Abstract

Using vignettes that are based on seminal cases in law and economics, I find that judicial decisions across different areas of the common law are considered to be fairer when they follow prescriptions for efficiency based on law-and-economic reasoning. Vignettes describe legal disputes and require respondents to rate the fairness of a judge’s resolution. For each vignette, fairness ratings are compared across a version that follows a particular economic prescription and a version that does not, with differences across versions generated by subtle changes in context that are motivated by the economic logic that either was used in the relevant case’s actual judicial opinion or has been applied to the case by scholars of law and economics. The results suggest that the economic logic that underlies the Coase theorem, the Hand rule and the foreseeability doctrine, and generates prescriptions for efficient use of strict product liability and efficient breach of contract, aligns with lay intuitions of fairness. The results also identify two areas, fugitive property and punitive damages, where law-and-economic prescriptions do not align with perceptions of fairness.

1 Introduction

Scholars in law and economics draw a sharp contrast between the perspectives that lawyers and economists take toward common-law legal rules. Traditional legal theorists claim that legal rules primarily reflect (or should reflect) fairness or justice, while proponents of law and economics, instead, typically claim that common-law legal rules aim (or should aim) to further forward-looking, consequentialist ends. Economists, therefore, emphasize the ex ante consequences that laws will have on economic exchange and are likely to view economic efficiency as an important normative and/or positive goal when resolving novel disputes, which lack a clear precedent, in the common law.

Following from assumptions of rationality and utility maximization, scholars of law and economics have uncovered a set of model-driven prescriptions for how laws can facilitate economic exchange and promote economic efficiency. They have also catalogued an abundance of legal cases, with their attached judicial opinions, to document how legal rules across different areas of the common law meet the prescriptions developed through theoretical law and economics (Barnes and Stout, 1992). Combined, economic prescriptions for legal rules, as well as the set of cases that show these prescriptions being applied, fill law-and-economics textbooks (e. g. Cole and Grossman, 2011; Cooter and Ulen, 2012; Miceli, 2009; Posner, 1998) and shape the curricula in courses in law and economics.

Given that the law-and-economic perspective differs from the standard legal perspective, the issue of whether law and economics is moral has been frequently examined. An earlier academic debate between proponents (Cohen, 1987; Easterbrook, 1984; Hardin, 1992; Posner, 1983) and critics (Baker, 1980; Calabresi, 1980; Coleman, 1980, 1988; Dworkin, 1980a, 1980b; Kennedy and Michelman, 1980; Malloy, 1995; Samuels, 1990; Veljanovski, 1981) of law and economics has yielded to a broad consensus among scholars in the discipline, which is articulated in different ways within law-and-economics textbooks, that there is some overlap between morality and law-and-economics reasoning. Cooter and Ulen (2012) argue that the law embeds efficiency principles under different names and that efficient rules, since they make society on net better off in the long run, would reflect the choice of a fairness-motivated judge. Cole and Grossman (2011) state that, “… although efficiency and justice are not mutually exclusive, neither are they always hand-in-glove” (62). Mercuro and Medema (2006), further pointing to a limited degree of overlap, specifically warn about overreach in applying the efficiency criterion to areas where many believe it does not belong. Shavell (2004) makes the point that,

The picture appears to be one in which our theory of what is socially desirable, with respect to the fairly simple measures of social welfare that we considered, sometimes is consistent with our legal system and other times conflicts with it (670).

Yet, despite this consensus, the question of whether law-and-economic prescriptions are moral has received minimal empirical attention. It remains to be seen how extensive the intersection is, and what properties define the areas that do, and do not, intersect. Vignette-based studies, which uncover lay intuitions of fairness, and experiments using distribution games, which identify the social preferences that drive economic decisions, point to a widely held, but context-dependent, motive for efficiency (also referred to as welfare-maximizing preferences). But does the perceived fairness of efficiency extend to prescriptions for efficient common law legal rules and, if so, does it vary across particular doctrines and different areas of the common law?

Since responsiveness to, and acceptance of, the economic approach to studying the law may be affected by the degree to which moral intuitions align with the implications that the approach generates, the nature of this alignment may shed light on an important source of resistance or determine, in part, the optimal strategy for finding and developing supporters of the law-and-economic perspective. Empirical evidence of alignment between fairness and law-and-economic prescriptions would allow teachers and scholars to promote and foster the field’s inherent morality; empirical evidence of misalignment may suggest that moral contrarians will be more naturally drawn to the field, or that support for law and economics is more easily achieved if homegrown notions of morality give way to an opposing prioritization of efficiency.

In this paper, I use an experimentally-designed, vignette-based survey to examine the connection between fairness and law-and-economic prescriptions. The vignettes are modified versions of seminal, precedent-setting cases in the law-and-economics literature; each vignette describes a specific legal dispute and the court’s decision regarding how to resolve the dispute. Law-and-economic reasoning, from either the actual judicial opinion or from the work of scholars analyzing the case, is used to create two different versions of each vignette. One version follows the prescriptions from law and economic analysis, while the other does not – with differences generated by subtle changes in context that are inspired by the economic logic that either was used in the relevant case’s actual judicial opinion or has been applied to the case by scholars of law and economics. After seeing one of the two versions of a vignette, respondents are required to rate the fairness of the ruling on a six-point scale that ranges from completely unfair to completely fair. Because the two versions of each vignette possess the same core dispute and the same legal ruling, and are identical aside from the contextual features that cause only one of the two versions to more closely align with law-and-economic prescriptions, any difference in fairness ratings across the two versions must be attributed to the contextual difference.

To preview the results, I find evidence that, with respect to core concepts in law and economics – e. g. the Coase theorem, property disputes involving competing claims, the Hand rule, strict products liability, efficient breach of contract, and the foreseeability doctrine – legal rulings are considered to be fairer when they more closely align with the prescriptions that follow from law-and-economic reasoning. More specifically, across property law, contract law and tort law, the following results speak to a connection between law-and-economic reasoning and moral intuitions of fairness:

Within property law:

An inefficient initial assignment of property rights is considered to be fairer when respondents are told that low transaction costs will enable post-trial bargaining that can correct the inefficiency.

A court’s refusal to block a nuisance is considered to be less fair when the nuisance has higher measurable economic costs.

Within tort law:

Consistent with the prescriptions of the Hand rule, a ruling that an injurer is liable for failing to take due care is considered to be fairer when either the marginal cost of precaution is lower or the marginal benefit of precaution is higher.

The use of strict products liability is considered to be fairer when the company had the means to anticipate the accident compared to when the accident could not be anticipated.

Within contract law:

A court’s refusal to compel specific performance (and thereby allow breach of contract) is considered to be fairer when breach is efficient.

A court’s refusal to grant full expectation damages following a contract breach is considered to be fairer when the severity of the damages is not foreseeable to the breaching party.

Despite this strong overlap between fairness and law-and-economic prescriptions, however, I also identify two areas where they diverge. First, intuitions of fairness do not align with the economic prescription for the allocation of fugitive property. Second, a deterrence-based economic justification for punitive damages – using them to hold injurers liable for earlier, undetected accidents – likewise does not align with intuitions of fairness. Combined, the results from the fugitive-property and punitive-damages vignettes suggest that, in areas of the law where judgments that follow law-and-economic prescriptions require overriding or looking beyond salient moral intuitions regarding just deserts (fugitive property) or retribution (punitive damages), efficiency may be deprioritized.

The rest of the paper is organized as follows. The next section reviews earlier research that uses either vignettes or distribution games to examine connections between efficiency and fairness. A subsequent section will describe the methods. The design and results will then be presented across sections that speak to property law, tort law and contract law separately. The paper will close with a discussion of the results’ implications.

2 Efficiency, fairness and law and economics

Given that law-and-economic prescriptions aim to promote efficient outcomes, research into the perceived fairness of law-and-economic prescriptions will naturally extend existing work that examines preferences for efficiency. Vignette-based studies have been used to examine motives for efficiency, finding in general that these motives are pervasive yet context-dependent. Asking respondents to assess the fairness of various outcomes, Konow (2001) finds that, all else equal, outcomes that maximize total surplus are more likely to be considered fair. Yet, the results also indicated that concerns for merit-based deservingness were prioritized over efficiency when the two came into conflict. Skitka and Tetlock (1992) likewise identify a connection between efficiency and merit, as their respondents weighed efficiency heavily only when needy claimants were not responsible for their situations. Both Mitchell et al. (1993) and Scott et al. (2001) find that preferences for efficiency intensify as outcomes become more merit-based and once all citizens meet or exceed a poverty threshold. Matania and Yaniv (2007) find that more weight is given to efficiency in distributions of non-basic, higher-level resources (which are rated are being relatively less important).

Consistent with the findings from vignette-based studies, experiments that observe behavior in distribution games also point to the pervasiveness and context-dependency of motives for efficiency. Charness and Grosskopf (2001) and Kritikos and Bolle (2001) find that the majority of subjects in a modified dictator game prioritize surplus maximization over equality. Andreoni and Miller (2002) and Fisman et al. (2007) both identify widespread preferences for welfare maximization in dictator games that vary the values of tokens passed and held. Charness and Rabin (2002) show that welfare maximization is a pervasive social preference, especially when a decision maker stands to make more money than a counterpart in a given game. Both Fisman et al. (2007) and Charness and Rabin (2002) conclude that welfare-maximizing preferences are a stronger motive in distributive decisions than difference aversion.

Other experimental work has more closely examined the contexts under which preferences for welfare maximization are strongest. Chen and Li (2009), using minimal groups to create ingroups and outgroups, found that welfare maximization in distribution games is stronger (weaker) when choices involve ingroup (outgroup) members. Choshen-Hillel and Yaniv (2011, 2012) show that agentic decision makers (who have a role in creating an outcome) care more about maximizing welfare than non-agentic decision makers (who assess outcomes without influencing them). Martinsson et al. (2011) found that preferences for welfare maximization strengthen with age.

In light of the general finding that motives for efficiency are pervasive and context-dependent, the present study uses variation in context within and across vignettes to address how law-and-economic prescriptions for efficient legal rules, spanning areas of property law, tort law and contract law, align with lay intuitions of fairness. Although efficiency in the context of the existing literature refers to explicit surplus maximization in a particular instance, in law and economics, efficient prescriptions for legal rules maximize the total economic surplus given expected precedential influence on future interactions. Calabresi and Melamed (1972), in their seminal analysis of efficient methods of protecting property, rely upon Kaldor-Hicks efficiency in claiming that, “Economic efficiency standing alone would dictate that set of entitlements which favors knowledgeable choices between social benefits and the social costs of obtaining them, and between social costs and the social costs of avoiding them” (1096). Posner (1983, 1998) relies on the related, but narrower, criterion of wealth-maximization, which for either ethical or pragmatic reasons requires benefits and costs to be defined in terms of willingness to pay. Instead of being concerned with precise measures of costs and benefits or explicit recognition of what counts as wealth, Rubin (1980) argues that the common law is efficient to the extent that the rules that resolve disputes are the same rules that an economist would choose if she was singularly motivated to achieve efficiency. Hardin (1992) argues that law and economics is concerned with a dynamic notion of efficiency, whereby the law protects individuals’ interests by enabling productive activities and creating expectations that productive activity will be rewarded. Regardless of one’s chosen perspective on common law efficiency, however, law-and-economics analysis leads to the following shared set of legal prescriptions across contract law, property law and tort law: contract breach should be allowed when the cost of performance exceeds the benefit of performance; property rights should be assigned to parties who value them more highly when transaction costs prohibit private bargaining; negligence standards should be set such that the marginal cost of precaution is equal to the marginal benefit of precaution.

In addition to highlighting how efficiency fits into law and economics, it is also important to note how the conception of fairness used here and in earlier vignette-based studies, which relies on lay intuitions of the public, differs from another definition of fairness used in the law-and-economics literature. Shavell (2004) and Kaplow and Shavell (2002) formally define a fair outcome as one that is (1) intrinsically good, rather than being good because of an instrumental effect on welfare and (2) is associated with psychological states such as virtue, praise, guilt or disapproval. Shavell (2004) uses terms like fair, right, moral and correct interchangeably to connote this meaning. Despite the analytical value in separating fairness from concerns for welfare, however, the empirical fairness literature does not adhere to this dichotomous standard. Instead, across these studies, people are asked to consider whether particular outcomes align with their homegrown conception of what is fair.

Although the present study is novel in the way it broadly examines the perceived fairness of law-and-economic prescriptions across the common law, a few existing studies have examined related questions focusing on a particular legal domain. Wilkinson-Ryan and Baron (2009) find that survey respondents are more tolerant of efficient breach when the breach is loss-avoidant compared to when the breach gain-seeking. Bigoni et al. (2017) extend this result to an incentivized experiment and show that these intuitions are consistent with motives for both allocative and productive efficiency. Sunstein et al. (2000) find that support for damages awards following hypothetical personal injury cases does not follow prescriptions for optimal deterrence. The present study spans across different areas of the common law, using vignettes that model the fact patterns of ten seminal cases, to explore whether prescriptions from law and economics align with lay conceptions of fairness.

3 Methods

Participants were recruited and paid $0.40 through Amazon Mechanical Turk (MTurk). After signing up, they were directed to take the survey through Qualtrics. MTurk is intended to connect suppliers and demanders of basic labor tasks, and it has become popular for use in academic research. Earlier work has found MTurk workers to be representative and valid sources of data collection (Buhrmester et al., 2011; Mason and Suri, 2011). “Turkers” have also been shown to replicate earlier results from the heuristics and biases literature (Goodman et al., 2013; Paolacci et al., 2010) and to have inequality-averse social preferences that align with those expressed by university convenience samples (Beranek et al., 2015). Although the MTurk population is international, only people in the United States were eligible to participate in this study. The age of respondents ranged from 18 to 76, with the average age being 32.55. Of the 1213 respondents, 688 were male (56.7 percent), 523 were female (43.1 percent). 86.07 percent (50.37 percent) of respondents have some college experience (are college graduates). Consistent with the MTurk population, respondents tended to have low incomes with 72.05% (51.28%) earning an annual income below $45,000 ($30,000). Frequency distributions for respondents’ age, gender, education and income are displayed in Supplementary Figure S1 of the online appendix.

Surveys were administered in two waves. The first wave included 611 respondents who read and responded to vignettes that asked them to rate the fairness of rulings in cases involving Coasian bargaining, the Hand rule, strict products liability, punitive damages, and fugitive property. The second wave included 602 respondents who read and responded to vignettes that asked them to rate the fairness of rulings in cases involving competing claims to property, efficient breach of a contract, the foreseeability doctrine, and a modified version of the fugitive property case. Within each wave, respondents saw one of two versions of each vignette, with the version determined randomly. Respondents were not eligible to participate in both waves.

Vignettes, as described in detail below, are designed to simulate the critical features in the actual cases that are used to demonstrate how law and economics has been applied across property law, tort law and contract law. Across two versions of each vignette, a variable that is essential to the law-and-economic analysis is manipulated, either quantitatively or qualitatively, which causes the legal ruling in only one of the two instances to follow economic prescriptions. All vignettes are presented word-for-word below, with the differences across the two versions of each vignette being made clear. All vignettes end with the following prompt: “Indicate on the scale below how fair you think the decision in favor of X was.” Respondents then had to select one of six levels of fairness (completely unfair, very unfair, somewhat unfair, somewhat fair, very fair, or completely fair). For each vignette, the comparison of fairness ratings across the two versions demonstrates whether a null hypothesis (no difference in fairness ratings) can be rejected in favor of an alternative hypothesis that points to increased fairness ratings in the version that follows the economic prescription.

Although the design facilitates the measurement of differences in fairness ratings across the two versions of each vignette, results must be interpreted with caution; they cannot produce insight into whether participants are actually using law-and-economic reasoning when reaching their fairness perceptions. If the outcome in a version that follows an economic prescription is found to be fairer than in the version that does not follow the prescription, the only conclusion to be drawn is that participants’ fairness judgments are consistent with what someone using law-and-economic reasoning would find. When observed, such results would lend empirical support to the claims, described above, of Cooter and Ulen (2012), Cole and Grossman (2011), Mercuro and Medema (2006) and Shavell (2004) regarding the non-mutual-exclusiveness of morality and law and economics.

4 Property law

Table 1 lists, for each property-law vignette, the motivating case(s), a summary of the dispute, the ruling, the contextual features that cause the two versions to differ and the relevant concept from law and economics. The three property law vignettes (P1-P3) explore, in a general sense, whether legal rules that follow economic prescriptions for settling property disputes are seen as being fairer than legal rules that are inconsistent the prescriptions. Specifically, one vignette (P1), which is based on Sturges v. Bridgman ((11 ChD 852 [1879]), examined whether a potentially inefficient assignment is perceived as being fairer when low transaction costs facilitate Coasian bargaining after the trial. A second vignette (P2), based on Fontainebleau v. Forty-Five Twenty-Five (114 So2d 357 [1959]) and Prah v. Maretti (321 NW2d 182 [1982]), examined whether the perceived fairness of a rule that allows one party to obstruct another party’s use of sunlight depends on the economic costs of the obstruction. A third vignette (P3), based on Pierson v. Post (3 CaiR 175 [1805]), examined the fairness judgments involved with the assignment of property rights to fugitive property.

Descriptions of property-law vignettes.

| Motivating case(s) | The dispute | Ruling | Context not following economic prescription | Context following economic prescription | Concept from law and economics |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| P1. Sturges v. Bridgman | After a dentist builds an extension, a neighboring recording studio’s noise harms the dentist’s business. | Injunction granted in the dentist’s favor | High transaction costs will preclude post-trial bargaining | Low transaction costs will allow post-trial bargaining | Coasian bargaining |

| P2. Fontainebleau v. Forty-Five Twenty-Five Prah v. Maretti | A hotel’s new extension blocks the sunlight that a neighboring business receives. | The extension is allowed | The business uses sunlight for researching and developing solar panel technology | The business uses sunlight for employees who swim in a pool | Competing claims to property |

| P3. Pierson v. Post | A treasure hunter identifies the proper location and develops a strategy to find it. At the final stage, another party anticipates the hunter’s last move and dives for the treasure. | The property right is awarded to the party who first possessed it, despite the other party’s costly investment, | Identifying the treasure’s location and developing the strategy to dive for it required a few years of work. | Identifying the treasure’s location and developing the strategy to dive for it required a few hours of work. | Fugitive property |

4.1 Coasian bargaining – background

Property law concerns the assignment of property rights and the determination of remedies for property disputes. Law and economics provides guidance regarding the achievement of efficient assignment of rights and settlement of disputes. The seminal work of Coase (1960) brought transactions costs to the foreground of the analysis of externalities. In the absence of transaction costs, the legal assignment of rights will have no bearing on the ultimate allocation of rights; whether by legal assignment or post-trial bargaining, the party who values the property right more highly will obtain it.

In his analysis of externalities, Coase (1960) explicitly cited the case of Sturges v. Bridgman, which involved a property dispute between a dentist (who recently built an extension to his examination room) and a candy maker (whose noise now imposed an external cost on the dentist due to the fact that the new examination room was closer to the noise). Vignette P1, presented word-for-word in Supplementary Table S1 of the online appendix and summarized in the first row of Table 1, is based directly on the details of this case. Smith Recording Studio is a successful business located next to Jones Dentistry. Jones has recently built an extension that makes his waiting room closer to the studio. After the extension, noise now drives away a few of Jones’s customers and takes away a small portion of business. Respondents are told that the dispute goes to a trial, and that a judge rules in the dentist’s favor; the ruling implies that the recording studio will have to shut down unless the two parties can reach a deal whereby the dentist allows the studio to remain open and the studio compensates the dentist for the lost business from the noise. The two versions differ, however, in the level of transaction costs that affect the post-trial bargaining process. In the version that does not follow the economic prescription, respondents are told, at the very end of the story, that the owners of the dentistry and the studio are unlikely to reach a deal because they are enemies. In the version that follows the economic prescription, respondents are told that the two parties are friendly and a deal that allows the studio to stay open would be extremely likely. Given the logic of the Coase theorem, the judge’s ruling in the low-transaction-cost version is efficient in that it will not require the successful business to shut down. The ruling in the high-transaction-cost version, in contrast, is inefficient because it causes a successful business to shut down rather than allow it to impose small external costs on the dentist.

4.2 Coasian bargaining – results

Across both versions of P1, deontological attitudes toward external costs, property rights, victimization and the merits of noise complaints could shape respondents’ fairness perceptions of the ruling against the noisy business. Any difference in responses across the two versions will point to the varying conditions for Coasian bargaining exerting an additional effect on perceptions of fairness.

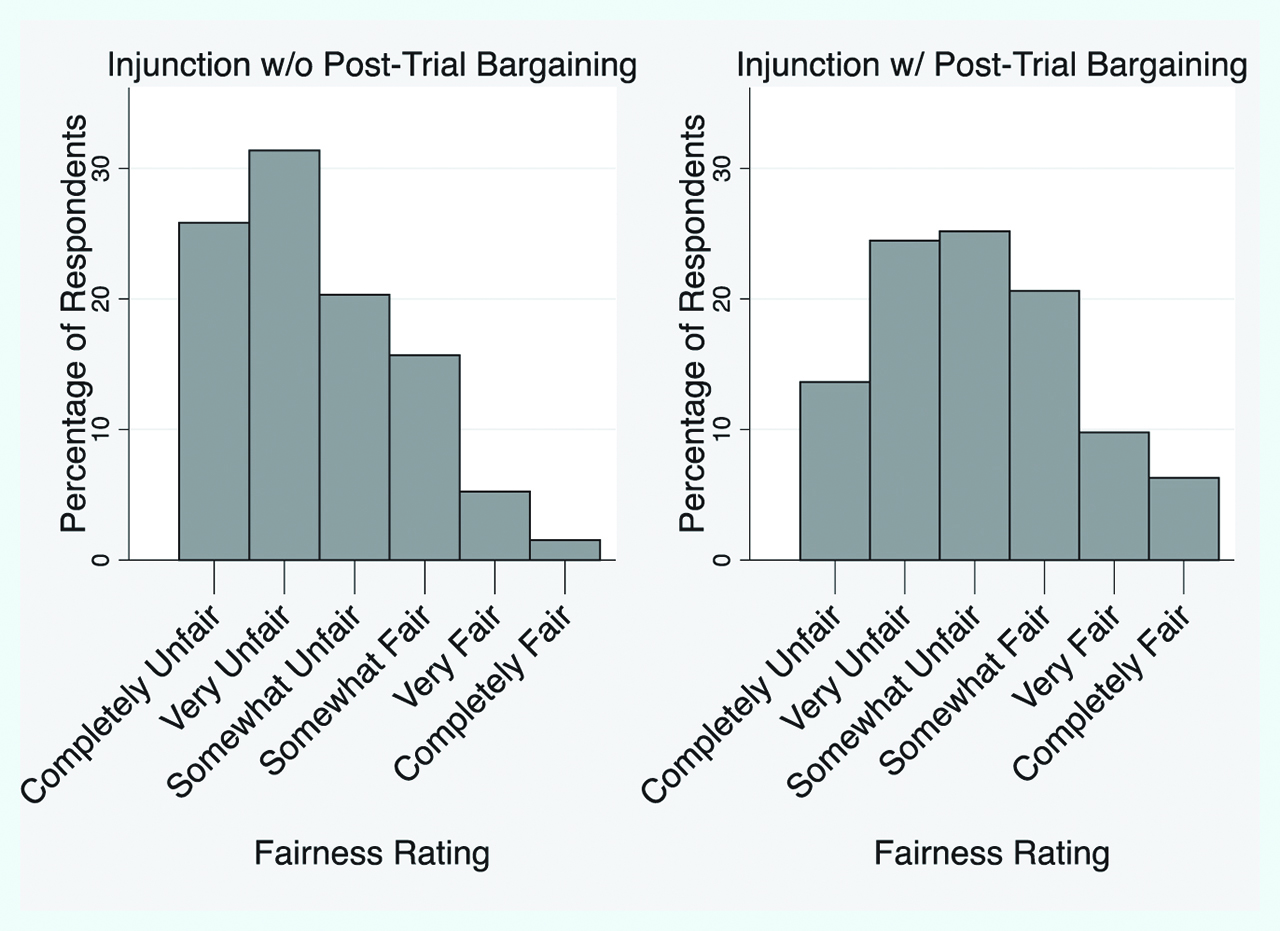

The first row of Table 2 shows the descriptive statistics and Mann-Whitney test that shed light on whether the economic prescription for Coasian bargaining aligns with intuitions of fairness. Figure 1 shows frequency distributions of responses across the two versions.

Distributions of fairness assessments – Coasian bargaining following an injunction.

Property-law vignettes (summary statistics and Mann-Whitney tests).

| Scenario | Ruling | Context not following economic prescription | Context following economic prescription | Mann-Whitney U Statistic (p-value) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | Mean fairness rating | Median fairness rating | n | Mean fairness rating | Median fairness rating | |||

| P1. After a dentist builds an extension, a neighboring recording studio’s noise harms the dentist’s business. | Injunction granted in the dentist’s favor | 325 | 2.47 | 2 | 286 | 3.07 | 3 | 5.31 (<0.0001) |

| P2. A hotel’s new extension blocks the sunlight that a neighboring business receives. | The extension is allowed | 276 | 3.09 | 3 | 326 | 3.61 | 3.5 | 4.993 (<0.0001) |

| P3. Someone free rides off of the initial investment of a treasure hunter to acquire the treasure | The free-riding party is allowed to keep possession | 614 | 3.44 | 3 | 599 | 3.48 | 3 | 0.47 (0.6395) |

Fairness ratings are on a 1–6 scale (1=completely unfair; 2=very unfair; 3=somewhat unfair; 4= somewhat fair; 5= very fair; 6= completely fair). Mann-Whitney tests compare the distributions of fairness decisions in the inefficient and efficient contexts.

When high transaction costs prohibit post-trial bargaining, the median and modal response to a ruling that requires the studio to shut down is “very unfair.” In contrast, when low transaction costs lead to likely post-trial bargaining, the median and modal response is “somewhat unfair.” Results from a Mann-Whitney test (U = 5.31, p < 0.0001) that compares the distribution of responses across the two versions identify a highly significant difference. Comparing the two frequency distributions from Figure 1, there is a rightward shift in fairness ratings, indicating stronger levels of perceived fairness, as the outcome shifts from inefficient to efficient. These results demonstrate that, in this particular context, the economic prescription for allocating property rights in the shadow of post-trial bargaining aligns with intuitions of fairness. A judge who employs Coasian logic – being concerned with transaction costs and the likelihood that bargaining will facilitate efficient outcomes – acts in accordance with lay intuitions of fairness.

4.3 Competing resource claims – background

Vignette P2, summarized in the second row of Table 1 and presented word-for-word in Supplementary Table S2, describes a judge settling a dispute over competing claims to a resource; it is based on two cases that involve disputes over the blockage of sunlight. The two cases illustrate how precedents evolved in response to evolving economic conditions. In the earlier case, Fontainebleau Hotel Corp. v. Forty-Five Twenty-Five, Inc., one hotel’s planned vertical extension would restrict the sunlight that another hotel’s pool received. The court allowed the extension, denying the claim that any one party could possess a right to sunlight. In the later case, Prah v. Maretti, the opposite conclusion was reached when a disputed extension would have reduced the amount of sunlight that an owner of a solar-powered house would receive. Using economic logic in the decision, the court in Prah sought a ruling that would not inhibit the development of new industries that relied upon sunlight.

Motivated by these cases, the vignette’s two versions parallel the core difference between Fontainebleau and Prah. In each version, Evergreen Hotel and Jackson Lab are neighbors; Evergreen Hotel is planning on building an extension that would partially block the sunlight that Jackson Labs would receive. In both versions, the court rules against Jackson Labs, allowing the extension to be built. In the version that follows the economic prescription, modeled after Fontainebleau, sunlight is important to Jackson Labs because its employees use a pool on the premises for exercise. In the version that does not follow the economic prescription, modeled after Prah, sunlight is important to Jackson Labs because they conduct research on solar panels. Comparatively, a difference exists to the extent that inhibiting promising research and development is more likely to negatively impact the size of the objective economic surplus compared to inhibiting recreational activity. In the written opinion in Prah, Chief Justice Shirley Abrahamson of the Supreme Court of Wisconsin relied on this logic explicitly, noting that, “Access to sunlight as an energy source is of significance both to the landowner who invests in solar collectors and to a society which has an interest in developing alternative sources of energy.”

4.4 Competing resource claims – results

Across both versions of P2, deontological attitudes toward property rights, specifically the importance of first possession and the willingness to tolerate external costs imposed on others, could shape respondents’ fairness perceptions of the ruling that allows the obstruction of sunlight. Any difference in responses across the two versions will point to the varying benefit of sunlight exerting an additional effect on perceptions of fairness.

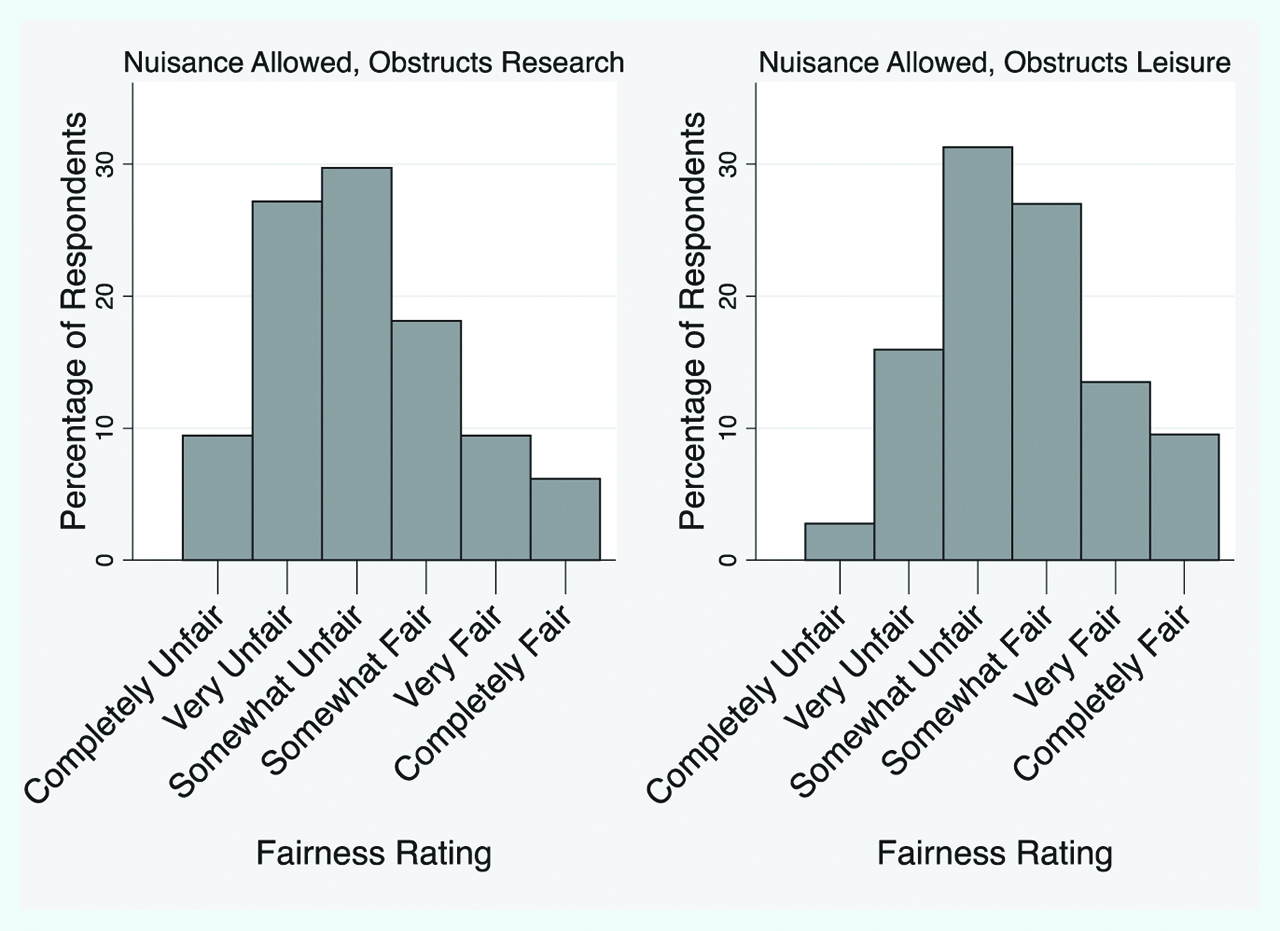

The descriptive statistics and Mann-Whitney test that shed light on whether the economic prescription for assigning property rights amidst competing land uses are found in the second row of Table 2. Figure 2 shows frequency distributions of responses across the two versions. The judge’s decision to allow the extension in the version that does not follow the economic prescription (when the extension impedes scientific research) is considered to be less fair than the same decision made in the version that follows the prescription (when the extension impedes employee leisure). The median and modal response when the ruling does not follow the prescription is “somewhat unfair.” Although the version that follows the economic prescription has the same modal response, the median response when the ruling follows the prescription is 3.5, which is between “somewhat unfair” and “somewhat fair” due to the greater frequency of “somewhat fair” responses A Mann-Whitney test (U = 5.31, p < 0.0001) indicates that the difference in perceived fairness between the two versions is highly significant. The rightward shift in fairness ratings across the two frequency distributions in Figure 2 shows how perceptions of fairness change across the two versions. Overall, the difference in fairness ratings across the two versions demonstrates that, in this particular context, following the economic prescription for allocating property rights in the face of competing resource claims aligns with perceptions of fairness. An assignment of property rights that allows a nuisance is perceived as being increasingly unfair when the nuisance inhibits beneficial economic activity.

Distributions of fairness assessments – competing claims to sunlight.

4.5 Fugitive property – background

Vignette P3, described in the last row of Table 1 and presented word-for-word in Supplementary Table S3, explores whether perceptions of fairness align with economic prescriptions for allocating fugitive property. The vignette is based on Pierson v. Post, which involved a dispute between a foxhunter and an opportunist who tracked the actions of the hunter and took possession of the fox after the hunter had cornered it (and just before the hunter could complete the final stage in the hunt). The court held that the property right belonged to the free-riding party, in part because of the difficulty associated with identifying possession at an earlier stage. A dissenting judge, however, using economic logic, explicitly described how, since foxhunting was time-consuming and costly, the court’s ruling would adversely affect the incentives to hunt.

The vignette in the survey replaces the foxhunting context with the search for a treasure. Like the actual case, a free-rider acquired possession of a resource and the court allowed him to keep it. In the version that does not follow the economic prescription, the treasure hunter spent years tracking the treasure and developing a strategy to find it; in the version that follows the economic prescription, the tracking and strategy development took place over a few hours. Across both versions, the ruling that allows the opportunist to maintain possession would reduce the incentives for treasure hunters to engage in costly search. But, when search takes place across a few years, the ruling would have a more perverse effect on the decision to search. In contrast, when the treasure hunter only stands to lose a few hours of work if an opportunist free rides off of the initial investment, the perverse effect on incentives would not be as severe. Since the treasure is a valuable resource, someone who prioritizes the effect of incentives would be less likely to support the ruling when years, as opposed to hours, of search are preempted.

4.6 Fugitive property – results

Across both versions of P3, deontological attitudes toward rewarding effort and penalizing opportunism could shape respondents’ fairness perceptions of the ruling that rewards the free-riding party. Any difference in responses across the two versions will point to the variation in the initial time of investment exerting an additional effect on perceptions of fairness.

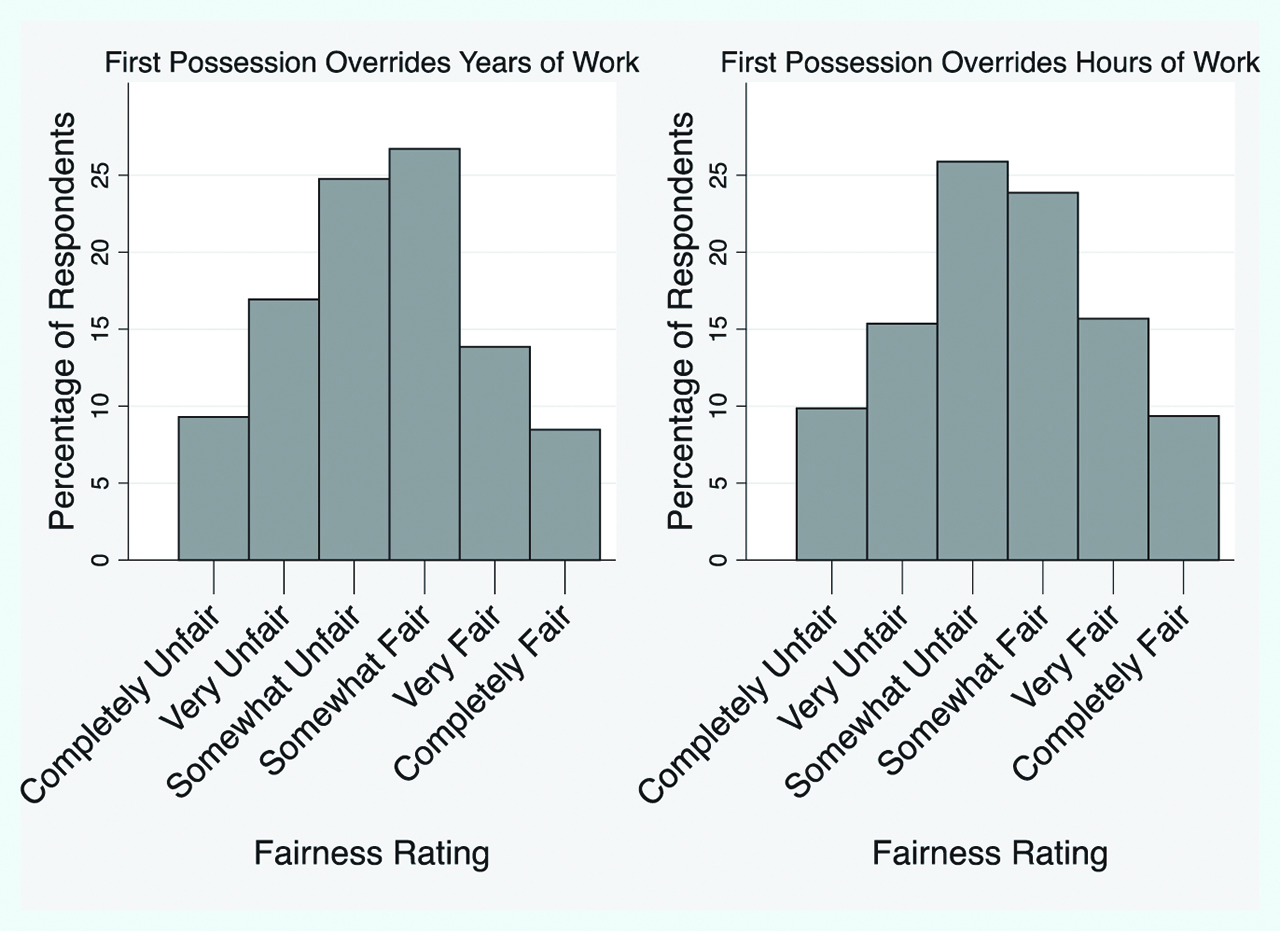

The third row of Table 2 shows the results from P3. Figure 3 shows frequency distributions of responses across the two versions. Median fairness ratings in both versions are both “somewhat unfair,” and the mean ratings across the two conditions are statistically indistinguishable (3.44 compared to 3.48). A rank-sum test that compares the two distributions shows no difference (U = 0.47, p = 0.6395); the comparison of the two frequency distributions likewise shows no shift in perceived fairness. The ruling in favor of the freeriding party, therefore, is considered to be equally unfair regardless of whether the investment that lead to the discovery of the fugitive property took place over a few years or over a few hours. Unlike the results with respect to Coasian bargaining and disputes over competing claims, the perceived fairness in a scenario where first possession overrides initial investment does not align with economic prescriptions for assigning rights to fugitive property.

Distributions of fairness assessments – fugitive property.

5 Tort law

Table 3 provides a summary for the four tort-law vignettes (T1-T4). Each of these vignettes addresses whether legal rules that follow economic prescriptions when assigning liability are seen as being fairer than legal rules that are inconsistent with these prescriptions. One tort vignette (T1), based on Davis v. Consolidated Rail (788 F2d 1260 [1986]), tested whether the perceived fairness of an assignment of liability depends on the marginal benefit of precaution; a second tort vignette (T2), based on Winn Dixie Stores, Inc. v. Benton (576 So2d 359 [1991]), tested whether the perceived fairness of an assignment of liability depends on the marginal cost of precaution. A third tort vignette (T3), based on an opinion written for Escola v. Coca Cola Bottling Co. (24 Cal2d 453, 150 P2d 436 [1944]), addressed whether the perceived fairness of strict product liability depends on whether producers possess the technological capacity to recognize and prevent accidents. A fourth tort vignette (T4), based on the reasoning explored in Sturn Ruger v. Day (594 P2d 38 [1979]), examined whether the fairness of awarding punitive damages depends on the deterrence value of the damages.

Descriptions of tort-law vignettes.

| Motivating case(s) | The dispute | Ruling | Context not following economic prescription | Context following economic prescription | Concept from law and economics |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| T1. Davis v. Consolidated Rail | A railroad yard worker is injured when a train moves prematurely. | The yard owner is liable for the accident and must pay damages | It is highly unlikely that the horn would have prevented the accident | It is highly likely that the horn would have prevented the accident | Hand rule (marginal benefit of precaution) |

| T2. Winn Dixie Stores, Inc. v. Benton | A customer in a supermarket slips on a puddle of spilled milk and breaks her leg. | The store is liable for the accident and must pay damages | The accident happened one minute after the spill | The accident happened thirty minutes after the spill | Hand rule (marginal cost of precaution) |

| T3. Escola v. Coca Cola Bottling Co | A consumer is injured while operating a lawnmower. | The manufacturer is liable for the accident and must pay damages | The company’s research team could not have anticipated this type of accident | The company’s research team could have anticipated this type of accident | Strict products liability and information |

| T4. Sturn Ruger v. Day | A defective toy injures a child and causes $10,000 in medical bills. The toy company knew about the defect but did nothing to fix it. | The jury awarded $10,000 in compensatory damages and $10 million in punitive damages. | This defective toy injured two other children, but charges were not filed. | This defective toy injured 900 other children, but charges were not filed. | Punitive damages and deterrence |

5.1 Hand rule – background

Justice Learned Hand, in U.S. v. Carroll Towing, Co. (169 F2d 169 [1947]), explicitly relied on economic logic when deciding whether a barge owner should be liable for the collision and ultimate sinking of the ship. Hand argued that a standard of reasonable care would have been met if the burden of precaution (B) was less than the expected accident cost without precaution, found by multiplying the probability of an accident without precaution (P) and the losses from an accident (L). Brown (1973) translated Hand’s logic into marginal terms; B can be interpreted as the marginal cost of more precaution, while PL can be interpreted as the marginal benefit that comes from decreased expected accident costs.

Two vignettes, based on two separate cases, explore the perceived fairness of the Hand rule’s logic for determining whether standards of care were met. One vignette explores how fairness assessments change as the marginal benefit of an act of precaution changes (P*L given the terms listed above). A second vignette addresses how intuitions of fairness change given different marginal costs of precaution (the B term listed above).

5.2 Hand rule – marginal benefit of precaution

Davis v. Consolidated Rail serves as an example in which a judicial opinion considers the marginal benefit of an act of precaution that was not taken. Writing the court’s decision for this case, Posner employed the Hand-rule calculus to determine if a railroad company was liable for damages caused when a railroad car ran over the leg of an employee who was inspecting underneath a train. Hearing the case on appeal, Posner’s decision explains that the court could find no legitimate reason to overturn an initial ruling that found the railroad liable. Using the terms described above, Posner reasoned that the jury could have reasonably concluded that the marginal cost of precaution was less than the marginal benefit of precaution, as it would have been easy to blow a warning horn before moving the train and doing so would have substantially decreased the probability of an accident occurring. The jury was therefore reasonable to conclude that the railroad should be liable for not taking sufficient care.

The storyline in vignette T1, presented word-for-word in Supplementary Table S4 and summarized in the first line of Table 3, closely follows the case of Davis V. Consolidated Rail. Across both versions, the court finds the owner of the railway yard liable because the owner of the yard should have sounded an alarm before moving the train. The vignette tests the importance of the marginal benefit of precaution by varying the probability that an act of precaution would have prevented the accident. In the version that follows the economic prescription, the alarm would have been unlikely to decrease the probability of an accident; in the version that follows the prescription, the alarm would have likely decreased the probability of an accident. Thus, using the logic of the Hand rule, it would be inefficient to hold the yard owner liable for damages when the marginal benefit of precaution is low, which is the case when the alarm is not likely to matter. Likewise, it would be efficient to find liability when the action that could have been taken would have been likely to prevent the accident. A comparison of fairness ratings across these two versions can show whether intuitions of fairness align with the prescriptions for efficiency, in terms of the marginal benefit of taking precaution, set out by the Hand rule.

5.3 Hand rule – marginal cost of precaution

Winn Dixie Stores, Inc. v. Benton, involved a court considering the marginal cost of accident avoidance. The case involved a slip-and-fall on a puddle of milk in a supermarket. The opinion highlights how the length of time that the puddle was on the floor was the driving factor determining whether the store should be liable for the accident. Based on evidence that the floor had not been swept for 30 minutes prior to the accident, the appeals court upheld the original jury’s finding that the store did not exercise due care. Because intermittent sweeping is not an overly burdensome task, and because such sweeping would have drastically decreased the likelihood of an accident, the logic of the Hand rule points to a finding of negligence.

Vignette T2, presented word-for-word in Supplementary Table S5 and summarized in the second line of Table 3, is directly based on this case. A shopper slips and falls on a puddle of milk, and the court finds the store liable for the accident. In the version that does not follow the economic prescription, the marginal cost of precaution was high; the spill happened one minute after that accident, so it would have been difficult for the store to prevent the fall. In the version that follows the economic prescription, the marginal cost of precaution was low, as the accident happened thirty minutes after the spill and it would have been easy for the store to prevent the accident by cleaning the spill. Differences in fairness ratings across these two versions of the vignette can shed light on whether intuitions of fairness align with variation in the cost-justification of accident prevention.

5.4 Hand rule – results

Across both versions of vignettes T1 and T2, deontological attitudes toward responsibility, labor relationships (for T1), consumer protection (for T2) and compensation for harm could shape respondents’ fairness perceptions of liability. Additionally, given that assignment of liability involves payment of monetary damages, attitudes toward income redistribution could also affect fairness perceptions across the two versions of each vignette. Any difference in responses across the two versions for each respective vignette will point to the variation in the marginal benefit (for T1) or the marginal cost (for T2) of precaution exerting an additional effect on perceptions of fairness.

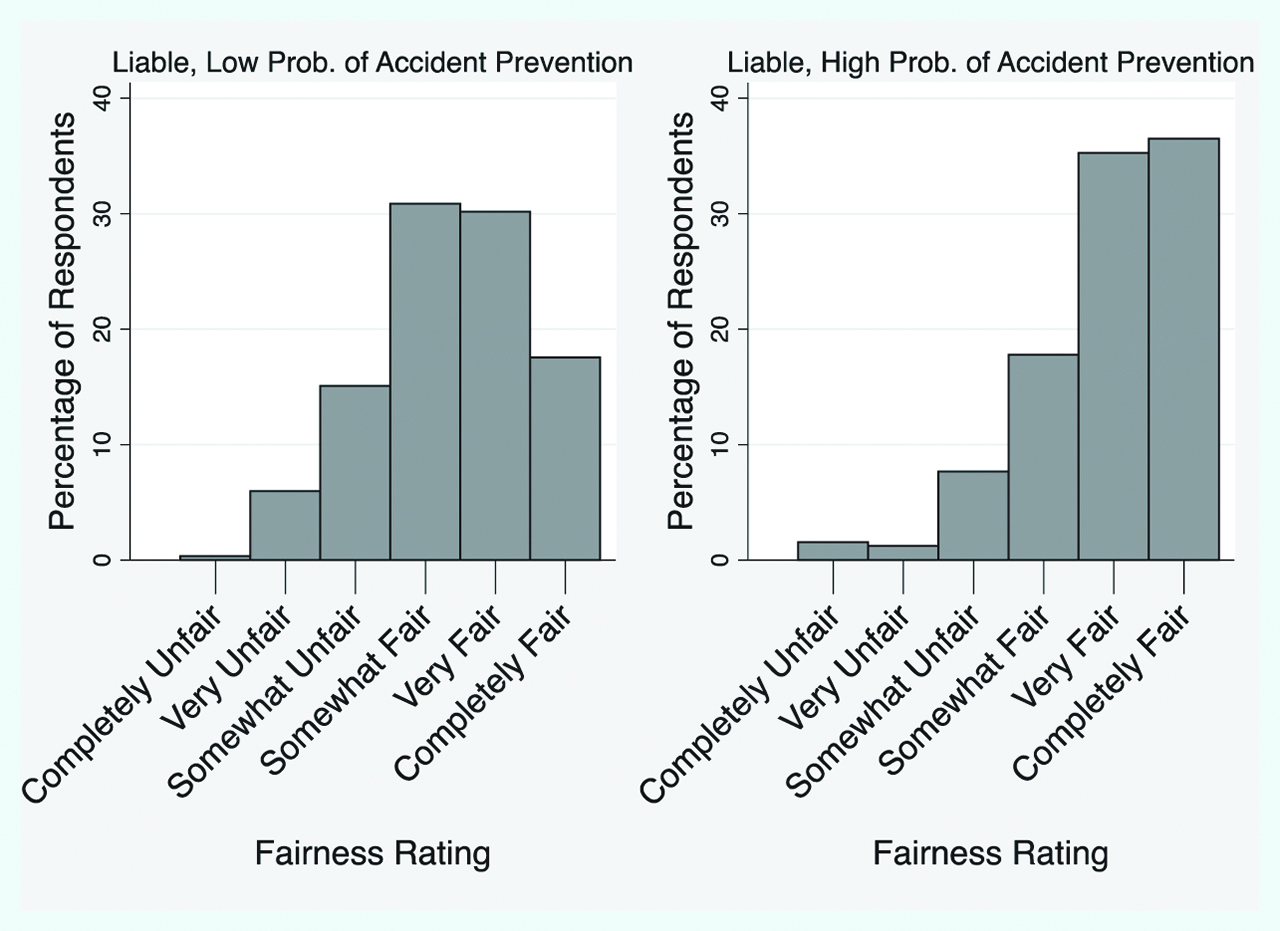

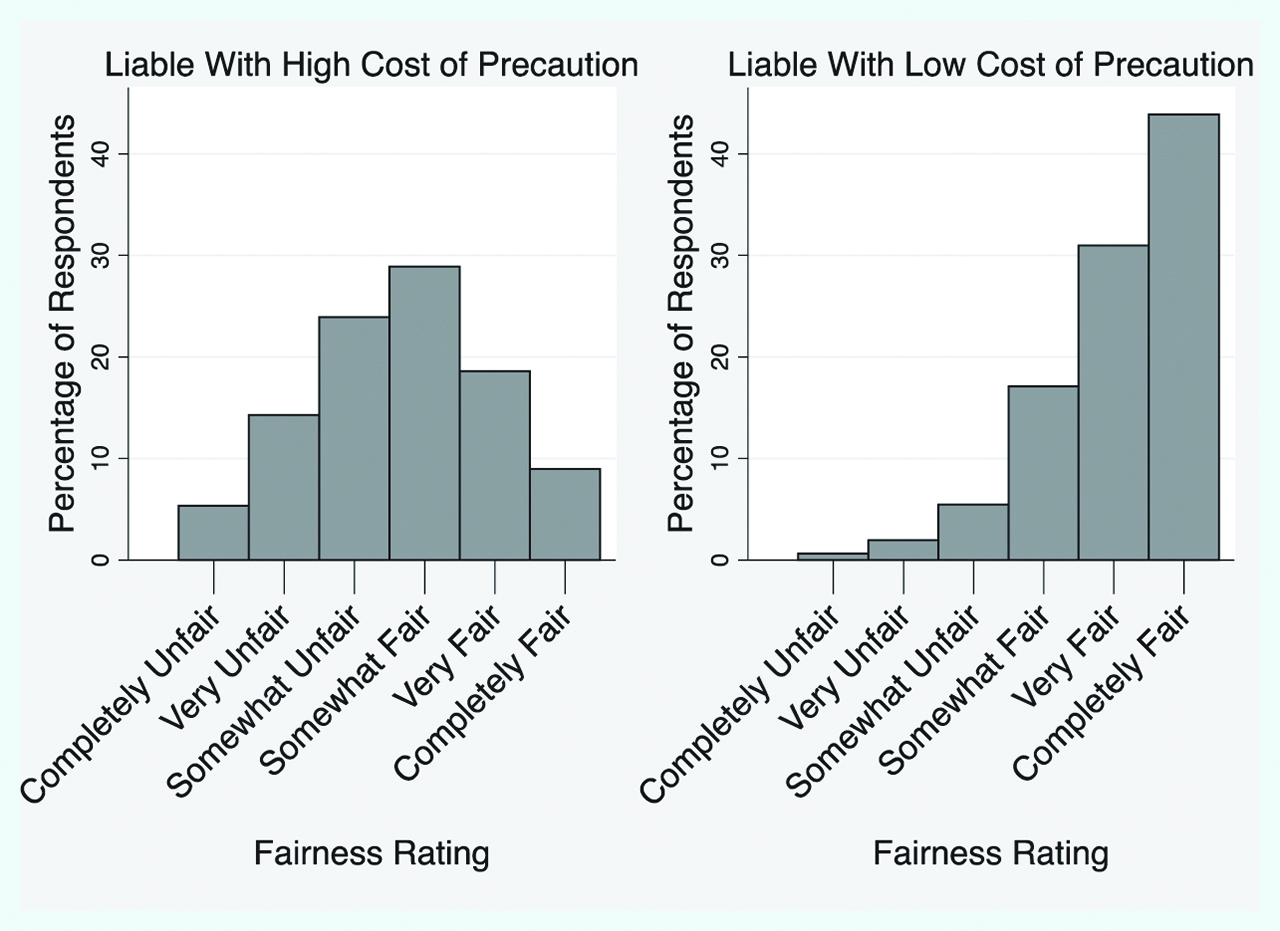

Vignettes T1 and T2 both show strong support that intuitions of fairness align with the prescriptions for efficiency implied by the Hand rule. The first and second rows of Table 4 show the relevant statistical results. Analyzing how perceptions of fairness vary with the marginal benefit of precaution, the first row shows that the median fairness rating of the finding of liability is “somewhat fair” when the alarm in vignette T1 was unlikely to matter. Median perceived fairness increased, however, to “very fair” when the alarm probably would have prevented the accident. The Mann-Whitney test in the right-most cell in the first row shows that the difference between the two versions is highly significant (U = 6.53, p < 0.0001). The distribution functions shown in Figure 4 provide further evidence of the shift in fairness ratings across the two versions, with the modal response shifting from “somewhat fair” to “completely fair.”

Distributions of fairness assessments – Hand-rule, marginal benefit of precaution.

Tort-law vignettes (summary statistics and Mann-Whitney tests).

| Scenario | Ruling | Context not following economic prescription | Context following economic prescription | Mann-whitney U statistic (p-value) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | Mean fairness rating | Median fairness rating | n | Mean fairness rating | Median fairness rating | |||

| T1. A railroad yard worker is injured when a train moves prematurely. | The yard owner is liable for the accident and must pay damages | 285 | 4.37 | 4 | 326 | 4.94 | 5 | 6.53 (<0.0001) |

| T2. A customer in a supermarket slips on a puddle of spilled milk and breaks her leg. | The store is liable for the accident and must pay damages | 301 | 3.68 | 4 | 310 | 5.07 | 5 | 12.78 (<0.0001) |

| T3. A consumer is injured while operating a lawnmower. | The manufacturer is liable for the accident and must pay damages | 309 | 3.43 | 3 | 302 | 4.83 | 5 | 12.58 (<0.0001) |

| T4. A child is injured by a defective toy | The child’s family is awarded compensatory damages and $10 million in punitive damages | 303 | 4.30 | 4 | 308 | 4.26 | 4 | 0.25 (0.7274) |

Fairness ratings are on a 1–6 scale (1=completely unfair; 2=very unfair; 3=somewhat unfair; 4=somewhat fair; 5=very fair; 6=completely fair). Mann-Whitney tests compare the distributions of fairness decisions in the inefficient and efficient contexts.

The same pattern is observed when analyzing the perceived fairness ratings in vignette T2. The second row of Table 4 shows that the median rating for the finding that the grocery store should be liable following the slip-and-fall is “somewhat fair” when the accident could have only been avoided at a substantial cost. But when the accident could have been prevented at a lower cost, the median fairness rating of the liability ruling increases to “very fair.” A Mann-Whitney test shows that this difference is highly significant (U = 12.78, p < 0.0001), and Figure 5 further demonstrates the shift in fairness ratings across the two versions, with the modal response again shifting from “somewhat fair” to “completely fair.”

Distributions of fairness assessments – Hand-rule, marginal cost of precaution.

5.5 Strict products liability – background

While the Hand rule uses economic reasoning to specify whether standards of due care have been met, economic reasoning has also been used to determine when companies should be held strictly liable for accidents that they cause. In a concurring opinion written in Escola v. Coca Cola, a 1944 case where Coca Cola was found liable for injuries caused by an exploding bottle, Justice Traynor of the Supreme Court of California notes that strict liability is the appropriate remedy in situations where manufacturers can anticipate hazards and guard against them. Moreover, Traynor argues that, as mass production increasingly came to replace individualized handicrafts, consumers’ ability to understand the soundness of a product had eroded. With manufacturers aware of the risks and in a position to guard against them, and consumers becoming increasingly reliant on branding and trademarks rather than vigilantly inspecting products’ quality, strict liability would create incentives for manufacturers to internalize the cost of accidents that they cause.

This logic implies that the use of strict liability promotes optimal levels of care when manufacturers are in a position to recognize and protect against risks; under such conditions, strict liability provides manufacturers with an incentive to minimize the total costs of accidents (i. e. the costs of precaution plus the losses from accidents). Otherwise, if producers are not in a position to recognize and avoid accidents, strict liability leads to excessive prices and frequency of disputes, and fails to provide incentives for users to take appropriate care. Vignette T3, which is presented word-for-word in Supplementary Table S6 and summarized in the third row of Table 3, explores whether the use of strict liability is considered to be fairer when it follows the economic prescription. The vignette uses a situation involving an accident caused by a lawnmower; the court finds the manufacturer liable for the harm that an accident causes. In the version that does not follow the economic prescription, the company could not have anticipated the accident; in the version that follows the economic prescription, the company could have anticipated the accident. Comparing fairness assessments of the liability ruling across the two versions can shed light on whether the use of strict liability is considered to be fairer when the nature of the information available to manufacturers generates a situation in which strict liability promotes optimal levels of care.

5.6 Strict products liability – results

Across both versions of T3, deontological attitudes toward responsibility, consumer protection and compensation for harm with respect to the use of consumer products could shape respondents’ fairness perceptions of liability. Similar to T1 and T2, attitudes toward income redistribution could also affect fairness perceptions across the two versions. Any difference in responses across the two versions will point to the variation in the manufacturer’s information exerting an additional effect on perceptions of fairness.

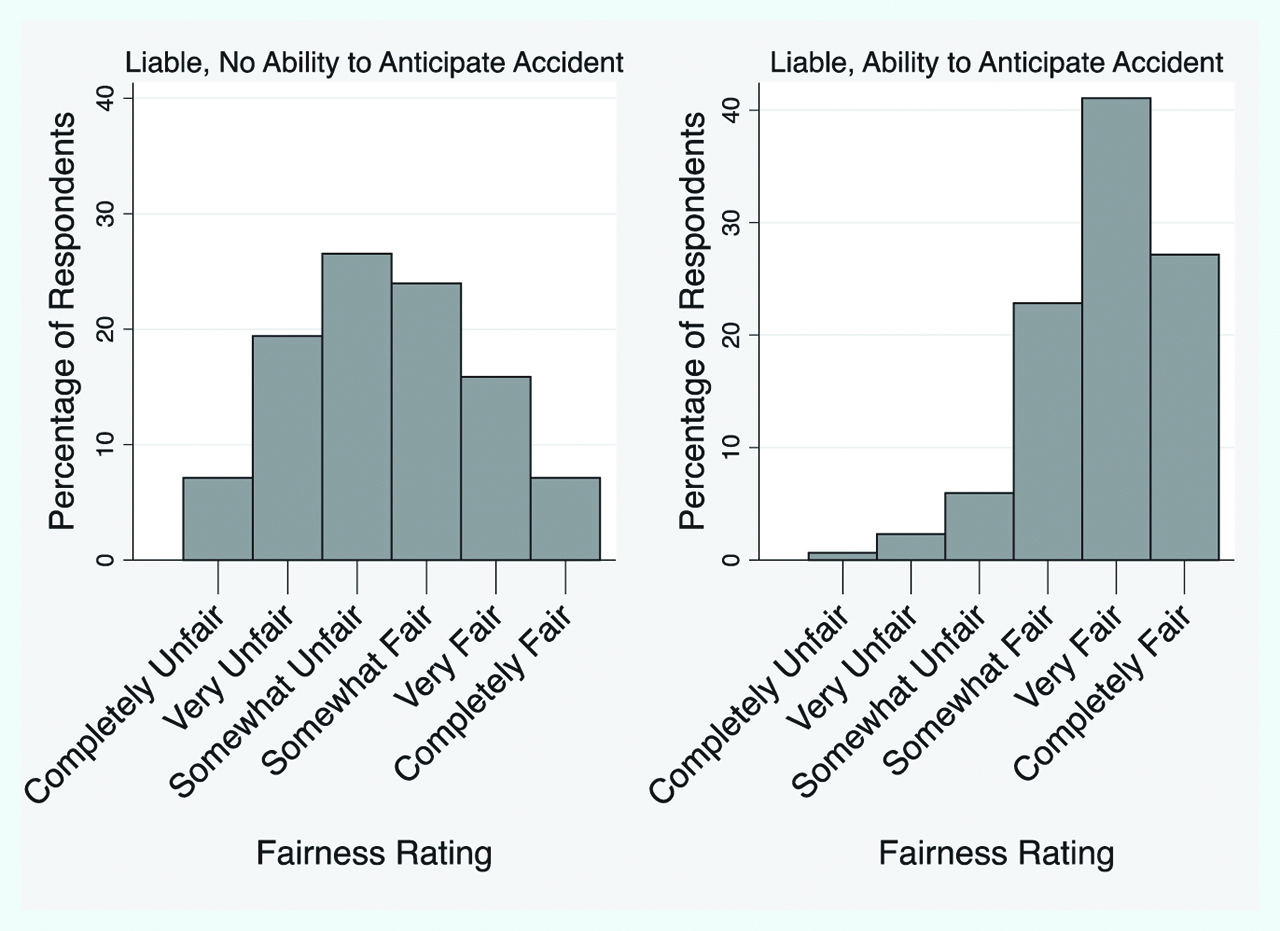

The third row of Table 4 shows the results for scenario T3. Figure 6 shows frequency distributions of responses across the two versions. The median and modal fairness rating of the liability ruling in the version that does not follow the economic prescription – when the manufacturer could not have anticipated the accident – is “somewhat unfair.” In the version that follows the economic prescription, when the manufacturer was in a position to anticipate the accident and protect against it, the median and modal ratings increase to “very fair.” A Mann-Whitney test, displayed in the right-most column in the third row, shows that this difference is highly significant (U = 12.58, p < 0.0001). The comparison of frequency distributions from Figure 6 provides further evidence of the shift in fairness ratings. The difference across the two versions indicates that respondents perceive the usage of strict liability to be fairer when the producer has the information needed to take an optimal level of care.

Distributions of fairness assessments – strict products liability.

5.7 Punitive damages – background

The use of punitive damages is the final area of tort law that was addressed. As argued in the decision written for Sturn Ruger v. Day, and described by Friedman (2000) and Polinsky and Shavell (1998), punitive damages can promote optimal levels of care when compensatory damages do not adequately deter accidents; such is the case when an injurer causes harms that go undetected. Otherwise, if all accidents lead to legal claims, punitive damages that go beyond compensatory damages would lead to over-deterrence. The economic prescription, therefore, is that punitive damages should be greater when, all else equal, a company causes many earlier, undetected injuries compared to when a smaller number of undetected injuries occurred. Vignette V4, presented word-for-word in Supplementary Table S7 and summarized in the fourth row of Table 3, tests whether intuitions of fairness align with this prescription for the use of punitive damages. In the vignette, a toy injures a child and the child’s family is awarded both compensatory damages ($10,000) and “an additional $10 million to punish the company for its dangerous and reckless behavior.” In the version that does not follow the economic prescription, respondents are told that there is evidence that the toy company injured two other children, but the company was not held responsible for these earlier injuries because the families of these other injured children did not seek compensation. The version that follows the economic prescription is exactly the same, except that there are 900 earlier uncompensated injuries rather than only two. In the condition with 900 earlier injuries, punitive damages would be necessary for deterring accidents given the low probability that an accident would result in a legal claim. This vignette, therefore, tests whether the economic prescription for the use of punitive damages is also regarded as the fairer use of punitive damages.

5.8 Punitive damages – results

Across both versions of vignette T4, deontological attitudes toward punishment, child welfare, consumer protection, compensation for harm and corporate/parental responsibility could shape respondents’ fairness perceptions of punitive damages. Similar to the other tort vignettes, attitudes toward income redistribution could also affect perceptions of fairness across both versions. Any difference in responses across the two versions will point to the variation in the scope of the harm exerting an additional effect on perceptions of fairness.

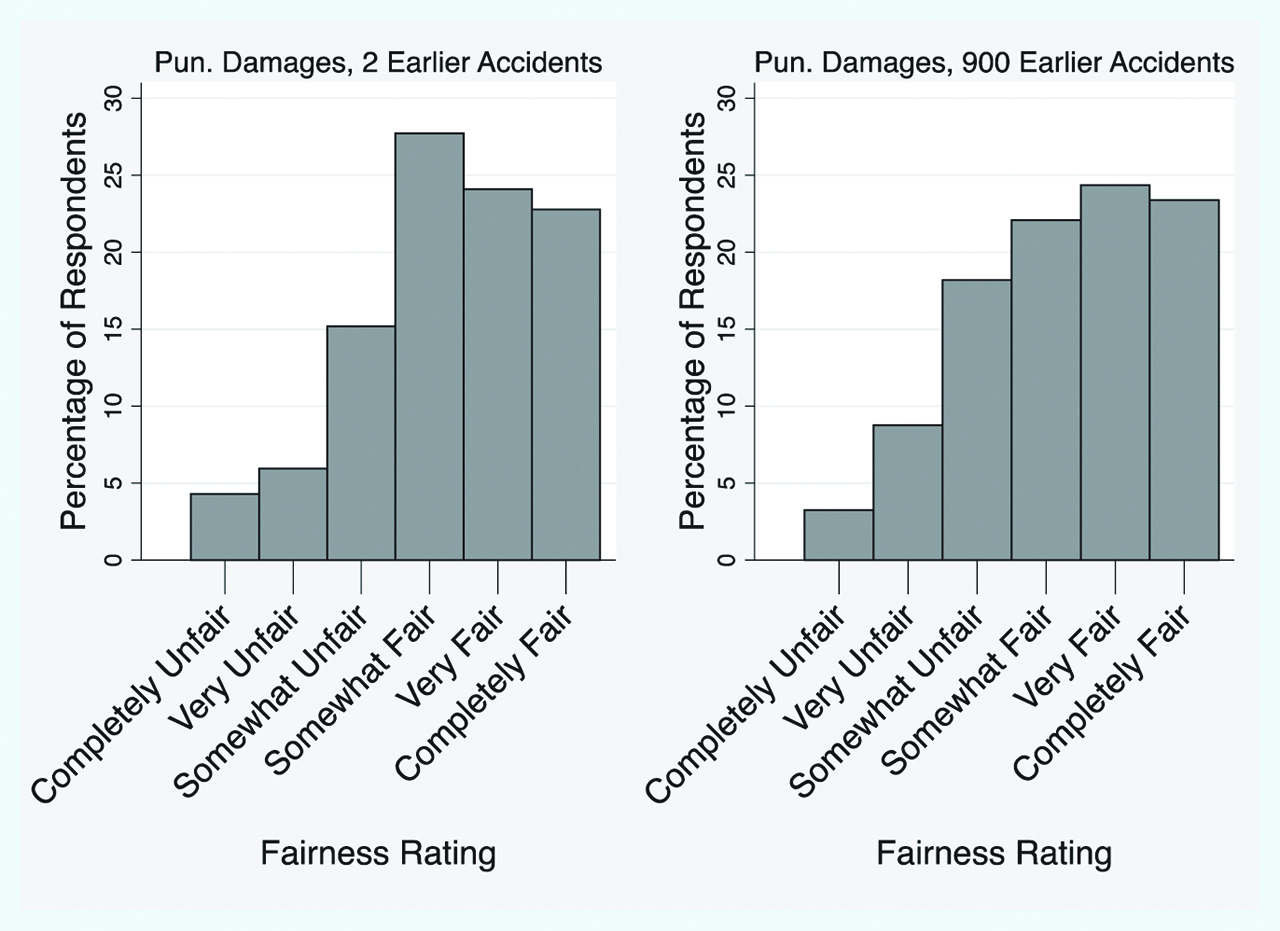

The results from vignette T4 show that respondents who are asked to judge the fairness of a punitive damage award do not take the frequency of earlier, undetected injuries into account. The relevant statistics are displayed in the fourth row of Table 4. Median fairness ratings across the two versions are both “somewhat fair,” and the mean ratings are statistically indistinguishable (4.30 compared to 4.26). The Mann-Whitney test, shown in the right-most column of the fourth row of Supplementary Table S2, shows that the distributions of fairness ratings are not statistically different (U = 0.25, p < 0.7274); the frequency distributions of fairness ratings, shown in Figure 7, show only subtle changes across the two versions. In contrast to the other areas of tort law that show evidence of fairness and economic prescriptions aligning, the perceived fairness of a punitive damage award is invariant to the deterrence value that the economic prescription prioritizes.

Distributions of fairness assessments – punitive damages.

6 Contract law

Table 5 provides a summary of two contract-law vignettes (C1 and C2). One vignette (C1), based on Eastern S. S. Lines, Inc. v. United States (187 F2d 956 [1951]), addresses whether the perceived fairness of a legal rule that allows breach of contract with damages (rather than forces specific performance) is greater when breach is efficient; a second vignette (C2), based on Hadley v. Baxendale (9 Ex 341 [1854]), addresses whether high expectation damages following a breach are perceived as being fairer when the damages are foreseeable to the breaching party.

Descriptions of contract-law vignettes.

| Motivating case(s) | The dispute | Ruling | Context not following economic prescription | Context following economic prescription | Concept from law and economics |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C1. Eastern S. S. Lines, Inc. v. United States | The U.S. Army rents a ship from a shipping company; at the end of the contract, the Army refuses to pay the full restoration costs that it agreed to pay in the contract. | The Army does not have to pay the full restoration costs. | Restoration costs are less than the value of the ship | Restoration costs are greater than the value of the ship | Efficient breach |

| C2. Hadley v. Baxendale | A bakery orders a replacement part and receives the part four days late; the bakery loses four days’ worth of profits, so it seeks full expectation damages equal to these lost profits. | The deliverer must pay partial damages that are significantly less than the full expectation damages | The bakery’s dependence on timely delivery was foreseeable to the deliverer | The bakery’s dependence on timely delivery was unforeseeable to the deliverer | Foreseeability |

6.1 Efficient breach – background

Economic efficiency requires flexibility regarding a promisor’s ultimate fulfillment of the terms of a contract. Contract breach is efficient when, likely due to changing circumstances, a promisor stands to lose more by fulfilling a contract than the promissee stands to gain. In such a case, efficiency requires the promisor to breach the contract and pay expectation damages that leave the promisee indifferent between contract fulfillment and breach with damages. This economic logic was employed in Eastern S. S. Lines, Inc. v. United States, a case in which the U.S. Army leased a ship from its owner during World War II and agreed to either return the ship to its original state or pay the ship owner the cost of restoration. When the ship was returned, however, the cost of restoration was assessed to be $4 million, while the ship’s value in its restored state was assessed to be only $2 million. The ship owner sought a $4 million payment from the Army, while the Army was only willing to pay $2 million. The court ruled that the changing value of the ship was an unforeseen circumstance and that, if the parties had considered the possibility, they would have agreed that the Army should have to pay the ship owner damages equal to the value of the ship. The case’s decision notes that it would have been wasteful to compel performance and force $4 million to be spent in order to create only $2 million in value. By allowing the Army to pay damages rather than restore the ship to its original condition, the court allowed the Army to breach the contract.

Since breach of contract requires a promisor to renege on an earlier agreement, it is possible that allowing efficient breach violates people’s moral intuitions of fairness. To test the relationship between efficient breach and perceived fairness, Vignette C1, included word-for-word in Supplementary Table S8 and summarized in the first row of Table 5, describes a scenario that resembles the fact pattern in Eastern S. S. Lines, Inc. v. United States. The U.S. Army rents a ship and, despite agreeing to pay restoration costs when the contract was formed, refuses to pay these costs when returning the ship. The court sides with the Army, allowing it to breach the contract. In the version that does not follow the economic prescription, breach is inefficient; restoration is cost-effective, as the ship is worth $5 million and restoration only costs $3 million. In the version that follows the economic prescription, breach is efficient; restoration is not cost-effective, as the ship is worth $1 million and restoration costs $3 million. In both versions, the Army reneges on an agreement, but in one instance it is clearly inefficient to do so. Since any difference in the perceived fairness of the decision to let the Army breach the contract can be attributed to the difference across the two versions, the results from this vignette can shed light on whether breach is considered to be fairer when it is also efficient.

6.2 Efficient breach – results

Across both versions of vignette C1, deontological attitudes toward promise-keeping and responsibility could shape respondents’ fairness perceptions of the ruling that allows the contract breach. Additionally, since the remedy involves the payment of monetary damages, attitudes toward income redistribution could also affect perceptions of fairness across both versions of C1. Any difference in responses across the two versions will point to the variation in cost-effectiveness of specific performance exerting an additional effect on perceptions of fairness.

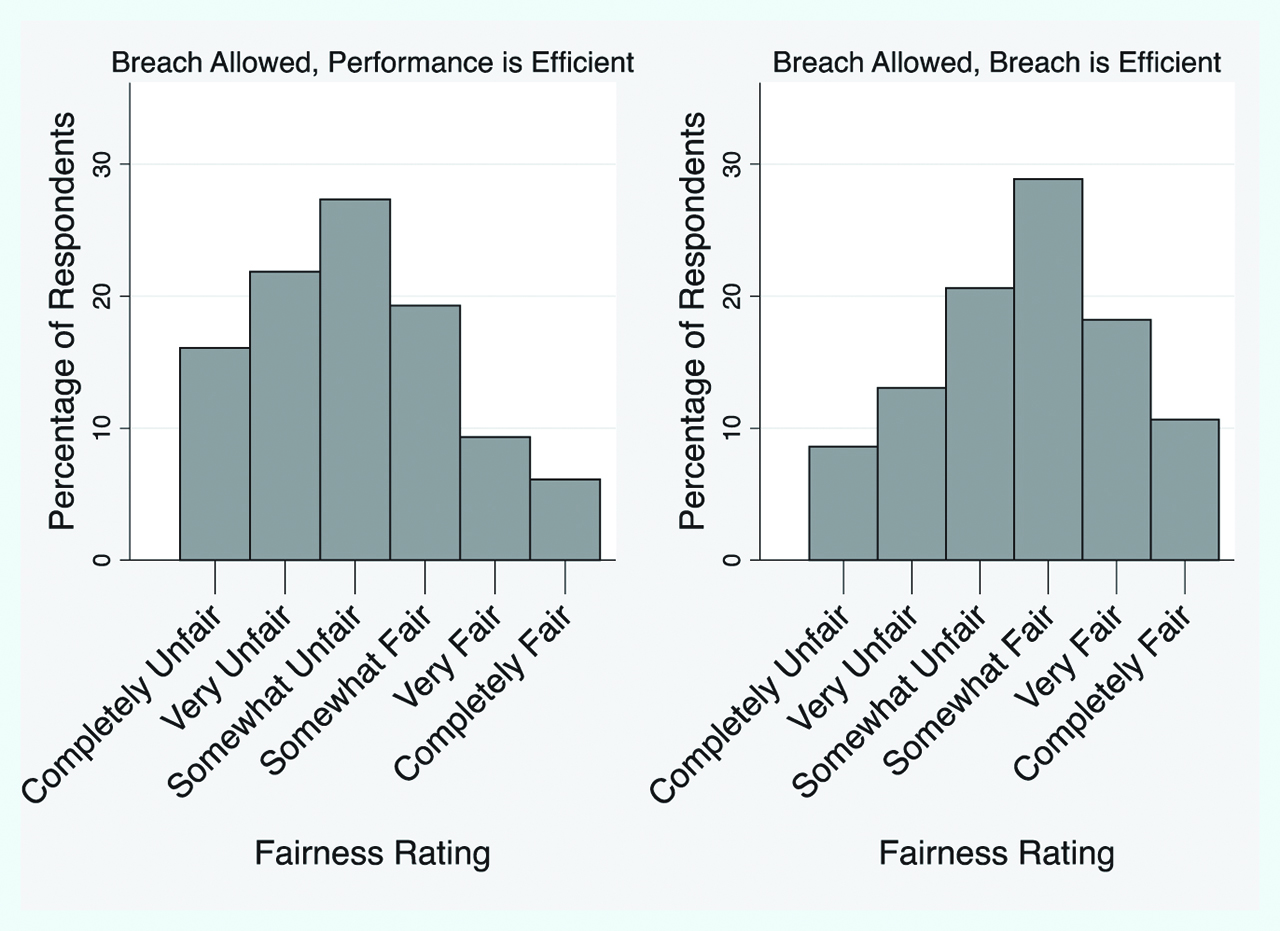

The results from vignette C1 are presented in the first row of Table 6. Figure 8 shows frequency distributions of responses across the two versions. The median and modal fairness ratings of the ruling that allowed the Army’s breach when performance was efficient was “somewhat unfair”; when breach was efficient, the same ruling received median and modal fairness ratings of “somewhat fair.” A Mann-Whitney shows that the difference between the distributions across inefficient and efficient breach is highly significant (U = 5.653; p < 0.0001), while the comparison of distributions from Figure 8 shows how the perceived fairness of allowing a breach of contract shifts depending on whether performance or breach was efficient.

Distributions of fairness assessments – efficient breach.

Contract-law vignettes (summary statistics and Mann-Whitney tests).

| Scenario | Ruling | Context not following economic prescription | Context following economic prescription | Mann-whitney U statistic(p-value) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | Mean fairness rating | Median fairness rating | n | Mean fairness rating | Median fairness rating | |||

| C1. The U.S. Army rents a ship from a shipping company; at the end of the contract, the Army refuses to pay the full restoration costs that it agreed to pay in the contract. | The Army does not have to pay the full restoration costs. | 311 | 3.02 | 3 | 291 | 3.67 | 4 | 5.653 (<0.0001) |

| C2. A bakery orders a replacement part and receives the part four days late; the bakery loses four days’ worth of profits, so it seeks full expectation damages equal to these lost profits. | The deliverer must pay partial damages that are significantly less than the full expectation damages | 322 | 3.97 | 4 | 280 | 4.14 | 4 | 1.98 (0.047) |

Fairness ratings are on a 1–6 scale (1=completely unfair; 2=very unfair; 3=somewhat unfair; 4=somewhat fair; 5=very fair; 6=completely fair). Mann-Whitney tests compare the distributions of fairness decisions in the inefficient and efficient contexts.

6.3 Foreseeability – background

The final common law domain to be examined is the doctrine of foreseeability, which provides a prescription for how to allocate risk within a contract. Every contract that is formed is subject to potential unforeseen consequences, and either the parties themselves (ex ante) or the courts (ex post) must allocate these risks. A risk is allocated efficiently when it is placed on the party that is better able to bear it. Hadley v. Baxendale is frequently cited as a case that set one especially important precedent for the efficient allocation of risk within a contract. The case involves a dispute following the late delivery of a milling business’s replacement part. Because the milling business (Hadley) could not function without the part, it suffered losses from the late delivery that equaled all lost profits from the two days that the delivery was late. As a result, the business sought damages equal to these lost profits. The court held that Baxendale (the party contracted to make the repair and delivery) did not have to pay these damages, however, since it was not possible for him, given the information provided by Hadley and given the common practices at the time, to foresee Hadley’s extreme dependence on the timely delivery. In coming to this conclusion, the court created incentives for parties in Hadley’s position to disclose risks that would otherwise not be recognized by the counterparty. With a duty to disclose being placed on the party with the ability to recognize the risk and bring it to light during contract formation, there is a greater likelihood that both parties appreciate the relevant risks and, as a result, a greater likelihood that agreed upon contracts are mutually beneficial.

Vignette C2, which is presented word-for-word in Supplementary Table S9 and summarized in the second row of Table 5, is based on the fact pattern in Hadley v. Baxendale. It tests whether the foreseeability doctrine aligns with perceptions of fairness. The vignette involves a bakery ordering a replacement part and losing five days’ worth of profits when the delivery is later than the agreed upon date. Like the ruling in Hadley v. Baxendale, the judge in the vignette rules that the deliverer owes some compensation for the late delivery, but an amount that is significantly less than the five days of lost profits sought by the bakery. In the version that does not follow the economic prescription, the scope of the harm caused by the late delivery was foreseeable to the deliverer; respondents are told (1) that the bakery told the deliverer about its dependence on the part and (2) that it was known, common practice for bakeries to not have a backup part on its premises. In the version that follows the economic prescription, in contrast, the damages were not foreseeable to the deliverer; the bakery did not tell the deliverer about its dependence on timely delivery and the deliverer could not be expected to recognize the risk because it was known, common practice to keep a backup on the premises. Full expectation damages that compensate the bakery for all of its losses represent the efficient remedy when the deliverer agrees to the contract with knowledge of what the consequences of late delivery would be. But damages this high are an inefficient remedy, which prohibit the formation of mutually beneficial contracts, when the deliverer does not understand the risks to which he is exposed when agreeing to the contract. A comparison of fairness ratings across the two versions sheds light on whether the ruling that follows from the foreseeability doctrine is regarded as being fairer.

6.4 Foreseeability – results

Across both versions of vignette C2, deontological attitudes toward promise-keeping and responsibility could shape respondents’ fairness perceptions of a ruling that fails to fully compensate for harm caused by a contract breach. Similar to vignette C1, attitudes toward income redistribution could also affect perceptions of fairness across both versions of vignette C2. Any difference in responses across the two versions will point to the variation in the foreseeability of severe harm exerting an additional effect on perceptions of fairness.

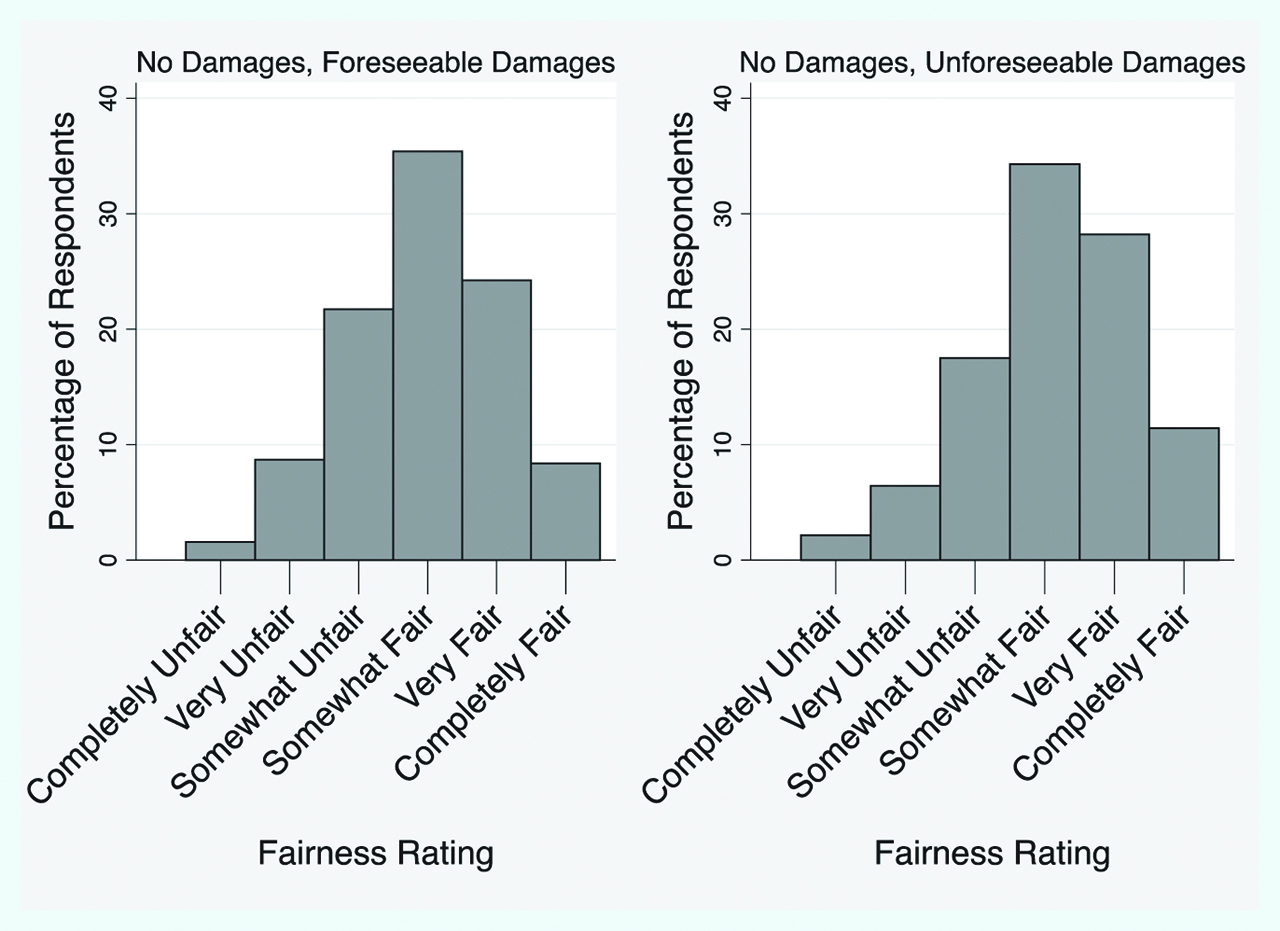

The results from vignette C2 are presented in the second row of Table 6. Figure 9 shows frequency distributions of responses across the two versions. While the median and modal fairness ratings are both “somewhat fair” across the two versions, a Mann-Whitney test does point to a statistically significant difference (U = 1.98, p = 0.047), with fairness ratings being significantly higher in version that follows the economic prescription. The frequency distributions from Figure 9 reveal an increased frequency of “very fair” and “completely fair” responses in the version that follows the economic prescription. Despite the evidence that points to a difference across the two versions of this vignette, the alignment between the economic prescription and intuitions of fairness with regards to the foreseeability doctrine is substantially weaker than the alignment seen in other areas of the common law.

Distributions of fairness assessments – foreseeability.

7 Discussion

Using vignettes based on the events underlying actual cases, and generating different versions of each vignette using the economic logic that informed these cases’ written decisions or shaped the law-and-economic analysis based on the case, I find that the economic logic that underlies the Coase theorem and the Hand rule, and generates prescriptions for the efficient use of strict product liability and efficient breach of contract, aligns with everyday intuitions of fairness. I also use this approach to show a positive, but weaker, relationship between fairness and the foreseeability doctrine, and to identify two other areas – fugitive property and punitive damages – where intuitions of fairness show no connection to economic prescriptions. These results point to an inherent morality in the economic logic that drives the core economic insights into property law, tort law and contract law, while simultaneously highlighting how moral intuitions can transcend economic reasoning when it comes to common-law legal rules in other domains.

The results are also largely consistent with the findings from experiments and vignette-based surveys that found a pervasive, but context-dependent, motive for efficiency in hypothetical scenarios and in distribution games; the underlying preferences for efficiency identified in these earlier studies seem to extend to many case-based assessments of prescriptions from law and economics. Consistent with the conclusion drawn by Konow (2003), however, when it comes to analyzing the perceived fairness of law-and-economic prescriptions, the results from the fugitive property and punitive damages vignettes highlight how efficiency can be a fragile motive when it conflicts with other principles.

These results have implications for how scholars and teachers of law and economics should expect their work to be received by those unfamiliar with their perspective. Rather than providing a provocative set of counterarguments to traditional legal scholarship that emphasizes justice and fairness, a focus on efficiency – at least with respect to core areas within property, tort and contract law – can be used to cast fairness and justice in a new light. Getting students and other scholars to appreciate the economic approach to analyzing the law does not require them to abandon homegrown intuitions of fairness. The challenge, instead, becomes one of bringing the concept of economic efficiency to life, clearly articulating why efficiency is, albeit not a perfect standard, one that is not morally empty.

While the areas where efficiency and intuitions align provide evidence that can be used in communicating how economic ideas inform the law, the areas of misalignment – punitive damages and fugitive property – generate implications as well. Friedman (1988) describes how situations where the common law, ethical intuitions and prescriptions for efficiency do not agree can be instructive for one of two reasons: they may point to either a problem with the common law or a problem with the economic analysis. The academic debate over the efficiency of punitive damages has unfolded along these lines, as one set of research argues that awards are excessive and/or incoherent (Kahneman et al., 1998; Viscusi, 1998, 2001; Sunstein et al., 2000), while another argues that economists are not properly valuing harm when assessing the efficiency of punitive damages (Sharkey, 2003; Klass, 2007). While the results presented here cannot speak to the overall coherence of punitive damage awards or the merits of the economic deterrence-based prescription, they do suggest that motives that transcend efficiency are driving a wedge between public perceptions and economic prescriptions with respect to the use of punitive damages. Consistent with the findings of Sunstein et al. (2000), when it comes to how people think about punitive damages, emotion-driven outrage at the actions of the defendant may be crowding out the quantitative assessment that is necessary for an analysis of economic efficiency. More specifically, the results from this vignette suggest that the outrage felt toward this negligent defendant, who knew about the defect and did not act on it, is invariant to the number of children harmed; instead, fairness perceptions seem fully determined by the fact that the company’s actions harmed any children.

The other area of misalignment points to a similar wedge between public perceptions and economic prescriptions concerning the assignment of property rights to fugitive property. The finding that the perceived fairness of assigning fugitive property is invariant to the length of time required for the initial investment suggests that emotion-driven preferences for rewarding the existence of effort are likely prioritized over quantitative assessments of how much effort is required to optimally encourage acquisition of fugitive property. This finding can shed light on recent research that points to the inefficiency of patent law, a salient contemporary manifestation of fugitive property.

There is a vague consensus view among law and economics scholars that fairness and the prescriptions from law and economics seem to overlap in some important ways. There is also a great deal of earlier work using surveys and experiments that points to a relationship between people’s motives for efficiency and their perceptions of fairness. While not providing all of the answers regarding the relationship between law-and-economic prescriptions and fairness, the results provided here serve a useful purpose in concretizing the overlap. It is hoped that teachers and scholars can use these results to make the point that the economic logic that underlies the Coase theorem, the Hand rule and efficient breach of contract, rather than simply arising out of a sterilized desire for efficiency, aligns with lay intuitions toward what constitutes a morally attractive resolution of disputes. Since the goal of this research was to span property law, tort law and contract law to see how perceptions of fairness align with some of the most prominent prescriptions from law and economics, future work can use similar methods while adopting a narrower approach. Specifically, each of the topics addressed here, as well as others, can be analyzed with additional vignettes, based on different cases, to more thoroughly catalog how perceptions of fairness align with prescriptions from law and economics.

Bibliography

Alesina, Alberto, and La Ferrara Eliana. 2005. “Preferences for Redistribution in the Land of Opportunities,” 89 Journal of Public Economics 897–931.10.3386/w8267Search in Google Scholar

Andreoni, James, and John Miller. 2002. “Giving according to GARP: An Experimental Test of the Consistency of Preferences for Altruism,” 70 Econometrica 737–753, https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-0262.00302.10.1111/1468-0262.00302Search in Google Scholar

Baker, C. Edwin. 1980. “Starting Points in Economic Analysis of Law,” 8 Hofstra Law Review 939–972.Search in Google Scholar

Barnes, David W., and Lynn A. Stout. 1992. Barnes and Stout’s Cases and Materials on Law and EconomicS, 1st ed. St. Paul, Minn: West Academic Publishing.Search in Google Scholar

Beranek, Benjamin, Robin Cubitt, and Gächter Simon. 2015. “Stated and Revealed Inequality Aversion in Three Subject Pools,” 1 Journal of the Economic Science Association 43–58, https://doi.org/10.1007/s40881-015-0007-1.10.1007/s40881-015-0007-1Search in Google Scholar

Bessen, James, Jennifer Ford, and Michael J. Meurer. 2011. “The Private and Social Costs of Patent Trolls,” 34 Regulation 26–35.10.2139/ssrn.1930272Search in Google Scholar

Bigoni, Maria, Stefania Bortolotti, Francesco Parisi, and Ariel Porat. 2017. “Unbundling Efficient Breach: An Experiment,” 14 Journal of Empirical Legal Studies 527–547, https://doi.org/10.1111/jels.12154.10.1111/jels.12154Search in Google Scholar

Boarini, Romina, and Le Clainche Christine. 2009. “Social Preferences for Public Intervention: An Empirical Investigation Based on French Data,” 38 The Journal of Socio-economics 115–128.10.1016/j.socec.2008.08.005Search in Google Scholar

Brown, John Prather. 1973. “Toward an Economic Theory of Liability,” 2 The Journal of Legal Studies 323–349.10.1086/467501Search in Google Scholar

Buhrmester, Michael, Tracy Kwang, and Samuel D. Gosling. 2011. “Amazon’s Mechanical Turk A New Source of Inexpensive, yet High-Quality, Data?,” 6 Perspectives on Psychological Science 3–5.10.1037/e527772014-223Search in Google Scholar