Abstract

Martyrdom, as epitomized by the martyrdom of Ḥusayn ibn ʿAlī at Karbalāʾ in 680, occupies a central position in Shiʿi theology, symbolizing the ultimate sacrifice for truth and justice. This study analyzes how the “inheritance of martyrdom,” a concept involving the transgenerational transmission of martyrdom’s values, is visually and narratively recontextualized on Instagram. Employing a descriptive qualitative approach, the article collects and examines Instagram content to elucidate how the legacy of Ḥusayn’s martyrdom is preserved, reinterpreted, and adapted for contemporary audiences. The study begins with a review of the existing literature on Shiʿism in digital contexts, followed by a detailed analysis of Instagram posts pertaining to the inheritance of martyrdom. The findings underscore Instagram’s role in fostering a globalized and interactive form of religious expression within the Shiʿi community, revealing its impact on the preservation and reinterpretation of martyrdom narratives in the digital age.

Hosein inherits the Islamic movement. He is the Inheritor of a movement which Mohammad has launched, Ali has continued and in whose defense Hasan makes the last defense. Now there is nothing left for Hosein to inherit, no army, no weapons, no wealth, no power, no force, not even an organized following. Nothing at all… He is heir of the great suffering human being. He is the only successor to Adam, Abraham, Mohammad... a lonely man.

Ali Shariati

1 Introduction

Martyrdom holds a central and revered position in Shiʿi Islam, deeply rooted in the historical and theological fabric of the faith. This concept is primarily epitomized by the tragic events of Karbalāʾ in 680 CE, where Ḥusayn ibn ʿAlī, the grandson of the Prophet Muḥammad, and his companions were martyred by the forces of the Umayyād caliph Yazīd. Ḥusayn’s martyrdom is not only a historical event but also a symbol of the ultimate sacrifice for truth, justice, and resistance against oppression. It is a powerful narrative that resonates throughout Shiʿi theology, shaping the community’s identity and religious practices. Seen as the highest form of devotion and the ultimate act of piety, martyrdom offers a path to salvation and closeness to God. The martyr, by sacrificing their life for a just cause, is believed to achieve eternal life and divine reward. This belief is deeply intertwined with the concept of Imamate, where the Imams, who in Shiʿism are considered divinely appointed leaders, are viewed as the epitome of righteousness. Their lives and deaths, often marked by martyrdom, serve as exemplars for the Shiʿi community, guiding their spiritual and ethical conduct.

The concept of martyrdom has evolved into various interpretations, and in this article, I analyze the notion of the “inheritance of martyrdom,” which, in Islamic contexts, particularly within Shiʿi traditions, considers martyrdom as not only a historical reality but a spiritual and moral legacy transmitted through generations within the Prophet’s family (Ahl al-Bayt). The idea of martyrdom as a familial and spiritual inheritance is deeply embedded in Shiʿi sacred history. A particularly illustrative example appears in the sayings attributed to Imām ʿAlī ibn al-Ḥusayn (commonly known as Imām Zayn al-ʿĀbidīn), who survived the tragedy of Karbalāʾ. In a reported statement addressing the legacy of martyrdom, he declared: “Martyrdom is our inheritance.”[1] This conception is further emphasized in the defiant response from Imām Zayn al-ʿĀbidīn to the death threats from ʿUbayd Allāh ibn Ziyād: “Do you threaten to kill me? Do you not know that being killed is our tradition, and martyrdom is a dignity granted to us by God?.”[2]

This theology of inherited martyrdom finds further expression in the ziyārat al-taʿziya[3], a form of devotional visitation text, wherein Imām al-Ḥusayn is described as “martyr, son of the martyr, brother of the martyr, and father of the martyrs.” This litany affirms the familial continuity of martyrdom, referencing his father ʿAlī ibn Abī Ṭālib, his brothers Ḥasan and ʿAbbās, and his sons ʿAlī al-Akbar, ʿAlī al-Aṣghar, and ʿAlī ibn al-Ḥusayn (i.e., Imām Zayn al-ʿĀbidīn). These titles not only commemorate individual sacrifices but also frame martyrdom as an inherited vocation central to the Shiʿi ethos. In digital spaces, narratives of martyrdom are adapted to engage new audiences. I argue that Instagram serves as a vital digital platform for the representation of the inheritance of Ḥusayn’s martyrdom, where users engage in the visual and narrative recontextualizations of pivotal historical events. By utilizing Instagram’s unique features, such as hashtags, stories, and visual storytelling, believers and communities not only preserve but actively reinterpret Ḥusayn’s martyrdom to resonate with events from early Islamic history. This digital mediation fosters a globalized and interactive form of religious expression, reinforcing communal identity while simultaneously shaping modern understandings of martyrdom in the context of Shiʿi Islam.

While direct research specifically labeled as “inheritance of martyrdom” is limited, a substantial body of scholarship addresses related themes. For instance, events such as the Battle of Karbalāʾ are often contextualized within earlier historical events (e.g., Saqīfah, First Fitna) and seen as preconditions leading to the tragic martyrdom of Ḥusayn. Numerous scholarly works examine the history of Shiʿism and these events. However, there is a gap in understanding which specific events and their interpretations are most prevalent in digital contexts, such as Instagram, particularly regarding Ḥusayn’s martyrdom. This article aims to “bridge” this research and address this gap by focusing on how the inheritance of Ḥusayn’s martyrdom is represented and (re)interpreted on Instagram. The study employs a descriptive approach, utilizing a quantitative method to collect content data, which is then subjected to qualitative analysis of the topically selected population sample. Rather than creating a broad overview based on classifications or frequencies, as is typical in quantitative studies, the goal of this article is to explore the concept of the Inheritance of Martyrdom by conducting a detailed analysis of Instagram posts. The article begins with two sections: one on Shiʿism on the Internet and the other on Instagram, outlining the current state of research. Subsequent sections are dedicated to the methodology and case studies of Instagram interpretations related to the inheritance of martyrdom.

2 Shiʿism on Internet

Digital Religion studies examine how the Internet and new media create unique spaces where religion is performed and engaged. This field explores the intersection of technology, religion, and digital culture, including how religious communities use the Internet, express religiosity online, and consider technological engagement as a spiritual activity.[4] Shiʿi Islam’s presence in the digital space has significantly expanded in recent years, reflecting broader trends of religious engagement online. This digital shift has provided Shiʿi Muslims with new platforms to express their faith, engage in theological discourse, and build global communities that transcend geographical boundaries.[5] The internet has facilitated the dissemination of Shiʿi teachings, allowing for greater access to religious texts, sermons, and scholarly discussions.[6] This has not only enriched individual religious practices but also strengthened the collective identity of the global Shiʿi community.

Scholars of digital Shiʿism focus mainly on aspects such as the online presence of Shiʿi religious scholars and the increasing digitization of Shiʿi commemorations (Muharram and Arbaʿīn). Social media platforms, websites, and online forums have become crucial venues for Shiʿi scholars, religious leaders, and laypersons to share knowledge and debate theological issues.[7] Prominent Shiʿi clerics have embraced these platforms to reach wider audiences, offering live-streamed sermons, lectures, and Q&A sessions that allow followers to engage directly with religious authorities.[8] This has democratized access to religious knowledge, making it possible for Shiʿi Muslims worldwide to participate in religious education and discussions that were previously limited to physical settings like mosques and seminaries. Within the context of this research, I referred to prominent scholars active online who engage in discussion of Early Shiʿi Islamic History and interpretations of martyrdom narratives (e.g., Sayed Ammar Nakshawani, who is active on YouTube and Instagram, his official Instagram profile https://www.instagram.com/sayedammarofficial/).

The digital space has also become a significant arena for the commemoration of key events in Shiʿi Islam, such as ʿĀshūrāʾ and Arbaʿīn. The remembrance of martyrdom, especially during the month of Muḥarram, plays a vital role in the religious life of Shiʿi Muslims. Rituals of mourning, including recitations, processions, and dramatic reenactments of the Karbalāʾ tragedy, serve not only to memorialize the sacrifices of Ḥusayn and his companions but also to reinforce foundational values such as justice, patience, and resistance against tyranny. These practices contribute to a transhistorical collective memory that binds the Shiʿi community across geographic and temporal boundaries, cultivating a shared sense of identity and moral purpose. With the expansion of digital technologies, these commemorative practices have found new forms of expression online. Virtual processions, livestreamed majālis, and digital storytelling platforms enable Shiʿi Muslims to maintain and even intensify their ritual engagement, particularly in contexts where physical gatherings are limited. These online observances enhance the visibility of Shiʿism globally and facilitate affective connections among a dispersed transnational community. As Ali and Sunier maintain, earlier research on Islam and the internet has often overlooked social media, neglecting its interactive and performative dimensions.[9] Yet platforms such as Facebook, Twitter, and YouTube now host a vast array of Shiʿi media content, especially centered on lamentation and the rituals of Muḥarram, including images of processions, videos of majālis, and audio recordings of nawḥas. These digital forms generate new sensory and emotional experiences of devotion that transcend the online/offline binary and blur the boundaries between ritual performance and mediated practice.

Due to its scale and richness, this domain has become a prominent subject of inquiry within the field of Digital Shiʿism, attracting considerable scholarly attention.[10]

3 Shiʿism on Instagram

The expansion of global media infrastructures has significantly influenced the forms and intensity of religious activism, particularly by increasing the prominence of religion in the public sphere.[11] Shiʿi Islam’s presence on Instagram reflects the broader trend of using social media platforms to express and explore religious identity in contemporary contexts. Instagram, with its visually driven format, has become a powerful tool for Shiʿi Muslims to share their faith, culture, and community activities. The platform is used to disseminate religious teachings, commemorate important events, and foster a sense of belonging among followers through images, videos, and other multimedia content. In this study, I use the term “platform” pragmatically to refer to social media infrastructures without implying an equal playing field or unmediated public sphere. These structures inevitably influence what content becomes visible, shareable, or amplified, but for the purposes of visual content analysis, which examines what is actually produced, circulated, and aesthetically encoded, the exact architecture of platform politics is a significant but not disqualifying factor.

Following the trend from the previous section, scholarly research on Shiʿis on Instagram also concentrates mainly on religious scholars online and pilgrimage practices, as well as the role of Instagram in the reproduction of religious culture amongst Shiʿi Muslims, mainly youth.[12] Many Shiʿi clerics, scholars, and institutions maintain Instagram accounts where they post short videos, infographics, and written reflections on various aspects of Shiʿi theology, jurisprudence, and ethics. These accounts often serve as a resource for younger generations (both Muslims and non-Muslims) who prefer to engage with religious content in a format that is accessible and relatable. It also provides a place for interreligious dialogue and discussions. During Ramadhan 2024, the popular Shiʿi preacher Sayed Ammar Nakshawani posted a series of lectures and videos where he analyzed the events of Early Shiʿi Islam based on Sunni primary sources (one of the videos: https://www.instagram.com/p/C4u76IiCX6Z/, accessed on 12 August 2024).

Studying the Online Visual Culture of the Revolutionary Youth in Iran, Taherifard maintains that given the limited scope of published research on internet platforms and religiosity in Iran, the online culture of Shiʿi Iranians remains an underexplored area of study.[13] The same can be said about studies on Shiʿism on Instagram in general, therefore, when conducting this research, I also referred to the studies about Muslims and Islam in general on Instagram. One of such studies showed that the visual content produced by Muslims on Instagram encompasses a broad but still distinct field.[14] Since martyrdom narratives are more significant to Shiʿi theology, they make “distinct field” of Muslim content even more fragmented, presenting mainly Shiʿi-produced content.

Martyrdom narratives on Instagram have become a powerful means for Shiʿi Muslims to commemorate, reflect, and express their religious and cultural identity in a digital context. These narratives, deeply rooted in the historical and theological traditions of Shiʿi Islam, are brought to life through the visual and interactive nature of Instagram, allowing users to engage with the stories of martyrdom in a dynamic and personal way.[15] During important religious observances like ʿĀshūrāʾ and Arbaʿīn, Instagram is flooded with posts that depict the events of Karbalāʾ through various forms of visual media. These include illustrations, reenactments, calligraphy, and symbolic imagery such as blood-red hues, swords, and desert landscapes, all of which evoke the sacrifice and suffering of Ḥusayn and his followers. In general, Shiʿi cultural memory is strongly embedded within image-objects as material media, with their distinctive visual aesthetics and decorative forms shaped by the social and cultural contexts that enable such memory embodiment.[16] Such images are frequently accompanied by poignant quotes from religious texts, poetry, and personal reflections, which together create a powerful narrative that resonates with viewers on an emotional and spiritual level. To analyze these posts, I employed quantitative analysis, and prior to discussing the case studies, I will first provide a detailed outline of the methodology.

4 Methodology

This article uses a qualitative case study approach to analyze existing Instagram interpretations of the inheritance of Ḥusayn’s martyrdom. The research data were derived from relevant Instagram posts, with the primary objective being to locate these posts. Conducting participant observation without interacting with subjects allowed me to engage with Instagram content in its natural flow, observing how Shiʿi users express ritual and religious identity through publicly accessible posts. While this non-interactive approach could invite critique under the rubric of “armchair anthropology,” particularly concerns about detachment, decontextualization, or lack of ethnographic depth, it is important to distinguish my method as visual content analysis, which focuses on interpreting the symbolic, aesthetic, and affective dimensions of user-generated content as they are framed within the native platform environment. As Friedman argues, the internet now constitutes a vast and dynamic repository of lived experience, which allows researchers to study cultural production in situ rather than relying on secondhand or colonial-era accounts.[17] To avoid abstracting cultural traits into decontextualized universals, my approach engages with media in its embedded, performative, and context-rich digital setting. Given that Instagram is a vast array of images, I used hashtags as a filtering tool. These hashtags, chosen by users when posting content, link their posts to others using the same tags, facilitating connections between similar content.[18] The initial selection of hashtags was broad, with further refinement based on those used in posts that already contained narratives related to the inheritance of martyrdom. Many of these posts referenced general religious or denominational themes (e.g., #islam, #muslims, #shia), historical figures (e.g., #imamali, #imamhussain, #fatimazahra, #sayedazainab), or significant events (e.g., #karbala, #ghadeer, #saqifa). Some hashtags appeared with varying spellings (e.g., #ahlulbayt, #ahlalbayt), in different languages (primarily Arabic, e.g., #حسين), or with theological references (e.g., #yahussain, meaning “Oh Ḥusayn”). Many of these hashtags were associated with millions of posts (#shia: 2,380,901 posts; #karbala: 4,479,408; #imamali: 1,923,906; #imamhussain: 2,142,667; #yahussain: 2,124,504), making an automatic search for narratives of inheritance of martyrdom impractical. As the case studies will demonstrate, these posts may include various types of content, such as video content and tweet-like Instagram posts, that diverge from the studied concept. Consequently, after manually identifying relevant posts, a quantitative approach was deemed the most optimal.

The case study method is particularly effective for examining various aspects of a contemporary phenomenon within its real-life context. This article employs a “collective” multiple case research design to broaden the investigation, aiming to identify similarities and differences between cases for a more nuanced understanding of a complex social issue.[19] By using a multiple case study approach, this research provides an analytical framework for exploring the rich historical and religious contexts of the Instagram narratives.

The analysis of posts based on use of key approaches of mediatization, mediation of meaning, and religious–social shaping of technology, which offer valuable frameworks for understanding the relationship between religion and new media. Mediatization examines how the Internet shapes religious discourse and influences perceptions of religious authority. Mediation of meaning focuses on how new media narratives and symbols shape religious identities and practices. Religious–social shaping of technology analyzes how religious communities’ use of new media is influenced by historical, social, and religious factors, helping predict future engagement with technology. These approaches highlight a theoretical shift in Digital Religion studies toward understanding the interconnectedness of online and offline religious life.[20] The approach of mediatization was employed to examine how Instagram reshapes the discourse surrounding the inheritance of martyrdom within the Prophet’s family, particularly in terms of how these narratives are presented in the digital age. The mediation of meaning was utilized to analyze how Instagram’s visual and narrative tools shape religious identities and practices, while the religious-social shaping of technology provided insights into how historical and social contexts influence religious communities’ engagement with and adaptation to new media in preserving and reinterpreting these martyrdom traditions. Relying on the mentioned approaches, this article shows how offline Islamic history flows into digital space (namely Instagram) and which narratives and in which shape prevail there.[21]

Previous studies on Islamic visual and semantic content on Instagram reveal that nearly 40% of posts are quotes or text-based images. This finding is notable because Instagram, typically an image-focused platform, is being used predominantly to share textual content in the context of online Muslim representation. These posts often feature inspirational quotes, such as ḥadīth passages or Qur’anic verses.[22] Another surprising finding is the prominence of video content, which ranks as the third most common type of post. The majority of these videos are created by scholars, who use the platform to provide religious explanations or contextualize religious concepts.[23] The same applies to posts that will be presented further. Most of them feature historical narratives on blank pages (similar to tweets) or images of historical events. Given the focus on spaces constructed through online images and Instagram’s features, the study employed an embodied-spatial approach and a qualitative method of visual analysis grounded in social semiotics.[24] The latter enables a systematic exploration of how images, symbols, and visual elements in Instagram posts convey meaning, particularly concerning the representations of the inheritance of martyrdom within the Prophet’s family. An embodied-spatial approach reveals how digital media shapes and conveys embodied practices and spatial identities, providing insights into how users engage with and interpret their physical and cultural environments through a digital lens. In this study, it includes the depiction of ritualized bodies – examining how Ḥusayn’s and other figures’ bodily postures, gestures, and expressions in posts communicate specific messages or emotions; sacred spaces, where I analyze the physical settings portrayed and their relationship to users’ identities and the messages they convey; and sensory elements, investigating how posts evoke the physical and sensory dimensions of martyrdom traditions.

Defining Instagram posts as a form of visual imagery, I examine their materiality and internal narratives, focusing on how these digital objects represent themselves and their unique attributes. The concept of “reading” a photograph or other visual image extends the traditional terminology applied to written texts and is widely used to analyze various visual forms.[25] Effective visual research requires a comprehensive examination of both internal and external narratives. Visually, objects represent only themselves; their material existence confirms their autonomy. Thus, assessing their materiality, similarities within their category, and unique attributes involves analyzing their internal narrative. Simultaneously, as films, photographs, and artworks are products of human action and embedded in social contexts, they demand a broader analysis that includes their external narrative beyond the visual text itself.[26] Using it, in the case studies, I will also employ Terence Wright’s three approaches to reading photographs: “looking through,” “looking at,” and “looking behind.”[27] “Looking through” the posts involves understanding the symbolic and spiritual meanings they convey, while “looking at” them focuses on assessing their composition and immediate visual impact. Additionally, “looking behind” them allows for an exploration of the broader social, historical, and cultural contexts in which these representations are situated.

In line with ethical research practices, and considering that the analysis focused on a qualitative study of Instagram posts primarily from large-scale, thematic Shiʿi accounts (typically followed by tens or hundreds of thousands of users and functioning more like public media platforms than personal profiles, with highly curated religious content and no identifiable personal information), I chose to properly cite these posts. This decision also accounts for the fact that publicly accessible information may still be subject to copyright, intellectual property rights, or other dissemination restrictions, and seeks to avoid the potential consequences of over-anonymization or non-transparent sourcing in academic work. Given the public nature of these accounts, their high visibility, and the neutral, non-controversial religious focus of the content, I considered the risk to be minimal. A fuller discussion of my methodological approach to working with publicly available Instagram posts on Shiʿism, and the attendant ethical and practical considerations, is available elsewhere.[28]

5 Inheritance of Martyrdom on Instagram

In the passage used as the epigraph for this article, Ali Shariati characterizes Ḥusayn as the rightful heir to the movement of Muḥammad, ʿAlī, and Ḥasan. Shariati emphasizes that Ḥusayn, left with nothing but his own life, ultimately sacrifices it in the name of Islam.[29] To some extent, this depiction reflects the concept of inheritance of martyrdom, which is deeply embedded in Shiʿism. According to Twelver Shiʿi theology, the martyrdom narrative extends to almost all 14 Infallibles – comprising the Prophet Muḥammad, his daughter Fāṭima az- Zahrāʾ, and the 12 Shiʿi Imams. Cook underscores this by stating, “Beyond the martyrdoms of ʿAlī and al-Ḥusayn, the history of the family of the Prophet Muḥammad is one of martyrdom.”[30] This perspective highlights the profound significance of martyrdom within the Shiʿi tradition, wherein it is seen not merely as an isolated event but as a pervasive element of the familial and spiritual legacy of the Prophet’s lineage. In the context of this study, the martyrdom of Imam Ḥusayn is analyzed as a pivotal event within a broader continuum of martyrdoms affecting the family of the Prophet Muḥammad, and as a consequence of preceding historical developments. This section will examine how Instagram posts serve to connect and reflect these historical events.

Numerous studies[31] demonstrate that the narratives of martyrdom in Shiʿism are crafted to elicit a profound range of emotions, particularly by immersing individuals in grief and mourning. This emotional engagement is so significant that acts of crying for Ḥusayn and reciting poetry that prompts others to weep are considered acts of worship and virtuous deeds within the tradition. Accordingly, it is not surprising that Instagram posts about the events of Karbalāʾ and Imam Ḥusayn often aim to evoke deep emotions and foster compassion among users. Content creators achieve this either by using poignant videos that depict the suffering of Ḥusayn and the Prophet’s family or by incorporating historical narratives that illustrate these sufferings and events. Sensory experiences allow words, and in our case images, to come alive, and as such they can elicit memories, create connections, and allocate meaning.[32]

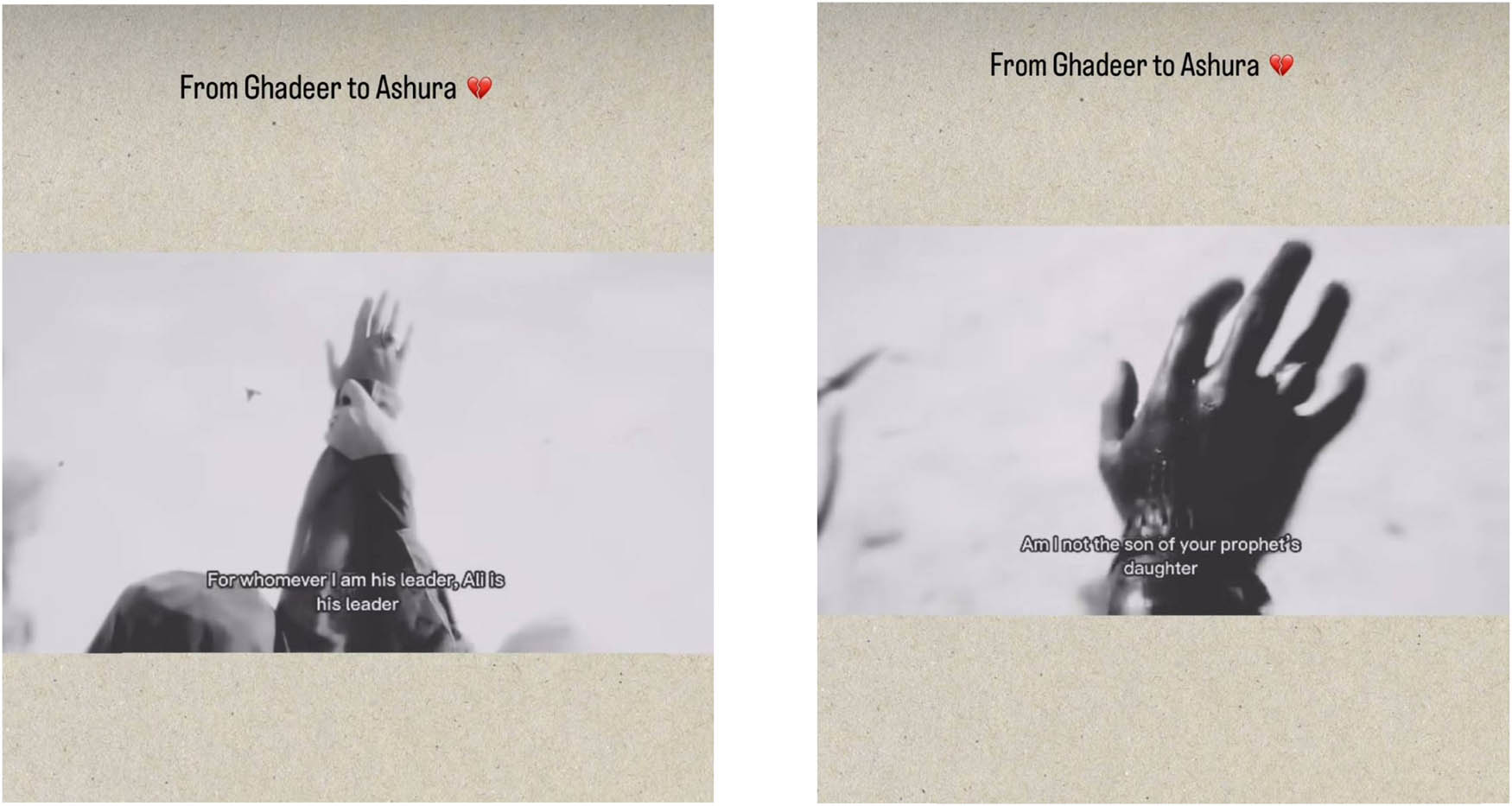

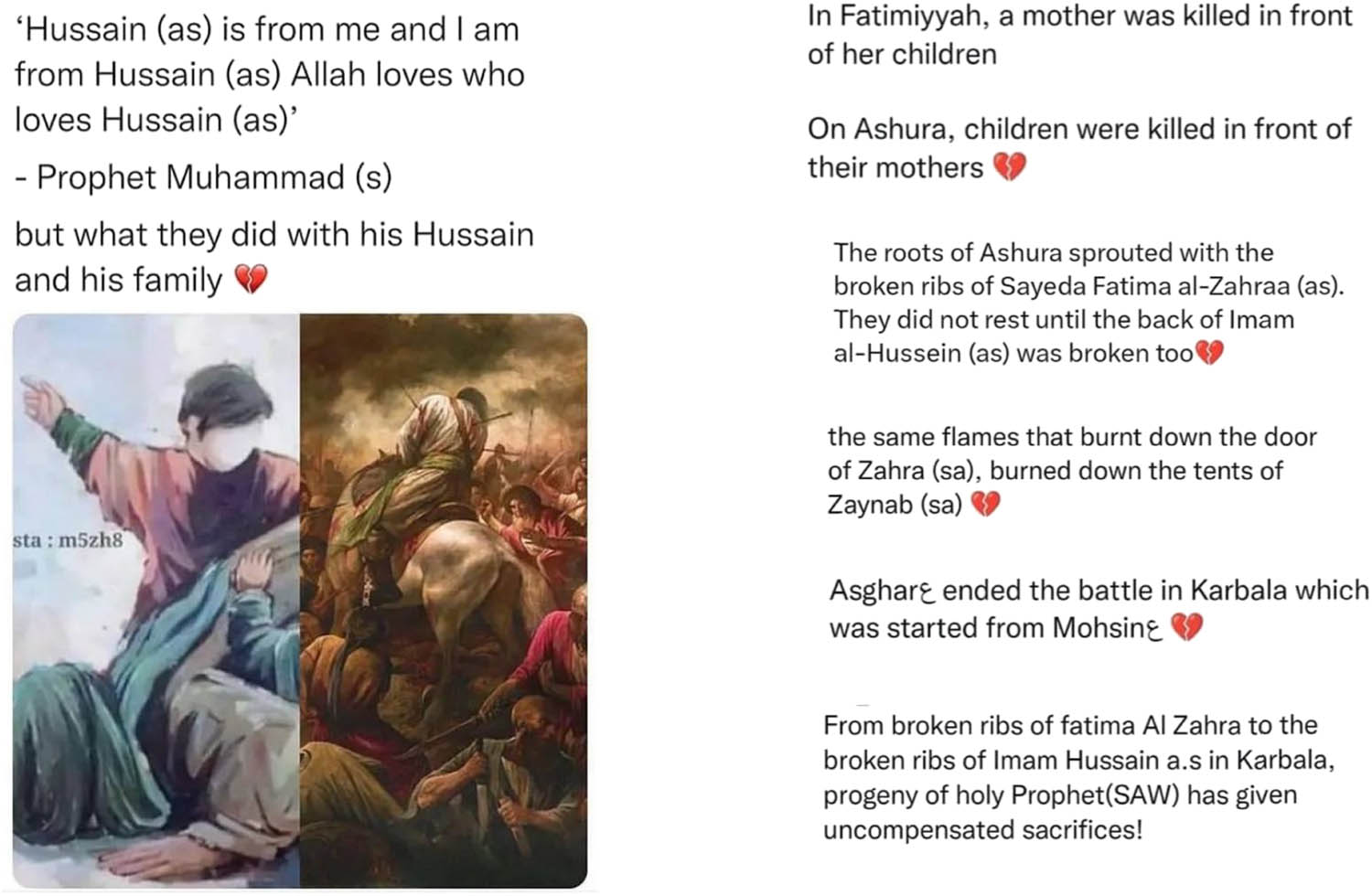

Instagram posts often use powerful and emotional visuals, such as artwork or illustrations depicting scenes from the Battle of Karbalāʾ. These images often portray the suffering and sacrifice of Imam Ḥusayn and his companions, highlighting their valor and martyrdom. This is exemplified by various videos, textual content, and photo/images, on Instagram, as illustrated in Figures 1 and 2, respectively.

Instagram Post of Shiatweets12, https://www.instagram.com/p/C9fNWHcC4Lf/(accessed on 11 August 2024).

Instagram Post of Shiatweets12, https://www.instagram.com/p/C9USAMcC5Ft/?img_index=1 (accessed on 11 August 2024).

Shiatweets12 is a popular account with nearly half a million followers (489,000 as of August 17, 2024) that mostly posts videos and screenshots of tweets. One of their short videos, titled “From Ghadir to Ashura,” (Figure 1) initially depicts one individual raising the hand of another, accompanied by Arabic audio and English subtitles that state, “For whomever I am his leader, ʿAlī is his leader.”[33] The video transitions to a scene where the raised hand becomes bloodied, and the person who raised the hand falls. The accompanying text shifts the viewer to the events of the Day of ʿĀshūrāʾ. The video concludes with the caption “50 years in one scene.” In this video, the first segment references the event of Ghadīr Khumm, where the Prophet Muḥammad is said to have declared ʿAlī as his successor by raising ʿAlī's hand and reciting the aforementioned text.[34] The latter segment portrays the bloodied and fallen hand of Imam Ḥusayn during the Battle of Karbalāʾ, accompanied by his plea to the enemy, “Am I not the son of your prophet’s daughter? So why do you fight me?” to which the response was, “We fight you because of our hatred for your father (ʿAlī).” Thus, the video illustrates how the neglect of the Ghadīr Khumm led to the events of Karbalāʾ. The phrase “50 years in one scene” particularly emphasizes the connection between these historical events and highlights the interpretive narrative of their significance.

A similar interpretative approach is evident in other Instagram posts as well. Both mentioned aspects are present in the video extract of Sayed Ammar Nakshawani’s lecture (https://www.instagram.com/p/C8nIFBqOzys/, accessed on 13 August 2024), where he narrates that the result of Ghadīr Khumm only brought Imams Bāqir, Ṣādiq, Kāẓim, and others, while Saqīfah brought Yazīd. He further explains that if Abū Bakr had the authority to appoint a successor, why wouldn’t Muʿāwiyah have the same authority? Saqīfah established the criteria that anyone could have a chance to be a leader, regardless of qualifications. Because of Saqīfah, all one needed was the right best friend, the right companions, the right backers, and enough hatred of ʿAlī ibn Abī Ṭālib (this corresponds well with the moment depicted in Figure 1, where people tell Ḥusayn that they fight him because of their hatred for his father ʿAlī). Only 50 years after the Prophet’s death, Yazīd sat in the Prophet’s chair. Since the Muslims said, “We should choose our leaders,” Yazīd could argue, “Don’t say yes, it was wrong because my father chose me. ʿUmar was chosen by Abū Bakr, so why can’t my father choose me?” Both Ghadīr and the 50-year timeline are referenced here alongside the events of Saqīfah, where the election of Abū Bakr as the first caliph took place.[35] Shiʿis consider those elections illegitimate and believe that ʿAlī's refusal to recognize the results led to ʿUmar’s attack on the house of ʿAlī and Fāṭima – a narrative frequently used on Shiʿi Instagram, which will be discussed further.[36] Other historical events that Sayed Ammar Nakshawani referred to in this video are Abū Bakr’s appointment of ʿUmar as caliph, a generally accepted fact by Sunni Muslims due to their belief in ʿUmar’s service to Islam, and similar actions by Muʿāwiyah (the appointment of his son Yazīd) which are sometimes viewed negatively due to Yazīd’s actions and lifestyle.[37] These historical events are widely examined in Shiʿi historiography.[38]

In another video (https://www.instagram.com/p/C9ddZ8gC612/, accessed on 13 August 2024), Sayed Ammar Nakshawani argues that the month of Muharram demonstrates how Saqīfah produced people who have no regard for the family of the Prophet, while Ghadīr produced people who, “even if the world is enjoying themselves,” cannot abandon the Prophet’s family. The video was recorded and posted during Euro 2024, and the speaker notes that if this were any other month, “our thoughts tonight would be on football – I’m not missing it; my life revolves around it – except when it’s ʿAbbās, when it’s Ḥusayn.” He further explains that, for Shiʿis, Islam was completed because of the Prophet’s family. He argues that many people (referring mainly to non-Shiʿis) will not mention Imam Ḥusayn during this month, while Shiʿis are the only group that, every year, does not neglect the Prophet’s grandson. In this context, Nakshawani uses these historical events not only to illustrate their impact on subsequent events but also to place them in a much broader global context, linking Saqīfah to the emergence of Sunni Muslims and Ghadīr to Shiʿi Muslims. A similar line of thought can be observed in other scholarly research as well.[39] Most Shiʿis believe that Islamic history has been tainted by the divisions caused at Saqīfah, which led to several wars among Muslims, mainly involving the Companions of the Prophet. These divisions and contentions ultimately led to the tragic killings in Karbalāʾ and the imprisonment of survivors in Shām (Syria).[40]

As mentioned above, the story of ʿUmar’s attack on the house of ʿAlī and Fāṭima, along with its further complications, is often used on Instagram to evoke a visceral emotional response by highlighting the suffering endured by ʿAlī and Fāṭima, and later by Ḥusayn and Zaynab. This narrative also strongly reinforces the concept of the inheritance of martyrdom. Various sources (mainly Shiʿi) indicate that, alarmed by Fāṭima’s opposition to Abū Bakr’s election, ʿUmar threatened to burn her house down, along with its inhabitants, if her husband did not acknowledge Abū Bakr as caliph.[41] During these events, Fāṭima was reportedly squeezed between two doors, leading to a broken rib and the miscarriage of her son Muḥsin.[42] Given the theological and historical implications of these events, this discussion will not engage with the question of their historical authenticity. Instead, it will focus on how Instagram users draw parallels between this event and the events of Karbalāʾ.

One of the posts of Shiatweets12 analyzed here (Figure 2) consists of six frames featuring tweets, accompanied by the famous Shiʿi mourning chant “Ḥabībi Ḥusayn” (Beloved Ḥusayn). All the tweets in this post were made by different individuals. The first tweet features a ḥadīth from the Prophet Muḥammad: “Ḥusayn is from me and I am from Ḥusayn. Allah loves those who love Ḥusayn,”[43] followed by the inscription, “but what they did with his Ḥusayn and his family.” The accompanying image contrasts two scenes: on the left, the Prophet Muḥammad is shown in sujūd (prostration) with little Ḥasan and Ḥusayn playing around him and climbing on his back, reflecting multiple stories about how they played around the Prophet while he prayed.[44] On the right, Imam Ḥusayn is depicted on a horse, wounded and bloody, with arrows piercing his body during the final moments of his life at the Battle of Karbalāʾ. This powerful imagery evokes a sense of “embodied mourning,” wherein bodily sensations, emotional intensity, and spatial associations function as participatory, materially grounded processes that authenticate religious experience.[45] The visceral and traumatic nature of the depiction heightens its emotional impact, thereby reinforcing its perceived authenticity.

The next five tweets draw explicit parallels between the attack on Fāṭima’s house and the events of ʿĀshūrāʾ (the Battle of Karbalāʾ). They claim that Fāṭima was killed in front of her children (little Ḥasan and Ḥusayn), while in Karbalāʾ, children were killed in front of their mothers (such as the 6-month-old ʿAlī al-ʿAṣghar, the 13-year-old Al-Qāsim ibn al-Ḥasan, the 7-year-old Muḥammad b. Abī Saʿīd, and others). Other parallels include Fāṭima’s broken ribs and Ḥusayn’s broken ribs (or back in another tweet), and the flames burning Fāṭima’s door and those burning the tents of Ḥusayn’s women in Karbalāʾ. One tweet states, “ʿAṣghar ended the battle in Karbalāʾ, which was started by Muḥsin,” highlighting the narrative of the continued oppression of the Prophet’s family and the inheritance of martyrdom, even among children. Similar narratives can be observed in other posts too. For example, a post by shiahwallpapers (https://www.instagram.com/p/CKGiZQIj4hs/, accessed on August 13, 2024) claims that Saqīfah is the foundation of Karbalāʾ and that “we will never forget the burning door,” referring to the doors of Fāṭima’s house, burned by ʿUmar.

While many accounts often use images or videos created by others, some accounts generate original content for their posts. Instagram provides a space for Shiʿi Muslims to explore and express their identity in visually creative ways. Accounts dedicated to Shiʿi art, calligraphy, and poetry showcase the rich cultural heritage of the Shiʿi community. These creative expressions frequently merge traditional religious themes with contemporary aesthetics, appealing to a broader audience both within and outside the Shiʿi community.

A common element among the analyzed posts is the use of specific emojis and visual elements to convey sorrow and sadness for Imam Ḥusayn and other martyrs. For instance, the Broken Heart ( ) emoji symbolizes the heartbreak and anguish felt over the tragedy of Karbalāʾ, while the Crying Face (

) emoji symbolizes the heartbreak and anguish felt over the tragedy of Karbalāʾ, while the Crying Face ( ) emoji is often used by commentators to express deep sorrow and grief. Visual elements typically depict the Battle of Karbalāʾ or other episodes of the oppression of Ahl al-Bayt, showing scenes such as Imam Ḥusayn injured and covered in blood, the burning door of Fāṭima’s house, or the burning tents in Karbalāʾ. This reflects how Shiʿis pursue a lifelong engagement with the embodied cultural memory of Karbalāʾ through the use of familiar symbolic forms that evoke and sustain affective connections to the past. Such practices function as “continuing bonds,” wherein relationships with the martyrs are not severed but rather reshaped and actively maintained, much like in processes of grief where the deceased are remembered, honored, and kept present in lived experience.[46]

) emoji is often used by commentators to express deep sorrow and grief. Visual elements typically depict the Battle of Karbalāʾ or other episodes of the oppression of Ahl al-Bayt, showing scenes such as Imam Ḥusayn injured and covered in blood, the burning door of Fāṭima’s house, or the burning tents in Karbalāʾ. This reflects how Shiʿis pursue a lifelong engagement with the embodied cultural memory of Karbalāʾ through the use of familiar symbolic forms that evoke and sustain affective connections to the past. Such practices function as “continuing bonds,” wherein relationships with the martyrs are not severed but rather reshaped and actively maintained, much like in processes of grief where the deceased are remembered, honored, and kept present in lived experience.[46]

Therefore, such posts are almost always accompanied by heartrending details from Karbalāʾ or other historical events. These elements work together to create a powerful emotional response, connecting viewers with the grief and mourning that are central to the remembrance of Imam Ḥusayn and the events of Karbalāʾ. Additionally, the description of these narratives of inheritance of martyrdom is particularly poignant, emphasizing that martyrdom is not limited to one individual but is a legacy passed down through generations.

6 Conclusions

The concept of the “inheritance of martyrdom” holds an important place in Shiʿi Islam, rooted in the historical and theological narratives surrounding the Ahl al-Bayt. This doctrine reflects the belief that the sacrifice and martyrdom experienced by the Prophet’s family are not isolated incidents but are part of a divine continuum. The martyrdom of Imam Ḥusayn, the grandson of the Prophet, at the Battle of Karbalāʾ in 680 CE, epitomizes this legacy. Analyzed posts show that martyrdom is not always viewed as merely a historical event but an inherited responsibility that continued through subsequent generations. This belief underscores that each Imam, beginning with ʿAlī ibn Abī Ṭālib and continuing through his descendants, embodies the principles of sacrifice and resistance against tyranny. The suffering endured by these figures is perceived as a continuation of the prophetic mission, reinforcing their role as the legitimate spiritual and temporal leaders of the Shiʿi community. This inheritance of martyrdom thus signifies a continuous and collective struggle for righteousness, transcending individual acts of martyrdom to become a defining feature of the Shiʿi identity.

Instagram became a significant platform for the expression of martyrdom narratives in Shiʿi Islam. It provides a space where these stories can be shared, commemorated, and kept alive in the collective memory of the global Shiʿi community, fostering a sense of solidarity and continuity across generations and geographies. Similarly, as Pennington observes in her analysis of Instagram posts during the 2019 Eid al-Aḍḥā celebrations, the platform facilitates performances of piety that are deliberately crafted to be visually inviting and emotionally resonant. These images not only celebrate religious identity but also seek to forge connections among Muslims, regardless of physical distance.[47] What emerges is a sense that the Muslim community on Instagram, Shiʿi or otherwise, is actively engaged in creating a transnational network of belonging and shared affect, where digital rituals and visual culture serve to strengthen communal bonds and spiritual presence.

In this study, I approach “inheritance” not merely as a metaphor describing how martyrdom passes through generations, but as a hermeneutic category that organizes interpretation itself. It allows us to understand events like Karbalāʾ not as isolated tragedies but as expressions of a divine, continuous legacy of resistance and sanctified suffering. Therefore, this article focused on how Instagram posts serve to connect and reflect various historical events from Early Shiʿi Islamic History. Investigation of these social media representations presents how contemporary digital platforms contribute to the ongoing commemoration and interpretation of the martyrdom of Imam Ḥusayn and its historical context. On Instagram, the concept of inheritance of martyrdom is vividly represented through various forms of digital content. Instagram posts about the events of Karbalāʾ use a combination of visual, textual, and interactive elements to evoke compassion and deepen understanding of Imam Ḥusayn’s martyrdom. Rather than viewing this as a rupture from traditional forms of mourning or remembrance, it can be understood as a translation from one symbolic milieu to another. As Sparey suggests, incorporating digital technologies into pre-digital ritual practices does not constitute a radical break, but rather a movement of meaning across symbolic registers – each with its own spiritually resonant terms of reference.[48] In this sense, the lessons of Karbalāʾ are not simply digitized but rearticulated within a contemporary aesthetic and affective framework. In our case, these events are also historically (re)interpreted and connected to other events of the past. Furthermore, this process aligns with what Ali terms rememory – an active, affective process through which past experiences are not merely recalled but reconstructed in the present.[49] Instagram becomes a space where rememory is performed through visuals and captions that invite recognition, relatability, and conviction, enabling users to embody and reaffirm Shiʿi identity in digital environments that are emotionally and spiritually charged. Assuming that devotional emotion is not dematerialized online but rearticulated through new forms of sensory and affective participation, acts such as posting, sharing, or commenting extend embodied mourning into a digital sensorium, transforming Instagram into a transnational majlis.

By depicting the tragedy and sacrifice of Karbalāʾ through powerful imagery, emotive language, and educational narratives, these posts aim to connect with viewers on an emotional level and encourage a reflective and empathetic response. Art and imagery shared on Instagram often draw parallels between different episodes of suffering within the Ahl al-Bayt, such as linking Fāṭima’s suffering to that of her descendants. Visuals typically depict sensitive moments, such as Ḥusayn being bloodied and injured or carrying the body of his six-month-old son, and employ somber color palettes and symbolic elements like broken hearts and tears to evoke the emotional and spiritual weight of these narratives. These artistic representations are intended to resonate with viewers on both a personal and communal level, reinforcing the ongoing significance of martyrdom in Shiʿi Islam. Hirschkind’s notion of “ethical listening” provides a productive framework for understanding how digital audiences cultivate pious affect through mediated forms.[50] On Instagram, this “listening” becomes multimodal “ethical viewing” where visual, textual, and sonic cues reconstitute devotional sensitivity. The inheritance of martyrdom, therefore, is sustained through digital practices that train perception, emotion, and empathy as moral faculties.

Images depicting the sufferings of the Prophet’s family are generally comprehensible to all viewers to some extent. However, despite their broader emotional appeal, the analyzed images and Instagram posts are predominantly tailored for a Shiʿi audience. They reference historical narratives that hold deep significance within Shiʿism and are primarily accepted within its theological framework.[51] As a result, these representations often remain largely inaccessible to non-Muslim viewers, who may struggle to identify the figures portrayed or understand the historical events being referenced. Even non-Shiʿi Muslim viewers, while recognizing the personalities depicted, may not fully grasp the narrative details or may interpret the events differently based on their own perspectives and theological beliefs. Within the Shiʿi community itself, although these posts are created mainly by Twelver Shiʿis, they naturally extend their reach to other Shiʿi groups as well. This inclusivity is largely due to the fact that the events depicted, often drawn from the early history of Shiʿi Islam, particularly the first century of the hijra, are widely acknowledged across various Shiʿi denominations. Regardless of sectarian differences, most Shiʿis recognize and resonate with the events described in these posts, highlighting the shared historical and emotional heritage that unites different Shiʿi communities despite doctrinal variations.

The representation of the inheritance of martyrdom on Instagram highlights the dynamic interplay between traditional Shiʿi beliefs and contemporary digital expression. By using visual art, emojis, and narrative content, these posts maintain the emotional and spiritual significance of the Ahl al-Bayt’s sacrifices, ensuring that the legacy of martyrdom remains a vital and resonant part of Shiʿi identity.

-

Funding information: Publication of this article has been made possible through the generous support of the Academy for Islam in Research and Society (AIWG) at the Goethe University in Frankfurt. The AIWG is funded by the Federal Ministry of Research, Technology and Space (BMFTR).

-

Author contribution: The author confirms the sole responsibility for the conception of the study, presented results, and manuscript preparation.

-

Conflict of interest: Author states no conflict of interest.

References

Ahlul Bayt News Agency. “Sayings of Imam Sajjad on Karbala Tragedy.” ABNA English, 29 July 2024. Accessed 6 July 2025. https://en.abna24.com/news/1475056/Sayings-of-Imam-Sajjad-on-Karbala-Tragedy.Search in Google Scholar

Ali, Zahra A. “Conjuring Karbala Online and Offline: Experiences of the ‘Authentic’ in Shiʿa Majālis.” Journal of Muslims in Europe 11:1 (2022), 124–45. 10.1163/22117954-bja10050.Search in Google Scholar

Ali, Zahra A. and Thijl Sunier. “Seeking Authentic Listening Experiences in Shiʿism: Online and Offline Intersections of Majlis Practices.” In Making Islam Work, 189–212. Leiden: Brill, 2023. 10.1163/9789004684928_007.Search in Google Scholar

al-Ṭabarī. The History of al-Ṭabarī (Taʾrīkh al-rusul wa’l-mulūk), Volume X: The Conquest of Arabia, translated by Fred M. Donner. New York: State University of New York Press, 1993.Search in Google Scholar

Banks, Marcus. Visual Methods in Social Research. London: SAGE Publications, 2001.10.4135/9780857020284Search in Google Scholar

Bunt, Gary R. Islamic Algorithms: Online Influence in the Muslim Metaverse. London: Bloomsbury Publishing, 2024.10.5040/9781350418295Search in Google Scholar

Campbell, Heidi A. “Surveying Theoretical Approaches within Digital Religion Studies.” New Media & Society 19:1 (2017), 15–24. 10.1177/1461444816649912.Search in Google Scholar

Cook, David. Martyrdom in Islam. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2007.10.1017/CBO9780511810688Search in Google Scholar

Eisenlohr, Patrick. “Media, Citizenship, and Religious Mobilization: The Muharram Awareness Campaign in Mumbai.” The Journal of Asian Studies 74:3 (2015), 687–710. 10.1017/S0021911815000534.Search in Google Scholar

Fakhr-Rohani, Muhammad-Reza. The Shiʿi Islamic Martyrdom Narratives of Imam al-Ḥusayn. Newcastle upon Tyne: Cambridge Scholars Publishing, 2023.Search in Google Scholar

Friedman, Jonathan. “Armchair Anthropology in the Cyber Age.” Savage Minds (now Anthrodendum), 19 May 2005. https://savageminds.org/2005/05/19/armchair-anthropology-in-the-cyber-age/.Search in Google Scholar

Frissen, Thomas, Elke Ichau, Kristof Boghe, and Leen d’Haenens. “#Muslims? Instagram, Visual Culture and the Mediatization of Muslim Religiosity: Explorative Analysis of Visual and Semantic Content on Instagram.” In European Muslims and New Media, edited by M. Kayıkcı and L. d’Haenens. Leuven: Leuven University Press, 2017.10.2307/j.ctt1whm9bx.9Search in Google Scholar

Fuchs, Thomas. “Presence in Absence: The Ambiguous Phenomenology of Grief.” Phenomenology and the Cognitive Sciences 17 (2018), 43–63.10.1007/s11097-017-9506-2Search in Google Scholar

Hasan, Farah. “Muslim Instagram: Eternal Youthfulness and Cultivating Deen.” Religions 13 (2022), 658. 10.3390/rel13070658.Search in Google Scholar

Hirschkind, Charles. “The Ethics of Listening: Cassette-Sermon Audition in Contemporary Egypt.” American Ethnologist 28 (2001), 623–49.10.1525/ae.2001.28.3.623Search in Google Scholar

Ibn Ṭāwūs, Sayyid Raḍī al-Dīn ʿAlī ibn Mūsā. Al-Luhūf ʿalā qatlā ṭaffūf (Sighs of Sorrow), translated by Athar Ḥusayn Rizvī, edited by Ḥamīd Farnāgh. Tehran: Naba Cultural Organization, 2006.Search in Google Scholar

Kalinock, Sabine. “Going on Pilgrimage Online: The Representation of Twelver-Shiʿi in the Internet.” Heidelberg Journal of Religions on the Internet 2:1 (2006), 6–23. 10.11588/rel.2006.1.373.Search in Google Scholar

Khel, Muḥammad Nazeer Kaka. “Succession to Rule in Early Islam.” Islamic Studies 24:1 (1985), 13–28.Search in Google Scholar

Khetia, Vinay. Fatima as a Motif of Contention and Suffering in Islamic Sources. Master’s Thesis. Concordia University, 2013.Search in Google Scholar

Lebni, Javad Yoosefi, Arash Ziapour, Nafiul Mehedi, and Seyed Fahim Irandoost. “The Role of Clerics in Confronting the COVID-19 Crisis in Iran.” Journal of Religion and Health 60 (2021), 2387–94.10.1007/s10943-021-01295-6Search in Google Scholar

Madelung, Wilferd. The Succession to Muhammad: A Study of the Early Caliphate. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1997.10.1017/CBO9780511582042Search in Google Scholar

Mollabashi, Yavar Alipour, Shahnaz Hashemi, and Ali Jafari. “The Role of Instagram in the Reproduction of Religious Culture amongst Iranian Youths.” Islam and Social Studies 30 (2020), 157–90.Search in Google Scholar

Pennington, Rosemary. “Seeing a Global Islam?: Eid al-Adha on Instagram.” In Cyber Muslims: Mapping Islamic Digital Media in the Internet Age, edited by Robert Rozehnal, 176–88. London: Bloomsbury Publishing, 2022.10.5040/9781350233737.0020Search in Google Scholar

Qazwini, Muhammad Husayni. Imamate and Caliphate – An Islamic Perspective, translated by Morteza Karimi. Tehran: Mousa Kalantari Cultural Institute, 2021.Search in Google Scholar

Qutbuddin, Tahera. “Fatima al-Zahraʾ bint Muhammad (ca. 12 before Hijra–11/ca. 610–632).” In Medieval Islamic Civilization: An Encyclopedia, edited by Josef W. Meri, 248–50. London: Routledge, 2006.Search in Google Scholar

Rahimi, Babak and Mohsen Amin. “Digital Technology and Pilgrimage: Shiʿi Rituals of Arbaʿin in Iraq.” Journal of Religion, Media and Digital Culture 9:1 (2020), 82–106. 10.1163/21659214-bja10006.Search in Google Scholar

Rahimi, Babak. “The Instagram Cleric: History, Technicity, and Shīʿī Iranian Jurists in the Age of Social Media.” In Cyber Muslims: Mapping Islamic Digital Media in the Internet Age, edited by Robert Rozehnal, 220–36. London: Bloomsbury Publishing, 2022.10.5040/9781350233737.0024Search in Google Scholar

Ruffle, Karen G. “Gazing in the Eyes of the Martyrs: Four Theories of South Asian Shiʿi Visuality.” Journal of Material Cultures in the Muslim World 1:1–2 (2021), 268–90. 10.1163/26666286-12340012.Search in Google Scholar

Saqifa and Beyond. Hubeali.com. Accessed 14 August 2024. https://hubeali.com/article/saqifa-and-beyond/.Search in Google Scholar

Shariati, Ali. Martyrdom: Arise and Bear Witness, translated by Ali Asghar Ghassemy. Tehran: The Ministry of Islamic Guidance, 1981. https://archive.org/details/martyrdom-arise-and-bear-witness_202310/page/26/mode/2up.Search in Google Scholar

Sparey, Thomas Rhys. “#IAMHUSSEINI: Television and Mourning during the COVID-19 Pandemic.” Religion 52:2 (2022), 284–305. 10.1080/0048721X.2022.2053038.Search in Google Scholar

Sparey, Thomas Rhys. “Livestreaming Islamic Arts: Digitisation as Translation in Shiʿi Depictions of Karbalāʾ.” Translation Matters 5:1 (2023), 29–56.10.21747/21844585/tm5_1a2Search in Google Scholar

Taherifard, Alireza. “Shiʿi Clerics, Holy Sites, and the Online Visual Culture of the Revolutionary Youth in Iran.” Religions 13:6 (2022), 542. 10.3390/rel13060542.Search in Google Scholar

Tahiiev, Akif. “Book Review of The Shiʿi Islamic Martyrdom Narratives of Imam al-Ḥusayn (by Muhammad-Reza Fakhr-Rohani).” American Journal of Islam and Society 40 (2023), 184–90. 10.35632/ajis.v40i3-4.3298.Search in Google Scholar

Tahiiev, Akif. “Digital Shiʿism and Ethical Dilemmas in the Study of Digital Religious Minorities: Methodological Reflections.” Research Ethics, forthcoming.Search in Google Scholar

Tahiiev, Akif. “Impact of the Events of Saqifa on the Formation of Differences between the Islamic Sunni and Shia Tradition.” Journal of Al-Tamaddun 18 (2023), 161–7. 10.22452/JAT.vol18no1.13.Search in Google Scholar

Tahiiev, Akif. “The Lady of Heaven and Representations of Early Shiʿi Islam in Films and TV Series.” Journal for Religion, Film and Media 11:2 (2025).Search in Google Scholar

Tahiiev, Akif. “Live After Death: Shiʿi Martyrdom Narratives on Instagram.” Journal for Religion, Film and Media 12:1 (2026).Search in Google Scholar

Tahiiev, Akif and Dmytro Lukianov. “The Role of the Events of Fadak in the Formation of Differences between the Islamic Sunni and Shia Laws.” Islamic Inquiries 1 (2022), 61–74. 10.22034/IS.2021.137403.Search in Google Scholar

Wright, Terence. The Photography Handbook. London: Routledge, 1999.10.4324/9780203295243Search in Google Scholar

Zaid, Bouziane, Jana Fedtke, Don Donghee Shin, Abdelmalek El Kadoussi, and Mohammed Ibahrine. “Digital Islam and Muslim Millennials: How Social Media Influencers Reimagine Religious Authority and Islamic Practices.” Religions 13 (2022), 335. 10.3390/rel13040335.Search in Google Scholar

© 2025 the author(s), published by De Gruyter

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Special issue: Mathematically Modeling Early Christian Literature: Theories, Methods and Future Directions, edited by Erich Benjamin Pracht (Aarhus University, Denmark)

- Mathematically Modeling Early Christian Literature: Theories, Methods, and Future Directions

- Comparing and Assessing Statistical Distance Metrics within the Christian Apostle Paul’s Letters

- Something to Do with Paying Attention: A Review of Transformer-based Deep Neural Networks for Text Classification in Digital Humanities and New Testament Studies

- Paul’s Style and the Problem of the Pastoral Letters: Assessing Statistical Models of Description and Inference

- Seek First the Kingdom of Cooperation: Testing the Applicability of Morality-as-Cooperation Theory to the Sermon on the Mount

- Modelling the Semantic Landscape of Angels in Augustine of Hippo

- Was the Resurrection a Conspiracy? A New Mathematical Approach

- Special issue: Reading Literature as Theology in Islam, edited by Claire Gallien (Cambridge Muslim College and Cambridge University) and Easa Saad (University of Oxford)

- Reading Literature as Theology in Islam. An Introduction and Two Case Studies: al-Thaʿālibī and Ḥāfiẓ

- Human Understanding and God-talk in Jāmī and Beyond

- Was That Layla’s Fire?: Metonymy, Metaphor, and Mannerism in the Poetry of Ibn al-Fāriḍ

- Divine Immanence and Transcendent Love: Epistemological Insights from Sixteenth-Century Kurdish Theology

- Regional and Vernacular Expressions of Shi‘i Theology: The Prophet and the Imam in Satpanth Ismaili Ginans

- The Fragrant Secret: Language and Universalism in Muusaa Ka’s The Wolofal Takhmīs

- Love as the Warp and Weft of Creation: The Theological Aesthetics of Muhammad Iqbal and Rabindranath Tagore

- Decoding Muslim Cultural Code: Oral Poetic Tradition of the Jbala (Northern Morocco)

- Research Articles

- Mortality Reimagined: Going through Deleuze’s Encounter with Death

- When God was a Woman꞉ From the Phocaean Cult of Athena to Parmenides’ Ontology

- Patrons, Students, Intellectuals, and Martyrs: Women in Origen’s Life and Eusebius’ Biography

- African Initiated Churches and Ecological Sustainability: An Empirical Exploration

- Randomness in Nature and Divine Providence: An Open Theological Perspective

- Women Deacons in the Sacrament of Holy Orders

- The Governmentality of Self and Others: Cases of Homosexual Clergy in the Communist Poland

- “No Church in the Wild”? Hip Hop and Inductive Theology

- Inheritance of Martyrdom: Digital Interpretations on Instagram

Articles in the same Issue

- Special issue: Mathematically Modeling Early Christian Literature: Theories, Methods and Future Directions, edited by Erich Benjamin Pracht (Aarhus University, Denmark)

- Mathematically Modeling Early Christian Literature: Theories, Methods, and Future Directions

- Comparing and Assessing Statistical Distance Metrics within the Christian Apostle Paul’s Letters

- Something to Do with Paying Attention: A Review of Transformer-based Deep Neural Networks for Text Classification in Digital Humanities and New Testament Studies

- Paul’s Style and the Problem of the Pastoral Letters: Assessing Statistical Models of Description and Inference

- Seek First the Kingdom of Cooperation: Testing the Applicability of Morality-as-Cooperation Theory to the Sermon on the Mount

- Modelling the Semantic Landscape of Angels in Augustine of Hippo

- Was the Resurrection a Conspiracy? A New Mathematical Approach

- Special issue: Reading Literature as Theology in Islam, edited by Claire Gallien (Cambridge Muslim College and Cambridge University) and Easa Saad (University of Oxford)

- Reading Literature as Theology in Islam. An Introduction and Two Case Studies: al-Thaʿālibī and Ḥāfiẓ

- Human Understanding and God-talk in Jāmī and Beyond

- Was That Layla’s Fire?: Metonymy, Metaphor, and Mannerism in the Poetry of Ibn al-Fāriḍ

- Divine Immanence and Transcendent Love: Epistemological Insights from Sixteenth-Century Kurdish Theology

- Regional and Vernacular Expressions of Shi‘i Theology: The Prophet and the Imam in Satpanth Ismaili Ginans

- The Fragrant Secret: Language and Universalism in Muusaa Ka’s The Wolofal Takhmīs

- Love as the Warp and Weft of Creation: The Theological Aesthetics of Muhammad Iqbal and Rabindranath Tagore

- Decoding Muslim Cultural Code: Oral Poetic Tradition of the Jbala (Northern Morocco)

- Research Articles

- Mortality Reimagined: Going through Deleuze’s Encounter with Death

- When God was a Woman꞉ From the Phocaean Cult of Athena to Parmenides’ Ontology

- Patrons, Students, Intellectuals, and Martyrs: Women in Origen’s Life and Eusebius’ Biography

- African Initiated Churches and Ecological Sustainability: An Empirical Exploration

- Randomness in Nature and Divine Providence: An Open Theological Perspective

- Women Deacons in the Sacrament of Holy Orders

- The Governmentality of Self and Others: Cases of Homosexual Clergy in the Communist Poland

- “No Church in the Wild”? Hip Hop and Inductive Theology

- Inheritance of Martyrdom: Digital Interpretations on Instagram