Abstract

This response to Yasuo Deguchi’s manifesto “The WE-turn” seeks to unpack two issues. First, we need to finesse our understanding of the Self by reconsidering the relationship between Doer-Internalism and Doer-Externalism as requiring both hierarchical and meshed cognitive processes that are internally multiple as well as externally embedded. In doing so, we will confront, second, the limits of analytic approaches to defining a subject acting in the world, by shifting focus from what the WE is, to what the WE does; or better yet, how the WE happens. Deguchi’s accomplishment here is transformative: abandoning the single autonomous subject as the center of agency has been warranted for myriad reasons, but never has the logic for the case been made more elegantly on ontological and epistemological grounds, nor the implications for ethics more visible. Yet, asserting the WE-turn as a relational ontology by establishing its logical consistency does not provide an experientially grounded way to supplant the single autonomous subject, with its epistemological and ethical baggage. In other words, “saying it ain’t so” does not mean that the autonomous “I” will surrender of its own accord. “We” requires from the Doer more than an intentional stance. It requires a cognitive neurological transformation from ancient cultural conditioning, especially in the West.

“Jazz is not a what. It is a how.” ---Bill Evans

“You say you want a revolution/But you better free your mind instead.” ---The Beatles

“Don’t play the music, man. Let the music play you.” ---Sonny Rollins

1 Introduction

This response to Yasuo Deguchi’s manifesto “The WE-turn” seeks to unpack two issues. First, we need to finesse our understanding of the Self by reconsidering the relationship between Doer-Internalism and Doer-Externalism as requiring both hierarchical and meshed cognitive processes that are internally multiple as well as externally embedded. In doing so, we will be confronting, second, the limits of analytic philosophical approaches to defining a subject acting in the world, by shifting focus from what the WE is, to what the WE does; or better yet, how the WE happens.

Deguchi’s accomplishment here is original and transformative: abandoning the single autonomous subject as the center of agency has been warranted for myriad reasons, but never has the logic for the case been made more elegantly on ontological and epistemological grounds, nor have the ethical implications been stated more clearly in his other writings. One implication for this essay is that Deguchi seeks, in part, to answer Emanuel Levinas’ challenge that the great unthought of Western philosophy is how to see the world through the eyes of an Other: “If one could possess, grasp, and know the other, it would not be other.”[1] Here, Levinas asserts the role of empathy in his attempt to prioritize ethics over epistemology and ontology. Yet, Deguchi’s assertion of the WE-turn as a relational ontology by establishing its logical consistency through knowing and doing does not necessarily provide us with an experientially grounded way to supplant the dominant paradigm of the single autonomous subject that acts in the world, with all its epistemological and ethical baggage.[2] In other words, “saying it ain’t so” does not mean that the fictive autonomous I will surrender of its own accord. “We” needs to be felt. As defined by Deguchi, “We” requires from the Doer more than an intentional stance. It requires a cognitive neurological transformation, from ancient cultural conditioning, especially, but not limited to the West. While Deguchi’s final draft for this manifesto elides discussion of ethics, I will draw from other writings addressing his “WE-turn” in order to address the foundations and implications for WE in a more comprehensive way than what he presents for this special issue.[3]

In order to fully grasp Deguchi’s claims here, we must have recourse to neuro-phenomenology and cognitive science, in this case, the embodied and enactive cognitive sciences exemplified by figures such as Francisco Varela, David Chalmers, Alva Nöe, Andy Clark, Shaun Gallagher, and Antonio Damasio, and even the materialist phenomenology of philosopher Manuel DeLanda.[4] And, in order to “visualize” these claims, we must have recourse to aesthetics, in this case, jazz performance as the embodied as well as distributed nature of cognitive processes both within and without the subject performing, not to mention the extended technical and environmental non-human agents and other subjects involved.[5] The question I wish to address is not just what the WE-turn is, but how it can happen, for the Doer, in lived time.

While Deguchi argues that the subject as doer “of any somatic action is not an individual ‘I’ but a multi-agent system as the ‘WE’ that includes the ‘I’” (2nd Draft, 3.1), “the emergent property of a coordinated multi-agent system…deeply intertwined with bodily processes and broader systemic conditions” (1st Draft, p. 2), he remains largely focused on these “broader systemic conditions” within which the (human) subject is embedded, in order to foreground his interest in incorporating AI into his system-subject, but generalizes this to all technical objects, while also addressing the "agency" of AI. In his account of bicycle-riding, Deguchi insists that the bicycle rider, as embodied Doer, is embedded in what Francisco Varela would call an enactive system: “Members of the “WE” include AI and other artifacts, non-human animals, and the natural environment” (2nd Draft, 1.3), all of which are actors involving “technical agents,” “environmental agents,” “infrastructure agents,” “social Agents,” and “biological agents” (1st Draft, 5), some of which constitute technological extensions of the Doer. But, as we will see, Deguchi’s account does not really embrace enaction.

As Deguchi acknowledges in several places, those internal “complex neurological processes” or “biological agents” are themselves at least as complex as the other components which delineate the extensions of the system-subject and its environs. Deguchi focuses on defining Doer-Externalism as a way to correct for the limitations of the self as a traditional Doer-Internalism (1st draft “WE-turn,” 2) which defines a Doer as a single autonomous subject acting with intention. Doer Externalism cannot completely deny Doer Internalism, just traditional internalist assumptions about the sovereign unified subject. Deguchi recognizes that this traditional view of the single autonomous and unified subject doing was overthrown by cognitive science long ago (not to mention in literary theory); yet, he has not offered a convincing model of Doer Internalism that might emerge to replace the traditional model. Given the undeniable ethical implications of Deguchi’s “WE-turn,” explicit recourse to both cognitive science and jazz performance here may help.

2 From Embodied to Enactive Cognition

In the revised version of this essay, Deguchi does briefly sketch aspects of Doer Internalism not tackled in his earlier draft, and through it, he introduces aspects of what might be considered as embodied perspectives on cognition. In particular, he defines 1. “extended” cognition into the environment (reminiscent of work by David Chalmers and Andy Clark,[6] and before them, Gibson’s “affordances”); 2. “active” and “passive vectors” of cognition (recalling Alva Nöe’s insistence that even perception is active); 3. “evolutionary acquirement of pain” and the sustained body schema that responds to external stimuli through time (reminiscent of Antonio Damasio); and finally, 4. 1–4 layers of “I” (versions can be found in Francisco Varela; Damasio; Manuel DeLanda). Following Damasio closely, he defines the four-layered structure of “I” as follows:

The foundation of the “four layered self” is a subsystem of a multi-agent system as its first layer with “WE-ness” in the form of an intrinsic multiplicity with vague boundaries. The “second layer” is a self-monitoring conscious representation with “I-ness” (which sharply opposed “we-ness”) in the form of singular individuality with clear boundaries. The “third layer” is constituted by the awareness that this ‘second layer’ extends beyond single consciousness. And the “fourth layer” which is the protagonist of the I-narrative, is constructed in the interaction of these first three layers. (2nd Draft, 6.14)

By the “multi-agent system,” he refers to the extended processes within which the subject is embedded, while this subsystem has “an intrinsic multiplicity,” as “a nested structure of a multi-agent system and its subsystems” (2nd Draft, 6.2). Yet between the multi-agent system and intrinsic, nested (cognitive) multiplicity Deguchi only finds “vague boundaries,”[7] and it is here that we may have recourse to an account of enaction, involving “participatory meaning making,” a zone where inside and outside merge, and whose boundaries are governed by contingent processes exhibiting emergent properties involving reciprocal causation, processes which occur both within the extended WE, AND amongst the Selves and Agents of the interior sub-system of the Doer comprising processes of cognitive multiplicity.

In contrast, Deguchi also addresses “decision-making,” utilizing the analytic “theory of action,” which, despite his claims for it, seems to embrace the conscious intentionality of “traditional” doer internalism in ways congruent with analytic decision theory, but not with enactive cognitive science:

As such conscious beings, when performing a somatic action, humans often consciously have an intention for that action, and while performing the action, they have a sense of agency or a sense of being the doer in real time. Even if they do not have a clear intention or a sense of agency, they can always make their intention or agency explicit if they want to.

As I will argue below, the question of intention becomes problematic when one examines carefully the empirically-verified manifestations of cognitive multiplicity modeled:[8] hierarchical and meshed relations amongst Selves and Agents seeking balance, yet often contending for supremacy for the subject’s “screen” of awarenesss, as that awareness becomes a contested site involving tension amongst internal cognitions processing the world within which the subject is embedded, which complicates Deguchi’s traditional Doer Internalism, modified as it is by his reference to action theory.

Following recent research into the paradigm of what some call 4E’s (embodied, embedded, extended, and enactive) cognitive science, when we discuss a system-subject from Deguchi’s Doer-Internalist perspective, we need to describe how the Subject contains within it characteristics of both hierarchical and meshwork organizational structures involving Selves and Agents, with a number of cognitive scientists and philosophers arguing for progressive attributes of “awareness,” increasingly from unconscious to conscious, as this internal system-subjectivity emerges to cognize and to act in the world.[9] We do so, even as we must also account for the way that subject is also embedded in a range of technical and environmental systems, as Deguchi addresses through the term Doer-Externalism.[10]

In Materialist Phenomenology (2021), philosopher Manuel DeLanda draws on Antonio Damasio’s research,[11] and notices, when describing the complex nature specifically of visual cognition within an embodied mind:

Once we multiply the kinds of agency at work in the construction of this field, a process in which populations of unconscious agents must work in parallel to produce basic content, and layers of progressively more conscious ones must elaborate and integrate that content, any privileged center of intentionality disappears.[12]

While this perspective, which argues for an empty center for agency, needs some modification, DeLanda’s point here should be extrapolated to the other senses, adapting Levinas’ perspective and referring to hearing through the mind of the Other. In other words, the hierarchy and meshworks of selves and agents suggest that the entire sensorium of an embodied cognizing subject already manifests an emergent WE before we even begin to address the extended system (including objects and environment, but also other subjectivities) within which the subject is embedded. Furthermore, as Alva Nöe points out, we must examine the relationship between cognition and action as inexorably intertwined, so that we think about even embodied sensory perception as doing.[13] But there are degrees of doing, some receptive, some performative.[14]

So, an understanding of how current research on the individual “Doer’s” cognitive multiplicity, and the scientific characteristics of emergent properties applied to cognitive Selves (Damasio’s Proto, Core, Autobiographical; Varela’s distinct forms [10 scale; 1/10th scale; 1 scale] of time cognition) and cognitive Agents arranged hierarchically as well as through mesh-works within an individual cognizer (which DeLanda calls the multi-homuncular,[15] requires us to dispense with the single autonomous and intentional subject of traditional Doer-Internalism as empirically as well as logically untenable, and to similarly interrogate Deguchi’s recourse to action-theory and the notion of intentionality.

3 The 5th E of Neuro-Phenomenology: Emergence

This shift towards cognitive multiplicity also requires us to foreground levels of autonomy, as well as the conditions of contingent bifurcation existing at each level of the multi-homucular hierarchy from within the individual subject doer, as well as within the other participant nodes throughout an extended subject-system, such as a jazz ensemble. Furthermore, we have to consider each level to possess reciprocal causation (from the bottom-up and from the top-down) with respect to these contingent bifurcations.[16] Detailed accounts from cognitive neuroscience and from jazz improvisation will make the logical claims for the WE-turn much more visible, while also providing some possible emendations to the analytic model Deguchi proposes. I argue that these principles of autonomy, contingency, bifurcation, reciprocal causation, and so forth constitute a 5 th E. Emergence. The contingent, irreversible “laws” permeating each of the embodied, embedded, extended, and enactive dimensions of cognition, manifests intrinsically, turning hierarchies into meshworks; AND extrinsically, in the case of music, in the “participatory sense-making” of musical expression during improvisation, which becomes visible even in music notation.[17]

Conversely, we need as well to account for how the system within which the subject cognizing and acting is embedded, acts upon, in fact concretely impinges from the “outside-in” upon the contingent cognitive multiplicity that constitutes the subject as Doer, through additional forms of reciprocal causality–whether viewing as a hierarchy or as a mesh. These forms of impinging occur in both “positive” and “negative” ways, as explored by those associated with “cognitive capitalism,” as well as Catherine Malabou.[18] This enables us to introduce the concept of neuroplasticity, which should be discussed with any approach to the embodied subjectivity of an experiential WE. The implications arising from the assertion of neuroplasticity might then contribute to the discussion of the WE-turn with respect to ethics in the realm of society. Finally, I would like to conclude with a discussion of brain-wave synchrony, explored in research involving both jazz performance and different schools of meditation, in order to suggest a novel way to think about the WE-turn as a measurable, repeatable, lived event. While this may seem far afield, we can simply point analogously to cross-disciplinary investigations into the role of practice in research, particularly with respect to the arts, as well as methodological concerns over “objectivity” and “subjectivity” with respect to scientific research.

4 Embodied and Distributed Cognition

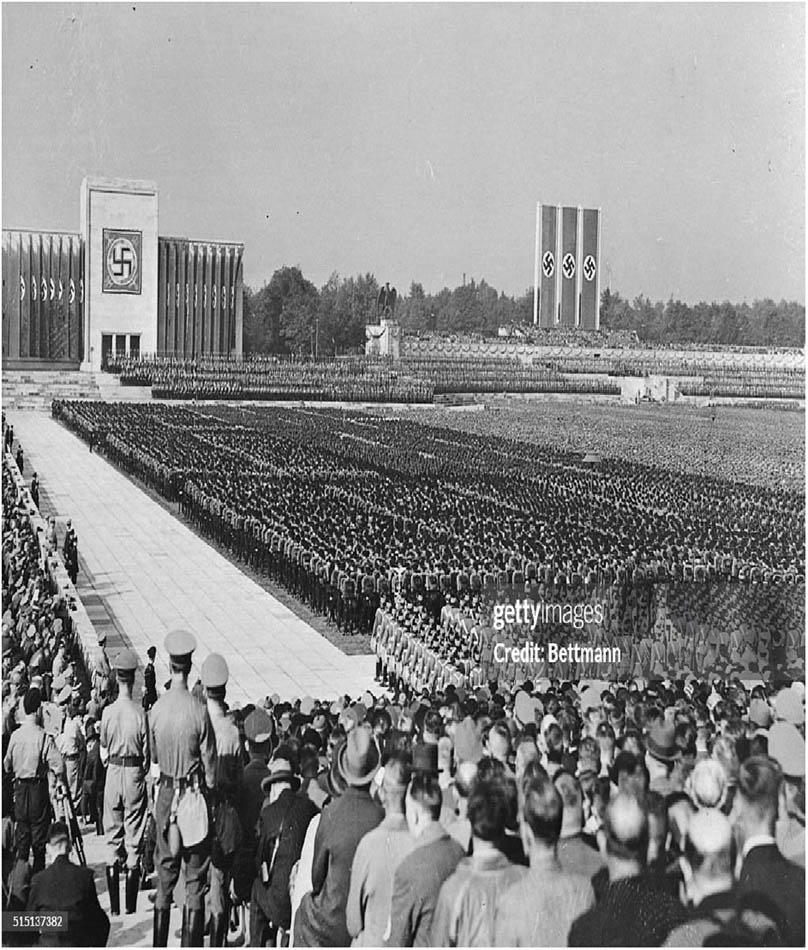

We might reconsider Deguchi’s project to shift the conceptualization of subjectivity from “I” to “WE” with respect to the terms embodied and distributed cognition, this last term used initially in computer science as well as cognitive science. This distinction has social and, therefore, ethical implications as well, when we query whether human cognition can be both embodied and distributed at the same time; and, whether that proposed merging of the embodied and the distributed natures of cognition can happen spontaneously – intrinsically from the bottom-up, or must be superimposed extrinsically from the top-down. Deguchi himself has made this relevant, given a commitment demonstrated elsewhere to extrapolate his WE-turn from the individual Doer to social organization and ethics (1st Draft, 15-30). Let’s think of two examples: spontaneous murmuration in birds and fish; and the coercive nature of totalitarian regimes exemplified by the specific mass behavior orchestrated by the Nazi regime at the Nuremburg Rally of 1938 (Figures 1 and 2):

Murmuration of starlings. Public Domain. Accessed here from The Irish Times: https://irishtimes-irishtimes-prod.web.arc-cdn.net/resizer/v2/EXNZLJ2ECLLM5W42DLVTCAZF5I.jpg?auth=9eca6fb545c5c83cddef00260fe57a4909fdc125504ea011f0df60cd64ab4b22&width=1600&quality=70.

Nuremberg Rally of 1938. Public Domain. Credit: Bettman. Getty Images. Accessed here: http://https://media.gettyimages.com/id/515137382/photo/giant-nazi-rally-at-nuremberg-1938.jpg?s=1024x1024&w=gi&k=20&c=RNTGkMd8FCsUdeG4ivwDNsTR_deVcpgwUHNnA3lQ7Io=.

Deguchi recognizes the danger of totalitarianism in his proposal for a WE-turn, and addresses in the initial draft why the totalitarian impulse does not logically follow given the constraints that he sets up through the two Incompatibility Theses, and their elaborations:

“[N]o individual can perform one’s somatic action alone.” (2nd Draft, 2.11)

“[N]o single agent can fully control any other agents whose affordances are necessary for the performance of one’s somatic action.” (2nd Draft, 2.12)

And yet, we have seen this impulse towards complete control re-establish itself globally recently through political regimes in ways not seen since the 1930’s, so that some may respond viscerally to any assertion of WE-turn ontology: since one might challenge the claims of (2) through ample historical evidence, one might conceive it as an ideological justification for coercion, much as the “free market” described by Adam Smith becomes an ideological justification for aggregating monopolies and then political oligarchies.

I bring up murmuration as an example of how the spontaneous behavior of birds and fish manifests characteristics of both embodied and distributed, autonomous and collective cognition (often as a defensive response to predation triggered by fear),[19] because it serves as a useful metaphor and model for the simultaneously embodied and distributed emergent behavior of individual performers of jazz ensembles in real time. It also hints at a possible reinvigoration for a bottom-up alternative model to top-down control that exemplifies the single, autonomous subject Doer.

Many jazz musicians speak to their interior experiences both as autonomous subjects, and as participants in a collective intelligence, feeling 1. autonomously embodied, as well as entrained with the others “in the moment”; paradoxically claiming 2. narrative control over their improvised “story-telling”; yet often 3. reacting viscerally beneath the threshold of conscious awareness to what the other musicians play; while also 4. witnessing this multiplicity, as well as experiencing the uncanny sensation of entering into the other performers’ minds during performance, a sensation that many performers associate, in the sense of folk psychology, with a form of “extra-sensory” awareness.

I will address this awareness in scientific rather than mystical terms in more detail below, but let’s simply say here that the sensation of being both an isolated subject and as part of a collective whole is not conceptually driven, nor understood intellectually, but experienced initially as affect, reminiscent of what humanistic psychologists call a “peak experience.”[20] Is it possible for human beings to be both embodied and distributed at the same time? This raises still another question: can we conceive of a morphogenesis from embodied to a distributed aesthetic cognition that remains embodied? Can the WE-turn be learned, not only conceptually, but cultivated performatively as affect? Here, it might help to introduce an experiential distinction between receptive and performative distributed aesthetic cognition through the concrete examples of cinema and jazz, as a way to suggest how the WE-turn can be learned.[21]

5 Emerging WE: Receptive and Performative Distributed Aesthetic Cognition in Cinema and Jazz

We can pursue this question by exploring an analogy between two forms of parallel processing in computer science and the possibility for an embodied experience of distributed aesthetic cognition. For the first form of parallel processing, I refer to primitive serial computation, often called “time-sharing.” I suggest that “time-sharing” serves as a precise analogy for the receptive cognition of multiple points of view by a cinematic observer of a cinematic event through time, enabled by montage (with respect to the shift from “liquid” to “gaseous” perception across the axes of time and movement images discussed by Gilles Deleuze in his first book on cinema).[22]

For the second form of parallel processing, I refer to global effects enabled by the networking of autonomous hardware architectures and software processes, so that networks can generate computing power greater than the sum of the contributing computational components, in an example of an artificially-generated emergent property.[23] This second architecture was created (by Second Order Cyberneticists such as Warren McCullough at the University of Illinois and others) to mimic what cognitive scientists now call neural nets in the brain, to test the possibility of an alternative model to the top-down computational model in computer and cognitive science, dominant since the work of von Neumann and others.

I suggest that this second form of parallel processing serves to model the active, spontaneous performance of jazz musicians demonstrating advanced improvisational ability. We can describe in detail this form of parallel processing across the N-dimensions of musical language (melody, harmony, harmonic rhythm, percussive rhythm) as well as instinct and affect (sensory, proprioceptive, emotional), with respect to embodied cognition; and across the boundary conditions between multiple subjects participating in a shared sonic environment where musical “language” constitutes just one part of a consensual realm for what cognitive scientists such as Varela and Ezequiel Di Paolo call “participatory sense-making” through which affect is also shared, and may indeed drive that sense-making--a sense-making, I would point out, which remains free from semantic content.[24]

First, let’s examine “time-sharing.”[25] When the now obsolete mainframe computer (constructed utilizing the model of the top-down computational paradigm)[26] with multiple terminals sending data from these multiple inputs, it remains able to process only ONE bit of information at a time (although at very high speeds). This is due to the von Neumann bottleneck, the computational limit of a single (yet very powerful) processor. It can get around (compensate for) this limit through a process called “chunking.” Chunking breaks up the syntagmatic sequence of code emanating from the separate terminals, disassembling the code in the order that it receives each bit in real time, and then sends it through the processor one bit at a time. The mainframe then reassembles the distinct sequences originating from separate terminals and then stores them in memory on “the other side” of the bottleneck, so to speak.

Similarly, during a complex montage sequence such as the baby carriage careening down the staircase in Battleship Potemkin (1925), or its parody in The Untouchables (1987), each shot in the montage sequence represents a different point of view – the different subject position of each portrayed witness to this careening baby carriage, each anticipating a range of consequences for each moment of that chain of events, from each subject position.[27] Thus, the different points of view, presented to the cinematic viewer one at a time, each of which persists in the memory within that viewer, constitute a widening of the “bandwidth” of that viewer’s cognition of that chain of events. Then, the chain of witnessed causalities and imagined potential consequences, vicariously cognized from these different subject positions (of the portrayed observers within the filmed event), and always open to the separate contingent anticipations of the cinematic observer (which defines “suspense”), becomes presented to that cinematic observer, one image at a time.

Cinematic montage constitutes the artistic construction of a distributed aesthetic cognition of human events within the mind of the single, embodied cinematic observer, by representing the points of view of multiple subject positions, so that the cinematic observer cognizes events as a distributed subjectivity, from multiple points of view that exist in parallel. Each distinct point of view, presented one at a time through the metonymy of flickering images, persists in the memory even as new images continue to enter the cinematic observer’s awareness. This technologically mediated, yet distributed aesthetic cognition remains receptive, because the cinematic observer cannot reach out and project into each mimetically represented subject position (not to mention actually embody that position), nor can that observer act, in response, in the world.

But in a way that seems impossible for any single embodied individual to accomplish, the cinematic observer reconstructs each point of view, in parallel, beneath the threshold of conscious awareness (due to the speed required for cognitively processing still frames entering the movie projector at 24 feet per second – before the onset of digital imaging), by sustaining each point of view within memory. This aesthetic hallucination enables the cinematic observer to absorb, react, and then to anticipate alternative futures (as in the suspense which sustains pity [reaction] and terror [anticipation]) for each fictional observer with respect to the fate of the baby in the carriage.

We should remember the roles that reaction and anticipation play in the receptive mind of the cinematic observer here – the observer’s capacity to follow alternative possible outcomes for a given event and from a range of subject positions, as some possible outcomes are closed off, and other outcomes emerge as potential alternative resolutions to the otherwise relentless metonymic chain of events, from one moment to the next. We need now to address this question of the role of reaction and anticipation as cognitive processes which exist both “above” and “beneath” the threshold of conscious awareness, with respect to the performative embodied, yet also distributed aesthetic cognition of jazz musicians.

Let’s compare this conception of a technologically mediated, receptive, distributed aesthetic cognition (a WE-turn), with that of an emergent, performative, embodied and yet distributed cognition enacted by jazz musicians during improvisation, with respect to the more technologically sophisticated form of parallel processing involving networked computers, each initially with a single but now with multiple processors, whose combined computing power is greater than the sum of the individual computers that have become networked: neural nets.[28] Now, neural nets generated by an array of computers are a disembodied form of emergent artificial intelligence. But, when compared to the behaviors of a jazz ensemble, jazz improvisation involves an performative form of distributed aesthetic cognition, which remains embodied, (from which it first emerges), as that cognition expands to embrace the sonic subject positions of all others likewise engaged in improvised performance – with the other subjects likewise engaged in cognitive expansion outwards, each from their embodied condition.

We will need to examine the music theoretical, and then the neuroscientific bases for anticipation as well as reaction during the embodied cognition and performance of improvised music, drawing on this research to argue for an emergent, embodied yet distributed form of aesthetic cognition (a different kind of WE-turn). Yet, in both cases, we are making claims for art’s capacity for expanding the cognition of the participant (whether receptive observer or performing artist), altering their cognition and comprehension of events in the world by rendering their subject-position permeable. Here, we move definitively towards an enactive model of cognition.

6 How Jazz Happens: The Role of Emergence in Participatory Sense-Making

A recent essay (Rosenberg, 2021) examines the initial conditions for an emergent jazz performance (Pittsburgh jazz drummer Roger Humphries’ band RH Factor) as both a hierarchy and meshwork of participatory musical sense-making involving the four axes of melody, harmony, harmonic rhythm, and percussive rhythm in a flowing consensual domain contingently emerging from the “calculus of music notation” represented by the lead sheet of the song form being performed. This comparison of a flowing domain with musical notation was explored in detail in an earlier (Rosenberg, 2010) essay addressing the cultural differences in musical cognition (European classical; Third World/European hybrid jazz) with respect to calculus and phase space, drawing on competing models of time (reversible; irreversible) from the philosophy of science.[29]

Taking into account the individually embodied experience of “flow,” and the distributed yet also embodied experience of “groove,”[30] we find that a minimal percussive-rhythmic gesture from drummer Humphries is all that is required to establish an affective as well as conceptual consensual domain amongst the musicians, a felt, immanent domain which is contingently capable of generating practically infinite variations with respect to the deterministic musical trajectory represented by the song’s “lead sheet” (in music notation), variations of which are fully conceptualized as well as embodied proprioceptively by the gifted musicians involved, prior to performance, through long hours of practice.

In ways reminiscent of claims made for Gilbert Simondon’s “trans-individual,”[31] which is also “pre-individual,” this flowing, irreversible domain, initiated by percussive rhythm, has characteristics of both hierarchical and meshwork organization through which the other distinct axes of harmonic rhythm, harmony, and melody emerge. It can be likened to the geometry of phase space in N dimensions, with each dimension (minimally: melody, harmony, harmonic rhythm, and percussive rhythm) enabling the initiation and exfoliation of processes of bifurcation from one moment to the next. It begins with percussive rhythm, so there is an implied hierarchy of musical textures, but the relationships amongst these (minimally) four dimensions interpenetrate in conceptually as well as cognitively fascinating ways.

As Gilles Deleuze writes of the significance of this pre-individuation:

The prior condition of individuation, according to Simondon, is the existence of a metastable system…By discovering the prior condition of individuation, he rigorously distinguishes singularity and individuality. Indeed, the metastable, defined as the pre-individual being, is perfectly well-endowed with singularities that correspond to the existence and distribution of potentials.[32]

It is important not to get distracted by the term metastable (from oncology), because it applies here to an irreversible yet immanent field,[33] through which individuation, the phenomena of singularities (defined as events of contingent bifurcation), emerges as a “becoming” which unfolds possible future states of the system as inherently virtual potentials present at any instant.

For Simondon, pre-individuation describes a field of all possibilities that, while flowing through time, closes off those virtualities, as their potential for emergence passes. Here, we can recognize that Simondon is modeling the immanent pre-individual on the geometry of phase space that Ilya Prigogine began to deploy in order to model self-organization or “emergence” in the form of thermodynamic processes “far-from-equilibrium” in his research begun during World War II investigating the principles of the role of irreversibility, first during the “end-game” of equilibrium thermodynamics, and then in self-organizing processes at the boundary between non-living, and living.[34] In jazz, these processes of bifurcation occur (minimally) in all four dimensions, at all times, during a jazz performance: less so in standard jazz rooted in a specific song form; yet, dominant in the performance of free jazz with no “road map.”[35]

By reference to Prigogine’s work on phase-space models of emergence, we can find similar recourse in the cognitive science of Francisco Varela and others, who have applied the geometry of phase space to cognitive behavior, beginning with Varela’s work on the cascading bifurcations present in epileptic grand mal seizures; and, for our purposes, his modeling of the interior looping inherent in the registering of sensory data and its interactions with memory templates at different speeds, in what Varela calls the cognitive multiplicity of “the specious present.”[36] What we will discover is that the principles of contingent bifurcation in N-dimensions, which are central to theories of emergence in the hard sciences, as well as in the cognitive multiplicity of Selves and Agents[37] which are spelled out in 4E’s cognitive science, have been precisely implicated in jazz performance. But first, we must address the consensual domain of music as both a conceptual and affective realm within which each musician is embedded.

7 Jazz as Participatory Sense-Making: Emergent, Enactive Processes

Classical and jazz musicians process time differently, and this difference is extrinsic, visible even in music notation. These differences point to a distinction found within the philosophy of science between time-reversible and time-irreversible models of physical systems: Classical – precise, deterministic trajectories that are symmetrical whether viewed going forwards or backwards in time; or, Jazz – complex, contingent processes not reducible to linear trajectories, and which are irreversible with respect to the evolution of a system. Whether towards disorder, as in equilibrium thermodynamics, or towards greater orderliness, as with emergence found in non-equilibrium thermodynamics.[38]

When compared with the Swing Era (1920–1945), from the Birth of Be Bop (1945) to the appearance of Free Jazz (@1960), jazz evolves dramatically towards greater complexity, for both improvisation and composition. It demonstrates characteristics of emergent properties associated with irreversible processes, and the geometry of phase space can model these emergent behaviors in jazz improvisation and composition. One central attribute of emergent irreversible processes occurs with bifurcations, which can only be modeled successfully through the geometry of phase space.

Bifurcations occur during improvisation in the (minimum of) four dimensions of melody, harmony, harmonic rhythm, and percussive rhythm. With respect to melody, in the movement of a standard harmonic resolution from consonance to dissonance back to consonance (ii-7 to V7 to I major 7), any number of modes (derived, for example, from major, minor, harmonic minor, or melodic minor) or pentatonic scales might be brought to bear over any one chord in a sequence. The improviser is able to “choose” contingently which to bring to bear, or might utilize several, in parallel, to generate contrast (as in “question” and “answer” alternations), when constructing melody. Given that each melodic mode or scale has a particular aural “flavor” (because of the position of ½ steps within the scale), a range of tonal effects may be brought to bear, with a deviation from one to another generating difference, a “surprise,” with respect to a listener’s expectations.[39]

In harmony, whether chords are constructed in triadic, quaternal, or other configurations, a bifurcation may occur when the inner voicings of a chord might generate a “fork-in-the-road” which can lead to an implied or explicit deviation from the tonal center for that chord, and even the sustaining of poly-tonal textures where the performers perform in complementary or competing key signatures. Two examples: when the appearance of two tritones in a single dissonant V7 chord, due to altering the harmonic sequence beyond the seventh degree such as with a V7b5 (G7b5:) chord, might point to two possible tonal resolutions, as in a (bII7) Db7b5 chord substituting for a (V7) G chord capable resolving to (I maj 7) C major, but which also implies a resolution to (#IV maj 7) Gb major. Here, one could deploy melodically a range of scales applicable to a dominant chord in the key of Gb major, which would be quite distant tonally from a resolution to C major.

Or, with quaternal harmonies (voicings in 4ths), we have chords which are capable of even more ambiguity, so that a D-11 chord “built” in such a way might imply the keys of C major, A minor, F major, Bb major, D minor, and so forth, enabling the improviser to alternate, or even to juxtapose several contrasting tonal centers within a given solo improvisation. There are many more sophisticated ways to substitute chords to implicitly or explicitly introduce parallel tonal centers (also called polytonality), as with triad pairs (A Maj triad OVER an Eb Maj triad), implying multiple tonalities, but which also describes an Eb7 (alt) chord, implying the Locrian mode of the E melodic minor scale. I am skipping discussion of polytonal scales here simply to simplify.

With harmonic rhythms, multiple parallel chord progressions can occur (compete) simultaneously for the attention of the improvising soloist as well as the audience, as when each instrument performing a blues may follow a different form of the 12 bar blues (Chicago, Jazz, Parker, Coltrane etc.) at the same time, while all these different sequences existing in parallel actually can synchronize together during performance. This is because any version of the 12-bar blues has a target chord of a subdominant IV7 in the 5th bar of a 12-bar sequence. This 5th bar serves, analogously, as an attractor state for the polyphonic, polytonal, and polyrhythmic textures of a sophisticated contemporary blues/jazz performance.

Music Notation for a “Chicago” 12 Bar Blues {: I7/IV7/I7/I7/IV7/IV7/I7/I7/V7/IV7/I7/V7:} which in the key of C major reads {: C7/F7/C7/C7/F7/F7/C7/C7/G7/F7/C7/G7:}

Music Notation of a Standard Jazz Blues {: I7/IV7/I7/I7/IV7/IV7/I7/iii-7 VI7/ii-7/V7/I7/V7:} {: C7/F7/C7/C7/F7/F7/C7/E-7 A7/D-7/G7/C7/G7:} (ii-V of ii/ii-V7 of I)

Music Notation for the 12 bar “Blues For Alice” by Charlie Parker {: 1. Fmaj7/2. E-7b5, A7b9/3. D-7, G7/4. C-7, F7/5. Bb7/6. Bb-7, Eb7/7. A-7, D7/8. Ab-7, Db7/9. G-7/10. C7/11. Fmaj7/12. D Maj7:}

Music Notation for a “Coltrane” 12 Bar Blues with “Giant Steps” chord sequences: {: 1. Fmaj7→Ab7/2. Dbmaj7→E7/3. Amaj7→C7/4. Fmaj7→B7/5. Bb7/6. Bb7/7. F7/8.A-7→D7(alt)/9. G-7/10. C7(alt)/11. A-7→D7/12. G-7→C7:}

We can see how completely divergent these complex blue forms are from the simplest 12-bar structure, involving increasingly complex and sophisticated harmonic motion. And yet, we can identify their roots in the blues. That musicians can diverge in these ways, and yet still remain grounded by the periodic attractor of the subdominant chord in the 5th measure, testifies to the simplicity of the form, as well as to the possibilities for polyphonic, polytonal, and polyrhythmic textures that can tax even the most sophisticated of instrumentalists.

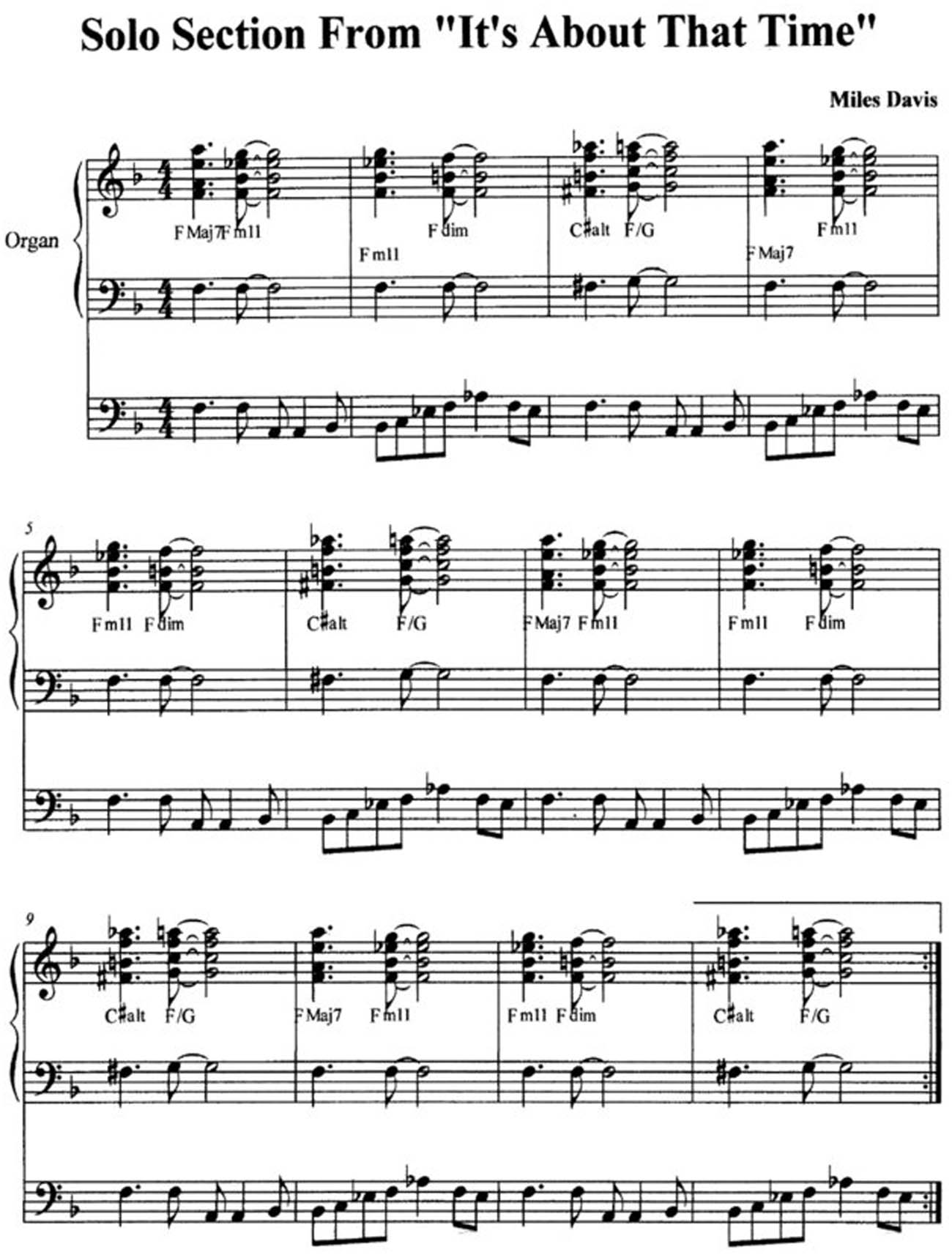

Another example is the amazing Miles Davis composition “It’s About That Time,” from In A Silent Way (1969), in which during the solos section, the difficult, a-tonal chord progression completes a cycle of three bars, while two bars of a blues funk bass line repeats, so that the attractor state occurs when the double cycle repeats every six bars. The soloist can choose: During this recording, John McLaughlin follows the chord progression, carefully deploying chord-scale resources; Wayne Shorter deploys altered blues scales over the ostinato funk bass line; and Miles concludes by alternating from one to the other sequence, juxtaposing them (Figure 3).

Solo Section from Miles Davis, “It’s About That Time.” Transcription by Martin E. Rosenberg In: “Jazz and Emergence, Part One,” p. 243.

With respect to percussive rhythm, Kenny Clarke, Art Blakey, as well as Max Roach began introducing poly-rhythms (defined as distinct, simultaneous time signatures) into the rhythmic “language” of Be Bop. Through this innovation, they were enabling the possibilities for all the instruments to imply different rhythmic sequences, either by shifting from one to another, or by playing against the established rhythm of the song so that the listener will be hearing 3/4 time against 4/4 time, or 7/4 time against 4/4 time at the same time (with many other possibilities). We then can sense a hierarchy of rhythmic textures, as well as a hierarchy of tonal centers, with “travel” by a single instrument (or by all the instruments for that matter) between time signatures a common practice, as it is with competing tonal centers.[40] These bifurcations can occur spontaneously during improvisation, and are reversible in the sense of “reciprocal causation” (from 3/4 superimposed on 4/4 or 4/4 superimposed on 3/4); they come to be utilized deliberately during the composing process.

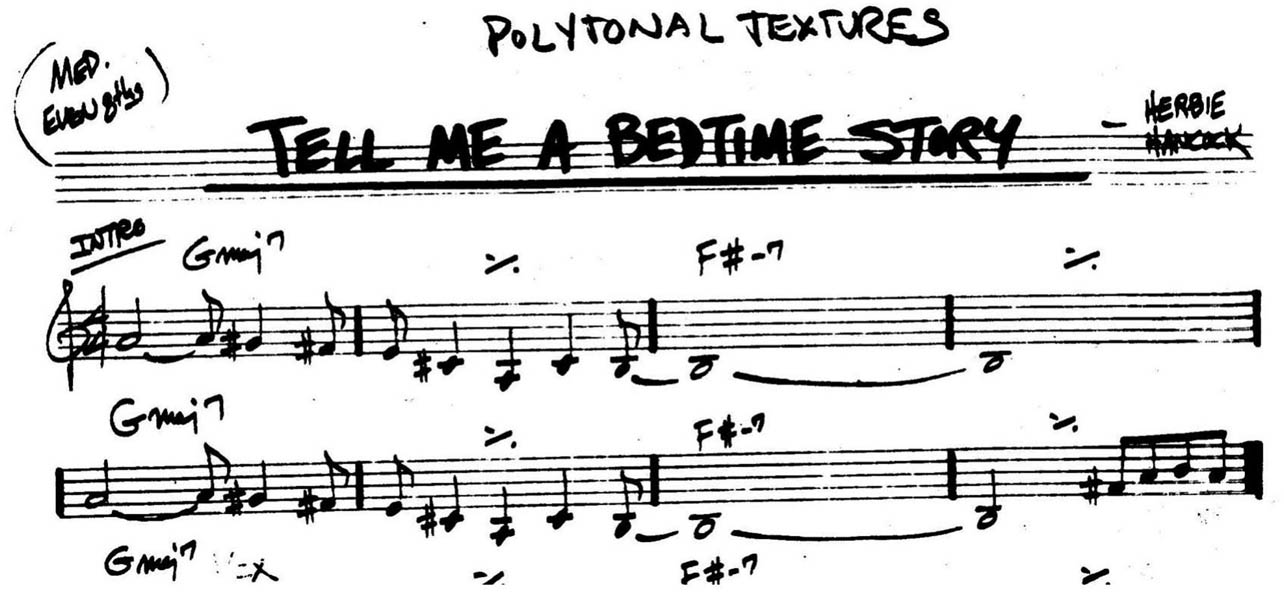

Take, for example, the “Introduction” for Herbie Hancock’s “Tell Me A Bedtime Story,” in which the melody is derived from the D Lydian Scale (A Major from the fourth degree, with three sharps), while the harmony anchors the song in G Major (with 1 sharp). This “Intro” contains an exquisite b2nd dissonance with G# in the melody over a G Maj chord (Figure 4).

“Intro” to Herbie Hancock, “Tell Me A Bedtime Story.” From: The Real Book. Privately published, 1st Edition 1975.

The birth and precipitous evolution of Be Bop (as opposed to “swing” jazz) is due to the spontaneous and deliberate deployment of bifurcation (or “individuation”) that is a characteristic of creative invention, broadly construed, in both improvisation and composition.

Another property of emergent systems, which depend upon systemic bifurcation, is aggregation, which have been identified in these same four dimensions. The phenomena of initiating, then sustaining the conditions of polyphony, polytonality, and polyrhythms through bifurcation enable this. John Coltrane’s cycling through multiple tonalities by means of pentatonic scales, matched by McCoy Tyner’s contingent, autonomous cycling of tonalities through voicings in 4ths in A Love Supreme (we should mention the roles of Jimmy Garrison’s bass lines, and Elvin Jones’ trademark percussive polyrhythms), demonstrates processes of aggregation with respect to melody, harmony, harmonic rhythm and percussive rhythm. A heterogeneic union of distinctly autonomous, yet contingently synchronized melodic and harmonic periodicities emerges, in part because of how easy it is for the listener as well as the performer to hear the divergent potentialities of these tonally ambiguous chords, to hear and follow as well the contours or shapes of pentatonic melodic ideas, no matter how distant (not to mention dissonant) they might be harmonically, at any given moment.

We can think of free jazz as a logical extension of these principles. Wayne Shorter’s more recent ensembles especially exemplify this: He says, describing performing without the roadmap of a song form: “How can you rehearse the un-known?”, implying that, given that the role of bifurcations and aggregations – the potentials for futurity – are so myriad, that one cannot map the trajectories out ahead of time, for every player.[41] With free improvisation, without an existing song form, or initiated by a fragment of a song (a typical Shorter method), the performance generates cascading bifurcations and aggregations, so that the periodic attractors (used to model self-organizing processes in physics and especially chemistry) exemplifying the evolving structure of Be Bop improvisation and composition enabled by bifurcation, give way to the strange attractors (used to model chaos as well as complexity), which are enabled by both bifurcation and aggregation that exemplify Free Jazz, as David Borgo has described, with the terms swarm and synch, respectively.[42]

In addition, there are two processes, identified as feedback loops, which seem to correspond to Deguchi’s insistence that complete control over affordances cannot be accomplished in part due to temporal extension, because “those necessary for action extend across time in ways that preclude conscientious individual control – one cannot simultaneously control present conditions and their historical preconditions” (5–6). Here is where a reactive form of embodied cognition begins to emerge, which begins to complicate our understanding of intentionality.

Feedback Loops, a distributed phenomenon and a crucial characteristic of emergent systems, occur at very fast cognitive speeds amongst members of the ensemble during the flow of improvisation; and, at slower cognitive speeds during the composing process. The slow feedback loop involved in the composition of Charlie Parker’s tune “Ornithology” begins an extended process with Dean Benedetti’s tape recordings of Parker’s solos over “How High the Moon,” distributed amongst Parker’s player/disciples, who transcribed them to use as the basis for further compositions (demonstrating bifurcating melodic, harmonic, harmonic rhythmic, and percussive rhythmic processes), then culminates in the composition “Ornithology” (attributed to trumpeter Bennie Harris). This system persisted throughout the Be Bop era, with initial tunes such as “I’ve Got Rhythm” undergoing multiple, increasingly sophisticated iterations.

These loops differ in scale, but not in kind, from the feedback loops of individuals within an ensemble responding viscerally to each other at very fast cognitive speeds beneath the threshold of conscious awareness “in-the-moment.” This difference with the cognitive speeds of the performers involved is especially significant. A classic example of fast feedback occurs in the recording of Stanley Turrentine’s “Sugar,” in which guitar accompanist George Benson unleashes a flurry of 16th notes beneath Turrentine’s solo, at which time the soloist reacts instantaneously by altering the pulse of his soloing from 8th notes and 8th note triplets into this faster (16th note) metrical realm involving much more complicated syncopations (also called “double-time”).[43] Let us now examine carefully the cognitive neuroscience of improvisation “in the moment,” for here is where we begin to fill in the territory for the WE which Deguchi only hints at in his final draft, which must begin with an account of extended cognition.

8 Extended Cognition: The Instrument and Performer as We

So now we can describe jazz performance as a consensual domain in terms of the Four WE’s: The ensemble as WE; the instrument and performer as WE; the internal doer/performer as WE; the ensemble and audience as WE. As I have discussed the shared template of the musical song-form and the “language” of musical expression, as well as the shared felt sense of “groove” which emerges from each individual performer’s sense of “flow,” and which then distributes or “melds” throughout, pervading the ensemble.

Let’s now address the relationship between instrument and performer as an extension of embodied cognition, structurally coupling the human musician and the non-human instrument. I say structurally coupled because we should not conceive of the instrument as simply an extension of the body, as suggested by the word prosthesis.[44] The talk about affordances should not ignore the role that resistance plays in this coupling, which the term prosthesis glosses over. For example, with a drum set, the sticks rebound off of cymbals, which are put in motion triggered by their hits; and off of the drum skins that are tuned, with respect to pitch, and have variably taut tension. The drummer’s skill set requires sensitivity to pitch and tension. Through resistance, the instrument can claim a certain non-human agency. Significantly, we also need to examine how the ways that a body couples with an instrument actually shapes the proprioceptive pathways within the performer, with different instruments producing starkly different pathways which extend throughout the body. Let’s begin with the guitar, before extending the discussion to all instruments.

The ergonomics of guitar design has to do with how humans couple with the guitar body and neck (and its sonic extensions through electronics), in order to enable the most efficient performance of the hands (and/or picks) manipulating the strings on the fretboard and over the sound hole (and through electronic pickups) for generating intended (and unintended) sounds. We will emphasize this discussion of the extended cognition of guitar performance in terms of jazz improvisation, because jazz improvisation requires spontaneous performance in the context of contingently shifting and often highly abstract musical structures that are every bit as complex as classical music (if not more so). Thus, it challenges the ergonomics of guitar performance at the most sophisticated level. First, for contrast, let us compare a classical guitarist and a jazz guitarist with respect to Deguchi’s Doer-Externalism with the coupling of body and instrument.

9 Structural Coupling of Body and Guitar: Andres Segovia and Joe Pass

In 1975–1976, I had the good fortune of seeing two extraordinary concerts at Boston Symphony Hall involving two pioneering solo guitar performers: Andres Segovia had helped define the modern classical guitar, and was initially responsible for developing an extensive classical repertoire through his own transcriptions and by inspiring composers to write guitar music with his prodigious abilities in mind. After an already substantial career as a featured Be Bop jazz ensemble soloist in hundreds of concerts and recordings, Joe Pass had, almost single-handedly, transformed the electrified jazz guitar into a solo instrument in the series of albums aptly titled Virtuoso. Joe Pass remains an exemplar of jazz performance excellence even today, long after his passing.

In his early 80s, Segovia had to be guided by an assistant to his chair and footstool, in the center of Symphony Hall. He sat down and adjusted his feet so that his left foot became raised slightly on the footstool, while his right foot was placed flat on the ground, pointing out towards the audience. He then placed his Ramirez guitar in such a way that it became cradled on the back edge of the guitar body in three places: on the lower bout by the tail piece against his right leg; on the bottom indentation between the upper and lower bout against his left leg; on the top upper bout against his chest, with the neck of the guitar at roughly 45 degrees from vertical. Checking for the stability of the guitar by dropping both hands, and occasionally pushing against the guitar to check for unwanted wobbling, Segovia then poised, with the fingers of both hands hovering over the guitar, his left hand over the fretboard, and his right hand above the strings over the sound hole.

What I noticed immediately as his playing began to fill the hall was a total surprise: there was no amplification. If I remember correctly, the first piece was the Bach Cello Suite # 1, transcribed to D Major with a drop D tuning, which extended the normal range one whole step to take advantage of the octave resonance of the open sixth string with the fourth string normally tuned to D, one octave above. Segovia was able to project the sound of that relatively small classical guitar throughout the hall, seating thousands. This was accomplished through masterful technique and enormous resources for the control of subtle articulation in the fretting and plucking of strings (called “touch”), and through the resonance of the wood of the instrument, with scalloped interior bracings and the vibratory quality of the soft-wood soundboard (spruce or red cedar) with the center hole, and the harder woods on the back and sides (Brazilian rosewood), and with the capacity of gut strings to sustain vibration against steel frets as the finger held down the string on the very hard (ebony) wood of the fretboard. The placement of the edges of the guitar body against the stability of three parts of Segovia’s body enabled the wood of the guitar to vibrate without the impediments that would occur from cradling the sides of the guitar against the body.

Three items are worth a bit further exploration here: the first, a question of resonance of the instrument body; the second, of the resistance of the strings in their responsiveness to both the fretting (height) and plucking (tension) fingers; and, third, a question of the range of notes available to the musician. First, given Segovia’s accomplishment, it would be hard to conceive of a need for the instrument to be louder, and one wonders if a guitar body could be designed for greater volume, whether that would impact negatively on the range and subtlety of the palette of sonorities. For the second, if the strings’ relationship to the fretboard were adjusted, whether that affect the range of dynamic articulations. Third, there’s the question of the range of notes that one is capable of playing on a guitar, when compared to a piano, and one wonders how much further than a sixth E string dropped to a D could one go, and still have performative control over the instrument’s sonorities, and intonation.[45]

How would the requirements change if one were performing as an improviser and not performing by rote a memorized piece of music? These questions were apparent to me, because the previous year, I had seen the jazz guitarist Joe Pass play, and despite the differences between a classical and electric jazz guitar, and differences in repertoire, and in the technique and articulation of musical traditions requiring huge differences in approach to playing the guitar, some of the same questions had occurred to me at this previous concert.

When I saw Joe Pass, the evening of Christmas Day 1975, the concert was supposed to be a trio performance of guitarist Pass, the singer Ella Fitzgerald, and the pianist Oscar Peterson. Unfortunately, Ella Fitzgerald and Oscar Peterson were supposed to fly in from Montreal, Canada, that day, and their plane flight got cancelled due to a snowstorm. Boston Symphony Hall was filled to capacity for this landmark event. As the evening commenced, this highly sophisticated audience had become restive, and the management was forced to cancel the event and refund the money. But as luck would have it, Joe Pass agreed to play for an hour (he played longer), and the audience ended up refunded and rewarded for their patience. Joe Pass took to the center of Symphony Hall’s cavernous stage with his guitar, his chair, and his small amplifier, and filled the hall with an unparalleled demonstration of guitar technique, fulfilling the designation “guitar as orchestra” genre of solo jazz guitar.

Like Segovia, Pass sat down on his chair, both feet flat against the floor, but without a foot stool, and, with the aid of a guitar strap, he cradled his guitar lightly between his legs, with the flat back of his guitar against his chest, with the neck and fretboard, at a steeper angle than Segovia used, so that the neck was close to his face. This guitar, a D’Aquisto configured similarly to a Gibson ES 175, was an archtop jazz guitar with two violin-like “F” holes instead of a round center hole. The body was made of maple, with the top made with thin laminates glued together, while the neck was mahogany, and the fretboard had hard ebony and steel frets.

Given the lack of acoustic resonance in the laminated maple top, and in contrast to Segovia’s classical guitar’s solid spruce top, it had a one single coil pickup (in contrast to his Gibson ES 175 which had two “humbucker” pickups), and the steel strings were magnetized so that the coils in the pickups could pick up the magnetic field generated by resonance of the notes from the strings. The tension of the steel strings was much greater than that of the nylon classical strings, and also hovered lower over the fretboard for ease of fretting chords and plucking individual notes. This jazz guitar is designed to enable very fast articulation. Pass waited as some sense of balance communicated itself to him, and then he paused, his right hand and its fingers positioned over the strings, the thumb and forefinger holding a pick, and the middle, ring and pinky hovering much like a classical player’s fingers in readiness to pluck the upper strings, while his left hand began forming the position for depressing a string for individual notes and fretting multi-note chords across strings.

Pass performed mainly tunes from the American (standards) Songbook, including Duke Ellington compositions he had and would soon again record with Ella Fitzgerald. By combining melody, chords, bass lines, and counterpoint, he was able to make the guitar sound like an orchestra, or at least as complex a range of textures as a piano might accomplish. More to the point, after he played through the song once, Pass was, in fact, improvising all of these textures. As the concert progressed, however, I noticed that Pass was actually engaging in some sleight of hand: he really was not consistently playing bass, chords, and melody all at the same time, in the way that a pianist can bring to bear ten individual fingers to the keyboard in order to perform simultaneously a range of musical textures.

Even Joe Pass’s astonishing technical abilities had limits, an instrumental constraint which made sustaining the rhythmically swinging improvisation of bass, chords, and melody all at the same time for any length of time impossible on the instrument. But, by switching deftly amongst the fingering of bass lines, strumming and fingerpicking chords (with a hybrid pick AND fingers technique) with a swinging rhythmic cadence, and then introducing at every opportunity astonishingly complex linear flights of melody, from the audience’s perspective, Joe Pass made it seem as if he was doing all of these things at once. He could accomplish such rapid alternations for short periods, suggesting that by tackling each technique one at a time, these techniques became sustained by the listener in memory as if they existed in parallel, very much like the ways a cinematic observer sustains multiple points of view even though cognized one at a time.

In short, the design of the two instruments reflected different standards for embodiment and balance, for resistance with respect to string tension and height from the fretboard, as well as the heights of the frets themselves from the fingerboard, and for projective resonance (acoustic or amplified), and the performers were adapting to the instrument’s configuration to emphasize the specific musical characteristics (classical or jazz) required to perform. Despite the slight differences in proprioception, they were tangible enough to ascribe distinct agency to each instrument with a distinct effect on the proprioception of the two players. With other instruments, however, the differences in how their non-human agency affects proprioception become much more stark.

If we can first acknowledge that the language of “participatory” musical “sense-making” remains the same from instrument to instrument, and that the sense of “flow” and “groove” expands from the embodied condition to a distributed collective, then we can focus on how completely different the proprioceptive pathways would be for a player of any instrument: a drum set, a saxophone, a piano, an electric guitar, a trombone, a string bass, a vibraphone, a flute, a trumpet, an electric bass – each instrument has agency in shaping how a player couples with and then performs on each instrument, in shaping the proprioceptive pathways permeating the embodied system-subject.

Just think of the significant differences, proprioceptively, between a player performing on a string bass and performing on an electric bass: in jazz performance, one mostly stands playing string bass; one mostly sits playing electric (unless you are Jaco Pastorius). Even though the instruments share the range of musical notes, the articulation becomes quite different from one instrument to another, especially taking into account the role of bowing on the string bass, versus plucking the strings much like a classical guitarist (putting aside “slap” technique in “funk” jazz).

Comparing a string bass player with a trombonist, the musical language, its sonic range, and often its musical function share similarities. But for the player of a trombone, the variable right arm extension and articulation, coupled with the role of the mouth’s embrasure, makes the differences in proprioception profoundly different from the player of a string bass.[46] Thinking in terms of proprioceptive pathways extending throughout the body, from the tips of the fingers to the brain (facial muscles involved with embrasure as well as rib cage, diaphragm, lungs, and airways), those distinct pathways bear little resemblance (Figures 5 and 6).

Mark Perna, performing the 12th note in the 2nd bar of Charlie Parker’s “Blues for Alice,” on string bass.

Mark Perna, performing the 12th note in the 2nd bar of Charlie Parker’s “Blues for Alice,” on trombone.

Let’s take the case of transfer from one set of proprioceptive pathways to another. This last point can be illustrated by reference to vibraphonist Gary Burton, who, as a trained classical and jazz pianist, decided to take on a new instrument, requiring new maps and new pathways. Although visually and conceptually similar, the proprio-sentience required for performance becomes altered drastically. While the “keyboard” of a vibraphone bears much resemblance to a piano keyboard, the fact that the keys are struck by mallets deployed through the sensory and proprioceptive mastery, propelled by a standing rather than sitting performer engaging the use of the large as well as small muscles and skeletal extensions of the arms requiring movement of the entire body, means that a substantial difference in the cognitive maps and proprioceptive pathways are required for “expertise.” Thus, Burton required a process of relearning those maps and pathways to accomplish musically what had already become tacit knowledge through the mastery of piano jazz.

Yet, Burton also ended up transforming the maps and pathways of the vibraphone precisely because he had brought existing maps and pathways gained from playing the piano, by recognizing how to transform techniques derived from the piano into viable maps and proprioceptive pathways for performance through his remarkable innovation of the four-mallet technique, enabling much more sophisticated harmonic accompaniment, as well as the possibilities for contrapuntal textures while soloing on the vibrophone. This complicates our understanding of the role of non-human agency, cognitive maps, and proprioceptive pathways with respect to embodied and extended cognition.

Here we find what Deguchi calls a “nuanced understanding of agency as inherently systematic while preserving the crucial insights about the conscious human agents within such systems” (Draft 1: 11). But we now need to complicate Deguchi’s insights concerning human agency with respect to the emergent properties that cognitive multiplicity brings to our understanding of that agency. Specifically, we might question Deguchi’s assertion that human agents serve “as the only necessary internal agents who can be aware of their participation,” in the sense that there are distinct axes of internal agency that lack such awareness (8). Now, we come to the issue of cognitive multiplicity of Doer Internalism, with respect to how Embodiment connects to Embeddedness.

10 “Four E’s” of Enactive Cognitive Science and Jazz Performance

We have identified two forms of musical cognition that represent “top-down” and “bottom-up” forms of embodied cognition:[47] Projective Apprehension dominates during the learning process, which first involves conceptual mastery, identifying on the instrument “pathways” for performance, memorizing, then embodying (capturing) proprioceptively, melodic, harmonic, harmonic rhythmic and percussive rhythmic pathways through a particular composition, such as the jazz standard “All the Things You Are.” This grounds sound in an embodied way to a particular place of proprioceptive execution of pathways on the instrument, stored (colloquially) in “muscle-memory.” Projective Apprehension involves slow cognition, dominates during practice, and remains problematically involved during performance. Novices often depend upon this on the bandstand to anticipate the use of, and then consciously superimpose previously mastered pathways (learned in the practice room) onto a moment during performance.

In contrast, Proprio-Sentience happens “in the moment” of improvisation, involving a higher form of improvisational competence, by which the musician reacts at very fast cognitive speeds, to sounds emanating from others. This reverses the process described in Projective Apprehension-- so that the sound triggers proprioceptive movement spontaneously, beneath the threshold of conscious awareness, bypassing the mediating, slow forms of cognition associated with Executive Function. Projective Apprehension is largely top-down cognition, the superimposition of order onto the moment. Proprio-Sentience is largely bottom-up cognition, requiring a relinquishing of cognitive control exemplified by Executive Function, and enabled through a visceral reactive modality.[48]

The distinction between top-down Projective Apprehension and bottom-up Proprio-Sentience also aligns with the theory describing three forms of Time Cognition spelled out by cognitive scientist Francisco Varela, in “The Specious Present” (1999): Slow cognition at the 10 scale for Projective Apprehension; Very fast cognition at the 1/10 scale for Proprio-Sentience; and a default, witnessing state at the 1 scale, which attempts to subsume, balance and integrate fast and slow cognition into an heterogeneic wholeness of awareness.[49] The first remains within conscious awareness associated with Executive Function. The second must necessarily remain beneath the threshold of conscious awareness. All three forms of time cognition occur simultaneously, although the balance contingently varies.[50] Furthermore, this balance remains fragile.

In Francisco Varela, Evan Thompson, and Eleanor Rosch’s landmark The Embodied Mind (1991; and referenced in Varela’s “The Specious Present” 1999), they cite the landmark study by Libet for evidence of a lag of time between the reception of sensation and its register with self-conscious awareness or Executive Function. This lag makes improvisation “in the moment” practically impossible while trying to think. The question for jazz musicians is how that cognitive lag can be overcome?

I have already discussed briefly the three forms of time cognition: 1/10th scale, and the 10th scale (which Daniel Kahneman[51] refers to as “Fast Thinking” and “Slow Thinking”), balanced by a default status at the 1 Scale, which seeks to subsume and balance fast and slow cognition. We may infer that these forms of time cognition persist, and coexist, in uneasy and contingent relationships, and that “getting lost” is a universal experience for jazz improvisers because of that contingent, unstable relationship. Possibly, distinct neuronal ensembles that emerge from within each form of time cognition actually interfere (in the sense derived from information theory) with each other, overshadowing either the narrative of the song form at the 10 scale, or the ability to interact viscerally at the 1/10th scale. The difference between novice and expert is how much more rapidly the 1 scale can witness dysfunction, and engage top-down Executive Function to intercede and reset the balance, to rediscover the song form (10 scale) while continuing to listen (beneath the threshold) to the other musicians also improvising (1/10 scale).

The balance of the three forms of time cognition is contingent and unstable. One pervasive symptom of this instability is that all jazz musicians get lost, so that one form of time cognition overshadows the other, seeking balance within the 1 Scale. The difference between novice players and experts is the speed by which they are able to recognize being lost, and then rediscover one’s place in the song form.[52] This research underscores the conclusion that embodied human cognition is a multiplicity, which Manuel DeLanda calls “multi-homuncular,” its contingent hierarchies of selves and agents, individually autonomous yet capable of large-scale contingent integrations with other agents at higher or lower levels for more complex tasks.[53]

Recent research demonstrates that global emergent neuronal ensembles appear spontaneously during jazz improvisation, in fact more so than just about any other activity, except for meditation, and this seems to confirm these processes of larger-scale integration of lower-order agent behavior coordinating with these selves. This suggests (anticipating a conceptual punch line) that jazz ensembles, when functioning at collective “peak experience,” especially when Proprio-Sentience dominates for all players, seem to behave like neuronal ensembles within the brain, at scale.[54] Now, let’s examine what the empirical data says on the cognitive neuroscience of jazz improvisation.

11 The Empirical Evidence for Cognitive Multiplicity

So let us now examine closely, one paradigmatic work of influential empirical research in the cognitive neuroscience of jazz improvisation, which subsequently motivated research teams in replicating and extending this research: Limb and Braun’s study of the drastic differences in brain function between classical music and jazz improvised music using jazz pianists with classical technical facility,[55] responded to an earlier study by Csikszentmihaly and others,[56] which studied the role of cognition in improvisation by classically trained pianists only. Here I will summarize, then highlight details that were left out of my earlier writings.[57]

12 Limb and Braun’s Study: Differences in Cognition between Classical and Jazz Musicians

The focus of Limb and Braun’s research was to identify the neural correlates of “spontaneous musical improvisation” that “may provide insights into the neural correlates of the creative process more generally.” They sought to prove that 1. Jazz improvisation is “a prototypical form of spontaneous creative behavior”; 2. Neuronal activity is “predicated on novel combinations of ordinary mental processes,” which points to both the emergence of higher order neuronal behaviors out of lower order ones, and seems to illustrate DeLanda’s hierarchy of agents from simple to complex, capable of bottom-up emergent and top-down control behaviors through the hierarchies; 3. “Spontaneous musical improvisation would be associated with discrete changes in prefrontal cortical activity” – “a known biological substrate for actions characterized by creative self-expression”; 4. These “discrete changes” also become “associated with top-down changes in other systems, particularly commands to sensory-motor areas needed to organize the on-line execution of musical ideas and behaviors” (in real time). In other words, proprioception; 5. “The process of improvisation is involved in…unscripted behaviors that capitalize on the generative capacity of the brain” (or, as DeLanda might put it, self-organization from lower order to higher order processes by mediating agents). This is exemplified by the emergent nature of global neuronal ensemble formation and the flexibility required in their contingent formations and re-formations, from one task to the next.

13 Experimental Details

Limb and Braun built a keyboard with 35 keys, without any metal parts, so it can be placed within and played inside an fMRI without the pianist being torn to shreds by shrapnel caused by the disintegration of the keyboard by extremely powerful magnets. Limb and Braun refer to two “paradigms” structuring the study, involving overlearned (memorized) passages and then unplanned improvisations. One was relatively low…and one was high in musical complexity: Scale, and Jazz. The ScaleCtrl involved subjects simply playing a C Major Scale up and down a single octave in quarter notes. The ScaleImprov involved subjects playing contingently quarter notes within the octave C scale, without prior planning. The JazzCtrl involved memorizing a novel, complex Be Bop melody, and then performing it in the fMRI. The JazzImprov involved performing spontaneously complex melodies over the chord progression of the song from the JazzCtrl, while listening to a “Music Minus One” recording. Limb and Braun state: “Comparing these paradigms should make it possible to study not simply the content of creativity…but more importantly, the neural correlates of the cognitive state in which spontaneous creativity unfolds.”

The Major Findings were startling and drastic. I underscore this study as paradigmatic because it generated an enormous readership, led to TED talks for Charles Limb, and the development of multiple teams to extrapolate the research. It remains a landmark in music cognition: 1. Executive Function and Visual Cortex were highly engaged during “overperforming” in the “controls” of both Scale and Jazz paradigms; 2. E.F. and the V.C. were conversely disengaged in both Scale Improv and Jazz improv Performers; 3. Emergence of Neuronal Ensembles during improvisation, meaning spontaneous self-organizing global neural synchrony, including “resonances” among disparate realms of the brain without any “hardwire” connectivity; 4. The significant commonalities in brain function between simple and complex improvisation (both Scale and Jazz paradigms) say something about creativity writ large; 5. The deactivation of pre-cortical activity for both the ScaleImprov and the JazzImprov suggests that this correlate of disassociation for areas implicated in top-down cognition, such as Executive Function, applies for both simple and complex forms of spontaneous improvisation.

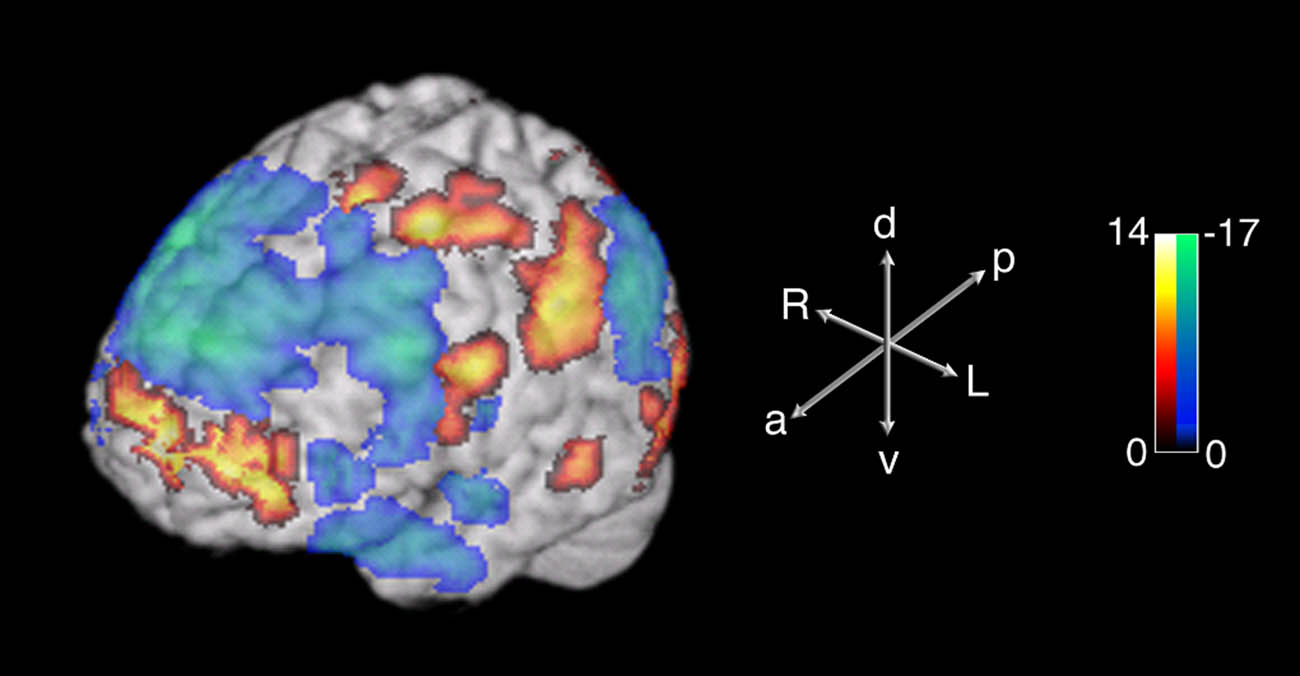

Given the methodological constraints in asserting these brain-mind correlates (see note 48 above), we need to acknowledge the following: Although the precise mapping of cognitive behaviors with reference to specific locations in the brain has actually been quite successful with respect to lower order agents, claims for correlation become more fraught when dealing with large-scale neuronal behavior involving multiple agents in multiple hierarchies. What we have are best guesses, at the moment. But one important hint emerges that helps delineate the difference between top-down projective apprehension within Executive Function, and bottom-up proprio-sentience, which must necessarily occur beneath the threshold of conscious awareness (Figure 7).[58]

Three-dimensional surface projections of spontaneous activations (red) and deactivations (blue) associated with improvisation during the Jazz paradigm. In: Limb, Charles J., A.R. Braun. “Neural Substrates of Spontaneous Musical Performance: An fMRI Study of Jazz Improvisation.”

14 Daniel Levitin and Flight or Fight and Startle Reflexes

A work published two years before the Limb and Braun study, Daniel Levitin’s This Is Your Brain on speculates (with his mentor Francis Crick) on HOW improvisation might be possible beneath the threshold of conscious awareness, so as to offset that Libet lag.[59] He proposes that the hard-wired connectivity between the motor regions of the most ancient parts of the brain, directly linked with the cochlear, identified as the pathways for “flight or fight” and “startle” reflexes, become converted for aesthetic purposes. While the initial function of these hard-wires is linked with the emotion of fear motivating instinctual motor response to existential threat, what seems to occur with jazz musicians is that, when deploying these hard-wire links, the emotion invoked becomes joy, not fear.

Furthermore, an additional implication is that the experience and expertise of the performing musicians utilizing these vestigial pathways enhance (in the exact sense of neuroplasticity) these hard-wire connections that bypass the higher order cognitive processes, such as the centers for processing sound in the prefrontal cortex and associated with Executive Function at slow cognitive speeds. Researchers have found that these hard-wire connections grow when correlated with an improvisers’ performing experience. As Pittsburgh guitarist Eric Susoeff puts it, the state of mind required for advanced improvisation requires the quality of attention “as if my life were at stake,” but without the fear. Levitin and Crick’s insight points towards possible evidence for motivated neuroplastic rewiring for aesthetic purposes.

Addressing the role of contingent, bifurcating top-down and bottom-up hierarchies of agents, and selves, is where further research needs to go. Let us now compare my connection between Projective Apprehension and Proprio-Sentience and Varela’s 3 Forms of Time cognition from “The Specious Present,” with DeLanda’s explication of Damasio’s hierarchy of agents, in their relationship to the hierarchy of Selves, and the upward (emergent) and downward (superimposed) mediated causalities, from simple to complex.

14.1 Manuel DeLanda and Materialist Phenomenology of Selves and Agents