Abstract

This explorative study examines the applicability of Morality-as-Cooperation (MAC) theory to early Christian texts, using the Sermon on the Mount as a test case. MAC theory posits seven universal moral domains – family values, group loyalty, reciprocity, heroism, deference, fairness, and property rights – as evolutionary solutions to cooperative challenges. Five participants annotated 102 preselected Koine Greek text units from the Sermon using ATLAS.ti, classifying them according to MAC categories. The data were analyzed computationally. The results indicate that the moral domains proposed by MAC theory are widely represented in the Sermon, with reciprocity and deference emerging as the most prominent. However, substantial divergence among annotators’ interpretations suggests that the metaphorical and ambiguous nature of historical religious texts may contribute to interpretive variability. Addressing this issue will be essential before annotation-based methods can be reliably integrated with machine-learning models in broader studies of early Christian textual corpora.

1 Introduction

The theory of Morality-as-Cooperation (MAC) by Oliver Scott Curry and his colleagues suggests that human moral behavior, borne out of a long evolutionary process, can be divided into seven universal moral domains. These domains are: (1) family values, (2) group loyalty, (3) reciprocity, (4) “hawkish” displays of dominance/heroism, (5) “doveish” displays of deference, (6) fairness, and (7) property rights. This article explores the applicability of MAC theory to an early Christian ethical text, the Sermon on the Mount (Gospel of Matthew 5–7).

This article has three interwoven objectives: (1) to assess whether the moral domains proposed by MAC theory are sufficiently represented and recognizable in the Sermon to justify a broader study combining the theory with a larger corpus of early Christian texts, (2) to determine whether MAC theory has the potential to provide new insights into interpretations of the Sermon’s morality, and (3) to identify the methodological considerations that must be addressed before applying similar analyses to other early Christian texts.

To achieve these objectives, a combined qualitative and quantitative methodology was employed. Five participants annotated the Sermon on the Mount in its Koine Greek form using the qualitative data analysis software ATLAS.ti. The annotators, including all the authors of this article, were familiar with at least the basics of MAC theory and had expertise in biblical studies. Their task was to independently classify each preselected quotation according to the moral domains. The annotation data were then analyzed computationally in alignment with the objectives.

The results indicate that the moral domains proposed by MAC theory are widely represented in the Sermon. The vast majority of its moral teachings align with the theory’s seven domains, supporting the idea that early Christian morality can be analyzed through the lens of cooperative strategies. This suggests that MAC theory provides a promising explanatory framework for understanding the Sermon’s moral content and, by extension, other early Christian ethical texts as expressions of evolutionarily rooted responses to cooperative challenges.

The Sermon’s moral teachings are diverse, multifaceted, and often complex. All seven MAC domains are present, with reciprocity and deference emerging as the most salient categories. The Sermon frequently addresses the importance of reciprocal cooperation and submissive behavior in situations of potential resource conflict. However, these teachings often involve a theological dimension: reciprocity is frequently framed as a relationship between the individual and God, while submission is presented not as yielding to another human’s authority but as deference to divine will or adherence to collective moral values.

One of the most striking outcomes is the substantial divergence among the annotators’ interpretations. These differences stemmed from systematic, personal interpretive strategies rather than inconsistencies in the annotation process. They concern both the relative emphasis given to different moral domains and the specific domain classifications assigned to individual text segments. This suggests that many of the Sermon’s moral statements may be inherently ambiguous, allowing for multiple plausible interpretations. Such ambiguity may, in part, help explain the Sermon’s enduring cultural and theological significance.

This interpretive variability presents a key methodological challenge that must be accounted for in future studies applying similar annotation-based analyses to larger text corpora. Current machine-learning models allow for the computational study of massive textual datasets, but they rely on human-annotated training material that must be sufficiently consistent to produce reliable outcomes. If annotation is to contribute to the development of a stable moral vocabulary for early Christian texts, achieving a higher degree of agreement among annotators will be essential.

This article begins with an introduction to the Morality-as-Cooperation (MAC) theory as an evolutionary framework for understanding morality. This is followed by an introduction to the Sermon of the Mount in its historical and literary setting, and a summary description of the previous research conducted on this pivotal text, with examples of studies that apply cognitive and evolutionary approaches. To our knowledge, no previous study has applied either MAC theory or annotation-based methods to the Sermon. The methodology section begins by describing the experimental design and annotation process. The following chapter provides a detailed account of the computational methods used to analyze the annotation data. This is then followed by a presentation of the results. Finally, the discussion examines the experimental process and results, with particular emphasis on potential factors underlying annotator divergence and methodological recommendations for future studies.

2 Theoretical Background: Morality-as-Cooperation (MAC)

2.1 Evolutionary Views of Morality

Research has habitually tied morality to cooperation, regardless of other differences of opinion.[1] The evolutionary approach on morality builds on the idea that during the evolution of life, natural selection has favored cooperative genes. This has enabled the emergence of a wide range of phenomena, from cells and multicellular organisms to intensely cooperating human societies. With primates having over 50 million years of social history, and the hominin lineage some 6 million years, there is a long evolutionary period of intensifying genetic disposition toward cooperation.[2] The human capacity for language and intelligence (the “cognitive niche”) has also led to the birth of large cooperative societies with a wide range of cultural solutions that strengthen cooperation such as norms, rules, and various monitoring technologies.[3] The strong evolutionary basis of cooperation does not override “genetic selfishness”; instead, cooperation enhances genetic fitness by reducing fights over resources as well as other harmful behaviors that can lead to reduced payoff genetically.[4]

An important predecessor and discussion partner of MAC theory is the Moral Foundations Theory (MFT) by Jonathan Haidt et al.[5] The MFT originally distinguished five (later six) moral foundations that underlie human moral decisions and behavior. The categories were picked from ones that recur in the secondary literature on morality and have a counterpart in evolutionary theory.[6] The authors also compiled a Moral Foundations Questionnaire to test the hypothesis on individuals.[7] Although the project described in the article at hand focuses on MAC theory alone, a future project should compare MAC- and MFT-based annotations of early Judeo-Christian texts. Results concerning the category of sanctity/purity, lacking in MAC but present in MFT, would be of particular interest given the presence of the theme in religious literature.[8]

2.2 MAC Makes the Study of Morality More Scientific

MAC theory builds on its predecessors by focusing on morality as cooperation, using evolutionary psychology to understand the basis of morality, and by combining these concepts with mathematical and evolutionary game theory.[9] The combination of suggested moral domains in MAC, however, is unique and intended to be comprehensive. The theory has undergone testing to ensure that the categories MAC suggests are relevant to morality and form distinct moral domains.[10] According to Curry et al., the theory can finally “transform [the commonplace of morality as linked to cooperation] into a precise and comprehensive theory, capable of making specific testable predictions about the nature of morality.”[11]

In terms of game-theoretical adaptations, the explanatory power of MAC builds on evolutionary game theory, which explains how cooperative behaviors and solutions have emerged and persisted in human populations over time.[12] Ultimately, evolutionary game theory seeks to discover evolutionarily stable strategies; ESS denotes “an equilibrium in the population such that cannot be defeated by any competing strategy.”[13] MAC theory also applies mathematical (classical) game theory to categorize cooperative behaviors in terms of the main division between competitive zero-sum and cooperative non-zero-sum games.[14] Competitive zero-sum interactions have a winner and a loser; one person’s gain is another’s loss. Cooperative non-zero-sum interactions, however, can have two winners; they can be win–win situations. The best-known examples of these include cooperative challenges, such as the prisoner’s dilemma, the assurance game, public goods games, the bargaining problem, tragedies of the commons, the stag hunt game, and ultimatum games.[15] Curry et al. predict that since the problems of cooperation are varied, so will their solutions, which makes for different types/domains of morality or moral values.[16]

2.3 What is Morality According to MAC?

It follows then that morality, according to MAC theory, is “a collection of instincts, intuitions, ideas, and institutions”[17] that have developed in humans and by humans to solve problems of cooperation. Morality involves the biological and cultural mechanisms that not only motivate moral behavior but also create the norms and standards by which the moral behavior of others is evaluated. Simply put, morality denotes the various solutions to problems of cooperation.[18] Behavior that solves a cooperative problem in a way that benefits both or all parties is generally judged as morally good, and uncooperative behavior as morally bad.

2.4 The Universal Scope of MAC Theory

Curry et al. distinguish seven types of cooperative problems and their seven cooperative solutions. The categories are not picked ad hoc; not only do they have evolutionary and game-theoretical backgrounds, but each of the moral domains has also been discussed individually in previous research with surveys and studies corroborating their meaningfulness.[19]

Curry et al. have proven the moral relevance of the seven categories of cooperative behavior and their distinctiveness from each other in four studies consisting of self-reports using a questionnaire (MAC-Q questionnaire)[20] with a contemporary sample of 1,392 UK working-age adults.[21] An analysis of 600 ethnographic accounts of 60 societies, on the other hand, revealed the cross-cultural nature of the categories.[22] This study comprised a content analysis of the ethnographic record from the digital version of the Human Relations Area Files (eHRAF) of 60 societies from six regions of the globe (Sub-Saharan Africa, Circum-Mediterranean, East Eurasia, Insular Pacific, North America, South America) using the holo-cultural method.[23] The results showed that cooperative behavior had a positive moral valence in 961 out of 962 observations (99.9%).[24]

A later study extended the analysis to a wider population of societies in the eHRAF corpus by using the Linguistic Inquiry and Word Count (LIWC) method.[25] A morality-as-cooperation dictionary (MAC-D) was created and used to machine-code ethnographic descriptions of morality in additional 196 societies (the whole eHRAF corpus) with results confirming the predictions of MAC theory.[26]

While MAC has a culturally universal scope, it does not expect moral values to appear in an identical form across cultures. Rather, their distribution is expected to “reflect the value of different types of co-operation under different social and ecological conditions.” The hope is that further studies and new data can help explain the causes behind the variation.[27]

2.5 Seven Cooperative Problems (Moral Domains) and Their Solutions

The seven moral domains argued by MAC theory have been introduced and discussed in several publications by Curry and his colleagues. The types of morality are the following: (1) family values, (2) group loyalty, (3) reciprocity, (4) heroism, (5) deference, (6) fairness, and (7) property rights. The terminology used for the categories has undergone small changes over the years, but their content has remained the same.[28]

There are seven types of solutions to cooperative problems that underlie the seven types of morality. The first type concerns the allocation of resources to genetic relatives and family. Biological adaptations to this effect include kin detection, incest aversion, and paternal investment among others, while cultural adaptations include, for example, inheritance rules. This type of cooperation explains why we care for our offspring, help our relatives, avoid incest, and negatively judge if someone leaves or betrays their family. The basic content can be expressed by the imperative “Love and care for your family.”

The second category concerns cooperation as coordination in groups to ensure mutual advantage. The biological adaptations are visible, for example, in herd behavior, collaborative hunting, and, importantly for humans, the theory of mind (ToM). Cultural adaptations include a host of cooperation-enhancing tools, such as clocks, calendars, maps, etc. The category relates to the formation of friendships and alliances and is amply visible in the tendency to favor ingroups over outgroups. Examples of vices in this category would be betrayal of the group, disloyalty, and, in the context of religion, apostasy, idolatry, and heresy.

The third type of cooperation centers on forms of reciprocal social exchange, such as returning favors, paying debts, keeping promises, etc. Biological adaptations in this class include cheater (free-riding) detection and forgiveness, while cultural adaptations include various “technologies of trust,” such as money, tickets, receipts, etc. As behavioral subcomponents to this strategy, Curry includes, for example, apology, gratitude, trust, guilt, and forgiveness, which means that free-riding, cheating, lying or hypocrisy, harshness, and unforgiveness count as vices.[29]

The last four cooperative types concern situations of conflict over resources, where the morally optimal solution is one that minimizes harm to both parties.

The fourth and fifth categories are hawkish displays of dominance and (5) doveish displays of deference, respectively. The strategies denote situations where participants choose to either display power or submission to solve a conflict without needing to fight over resources and causing or receiving harm. The strategies are well represented in animal life; everyone has most likely witnessed examples of this, for example, in meetings of domestic dogs, where the parties quickly adopt either a dominant or submissive role. The dominance category includes a range of indicators of heroic virtues, from dominance and authority to bravery, strength, resilience, and willingness to withstand suffering to a range of virtues associated with noblesse oblige (i.e., standing up for the weak, generosity toward the poor, and conspicuous altruism).[30] The doveish virtues include obedience and respect, and coincide, for example, with what David Hume identified as “monkish” ideals of celibacy, fasting, penance, mortification, self-denial, humility, silence, and solitude.[31] Biological adaptive traits for these include expressions and recognition of meaningful cues, such as facial expressions, size, and hormonal secretion. Cultural adaptations include a variety of hierarchical structures, honorific symbols and attire, sports, games, castes, etc. MAC theory predicts that both strategies form their own moral domains and both strategies are judged positively in situations of power imbalance.

The sixth moral domain concerns the fair division of resources in preventing or solving potential conflict situations. This can mean an equal share between contestants or a proportional share according to merit or a pre-agreed compromise. Fairness is associated with negotiation, compromise, and rules such as “I cut; you choose”; “meet in the middle”; “split the difference”; “take turns”; etc.

The last, seventh domain of conflict resolution is respect for prior possession and property rights. Developmentally, the idea of ownership appears in early childhood. And biologically, territoriality is well-attested in the animal world. Cultural adaptations include the many ways humans secure and inform about ownership and prevent theft. Negative manifestations include theft, vandalism, and not respecting another person’s personal space.

2.6 Moral Molecules

While MAC theory argues that the seven moral domains are functionally, evolutionarily, and psychologically distinct,[32] Curry et al. have recently widened the perspective toward a combinatorial system of “moral molecules.” The central claim is that the seven simple moral elements explain all varieties of morality by combining and forming complex solutions to complex problems. Two elements of family values and group loyalty can be combined to form a molecule of “fraternity” or “fictive kinship.” Combining family values and property rights, on the other hand, results in primogeniture and so on.[33] Eventually, the molecules can become larger and combine as many elements as needed with different ratios of importance, resulting in an infinite number of variations.[34] The net effect is the increased explanatory and predictive potential of MAC theory.[35]

3 The Source Material: The Sermon on the Mount (Matthew 5–7)

The Sermon on the Mount has both a particular social setting and universal appeal.[36] This mix has made the Sermon meaningful within Christianity and beyond it. Much of the biblical research history on the Sermon has sought to understand the text in its historical setting or to interpret it in light of later Christian theology – often confusing the two. Recent studies have reached beyond this to explain the universal behavioral and cognitive elements in the text. This chapter looks at the Gospel of Matthew and the Sermon on the Mount in their historical context and offers a brief introduction to scholarly discussion on the Sermon with the aim of setting the stage for the investigation of the text in terms of MAC theory.

The Gospel of Matthew is placed first in the canonical order, reflecting its status since the first centuries of the Christian church. The reference to the disciple Matthew as the author of the gospel is secondary.[37] The real author or authors remain unknown, as does the exact date of the compilation, which likely falls somewhere in the late first century.[38]

A distinguishing feature of the gospel is its embeddedness in Judaism: while the final outlook is one of universal mission (28:16–20), the author is “concerned throughout to anchor the incorporation of the Gentiles in Israel’s own Scriptures (e.g. 1:3–6; 4:15–16; 12:18–21).”[39] The audience keeps, for example, the Sabbath and Mosaic food regulations.[40] The gospel differs from the other canonical ones (especially the earlier Mark) by its well-organized and rich tradition of sayings attributed to Jesus. Matthew used the Gospel of Mark, the sayings source Q, traditions not known from elsewhere, the Jewish Scriptures, and his own creative redactional effort to compile a very successful volume.[41] Manuscript copies of Matthew from the first five centuries CE outnumber those of other gospels,[42] and the early church fathers quoted Matthew more frequently than other New Testament texts.[43]

The Sermon on the Mount is a long speech attributed to Jesus, comprising chapters 5–7 within the gospel. The Sermon has been considered a unit for special study at least since Augustine’s commentary De sermone domini in monte, which was written in the late fourth-century CE.[44] Augustine is also to be thanked for the nomenclature, which follows from the location of the speech in the narrative (Matt 5:1; 8:1).[45]

Hans Dieter Betz suggests that the author(s) of the Sermon “intended to formulate an epitome of the teachings of their revered teacher for the purpose of instructing those who had joined the Jesus movement, the ‘disciples.’”[46] The Sermon’s social location is dual in nature. On the one hand, it is tied to the social context of the Q movement, since the majority of the Sermon comes from the Q source.[47] The movement is generally thought to have been physically impoverished and struggling. On the other hand, the Matthean community is considered to have been more well-off and more likely in fear of social marginalization.[48]

Matthew’s rootedness in Judaism is visible in the Sermon’s references to Mosaic law. While the Gospel of Mark and Paul’s letters at times suggest laxity toward the Mosaic commandments (Mark 7; Gal 3), the Jesus of the Sermon famously insists that he did not “come to abolish the Law or the Prophets” and that “until heaven and earth pass away, not one letter, not one stroke of a letter, will pass from the law” (Matt 5:17–18). The audience is warned: “unless your righteousness exceeds that of the scribes and Pharisees, you will never enter the kingdom of heaven” (Matt 5:20). Particularly in the so-called antitheses (5:21–48), the Sermon tightens the standards concerning murder, adultery, and divorce: becoming angry at a brother or sister is equated with murder, looking at a woman lustfully is paralleled with adultery, and divorce is forbidden except for the reason of adultery (5:21–22, 27–28).[49] The antitheses finish with the command to love one’s enemies instead of loving one’s neighbor but hating one’s enemies (5:43–48).

Other notable characteristics that escalate moral standards include a strong emphasis on the right internal attitude and not acting morally just for outward appearance: “But when you fast, put oil on your head and wash your face, so that your fasting may be seen not by others but by your Father who is in secret” (Matt 6:17–18).[50] Willingness to suffer injustice and refrain from retaliating are demanded: “Do not resist an evildoer. But if anyone strikes you on the right cheek, turn the other also” (Matt 5:39).

Besides ethical commandments, the Sermon includes a variety of comforting statements about God’s care for the whole of creation – and especially the believers: “Look at the birds of the air: they neither sow nor reap nor gather into barns, and yet your heavenly Father feeds them. Are you not of more value than they?” (Matt 6:25). On other occasions, such as in the Beatitudes (or Macarisms) (5:1–12), the Sermon encourages a general attitude of trust and humility: “Blessed are the meek, for they will inherit the earth” (Matt 5:5) and “Ask, and it will be given to you; search, and you will find; knock, and the door will be opened for you” (Matt 7:7).

Finally, other famous passages in the Sermon include the Lord’s Prayer (6:9–13), the exhortations not to judge others (“Do not judge, so that you may not be judged,” in Matt 7:1), the Golden Rule (“In everything do to others as you would have them do to you, for this is the Law and the Prophets,” in Matt 7:12), and the parable of the wise and foolish builders (7:24–27).

The Sermon on the Mount has a rich history of interpretation, and it has been of monumental significance not only in the Christian tradition[51] but also in world literature.[52] Its influence goes beyond Judaism and Christianity,[53] extending to Islam[54] and religious–political figures, such as Mahatma Gandhi.[55] Critical voices include Friedrich Nietzsche.[56]

Perhaps the most pressing interpretive issue has been the purpose of the stringent ethics. Are the commandments meant to be obeyed in real life? Can they be followed literally, and if so, are they requirements for salvation?

Scholarship before the last decades of the 1900s tended to stereotypically take Judaism as legalistic and external, and sought to understand how the strictness of the Sermon should be viewed in light of allegedly legalistic Judaism. Protestant views reflect two directions. On the one hand, it was suggested that the commandments of the Sermon were impossible to follow, and they were therefore meant to act as a mirror for the readers to realize their own inadequacy and to turn to God’s grace in Christ.[57] The other tradition took the Sermon as relating not to behavior but to a general moral attitude and mentality of obedience.[58]

Hans Windisch’s important work from 1928 challenged interpretations that were built on the idea that the commandments in the Sermon on the Mount were impossible to obey fully. For him, Jesus’s commandments were meant to be followed and fulfilled; they represented terms of entry into the kingdom of God.[59] Agreeing with Windisch’s basic notion, Willi Marxsen famously went as far as to reject the compatibility of Christianity and Matthew’s Sermon.[60]

In the wake of E. P. Sanders’s (1977) influential reinterpretation of Judaism as a representative of “covenantal nomism,”[61] several scholars suggested that the Sermon is a variation of Jewish covenantal discourse related to the position of “staying in” God’s covenantal people, as opposed to “getting in” as an entry requirement.[62]

The history of interpretation and research on the Sermon has been very much theologically and intellectually oriented. Previous interpretations take the Sermon as part of some larger theological framework, assuming that the readers know it and have an interest in theologizing about the Sermon.[63] While this is a legitimate approach to the Sermon, which is, after all, a refined literary work, recent research has sought to complement this approach in various ways. A collection of essays edited by Rikard Roitto, Colleen Shantz, and Petri Luomanen (Social and Cognitive Perspectives on the Sermon on the Mount, 2021) applies various behavioral perspectives to the text with an interest in discovering how the Sermon can affect individuals intellectually and emotionally, even outside theological systems. Behavioral methods and theories such as cognitive science and social psychology can also help to reveal how the Sermon can influence both short-term decision-making and long-term character development.[64]

The essays include, for example, Elisa Uusimäki’s comparative discussion on the Beatitudes in both Matthew and the Dead Sea Scroll document 4Q525 which is informed by the social identity approach (SIA). Uusimäki argues that the Beatitudes function as tools of group identity formation and delineation by describing group prototypical behaviors and norms.[65]

Rikard Roitto’s article “Perception of Risk in the Sermon on the Mount” discusses the strict ethics of the Sermon from the perspective of perception of risk and emotions, building on the psychological reality that people underestimate the risks inherent in emotionally pleasant things and overestimate the riskiness of unpleasant or dreaded ones.[66] According to Roitto, the Sermon displays several tactics aimed at mitigating negative feelings associated with the risks of following stringent laws, such as avoiding depictions of the dangerous consequences of compliance (such as the eventual outcomes of submitting to persecution or giving away one’s possessions) but stressing the horrors that follow from non-compliance (5:29-30, 7:29), promising both extra- and intraworldly rewards (6:24-34; 7:7–11), and playing on the feeling of moral superiority (5:38–48).[67] The Sermon also depicts the willingness to engage in radical, risky ethics as bravery, which in turn figures as a prototypical ingroup characteristic. In discussing this, Roitto brings in elements that overlap with MAC theory. One of the management ways to tackle the fear of risky or dangerous behavior was to describe bravery as prototypical of the ingroup. This bravery, according to Roitto, is then contrasted to “ordinary ethics” – namely, worrying about one’s kin and material things – which according to Matthew is a characteristically gentile behavior (5:46–47; 6:31–32).[68] In MAC terms, we could suggest that in this instance, Matthew uses the moral domain of heroism to solidify morality in other domains positioning it over the domains of kinship and property rights.

Like the essay collection and some of the other works described above, the article at hand looks at the Sermon on the Mount from a perspective that is not theological and hermeneutical but explanatory and based on detecting cross-cultural patterns of human (moral) behavior. The workings of human cognition are strongly present in MAC theory, and the social identity approach (SIA) is closely related to MAC theory, as both share an interest in human group behavior and cooperation.

4 The Experimental Setting: Annotating the Sermon on the Mount in ATLAS.ti

In order to test the applicability of MAC theory to primary texts from the Christian cultural sphere, an annotation experiment was conducted using ATLAS.ti (version 24.2.1), a data analysis software designed for qualitative and mixed-methods research. ATLAS.ti provides a robust platform for organizing and coding qualitative data. Additionally, the software includes a range of built-in analytical tools, such as inter-coder agreement measures and code co-occurrence analysis, which can be applied at various stages of the research to facilitate both quantitative and qualitative evaluations.

The annotated Greek text consists of the Sermon on the Mount, from Matthew 5:1 to 7:29, sourced from the 28th edition of Nestle-Aland Novum Testamentum Graece (2012). The text was segmented into fixed units – such as sentences and clauses – to prevent discrepancies and overestimation of disagreement that could arise from varying segment selections by individual annotators.[69] After segmentation, the material comprised a total of 102 text units. The length of the text units varied considerably. On average, each unit contained 18.9 words, with word counts ranging from 5 to 62. The median length was 15 words, while the 25th percentile (Q1) was 11.25 words and the 75th percentile (Q3) was 24 words.

The coding system was developed together by the authors and built into the ATLAS.ti project. Contrary to common practice in qualitative research, the coding system was not constructed inductively from the data but was instead created deductively, based on the Morality-as-Cooperation theory. This reliance on pre-existing, well-defined categories adds external validity to the annotation process, as the codes were not formulated by the authors but derived from prior research. Being grounded in the Morality-as-Cooperation theory, the system comprises eight categories, seven of which correspond to the distinct moral domains defined by the theory. An additional “not applicable” category was included to capture text segments that contain moral statements but in the coders’ judgment do not align with any of the seven domains. This category serves two purposes: first, to minimize forced selections when coders could not confidently assign a domain; and second, to test the applicability of MAC theory to early Christian texts by identifying statements potentially outside its scope. The categorization into positive and negative moral statements used in testing MAC theory previously was dropped in order to focus on recognizing the proposed moral domains in the text. For the purposes of this study, that categorization would have added an unnecessary extra layer of complexity, the relevance of which would have been marginal considering the research questions.

Five annotators participated in the coding process: three from the University of Helsinki and two from the University of West Bohemia. All five specialize in early Christian studies or biblical studies more broadly, and include two doctorate holders, one doctoral researcher, and two master’s students, four of whom also constitute the authors of this article. Using the authors as annotators was justified by their competence in early Christian sources, an expertise considered essential for accurately interpreting the complicated text in the original language. Furthermore, because the coding system was derived deductively, the authors’ role as annotators did not compromise the objectivity of the process. All annotators were required to read at least Curry’s foundational article “Morality-as-Cooperation: A Problem-Centred Approach” (2016) before annotation, in order to become familiar with MAC theory, ensuring a common theoretical foundation for the coding process.

Detailed instructions were written to guide the annotation process, based on testing the software and discussing MAC theory and the goals of the study. These instructions included a technical guide to using ATLAS.ti and a table outlining each of the seven MAC moral domains. The annotators were instructed as follows: “Select a code that corresponds to the relevant Moral domain. Use two domains if necessary, but no more than that. If the passage contains a statement concerning morality but in your view it does not fit any of the seven Moral domains, add the code ‘not applicable.’ If the passage does not contain moral statements, leave it without code altogether.”[70]

Annotators were asked to choose one or two categories due to the complex and often multifaceted nature of the moral teachings in the Sermon on the Mount. Allowing only one category could have oversimplified the moral content of the text, while allowing more than two categories would have unnecessarily complicated both the annotation and the analysis. Moreover, MAC theory does not require moral domains to be mutually exclusive, and many expressions of morality can reflect combinations of multiple domains.[71]

Each annotator worked independently with a clean copy of the main project, without knowledge of others’ coding decisions. To avoid influencing individual judgments, discussions about the coding process were explicitly discouraged. This ensured that any inter-coder agreements – and, more importantly, natural disagreements – emerged from genuine individual judgment rather than a collaboratively reached interpretation, which was one of the study’s key interests. After the annotation process was completed, the annotated documents were collected and merged into one project file.

5 Analysis

The purpose of this experiment was to explore a new area of research and establish a foundation for more extensive studies in the future. We investigated whether MAC theory provides new insights into the discourse surrounding the Sermon on the Mount. Simultaneously, the Sermon served as a test case for evaluating whether the moral domains proposed by MAC theory are present and identifiable in early Christian sources and whether these sources contain moral elements that extend beyond these domains.

In analyzing the annotation data, we applied a mixed-methods approach to address two primary aims (1) to characterize the moral content of the Sermon and assess its alignment with MAC’s moral domains, and (2) to examine the degree of consensus among the annotators’ interpretations.

The results were first exported from ATLAS.ti into Microsoft Excel and subsequently transferred to a Python environment for further analysis.[72] For data manipulation and statistical computations, we relied primarily on Pandas, NumPy, and Scikit-learn, while Matplotlib and Seaborn were employed to generate visualizations.

From the raw data, we calculated the total occurrences of each code category across all text units and for each annotator. To provide a broader overview of the results, these absolute frequencies were converted into proportions. Additionally, descriptive statistics were computed to further clarify the overall structure of the results.

The exported raw data also included code co-occurrence results. We analyzed these results to explore the moral complexity of the Sermon and the presence of so-called “moral molecules.” ATLAS.ti calculates co-occurrence metrics at the level of text units. The calculations are based on the merged dataset, in which all the annotators’ coding decisions are combined. A co-occurrence is recorded only when the same annotator assigns both codes to the same text unit. Instances where different annotators independently assign different codes to the same unit are not counted as co-occurrences.

The software records code co-occurrences as absolute counts. However, raw frequencies alone do not indicate the significance of these associations, as it remains unclear whether the two codes co-occur due to a meaningful connection or simply because they are both common. To address this, we measured the strength of these associations using ATLAS.ti’s built-in C-coefficient alongside Pointwise Mutual Information (PMI), which was calculated separately.

The C-coefficient used in ATLAS.ti is mathematically equivalent to the similarity metric known as the Jaccard Coefficient, which quantifies how much two sets overlap relative to their total combined size. ATLAS.ti’s formula for the C-coefficient is

where n 12 is the number of text units where both codes co-occur at least once, n 1 is the total number of text units where the first code appears at least once, and n2 is the total number of text units where the second code appears at least once. The C-coefficient ranges from 0 to 1, where 0 indicates that the two codes never co-occur, while 1 signifies that the two codes always co-occur whenever either one is present.

Pointwise Mutual Information quantifies the association between two items by comparing the probability of their co-occurrence to the probabilities of their individual occurrences, assuming statistical independence. PMI was computed using the standard formula

where

PMI complements the C-coefficient by assessing both the strength and direction of the association. In principle, PMI has no upper or lower limit and can therefore take any real value. A positive PMI value indicates that the codes co-occur more frequently than expected by chance, suggesting a positive association. Conversely, a negative PMI suggests that the codes co-occur less frequently than expected, indicating a negative association.

Both measurements have inherent limitations that should be considered when interpreting the results. Specifically, the C-coefficient is sensitive to disparities in code frequencies: when one code is applied significantly more often than another, the C-coefficient may underestimate their co-occurrence, potentially overlooking meaningful associations. Similarly, PMI is influenced by item frequency, with low-frequency items often yielding high PMI scores, which may overstate the strength of associations.

Examining the degree of consensus among the annotators was crucial for several reasons. First, analyzing the similarities and differences in their coding decisions clarifies the extent to which the overall results reflect a shared understanding. Additionally, it can help identify potential ambiguities in the Sermon’s moral teachings. Furthermore, measuring consensus provides critical methodological insights for future studies, in which we plan to apply a similar approach to text corpora comprising millions of words, using machine-learning techniques. Since machine-learning models depend on human annotations for training, ensuring sufficient consistency in these annotations is a necessary step toward achieving robust analytical outcomes.

To assess the degree of consensus among annotators and to quantify the similarities and differences in their interpretations, we calculated multiple metrics.

First, we applied Krippendorff’s Alpha to assess agreement at the level of individual text units – specifically, how often annotators assigned the same codes to the same units. Krippendorff’s Alpha is a statistical measure of inter-coder agreement that assesses the degree of agreement among annotators, considering the possibility of agreement occurring by chance. It is widely used in annotation studies and, among the measures we applied, it is the most directly relevant for evaluating annotation data quality in the context of training machine-learning models.

The general formula for Krippendorff’s Alpha is

where

To determine observed disagreement, comparisons are made between every pair of annotators across all text units. Whenever two annotators assign the same code to a text unit, the disagreement for that unit is zero; if their codes differ, the disagreement is one. These unit-level disagreements are aggregated into a single

Calculating Krippendorff’s Alpha for an annotated document of 102 text units coded by five annotators (ten annotator pairs) across eight different codes, with multiple codes allowed per unit, is a complex undertaking. ATLAS.ti computes Alpha values automatically based on the annotation data. The software does not display the intermediate steps of the calculation, only the final results. The fundamental logic can still be illustrated with a highly simplified example:

Two annotators (A1 and A2) code a short document consisting of five text units, using only the labels “reciprocity” and “fairness.” Suppose the following pattern emerges:

Unit 1: both annotators code “reciprocity” (disagreement = 0). Unit 2: both annotators code “fairness” (disagreement = 0). Unit 3: A1 codes “reciprocity,” A2 codes “fairness” (disagreement = 1). Unit 4: A1 codes “fairness,” A2 codes “reciprocity” (disagreement = 1). Unit 5: both annotators code “reciprocity” (disagreement = 0).

The observed disagreement for this annotator pair is

A Krippendorff’s Alpha value of 1 indicates perfect agreement, while a value of 0 suggests no agreement beyond what would be expected by chance. In general, an Alpha value of 0.8 or higher indicates acceptable reliability; values between 0.667 and 0.8 suggest moderate agreement, and values below 0.667 reflect low agreement.[73] The simplified example demonstrates that Krippendorff’s Alpha can remain very low even when annotators appear to agree more often than they disagree, if their overall level of agreement is close to what could be achieved by chance alone.

Next, we applied several computational methods to examine individual differences and trends among the annotators. We quantified the overall coherence of the annotators as a group, compared individual annotators to each other, and assessed their coding patterns against a null model of random coding.

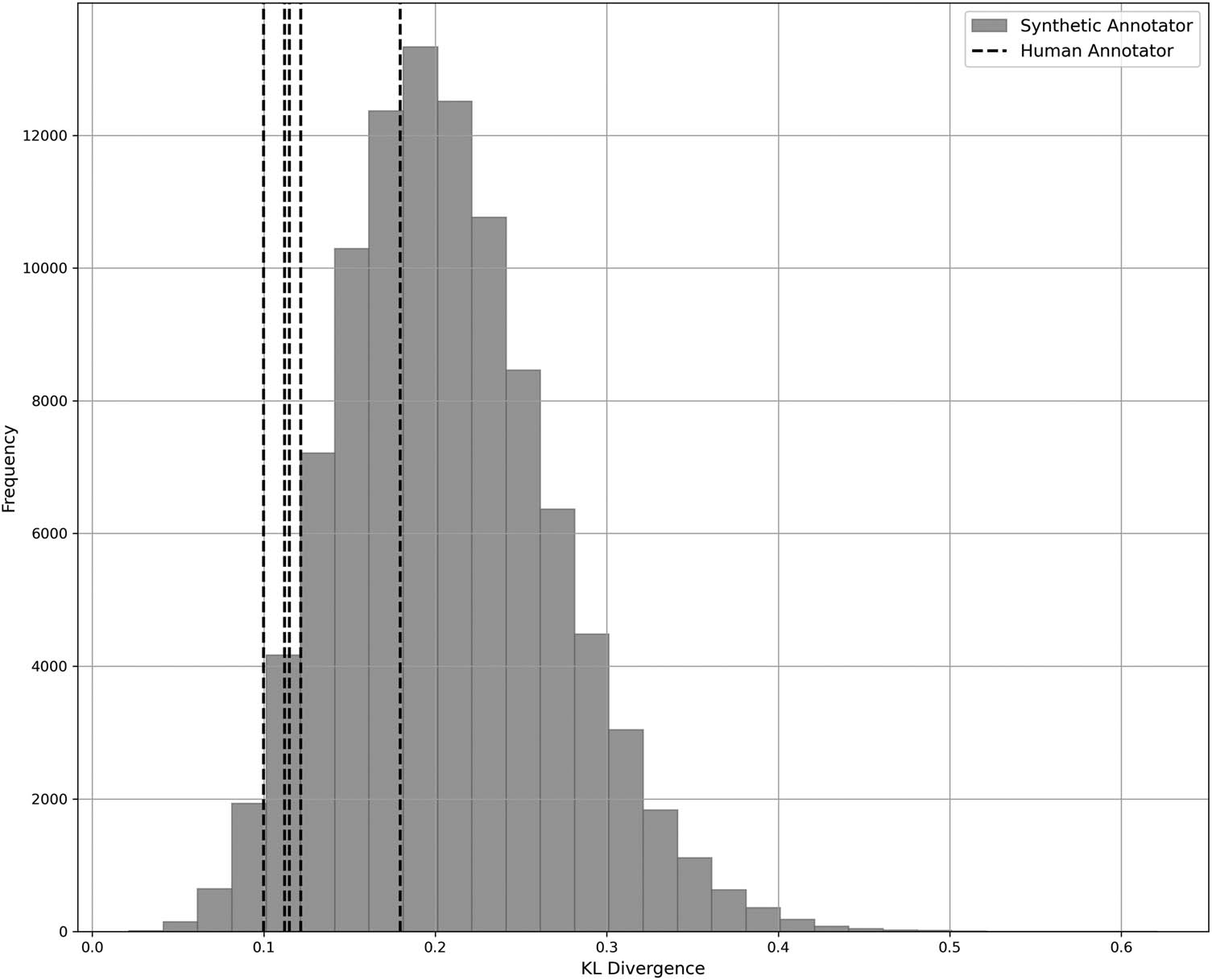

To provide a broader perspective, we first measured each annotator’s coding distinctiveness by computing the Kullback–Leibler (KL) divergence between their individual code proportions and the group average.

Kullback–Leibler (KL) divergence is a statistical measure that quantifies the difference between two probability distributions by estimating the additional information required when one distribution is used to approximate another. In this study, it was computed using the formula

where

KL divergence values are always non-negative and, in principle, can range from zero to infinity. In this study, a value of 0 indicates that the annotator’s code distribution is identical to the group distribution, while higher values suggest greater divergence. KL divergence thus provides a numerical overview of how closely each annotator’s coding behavior aligns with the group norm, identifying the annotators whose coding patterns deviate most significantly.

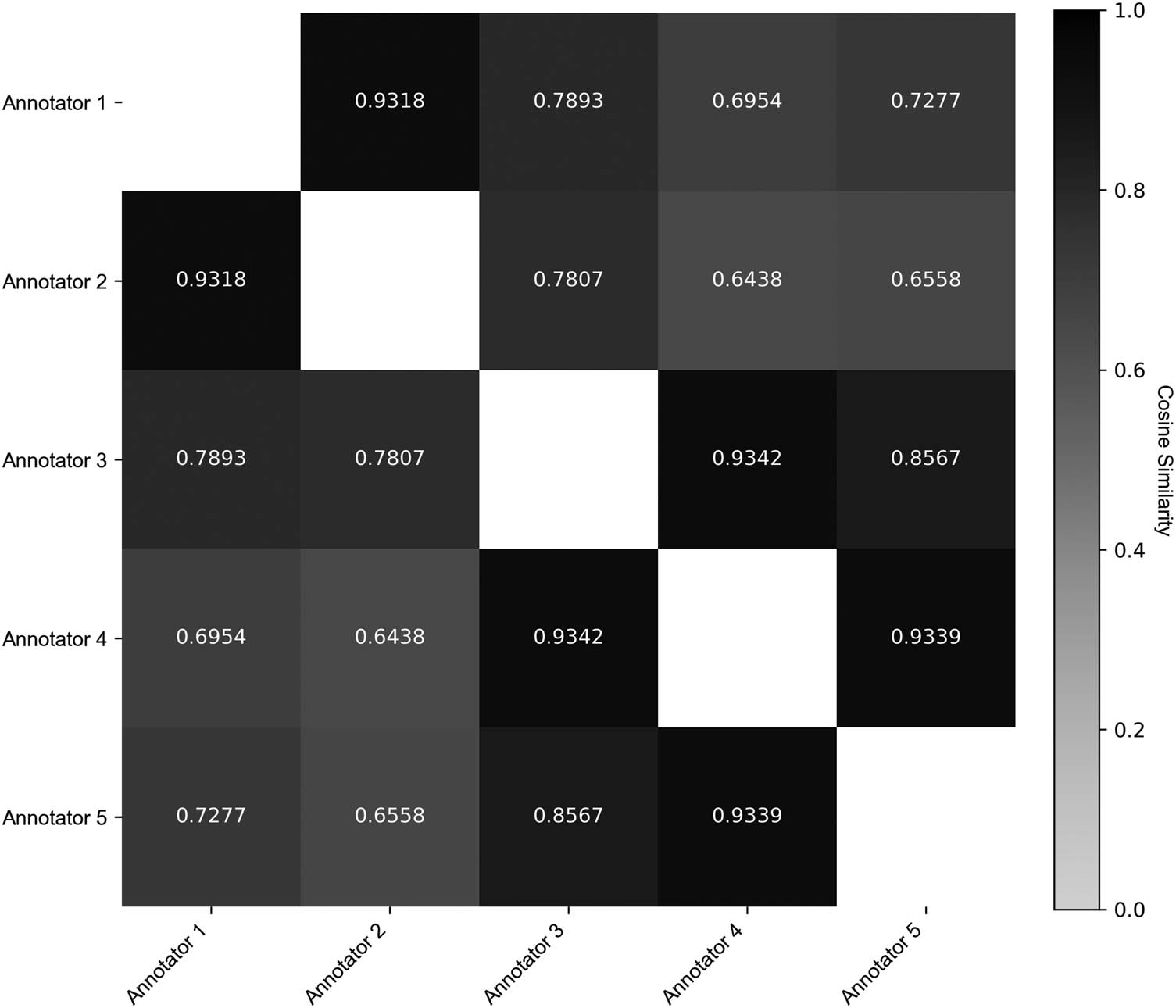

Next, we applied Cosine Similarity to compare the annotators’ overall coding profiles. Cosine Similarity is a geometric measure that quantifies the directional similarity between two vectors by computing the cosine of the angle between them. Cosine Similarity is computed as the dot product of two vectors divided by the product of their magnitudes, which normalizes the similarity measure to a range between 0 and 1 for non-negative vectors. A value of 1 indicates that the vectors point in exactly the same direction, while 0 indicates complete orthogonality. Because Cosine Similarity captures only directional similarity, differences in the annotators’ absolute code frequencies do not affect the measure.

We did pairwise calculations for all annotators. For instance, to calculate Cosine Similarity between Annotators 1 and 2, their total counts in the eight code categories were interpreted as two 8-dimensional vectors:

Then, the dot product of these vectors was calculated as

The magnitudes were calculated as

Finally, substituting these values into the Cosine Similarity formula yields

To contextualize the results and compare human-made annotations with rule-based random annotation, we implemented a synthetic annotation model as a baseline. The synthetic annotation data were generated using 100,000 simulated “annotators,” each of whom randomly assigned zero, one, or two of the eight possible codes to the 102 text units, following the same constraints as the real annotators. This null model represented a scenario in which there was no meaningful connection between the Sermon and the interpretations made by the annotators.

We computed the KL divergence for each synthetic annotator’s code distribution relative to the overall group distribution, creating a baseline distribution of KL values. We then compared the real annotators’ KL scores to this baseline by calculating the fraction of simulated annotators who had an equal or smaller divergence, indicating how frequently equally close distributions would occur under entirely random assignment.

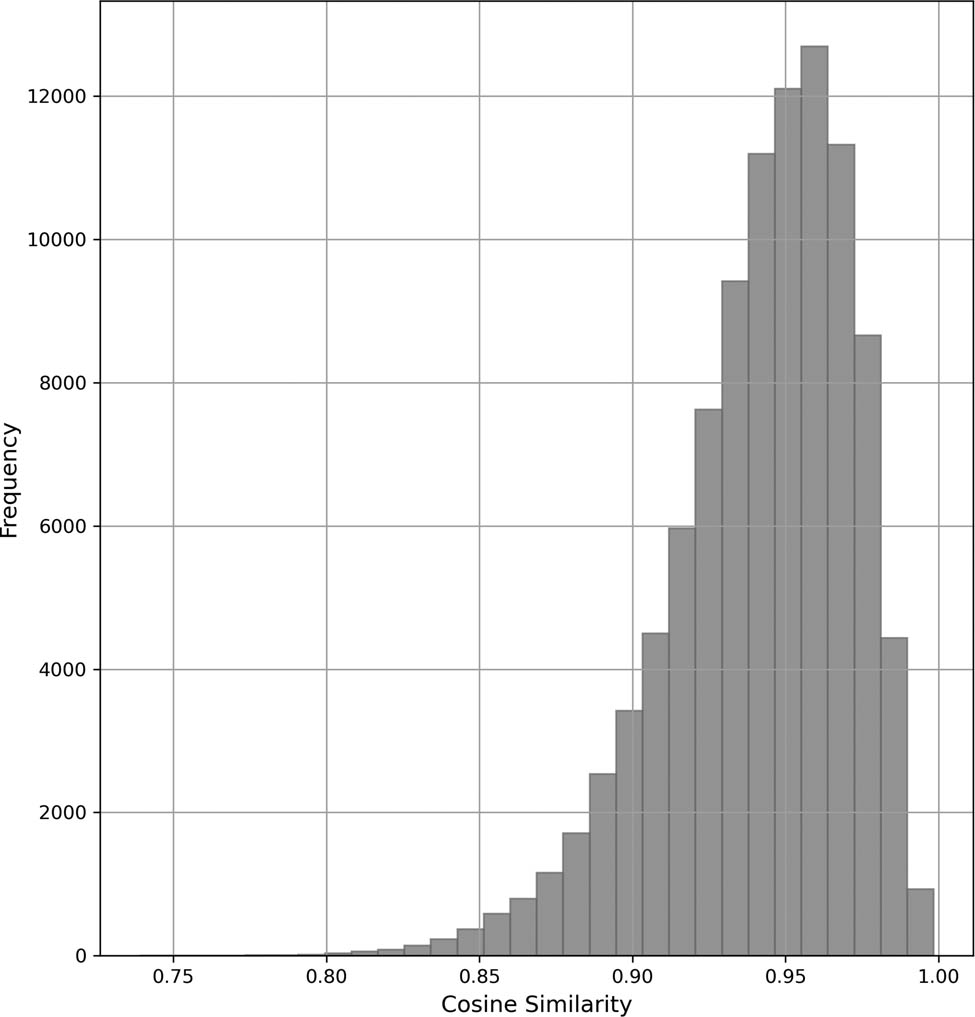

To contextualize our Cosine Similarity results, we computed the same metric for 100,000 randomly selected pairs of synthetic annotators. These random-pair values were compared with the real annotator pairs’ scores. This allowed us to determine whether the alignments observed among the real annotators were notably stronger or weaker than one would expect from random coding alone.

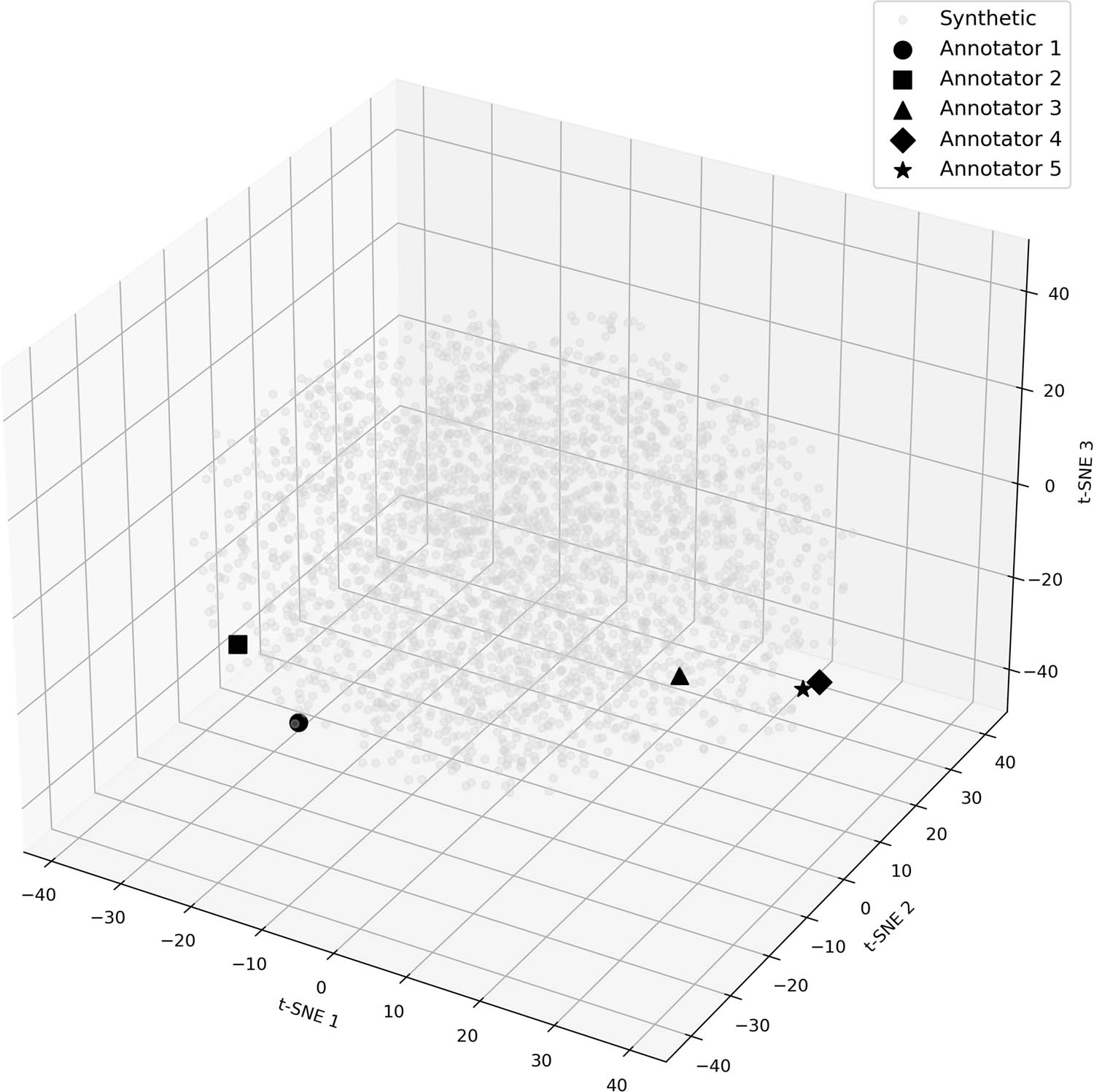

To complement our numerical findings with a more intuitive visual overview, we used t-distributed Stochastic Neighbor Embedding (t-SNE) to project both the real and synthetic annotators’ eight-dimensional code counts into three dimensions. T-SNE is a dimensionality reduction algorithm designed to approximate a low-dimensional layout that preserves local distances and similarities. While inherently heuristic, t-SNE can highlight local structures in high-dimensional data, enabling a quick comparison of how real annotators might situate themselves relative to synthetic ones.[74]

Finally, we complemented our global measures with two category-level metrics that elucidate the annotators’ individual coding tendencies. As an extension of the previously calculated KL divergences, we leveraged pointwise contributions to show which specific codes most strongly distinguished an annotator from the group norm. Additionally, we used modified Z-scores to highlight deviations in code usage relative to the group median, thus controlling for differences in overall coding activity.

Pointwise contributions are the individual terms in the summation that define the Kullback–Leibler divergence. For each code category

where

The modified Z-score is a standardized measure of how much an individual data point deviates from the group median, scaled by the overall variability.[75] In this study, modified z scores were calculated for each coding category by using the formula:

where

In closing, we emphasize that this experiment occupies a middle ground between qualitative and quantitative approaches, relying on five annotators. Five is an ample number for a qualitative coding project. However, it remains too small for robust statistical inferences when comparing annotators, since each code category ultimately reflects only five data points. Consequently, the group-level references used in KL divergence (

6 Results

A significant portion of the text was perceived as conveying moral teaching. On average, each annotator identified 76 out of 102 text units as containing moral statements, representing 74.5% of the text (Table 1).

Annotator’s coding decisions

| Annotator 1 | Annotator 2 | Annotator 3 | Annotator 4 | Annotator 5 | Total | Mean | Median | SD | MAD | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Codes applied | 116 | 138 | 36 | 141 | 102 | 533 | 106.6 | 116 | 42.6 | 22 |

| Units coded | 78 | 86 | 32 | 100 | 83 | 379 | 75.8 | 83 | 25.8 | 5 |

| Family values | 12 | 8 | 3 | 10 | 8 | 41 | 8.2 | 8 | 3.3 | 2 |

| Group loyalty | 29 | 22 | 2 | 8 | 13 | 74 | 14.8 | 13 | 10.8 | 9 |

| Reciprocity | 15 | 17 | 8 | 44 | 42 | 126 | 25.2 | 17 | 16.6 | 9 |

| Heroism | 16 | 21 | 5 | 27 | 11 | 80 | 16.0 | 16 | 8.5 | 5 |

| Deference | 19 | 17 | 10 | 38 | 20 | 104 | 20.8 | 19 | 10.4 | 2 |

| Fairness | 2 | 8 | 4 | 8 | 1 | 23 | 4.6 | 4 | 3.3 | 3 |

| Property rights | 2 | 9 | 0 | 6 | 3 | 20 | 4.0 | 3 | 3.5 | 3 |

| Not applicable | 21 | 36 | 4 | 0 | 4 | 65 | 13.0 | 4 | 15.2 | 4 |

The annotators applied a total of 533 codes across the text units, of which 468 (87.8%) corresponded to MAC domains. This indicates that the moral domains proposed by the theory are present and identifiable in the Sermon.

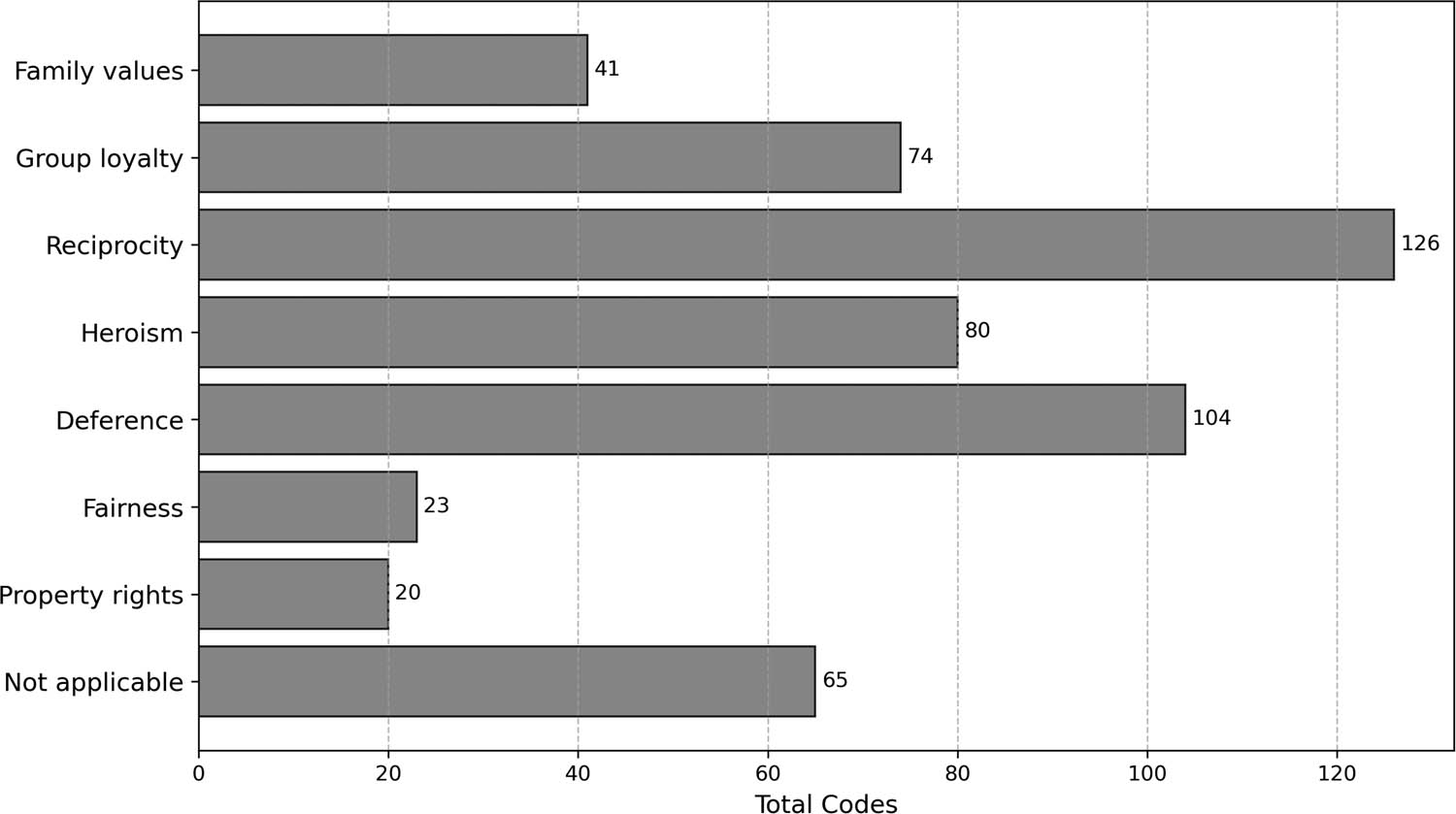

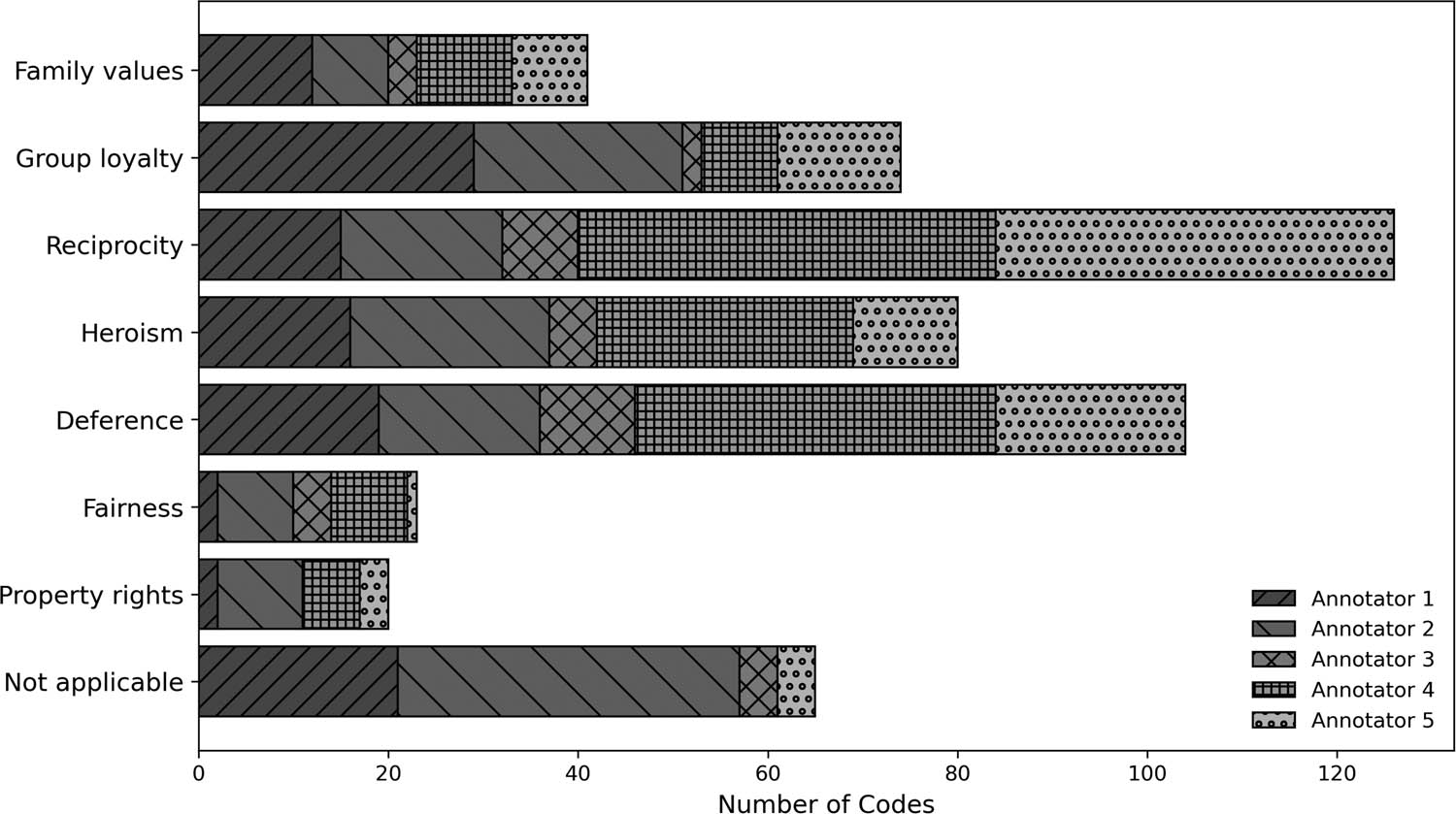

The representation of moral domains varied across the text. Reciprocity was the most frequently identified domain, with 126 codes applied, accounting for 23.6% of all codes. It was followed by Deference with 104 codes (19.5%), Heroism with 80 codes (15.0%), and Group Loyalty with 74 codes (13.9%). Less frequently coded domains included Family Values with 41 codes (7.7%), Fairness with 23 codes (4.3%), and Property Rights with 20 codes (3.8%) (Figure 1).

Total codes by moral domains.

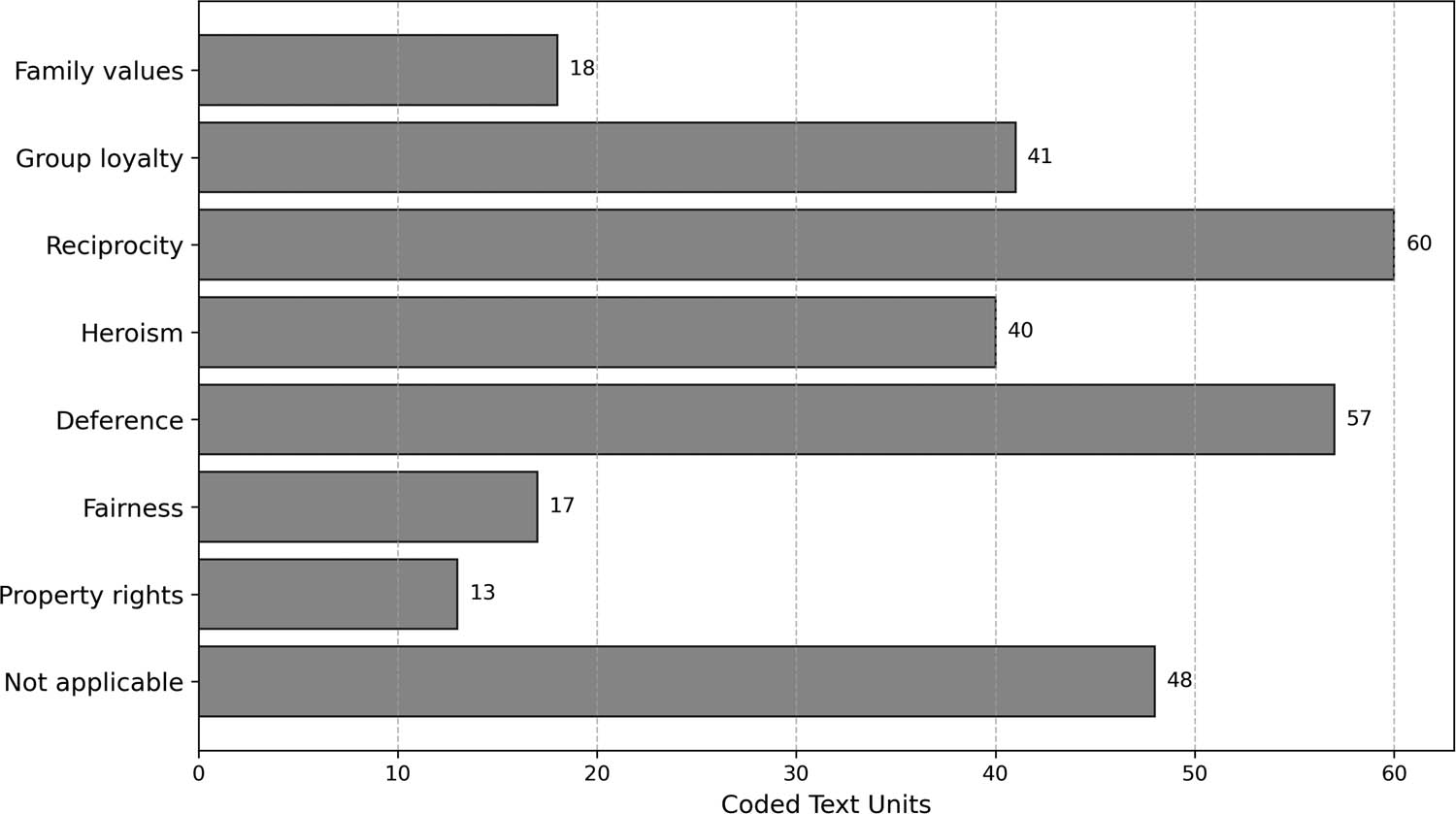

Regarding the number of text units coded with each domain at least once, Reciprocity and Deference were again the most prominent. Reciprocity was coded in 60 out of 102 units (58.8%), and Deference in 57 units (55.9%). Group Loyalty was identified in 41 units (40.2%), and Heroism in 40 units (39.2%). The domains of Family Values, Fairness, and Property Rights were less represented, appearing in 18 units (17.6%), 17 units (16.7%), and 13 units (12.7%), respectively (Figure 2).

Coded text units by moral domains.

On average, annotators assigned 1.4 codes per coded unit, suggesting that individual text units often encompass multiple moral themes. This indicates that the Sermon’s moral teachings are complex and multidimensional, frequently involving overlapping moral domains.

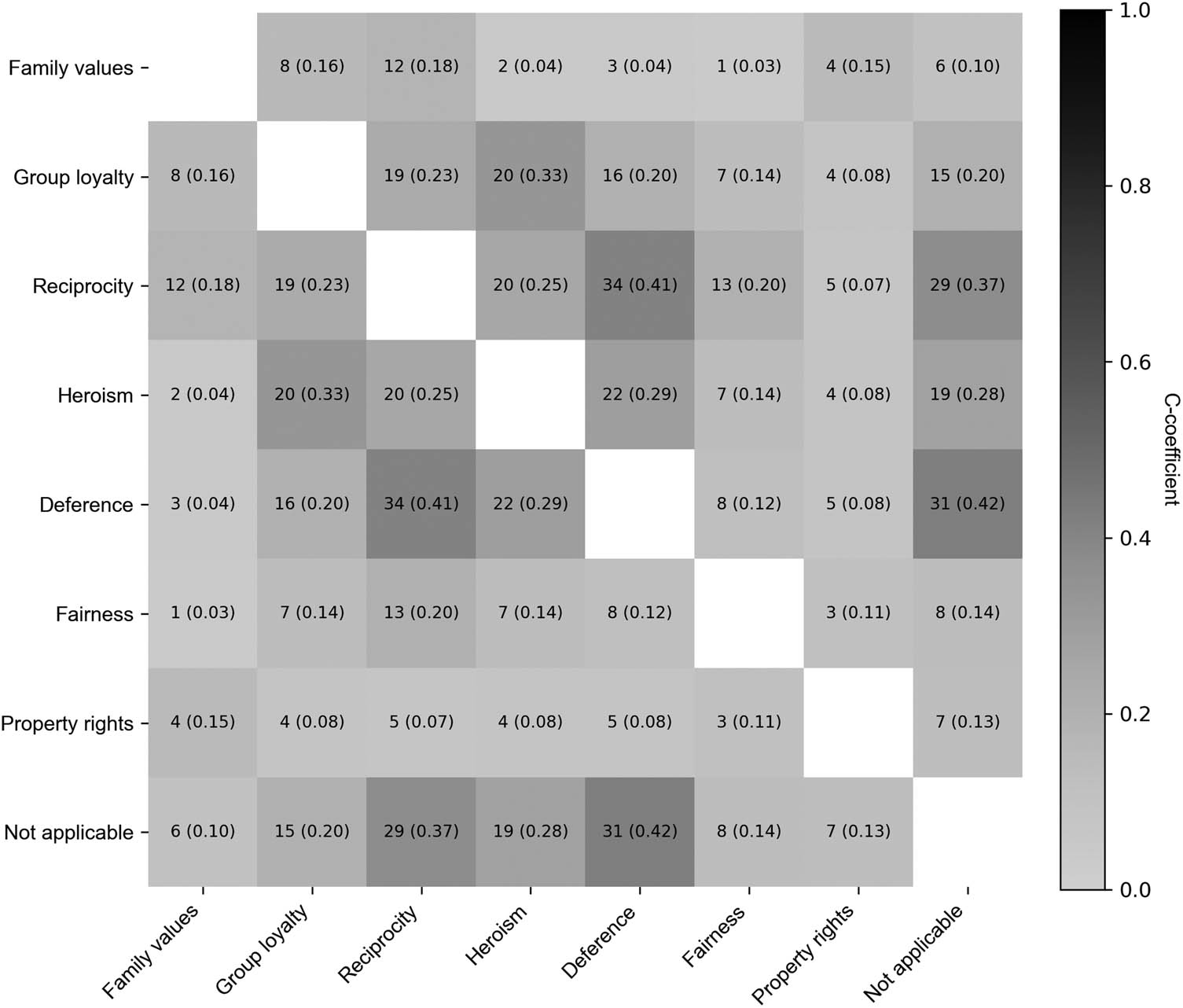

Each coding category co-occurred with every other category at least once, resulting in a total of 28 unique code pairs. Certain pairs frequently appeared together within the same text units, indicating recurring associations among specific moral domains.

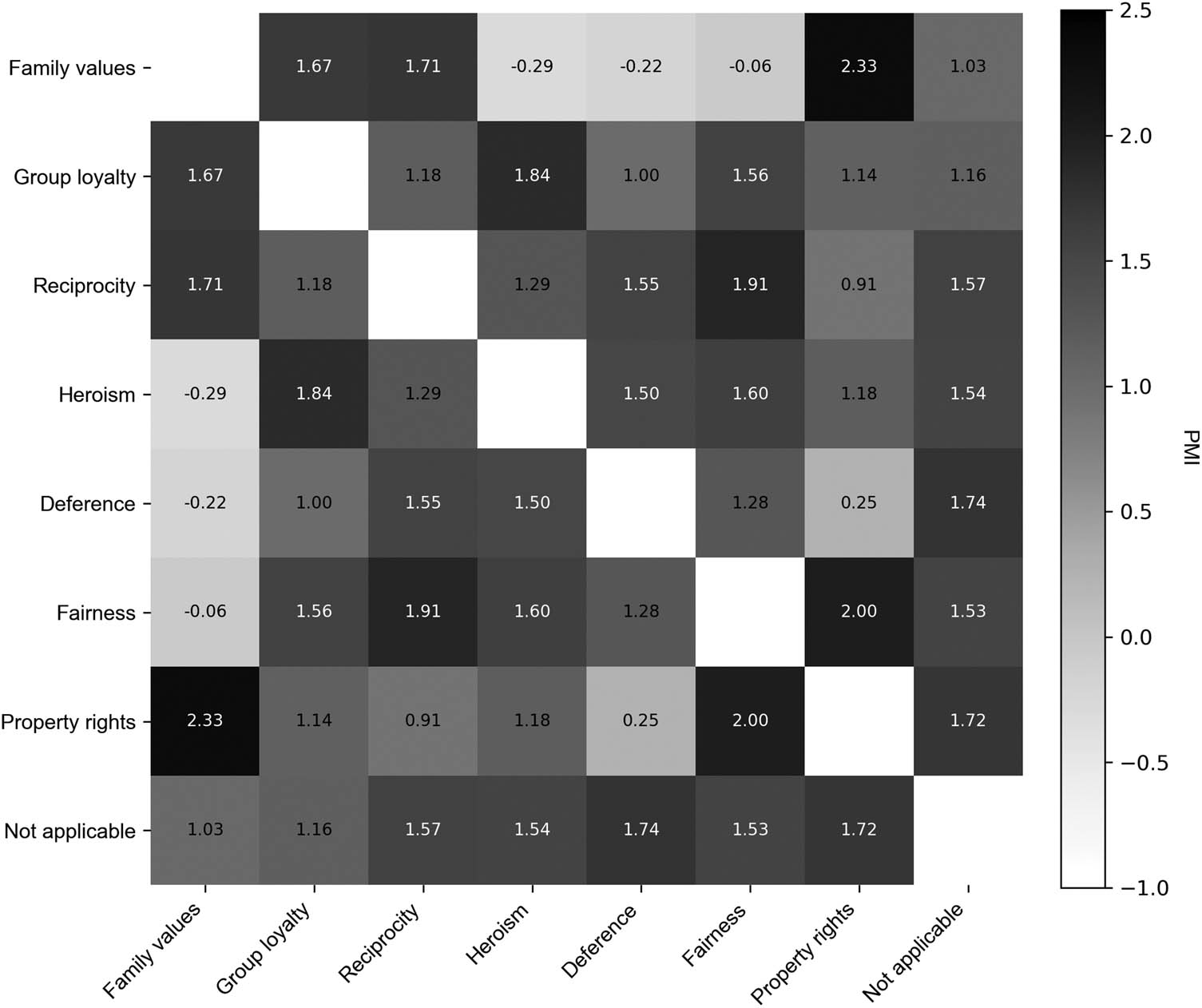

Out of the 28 code pairs, four displayed a C-coefficient higher than 0.3, while 25 pairs showed positive PMI values, indicating a higher-than-chance likelihood of co-occurrence. Notably, Family Values were the only domain associated with negative PMI values. The strongest co-occurrence was between Reciprocity and Deference, which appeared together 34 times with a C-coefficient of 0.41 and a PMI of 1.55, suggesting a meaningful overlap in these domains. Heroism and Group Loyalty also demonstrated a relatively strong association, co-occurring 20 times (C-coefficient, 0.33; PMI, 1.82). A notable co-occurrence was between Heroism and Deference, which co-occurred 22 times (C-coefficient, 0.29; PMI, 1.50). This pairing appears contradictory, as these two domains represent opposing strategies in the hawk-dove game. These findings support the view that the Sermon’s moral teachings are often complex, with certain moral domains frequently co-occurring, possibly forming what could be described as “moral molecules.” (Figures 3 and 4).

Co-occurrence counts and C-coefficients.

PMI values of co-occurrences.

The “Not Applicable” code was assigned 65 times across the text units, and 48 out of 102 units (47.1%) were coded as Not Applicable by at least one annotator. This indicates that a substantial portion of the Sermon’s moral content was perceived as not fitting neatly within the existing MAC domains. Furthermore, the “Not Applicable” code frequently co-occurred with other moral domains. Notably, it co-occurred with Deference 31 times (C-coefficient, 0.42; PMI, 1.74) and with Reciprocity 29 times (C-coefficient, 0.37; PMI, 1.57). The high co-occurrence rates indicate that certain moral statements encompass aspects both within and beyond the MAC framework, implying that the theory may not fully capture the complexity of the moral teachings in the Sermon.

The global Krippendorff’s Alpha was 0.124 – slightly higher than chance but still indicating poor general agreement. Notably, this low Alpha value cannot be attributed solely to the number of annotators or to a single outlier. Even when any two annotators were excluded from the calculation, the highest Alpha observed was only 0.308. At the level of individual moral domains, Krippendorff’s Alpha values also remained low, ranging from –0.001 for Not Applicable to 0.369 for Family Values. Overall, these findings suggest that the annotators had considerable difficulty in consistently applying the same codes to the same text units (Table 2).[76]

Krippendorff’s alphas

| Code category | Alpha |

|---|---|

| Family values | 0.369 |

| Group loyalty | 0.204 |

| Reciprocity | 0.224 |

| Heroism | 0.262 |

| Deference | 0.146 |

| Fairness | 0.112 |

| Property rights | 0.206 |

| Not applicable | −0.001 |

Kullback–Leibler divergences were relatively low overall, with four values clustering between 0.0999 and 0.1216. Annotator 1 showed the lowest divergence (0.0999) from the group norm, followed closely by Annotator 3 (0.1122), Annotator 5 (0.1150), and Annotator 2 (0.1216). This tight range suggests that large-scale coding distributions did not differ substantially among those four. By contrast, Annotator 4 exhibited a noticeably higher divergence (0.1795), indicating a more distinct coding pattern.

Comparisons with a baseline of synthetic annotators further underscore these observations. The mean KL divergence for the simulated group was 0.2064, meaning all five real annotators remained below the typical random level. Only 2.4% of the synthetic annotators produced an equally low or lower divergence than Annotator 1, and similarly, small proportions matched Annotator 3 (4.6%), Annotator 5 (5.2%), and Annotator 2 (6.9%). In contrast, 35.5% of the synthetic annotators achieved an equal or lower KL divergence than Annotator 4. Overall, these comparisons suggest that four annotators are relatively close to the group norm and substantially distinct from random assignment, while Annotator 4, though still falling below the synthetic mean, stands out as having a more individual coding profile (Figure 5).

Kullback–Leibler divergence distribution.

The Cosine Similarity between the five annotators ranged from 0.6438 to 0.9342. Annotator 3 and Annotator 4 exhibited the highest similarity (0.9342), followed closely by Annotator 4 and Annotator 5 (0.9339) and Annotator 1 and Annotator 2 (0.9318). In contrast, Annotator 2 showed relatively low similarity with Annotator 4 (0.6438) and Annotator 5 (0.6558), as did Annotator 1 with these same annotators (0.6954 and 0.7277). This distribution suggests two broad groupings: one comprising Annotator 1 and Annotator 2, and the other consisting of Annotator 3, Annotator 4, and Annotator 5. Despite deviating most from the overall group norm, Annotator 4 exhibited the highest Cosine Similarity within the second subgroup, suggesting that Annotator 4 is the most distinct member of that subgroup (Figure 6).

Cosine similarity among annotators.

The null model contextualizes these values. The synthetic annotator pairs had a mean similarity of 0.9417, which exceeds the highest similarity observed among any two real annotators. Notably, 65.4% of the synthetic pairs surpassed the maximum Cosine Similarity found among the real pairs (0.9342). Moreover, the random distribution ranged from 0.7391 to 0.9984, meaning that none of the 100,000 synthetic pairs exhibited similarity as low as that observed between Annotator 1 or 2 and Annotator 4 or 5. These results suggest that real interpretive patterns introduce variability that a purely stochastic process cannot replicate (Figure 7).

Cosine similarity distribution for synthetic pairs.

A t-distributed Stochastic Neighbor Embedding (t-SNE) visualization provided a low-dimensional view consistent with these findings. When projected into three dimensions, the five real annotators positioned themselves along the outer edge of a dense cluster of synthetic annotators. This pattern further highlights that human coding distributions diverge from the randomness seen in the null model (Figure 8).

A t-distributed stochastic neighbor embedding.

Taken together, the results suggest that the five annotators exhibited broadly similar overall interpretations of the Sermon when contrasted with random annotation. However, there was a notable interpretive divide within the group.

Pointwise contributions and modified Z-scores indicate that each annotator exhibits at least one notable departure in coding behavior. Moreover, these metrics imply that the primary interpretive distinction between the subgroups is the differential emphasis on Not Applicable versus Reciprocity (Tables 3 and 4).

Pointwise contributions for each annotator

| Code category | Annotator 1 | Annotator 2 | Annotator 3 | Annotator 4 | Annotator 5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Family values | 0.0307 | −0.0162 | 0.0076 | −0.0055 | 0.0018 |

| Group loyalty | 0.1457 | 0.0218 | −0.0507 | −0.0507 | −0.0109 |

| Reciprocity | −0.0779 | −0.0802 | −0.0156 | 0.0855 | 0.2253 |

| Heroism | −0.0117 | 0.002 | −0.011 | 0.0462 | −0.0355 |

| Deference | −0.0288 | −0.0566 | 0.0938 | 0.0861 | 0.0005 |

| Fairness | −0.0158 | 0.0174 | 0.1054 | 0.0159 | −0.015 |

| Property rights | −0.0133 | 0.0364 | −0.0071 | 0.0057 | −0.0067 |

| Not applicable | 0.071 | 0.197 | −0.0101 | −0.0036 | −0.0446 |

Modified Z-scores for each annotator

| Code category | Annotator 1 | Annotator 2 | Annotator 3 | Annotator 4 | Annotator 5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Codes applied | 0.0 | 0.6745 | −2.45 | 0.77 | −0.43 |

| Units coded | −0.6745 | 0.4 | −6.88 | 2.29 | 0.0 |

| Family values | 1.35 | 0.0 | −1.69 | 0.67 | 0.0 |

| Group loyalty | 1.2 | 0.67 | −0.82 | −0.37 | 0.0 |

| Reciprocity | −0.15 | 0.0 | −0.67 | 2.02 | 1.87 |

| Heroism | 0.0 | 0.67 | −1.48 | 1.48 | −0.67 |

| Deference | 0.0 | −0.67 | −3.04 | 6.41 | 0.34 |

| Fairness | −0.45 | 0.9 | 0.0 | 0.9 | −0.67 |

| Property rights | −0.22 | 1.35 | −0.67 | 0.67 | 0.0 |

| Not applicable | 2.87 | 5.4 | 0.0 | −0.67 | 0.0 |

Annotator 1 showed a notable preference for Group Loyalty, assigning 25% of all codes to that category. This is reflected in a pointwise contribution of 0.1457 and a modified Z-score of 1.20. Additionally, 18.1% of Annotator 1’s codes fall under Not Applicable. The modified Z-score of 2.87 and the pointwise contribution of 0.0710 for that category indicate overuse.

Annotator 2 displays a strong preference for Not Applicable, using it for 26.1% of the total codes. Both a pointwise contribution of 0.1970 and a modified Z-score of 5.40 identify this pattern as a clear outlier. Additionally, a notable preference for Property Rights stands out (6.5%), with a pointwise contribution of 0.0364 and a modified Z-score of 1.35.

Annotator 3 stands apart primarily in terms of their low overall coding activity. The “Units coded” measure has a modified Z-score of −6.88, and the “Codes applied” stand at −2.45, indicating a significantly lower tendency to identify moral statements. Because the coding volume was so modest, even small fluctuations can produce high pointwise contributions, making it difficult to characterize strong preferences for any single category.

Annotator 4 demonstrated a strong emphasis on Deference, which accounts for 27% of all codes. The high modified Z-score (6.41) and pointwise contribution (0.0861) both indicate that the use of Deference diverges notably from the group average. Similarly, Heroism is overrepresented (19.2%), with a pointwise contribution of 0.0462 and a modified Z-score of 1.48. Annotator 4 also uses Reciprocity more often, accounting for 31.2% of all codes. This overuse is reflected in a modified Z-score of 2.02 and a pointwise contribution of 0.0855. Furthermore, Annotator 4 did not label any text units as Not Applicable, suggesting a broader tendency to classify content within the existing MAC categories.

Annotator 5 strongly emphasized Reciprocity, allocating 41.2% of codes to this category – the single highest proportion observed for any code across all annotators. A pointwise contribution of 0.2253 together with a modified Z-score of 1.87 underscores this marked concentration, which stands out even against the substantial group-level emphasis on Reciprocity.

Notably, each annotator exhibited a distinct preference, with at least 25% of the total codes assigned to one or two specific categories. This pattern highlights that the five annotators arrived at different interpretations of the Sermon’s central moral message. For Annotator 1, the Sermon’s moral content centers significantly on group loyalty. Annotator 2, in contrast, regards much of the text as extending beyond the MAC framework. Annotator 3 primarily identifies themes of deference, while Annotator 4 views the Sermon’s moral discourse as largely about reciprocity and deference. Finally, Annotator 5’s interpretation highlights reciprocity as the dominant theme.

These pronounced individual coding preferences suggest that certain trends in the overall results may reflect a few strong individual interpretations rather than a broad consensus. For instance, Reciprocity emerges as a prominent moral domain in the aggregate results, yet Annotators 4 and 5 account for 68.3% of all Reciprocity codes. Similarly, Annotators 1 and 2 applied 87.7% of the Not Applicable codes, indicating that the view of moral content beyond MAC domains largely stems from their unique interpretations. Furthermore, Annotator 4 alone contributed 36.5% of the Deference codes, suggesting that the prominence of this category is heavily shaped by that annotator’s coding style (Figure 9).

Annotators’ coding contributions across the domains.

Despite the metrics indicating differences in interpretation at the global level, certain single-text units reveal a strong consensus. In 11 text units, all the annotators agreed on at least one code: two times on Family Values (Matt 5:27, 32a, concerning the command forbidding adultery), six times on Reciprocity (Matt 5:33, concerning oath-taking; 6:12,14,15, concerning forgiveness and being forgiven; 7:1–2, on not judging; 7:12, on the Golden Rule), two times on Heroism (Matt 5:10,11, considering as blessed those who are persecuted for righteousness or on account of Jesus), and one time on Deference (Matt 6:24, concerning the inability to serve two masters). When expanding the criterion to include text units where at least four annotators agreed on one code, the total rises to 18. In addition to the former 11, seven more units meet this threshold: two on Group Loyalty (Matt 5:20, 43), one on Reciprocity (Matt 7:3), two on Heroism (Matt 5:12; 6:2), and two on Deference (Matt 5:19a; 7:21).

Notably, the clearest dividing line between the subgroups – Not Applicable versus Reciprocity – does not reflect systematic disagreement over specific text units. Rather, it appears to be a matter of emphasis. Only in three passages (Matt 6:7, 6:33, and 7:17) did Annotators 1 and 2 code a segment as Not Applicable while Annotators 4 and 5 interpreted it as Reciprocity.

In summarizing the moral characterization of the Sermon on the Mount and the applicability of the Morality-as-Cooperation framework, several key findings emerge. First, there was broad agreement that the Sermon fundamentally concerns morality and that this morality is diverse in nature. Four out of five annotators applied each category at least once and identified moral content in at least 76.5% of the text units. Second, for the most part the Sermon’s moral teaching is about cooperation. Excluding Annotator 2, the proportion of Not applicable codes drops to 7.3%. This implies that while a substantial portion of the moral teachings aligns with MAC’s framework, there are still aspects of morality that fall outside its current domains. Third, the Sermon’s moral statements are often multifaceted, forming complex “moral molecules” in which multiple moral domains are embedded within individual statements. Fourth, while the prominence of reciprocity and deference in the aggregate results is significantly higher due to individual preferences, these domains remain salient regardless. Fifth, family values are moderately present in the Sermon, whereas there is a strong consensus that its moral teachings have little to do with property rights. Finally, there is broad agreement that fairness is not a central theme in the Sermon.

In the findings on annotator consensus, one of the most striking outcomes of this experiment was the notable divergence among annotators. Rather than uniformity, variability appeared to be the defining feature that distinguishes human annotators from their synthetic counterparts. Despite all five annotators being specialists in early Christian or biblical studies and using the same deductively formulated coding system, they arrived at distinct interpretations of the Sermon’s moral content. The data does not reveal the underlying causes of these disagreements, but they cannot be attributed solely to errors in the annotation process. The annotators did not apply codes randomly. Rather, each developed a personal yet systematic approach to interpreting the moral content. This suggests something fundamental about the Sermon itself: its moral statements may be inherently ambiguous, allowing for multiple interpretations – a characteristic that may have contributed to its cultural evolutionary success.

7 Discussion

7.1 Navigating Polysemy: Challenges of Metaphorical Language

The divergence among the annotators’ interpretations warrants further examination. One potential factor contributing to this divergence is the Sermon itself – a historical text that is both religious and highly literary, being characterized by extensive use of metaphorical language and inherently polysemous meanings.

Having tested MAC theory in the cross-cultural ethnographic data of the eHRAF, Mark Alfano, Marc Cheong, and Oliver Scott Curry note the limitations of their database, which was not collected to test MAC theory: it is organized by society, contains only outsider descriptions of morality, and exists mostly in the English language. Alfano et al. call for further studies in other languages and on direct expressions of moral values.[77]

The article at hand is a study conducted on an early Christian religious text that, although not written for the purposes of testing MAC, contains first-hand moral expressions and is written in Koine Greek. The genre and age of the text, however, make it challenging to annotate. On the one hand, the text is perhaps the best-known Christian text discussing ethics and/or morals. It has a long history of reception that a reader in Christian cultural context cannot get past; it is so ingrained in the cultural heritage that earlier interpretations necessarily affect the judgement of the reader.[78] The language of the Sermon – like religious language in general – is heavily metaphorical, dense in expression, and open to various interpretations.

A good example of a multivalent text that forms an intuitive quotation unit is Matt 7:15: “Beware of false prophets, who come to you in sheep’s clothing but inwardly are ravenous wolves.” The annotators allocated altogether five different moral domains to this passage. The general thrust of the saying has to do with (a) group loyalty: the text divides between in- and outgroups (wolves and sheep) and warns about persons who blur these boundaries with evil intent (being dressed in sheep’s clothing). This deceptive behavior belongs to the category of (b) reciprocity: the wolves are dishonest, and there may be an element of free-riding in their behavior. Furthermore, the wolves are described as “ravenous.” The domain of (c) property rights is reflected in the root term ἁρπάζω, which denotes seizing, overpowering, or snatching up, with the related noun ἁρπαγμός denoting robbery and rape. Additionally, the sheep and wolves symbolize (d) hawkish and (e) doveish behaviors on a very basic level.

The polysemous nature of the Sermon’s moral statements, coupled with their perceived authoritative origin as the direct teachings of Jesus, may have significantly contributed to their cultural evolutionary success. The belief in their divine origin ensures these moral statements are regarded as inherently “true,” fostering a conviction that the truth within them awaits discovery. Furthermore, the metaphorical and ambiguous language facilitates ongoing interpretation and reinterpretation, rendering the moral teachings perpetually open to new insights and resistant to falsification. This interpretative flexibility allows the statements to adapt to diverse contexts and cultures, thereby maintaining their relevance and utility over time.

7.2 Direct and Indirect Reciprocity

The moral domain most frequently applied by the annotators was reciprocity. Strong agreement was reached in passages such as those advising forgiveness (6:12, 6:14–15), the command to abstain from judging others least one be judged oneself (7:1–2), and the Golden Rule (7:12).[79] While some instances in the Sermon describe direct reciprocity between humans (5:24, 47), there are several instances where God is either the direct (6:16) or indirect partner in reciprocity (6:33).[80] There was some difficulty in recognizing the latter, as indicated by the high co-occurrence of the categories of reciprocity and “not applicable.”

Strategies of indirect reciprocity are common in human societies as they can be more efficient and produce more gain than direct reciprocity. Whereas direct reciprocity denotes the give-and-take between two individuals or groups (A ↔ B), indirect reciprocity allows more intermediary actors before the payback (A gives to B, who gives to C, who then gives to D, who then gives back to A).[81] The mechanism is susceptible to cheating, since the actions of B, C, etc. may be hard to monitor.[82]

Anne Katrine de Hemmer Gudme has discovered a pattern of indirect reciprocity concerning almsgiving in Mesopotamian, Hebrew Bible, and New Testament texts. For the latter, she examines verses 6:1–4 in the Sermon on the Mount. The text advises the audience to not “sound a trumpet” in the synagogues and streets when giving alms like the hypocrites do, “that they may be praised by others,” but to do it in secret because God himself will reward the humble almsgiver.[83] Despite the conspicuous word “reward” or “pay” (μισθός), our annotators were slow to recognize reciprocity in the text and read the verses in light of heroism or deference – perhaps noticing monkish virtues first. A confusing factor may also have been that explanations of MAC theory focus on direct reciprocity whereas our religious data hinges strongly on the indirect type.[84]

In the Sermon, indirect reciprocity tends to function in a “downstream” fashion: A (human) gives to B (human), and G (God), witnessing this, gives to A.[85] An all-knowing, all-powerful God acts as the guarantor of payback, ensuring the human willingness to cooperate.

Other cooperation-ensuring strategies rely, for example, on reputation management, which functions through gossip and public shows of altruism belonging to category (4) of hawkish displays.[86] It is not far-fetched to suggest that the whole Sermon on the Mount – indeed the whole Gospel of Matthew – is an effort to convince its readers of the high moral quality and trustworthiness of the Matthean community.

7.3 The Fine Line Between “Righteousness” and “Fairness”

The domain of fairness turned out to be elusive for the annotators. On the one hand, there seems to be a shared consensus about the low volume of fairness in the Sermon. On the other hand, fairness has the second smallest Alpha value, very close to zero, meaning that there is considerable disagreement about which text units contain fairness.

MAC theory views the domain as a variant of conflict resolution strategies, where resources are divided evenly or otherwise justly, according to the individuals’ input. These types of situations were difficult to recognize in the Sermon. Could the way God “makes his sun rise on the evil and on the good and sends rain on the righteous and on the unrighteous” (Matt 5:45) be an example of the even distribution of resources?[87] The concept of fairness is also much wider in everyday usage, where it often coincides with reciprocity: “an eye for an eye and a tooth for a tooth” (Matt 5:38) might be considered “fair.” A few instances of fairness may have been allocated because of the appearance of “righteousness” language (δίκαιος/δικαιοσύνη; e.g., Matt 5:10, 5:20, 6:1, 6:33). The concept has been debated in biblical scholarship for centuries,[88] and it will likely draw the attention of the knowledgeable reader. Verse 5:20 testifies that it held meaningful symbolic value in the Matthean argumentation as well: “For I tell you, unless your righteousness exceeds that of the scribes and Pharisees, you will never enter the kingdom of heaven.” Although “righteousness” is not identical to “fairness” in the English language, the two are closely related and may influence the annotation choices. Our Finnish-speaking annotators may have also been influenced by the typical translations of δίκαιος/δικαιοσύνη in the modern Finnish biblical translations as oikeudenmukaisuus or oikeamielisyys, terms that are strongly slanted toward “justness,” “impartiality,” and “fairness.” The Czech translation is spravedlnost, a term that is likewise loaded with judicial connotations.

7.4 Hawkish Doves

In some cases, the observed overlap between moral domains seemingly creates tension with the concept of a single, distinct evolutionary strategy. Annotators frequently encountered statements containing both dominant (“hawkish”) and submissive (“doveish”) behaviors within the same passage. The most notable is Matt 6:2, where three annotators selected both heroism and deference. The ideal virtue here is monkish simplicity which counts as deference. But simultaneously, this behavior can show self-restraint that can be viewed as heroic.

The same is visible in the case of persevering and accepting persecution (Matt 5:11). While allowing oneself to be maltreated by another person is easily understood as deference toward the aggressor, it may also serve as a sign of group loyalty or heroic resilience in the form of restrained power.

7.5 Fictive Kinship

An example of metaphorical language that may have contributed to disagreement among the annotators has to do with the idea of “fictive kinship.”[89] The believers are called brothers and sisters, and God is represented as their father. On the one hand, the family terminology suggests the family domain of morality. On the other hand, these terms often refer beyond biological kin to denote God and other ingroup members; additionally, in some Synoptic sayings, Jesus downplays and even challenges traditional family ties (Mark 3:31–35; Matt 10:37). The disagreement around the category – annotator 1 applied the family values domain more frequently than the other coders – does not necessarily comment about over- or under-representation of the domain in the results. Rather, it highlights interpretive differences among the annotators about the metaphorical language in question.

Fictive kinship is a concept used in sociology and anthropology to refer to social ties that are not based on real kinship (by blood or marriage) but are nevertheless perceived and acted upon as such by people.[90] The main types of fictive kinship are situational kinship, ritual kinship, and intentional kinship.[91] Situational kinship appears when the blood family is absent or irrelevant for some reason. It often arises in situations of marginality (among migrants or the homeless); within institutions such as prisons, mental hospitals, asylums, or retirement homes; in organizations such as churches, schools, universities, and some types of workplaces; or in various forms of paid care. Ritual kinship includes various forms of the concept of godparenting or shared child-rearing, so-called co-parenting. Intentional kinship refers to those types of relationships that individuals voluntarily and consensually establish, such that they come to regard certain people in their social environment as similar to members of their family and begin to treat them accordingly.[92] The range of types of social relationships that are referred to as fictive kinship is thus very diverse.

Importantly for this article, fictive kinship has also been studied in the context of social exchange and reciprocity;[93] within evolutionary psychology as a means to induce or reinforce altruistic behavior;[94] in the context of group nepotism;[95] and in the context of the metaphorical use of fictive kinship language in the New Testament.[96]