Abstract

We conduct a laboratory experiment to analyze the influence of whistleblower protection on the cooperative behavior between a manager and an employee. Before taking part in a trust game with her employee, a manager has the opportunity to embezzle money at the expense of a third party. The employee observes her decision and may trigger an investigation by blowing the whistle. The treatments vary with respect to immunity and anonymity for the whistleblower. We compare misbehavior, reporting, and cooperative behavior across the treatments. The results suggest that whistleblower protection could deter wrongdoing, but could also have a detrimental effect on cooperation in organizations if it increases the probability for whistleblowing.

1 Introduction

In the recent past, a number of large firms severely suffered from the consequences of exposed corporate fraud (e.g. Enron, Wirecard and Volkswagen). As fraud has detrimental effects on many involved stakeholders (see e.g., Yu 2013; Dyck, Morse, and Zingales 2024), reducing fraudulent behavior is generally desirable. One potential source for revealing corporate fraud is whistleblowing (see e.g., Dyck, Morse, and Zingales 2010). However, being exposed to retribution or suffering from an eroded work environment after exposing managerial wrongdoing renders blowing the whistle rather unattractive. Furthermore, once a norm of unethical behavior has been established, the corroding effect of malfeasance can spread through entire institutions or companies (see e.g., Ajzenman 2021; Huber et al. 2023). Providing legal protection could reduce negative effects for the whistleblower and, thereby, could increase the rate of exposed corporate fraud. This paper experimentally investigates the behavioral effects of protection for whistleblowers in the form of immunity and anonymity. The results suggest that increasing the legal protection for whistleblowers increases the willingness to expose fraud. As a consequence, managers are less likely to engage in fraudulent behavior. However, increasing the willingness to blow the whistle also seems to decrease productive cooperation as trust between manager and employee declines.

Becoming a whistleblower comprises a non-negligible trade-off for an employee. The fear of retaliation, e.g., a dismissal or a denied promotion, is a major obstacle that often thwarts whistleblowing (see e.g., Near and Miceli 1986; Alford 2001; Cassematis and Wortley 2013). Therefore, whistleblowers might be encouraged to come forward by legally protecting them from retaliation. To this end, international organizations (see e.g., OECD 2016) requested protection for whistleblowers. The most-frequent features of whistleblower protection are immunity, which means to guarantee income (see e.g., Kohn, Kohn, and Colapinto 2004, p. 97), and anonymous reporting (see e.g., Thüsing and Forst 2016).

However, these legal approaches are discussed controversially, since the support of whistleblowers might come at a cost. Whistleblowing laws often condition the protection not on conclusive proof for the allegations, but require the whistleblower only to demonstrate a “reasonable belief” (Kohn, Kohn, and Colapinto 2004, p. 92). While obviously unfounded complaints are deterred with this standard,[1] an adverse effect may nevertheless be an increase in false claims. That means an employee blows the whistle to be protected from a dismissal, although there was no misbehavior by his employer (see e.g., Callahan and Dworkin 1992; Howse and Daniels 1995; Givati 2016). Such false claims would cause financial, or reputational, damage from investigations for the organization and increase the costs for authorities to screen claims with respect to their adequacy (see e.g., Mechtenberg, Muehlheusser, and Roider 2020).

Moreover, the efficient work within an organization relies on productive cooperation, which requires a sufficient level of trust.[2] Employees might jeopardize this trust if they use their insider status to report the employer. While a report could be beneficial for altruistic reasons (i.e. protecting a third party from harm; see e.g., Bartuli, Mir Djawadi, and Fahr 2016; Heyes and Kapur 2009), or financial reasons if reporting is incentivized (Nyreröd and Spagnolo 2021), refraining from a report could demonstrate loyalty and let the employee appear more trustworthy. In consequence, the employee’s decision to blow the whistle depends on several parameters that may vary between involved individuals and the specific case of malfeasance. Strong moral values of the employee will make whistleblowing more likely, a close relationship to the manager will decrease it’s probability. Increasing whistleblower protection won’t have much influence on either moral values or the relationship towards the manager. However, stronger protection will influence those employees in the middle ground, who would not report wrongdoing without feeling protected but are also not kept back by personal relations to the manager. Hence, by influencing all but the extreme cases with increased protection, the willingness to blow the whistle is likely to increase. This, however, will decrease the level of trust between manager and employee which can have detrimental effects on cooperation (see e.g., Dworkin and Near 1997; Vinten 1994; Walters 1975). Declining cooperation will decrease productivity. Therefore, the overall effect of whistleblower protection on social welfare is not entirely clear.

To study the relationship between whistleblower protection and the cooperative climate,[3] we created a lab experiment in which an employee can report wrongdoing of his manager who subsequently decides whether to cooperate with the employee.[4] At the beginning of a period, the manager has the opportunity to embezzle money and increase her payoff at the expense of a third party. The employee observes her choice. While the embezzlement does not affect the employee’s payoff, he can become a whistleblower and trigger an investigation by reporting misbehavior to an authority. In contrast to other studies (see e.g., Mechtenberg, Muehlheusser, and Roider 2020), we model the authority to respond perfectly to a report, which reflects the standard of a reasonable belief. In consequence, the manager can tell from an investigation that the whistle was blown. If the employee files a report, the manager suffers a cost from the investigation and has to pay a fine if she had embezzled. At the end of a period, the manager and the employee interact in a modified version of the trust game (Berg, Dickhaut, and McCabe 1995). As the sender, the manager decides first which amount to send to her employee or to take from her employee’s endowment. In this respect, the game is similar to the moonlighting game (Abbink, Irlenbusch, and Renner 2000). If she sends a positive amount, productive cooperation takes place. That means the amount is multiplied, and the employee can decide which fraction he wants to return. If the manager takes some of the endowment of her employee (i.e., beneficial cooperation does not take place), the amount is simply transferred.

Compared to a baseline treatment without protected whistleblowing (B), the employees are protected by either immunity (I), or anonymity (A), or both (AI). Immunity means that the manager cannot take any of the employee’s endowment if the employee filed a report. Recent experimental economics literature provides broad evidence that monetary incentives increase the willingness to report for potential whistleblowers (see e.g., Butler, Serra, and Spagnolo 2020; Mechtenberg, Muehlheusser, and Roider 2020; Schmolke and Utikal 2025). Anonymity allows the employee to report without revealing his action prior to the trust game to the manager. Therefore, the manager cannot condition her cooperation on the employee’s reporting decision (see e.g., Mir Djawadi 2019; Reuben and Stephenson 2013, for evidence from laboratory experiments that managers retaliate against known whistleblowers).

We derive our hypotheses from a model that assumes that a manager does not know whether she faces a loyal or disloyal employee. While both employee types suffer moral costs from embezzlement by the manager, they differ in how much they are affected by disloyal actions towards her. Compared to a loyal employee, a disloyal employee has lower moral costs from not reciprocating trust, or from reporting wrongdoing of the manager. Consequently, a manager rather wants to cooperate with a loyal employee. The manager can expect that the trust is reciprocated and the cooperation pays off, while a disloyal employee would not reciprocate the trust. The intuition of the model is as follows: If the reporting decision of the employee would perfectly reveal his loyalty type, the manager would not cooperate if she witnesses a report. If this holds, a loyal employee would not report the manager. The anticipated benefits from cooperation outweigh the costs from undetected embezzlement. A disloyal employee, however, would put more weight on the moral costs from the undetected embezzlement and report his manager. Therefore, embezzlement allows the manager to screen the type of her employee. Immunity for a whistleblower would make reported embezzlement more costly for the manager. In consequence, there would be less embezzlement and therefore less screening of the employees. With anonymous reporting, the manager cannot identify the type of the employee and has to make her decision on cooperation based on her belief about the probability to face a loyal type.

In the context of whistleblowing, a laboratory approach has two major advantages compared to the field. First, only detected misbehavior is observable in actual organizations, such that the true amount of misbehavior remains unknown. Second, we only observe reporting behavior conditional on misbehavior. That means we can account for truthful reporting when there is misbehavior and for false reporting if there is none, but not for the hypothetical behavior in the state that has not been realized. In addition, a number of studies show a high out of lab correlation in unethical behavior (see e.g., Abeler, Nosenzo, and Raymond 2019).

The results show that whistleblower protection increases honest reporting and, in turn, reduces embezzlement. At the same time, it provokes adverse incentives for the employees and leads to an increase in false whistleblowing. For the managers’ willingness to cooperate, we find a positive influence of unreported embezzlement. As embezzlement is mostly deterred in treatment AI, where protection features both immunity and anonymity, unreported embezzlement does not occur, which drives down cooperation significantly.

The remainder of the paper is organized as follows: Section 2 reviews the related literature, Sections 3 and 4 present the experimental design and the behavioral predictions, while Section 5 and 6 present and discuss the results.

2 Related Literature

As this study investigates the relation of whistleblowing and cooperation, it contributes to the literature on the effectiveness of whistleblowing and whistleblower protection. Recent studies have used laboratory experiments to test how potential whistleblowers respond to protection in the form of incentives. Schmolke and Utikal 2025 find that fines for non-reporting, rewards, and commands increase the probability of whistleblowing. Moreover, reporting is more likely if the misconduct affects the whistleblowers themselves, or the enforcement authority. Butler, Serra, and Spagnolo (2020) investigate the effect of monetary rewards on whistleblowing in the presence of potential crowding out of intrinsic motivation. They find an enhancing effect of monetary rewards on the willingness to report and no evidence for substantial crowding out of non-monetary motivations. In a field experiment, however, Fiorin (2023) finds that employees in the education system are less willing to blow the whistle on their peers’ absence once it is incentivized and if there are consequences for the wrongdoer.

Furthermore, studies have found mixed evidence on the effect of whistleblowing on the efficiency within organizations. In a theoretical model, Friebel and Guriev (2012) show that the possibility for whistleblowing might harm a firm’s productive efficiency if wrongdoers “bribe” other members of the organization as this could undermine effort incentives. Felli and Hortala-Vallve (2016) provide a model in which incentivized whistleblowing can prevent opportunistic behavior that takes the form of collusion or blackmail between supervisors and employees.

Mechtenberg, Muehlheusser, and Roider (2020) consider both the effectiveness and the efficiency of whistleblower protection. They investigate the effects of whistleblower protection on reporting and on the efficiency of law enforcement in a theory-guided lab experiment. Their findings show that when the legal protection provokes false reporting, whistleblowing becomes a less informative signal such that more reports do not necessarily materialize in more investigations. Since the employees are externally heterogeneous with respect to their productivity, a dismissal could be driven either by efficiency concerns or by preferences for retaliation.

We complement these studies by considering the connection of the effectiveness of whistleblower protection and the efficiency of whistleblowing within the organization. This study features the effect of protected whistleblowing on the reporting behavior and deterrence as well. Moreover, we add a dimension that captures the effect of whistleblowing on efficient cooperation. More precisely, the reporting decision is a possibility to signal trustworthiness to the organization, which is crucial for cooperation to take place. Therefore, by deterring misbehavior, whistleblower protection affects the frequency of reportable misbehavior, which may make it harder for employees to signal trustworthiness.

3 Experimental Design

3.1 The Game

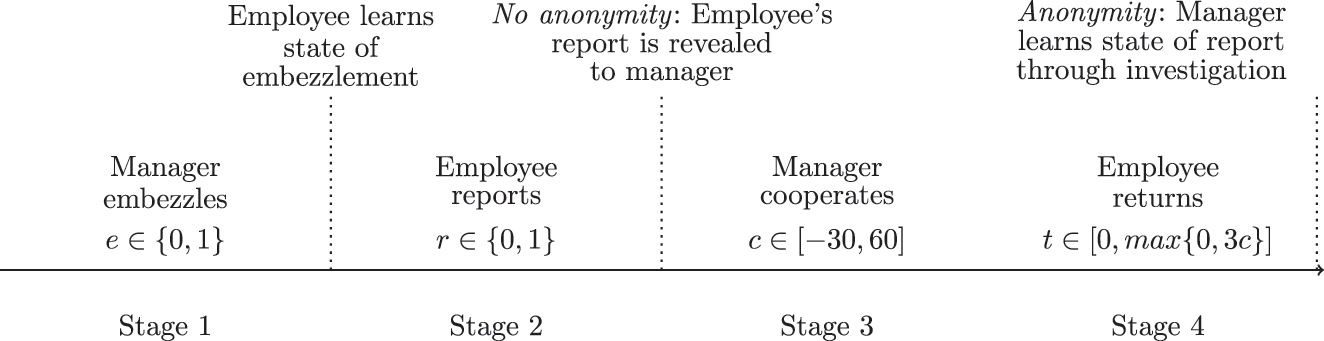

To investigate the influence of whistleblower protection on misbehavior, reporting behavior, and cooperative behavior, we combine a whistleblowing game with a modified trust game. The subjects take either the role of a manager, an employee, or a third party. While the third party is completely passive, both of the other roles have to make up to two decisions. In the whistleblowing game, the manager decides in the first stage whether to comply with the law (e = 0) or to embezzle money (e = 1), which generates revenue for her and a cost for the third party. In stage two, the employee decides whether to stay silent (r = 0) or to file a complaint (r = 1). He makes this decision conditional on the embezzlement decision of the manager. This means that the employee decides about reporting truthfully (r t ) in case the manager embezzles, and about reporting falsely (r f ) in case the manager complies.[5]

The trust game starts in stage three. The manager decides whether cooperation takes place by choosing the level c ∈ [−30, 60]. She can choose a negative amount, which means that she would take some of the employee’s endowment. If she trusts her employee (i.e., c is positive), this amount is multiplied by three and transferred to the employee. In stage four, the employee can return an amount t to his manager, if c was positive. If the employee has reported his manager in stage two, an investigation takes place at the end of a period, which is costly for the manager. If this investigation reveals embezzlement, the manager has to pay a fine. Moreover, the damage for the victim is partly recovered. The whole four stage process is repeated over several periods.

Cost and reward parameters There are four possible combinations of the decisions on embezzlement and reporting (e, r). These can be ranked in terms of social welfare π S (e, r) if three assumptions hold: (i) compliance is better than embezzlement, (ii) detected embezzlement is better than undetected embezzlement, and (iii) in case of compliance, the employee should not report. The order is given by

We chose the cost and reward parameters (in parentheses) such that these assumptions hold. The intuition is as follows: The most preferred outcome would be to have no embezzlement and no report (e = 0, r = 0). In this case, there is neither damage from embezzlement nor from an investigation, which leaves all players with just their endowment (Δπ S = 0). The least favorable outcome is undetected embezzlement (e = 1, r = 0). Here, the manager earns a benefit (50), which is outweighed by the cost for the third party (90). This would result in a social net loss (Δπ S = −40). A more preferable outcome would be detected embezzlement (e = 1, r = 1). The manager would have to pay a fine (60), which exceeds her benefit from embezzlement, and the costs of the investigation (10). On the other side, the third party partially recovers her loss R (80), such that social welfare loss is lower (Δπ S = −30). The fourth possibility is a false claim (e = 0, r = 1). This means that there is neither damage for the third party nor a benefit for the manager, but it creates an investigation cost (10) for the manager (Δπ S = −10).

For the trust game, we impose a range from −30 to 60 (with discrete steps of length ten) on c. A manager, who does not want to cooperate, because she does not expect this to be beneficial, could just choose c = 0. However, choosing a negative amount for c would indicate that the manager punishes an employee she does not trust. This decision could be interpreted as a reduction of bonus payments. Furthermore, the gradations of c give the manager the opportunity to differentiate whether she wants to recover the damage the employee caused–that is the loss from a false report (c = −10), or from a true report (c = −20)–or whether she wants to maximize her payoff (c = −30). These different values reflect that a manager could choose a very strict or a rather mild punishment in a real world setting, e.g., she could reduce potential bonus payments to her employee either mildly or strongly.[6] For positive values of c the upper bound is set to 60. This guarantees that the employee cannot punish the manager stronger by keeping the entire investment than by reporting. The endowment is set sufficiently high (100) such that neither party could make a loss nor is restricted in their choice set. Below, the payoffs for the three roles in one period, given the decisions of the subjects, are summarized.

3.2 Treatments

We vary the legal environment in the treatments in two dimensions: i) immunity, which means an insurance against a monetary loss and ii) anonymity, which means that the employee has not to reveal his reporting decision to the manager. This results in four treatments. These differ with respect to the choice set for the manager in the trust game conditional on the reporting decision of the employee (immunity) and the date when the manager is informed about the reporting decision (anonymity).

Baseline Treatment (B) In the baseline treatment, the manager knows about the employee’s reporting decision after stage two, i.e. before she chooses c. Further, she is free to choose a negative c independent of the reporting decision (compare to Figure 1).

Timing in a period with and without anonymity.

Immunity Treatment (I) In treatment I, in which only immunity is introduced, the manager knows the employee’s reporting decision after stage two as well. In this treatment, immunity is modeled such that, by filing a report, the employee can guarantee his status quo payoff. That means, if there has been a report, truthful or false, c has to be at least zero.

Anonymity Treatment (A) In treatment A, in which only anonymity is granted, the information about whistleblowing is disclosed only after stage four through the investigation, i.e. after the manager chose c. The choice of c is again unrestricted for any reporting decision. This change in the timing guarantees that the manager cannot condition cooperation on the actual reporting behavior of the employee.

Anonymity and Immunity Treatment (AI) In treatment AI, with both immunity and anonymity, the manager knows only after her choice of c whether the employee reported. In case the manager chose a negative c, it is set to zero ex-post.

3.3 Implementation

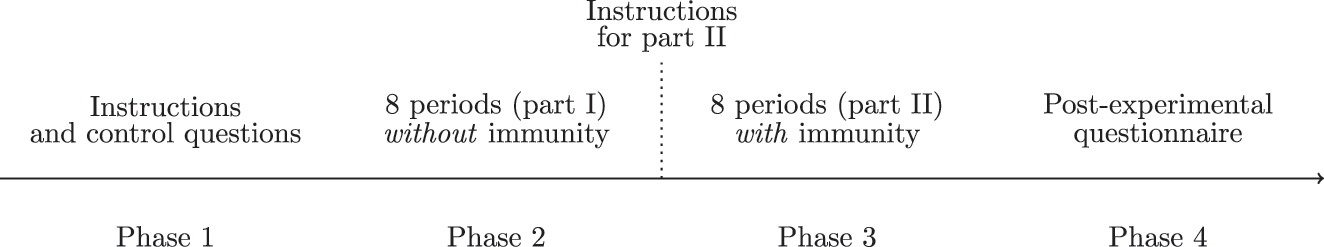

Session design The implementation of these treatments employs a between-as well as within-subject design. The introduction of anonymity comes with a larger variation between treatments as it changes the information structure within a period (see Figure 1). Therefore, anonymity is modeled as a between-subject design to prevent any overlapping effects between treatments. Introducing immunity only changes the choice set for the trust game. Hence, the intervention is not as severe and can be modeled as a within-subject design. Figure 2 displays how immunity is implemented. First, our subjects complete eight periods without immunity, followed by eight periods with immunity.

Timing in a session.

However, a within-subject design can trigger a “demand effect” which might lead to participants more or less consciously changing their behavior to satisfy the experimenter’s intentions (Charness, Gneezy, and Kuhn 2012). To counteract a potential demand effect, we employed several design choices: First, our participants had a short break after the first eight periods to achieve a natural separation between periods with and without immunity. In addition, we chose a relatively large number of periods per treatment such that a potential carryover effect can fade out and is less effective. To control for any remaining dependencies between consecutive periods, we use lagged variables and period fixed effects in the analysis.

Framing In experimental economics, there is a discussion on the conditions under which a neutral or a loaded framing is more appropriate.[7] In this regard, we chose a compromise similar to Mechtenberg, Muehlheusser, and Roider (2020). We framed the experiment in a workplace context and spoke of employers and employees to support the subjects in understanding the hierarchical relation between the players. Furthermore, we gave a reminder that the choice corresponding to embezzlement means a violation of the law. Thereby, we model an important feature of unethical decision-making in the real world, since wrongdoers are clearly aware that such decisions are illegal. The employee’s decision about a report was phrased as ’filing a complaint’ to make them aware of the social undesirability of embezzlement. Drawing attention to unethical behavior may influence the subjects’ decisions, which would be appropriate for this specific research question, though. Although a mixed framing may not do as well as a purely loaded framing in terms of clarifying the instructions, we phrased the choice about embezzlement in a neutral way (alternatives: CIRCLE or TRIANGLE). This was motivated by the possibility that subjects may bring in their individual perception of the severeness of a specific misbehavior. In this regard, embezzlement might be perceived as rather mild or rather serious misbehavior. Therefore, a neutral framing should prevent that the individual perception of embezzlement influences the behavior. Moreover, we used payoff tables (see Appendix B.1 in supplementary material) and control questions (see Appendix B.2 in supplementary material) to ensure that the precise consequences for all players are understood.

Procedural details At the beginning of the experiment, the subjects received instructions which explained the game described above. They were informed that this game will be played for eight periods before they receive instructions for the second part of the experiment.[8] Furthermore, they were told that managers keep their role throughout the experiment, while the other two roles are reshuffled after each period. The motivation for reshuffling the roles of the employee and the third party was twofold: First, it should make the harm of embezzlement more salient. Second, this procedure allows for a larger number of independent observations and reduces the likelihood that managers and employees face each other multiple times. Before a period started, groups of three were randomly formed with one subject of each role. The subjects face a stranger matching and cannot infer any information about their group members from previous periods.

While we asked the control questions at the start of a session, subjects completed a (non-incentivized) questionnaire in which we elicited socio-demographic information (e.g., age, gender, and field of study), risk preferences (via the “100,000 euro” question of Dohmen et al. 2011), and their attitudes towards revealing misbehavior (measured on a five-level Likert scale) at the end. With these questions, we wanted to elicit whether the attitudes differ between the subjects across the treatments, since this may influence the results. However, comparing subjects with different roles within a treatment, and subjects with the same role across treatments, we do not find statistically significant differences for the reported attitudes (see Table C.1 in supplementary material for the average characteristics).

The experiment was programmed with the software z-Tree (Fischbacher 2007). It was conducted in the laboratory of the University of Hamburg, June 2016, and we used hroot for recruitment (Bock, Baetge, and Nicklisch 2014). We ran five sessions with a total number of 147 student subjects (65 % female, average age: 25 years, the majority of the subjects were enrolled in economics or business programs). Four sessions had 30 participants (ten groups per period), one had 27 participants (nine groups per period). The number of subjects per role and treatment as well as the total number of observations is summarized in Table 1.

Observations per Decision.

| Treatment | Managers | Employees | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Subjects | Decisions | Subjects | Decisions | |

| B: | 30 | 240 | 60 | 480 |

| I: | 240 | 480 | ||

| A: | 19 | 152 | 38 | 304 |

| AI: | 152 | 304 | ||

To keep the incentives identical for every period over the entire experiment, one period was randomly drawn for payout after the questionnaire had been completed. The subjects received payments between 5.50 and 18.50 euro (including a show-up fee of 5 euro) with an average of 10.07 euro.

4 Behavioral Predictions

In this section, we establish the behavioral predictions on the employees’ willingness to report–truthfully and falsely–and their return behavior as well as on the decision of the managers to embezzle and to cooperate for the different treatments. We derive the behavioral predictions from the equilibrium analysis of a simplified version of the game described in Section 3, which is formally spelled out in Appendix A supplementary material (see Propositions 1 – 4).

Summary of the theoretical model In contrast to the game played in the experiment, we assume that the trust game, played in stages three and four, consists of two binary decisions: The manager decides to cooperate or not, and the employee returns either a high amount or a low amount. The high amount results in a net profit for the manager, while the low amount results in a net loss. Further, we assume that there are two types of employees: the “loyal” type has relatively high moral costs from being disloyal to the manager–that is, to return less than the manager invested in the trust game, or to report falsely–and relatively low moral costs from undetected embezzlement. For the “disloyal” type, it is the other way around. The manager does not know which type she is facing. She would like to cooperate if she faces a loyal employee since she could expect that cooperation would be profitable. Analogously, she would refrain from cooperation if she faces a disloyal type. If the manager does not embezzle, she is not able to screen the employees. In this case, her decision to cooperate depends on the expected share of loyal employees. Therefore, the crucial scenario is when the manager embezzles. Assume that the reporting decision would perfectly reveal the type of the employee. In this case, the manager would not cooperate if the employee reports. In case of a report, she knows that she is facing a disloyal employee, for whom the moral costs from undetected embezzlement are higher than the profit he would face from cooperation. Accordingly, the manager would cooperate if the employee does not report.

Predictions on truthful whistleblowing ( r t ) From the equilibrium described above, it follows that disloyal (loyal) employees will (not) truthfully report in treatment B. This equilibrium also holds in treatment I. However, it becomes more difficult to sustain in treatment I, as there is a reward for reporting, given the manager does not cooperate, and therefore the opportunity costs from not reporting for a loyal employee become larger. Consequently, we expect the empirical willingness to report to be at least as high in treatment I as in treatment B. In the treatments A and AI, reporting does not convey information about the type of the employee. Therefore, the reporting decision does not influence the manager’s cooperation decision and both types report embezzlement (see Prediction r t ).

Prediction (

r

t

).

Predictions on false whistleblowing ( r f ) The model considers the case where the reward for reporting does not outweigh the moral costs from false reporting. Consequently, both types would not report falsely in any treatment. This assumption does not necessarily hold in reality. Therefore, it is worthwhile to discuss possible deviations. If this assumption is relaxed and, for example, the moral costs are smaller than the reward for both types, there would still be no false reports in the treatments B and A, as there is no reward for reporting, and both types would still be better off by avoiding the moral cost from a false report. However, in the treatments where the manager has to compensate whistleblowers, I and AI, the scenario would be different. Both types would have an incentive to report falsely if they expect the manager not to cooperate. While in treatment I a report would make cooperation to happen less likely, in treatment AI it cannot affect the cooperation decision of the manager. Therefore, false reports should occur more frequently in treatment AI (see Prediction r f ).

Prediction (

r

f

).

Predictions on embezzlement (e) The decision to embezzle in treatment B depends on the manager’s belief about the share of loyal employees. It must hold that separating the types by embezzlement is more profitable than basing the cooperation decision on the belief about the share of loyal employees. The higher the share of loyal employees the more profitable becomes embezzlement: the probability to earn a profit from both cooperation and embezzlement increases, while the probability to be fined for embezzlement decreases. In treatment I, the threshold for embezzlement to be profitable is higher since the manager has to compensate the “disloyal” type. Therefore, screening becomes more expensive and the frequency of embezzlement should be lower. In treatments A and AI, any employee will report embezzlement, but the manager cannot learn about the type. Therefore, embezzlement should not occur (see Prediction e).

Prediction (e). e B > e I , e B > e A , e I > e AI , e A = e AI .

Predictions on the frequency of cooperation (c) Concerning the willingness to cooperate, the behavioral predictions are ambiguous. First, the comparison between treatments with and without anonymity depends on the share of loyal employees. As the manager cannot screen the employees in the treatments with anonymity, she would always cooperate if she expects the share to be high enough to make a profit. Vice versa, she would not cooperate in the treatments A and AI, if she expects that the share is too low. In the treatments without anonymity, the manager can identify the type of employee and would not cooperate with disloyal employees. Therefore, holding the expected share of loyal employees constant, the frequency of cooperation would be lower in the non-anonymous treatments. In contrast, if a manager believes the share of loyal employees is sufficiently low (i.e. she would not cooperate under anonymity), the frequency of cooperation would increase in treatments without anonymity, as she could identify employees she wants to cooperate with. Between the anonymity treatments A and AI, the model predicts no difference in the willingness to cooperate. For the comparison between the treatments B and I, it is relevant that there is less embezzlement in treatment I. Hence, there are less cases where the manager can identify the type of her employee in treatment I. That means, cooperation would be more frequent in treatment I if the manager expects a sufficiently large share of loyal employees. Vice versa, cooperation would be less frequent in treatment I if the expected share of loyal employees is not sufficiently large. In addition, there are two other effects in treatment I that work in opposite directions. On the one hand, it is more difficult for the loyal type to remain silent (compare to the prediction on truthful reporting). On the other hand, it is more expensive for the manager not to cooperate with employees who reported since she would have to compensate them. The model does not allow making a claim which effect might outweigh the other. Taken together, it is a priori difficult to compare the frequency of cooperation across treatments since it largely depends on the belief of the manager about the share of loyal employees (see Prediction c). While this belief is unknown to the experimenter, it is likely shaped by the experience from previous periods, which has to be considered in the analysis.

Prediction (c). c B ≶ c I , c B ≶ c A , c I ≶ c AI , c A = c AI .

Predictions on the frequency of high returns (h) The model allows making predictions about the frequency of employees returning an amount larger than the investment. These predictions presuppose that the manager cooperates. Recall that only the loyalty type of the employee influences his return decision once the manager decided to cooperate. As the manager cannot differentiate between the employee types in the treatments with anonymity, the model predicts no difference between the treatments A and AI. In the treatments without anonymity, the manager can identify the types in case she embezzles such that she does not cooperate with a disloyal type. The frequency of high returns should therefore be higher in the treatments without anonymity. As there is more embezzlement in treatment B, and therefore a higher degree of separation of the types, the frequency of high returns should be higher than in treatment I (see Prediction h).

Prediction (h). h B > h I , h B > h A , h I > h AI , h A = h AI .

5 Results

In this section, we analyze the treatment differences to identify the effects of whistleblower protection on reporting, embezzlement, as well as on the sending and the return behavior in the trust game. In a first step, we present the subjects’ average decision across the four treatments.

To test for statistical significance, we follow Moffatt (2015) and use non-parametric tests with subject-role-level averages as observational units. For between-subject differences, we apply a Mann-Whitney U test (B vs. A, I vs. AI), while we account for within-subject differences with a Wilcoxon signed-rank test (B vs. I, A vs. AI). To include the influence of past decisions, we additionally use panel regressions, which account for the number of independent observations and allow to control for period fixed effects. Individual-specific effects are assumed to be random, as they might vary conditional on the experience. As for the behavioral predictions, we will first consider the reporting behavior of the employees.

Truthful whistleblowing ( r t ) Since we use the strategy method for the employee’s decision to report, we track separately how the willingness to truthfully and falsely report differs across the treatments. Table 2a displays the fractions of employees that choose to truthfully report for each treatment. To evaluate the effect of the instruments immunity and anonymity on the willingness to report, we compare the outcome of the treatments I and A to treatment B. For treatment I, we find a significant increase from 72 % to 87 % (p < 0.01). In treatment A, the fraction rises to 84 %, however, this increase is not statistically significant (p < 0.20). We find the highest fraction of truthful reports in treatment AI with 89 %. This is a significant increase compared to treatment A (p < 0.01, only two out of 38 subjects decrease the reporting frequency), but not compared to treatment I (p < 0.49). These results provide evidence that both instruments, but especially immunity, affect the employee’s willingness to truthfully report and therefore support the prediction r t .

Reporting and embezzlement across treatments.

|

(a) Truthful reporting |

(b) False reporting |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Prediction: | Results: | Prediction: | Results: | ||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| ∧ ∧ | ∧ | ∧ | ‖ ∧| | ∧ | ∧*** | ||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| (c) Embezzlement | (d) Total reports | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Prediction: | Results: | |||||

| e B > e I | e B : 0.41 |

|

e I : 0.24 | r B : 0.40 |

|

r I : 0.46 |

| ∨ ∨ | ∨ | ∨** | ∨ | ∧** | ||

| e A = e AI | e A : 0.32 |

|

e AI : 0.08 | r A : 0.39 |

|

r AI : 0.58 |

-

The left side of tables (a)–(c) displays the predictions made in the previous section. The values on the right side of tables (a)–(c) report the average decisions of the subjects across the treatments. Table (d) reports the frequency of reports, i.e. the combination of embezzlement and true reporting, and no embezzlement and false reporting. For between-subject differences, we apply a Mann-Whitney U test (B vs. A, I vs. AI), while we account for within-subject differences with a Wilcoxon signed-rank test (B vs. I, A vs. AI). Significance levels: *p < 0.1; **p < 0.05; ***p < 0.01.

False whistleblowing (r f ) Analogously, Table 2b displays the willingness to conduct a false report. Surprisingly, we find 13 % of the employees would blow the whistle although there was no misbehavior in treatment B.[9] In line with prediction r f , we find that the share of false reporting does not increase significantly in treatment A (22 %, p < 0.54). However, introducing immunity in treatment I leads to a significant jump in false reports to 31 % (p < 0.01). These results indicate that a significant share of subjects expects the manager to take from their endowment instead of cooperating, and that the expected loss outweighs the moral cost from false reporting–other than assumed in the model. In line with this, the share of employees willing to file a false claim peaks in treatment AI with 54 % (p < 0.01 compared to A and to I). These findings support the prediction r f and suggest that subjects also react to the adverse incentives of whistleblower protection.

The results for truthful and false whistleblowing already provide evidence for costs as well as for benefits of whistleblower laws. Protection increases truthful reports, but provokes adverse effects in the form of false reports at the same time.

Embezzlement ( e ) The previous results indicate that, under whistleblower protection, embezzlement would be reported more often. Further, it is of interest whether managers anticipate these changes in reporting such that embezzlement is deterred (see Table 2c). Compared to treatment B (41 %), we find a significant drop in embezzlement when reporting is incentivized in treatment I to 24 % (p < 0.01). In treatment A, where the employee can report anonymously, also a lower share of 32 % decides to embezzle money. However, this decline is not statistically significant (p < 0.58). In treatment AI, only 8 % of the managers choose to embezzle money. This is a significant decline both from treatment A (p < 0.01) and from treatment I (p < 0.03). These results support prediction e. Regression results indicate that the subjects anticipate the reporting behavior based on their experiences. The dummy for reported embezzlement in the previous period is negative and highly significant, while the controls for the treatments do not explain the embezzlement frequency (see Table D.2 in supplementary material).

Interestingly, the number of overall reports is the highest in treatment AI (58 %), i.e. when the frequency of embezzlement is the lowest (see Figure 2d). While the number of reports is very similar in the treatments B, A, and I (B vs. I: p < 0.46, B vs. A: p < 0.80), in treatment AI, it increases significantly compared to both treatments A (39 %, p < 0.01) and I (46 %, p < 0.03). While the managers anticipate the high tendency to report, and therefore embezzlement is mostly deterred, the remaining cases (8 %) are entirely reported in treatment AI. That means there are no unreported cases of embezzlement and there is the highest frequency of false reports.

Cooperation ( c ) Having analyzed the reporting and the embezzlement behavior, we will evaluate the willingness to cooperate and the level of cooperation over the different treatments. The prediction c pointed out that treatment differences are difficult to anticipate, since the cooperation decision depends on the expectation of the manager with respect to the “loyalty type” she is facing. This expectation should be influenced by her latest experience with respect to the employees’ reporting and return behavior. Therefore, it will be crucial to use regression analysis to investigate the mechanisms between reporting and cooperative behavior. First, we analyze the cooperative behavior on the aggregated level. Table 3a shows the share of managers who chose a positive c across the treatments.

Frequency and level of cooperation across treatments.

| (a) Cooperation frequency | (b) Cooperation level | |

|---|---|---|

| Prediction: | Results: | |

| c B ≶ c I |

c

B

: 0.30

|

|

| ∨∧ ∨∧ | ∧∨ | ∨‖ |

| c A = c AI |

c

A

: 0.34

|

|

-

The left side of table (a) displays the predictions made in the previous section. The values on the right side of table (a) report the average cooperation frequency. Table (b) reports the average level of cooperation across the treatments, conditional on c being positive. Observations of cooperation level: B: 73, I: 62, A: 51, AI: 26. For between-subject differences, we apply a Mann-Whitney U test (B vs. A, I vs. AI), while we account for within-subject differences with a Wilcoxon signed-rank test (B vs. I, A vs. AI). Significance levels: *p < 0.1; **p < 0.05; ***p < 0.01.

Considering treatment B, we find a fraction of 30 % of the managers choosing to cooperate. Both in treatment A (34 %, p < 0.86), and in treatment I (26 %, p < 0.26), the willingness to cooperate is not significantly different. However, in treatment AI, only 17 % of the managers decide to cooperate. While this is not significantly different from treatment I (p < 0.35), it is a significant drop compared to treatment A (p < 0.02). The comparison of the average cooperation over the treatments does not support the prediction e as the model does not predict differences between the anonymity treatments.

To investigate in detail what could explain the treatment differences, it is important to recall what could drive the cooperation decision of a manager. In treatments without anonymity, the manager may receive a direct signal from the employee on his trustworthiness through the reporting decision. Precisely, if a manager embezzles and the employee does not report, it may lead the manager to cooperate more likely. In treatments with anonymity, the manager cannot infer any information about the trustworthiness from the reporting decision of the employee as it is not observed. However, since the decisions are made repeatedly, a manager may infer from reporting decisions from previous periods how likely it is to face a trustworthy employee. Moreover, in all treatments, the experience with respect to the return behavior of the employees may shape the expectation about the average trustworthiness.

To analyze the influence of the managers’ experience, we use regressions that control for the embezzlement decision in the respective period, the most recent reporting decision and whether there was profitable cooperation in the last period. As the most recent reporting decision is different for subjects in the anonymous and in the non-anonymous treatments, we split the sample and conduct the regressions separately.

The regression results for the frequency of cooperation in non-anonymous treatments are reported in Table 4 (columns 1–3). First, we turn the attention to the experienced return behavior (column 2). The coefficient for a loss from cooperation in the previous period–that is, the employee returned less than the manager sent–is negative and highly significant. Moreover, the results indicate that also the reporting behavior plays an important role. The coefficient for having experienced unreported embezzlement is positive and significant, though only weakly. This suggests that the subjects adjust their expectations about the profitability of cooperation based on their cooperation experience and on whether embezzlement was reported. Controlling for period fixed effects, the coefficients in Table 4, column (3) suggest that the results do not change qualitatively.

Regression analysis: Cooperation without anonymity.

| Cooperation Frequency | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | (3) | |

| Treatment I | −0.0458 | 0.104 | 0.145 |

| (0.0538) | (0.0872) | (0.0902) | |

| LowReturn(lag) | −0.245*** | −0.251*** | |

| (0.0797) | (0.0901) | ||

| Embezzlement | −0.228** | −0.238* | |

| (0.112) | (0.125) | ||

| FalseReport | 0.102 | 0.0377 | |

| (0.156) | (0.168) | ||

| UnreportedEmbezzlement | 0.356* | 0.348* | |

| (0.212) | (0.201) | ||

| Constant | 0.304*** | 0.572*** | 0.366 |

| (0.0452) | (0.112) | (0.233) | |

| Period FE | No | No | Yes |

| N | 480 | 131 | 131 |

| N groups | 30 | 28 | 28 |

| R 2 | 0.00260 | 0.128 | 0.156 |

-

The table reports results from a random-effects GLS regression where N groups is the number of individuals. Dependent variable: (1)–(3): cooperation decision of managers (0 or 1). LowReturn, Embezzlement, FalseReport, UnreportedEmbezzlement are all binary variables. (lag) indicates a lagged variable. ReportedEmbezzlement is omitted because of collinearity. Standard errors in parentheses are clustered on the individual level. Significance levels: *p < 0.1; **p < 0.05; ***p < 0.01.

Analogously, the regression results for the frequency of cooperation in the anonymous treatments are reported in Table 5. It is controlled for the same variables as before, with the exception that the most recent observed reporting is from the previous period. Therefore, the variables on reporting are lagged by one period. The results for the anonymous treatments provide a similar picture as before (see Table 5, column 2). The coefficient for having experienced a loss from cooperation in the previous period is negative and highly significant as well. Further, the results for anonymous reporting indicate that the most recent reporting behavior plays a role, even if it cannot be linked to the present employee. The coefficient for having experienced unreported embezzlement is positive and highly significant. If we include the period fixed effect, the coefficient remains significant, but only weakly.

Regression analysis: Cooperation with anonymity.

| Cooperation Frequency | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | (3) | |

| Treatment AI | −0.164*** | −0.113 | −0.0540 |

| (0.0575) | (0.103) | (0.129) | |

| LowReturn(lag) | −0.538*** | −0.506*** | |

| (0.126) | (0.171) | ||

| Embezzlement | −0.311*** | −0.339*** | |

| (0.115) | (0.0926) | ||

| FalseReport(lag) | 0.158 | 0.154 | |

| (0.140) | (0.145) | ||

| UnreportedEmbezzlement(lag) | 0.344*** | 0.351* | |

| (0.128) | (0.180) | ||

| ReportedEmbezzlement(lag) | −0.0521 | −0.102 | |

| (0.106) | (0.149) | ||

| Constant | 0.336*** | 0.810*** | 0.980*** |

| (0.0671) | (0.0968) | (0.194) | |

| Period FE | No | No | Yes |

| N | 304 | 75 | 75 |

| N groups | 19 | 16 | 16 |

| R 2 | 0.0358 | 0.355 | 0.379 |

-

The table reports results from a random-effects GLS regression where N groups is the number of individuals. Dependent variable: (1)–(3): cooperation decision of managers (0 or 1). LowReturn, Embezzlement, FalseReport, UnreportedEmbezzlement, ReportedEmbezzlement are all binary variables. (lag) indicates a lagged variable. Standard errors in parentheses are clustered on the individual level. Significance levels: *p < 0.1; **p < 0.05; ***p < 0.01.

The regression results indicate that the decision to cooperate depends on the most recent experience with respect to the returning and the reporting behavior of the employees. This may explain the differences in cooperation between the anonymous treatments on the aggregate level. Note that in treatment AI, embezzlement is completely deterred. Therefore, cases, where an employee could refrain from a truthful report to signal trustworthiness, do not occur. While the theory predicts no difference for the frequency of embezzlement between the anonymous treatments, embezzlement is more prevalent in treatment A nevertheless (see Figure 2c). Moreover, in 19 % of the cases, the employee does not report the embezzlement. That means, in treatment A the managers experience unreported embezzlement, which they may perceive as a signal of trustworthiness, but not in treatment AI. In consequence, the drop in cooperation between the anonymous treatments may result from the different levels of deterrence.

In addition to the treatment differences, it is interesting whether the cooperative behavior of managers can be distinguished based on their prior behavior. Before the cooperation decision takes place, each manager already made a decision whether to embezzle. The results from Tables 4 and 5 show that managers, who chose to embezzle, cooperate less often. Moreover, false reports seem not to affect the cooperation decision. This suggests that mainly managers, who chose to embezzle, drive the lower cooperation rates.

Apart from the general decision to cooperate or not, the level of cooperation is of interest. Since the design allows to vary the level of trust, managers may rather adjust the amount that is trusted to the employee instead of refraining from cooperation in general. To account for this, we consider only those managers who chose to cooperate and present the trusted share of their endowment (Table 3b). The results suggest that there are no treatment differences for the size of cooperation. Independent of the protection scheme, the trusted share lies within a range of 40–44 % of the endowment, which roughly corresponds to the average investment level across experimental studies (see e.g., Fehr and Schmidt 2006).

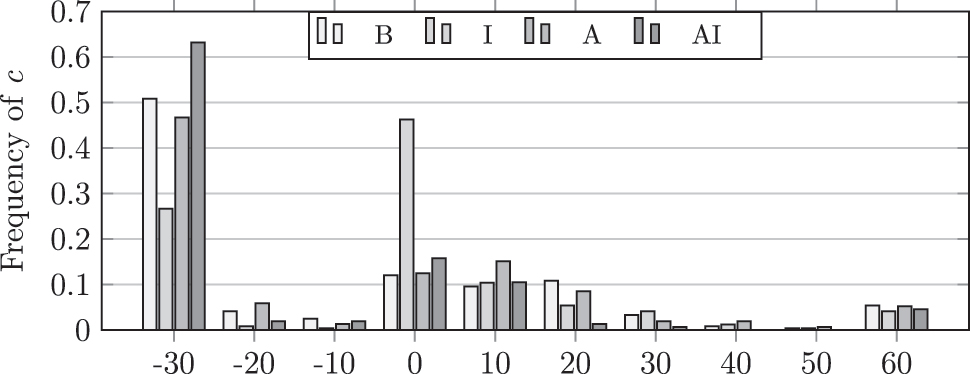

To obtain a more detailed picture of the cooperation level, Figure 3 illustrates the distribution of the realizations of c across the treatments. Given the decision to send a positive or negative c, the results suggest that the choice of the level of c is very similar across the treatments. Those managers, who cooperate, send predominantly a small c (10, or 20) and sometimes the highest possible amount (60). Those managers, who do not cooperate, just send nothing in one out of six cases, while in almost all of the remaining cases, they choose the lowest possible c (−30). However, there is a striking difference for the treatment I. As there is immunity if the employee reports, the manager cannot choose c = −30 as the minimum in this case, but only zero. Correspondingly, a notably higher rate (roughly two thirds) of those managers, who do not cooperate, (has to) choose zero. As the managers choose a negative c when they do not expect the employee to be trustworthy, and false reports seem not to decrease the cooperation likelihood, immunity increases the earnings for employees.

Distribution of amounts taken/sent.

Return behavior To conclude, we will turn the focus to the return behavior of the employees. In a similar vein as for the cooperation decision, we consider a binary decision–whether to return more or less than the manager sent–and the level of the amount the employees return. Table 6a shows the share of employees, who returned more than the manager sent (high return), conditional on the manager having chosen a positive c.

Return behavior.

| (a) High return | (b) Level of return | |

|---|---|---|

| Prediction: | Results: | |

| h B > h I |

h

B

: 0.49

|

|

| ∨ ∨ | ∧ ∨ | ∨ ∨ |

| h A = h AI |

h

A

: 0.51

|

|

-

The left side of table (a) displays the predictions made in the previous section. The values on the right side of table (a) report the average rate of employees returning more than what was sent. Table (b) reports the average level of return across the treatments. Observations of return decisions: B: 73, I: 62, A: 51, AI: 26. For between-subject differences, we apply a Mann-Whitney U test (B vs. A, I vs. AI), while we account for within-subject differences with a Wilcoxon signed-rank test (B vs. I, A vs. AI). Significance levels: *p < 0.1; **p < 0.05; ***p < 0.01.

There should be no differences in the frequency of high returns between treatments A and AI, since, due to the employee’s anonymous reporting, the managers will cooperate equally frequent with loyal and disloyal employees in these two treatments. In the non-anonymous treatments, the managers will primarily cooperate with employees who signal loyalty by not reporting. These employees are expected to send a high return more frequently than less loyal employees. Hence, the non-anonymous treatments should have a higher share of employees who send a high return. In addition, the share should be higher for treatment B than for treatment I (compare to prediction h). The comparison of the treatments B and I supports this prediction as the decrease from 49 % to 44 % is statistically significant (p < 0.01, just one of 32 subjects increased the frequency of returning more than what was sent). However, the results cannot support a higher frequency of high returns in the non-anonymous treatments (B vs. A: p < 0.69, I vs. AI: p < 0.33). Comparing the two anonymous treatments, the frequency appears to be higher in treatment A (51 %) than in treatment AI (38 %), but we cannot provide statistical significance for this difference as it results from a low number of subjects (N = 13).

Furthermore, controlling for past behavior allows to identify whether the reporting decision of an employee corresponds to a certain return behavior. The results from a regression analysis illustrate that employees, who made a false claim, are less likely to return more than what the manager sent (see Table D.3 in supplementary material). As false reports do not lower the frequency of cooperation, managers seem not to anticipate this return behavior. Moreover, unreported embezzlement is not associated with a higher frequency of high returns, although managers reward it more often with cooperation. Interestingly, these results suggest that managers may not react optimally to the observed reporting behavior.

Similarly to the cooperation decision of the managers, the employees may rather adjust the level of the amount they return. Table 6b shows that the employees return, on average, between 57 and 76 % of what was sent to them. The tests do not report any significant difference between the treatments.

6 Discussion

With this paper, we shed light on the potential hidden costs of whistleblower protection. In a workplace setup, a manager has the option to embezzle money at the expense of a third party, while her employee observes this and has the option to report his manager before they play a trust game. We varied the framework in two dimensions to capture two prominent features of whistleblower protection laws: First, not revealing the reporting decision to the manager before the trust game allows the employee to report anonymously. Second, prohibiting the manager to take money from the employee in the trust game conditional on a report, enables the employee to insure himself against retaliation from the manager after blowing the whistle.

In line with the literature (see, e.g. Bartuli, Mir Djawadi, and Fahr 2016; Butler, Serra, and Spagnolo 2020; Schmolke and Utikal 2025), our results confirm that both instruments, anonymity and immunity, have the intended effects: we observe an increased willingness to truthfully report a manager’s embezzlement by the employees. The managers anticipate this behavior and reduce their embezzlement. This suggests that whistleblower laws offer a rich potential for fighting the damage of corporate fraud through both increased deterrence and detection. On the other hand, the findings demonstrate that whistleblower protection also provokes adverse effects. Since the reporting incentive is not conditioned on a successful investigation, this does not only increase truthful reporting, but also does trigger false whistleblowing by the employees.

A novel finding of this paper relates to the costs associated with the deterrence of misbehavior. Beyond the negative direct impact from reports–costlyinvestigations for authorities or the organization–we emphasize the negative effects of whistleblowing for the cooperative climate in an organization. Increasing the willingness to report leads to a high level of deterrence, but also decreases trust between manager and employee. A high level of distrust can have detrimental effects on productive cooperation. In consequence, social welfare could be negatively affected by whistleblower protection although it deters misbehavior.

We chose a simple design for the whistleblowing game, where the employee has precise knowledge about the state of illegal behavior of his superior. Further, the employee does not face the risk of leaks under anonymity. In addition, an investigation and immunity are guaranteed consequences of a report. This captures the intended increase in being certain about their legal protection for the whistleblower. In reality, when not all of these assumptions are met, uncertainty may also influence the employee’s behavior under the different protection regimes and cause a lower responsiveness (see e.g., Chassang and Miquel 2019; Mechtenberg, Muehlheusser, and Roider 2020). Therefore, our results may serve as a benchmark for future studies that relax these assumptions. As our theoretical model does not cover all behavioral types of employees, future research may be able to fill this gap and provide additional insights on predicted behavior.

Funding source: Fritz Thyssen Stiftung

Award Identifier / Grant number: 10.13.2.097

References

Abbink, K., and H. Hennig-Schmidt. 2006. “Neutral versus Loaded Instructions in a Bribery Experiment.” Experimental Economics 9 (2): 103–21. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10683-006-5385-z.Search in Google Scholar

Abbink, K., B. Irlenbusch, and E. Renner. 2000. “The Moonlighting Game: An Experimental Study on Reciprocity and Retribution.” Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization 42 (2): 265–77. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0167-2681(00)00089-5.Search in Google Scholar

Abeler, J., D. Nosenzo, and C. Raymond. 2019. “Preferences for Truth-Telling.” Econometrica 87 (4): 1115–53. https://doi.org/10.3982/ecta14673.Search in Google Scholar

Ajzenman, N. 2021. “The Power of Example: Corruption Spurs Corruption.” American Economic Journal: Applied Economics 13 (2): 230–57. https://doi.org/10.1257/app.20180612.Search in Google Scholar

Alekseev, A., G. Charness, and U. Gneezy. 2017. “Experimental Methods: When and Why Contextual Instructions Are Important.” Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization 134: 48–59. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jebo.2016.12.005.Search in Google Scholar

Alford, C. 2001. Whistleblowers: Broken Lives and Organizational Power. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.Search in Google Scholar

Barr, A., and D. Serra. 2009. “The Effects of Externalities and Framing on Bribery in a Petty Corruption Experiment.” Experimental Economics 12 (4): 488–503. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10683-009-9225-9.Search in Google Scholar

Bartuli, J., B. Mir Djawadi, and R. Fahr. 2016. “Business Ethics in Organizations: An Experimental Examination of Whistleblowing and Personality.” IZA Discussion Paper 10190.10.2139/ssrn.2840134Search in Google Scholar

Berg, J., J. Dickhaut, and K. McCabe. 1995. “Trust, Reciprocity, and Social History.” Games and Economic Behavior 10 (1): 122–42. https://doi.org/10.1006/game.1995.1027.Search in Google Scholar

Bloom, N., R. Sadun, and J. Van Reenen. 2012. “The Organization of Firms across Countries.” The Quarterly Journal of Economics 127 (4): 1663–705. https://doi.org/10.1093/qje/qje029.Search in Google Scholar

Bock, O., I. Baetge, and A. Nicklisch. 2014. “Hroot: Hamburg Registration and Organization Online Tool.” European Economic Review 71: 117–20. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.euroecorev.2014.07.003.Search in Google Scholar

Bracht, J., and N. Feltovich. 2009. “Whatever You Say, Your Reputation Precedes You: Observation and Cheap Talk in the Trust Game.” Journal of Public Economics 93 (9-10): 1036–44. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpubeco.2009.06.004.Search in Google Scholar

Brandts, J., and G. Charness. 2011. “The Strategy versus the Direct-Response Method: A First Survey of Experimental Comparisons.” Experimental Economics 14 (3): 375–98. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10683-011-9272-x.Search in Google Scholar

Buccirossi, P., G. Immordino, and G. Spagnolo. 2021. “Whistleblower Rewards, False Reports, and Corporate Fraud.” European Journal of Law and Economics 51 (3): 411–31. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10657-021-09699-1.Search in Google Scholar

Butler, J. V., D. Serra, and G. Spagnolo. 2020. “Motivating Whistleblowers.” Management Science 66 (2): 605–21. https://doi.org/10.1287/mnsc.2018.3240.Search in Google Scholar

Callahan, E. S., and T. M. Dworkin. 1992. “Do Good and Get Rich: Financial Incentives for Whistleblowing and the False Claims Act.” Villanova Law Review 37: 273.Search in Google Scholar

Cassematis, P. G., and R. Wortley. 2013. “Prediction of Whistleblowing or Non-reporting Observation: The Role of Personal and Situational Factors.” Journal of Business Ethics 117 (3): 615–34. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-012-1548-3.Search in Google Scholar

Charness, G., U. Gneezy, and M. A. Kuhn. 2012. “Experimental Methods: Between-Subject and Within-Subject Design.” Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization 81 (1): 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jebo.2011.08.009.Search in Google Scholar

Chassang, S., and G. P. I. Miquel. 2019. “Crime, Intimidation, and Whistleblowing: A Theory of Inference from Unverifiable Reports.” The Review of Economic Studies 86 (6): 2530–53. https://doi.org/10.1093/restud/rdy075.Search in Google Scholar

Dohmen, T., A. Falk, D. Huffman, U. Sunde, J. Schupp, and G. G. Wagner. 2011. “Individual Risk Attitudes: Measurement, Determinants, and Behavioral Consequences.” Journal of the European Economic Association 9 (3): 522–50. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1542-4774.2011.01015.x.Search in Google Scholar

Dworkin, T., and J. Near. 1997. “A Better Statutory Approach to Whistle-Blowing.” Business Ethics Quarterly 7 (1): 1–16. https://doi.org/10.2307/3857229.Search in Google Scholar

Dyck, A., A. Morse, and L. Zingales. 2010. “Who Blows the Whistle on Corporate Fraud?” The Journal of Finance 65 (6): 2213–53. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6261.2010.01614.x.Search in Google Scholar

Dyck, A., A. Morse, and L. Zingales. 2024. “How Pervasive Is Corporate Fraud?” Review of Accounting Studies 29 (1): 736–69. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11142-022-09738-5.Search in Google Scholar

Fehr, E., and K. M. Schmidt. 2006. “The Economics of Fairness, Reciprocity and Altruism–Experimental Evidence and New Theories.” Handbook of the Economics of Giving, Altruism and Reciprocity 1: 615–91.10.1016/S1574-0714(06)01008-6Search in Google Scholar

Fehrler, S., and W. Przepiorka. 2016. “Choosing a Partner for Social Exchange: Charitable Giving as a Signal of Trustworthiness.” Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization 129: 157–71. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jebo.2016.06.006.Search in Google Scholar

Felli, L., and R. Hortala-Vallve. 2016. “Collusion, Blackmail and Whistle-Blowing.” Quarterly Journal of Political Science 11 (3): 279–312. https://doi.org/10.1561/100.00015060.Search in Google Scholar

Fiorin, S. 2023. “Reporting Peers’ Wrongdoing: Experimental Evidence on the Effect of Financial Incentives on Morally Controversial Behavior.” Journal of the European Economic Association. forthcoming. https://doi.org/10.1093/jeea/jvad002.Search in Google Scholar

Fischbacher, U. 2007. “z-tree: Zurich toolbox for Ready-Made Economic Experiments.” Experimental Economics 10 (2): 171–8. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10683-006-9159-4.Search in Google Scholar

Friebel, G., and S. Guriev. 2012. “Whistle-blowing and Incentives in Firms.” Journal of Economics and Management Strategy 21 (4): 1007–27. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1530-9134.2012.00354.x.Search in Google Scholar

Gambetta, D., and Á. Székely. 2014. “Signs and (Counter) Signals of Trustworthiness.” Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization 106: 281–97. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jebo.2014.07.009.Search in Google Scholar

Givati, Y. 2016. “A Theory of Whistleblower Rewards.” The Journal of Legal Studies 45 (1): 43–72. https://doi.org/10.1086/684617.Search in Google Scholar

Heyes, A., and S. Kapur. 2009. “An Economic Model of Whistle-Blower Policy.” Journal of Law, Economics, and Organization 25 (1): 157–82. https://doi.org/10.1093/jleo/ewm049.Search in Google Scholar

Heyes, A., and J. A. List. 2016. “Supply and Demand for Discrimination: Strategic Revelation of Own Characteristics in a Trust Game.” American Economic Review 106 (5): 319–23. https://doi.org/10.1257/aer.p20161011.Search in Google Scholar

Howse, R., and R. Daniels. 1995. “Rewarding Whistleblowers: The Costs and Benefits of an Incentive-Based Compliance Strategy.” In Corporate Decisionmaking in Canada, edited by R. Daniels, and R. Morck. Calgery: University of Calgary Press.Search in Google Scholar

Huber, C., C. Litsios, A. Nieper, and T. Promann. 2023. “On Social Norms and Observability in (Dis) Honest Behavior.” Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization 212: 1086–99. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jebo.2023.06.019.Search in Google Scholar

Kohn, S. M., M. D. Kohn, and D. K. Colapinto. 2004. Whistleblower law: A Guide to Legal Protections for Corporate Employees. Westport, CT: Greenwood Publishing Group.Search in Google Scholar

Mechtenberg, L., G. Muehlheusser, and A. Roider. 2020. “Whistleblower Protection: Theory and Experimental Evidence.” European Economic Review 126: 103447. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.euroecorev.2020.103447.Search in Google Scholar

Mir Djawadi, B. and P. Nieken. 2019. “Labor Market Chances of Whistleblowers-Potential Drivers of Discrimination.” Available at https://ssrn.com/abstract=3481126.10.2139/ssrn.3481126Search in Google Scholar

Moffatt, P. G. 2015. Experimetrics: Econometrics for Experimental Economics. London, UK: Macmillan International Higher Education.Search in Google Scholar

Near, J. P., and M. P. Miceli. 1986. “Retaliation against Whistle Blowers: Predictors and Effects.” Journal of Applied Psychology 71 (1): 137. https://doi.org/10.1037//0021-9010.71.1.137.Search in Google Scholar

Nyreröd, T., and G. Spagnolo. 2021. “Myths and Numbers on Whistleblower Rewards.” Regulation & Governance 15 (1): 82–97. https://doi.org/10.1111/rego.12267.Search in Google Scholar

OECD. 2016. Committing to Effective Whistleblower Protection. Paris: OECD Publishing.Search in Google Scholar

Reuben, E., and M. Stephenson. 2013. “Nobody Likes a Rat: On the Willingness to Report Lies and the Consequences Thereof.” Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization 93: 384–91. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jebo.2013.03.028.Search in Google Scholar

Schmolke, K. U., and V. Utikal. “Whistleblowing: Incentives and situational determinants.” Journal of Business Economics (2025): 1–24.10.1007/s11573-025-01223-0Search in Google Scholar

Selten, R. 1967. “Die Strategiemethode zur Erforschung des eingeschränkt rationalen Verhaltens im Rahmen eines Oligopolexperiments.” In Beiträge zur experimentellen Wirtschaftsforschung, 136–68. Tübingen: JCB Mohr (Paul Siebeck).Search in Google Scholar

Thüsing, G., and G. Forst. 2016. Whistleblowing–A Comparative Study, Volume 16. Cham, Switzerland: Springer.10.1007/978-3-319-25577-4Search in Google Scholar

Vinten, G. 1994. Whistleblowing-fact and Fiction. An Introductory Discussion, 1–20. Whistleblowing: Subversion or corporate citizenship.Search in Google Scholar

Walters, K. D. 1975. “Your Employees Right to Blow Whistle.” Harvard Business Review 53 (4): 26.Search in Google Scholar

Yu, X. 2013. “Securities Fraud and Corporate Finance: Recent Developments.” Managerial and Decision Economics 34 (7-8): 439–50. https://doi.org/10.1002/mde.2621.Search in Google Scholar

Supplementary Material

This article contains supplementary material (https://doi.org/10.1515/rle-2024-0075).

© 2025 the author(s), published by De Gruyter, Berlin/Boston

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Articles

- The Impact of Online Dispute Resolution on the Judicial Outcomes in India

- Legal Compliance and Detection Avoidance: Results on the Impact of Different Law-Enforcement Designs

- Women in Piracy. Experimental Perspectives on Copyright Infringement

- Is Investment in Prevention Correlated with Insurance Fraud? Theory and Experiment

- Bias, Trust, and Trustworthiness: An Experimental Study of Post Justice System Outcomes

- Do Sanctions or Moral Costs Prevent the Formation of Cartel Agreements?

- Efficiency and Distributional Fairness in a Bankruptcy Procedure: A Laboratory Experiment

- Soft Regulation for Financial Advisors

- Conciliation, Social Preferences, and Pre-Trial Settlement: A Laboratory Experiment

- The Impact of Tax Culture on Tax Rate Structure Preferences: Results from a Vignette Study with Migrants and Non-Migrants in Germany

- Perceptions of Justice: Assessing the Perceived Effectiveness of Punishments by Artificial Intelligence versus Human Judges

- Judged by Robots: Preferences and Perceived Fairness of Algorithmic versus Human Punishments

- The Hidden Costs of Whistleblower Protection

- The Missing Window of Opportunity and Quasi-Experimental Effects of Institutional Integration: Evidence from Ukraine

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Articles

- The Impact of Online Dispute Resolution on the Judicial Outcomes in India

- Legal Compliance and Detection Avoidance: Results on the Impact of Different Law-Enforcement Designs

- Women in Piracy. Experimental Perspectives on Copyright Infringement

- Is Investment in Prevention Correlated with Insurance Fraud? Theory and Experiment

- Bias, Trust, and Trustworthiness: An Experimental Study of Post Justice System Outcomes

- Do Sanctions or Moral Costs Prevent the Formation of Cartel Agreements?

- Efficiency and Distributional Fairness in a Bankruptcy Procedure: A Laboratory Experiment

- Soft Regulation for Financial Advisors

- Conciliation, Social Preferences, and Pre-Trial Settlement: A Laboratory Experiment

- The Impact of Tax Culture on Tax Rate Structure Preferences: Results from a Vignette Study with Migrants and Non-Migrants in Germany

- Perceptions of Justice: Assessing the Perceived Effectiveness of Punishments by Artificial Intelligence versus Human Judges

- Judged by Robots: Preferences and Perceived Fairness of Algorithmic versus Human Punishments

- The Hidden Costs of Whistleblower Protection

- The Missing Window of Opportunity and Quasi-Experimental Effects of Institutional Integration: Evidence from Ukraine