possible to include, it is first of all expected to have real connections to objects particular to a certain time and place. It is foreseen to be truthful to both wholes and details, although the very smallest details are often counted out. While the primary norm is to truthfully represent objects that have been manifested, this might well be combined with truthful representation of objects that may be manifested according to the idea that history can repeat itself.

A third example is science fiction novels that are expected to be more or less truthful in still other ways compared to news reports and historical paintings. To a certain extent, they should be truthful to objects in other virtual spheres, meaning that their own should preferably correspond to other science fiction in order to make sense. Most readers probably anticipate their representing more or less universal objects; to be stories that say much about things in general and globally. Of course, this does not exclude truthful representations of atypical and spectacular objects. Naturally, science fiction novels are first of all expected to be truthful to objects that may be, and perhaps to some extent ought or ought not to be, manifested in the future.

My claim here is not that the sketched expectations of a handful of media types are accurate, but rather that there are various and shifting anticipations of these kinds that are important for construing media types. This is to say that different media types and submedia, or genres, are often qualified exactly regarding expected presence or absence of various sorts of extracommunicational truthfulness (Elleström 2010); media types are partially defined by the very kinds of truthfulness in the media products that constitute them (cf. Wildekamp et al. 1980: 556). Media type attributions such as “this is a dinner conversation, but that is a legal testimony” can thus be understood as truth claims. Additionally, expected or even required varieties of truthfulness and non-truthfulness are often envisaged to go hand-in-hand with certain styles and other media hallmarks. In the end, however, qualified media types are certainly not stable entities, but important pragmatic categories that vary through history, ideologies, and cultures. Mapping such manifold diversities is necessary for transcending the all too coarse fiction–nonfiction distinction.

11 Conclusion

I have elaborated a new approach to some fundamental issues of communication, effected in a way that includes all conceivable kinds of media. The resulting model suggests that the outcome of communication is, minimally, a virtual sphere in the mind of the perceiver. This virtual sphere is constituted by objects (understood in a semiotic sense) emanating from the perceived actual sphere and from other virtual spheres, but also by objects that emerge within the virtual sphere. I have argued, however, that such intracommunicational objects are ultimately derived from extracommunicational objects originating from other virtual spheres and the perceived actual sphere.

On the basis of this conception, I have claimed that there are two main functions of indices in communication. Indices based on contiguity or real connections, on the one hand, generate internal coherence in the virtual sphere; on the other hand, they create external truthfulness in linking the intracommunicational and extracommunicational domains. In contrast to other sign types, which may indeed correctly correspond to the extracommunicational, indices are those signs that actually establish truthfulness.

As there are many subclasses of contiguity, internal coherence may be created in numerous ways. Nevertheless, the notion of internal coherence in a virtual sphere is vital for further development of the notion of narration (see Elleström forthcoming), which has only been hinted upon here. More efforts have been made to demonstrate not only that there are several varieties of contiguity, but also that virtual spheres can be truthful to a broad diversity of extracommunicational objects. Observing these two multi-faceted factors simultaneously has made it possible to suggest the contours of an immensely nuanced conception of degrees and varieties of (missing) external truthfulness. Such a conception, I have maintained, makes the notion of fictionality superfluous as it is arguably simply equivalent to a lack of certain sorts of truthfulness.

I have also sustained the view that truth claims can be made by media type attributions. One of many functions of categorizing media is to indicate what kinds of external truthfulness can be expected from certain media products. However, coarse classifications such as fiction versus nonfiction distort the perception of fine-grained differences in external truthfulness.

References

Aristotle,. 1997. [c. 330 BCE]. Aristotle’s poetics. John Baxter & Patrick Atherton (eds.), George Whalley (trans.). Montreal: McGill-Queen’s University Press.Search in Google Scholar

Atkin, Albert. 2005. Peirce on the index and indexical reference. Transactions of the Charles S. Peirce Society 41(1). 161–188.Search in Google Scholar

Bergman, Mats. 2009. Experience, purpose, and the value of vagueness: On C. S. Peirce’s contribution to the philosophy of communication. Communication Theory 19. 248–277.10.1111/j.1468-2885.2009.01343.xSearch in Google Scholar

Booth, Wayne C. 1961. The rhetoric of fiction. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.Search in Google Scholar

Brewer, William F. 1987. Schemas versus mental models in human memory. In Peter Morris (ed.), Modelling cognition, 187–197. Oxford: Oxford University Press.Search in Google Scholar

Burke, Tom. 1991. Peirce on truth and partiality. In Jon Barwise, Jean Mark Gawron, Gordon Plotkin & Syun Tutiya (eds.), Situation theory and its applications, Vol. 2, 115–146. Stanford: Center for the Study of Language and Information.Search in Google Scholar

Colapietro, Vincent. 2009. Pointing things out: Exploring the indexical dimensions of literary texts. In Harri Veivo, Christina Ljungberg & Jørgen Dines Johansen (eds.), Redefining literary semiotics, 109–133. Newcastle upon Tyne: Cambridge Scholars Press.Search in Google Scholar

D’Alessandro, William. 2016. Explicitism about truth in fiction. British Journal of Aesthetics 56. 53–65.10.1093/aesthj/ayv031Search in Google Scholar

Elleström, Lars. 2010. The modalities of media: A model for understanding intermedial relations. In Lars Elleström (ed.), Media borders, multimodality, and intermediality, 11–48. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.10.1057/9780230275201_2Search in Google Scholar

Elleström, Lars. 2014. Material and mental representation: Peirce adapted to the study of media and arts. American Journal of Semiotics 30. 83–138.10.5840/ajs2014301/24Search in Google Scholar

Elleström, Lars. 2018. A medium-centered model of communication. Semiotica 224. 269–293.10.1515/sem-2016-0024Search in Google Scholar

Elleström, Lars. Forthcoming. Transmedial narration: Narratives and stories in different media. Houndmills: Palgrave Macmillan.Search in Google Scholar

Gale, Richard M. 1971. The fictive use of language. Philosophy 46. 324–340.10.1017/S003181910001696XSearch in Google Scholar

Gallagher, Catherine. 2006. The rise of fictionality. In Franco Moretti (ed.), The novel, vol. 1: History, geography, and culture, 336–363. Princeton: Princeton University Press.10.1515/9780691243757-018Search in Google Scholar

Gaudreault, André. 2009 [1988]. From Plato to Lumière: Narration and monstration in literature and cinema. Timothy Barnard (trans.). Toronto: University of Toronto Press.10.3138/9781442688148Search in Google Scholar

Godoy, Hélio. 2007. Documentary realism, sampling theory and Peircean semiotics: Electronic audiovisual signs (analog or digital) as indexes of reality. Doc On-Line 2. 107–117.Search in Google Scholar

Goudge, Thomas A. 1965. Peirce’s index. Transactions of the Charles S. Peirce Society 1(2). 52–70.Search in Google Scholar

Grishakova, Marina. 2008. Literariness, fictionality, and the theory of possible worlds. In Lars-Åke Skalin (ed.), Narrativity, fictionality, and literariness: The narrative turn and the study of literary fiction, 57–76. Örebro: Örebro University Press.Search in Google Scholar

Harshaw, Benjamin. 1984. Fictionality and fields of reference: Remarks on a theoretical framework. Poetics Today 5. 227–251.10.2307/1771931Search in Google Scholar

Hookway, Christopher. 2000. Truth, rationality, and pragmatism: Themes from Peirce. Oxford: Clarendon Press.Search in Google Scholar

Howat, Andrew W. 2015. Hookway’s Peirce on assertion & truth. Transactions of the Charles S. Peirce Society 51(4). 419–443.10.2979/trancharpeirsoc.51.4.03Search in Google Scholar

McCarthy, Jeremiah. 1984. Semiotic idealism. Transactions of the Charles S. Peirce Society 20(4). 395–433.Search in Google Scholar

Nesher, Dan. 1997. Peircean realism: Truth as the meaning of cognitive signs representing external reality. Transactions of the Charles S. Peirce Society 33(1). 201–257.Search in Google Scholar

Pavel, Thomas G. 1986. Fictional Worlds. Cambridge MASS: Harvard University Press.Search in Google Scholar

Peirce, Charles Sanders. 1931–1958. Collected papers of Charles Sanders Peirce, Vol. 1–8, C. Hartshorne, P. Weiss & A. W. Burks (eds.). Cambridge: Harvard University Press. [Reference to Peirce’s papers will be designated CP followed by volume and paragraph number.].Search in Google Scholar

Ronen, Ruth. 1988. Completing the incompleteness of fictional entities. Poetics Today 9. 497–514.10.2307/1772729Search in Google Scholar

Ryan, Marie-Laure. 1980. Fiction, non-factuals, and the principle of minimal departure. Poetics 9. 403–422.10.1016/0304-422X(80)90030-3Search in Google Scholar

Ryan, Marie-Laure. 1984. Fiction as a logical, ontological, and illocutionary issue. Style 18. 121–139.Search in Google Scholar

Ryan, Marie-Laure. 1991. Possible worlds, artificial intelligence, and narrative theory. Bloomington and Indianapolis: Indiana University Press.Search in Google Scholar

Searle, John R. 1975. The logical status of fictional discourse. New Literary History 6. 319–332.10.2307/468422Search in Google Scholar

Nielsen, Skov, James Phelan Henrik & Richard Walsh. 2015. Ten theses about fictionality. Narrative 23. 61–73.10.1353/nar.2015.0005Search in Google Scholar

Stjernfelt, Frederik. 2014. Natural propositions: The actuality of Peirce’s doctrine of Dicisigns. Boston MA: Docent Press.10.1007/s11229-014-0406-5Search in Google Scholar

Walton, Kendall L. 1983. Fiction, fiction-making, and styles of fictionality. Philosophy and Literature 7. 78–88.10.1353/phl.1983.0004Search in Google Scholar

West, Donna E. 2009. Indexical reference to absent objects. Chinese Semiotic Studies 6. 280–294.10.5840/cpsem20108Search in Google Scholar

West, Donna E. 2013. Cognitive and linguistic underpinnings of Deixis am Phantasma: Bühler’s and Peirce’s semiotic. Sign Systems Studies 41. 21–41.10.12697/SSS.2013.41.1.02Search in Google Scholar

Wildekamp, Ada, Ineke van Montfoort & Willem van Ruiswijk. 1980. Fictionality and convention. Poetics 9. 547–567.10.1016/0304-422X(80)90006-6Search in Google Scholar

Yadav, Alok. 2010. Literature, fictiveness, and postcolonial criticism. Novel 43. 189–196.10.1215/00295132-2009-081Search in Google Scholar

© 2018 Elleström, published by De Gruyter

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Genome as (hyper)text: From metaphor to theory

- The work of Peirce’s Dicisign in representationalizing early deictic events

- The double function of the interpretant in Peirce’s theory of signs

- Integration mechanism and transcendental semiosis

- The communicative wheel: Symptom, signal, and model in multimodal communication

- Discursive representation: Semiotics, theory, and method

- Translation as sign exploration: A semiotic approach based on Peirce

- When does the ritual of mythic symbolic type start and when does it end?

- Iconoclasms of Emmett Till and his killers in Lewis Nordan’s Wolf Whistle: A new generation of historiographic metafiction

- A dialogical semiosis of traveling narratives for self-interpretation: Towards activity-semiotics

- Entre éthologie et sémiotique : Mondes animaux, compétences et accommodation

- A pentadic model of semiotic analysis

- Linguistic violence and the “body to come”: The performativity of hate speech in J. Derrida and J. Butler

- Cultural tourism as pilgrimage

- A simple traffic-light semiotic model for tagmemic theory

- From resistance to reconciliation and back again: A semiotic analysis of the Charlie Hebdo cover following the January 2015 events

- Bilingual and intersemiotic representation of distance(s) in Chinese landscape painting: from yi (‘meaning’) to yi (‘freedom’)

- Power-organizing and Ethic-thinking as two paralleled praxes in the historical existence of mankind: A semiotic analysis of their functional segregation

- Semiosic translation

- Construction of new epistemological fields: Interpretation, translation, transmutation

- A biosemiotic reading of Michel Onfray’s Cosmos: Rethinking the essence of communication from an ecocentric and scientific perspective

- Coherence and truthfulness in communication: Intracommunicational and extracommunicational indexicality

- Poetic logic and sensus communis

- Intrinsic functionality of mathematics, metafunctions in Systemic Functional Semiotics

- Ciudadanos: The myth of neutrality

- Multilingualism and sameness versus otherness in a semiotic context

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Genome as (hyper)text: From metaphor to theory

- The work of Peirce’s Dicisign in representationalizing early deictic events

- The double function of the interpretant in Peirce’s theory of signs

- Integration mechanism and transcendental semiosis

- The communicative wheel: Symptom, signal, and model in multimodal communication

- Discursive representation: Semiotics, theory, and method

- Translation as sign exploration: A semiotic approach based on Peirce

- When does the ritual of mythic symbolic type start and when does it end?

- Iconoclasms of Emmett Till and his killers in Lewis Nordan’s Wolf Whistle: A new generation of historiographic metafiction

- A dialogical semiosis of traveling narratives for self-interpretation: Towards activity-semiotics

- Entre éthologie et sémiotique : Mondes animaux, compétences et accommodation

- A pentadic model of semiotic analysis

- Linguistic violence and the “body to come”: The performativity of hate speech in J. Derrida and J. Butler

- Cultural tourism as pilgrimage

- A simple traffic-light semiotic model for tagmemic theory

- From resistance to reconciliation and back again: A semiotic analysis of the Charlie Hebdo cover following the January 2015 events

- Bilingual and intersemiotic representation of distance(s) in Chinese landscape painting: from yi (‘meaning’) to yi (‘freedom’)

- Power-organizing and Ethic-thinking as two paralleled praxes in the historical existence of mankind: A semiotic analysis of their functional segregation

- Semiosic translation

- Construction of new epistemological fields: Interpretation, translation, transmutation

- A biosemiotic reading of Michel Onfray’s Cosmos: Rethinking the essence of communication from an ecocentric and scientific perspective

- Coherence and truthfulness in communication: Intracommunicational and extracommunicational indexicality

- Poetic logic and sensus communis

- Intrinsic functionality of mathematics, metafunctions in Systemic Functional Semiotics

- Ciudadanos: The myth of neutrality

- Multilingualism and sameness versus otherness in a semiotic context