Abstract

Body wash cosmetics are among the most common groups of cosmetics used by consumers. Faced with strong competition in the marketplace, cosmetic manufacturers search for innovative solutions both in terms of product composition and form. An example of an innovative technology which can be used in the production of body wash cosmetics is the process of coacervation which yields a concentrated body wash product. Another important aspect which needs to be considered in the formulation of body wash cosmetics is their safety of use. It is crucial to ensure that such cosmetic products do not induce skin irritations. At present, the most widespread method of reducing the skin irritation potential of cosmetic products is the use of surfactant mixtures. The study is an attempt to evaluate the effect of using polyvinylpyrrolidone in the formulations of model body wash cosmetics in the coacervate form on the skin irritation potential and basic quality determinants of body wash products. Polyvinylpyrrolidone was found to contribute to a significant reduction in the irritant effect, and the skin irritation potential decreased in proportion to increasing molecular mass of the polymer. The application of polyvinylpyrrolidone with the different molecular weight also has an impact on improving the foaming properties of model body wash cosmetics and the stability of foam they produce.

Introduction

Body wash cosmetics represent the largest group of cosmetic products both in terms of quantity and frequency of use by consumers. The skin of most people comes into contact with a range of body wash cosmetics including soap, liquid soap, body wash gel, hair shampoo or bath liquid, several times a day. The main task of body wash cosmetics is to remove soiling, both of internal and external origin, from the surface of the skin or hair. This goal can be achieved with the use of surfactants. However, surfactants are associated with side effects, the most important of which is the potential to induce skin irritation. From the physicochemical viewpoint, body wash cosmetics are generally 10–30% aqueous solutions of surface active agents (surfactants) enriched with a variety of substances to achieve the desired viscosity (electrolytes, polymers), product preservation (preservatives), fragrance, color, nourishing and moisturizing properties, etc. [1], [2], [3], [4], [5], [6], [7].

The method and technology employed by manufacturers in the production of cosmetics has been largely the same for many years, without major modifications. The usual procedure involves the preparation of aqueous surfactant solutions and additives, and thickening the system with electrolytes or polymers. However, as the cosmetic market is very competitive, cosmetic manufacturers are constantly on the lookout for innovative solutions not only in terms of ingredients but also product form and production technologies.

Limited available studies demonstrate that an example of such innovation may be the production of washing cosmetics based on the process of simple coacervation [8], [9], [10], [11].

Research has found that coacervate, i.e. the product of coacervation process, can be a novel form of a washing agent which possesses functional properties similar to traditional products but, unlike them, constitutes a concentrated form. Previous studies show that the process of coacervation makes it possible to obtain, for example, hand dishwashing liquids with very good functional properties which, compared to traditional products, are safer for the skin and have a lower irritant potential. The addition of water increases their viscosity. There are no studies using the process of coacervation in the production of cosmetic products [10], [11], [12], [13], [14].

Coacervation in surfactant systems is induced through the use of electrolytes. Following its addition, micelles formed in surfactant solutions undergo transformations from spherical to cylindrical micelles, via bilayered lamellar structures to lamellar vesicles created by spherically arranged lamellae (so-called onion structures). Their formation results in the separation of the solution into two phases: surfactants – rich phase (coacervate) and surfactants – poor phase (diluted phase) [12], [13], [14], [15], [16], [17], [18], [19].

Studies conducted by Wasilewski, Bujak and Seweryn [8], [9], [10], [40] have demonstrated that the coacervation process is influenced not only by the types of surfactants but also by the type of electrolyte used.

In recent years, particular attention in the development of formulations has been paid to product safety. The focus on safety is a consequence of growing consumer awareness and changes in cosmetic legislation implemented in a number of countries, aimed at ensuring product safety and quality through appropriate conditions of manufacturing and control of cosmetics. In body wash cosmetics reduction of the skin irritation potential is usually achieved by incorporating mixtures of various surfactant types into formulations. This solution contributes to the stabilization of micellar aggregates formed in solutions, and thus reduces the proportion of individual surfactant molecules (monomers), which have the most pronounced skin irritation effect, in the systems [20], [21], [22], [23], [24], [25], [26], [27], [28], [29], [30], [31], [32], [33], [34], [35], [36], [37], [38].

Research has also identified other solutions aimed at lowering the skin irritation effect, such as the addition of plant extracts, polymers or protein hydrolyzates [39], [40], [41], [42], [43], [44], [45], [46], [47], [48], [49], [50], [51], [52], [53], [54], [55], [56].

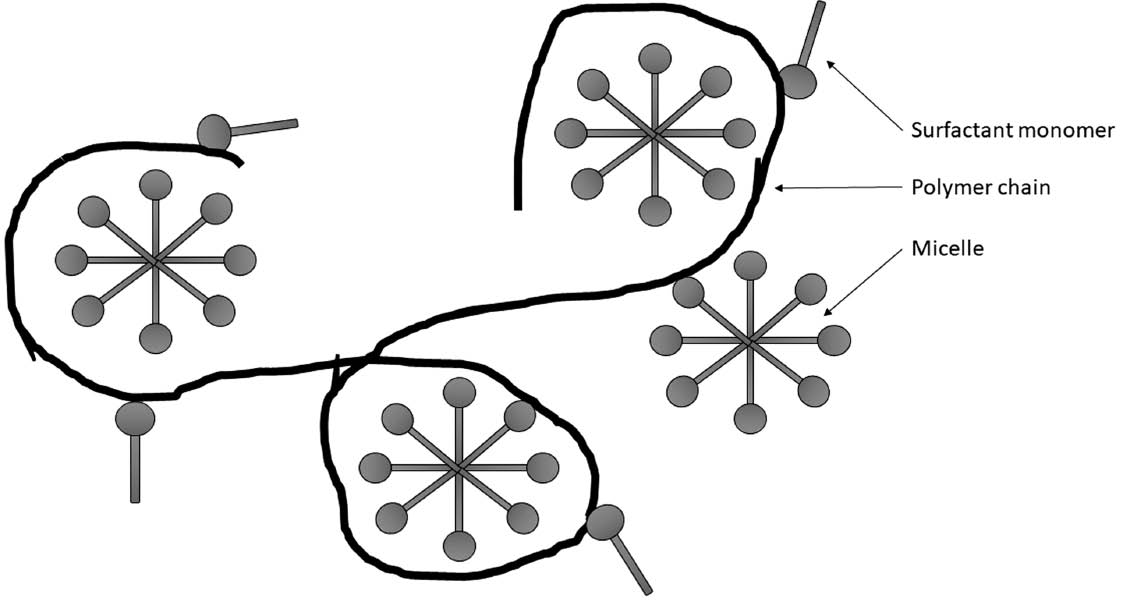

Polymers and proteins or protein hydrolyzates – owing to their ability to form complexes with surfactants – have an ability to stabilize micelles. By binding with them (and forming the so-called bead structures), they reduce the number of free monomers in the volume phase. A model system demonstrating interactions between surfactants and polymers consists of sodium dodecyl sulfate and polyvinylpyrrolidone (PVP), and can also be used as a cosmetic ingredient [43], [47], [48], [49], [50], [51], [52], [53], [54], [55], [56].

Previous studies [7], [43], [53] have shown that PVP and its derivatives have a significant effect on reducing the skin irritation potential of traditional body wash cosmetics based on an anionic surfactant, while maintaining full functional properties. The present study, which is a follow-up to the studies mentioned above, was an attempt to determine the effect of molecular mass of polyvinylpyrrolidone on the skin irritation potential and functional properties of model cosmetics. Model cosmetics were prepared using the coacervation process.

Materials and methods

Material

Raw materials used in the commercial cosmetics were used to develop the body wash gels: Sodium Laureth-2 Sulfate (SLES, trade name Brensurf 25; supplier Brenntag, Poland), Cocamidopropyl Betaine (Dehyton K, BASF, Germany), Citric Acid (Citric Acid, Chempur, Poland), Polyvinylpyrrolidone (pharmaceutical purity); average molecular weight 10 000, 40 000, 1 600 000 g/mol (Luviskol K17, K30, K90 BASF, Germany), Sodium Chloride (Sodium Chloride, Chempur, Poland), Sodium Benzoate and Potassium Sorbate Euxyl Schulke and Mayr, Schulke Poland), MiliQ water. In the physico-chemical tests were used: zein from corn (Zein, Sigma Aldrich, USA), Albumin (Albumin Bovine fraction V, Bioshop, Canada), potassium sulfate (Chempur, Poland), copper sulfate pentahydrate (Chempur, Poland), sulfuric acid 98% (Chempur, Poland), Tashiro indicator (Chempur, Poland), sodium hydroxide, citric acid (Chempur, Poland). All reagents were analytical grade.

Methods

Production technology of model body wash gels

Based on the principles of formulating body wash cosmetics which are widely employed in industrial practice, a range of own studies and a review of literature data, starting formulations were developed to obtain model body wash cosmetics in the form of coacervate. Their compositions are listed in Table 1.

Formulation of the starting composition for obtaining model body wash gel in coacervate form.

| Ingredients (INCI) | Concentration (wt.%) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| P1 | P2 | P3 | Base | |

| Sodium laureth sulfate | 10.0 | |||

| Cocamidopropyl Betaine | 0.5 | |||

| Polyvinylpyrrolidone (MW=10 000) | 1.0 | – | – | – |

| Polyvinylpyrrolidone (MW=40 000) | – | 1.0 | – | – |

| Polyvinylpyrrolidone (MW=1 600 000) | – | – | 1.0 | – |

| CI 42090 (1% aq) | 0.5 | |||

| Aqua | to 100 | |||

The main washing compound was the anionic surfactant sodium laureth sulfate which was used in the starting formulations at a concentration of 10 wt.%. The amphoteric surfactant Cocamidopropyl Betaine at a concentration of 0.5 wt.% was used as an auxiliary surfactant. Four formulations were selected for testing. One of them was a reference (baseline) sample which contained exclusively water and surfactants. The other three formulations (designated as P1, P2 and P3) additionally contained polyvinylpyrrolidone (PVP) at a concentration of 1 wt.%. The variable parameter in the test samples was the molecular mass of the polymer. PVP with a molecular mass of 10 000 g/mol (P1); 40 000 g/mol (P2) and 1 600 000 g/mol (P3) was used.

The technology used to obtain starting formulations and then coacervates involved the stage of dissolving in water of PVP (samples P1, P2 and P3), followed by washing substances. Deionized water was weighed into a beaker, and the polymer was added to it. The solution was mixed with a mechanical anchor stirrer (Chemland O20, Poland), at a rotational speed of 750 rpm, until complete dissolution of PVP. Next, surfactants were added and stirring was continued for 5 min. The samples were homogenized using IKA laboratory homogenizer with a blade rotational speed of 1500 rpm. The baseline sample was obtained through the dissolution of surfactants in water. The samples thus obtained were the starting formulation for obtaining model body wash cosmetics in the coacervate form. Next, the process of coacervation was carried out in the starting formulations by adding an electrolyte – sodium chloride (NaCl). NaCl was added in portions of 0.5 g per 100 g of the starting formulation. After adding each portion of salt the sample was stirred until its complete dissolution, and set aside for 15 min. Following that period, the sample was inspected to determine whether phase separation was present, confirming that coacervation had taken place. NaCl continued to be added until the process of coacervation was visible, manifested by the formation of two phases in the system at a volume ratio as close as possible to 1:1. If the coacervation process had occurred, the biphasic system was stirred again, transferred to a separator and left for 72 h in order to achieve precise phase separation. After that time the coacervate phase (representing a model body wash cosmetic) was isolated and analyzed to determine the content of active substances. To assess the irritant potential, the cosmetics in the coacervate form were preserved and their pH was adjusted, so that it corresponded to the physiological pH value of human skin (pH=5.5±0.1).

Determination of irritant potential – zein value (ZV)

Irritant potential of the products was measured using zein test. In the surfactants solution zein protein is denatured and then is solubilised in the solution. This process simulates the behavior of surfactants in relation to the skin proteins.

To 40 mL of the samples solution (10 wt.%) was added 2±0.05 g of zein from corn. The solutions with zein was shaken on a shaker with water bath (60 min at 35°C). The solutions were filtered on Whatman No. 1 filters and then centrifuged at 5000 rpm for 10 min. The nitrogen content in the solutions was determined by Kjeldahl method. One milliliter of the filtrate was mineralized in sulfuric acid (98%) containing copper sulfate pentahydrate and potassium sulfate. After mineralization the solution was transferred (with 50 mL of MiliQ water) into the flask of the Wagner – Parnas apparatus. Twenty milliliter of sodium hydroxide (25 wt.%) was added. The released ammonia was distilled with steam. Ammonia was bound by sulfuric acid (5 mL of 0.1 N H2SO4) in the receiver of the Wagner – Parnas apparatus. The unbound sulfuric acid was titrated with 0.1 N sodium hydroxide. Tashiro solution was used as an indicator. The zein number (ZN) was calculated from the equation:

where V1 is the volume (cm3) of sodium hydroxide used for titration of the sample. The final result was the arithmetic mean of five independent measurements.

Determination of irritant potential – pH rise test with bovine albumin serum (BSA)

Fifty grams of aqueous solution of BSA (2 wt.%, pH=5.5) was mixed with 50 g of body wash gels solution (10 wt.%, pH=5.5). pH of the BSA and analyzed samples solution was regulated with the sodium hydroxide or citric acid. Samples were stirred (200 rpm, 3 h). After 72 h incubation at room temperature pH was measured (pH-meter Elmetron, combination pH electrode, 22°C). The final result was the arithmetic mean of five independent measurements. The results was calculated from the formula:

where: pH1 – pH value of the sample after incubation, pH0 – pH value of the sample before incubation (5.5).

Determination of the turbidity

The test was performed using a HACH 2100 AN turbidity analyzer (turbidimeter). The sample was transferred to a cuvette, which was then placed in the measuring chamber of the turbidimeter. The results were evaluated after their stabilization. The final result was the arithmetic mean of five independent measurements.

Determination of the foaming properties

The method of measurement was in line with Polish Standard PN-ISO 696:1994P (Surface active agents – Measurement of foaming power – Modified Ross-Miles method). The foam volume produced by 500 mL of samples solutions (1 wt.%) falling from a height of 450 mm into a cylinder (1000 mL) containing 50 mL of the same solution was measured. Measurements were carried out at 22 °C. The final result was the arithmetic mean of five independent measurements. Foam stability was calculated from the equation:

where: V10 – foam volume after 10 min, V1 – foam volume after 1 min.

Viscosity measurements

A Fungilab Expert (Fungilab, Spain) rheometer was used. Measurements were carried out at 22°C with a rotary speed of the spindle of 10 rpm. Viscosity values presented in the figures below represent average values obtained from five independent measurements.

Error analysis

The points in the charts represent mean values from a series of three or five independent measurements. The t distribution was used to calculate confidence limits for the mean values. Confidence intervals, which constitute a measuring error, were determined for the confidence level of 0.90. Error values are presented in the figures.

Results and discussion

Analyzed of coacervation phases

The process of coacervation was observed in all four starting formulations as a result of sodium chloride addition. Table 2 lists values of the optimum NaCl concentration necessary for coacervation to take place in each of the samples under analysis and volumes of the (surfactant-rich) coacervate phase and the (diluted, surfactant-poor) aqueous phase formed during the process.

Concentration of sodium chloride causing the coacervation process and volume of separated phases.

| Sample (starting composition) | Concentration of sodium chloride causing the coacervation process (g NaCl/100 g starting composition) | Volume of separated phase (vol.%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Diluted phase | Coacervate phase | ||

| Base | 12.5 | 40.0 | 60.0 |

| P1 | 13.5 | 46.0 | 54.0 |

| P2 | 13.5 | 45.0 | 55.0 |

| P3 | 14.5 | 45.0 | 55.0 |

In each of the cases analyzed, the coacervation process produced biphasic systems in which coacervate was the top phase (the dye introduced to the system passes into the enriched phase, i.e. coacervate). The coacervation process occurred for different test samples at varying NaCl concentrations. The lowest salt concentration (12.5 g of NaCl per 100 g of the starting formulation) was needed for coacervate formation in the baseline formulation. Introducing PVP into the system contributes to an increase in the content of the electrolyte, for which the process of coacervation is observed. Samples containing the polymer with molecular weights of 10 000 and 40 000 g/mol required the addition of 13.5 g of NaCl for coacervation to occur. An increase in molecular mass caused an increase in the optimum electrolyte concentration. Accordingly, for the starting formulation containing PVP with a molecular mass of 1 600 000 g/mol the process of coacervation took place after adding 14.5 g of NaCl to 100 g of the starting formulation. Polyvinylpyrrolidone in systems containing anionic surface active agents shows an ability to create complexes with surfactants occurring both in the form of monomers and micellar aggregates formed in solutions after the CMC is exceeded (Fig. 1) [47], [48], [49], [50], [51], [52].

Interactions of surfactants with polymers.

The emergence of polymer-surfactant complexes of this type may have a direct effect on the observed differences in NaCl concentrations determining the occurrence of the process of coacervation and the formation of the coacervate phase. The addition of polymer (PVP) has an impact on increasing the system’s stability. The transformation of micellar shapes from spherical to cylindrical and then lamellar droplets, the flocculation of which is essential for the process of coacervation, may be markedly more difficult in the presence of PVP which is capable of their stabilization. However, as the molecular mass of PVP grows, system stabilization increases, and consequently inducing the process of coacervation requires a higher concentration of NaCl to occur.

The study also found that the addition of PVP had an impact on the volume of phases arising after the separation of systems due to the coacervation process. The phase separation ratio after coacervation will affect the content of active substances in the coacervate phase and determine its concentration, and ultimately the functional properties of body wash products in the coacervate phase. Consequently, the concentration of NaCl was selected in such a way as to make it optimal and to achieve the highest possible concentration of surfactants in the separated coacervate phase. The highest percentage content of the coacervate phase (60%) was noted in the baseline sample. Consequently, this sample can be treated as the sample with the lowest concentration of surfactants. PVP-enriched samples were characterized by a lower percentage content of the coacervate phases (i.e. higher degrees of concentration), at a level of approximately 55%. However, the molecular mass of PVP was found to have no effect on the volumes of separated coacervate phases (differences within the margin of error).

In the next stage of the study, the content of active substances (surfactants+PVP+dye) in the separated coacervate phases was evaluated. To this end, gravimetric assessment was performed for each coacervate obtained from the starting formulation to determine the content of dry matter and sodium chloride. Based on the difference between the values, the content of active substances contained in the phases separated during the process of coacervation was evaluated. The results are listed in Table 3.

Concentration of sodium chloride, dry matter and concentration of active matter in coacervate phases separated from starting compositions.

| Sample (coacervate) | Concentration of sodium chloride (%) | Dry mass (%) | Concentration of active matter (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Base | 13.7 | 26.8 | 13.1 |

| P1 | 13.3 | 29.2 | 15.9 |

| P2 | 13.2 | 29.0 | 15.8 |

| P3 | 13.5 | 29.3 | 15.8 |

The results show that the addition of PVP to the starting formulations for obtaining body wash cosmetics in the coacervate form produces more concentrated coacervates than that obtained for the baseline sample. The coacervate phase arising from the coacervation process in the baseline sample contains approximately 13.1% of active substances. The content of active substances in the samples P1, P2 and P3 containing PVP with different molecular masses was in the similar range of approximately 15.8–15.9%. The molecular mass of the polymer had no effect on the content of active substances in the obtained coacervate phases. The differences identified between the baseline sample and the samples P1, P2 and P3 are attributable to a difference in the compositions of starting formulations from which coacervate is obtained (in addition to surfactants present in the baseline sample, the samples P1, P2 and P3 additionally contained PVP) and a difference in the volume of obtained phases.

Irritant potential

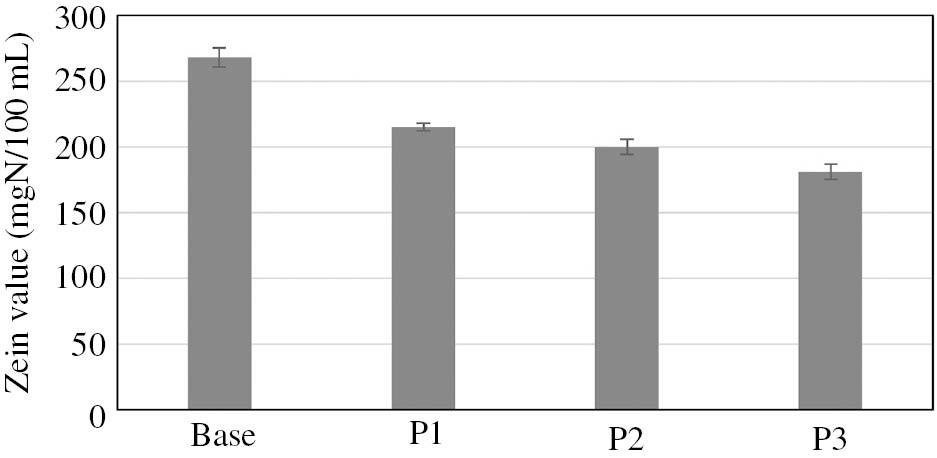

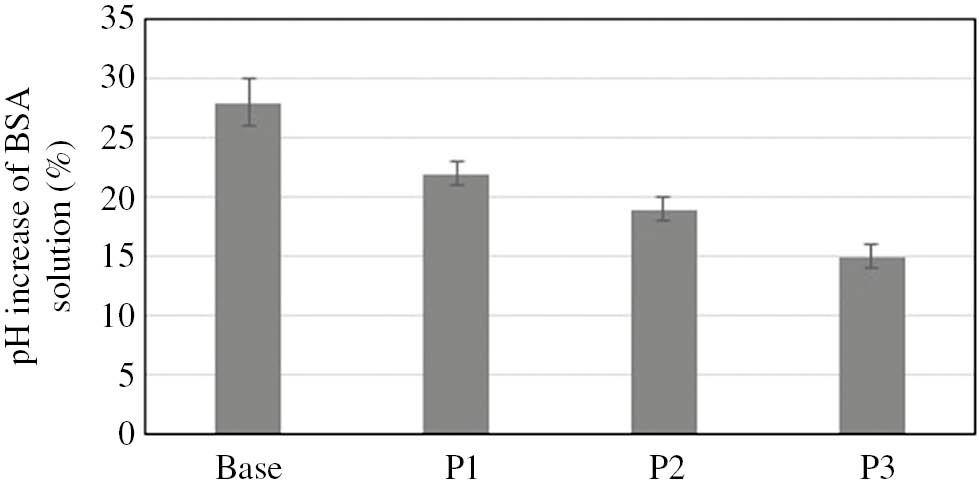

In the next stage of the study, the coacervate phases obtained from the starting formulations were preserved, and their pH was adjusted to the value of 5.5±0.1. The coacervate samples thus obtained, representing model body wash cosmetics, were tested to evaluate their skin irritation potential. The zein number was determined, and an incubation test with bovine serum albumin was performed. The results are shown in Figs. 2 and 3.

Irritant potential (zein value) of model body wash cosmetics in coacervate form.

Increase of pH of BSA with model body wash cosmetics in coacervate form.

As pointed out in the introductory section, one of the main disadvantages of using body wash cosmetics is their potential to cause skin irritation. This applies in particular to cosmetics based on anionic surfactants such as sodium laureth sulfate or sodium lauryl sulfate. Following their adsorption on the skin surface, they interact through electrostatic interactions with the surface proteins. The process leads to changes in the structure of proteins and their denaturation. Water used for skin washing exhibits no ability to dissolve and wash away proteins from the skin. In contrast, surfactant solutions through their protein-binding ability may result in proteins being washed away from the skin, which manifests itself through skin irritation. The literature indicates that the process outlined above is the basic mechanism underlying skin irritations induced by washing substances. It has been proposed that the skin irritation potential of body wash cosmetics should be reduced by limiting the surfactant-induced process of washing proteins from the skin. Results of multiple studies show that the main factors affecting interactions between surfactants and skin surface proteins are the type, concentration and duration of skin exposure to surfactants. The strongest interactions are observed at concentrations below the critical micelle concentration (CMC) and for surfactants containing 12 carbon atoms in the hydrophobic chain. At concentrations below the CMC, the binding of surfactants to proteins rises significantly along with the increase in surfactant concentration. At surfactant concentrations above the CMC, the interactions are not directly proportional, and their nature depends on the type of the surface active agent. Studies [7], [8], [9], [10], [11], [12], [13], [14], [15], [16], [17], [18], [19], [20], [21], [22], [23] show that irritant effect is attributable primarily to monomers, i.e. individual surfactant molecules (the form occurs in solutions below the CMC). On account of their small size, monomer molecules are able to easily penetrate through the skin and interact with proteins. The process is much more difficult for micelles, which are larger in size. Aggregates arising in micellar systems are thermodynamically unstable and, as a result, they constantly disintegrate, releasing free monomers into the volume phase of solutions. Consequently, stabilization of micelles formed in solutions, coupled with a decrease in the number of free monomers contained in them, may be the best solution for reducing the adverse interactions of surfactants with the skin and the development of skin irritations [4], [5], [6], [7], [8], [9], [10], [11], [12], [13], [14], [15], [16], [17], [18], [19], [20], [21], [22], [23].

Studies often use a test imitating interactions taking place between surfactants and proteins, which is based on zein number determination. Results obtained for analyzed coacervates show indisputably that the incorporation of PVP into the system markedly enhances the safety of using body wash cosmetics in the coacervate form. The result achieved for the baseline sample (approx. 270 mgN/100 mL) shows that the coacervate has an irritant effect on the skin. The addition of PVP to the formulations of model body wash cosmetics contributes to a decrease in the skin irritation potential, and the higher the polymer’s molecular mass, the more the skin irritation effect is reduced. The value obtained for the sample containing PVP with the lowest molecular mass is approximately 215 mgN/100 mL, and for the coacervate containing PVP with the highest molecular mass it is about 180 mgN/100 mL. Consequently, after PVP is added, the skin irritation potential of coacervates is reduced from approximately 20% (sample P1) to approximately 30% (sample P3) in relation to the baseline sample. The results were confirmed by performing an incubation test with BSA solution. Imokawa et al. [55] and Tavss et al. [57] proposed investigating changes in the pH level of the BSA solution as a method of predicting the irritant activity of the surfactant solution added to it. The authors demonstrated the suitability of the method for evaluating the irritant potential of anionic surfactants and their mixtures with other surfactants. Nonionic, cationic and amphoteric surfactants used alone have a very minor effect on BSA. The results obtained by Imokawa and Tavss corresponded to the results of the zein test and collagen swelling test, which demonstrates the suitability of the method for the estimation of irritant activity. An increase in the pH of the solution observed in such systems is caused by the neutralization of cationic BSA groups by anionic surfactants, and the adsorption of protons from the solvent (water) by negatively charged groups in the protein molecule [56], [57].

For the baseline sample, the pH increase was about 25%. In the PVP-enriched coacervates the increase was much lower and diminished along with increasing molecular mass of the polymer used. In the sample containing PVP with the lowest molecular mass it was approximately 20%, and in the model coacervate enriched with PVP with the highest molecular mass the increase in the pH of the BSA solution was just 15%. The results of both tests confirm the effectiveness of PVP as a substance that strongly reduces the skin irritation effect of anionic surfactants. The effectiveness of the polymer in the stabilization of structures formed in micellar systems was found to rise in proportion to increases in its molecular mass. Furthermore, longer polymer chains, which have more active centers capable of “capturing” free monomers, are able to decrease the adverse effect of surfactants on the skin proteins more powerfully.

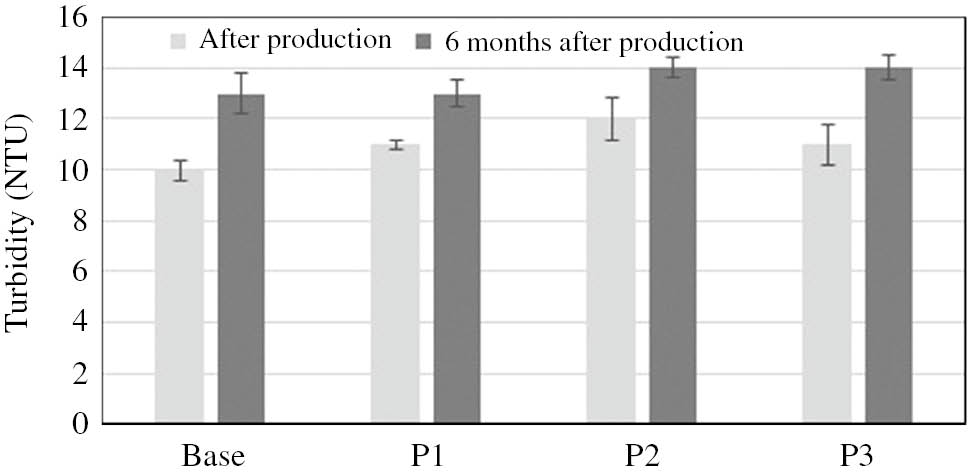

Stability and turbidity

In the process of product formulation it is vital to ensure that the desired improvement in product quality, and the selection of ingredients and product form to enhance a particular parameter, will not adversely affect other product quality determinants. As shown, the addition of PVP to the model body wash formulations, and the use of coacervate (a new physiochemical product form) contribute significantly to a reduction in the irritant effect. As the next stage of the study, an attempt was undertaken to evaluate the basic quality parameters in order to determine the effect of the solutions implemented in the model products on viscosity, stability and foaming properties. The stability of the coacervates obtained in the study was assessed on the basis of COLIPA Guidelines [58]. Thermal and mechanical load tests found the products to be stable. Also, there were no signs of microbiological instability or visual changes in the samples during a period of 6 months after product preparation. These findings were confirmed by turbidity tests which, after 6 months, yielded results that differed only in a statistically insignificant way from the values noted immediately after coacervate formation. In addition, the molecular mass of PVP was not found to have any effect on the measured values (Fig. 4).

Turbidity of model body wash cosmetis in coacervate form.

Foaming properties

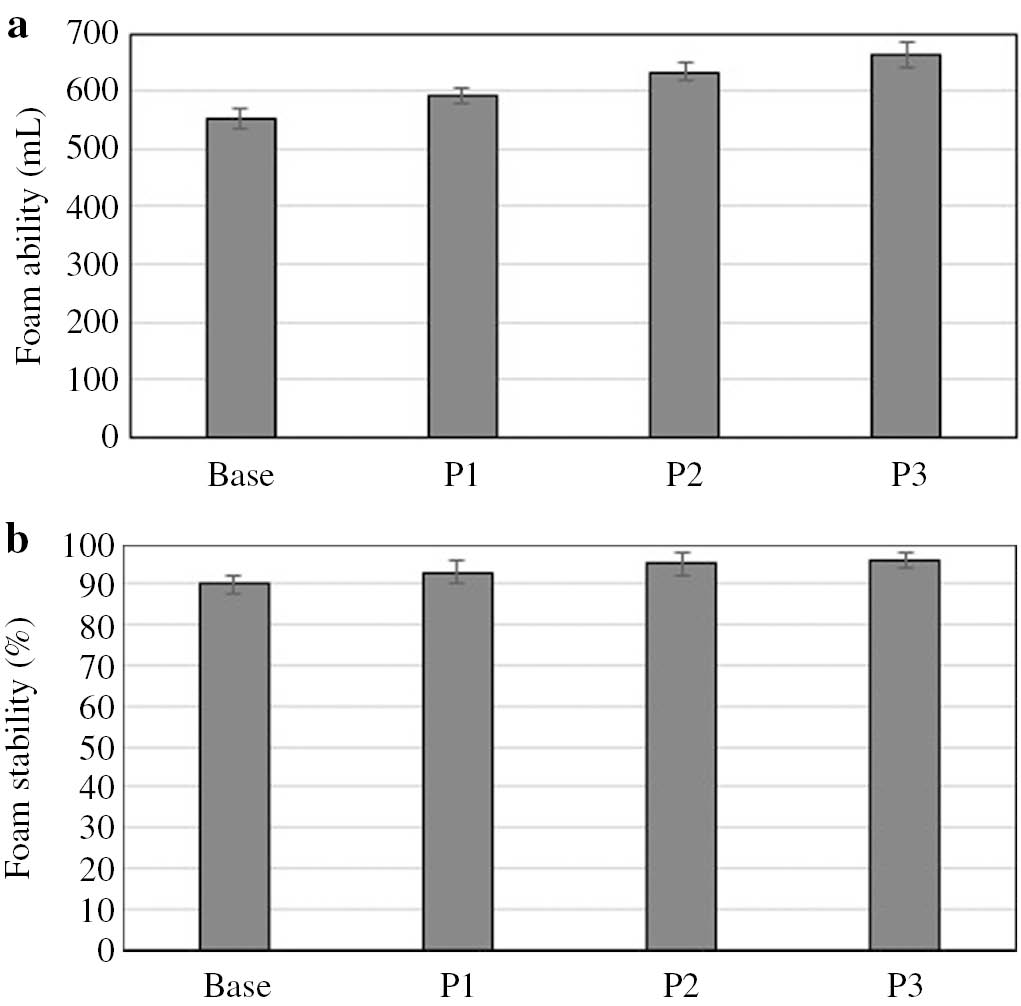

Furthermore, the tests found that the formulated model body wash cosmetics in the coacervate form exhibited very good foaming properties, and the foam they produced achieved very high values of the foam stability index (Fig. 5). In addition, there was an increase in the foaming ability of the products and a slight increase in foam stability index along with increasing molecular mass of PVP used in the formulations. The foaming ability in the sample P1 was about 10% higher than in the baseline sample, and in the sample P3, containing the polymer with the highest molecular mass, the value was approximately 20% higher.

Foaming properties of model body wash cosmetis in coacervate form.

The results obtained in the study can be interpreted by referring to surfactant–polymer interactions. The findings are consistent with reports available in the literature. Micelles arising in polymer–surfactant systems initially, i.e. at low surfactant concentrations, have the form of aggregates bound to polymer chains and emerge at a specific concentration which is referred to as the critical aggregation concentration (CAC). An increase in surfactant concentration causes gradual saturation of polymer chains with micelles. After all the active centers on the chains are saturated, free (polymer-unbound) micelles start occurring in the volume phase. Higher foaming ability and foam stability values are attributed, as Folmer and Kronberg claim [53], [54] a higher viscosity of the film separating gas bubbles in the foam structure. Higher viscosity reduces the dehydration of the intervesicular film, which leads to an increase in stability and volume of foam produced in polymer-containing systems, as compared to systems based exclusively on surfactants.

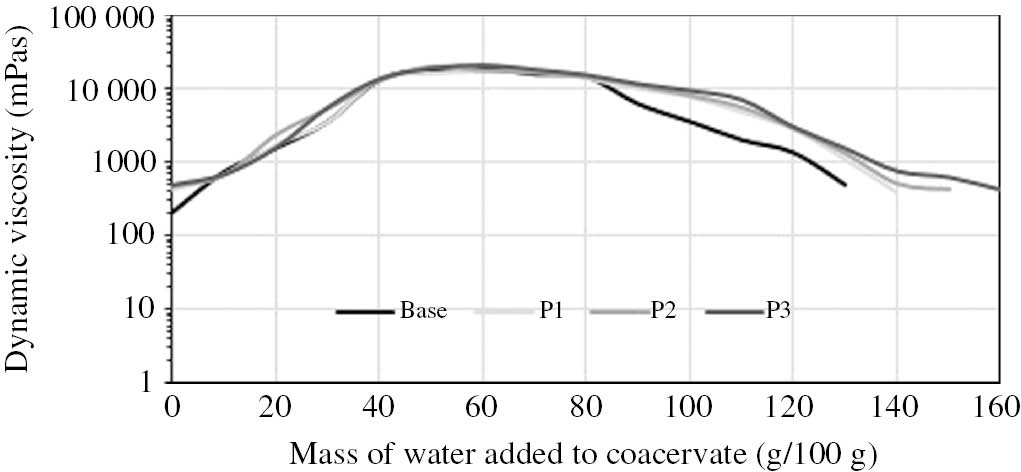

Viscosity properties

As the literature and our results (Fig. 6) show, the viscosity of coacervates increases as a result of adding water to them. Viscosity measurements performed for the model body wash cosmetics in the coacervate form as a function of added water are shown in Fig. 5.

Influence of water mass introduced into coacervates on their dynamic viscosity.

This is a very interesting property of the coacervate, particularly as a novel form of body wash cosmetics, because consumers view the viscosity of body wash products as the main determinant of quality (highly viscous products are regarded as products of top quality). Based on this property, coacervates can be seen as concentrated body wash products, and hence products with a high ecological appeal. A coacervate with a low viscosity level which is diluted in water acquires the consistency of a traditional product as a result of increasing viscosity. Consequently, consumers are able to control product quality according to their individual needs (coacervate dilution with water at different ratios, for example 1:1 or 1:2, makes it possible to obtain a product with more potent or more delicate washing abilities, etc.). In addition, the possibility of product distribution in small packages translates into a reduction of the size and volume of waste generated in households.

An increase in coacervate viscosity achieved through the addition of water is due to changes in the structure of micellar aggregates present in the coacervate. As mentioned above, the coacervate phase contains primarily bilayered lamellar structures in the form of the so-called lamellar vesicles [7], [8], [15], [16], [17]. Following the addition of water, the product becomes diluted and the structures transform into cylindrical micelles (an increase in viscosity). An increase in the concentration of added water increases viscosity up to a certain maximum value, after which viscosity begins to drop as a result of formation of flattened spherical micelles, followed by spherical micelles, in the system [7], [8], [9], [10], [11].

Conclusion

The study found that the application of PVP in the formulations of model body wash cosmetics had an effect on the properties of model body wash cosmetics in the coacervate form. Coacervates obtained on the basis of PVP-enriched formulations showed a higher degree of active substance concentration. However, despite a higher content of active ingredients they are characterized by a markedly lower skin irritation potential. The irritant effect of PVP-containing coacervates was approximately 20–30% lower in relation to the baseline sample, and the parameter was found to decrease as a function of the molecular mass of the polymer used. In addition, the use of PVP has an positive effect on the foaming properties of cosmetic products. It was found that the addition of PVP improves foaming properties and foam stability. The volume of the produced foam and its stability increase with increasing the molecular weight of the polymer.

Article note

A collection of invited papers based on presentations at the 1st International Conference on Chemistry for Beauty and Health, 13–16 June 2018, Nicolas Copernicus University in Torun, Poland.

References

[1] M. J. Rosen. Surfactants and Interfacial Phenomena, 3rd ed. John Wiley & Sons, Inc., New York (2006).Search in Google Scholar

[2] T. F. Tadros. Applied Surfactants. Principles and Applications. Wiley-VCH Verlag GmbH & Co. KGaA, Weinheim (2005).10.1002/3527604812Search in Google Scholar

[3] A. Barel, M. Paye, H. Maibach. Handbook of Cosmetic Science and Technology, 4th ed. Taylor & Francis Group, Boca Raton (2014).10.1201/b16716Search in Google Scholar

[4] M. Abe, J. F. Scamehorn. Mixed Surfactant Systems, 2nd ed. Marcel Dekker, New York (2005).10.1201/9781420031010Search in Google Scholar

[5] R. J. Farn. Chemistry and Technology of Surfactants. Blackwell Publishing, New Jersey (2006).10.1002/9780470988596Search in Google Scholar

[6] L. Rhein, M. Schlossman, A. O’Lenick, P. Somasundaran. Surfactants in Personal Care Products and Decorative Cosmetics, 3rd ed. CRC Press Taylor & Francis Group, Boca Raton (2006).10.1201/9781420016123Search in Google Scholar

[7] T. Bujak, T. Wasilewski, Z. Nizioł-Łukaszewska. Colloids Surf. B135, 497 (2015).10.1016/j.colsurfb.2015.07.051Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[8] T. Wasilewski. J. Surf. Deterg.13, 513 (2010).10.1007/s11743-010-1189-4Search in Google Scholar

[9] T. Wasilewski, T. Bujak. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res.53, 13356 (2014).10.1021/ie502163dSearch in Google Scholar

[10] A. Seweryn, T. Wasilewski, T. Bujak. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res.55, 1134 (2016).10.1021/acs.iecr.5b04048Search in Google Scholar

[11] T. Wasilewski, J. Arct, K. Pytkowska, A. Bocho-Janiszewska, M. Krajewski, T. Bujak. Przem. Chem.94, 111 (2015).Search in Google Scholar

[12] A. Sein, J. Engberts. Langmuir11, 455 (1995).10.1021/la00002a015Search in Google Scholar

[13] A. Sein, J. Engberts, E. van der Linden, J. C. van de Pas. Langmuir9, 1714 (1993).10.1021/la00031a018Search in Google Scholar

[14] D. Lasic. Biochem. J.256, 1 (1988).10.1042/bj2560001Search in Google Scholar

[15] F. Menger, B. Sykes. Langmuir14, 4131 (1988).10.1021/la980208mSearch in Google Scholar

[16] H. B. Bohidar. J. Surf. Sci. Technol.24, 105 (2008).Search in Google Scholar

[17] R. Wang, Y. Wang. Soft Matter.10, 1705 (2014).10.1039/c3sm52819gSearch in Google Scholar

[18] S. Benite. Microencapsulation. Methods and Industrial Applications. Taylor & Francis Group, Boca Raton (2006).Search in Google Scholar

[19] T. Kalantar, C. Tucker, A. Zalusky, T. Boomgaard, B. Wilson, M. Ladika, M. Jordan, S. Li, X. J. Zhang. J. Cosmet. Sci.58, 375 (2007).Search in Google Scholar

[20] T. Agner, J. Serup. J. Invest. Dermatol.95, 543 (1990).10.1111/1523-1747.ep12504896Search in Google Scholar

[21] S. C. Dasilva, R. P. Sahu, R. L. Konger, S. M. Perkins, M. H. Kaplan, J. B. Travers. Arch. Dermatol. Res.304, 65 (2012).10.1007/s00403-011-1168-2Search in Google Scholar

[22] G. D. Nielsen, J. B. Nielsen, K. E. Andersen, P. Grandjean. Int. J. Occup. Environ. Health6, 138 (2000).10.1179/oeh.2000.6.2.138Search in Google Scholar

[23] R. M. Walters, M. J. Fevola, J. J. Librizzi, K. Martin. Cosmet. Toilet. 123, 53 (2008).Search in Google Scholar

[24] A. Faucher, E. D. Goddard. J. Soc. Cosmet. Chem.29, 323 (1978).Search in Google Scholar

[25] T. J. Hall-Manning, G. H. Holland, G. Rennie, P. Revell, J. Hines, M. D. Barratt, D. A. Basketter. Food. Chem. Toxicol.36, 233 (1998).10.1016/S0278-6915(97)00144-0Search in Google Scholar

[26] T. Iwasaki, M. Ogawa, K. Esumi, K. Meguro. Langmuir7, 30 (1990).10.1021/la00049a008Search in Google Scholar

[27] P. N. Moore, S. Puvvada, D. Blankschtein. J. Cosmet. Sci.54, 29 (2003).Search in Google Scholar

[28] D. T. Downing, W. Abraham, B. K. Wegner, K. W. Willman, J. L. Marshall. Arch. Dermatol. Res.285, 151 (1993).10.1007/BF01112918Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[29] H. Loffer, R. Happle. Contact Dermatitis48, 26 (2003).10.1034/j.1600-0536.2003.480105.xSearch in Google Scholar PubMed

[30] V. Charmonnier, B. M. Morrison, M. Paye, H. I. Maibach. Food. Chem. Toxicol.39, 279 (2001).10.1016/S0278-6915(00)00132-0Search in Google Scholar

[31] T. Polefka. “Surfactants interaction with skin”, in Handbook of Detergents. Part A: Properties. Surfactant Science Series, G. Broze (Eds.), p. 82. Marcel Dekker Publications, New York (1999).10.1201/b10985-12Search in Google Scholar

[32] J. G. Dominguez, F. Balaguer, J. L. Parra, C. M. Pelejero. Int. J. Cosmet. Sci.3, 57 (1981).10.1111/j.1467-2494.1981.tb00268.xSearch in Google Scholar

[33] A. Teglia, G. Secchi. Cosmet. Toilet.111, 61 (1996).10.1007/978-1-349-25502-3_2Search in Google Scholar

[34] M. Paye, C. Block, N. Hamaide, G. E. Hüttman, S. Kirkwood, C. Lally, P. H. Lloyd, P. Makela, H. Razenberg, R. Young. Tenside Surfact. Deterg.4, 290 (2006).10.3139/113.100316Search in Google Scholar

[35] J. P. McFadden, D. B. Holloway, E. G. Whittle, D. A. Basketter. Contact Dermatitis.43, 264 (2000).10.1034/j.1600-0536.2000.043005264.xSearch in Google Scholar

[36] A. Teglia, G. Mazzola, G. Secchi. Cosmet. Toilet.108, 56 (1993).Search in Google Scholar

[37] I. Effendy, H. Maibach. Clin. Dermatol.14, 15 (1996).10.1016/0738-081X(95)00103-MSearch in Google Scholar

[38] T. Bujak, Z. Nizioł-Łukaszewska, K. Gaweł-Bęben, A. Seweryn, M. Kucharek, K. Tkaczyk, M. Matysiak. Green Chem. Lett.8, 78 (2015).10.1080/17518253.2015.1111431Search in Google Scholar

[39] K. Gaweł-Bęben, T. Bujak, Z. Nizioł-Łukaszewska, B. Antosiewicz, A. Jakubczyk, M. Karaś, K. Rybczyńska. Molecules20, 5468 (2015).10.3390/molecules20045468Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[40] T. Wasilewski, A. Seweryn, T. Bujak. Green Chem. Lett.9, 114 (2016).10.1080/17518253.2016.1180432Search in Google Scholar

[41] Z. Nizioł-Łukaszewska, P. Osika, T. Wasilewski, T. Bujak. Molecules22, 320 (2017).10.3390/molecules22020320Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[42] Z. Nizioł-Łukaszewska, T. Wasilewski, T. Bujak, P. Osika. Pol. J. Chem. Technol.19, 122 (2017).10.1515/pjct-2017-0078Search in Google Scholar

[43] T. Bujak, Z. Nizioł-Łukaszewska, T. Wasilewski. Tenside Surf. Det.55, 96 (2018).10.3139/113.110547Search in Google Scholar

[44] I. Pezron, L. Galet, D. Clausse. J. Colloid Interface Sci.180, 285 (1996).10.1006/jcis.1996.0301Search in Google Scholar

[45] A. Otzen. Biochem. Biophys. Acta1814, 562 (2011).10.1016/j.bbapap.2011.03.003Search in Google Scholar

[46] K. Holmberg, B. Jonsson, B. Kronberg, B. Lindman. Surfactants and Polymer in Aqueous Solution, John Wiley & Sons, West Sussex (2003).10.1002/0470856424Search in Google Scholar

[47] E. D. Goddard. J. Colloid Interface Sci.256, 228 (2002).10.1006/jcis.2001.8066Search in Google Scholar

[48] A. Boissier, J. E. Lofroth, M. Nyden. Colloids Surf. A301, 444 (2007).10.1016/j.colsurfa.2007.01.033Search in Google Scholar

[49] D. P. Norwood, E. Minatti, W. F. Reed. Macromolecules31, 2957 (1998).10.1021/ma971318nSearch in Google Scholar

[50] A. M. Tedeschi, E. Busi, R. Basosi, L. Paduano, G. D’Errico. J. Solution Chem.35, 951 (1998).10.1007/s10953-006-9041-1Search in Google Scholar

[51] A. Zanette, C. F. Lima, A. A. Ruzza, A. Belarmino, S. de F. Santos, V. Frescura, D. Marconi, S. J. Froehner. Colloids Surf. A147, 89 (1999).10.1016/S0927-7757(98)00746-8Search in Google Scholar

[52] R. Petkova, S. Tcholakova, N. D. Denkov. Colloids Surf. A438, 174 (2013).10.1016/j.colsurfa.2013.01.021Search in Google Scholar

[53] B. M. Folmer, B. Kronberg. Langmuir16, 5987 (2000).10.1021/la991655kSearch in Google Scholar

[54] J. Maldonado-Valderrama, A. Martín-Molina, A. Martín-Rodriguez, M. A. Cabrerizo-Vílchez, M. J. Gálvez-Ruiz, D. Langevin. J. Phys. Chem. C111, 2715 (2007).10.1021/jp067001jSearch in Google Scholar

[55] G. Imokawa, K. Sumura, M. Katsumi. J. Am. Oil Chem. Soc.52, 484 (1975).10.1007/BF02640737Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[56] E. A. Tavss, E. Eigen, A. M. Kligman. J. Soc. Cosmet. Chem.39, 267 (1988).Search in Google Scholar

[57] S. Deep, J. C. Ahluwalia. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys.3, 4583 (2001).10.1039/b105779kSearch in Google Scholar

[58] The European Cosmetic, Toiletry and Perfumery Association (Colipa). Guidelines on stability testing of cosmetic products. (2007).Search in Google Scholar

©2019 IUPAC & De Gruyter. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. For more information, please visit: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- In this issue

- Preface

- ICS-29: The 29th International Carbohydrate Symposium

- Conference papers

- 1-(2-Aminoethyl)-3-methyl-1H-imidazol-3-ium tetrafluoroborate: synthesis and application in carbohydrate analysis

- One-pot oligosaccharide synthesis: latent-active method of glycosylations and radical halogenation activation of allyl glycosides

- Nanoparticles for the multivalent presentation of a TnThr mimetic and as tool for solid state NMR coating investigation

- Preface

- Papers from the 1st International Conference on Chemistry for Beauty and Health (Beauty-Torun’2018)

- Conference papers

- In vivo electrical impedance measurement in human skin assessment

- Formulation and characterization of some oil in water cosmetic emulsions based on collagen hydrolysate and vegetable oils mixtures

- Preparation of polylactide scaffolds for cancellous bone regeneration – preliminary investigation and optimization of the process

- Effect of molecular weight of polyvinylpyrrolidone on the skin irritation potential and properties of body wash cosmetics in the coacervate form

- Ortho-substituted azobenzene: shedding light on new benefits

- Erratum

- Erratum to: Efforts to improve Japanese women’s status in STEM fields

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- In this issue

- Preface

- ICS-29: The 29th International Carbohydrate Symposium

- Conference papers

- 1-(2-Aminoethyl)-3-methyl-1H-imidazol-3-ium tetrafluoroborate: synthesis and application in carbohydrate analysis

- One-pot oligosaccharide synthesis: latent-active method of glycosylations and radical halogenation activation of allyl glycosides

- Nanoparticles for the multivalent presentation of a TnThr mimetic and as tool for solid state NMR coating investigation

- Preface

- Papers from the 1st International Conference on Chemistry for Beauty and Health (Beauty-Torun’2018)

- Conference papers

- In vivo electrical impedance measurement in human skin assessment

- Formulation and characterization of some oil in water cosmetic emulsions based on collagen hydrolysate and vegetable oils mixtures

- Preparation of polylactide scaffolds for cancellous bone regeneration – preliminary investigation and optimization of the process

- Effect of molecular weight of polyvinylpyrrolidone on the skin irritation potential and properties of body wash cosmetics in the coacervate form

- Ortho-substituted azobenzene: shedding light on new benefits

- Erratum

- Erratum to: Efforts to improve Japanese women’s status in STEM fields