Abstract

Textiles are frequently used in bookbinding or for attaching pendent seals and thus they are an integral part of archival and library items. Any part of these items can be contaminated by various microorganisms. Consequently, it is often necessary to include disinfection procedures in the initial stages of the conservation process. Primarily, the agents employed in conservation must not harm the treated material. This work was concerned with monitoring the effect of selected disinfectant agents (ethylene oxide, Septonex®, glutaraldehyde, Bacillol® AF, butanol vapours, Acticide® MV, silver nanoparticles, Chiroseptol®) on the properties and long-term stability of natural textile fibres (cotton and silk). The disinfected textiles were subjected to three kinds of artificial ageing (dry heat, moist heat, and light) and their properties were determined by means of the total colour difference, thread tensile strength and the limiting viscosity number.

Zusammenfassung

Textilien wurden häufig als Überzugsmaterialien für Bucheinbände oder zur Anbringung von Siegeln verwendet und sind somit ein wesentlicher Bestandteil von Archiv- und Bibliotheksgut. Da Textilien durch verschiedene Mikroorganismen kontaminiert werden können, ist es oft notwendig, zu Beginn eines Restaurierungsprozesses Desinfektionsmittel einzubringen. Auf keinen Fall dürfen die dabei eingesetzten Substanzen das behandelte Material schädigen. In dieser Studie wurde die Wirkung ausgewählter Desinfektionsmittel (Ethylenoxid, Septonex®, Glutaraldehyd, Bacillol® AF, Butanoldämpfe, Acticide® MV, Silbernanopartikel, Chiroseptol®) auf die Eigenschaften und die Langzeitstabilität von textilen Naturfasern (Baumwolle und Seide) untersucht. Die desinfizierten Textilien wurden drei Arten der künstlichen Alterung (trockene Hitze, feuchte Hitze und Licht) unterzogen und ihre Eigenschaften anhand der Gesamtfarbdifferenz, der Fadenzugfestigkeit und der Grenzviskositätszahl bestimmt.

1 Introduction

Among library collections and archives, the focus of preservation and conservation treatment is on materials such as paper, leather, and parchment, while textiles frequently attached to those materials used to be rather neglected, although bound manuscripts with covers made of silk, velvet or brocade appear in libraries as early as the end of the 16th century. Cloth binding as a less expensive alternative to leather binding has been employed from the 1820ies. Utilization of cloth binding was intensified during the industrial revolution, while fine bookbinding employed velvet or damask (Vávrová and Součková 2017). In archives, textiles are mainly used for attaching pendent seals. These textile tags are typically made of silk, hemp, or linen and starting in the 19th century also from cotton (Ďurovič et al. 2002).

In some cases, the archival or library items can be contaminated by various kinds of microorganisms. Microorganisms can cause damage to collection items (Gutarowska et al. 2017) and can also be detrimental to the health of humans, especially of curators or conservators handling them on a regular basis, and thus it is often necessary to begin conservation work by disinfecting these objects. Disinfectants used in conservation of items of cultural heritage must fulfil a number of criteria, such as sufficient effectiveness, causing no damage to the treated material and the environment and minimum toxicity for human beings, to name the most important ones. While the effectiveness of disinfection agents as well as their toxicity for humans and the environment have been extensively studied, to date no in-depth study has been performed of their effect on the properties of the disinfected textiles.

Disinfection is a process that leads to a reduction in the number of viable microorganisms on the surface of the treated material. Effective disinfectants reduce the number of microorganisms by 99.99%. Disinfection agents can be divided into several groups according to their effectiveness. The most effective agents destroy microbial pathogens and mycobacteria, while others are effective against additional bacteria, viruses, and moulds. Disinfection agents are not effective against most bacterial spores and sometimes have limited effects on fungal spores (McDonnell 2017; Sridhar 2008). Disinfection methods can be classified according to the mechanism of their action as physical, chemical, and physical-chemical (McDonnell 2017; Sridhar 2008). The careful mechanical cleaning should follow the disinfection process to remove residues that are potentially allergenic. It is also necessary to pay attention to occupational safety and health when working with chemical agents.

1.1 Physical Disinfection

The most commonly employed disinfection methods are elevated temperature in dry or moist atmosphere, filtration, dehydration, deep-freezing, controlled atmosphere (N2, CO2), and irradiation (ionizing or nonionizing radiation). In the care of monuments, deep-freezing and a controlled atmosphere of nitrogen or carbon dioxide are the methods of choice (Nittérus 2000). Ionizing gamma radiation is used in the decontamination of collection items primarily for insect control because the doses required for disinfection would cause fundamental damage to the treated organic material (Bicchieri et al. 2016; Butterfield 1987; Drábková, Ďurovič, and Kučerová 2018; Henniges et al. 2012; Horáková and Martinek 1984).

1.1.1 Controlled Atmosphere

Reduction of the concentration of oxygen in the atmosphere using nitrogen or carbon dioxide is primarily effective for insect control. It is less effective for vegetative fungal forms and the controlled atmosphere is not sporicidal (Nittérus 2000; Pietrzak et al. 2016b; Sequeira, Cabrita, and Macedo 2012). This method does not affect most physical-chemical properties; however, several authors report decreased pH of material treated with carbon dioxide (Pietrzak et al. 2016b; Sequeira, Cabrita, and Macedo 2012).

1.1.2 Deep-freezing

The effectiveness of deep-freezing depends on the temperature and time, but the sporicidal effect is limited. Damage to microorganisms can be caused by the formation of ice crystals outside and inside their cells or a change in the pH of the cellular solutions, caused by a change in their concentrations by freezing of water. Effective disinfection and minimisation of the risk of damage to the treated material requires rapid freezing (ca 1 °C·s−1), during which small ice crystals are formed, which do not substantially endanger the treated material (Nittérus 2000; Sequeira, Cabrita, and Macedo 2012). From the viewpoint of minimising the risk of damage to frozen objects, the thawing method is also important, e.g., vacuum sublimation can be employed (Sequeira, Cabrita, and Macedo 2012).

1.2 Chemical Disinfection

Several chemical agents can be used for eradication of microorganisms, differing in the extent of their effectiveness, and they can be applied in various ways (Nittérus 2000; Sridhar 2008). In a conservation context, alcohols, aldehydes, ethylene oxide, quaternary ammonium salts, azoles, and sometimes also phenol derivatives are suggested. Newer research has also employed metals (McDonnell 2017; Pietrzak et al. 2016b), essential oils (McDonnell 2017; Pietrzak et al. 2016b; Sequeira, Cabrita, and Macedo 2012), titanium oxide (De Filpo et al. 2015; Pietrzak et al. 2016b; Sequeira, Cabrita, and Macedo 2012) and physical-chemical disinfection using plasma (Moreau, Orange, and Feuilloley 2008; Pietrzak et al. 2016b).

1.2.1 Alcohols

Alcohols are frequently used for disinfection in conservation work, either in the form of vapours (especially butan-1-ol) or as solutions (e.g., ethanol, propan-1-ol, propan-2-ol) (Bacílková 2006). Alcohols are effective against vegetative bacteria forms, viruses, and fungi, but their effectiveness against sporulating microorganisms is uncertain. Alcohols have an antimicrobial effect only at certain concentrations and thus aqueous solutions with a concentration of 50–90% are generally used (Bacílková 2006; McDonnel 2017). The main effect of alcohol consists in protein denaturation and coagulation; alcohols also affect lipids contained in the cellular membranes (Ali et al. 2001; Bacílková 2006). The effect of alcohols as disinfecting agent has been studied especially for paper documents, where attention has been drawn to the risk of washing out soluble substances, slight loss of surface gloss, increase in opacity and possibly slight deformation of the paper. However, these results were obtained for the application of alcohol by immersion and thus it can be anticipated that application in the form of vapours will not cause such a change in the properties (Bacílková 2006). In addition, another work (Pietrzak et al. 2016b) does not mention any decrease of mechanical properties of paper after the application of alcohol.

1.2.2 Phenol and its Derivatives

A number of phenol derivatives can be used for disinfection, and disinfection agents often contain a mixture of phenols. The effectiveness of an agent against various types of microorganisms depends on its composition; however, in general it can be stated that phenol and its derivatives are not sporicidal. Phenol and its derivatives can be designated as cell poisons damaging the plasmatic membranes (McDonnell 2017; Sequeira, Cabrita, and Macedo 2012). Amongst phenol derivatives, especially thymol and o-phenyl-phenol are used to conserve paper, mostly in the form of vapours and less often as an ethanolic solution (Nittérus 2000). The use of thymol can lead to a change in the colour of paper and also of parchment (Nittérus 2000; Sequeira, Cabrita, and Macedo 2012); o-phenyl-phenol can cause degradation, especially of cellulose (Sequeira, Cabrita, and Macedo 2012).

1.2.3 Aldehydes

Aldehydes form another group of chemical disinfection agents, where especially formaldehyde and glutaraldehyde are employed (McDonnell 2017; Nittérus 2000). Aldehydes are effective broad-spectrum disinfectants. The main mechanism of the effect of aldehydes on microorganisms is cross-linking of proteins (McDonnell 2017). Glutaraldehyde is mainly used as a 0.1–2.5% aqueous solution, while formaldehyde can be used in vapour phase or aqueous solutions (McDonnell 2017; Sequeira, Cabrita, and Macedo 2012). Disinfection with formaldehyde led to notable increased brittleness of paper, leather, parchment, or silk caused by cross-linking of the macromolecules (Sequeira, Cabrita, and Macedo 2012). Past conservation treatments included the commercially readily available agent Incidur® (manuf. Ecolab) containing glutaraldehyde and other active components (ethanol, propanol, and quaternary ammonium salts). At the present time, this agent is not available and can be replaced by Chiroseptol® (manuf. Recordati) with a similar composition (glyoxal, glutaraldehyde, quaternary ammonium salts, and ethoxylated alcohols).

1.2.4 Epoxides

Polypropylene oxide is rarely used for disinfection; standard methods employ ethylene oxide, which is an effective broad-spectrum substance with sporicidal effect. Ethylene oxide is an alkylation agent and thus its main mechanism of action is alkylation of proteins and nucleic acids (McDonnell 2017; Sequeira, Cabrita, and Macedo 2012). Ethylene oxide is employed in a mixture with other gases (CO2 or freons), and it is necessary to ensure sufficient ventilation to remove excess ethylene oxide from the treated material. The toxicity of ethylene oxide makes it necessary to maintain strict safety measures (Bacílková and Ďurovič 1991; Nittérus 2000; Sequeira, Cabrita, and Macedo 2012). Ethylene oxide has been used for sterilisation since the 1930s and thus its effect, especially on archival materials (paper, parchment, and leather), has been studied over a long time. Some studies mention increased susceptibility towards further attack by microorganisms following treatment with ethylene oxide and decreased physical-chemical properties of paper and natural textiles. However, some studies did not confirm deterioration of the studied properties (Bacílková and Ďurovič 1991; Sequeira, Cabrita, and Macedo 2012). Disinfection with ethylene oxide enables collective treatment of many objects.

1.2.5 Quaternary Ammonium Salts

Quaternary ammonium salts (QAS) are cationic surface active substances with an antimicrobial effect. These substances have primarily bactericidal effects, but lower effectiveness against fungi, and they do not have sporicidal effects (McDonnell 2017; Sequeira, Cabrita, and Macedo 2012). There is a number of QAS, e.g., dimethyldodecylbenzyl ammonium bromide or carbethopendecinium bromide (Septonex®). Their effectiveness differs, depending on their composition. The main mechanism of their effect is the dissolution of lipids in the cell wall and protein denaturation (Merianos 2001). QAS are employed in the form of aqueous or ethanolic solutions. One of the risks encountered with QAS is their retention in the treated materials, which can lead to worsening of their physical-chemical properties, e.g., of paper immediately after treatment and also in the long-term (Pietrzak et al. 2016b; Sequeira, Cabrita, and Macedo 2012).

1.2.6 Heterocyclic Compounds

Among heterocyclic compounds, the derivatives of imidazole and triazole are used for disinfection (Pietrzak et al. 2016b; Sequeira, Cabrita, and Macedo 2012). The effectiveness against microorganisms and the main mechanisms of this effect are greatly dependent on the type of derivative. These disinfectants can then be either mainly bactericidal or fungicidal. Consequently, a mixture of various derivatives is often used to optimise the effectiveness (Uhr et al. 2013). A mixture of isothiazole derivatives is mainly used in monument care, e.g., Kathon® (Hoffmann 1993).

1.2.7 Metals

The use of metals for disinfection has a long history; metals have been and still are used in various forms (metal vessels, salt solutions, aqueous dispersions, etc.). At the present time, mainly silver nanoparticles are employed. This metal is a broad-spectrum biocide, designated as a cellular poison (McDonnell 2017). Silver nanoparticles are presently under study and are not widely used for disinfection in conservation yet (Pietrzak et al. 2016a). Silver nanoparticles can be employed in "mist chambers" (Gutarowska et al. 2017) or by spraying or immersing in an aqueous dispersion. The biocidal effectiveness is dependent not only on the silver concentration in the dispersion, but also on the particle size. Although some studies (Gutarowska et al. 2017; Pietrzak et al. 2016c) state that the use of silver nanoparticles does not lead to changes in the physical-chemical and optical properties of paper and textiles, it is still necessary to take into consideration that, in a normal atmosphere, silver is covered with a layer of black silver sulphide, which could lead to a change in the colour of the treated object. Similarly to the effectiveness, the extent of colour change in the textile depends on both the concentration and on the particle size.

1.2.8 Essential Oils

Similar to silver nanoparticles, essential oils are not yet commonly used for disinfection of objects of cultural heritage; they are currently employed in the food and cosmetics industry. Essential oils have an inhibition effect, e.g., against viruses, bacteria, fungi, and insects. Essential oils contain a number of chemical compounds (hydrocarbons, aldehydes, ketones, phenols, phenolic ethers, alcohols, and esters) and thus the mechanisms of their effect is hard to determine. Their main effect relates to damage to the cellular walls and membranes (Bacílková and Paulusová 2012; McDonnell 2017). Essential oils are employed in the form of vapour or by direct contact. Some studies (Pietrzak et al. 2016c) do not describe any significant changes in the properties of paper after disinfection using essential oils (thyme essence). On the other hand, a study carried out by the National Archive in Prague (Bacílková and Paulusová 2012) pointed out that some of the main active substances of essential oils (e.g., eugenol) cause significant changes in the colour of treated paper. Other studies also point out the possibility of a detrimental effect on the mechanical properties of the treated lignocellulose material (Mikala 2015). Using linalool may cause material degradation, specifically in case of paper (decrease in the pH) (Rakotonirainy and Lavédrine 2005), photographs (change in the optical density) and leather (change in the shrinkage temperature) (Rakotonirainy et al. 2007).

1.3 Physical-chemical Disinfection

Physical-chemical methods combine the effect of both the described categories. An example could be disinfection using formaldehyde vapours at elevated temperature and pressure, where the disinfection is dependent not only on the formaldehyde (chemical), but also on the pressure and temperature (physical) (Sridhar 2008).

A further example of a physical-chemical method is the use of plasma (Sridhar 2008). The antimicrobial effect of this method and any negative effects on the treated material depend greatly on the conditions of the disinfection process (temperature, pressure, atmospheric composition, etc.). The main mechanism of the biocidal effect is then the reaction of the oxidation agent and reactive ions formed during ionisation of the gases (Scholtz et al. 2015). The results of research to date on any negative effect of the plasma on the materials of objects of cultural heritage are not entirely unambiguous and thus plasma is not yet used extensively in conservation.

2 Materials and Methods

2.1 Textiles

A wide range of textile fibres of plant and animal origin and occasionally also synthetic fibres can be encountered in textile conservation. Thus, this work was concerned with the effect of selected disinfectants on cellulosic and proteinaceous textile fibres. In the conservation of historical objects, partially degraded textiles are disinfected most of the time. Thus, prior to disinfection, the model samples were artificially aged by moist heat according to standard ISO 5630/3 (80 °C, 65% RH, 21 days) in a Memmert CTC 256 testing chamber.

Cotton fabric (unbleached, any low-molecular components were removed by boiling in a 0.5% sodium hydroxide solution), 134 g·m−2, plain weave, thread count in warp and weft 30 threads per 1 cm and silk fabric (natural mulberry silk Habotai), 43 g·m−2, plain weave, thread count in warp and weft 50 threads per 1 cm were used for the testing.

2.2 Disinfection

Representatives of various chemical methods were selected to study the effect of disinfectants on textiles. The choice of disinfectants took into consideration conservation practice and also the possibility of employing new methods that can be potentially useful for treating objects of cultural heritage. The doses of disinfectants were selected on the basis of literature research (ethylene oxide, butanol, Septonex®) or safety data sheets (Bacillol® AF, Chiroseptol®). Glutaraldehyde, silver nanoparticles and Acticid® MV were dosed on the basis of testing their effectiveness by the disc diffusion method at the National Archives in Prague. The textiles were not washed after disinfection. Table 1 gives a summary of the studied disinfectants.

Studied disinfectants including application procedure and manufacturer.

| Disinfection agent | Composition | Disinfection procedure | Manufacturer (supplier) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ethylene oxide | 10% ethylene oxide, 90% carbon dioxide | Temperature 28 °C, pressure 220 kPa, time 6 h, subsequent airing to remove residues 5 h in a chamber and 6 days in a ventilation tunnel | National Archives, Prague |

| Butanol vapours | butan-1-ol | 96% aqueous solution, above the solution in a hermetically sealed box, 48 h at laboratory temperature | Penta s.r.o. |

| Bacillol®AF | 45% propan-1-ol, 25% propan-2-ol and 4.7% ethanol | Concentrated solution, immersion 5 min at laboratory temperature, drying in the air | Bode Chemie Hamburg |

| Silver nanoparticles | Aqueous dispersion, min. particle size 6 nm, concentration 2000 mg/l | Concentrated dispersion, immersion 1 min at laboratory temperature, drying in the air | US Research Nanomaterials, Inc. |

| Septonex® | [1-(ethoxycarbonyl) pentadecyl] trimethylamonium bromide | 2% aqueous solution, immersion 1 min at laboratory temperature, drying in the air | Dr. Kulich Pharma, s.r.o |

| Glutaraldehyde | pentan-1,5-dial | 2% aqueous solution, immersion 5 min at laboratory temperature, drying in the air | Penta s.r.o. |

| Chiroseptol® | 6% glyoxal, 3.5% glutaraldehyde, 2.3% quaternary ammonium salt (benzyl-C12-16-alkyldimethyl chlorides), (≤6% ethoxylated alcohols C9-11) | 2% aqueous solution, immersion 15 min at laboratory temperature, drying in the air | Verkon s.r.o. |

| Acticide®MV | 5-chloro-2-methyl-1,2-thiazol-3(2H)-one, 2-methyl-1,2-thiazol-3(2H)-one in a ratio of 3:1; alkaline nitrates and chlorides | 1% aqueous solution, immersion 10 min at laboratory temperature, drying in the air | Biotech Aditiva s.r.o. |

2.3 Artificial Ageing

The disinfected and untreated samples were subjected to three types of artificial ageing to determine their long-term stability:

Dry heat according to ISO 5630/1 (105 °C, 21 days), Memmert UFE 500 (Germany)

Moist heat according to ISO 5630/3 (80 °C, 65% RH, 21 days), Memmert CTC 256 (Germany)

Light ageing according to standard ISO 5630/7 (imitation of daylight – fluorescent lamp PHILIPS TLD 18W/950, light intensity 12 klx, energy of the UV component 605 mW·m−2, 27 °C, 20% RH, 21 days), Artechnic (CZ) light chamber

Prior to further processing, the samples were air-conditioned for one week under laboratory conditions.

2.4 Determination of the Textile Properties

2.4.1 Colorimetry

The colour of the textiles was measured in the CIELAB colour space using a Mercury 2000 spectrophotometer (Datacolor, USA). The measurement was performed on a light-stable white support using templates, always at 10 identical places on the sample before and after disinfection and after artificial ageing. The overall colour change was calculated according to Equation (1)

where

The results were processed statistically, and the error was calculated as the corrected standard deviation, where twice this value is indicated in the graphs as error bars.

2.4.2 Viscometry

Measuring the limiting viscosity number [η] was used to monitor the degradation of cellulosic and proteinaceous macromolecules. The limiting viscosity number was determined using a capillary Ubbelohde viscometer.

2.4.2.1 Cotton

Cotton textiles were dissolved in iron(III) sodium tartrate complex (EWN) and the average degree of polymerization (DP) was calculated according to Equation (2), were 152 is the empirical constant from the standard CSN 80 0811. Two determinations were performed for each sample.

2.4.2.2 Silk

Silk textiles were dissolved in a saturated aqueous solution of lithium bromide and the limiting viscosity number was determined according to SNV 195 595. Silk fibroin is composed of sequences of different amino acids and therefore it is not possible to calculate DP for proteinaceous macromolecules. Two determinations were performed for each sample.

2.4.3 Mechanical Properties

The thread tensile strength to breakage was measured according to standard ISO 2062 with a Universal testing instrument LabTest 5.030-2 (Labortech, CR) with special jaws for holding threads. The thread fixed length was 10 cm, and the jaw speed was 50 mm·min−1. The resultant values of the thread strength expressed in N·tex−1 are the arithmetic mean of 20 weft thread measurements.

The results were processed statistically, and the error was calculated as the corrected standard deviation, where twice this value is indicated in the graphs as error bars.

3 Results and Discussion

Cotton and silk fibres exhibit similar results for each disinfectant tested in this study. Therefore, only representative bar charts are presented below.

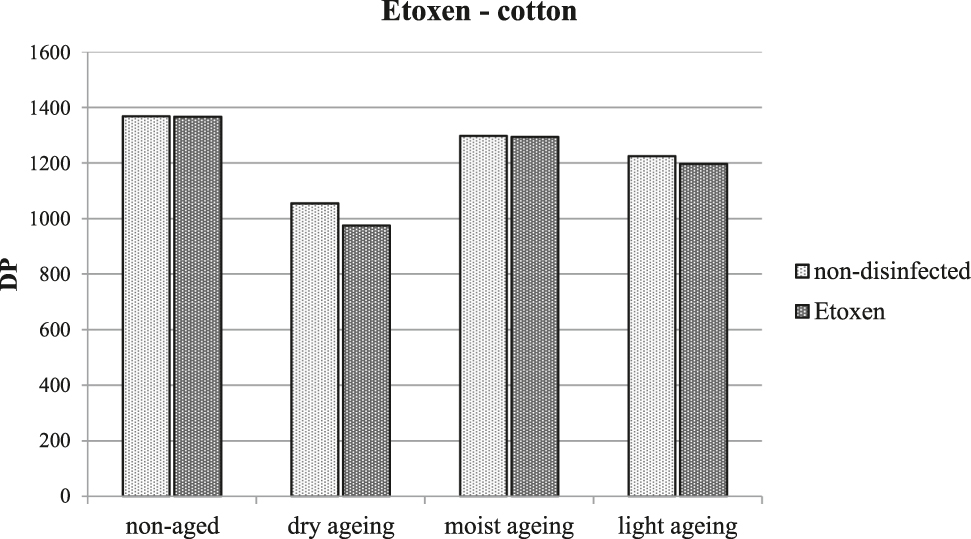

3.1 Ethylene Oxide

There were no significant changes in any of the monitored properties of cotton samples (colour change, DP, and thread tensile strength) after treatment with ethylene oxide or after artificial ageing. Figure 1 depicts the results of measuring DP which, as the most sensitive of all chosen tests, indicated changes in the chemical structure of the cellulose macromolecules typical for the initial phases of any degradation. The slight decrease in the average degree of polymerization of cellulose in samples after treatment with ethylene oxide and artificial ageing by dry heat is within the error of measurement.

The average degree of polymerization of cellulose following treatment with ethylene oxide and artificial ageing.

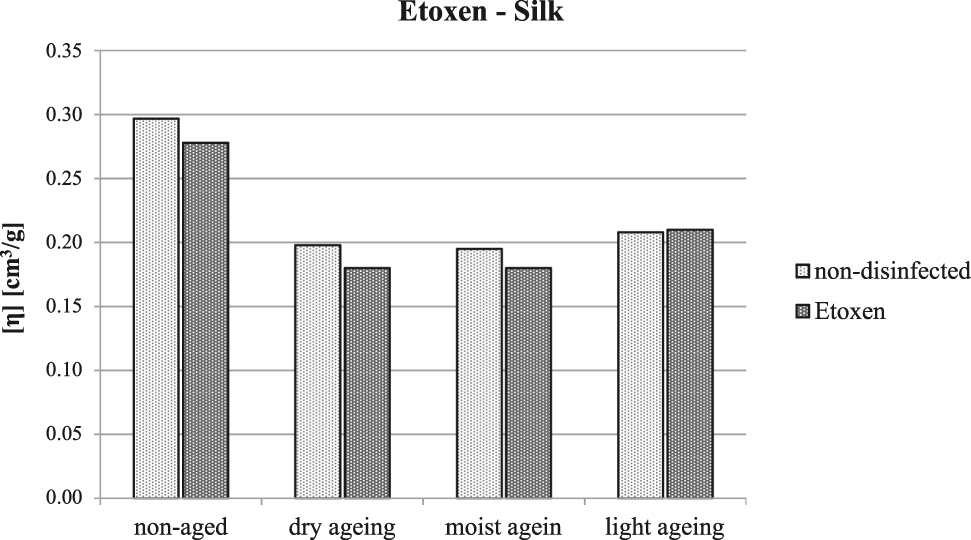

Even for silk, there were no significant changes in the monitored properties and the changes in the limiting viscosity number observable in Figure 2 lie within the error of measurement.

The limiting viscosity number of silk following treatment with ethylene oxide and artificial ageing.

Some works (Bacílková and Ďurovič 1991; Sequeira, Cabrita, and Macedo 2012) mention a deterioration in the physical-chemical properties of cellulosic and proteinaceous materials after treatment with ethylene oxide. However, the results of this study did not demonstrate substantial changes in the properties of any of the tested fibres following treatment with ethylene oxide and their long-term stability was also not affected by this treatment. Thus, ethylene oxide seems to be a suitable variant for mass disinfection of textile objects in collections.

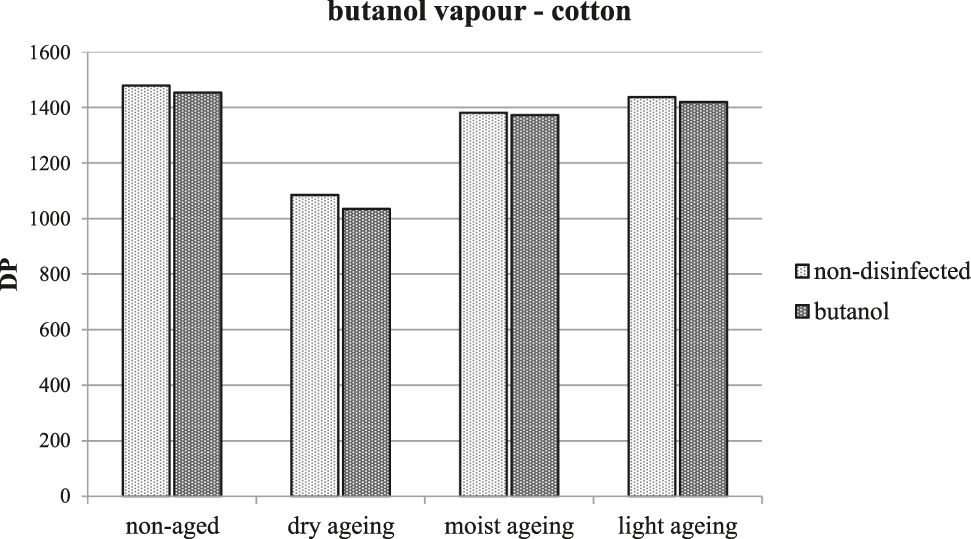

3.2 Butanol Vapours

No damage was found for samples treated with butanol vapours, nor was there any acceleration of the degradation process during artificial ageing. Figure 3 depicts the results of measuring DP which, as the most sensitive among the chosen tests, indicated changes in the chemical structure of the cellulose macromolecules typical for the initial phases of any degradation. There are minimal differences in the average degree of polymerization, and they lie within the error of measurement.

The average degree of polymerization of cellulose following treatment with butanol and artificial ageing.

Like cotton, no damage to the silk textile was observed immediately following disinfection and the resistance to artificial ageing was also not reduced. Butanol vapours are a suitable agent for disinfection of historical textiles.

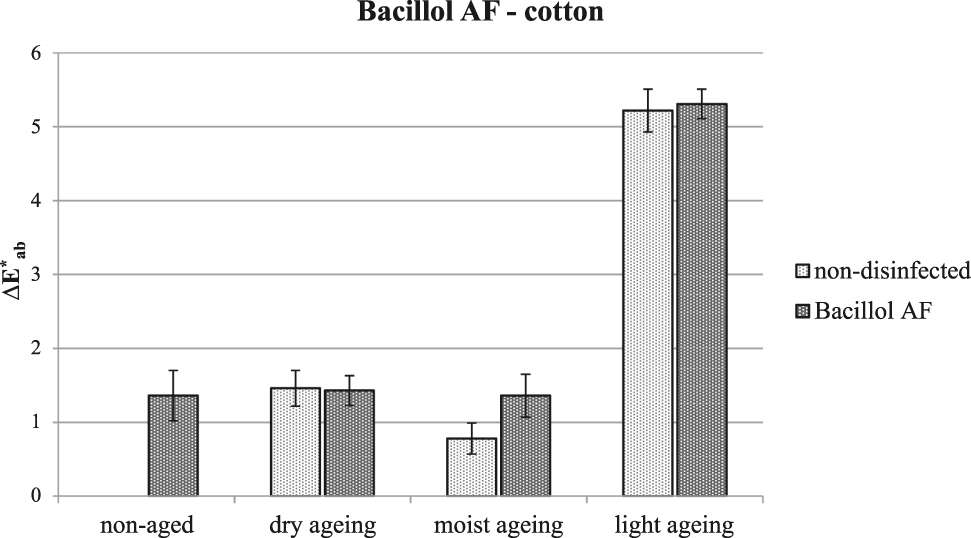

3.3 Bacillol® AF

No damage was found for samples of silk and cotton treated with Bacillol® AF, nor was there any acceleration of the degradation process during artificial ageing. Compared to the other tested disinfectants which were found to be suitable for disinfecting historical textiles, Bacillol® AF causes a greater overall change in the colour of cotton immediately after treatment (Figure 4). This phenomenon could be caused by removal of the non-cellulosic additives (e.g., wax) during immersion in the disinfectant agent. Boiling of cotton before the experiment causes minimal damage to the cotton but is not very efficient in removing non-cellulosic additives, that can then be extracted by alcohols.

Overall change in the colour of cotton following treatment with Bacillol® AF and artificial ageing. Note that higher ∆E∗ab after light ageing is due to light bleaching.

Bacillol® AF does not have a negative effect on the long-term stability of the tested natural textile fibres and is thus a suitable agent for disinfection of historical textiles.

3.4 Silver Nanoparticles

Problems were encountered with the quality of the studied aqueous silver nanoparticle dispersions.

A measurement performed using transmission electron microscopy (TEM) at the central laboratories of the University of Chemistry and Technology Prague revealed that the smallest particles had a diameter of approx. 6 nm compared to the value of 2 nm declared by the manufacturer, which could cause more substantial changes in the colour of textiles during treatment. The formation of aggregates was another problem.

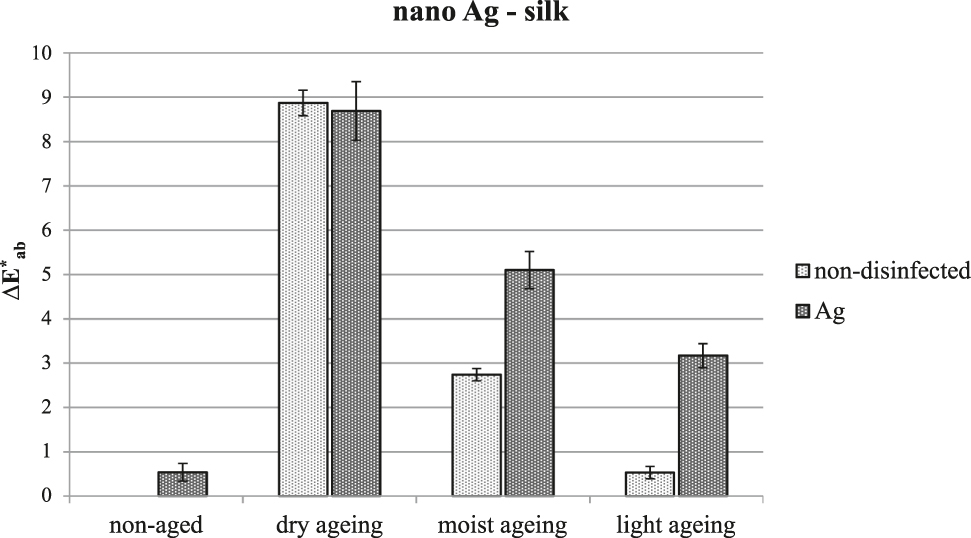

While the dispersion employed did not cause a change in the limiting viscosity number (or DP of the cellulose) or reduction in thread tensile strength, it affected the colour of the textiles (Figure 5). Typically, colour differences ΔE*ab between 1.5 and 2 are visible to the eye; however, there was not only an overall colour change, but marked stains were also visible.

Overall change in the colour of silk after treatment with Ag nanoparticles and artificial ageing.

The tested dispersion of silver nanoparticles applied by immersion is not a suitable disinfectant for the conservation of historical objects.

3.5 Septonex®

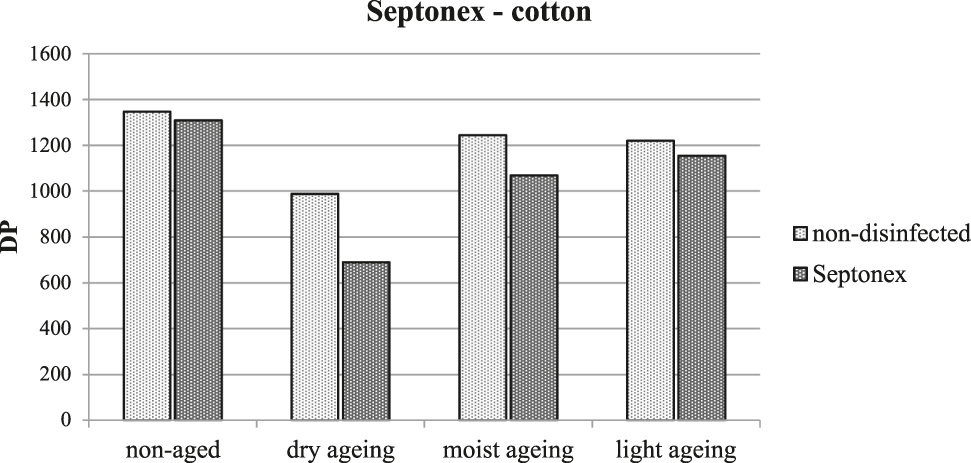

Cotton samples treated with Septonex® exhibited reduced resistance against artificial ageing for all the monitored properties. An important indicator of splitting of the cellulose macromolecule is the reduction of the average degree of polymerization for disinfected samples subjected to artificial ageing by moist heat and this effect was even greater for samples aged by dry heat (Figure 6).

The average degree of polymerization of cellulose following treatment with Septonex® and artificial ageing.

The results of the determination of DP of cellulose correspond to the results of measurement of the tensile strength of the threads, where treated samples subjected to artificial ageing by dry heat exhibited a reduction in their strength (from 0.12 N/tex to 0.10 N/tex). The reduction in DP after treatment and artificial ageing by moist heat is not sufficient to cause a measurable deterioration of the mechanical properties.

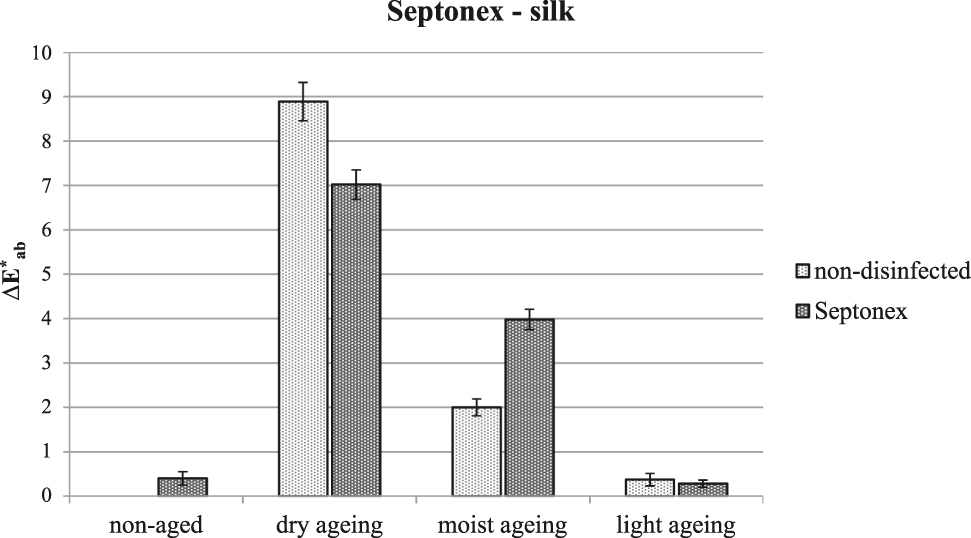

The reduced resistance to artificial ageing after treatment with Septonex® is not as apparent for silk as for cotton; nonetheless, there is an apparent reduction in the resistance to ageing from the viewpoint of the colour change (Figure 7).

Overall change in the colour of silk after treatment with Septonex® and artificial ageing.

One of the advantages of Septonex® is the possibility of preventive protection of objects for several years. While thorough washing of the agent from the textile precludes this preventative protection, it does substantially reduce the negative consequences for the textile material.

Septonex® causes certain changes in the properties of natural textile fibres and thus it can be used for disinfection of historical textiles only in justified cases, such as specific sensitivity of microorganisms.

3.6 Glutaraldehyde and Chiroseptol®

There were fundamental changes in the properties of samples treated with glutaraldehyde immediately following treatment and the resistance to artificial ageing was reduced. The colours of textiles changed substantially (∆E*ab 7–10) following treatment and artificial ageing. In addition, the macromolecules of silk and cotton became cross-linked so that the samples could not be dissolved for viscometric determination of the limiting viscosity number. The formation of a cross-linked structure is also documented by a reduction in the tensile strength of cotton threads after treatment with glutaraldehyde and artificial ageing (Figure 8).

The thread tensile strength of cotton after treatment with glutaraldehyde and artificial ageing.

There were also substantial changes in the physical-chemical properties of samples treated with Chiroseptol® that contains glutaraldehyde as an active component. The colour changes following treatment with Chiroseptol® were less than following treatment with glutaraldehyde, but were still significant (∆E*ab 4–8) and visible to the naked eye. In view of these findings, glutaraldehyde and Chiroseptol® are not suitable agents for disinfection of historical textiles.

3.7 Acticide® MV

Acticide® MV does not cause damage to cotton or silk samples immediately after treatment, nor was there any acceleration of the degradation processes during artificial ageing. Figure 9 depicts the results of measuring the limiting viscosity number that, best of all the monitored properties, indicates changes in the chemical structure of the fibroin macromolecules. There are no signs of degradation. Acticide® MV, a disinfectant agent based on isothiazoline, is suitable for disinfection of historical textiles.

The limiting viscosity number of silk following treatment with Acticide® MV and artificial ageing.

4 Conclusion

Our study of the effect of disinfection agents on natural textile fibres demonstrated that cotton and silk fibres exhibit similar results for all the tested disinfectants and thus it is not necessary to consider the type of textile fibres during disinfection. On the basis of the obtained results, the studied disinfectant agents can be divided into three groups. Of the agents tested, silver nanoparticles (in the form employed, they caused unacceptable colour changes), glutaraldehyde (causes changes in the colour and chemical structure) and Chiroseptol® (causes unacceptable colour changes) were found to be unsuitable agents for disinfection of historical textiles. Septonex®, which causes certain changes in the chemical structure of the fibres, can be used with reservations and only in justified cases (e.g., specific sensitivity of microorganisms). Agents based on alcohols (Bacillol® AF, butanol vapours) and Acticide® MV did not cause long-term changes in the properties of the textiles and are thus graded as suitable for disinfection of natural textiles. Ethylene oxide may be employed for mass treatment of many objects; it does not cause substantial changes in the properties of either cellulose or protein fibres. When selecting a disinfection agent, it is also necessary to take into consideration other factors relevant for conservation, e.g., the condition of the textiles, the colour fastness of the dyes employed, and the presence of other materials.

References

Ali, Y., M. J. Dolan, E. J. Fendler, and E. L. Larson. 2001. “Alcohols.” In Disinfection, Sterilization, and Preservation, 5th ed., edited by S. S. Block, 229–54. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. ISBN 0-683-30740-1.Suche in Google Scholar

Bacílková, B. 2006. “Study on the Effect of Butanol Vapours and Other Alcohols on Fungi.” Restaurator 27: 186–99, https://doi.org/10.1515/rest.2006.186.Suche in Google Scholar

Bacílková, B., and M. Ďurovič. 1991. “Dezinfekce archivních a knihovních sbírek ethylenoxidem.” Sborník VŠCHT Praha 20: 135–45. ISSN 013-908X.Suche in Google Scholar

Bacílková, B., and H. Paulusová. 2012. Vliv silic a jejich hlavních účinných složek na mikroorganismy a na archivní materiál. [online]. Prague: Národní archiv. [cit. 17. 1. 2019], http://www.nacr.cz/wp-content/uploads/2015/11/silice.pdf.Suche in Google Scholar

Bicchieri, M., M. Monti, G. Piantanida, and A. Sodo. 2016. “Effects of Gamma Irradiation on Deteriorated Paper.” Radiation Physics and Chemistry 125: 21–6. 1, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.radphyschem.2016.03.005.Suche in Google Scholar

Butterfield, F. 1987. “The Potential Long-term Effects of Gamma Irradiation on Paper.” Studies in Conservation 32: 181–91, https://doi.org/10.2307/1506182.Suche in Google Scholar

Drábková, K., M. Ďurovič, and I. Kučerová. 2018. “Influence of Gamma Radiation on Properties of Paper and Textile Fibres during Disinfection.” Radiation Physics and Chemistry 152: 75–80, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.radphyschem.2018.07.023.Suche in Google Scholar

Ďurovič, M., J. Bacílek, J. Dernovšková, j. Hanus, A. Krejčí, Z. Kukánková, K. Opatová, H. Paulusová, R. Straka, J. Šejharová, M. Širový, J. Tomšů, and J. Vnouček. 2002. Restaurování a konzervování archiválií a knih. Litomyšl: Paseka. ISBN 80-7185-383-6.Suche in Google Scholar

De Filpo, G., A. M. Palermo, R. Munno, L. Molinaro, P. Formoso, and F. P. Nicoletta. 2015. “Gellan Gum/titanum Dioxide Nanoparticle Hybrid Hydrogels for the Cleaning and Disinfection of Parchment.” International Biodeterioration & Biodegradation 103: 51–8, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ibiod.2015.04.012.Suche in Google Scholar

Gutarowska, B., K. Pietrzak, W. Machnowski, and J. M. Milczarek. 2017. “Historical Textiles – a Review of Microbial Deterioration Analysis and Disinfection Methods.” Textile Research Journal 87 (19): 2388–406, https://doi.org/10.1177/0040517516669076.Suche in Google Scholar

Henniges, U., S. Okubayashi, T. Rosenau, and A. Potthast. 2012. “Irradiation of Cellulosic Pulps: Understanding its Impact on Cellulose Oxidation.” Biomacromolecules 13: 4171–8, https://doi.org/10.1021/bm3014457.Suche in Google Scholar

Hoffmann, P. 1993. “Sucrose for Stabilizing Waterlogged Wood.” In Proceedings of the 5th ICOM Group on Wet Organic Archaeological Materials Conference. Deutsches Schiffahrtsmuseum: Portland/Main. ISBN 3-927857-54-8.Suche in Google Scholar

Horáková, H., and F. Martinek. 1984. “Disinfection of Archive Documents by Ionizing Radiation.” Restaurator 6 (3-4): 205–16, https://doi.org/10.1515/rest.1984.6.3-4.205.Suche in Google Scholar

McDonnell, G. E. 2017. Antisepsis, Disinfection, and Sterilization: Types, Action, and Resistance. Washington, DC: ASM Press. ISBN 978-1-5231-1259-3, https://doi.org/10.1128/9781555819682.Suche in Google Scholar

Merianos, J. J. 2001. “Surface-active Agents.” In Disinfection, Sterilization, and Preservation, 5th ed., edited by S. S. Block, 238–320. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. ISBN 0-683-30740-1.Suche in Google Scholar

Mikala, O. 2015. “The Influence of Selected Components of Essential Oils on the Mechanical and Optical Properties of the Lignocellulose Materials.” Acta facultatis xylologiae Zvolen 57(2), 81−8.Suche in Google Scholar

Moreau, M., N. Orange, and M. G. J. Feuilloley. 2008. “Non-thermal Plasma Technologies: New Tools for Bio-decontamination.” Biotechnology Advances 26: 610–17, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biotechadv.2008.08.001.Suche in Google Scholar

Nittérus, M. 2000. “Fungi in Archives and Libraries.” Restaurator 21 (1): 25–40, https://doi.org/10.1515/rest.2000.25.Suche in Google Scholar

Pietrzak, K., B. Gutarowska, W. Machnowski, and U. Mikolajczyk. 2016a. “Antimicrobial Properties of Silver Nanoparticles Misting on Cotton Fabrics.” Textile Research Journal 86 (8): 812–22, https://doi.org/10.1177/0040517515596933.Suche in Google Scholar

Pietrzak, K., A. Koziróg, M. Bučková, A. Puškárová, and V. Scholtz. 2016b. “Disinfection Methods for Paper.” In A Modern Approach to Biodeterioration Assessment and the Disinfection of Historical Book Collections, 56–80. Lodz: Lodz University of Technology. ISBN 978-83-63929-01-5.Suche in Google Scholar

Pietrzak, K., A. Otlewska, K. Dybka, D. Danielewitz, D. Pangallo, K. Demnerová, M. Ďurovič, L. Kraková, V. Scholtz, M. Bučková, A. Puškárová, I. Kučerová, M. Škrdlantová, K. Drábková, B. Surma-Ślusarska, and B. Gutarowska. 2016c. “A Modern Approach to Biodeterioration Assessment and Disinfection of Historical Book.” In A Modern Approach to Biodeterioration Assessment and the Disinfection of Historical Book Collections, 81–125. Lodz: Lodz University of Technology. ISBN 978-83-63929-01-5.Suche in Google Scholar

Rakotonirainy, M. S., F. Juchauld, M. Gillet, M. Otman-Choulak, and B. Lavédrine. 2007. “The Effect of Linalool Vapour on Silver-gelatine Photographs and Bookbinding Leathers.” Restaurator 28 (2): 95–111, https://doi.org/10.1515/rest.2007.95.Suche in Google Scholar

Rakotonirainy, M. S., and B. Lavédrine. 2005. “Screening for Antifungal Activity of Essential Oils and Related Compounds to Control the Biocontamination in Libraries and Archives Storage Areas.” International Biodeterioration & Biodegradation 55: 141–7, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ibiod.2004.10.002.Suche in Google Scholar

Sequeira, S., E. J. Cabrita, and M. F. Macedo. 2012. “Antifungal on Paper: An Overview.” International Biodeterioration & Biodegradation 74: 67–86, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ibiod.2012.07.011.Suche in Google Scholar

Scholtz, V., J. Pazlarova, H. Souskova, J. Khun, and J. Julak. 2015. “Nonthermal Plasma – A Tool for Decontamination and Disinfection.” Biotechnology Advances 33: 1108–19, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biotechadv.2015.01.002.Suche in Google Scholar

Sridhar Rao, P. N. 2008. Sterilization and Disinfection. [online]. [cit. 17. 1. 2019], https://www.microrao.com/micronotes/sterilization.pdf.Suche in Google Scholar

Uhr, H., B. Mielke, O. Exner, K. R. Payne, and E. Hill. 2013. “Biocides.” In Ullmann’s Encyclopedia of industrial Chemistry. Weinheim: Wiley VCH. ISBN 9783527303854.10.1002/14356007.a16_563.pub2Suche in Google Scholar

Vávrová, P., and M. Součková, eds. 2017. Konzervace a restaurování novodobých knihovních ondů. Praha: Národní knihovna České republiky. ISBN 978-80-7050-696-7.Suche in Google Scholar

© 2021 Klára Drábková et al., published by De Gruyter, Berlin/Boston

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.