Abstract

This paper deals with the issue of additive technologies using glass. At the beginning, our research dealt with a review of the current state and specification of potentially interesting methods and solutions. At present, this technology is being actively developed and studied in glass research. However, as the project started at the Department of Glass Producing Machines and Robotics, the following text will be more focused on the existing 3D printing machinery and basic technological approaches. Although “additive manufacturing” in the sense of adding materials has been used in glass manufacturing since the beginning of the production of glass by humans, the term additive manufacturing nowadays refers to 3D printing. Currently, there are several approaches to 3D printing of glass that have various outstanding advantages, but also several serious limitations. The resulting products very often have a high degree of shrinkage and rounding (after sintering), and specific shape structures (after the application in layers), but they generally have a large number of defects (especially bubbles or crystallization issues). Some technologies do not lead to the production of transparent glass and, therefore, its optical properties are significantly restricted. So far, the additive manufacturing of glass do not produce goods that are price competitive to goods produced by conventional glass-making technologies. If 3D glass printing is to be successful as an industrial and/or highly aesthetically valuable method, then it must bring new and otherwise unachievable features and properties, as with 3D printing of plastic, metal, or ceramics. Nowadays, these technologies promise to be such a tool and are beginning to attract more and more interest.

Introduction

Additive manufacturing (AM) technologies are often associated with modern technologies and commonly referred to as technologies of the future. Nevertheless, the glass-making technology using the additive principle is one of the oldest: Gathering and winding of molten glass (e.g., used for core forming) were already performed in Egypt around 1500 BC. In addition, hot joining of glass parts during the shaping of the product (e.g., prunts) is typical not only for manual production [1].

Nevertheless, AM is considered to be a new technique due to the materials used (such as polymers) and especially the automation technology used in production. In particular, 3D printing is a very interesting technology allowing objects to be flexibly produced, which could not be produced by another technology, or it would be very expensive to do so. 3D printing has been in commercial use since the late 1980s and since then, it has greatly improved and expanded [2]. Many technologies have emerged that have various specific advantages and disadvantages. The following principles of 3D printing are divided according to the standard ISO/ASTM 52900:2015(en) additive manufacturing—general principles—terminology [3]:

Material extrusion,

Photopolymerization,

Powder bed fusion,

Material jetting,

Binder jetting,

Sheet lamination,

Directed energy deposition.

At the same time, the portfolio of processed materials used for printing is also expanding. Since the exclusive use of polymers (in varied compositions), the range of raw materials used has expanded to include both metallic and ceramic materials, as well as other non-traditional materials such as food (cakes, pasta, biscuits), biological materials (e.g., bone replacement, teeth printing) or even whole houses. Interestingly, glass materials are still missing from widespread implementation in AM; however, the possibilities of 3D printing of glass are fast evolving [4]. The issue has been studied in more detail over the last decade, and the latest review [4] presents the current situation. However, it does not follow the classification of the above-mentioned standard ISO/ASTM 52900:2015 [3].

We conducted this study at the beginning of our research of 3D glass printing. Based on this, it is possible to conclude that 3D printing of glass materials is a quite novel issue of high scientific potential, and is promising for a wide range of applications, typically in the glass industry, biomedicine (e.g., replacement of certain parts of the human body), (micro)optics (gradient index lenses), jewelry, and art. In industrial glass and especially artistic production, 3D printing may also be used for printing molds or positives for the subsequent production of molds using classic technologies [5]. Of course, physical and chemical processes are very important in the preparation of raw materials for the 3D printer, during the printing itself and subsequent processing, and also during the lifespan of the product. However, this text deals with the possibilities of 3D printing of glass in general and is limited to the main interesting technologies, existing machinery and engineering approaches according to our research scope.

Dividing the technologies according to the requirements of the subsequent process

In general, the published technologies of 3D printing of glass may be divided into the following approaches:

Indirect acquisition (a “green body” is obtained from the 3D printing and subsequently, the object needs to be thermally exposed to acquire the object in a glass state), and

Direct acquisition (the object is produced completely in a glass state after the 3D printing process).

Both of the above-described basic processes may have their advantages and disadvantages. Indirect acquisition most often uses a mixture of entrained particles and polymers. These are usually then printed at normal temperatures using existing 3D printing technologies. This is the main advantage, i.e., existing 3D printing technologies are used, the approach is generally cheaper, and it is possible to focus on the problems of the mixture and subsequent heat treatment-sintering. The mixture itself, its preparation, and subsequent heat treatment complicate the technology and lead to long production times. However, a more significant problem is the high degree of shrinkage and rounding, which is solved by optimization of the mixture and by a reliable numerical simulation [4, 6, 7].

In terms of its characteristics, direct acquisition is the opposite of indirect acquisition. It is usually printed directly from molten glass, which reduces subsequent shrinkage. The time of product preparation is also shortened. In most cases, the printing material is cheaper. The disadvantages are the need to print at elevated temperatures and the high cost of the equipment (especially due to the necessary development and the production at elevated temperatures). Certain technologies may be found with a characteristic “layered” structure, which is given by the technology of 3D printing [6, 7].

So far, all the technologies we have studied (regardless of whether they are direct or indirect production) have led to problems with shape defects and especially with gaseous inclusions (bubbles) [4, 8], [9], [10], [11], [12], [13]. Solutions to these problems are at various stages of research.

Material extrusion

There are several different AM technologies in this case. The best-known material extrusion technology is fused deposition modeling (FDM), and essentially the same Fused filament fabrication (FFF) [2],. The printing material is applied onto the printing substrate in layers. Each time a layer of printing is finished, the print head (or build plate) moves one layer up, and the next layer starts printing. The undeniable advantage is the low purchase price of the 3D printer and the relatively low cost of the model building material. The range of materials used is also wide and growing. The disadvantages are a long printing time, considerable variance in printing accuracy, the choice of the printing orientation of the model, the method and construction of supports, and others [2].

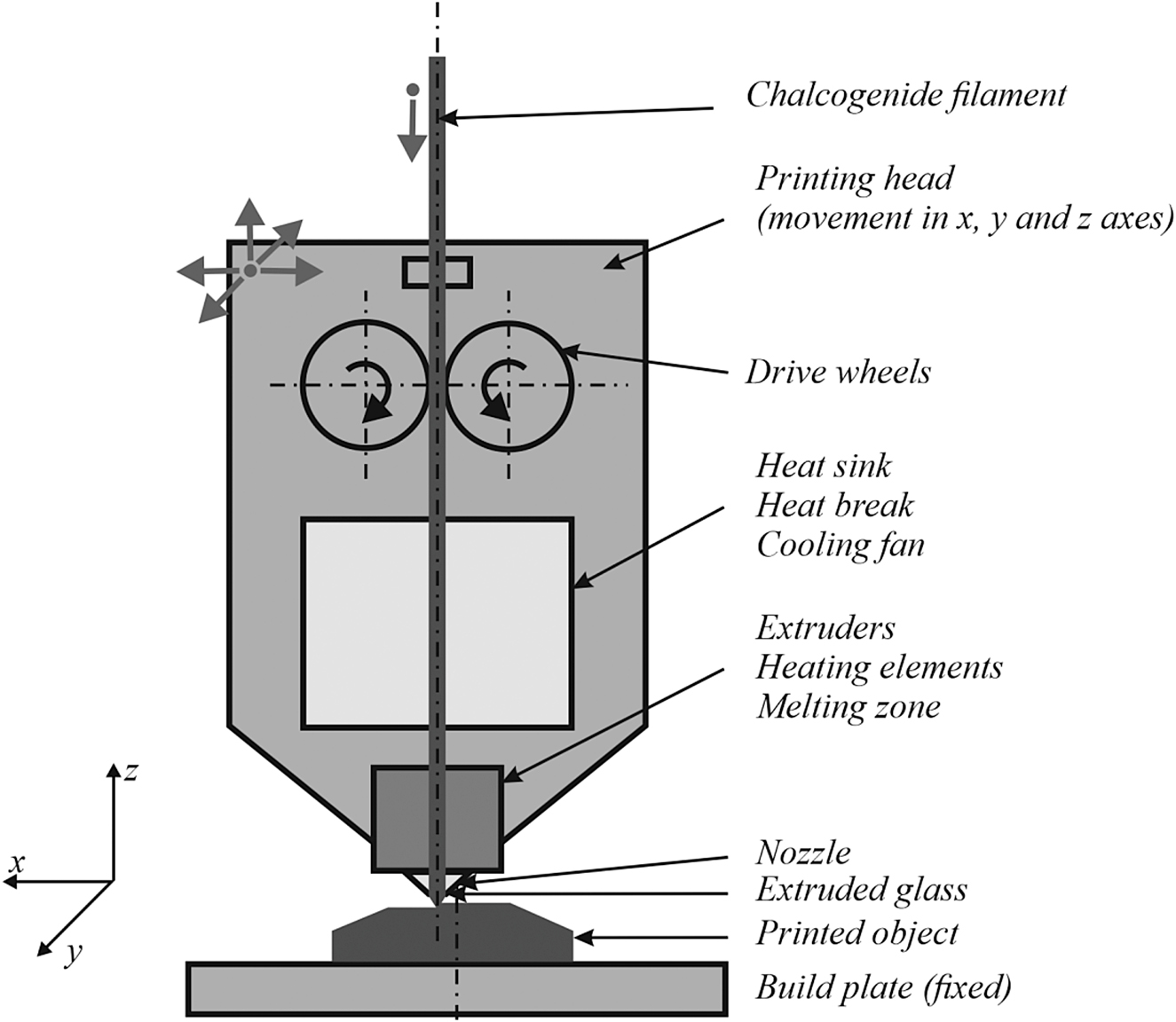

This technology is based on printing from a filament of chalcogenide glass (As40S60) [14], with a low melting point (T g = 188 °C), Fig. 1. The filament is introduced between the heating elements and the molten material emerges from the nozzle and is applied to the base. The application is performed in layers. In this case, it moves in the x, y, z axes of the head of the device with the filament. The results of printing on the surface and inside the body have a “caterpillar” structure, which corresponds to the gradual application of the molten material [14].

Diagram of the FDM principle for chalcogenide glass.

Even though it is not the first use of 3D glass printing, the most well-known technology is Glass 3D Printing (G3DP) introduced in 2015 by the Massachusetts Institute of Technology [9]. The current technology uses silica glass melted outside the device and consists of three kilns (chambers) electrically heated using heating coils, Fig. 2. The first chamber (the melter kiln) maintains the glass at a temperature corresponding to a suitable viscosity for printing. This temperature is around 1100 °C, and the chamber is large enough to produce a single product. The molten glass is transferred to the melter kiln from a pot furnace, where it is necessary to reach a homogeneous temperature in the entire volume, so the glass is tempered for a certain period of time. The glass then flows by its own weight through a second chamber (the nozzle kiln). The nozzle material is made from alumina, zirconia, and silica, and according to other information sources [9] the nozzle is heated slightly above 1000 °C. Molten glass is extruded into the third chamber (the annealing kiln), which is tempered to a temperature of about 480 °C [9].

![Fig. 2:

Diagram of the G3DP principle according to ref. [9].](/document/doi/10.1515/pac-2021-0707/asset/graphic/j_pac-2021-0707_fig_002.jpg)

Diagram of the G3DP principle according to ref. [9].

The molten glass flows out at a suitable viscosity onto a build plate, which ensures movement in the z-axis (up–down), the movement being derived from a stepping motor. The movement in the other two axes (x and y) is ensured by the movement of the upper (first) chamber, i.e., the chamber with the supply of glass moves from right to left, and forwards and backwards by means of stepping motors. The enamel forms a “caterpillar”, whose viscosity ensures that it does not collapse further. Gradually, the object is created due to the movement of the build plate with the chamber driven by the stepping motors, which are controlled by a computer. In order to achieve a viscosity suitable for 3D printing and at the same time for proper heat dissipation from the annealing kiln so that the object does not collapse, it is necessary to properly set and stabilize the temperatures in the individual parts of the device. Due to the fact that the glass in the presented video [15] flows freely, the production is also time consuming [9, 15, 16].

The project from 2015 focused on larger architectural objects made of glass, and in 2017 the results of the GLASS II [16] device were presented. The device also changed its appearance and only the build plate (in all axes – x, y, z) is now movable, on which the “caterpillar” flowing out of the nozzle is applied (the technology is called G3DP2). This is much better for use in industrial production, as the nozzle may be connected to a feeder of a continuous melting unit. The outflow is described as being spontaneous, so again it is a relatively lengthy process.

The results of the 3D printing performed by this technology are, at first glance, different from other technologies of glass production. A typical characteristic is their caterpillar appearance, which is given by the application technology. As for the glass compositions, the above-mentioned examples illustrate that the FDM technique may provide solutions not only for a very simple, yet demanding, glass composition such as silica glass (a narrow working temperature range and a relatively high softening point) [9], but also for complex optical glass compositions, such as chalcogenide glass [14] or recently prepared highly dense transparent Eu3+ doped phosphate glass [17]. The question is whether this principle (appropriately modified) may be applied in the future for the preparation of design products, and possibly also for the flexible mass production of classic glass products.

The FDM technology uses the principle of direct acquisition. However, material extrusion may also be used for indirect acquisition. This is a 3D printing technology made of extruded material composed of glass powder (filler) and a binder, most often in the form of a cured (e.g., UV radiation) polymer or an air-drying substance. This principle is often used in 3D ceramic printing. These techniques are associated with extrusion printing, or robocasting (using a robot to apply a highly viscous paste), similarly to liquid deposition modeling and also direct ink writing (DIW) [10, 18], [19], [20], [21].

The optimization of the printing process of indirect acquisition by material extrusion (obtaining a “green body”) is shown in the text [18], Fig. 3. Subsequent thermal processing consists of a long drying step at a low temperature (100 °C), which initially removes the ink solvent (without the long drying step, cracks may form). Then a short step is applied at a medium temperature (600 °C, obtaining the “brown body”), which is used to remove any residual organics (without the organic burnout, discoloration and crack formation during sintering may occur). Lastly, a rapid step at high sintering temperatures (1500 °C) is used to obtain transparency.

![Fig. 3:

Diagram of the DIW principle for glass according to [18].](/document/doi/10.1515/pac-2021-0707/asset/graphic/j_pac-2021-0707_fig_003.jpg)

Diagram of the DIW principle for glass according to [18].

The resulting products show two aspects of indirect printing: a high shrinkage rate (up to 47 % of the original width) and a long preparation time (113 h). Of course, as for most SiO2-based glass materials, high product preparation temperatures (1500 °C) and a short heating and cooling period to prevent the amorphous structure from transitioning to the crystalline phase is required. Nevertheless, the process is optimized, and, promisingly, the conditions for the preparation and production of a transparent glass products are specified [18]. The DIW technique has recently been substantially examined as a versatile method, where sol–gel derived colloidal suspensions with tunable rheology and refractive indices may be advantageously used. Recently, optical quality glass such as silica, silica–titania or silica–germanium oxide glass systems with a tuned gradient index have been studied [10, 19], [20], [21], [22].

Photopolymerization

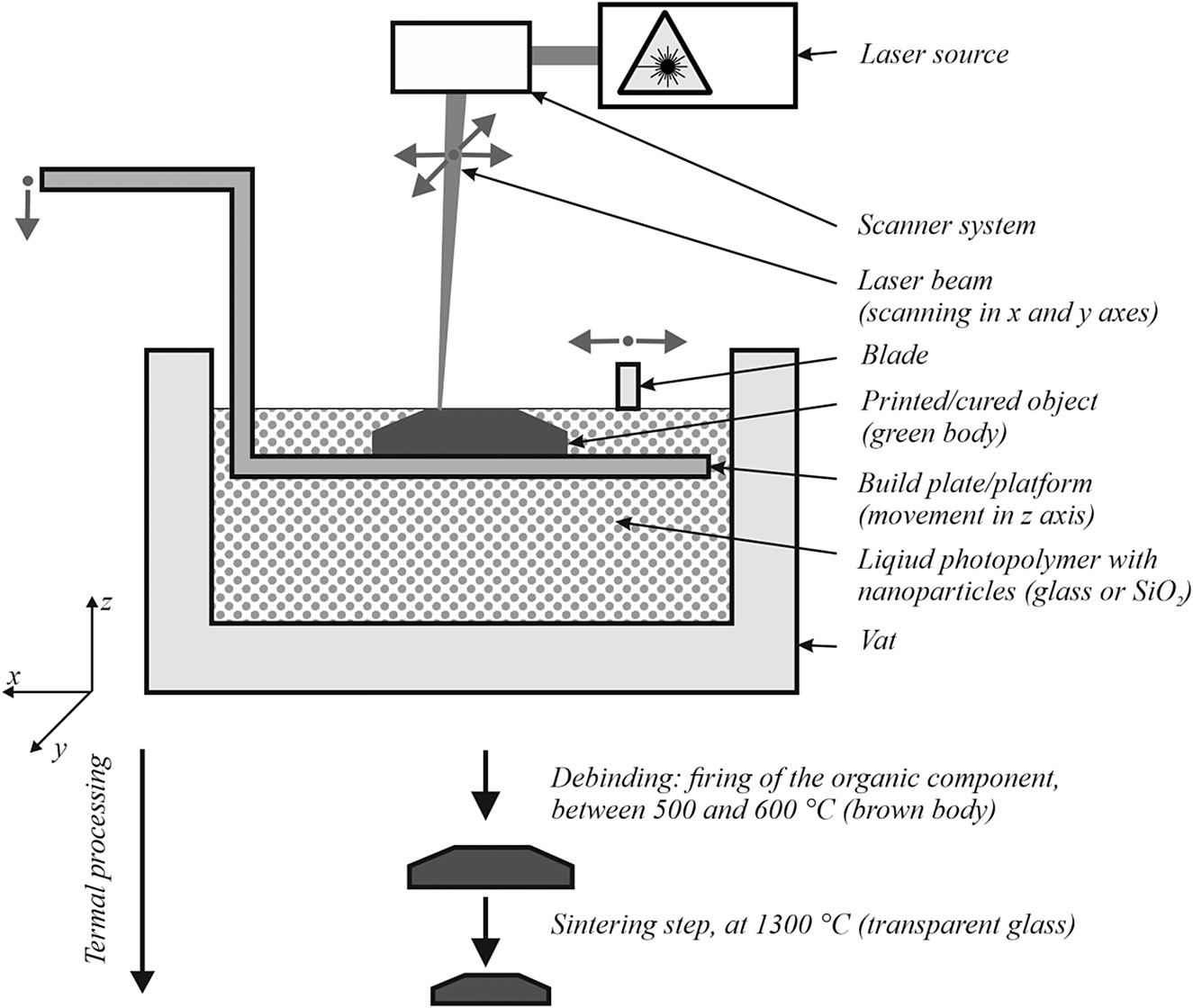

In the case of printing by photopolymerization [2], it is necessary to disperse the glass powder with a grain size in micrometers or nanometers in a suitable photopolymer with the addition of other substances (a similar process to the DIW technology). After printing (obtaining the “green body”), heat treatment is necessary. By removing the polymer (debinding), the so-called “brown body” is acquired, and the glass powder is then sintered into a transparent product. Because this principle uses existing and modified technologies, the know-how is based on the firing and subsequent sintering curve, together with the composition of the suspension for printing. This is a case of indirect acquisition.

An example of a technology using the oldest principle of 3D printing is stereolithography (SLA) [2]. This involves curing the liquid material in a defined layer of a specially designed silica paste [13, 23, 24], Fig. 4 (printing the “green body”). Kotz et al. [12, 13, 23, 24] named the silica paste “Glassomer”, which behaves like a polymer in 3D printing, but the final products, after subsequent heat treatment, have the properties of glass. The technology does not require high temperatures during printing, instead silica nanoparticles from 40 to 100 nm in size are dispersed as a suspension in a special polymer with a particle to polymer ratio of between 40:60 and 60:40. The polymer part is subsequently cured by heat and/or light. The silica-polymer paste may be formed in a perfect consistency with a highly detailed structure. However, to obtain a glass product, the polymer part must be removed. Firstly, the product is heated to a temperature of between 500 and 600 °C (a process known as debinding, obtaining the “brown body”), and then the product is sintered at 1300 °C. The amount of shrinkage of the final transparent product against the green body is reported to be 26.3 % for a ratio of silica nanoparticles to polymer of 40:60, and 15.6 % for a ratio of 60:40, respectively. Shrinkage is isotropic and may be calculated. The resulting product may also be further processed on production machines, “just like a conventional polymer”, whereby enabling the creation of smaller, more complex, and more detailed structures. It is stated that the Glassomer material may be milled, processed, or machined on a CNC machine in the same way as a conventional polymer. The researchers report that the technology leads to the production of clear glass materials suitable for applications in the optical, biotechnology, microelectronics, and medical industries [12, 13, 23, 24].

Diagram of the SLA principle for transparent glass.

Recently, the SLA process and the similar Digital Light Processing (DLP) process, have been widely studied and new modified silica pastes proposed [25], [26], [27], [28], [29], [30], [31]. As an example, we may cite the research of Arita et al. [29], who studied the use of SiO2 nanoparticles modified with polyethylenimine further complexed with oleic acid. Together with photo-initiator and multifunctional acrylates, a new formula of an interparticle photo-crosslinkable suspension for rapid 3D structuring with fast debinding and sintering was created. Also, a new multicomponent glass was proposed to compete with silica pastes. Liu et al. [25] proposed an SLA technique enhanced with so-called “solution impregnation” consisting of Eu3+, Tb3+, Ce3+ ions doped in pre-sintered silica glass parts. After further sintering at high temperatures, a 3D printed multicolor luminescent glass was fabricated in shapes and dimensions not obtainable with traditional glass-producing techniques. Likewise, Moore et al. [32] proposes the fabrication of multicomponent glass SLA-3D printed products of a SiO2–B2O3–P2O5 composition using phase-separating resins. Because most of the functional properties of glass emerge from its transparency and multicomponent nature, the SLA-3D printing platform proves to be useful for distinct technologies, sciences, and arts [32].

Powder bed fusion

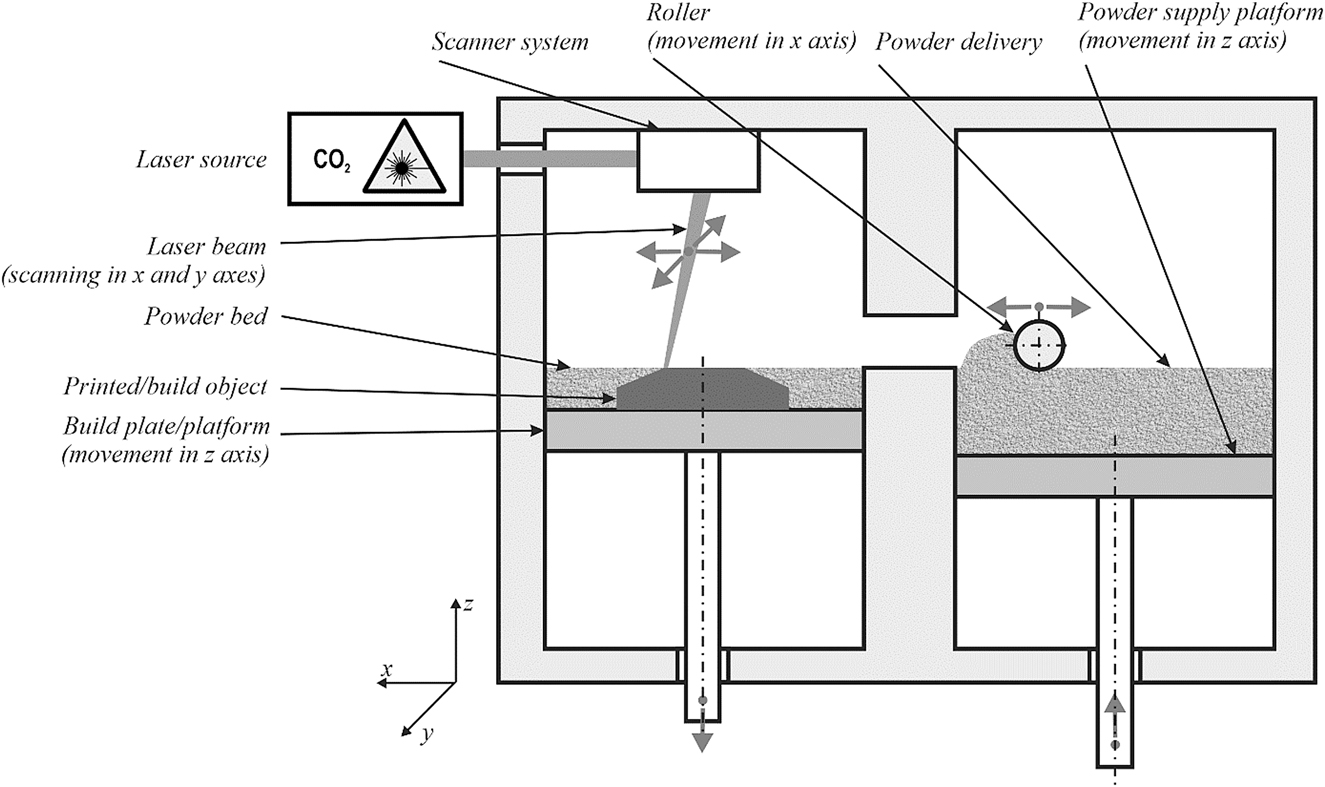

Several principles of 3D printing are again based on the general principle of powder bed fusion [2]. The most commonly applied is selective laser sintering (SLS). This technology is based on the principle that a thin layer of powder material is applied to the working surface. The beam focuses on a fine powder, which is melted by the laser, and forms one of many layers. The finished layer is covered with another layer of powder and the process is repeated [2].

An example of an application is high-temperature selective laser sintering (HT-SLS) [33], Fig. 5. The fused silica powder is applied layer-by-layer to the build plate, which moves downwards. Each layer is fixed with a laser, in this case with a CO2 laser. The advantage of the CO2 laser is its wavelength, which is around 10 µm. This wavelength is in the region where SiO2 is not transparent.

Diagram of the SLS principle for glass.

In this case, however, the product is opaque, as it contains small bubbles and probably also a ceramic phase (crystalline phase). A 3D printer with process-specific requirements has been developed for HT-SLS. An important requirement of a 3D printer is the ability to heat the workspace to high temperatures (up to 1000 °C) to increase the density and shorten the processing time. A small workspace chamber is required to effectively heat the 3D printer to the desired temperature, so the powder hopper is located externally. To maintain the required operating temperature, the entire furnace chamber must be thermally insulated, and water cooled. When using high-purity quartz glass powder, the risk of contamination of the powder throughout the process must be avoided. Therefore, the transport mechanisms and all the related surfaces are made of fused quartz or silica-based materials. Another requirement is the creation of a homogeneous powder bed, which is achieved by a conveying system consisting of a blade and a roller. The roller serves to increase the bulk density and the blade determines the defined height of the layer of applied glass powder [33].

Likewise, research of powder bed fusion also focuses on soda-lime glass systems, but so far with similar outcomes (opaque glass products with defects) [34], [35], [36]. However, laser and firing processing parameters, as well as particle sizing, etc. have been optimized, meaning that, in the future, powder bed fusion may guide the formation of a new generation of glass structures for a wide range of applications [36, 37].

Directed energy deposition

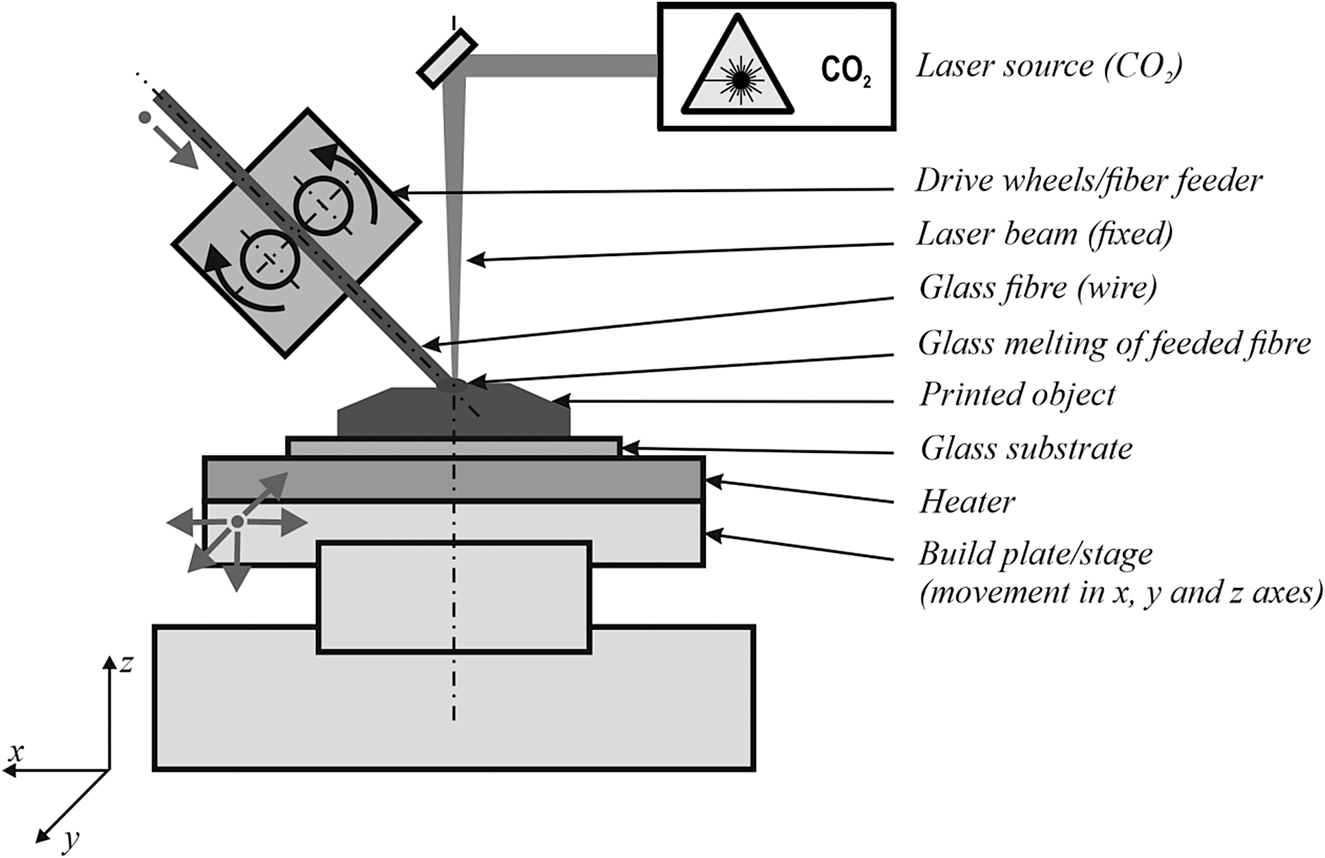

Direct energy deposition (DED) technology creates components by directly melting materials and applying them to the product layer-by-layer. The machine mostly consists of a nozzle and a very powerful source of thermal energy. The basic difference from material extrusion (e.g., FFF) is the mobility of the nozzles, which can move in several directions. DED technology may move in up to five different axes compared to only three in the case of material extrusion. Another difference is the melting of the applied material by a nozzle directly on the printed object. Most DED 3D printers are industrial machines with very large footprints that require a closed and controlled environment to operate [2].

An example of the use of this technology is in the production of optical elements, whereby glass fibers with a composition of soda-lime glass filaments with a diameter of 1 mm and fused quartz rods with a nominal diameter of 0.5 mm are used [38]. This technology also uses a CO2 laser and is known as wire-fed additive manufacturing, Fig. 6. The cited work presents the filament feed rates, laser power, the resulting shapes of the deposited layers, their optical properties, and also numerical simulations. However, laser exposure is also a very interesting problem for studying the chemical composition and arrangement of structural elements in the final product. It is apparent that different laser beam powers lead to different states within the exposed structure [38]. Likewise, von Witzendorf et al. [39] used an endless quartz glass-fiber melted with a CO2 laser to investigate the processing parameters of AM.

Diagram of DED: the wire-fed additive manufacturing principle with glass fibre.

Potential of 3D glass printing

There is clearly considerable potential for the use of 3D glass printing. As in the case of 3D plastic printing, it must be stated that it will not be possible to compete with mass production in the foreseeable future using the current technologies. Also, as in the case of 3D plastic printing, it is used primarily for one-off production, such as prototyping, patterning, mass customization, and artwork. Equally important is the production of products that cannot be produced by other technologies. These include internal structures, the joining of different types of glass with various properties (composition), and the joining of glass with other materials (ceramics, metals, …). It is expected that specific and expensive products will need to search for new applications and markets.

In addition to the possibilities of using 3D printing, it is necessary to mention the basic problems of the products. In addition to high shrinkage, especially for indirect acquisition technologies, basic shortcomings are also seen in the form of gaseous globules. These arise mainly from the pores formed by indirect acquisition, or from sintered powder in the case of powder bed fusion, bound powder in binder jetting, the application of single doses in material jetting, or from entrapment of the surrounding atmosphere in DED and material extrusion technologies. In the case of technologies for printing non-transparent materials, such as printing from most polymers and metals, gas globules do not affect the appearance of the material, but if optical purity is required for transparent glass (and transparent polymers), this may be a critical issue. In addition to these visible effects, there are other issues that are very important for certain applications. These many include the minimization of internal stress in the resulting glass product. Internal stress may arise when layers of different temperatures are joined separately, and the stress cannot be removed when joining materials with different rates of thermal expansion (glass and other materials). Another problem that can lead to internal stress, but also to a change in optical properties is crystallization (devitrification) under unsuitable temperature conditions, which may easily occur in 3D printing, due to e.g., inappropriate changes in exposure to thermal energy, especially in the case of direct acquisition technologies.

Material properties play a crucial role in selecting a given technology. In the case of the material of the final product, these are the properties for the printing itself, but also for the preparation of the batch and subsequent processing. In the case of equipment components, it is necessary to respect the properties of the input materials and, in the case of technologies working with increased heat, to respect the strong corrosive properties of the molten glass.

Physical and chemical processes also play a very important role in 3D printing technologies, as they may lead to changes and modifications in the properties of the resulting product. 3D printed glass products will also become much more diverse in terms of their composition than is currently the case with conventional glass production, which is often associated with soda-lime-silica glass.

Conclusions

The study shows that there are several technologies that have practical use for printing glass products. Therefore, 3D printing becomes a term for a whole range of technologies suitable for different types of products with specific properties. It is not possible to specify a clear trend, and a great variety may be expected, as in the case of 3D plastic printing. Changes in the composition of the glass of various parts of the product are promising, as is the joining of glass with other materials, which would not be possible using conventional technologies. However, these new possibilities bring many problems that will need to be solved, and there is plenty of space for research.

Funding source: Technical University of Liberec, Grant Program to Support Basic Research “PURE”

Acknowledgments

This article was written at the Technical University of Liberec as part of the Grant Program to Support Basic Research “PURE” in the framework of the project “Research of micro melting glass principles and properties of such obtained glass” (PURE 30006/117). The project is financed from institutional support for the long-term conceptual development of the research organization, provided in 2020 by the Ministry of Education, Youth and Sports of the Czech Republic.

References

[1] E. Le Bourhis. Glass: Mechanics and Technology, Wiley, New York, 2nd ed., https://www.wiley.com/en-ar/Glass %3A+Mechanics+and+Technology %2C+2nd+Edition-p-9783527679447 (accessed Nov 9, 2021).10.1002/9783527617029Search in Google Scholar

[2] C. Barnatt. ExplainingTheFuture.com : 3D Printing – The Next Industrial Revolution, https://www.explainingthefuture.com/3dp_book.html (accessed Nov 9, 2021).Search in Google Scholar

[3] ISO/ASTM 52900:2015(en). Additive manufacturing—General principles—Terminology, https://www.iso.org/obp/ui/#iso:std:iso-astm:52900:ed-1:v1:en (accessed Nov 9, 2021).Search in Google Scholar

[4] D. Zhang, X. Liu, J. Qiu. Front. Optoelectron. 14, 263–277 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12200-020-1009-z.Search in Google Scholar

[5] F. Oikonomopoulou, I. S. Bhatia, W. Damen, F. V. D. Weijst, T. Bristogianni. Rethinking the cast glass mould: an exploration on novel techniques for generating complex and customized geometries. Challenging Glass Conference Proceedings, p. 7 (2020).Search in Google Scholar

[6] K. V. Wong, A. Hernandez. ISRN Mech. Eng. 2012, e208760 (2012). https://doi.org/10.5402/2012/208760.Search in Google Scholar

[7] H. Bikas, P. Stavropoulos, G. Chryssolouris. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 83, 389–405 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00170-015-7576-2.Search in Google Scholar

[8] G. Marchelli, R. Prabhakar, D. Storti, M. Ganter. Rapid Prototyp. J. 17, 187–194 (2011).10.1108/13552541111124761Search in Google Scholar

[9] J. Klein, M. Stern, G. Franchin, M. Kayser, C. Inamura, S. Dave, J. C. Weaver, P. Houk, P. Colombo, M. Yang, N. Oxman. 3D Print. Addit. Manuf. 2, 92–105 (2015).10.1089/3dp.2015.0021Search in Google Scholar

[10] N. A. Dudukovic, L. L. Wong, D. T. Nguyen, J. F. Destino, T. D. Yee, F. J. Ryerson, T. Suratwala, E. B. Duoss, R. Dylla-Spears. ACS Appl. Nano Mater. 1, 4038–4044 (2018).10.1021/acsanm.8b00821Search in Google Scholar

[11] F. Kotz, N. Schneider, A. Striegel, A. Wolfschläger, N. Keller, M. Worgull, W. Bauer, D. Schild, M. Milich, C. Greiner, D. Helmer, B. E. Rapp. Adv. Mater. 30, 1707100 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1002/adma.201707100.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[12] F. Kotz, K. Arnold, W. Bauer, D. Schild, N. Keller, K. Sachsenheimer, T. M. Nargang, C. Richter, D. Helmer, B. E. Rapp. Nature 544, 337–339 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1038/nature22061.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[13] F. Oney. Newest glass material ‘Glassomer’ is used to fabricate small glass structures, The American Ceramic Society, Columbus (2018), https://ceramics.org/ceramic-tech-today/biomaterials/newest-glass-material-glassomer-is-used-to-fabricate-small-glass-structures (accessed Nov 9, 2021).Search in Google Scholar

[14] E. Baudet, Y. Ledemi, P. Larochelle, S. Morency, Y. Messaddeq. Opt. Mater. Exp., OME. 9, 2307–2317 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1364/ome.9.002307.Search in Google Scholar

[15] Glass I (G3DP). Kayser Works, https://kayserworks.com/053204149098 (accessed Nov 13, 2021).Search in Google Scholar

[16] C. Inamura, M. Stern, D. Lizardo, P. Houk, N. Oxman. 3D Print. Addit. Manuf. 5, 269–283 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1089/3dp.2018.0157.Search in Google Scholar

[17] R. M. Zaki, C. Strutynski, S. Kaser, D. Bernard, G. Hauss, M. Faessel, J. Sabatier, L. Canioni, Y. Messaddeq, S. Danto, T. Cardinal. Mater. Des. 194, 108957 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.matdes.2020.108957.Search in Google Scholar

[18] D. T. Nguyen, C. Meyers, T. D. Yee, N. A. Dudukovic, J. F. Destino, C. Zhu, E. B. Duoss, T. F. Baumann, T. Suratwala, J. E. Smay, R. Dylla-Spears. Adv. Mater. 29, 1701181 (2017), https://doi.org/10.1002/adma.201701181.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[19] J. F. Destino, N. A. Dudukovic, M. A. Johnson, D. T. Nguyen, T. D. Yee, G. C. Egan, A. M. Sawvel, W. A. Steele, T. F. Baumann, E. B. Duoss, T. Suratwala, R. Dylla-Spears. Adv. Mater. Technol. 3, 1700323 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1002/admt.201700323.Search in Google Scholar

[20] K. Sasan, A. Lange, T. D. Yee, N. Dudukovic, D. T. Nguyen, M. A. Johnson, O. D. Herrera, J. H. Yoo, A. M. Sawvel, M. E. Ellis, C. M. Mah, R. Ryerson, L. L. Wong, T. Suratwala, J. F. Destino, R. Dylla-Spears. ACS Appl. Mater. Interf. 12, 6736–6741 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1021/acsami.9b21136.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[21] R. Dylla-Spears, T. D. Yee, K. Sasan, D. T. Nguyen, N. A. Dudukovic, J. M. Ortega, M. A. Johnson, O. D. Herrera, F. J. Ryerson, L. L. Wong. Sci. Adv. 6, eabc7429 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.abc7429.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[22] A. Dasan, P. Ożóg, J. Kraxner, H. Elsayed, E. Colusso, L. Grigolato, G. Savio, D. Galusek, E. Bernardo. Materials 14, 5083 (2021). https://doi.org/10.3390/ma14175083.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[23] F. Kotz, A. S. Quick, P. Risch, T. Martin, T. Hoose, M. Thiel, D. Helmer, B. E. Rapp. Adv. Mater. 33, 2006341 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1002/adma.202006341.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[24] F. Kotz, N. Schneider, A. Striegel, A. Wolfschläger, N. Keller, M. Worgull, W. Bauer, D. Schild, M. Milich, C. Greiner, D. Helmer, B. E. Rapp. Adv. Mater. 30, 1707100 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1002/adma.201707100.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[25] C. Liu, B. Qian, R. Ni, X. Liu, J. Qiu. RSC Adv. 8, 31564–31567 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1039/c8ra06706f.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[26] I. Cooperstein, E. Shukrun, O. Press, A. Kamyshny, S. Magdassi. ACS Appl. Mater. Interf. 10, 18879–18885 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1021/acsami.8b03766.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[27] C. Liu, B. Qian, X. Liu, L. Tong, J. Qiu. RSC Adv. 8, 16344–16348 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1039/c8ra02428f.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[28] P. Cai, L. Guo, H. Wang, J. Li, J. Li, Y. Qiu, Q. Zhang, Q. Lue. Ceram. Int. 46, 16833–16841 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ceramint.2020.03.260.Search in Google Scholar

[29] R. Arita, M. Iijima, Y. Fujishiro, S. Morita, T. Furukawa, J. Tatami, S. Maruo. Commun. Mater 1, 1 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1038/s43246-020-0029-y.Search in Google Scholar

[30] F. B. Löffler, E. C. Bucharsky, K. G. Schell, S. Heißler, M. J. Hoffmann. J. Eur. Ceram. Soc. 40, 4556–4561 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jeurceramsoc.2020.05.023.Search in Google Scholar

[31] J. Köpfler, T. Frenzel, J. Schmalian, M. Wegener. Adv. Mater. 33, 2103205 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1002/adma.202103205.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[32] D. G. Moore, L. Barbera, K. Masania, A. R. Studart. Nat. Mater. 19, 212–217 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41563-019-0525-y.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[33] A. Bruder. Development of a 3D-printer for HT-SLS of fused silica powder. Joint meeting of DGG, ČSS & SSS Proceeding of 92nd Annual Meeting of the German Society of Glass Technology in Conjunction with the Annual Meetings of the Czech Glass Society & the Slovak Glass Society, 28 – 30 May 2018, Bayreut (2018).Search in Google Scholar

[34] M. Fateri, A. Gebhardt. Int. J. Appl. Ceram. Technol. 12, 53–61 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1111/ijac.12338.Search in Google Scholar

[35] K. C. Datsiou, E. Saleh, F. Spirrett, R. Goodridge, I. Ashcroft, D. Eustice. J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 102, 4410–4414 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1111/jace.16440.Search in Google Scholar

[36] K. C. Datsiou, F. Spirrett, I. Ashcroft, M. Magallanes, S. Christie, R. Goodridge. Addit. Manuf. 39, 101880 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addma.2021.101880.Search in Google Scholar

[37] J. Lei, Y. Hong, Q. Zhang, F. Peng, H. Xiao. Additive manufacturing of fused silica glass using direct laser melting. In 2019 Conference on Lasers and Electro-Optics (CLEO), pp. 1–2 (2019).10.1364/CLEO_AT.2019.AW3I.4Search in Google Scholar

[38] J. Luo, L. J. Gilbert, C. Qu, R. G. Landers, D. A. Bristow, E. C. Kinzel. J. Manuf. Sci. Eng. 139, 061006 (2017), https://doi.org/10.1115/1.4035182.Search in Google Scholar

[39] P. von Witzendorff, L. Pohl, O. Suttmann, P. Heinrich, A. Heinrich, J. Zander, H. Bragard, S. Kaierle. Procedia CIRP 74, 272–275 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.procir.2018.08.109.Search in Google Scholar

© 2021 IUPAC & De Gruyter. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. For more information, please visit: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Preface

- 14th Conference on Solid State Chemistry

- Conference papers

- Strong emission at 1000 nm from Pr3+/Yb3+-codoped multicomponent tellurite glass

- Pressure assisted sintering of Al2O3–Y2O3 glass microspheres: sintering conditions, grain size, and mechanical properties of sintered ceramics

- Present state of 3D printing from glass

- Raman spectra of MCl-Ga2S3-GeS2 (M = Na, K, Rb) glasses

- The chemistry of melting oxynitride phosphate glasses

- Structure and magnetic properties of Bi-doped calcium aluminosilicate glass microspheres

- Special Topic Paper

- Synthesis design using mass related metrics, environmental metrics, and health metrics

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Preface

- 14th Conference on Solid State Chemistry

- Conference papers

- Strong emission at 1000 nm from Pr3+/Yb3+-codoped multicomponent tellurite glass

- Pressure assisted sintering of Al2O3–Y2O3 glass microspheres: sintering conditions, grain size, and mechanical properties of sintered ceramics

- Present state of 3D printing from glass

- Raman spectra of MCl-Ga2S3-GeS2 (M = Na, K, Rb) glasses

- The chemistry of melting oxynitride phosphate glasses

- Structure and magnetic properties of Bi-doped calcium aluminosilicate glass microspheres

- Special Topic Paper

- Synthesis design using mass related metrics, environmental metrics, and health metrics