Preparation of polylactide scaffolds for cancellous bone regeneration – preliminary investigation and optimization of the process

-

Monika Budnicka

, Paweł Ruśkowski

Abstract

Polylactide scaffolds were prepared for the cancellous bone regeneration by the phase inversion method with freeze-extraction variant. A preliminary investigation and the optimization of the process were performed. For the obtained scaffolds, regression equations determining the effect: PLLA concentration by weight in 1,4-dioxane; volume ratio of the porophore/PLLA solution in 1,4-dioxane; and implant-forming solution pouring temperature, on the open porosity and mass absorbability were determined. The conditions in which the obtained implants were characterized by the maximal absorbability with the open porosity greater than 90 % were obtained.

Introduction

Many bone defects do not heal spontaneously. These are the so called critical defects which require a surgical intervention. Conventionally, an autogenic transplantation (i.e. using a transplant derived from patient’s organism) is performed to commence the healing of the damaged bone tissue [1], [2]. Components, such as, osteoblasts, stem cells, the extracellular matrix, growth factors, included in the implants, have osteoinductive and osteoconductive properties. The autogenic transplant is commonly used; however, there is a risk of the transplantation site infection, haemorrhage or nerve damage [3]. A possible solution is to use bone substitutes, the implantation of which will promote the regeneration of the damages. Such substitutes (implants) are spatial scaffolds for cell cultures. Cells harvested from patient’s bone marrow are propagated and seeded on the scaffold. Cultured cells localize inside the three-dimensional implant structure composed of a network of interconnected pores. The crucial aspect which enables the formation of convenient environment for the growth of the new bone is the introduction of autogenic growth factors for the osteogenic cells into the scaffold, e.g. in a form of a platelet-rich plasma [4], [5]. In a modern approach to the bone defect treatment, the scaffold with cells and growth factors localized therein is subjected to implantation in the site of the damaged bone [6].

In the field of regenerative medicine, substitutes from resorbable polyesters, such as polylactide, polycaprolactone, have gained much interest [7]. The molecular weight of polyesters (included polylactide) affects final material properties. The higher molecular weight the greater crystallinity, time degradation, mechanical strength of the polymer. Therefore low molecular weight polylactide (Mw<10 000) is used in sustained drug release forms, e.g. microspheres, which degrade within days, weeks. High molecular weight polylactide found application in preparing of scaffolds, which should degrade in a few months to several years. As they are being gradually replaced by the host bone, there is no need to re-operate in order to remove the material. Because of polyester properties, such as elasticity, biocompatibility and low implant weight, they hold an important place among the polymers used in the bone regeneration [8]. The use of these polymers had positive results not only in animal preclinical studies but also in human clinical trials [9].

Bone substitutes should be characterized by high open porosity, i.e. the presence of interconnected pores [10]. The open porosity above 90% enables the nutrients to migrate freely into the scaffold and cell metabolites to migrate freely out of it. Pores should not be smaller than 100 μm. Yet, the optimal regeneration of the bone tissue is enabled by the pores of 200–350 μm [11]. The size of pores should be diversified which means that within the scaffold structure there should be both small (microporosity) and large pores (macroporosity) [12]. One should remember that high porosity weakens the mechanical properties of the implant. The mechanical properties of the bone are different for cancellous and compact bone. The high porosity polyester implant has suitable mechanical strength – similar to that of the cancellous bone, which has the Young’s modulus of 0.1–2 GPa and the compressive strength of 2–20 MPa. For the compact bone, the Young’s modulus is in the range of 15–20 GPa and compressive strength is 100–200 MPa, so additives improving the polymer mechanical properties should be used [13].

The aim of the study was to obtain polylactide cancellous bone implants with an internal morphology meeting the requirements for the regeneration of such bone. The obtained implants should have a high open porosity (90–100%) and maximal mass absorbability. The maximization of mass absorbability is important due to the possibility of inserting a greater volume of the platelet-rich plasma into the scaffold.

The effects of the polylactide concentration in dioxane, the porophore content and the implant-forming solution pouring temperature on the morphology of the obtained scaffolds were evaluated. Subsequently, using mathematical methods of experiment planning [14], [15], [16], [17], the process for preparation of polylactide cancellous bone implants was optimized to obtain a scaffold with the maximal mass absorbability at the open porosity of more than 90%.

Results and discussion

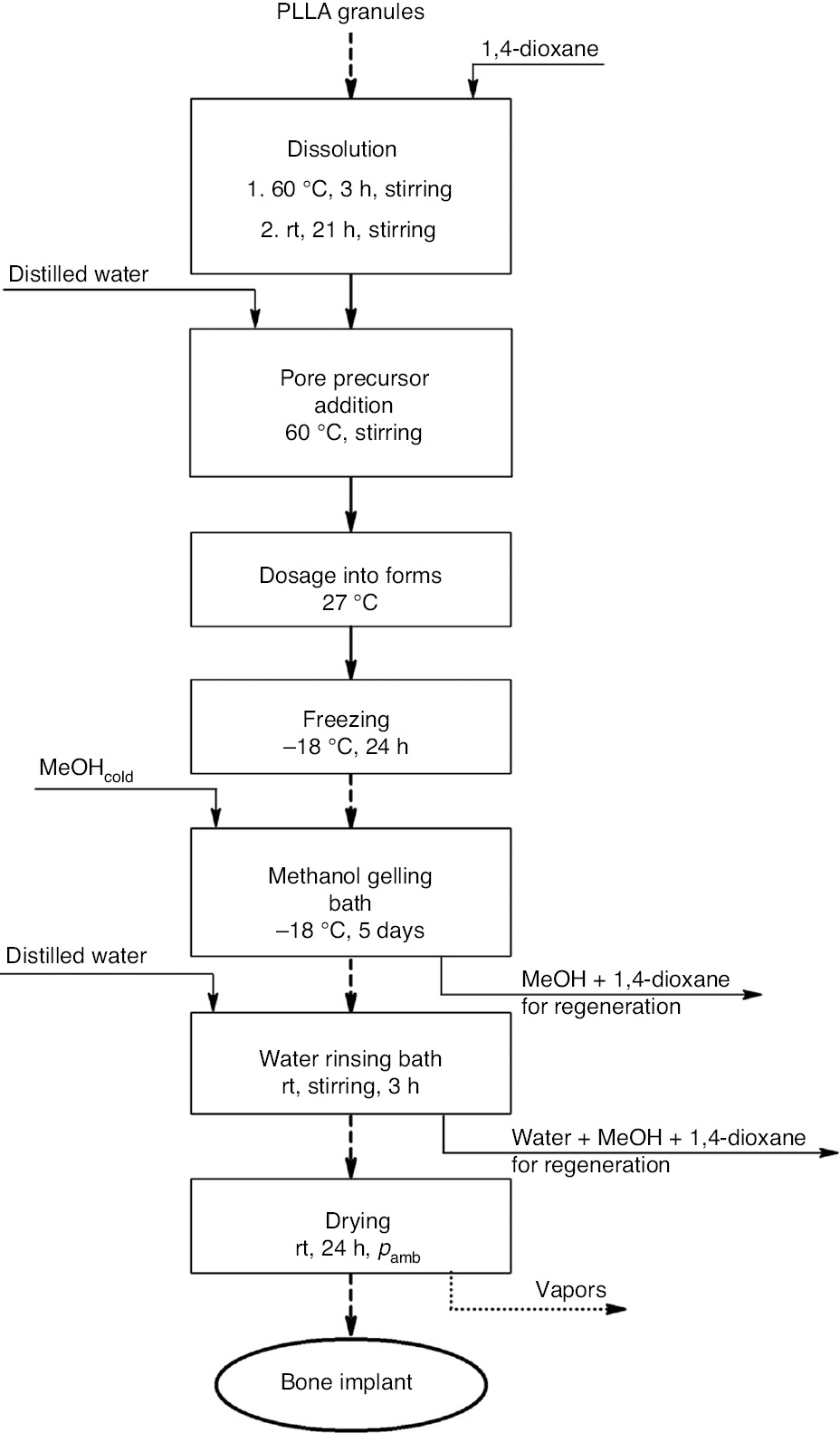

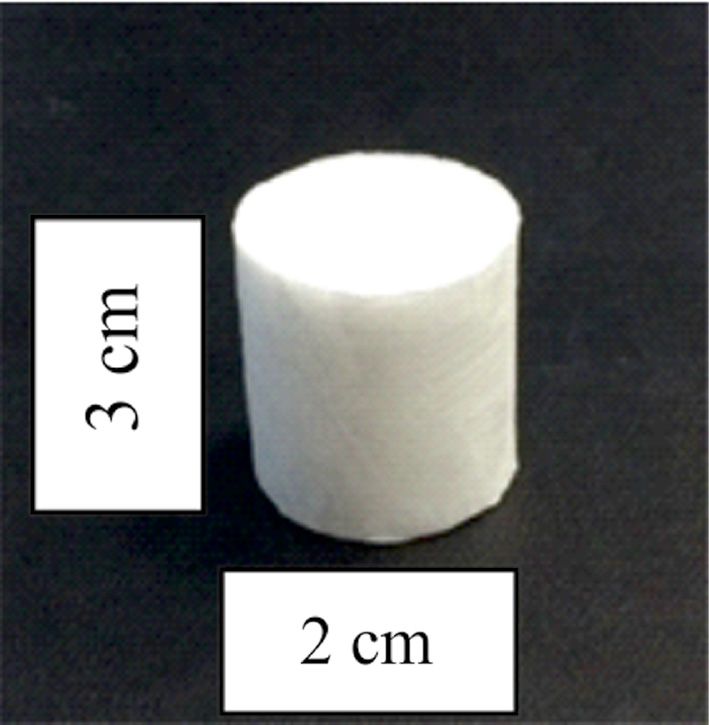

Porous poly-L-lactide (PLLA) implants were obtained (Scheme 1). First, a PLLA solution in 1,4-dioxane was prepared. The suitable volume of the porophore (water) was added in portions. The implant-forming mixture was dosed into the forms at a specified temperature. Moulded solution was frozen and subjected to the gelling bath 1 (in methanol, at −18°C). The resulting scaffold was washed in the gelling bath 2 (in water, at ambient temperature). The finished implant was air dried. An exemplary implant is presented in Fig. 1.

Block diagram of the bone implant manufacturing at the laboratory scale.

Polylactide bone implant.

Preliminary investigation

The preliminary investigation of the poly-L-lactide bone implant preparation was performed in order to evaluate the effect of: PLLA concentration by weight in 1,4-dioxane; porophore (water) addition; and implant-forming solution pouring temperature, on the size and distribution of pores in the resulting samples. Morphology of the prepared implant was assessed by the scanning electron microscopy (SEM). The conditions for preparing bone implants in the preliminary investigation are presented in Table 1.

Preliminary investigation of the poly-L-lactide bone implant preparation.

| Label | PLLA concentration by weight in 1,4-dioxane (wt%) | Volume ratio of porophore (water)/PLLA solution in 1,4-dioxane | Solution pouring temperature (°C) |

|---|---|---|---|

| BUDTA1 | 3 | 0 | 27 |

| BUDTA2 | 5 | 0 | 27 |

| BUDTA3 | 7 | 0 | 27 |

| BUDTA4 | 3 | 0.08 | 27 |

| BUDTA5 | 5 | 0.08 | 27 |

| BUDTA6 | 5 | 0.03 | 27 |

| BUDTA7 | 5 | 0.1 | 27 |

| BUDTA8 | 3 | 0.08 | 27 |

| BUDTA9 | 3 | 0.08 | 47 |

| BUDTA10 | 7 | 0.08 | 27 |

| BUDTA11 | 7 | 0.08 | 47 |

Effect of PLLA concentration by weight in dioxane

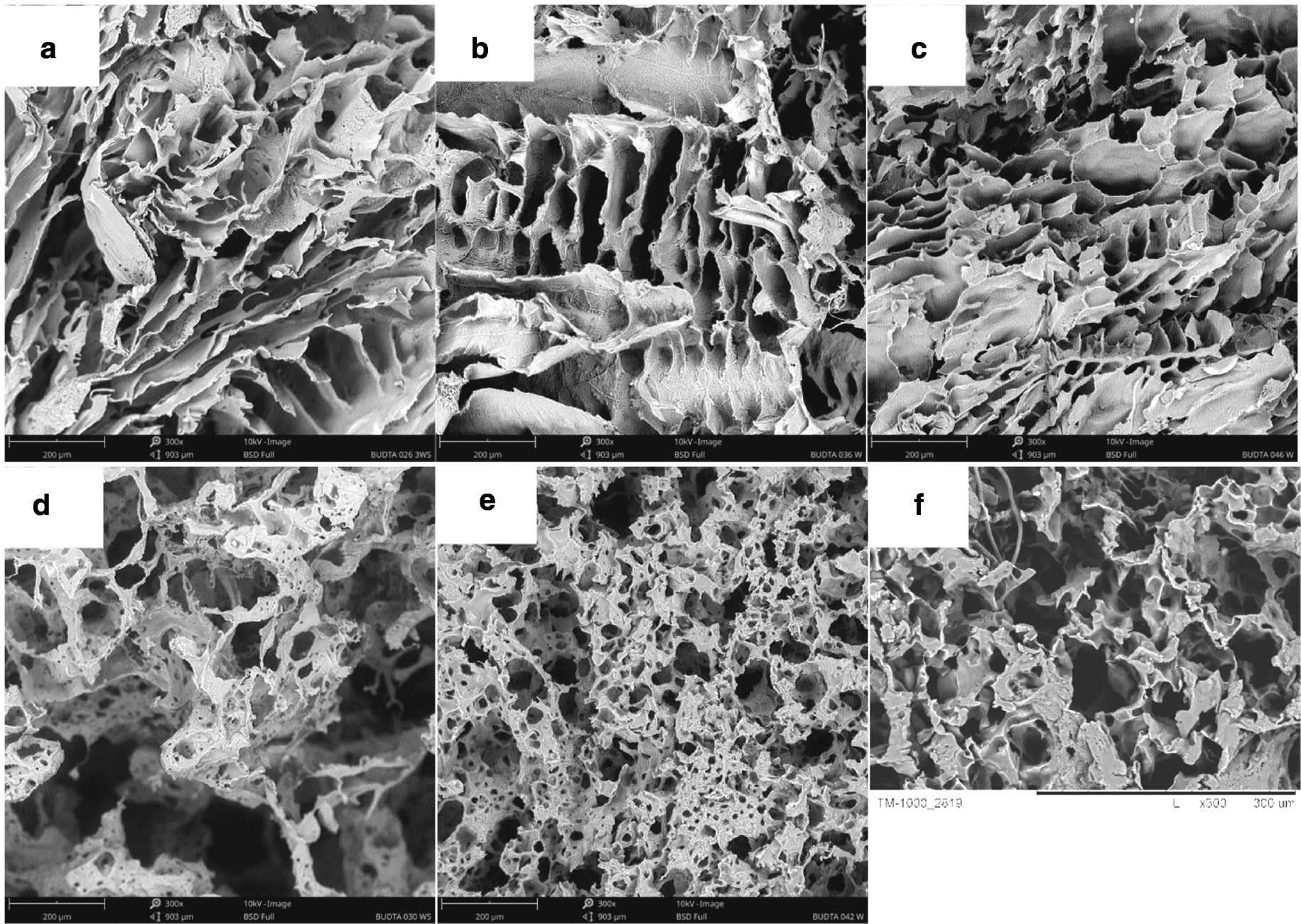

The poly-L-lactide bone implants were produced under different process conditions. The differences in the scaffold internal morphology depending on the PLLA concentration by weight in 1,4-dioxane (3.5 and 7.0 wt%) and the volume ratio of porophore/PLLA solution in 1,4-dioxane (0 and 0.08), at constant pouring temperature (27°C), were presented in Fig. 2.

SEM images of poly-L-lactide bone implants prepared at pouring temperature of 27°C: PLLA concentration by weight in 1,4-dioxane: 3 wt% (a, d), 5 wt% (b, e), 7 wt% (c, f). Porophore/PLLA solution in 1,4-dioxane volume ratio: 0 (a–c), 0.08 (d–f). 300× magnification.

Without the porophore (Fig. 2a–c), with the increasing PLLA concentration in 1,4-dioxane, there is an increase in the number of smaller pores in the scaffold. For the PLLA concentration of 3 wt%, the pore size range is 110–250 μm, and for the PLLA concentration of 7 wt%, it is 50–270 μm. For implants produced with the porophore addition (Fig. 2d–f), there is no unequivocal relation. In the scaffold with the highest PLLA concentration (Fig. 2f), there are a few small pores and thicker pore walls visible. Most of the pores exceed 100 μm. Bone implants presented in Fig. 2d–f have the most suitable structure for seeding the cells. The morphology with diversified pore sizes (micro- and macroporosity) and the structure with connected pores are observed which favour regeneration of the bone tissue.

Effect of the porophore addition

The poly-L-lactide scaffolds were produced without or with a varying amount of the porophore (water) at the constant PLLA concentration in 1,4-dioxane (5 wt%) and constant pouring temperature (27°C). The internal morphology differences related to the changes of the porophore/PLLA solution in 1,4-dioxane volume ratio (0, 0.03, 0.08, 0.1) are presented in Fig. 3.

SEM images of poly-L-lactide bone implants prepared under following conditions: 5 wt% PLLA solution in 1,4-dioxane, pouring temperature: 27°C, porophore/PLLA solution in 1,4-dioxane volume ratio: 0 (a), 0.03 (b), 0.08 (c), 0.1 (d). 300× magnification.

When the porophore is absent (Fig. 3a), the scaffold structure is characterised by large elongated pores exceeding 300 μm (ladder-like pore arrangement). There are virtually no smaller pores. The porophore addition causes the formation of both smaller and larger connected spherical pores of a size that does not exceed 200 μm. For 0.03 and 0.08 ratio of porophore/PLLA solution (Fig. 3b, c, respectively), the pore size is diversified. For the largest porophore addition, 0.1 (Fig. 3d), the walls of the pores are thickened and the number of smaller pores decreases markedly. Bone implants presented in Fig. 2b and c have the most suitable structure for seeding the cells.

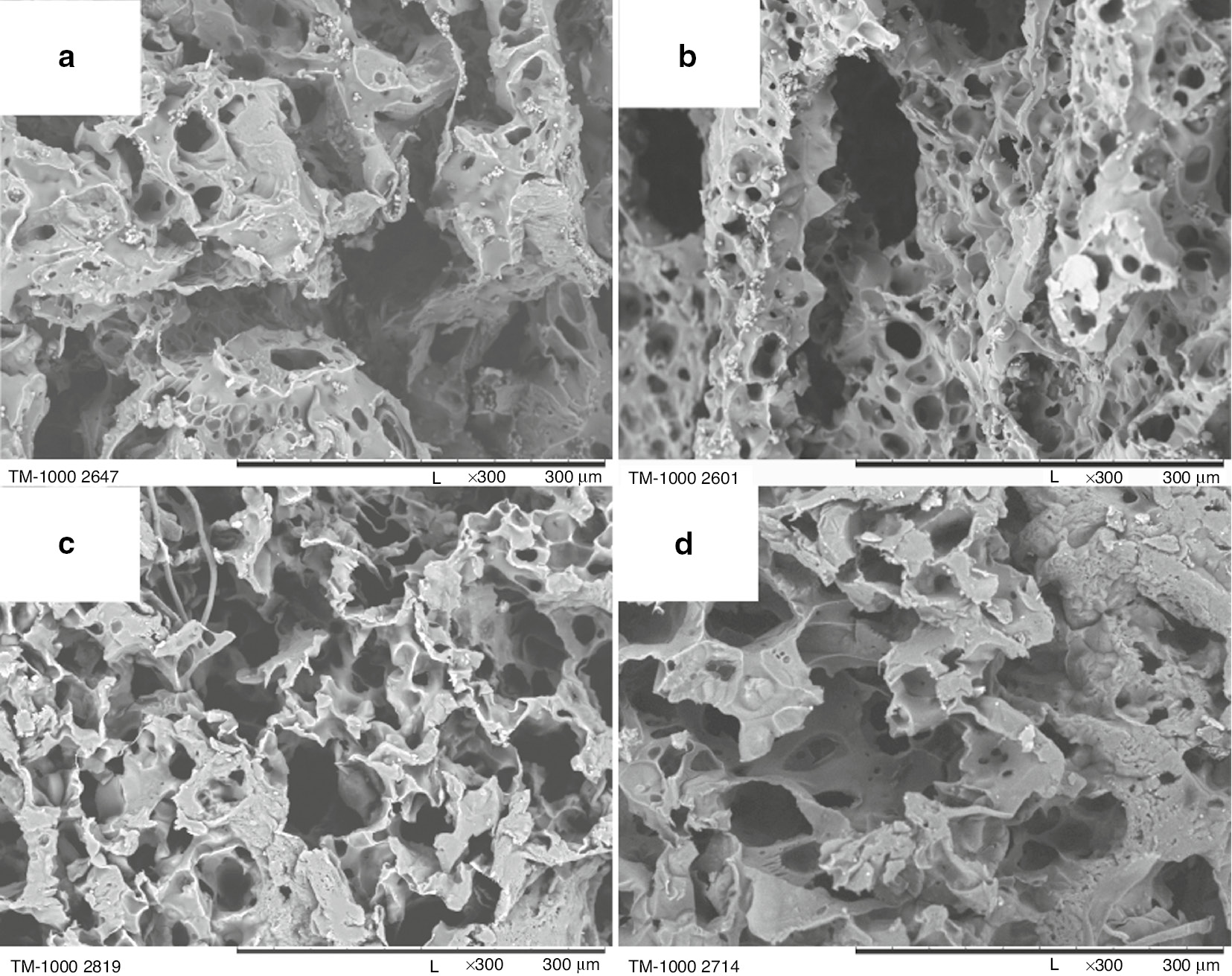

Effect of the solution pouring temperature

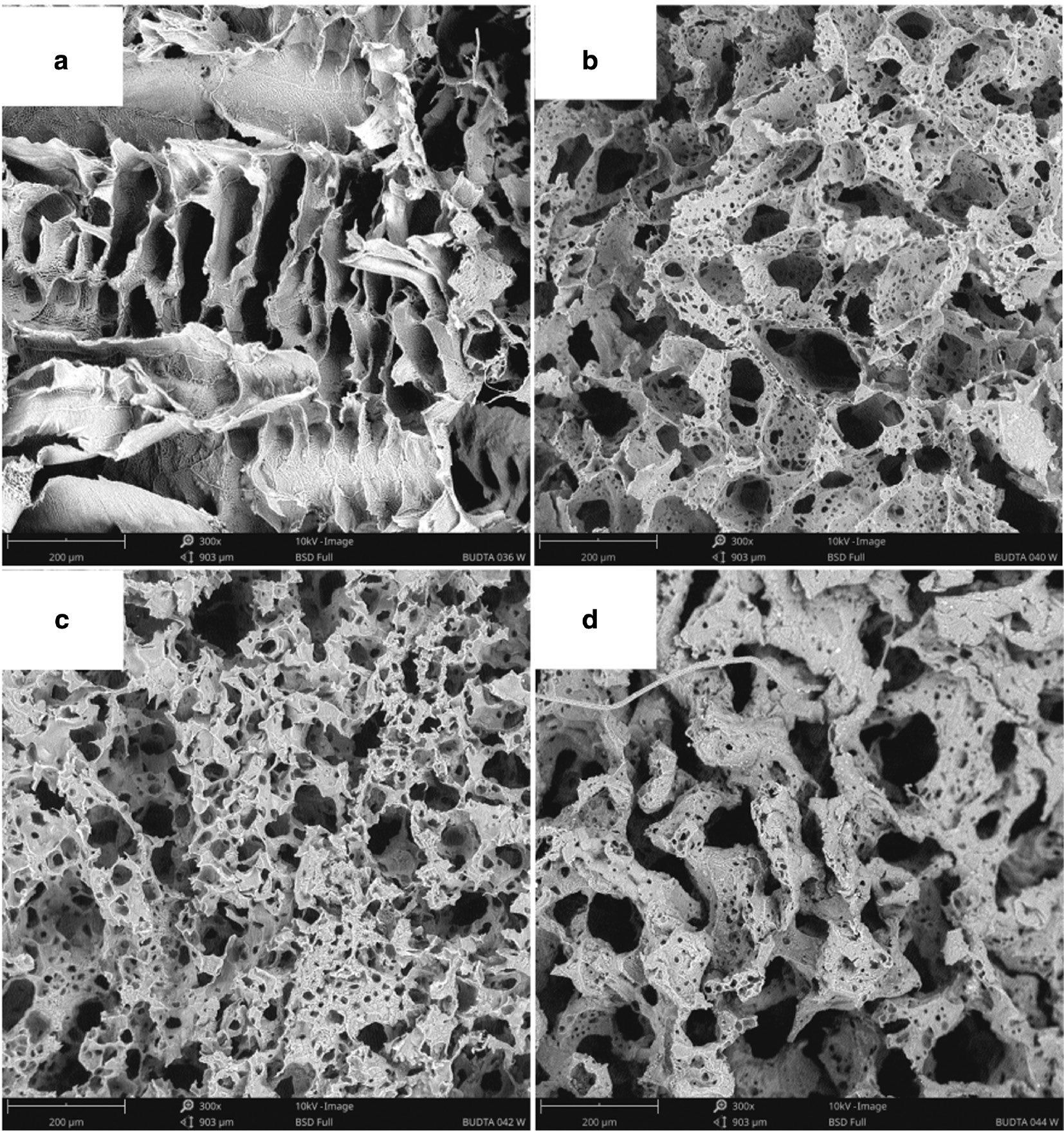

The poly-L-lactide scaffolds were prepared by pouring the implant-forming solution at different temperatures. The differences in the implant’s internal morphology related to the solution pouring temperature (27°C and 47°C), at the constant porophore/PLLA solution in 1,4-dioxane volume ratio of 0.08, were shown in Fig. 4 for the PLLA concentrations in 1,4-dioxane of 3 wt% and 7 wt%.

SEM images of poly-L-lactide bone implants prepared under following conditions: PLLA concentration by weight in 1,4-dioxane: 3 wt% (a, b), 7 wt% (c, d); porophore/ PLLA solution in 1,4-dioxane volume ratio: 0.08; pouring temperature: 27°C (a, c), 47°C (b, d). 300× magnification.

For the scaffolds prepared from 3 wt% PLLA solution in 1,4-dioxane, the increase in the pouring temperature results in the formation of a greater number of micropores (Fig. 4a, b). The macropore size does not change. The implants prepared from 7 wt% PLLA solution in 1,4-dioxane do not exhibit any significant differences in the morphology depending on the pouring temperature (Fig. 4c, d). All obtained implants have a structure suitable for seeding the cells.

Summary of the preliminary investigation

The poly-L-lactide scaffolds with the morphology meeting the requirements for the cancellous bone regeneration were prepared. The structures with connected open pores of diversified size (100–300 μm) were obtained.

Based on the preliminary investigation, it was found that the PLLA concentration in dioxane, porophore addition, and implant-forming solution pouring temperature all influence the internal morphology of the produced bone implants. In order to quantify the exact relations, it was decided to investigate the effect of these variables on the mass absorbability and the open porosity of the resulting samples. The open porosity and mass absorbability of the obtained bone implants were tested with a hydrostatic method using isopropanol as a solvent. A detailed description of the study is shown in the experimental section.

Optimization

The effect of the PLLA concentration by weight in 1,4-dioxane (x1), the porophore (water) to PLLA solution in 1,4-dioxane volume ratio (x2) and the solution pouring temperature (x3) on the open porosity (y1) and the mass absorbability (y2) of the obtained implants was investigated. The volume of PLLA solution in 1,4-dioxane was constant. The optimization criterion was the mass absorbability maximization with the open porosity of not less than 90%. The optimization was performed based on the 23 factorial design with interaction effects. Input and output variables are shown in Table 2.

Identification of input and output variables with codification of input variables.

| Variable | Natural variable | Unit | Coded variables | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| −1 | 0 | +1 | |||

| Input | |||||

| x1 | PLLA concentration by weight/1,4-dioxane | % | 3 | 5 | 7 |

| x2 | Volume ratio of porophore/PLLA solution in 1,4-dioxane | – | 0.030 | 0.055 | 0.080 |

| x3 | Solution pouring temperature | °C | 27 | 37 | 47 |

| Output | |||||

| y1 | Open porosity | % | >90% | ||

| y2 | Mass absorbability | % | Max. | ||

An 11-run design was used, which consisted of a 2-level factorial design, 23 (8 runs with three input variables in all combinations of +1 and −1 levels) and three replicates for the centre of the design (3 runs with all three variables at 0) [18]. All other variables were constant (standard conditions). The experiments were performed in a random order, and both of the response variables, yi, were measured for each experiment. Table 3 shows the design matrix along with the results.

The 23 factorial design: experimental matrixa and resultsb.

| Trial no. | Constant | Coded variables | Porosity (%) | Absorbability (%) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| x1 | x2 | x3 | y1 | ŷ1 | y2 | ŷ2 | ||

| 1 | +1 | −1 | −1 | −1 | 96.3 | 96.4 | 1510 | 1510 |

| 2 | +1 | +1 | −1 | −1 | 89.8 | 91.1 | 569 | 628 |

| 3 | +1 | −1 | +1 | −1 | 96.2 | 96.4 | 1450 | 1510 |

| 4 | +1 | +1 | +1 | −1 | 90.8 | 91.1 | 636 | 635 |

| 5 | +1 | −1 | −1 | +1 | 96.1 | 96.4 | 1410 | 1430 |

| 6 | +1 | +1 | −1 | +1 | 91.4 | 91.1 | 631 | 552 |

| 7 | +1 | −1 | +1 | +1 | 96.8 | 96.4 | 1670 | 1590 |

| 8 | +1 | +1 | +1 | +1 | 92.3 | 91.1 | 692 | 712 |

| 9 | +1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 94.3 | 93.7 | 951 | 1070 |

| 10 | +1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 93.5 | 93.7 | 903 | 1070 |

| 11 | +1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 94.1 | 93.7 | 939 | 1070 |

aStandard conditions: all experiments were performed using the same raw materials and volume of PLLA solution in 1,4-dioxane. bAll ŷi were calculated using linear model.

In order to shorten the discussion, the statistical analysis details are not presented in this paper. Here, we present the linear models (without insignificant coefficients) and the most important diagrams only. Coefficients calculated on the basis of 2-level factorial design are independent of each other (regression equation is orthogonal). A new fitting procedure is unnecessary after insignificant coefficients removal from the models.

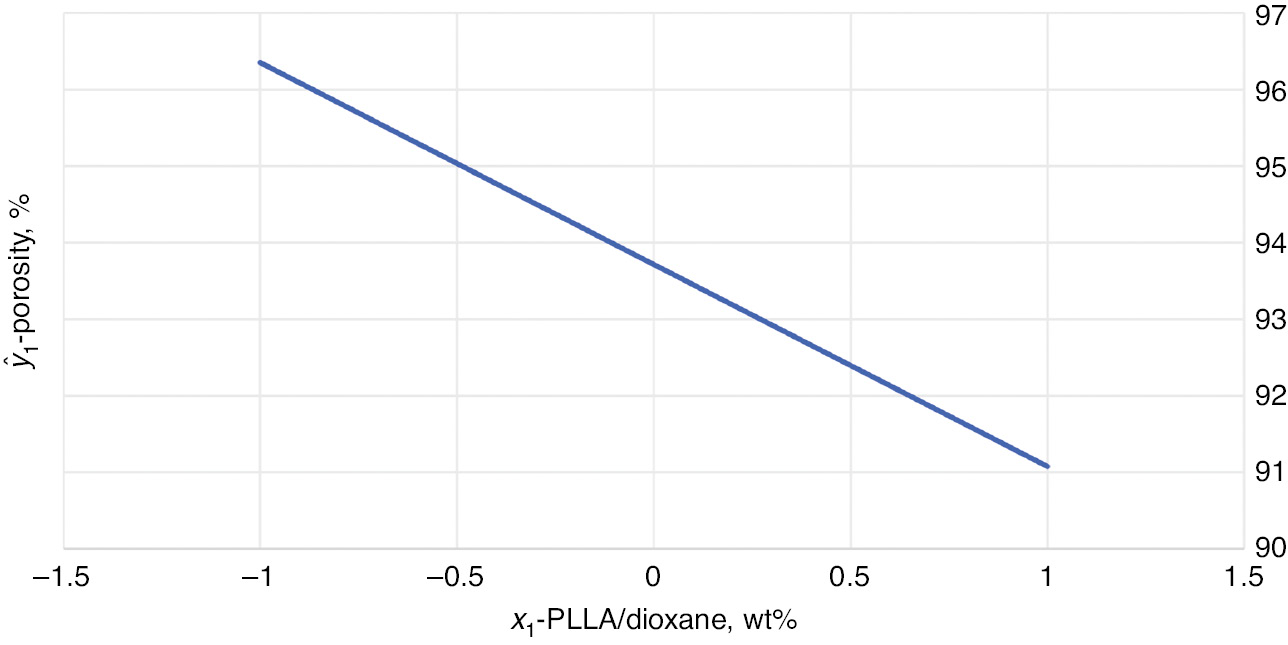

Porosity, ŷ1 (%)

The diagram of the relation between the implant porosity, ŷ1, and PLLA concentration by weight in dioxane, x1, is shown in Fig. 5.

Dependence of the open porosity (ŷ1) in function of the PLLA concentration by weight in dioxane (x1).

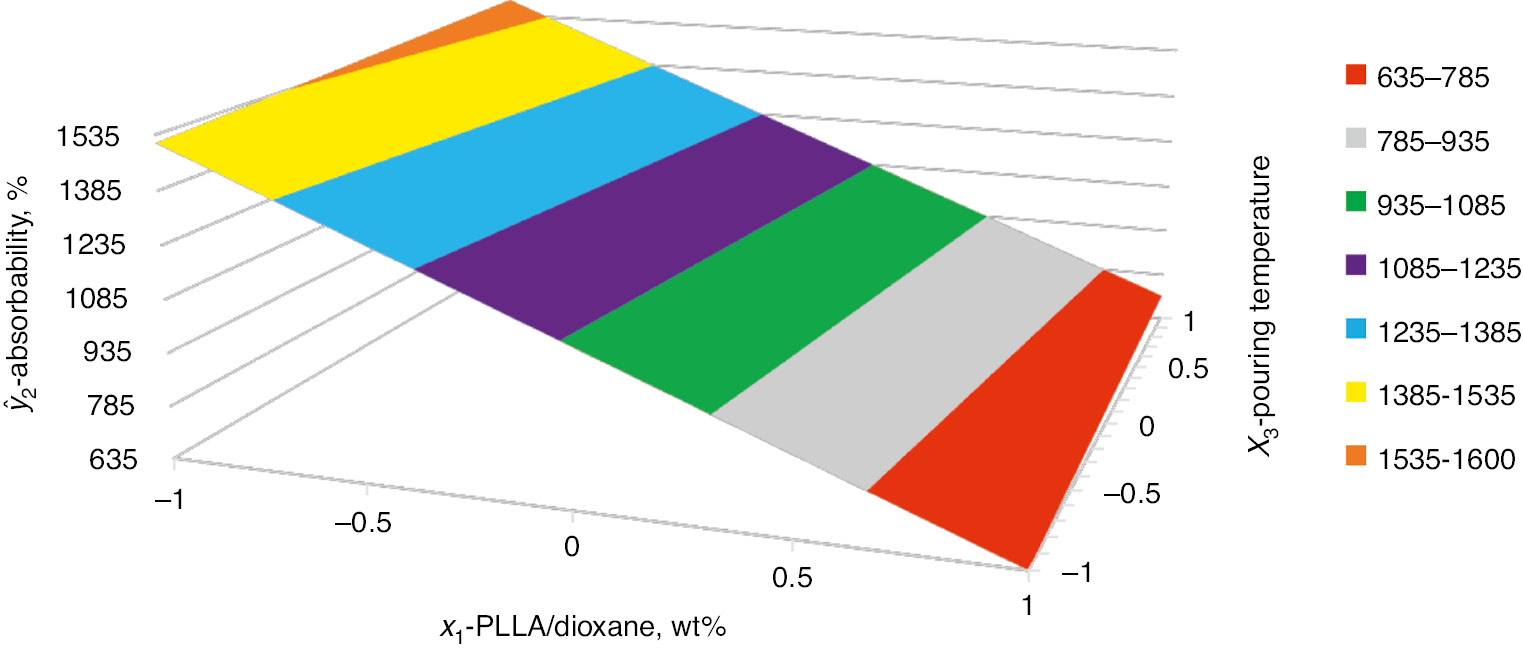

Absorbability, ŷ2, (%)

The diagram of the relation between the mass absorbability, ŷ2, and PLLA concentration by weight in dioxane, x1, and the solution pouring temperature, x3, at the constant volume ratio of water to PLLA/1,4-dioxane solution, x2=1, is shown in Fig. 6.

Dependence of the mass absorbability (ŷ2) on the PLLA concentration by weight in dioxane (x1) and the solution pouring temperature (x3). The constant volume ratio of the porophore to PLLA solution in 1,4-dioxane (x2=1).

Summary of the optimization

The effect of: PLLA concentration by weight in dioxane (x1); volume ratio of water to PLLA solution in 1,4-dioxane (x2); and solution pouring temperature (x3), on the open porosity of the obtained implants (y1) and the mass absorbability of implants (y2) was investigated. Using the estimated function, it was found that, within the design limits, it is the PLLA concentration by weight in dioxane (x1) that has the strongest influence on the implant open porosity. This is the only factor in the equation. The implant open porosity decreases with the increase of the PLLA concentration by weight in dioxane. It means that, in the experiment, the smallest PLLA concentration by weight in dioxane (x1=−1) should be applied to obtain the maximal open porosity. The x2 and x3 variables do not affect the implant open porosity.

Based on the estimated equation, the mass absorbability decreases along with x1 factor and increases along with x2 factor and with the interaction effect of x2·x3. The largest influence on the mass absorbability has the PLLA concentration by weight in dioxane, x1. The solution pouring temperature (x3) has an influence only through the interaction with x2.

It should be noted that this optimization is appropriate only within the previously established range of the variables and it should not be extrapolated beyond that range.

The maximization of the mass absorbability of implants with an open porosity of not less than 90%, leads to the following optimal conditions:

minimal PLLA concentration by weight in dioxane: 3 wt% (x1=−1)

volume ratio of water to PLLA/1,4-dioxane solution: 0.08 (x2=1)

maximal temperature: 47°C (x3=1)

The results are as follows: ŷ1=96.4%, ŷ2=1589%. An experiment no. 7, which was performed under the same conditions, was accepted as a confirmatory experiment. It had the following results: y1=96.8%, y2=1670%.

Conclusions

A method for the preparation of the poly-L-lactide bone implants was developed which enables the preparation of implants with high porosity and connected pores structure.

The process was successfully optimized with the aid of DOE. After carrying out a 23 factorial design, the mathematical models describing the influence of input variables: PLLA concentration by weight in 1,4-dioxane; volume ratio of water to PLLA solution in dioxane; and solution pouring temperature, on the open porosity and the mass absorbability of obtained implants, were calculated. Both regression equations are adequate, which is confirmed by the fact that the differences between the results and the calculated values are small. The first model enables the control over polylactide implant open porosity. The suitable open porosity (over 90%) enables the nutrients to migrate into the scaffold and the cell metabolites to migrate out of it. The second model enables the control over implant mass absorbability, the maximization of which ensures the insertion of the largest possible volume of the platelet-rich plasma into the scaffold. The scaffold design with optimal properties including open porosity and mass absorbability provides an implant which meets the requirements for the cancellous bone regeneration.

Under optimal conditions: PLLA concentration of 3 wt%, volume ratio of water to PLLA solution in 1,4-dioxane of 0.08, the solution temperature of 47°C, the poly-L-lactide bone implant having the porosity of 96.8% and mass absorbability of 1670% was obtained confirming that the calculated equations describe the entire process very well.

Experimental section

Materials

Commercially available poly-L-lactide (PLLA) (Mw=86 000 g/mol, D=1.91), 1,4-dioxane, methanol, 2-propanol were used without additional preparation. Distilled water was prepared in-house.

Preparation of solutions

The poly-L-lactide solutions in dioxane having an appropriate concentration by weight (3 wt%, 5 wt%, 7 wt%) were prepared. PLLA was dissolved in dioxane for 3 h at 60°C, and then at ambient temperature for at least 21 h. In both temperatures the solutions were stirred with a magnetic stirrer. To the PLA solution in dioxane heated to a temperature of 60°C, with constant stirring, water (porophore) was added in a suitable volume ratio to the PLA solution in dioxane (0.030, 0.055, 0.080). The porophore was added in portions of 0.5 mL each, and before adding the next portion the solution was allowed to clarify. Then, the solutions were cooled to the appropriate temperature (27°C, 37°C, and 47°C).

Preparation of implants

The implants were prepared by the phase inversion method with freeze-extraction variant. The prepared solutions were poured into the polyethylene forms at the suitable temperature (27°C, 37°C, 47°C), then the forms were cooled at temperature of −18°C for 24 h. The frozen solutions were removed from the forms and extracted in a methanol bath (300 mL) at −18°C for 5 days, without stirring. The resulting implants were washed in a water bath (400 mL) at ambient temperature for 2.5 h with stirring, then air dried for 24 h.

Analytical methods

Scaffold morphology

The scaffold morphology was investigated with the scanning electron microscopy (SEM). Before testing, the samples were immersed in ethanol for 20 min and then broken in liquid nitrogen. After drying, fragments of them were cut off with a scalpel so that the surface investigated under the microscope was the one resulting from the breaking in liquid nitrogen. The BUDTA 1–7 samples were investigated with the Phenom ProX apparatus and BUDTA 8–11 with a Hitachi TM1000 apparatus, after applying a 7–10 nm gold layer on them using K550X Sputter Coater. All samples were investigated at a 300× magnification using an accelerating voltage of 15 kV. In the SEM images, the inside of the implant was observed from the vertical section of the sample.

Implant open porosity and mass absorbability

The implants were weighed using Mettler Toledo XS 104 scales. Dry scaffolds were air weighted (ms). After the isopropanol impregnation (vac, 30 min), the scaffolds were weighted in isopropanol (mww) and finally the scaffolds impregnated in isopropanol were air weighted (mw). The implant open porosity (Po) and mass absorbability (Nm) were determined according to the formulae:

Article note

A collection of invited papers based on presentations at the 1st International Conference on Chemistry for Beauty and Health, 13–16 June 2018, Nicolas Copernicus University in Torun, Poland.

Author contributions: The manuscript was written with contribution of all authors. All authors have given approval for the final version of the manuscript.

Funding sources: Financial support obtained from Warsaw University of Technology, Faculty of Chemistry, is gratefully acknowledged.

References

[1] V. M. Goldberg. Bone implant grafting: natural history of autografts and allografts, in Bone Implant Grafting, J. Older (Ed.), pp. 9–12, Springer-Verlag London, London (1992).10.1007/978-1-4471-1934-0_2Suche in Google Scholar

[2] W. Y. Ip, S. Gogolewski. Macromol. Symp.253, 139 (2007).10.1002/masy.200750721Suche in Google Scholar

[3] J. A. Goulet, L. E. Senunas, G. L. DeSilva, M. L. Greenfield. Clin. Orthop. Relat. Res.339, 76 (1997).10.1097/00003086-199706000-00011Suche in Google Scholar

[4] S. P. Avera, W. A. Stampley, B. S. McAllister. Int. J. Oral Maxillofac. Implants12, 88 (1997).Suche in Google Scholar

[5] J. K. Blanco, A. Alcanso, M. Sanz. Clin. Oral Implants Res.16, 294 (2005).10.1111/j.1600-0501.2005.01106.xSuche in Google Scholar

[6] S. Sharma, D. Srivastava, S. Grover, V. Sharma. J. Clin. Diagn. Res.8, 309 (2014).10.1155/2014/861942Suche in Google Scholar

[7] M. Budnicka, A. Gadomska-Gajadhur, P. Ruśkowski. Polimery63, 3 (2018).10.14314/polimery.2018.1.1Suche in Google Scholar

[8] S. Słomkowski. Macromol. Symp.253, 47 (2007).10.1002/masy.200750706Suche in Google Scholar

[9] K. Ficek, J. Filipek, P. Wojciechowski, K. Kopec, E. Stodolak-Zych, S. A. Blazewicz. J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Med. 27, 33 (2016). Published online: 24 December 2015. Doi 10.1007/s10856-015-5647–4.10.1007/s10856-015-5647–4Suche in Google Scholar

[10] J. R. Woodard, A. J. Hilldore, S. K. Lan, C. J. Park, A. W. Morgan, J. A. Eurell, S. G. Clark, M. B. Wheeler, R. D. Jamison, A. J. Wagoner Johnson. Biomaterials28, 45 (2007).10.1016/j.biomaterials.2006.08.021Suche in Google Scholar

[11] Y. Ikada, H. Tsuji. Macromol. Rapid Commun.21, 117 (2000).10.1002/(SICI)1521-3927(20000201)21:3<117::AID-MARC117>3.0.CO;2-XSuche in Google Scholar

[12] D. F. Williams. Biomaterials29, 2941 (2008).10.1016/j.biomaterials.2008.04.023Suche in Google Scholar

[13] M. J. Olszta, X. Cheng, S. S. Jee, R. Kumar, Y. Y. Kim, M. J. Kaufman, E. P. Douglas, L. B. Gower. Mater. Sci. Eng. R: Rep.58, 77 (2007).10.1016/j.mser.2007.05.001Suche in Google Scholar

[14] H. Hajmowicz, J. Wisialski, L. Synoradzki. Org. Process Res. Dev.15, 427 (2011).10.1021/op100315kSuche in Google Scholar

[15] L. Synoradzki, D. Jańczewski, M. Włostowski. Org. Process Res. Dev.9, 18 (2005).10.1021/op030029ySuche in Google Scholar

[16] L. Synoradzki, T. Rowicki, M. Włostowski. Org. Process Res. Dev.10, 103 (2006).10.1021/op050186sSuche in Google Scholar

[17] A. Kruk, A. Gadomska-Gajadhur, P. Ruśkowski, A. Przybysz, V. Bijak, L. Synoradzki. Przem. Chem.95, 766 (2016).Suche in Google Scholar

[18] See for example: (a) P. Adler, E. V. Markowa, V. Granovsky. The Design of Experiments to Find Optimal Conditions a Programmed Introduction to the Design of Experiments, Mir Publishers, Moscow (1975). (b) S. Ł. Achnazarowa, W. W. Kafarow. Optimization of Experiments in Chemistry and in Chemical Technology, WNT, Warszawa (1982). (c) E. Morgan. Chemometrics: Experimental Design, Wiley, Chichester (1991). (d) R. G. Brereton. Applied Chemometrics for Scientists, Wiley, Chichester (2007). (e) D. C. Montgomery. Design and Analysis of Experiments, 7th ed., Wiley, New York (2009). (f) D. Jańczewski, C. Różycki, L. Synoradzki. Process Designing – DOE, OWPW, Warszawa (2010).Suche in Google Scholar

© 2019 IUPAC & De Gruyter. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. For more information, please visit: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Frontmatter

- In this issue

- Preface

- ICS-29: The 29th International Carbohydrate Symposium

- Conference papers

- 1-(2-Aminoethyl)-3-methyl-1H-imidazol-3-ium tetrafluoroborate: synthesis and application in carbohydrate analysis

- One-pot oligosaccharide synthesis: latent-active method of glycosylations and radical halogenation activation of allyl glycosides

- Nanoparticles for the multivalent presentation of a TnThr mimetic and as tool for solid state NMR coating investigation

- Preface

- Papers from the 1st International Conference on Chemistry for Beauty and Health (Beauty-Torun’2018)

- Conference papers

- In vivo electrical impedance measurement in human skin assessment

- Formulation and characterization of some oil in water cosmetic emulsions based on collagen hydrolysate and vegetable oils mixtures

- Preparation of polylactide scaffolds for cancellous bone regeneration – preliminary investigation and optimization of the process

- Effect of molecular weight of polyvinylpyrrolidone on the skin irritation potential and properties of body wash cosmetics in the coacervate form

- Ortho-substituted azobenzene: shedding light on new benefits

- Erratum

- Erratum to: Efforts to improve Japanese women’s status in STEM fields

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Frontmatter

- In this issue

- Preface

- ICS-29: The 29th International Carbohydrate Symposium

- Conference papers

- 1-(2-Aminoethyl)-3-methyl-1H-imidazol-3-ium tetrafluoroborate: synthesis and application in carbohydrate analysis

- One-pot oligosaccharide synthesis: latent-active method of glycosylations and radical halogenation activation of allyl glycosides

- Nanoparticles for the multivalent presentation of a TnThr mimetic and as tool for solid state NMR coating investigation

- Preface

- Papers from the 1st International Conference on Chemistry for Beauty and Health (Beauty-Torun’2018)

- Conference papers

- In vivo electrical impedance measurement in human skin assessment

- Formulation and characterization of some oil in water cosmetic emulsions based on collagen hydrolysate and vegetable oils mixtures

- Preparation of polylactide scaffolds for cancellous bone regeneration – preliminary investigation and optimization of the process

- Effect of molecular weight of polyvinylpyrrolidone on the skin irritation potential and properties of body wash cosmetics in the coacervate form

- Ortho-substituted azobenzene: shedding light on new benefits

- Erratum

- Erratum to: Efforts to improve Japanese women’s status in STEM fields