Abstract

Oxide glasses are the most commonly studied non-crystalline materials in Science and Technology, though compositions where part of the oxygen is replaced by other anions, e.g. fluoride, sulfide or nitride, have given rise to a good number of works and several key applications, from optics to ionic conductors. Oxynitride silicate or phosphate glasses stand out among all others because of their higher chemical and mechanical stability and their research continues particularly focused onto the development of solid electrolytes. In phosphate glasses, the easiest way of introducing nitrogen is by the remelting of the parent glass under a flow of ammonia, a method that allows the homogeneous nitridation of the bulk glass and which is governed by diffusion through the liquid-gas reaction between NH3 and the PO4 chemical groupings. After nitridation, two new structural units appear, the PO3N and PO2N2 ones, where nitrogen atoms can be bonded to either two or three neighboring phosphorus, thus increasing the bonding density of the glass network and resulting in a quantitative improvement of their properties. This short review will gather all important aspects of the synthesis of oxynitride phosphate glasses with emphasis on the influence of chemical composition and structure.

Introduction

Nitride and oxynitrides are a class of materials with important applications in quite relevant fields, such as catalysis [1], light conversion phenomena [2] or batteries electrochemistry [3]. The term refers to a solid where part of the oxygen, or all, of a reference oxide has been replaced by nitrogen. Despite the thermodynamic hindrance of the nitridation reactions, due to the higher stability of the N≡N bond, many synthesis methods have been successfully developed so far in the preparation of a broad range of nitrided inorganic solids. The first experiments on the synthesis of oxynitride glasses were performed when studying the dissolution of nitrogen into silicate and borate melts by Mulfinger [4] throughout the bubbling of N2, N2/H2 and NH3 gases, though reaching contents of less than 1 wt% N. But the importance of nitrogen containing glasses became with the discovery of the formation of glassy oxynitride phases at the grain boundaries during the sintering of Si3N4 ceramics [5], starting the research on SiAlON glasses and ceramics.

The birth of oxynitride phosphate glasses started when Roger Marchand at the University of Rennes tried the ammonolysis of a sodium metaphosphate glass at temperatures up to 750 °C, reaching nitrogen contents near 10 wt% [6]. Thereafter, many investigations were produced, notably by the groups of Marchand in France [7], Day in USA [8] and Durán in Spain [9]. Phosphate glasses are known to have low transition temperatures in parallel with high coefficients of thermal expansion, which make them appropriate as low temperature sealing glasses; however, due to the very high dissolution rates in water and humid media, their applicability was always very limited. With the advent of nitrogen containing phosphate glasses, this problem was solved at the same time that thermal characteristics were kept under desirable limits. In the beginnings, most of the research was oriented to develop new phosphate sealing glasses containing nitrogen. But in 1995 the group of Bates at the Oak Ridge National Laboratory showed the first results on the increase of ionic conductivity in lithium phosphate glasses after the incorporation of nitrogen [10]. This was very important as it gave rise to a new field of research on the study of the so-called LiPON solid electrolytes that were successfully introduced into thin-film lithium microbatteries by RF magnetron sputtering from Li3PO4 films [11]. Meanwhile most of LiPON amorphous films have been produced by physical deposition methods, new synthesis routes have also been tested in order to facilitate the preparation of bulk oxynitride phosphates with high contents of lithium, such as by mechanical milling, and simultaneously allowing the introduction of other elements which can also contribute to a notable improvement of the searched properties, such sulfide anions [12].

This work will give a short overview of the main parameters that govern the nitridation reactions through the ammonolysis of the phosphate melts under ammonia, describing the influence of temperature and time of reaction, viscosity of the melt as well as composition and structure of the glasses.

Melting of oxynitride phosphate glasses

Due to the much lower viscosities of the phosphate melts compared to silicates, oxynitride phosphate glasses can be nitrided in liquid state by reaction with NH3 gas at relatively low temperatures, though always below 800 °C from which reduction of phosphorus can take place. Therefore, two steps must be done to achieve the oxynitride glass, a first melting of the parent oxide glass which is done by normal melting and quenching of the raw materials batch, followed by the ammonolysis reaction under a constant NH3 flow. The chemical reaction between the metaphosphate melt and ammonia can be described as:

being M a metal, or a combination of metals, typically alkali and alkaline-earths, than compensate the charge of the phosphate anion. Because no quenching of the resultant oxynitride is done after the reaction time, the material of the crucible or boat that contains the glass is important to easily remove the glass once cooled to room temperature. An isostatic type and low porosity graphite crucible has been traditionally used in our laboratory, which does not interact with the phosphate melt at the reaction temperature and the final glass does not stick to it once cooled to room temperature. The step of heating up the furnace and that of cooling down from the remelting temperature, are down under N2 flow, which helps eliminating oxygen or ammonia from the furnace and keeps a constantly reduced atmosphere before and after the ammonolysis.

The phosphate glass network is built up of PO4 though, unlike in silicates, one of the oxygens remains doubly bonded to phosphorus in order to compensate for the 5+ valence of P. In a metaphosphate composition, two of the oxygens are shared by neighboring phosphorus, the bridging oxygens (BO), while the two other are the so-called non-bridging oxygens (NBO) and coordinate the modifier metal cations. Once the melt reacts with NH3, nitrogen may substitute for both bridging and non-bridging oxygens giving rise to two new structural groupings, the PO3N and PO2N2. The higher bonding density of the oxynitride glasses with respect to the one in the oxide glasses has great consequences on their properties; the chemical resistance to hydration, their mechanical properties, the refractive index and even the stability against crystallization, all are improved.

Nitrogen content in glasses is usually determined by the inert gas fusion method from which the wt% of nitrogen is obtained and then converted to the N/P ratio. For a sodium metaphosphate glass with composition NaPO3, the formula for an oxynitride glass stands for NaPO3−3x/2N x , being x the N/P ratio and where three atoms of O2− are substituted by two atoms of N3−.

Nitridation kinetics

At the usual nitridation temperatures the glass converts to the liquid state and the chemical reaction described above proceeds via the diffusion of ammonia within the melt. Thus, besides temperature and reaction time, the viscosity of the melt will determine how easy the nitrogen can substitute for oxygen in the structure. Nitridation at constant time showed that the incorporated nitrogen increases linearly with the reaction temperature (N/P = a + b⋅T), while, for a fixed temperature, the nitrogen content varies with the square root of time (N/P = c⋅√t). It is worth mentioning that higher temperatures, for the same reaction time, allows introducing higher nitrogen contents; however, all temperature dependent lines fall down onto a temperature of ca. 550 °C, below which no nitrogen is introduced as it was shown in alkali-lead metaphosphate glasses [13]. Decomposition of ammonia into H2 and N2 may start occurring at temperatures above 400 °C, although reaction with nitrogen or hydrogen/nitrogen mixtures does not produce nitridation of the glasses. Actually, the ammonia flow must always be kept above a minimum level within the furnaces to ensure that nitridation proceeds homogeneously. At 550 °C the alkali-lead metaphosphate glasses presented a viscosity of ca. 0.2 Pa.s, in Log units, that may be determine that the nitridation reaction can only take place in melts with lower viscosities. On the other hand, nitridation at higher temperatures is limited by the fact that above 800 °C phosphorus can be reduced to phosphine, giving rise to brownish colored glasses and even crystallizations within the glasses. So the temperature window for the ammonolysis of phosphate melts is relatively small, of about 200 °C, and the composition of the glasses must be chosen with care in order to facilitate their nitridation at those temperatures. Another relevant fact that shows how important the melt viscosity is for the nitridation is the one that the introduced nitrogen content is inversely proportional to the initial melt viscosity. This was very well shown in the nitrogen content introduced into alkali-lead metaphosphate glasses in which the viscosity was previously determined [13]. Furthermore, it is worth pointing out that for the same viscosity of the phosphate melt, the nitrogen content will also be determined by the composition throughout the ionic field strength of the modifier elements.

The nitridation reaction in phosphate melts was described assuming that both BO and NBO type oxygens of the network would be substituted by nitrogen. Thus, tri-coordinated nitrogen atoms (N t ) appear after substitution of BO (N t = 3/2BO) while di-coordinated nitrogen (N d ) after substitution of both BO and NBO (N d = NBO + 1/2BO) [14]. These two substitution rules would progressively give rise to an oxynitride network where the PO3N groups are formed first when introducing nitrogen into the original PO4 units; then, PO2N2 groups would appear as a consequence on substituting nitrogen for oxygen in the PO3N formed before, giving rise to PO2N2 and new PO3N [15]. The two reactions can be represented by the following equations:

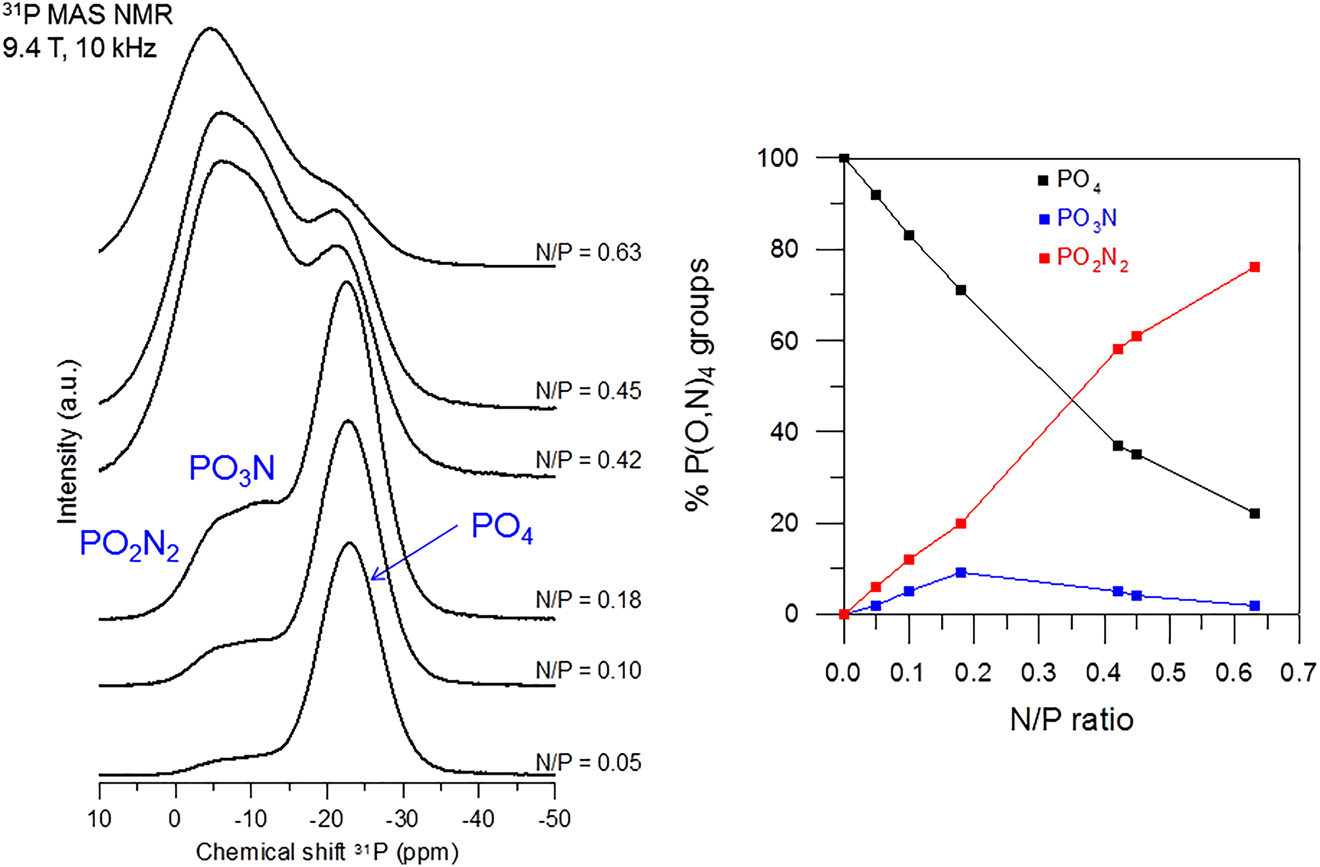

The two reactions would respectively have their constant of reaction, k 1 and k 2, and were demonstrated to form a system of two pseudo-first order reactions with similar activation energies of ca. 150 kJ.mol−1 in nitrided Li0.25Na0.25Pb0.25PO3−3x/2N x glasses [16]. In these type of systems, there is a time, t max, at which there is a maximum of formation of PO3N groups from the PO4 ones. Above t max, PO2N2 start forming in a bigger amount from the joints PO4–PO3N if both reaction constants are similar. The reaction constants were determined in Li0.25Na0.25Pb0.25PO3−3x/2N x glasses thanks to a study by Nuclear Magnetic Resonance spectroscopy of the contents of chemical groupings in the glasses obtained at temperatures between 600 and 700 °C and times up to 30 h. The results of speciation by NMR are similar in alkali or alkali-lead metaphosphates and so it is expected that reaction constants and activation energies are similar in all systems. However, it has been recently found that nitridation of LiPO3 and NaPO3 glasses gives rise to quite different results regarding the chemical speciation. Figs. 1 and 2 show the 31P MAS NMR spectra and % of P(O,N)4 groups against the N/P ratio in LiPO3−3x/2N x and NaPO3−3x/2N x , respectively. NMR spectra show the three characteristic resonances attributed to the PO4, PO3N and PO2N2 groups of nitrided glasses, which relative content to total phosphorus can be represented against the nitrogen content; however, meanwhile the content of PO4 groups decreases with introduced nitrogen similarly in both systems, the increase of PO3N and PO2N2 presents a distinct behavior. The one in NaPO3−3x/2N x glasses (Fig. 2) resembles the one previously observed in Li0.5Na0.5PO3−3x/2N x as well as in Li0.25Na0.25Pb0.25PO3−3x/2N x glasses but it can be clearly seen that the content of PO2N2 in LiPO3−3x/2N x glasses is always higher than the one of PO3N. Despite no conclusive explanation has been yet given to this fact, it looks very likely that the value of the k 2 reaction constant of reaction (2) adopts much higher values than k 1 in the LiPO3−3x/2N x , so that once PO3N groups are formed they are immediately converted to PO2N2 upon further nitrogen for oxygen substitution. A subtle structural interpretation must be at the origin of the behavior in the contents of nitrided groups with different alkali modifier. It has also been speculated that this would have occurred because of a kind of phase separation or segregation of nitrided regions within the phosphate glass matrix. However, no definitive answer has yet been obtained even after high temperature 31P MAS NMR experiments in both systems were performed that showed similar mixing of P(O,N)4 groups with PO4 ones independently of the modifier element [17].

31P MAS NMR spectra of LiPO3−3x/2N x glasses and content of P(O,N)4 groups of oxynitride glasses against the N/P ratio.

![Fig. 2:

31P MAS NMR spectra [18] of NaPO3−3x/2N

x

glasses and content of P(O,N)4 groups of oxynitride glasses against the N/P ratio.](/document/doi/10.1515/pac-2021-0704/asset/graphic/j_pac-2021-0704_fig_002.jpg)

31P MAS NMR spectra [18] of NaPO3−3x/2N x glasses and content of P(O,N)4 groups of oxynitride glasses against the N/P ratio.

Influence of glass composition

The key factor that will determine the feasibility of nitridation is the viscosity of the melt, so the composition of the glass will need to be chosen to allow having very low viscosities at temperatures below 800 °C. Alkali phosphate glasses can be nitrided without problem, provided that they do not crystallize upon cooling, such it can happen in KPO3 containing melts. Alkaline-earth phosphate would not be nitrided since their higher viscosity and so a combination of alkali and alkaline-earth element will be required. Other metals that can be incorporated into the composition and allow nitridation can be Zn, Pb and Sn. The last three are known to lower the viscosity of their respective melts and given that they are combined with alkalis, can produce compositions easily nitrided. The case of Sn is special, because in oxidative atmospheres Sn2+ can be oxidize to Sn4+ and precipitate as SnP2O7 crystals which are very refractory, producing inhomogeneous glasses. However, under the reducing atmosphere of the nitridation (N2 + NH3), Sn4+ is completely reduced to Sn2+, which does not crystallize in the form of phosphate, and can be completely dissolved within the glass network. This is related to the fact that the nitridation of phosphate glasses incorporating elements, notably transition metal elements, whose reduction potential is positive, give rise to precipitation of the elemental metals after the nitridation. However, those elements with negative reduction potentials, such as alkali and alkaline-earths, remain in their oxidize states after the nitridation. In the case of Sn, the reaction Sn4+ → Sn2+ has an E 0 = 0.15 V, while the E 0 for the reaction Sn4+ → Sn2+ stands for −0.14 V. The reducing character of oxynitride phosphate glasses was very well studied by Le Sauze et al. in Ag and Cu containing phosphate glasses [19]. Other transition metals like La or Ti could also be in the composition of the phosphate parent glass; however, even small contents of their oxides may provoke a quite big increase of the melt viscosity, thus limiting the possibilities of nitridation at relatively low temperatures.

Secondary glass former elements such as B or Si could be added to the glass composition although the nitrogen content that can be reached will be reduced with their content [20]. In general, the higher viscosities of B2O3 and SiO2 containing phosphate glasses will diminish the introduction of nitrogen and for high boron contents, phase separation and crystallization of reduced boron in the form of BN can be produced. On the other hand, phosphate glasses containing other anionic species such as SO4 2−, S2− and F- have been nitrided with very different results. Sulpho-phosphate glasses, or SO3 containing phosphate glasses, were nitrided with unfortunate results because SO4 2− species are reduced to volatile species and the drastic composition change of the glasses results in crystallized samples. On the other hand, S2− containing glasses were also tested resulting also in inhomogeneous samples. However, introduction of S2− anions bonded to phosphorus is possible if done on a previously nitrided glass. This was demonstrated by remelting a nitrided lithium metaphosphate glass with Li2S under an Ar atmosphere [21]. The analysis of the composition and structure of the glasses revealed that S atoms are bonded to two neighboring phosphorus and are present simultaneously with the PO3N and PO2N2 groups of the oxynitride network. The preparation of this kind of glasses was highlighted because one may see the effects of adding nitride as well as sulfide anions. On the one hand, nitrogen increases the chemical and mechanical stability of the glasses and, as seen above, in nitridation of lithium phosphate glasses produces an increase of the lithium ionic conductivity which is particularly relevant for the application as solid electrolytes. But, on the other hand, the fact of adding also S2−, which is a more polarizable anion, results in solids with even higher ionic conductivity than with N3− alone, which has open up a new field of research in solid electrolytes for battery applications. LiF containing phosphate glasses are known to have much smaller glass transition temperatures, lower viscosity though poor chemical durability. The nitridation of fluoride containing phosphates was also investigated using a similar methodology than the one used in the processing of sulfide containing oxynitrides. Nitrided lithium phosphate glasses were obtained by melt and quenching followed by ammonolysis and the oxynitride glasses were then re-melted under a N2 with increasing contents of LiF [22]. The results showed that the glass transition temperatures of the oxy-fluoro-nitride lithium phosphate glasses are higher than those of the fluoro-phosphate glasses, due to the increased cross-link density of the glass network through the P–N bonds. Furthermore, thanks to the effect of nitrogen on the melt viscosity, it was possible to incorporate higher contents of LiF within the oxynitride glasses without spontaneous crystallization upon cooling. This permitted to have glasses with even higher Li contents and thus higher ionic conductivities at the same time that higher chemical durability [23].

Homogeneity of oxynitride glasses

Because the main applications for which oxynitride glasses have been researched were focused on sealing glasses or solid electrolytes, the transparency and optical quality of oxynitride glasses has not been a key issue neither in phosphate glasses nor in silicate glasses in general. Ali et al. recently published a work analyzing the main issues of the preparation of transparent oxynitride silicate glasses [24], where they concluded that the advantages in the properties of oxynitride silicate glasses were not that higher considering the costs of the preparation and the much lower quality of the nitrogen containing glasses. Silicate glasses in particular have a main drawback related to the much higher temperatures required to run the nitridation via ammonolysis. Furthermore, the strong reducing atmosphere produces very frequently appearance of impurities in the form of elemental silicon or silicides that deteriorate much the optical quality of the final glasses.

Phosphate glasses, however, when nitrided at low temperatures do not present parallel reduction reactions and can be prepared without impurities. The major issue related to their preparation is the presence of bubbles that increases with the content of nitrogen due to the much higher viscosity of the nitrided melts than that of the non-nitrided phosphate one. Oxynitride phosphate glasses with relatively low nitrogen contents, typically below 4 wt%, can thus be prepared with very few defects and without important loss of their transparency. This last has been studied recently in Nd2O3 doped phosphate glasses, which can be nitrided and obtained with relatively good optical properties [25]. However, and because of the release of water as a product of the ammonolysis reaction, the oxynitride glasses will content some residual water that will affect negatively to the Nd luminescence as the nitrogen content in increased due to non-radiative quenching by OH ions in the glass. Fig. 3 shows the example of four nitrided Nd phosphate glasses with increased nitrogen contents from left to right. Despite no bubbles are appreciated, it is clear that stria are formed within the bulk glasses due mostly to the presence of water. In their study, Muñoz et al. did also observe that a further remelting of an oxynitride glass under N2 flow for 3 h conducts to a new oxynitride glass with an increased transparency at ca. 3000 cm−1 as observed by FTIR spectroscopy. This was attributed to a partial release of water from the melt that consequently carried out a small decrease of the nitrogen content. However, the good point is that the life time of neodymium luminescence was also increased. The same dehydroxylation procedure was later investigated in Nd2O3 doped phosphate glasses with very good results of their optical properties [26] and used to prepare an oxide glass to be subsequently nitrided [27]. The progressive nitridation of a homogeneous and water free phosphate glass produces the appearance of stria even for very low nitrogen contents, thus limiting their applicability as optical media for which differences of refractive index must be kept as low as possible. Despite the difficulties in the preparation of homogenous oxynitride phosphate glasses with adequate optical quality, several other investigations have been carried out in this topic, such as on the luminescence properties of ZnO containing phosphates that were prepared by common ammonolysis [28], or on that of Eu2O3-doped glasses that have been prepared by adding AlN to the phosphate batches [29].

Nitrided Nd-doped phosphate glasses with increased nitrogen contents from left to right.

Conclusions

Oxynitride phosphate glasses have demonstrated to possess a very rich chemistry that allows for the design of a broad range of materials with varied properties and applications. Nitrogen incorporation in the phosphate glass structure can improve, like no other element, the most relevant properties thanks to the increased bonding density. Their ever increasing interest as solid state electrolytes, in combination with other glass former elements or anions, will definitively widen the range of materials with good performances in the field of energy harvesting applications. On the other hand, it is thought that new preparation methods will continuously improve the glass quality and open quite new perspectives for their application as optically active materials.

Article note:

A collection of invited papers based on presentations at the 14th International Conference on Solid State Chemistry (SSC 2021) held in Trencin, Slovakia, June 13–17, 2021.

Funding source: AEI/FEDER

Award Identifier / Grant number: MAT2017-87035-C2-1-P

-

Research funding: This work was funded by AEI/FEDER from project MAT2017-87035-C2-1-P.

References

[1] T. Takata, K. Domen. Dalton Trans. 46, 10529 (2017), https://doi.org/10.1039/c7dt00867h.Search in Google Scholar

[2] F. J. Pucher, A. Marchuk, P. J. Schmidt, D. Wiechert, W. Schnick. Chem. Eur. J. 21, 6443 (2015), https://doi.org/10.1002/chem.201500047.Search in Google Scholar

[3] J. Liu, D. Chang, P. Whitfield, Y. Janssen, X. Yu, Y. Zhou, J. Bai, J. Ko, K.-W. Nam, L. Wu, Y. Zhu, M. Feygenson, G. Amatucci, A. Van der Ven, X.-Q. Yang, P. Khalifah. Chem. Mater. 26, 3295 (2014), https://doi.org/10.1021/cm5011218.Search in Google Scholar

[4] H. O. Mulfinger. J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 49, 462 (1966), https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1151-2916.1966.tb13300.x.Search in Google Scholar

[5] K. H. Jack. J. Mater. Sci. 11, 1135 (1976), https://doi.org/10.1007/bf02396649.Search in Google Scholar

[6] R. Marchand. C. R. Acad. Sci. Paris 294, 91 (1982).Search in Google Scholar

[7] L. Boukbir, R. Marchand, Y. Laurent, C. J. Zhao, C. Parent, G. Le Flem. J. Solid State Chem. 87, 423 (1990), https://doi.org/10.1016/0022-4596(90)90045-y.Search in Google Scholar

[8] M. R. Reidmeyer, D. E. Day. J. Non-Cryst. Solids 181, 201 (1995), https://doi.org/10.1016/s0022-3093(94)00511-7.Search in Google Scholar

[9] L. Pascual, A. Durán. Mater. Res. Bull. 31, 77 (1996), https://doi.org/10.1016/0025-5408(95)00152-2.Search in Google Scholar

[10] B. Wang, B. S. Kwak, B. C. Sales, J. B. Bates. J. Non-Cryst. Solids 183, 297 (1995), https://doi.org/10.1016/0022-3093(94)00665-2.Search in Google Scholar

[11] X. Yu, J. B. Bates, G. E. JellisonJr., F. X. Hart. J. Electrochem. Soc. 144, 524 (1997), https://doi.org/10.1149/1.1837443.Search in Google Scholar

[12] N. Mascaraque, J. L. G. Fierro, F. Muñoz, A. Durán, Y. Ito, Y. Hibi, R. Harada, A. Kato, A. Hayashi, M. Tatsumisago. J. Mater. Res. 30, 2940 (2015), https://doi.org/10.1557/jmr.2015.128.Search in Google Scholar

[13] F. Muñoz, A. Durán, L. Pascual, R. Marchand. Phys. Chem. Glasses 46, 39 (2005).Search in Google Scholar

[14] R. Marchand, D. Agliz, L. Boukbir, A. Quemerais. J. Non-Cryst. Solids 103, 35 (1988), https://doi.org/10.1016/0022-3093(88)90413-9.Search in Google Scholar

[15] A. Le Sauze, L. Montagne, G. Palavit, F. Fayon, R. Marchand. J. Non-Cryst. Solids 263&264, 139 (2000), https://doi.org/10.1016/s0022-3093(99)00630-4.Search in Google Scholar

[16] F. Muñoz. Phys. Chem. Glasses Eur. J. Glass Sci. Technol. 52, 181 (2011).Search in Google Scholar

[17] F. Muñoz, J. Ren, L. Van Wüllen, T. Zhao, H. Kirchhain, U. Rehfuss, T. Uesbeck. J. Phys. Chem. C 125, 4077 (2021).10.1021/acs.jpcc.0c10427Search in Google Scholar

[18] F. Muñoz, L. Delevoye, L. Montagne, T. Charpentier. New insights into the structure of oxynitride NaPON phosphate glasses by 17-oxygen NMR, J. Non-Cryst. Solids 363, 134–139 (2013), doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jnoncrysol.2012.12.028.Search in Google Scholar

[19] A. Le Sauze, E. Gueguen, R. Marchand. J. Non-Cryst. Solids 217, 83 (1997), https://doi.org/10.1016/s0022-3093(97)00152-x.Search in Google Scholar

[20] G. L. Paraschiv, F. Muñoz, G. Tricot, N. Mascaraque, L. R. Jensen, Y. Yue, M. M. Smedskjaer. J. Non-Cryst. Solids 462, 51 (2017), https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jnoncrysol.2017.02.011.Search in Google Scholar

[21] N. Mascaraque, H. Takebe, G. Tricot, J. L. G. Fierro, A. Durán, F. Muñoz. J. Non-Cryst. Solids 405, 159 (2014), https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jnoncrysol.2014.09.011.Search in Google Scholar

[22] N. Mascaraque, G. Tricot, B. Revel, A. Durán, F. Muñoz. Solid State Ionics 254, 40 (2014), https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssi.2013.10.061.Search in Google Scholar

[23] N. Mascaraque, A. Durán, F. Muñoz. J. Non-Cryst. Solids 417–418, 60 (2015), https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jnoncrysol.2015.03.019.Search in Google Scholar

[24] S. Ali, B. Jonson, M. J. Pomeroy, S. Hampshire. Ceram. Int. 41, 3345 (2015), https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ceramint.2014.11.030.Search in Google Scholar

[25] F. Muñoz, A. Saitoh, R. J. Jiménez-Riobóo, R. Balda. J. Non-Cryst. Solids 473, 125 (2017).10.1016/j.jnoncrysol.2017.08.005Search in Google Scholar

[26] F. Muñoz, R. Balda. Int. J. Appl. Glass Sci. 10, 157 (2019).10.1111/ijag.12974Search in Google Scholar

[27] F. Muñoz, R. J. Jiménez-Riobóo, R. Balda. J. Alloys Compd. 816, 152657 (2020).10.1016/j.jallcom.2019.152657Search in Google Scholar

[28] M. Cai, W. Mao, L. Calvez, J. Rocherullé, H. Ma, R. Lebullenger, X. Zhang, S. Xu, J. Zhang. Opt. Lett. 43, 5845 (2018), https://doi.org/10.1364/ol.43.005845.Search in Google Scholar

[29] Y. Wang, W. Zheng, Y. Lu, P. Li, S. Xu, J. Zhang. J. Lumin. 237, 118152 (2021), https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jlumin.2021.118152.Search in Google Scholar

© 2021 IUPAC & De Gruyter. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. For more information, please visit: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Preface

- 14th Conference on Solid State Chemistry

- Conference papers

- Strong emission at 1000 nm from Pr3+/Yb3+-codoped multicomponent tellurite glass

- Pressure assisted sintering of Al2O3–Y2O3 glass microspheres: sintering conditions, grain size, and mechanical properties of sintered ceramics

- Present state of 3D printing from glass

- Raman spectra of MCl-Ga2S3-GeS2 (M = Na, K, Rb) glasses

- The chemistry of melting oxynitride phosphate glasses

- Structure and magnetic properties of Bi-doped calcium aluminosilicate glass microspheres

- Special Topic Paper

- Synthesis design using mass related metrics, environmental metrics, and health metrics

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Preface

- 14th Conference on Solid State Chemistry

- Conference papers

- Strong emission at 1000 nm from Pr3+/Yb3+-codoped multicomponent tellurite glass

- Pressure assisted sintering of Al2O3–Y2O3 glass microspheres: sintering conditions, grain size, and mechanical properties of sintered ceramics

- Present state of 3D printing from glass

- Raman spectra of MCl-Ga2S3-GeS2 (M = Na, K, Rb) glasses

- The chemistry of melting oxynitride phosphate glasses

- Structure and magnetic properties of Bi-doped calcium aluminosilicate glass microspheres

- Special Topic Paper

- Synthesis design using mass related metrics, environmental metrics, and health metrics